|

[Previous

Page]

JAMES WATT

|

|

|

James Watt (1736-1819) |

Was the son of

a small merchant of Greenock, and, on account of his weakly state when a

child, was unable at first to enjoy the advantages of school tuition and

was therefore taught chiefly at home. When but six years old he was

frequently caught chalking diagrams and solving problems on the hearth;

and at fourteen he made a rude electrical machine with his own hands.

His aunt, it is related, often chided him for indolence and mischief, when

he was found playing with the tea-kettle on the fire, watching the steam

coming out of the spout, and trying the steam's force by obstructing its

escape; the might of the vaporous element seeming even then to have begun

to present itself, unavoidably, to his imagination and understandng. He

grew to be an extensive manufacturer of philosophical toys while a boy,

and used to increase his pocket-money by standing with them at the college

gate, in Glasgow, and vending them to the students as they passed out. At

eighteen years of age his father apprenticed him to a mathematical

instrument maker in London, but in little more than a year his weak

health rendered it necessary to send him home to Scotland.

At twenty-one, although he had received so little instruction in that

profession, his skill secured him

the appointment of mathematical instrument maker to the College of

Glasgow. His appointment, however, was not sufficiently productive to

render it worth keeping; and, seven years afterwards, he began to

practise as a general engineer, for which diligent study during this term

had fitted him. He was soon sought after for almost every undertaking of

public improvement,—whether for the making of bridges, canals, harbours,

or any other engineering design projected in Scotland. But the

circumstance of a small model of a steam-engine being sent him to repair,

fixed his attention powerfully upon the element which had so often excited

the attention of his boyish understanding.

Watt found this model so imperfect, although it was the

most perfect then known, that he could with difficulty get it to work.

The more he examined it, the more deeply he became convinced that the properties of steam had

never been understood: the engine was, in fact, an atmospheric rather than

a steam engine. By laborious investigation he ascertained that the

evaporation of water proceeded more or less rapidly in proportion to the

degree of heat made to enter it; that the process of evaporation was

quickened as a greater surface of water was exposed to heat, the

quantity of coals necessary to raise a certain weight of water into steam,

and the degrees of heat at which water boils under different pressures. He

had now learnt enough of the nature of the great element he proposed to

wield; but it required long thought and the most exhaustless application

of contrivance to give his vaporous giant a fitting body, limbs, joints,

and sinews, and so to adapt these as to render them a self-regulating

mechanism. Watt found a coadjutor in the person of Boulton, of Birmingham,

who was possessed of capital, and the will to embark it; and he now set to

work to perfect his discovery, and did perfect it; thus revealing to man

the greatest instrument of power yet put into his possession.

"In the present perfect state of the engine," says Dr. Arnott, in his "Elements of Physics," "it appears a thing almost endowed with

intelligence. It regulates, with perfect accuracy and uniformity, the

number of its strokes in a given time; counting or recording them,

moreover, to tell how much work it has done, as a clock records the beats

of its pendulum; it regulates the quantity of steam admitted to work; the

briskness of the fire; the supply of water to the boiler; the supply of

coals to the fire; it opens and shuts its valves with absolute precision

as to time and manner; it oils its joints; it takes out any air which may

accidentally enter into parts which should be vacuous; and when anything

goes wrong, which it cannot itself rectify, it warns its attendants by

ringing a bell: yet, with all these talents and qualities, and even when

exerting the power of six hundred horses, it is obedient to the hand of a

child; its aliment is

coal, wood, charcoal, or other combustible; it consumes none while idle;

it never tires, and wants no sleep; it is not subject to malady when

originally well made, and only refuses to work when worn out with age; it

is equally active in all climates, and will do work of any kind; it is a

water-pumper, a miner, a sailor, a cotton-spinner, a weaver, a blacksmith,

a miller, &c., &c.; and a small engine, in the character of a steam-pony,

may be seen dragging after it on a railroad a hundred tons of merchandise,

or a regiment of soldiers, with greater speed than that of our fleetest

coaches. It is the king of machines, and a permanent realization of the

genii of Eastern fable, whose supernatural powers were occasionally at the

command of man."

And what was the greater instrument? The mind of Watt, whose powers were

manifested by the creation of this grandest physical instrument. Could

such a display of resources, such amazing circumspection of the wants and

needs of his machine, and wisdom in the adaptation of its members to the

perfect working of the whole, have been given forth from an intellect

untrained itself to rule, uninured itself to toil, and to toil with

certitude for an end, by persevering collection of all that could increase

its aptitude to reach it? The estimate of James Watt's character, by the

eloquent Lord Jeffrey, will afford a weighty answer.

"Independently of his great attainments in mechanics, Mr. Watt was an

extraordinary and, in many respects, a wonderful man. Perhaps no

individual in his age possessed so much and such varied and exact

information—had read so much, or remembered what he had read so

accurately and well. He had infinite quickness of apprehension, a

prodigious memory, and a certain rectifying and methodizing power of

understanding, which extracted something precious out of all that was

presented to it. His stores of miscellaneous knowledge were immense, and

yet less astonishing than the command he had at all times over them. It

seemed as if every subject that was casually started in conversation had

been that which he had been last occupied in studying and exhausting; such

was the copiousness, the precision, the admirable clearness of the

information which he poured out upon it without effort or hesitation. Nor

was this promptitude and compass of knowledge confined in any degree to

the studies connected with his ordinary pursuits. That he should have been

minutely and extensively skilled in chemistry and the arts, and in most of

the branches of physical science, might, perhaps, have been conjectured;

but it could not have been inferred from his usual occupations, and,

probably, is not generally known, that he was curiously learned in many

branches of antiquity, metaphysics, medicine, and etymology, and perfectly

at home in all the details of architecture, music, and law. He was well

acquainted, too, with

most of the modern languages, and familiar with their most recent

literature. Nor was it at all extraordinary to hear the great mechanician

and engineer detailing and expounding, for hours together, the

metaphysical theories of the German logicians, or criticising the measures

or the matter of the German poetry.

"His astonishing memory was aided, no doubt, in a great measure, by a

still higher and rarer faculty by his power of digesting and arranging in

its proper place all the information he received, and of casting aside and

rejecting, as it were instinctively, whatever was worthless or immaterial. Every conception that was suggested to his mind seemed instantly to take

its place among its other rich furniture, and to be condensed into the

smallest and most convenient form. He never appeared, therefore, to be at

all encumbered or perplexed with the verbiage of the dull books he

perused, or the idle talk to which he listened, but to have at once

extracted, by a kind of intellectual alchemy, all that was worthy of

attention, and to have reduced it for his own use to its true value and to

its simplest form. And thus it often happened that a great deal more was

learned from his brief and vigorous account of the theories and arguments

of tedious writers, than an ordinary student could have derived from the

most faithful study of the originals; and that errors and absurdities

became manifest from the mere clearness and plainness of his statement of them, which might have deluded and

perplexed most of his hearers without that invaluable assistance."

Such was the activity, industry, discipline, and perseverance in

acquirement, of the mind which gave to the world its greatest physical

transformer—the instrument which is changing the entire civilization of

the world, "doing the work of multitudes, overcoming the difficulties of

depth, distance, minuteness, magnitude, wind, and tide; exhibiting

stranger wonders than those of romance or magic; annihilating time and

space; giving wings even to thought, and sending knowledge like light

through the human universe; most mighty, with power that Watt knew not of,

and with more than we know, for futurity. The discovery of America," says

the same eloquent writer, W. J. Fox, in his "Lectures to the Working

Classes," "was of matter to be worked upon: this is power to work upon the

world."

COLUMBUS

Starts before the mind with the enunciation of the sentence just quoted. He whose indomitable perseverance carried his mutinous sailors onward—and

onward—across the dreary Atlantic, in a frail bark, until fidelity to his

own convictions issued in the magnificent proof of their verity, the

discovery of the

new world. But our space demands that we pass to the incomparable name

which towers, alone, above that of James Watt, in the world's list of the

scientific benefactors of mankind; and, perhaps, above all human names in

its peerless excellence.

SIR ISAAC NEWTON.

|

|

|

Sir Isaac Newton, (1643–1727)

by Godfrey Kneller (1689) |

It is so well known as scarcely to need repeating here, displayed his

wondrous and incontrollable tendency for scientific inquiry in boyhood. In

him too, as in the minds of almost all philosophical discoverers, was

evinced the faculty for mechanical contrivance, as well as acuteness for

demonstration. The anecdotes of his boyish invention, of his windmill with

a mouse for the miller, his water-clock, carriage, and sun-dials, and of

his kites and paper lanterns, are familiar. His mother having been

persuaded, by an intelligent relative, to give him up from agricultural

cares, to which his genius could not be tied down, he was sent to

Cambridge, and entered Trinity College in his eighteenth year. He

proceeded at once to the study of "Descartes' Geometry," regarding

"Euclid's Elements" as containing self-evident truths, when he had gone

through the titles of the propositions. Yet he afterwards regretted this

neglect of the rigid method of demonstration, in the outset, as a great

mistake, and wished he had not attached himself so closely to modes of

solution by algebra. He successively studied, and wrote commentaries on,

"Wallis's Arithmetic of Infinities," "Sannderson's Logic," and "Kepler's

Optics;" and, for testing the doctrines of the latter science, bought a

prism, and made numerous experiments with it. While but a

very young man, Dr. Isaac Barrow, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics,

gathered hints of new truths from his conversation; and in the publication

of his lectures on optics, a few years after, the Doctor acknowledged his

obligations to young Newton, and characterized him very highly. A year

after this publication, Barrow resigned his chair in favour of Newton, who

had recently taken the degree of Master of Arts.

Zeal to acquit himself well in his professorship, a situation so congenial

to his mind, led him to devote the most profound attention to the

doctrines of light and vision. Realities were what he sought, even in the

most abstract pursuits; and he expended considerable manual labour in

constructing reflecting telescopes. One of these most valued relics of his

mechanical toil is now in the library of the Royal Society. The result of

his studies and experiments was not fully known before the publication of

his "Opticks," in his sixty-second year; but it is believed his entire

discovery of the nature of light was made many years before, being at

length "put together out of scattered papers." The modesty of this great

man was, indeed, the most distinguishing mark of his intellect. Arrogant

satisfaction, or pride of superior genius, never sullied his greatness. Even in giving this scientific treasure to the world, he says he designed

to repeat most of his observations with more care and exactness, and to

make some new ones for determining the manner how the rays of light are

bent in their passage by bodies, for making the fringes of colours with

the dark lines between them.

How much are we indebted to the patient perseverance of all the true

discoverers in science! This is the quality of mind which ever

distinguished them. Rashness and presumption, haste to place his crude

theories before the world, and to gain assent to them before proof, on the

other hand, are the sure marks of the empiric or pretender. The popular

author of "The Pursuit of Knowledge under Difficulties"—a work the young

student should carry about with him as a never-failing stimulus to

perseverance—thus admirably treats this pre-eminent characteristic of the

mind of Newton:—"On some occasions he was wont to say, that, if there was

any mental habit or endowment in which he excelled the generality of men,

it was that of patience in the examination of the facts and phenomena of

his subject. This was merely another form of that teachableness which

constituted the character of the man. He loved Truth, and wooed her with

the unwearying ardour of

a lover. Other speculators had consulted the book of nature, principally

for the purpose of seeking in it the defence of some favourite theory:

partially, therefore, and hastily, as one would consult a dictionary. Newton perused it as a volume altogether worthy of being studied for its

own sake. Hence proceeded both the patience with which he traced its

characters, and the rich and plentiful discoveries with which the

search rewarded him. If he afterwards classified and systematized his

knowledge like a philosopher, he had first, to use his own language,

gathered it like a child." .

This transcendent combination of qualities,—modesty, patient

investigation, and indefatigable perseverance,—was still more wondrously

shown in his superlative discovery of the theory of gravitation, than in

his promulgation of the laws of light and vision. The anecdote of his

observation of the fall of an apple from a tree, while sitting in his

garden, is among the most familiar of all anecdotes to general readers. This incident, it was affirmed by his niece, as well as his friend Dr.

Pemberton, occurred in Newton's twenty-third year; and it instantly raised

in him the inquiry whether the infinite universe were not held in order

and kept in motion by the very power which drew the apple to the earth.

Galileo had already shown the tendency of all bodies near the earth to

gravitate towards its centre, and had calculated and fixed the proportions

of their speed in descent to their distance from the earth's centre. Newton's general application of Galileo's rule to the planets of the solar

system led him to regard his conjecture as strongly probable. He next

devoted his powers to the consideration of its verity, by examining the

question whether the force of gravitation by which the planets preserved

their orbits and motions round the sun would precisely

account for the moon's preservation of her orbit and motion round the

earth. But here the precision of his calculations was frustrated by the

imperfect knowledge then existing as to the real measurement of the

earth—the gravitating centre of the revolving moon. An empiric would

have trumpeted his discovery to the world, in spite of the fact that this

faulty admeasurement of the earth, by not affording a true calculation of

her gravitating power, failed to lead him to an agreement with truth. Newton was silent for long years, until a degree of the earth's latitude

was ascertained, by actual experiment, to be sixty-nine degrees and a half

instead of sixty; he then resumed his calculations, and their result was

that he had probed the grand secret of the laws by which worlds move in

obedience to the suns which are their centres. It only remains to be

observed, as a significant reminder to the young reader, that—though he

may assent to the great doctrine of Newton, and consider it to be

established, he can never fully know its mathematical and mechanical

verity, unless study enables him to read the "Principia"—the work in

which the truth of gravitation and its laws are demonstrated. Let it be an

additional motive to strive for the ability to read such a book, that, in

having read it, the student has become acquainted with the greatest effort

in abstract truth ever yet produced by the human intellect.

The moral as well as the intellectual grandeur of the life of Newton would

tempt us to enlarge; but we must merely say, ere we pass on, to the

youthful inquirer—read about Newton, think about

Newton, and the more you know of him the more will your understanding

honour him, your heart love him, and your desire strengthen to approach

him in virtue, wisdom, and usefulness.

SIR WILLIAM HERSCHEL

|

|

|

Sir Frederick William Herschel, FRS

(1738—1822) |

Newton's greatest successor in astronomical discovery, may claim an

equality with him, as a true and noble disciple of perseverance. The son

of a poor Hanoverian musician, he was brought over to England, with his

father, in the band of the Guards. The father returned to Hanover, but

young Herschel remained, and at the age of twenty began to seek his

fortune in

this country. After many difficulties, wanderings from place to place, as

a teacher of music in families, and a few slight glimpses of favour from

fortune, he obtained the office of organist in the Octagon Chapel at Bath. The emoluments of this situation, with his receipts from tuition of pupils

and other engagements, were such that an ordinary mortal would have been

content "to make himself comfortable" upon them, in worldly phrase. But

ease and competence were not the object of Herschel's ambition. In the

midst of his wanderings, he had not only striven to acquire a sound

knowledge of English, but of Italian, Latin, and Greek, and had entered on

the study of counterpoint, in order to make himself a profound theorist,

as well as a performer, in music. In order to comprehend the doctrines of

harmonics, he found it necessary to get some acquaintance with the

mathematics; and this led him at once to the line of study for which his

natural genius was best fitted. On his settlement at Bath, he applied

himself with ardour to these abstract inquiries, and from the mathematics

proceeded to astronomy and optics. Desire to view the wonders of the

heavens for himself, made him eager to possess a telescope; and, deeming

the price of a sufficiently powerful one more than he could afford, he set

about making a five-feet reflector, and, after much difficulty,

accomplished his task.

Success only stimulated him to bolder attempts, and he rapidly constructed

telescopes of seven, ten, and

twenty-feet focal distance. Pupils and professional engagements were given

up, until he reduced his income to a bare sufficiency, in order that he

might have more time for the sciences to which he was now become

inseparably attached. So tireless was his perseverance in the fashioning

of mirrors for his telescopes, that he would sit to polish them for twelve

or fourteen hours, without intermission; and, rather than take his hand

from the delicate labour, his sister was requested to put the little food

he ate into his mouth. With one of his seven-feet reflectors—the most

perfect instrument he had constructed—after having been engaged for a

year and a half, at intervals, in a regular survey of the heavens, he at

length made the discovery of the planet which, until the very recent

discovery of "Neptune" by Leverrier and Adams, was regarded as the most

distant member of the solar system. The Astronomer-Royal, Dr. Maskelyne,

to whom Herschel made known what he had observed, together with his doubts

as to the nature of the new celestial body, first affirmed it to be a

comet. In a few months this error was dissipated, and the grandeur of

Herschel's discovery was acknowledged by the whole scientific world. King

George III., in whose honour he had named the new planet Georgium Sidus (a

name which has been very properly set aside for that of Uranus), conferred

upon him a pension of £300 a year, that he might be enabled to give up

entirely the profession of music; and the

son of the poor Hanoverian musician took his station among the first in

the highest of the sciences. The order of knighthood was afterwards

bestowed upon him; but it could not add to the splendour of the names of

either Herschel or Newton.

Inquiry will put the young reader in possession of a knowledge of many

other interesting and important discoveries of the persevering Herschel. A

few pages must be devoted to a brief mention of others who have benefited

mankind by their unremitting labours; and they must be selected from a

list where it is difficult to tell a single name unmarked by some peculiar

excellence—so abundant in exemplars of meritorious toil is the vast

muster-roll of science and mechanical invention.

REAUMUR

|

|

|

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

(1683—1757) |

May be instanced as one of the most industrious toilers for the

advancement of useful science, though he does not take rank with the

unfolders of sublime truths. During a life of seventy-five years he was

incessantly engaged in endeavouring to add something to the compass of

human knowledge and convenience. At one time he is found pursuing an

investigation into the mode of formation and growth of shells,

endeavouring to account for the progressive motion of the different kinds

of testaceous animals; anon, he publishes a "Natural History of Cobwebs," evincing a mind capable of the most

minute and ingenious search; and is afterwards found showing the facility

with which iron and steel may be made magnetic by percussion. For

revealing to his countrymen, the French, a method of converting forged or

bar iron into steel, of making steel of what quality they pleased, and of

rendering even cast-iron ductile, a pension of twelve hundred livres

yearly was settled upon him. This allowance, at his death, was settled, by

his own request, on the Academy of Sciences, to be applied to the

defraying of expenses for future attempts to improve the arts. He also

made known the useful secret of tinning plates of iron, an article for

which the French, till his time, had been compelled to resort to Germany.

Continuing his researches into natural science, he showed the means by

which marine animals attach themselves to solid bodies; discussed the

cause of the electric effect from the stroke of a torpedo; displayed the

proof that in crabs, lobsters, and crayfish, nature reproduces a lost claw; set forth a treatise showing, by experiments, that the digestive process

is performed in granivorous birds by trituration, and in carnivorous by

solution; and published a systematic "History of Insects." Engaged atone

period of life in proving, by experiment, that the less a cord is twisted

the stronger it is—that is, that the best mode of uniting the threads of

a cord is that which causes their tension to be equal in whatever

direction the cord is strained; we find

him, at another period, discovering the art of preserving eggs, so that

they might be kept fresh and fit for incubation many years, and breeds of

fowls propagated at home or abroad, by the eggs being washed with a

varnish of oil, grease, or any other substance that would effectually stop

the pores of the shell, and prevent the contents from evaporating. Valuable secrets in the making of glass were also discovered by him; he

devised a method of making porcelain, and showed that the requisite

materials were to be found in France in greater abundance than in the

East; and lastly, he rendered enduring service to science by reducing

thermometers to a common standard, which continental nations gratefully

commemorate by still calling thermometers by his name. A life passed in

mental occupations, so multifarious as well as useful, surely entitles Reaumur be termed a true scholar of perseverance.

THE HON. ROBERT BOYLE

By a life of virtue and usefulness, merits the

epithet to which his birth by courtesy entitled him. He was the youngest

son of the first Earl of Cork, and, after being educated at Eton, was sent

out to travel on the Continent. A residence at Florence at the time of

Galileo's death, and the almost universal conversation then caused by the

discoveries of that great philosopher, seem to have induced Boyle's first attention to science. On

returning to this country he very soon joined a knot of scientific men,

who had begun to meet at each other's houses, on a certain day in each

week, for inquiry and discussion into what was then called "The New or

Experimental Philosophy." These weekly meetings eventually gave rise to

the Royal Society of London; but part of the original members of the

little club, a few years after its commencement, removed to Oxford, and

Boyle, influenced by his attachment to these philosophic friends, in

process of time took up his residence in that city. Their weekly meetings

were held in his house; and here he began to prosecute with earnestness

his researches into the nature of air. By his experiments and invention,

the air-pump was first brought into so useful a form that he may be called

its discoverer, though the genius of others has since greatly improved

that important instrument. He also demonstrated the necessity of the

presence of air for the support of animal life and of combustion, showing

not only that a flame is instantly extinguished beneath an exhausted

receiver, but that even a fish could not live under it, though immersed in

water. His demonstration of the expansibility of air was still more

important. Aristotle, three hundred years before the Christian era, taught

that if air were rarefied till it filled ten times its usual space, it

would become fire. Boyle succeeded in dilating a portion

of the air of the common atmosphere, till it filled nearly fourteen

thousand times its natural space.

His other discoveries were numerous: every hour of his existence might be

said to be devoted to usefulness: and his wealth and station, so far from

disposing him to ease and inertion, were nobly turned by him into grand

aids for the advancement of knowledge. Mr. Craik thus admirably sums up

his life of effort—- "From his boyhood till his death he may be said to

have been almost constantly occupied in making philosophical experiments;

collecting and ascertaining facts in natural science; inventing or

improving instruments for the examination of nature; maintaining a regular

correspondence with scientific men in all parts of Europe; receiving the

daily visits of great numbers of the learned, both of his own and other

countries; perusing and studying not only all the new works that appeared

in the large and rapidly widening department of natural history and mathematical and experimental physics, including medicine, anatomy, chemistry,

geography, &c., but many others, relating especially to theology and

oriental literature; and, lastly, writing so profusely upon all these

subjects, that those of his works alone which have been preserved and

collected, independently of many others that are lost, fill, in one

edition, six large quarto volumes. So vast an amount of literary

performance, from a man who was at the same time so much of a public

character, and gave so considerable a

portion of his time to the service of others, shows strikingly what may be

done by industry, perseverance, and such a method of life as never suffers

an hour of the day to run to waste."

The lives of Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Galileo, and Kepler, among

astronomers; of Napier of Murchiston, the inventor of logarithms; of

Dolland and Ramsden, the improvers of optical glasses; of Cavendish, the

discoverer of the composition of water; of Linnæus and Cuvier, the

greatest naturalists; of Lavoisier, Fourcroy, Black, and, indeed, a host

of modern chemists; might be singly and in order adduced as inspiring

lessons of perseverance. The young inquirer, if he have caught a spark of

zeal from the ardour of the tireless minds we have hastily endeavoured to

portray, will, if he act worthily, strive to make himself acquainted more

fully with the doings of these and other great men, and "gird up the

loins of his mind" to follow them in their glorious path of wisdom and

beneficence.

MICHAEL FARADAY

|

|

|

Michael Faraday, FRS

(1791–1867) |

Who, by general consent, ranks as one of the greatest of English chemists

and natural philosophers, like many other men who have attained eminence,

was born in poverty, and owed his rise into fame to the perseverance with

which he studied

and the determination to avail himself, to the best of his abilities, of

his opportunities of acquiring knowledge. He was the son of a working

blacksmith, and was born at Newington Butts, London, on the 22nd of

September, 1791. The amount of regular education he received must have

been small; and at an early age he was apprenticed to a bookbinder, an

occupation so far agreeable that it afforded him opportunities of perusing

books to which otherwise he must have been a stranger. Fond as he was of

reading, he took still greater pleasure in the construction of an

electrical machine and other apparatus, the use of which he had learned

probably from some of the books passing through his hands, and with which

he is able to make simple, but to him most interesting, experiments, which

attracted the attention of a gentleman of scientific attainments who

frequently came to his master's shop.

Wonderfully elated Faraday must have been when this gentleman offered

to take him to hear one of Sir Humphry Davy's lectures at the Royal

Institution. Davy was then in the height of his fame, and his admirable

lectures, illustrating the nature of his striking discoveries, attracted

large and brilliant audiences. Michael carefully took notes, and no person

of all that Albemarle Street audience left the place with a keener

appreciation of the value of the lecturer's discoveries. He was then

twenty-one years of age, and already wearied of the mechanical trade by

which he gained his living. Animated by an impulse bold indeed—but it was

the boldness of genius—he ventured to send to Davy the notes he had

taken, accompanied by an expression of his desire to be engaged in some

occupation connected with science. Sir Humphrey, noticing the great ability

shown by the manner in which the notes had been taken, wrote to Faraday in

an encouraging manner, and shortly afterwards offered him the situation of

assistant in his laboratory.

Faraday was now quite at home, and exhibited such talent and readiness

that Sir Humphry selected him to accompany him on a continental tour, as

scientific assistant and secretary. On their return, he was entrusted with

the performance of some experiments which resulted in the discovery of the

possibility of condensing gases into liquids by pressure; and, about 1821,

he made the important discovery of the connection between electricity and

magnetism which is the first of a series of observations on this subject

which, in 1823, procured him the honour of being elected corresponding

member of the French Academy of Sciences, and, in 1825, of being admitted

Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1827, he was appointed to succeed Sir Humphry as lecturer, and in December, 1829, he gave the first of the

Christmas lectures on chemistry which afterwards became so famous. In

1829, he was appointed chemical lecturer at the Royal Military Academy

at Woolwich, a position he occupied for thirteen years.

He was now rapidly achieving fame, and was looked upon as the most rising

man of science of his age. In 1831, he began his numerous contributions to

the "Philosophical Transactions," afterwards republished in three large

volumes, between 1839 and 1845. In 1832, he received the honorary degree

of D.C.L. from the University of Oxford; ten years afterwards he was

elected honorary member of the Academy of Berlin; in 1844, he was chosen

one of the eight foreign associates of the Paris Academy of Sciences, and

many other honours were conferred on him.

The phenomena of electro-magnetism and electric

induction, and their application to the useful arts, were the more

prominent objects of his study; but there was scarcely a subject connected

with physical philosophy that he did not carefully investigate, and on

which his patient research and powerful intellect did not throw some

light. The application of magnetic electricity to lighthouses,

electro-plating, telegraphy, and medical purposes, is in a great measure

due to him; and his researches certainly suggested the investigations

which resulted in the discovery of the electric telegraph and the valuable

aniline dyes. His experiments on the polarization of a ray of light

by electricity were very beautiful. As a lecturer, he was

unsurpassed for lucidity and success in illustrating very abstruse matters by striking and intelligible experiments.

Trained scientific minds were attracted by the closeness of his reasoning;

and children were delighted by the charming clearness with which he made

the elementary truths of science easy to be understood.

In 1835, he received a pension from the State of £300 a year; and, in

1858, the Queen gave him a residence in the palace of Hampton Court. In

character he was singularly gentle and unassuming, deeply impressed with

religious truth, being the member of a small sect of Christians known as Sandemannians, and often preaching at a little chapel in an obscure part

of the Metropolis. He waited patiently and reverently on science,

believing that all truth must be harmonious, and valued his great

discoveries only for the help they ought to give to the world to be better

and happier. He closed his laborious life, a remarkable instance of the

success of perseverance and unselfishness, at Hampton Court on the 25th of

August, 1867, at the age of seventy-six.

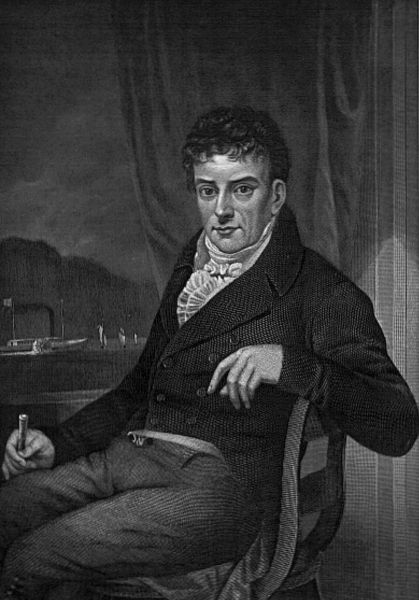

ROBERT FULTON.

|

|

|

Robert Fulton (1765–1815) |

If Fulton could not claim to be the inventor of steamboats, he occupies a

very prominent place among those who first applied steam power to the

purposes of navigation. He was a man of great inventive power, and

persevered, notwithstanding many difficulties, until he had matured his

discoveries.

His parents were poor Irish people who had emigrated to Pennsylvania, and

Robert was born at Little Britain, in that State, in 1765. He had but

little regular education, but read eagerly the books that came in his way. Showing an aptitude for ingenious mechanical work, he was apprenticed to a

jeweller at Philadelphia. He worked assiduously at his trade, and in his

spare time studied painting with such success that, while yet a youth, he

had realized enough money by the sale of portraits and landscapes to

purchase a small farm, in which, his father being dead, he established his

mother.

Having completed his apprenticeship, he left America and came to London,

with the intention of studying art, and worked for several years under the

instruction and supervision of his famous countryman, Benjamin West,

afterwards President of the Royal Academy. His taste for art, however, was

inferior to that for mechanical and engineering pursuits, to which in

course of time he entirely devoted his energies. The skill he

displayed in designing some engineering works in Devonshire obtained for

him the patronage of the Duke of Bridgewater, famous in connection with

the construction of canals, and of Earl Stanhope, so eminent for

mechanical invention. He patented several important inventions,

among them a mill for sawing and polishing marble, and machines for

spinning flax and making ropes; and, in 1795, published a work of

considerable value on the subject of navigable canals.

His talents as a practical engineer had by this time

attracted attention, and, in 1796, he accepted an invitation from the

United States minister at Paris to visit that city, where he remained for

seven years, working hard at various new projects and inventions, one of

the most remarkable of which was a submarine boat, which he named the

Nautilus, and intended to be used in naval warfare for the purpose of

attacking vessels below the water-line. Neither the French nor the

English Governments—for he applied to each—would adopt the invention; and

then Fulton turned his attention to the practical development of a subject

which had long occupied his mind—navigation by steam.

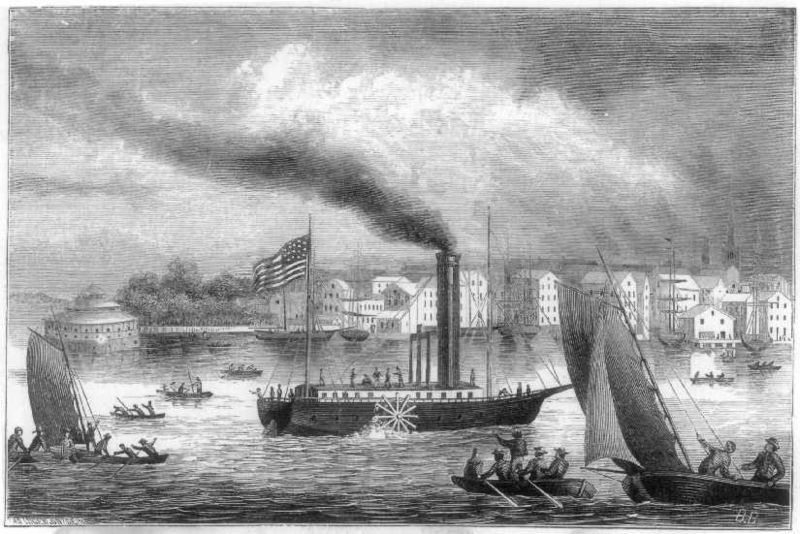

|

|

|

Robert Fulton's steamer, the Clermont, on the

Hudson River, New York, 1807. |

Many attempts had been made with varying degrees of success

to apply the steam-engine as a propelling power for vessels. William

Henry, of Pennsylvania, had constructed a model steamboat forty years

before, and other Americans, Rumsey and Fitch, had made some attempts in

the same direction. In Scotland, Symington had been more successful,

attaining a speed of seven miles an hour, but the experiments led to

little practical result. In 1803, Fulton constructed a small

steamboat, which he exhibited on the Seine; but he failed to obtain the

assistance and encouragement he required; and three years afterwards he

returned to America, where he launched a steamboat on the Hudson, with

machinery supplied by the great English firm of Boulton and Watt, and

achieved a great success. The legislature granted him a patent,

other vessels were constructed; and Fulton obtained a considerable amount

of employment from the United States Government, in connection with canals

and other engineering work.

He lived to see steam-vessels on all the principal rivers of

the States, and his own fame as an engineer and inventor firmly

established. He died in 1815, aged fifty, and an almost national

demonstration of mourning showed the estimation in which he was held by

his fellow-countrymen.

ROBERT DICK.

Some of the ablest naturalists, the most ardent lovers of animals and

flowers, and the most acute observers of geological phenomena, have been

poor working men who, ardently inspired by a love of the subject which has

attracted them, devoted to it the time which others in their class of life

give to recreation and repose, and denying themselves not only the little

indulgences, but even the comforts which their earnings might procure,

spent the few shillings they could save above their absolutely necessary

expenses on the purchase of books, or in obtaining specimens of bird,

flower, or fossil.

A very remarkable type of this intellectual and indomitable

order of men was Robert Dick, a baker, of Thurso, who lived almost

unknown, but whose name became, after his death, a familiar word with men

of science, and all those who can admire a genuine triumph of persevering

energy. He was born in January, 1811, at Tullibody, Scotland, a

village not far from the Forth river, and amidst beautiful scenery.

His mother died soon after his birth, and his father, an exciseman, having

sent the boy to school—where he made such progress, that his friends

suggested he should be helped to a college career—apprenticed him, at the

age of thirteen, to a baker. He worked frequently from three in the

morning till seven or eight in the evening; but even then found time to

read such books as he could obtain. When on his daily rounds,

delivering bread, he noticed the plants by the wayside, and acquired a

considerable amount of knowledge regarding their structure and

peculiarities. When seventeen years old he worked as a journeyman

baker at Leith, and afterwards at Glasgow and Greenock, and after a few

years set up in business for himself at Thurso, where his father then

lived, in the extreme north of Scotland. This was in 1830, and he

remained in the same shop until his death in December, 1866. He

worked hard all day, never neglecting his business, and then started off

on long rambles. As he never married, he had no family ties, and he

formed no companionships. Nature was all in all to him. He

studied the botany and geology of the district; then entomology attracted

him, and he made himself thoroughly acquainted with the natural history of

Caithness. He thought nothing of making a journey of nine or ten

miles, wading through streams and climbing rocks, to obtain a specimen of

some rare plant.

One plant, which he had preserved for twenty years before

making his prize known, proved to be one, the existence of which, in the

British Isles, was much doubted by many eminent botanists, and, indeed,

denied by some, none of them being able to obtain a specimen. In

geology he made some original discoveries, and presented many of his

specimens to Hugh Miller, the eminent

geologist, from whom, and from Sir Roderick Murchison, he received high

praise.

Dick possessed also admirable literary gifts, wrote

vigorously and imaginatively in prose and verse, with a fine feeling for

humour, and an enthusiasm, when writing about his favourite studies, which

communicates itself to the reader.

A very choice collection, illustrative of botany, entomology,

and geology, formed by him, has been presented to the town of Thurso; and

a noble memorial of the baker-naturalist is found in the biography written

by Dr. Samuel Smiles.

Robert Dick was peculiarly situated for the indulgence of his

tastes, and his example could not, without neglect of important social

duties, be followed by all lovers of nature. But the wonders of

creation are not hidden from any, and if we cannot all make collections

and study minutely, we may see enough to impress us with the beauty and

order of creation.

CHAPTER VI.

MEN OF BUSINESS.

EXAMPLES of a successful pursuit of wealth, either

from the beginnings of a moderate fortune, or from absolute penury, are

abundant. A life devoted to the acquirement of money, for its own

sake, cannot be made the subject of moral eulogy; it can only be

introduced among the "Triumphs of Perseverance," as a proof of the

efficacy of that quality of the mind to enable the wealth-winner to

compass his resolves. It by no means follows, however, that a career

towards opulence is impelled by the more sordid passion for gain.

Happily, among those who have started with a moderate fortune, progressive

increase in riches has often been found united with increasing purposes of

the noblest philanthropy and public beneficence; while the manly aim for

independence has equally distinguished many who have risen to wealth from

poverty. A brief rehearsal of the biographies of two persons, of

widely different station and character, but whose names have alike become

inseparably connected with the history of the first commercial city in the

world, will suffice to illustrate our position.

SIR THOMAS GRESHAM,

|

|

|

Sir Thomas Gresham (1519—79)

by Anthonis Mor ca. 1554 |

The younger son of Sir Richard, who was a knight, alderman, sheriff, and

Lord Mayor of London, and a prosperous merchant, had the twofold example

set him by his father, of an intelligent pursuit of trade, and of public

spirit and munificence. He was sent to Cambridge, distinguished

himself in study, and might, undoubtedly, have risen to reputation in one

of the learned professions; but, by his father's wish, he turned his

attention to business, and was admitted a member of the Mercers' Company

at the age of twenty-four. Having, through his father's eminence as

a merchant, succeeded in obtaining the trust of agent to King Edward the

Sixth, for taking up money of the merchants of Antwerp, he quickly

discerned the abuses under which the king's interest suffered. He

proposed methods for preventing the Flemish merchants from extorting

unfair commissions and brokages, and so turned the current of advantage to

the king's favour, that the young prince was enabled to pay all the debts

for which his father and the Protector—Somerset—had left him responsible.

During the short reign of Edward, this active and enterprising merchant

made forty journeys from England to Antwerp; and, by the application of

his genius, retrieved English commerce from the disadvantage into which it

had fallen by mismanagement at home, and the superior shrewdness of the

Netherland merchants. The precious metals had become scarce in our

country, but Gresham brought them back again; our commodities were low in

price, and foreign ones high, but he reversed their conditions of sale:

while the king's credit, from being very low abroad, was, by Gresham's

shill, raised so high, that he could have borrowed what sums he pleased.

For such services the young and acute negotiator had a pension of £100 a

year appointed him for life, and estates to the value of £300 a year were

also conferred upon him by the king.

At the accession of Mary, Gresham was discharged from his

agency; but, on his drawing up a memorial, and its allegements being

proved, he was re-instated. Queen Elizabeth immediately re-engaged

him, at her accession, and employed him to provide and buy up arms for the

national defence. She knighted him a year afterwards, and he then

built himself the mansion known by his name in Bishopsgate Street; and,

till lately, occupied by the "Gresham professors."

His noblest public work was performed soon after. His

father had striven to move King Henry the Eighth to build an Exchange for

the city merchants, who then met in the open air in Lombard Street, but

could not. Sir Thomas Gresham now publicly proposed, if the citizens

would purchase a piece of ground large enough, and in the proper place, to

build an Exchange at his own expense, with covered walks, and all

necessary conveniences for the assemblage of merchants. This was

done; the site was cleared; Gresham himself laid the foundation-stone; and

Queen Elizabeth, when the building was complete, "attended by nobility,

came from Somerset House, and caused it, by trumpet and herald, to be

proclaimed the 'Royal Exchange."' This building, as our young

readers know, was burnt down some years ago, and the present stately

fabric, opened by Queen Victoria, has been erected on its site.

|

|

|

The third and

present Royal Exchange opened by Queen Victoria in 1844. |

About the time that the building of the Royal Exchange was

commenced, Gresham was again employed to take up moneys for the royal use

at Antwerp. Experience had so fully shown him the evil of pursuing

this system, that he at length persuaded the queen to discontinue it, and

to borrow of her own merchants in the city of London. Yet his views

were so much in advance of the contracted commercial spirit of that age,

that the London citizens, in their common hall, blind to their own

interests, negatived his proposition when it was first made to them.

But, on more mature consideration, several merchants and aldermen raised

£16,000, and lent it to the queen for six months, at six per cent.

interest; and the loan was prolonged for six months more, at the same

interest, with brokage. This illustrious London citizen, by his

superior intelligence, thus opened the way for increasing others' as well

as his own gains.

Sir Thomas Gresham's successful negotiations issued in so

large an increase of his own wealth, that he purchased large estates in

several counties, and bought Osterley Park, near Brentford, where he built

a large mansion, in which he was accustomed to receive the visits of

Elizabeth. Even here the ideas of the merchant were predominant.

"The house," says a writer of the period, "standeth in a parke, well

wooded and garnished with many faire ponds, which affoorded not onely fish

and fowle, as swannes and other water fowle, but also great use for milles,

as paper milles, oyle milles, and corn milles." On his retirement to

Osterley, he transformed his residence in Bishopsgate Street into a

"college," for the abode of seven bachelor professors, who were to read

lectures there on "divinity, law, physic, astronomy, geometry, music, and

rhetoric," and to have £50 each per year.

He was the richest commoner in England—such were what is

usually termed "the substantial" rewards of his perseverance; while his

name deserves lasting honour as the patron of learning, and the exemplar

of merchant-beneficence. He left, by will, not only ample funds for

continuing his "professorships," but endowments for almshouses, and yearly

sums for ten of the city prisons and hospitals.

JAMES LACKINGTON,

The son of a journeyman shoemaker and of a weaver's daughter, passed his

early years amidst circumstances which must have enduringly impressed him

with the miseries of vice and poverty. His father was a selfish and

habitual drunkard, and his mother frequently worked nineteen or twenty

hours out of the four-and-twenty to support her family. He was the

eldest child of a numerous family, and was put two or three years to a

dame's school; but was less intent on learning than on "getting on in the

world," even while a boy. He heard a pieman cry his wares, and soon

proposed to a baker to sell pies for him; and so successful did young

Lackington prove as a pie-vender, that he heard the baker declare, a

twelvemonth after, that he had been the means of extricating him from

embarrassment. A boyish prank put an end to this engagement; and

when the baker wished to renew it, Lackington's father insisted on placing

him at the stall. Again, however, his pedler inclinations, which in

after life led him to affluence, rescued him from the disagreeable

treatment he expected to receive under his father's rule. He heard a

man cry almanacks in the street, and importuned his father till he

obtained leave to start on the same itinerant enterprise. In this he

succeeded so well that he deeply aggrieved the other venders, who, as he

tells us in his very whimsical but interesting biography, would have "done

him a mischief had he not possessed a light pair of heels." Resolute

on not continuing at home, he persuaded his father, at length, to bind him

apprentice with a shoemaker in a neighbouring town, and at fourteen years

of age sat down to learn his trade.

We will not follow this singular specimen of human nature,

spoilt by want of education and by evil example, through all the vagaries

of his youth. Taking him up at four-and-twenty, after he had

experienced considerable changes in religious feeling, and gathered some

smatterings of knowledge from reading, we find him marrying, and beginning

the world the next morning with one halfpenny. Yet he and his wife

set cheerfully to work, he tells us; and by great industry and

self-denial, they not only earned a living, but paid off a debt of forty

shillings, which was somewhat summarily claimed by a friend of whom he had

borrowed that sum. Trials very soon fell to his lot which tended to

make him deeply thoughtful. His wife was ill for six months; and, at

the end of that period, he was compelled to remove her from Bristol to

Taunton, for her health's sake. During two years and a half the poor

woman was removed five times to and from Taunton without permanent

recovery; and Lackington, despairing of an amendment of his circumstances

under such discouragements, resolved to leave his native district.

He therefore gave his wife all the money he had, except what he thought

would suffice to bring him to London; and, mounting a stage-coach, reached

town with but half-a-crown in his pocket. He got work the next

morning, saved enough in a month to bring up his wife, and she had

tolerable health, and obtained "binding work" from his employer.

Lackington was now fairly entered on the path to prosperity.

His partner was a pattern of self-denial and economy; they began to save

money, bought clothes, and then household furniture, left lodgings, and

had a house of their own. A friend, not long after, proposed that

Lackington should take a little shop and parlour, which were "to let" in

Featherstone-street, City-road, and commence master shoemaker.

Lackington agreed, but also formed the resolution to sell old books.

With his own scanty collection, a bagful of old volumes he purchased for a

guinea, and his scraps of leather, altogether worth about £5, he

accordingly commenced master tradesman. He soon sold off, and

increased his stock of books; and next borrowed £5. of John Wesley's

people—"a sum of money kept on purpose to lend out for three months,

without interest, to such of their society whose characters were good, and

who wanted temporary relief." Much to his shame he traduces the

character of the philanthropic Wesley and of his brother religionists, in

his "Confessions," even while acknowledging that this benevolent loan was

"of great service" to him. He afterwards endeavoured to make the

amende honorable, but the mode in which it was made was as unadmirable

as his ungrateful offence. But, to return to his narrative.

"In our new situation," says he, "we lived in a very frugal

manner, often dining on potatoes, and quenching our thirst with water,

being determined, if possible, to make some provision for such dismal

times as sickness and shortness of work, which had often been our lot, and

might be again." In six months he became worth five-and-twenty

pounds in old book stock, removed into Chiswell-street, to a more

commodious shop, though the street, he says, was then (in 1775) a dull

street, gave up shoemaking, "turned his leather into books," and soon

began to have a great sale. Another series of reverses, during which

his wife died, his shop was closed, while he himself was prostrate with

fever, and was robbed by nurses, only served to sharpen his intents and

strengthen his perseverance, when he recovered. His second marriage,

with an intelligent woman, he found of immense advantage, since his new

partner was a very efficient helpmate in the book-shop. Next, his

friend Dennis became partaker in his business, and advanced a small

capital, by which they "doubled stock," and printed their first catalogue

of 12,000 volumes. They took £20 the first week, and Dennis then

advanced £200 more towards the trade; but, after two years, Lackington was

left once more to himself, his friend being weary of the business. A

resolution not to give credit gave him great difficulty, he says, for at

least seven years, but he carried his plan at last, principally by selling

at very small profits. His business premises were successively

enlarged, and his sales likewise, until his trade and himself became

wonders. At the age of fifty-two he went out of business, leaving

his cousin head of the firm. He sold 100,000 volumes annually,

during the latter years of his personal attention to trade, kept his

carriage, purchased two estates, and built himself a genteel house.

He once more became a professor of religion, on retiring from business,

and built several chapels. He was, in the close of life, benevolent

in visiting the sick and indigent, and in relieving the distressed.

|

|

|

"The Temple of the Muses"

The bookshop opened by James Lackington

(1746–1815), at No. 32, Finsbury Place South |

"As the first king of Bohemia kept his country shoes by him

to remind him from whence he was taken," says the bookseller, in his

"Confessions," "so I have put a motto on the doors of my carriage,

constantly to remind me to what I am indebted for my prosperity, viz.,

'Small profits do great things;' and reflecting on the means by which I

have been enabled to support a carriage, adds not a little to the pleasure

of riding in it." Alluding to the stories that were rife respecting

his success, attributing it to his purchasing a "fortunate

lottery-ticket," or "finding bank-notes in an old book," he says, very

emphatically, "I found the whole that I am possessed of, in—small

profits, bound by industry, and clasped by economy." |