|

[Previous Page]

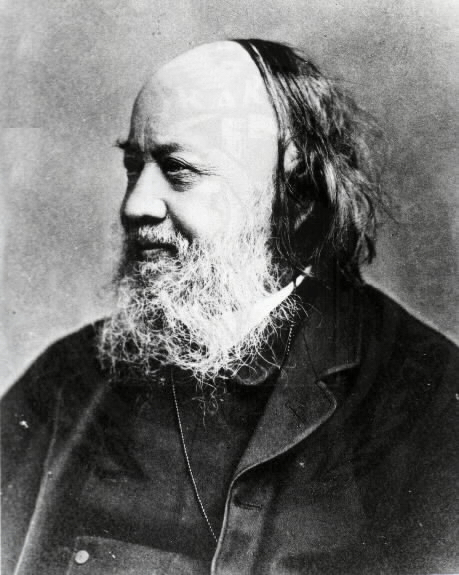

THEODORE HOOK.

Theodore Hook (1788-1841), author.

Picture Internet Text Archive.

THE unhappy

career of Edgar A. Poe is not without its counterpart in English

literary biography. Johnson, in his painful memoir of Savage,

has told a similar story of genius and misfortune, or rather genius

and misconduct; for it is a mistake to suppose that the possession

of genius in any way conduces to misfortune, except through the

misconduct of its possessor. Poetry and a garret used at one

time to be identified; but life in a garret may be as noble as life

in a palace, and a great deal purer. As Sir Walter Raleigh

once wrote in the little dungeon in the Tower, still pointed out as

the place of his confinement,—

"My mind to me a kingdom is!"

It is the mind that makes the man, and not the place—call it a

hovel, a garret, or a palace —in which the body lives. Even Johnson

has summed up the ills of the scholar's life in these words: "Toil,

envy, want, the patron, and the jail." But Johnson, doubtless,

bitterly remembered the day when he signed himself Impransus,

or Dinnerless, and received the anonymous alms of a pair of

shoes. Johnson must have been in one of his ungenial moods when he

penned those bitter words.

The fate of Chatterton, also, was a hapless one. Proud, impulsive,

ardent, and full of genius, like Poe, his career was short, unhappy,

and mournfully concluded. That of Otway, the author of "Venice

Preserved," who perished for want of bread, also springs to mind. Nor are other equally mournful examples a-wanting, which it would be

painful to relate. These instances are apt to be dwelt upon too

much, and cited from time to time as illustrations of the unhappy

lot of genius; whereas they are merely exceptional cases, not at all

characteristic of literary men in general.

Poets and authors are often charged with being improvident, as a

rule. But are there no improvident lawyers, divines, merchants, and

shopkeepers? The case of Theophilus Cibber is sometimes cited, who

begged a guinea and spent it on a dish of ortolans; and perhaps of

poor Goldsmith, who, when preserved from a jail by the money

received for "The Vicar of Wakefield," forthwith celebrated the

circumstance by a jollification with his landlady. But authors have

their weaknesses and their frailties, like other men; and some of

them are drunken, and some improvident, as other men are. As a

class, however, they are neither generally improvident nor out at

elbows. But we are usually disposed to think much more of the "calamities of authors" than we do of the calamities of other men. A

hundred bankers might break, and ten thousand merchants ruin

themselves by their improvidence, but none would think it worth

their while to record such events in books; nor, except as a mere

matter of news for living men, would any one care to read of such

occurrences. But how different in the case of a poet! Biographers

eagerly seize the minutest matter of detail in the history of a man

of genius. Johnson tells us the story of Savage, Southey relates the

career of Chatterton, Cunningham recounts the life of Burns, and

every tittle of their history is carefully gathered up and published

for the information of contemporary and future readers.

The late Thomas Hood, in one of his prose works, little known, well

observed that—

"Literary men, as a body, will bear comparison in point of conduct

with any other class. It must not be forgotten that they are

subjected to an ordeal quite peculiar, and scarcely milder than the

Inquisition. The lives of literary men are proverbially barren of

incident, and consequently the most trivial particulars, the most

private affairs, are unceremoniously worked up, to furnish matter

for their bald biographies. Accordingly, as soon as an author is

defunct, his character is submitted to a sort of Egyptian post

mortem trial; or rather, a moral inquest, with Paul Pry for the

coroner, and a judge of assize, a commissioner of bankrupts, a Jew

broker, a Methodist parson, a dramatic licenser, a dancing-master, a

master of the ceremonies, a rat-catcher, a bone-collector, a parish

clerk, a schoolmaster, and a reviewer, for a jury. It is the

province of these personages to rummage, ransack, scrape together,

rake up, ferret out, sniff, detect, analyze, and appraise, all

particulars of the birth, parentage, and education, life, character,

and behaviour, breeding, accomplishments, opinions, and literary

performances of the departed. Secret drawers are searched, private

and confidential letters published, manuscripts intended for the

fire are set up in type, tavern-bills and washing-bills are compared

with their receipts, copies of writs re-copied, inventories taken of

effects, wardrobe ticked off by the tailor's accounts, bygone toys

of youth—billets-doux, snuff-boxes, canes—exhibited,—discarded

hobby-horses are trotted out,—perhaps even a dissecting surgeon is

called in to draw up a minute report of the state of the corpse and

its viscera; in short, nothing is spared that can make an item for

the clerk to insert in his memoir. Outrageous as it may seem, this

is scarcely an exaggeration. For example, who will dare to say that

we do not know at this very hour more of Goldsmith's affairs than he

ever did himself? It is rather wonderful than otherwise, that the

literary character should shine out as it does after such a severe

scrutiny."

It is not enough, however, that literary men will bear comparison in

point of conduct with any other class. We think the public are

entitled to expect more than this; and to apply to them the words,

"Of those to whom much is given, much shall be required." They are

men of the highest culture, and ought to be men of the highest

character. As influencing the minds and morals of all readers,—and

the world is daily looking more and more to the books which men of

genius write, for instruction,—they ought to cultivate in themselves

a high standard of character,—the very highest standard of

character,—in order that those who study and contemplate them in

their books may be lifted and lighted up by their example. At all

events, we think the public are not over-exacting when they require

that the great gifts with which the leading minds among men have

been endowed shall not be prostituted for unworthy purposes, nor

employed for merely selfish and venial ends. Genius is a great gift,

and ought to be used wisely and uprightly for the elevation of the

moral character and the advancement of the intelligence of the world

at large. If not so employed, genius and talent may be a curse to

their possessor, and not a blessing to others,—they may even be a

fountain of bitterness and woe, spreading moral poison throughout

society.

We do not say that Theodore Hook was an author of this latter class;

but we do think that a perusal of his life, as written by one of his

own friends and admirers, [p.349]

cannot fail to leave on the reader's mind the impression, that here

was a man gifted with the finest powers, in whom genius proved a

traitor to itself, and false to its high mission. With shining

abilities, a fine intellect, sparkling wit, and great capacity for

work, Hook seemed to have no higher ambition in life than to sit as

an ornament at the tables of the great,—to buzz about their candles,

and consume himself for their merriment and diversion. In the houses

of titled men, who kept fine company and gave great dinners, he did

but play the part of the licensed wit and jester,—wearing the livery

of his as entertainers, not on his person, indeed, but in his soul;

bartering the birthright of his superior intellect for a mess of

pottage,—as Douglas Jerrold has said, "a mess of pottage served up

at a lord's table in a lord's platter."

Theodore Hook was the son of a musical composer of some note in his

day, [p.350] and born in Bedford Square, London, in 1788. He had an only

brother, James, who afterwards became Dean of Worcester, and whose

son, Dr. Hook, Dean of Chichester, survives to do honour to the

talents and reputation of the family. Theodore was, in early life,

petted by his father, who regarded him as a prodigy. He was sent to

school at Harrow, where he was the school-fellow of Byron and Peel,

though not in the same form. But on the death of his mother, Mr.

Hook took the boy from school, partly because he found his society

an amusing solace, and also because he had discovered that he could

turn the youth's precocious talents to profitable account. Already,

at the age of fourteen, Theodore could play expertly on the piano,

and sing pathetic as well as comic songs with remarkable expression.

One evening he enchanted the father especially by singing, to his

own accompaniment, two new ballads, one grave and one gay. Whence

the airs,—whence the words? It turned out that the verses and the

music were both Theodore's own! Here was a mine for the veteran

artist to work! Hitherto he had been forced to borrow his words: now

the whole manufacture might be done at home. So young Hook was taken

into partnership with his father, at the age of sixteen; and

straightway became a precocious man, admired of musicians and

players, the friends and boon companions of his father. Several of

his songs "took" on the stage, and he became the pet of the

green-room. Night after night he hung about the theatres, with the

privilege of admission before the curtain and behind it. Popular

actors laughed at his jokes, and pretty actresses would have their

bouquets banded to them by nobody but Theodore.

An effort was made by his brother—then advancing in the Church—to

have the youth removed from this atmosphere of dissipation and

frivolity; and, at his urgent remonstrance, Theodore was entered a

student at Oxford. But he carried his spirit of rebellious frolic

with him. When the Vice-Chancellor, noticing his boyish appearance,

said, "You seem very young, sir; are you prepared to sign the

Thirty-nine Articles?" "O yes, sir," briskly answered

Theodore,—"quite ready,—forty, if you please!" The dignitary

shut the book; the brother apologized, the boy looked contrite, the

articles were duly signed, and the young scapegrace matriculated at

Alma Mater. He was not yet to reside at Oxford, however, but

returned to London to go through a prescribed course of reading. Under his father's eye, however, no serious study could go forward;

besides, the youth's head was full of farce. At sixteen, he began to

write Vaudevilles for the stage, the music adapted to which was

supplied by his father. These trifles succeeded, and the clever boy

became a greater green-room pet than ever. He thus made the

acquaintance of Mathews and Liston, for whom he wrote farces. Hook

was not over particular about the sources from whence he cribbed his

"points;" borrowing unscrupulously from all quarters. In the course

of four years, he wrote more than ten plays, which had a

considerable run at the time, though they are now all but forgotten. Two of them have, nevertheless, been recently revived, namely,

"Exchange no Robbery," and "Killing no Murder." Had he gone on

writing plays, he would certainly have established a reputation as a

first-rate farce-writer. But, in his volatile humour, he must needs

try novels; and forthwith, at twenty years old, he wrote

"Musgrave,"—a novel of ridiculous sentimentality, but sparkling and

clever: yet it was a failure. About the same time, his life was a

succession of boisterous buffooneries, of which his "Gilbert Gurney"

may be regarded as a pretty faithful record. Unquestionably, Hook

wrote that novel chiefly from personal recollections; it is

virtually his autobiography; and in his diary, when speaking of its

progress, he uses the words, "working at my life."

Hook often used to tell the story—which he gives in detail in

"Gilbert Gurney"—of Mathews and himself, when one day rowing to

Richmond, being suddenly smitten by the sight of a placard at the

foot of a Barnes garden,—"Nobody permitted to land here—Offenders

prosecuted with the utmost rigour of the Law." The pair instantly

disembarked on the forbidden paradise; the fishing-line was

converted into a surveyor's measuring-tape; the wags paced to and

fro on the beautiful lawn,—Hook, the surveyor, with his book and

pencil in hand,—Mathews, the clerk, with the cord and walking-stick,

both soon pinned into the exquisite turf. Then suddenly opened the

parlour-window of the mansion above, and forth stepped, in

blustering ire, a napkined alderman, who advanced with what haste he

could against the intruders on his paradise. The comedians stood

cool, and scarcely condescended to reply to his indignant inquiries. At length oozed out the gradual announcement of their being the

agents of a New Canal Company, settling where the new cut was to

cross the old gentleman's pleasure-ground. Their regret was extreme

at having "to perform so disagreeable a duty," but public interests

must be regarded. Then came the alderman's suggestion that the pair

had better "walk in and talk the matter over;" their reluctant

acquiescence,—"had only a quarter of an hour to spare,—feared that

it was of no use" their endeavouring to avoid the beautiful

spot,—the new cut must come through the grounds. However, in they

went; the turkey was just served, an excellent dinner followed,

washed down with madeira, champagne, claret, and so on. At length

the good fare produced its effect,—the projected branch of the canal

was reconsidered,—the city knight's arguments were acknowledged to

be of more and more weight. "Really," says the alderman, "this cut

must be given up; but one bottle more, dear gentlemen." At last when

it was getting dark—they were eight miles from Westminster

Bridge—Hook burst out into song, and narrated in extempore verse the

whole transaction, winding up with —

|

"And we greatly approve of your fare,

Your cellar's as prime as your cook,

And this clerk here is Mathews the player,

And my name, sir, is—Theodore Hook! |

The adventure forms the subject of a capital chapter in "Gilbert

Gurney," which many of our readers may have read.

But the maddest of Hook's tricks was that known as the "Berners

Street Hoax," which happened in 1809, as follows. Walking down

Berners Street, one day, Hook's companion (probably Mathews) called

his attention to a particularly neat and modest house, the

residence—as was inferred from the door-plate—of some decent

shopkeeper's widow. "I'll lay you a guinea," said Theodore, "that in

one week that nice quiet dwelling shall be the most famous in all

London." The bet was taken, and in the course of four or five days,

Hook had written and posted one thousand letters, annexing

orders to tradesmen of every sort within the bills of mortality, all

to be executed on one particular day, and as nearly as possible at

one fixed hour. From "wagons of coals and potatoes, to books,

prints, feathers, ices, jellies, and cranberry tarts," nothing in

any way whatever available to any human being but was commanded from

scores of rival dealers, scattered all over the city, from Wapping

to Lambeth, from Whitechapel to Paddington. It can only be feebly

imagined what the crash and jam and tumult of that day was. Hook had

provided himself with a lodging nearly opposite the fated house,

where, with a couple of trusty allies, he watched the progress of the

melodrama. The mayor and his chaplain arrived,—invited there to take

the death-bed confession of a peculating common-councilman. There

also came the Governor of the Bank, the Chairman of the East India

Company, the Lord Chief Justice, and the Prime Minister,—above all,

there came his Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury, and His Royal

Highness the Commander-in-Chief. These all obeyed the summons, for

every pious and patriotic feeling had been most movingly appealed

to. They could not all reach Berners Street, however,—the avenues

leading to it being jammed up with drays, carts, and carriages, all

pressing on to the solitary widow's house; but certainly the Duke of

York's military punctuality and crimson liveries brought him to the

point of attack before the poor woman's astonishment had risen to

terror and despair. Most fierce were the growlings of doctors and

surgeons, scores of whom had been cheated of valuable hours. Attorneys, teachers of every kind, male and female, hair-dressers,

tailors, popular preachers, Parliamentary philanthropists, had been

alike victimized. There was an awful smashing of glass, china,

harpsichords, and coach-panels. Many a horse fell, never to rise

again. Beer-barrels and wine-barrels were overturned and exhausted

with impunity amidst the press of countless multitudes. It was a

great day for the pickpockets; and a great godsend to the

newspapers. Then arose many a fervent hue and cry for the detection

of the wholesale deceiver and destroyer. Though in Hook's own

theatrical world he was instantly suspected, no sign escaped either

him or his confidants. He found it convenient to be laid up a week

or two by a severe fit of illness, and then promoted reconvalescence

by a few weeks' country tour. He revisited Oxford, and professed an

intention of commencing his residence there. But the storm blew

over, and Hook returned with tranquillity to the green-room. This

was followed by other tricks and hoaxes, in one of which he made

Romeo Coates his victim. These may be found detailed at some length

in "Gilbert Gurney," and in Mrs. Mathews's Memoirs of her husband,

who was usually Hook's accomplice in such kinds of mischief.

One of Hook's extraordinary talents—which amounted in him to almost

a genius—was his gift of singing improvised songs on the spur of the

moment, while under the influence of excited convivial feelings. He

would sit down to the piano-forte, and, quite unhesitatingly,

compose a verse upon every person in the room, full of the most

pointed wit, and with the truest rhyme, gathering up, as he

proceeded, every incident of the evening, and working up the whole

into a brilliant song. He would often, like John Parry, sport with

operatic measures, in which he would triumph over every variety of

metre and complication of stanza. But John Parry's exhibitions are

carefully studied, whereas Hook's happiest effects were spontaneous

and unpremeditated. The effect he produced on such occasions was

almost marvellous. Sheridan frequently witnessed these exhibitions,

and declared that he could not have believed such power possible,

had he not witnessed it. Of course, Hook was usually stimulated by

wine or punch when he ventured on such exploits; and it is recorded,

that during one of his songs, at which Coleridge was present, every

pane in the room window was riddled by the glasses flung through

them by the guests, the host crowning the bacchanalian riot by

demolishing the chandelier with his goblet.

Hook's fame as a wit, a jester, a talker, and an improvisatory

singer, shortly reached aristocratic circles; and he was invited to

their houses to make sport for them. Sheridan mentioned him to the

Marchioness of Hertford as a most amusing fellow, and he was shortly

after called upon to display his musical and metrical facility in

her Ladyship's presence; which he did. He was called, in like

manner, to minister to the amusement of the Sybarite Prince Regent

at a supper in Manchester Square, and he so delighted his Royal

Highness, that, on leaving the room, he said, "Mr. Hook, I must see

you and hear you again." Hook was only too glad to play merry-andrew

to the Prince; and after a few similar evenings, his Royal Highness

was so good as to make inquiry about Hook's position, when, finding

he was without a profession or fixed income of any sort, he

signified his opinion that "something must be done for Hook." As the

word of the Prince was equivalent to a law, and quiet jobs were

easily done in those days, Hook's promotion followed as a matter of

course. He was almost immediately after appointed Accountant-General

and Treasurer to the Colony of the Mauritius, with an income of

£2,000 a year. Hook had no knowledge of accounts; but he had the

Prince Regent's good word, and that was enough. He stayed five years

in the Mauritius, paying no attention to the duties of his office,

living in great style, a leading man on the turf, the very prince of

Mauritian hospitality. But it came to a sad end. In March, 1818,

Hook was arrested, while supping at a friend's house, and dragged,

by torchlight, through crowded streets, to the common prison of the

town, on a charge of embezzling the public moneys in the colonial

treasury to a large amount! From thence he was conveyed to England,

tried before the law officers of the crown, and brought in as

defaulter to the extent of £12,000. This debt he never paid; though

his earnings by his pen, for many years after, were very large. Into

the merits of the case against Hook we shall not here enter; but as

the government which brought him to book was friendly to him, and

under the influences of many of his personal friends, we must

presume the charges to have been well founded. The most favourable

view of his case that can be taken is this: that somebody embezzled

the colonial moneys; but as Hook had no knowledge of accounts, and

rarely took any concern in the treasury business, spending his

£2,000 a year in the manner of a gentlemanly sinecurist, the

colonial funds were "mumbled away," and Hook, being the responsible

party, was saddled with the blame.

On reaching London again, to wait the issue of the government

investigation, he was set at liberty, on the Attorney-General's

report, that there was no apparent ground for a criminal procedure;

and the case was treated as one of defalcation and civil prosecution

only. In order to live in the meanwhile, Hook had recourse to his

ever-ready pen. First, he wrote for magazines and newspapers; then

he tried a shilling magazine, called "The Arcadian," of which only

a few numbers were issued, when the publisher lost heart. In 1820,

Sir Walter Scott accidentally met Hook at a dinner-party at Daniel

Terry's, and was delighted, as everybody could not help being, with

Hook's brilliant conversation. Hook, notwithstanding the affair of

his colonial defalcations, and the prosecution of him by the Audit

Board, still held his "good old Tory" views of politics; and

gratefully remembered his personal obligations to the Prince Regent,

now the reigning monarch. He was consequently violently opposed to

the pretensions and partisans of Queen Caroline. The strong colour

of his politics induced Scott to mention Hook to a gentleman who

shortly after applied to him to recommend an editor for a newspaper

about to be established. To this circumstance his connection with

the famous "John Bull" is probably to be attributed. At all events,

the John Bull shortly after came out, with Hook for its editor. But

he preserved his incognito carefully for many years, which was the

more necessary in consequence of the thick cloud which still hung

over his moral character in connection with his colonial affair. Hook threw himself with great fury into the ranks of the Georgites,

and published many violent squibs against Queen Caroline and her

friends, which excited a storm of popular indignation. The John Bull

was generally admitted to be the most powerful, unscrupulous, and

violent advocate of the king's cause; whether it was the better for

the advocacy, we shall not here venture to determine. The paper was

well supported with money,—as was surmised, from "head-quarters;"

and for some years Hook's income, from the John Bull alone, amounted

to as much as £2,000 a year. At length it began to ooze out that

Hook was the editor of the John Bull. Though furnishing nearly the

whole of the articles and squibs which appeared in it, he at once

indignantly denied the imputation, in a "letter to the editor," in

which he disclaimed and disavowed all connection with the paper. But, by slow degrees, the truth came out, and at last all was known. The

John Bull was denounced by many as a "reckless," "venomous,"

"malignant," slandering," "lying" publication; and by others it was

defended as a "spirited," "courageous," "loyal," and "admirable"

defender of the church, crown, and constitution.

In 1823 Hook was arrested for the sum of £12,000, which the

authorities had finally decided that he stood indebted to the public

exchequer. He was then confined in a sheriff's officer's house in

Shire Lane,—a miserable, squalid neighbourhood. He remained there

for several months, during which his health seriously suffered. While shut up in Shire Lane he made the acquaintance of Dr. William Maginn, who had recently come over from Ireland, a literary

adventurer, but had fallen into the sheriff's officer's custody. It

was a lucky meeting for both, however, as Magnin proved of great

assistance to Hook, in furnishing the requisite amount of "spicy"

copy for the columns of the John Bull. Hook was transferred to the

Rules of the King's Bench, where he remained for a year, and

afterwards succeeded in getting liberated; but was told distinctly

that the debt must hang over him until every farthing was paid. He

then took a cottage at Putney, and re-entered society again. He had

for companion here a young woman whom he ought to have married; that

he did not—that he left upon the heads of his innocent offspring by

her, a stigma and a stain in the eyes of the world—was only, we

regret to say, too much in keeping with the character and career of

the reckless, unscrupulous, and feeble-conscienced Theodore Hook.

While living in his apartments at Temple Place, within the Rules of

the King's Bench, Hook had begun his career as a novelist. His first

series of "Sayings and Doings" was very successful, and yielded him

a profit of £2,000. The second and third series were equally

successful. His other novels, entitled "Maxwell," "The Parson's

Daughter," "Love and Pride," were also successful novels, and paid

him well. In 1836 he became the editor of the New Monthly Magazine,

in which he published "Gilbert Gurney," (perhaps the raciest of all

his novels, being chiefly drawn from his own personal experiences,)

and afterwards "Gurney Married," "Jack Brag," "Births, Deaths, and

Marriages," "Precepts and Practice," and "Fathers and Sons." These

were all collected and republished afterwards in separate forms. The

number of these works,—thirty-eight volumes,—which he wrote within

sixteen years, at the time when he was editor and almost sole writer

for a newspaper, and for several years the conductor of a magazine,

argue a by no means idle disposition. Indeed, Hook worked very hard;

the pity is that he worked to so little purpose, and that he

squandered the money with which he ought to have paid his debts (and

he himself admitted that he was in justice responsible for £9,000)

in vying with fashionable people to keep up appearances, and live a

worthless life of dissipation, frivolity, and burlesque "bon ton." For many years Hook must have been earning from £4,000 to £5,000 a

year by his pen, and yet he was always poor! How did he spend his

earnings? Let the friend who has written the sketch of him in the

Quarterly Review explain the secret.

"In 1827 (after leaving his house at Putney) he took a higher

flight. He became the tenant of a house in Cleveland Row,—on the

edge, therefore, of what, in one of his novels, he describes as the

'real London,—the space between Pall Mall on the south, and

Piccadilly on the north, St. James's Street on the west, and the

Opera House to the cast.' The residence was handsome, and, to

persons ignorant of his domestic arrangements, appeared

extravagantly too large for his purpose; we have since heard of it

as inhabited by a nobleman of distinction. He was admitted a member

of diverse clubs; shone the first attraction of their House dinners;

and, in such as allowed of play, he might commonly be seen in the

course of his protracted evening. Presently he began to receive

invitations to great houses in the country, and, for week after

week, often travelled from one to another such scene, to all outward

appearance in the style of an idler of high condition. In a word, he

had soon entangled himself with habits and connections which implied

much curtailment of the time for labour at the desk, and a course of

expenditure more than sufficient to swallow all the profits of what

remained. To the upper world he was visible solely as the jocund

convivialist of the club,—the brilliant wit of the lordly

banquet,—the lion of the crowded assembly,—the star of a Christmas

or Easter party in a rural palace,—the unfailing stage-manager,

prompter, author, and occasionally excellent comic actor, of the

private theatricals, at which noble guardsmen were the valets, and

lovely peeresses the soubrettes."

Thus did the brilliant Hook flutter like a dazzled moth around the

burning taper of aristocracy, scorching his wings, and at length

sinking destroyed by the seductive blaze, when he was at once swept

away as some unsightly object.

It was a feverish, miserable, unhealthy life,

with scarcely a redeeming feature in it. To make up for the

time devoted by him to the amusement of aristocratic circles, and to

raise the money wherewithal to carry on this brilliant dissipation,

as well as to relieve himself of the pressure of his more urgent

pecuniary embarrassments, Hook worked day and night when at his own

house, often under the influence of stimulants, and thus increased

the nervous agonies of a frame prematurely wasted and exhausted.

Meanwhile he was pressed by his publisher, into whose debt he had

fallen; and publishers, in such a case, are exacting, like everybody

else in similar circumstances. Debts—debts—forever

debts—accumulated about Hook, each debt a grinning phantom, mocking

at him even in the midst of his gayest pleasures. "Little did

his fine friends know at what tear and wear of life he was devoting

his evenings to their amusement. The ministrants of pleasure

with whom they measured him were almost all as idle as

themselves,—elegant, accomplished men, easy in circumstances, with

leisure at command, who drove to the rendezvous after a morning

divided between voluptuous lounging in a library chair and healthful

exercise out of doors. But he came forth, at best, from a long day of labour at his writing-desk,

after his faculties had been kept on the stretch,—feeling, passion,

thought, fancy, excitable nerves, suicidal brain, all worked,

perhaps well-nigh exhausted,—compelled, since he came at all, to

disappoint by silence, or to seek the support of tempting stimulants

in his new career of exertion. And we may guess what must have been

the effect on his mind of the consciousness, while seated among the

revellers of a princely saloon, that next morning must be, not given

to the mere toil of the pen, but divided between scenes in the

back-shops of three or four eager, irritated booksellers, and weary prowlings through the dens of city usurers for the means of

discounting this long bill, staving off that attorney's threat; not

less commonly—even more urgently—of liquidating a debt of honour to

the grandee, or some of the smiling satellites of his pomp.

"There is recorded (in his diary) in more than usual detail, one

winter visit at the seat of a nobleman of almost unequalled wealth

(Marquis of Hertford?), evidently particularly fond of Hook, and

always mentioned in terms of real gratitude,—even affection. Here

was a large company, including some of the very highest names in

England; the Party seem to have remained together for more than a

fortnight, or, if one went, the place was filled immediately by

another not less distinguished by the advantages of birth and

fortune; Hook's is the only untitled name, except a led captain and

chaplain or two, and some misses of musical celebrity. What a

struggle he has to maintain! Every Thursday he must meet the printer

of the John Bull to arrange the paper for Saturday's impression. While the rest are shooting or hunting, he clears his head as well

as he can, and steals a few hours to write his articles. When they

go to bed on Wednesday night, he smuggles himself into a

post-chaise, and is carried fifty miles across the country, to some

appointed Blue Boar, or Crooked Billet. Thursday morning is spent in

overhauling correspondence,—in all the details of the editorship. He, with hard driving, gets back to the neighbourhood of the castle

when the dressing-bell is ringing. Mr. Hook's servant has intimated

that his master is slightly indisposed; he enters the gate as if

from a short walk in the wood; in half an hour, behold him answering

placidly the inquiries of the ladies,—his headache fortunately gone

at last,—quite ready for the turtle and champagne,—puns rattle like

a hail-shower,—'that dear Theodore' had never been more brilliant. At a decorous

hour the great lord and his graver guests retire; it

is supposed that the evening is over,—that the house is shut up. But

Hook is quartered in a long bachelor's gallery, with half a dozen

bachelors of far different calibre. One of them, a dashing young

earl, proposes what the diary calls 'something comfortable' in his

dressing-room. Hook, after his sleepless night and busy day,

hesitates,—but is persuaded. The broiled bones are attended by more

champagne, Roman punch, hot brandy and water, finally; for there are

plenty of butlers and grooms of the chamber ready to minister to the

delights of the distant gallery, ever productive of fees to man and

maid. The end is, that they play deep, and that Theodore loses a

great deal more money than he had brought with him from town, or

knows how to come at if he were there. But he rises next morning

with a swimming, bewildered head, and, as the fumes disperse,

perceives that he must write instantly for money. No difficulty is

to be made; the fashionable tailor (alias merciless Jew) to whom he

discloses the case, must on any terms remit a hundred pounds by

return of post. It is accomplished,—the debt is discharged. Thursday

comes round again, and again he escapes to meet the printer. This

time the printer brings a payment of salary with him, and Hook

drives back to the castle in great glee. Exactly the same scene

occurs a night or two afterwards. The salary all goes. When the time

comes for him at last to leave his splendid friend, he finds that he

has lost a fortnight as respects a book that must be finished within

a month or six weeks; and that what with travelling expenses hither

and thither (he has to defray the printer's, too), and losses at

play to silken coxcombs,—who consider him an admirable jack-pudding,

and also as an invaluable pigeon, since he drains his glass as well

as fills it,—he has thrown away more money than he could have earned

by the labour of three months in his own room at Fulham. But then

the rumble of the green chariot is seen well stocked with pheasants

and hares, as it pauses in passing through town at Crockford's, the

Carlton, or the Athenæum; and as often as the Morning Post alluded

to the noble peer's Christmas court, Mr. Theodore Hook's name closed

the paragraph of 'fashionable intelligence.'"

But at last the end of all came, and the poor

jester and bon-vivant

strutted off the stage. To the last, even when positively ill, he

could not refuse an invitation to dine with titled people. To the

last,—a padded-up old man,—he tried to be effervescent and gay. He

died in August, 1841, and the play was ended. Some may call such a

life as this a tragedy, and a painful one it seems. To look at it

now, there appears little genuine mirth in it: the laughter was all

hollow. As for the noble and titled friends for whom Hook had made

so much merriment during his unhappy life, they let him die

overburdened with debt, and go to his grave unwept and unattended. They did nothing for his children,—it is true they were such as the

respectable world usually disown; and they did not, so far as we

know, place a stone over the grave in which their jester was laid to

sleep. Notwithstanding Theodore Hook's naturally brilliant

powers,—his sagacity, his humour, his genius,—we fear that the

verdict of his survivors and of posterity will be, that here was the

life of a greatly gifted man worse than wasted.

――――♦――――

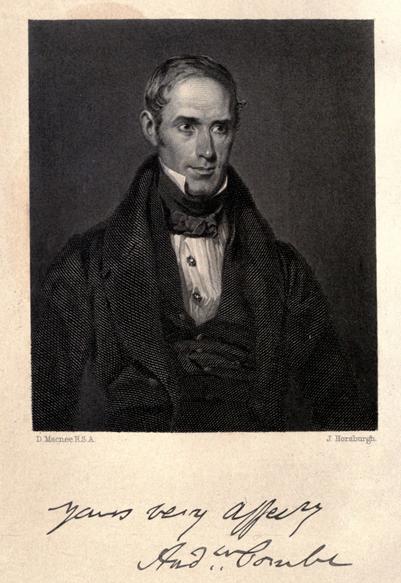

DR. ANDREW COMBE.

Andrew Combe (1797-1847), Scottish physiologist.

Picture Internet Text Archive.

THE life of

Andrew Combe was quiet and unostentatious. It was chiefly occupied

by the investigations and labours incident to the calling which be

had chosen,—that of medicine;—a profession which, when followed

successfully, leaves comparatively little leisure for the indulgence

of literary tastes. Yet we do not exaggerate when we say, that there

are few writers who have effected greater practical good, and done

more to beneficially affect the moral and physical well-being of

mankind, than the subject of this memoir. He was one of the first

writers who directed public attention to the subject of Physiology

in connection with Health and Education. There had, indeed, been no

want of writers on physiology previous to his time; but they

addressed themselves mainly to the professional mind; and their

books were, for the most part, so full of technical phrases, that,

so far as the public was concerned, they might as well have been

written in an unknown tongue. As Dr. Combe grew up towards manhood,

and acquired habits of independent observation, he perceived that

the majority of men and women were, for the most part, living in

habitual violation of the laws of health, and thus bringing upon

themselves debility, disease, premature decay, and death: not to

speak of generations unborn, on whom the penalty of neglect or

violation of the physiological laws inevitably descends. He

conceived the idea of instructing the people in those laws, in a

simple and intelligible manner, and in language divested of

technical terms. And there are words enough in the English

tongue in which to utter commonsense to common people upon such

subjects as air, exercise, diet, cleanliness, and so on, as

affecting the healthy lives of human beings, without drawing so

largely as had been customary upon Greek and Latin terminology for

the purpose.

Dr. Combe's first book, on "The Principles of Physiology

applied to the Preservation of Health, and to the Improvement of

Physical and Mental Education," was written in this rational and

commonsense style. In that work, Dr. Combe appealed to the

ordinary, average understandings of men. He explained the laws

which regulate the physical life,—the conditions necessary for the

healthy action of the various functions of the system; and he

directed particular attention to those habits and practices which

were in violation of the natural laws, pointing out the necessity

for amendment in various ways, in a cogent, persuasive, and

perspicuous manner. We remember very well the appearance of

the book in question. It excited comparatively small attention

at first,—the subject was so unusual, and up to that time deemed so

unattractive. People were afraid then, as they often are now,

to look into their own physical system, and learn something of its

working. There is alarm to many minds, in the thought of the

heart beating, and the lungs blowing, and the arteries contracting

upon their red blood. The consideration of such subjects used

formerly to be regarded as strictly professional; and people were

for the most part satisfied to leave health, and all that concerned

it, to the exclusive charge of "the doctors." And, truth to

say, medical men were disposed to regard the publication of Dr.

Combe's "Physiology" as somewhat "infra dig.;" for it looked

like a revealing of the secrets of the profession before the eyes of

the general public. But all such feeling has long since

disappeared; and medical men now find that they have in the readers

of good works on popular physiology more intelligent patients to

deal with,—more able to co-operate with them in their attempts to

subdue disease and restore the bodily functions to health,—than when

they have mere blank ignorance and blind prejudice to encounter.

Where there is not sound information, there will always be found

prejudices enough,—the most difficult of all things to contend

against. It is not improbable, also, that to the growing

popular knowledge of physiological conditions we are, in a great

measure, to attribute the improvement in the medical profession

which has taken place of late years. For medical men are the

better for knowing that, in order to make good their influence and

to advance as a profession, they must keep well ahead of the

intelligence of their employers. Everybody knows that

questions of health,—as affecting the sanitary condition of

towns,—are among the leading questions of this day; and we cannot

help attributing much of the active concern which now exists among

legislators, philanthropists, and all public-spirited men, for the

improvement of the physical condition of the people, to the impulse

given to the subject by the publication of Dr. Combe's admirable

books.

Dr. Combe was himself a serious sufferer through neglect of

the laws of physical health; and it was probably this circumstance

which early directed his attention to the subject, and induced him

to give it the prominency which he did in nearly all his published

works. He was the fifteenth child of respectable parents,

living in Edinburgh: his father was a brewer at Livingston's Yards,

a suburb of the Old Town, situated nearly under the southwest angle

of Edinburgh Castle rock. Seventeen children in all were born

to the Combes in that place; but the neighbourhood abounded with

offensive pools and ditches, the noxious influence of which (in

conjunction with defective ventilation in small or overcrowded

sleeping apartments) must have been a potent cause of the disease

and early mortality which prevailed in the family. Very few of

the seventeen children grew up to adult years; and although the

parents, who were of robust constitution, lived to an old age, those

of the children who survived grew up with feeble constitutions, and,

in Andrew's case, containing within them the seeds of serious

disease. Nor was the mental discipline of the children of a

much healthier kind. As an illustration, George Combe, in the

Life of his brother, recently published, gives the following picture

of the Sabbath, as spent in a Scotch family:—

"The gate of the brewery was

locked, and all except the most necessary work was suspended.

The children rose at eight, breakfasted at nine, and were taken to

the West Church at eleven. The forenoon service lasted till

one. There was a lunch between one and two. The

afternoon's service lasted from two till four. They then

dined; and after dinner, portions of the Psalms and of the Shorter

Catechism with the 'Proofs' were prescribed to be learnt by heart.

After these had been repeated, tea was served. Next the

children sat round a table and read the Bible aloud, each a verse in

turn, till a chapter for every reader had been completed.

After this, sermons or other pious works were read till nine

o'clock, when supper was served, after which all retired to rest.

Jaded and exhausted in brain and body as the children were by the

performance of heavy tasks at school during six days of the week,

these Sundays were no days of rest to them."

From a private school, Andrew Combe proceeded to the High

School, and then he was placed apprentice to an Edinburgh surgeon.

He was singularly obstinate in connection with his entry upon his

profession. Although he had chosen to be "a doctor," when

finally asked "what he would be," his answer in the vernacular

Scotch was, "I'll no be naething." He would give no further

answer; and after all kinds of "fleechin" and persuading were tried,

he at length had to be carried by force out of the house, to

begin his professional career! His father and brother George,

afterwards his biographer, with a younger brother, James, performed

this remarkable duty. George thus describes the scene.

"A consultation was now held as to what was to be

done; and again it was resolved that Andrew should not be allowed to

conquer, seeing that he still assigned no reason for his resistance.

He was, therefore, lifted from the ground; he refused to stand; but

his father supported one shoulder, George carried the other, and his

younger brother, James, pushed him on behind; and in this fashion he

was carried from the house, through the brewery, and several hundred

yards along the high road, before he placed a foot on the ground.

His elder brother John, observing what was passing, anxiously

inquired, 'What's the matter?' James replied, 'We are taking

Andrew to the doctor.' 'To the doctor! what's the matter with

him,—is he ill, James?' 'O, not at all,—we are taking him to

make him a doctor.' At last, Andrew's sense of shame

prevailed, and he walked quietly. His father and George

accompanied him to Mr. Johnston's house; Andrew was introduced and

received, and his father left him. George inquired what had

passed in Mr. Johnston's presence. 'Nothing particular,'

replied his father; 'only my conscience smote me when Mr. Johnston

hoped that Andrew had come quite willingly! I replied,

that I had given him a solemn promise that, if he did not like the

profession after a trial, he should be at liberty to leave it.'

'Quite right,' said Mr. Johnston; and Andrew was conducted to the

laboratory. Andrew returned to Mr. Johnston's the next morning

without being asked to do so and to the day of his death he was fond

of his profession.

In a touching letter to George, written nearly thirty years

after the above event, he thanked him cordially for having been

instrumental in sending him to a liberal profession; and he

confesses that he really "wished and meant to be a doctor,"

notwithstanding his absurd way of showing his willingness.

Always ready, as both he and his brother were, to account for

everything phrenologically, he attributed the resistance on the

occasion to Wit and Secretiveness. "I recollect well," he says

in the letter referred to,

"that my habitual phrase was, 'I'll no be naething.'

This was universally construed to mean, 'I'll be naething.'

The true meaning I had in view was what the words bore, 'I will be

something;' and the clew to the riddle was, that my Wit was

tickled at school by the rule that 'two negatives make an

affirmative,' and I was diverted with the mystification their use

and literal truth produced in this instance. In no one

instance did mortal man or woman hear me say seriously, (if ever,)

'I'll be naething.' All this is as clear to me as if of

yesterday's occurrence, and the double entendre was a source

of internal chuckling to me. You may say, Why, then, so

unwilling to go to Mr. Johnston's? That is a natural question,

and touches upon another feature altogether. I was a dour

[stubborn] boy, when not taken in the right way, and for a time

nothing would then move me. Once committed, I resolved not to

yield, and hence the laughable extravaganza which ensued."

At the age of fifteen, Andrew Combe went to live with his

elder brother George, who in 1812 began practising as Writer to the

Signet. This was an advantage to Andrew, in point of health,

and was a convenience to him in attending his place of business, and

also the medical lectures in the University. In his letters to

his brother, written in after life, Andrew often referred with

regret to the neglect of ventilation, ablution, and bathing, in his

father's family; to which he attributed the premature deaths of the

greater number, and the impaired constitutions of the few who

survived. Our parents," he said in one letter,

"erred from sheer ignorance; but what are we to think

of the mechanical and tradesman-like views of a medical man who

could see all these causes of disease existing, and producing these

results year after year, without its ever occurring to him that it

was part of his solemn duty to warn his employers, and try to remedy

the evil? All parties were anxious to cure the disease,

but no one sought to remove its causes; and yet so entirely were the

causes within the control of reason and knowledge, that my

conviction has long been complete, that, if we had been properly

treated from infancy, we should, even with the constitutions we

possessed at birth, have survived in health and active usefulness to

a good old age, unless cut off by some acute disease."

But nearly all medical men were alike empirical in those days.

They merely attacked the symptoms which presented themselves; and

when these were overcome, their task was accomplished. That

medical men are now so careful in directing their measures towards

the prevention as well as the cure of disease, we have to

thank Dr. Combe, Edwin Chadwick, and other popular writers and

labourers in the cause of Public Health.

At the early age of nineteen, Andrew Combe passed at

Surgeons' Hall. He used afterwards to say, that it would have

been better for him had he been then only commencing his studies.

Shortly after, Dr. Spurzheim, the phrenologist, visited Edinburgh,

and attracted many ardent admirers, of whom George Combe, then a

young man, shortly became one. Andrew, like most of the

medical men of the day, was at first disposed to laugh at the new

science; but before many years had passed, he too became an ardent

disciple of Dr. Spurzheim. He afterwards attributed much of

the improvement of his mind and character to his study of this

science, and to the practical application of its principles to his

own case. In 1817 he went to Paris, where he studied under

Dupuytren, Alibert, Esquirol, Richerand, and other celebrated men.

He also cultivated the friendship of Dr. Spurzheim, and pursued his

observations and studies in Phrenology. From Paris, he

proceeded with a friend on a walking tour through Switzerland and

the north of Italy. Disregarding the laws of health, he

injured his delicate constitution by exposure, irregular diet, and

over-fatigue; and on his return to Edinburgh, shortly after, he was

seized with a serious illness, the beginning of long-continued lung

disease. He removed for a season to the south of England, and

then proceeded to Italy, wintering at Leghorn. There his cough

left him, and he regained his health and strength so far as to be

enabled to practise for a time as a physician among the English in

that town and Pisa. Returning to Edinburgh in 1823, he

regularly settled down in that city as a medical practitioner.

In this profession he was very successful. His quiet

manner, suavity, and kindness, good sense, attention, professional

abilities, and gentlemanly demeanour, secured him many friends; and

he won them to his heart by his truthful candour, and by the manner

in which he sought to obtain their intelligent co-operation in the

remedial measures which he thought proper to employ. He deemed

it as much a part of his duty to instruct his patients as to the

conditions which regulate the healthy action of the bodily organs,

as to administer drugs to them for the purpose of curing their

immediate ailments. But he found great obstacles in his way,

in consequence of the previous ignorance of most people—even those

considered well educated—as to the simplest laws which regulate the

animal economy. Hence he very early felt the necessity of

improving this department of elementary instruction; and with that

view he set about composing his works on popular physiology.

His first appearance as an author was in the pages of the

Phrenological Journal,—an excellent periodical now defunct.

To the subject of Phrenology he devoted considerable attention, and

soon became known as one of its ablest defenders. Some of his

friends told him that be would injure his professional standing and

connection by the prominency of his advocacy of the new views; but

be persevered, nevertheless, "firmly trusting in the sustaining

power of truth;" and he afterwards found that, instead of being

professionally injured, he was greatly benefited by the labour which

he bestowed upon the study and exposition of the science. To

Phrenology he attributed, in a great measure, the direction of his

attention to the subject of hygienic principles; and after his mind

had been fairly opened to the importance of those principles, he not

only reduced them to practice in his own personal habits, but

laboured to disseminate a knowledge of them among the public

generally.

In the midst of the arduous duties of his profession, Dr. Combe was

more than once under the necessity of leaving home and going abroad

for the benefit of his health. Disease had fixed upon his lungs, and

he felt that his life could only be preserved by removing to a

milder air. He travelled to Paris, to Orleans, to Nantes, to Lyons,

to Naples, to Rome, returning rather improved, but with his lungs

full of tubercles. For many years his life hung as by a thread, and

it was only by his careful observance of the laws of health that he

was enabled to survive. In his work on "The Principles of

Physiology" speaking of the advantages experienced in his own person

of paying implicit obedience to the physiological laws, he says:

"Had

he not been fully aware of the gravity of his own situation, and,

from previous knowledge of the admirable adaptation of the

physiological laws to carry on the machinery of life, disposed to

place implicit reliance on the superior advantages of fulfilling

them, as the direct dictates of Divine Wisdom, he would never have

been able to persevere in the course chalked out for him, with that

ready and long-enduring regularity and cheerfulness which have

contributed so much to their successful fulfilment and results. And,

therefore, he feels himself entitled to call upon those who,

impatient at the slowness of their progress, are apt after a time to

disregard all restrictions, to take a sounder view of their true

position, to make themselves acquainted with the real dictates of

the organic laws; and having done so, to yield them full, implicit,

and persevering obedience, in the certain assurance that they will

reap their reward in renewed health, if recovery be still possible;

and if not, that they will thereby obtain more peace of mind and

bodily ease than by any other means which they can use."

Dr. Combe's first published book was on "Phrenology applied to the

Treatment of Insanity." It was given to the world in 1831, and

proved very successful, being soon out of print. His second book was

on "The Principles of Physiology," some chapters of which were first

published in the Phrenological Journal. This book was published in

1834. Among the booksellers it was regarded with aversion. It was

one of the successful books which booksellers sometimes reject. The

first edition, of 750 copies, and a second edition, of 1,000 copies,

both printed at the author's expense, were sold off; when Dr. Combe

offered to dispose of the copyright to John Murray, without naming

terms. Mr. Murray, and all the other London publishers who were

applied to, declined to have anything to do with the purchase of the

copyright; and the author went on publishing the book at his own

expense. We need scarcely say that the book had a great run: about

30,000 copies were sold in England, besides numerous editions in the

United States.

Although Dr. Combe was enabled at intervals to resume his practice

in Edinburgh, he found it necessary to leave it from time to time

for the benefits of a Continental residence; until, in 1836, he was

induced to accept the appointment of Physician to the King of the

Belgians, believing that a residence at Brussels might possibly suit

his constitution. But his health again gave way on reaching

Brussels, and he was shortly under the necessity of giving up the

appointment,—preserving, however, the honorary office of Consulting

Physician to the Belgian Court. During the leisure which the

cessation from professional pursuits afforded him, he prepared his

next work, on "The Physiology of Digestion," another highly

successful book. And in 1840 appeared his last work, on "The

Physiological and Moral Management of Infancy." All these books have

had a large circulation in England and in America, besides having

been translated and circulated largely in Continental countries.

In 1841 Dr. Combe was again attacked with hæmoptysis, or discharge

of blood from the lungs, and fell into a state of gradual and steady

decline. As he himself said, "I believe I am going slowly and gently

down hill." He continued, however, to live for several years. In

1842 and 1843, he paid two visits to Madeira, and spent some time in

Italy; and in the two following years he was enabled to travel

about, a pallid invalid, taking a deep interest meanwhile in all

useful public and social movements. His judgment seemed to grow

stronger, and his insight into men and things clearer, as his bodily

powers decayed. On all topics connected with education, as his

correspondence shows, he took an especially lively interest. In 1847

he made a voyage to New York, chiefly for the purpose of visiting

his brother William, who had long been settled in the States; but

the heat of the climate proved too trying for his enfeebled

constitution, and he almost immediately took ship again for England. The last literary labour in which he occupied himself was thoroughly

characteristic of the man. While in the States, he had been sickened

by the accounts of the ravages which the ship-fever had made among

the poor Irish emigrants, and he determined to bring the whole

subject before the public in an article in the Times. Writing to a

corn merchant in Liverpool, on his return home, for information as

to the regulations of emigrant ships, he said: "I have not yet

regained either my ordinary health or power of thinking, and,

consequently, find writing rather heavy work; but my spirit is moved

by the horrible details from Quebec and New York, and I cannot

rest without doing something in the matter." The letter in which

this passage occurred was the last that Dr. Combe wrote. His article

had meanwhile been hastily prepared, and it appeared in the Times of

the 17th of September, 1847, occupying nearly three columns of that

paper. He was interrupted, even while he was writing it, by a severe

attack of the diarrhoea, from which he died, after a few days'

illness, on the 9th of August, 1847. His dying hours were peaceful,

and the last words he uttered, when he could scarcely articulate,

were, "Happy, happy!"

Such is a brief outline of the life of an eminently, useful man,

who, without the aid of any brilliant qualities, and merely by the

exercise of industry, good sense, and well-cultivated moral

feelings, was enabled to effect a large amount of good during his

lifetime, and beneficially to influence the condition of mankind, it

may be for generations to come.

――――♦――――

ROBERT BROWNING.

Robert Browning (1812-89): playwright and major English poet;

husband of the poetess

Elizabeth Barrett.

THE following

sonnet, addressed by Walter Savage Landor to Robert Browning, blends

the just judgment of the critic with the tender admiration of the

friend:—

|

"There is delight in singing, though none

hear

Beside the singer: and there is delight

In praising, though the praiser sit alone

And see the praised far off him, far above.

Shakespeare is not our poet, but the world's,

Therefore on him no speech! and brief for thee,

Browning! Since Chaucer was alive and hale,

No man hath walkt along our roads with step

So active, so inquiring eye, or tongue

So varied in discourse. But warmer climes

Give brighter plumage, stronger wing: the breeze

Of Alpine heights thou playest with, borne on

Beyond Sorrento and Amalfi, where

The Siren waits thee, singing song for song." |

A little piece of Browning's, entitled "Home Thoughts, from

Abroad," shows how this stout traveller along the common roads of

England remembered, far away in Italy, what he saw and heard at

home:—

|

"O, to be in England

Now that April's there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brush-wood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England—now!

"And after April, when May follows,

And the white-throat builds, and all the swallows,—

Hark! where my blossomed pear-tree in the hedge

Leans to the field, and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops,—at the bent spray's edge, —

That's the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

"And though the fields look rough with hoary dew,

All will be gay when noontide wakes anew

The buttercups, the little children's dower,

—Far brighter than this gaudy melon-flower!" |

Mr. Browning was born in Camberwell, a suburb of London, in

the year 1812. His father was a Dissenter, and he received his

collegiate education at the London University, after which, at the

age of about twenty, he visited Italy. Here, first and last,

he has spent many years, and a large number of his poems are

inspired by Italian scenes and legends. They show that his

inquiring eye and active step have been busy, not only in the

libraries and closets of that storied land, but along the highways

and by-paths and among the common people of the country. His

first published work was "Paracelsus," which appeared in 1835.

It is a dramatic poem, of a strikingly original character, of the

class to which belong Prometheus, Faust, Festus, and other works, in

which poets of all ages have sought to penetrate the mysteries of

existence and of human destiny. The Paracelsus of history, who

is physician, alchemist, quack, juggler, drunkard, and the father of

modern chemistry, appears in this poem as a high and sovereign

intellect aspiring after the secrets of the world, yet dying

disappointed and heart-broken, having forfeited success by seeking

to transcend the necessities and limitations of humanity, instead of

patiently working within them. This poem drew towards Mr.

Browning the immediate attention of the critics, ever on the

look-out for the coming great poet. On the whole, they

received Paracelsus kindly, and the most thoughtful men in England

and America have agreed that it contains much fine poetry, as well

as nice metaphysical thought. In 1837 Mr. Browning published

"Strafford," a purely English tragedy, which, although placed upon

the stage by Mr. Macready, who represented the principal character,

did not meet with great success. Three years afterwards

appeared "Sordello," another dramatic poem, upon which various

opinions have been pronounced. Most of the current criticism

of the time is written in a hurry, and "Sordello" was not to be

digested or even read in a day. It was rough, tangled, and to

a large degree unintelligible to most readers. Some students

of poetry who had leisure and a taste for occult mysteries tried

their hands at it, and came to the conclusion that it had a great

deal of meaning and many beautiful passages. But the early

judgment has not been reversed during the twenty years which have

elapsed since the poem was given to the world. Perhaps the

best description of it is that given by an American critic, who says

it was a fine poem before the author wrote it. If Mr. Browning

had stopped here, the world would not have recognized him, as it now

does, as one of the greatest dramatic poets since Shakespeare's day.

He kept on writing, and between 1842 and 1846 produced, under the

title of "Bells and Pomegranates," a series of dramas and lyrics, or

dramatic poems, for the lyrics are as dramatic, almost, as the

dramas, upon which his fame thus far chiefly rests. The dramas

are entitled "Pippa Passes," "King Victor and King Charles," "Colombe's

Birthday," "A Blot in the 'Scutcheon," "The Return of the Druses,"

"Luria," and "A Soul's Tragedy." In these poems, Mr. Browning

displays that depth, clearness, minuteness, and universality of

vision, that power of revealing the object of his thought without

revealing himself, that force of imagination which "turns the common

dust of servile opportunity to gold," and that humour which sees

remote and fanciful resemblances and develops their secret

relationship to each other, which constitute the true poet and the

great dramatist. The "Blot in the 'Scutcheon" is a piteous

tragedy. It was produced at Drury Lane in 1843, but its

success was moderate. This proves only that the applause of

the pit is not the test of dramatic merit, for it is almost a

perfect work. "Pippa Passes" is also a charming poem. In

it occurs the following remarkable figure, startling as the

lightning itself.

|

"OTTIMA (to her paramour).

"Buried in woods we lay, you recollect;

Swift ran the searching tempest overhead;

And ever and anon some bright white shaft

Burnt through the pine-tree roof,—here burnt and there,

As if God's messenger through the close wood screen

Plunged and replunged his weapon at a venture,

Feeling for guilty thee and me." |

Some of the lyrics and romances included in this collection

of poems have passed into the school-books and standard collections

of poetry; for instance, "The Pied Piper of Hamelin," "How they

brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix," and "The Lost Leader;"

while others, among which may be mentioned the "Soliloquy of the

Spanish Cloister" and "Sibrandus Schafnaburgensis," display a

quaintness of humour which makes them exceedingly pleasant reading.

The following little piece shows with what quick and rapid strokes

Mr. Browning can place a vivid natural picture and a bit of personal

experience before the eye of the reader:—

|

"MEETING AT NIGHT."

"The grey sea and the long, black land;

And the yellow half-moon, large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow

And quench its speed in the slushy sand.

II.

"Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch,

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!" |

In 1850 Mr. Browning published a poem in two parts, entitled

"Christmas Eve and Easter Day." It deals with theological

problems, and expresses some phases of the author's spiritual

experience with great force and vividness. It also furnishes a

remarkable instance of the ease with which Mr. Browning puts into

melodious verse the elaborate niceties of a metaphysical argument,

diversifying it with picturesque and humorous descriptions.

Some of the pictures of country people and rural life are as

faithful and minute as those of Crabbe. And here is a sketch

of a Göttingen Rationalist Professor, which exhibits the same

fidelity and accuracy of detail, with a touch of the author's

peculiar humour:—

|

"But hist!—a buzzing and emotion!

All settle themselves, the while ascends

By the creaking rail to the lecture desk,

Step by step, deliberate

Because of his cranium's overweight,

Three parts sublime to one grotesque,

If I have proved an accurate guesser,

The hawk-nosed, high-cheek-boned Professor.

I felt at once as if there ran

A shoot of love from my heart to the man,—

That sallow, virgin-minded, studious

Martyr to mild enthusiasm,

As he uttered a kind of cough-preludious

That woke my sympathetic spasm,

(Beside some spitting that made me sorry,)

And stood, surveying his auditory,

With a wan, pure look, well-nigh celestial.—

—Those blue eyes had survived so much!

While, under the foot they could not smutch,

Lay all the fleshly and the bestial.

Over he bowed, and arranged his notes,

Till the auditory's clearing of throats

Was done with, died into a silence;

And, when each glance was upward sent,

Each bearded mouth composed intent,

And a pin might be heard drop half a mile hence,—

He pushed back higher his spectacles,

Let the eyes stream out like lamps from cells,

And giving his head of hair—a hake

Of undressed tow, for colour and quantity—

One rapid and impatient shake,

As our own young England adjusts a jaunty tie,

(When about to impart, on mature digestion,

Some thrilling view of the surplus question,)

—The Professor's grave voice, sweet though hoarse,

Broke into his Christmas-eve's discourse." |

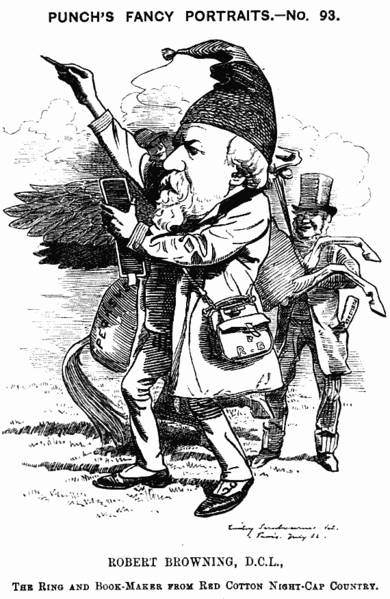

1882 Caricature from Punch. Picture

Wikipedia.

Mr. Browning's latest work is entitled "Men and Women."

It is a collection of fifty poems, which display all the rich and

various qualities of his genius. We quote one of the most

pleasing of the poems in this volume:—

|

EVELYN HOPE.

I.

Beautiful Evelyn Hope is dead!

Sit and watch by her side an hour;

That is her bookshelf, this her bed;

She plucked that piece of geranium-flower,

Beginning to die too in the glass.

Little has yet been changed, I think,—

The shutters are shut, no light may pass

Save two long rays through the hinge's chink.

II.

"Sixteen years old when she died!

Perhaps she had scarcely heard my name,

It was not her time to love: beside,

Her life had many a hope and aim,

Duties enough and little cares,

And now was quiet, now astir,—

Till God's hand beckoned unawares,

And the sweet white brow is all of her.

III.

"Is it too late then, Evelyn Hope?

What, your soul was pure and true,

The good stars met in your horoscope,

Made you of spirit, fire, and dew,—

And just because I was thrice as old,

And our paths in the world diverged so wide,

Each was naught to each, must I be told?

We were fellow-mortals, naught beside?

IV.

"No, indeed! for God above

Is great to grant, as mighty to make,

And creates the love to reward the love,—

I claim you still, for my own love's sake!

Delayed it may be for more lives yet,

Through worlds I shall traverse, not a few,—

Much is to learn and much to forget

Ere the time be come for taking you.

V.

"But the time will come,—at last it will,—

When, Evelyn Hope, what meant, I shall say,

In the lower earth, in the years long still,

That body and soul so pure and gay?

Why your hair was amber, I shall divine,

And your mouth of your own geranium's red,—

And what you would do with me, in fine,

In the new life come in the old one's stead.

VI.

"I have lived, I shall say, so much since then;

Given up myself so many times,

Gained me the gains of various men,

Ransacked the ages, spoiled the climes;

Yet one thing, one, in my soul's full scope,

Either I missed, or itself missed me,—

And I want and find you, Evelyn Hope!

What is the issue? let us see!

VII.

"I loved you, Evelyn, all the while;

My heart seemed full as it could hold,—

There was place and to spare for the frank, young smile,

And the red young mouth, and the hair's young gold.

So, hush,—I will give you this leaf to keep, —

See, I shut it inside the sweet cold hand.

There, that is our secret! go to sleep;

You will wake, and remember, and understand." |

The last piece in "Men and Women" is a beautiful love poem

addressed to E. B. B., the poet's wife. In November, 1846, Mr.

Browning was married to Elizabeth Barrett, of whom a biographical

sketch is included in this volume. Since their marriage, Mr.

and Mrs. Browning have generally resided at Casa Guidi in Florence,

but they occasionally pass a winter in Rome. Mr. George S.

Hillard, an American author, says:

"A happier home and a more perfect union than theirs

it is not easy to imagine; and this completeness arises, not only

from the rare qualities which each possesses, but from their

adaptation to each other. It is a privilege to know such

beings, singly and separately, but to see their powers quickened,

and their happiness rounded by the sacred tie of marriage, is a

cause for peculiar and lasting gratitude. A union so complete

as theirs—in which the mind has nothing to crave nor the heart to

sigh for—is cordial to behold and soothing to remember."

Mr. Browning's thoughtful lines on the perishableness of fame

may sadden the minds of ambitious poets:—

|

"See, as the prettiest graves will do in

time,

Our poet's wants the freshness of its prime;

Spite of the sexton's browsing horse, the sods

Have struggled through its binding osier-rods;

Headstone and half-sunk footstone lean awry,

Wanting the brick-work promised by and by;

How the minute gray lichens, plate o'er plate,

Have softened down the crisp-cut name and date!" |

|

Carte-de-visite

by Elliott & Fry. |

Forty years ago, Mr. Jeffrey uttered a lament

over the forgotten poets; forgotten merely because there was not

room in men's memories for them. He consoled himself with the

reflection that Campbell and Byron and Scott and Crabbe and Southey,

and the other poets of his day, might live, in unequal proportions,