|

BENJAMIN WEST.

An American Quaker by birth, was the youngest of a family of ten children,

and was nurtured with great tenderness and care: a prophecy uttered by a

preacher of the sect having impressed his parents with the belief that

their child would, one day, become a great man. In what way the

prophecy was to be realized they had formed to themselves no definite

idea; but an incident which occurred in young West's sixth year, led his

father to ponder deeply as to whether its fulfilment were not begun.

Benjamin, being left to watch the infant child of one of his relatives

while it was left asleep in the cradle, had drawn its smiling portrait, in

red and black ink, there being paper and pens on the table in the room.

This spontaneous and earliest essay of his genius was so strikingly

truthful that it was instantly and rapturously recognized by the family.

During the next year he drew flowers and birds with pen and ink; but a

party of Indians, coming on a visit to the neighbourhood, taught him to

prepare and use red and yellow ochre and indigo. Soon after, he

heard of camel-hair pencils, and the thought seized him that he could make

use of a substitute, so he plucked hairs from the tail of a black cat that

was kept in the house, fashioned his new instrument, and began to lay on

colours, much to his boyish satisfaction. In the course of another

year a visitant friend, having seen his pictures, sent him a box of

colours, oils, and pencils, with some pieces of prepared canvas and a few

engravings. Benjamin's fascination was now indescribable. The

seductions presented by his new means of creation were irresistible, and

he played truant from school for some days, stealing up into a garret, and

devoting the time, with all the throbbing wildness of delight, to

painting. The schoolmaster called, the truant was sought, and found

in the garret by his mother. She beheld what he had done; and,

instead of reprehending him, fell on his neck and kissed him, with tears

of ecstatic fondness. How different from the training experienced by

the poor, persecuted and tormented "Salvatoriello!" What wonder,

that the fiery-natured Italian afterwards drew human nature with a severe

hand; and how greatly might his vehement disposition have been softened,

had his nurture resembled that of the child of these gentle Quakers!

The friend who had presented him with the box of colours,

some time after took him to Philadelphia, where he was introduced to a

painter, saw his pictures, the first he had ever seen except his own, and

wept with emotion at the sight of them. Some books on Art increased

his attachment to it; and some presents enabled him to purchase materials

for further exercises. Up to his eighteenth year, strange as the

facts seem, he received no instruction in painting, had to carve out his

entire course himself, and yet advanced so far as to create his first

historical picture, "The Death of Socrates," and to execute portraits for

several persons of taste. His father, however, had never yet

assisted him; for, with all his ponderings on the preacher's prophecy, he

could not shake off some doubts respecting the lawfulness of the

profession of a painter, to which no one of the conscientious sect had

ever yet devoted himself. A counsel of "Friends" was therefore

called together, and the perplexed father stated his difficulty and

besought their advice. After deep consideration, their decision was

unanimous that the youth should be permitted to pursue the objects to

which he was now both by nature and habit attached; and young Benjamin was

called in, and solemnly set apart by the primitive brethren for his chosen

profession. The circumstances of this consecration were so

remarkable, that, coupled with the early prophecy already mentioned, they

made an impression on West's mind that served to strengthen greatly his

resolution for advancement in Art, and for devotion to it as his supreme

object through life.

On the death of his affectionate mother, he finally left his

father's house, and, not being yet nineteen, set up in Philadelphia as a

portrait-painter, and soon found plenty of employment. For the three

or four succeeding years he worked unremittingly, making his second essay

at historic painting within that term, but labouring at portraits, chiefly

with the view of winning the means to enable himself to visit Italy.

His desire was at length accomplished, a merchant of New York generously

presenting him with fifty guineas as an additional outfit, and thus

assisting him to reach Rome without the uneasiness that would have arisen

from straitness of means in a strange land.

The appearance of a Quaker artist of course caused great

excitement in the metropolis of Art; crowds of wonderers were formed

around him; but, when in the presence of the great relics of Grecian

genius, he was the wildest wonderer of all. "How like a young

Mohawk!" he exclaimed, on first seeing the "Apollo Belvidere," its

life-like perfection bringing before his mind, instantaneously, the free

forms of the desert children of Nature in his native America. The

excitement of little more than one month in Rome threw him into a

dangerous illness from which it was some time before he recovered.

He visited the other great cities of Italy, and also painted and exhibited

two great historical pictures, which were successful, ere the three years

were completed which he stayed in that country. He would have

returned to Philadelphia; but a letter from his father recommended him

first to visit England.

West's success in London was speedily so decided, that he

gave up all thoughts of returning to America. For thirty years of

his life he was chiefly employed in executing, for King George the Third,

the great historical and scriptural pictures which now adorn Windsor

Palace and the Royal Chapel. After the abrupt termination of the

commission given him by the king, he continued still to be a laborious

painter. His pictures in oil amount to about four hundred, and many

of them are of very large dimensions and contain a great number of

figures. Among these may be mentioned, for its wide celebrity, the

representation of "Christ healing, the Sick," familiar to every visitor of

the National Gallery. If polished taste be more highly charmed with

other treasures there, the heart irresistibly owns the excellence of this

great realization by the child of the American Quaker. He received

three thousand guineas for this picture, and his rewards were of the most

substantial kind, ever after his settlement in England. He was also

appointed President of the Royal Academy, on the death of Sir Joshua

Reynolds, and held the office at his own death, in the eighty-second year

of his age.

Though exposed to no opposition from envy or jealousy at any

time of his career, and though encouraged in his childish bent, and helped

by all who knew him and had the power to help him, without Perseverance of

the most energetic character, Benjamin West would not have continued

without pattern or instruction to labour on to excellence, nor would he

have sustained his prosperity so firmly, or increased its productiveness

so wondrously.

CHAPTER IV.

MUSICIANS.

_______

HANDEL AND BACH.

THE time may come when Music will be universally

recognized as the highest branch of Art; as the most powerful divulger of

the intellect's profoundest conceptions and noblest aspirations; as the

truest interpreter of the heart's loves and hates, joys and woes; as the

purest, least sensual, disperser of mortal care and sorrow; as the

all-glorious tongue in which refined, good, and happy beings can most

perfectly utter their thoughts and emotions. Perhaps this cannot be till

the realm of the physical world be more fully subdued by man. The human

faculties have hitherto been, necessarily, too much occupied with the

struggle for existence, for security against want and protection from the

elements, with the invention of better and swifter modes of locomotion and

of transmission of thought, to advance to a general apprehension of the

superior nature of Music. "Practical men"—men fitted for the discharge of

the world's present duties by the manifestation of the readiest and

fullest capacity for meeting its present wants—are, naturally and justly,

those whom the world most highly values in its current state of

civilization.

This necessary preference of the practical to the ideal may lead many, who

cannot spare a thought from the every-day concerns of the world, to deem

hastily that the stern and energetic quality of Perseverance cannot be

fully developed in the character of a devotee to Music. But, dismissing

the greater question just hinted at, it may be replied that it is the

evident tendency of man to form the lightest pleasures of the mind, as

well as his gravest discoveries, into what is called "science;" and the

lives of numerous musicians show that vast powers of application have been

continuously devoted to the elaboration of the rules of harmony, while

others have employed their genius as ardently in the creation of melody. These creations, when the symbols are learnt in which they are written,

the mind, by its refined exorcism, can enable the voice, or the hand of

the instrumental performer, to summon into renewed existence to the end of

time. Before symbols were invented and rules constructed, the wealth of

Music must necessarily have been restricted to a few simple airs such as

the memory could retain and easily reproduce.

Perseverance—Perseverance—has guided and sinewed men's love of the

beautiful and powerful in melody and harmony, until, from the simple

utterance of a few notes of feeling; rudely conveyed from sire to son by

renewed utterance, Music

has grown up into a science, dignified and adorned by profound theorists,

like Albrechtsberger, and by sublime creative geniuses, such as the

majestic Handel and sweetest Haydn and universal Mozart and sublime

Beethoven.

For their successful encounter of the great "battle of life," a hasty

thinker would also judge that the extreme susceptibility of musicians must

unfit them; extreme susceptibility, which is, perhaps, more peculiarly

their inheritance than it is that even of poets. Yet the records of the

lives of musical men prove, equally with the biographies of artists,

authors, and linguists, that true genius, whatever may be the object of

its high devotion, is unsubduable by calamity and opposition. The young

inquirer will find ample proof of this in various biographies: our limits

demand that we confine ourselves to one musician, as an exemplar of the

grand attribute of Perseverance.

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL.

|

|

|

George Frederick Handel (1685-1759)

by Balthasar Denner (1733) |

The first of the four highest names in Music, was the son of a physician

of Halle, in Lower Saxony, and was designed by his father for the study of

the civil law. The child's early attachment to music—for he could play

well on the old instrument called a clavichord before he was seven years

old—was, therefore, witnessed by his parent with great displeasure. Unable to resist the dictates of his nature, the boy used to climb up into

a lonely garret, shut himself up, and practise, chiefly when the family

were asleep. He attached himself so diligently to the practice of his

clavichord, that it enabled him, without ever having received the

slightest instruction, to become an expert performer on the harpsichord. It was at this early

age that the resolution of young Handel was manifested in the singular

incident often told of his childhood. His father set out in a chaise to go

and visit a relative who was valet-de-chambre to the Duke of

Saxe-Weisenfels, but refused to admit the boy as a partner in his journey. After the carriage, however, the boy ran, kept closely behind it for some

miles,

unconquerable in his determination to proceed, and was at last taken into

the chaise by his father. When arrived, it was impossible to keep him from

the harpsichords in the duke's palace; and, in the chapel, he contrived to

get into the organ-loft, and began to play with such skill on an

instrument he had never before touched, that the duke, overhearing him,

was surprised, asked who he was, and then used every argument to induce

the father to make the child a musician, and promised to patronize him.

Overcome by the reasonings of this influential personage, the physician

gave up the thought of thwarting his child's disposition and, at their

return to Halle, placed young Handel under the tuition of Zachau, the

organist of the cathedral. The young "giant"—a designation afterwards so

significantly bestowed upon him by Pope—grew up so rapidly into mastery

of the instrument, that he was soon able to conduct the music of the

cathedral in the organist's absence; and, at nine years old, composed

church services both for voices and instruments. At fourteen he excelled

his master; and his father resolved to send him, for higher instruction,

to a musical friend who was a professor at Berlin. The opera then

flourished in that city more highly than in any other in Germany; the king

marked the precocious genius of the young Saxon, and offered to send him

into Italy for still more advantageous study: but his

father, who was now seventy years old, would not consent to his leaving

his "fatherland."

Handel next went to Hamburgh, where the opera was only little inferior to

Berlin. His father died soon after; and, although but in his fourteenth

year, the noble boy entered the orchestra as a salaried performer, took

scholars, and thus not only secured his own independent maintenance, but

sent frequent pecuniary help to his mother. How worshipfully the true

children of Genius blend their convictions of moral duty with the untiring

aim to excel!

On the resignation of Keser, composer to the opera, and first harpsichord

in Hamburgh, a contest for the situation took place between Handel and the

person who had hitherto been Keser's second. Handel's decided superiority

of skill secured him the office, although he was but fifteen years of age;

but his success had nearly cost him his life, for his disappointed

antagonist made a thrust with a sword at his breast, where a music-book

Handel had buttoned under his coat prevented the entrance of the weapon. Numerous sonatas, three operas, and other admired pieces, were composed

during Handel's superintendence of the Hamburgh opera; but, at nineteen,

being invited by the brother of the Grand Duke, he left that city for

Tuscany. He received high patronage at Florence, and afterwards

visited Venice, Rome, and Naples, residing, for shorter or longer periods,

in each city, producing numerous

operas, cantatas, and other pieces, reaping honours and rewards, and

becoming acquainted with Corelli, Scarletti, and other musicians; till,

after spending six years in Italy, he returned to Germany.

Through the friendship of Baron Kilmansegg be was introduced to the

Elector of Hanover, was made "chapel-master" to the court, and had a

pension conferred upon him of fifteen hundred crowns a year. In order to

secure the services of the "great musician," as he was acknowledged now to

be, the King provided that he should be allowed, at will, to be absent for

a year at a time. The very next year he took advantage of this provision

and set out for England, having first visited his old master Zackau, and

his aged and blind mother for the last time—still true, amidst the

dazzling influences of his popularity, to the most correct emotions of the

heart!

His opera of "Rinaldo" was performed with great success during his stay in

this country, and after one year he returned to Hanover; yet his

predilection for England, above every other country he had seen, was so

strong, that after the lapse of another year he was again in London. The

peace of Utrecht occurred a few months after his second arrival, and

having composed a Te Deum and Jubilate in celebration of it, and thereby

won such favour that Queen Anne was induced to solicit his continuance in

England, and to confer upon him a pension of £200 a year, Handed resolved

to forfeit his Hanoverian pension, and made

up his mind to remain in London. But, two years afterwards, the Queen

died, and the great musician was now in deep dread that his slight of the

Elector's favours would be resented by that personage on be coming King of

England. George the First, indeed, expressed himself very indignantly

respecting Handel's conduct; but the Baron Kilmansegg again rendered his

friend good service. He instructed Handel to compose music of a striking

character, to be played on the water, as the King took amusement with a

gay company. Handel created his celebrated "Water Music," chiefly adapted

for horns; and the effect was so striking that the King was delighted. Kilmansegg seized the opportunity, and sued for the restoration of his

friend to favour. The boon was richly obtained, for Handel's pension was

raised to £400 per annum, and he was appointed musical teacher to the

young members of the Royal Family.

Prosperity seemed to have selected Handel, up to this period, for her

favourite; but severe reverses were coming. The opera in this country had

hitherto been conducted on worn-out and absurd principles, and a large

body of the people of taste united to promote a reform. Rival opera-houses

(as at the present period) were opened; and during nine years Handel

superintended one establishment. It was one perpetual quarrel: when

his opponents, by any change, had become so feeble that he seemed on the

eve of a final triumph, one or other of the singers in his own company

would grow unmanageable;

Senesino was the chief of these, and Handel's refusal to accept the

mediation of several of the nobility, and be reconciled to him, caused the

establishment over which he presided to be finally broken up. The

great powers of Farinelli, the chief singer at the rival house, to whom an

equal could not then be found in Europe, also largely contributed to

Handel's ruin. He withdrew, with a loss of ten thousand pounds; his

constitution seemed completely broken with the

years of harassment he had experienced; and he retired to the baths of

Aix-la-Chapelle, scarcely with the hope, on the part of his friends, that

they would ever see him in England again.

His paralysis and other ailments, however, disappeared with wondrous

suddenness; after be reached the medical waters, he recovered full health

and vigour, and, at the age of fifty-two, returned to England with the

manly resolve to struggle till he had paid his debts, and once more

retrieved a fortune equal to his former condition. It was now that the

whole strength of the man was tried. He produced his "Alexander's Feast;"

but, in spite of its acknowledged merit, the nobility whom he had offended

would not patronize him. He produced other pieces, but they failed from

the same cause. He then bent his mighty genius on the creation of newer

and grander attractions than had ever been yet introduced in music, and

produced his unequalled "Messiah," which was performed at Covent Garden

during Lent. Yet the combination against him was maintained, until he sunk

into deeper difficulties than ever.

Unsubdued by the failures which had accumulated around him during the five

years which had elapsed since his return to England, he set out for

Ireland, at fifty-seven, and had his "Messiah" performed in Dublin, for

the benefit of the city prison. His success was instantaneous; several

performances took place for his own benefit, and the next year he renewed

the war against Fortune, in London, by producing his

magnificent "Samson," and having it performed, together with his "Messiah," at Covent Garden. The first renewed performance of the "Messiah" was for the benefit of the Foundling Hospital; and the funds of

that philanthropic institution were thenceforth annually benefited by the

repetition of that sublime Oratorio. Prejudice was now subdued, the "mighty master" triumphed, and his darling wished-for honourable

independence was fully realized; for more than he had lost was retrieved.

Handel's greatest works, like those of Haydn, were produced in his

advanced years. His " Jephthah" was produced at the age of

sixty-seven. Paralysis returned upon him at fifty-nine, and gutta serena—Milton's

memorable affliction—reduced him to "total eclipse" of sight some years

after: but he submitted cheerfully to his lot, after brief murmuring, and

continued, by dictation to an amanuensis, the creation of new works, and

the performance of his Oratorios to the last. He conducted his last

Oratorio but a week before his death, and died, as he had always desired

to do, on Good Friday, at the age of seventy-five. He was interred, with

distinguished honours, among the great and good of that country which had

naturalized him, in Westminster Abbey. May the sight of his monument

inspire the young reader with an unquenchable zeal to emulate, in whatever

path wisdom may direct life to be passed, the moral and intellectual

excellencies of this glorious disciple of Perseverance!

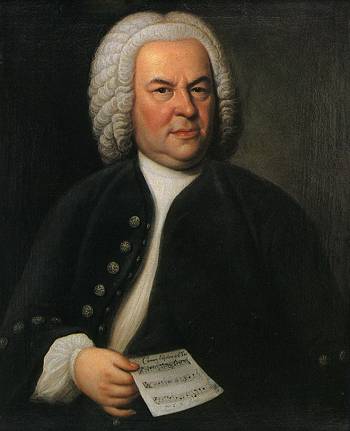

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH.

|

|

|

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (ca. 1748) |

Hereditary talent for one particular art was, perhaps, never more

strikingly exhibited than in the Bach family of Saxony. Four generations

of the family, numbering fifty individuals, were more or less famous for

musical ability. One of these, Johann Sebastian, ranks with the greatest

masters of the art, and owed his eminence, not only to great natural

talent, but to most laborious and persevering study of musical science. The ablest musicians of the present day acknowledge how much they are

indebted to his consummate knowledge, and regard him as their teacher, and

his sublime compositions are becoming more and more appreciated.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in the same year as Handel, 1685, at

Eisenach, or Thuringia, where his father was a professional musician. Before he was ten years old the boy was left an orphan, and dependent on

an elder brother, an organist at Ohrdurf, from him he received some

rudimentary instruction; but he was indebted more to his own quick

perception and industry for the knowledge he contrived to acquire. The

elder Bach died in 1698, and Johann, then fourteen years of age, was left

destitute. Possessing a very beautiful voice, he obtained a place in the

choir of St. Michael's, Lüneberg, which gave him the opportunity of

acquiring a familiarity with

some of the best compositions. He studied hard, and continued his practice

on the organ with such success that, in 1703, although only eighteen years

old, he became court musician at Weimar, and in the following year

organist to a church at Arnstadt. While at Weimar, he composed many pieces

of sacred music, among them some of the most beautiful of his cantatas. In 1708, the Duke of Saxe-Weimar appointed him court organist, and while

holding that office he laboured assiduously and made himself master of

every branch of musical science. His fame as a performer on the organ

spread throughout Germany, and an amusing incident is recorded. A French

organist of great reputation, Louis Marchaud, who believed himself to

possess unrivalled powers, was travelling in Germany. He arrived at

Dresden, and we read, "lorded it over his artistic colleagues at the

Saxon Court in the most sublime manner." They were not disposed to admit

his pretensions, and proposed a contest on the organ between him and Bach. The Frenchman almost contemptuously accepted the challenge, and

a day for the competition was arranged. The Duke and court, and all the

musical celebrities of the place were invited to attend, and a grand

display was anticipated; but Marchaud having had a private opportunity of

hearing Bach perform, was afraid of exposing himself to an ignominious

defeat, and quietly left the town before the day of contest arrived.

After a residence of nine years at Weimar, he was induced by the Duke of

Köthen to accept the position of musical

conductor (Kapell-meister) at

his court, and remained there six years, after which, in 1723, he removed

to Leipsic, where he was appointed director of music at the famous St.

Thomas' school, and organist at two of the principal churches. At Leipsic

he resided for the remainder of his life, and there he composed his

greatest works, engraving some of the music plates with his own hands.

The honorary distinctions of Kapell-meister to the Duke of Weissenfels and

court composer to the King of Poland, were conferred on him; and, in 1747,

he was invited by Frederick the Great of Prussia to visit him at Potsdam. Frederick had a taste

for music, was himself a composer and performer of

fair ability, and was delighted to hear Bach play on the organ and

pianoforte, an instrument then coming into favour. Two years afterwards

the sight of the great musician failed, and a surgical operation was

followed by total blindness. He lived about a year after, dying of

apoplexy on the 28th of July, 1750. He was married twice, and had by his

two wives a family of eleven sons and nine daughters, four of the former

becoming musicians of note.

As an organist and composer for the organ, Bach was rivalled only by his

contemporary Handel, and in power of improvisation, it is said, he had no

equal. Many of his works have been lost, but there

remain enough to establish him as one of the greatest of musicians. In

1850, a Bach Society for the study and practice of his compositions was

formed in London, and in Germany they exercise a profound influence. The

"Passion Music," now frequently heard in London, is considered one of the

most sublime and pathetic of musical compositions.

The four sons of Bach, who most highly distinguished themselves, were

Wilhelm Friedemann, Karl Phillip Emanuel, Johann Christoph Friedrich, and

Johann Christian. Of these, Karl Phillip Emanuel, the second son of the

great composer, attained the greatest celebrity. He was born at Weimar in

1714, and having been some time at St. Thomas's school, went to the

University of Leipsic, intending to study jurisprudence. But his musical

taste was predominant, and influenced his career. From 1738 to 1767 he was

chamber musician to Frederick the Great, and afterwards, for twenty-one

years, Kapell-meister at Hamburgh, where he died in 1788. He was not only

a composer and performer of great merit, but the author of valuable

technical works of instruction.

CHAPTER V.

SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERERS AND MECHANICIANS.

_______

HUMPHRY DAVY—RICHARD ARKWRIGHT—EDMUND CARTWRIGHT.

IF great proficiency in tongues, skill to depicture

human thought and character, and enthusiastic devotion to art, be worthy

of our admiration, the toiling intelligences who have taught us to subdue

the physical world, and to bring it to subserve our wants and wishes,

claim scarcely less homage. Art and literature could never have sprung

into existence if men had remained mere strugglers for life, in their

inability to contend with the elements of nature, because ignorant of its

laws; and an acquaintance with the languages of tribes merely barbarous

would have been but a worthless kind of knowledge. To scientific

discoverers—the pioneers of civilization, who make the world worth living

in, and render man's tenancy of it more valuable by every successive step

of discovery—our primary tribute of admiration and gratitude seems

due. They are the grand revealers of the physical security, health,

plenty, and means of locomotion, which give the mind vantage-ground for

its reach after higher refinement and purer pleasures,

Should the common observation be urged, that many of the most important

natural discoveries have resulted from accident, let it be remembered,

that, but for the existence of some of our race, more attentive than the

rest, Nature might still have spoken in vain, as she had undoubtedly done

to thousands before she found an intelligent listener, in each grand

instance of physical discovery. Grant all the truth that may attach to the

observation just quoted, and yet the weighty reflection remains—that it

was only by men who, in the sailor's phrase, were "on the lookout," that

the revelations of Nature were caught. The natural laws were in operation

for ages, but were undiscovered, because men guessed rather than inquired,

or lived on without heed to mark, effort to comprehend, industry to

register, and, above all, without perseverance to proceed from step to

step in discovery, till entire truths were learnt. That these have been

the attributes of those to whom we owe the rich boon of science, a rapid

survey of some of their lives will manifest.

SIR HUMPHRY DAVY.

|

|

|

Sir Humphry Davy, FRS (1778–1829) |

The son of a wood carver of Penzance, was apprenticed by his father to a

surgeon and apothecary of that town, and afterwards with another of the

same profession, but gave little satisfaction to either of his masters. Natural philosophy had become his absorbing passion; and, even while a

boy, he dreamt of future fame as a chemist. The rich diversity of minerals

in Cornwall offered the finest field for his impassioned inquiries; and he

was in the habit of rambling alone for miles, bent upon his yearning

investigation into the wonders of Nature. In his master's garret, and with

the assistance of such a laboratory as he could form for himself from the

phials and gallipots of the apothecary's shop, and the pots and pans of

the kitchen, he brought the mineral and other substances he collected to

the test. The surgeon of a French vessel wrecked on the coast gave him a

case of instruments, among which was one that he contrived to fashion into

an air-pump, and he was soon enabled to extend the range of his

experiments; but the proper use of many of the instruments was unknown to

him.

A fortunate accident brought him the acquaintanceship of Davies Gilbert,

an eminent man of science. Young Davy was leaning one day on the gate of

his father's house, when a friend, who was passing by with Mr. Gilbert,

said, "That is young Davy, who is so fond of chemistry." Mr. Gilbert

immediately entered into conversation with the youth, and offered him

assistance in his studies. By the kind offices of his new friend, he was

afterwards introduced to Dr. Beddoes, who had formed a pneumatic

institution at Bristol, and was in want of a superintendent for it. At the

age of nineteen, Davy received this appointment, and immediately began the

splendid course of chemical discovery which has rendered his name immortal

as one of the greatest benefactors as well as geniuses of the race.

At twenty one he published his "Researches, Chemical and Philosophical,

chiefly concerning Nitrous Oxide, and its Respiration." The singularly

intoxicating quality of this gas when breathed was unknown before Davy's

publication of his experiments in this treatise. The attention it drew

upon him from the scientific world issued in his being invited to leave

Bristol, and take the chair of chemistry which had just been established

in the London Royal Institution. Although but a youth of two-and-twenty,

his lectures in the metropolis were attended by breathless crowds of men

of science and title; and, in another year, he was also appointed

Professor of Chemistry to the Board of Agriculture. His lectures in that

capacity greatly advanced chemical knowledge, and were published at the

request of the Board. When twenty-five he was elected a Fellow of the

Royal Society, and, on the death of Sir Joseph Banks, was made its

President by a unanimous vote. It was in the delivery of his Bakerian

lectures, before this learned body, that he laid the foundation of the new

science called "electro-chemistry." The Italians, Volta and Galvani, had

some years before discovered and made known the surprising effects

produced on the muscles of dead animals by two metals being brought into

contact with each other. Davy showed that the metals underwent chemical

changes, not by what had been hitherto termed "electricity," but by

affinity; and that the same effects might be produced by one of the

metals, provided a fluid were brought to act on its surface in a certain

manner. The composition and decomposition of substances by the application

of the galvanic energy, as displayed in the experiments of the young

philosopher, filled the minds of men of science with wonder.

His grand discoveries of the metallic bases of the alkalies and earths, of

the various properties of the gases, and of the connexion of electricity

and magnetism, continued to absorb the attention of the scientific world

through succeeding years; but a simple invention, whereby human life was

rescued from danger in mines, the region whence so great a portion of the

wealth of England is derived, placed him before the minds of millions,

learned and illiterate, as one of the guardians of man's existence. This

was the well-known "safety-lamp," an instrument which is provided at a

trifling expense, and with which the toiling miner can enter subterranean

regions unpierceable before, without danger of explosion of the

"fire-damp," so destructive, before this discovery, to the lives of

thousands. The humblest miner rejects any other name but that of "Davy

Lamp" for this apparently insignificant protector, and ventures, with it

in his hand, cheerfully and boldly into the realms of darkness, where the

"black diamonds" lie so many fathoms beneath the surface of the earth,

and, not seldom, under the bed of the sea. The proprietors of the Northern

coal mines presented the discoverer with a service of plate of the value

of £2000, at a public dinner, as a manifestation of their sense of his

merits. He was the first person knighted by the Prince Regent, afterwards

King George IV., and was a few years after raised to the baronetage. Such

honours served to mark the estimation in which he was held by those who

had it in their power to confer them; but Davy's enduring distinctions,

like those of the unequalled Newton, are derived from the increase of

power over nature, which he has secured for millions yet unborn, by the

force of his genius, girt up tirelessly by Perseverance till its grand

triumphs were won.

From this hasty survey of the magnificent course of one of the great

penetrators into the secrets of nature, and preservers of human life, let

us cast a glance on the struggles of one who has been the means of

multiplying man's hands and fingers—to use a strong figure—of opening up

sources of employment for millions, and of showing the road to wealth for

thousands.

SIR RICHARD ARKWRIGHT

|

|

|

Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792) |

Was a poor barber till the age of thirty, and then changed his trade for

that of an itinerant dealer in hair. Nothing is known of any early

attachment he had for mechanical inventions; but, about four years after

he had given up shaving beards, he is found enthusiastically bent on the

project of discovering the "perpetual motion," and, in his quest for a

person to make him some wheels, gets acquainted with a clockmaker of

Warrington, named Kay. This individual had also been for some time bent on

the construction of new mechanic powers, and either to him alone, or to

the joint wit of the two, is to be attributed their entry on an attempt at

Preston, in Lancashire, to erect a novel machine for spinning

cotton-thread. The partnership was broken, and the endeavour given up, in

consequence of the threats uttered by the working spinners, who dreaded

that such an invention would rob them of bread, by lessening the necessity

for human labour; and Arkwright alone, bent on the accomplishment of the

design, went to Nottingham. A firm of bankers in that town made him some

advances of capital, with a view to partake in the benefits arising from

his invention; but, as Arkwright's first machines did not answer his end

efficiently, they grew weary of the connection, and refused further

supplies. Unshaken in his own belief of future success, Arkwright now took

his models to a firm of stocking weavers, one of whom, Mr. Strutt—a name

which has also become eminent in the manufacturing enterprise of the

country—was a man of intelligence, and of some degree of acquaintance

with science. This firm entered into a partnership with Arkwright, and, he

having taken out a patent for his invention, they built a spinning-mill,

to be driven by horsepower, and filled it with frames. Two years

afterwards they built another mill at Cromford, in Derbyshire, moved by

water-power; but it was in the face of losses and discouragements that

they thus pushed their speculations. During five years they sunk twelve

thousand pounds, and his partners were often on the point of giving up the

scheme. But Arkwright's confidence only increased by failure, and, by

repeated essays at contrivance, he finally and most triumphantly

succeeded. He lived to realize an immense fortune, and his present

descendant is understood to be one of the wealthiest persons in the kingdom. The weight of cotton imported now is three hundred times greater than

it was a century ago; and its manufacture, since the invention of Arkwright, has become the greatest in England.

THE REV. EDMUND CARTWRIGHT, D.D.

Must be mentioned as the meritorious individual who completed the

discovery of cotton manufacture, by the invention of the power-loom. His

tendency towards mechanical contrivances had often displayed itself in his

youth; but his love of literature, and settlement in the church, led him

to lay aside such pursuits as trifles, and it was not till his fortieth

year that a conversation occurred which roused his dormant faculty. His

own account of it must be given, not only for the sake of its striking

character, but for the powerful negative it puts upon the hackneyed

observation, that almost all great and useful discoveries have resulted

from "accident." The narrative first appeared in the "Supplement to the Encyclopoedia Britannica:"

"Happening to be at Matlock, in the summer of 1784, I fell in company

with some gentlemen of Manchester, when the conversation turned on Arkwright's spinning machinery. One of the company observed that, as soon

as Arkwright's patent expired, so many mills would be erected, and so much

cotton spun, that hands would never be found to weave it. To this

observation I replied, that Arkwright must then set his wits to work to

invent a weaving-mill. This brought on a conversation upon the subject, in

which the Manchester gentlemen unanimously agreed that the thing was

impracticable, and, in defence of their opinion, they adduced arguments

which I was certainly incompetent to answer, or even to comprehend, being

totally ignorant of the subject, having never at the time seen a person

weave. I controverted, however, the impracticability of the thing,

by remarking that there had been lately exhibited in London an automaton

figure which played at chess. 'Now, you will not assert, gentlemen,'

said I, 'that it is more difficult to construct a machine that shall

weave, than one that shall make all the variety of moves that are required

in that complicated game.' Some time afterwards, a particular

circumstance recalling this conversation to my mind, it struck me that, as

in plain weaving, according to the conception I then had of the business,

there could be only three movements, which were to follow each other in

succession, there could be little difficulty in producing and repeating

them. Full of these ideas I immediately employed a carpenter and

smith to carry them into effect. As soon as the machine was finished

I got a weaver to put in the warp, which was of such materials as

sail-cloth is usually made of. To my great delight a piece of cloth,

such as it was, was the, produce. As I had never before turned my

thoughts to mechanism, either in theory or practice, nor had seen a loom

at work, nor knew anything of its construction, you will readily suppose

that my first loom must have been a most rude piece of machinery.

The warp was laid perpendicularly; the reed fell with a force of at least

half- a-hundredweight; and the springs which threw the shuttle were strong

enough to have thrown a congreve rocket. In short, it required the

strength of two powerful men to work the machine, at a slow rate, and only

for a short time. Conceiving, in my simplicity, that I had

accomplished all that was required, I then secured what I thought a most

valuable property by a patent, 4th of April, 1785. This being done,

I then condescended to see how other people wove; and you will guess my

astonishment when I compared their easy modes of operation with mine.

Availing myself, however, of what I then saw, I made a loom in its general

principles nearly as they are now made. But it was not till the year

1787 that I completed my invention when I took out my last weaving patent,

August the 1st of that year."

Challenged by a manufacturer who came to see his machine, to

render it capable of weaving checks or fancy patterns, Dr. Cartwright

applied his mind to the discovery, and succeeded so perfectly, that when

the manufacturer visited him again some weeks after, the visitor declared

he was assisted by something beyond human power. Were these

discoveries the fruit of "accident," or were they attributable to the

power of mind, unswervingly bent to attain its object by Perseverance?

Numerous additional inventions in manufactures and

agriculture owe their origin to this good as well as ingenious man, whose

mind was so utterly uncorrupted by any sordid passion that he neglected to

turn his discoveries to any great pecuniary benefit, even when secured to

him by patent. The merchants and manufacturers of Manchester,

however, memorialized the Lords of the Treasury in his behalf, during his

latter years, and Parliament made him a grant of £10,000. Dr.

Cartwright directed his mind to the steam-engine, among his other

thoughts, and told his son, many years before the prophecy was realized,

that, if he lived to manhood, he would see both ships and land-carriages

moved by steam. From seeing one of his models of a steam-vessel, it

is asserted that Fulton, then a painter in this country, urged the idea of

steam navigation upon his countrymen, on his return to America, until he

saw it triumphantly carried out.

The new and vast motive power just mentioned conducts us to

another illustrious name in the list of the disciples of Perseverance.

Like the names of Newton, Guttenberg the inventor of printing, and a few

others, the name to which we allude has claims upon the gratitude of

mankind which can never be fully rendered until the entire race

participate in the superior civilization it is the certain destiny of

these grand discoveries to institute. |