|

[Previous

Page]

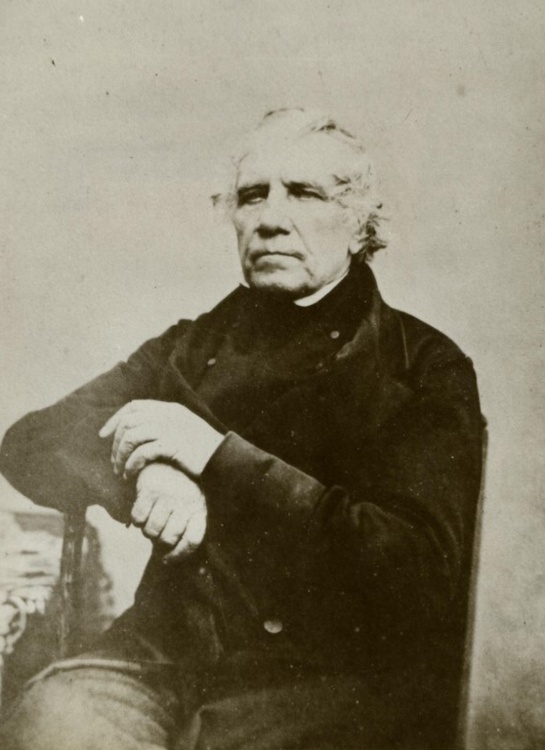

SAMUEL BAMFORD.

Samuel Bamford (1788-72: handloom weaver, radical, poet

and author.

SAMUEL BAMFORD, the handloom weaver of

Lancashire, is a true specimen of the poet of the working class. Into his heart the sacred fire of poetry has descended, and the music of his lyre is not the less sweet that his mind has been tempered, and his affections tried, by persecution and suffering.

Nor has stern poverty, which, for many of the best years of his life, condemned him to work hard and fare meanly, in any wise served to close his eyes or ears to the beauties and melodies, of nature, whose spirit-whispers have spoken eloquently to his soul on the mountain-side, and in his home-valley; and which have often found for themselves beautiful and cheerful echoes in his songs and lyrics.

Bamford is a Lancashire man born and bred,—an

inheritor of that sturdy spirit of independence, which the indomitable old Saxons carried with them into the forests and

morasses of South Lancashire, when driven thither before the superior discipline and prowess of the mailed Norman

men-at-arms,—a spirit which they have retained to the present day.

The inhabitants of the south-western districts of Lancashire are a robust, manly, industrious, shrewd, and

hard-headed race. They have peculiar physical characteristics, and their moral features correspond to them.

They inhabit a rugged and naturally barren district; deemed unworthy of being taken possession of by the followers of the Norman

William, who, having possessed themselves of the rich pasturelands of the low country, drove their former occupiers into the morasses of the interior, and the forests of Pendle and

Rossendale. The conquerors then built fortresses at the entrances of all the valleys commanding the "wild" district, at the mouths of the Ribble, the Lune, and the Mersey, the ruins of which are still to be seen; and thus they hemmed in the Saxon foresters who would not consent to resign their independence.

It was long, indeed, before their resistance to the Norman authority entirely ceased; and in all great popular movements, even down to our own day, the men of these

districts have usually been among the foremost. In the civil wars of the

Stuarts,—more especially during the "Great Rebellion" in Charles the First's

time,—the inhabitants of the Lancashire forests were almost to a man on the side of the

Parliament; and the first open encounter in which blood was shed took place at Manchester, then, as now, the great metropolis of the district.

Bradshaw, President of the Council of the Commonwealth, one of the purest of the great public men of that period, was born in the forest of Rossendale, in the midst of a bold and freedom-loving population, and in a

district calculated to develop the republican tendencies of his nature.

Indeed, the resistance which the people of that district have uniformly offered to the ascendant aristocratic power may be regarded as part of the same struggle

between Norman and Saxon which formerly ravaged the country. And to this day, it still is, in some measure, a struggle of races as well as of classes.

The institutions of the Conqueror have never been heartily recognized; the Church which it offered has been rejected, almost the whole population being even now extreme Dissenters.

The recent Anti-Corn-Law agitation, which originated with and was virtually carried by the men of Lancashire, was a striking instance of the hereditary resistance offered even to this day, by the men of Saxon descent, to the institutions of the conquerors.

In such a district, and amid such a people, was Samuel Bamford born.

Though sprung from poor and hard-working parents, we find in one of his books, presently to be mentioned, that he claims gentle blood; the elder branch of the lords of Bamford, from whom our poet is descended, having lost his lands by rebellion against the king during the civil wars, whilst the loyal younger brother, at the Restoration, obtained possession of the estate.

The birthplace of the subject of our sketch was the town or village of Middleton, near Manchester, where he first saw the light, in February, 1788.

His parents were poor but respectable, and were deeply imbued with religious feelings, belonging to the then new sect which followed John Wesley.

His mother, like the mothers of most men of strength of character and

intellect, was a remarkable woman,—and to a strong mind in her were united a great tenderness and delicacy of feeling, which caused her no less to sympathize with others in

distress, than to be sensitive of wrongs received by herself and her family from proud and unfeeling relations.

The father having succeeded in obtaining a situation in the Manchester workhouse, the family removed thither; but small-pox and fever suddenly fell upon them, and in a very short time two of the children were carried off by the one, and Bamford's mother and uncle by the other.

His father having contracted a second marriage which turned out most unhappily for the children, they were shortly after sent out into the world to make their way as they

could; "shorn to the very quick." Samuel had, however, by this

time—about his tenth year—acquired the art of reading, and already become a devourer of such books as he could obtain. His school education was very scanty, but it was sufficient for his purpose then.

He read all sorts of romantic legions and ballads, varied by Wesley's Hymn's, and Hopkins and Sternhold's Psalms, on Sundays.

An old cobbler, whose acquaintance he made, taught him tunes to such

ballads as "Robin Hood" and "Chevy Chace;" and also excited his wonder, by remarkable ghost-stories, and accounts of fairies, witches, and wonderful apparitions, in all of

which—like most of the Lancashire peasantry of that day—he was a rigid believer.

Bamford, after leaving his father's home at this early age, was taken to reside with an uncle and aunt at Middleton, where the monotony of the bobbin-wheel and the loom soon cast a shade over his buoyant spirits.

A merely mechanical, gin-horse employment, like that now before him, was

intolerable to his mind; and he seized the opportunity of every piece of out-of-doors drudgery which presented itself to escape from his hated in-doors occupation.

The relations with whom he lived were, like his parents, of the Methodist persuasion.

They regularly attended chapel and class, and were frequently visited by the ministers on the circuit.

Jonathan Barker, a first-rate preacher, was one of the favourites.

Jabez Bunting, then a very young preacher, excited great expectations, but when in the pulpit he had a most unseemly way of winking both eyelids at once, like two shutters, which caused some mirth and much

observation amongst the youngsters as to the cause of it. John Gaulter was always heard with pleasure, both in the pulpit and out of it.

He imparted an interest to whatever he said, by introducing anecdotes, short narratives, and other apt illustrations of his subjects; and if it became of an affecting turn, as it was almost sure to do, the good man and his

congregation generally came to a pause amid tears. He and Mr. Barker had no slight influence on the feelings,

convictions, and opinions of Bamford, in his after years.

The Sunday school connected with this place of worship Bamford, of course, had to attend with the other members of the family.

He was one of the Bible-class, and was probably a better reader than any person about the place except the preacher.

The only things he desired to be taught were writing and arithmetic, and as he felt his want, particularly of writing, and was anxious to get on, he was placed at a desk, and after a copy or two of "hooks and O's," he began to write "joynt hand," as it was termed in the homely phrase of his instructor; and from that time he made his own way in self-culture.

Meanwhile time passed, and Bamford was promoted from the bobbin-wheel to the loom; turning out a good and ready weaver.

He became more reconciled to his condition, and, as if to vary its sameness, love, which is seldom absent where the spirit of poetry is present (and he was imbued with that), now made approaches in an unmistakable form, and to him proved an angel both of light and of darkness.

More than one tender acquaintance was formed in succession, and the romantic susceptibility of his temperament seldom permitted him to remain uninfluenced by some "Cynosure of

neighbouring eyes." But this sort of life could not be continued without leading to temptations which require the

guardianship of better angels than Bamford had the grace to invoke.

The usual consequences followed, and regret and deep humiliation were the dregs found at the bottom of his cup of sweetness.

The evil example also, and conversation of reckless

acquaintances, corrupted his better nature, and a wild and perilous course of life ensued.

Feeling but little satisfaction at home, he resolved to seek it in far other scenes abroad.

In the nineteenth year of his age he entered into an engagement with a large ship-owner at Shields; and went on board his brig, the Eneas, engaged in the coasting-trade betwixt Shields and London.

A storm of three days was the first circumstance that welcomed him to the ocean.

Many vessels were lost in that storm; and though the old sailors on board said nothing to him, and but little to each other, he could not but remark the expressive looks which they interchanged.

He remained some time with this vessel, and made a number of voyages coastwise, but the almost irresponsible power of the captain, and his capricious use of it, disgusted Bamford, as it was sure to do, with his situation and with the seaservice in general.

He accordingly embraced an opportunity of leaving the ship at London, and set out on foot to walk the journey homewards into Lancashire.

At St. Albans he was stopped and questioned by a press-gang, and escaped only by his presence of mind, and the fortunate circumstance that the commander of the party could not read writing.

Bamford reached home a more thoughtful man than he had left it.

He now obtained a situation in a warehouse at Manchester, and having, at times, considerable leisure, he resumed his habits of reading.

"Cobbett's Register" was now amongst the prose-works which he read with avidity, and those of Shakespeare and Burns were the chief poetical

ones,—the latter being his especial favourite. He was now, if possible, more imbued with romance than ever, and when not at his place in the warehouse he lost no opportunity of seeking out "fresh woods and pastures new."

Manchester and its suburbs were not then what they are now. The heights of Cheetwood were rural knolls, with quiet dells out in the country.

Cromsal, with its undulating pastures and gentle slopes, was interlaced with meadow and field walks, where one might have "wandered many a day," without being disturbed by unwelcome observation.

Broughton, with its old Roman Causey, its Giant-stone, and its woodlands, offered a complete labyrinth of by-paths, shady lanes, and quaint cottages, with vines, rose-bushes, and creepers trailing down from the

thatch,—to say nothing of those delightful domestic attractions which are always found in cottages which are happy, and in gardens that are like Paradise.

We now come to the middle life of Bamford, during which he took a prominent part in the stirring political movements of his time, some forty years ago.

This portion of his life is to be found detailed in a remarkably graphic and deeply interesting book which he has published, and by which he is chiefly known beyond the range of his own district, entitled "Passages in the Life of a Radical."

This is truly a remarkable book,—written with great force and brilliancy, teeming with fine poetic descriptions of rural scenery,

wonderful in its delineations of character and its descriptions of persons, which are hit off, like Retsch's outlines, almost at a

stroke,—in other parts, shrewd, homely, and humorous,—and, again, earnest, emphatic, and truly eloquent in the advocacy of the best means of elevating the condition of the great body of workmen to whom the author belongs.

But the chief value of the book, in our estimation, is in that it is a true and faithful

history of a deeply eventful period in the political life of

England,—not of the heads of parties and leaders of factions, but of the masses of his

industrious countrymen,—portrayed by a leading actor in the stirring events which he describes.

We have had many lives of Pitt, and lives of Canning, and lives of this, that, and the other party leader; but the humble political life of Samuel Bamford, modestly entitled "Passages in the Life of a Radical," gives a truer insight into the life and political condition of the English people in recent times, than all the lives of political leaders that we know of put together.

Bamford begins his political life with the

introduction of the Corn Bill, in 1815,—one of the first-fruits of that

long series of victories and havoc which covered Britain with "glory,"

the aristocracy with stars and ribbons, and the people with taxes.

Waterloo had just been fought; the banded kings of Europe had hunted

Napoleon from his throne; and the lords of England proceeded at once to

celebrate their triumph by the enactment of a Corn Law. Riots took

place in most of the large towns,—in London and Westminster, Bridport,

Bury, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Glasgow, Dundee, Nottingham, Birmingham,

Walsall, Preston, and numerous other places. The public mind

was deeply excited, and organized political agitation commenced.

Cobbett's writings were extensively read among the working classes, and

he directed their attention to the main cause of the then misgovernment,

in the corruption of Parliament and the insufficient representation of

the people. Hampden Clubs were formed in the towns, villages, and

districts of the country, which gathered around them the active spirits

of the time. One of these clubs was established at Middleton, in

1816, of which Samuel Bamford, by reason of his knowledge of reading and

writing, was chosen Secretary. Religious services were connected

with the political discussions of the members; and the influence of the

clubs extended over almost the entire working population. Meetings of

delegates from various parts of Lancashire took place, and the

organization of the movement rapidly spread. Some members of the clubs

went out as missionaries, Bamford being himself frequently sent to rouse

the inactive in remote parts. When these Hampden Clubs had been

sufficiently extended over the country, a general meeting of delegates

was summoned, to be held in London, under the presidency of Sir Francis

Burdett, about the beginning of the year 1817. Bamford attended as

a representative of the Middleton Club, and while in London he had

interviews with most of the leading "Reformers," graphic descriptions of

many of whom are given in his "Passages." Bamford again returned

to Middleton, with a report of his mission; but by this time the alarm

of the government was excited, and the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended.

Then followed the infatuated "Blanket Expedition," to which Bamford was

always opposed: still worse, destructive physical force projects were

recommended. The usual consequences followed: public

meetings were put down, and secret ones took place; spies went among the

people, blowing the embers of rebellion; apprehensions of the suspected

followed; and Bamford, among others, was arrested on suspicion of high

treason, carried across the Manchester "bridge of tears," and imprisoned

in the New Bailey. Nothing can be more interesting than Bamford's

description of his wanderings in company with his odd friend, "Doctor

Healey," among the moors and morasses of the wild districts of South

Lancashire, in their attempts to evade apprehension, and of their after

confinement and adventures in the New Bailey. Here is the portrait

which he gives of himself, his wife, and family, at this period.

Of himself:—

"Behold him then. A young man, twenty-nine years of age; five feet ten inches in height; with long, well-formed limbs, short body, very upright carriage, free motion, and active and lithe rather than strong. His hair is of a deep dun colour; coarse, straight, and flakey; his complexion a swarthy pale; his eyes gray, lively, and observant; his features strongly defined and irregular, like a mass of rough and smooth matters, which, having been thrown into a heap, had found their own subsidence, and presented, as it were by accident, a profile of rude good-nature, with some intelligence. His mouth is small; his lips a little prominent; his teeth white and well set; his nose rather snubby; his cheeks somewhat high; and his forehead deep and rather heavy about the eyes."

Then follows Bamford's portrait of his home, his wife, and his

children:—

"Come in from the frozen rain, and from the night wind, which is blowing the clouds into sheets, like torn sails before a gale. Now down a step or two.

'T is better to keep low in the world, than to climb only to fall.

"It is dark, save when the clouds break into white scud; and silent, except the snort of the wind, and the rattling of hail, and the eaves of dropping rain.

Come in! A glimmer shows that the place is inhabited; that the nest has not been rifled whilst the bird was away.

"Now shalt thou see what a miser a poor man can be in the heart's treasury.

A second door opens, and a flash of light shows we are in a weaving-room, clean and flagged, and in which are two looms with silken work of green and gold.

A young woman, of short stature, fair, round, and fresh as Hebe, with

light brown hair escaping in ringlets from the sides of her clean cap,

and with a thoughtful and meditative look, sits darning beside a good

fire, which sheds warmth upon the clean-swept hearth, and gives light

throughout the room, or rather cell. A fine little girl, seven

years of age, with a sensible and affectionate expression of

countenance, is reading in a low tone to her mother:

"'And he opened his mouth and taught them, saying, Blessed are the poor in spirit; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn; for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are they who hunger and thirst after righteousness; for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful; for they shall obtain mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart; for they shall see God. Blessed are the peacemakers; for they shall be called the children of God.

Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness' sake; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are ye when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you for my sake.'

"Observe the room and its furniture. An humble but cleanly bed, screened by the dark, old-fashioned curtain, stands on our left.

At the foot of the bed is a window closed from the looks of all passers.

Next are some chairs, and a round table of mahogany; then another chair, and next it a long table, scoured very white.

Above that is a lookingglass, with a picture on each side, of the Resurrection and Ascension, on glass, 'copied from Rubens.'

A well-stocked shelf of crockery-ware is the next object; and in the nook near it are a black oak carved chair or two, with a curious desk or box to match: and lastly, above the fire-place are hung a rusty basket-hilted sword, an old fusee,

and a leathern cap. Such are the appearance and furniture of that

humble abode. But my wife!

|

'She looked; she reddened like the rose;

Syne, pale as ony lily.' |

Ah! did they hear the throb of my heart, when they sprung to embrace me? my little loving child to my knees, and my wife to my bosom.

"Such are the treasures I had hoarded in that lowly cell.

Treasures that, with contentment, would have made into a palace

|

'The lowliest shed

That ever rose on England's plain.' |

They had been at prayers and were reading the Testament before retiring to rest.

And now, as they a hundred times caressed me, they found that indeed 'Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.'"

Such was the home, and such the domestic treasures, from which Bamford was torn, to be immured in a jail.

But he did not remain long in the Manchester New Bailey. He was sent to London, the "Manchester Rebels" exciting no small degree of interest in the towns through which they passed.

They were lodged in Borough Street prison, and shortly after their arrival were examined before Sidmouth, Castlereagh, and others of the Privy

Council; and after a short residence in Coldbath Fields prison, and several other examinations before the Council, the prisoners were

discharged, as no case could be made out against them. Bamford reached home, and for a time found happiness in the bosom of his family.

But political excitement continued to have its attractions for him, and again he engaged with greater

ardour than ever in the movements of the day. "I now," he says, "went to work, my wife weaving beside me, and my little girl, now doubly dear, attending school or going short errands for her mother.

Why was I not content? What would I more? What could mortal enjoy beyond a sufficiency to satisfy hunger and

thirst,—apparel to make him warm and decent,—a home for shelter and

repose,—and the society of those I loved? All these I had, and still was

craving,—craving for something for 'the nation,'—for some good for every

person,—forgetting all the while to appreciate and to husband the blessings I had on every side around me."

Political agitation recommenced on the termination of the Habeas Corpus Act suspension, and immediately Bamford was in the midst of it.

Hunt came down to Manchester, and a row took place at the theatre; female political unions were started; and almost the whole population became enlisted in the movement.

At length a series of great public meetings was projected, the first of which was to be held at Manchester on the 16th of August, 1819.

The men in the mean time were drilling themselves by night, in marching, counter-marching, and military evolutions.

They were divided into companies under captains and drill-masters,—so, at least, said the depositions before the

magistrates,—and they were, it was further rumoured, ready for the most desperate deeds.

Not so, however, does Samuel Bamford think of the intentions of the agitators; their sole object being, he says, to excite public respect by the regularity of their march and the orderliness of their

demeanour.

The 16th of August arrived. Streams of men, marching in regular order, poured into Manchester, with bands of music and banners flying, from all the

neighbouring towns and villages. Bamford went thither with the

rest,—one of the leaders of six thousand marching men, whom "he formed into a hollow square, at the sound of a bugle," and addressed on the importance of preserving order, sobriety, and peace during that eventful day.

The meeting was one of great magnitude, and was held in St. Peter's Field, nearly on the spot where the great Free-Trade Hall now

stands,—the principal banners (remarkable coincidence!) having

inscribed on them "No Corn-Laws!"

The business of the meeting had scarcely commenced when "a noise and strange murmur arose towards the church, and a party of cavalry in blue and white uniform came trotting, sword in hand, round the corner of the gardenwall, and to the front of a row of new houses, where they reined up in a line."

"On the cavalry drawing up they were received with a shout of goodwill, as I understood it.

They shouted again, waving their sabres over their heads; and then, slackening rein, and striking spur into their steeds, they dashed forwards, and began cutting the people.

"Stand fast!" I said, "they are riding upon us, stand fast.

And there was a general cry in our quarter of 'Stand fast!' The cavalry were in confusion; they could not, with all the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; their sabres were plied to hew a way through naked held-up hands, and defenceless heads; and then chopped limbs, and wound-gaping skulls were seen; and groans and cries were mingled with the din of that horrid confusion.

'Ah! ah!' 'For shame! for shame!' was shouted. Then 'Break! break! they are killing them in front, and they cannot get away!'

And there was a general cry of 'Break!' For a moment the crowd held back in pause; then was a rush, heavy and resistless as a headlong sea; and a sound like low thunder, with screams, prayers, and imprecations from the crowd-moiled and sabre-doomed who could not escape.

"On the breaking of the crowd, the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing wherever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Many females appeared as the crowd opened; and striplings and mere youths also were found. Their cries were piteous and heart-rending, and would, one might have supposed, have disarmed any human resentment; but here their appeals were vain.

"Women, white-vested maids, and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled; and we have reason for believing that few were the instances in which that forbearance was vouchsafed which they so earnestly implored.

"In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space.

The sun looked down through a sultry and motionless air. The curtains and blinds of the windows within view were all closed.

A gentleman or two might occasionally be seen looking out from one of the new houses before mentioned, near the door of which a group of persons (special constables) were collected, and apparently in conversation; others were assisting the wounded, or carrying off the dead.

"The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flagstaves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two drooping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. The yeomanry had

dismounted,—some were easing their horses' girths, others adjusting their accoutrements, and some were wiping their sabres. Several mounds of human beings still remained where they had fallen, crushed down, and smothered. Some of these were still

groaning,—others with staring eyes were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe more.

"All was silent, save those low sounds and the occasional snorting and pawing of the steeds.

Persons might sometimes be noticed peeping from attics and over the tall sidings of houses, but they quickly withdrew, as if fearful of being observed, or unable to sustain the full gaze of a scene so hideous and abhorrent."

Such is Bamford's graphic account of the "Massacre at Peterloo," as it is still called in the neighbourhood.

The author was too much mixed up with the movement to escape detection, and he was again apprehended and imprisoned in Manchester New Bailey, from which he was transferred to Lancaster Castle.

He was shortly after liberated on bail, to take his trial at the next York assizes.

In the mean time, he proceeded to London, with the view of obtaining some connection with the press.

Disappointment was in every case the result; and after a ramble through the rural

districts of England, and being reduced to great poverty in London, he returned to Lancashire to prepare for his trial at York. Bamford defended himself with great shrewdness and skill, conducting his case with much propriety.

The result, however, much to the astonishment of the court, was that he was found "Guilty," and was bound in recognizances to appear in London the ensuing Easter, at the Court of King's Bench, to receive his sentence.

He returned for a short time to Middleton, and on his way home, at Oldham, he met his wife and child.

Bamford's journey to London on foot was full of incident and adventure, and his description of it reminds one of some of the best passages in Fielding and Smollett's novels.

His adventures among the booksellers, hunting for a publisher; his cold and inhospitable treatment by Hunt and the London "patriots;" the impending destitution with which he was threatened; the suspense connected with his sentence; constitute a most painful relation, though told in a highly graphic style.

He was eventually sentenced to another twelve months' imprisonment in Lincoln jail, which he endured, comforted by the sympathy and aid of many kind friends, but also pained by the calumnies and slander of secret enemies.

At length he was liberated, and in company with his wife, a noble-hearted woman, whom Bamford invariably speaks of in terms of the warmest affection, he walked homewards to his native

village,—his sixth and his last imprisonment at an end. On leaving the prison, he left "Old Daddy," the turnkey, his pair of Lancashire clogs, at which he "expressed great delight, saying he would place them in his collection of curiosities."

Before leaving, the magistrates and the governor complimented Bamford and his fellowprisoners on their good behaviour; and Bamford in return thanked them sincerely for their kindness during his confinement.

He went northwards by Great Markham, Worksop, and Sheffield, up the beautiful vale of Hathersage, past Peveril's Castle of the Peak, to Chapel-on-the-Frith, Stockport, Manchester, and then home. "We entered Middleton," he says, "in the afternoon, and were met in the streets by our dear child, who came running, wild with delight, to our arms.

We soon made ourselves comfortable in our own humble dwelling; the fire was lighted, the hearth was clean swept, friends came to welcome us, and we were once more at home!"

We have left ourselves little room to speak of Bamford's writings as a poet.

Yet here one might descant at considerable length. Many of his best pieces were written in prison; and he has since added to them from time to time.

The last edition of his poems was published in 1843, and we regret to perceive that he has excluded from it many productions which, though inferior to those retained, and deemed

unworthy of republication by their author, are nevertheless valuable as marking the historical features of the period at which they were written, as well as showing the gradual development of the poet's mind.

A kindly feeling, however, seems also to have influenced Bamford in the selection.

"Many topics," he says in his Preface to this last edition, "of exciting public interest, which the author does not wish to be a means for perpetuating, are either totally omitted, or considerably modified.

This may disappoint some of our pertinacious friends, but neither can that be avoided, except by the sacrifice of a good and rightful feeling; if we learn not to forget and forgive, how can we expect to be forgiven?—how can we pray, 'Forgive us our trespasses as we have forgiven those that trespassed against us'?"

Of all the poems of Bamford, the most touching, in our opinion, are his "Lines Addressed to my

Wife,"—equal almost to the "Miller's Daughter" of Tennyson,—the "Verses on the Death of his Child," and "God Help the

Poor,"—lines such as none but a man who has known and lived amongst poverty could have written.

Take the following two verses:—

|

God help the poor! An infant's feeble wail

Comes from yon narrow gateway; and behold

A female crouching there, so deathly pale,

Huddling her child, to screen it from the cold!

Her vesture scant, her bonnet crushed and torn,

A thin shawl doth her baby dear enfold:

And there she bides the ruthless gale of morn,

Which almost to her heart hath sent its cold!

And now she sudden darts a ravening look,

As one with new hot bread comes past the nook;

And, as the tempting load is onward borne,

She weeps. God help thee, hapless one forlorn!

God help the poor!

God help the poor, who in lone valleys dwell,

Or by far hills, where whin and heather grow!

Theirs is a story sad indeed to tell;

Yet little cares the world, and less 't would know

About the toil and want they undergo.

The wearying loom must have them up at morn;

They work till worn-out Nature will have sleep;

They taste, but are not fed. The snow drifts deep

Around the fireless cot, and blocks the door;

The night-storm howls a dirge across the moor,—

And shall they perish thus, oppressed and lorn?

Shall toil and famine hopeless, still be borne?

No! GOD will yet arise and HELP THE POOR! |

Bamford's "Pass of Death," written on the death of George Canning, has also been much admired.

Ebenezer Elliott, in his "Defence of Modern Poetry," has said of this

piece: "I have an imperfect copy of a poem, written by an artisan of Oldham, to which, I believe, nothing equal can be found in all the plebeian authors of antiquity, with Æsop at their head." Take one or two stanzas:—

|

The sons of men did raise their voice

And cried in despair,

We will not come, we will not come,

Whilst Death is waiting there!'

But Time went forth and dragged them on

By one, by two, by three;

Nay, sometimes thousands came as one,

So merciless was he.

*

*

* *

For Death stood in the path of Time

And slew them as they came,

And not a soul escaped his hand,

So certain was his aim.

The beggar fell across his staff,

The soldier on his sword;

The king sank down beneath his crown,

The priest beside the word.

And Youth came in his blush of health,

And in a moment fell;

And Avarice, grasping still at wealth,

Was rolled into hell.

And some did offer bribes of gold,

If they might but survive;

But he drew his arrow to the head,

And left them not alive!" |

For many years Bamford continued to work at his trade of a hand-loom weaver at Middleton, occasionally enlivening his

labours at the loom with exercises of the pen. He wrote out and published his "Passages in the Life of a Radical," and many of his best poetical pieces, such as his "Wild Rider,"

Béranger's "La Lyonnaise," and "The Witch o' Brandwood."

More recently he has written an interesting little volume, entitled "Walks in South Lancashire," in which he gives many highly instructive sketches of the moral and physical condition, interspersed with descriptions of the domestic life, of the industrious classes of his

neighbourhood. From one of the chapters in this last work, entitled "A Passage of my Later Years," we find that Bamford was personally instrumental, in 1826, in preventing a mischievous outbreak and destruction of machinery, which would certainly have been accompanied with great loss of life (as the military were on the alert) in his native place.

Indeed, Bamford, towards his later years, invariably set himself determinedly against all physical force projects, which some of the working class political leaders were but too ready to recommend, and their admirers but too ready to follow.

In the note to his "La Lyonnaise," which he published in 1839, when the physical force policy was in considerable favour, he says, alluding to the sentiment which runs throughout

Béranger's poem: "Unfortunately for the too brave French, their common appeal against all grievances has been, 'To arms!'

And their indomitable poet naturally falls in with the sentiment of the nation.

By arms, in three days, (the 'glorious' ones,) they obtained freedom! and

they lost it in one!—a lesson to make the heart bleed, were it not perhaps sternly necessary to admonish mankind, that, without high wisdom and entire self-devotion, mere

valour is helpless, as a blind man without his guide. It is true the middle and upper classes have not dealt justly towards you (the working class).

All ranks have been in error as respects their relative obligations, and prejudice has kept them strangers and apart.

But the delusion is passing away like darkness before the sun; and knowledge, against which gold is powerless, comes like the spreading day, raising the children of toil, and making their sweat-drops more

honourable than pearls."

And in a "Postscriptum" to his volume of poems,

Bamford thus concludes: "The salvation of a people must come at last from their own heads and hearts.

Souls must be matured, giving life to healthful minds. Hands may be learned to use weapons, and the feet to march, but the warriors who take freedom and keep it

MUST BE ARMED FROM WITHIN."

Bamford eventually gave up working at his loom, and maintained himself for some time by his pen.

An appointment which he obtained in a public office in London, followed by a pension from the government against which, when a younger man, he had so often been in rebellion, have enabled him to spend his declining years in peace and comfort in his native village of Middleton, where he still lives.

――――♦――――

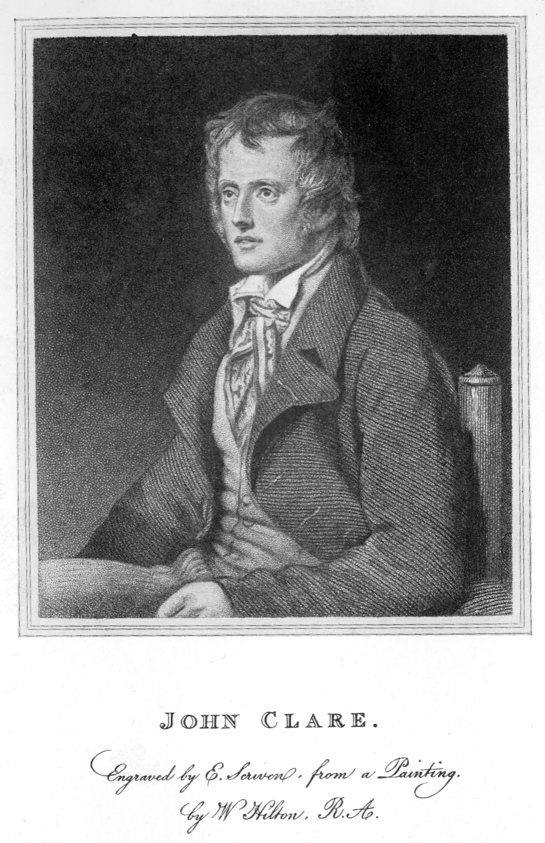

JOHN CLARE.

John Clare (1793-1864): major English poet.

AMONG the uneducated

poets of England, who have risen up from the humblest ranks, and poured

the melody of their poetry into the world's ear, John Clare will ever

hold a distinguished place. The gifts of nature are of no rank or order;

they come unbidden and unsought; as the wind wakens the chords of the

Æolian harp, so the spirit breathes upon the soul, and brings its music

to life. It is not necessary to graduate at a university to see

nature with a poetic eye. The heart can be fed elsewhere than in

the schools; Nature and Life are better teachers. Even the poor

man, who daily toils for bread, may be surrounded by natural harps that

yield the sweetest music; he may even catch higher utterances from the

spirit-whispers that speak to his soul from the leafy wood, the purling

brook, or the mist-capped mountain, than have ever been awakened by the

finger or the mind of the most highly-cultured man.

It is not often, however, that the peasant has overleaped the

barriers of his class, and vindicated his claim as an author to the

poetic wreath. He may be a true poet, struggling for utterance,

deep thoughts lying brooding within him quick with life; but the hand of

poverty lies heavy on him; he is a labourer, and has to work for bread;

his lot forbids contemplation, ease, and study; perhaps he is

uneducated, and his mental apprehension is impeded by early neglect.

If he has struggled on, and risen into the region of authorship, perhaps

he finds he has mounted into a sphere where he has no natural

supporters; where he is petted, patronized, perhaps spoiled; and where,

severed from the class to which he naturally belonged, he floats adrift

upon the surface of society, without a definite place or function, ill

at ease, miserable, and sometimes frantic with disappointment. He

may wear the crown which he has won; but, while to some it may look

green, he feels it burning around his brows like fire. The painful

instances of the Scottish peasant poets—Burns, Tannahill, and Thom—will

at once start up before the mind's eye. Nor are those of the

English peasant poets—Bloomfield, Kirke White, and Clare—less

melancholy, the fate of the last, still living, being the most unhappy

of all. He is, and has been for many years, subject to the

restraints of a lunatic asylum.

John Clare is a child of genius, a born poet, inspired by

nature, but destroyed by the world. His poetry is not the result

of books, but of loving intercourse with the flowers, the woods, the

fields, "the common air, the sun, the skies." His poems are

thoroughly original; there is nothing hackneyed nor commonplace about

them; you see in them at once that he has looked on nature with his own

eyes, loving her with his whole heart. He seizes incidents in the

fields, features in the flowers, aspects of the skies and the clouds,

which less faithful and accurate observers had entirely overlooked.

In this admiration of nature he is earnest almost to an excess.

His poems present a perfect calendar of rural on-goings, of atmospheric

beauties, of the life of the flowers, woods, and fields. While he

lived in the presence of nature, and worshipped her with deep passion,

he had also a loving eye for the common people among whom he

lived,—their customs, their loves, their griefs, and their amusements;

and these he has immortalized in his verse, linking nature and humanity

together in one golden chain.

The life of Clare presents a striking and affecting example

of the pursuit of knowledge under difficulties; but it also furnishes an

exceedingly painful illustration of the misery which is occasionally

produced by the gift of poetry descending upon a mind struggling in a

humble station, and without the requisite means of development and

sustenance. John Clare was born at Helpstone, a village near

Peterborough, Northamptonshire, in 1793; his father was a crippled

day-labourer, afterwards a parish pauper. He obtained no

education, save what he gave to himself; and he contrived, by working

extra hours as a ploughboy, to obtain, in about eight weeks, as many

pence as would pay for a month's schooling. John Clare educated

himself; but he was no common youth; in multitudes of cases similar to

his own, in England, children grow up altogether illiterate, and remain

so through life. He learned to read; and at thirteen he

"ambitioned" buying a book. He had seen a copy of Thomson's

Seasons, and hoarded up a shilling for the purpose of buying it.

The shilling was accumulated by slow degrees, and at last it was saved.

What a fever of delight he was in all that night! he could scarcely

sleep; he was up by daylight, and away to Stamford, six or seven miles

off, brushing the early dew of the fields in that bright spring morning.

When he reached the town, the shopkeepers were still abed, and there

stood John Clare at the bookseller's door, waiting impatiently the

taking down of the shutters. What a picture of boyish enthusiasm

and thirsting genius! Well, the book was purchased, carried

lovingly away in the hand, put into the pocket, then taken out again,

and the leaves turned over and gazed into wistfully. Then he

hurried homeward full of joy. No wonder he felt inspired then!

And so, as he passed on through the beautiful scenery of Bingley Park,

with the sky shining overhead, and the birds carolling in mid-air, and

all nature fresh and fair and beautiful, the peasant-boy composed his

first piece of poetry, "The Morning Walk." He was unable to muster

funds to procure paper, but he could carry the verses in his head.

Nor could he write, even though he had been rich enough to buy paper.

But a kindly-hearted exciseman, feeling an interest in the youth, took

him in hand, and taught him writing and arithmetic; so, in course of

time, he was enabled to commit his verses to paper.

"Most of his poems," says the memoir prefixed to his first

volume,

"were composed under the immediate impression of his

feelings in the fields, or on the road-sides. He could not trust

his memory, and therefore he wrote them down with a pencil on the spot,

his hat serving him for a table; and if it happened that he had no

opportunity soon after of transcribing these imperfect memorials, he

could seldom decipher them, or recover his first thoughts. From

this cause, several of his poems are quite lost, and others exist only

in fragments. Of those which he had committed to writing,

especially his earlier pieces, many were destroyed from another

circumstance, which shows how little he expected to please others with

them. From a hole in the wall of his room, where he stuffed his

manuscripts, a piece of paper was often taken to hold the kettle with or

light the fire!"

He was twenty-four years old when he bethought him of risking

the publication of a volume. He was then working as a labouring

man at Bridge Casterton, in Rutlandshire. By dint of hard working,

day and night, he managed to save a pound, for the purpose of printing a

prospectus. This was done, and "A Collection of Original Trifles"

was announced. Only seven subscribers were got! But one of

his prospectuses got into the hands of a bookseller at Stamford, through

whom Taylor and Hessey, their publishers in London, were induced to

publish the book, and, what was more, they gave the poet £20 for the

copyright. They were published with the title of "Poems

descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, by John Clare, a Northamptonshire

Peasant." The little volume created quite "a sensation" in

literary circles. It was hailed, as it deserved to be, as a truly

original book. Highly favourable notices appeared in the leading

reviews, and the author was sought up. Great men took him by the

hand, sent for him to their houses, and made him presents of money.

Visitors came to see him working in the fields; the vulgar curiosity

that runs agape after every notorious thing, from a poet to a parricide,

ran after Clare; he was no longer his own master, but a kind of public

property; he had written a book, and everybody thought it but right that

be should be exhibited to them. The result, however, was, that his

circumstances improved. His second book, "The Village Minstrel,"

appeared about four years after his first; and what with the profits of

this work and the presents made to him by Earl Fitzwilliam, Lord John

Russell, the present King of the Belgians, Lord Radstock, and others,

his income amounted to about forty pounds a year. On the strength

of this, he married his "Patty of the Vale," the daughter of a humble

farmer; and, with his young wife, and his poor and infirm parents, he

then enjoyed a pleasant cottage in his native village, and basked, for a

time, in the sunshine of prosperity.

But the notoriety he had acquired had awakened in him a love

of excitement which the quiet village could but ill satisfy. In

1824 he went to London, where he became one of the contributors to the

London Magazine, and began to mix in the society of literary men,

and to be petted at the brilliant parties of the lion-hunting. De

Quincey met him in London, and furnishes the following reminiscence:

"By a few noble families and his liberal publishers, he

was welcomed in a way that, I fear, from all I heard, would but too much

embitter the contrast with his own humble opportunities of enjoyment in

the country. The contrast of Lord Radstock's brilliant parties,

and the glittering theatres of London, would have but a poor effect in

training him to bear that want of excitement which even already, I had

heard, made his rural life but too insupportable to his mind. It

is singular that what most fascinated his rustic English eye was, not

the gorgeous display of English beauty, but the French style of beauty,

as he saw it among the French actresses in Tottenham Court Road.

He seemed, however, oppressed by the glow and tumultuous existence of

London; and, being ill at the time, from an affection of the liver,

which did not, of course, tend to improve his spirits, he threw a weight

of languor upon any attempt to draw him out into conversation. One

thing, meantime, was very honourable to him, that, even in this season

of dejection, he would uniformly become animated when anybody spoke to

him of Wordsworth,—animated with the most hearty and almost rapturous

spirit of admiration. As regarded his own poems, this admiration

seemed to have an unhappy effect of depressing his confidence in

himself. It is unfortunate, indeed, to gaze too closely upon

models of colossal excellence."

On his return into the country, matters did not improve with

poor Clare. Unfortunately, he speculated in farming, which he

could not manage; a large family grew up around him, his means were

frittered away, and he fell back almost into his original state of

poverty, his mind unsettled, his nerves unstrung, and in a state of

almost hopeless despondency. He published a third volume of poems

in 1839, entitled "The Rural Muse," probably the best of all his works.

But he had ceased to be a novelty; the public were no longer astonished

by him, as they had been at first; and the book had but a small sale.

Indeed, we have heard that it scarcely paid the expenses of its

publication. All this preyed upon his mind. His genius did

not sustain him; it only embittered his misery. He was the victim

of nervous despondency, which ended in a complete unsettlement of the

state of his mind, so that confinement in a private asylum at length

became necessary.

There he has now been for many years, writing poetry at lucid

intervals, which shows that he still retains all that minute and

delicate descriptive power which formerly marked his productions.

He has written songs and verses addressed to his Patty, his mind

contemplating her as in youth; all the dark intervening period which had

brought age and sorrow upon both being blotted out. Friends have

occasionally visited him in his confinement, and found him harmless and

docile, though occasionally labouring under strange hallucinations.

He once fancied himself to be a great prize-fighter, and that he wore

the belt. He would rave about matches to come off, and of his

antagonists, who were men most of them long since dead. He would

also describe the deaths, executions, and murders of distinguished

personages of former times, and fancy himself to have been an eyewitness

of them. Through all this, his early love of nature and rural

scenery often burst forth in enthusiastic description, coloured with the

rainbow hues of poetry.

John Clare is entitled to a high place, if not to the

highest, among the "uneducated" poets of England. His keen

observation of nature amounted to a genius; his delicacy in painting

natural objects, whether a flower, a tree, a sunset, or a spring scene,

was next to marvellous. He owed little to books, but wrote from

his heart. He saw things with the eye of a true poet, and as he

observed, so did he write. Some of his expressions are extremely

delicate. Take the following as an instance:—

|

"Brisk winds the lightened branches shake,

By pattering, plashing drops confessed,

And, where oaks dripping shade the lake,

Paint crimping dimples on its breast." |

How well he paints the cottage fireside too,—the farmer

reading the news by the tavern Ingle, the blacksmith at his anvil, the

reapers in the corn-field, the maid a-milking the kine, and the quiet

and beauty of rural life! He has many delicious pictures of the

approach of spring, the advent of summer, the rich glory of autumn, and

the stern gloom of winter. Here is a stanza, taken from a poem

descriptive of the first breath of spring:—

|

"The sunbeams on the hedges lie,

The south-wind murmurs summer soft;

The maids hang out white clothes to dry

Around the elder-skirted croft.

A calm of pleasure loiters round,

And almost whispers winter by;

While fancy dreams of summer's sound,

And quiet rapture fills the eye." |

We conclude with a piece which, though by no means one of his

best, we select because of its convenient length for the purpose of

quotation.

|

"The snow has left the cottage top,

The thatch-moss grows in brighter green;

And eaves in quick succession drop,

Where grinning icicles have been,

Pit-patting with a pleasant noise

In tubs set by the cottage door;

While ducks and geese, with happy joys,

Plunge in the yard-pond, brimming o'er.

"The sun peeps through the window-pane,

Which children mark with laughing eye;

And in the wet street steal again,

To tell each other spring is nigh.

Then, as young hope the past recalls,

In playing groups they often draw,

To build beside the sunny walls

Their spring-time huts of sticks or straw.

"And oft in pleasure's dreams they hie

Round homesteads by the village side,

Scratching the hedgerow mosses by,

Where painted pooty shells abide;

Mistaking oft the ivy spray

For leaves that come with budding spring;

And wondering, in their search for play,

Why birds delay to build and sing.

"The mavis thrush with wild delight,

Upon the orchard's dripping tree,

Mutters, to see the day so bright,

Fragments of young hope's poesy;

And oft dame stops her buzzing wheel

To hear the robin's note once more,

Who toddles while he pecks his meal

From sweetbrier hips beside the door." |

――――♦――――

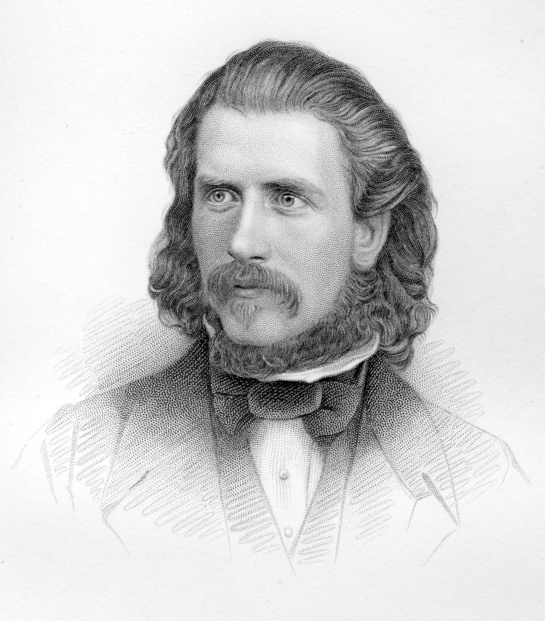

GERALD MASSEY.

|

Gerald Massey

(1828-1907): English Chartist, minor poet, literary

critic and essayist, lecturer, and

researcher into ancient Egyptian mythology and its

influence on Christianity and Judaism. |

THE

reader of the miscellaneous literature of the day has doubtless met with the name of Gerald Massey

attached to poems strikingly beautiful in language and intensely passionate in feeling. These poems have heretofore been

published chiefly in journals which are yet in a great measure

tabooed in what are regarded as "respectable literary circles." The "Spirit of Freedom," a cheap journal,

started in 1849, and written exclusively by working-men, contained

a large number of them; and others have since appeared in the "Christian Socialist," a cheap journal

conducted by Clergymen of the Church of England; and many others also, of great beauty, have been published

in the "Leader," a remarkably able journal conducted by Thornton Hunt, the son of the poet.

You see at once that the writer is a man of vivid

genius, and is full of the true poetic fire. Some of his earlier pieces are indignant expostulations with society at the

wrongs

of suffering humanity; passionate protests against those hideous disparities of life which meet our eye on

every side; against power wrongfully used; against fraud and oppression in their more rampant forms; mingled

with appeals to the higher influences of knowledge, justice, mercy, truth, and love. It is always thus with the poet

who has worked his way to the light through darkness, suffering, and toil. Give a poor down-trodden man

culture,

and, in nine cases out of ten, you only increase his sensitiveness to pain: you agonize him with the sight of

pleasures which are to him forbidden; you quicken his sense of despair at the frightful inequalities of the human

lot. There are thousands of noble natures, with minds which, under better circumstances, would have blessed

and glorified their race, who have been for ever blasted—crushed

into the mire-or condemned to courses of desperate guilt!—for one who, like Gerald Massey, has

nobly risen above his trials and temptations, and triumphed over them. And when such a man does find a voice, surely

"rose-water" verses and "hot-pressed" sonnets are not to be expected of him: such things are not by any means

the natural products of a life of desperate struggling with poverty. When the self-risen and self-educated man

speaks and writes now-a-days, it is of the subjects nearest to his heart. Literature is not a mere intelligent epicurism

with men who have suffered and grown wise, but a real, earnest, passionate, vehement, living thing-a power to

move others, a means to elevate themselves, and to emancipate

their order. This is a marked peculiarity of our times; knowledge is now more than ever regarded as a power to

elevate, not merely individuals, but classes. Hence the most intelligent of working-men at this day are intensely

political: we merely state this as a fact not to be disputed. In former times, when literature was regarded mainly in the light of a rich man's luxury, poets who rose

out of the working-class sung as their patrons wished. Bloomfield and Clare sang of the quiet beauty of rural

life, and painted pictures of evening skies, purling brooks, and grassy meads. Burns could with difficulty repress

the "Jacobin" spirit which burned within him; and yet even he was rarely, if ever, political in his tone. His

strongest verses, having a political bearing, were those addressed to the Scotch Representatives in reference to the

Excise regulations as to the distillation of whiskey. But come down to our own day, and mark the difference:

Elliot, Nichol, Bamford, the author of "Ernest," the Chartist Epic, Davis the "Belfast Man," De Jean, Massey,

and many others, are intensely political; and they defend themselves for their selection of subjects as Elliot did,

when he said, "Poetry is impassioned truth; and why should we not utter it in the shape that touches our

condition

the mostly closely-the political?" But how it happens that the writings of working-men now-a-days so

generally assume the political tone, will be best ascertained

from the following sketch of the life of Gerald Massey:—

He was born in May, 1828, and is, therefore, barely twenty-five years of age. He first saw the light in a

little stone hut near Tring, in Herts, one of those miserable

abodes in which so many of our happy peasantry—their

country's pride!—are condemned to live and die. One shilling a week was the rent of this hovel, the roof

of which was so low that a man could not stand upright in it. Massey's father was, and still is, a canal boatman,

earning the wage of ten shillings a week. Like most other peasants in this "highly-favoured Christian

country,"

he has had no opportunities of education, and never could write his own name. But Gerald Massey

was blessed in his mother, from whom he derived a finely-organized brain and a susceptible temperament. Though quite

illiterate, like her husband, she had a firm, free spirit—it's

broken now!—a tender yet courageous heart, and a pride of honest poverty which she never ceased to cherish. But she needed all her strength and courage to bear up under the privations of her lot. Sometimes the husband

fell out of work; and there was no bread in the cupboard, except what was purchased by the labour of the elder

children, some of whom were early sent to work in the neighbouring silk-mill. Disease, too, often fell upon the

family, cooped up in that unwholesome hovel: indeed, the wonder is, not that our peasantry should be diseased, and

grow old and haggard before their time, but that they should exist at all in such lazar-houses and cesspools.

None of the children of this poor family were educated in

the common acceptance of the term. Several of them were sent for a short time to a penny school, where the

teacher and the taught were about on a par; but so soon as they were of age to work, the- children were sent to

the silk-mill. The poor cannot afford to keep their children at school, if they are of an age to work and earn

money. They must help to eke out their parents' slender gains, even though it be only by a few pence weekly. So,

at eight years of age, Gerald Massey went into

the silk-manufactory,

rising at five o'clock in the morning, and toiling there till half-past six in the evening; up in the

grey dawn, or in the winter before the daylight, and trudging to the factory through the wind or in the snow;

seeing the sun only through the factory windows; breathing an atmosphere

laden with rank oily vapour, his ears deafened by the roar of incessant wheels;—

|

"Still

all the day the iron wheels go onward,

Grinding life down from its mark;

And the children's souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark." |

What a life for a child! What a substitute for tender prattle, for childish glee, for youthful playtime! Then

home shivering under the cold, starless sky, on Saturday nights, with 9d.,

1s., or ls. 3d., for the whole week's

work; for such were the respective amounts of the wages earned by the child labour of Gerald Massey.

But the mill was burned down, and the children held jubilee over it. The boy stood for twelve hours in the

wind, and sleet, and mud, rejoicing in the conflagration which thus liberated him. Who can wonder at this?

Then he went to straw-plaiting,—as toilsome, and perhaps,

more unwholesome than factory work. Without exercise, in a marshy district, the plaiters were constantly

having racking attacks of ague. The boy had the disease for three years, ending with tertian ague. Sometimes

four of the family, and the mother, lay ill at one time, all crying with thirst, with no one to give them drink, and

each too weak to help the other. How little do we know of the sufferings endured by the poor and struggling

classes of our population, especially in our rural districts! No press echoes their wants, or records their sufferings;

and they live almost as unknown to us as if they were the inhabitants of some undiscovered country.

And now take, as an illustration, the child-life of Gerald Massey. "Having had to earn my own

dear bread," he says, "by the eternal cheapening of flesh and blood thus early, I never knew what childhood meant. I had no childhood. Ever since I can remember, I have had the aching fear of want, throbbing heart and brow

The currents of my life were early poisoned, and few, methinks, would pass unscathed through the scenes and

circumstances in which I have lived; none, if they were as curious and precocious as I was. The child comes into

the world like a new coin with the stamp of God upon it; and

in like manner as the Jews sweat clown sovereigns, by hustling them in a bag to get gold-dust out them, so is

the poor man's child hustled and sweated down in this bag of society to get wealth out of it; and even as the impress

of the Queen is effaced by the Jewish process, so is the image of God worn from heart and brow, and day by day

the child recedes devil-ward. I look back now with wonder,

not that so few escape, but that any escape at all, to win a nobler growth for their humanity. So blighting are

the influences which surround thousands in early life, to which I can bear such bitter testimony."

And how fared the growth of this child's mind the while? Thanks to the care of his mother, who had sent him to the penny school, he had learnt to read, and the desire to read

had been awakened. Books, however, were very scarce. The Bible and Bunyan were the principal; he committed

many chapters of the former to memory, and accepted all Bunyan's allegory as bond fide history. Afterwards he

obtained access to "Robinson Crusoe" and a few Wesleyan

tracts left at the cottage. These constituted his sole reading, until he came up to London, at the age of

fifteen, as an errand-boy; and now, for the first time in his life, he met with plenty of books, reading all that came

in his way, from "Lloyd's Penny Times," to Cobbett's Works, "French without a Master," together with English,

Roman, and Grecian history. A ravishing awakenment ensued,—the delightful sense of growing knowledge,—the

charm of new thought,—the wonders of a new world. "Till then," he says,

"I had often wondered why I lived at all,—whether

|

'It was not better not to be,

I was so full of misery.' |

Now

I began to think that the crown of all desire, and the sum of all existence, was to read and get knowledge. Read I read I read! I used to read at all possible times, and in all possible places; up in bed till two or three in

the morning, nothing daunted by once setting the bed on fire. Greatly indebted was I also to the bookstalls, where

I have read a great deal, often folding a leaf in a book, and returning the next day to continue the subject; but

sometimes

the book was gone, and then great was my grief! When out of a situation, I have often gone without a meal

to purchase a book. Until I fell in love, and began to rhyme as a matter of consequence, I never had the least

predilection for poetry. In fact, I always eschewed it; if I ever met with any, I instantly skipped it over, and passed

on, as one does with the description of scenery, &c., in a novel. I always loved the birds and flowers, the woods

and the stars; I felt delight in being alone in a summer-wood,

with song, like a spirit, in the trees, and the golden sun-bursts glinting through the verdurous roof; and was

conscious of a mysterious creeping of the blood, and tingling

of the nerves, when standing alone in the starry midnight,

as in God's own presence-chamber. But until I began to rhyme, I cared nothing for written poetry. The

first

verses I ever made were upon 'Hope,' when I was utterly hopeless; and after I had begun, I never ceased for

about four years, at the end of which time I rushed into print."

There was, of course, crudeness both of thought and expression in the first verses of the poet, which were

published

in a provincial paper. But there were nerve, rhythm, and poetry; the burthen of the song was, "At eventime it

shall be light." The leading idea of the poem was the power of knowledge, virtue, and temperance, to elevate the

condition of the poor,—a noble idea, truly. Shortly after he was encouraged to print a shilling volume of "Poems

and Chansons," in his native town of Tring, of which some 250 copies were sold. Of his latter poems we shall

afterwards

speak.

But a new power was now working upon his nature, as might have been expected,—the power of opinion, as

expressed in books, and in the discussions of his fellow-workers.

"As an errand-boy," he says, "I had of

course, many hardships to undergo, and to bear with much tyranny; and that led me into reasoning upon men and things, the causes

of misery, the anomalies of our societary state, politics, &c., and the circle of my being rapidly out-surged. New

power came to me with all that I saw, and thought, and read. I studied political works,-such as Paine, Volney,

Howitt, Louis Blanc, &c., which gave me another element to mould into my verse, though I am convinced that a

poet

must sacrifice much if he write party-political poetry. His politics must be above the pinnacle of party zeal; the

politics of eternal truth, right, and justice. He must not waste a life on what to-morrow may prove to have been

merely the question of a day. The French Revolution of 1848 had the greatest effect on me of any circumstance

connected with my own life. It was scarred and blood-burnt

into the very core of my being. This little volume of mille is the fruit thereof."

But, meanwhile, he had been engaged in other literary work. Full of new thoughts, and bursting with aspirations

of freedom, he started, in April, 1849, a cheap journal, written entirely by working-men, entitled, "The

Spirit of Freedom:" it was full of fiery earnestness, and half of its weekly contents were supplied by Gerald Massey

himself, who acted as editor. It cost him five situations

during the period of eleven months,—twice because he was detected burning candle far on into the night, and

three times because of the tone of the opinions to which

he gave utterance. The French Revolution of 1848 having, amongst its other issues, kindled the zeal of the

working-men in this country in the cause of association,

Gerald Massey eagerly joined them, and he has

been

recently instrumental in giving some impetus to that

praiseworthy movement,—the object of which is to permanently

elevate the condition of the producing classes,

by advancing them to the status of capitalists as well as

labourers.

Massey

photographed shortly before his death in 1907.

A word or two as to Gerald Massey's recent

poetry. Bear in mind that he is yet but a youth;—at twenty-three

a man can scarcely be said fairly to have entered his manhood;

and yet, if we except Robert Nichol, who died at

twenty-four, we know of no English poet of his class, who

has done any thing to compare with him. Some of his

most beautiful pieces originally appeared in the columns

of the "Leader." They give you the idea of a practised

hand-one who has reached the full prime of his poetic

manhood. Take, for instance, his "Lyrics of Love," so

full of beauty and tenderness. Nor are his "Songs of

Progress" less full of poetic power and beauty.

Gerald Massey is a teacher

through the heart. He is familiar with the passions, and leans towards the tender

and loving aspect of our nature. He takes after Burns

more than after Wordsworth, Elliot rather than Thomson. He is but a young man, though lie has had crowded into

his twenty-three years already the life of an old man. He has won his experience in the school of the poor, and

nobly earned his title to speak to them as a man and

a brother, dowered with "the hate of hate, the scorn of

scorn, the love of Love." [p.448]

――――♦――――

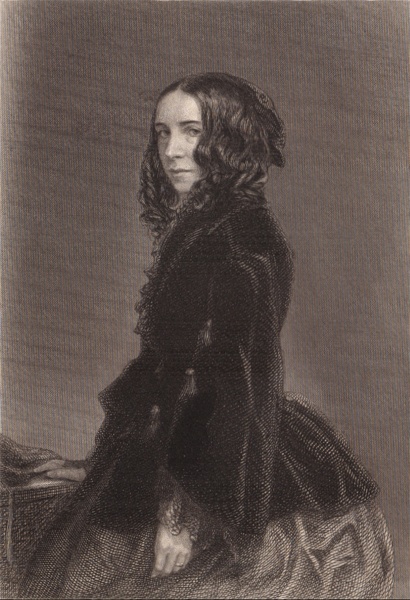

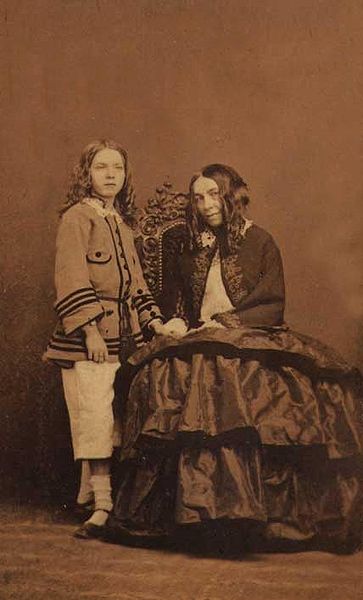

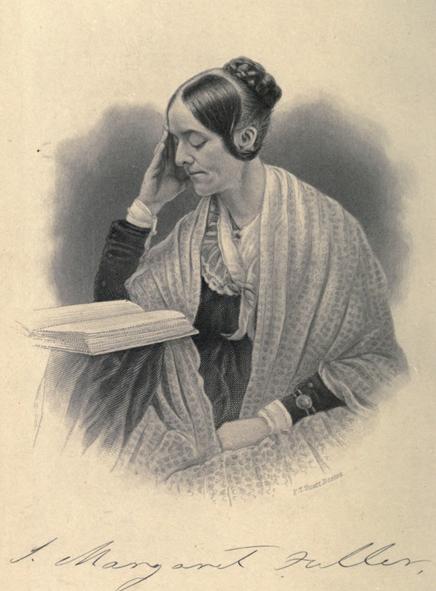

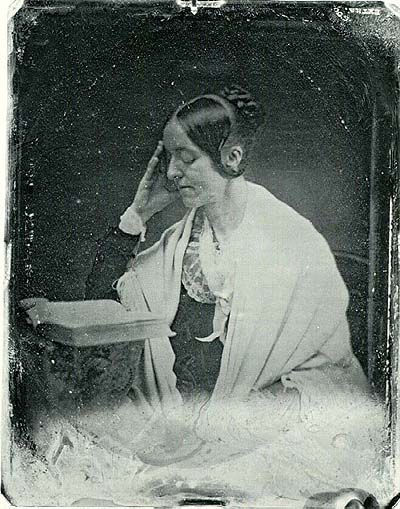

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING.

Elizabeth Barrett (1806-61): major English poet;

wife of the poet

Robert Browning. Picture Wikipedia.

FEMALE poets

hold, at this day, a more distinguished place in our literature, and

their works occupy a larger space in our libraries, than at any

previous period in literary history. Women who write are no

longer regarded as a questionable sisterhood, nor are their works

noticed merely with fine words by way of courtesy. They have

made good their position as honourable literary workers, and thereby

entitle themselves to our respect; and their poems demand notice and

receive the meed of approbation by right rather than by favour.

Nor do we know of any land that possesses a choir of poetesses equal

to our own. France and America possess sweet singers, indeed;

but we defy the world combined to equal our songstresses. And

yet our race of female poets may almost be said to have begun with

Joanna Baillie, a woman of our own day. Unquestionably she was

a great writer, as strong as a man, but with all the delicate purity

and sweetness, the instinctive quickness and fine sensibility, of a

woman. After her, the most distinguished and popular was Mrs.

Hemans, a great lyrist, a true poet,—a pure and high-minded woman.

What exquisite pathos is there in her "Graves of a Household," on

reading which few parents can resist shedding a tear; and her

"Treasures of the Deep" and "The Coming of Spring" are familiar in

our mouths as household words. Indeed, Mrs. Hemans may be said

to have founded a school of poetry, which has even more ardent

followers and admirers in America than in England. The young

and devout love to resort thither when they desire to raise their

hearts by sonorous heroics, or to soften them by the familiar pathos

of certain well-known strains. After Mrs. Hemans came Miss

Landon, who deliciously improvised her beautiful songs, and then

passed away from sight like a bright meteor. But she left

behind her many strong and clear singers,—true women, and great

poets. Need we do more than name Mrs. Southey, Mrs. Howitt,

Mrs. Butler, Mrs. Norton, and—perhaps greatest of all—Mrs. Browning?

We do not know much of Mrs. Browning, except what we can

gather from her published works. It is now some twenty years

since a translation, privately circulated, of Æschylus's "Prometheus

Bound," by a young lady, was favourably spoken of in one or two

literary circles. It indicated a remarkable sympathy on the

part of the translator for the sculptural old Greek drama; and

displayed, also, an accurate knowledge of the dead language, almost

wonderful in so young a writer, and that writer a young lady.

The Preface was, however, perhaps the most curious part of the book;

for it was so crowded full of thoughts and meanings, one jostling

the other so hard for outlet, that none was completely seen, and the

utterance remained comparatively unintelligible. Speaking of

this part of Miss Barrett's published works, Mrs. Browning, in the

preface to her collected edition of 1850, thus writes:

"One early failure, a translation of the 'Prometheus'

of Æschylus which, though happily free of the current of

publication, may be remembered against me by a few of my personal

friends, I have replaced here by an entirely new version, made for

them and my conscience, in expiation of a sin of my youth, with the

sincerest application of my mature mind."

From the dedication of the same collection to her father, we learn

that when she was but a child she wrote verses, (Miss Mitford says

she wrote largely at ten years old,) and dedicated them to him; and

as she grew into mature years, verse-writing became "the great

pursuit of her life." Shortly after accomplishing her

translation from Æschylus, Miss Barrett wrote "An Essay on Mind,"

showing that she was pushing her inquiries in other directions

besides poetry. She also acquired a knowledge of the Hebrew

language, and even of the Chaldæan, and read through the Bible in

the original tongue, from Genesis to Malachi. Plato, in the

original Greek, was also one of her favourite books. But a

serious illness compelled her, in a measure, to give up these severe

pursuits; added to which, a terrible domestic calamity occurred to

her, which had the effect of throwing a dark shadow over her entire

future life. Here we quote from the "Recollections" of Miss

Mitford:—

"My first acquaintance with

Elizabeth Barrett commenced about fifteen years ago. She was

certainly one of the most interesting persons that I had ever seen.

Everybody who then saw her said the same; so that it is not merely

the impression of my partiality or my enthusiasm. Of a slight,

delicate figure, with a shower of dark curls falling on either side

of a most expressive face, large, tender eyes, richly fringed by

dark eyelashes, a smile like a sunbeam, and such a look of

youthfulness, that I had some difficulty in persuading a friend, in

whose carriage we went together to Chiswick, that the translatress

of the 'Prometheus' of Æschylus, the authoress of the 'Essay on

Mind,' was old enough to be introduced into company,—in technical

language, was out. Through the kindness of another invaluable

friend, to whom I owe many obligations, but none so great as this, I

saw much of her during my stay in town. We met so constantly

and so familiarly, that, in spite of the difference of age, intimacy

ripened into friendship; and after my return into the country, we

corresponded freely and frequently, her letters being just what

letters ought to be,—her own talk put upon paper.

"The next year was a painful one to herself and to all who

loved her. She broke a blood-vessel upon the lungs, which did

not heal. If there had been consumption in the family, that

disease would have intervened. There were no seeds of the

fatal English malady in her constitution, and she escaped.

Still, however, the vessel did not heal, and after attending her for

above a twelvemonth at her father's house in Wimpole Street, Dr.

Chalmers, on the approach of winter, ordered her to a milder

climate. Her eldest brother,—a brother in heart and in talent

worthy of such a sister,—together with other devoted relatives,

accompanied her to Torquay; and there occurred the fatal event which

saddened her bloom of youth, and gave a deeper hue of thought and

feeling—especially of devotional feeling—to her poetry. I have

so often been asked what could be the shadow that had passed over

that young heart, and now that time has softened the first agony, it

seems to me right that the world should hear the story of an

accident in which there was much sorrow, but no blame.

"Nearly a twelvemonth had passed, and the invalid, still

attended by her affectionate companions, had derived much benefit

from the mild sea-breezes of Devonshire. One fine summer

morning her favourite brother, together with two other fine young

men, his friends, embarked on board a small sailing-vessel, for a

trip of a few hours. Excellent sailors all, and familiar with

the coast, they sent back the boatmen, and undertook themselves the