|

". . . . as a poet, he stands by the side of Burns, of whom,

however, he was deemed not a rival, nor indeed and equal; but when

Nicoll died, he had written what Burns up to that time had not equalled.

Tracing his career through various vicissitudes, at last we find him

become editor of the Leeds Times . . . . on the small salary of

£100 per year, he made the fortune of that paper, as well as the

proprietors . . . . there is no question that his editorial articles

were remarkable for extraordinary talent, and there can be no doubt that

his writings at this period may be classed among the most brilliant

effusions of the provincial newspaper press. But, alas! his

unwearied labours broke down his talented and energetic mind. His

health became impaired, and sickness overtook him. He returned to

his native Scotland and died of consumption at the early age of 23.

His poetry is noble and brilliant; his poetical pictures of Scottish

scenery are very fine, and his sympathy was readily accorded to all . .

."

'Poets of the Humble Life': a lecture by the Rev.

T. Hinks, April, 1850.

“I have written my heart in my poems; and rude, unfinished, and

hasty as they are, it can be read there.”

ROBERT NICOLL.

――――♦――――

ROBERT NICOLL: A BRIEF

BIOGRAPHY

BY

SAMUEL SMILES.

|

|

|

IF you

have borne the bitter taunts

Which proud, poor men must bear:

If you have felt the upstart's sneer

Your heart like iron sear;

If you have heard yourself belied,

Nor answer'd word nor blow;

You have endured as I have done—

And poverty you know!

From....Endurance

|

THE name of

ROBERT NICOLL

(1814-37)

will always take high rank among the poets of Scotland.

He was one of the many illustrious Scotchmen who have risen up to adorn the lot of toil, and reflect

honour on the class from which they have sprung,—the laborious and hard-working peasantry of their land.

Nicoll, like Burns, was a man of whom those who live in poor men's huts may well be proud.

They declare, from day to day, that intellect is of no class, but that even in abodes of the deepest poverty there are warm hearts and noble minds, wanting but the opportunity and the circumstances to enable them to take their place as

honourable and zealous labourers in the work of human improvement and Christian progress.

The life of Robert Nicoll was not one of much variety of incident.

It was, alas! brought to an early close; for he died almost ere he had reached manhood.

But in his short allotted span, it is not too much to say, that he lived more than most men have done who reach their threescore years and ten.

He was born of hard-working, God-fearing parents, in the year 1814, at the little village of Tulliebelton, situated near the foot of the Grampian Hills, in Perthshire.

At an early period of his life, his father had rented the small farm of Ordie-braes; but having been unsuccessful in his farming, and falling behind with his rent, his home was broken up by the laird; the farm-stocking was sold off by public roup; and the poor man was reduced to the rank of a common day-labourer.

|

My wife is naked,--and she

begs

Her bread from door to door;

She sleeps on clay each night beside

Her hungry children four!

She drinks--I drink : for why? it drives

All poverty away;

And starving babies grow again

Like happy children gay!

From.....A

Bacchanalian

|

Robert was the second of a family of seven children, six sons and one daughter, the "sister Margaret" of whom the poet afterwards spoke and wrote so affectionately.

Out of the bare weekly income of a day-labourer, there was not, as might be inferred, much to spare for schooling.

But the mother was an intelligent, active woman, and assiduously devoted herself to the culture of her children.

She taught them to read, and gave them daily lessons in the Assembly's Catechism; so that before being sent to school, which they all were in due course, this good and prudent mother had laid the foundations in them of a sound moral and religious education.

"My mother," says Nicoll, in one of his letters, "in her early years, was an ardent book-woman.

When she became poor, her time was too precious to admit of its being spent in reading, and I generally read to her while she was working; for she took care that the children should not want education."

Robert's subsequent instruction at school included the common branches of reading, writing, and accounts; the remainder of his education was his own work.

He became a voracious reader, laying half the parish under contribution for books.

A circulating library was got up in the neighboring village of Auchtergaven, which the lad managed to connect himself with, and his mind became stored apace.

Robert, like the rest of the children, when he became big enough and old enough, was sent out to field-work, to contribute by the aid of his slender gains towards the common store.

At seven he was sent to the herding of cattle, an occupation, by the way, in which many distinguished

Scotchmen—Burns, James Ferguson, Mungo Park, Dr. Murray (the Orientalist), and James Hogg—spent their early

years. In winter, Nicoll attended the school with his "fee."

When occupied in herding, the boy had always a book for his companion; and he read going to his work and returning from it.

While engaged in this humble vocation he read most of the Waverley novels.

At a future period of his life, he says, "I can yet look back with no common feelings on the wood in which, while herding, I read Kenilworth."

Probably the perusal of that beautiful fiction never gave a purer pleasure, even in the stately halls of rank and fashion, than it gave to the poor herd-boy in the wood at Tulliebelton.

When twelve years of age, Robert was taken from the herding, and went to work in the garden of a neighbouring proprietor.

Shortly after, when about thirteen, he began to scribble his thoughts, and to string rhymes together.

About this time also, as one of his intimate friends has told us, he passed through a strange phasis of being.

He was in the practice of relating to his companions the most wonderful and incredible stories as

facts,—stories that matched the wonders of the Arabian Tales,—and evidencing the inordinate

ascendancy at that time of his imagination over the other faculties of his mind.

The tales and novel literature, which, in common with all other kinds of books, he devoured with avidity, probably tended to the development of this disease (for such it really seemed to be) in his young and excitable nature.

As for the verses which he then wrote, they were not at all such as satisfied himself; for, despairing of ever being able to write the English language correctly, he gathered all his papers together and made a bonfire of them, resolving to write no more "poetry" for the present.

He became, however, the local correspondent of a provincial newspaper circulating in the district, furnishing it with weekly paragraphs and scraps of news, on the state of the weather, crops, &c.

His return for this service was an occasional copy of the paper, and the consequence attendant on being the "correspondent" of the village.

But another person was afterwards found more to the liking of the editor of the paper, and Robert, to his chagrin, lost his profitless post.

|

This is the chapel where the matin hymn

Was chanted duly for a thousand years,

Till faith grew cold and doubtful, truth grew dim,

Till earnest hope was wither'd up by sneers.

Within it now no glorious thing appears:

But as the dewy wind blows swiftly by,

Upon the thoughtful listener's joyful ears

Doth come a sweet and holy symphony,

And nature's choristers are chanting masses high!

From....

A Woodland Walk

|

Nicoll's next change was an important one to him.

He left his native hamlet and went into the world of active life. At the age of seventeen he was bound apprentice to a grocer and wine-merchant in Perth.

There he came in contact with business, and activity, and opinion.

The time was stirring with agitation. The Reform movement had passed over the face of the country like a tornado, raising millions of minds to action.

The exciting effects of the agitation on the intellects and sympathies of the youth of that day are still remembered; and few there were who did not feel more or less influenced by them.

The excitable mind of Nicoll was one of the first to be influenced; he burned to distinguish himself as a warrior on the people's side; he had longings infinite after popular enlargement, enfranchisement, and happiness.

His thoughts shortly found vent in verse, and he became a poet. He joined a debating-society, and made speeches.

Every spare moment of his time was devoted to self-improvement,—to the study of grammar, to the reading of works on political economy, and to politics in all their forms. In the course of one summer, he several times read through with attention Smith's Wealth of Nations, not improbably with an eye to some future employment on the newspaper press.

He also read Milton, Locke, and Bentham, and devoured with avidity all other books that he could lay hands on.

The debating-society with which he was connected proposed to start a periodical, and Nicoll undertook to write a tale for the first number.

The periodical did not appear, and the tale was sent to Johnstone's Edinburgh Magazine, where it was published under the title of "Jessie Ogilvy," to the no small joy of the writer.

It decided Nicoll's vocation,—it determined him to be an author.

He proclaimed his Radicalism,—his resolution to "stand by his order," that of "the many." His letters to his relatives, about this time, are full of political allusions.

He was working very hard, too,— attending in his mistress's shop, from seven in the morning till nine at night, and afterwards sitting up to read and write; rising early in the morning, and going forth to the North Inch by five o'clock, to write or to read until the hour of shop-opening.

At the same time he was living on the poorest possible diet,—literally on bread and cheese, and

water,—that he might devote every possible farthing of his small gains to the purposes of mental improvement.

Few constitutions can stand such intense labour and privation with impunity; and there is little doubt but Nicoll was even then undermining his health, and sowing the seeds of the malady which in so short a time after was to bring him to his grave.

But he was eager to distinguish himself in the field of letters, though but a poor shop-lad; and, more than all, he was ambitious to be independent, and have the means of aiding his mother in her humble exertions for a living; never losing sight of the comfort and welfare of that first and fastest of his friends.

At length, however, his health became seriously impaired, so much so that his Perth apprenticeship was abruptly brought to a close, and he was sent home by his mistress to be nursed by his mother at Ordie

Braes,—not, however, before he had contributed another Radical story, entitled "The Zingaro," a poem on "Bessy Bell and Mary Gray," and an article on "The Life and Times of John Milton," to Johnstone's

Edinburgh Magazine.

An old friend and schoolfellow, who saw him in the course of this visit to his mother's house, thus speaks of him at the time: "Robert's city life had not spoiled him.

His acquaintance with men and books had improved his mind without chilling his heart.

At this time he was full of joy and hope. A bright literary life stretched before him.

His conversation was gay, and sparkling, and rushed forth like a stream that flows through flowery summer vales."

|

At feasting-time the powers aboon

At cramming try their utmost skill;

But faith the Bailie dings them a'

At spice and wine, or whisky gill.

The honest man can sit and drink,

And never ha'e his purse to draw;

He helps to rule this sinfu' town,

And as it should—it pays for a'.

From.....The

Bailie

|

His health soon became re-established, and he then paid a visit to Edinburgh, (Turing the period of the Grey

Festival,—and there met his kind friend Mrs. Johnstone, William Tait, Robert Chambers, Robert Gilfillan, and others known in the literary world, by all of whom he was treated with much kindness and hospitality.

His search for literary employment, however, which was the main cause of his visit to Edinburgh, was in vain, and he returned home disappointed, though not hopeless.

He was about twenty when he went to Dundee, there to start a small circulating library.

The project was not very successful; but while be kept it going, he worked harder than ever at literary improvement.

He now wrote his Lyrics and Poems, which, on their publication, were extremely well received by the press.

He also wrote for the liberal newspapers of the town, delivered lectures, made speeches, and extended his knowledge of men and society.

In a letter to a friend, written in February, 1836, he says: "No wonder I am busy.

I am at this moment writing poetry: I have almost half a volume of a novel written; I have to attend the meetings of the Kinloch Monument Committee; attend my shop; write some half-dozen articles a week for the

Advertiser; and, to crown all, I have fallen

in love." At last, however, finding the library to be a losing concern, he made it entirely over to the partner who had joined him, and quitted Dundee, with the intention of seeking out some literary employment by which he might live.

|

|

Robert

Nicoll Monument, facing Obney Hill at

Little Tulliebelton Farm.

Photo Alistair Bell. |

The Dundee speculation had involved Nicoll, and through him his mother, in debt, though to only a small amount.

This debt weighed heavy on his mind, and he thus opened his heart in a highly characteristic letter to his parent about it: "This money of R.'s (a friend who had lent him a few pounds to commence business with) hangs like a millstone about my neck.

If I had it paid, I would never borrow again from mortal man. But do not mistake me, mother; I am not one of those men who faint and falter in the great battle of life.

God has given me too strong a heart for that. I look upon earth as a place where every man is set to struggle, and to work, that he may be made humble and pure-hearted, and fit for that better land for which earth is a

preparation,—to which earth is the gate. Cowardly is that man who bows before the storm of

life,—who runs not the needful race manfully, and with a cheerful heart.

If men would but consider how little of real evil there is in all the ills of which they are so much

afraid,—poverty included,—there would be more virtue and happiness, and less world and mammon worship on earth than is.

I think, mother, that to me has been given talent; and if so, that talent was given to make it useful to man.

To man it cannot be made a source of happiness unless it be cultivated; and cultivated it cannot be unless, I think, little [here some words are obliterated]; and much and well of purifying and enlightening the soul.

This is my philosophy; and its motto is,—

|

Despair, thy name is written on

The roll of common men. |

Half the unhappiness of life springs from looking back to griefs which are past, and forward with fear to the future.

That is not my way. I am determined never to bend to the storm that is coming, and never to look back on it after it has passed.

Fear not for me, dear mother; for I feel myself daily growing firmer, and more hopeful in spirit.

The more I think and reflect,—and thinking, instead of reading, is now my

occupation,—I feel that, whether I be growing richer or not, I am growing a wiser man, which is far better.

Pain, poverty, and all the other wild beasts of life which so affright others, I am so bold as to think I could look in the face without shrinking, without losing respect for myself, faith in man's high destinies, and trust in God.

There is a point which it costs much mental toil and struggling to gain, but which, when once gained, a man can look down from, as a traveller from a lofty mountain, on storms raging below, while he is walking in sunshine.

That I have yet gained this point in life, I will not say, but I feel myself daily nearer it."

About the end of the year 1836, Nicoll succeeded, through the kind assistance of Mr. Tait, of Edinburgh, in obtaining an appointment as editor of an English newspaper, the

Leeds Times.

This was the kind of occupation for which he had longed; and he entered upon the arduous

labours of his office with great spirit. During his year and a half of editorship his mind seemed to be on fire; and on the occasion of a Parliamentary contest in the town in which the paper was published, he wrote in a style which to some seemed bordering on frenzy.

He neither gave nor took quarter. The man who went not so far as he did in political opinion was regarded by him as an enemy, and denounced accordingly.

He dealt about his blows with almost savage violence. This novel and daring style, however, attracted attention to the paper, and its circulation rapidly increased, sometimes at the rate of two or three hundred a week.

One can scarcely believe that the tender-hearted poet and the fierce political partisan were one and the same person, or that he who had so touchingly written

|

I dare not scorn the meanest thing

That on the earth Cloth crawl, |

should have held up his political opponents, in the words of another poet,

|

To grinning scorn a sacrifice,

And endless infamy. |

But such inconsistencies are, we believe, reconcilable in the mental histories of ardent and impetuous men.

Doubtless, had Nicoll lived, we should have found his sympathies becoming more enlarged, and embracing other classes besides those of only one form of political creed.

One of his friends once asked him why, like Elliot, he did not write political poetry.

His reply was, that "he could not: when writing politics, he could be as wild as he chose: he felt a vehement desire, a feeling amounting almost to a wish, for vengeance upon the oppressor: but when he turned to poetry, a softening influence came over him, and he could be bitter no longer." |

|

THE LEEDS TIMES . . . . |

|

. . . . some examples of the paper's

radical editorials during Nicoll's term as Editor:

-

27th August 1836: the need for parliamentary reform - in particular, of the House of Lords - and for universal suffrage are high on

Nicholl's agenda.

-

3rd December 1836:

an admirer of Bentham, Nicoll lectures his readers on the economic

consequences of the Corn Laws ("Give us this day our daily bread")

and on the evils of slavery in the American cotton states (without

neglecting mention of the prevailing conditions in the mills of Bradford).

-

31st December 1836:

Nicoll rails about the iniquities of the Corn Laws (no wonder he was much

admired by Ebenezer Elliott), the

cruelties of the Poor Law and its inhumane workhouse system (Nicoll

describes them as

'poor house prisons'). Irish Protestant ('Orange') landlords also receive

dishonourable mention.

|

|

Lines such as these helped to treble

the circulation of

The Leeds Times' during Nicoll's brief period as Editor (1836-37) .

. . .

"The

sabres of Manchester* were paid for out of the bread of

the People whom they slew."

"For what were Peers

created? For the public good." Mr. Hume knows very well that Peers were

created for no such thing. They created themselves for their own especial

benefit, and for these past three centuries they have hanged and headed

all who said them nay.

"....there are

some able and willing to tell the poor

how the Aristocracy rob them by Corn Laws. How wages profits,

employment and bread itself, are rendered scarce and small by a law which

shuts up this land within a wall of brass, and hinders us from buying

what? Food! We ask but to labour and to buy food; and we dare not.

This is our freedom."

"Slavery in America

is the existence of millions of degraded, miserable human beasts of

burden, who exist for nothing but toil, not for themselves but for others,

and this monstrous and horrible system is justified, because it is said

the slaves are too ignorant for freedom, and because they are black!"

* Ed.―the Peterloo Massacre. |

|

His literary labours while in Leeds were enormous.

He was not satisfied with writing from four to five columns weekly for the paper; but he was engaged at the same time in writing a long poem, a novel, and in furnishing leading articles for a new Sheffield newspaper.

In the midst of this tremendous labour, he found time to go down to Dundee to get married to the young woman with whom he had fallen in love.

The comfort of his home was thus increased, though his labours continued as before.

They soon told upon his health. The clear and ruddy complexion of the youth grew pallid; the erect, manly gait became stooping; the firm step faltered; the lustrous eye dimmed; and health gave place to debility: the worm of disease was already at his heart and gnawing away his vitals.

His cough, which had never entirely left him since his illness, brought on by

self-imposed privation and study while at Perth, again appeared in an aggravated form; his breath grew short and thick; his cheeks became shrunken; and the hectic flush which rarely deceives, soon made its appearance.

He appeared as if suddenly to grow old; his shoulders became contracted; he appeared to wither up, and the sap of life to shrink from his veins.

Need we detail the melancholy progress of a disease which is, in this country, the annual fate of thousands.

As Nicoll's illness increased, he expressed an anxious desire to see his mother, and she was informed of it accordingly.

She was very poor, and little able to afford an expensive journey to Yorkshire by coach; nevertheless she contrived to pay the visit to her son.

Afterwards, when a friend inquired how she had been able to incur the expense, as poor Robert was in no condition to assist her even to the extent of the coach fare, her simple but noble reply was, "Indeed,

Mr.——, I shore for the siller." The true woman, worthy mother of so worthy a son, earned as a reaper the means of honestly and independently fulfilling her boy's dying wish, and the ardent desire of her own loving heart.

So soon as she set eyes on him on her arrival at Leeds, she felt at once that his days were numbered.

It almost seemed as if, while the body of the poet decayed, his mind grew more active and excitable, and that, as the physical powers become more weakened, his sense of sympathy became more keen.

When he engaged in conversation upon a subject which he loved,—upon human progress, the amelioration of the lot of the poor, the emancipation of

mind,—he seemed as one inspired. Usually quiet and reserved, he would on such occasions work himself into a state of the greatest excitement.

His breast heaved, his whole frame was agitated, and while he spoke, his large lustrous eyes beamed with unwonted fire.

His wife feared such outbursts, which were followed by sleepless nights, and the aggravation of his complaint.

Throughout the whole progress of his disease, down to the time when he left Leeds, Nicoll did not fail to produce his usual weekly quota of literary

labour. They little know, who have not learnt from experience, what pains and anxieties, what sorrows and cares, he hid under the columns of a daily or weekly newspaper.

No galley-slave at the oar tugs harder for life than the man who writes in newspapers for the indispensable of daily bread.

The press is ever at his heels, crying, "Give, give!" and well or ill, gay or sad, the Editor must supply the usual complement of "leading article."

The last articles poor Nicoll wrote for the paper were prepared whilst he sat up in bed, propped about by pillows.

A friend entered just as he had finished them, and found him in a state of high excitement: the veins on his forehead were turgid and his eyes bloodshot; his whole frame quivered, and the perspiration streamed from him.

He had produced a pile of blotted and blurred manuscript, written in his usual energetic manner.

It was immediately after sent to press. These were the last leaders he wrote.

They were shortly after followed by a short address to the readers of the paper, in which he took a short but affectionate farewell of them, stating that he went "to try the effect of his native air, as a last chance for life."

Almost at the moment of his departure from Leeds, an incident occurred which must have been exceedingly affecting to Nicoll, as it was to those who witnessed it.

Ebenezer Elliott, the "Corn-Law Rhymer," who entertained an enthusiastic admiration for the young poet, had gone over from Sheffield to deliver a short course of lectures to the Leeds Literary Institution, and promised himself the pleasure of a kindly interview with Robert Nicoll.

On inquiring about him, after the delivery of his first lecture, he was distressed to learn the sad state to which he was reduced.

"No words," says Elliott, in a letter to the writer of this memoir, "can express the pain I felt when informed, on my return to my inn, that he was dying, and that if I would see him I must reach his dwelling before eight o'clock next morning, at which hour he would depart by railway for Edinburgh, in the hope that his native air might restore him.

I was five minutes too late to see him at his house, but I followed him to the station, where about a minute before the train started he was pointed out to me in one of the carriages, seated, I believe, between his wife and his mother.

I stood on the step of the carriage and told him my name. He

gasped,—they all three wept; but I heard not his voice."

The invalid reached Newhaven, near Leith, sick, exhausted, distressed, and dying.

He was received under the hospitable roof of Mrs. Johnstone, his early friend, who tended him as if he had been her own child.

Other friends gathered around him, and contributed to smooth his dying couch.

It was not the least of Nicoll's distresses, that towards his latter end he was tortured by the horrors of destitution; not so much for himself as for those who were dependent on him for their daily bread.

A generous gift of £50 was forwarded by Sir William Molesworth, but Nicoll did not live to enjoy the bounty; in a few days after, he breathed his last in the arms of his wife.

The remains of Robert Nicoll rest in a narrow spot in Newhaven Churchyard.

No stone marks his resting place; only a small green mound, that has been watered by the tears of the loved he has left behind him.

On that spot the eye of God dwells; and around the precincts of the poet's grave, the memories of friends still hover with a fond and melancholy regret.

Robert Nicoll was no ordinary man; Ebenezer Elliott has said of him, "Burns at his age had done nothing like him."

His poetry is the very soul of pathos, tenderness, and sublimity.

We might almost style him the Scottish Keats; though he was much more real and lifelike, and more definite in his aims and purposes, than Keats was.

There is a truthful earnestness in the poetry of Nicoll, which comes home to the universal heart. Especially does he give utterance to that deep poetry which lives in the heart, and murmurs in the lot of the poor man.

He knew and felt it all, and found for it a voice in his exquisite lyrics.

These have truth written on their very front;—as Nicoll said truly to a friend, "I have written my

heart in my poems; and rude, unfinished, and hasty as they are, it can be read there."

"We are lowly," "The Ha' Bible," "The Hero," "The Bursting of the Chain," "I dare not scorn," and numerous other pieces which might be named, are inferior to few things of their kind in the English language.

"The Ha' Bible" is perhaps not unworthy to take rank with "The Cotter's Saturday Night" of Robert Burns.

It is as follows:—

|

THE HA' BIBLE.

Chief of the Household Gods

Which hallow Scotland's lowly cottage homes!

While looking on thy signs,

That speak, though dumb, deep thought upon me comes,—

With glad yet solemn dreams my heart is stirred,

Like Childhood's when it hears the carol of a bird!

The Mountains old and hear,—

The chainless Winds,—the Streams so pure and free,—

The God-enamelled Flowers,—

The waving Forest,—the eternal Sea,—

The Eagle floating o'er the mountain's brow,—

Are Teachers all; but oh! they are not such as thou!

O, I could worship thee!

Thou art a gift a God of love might give;

For Love and Hope and Joy

In thy Almighty-written pages live!—

The Slave who reads shall never crouch again;

For, mind-inspired by thee, he bursts his feeble chain!

God! Unto Thee I kneel,

And thank Thee! Thou unto my native land—

Yea, to the outspread Earth—

Hast stretched in love Thy Everlasting hand,

And Thou hast given Earth and Sea and Air,—

Yea, all that heart can ask of Good and Pure and Fair!

And, Father, Thou hast spread

Before men's eyes this Charter of the Free,

That all Thy Book might read,

And Justice love, and Truth and Liberty.

The Gift was unto Men,—the Giver God!

Thou Slave! it stamps thee Man,—go spurn thy weary load

Thou doubly-precious Book!

Unto thy light what doth not Scotland owe?—

Thou teachest Age to die,

And Youth in Truth unsullied up to grow!

In lowly homes a Comforter art thou,—

A sunbeam sent from God,—an Everlasting bow!

O'er thy broad ample page

How many dim and aged eyes have pored?

How many hearts o'er thee

In silence deep and holy have adored?

How many Mothers, by their Infants' bed,

Thy Holy, Blessed, Pure, Child-loving words have read!

And o'er thee soft young hands

Have oft in truthful plighted Love been joined,

And thou to wedded hearts

Hast been a bond,—an altar of the mind!—

Above all kingly power or kingly law

May Scotland reverence aye the Bible of the Ha'! |

__________________

Ed.: Robert Nicholl was born in Little Tullibelton in

the parish of Auchtergaven, Perthshire, in 1814, and died at Leith, where

he was buried, in 1837. A prominent obelisk commemorates him in his

home town.

|

|

MANCHESTER TIMES

OCTOBER

31, 1835.

PROGRESS OF EDUCATION.

_______________

THE PROPOSED ATHENÆUM.

Yes, Robert Nicoll, the Imaginative, the Hopeful, and the

Benevolent,

"The world shall be better yet,"

There are "stout hearts" to Face the "steep brae" of Oppression; and

the Weapon that the battle is to be fought with is Education—not the

heddekashun justly ridiculed by Cobbett, and by your country's

patriot bard, which converts men from "stirks" into asses, but right

leading-out which teaches the relative and social and

political duties, awakens the intellect, and induces habits at Sound

Thinking. Yes, Robert Nicoll: "We'll mak the warld

better yet;" for we are going the right way about it.

Many thanks to the Sunday school teacher! Little did he

think when he generously sacrificed his ease on the blessed day of

rest, of the important consequences of his confinement to the dull

form and the irksome occupations of teaching the A. B. C. It

was reward enough to him to think that he was enabling the child to

read the word of God; but he knew that he was advancing, by a

century, the Civilization, the Refinements, the Intellectual Vigour,

and the Freedom, of his fellow men.

See what Sunday schools have done! It was soon found

that it was desirable to have instructors during the period between

boyhood and manhood—for if it was well that the boy should

READ, and it was well that the man should

THINK—and hence arose Mechanics' Institutions.

It was thought also that it being confessedly well to teach the

youth, it would be still better to teach the child, in order that

early impressions, which are always the most forcible and the most

lasting, should be for good and not for evil—and hence arose Schools

for Infants. And then out of these schools others originated still

more important and beneficial. It was a matter of experience that to

take a child of seven years of age from one of these institutions

and place it in an ordinary school was to cause it to retrograde in

education. The necessity was created for intellectual schools to

follow up the explanatory and awakening system by which the child

had profited―and hence in this town, arose the admirable seminaries

in connection with the Mechanics' Institution and the Scottish Kirk,

founded on the principles of the Edinburgh Sessional School, in which

the master is a lecturer in every branch of physical and moral

sciences, and every pupil is an active teacher. That these school

will in their turn create new demands for intellectual culture, we

have not the slightest doubt; nor can we doubt that they will, by

their manifest superiority in all the really useful branches of

education to the Grammar Schools, compel a reformation in all the

endowed educational institutions throughout the country, the

Universities themselves, with their learning, falsely so called, not

excepted. How delightful it is thus to mark the process of light,

and to anticipate its further, and, ultimately its general

diffusion; and how doubly delightful to those who have assisted in

the glorious work! For ourselves, we would not exchanged the

consciousness of having given an impulse to the great moral

movement, for all of honour and of greatness that this world could

bestow; and when we think that, in some degree through our

instrumentality, thousands or infants and youths have secured the

blessings of right early, moral, religious and intellectual

training, we humbly thank our God that he has permitted us to do

some good in our day and generation.

And see what Mechanics' Institution have done! The Middle classes

begin to feel that their inferiors in station are likely to outstrip

them on the path to knowledge. And the comforting and hope-inspiring

reflection is that there is nobody now that dares to hold them

back—nobody to say "knowledge is for the rich alone"—but that, on

the contrary, while the aim is to keep before, the helping hand his

willingly held out to all who travel on the same road. This week has

witnessed persons of every religions denomination, and every grade

of political opinion, the capitalist of almost unbounded wealth, and

his youthful clerk whose aspirings are checked by the slenderness of

his means, all uniting heart and hand, to establish an institution

which shall be to the middle classes what Mechanics' Institutions

are to the working classes., with the addition of the means of

giving political knowledge, without which the merchant is a mere

pedlar in dirty wares. The design is a noble one. Let its

promoters persevere in the spirit with which they have begun, and

they will secure a noble reward―the

pleasure, if they are successful, of having elevated the moral and

intellectual character of the town―the satisfaction, if they fail,

of having done their duty.

Yes, Robert Nicoll! "We'll mak' the warld better yet!"

And the merchant will not be one whit less industrious and

enterprising when he shall read Bentham, and relish your description

of the humble cottages where Worth resides with undegrading Poverty

and from whence the peasant boy goes forth one day to "herd the kye,"

and the other to refresh his expatriated countrymen with the sounds

of living song.

|

|

|

|

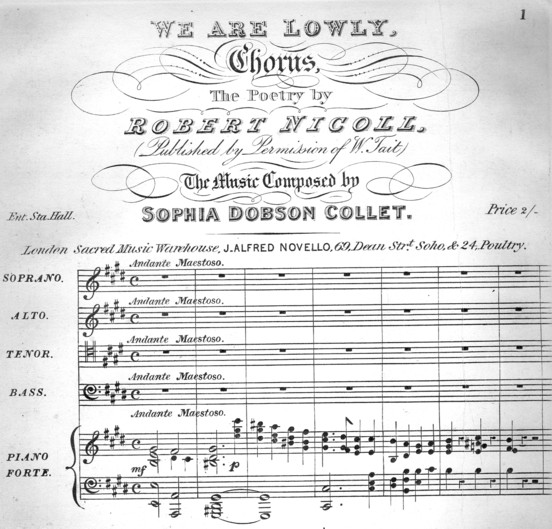

"WE ARE LOWLY"

A poem by Robert Nicoll,

set in four parts with piano accompaniment

by Sophia Collet. |

<>

|