|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER V.

ROADS AND TRAVELLING IN ENGLAND TOWARDS

THE END OF LAST CENTURY.

THE progress made

in the improvement of the roads throughout England was exceedingly

slow. Though some of the main throughfares were mended so as

to admit of stage-coach travelling at the rate of from four to six

miles an hour, the less frequented roads continued to be all but

impassable. Travelling was still difficult, tedious, and

dangerous. Only those who could not well avoid it ever thought

of undertaking a journey, and travelling for pleasure was out of the

question. A writer in the 'Gentleman's Magazine' in 1752 says

that a Londoner at that time would no more think of travelling into

the west of England for pleasure than of going to Nubia.

But signs of progress were not awanting. In 1749

Birmingham started a stage-coach, which made the journey to London

in three days. [p.73] In

1754 some enterprising Manchester men advertised a "flying coach"

for the conveyance of passengers between that town and the

metropolis; and, lest they should be classed with projectors of the

Munchausen kind, they heralded their enterprise with this statement:

"However incredible it may appear, this coach will actually (barring

accidents) arrive in London in four days and a half after leaving

Manchester! "

Fast coaches were also established on several of the northern

roads, though not with very extraordinary results as to speed.

When John Scott, afterwards Lord Chancellor Eldon, travelled from

Newcastle to Oxford in 1766, he mentions that he journeyed in what

was denominated "a fly," because of its rapid travelling; yet he was

three or four days and nights on the road. There was no such

velocity, however, as to endanger overturning or other mischief.

On the panels of the coach were painted the appropriate motto of

Sat cito si sat bene—quick enough if well enough—a motto which

the future Lord Chancellor made his own. [p.74]

The journey by coach between London and Edinburgh still

occupied six days or more, according to the state of the weather.

Between Bath or Birmingham and London occupied between two and three

days as late as 1763. The road across Hounslow Heath was so

bad, that it was stated before a Parliamentary Committee that it was

frequently known to be two feet deep in mud. The rate of

travelling was about six and a half miles an hour; but the work was

so heavy that it "tore the horses' hearts out," as the common saying

went, so that they only lasted two or three years.

When the Bath road became improved, Burke was enabled, in the

summer of 1774, to travel from London to Bristol, to meet the

electors there, in little more than four and twenty hours; but his

biographer takes care to relate that he "travelled with incredible

speed." Glasgow was still ten days' distance from the

metropolis, and the arrival of the mail there was so important an

event that a gun was fired to announce its coming in.

Sheffield set up a "flying machine on steel springs" to London in

1760: it "slept" the first night at the Black Man's Head Inn,

Nottingham; the second at the Angel, Northampton; and arrived at the

Swan with Two Necks, Lad-lane, on the evening of the third day.

The fare was £1. 17s., and 14 lbs. of luggage was allowed. But

the principal part of the expense of travelling was for living and

lodging on the road, not to mention the fees to guards and drivers.

Though the Dover road was still one of the best in the

kingdom, the Dover flying-machine, carrying only four passengers,

took a long summer's day to perform the journey. It set out

from Dover at four o'clock in the morning, breakfasted at the Red

Lion, Canterbury, and the passengers ate their way up to town at

various inns on the road, arriving in London in time for supper.

Smollett complained of the innkeepers along that route as the

greatest set of extortioners in England. The deliberate style

in which journeys were performed may be inferred from the

circumstance that on one occasion, when a quarrel took place between

the guard and a passenger, the coach stopped to see them fight it

out on the road.

Foreigners who visited England were peculiarly observant of

the defective modes of conveyance then in use. Thus, one Don

Manoel Gonzales, a Portuguese merchant, who travelled through Great

Britain in 1740, speaking of Yarmouth, says, "They have a comical

way of carrying people all over the town and from the seaside, for

six pence. They call it their coach, but it is only a

wheel-barrow drawn by one horse, without any covering."

Another foreigner, Herr Alberti, a Hanoverian professor of theology,

when on a visit to Oxford in 1750, desiring to proceed to Cambridge,

found there was no means of doing so without returning to London and

there taking coach for Cambridge. There was not even the

convenience of a carrier's waggon between the two universities.

But the most amusing account of an actual journey by stage-coach

that we know of, is that given by a Prussian clergyman, Charles H.

Moritz, who thus describes his adventures on the road between

Leicester and London in 1782:—

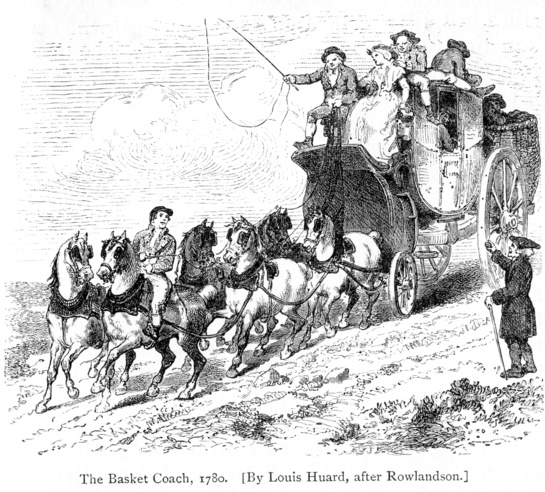

"Being obliged," he says, "to

bestir myself to get back to London, as the time drew near when the

Hamburgh captain with whom I intended to return had fixed his

departure, I determined to take a place as far as Northampton on the

outside. But this ride from Leicester to Northampton I shall

remember as long as I live.

"The coach drove from the yard through a part of the house.

The inside passengers got in from the yard, but we on the outside

were obliged to clamber up in the street, because we should have had

no room for our heads to pass under the gateway. My companions

on the top of the coach were a farmer, a young man very decently

dressed, and a black-amoor. The getting up alone was at the

risk of one's life, and when I was up I was obliged to sit just at

the corner of the coach, with nothing to hold by but a sort of

little handle fastened on the side. I sat nearest the wheel,

and the moment that we set off I fancied that I saw certain death

before me. All I could do was to take still tighter hold of

the handle, and to be strictly careful to preserve my balance.

The machine rolled along with prodigious rapidity over the stones

through the town, and every moment we seemed to fly into the air, so

much so that it appeared to me a complete miracle that we stuck to

the coach at all. But we were completely on the wing as often

as we passed through a village or went down a hill.

"This continual fear of death at last became insupportable to

me, and, therefore, no sooner were we crawling up a rather steep

hill, and consequently proceeding slower than usual, than I

carefully crept from the top of the coach, and was lucky enough to

get myself snugly ensconced in the basket behind.

"'O, Sir, you will be shaken to death!' said the black-amoor;

but I heeded him not, trusting that he was exaggerating the

unpleasantness of my new situation. And truly, as long as we

went on slowly up hill it was easy and pleasant enough; and I was

just on the point of falling asleep among the surrounding trunks and

packages, having had no rest the night before, when on a sudden the

coach proceeded at a rapid rate down the hill. Then all the

boxes, iron-nailed and copper-fastened, began, as it were, to dance

around me; everything in the basket appeared to be alive, and every

moment I received such violent blows that I thought my last hour had

come. The black-a-moor had been right, I now saw clearly; but

repentance was useless, and I was obliged to suffer horrible torture

for nearly an hour, which seemed to me an eternity. At last we

came to another hill, when, quite shaken to pieces, bleeding, and

sore, I ruefully crept back to the top of the coach to my former

seat. 'Ah, did I not tell you that you would be shaken to

death?' inquired the black man, when I was creeping along on my

stomach. But I gave him no reply. Indeed, I was ashamed;

and I now write this as a warning to all strangers who are inclined

to ride in English stage-coaches, and take an outside seat, or,

worse still, horror of horrors, a seat in the basket.

"From Harborough to Northampton I had a most dreadful

journey. It rained incessantly, and as before we had been

covered with dust, so now we were soaked with rain. My

neighbour, the young man who sat next me in the middle, every now

and then fell asleep; and when in this state he perpetually bolted

and rolled against me, with the whole weight of his body, more than

once nearly pushing me from my seat, to which I clung with the last

strength of despair. My forces were nearly giving way, when at

last, happily, we reached Northampton, on the evening of the 14th

July, 1782, an ever-memorable day to me.

"On the next morning, I took an inside place for London.

We started early in the morning. The journey from Northampton

to the metropolis, however, I can scarcely call a ride, for it was a

perpetual motion, or endless jolt from one place to another, in a

close wooden box, over what appeared to be a heap of unhewn stones

and trunks of trees scattered by a hurricane. To make my

happiness complete, I had three travelling companions, all farmers,

who slept so soundly that even the hearty knocks with which they

hammered their heads against each other and against mine did not

awake them. Their faces, bloated and discoloured by ale and

brandy and the knocks aforesaid, looked, as they lay before me, like

so many lumps of dead flesh.

"I looked, and certainly felt, like a crazy fool when we

arrived at London in the afternoon." [p.79]

Arthur Young, in his books, inveighs strongly against the

execrable state of the roads in all parts of England towards the end

of last century. In Essex he found the ruts "of an incredible

depth," and he almost swore at one near Tilbury. "Of all the

cursed roads," he says; "that ever disgraced this kingdom in the

very ages of barbarism, none ever equalled that from Billericay to

the King's Head at Tilbury. It is for near twelve miles so

narrow that a mouse cannot pass by any carriage. I saw a

fellow creep under his waggon to assist me to lift, if possible, my

chaise over a hedge. To add to all the infamous circumstances

which concur to plague a traveller, I must not forget the eternally

meeting with chalk waggons, themselves frequently stuck fast, till a

collection of them are in the same situation, and twenty or thirty

horses may be tacked to each to draw them out one by one!" [p.80]

Yet will it be believed, the proposal to form a turnpike-road from

Chelmsford to Tilbury was resisted "by the Bruins of the country,

whose horses were worried to death with bringing chalk through those

vile roads!"

Arthur Young did not find the turnpike any better between

Bury and Sudbury, in Suffolk: "I was forced to move as slow in it,"

he says, "as in any unmended lane in Wales. For, ponds of

liquid dirt, and a scattering of loose flints just sufficient to

lame every horse that moves near them, with the addition of cutting

vile grips across the road under the pretence of letting the water

off, but without effect, altogether render at least twelve out of

these sixteen miles as infamous a turnpike as ever was beheld."

Between Tetsworth and Oxford he found the so-called turnpike

abounding in loose stones as large as one's head, full of holes,

deep ruts, and withal so narrow that with great difficulty he got

his chaise out of the way of the Witney waggons. "Barbarous"

and "execrable" are the words which he constantly employs in

speaking of the roads; parish and turnpike, all seemed to be alike

bad. From Gloucester to Newnham, a distance of twelve miles,

he found a "cursed road," "infamously stony," with "ruts all the

way." From Newnham to Chepstow he noted another bad feature in

the roads, and that was the perpetual hills; "for," he says, "you

will form a clear idea of them if you suppose the country to

represent the roofs of houses joined, and the road to run across

them." It was at one time even a matter of grave dispute

whether it would not cost as little money to make that between

Leominster and Kington navigable as to make it hard. Passing

still further west, the unfortunate traveller, who seems scarcely

able to find words to express his sufferings, continues:—

"But, my dear Sir, what am I to

say of the roads in this country! the turnpikes! as they have the

assurance to call them and the hardiness to make one pay for?

From Chepstow to the half-way house between Newport and Cardiff they

continue mere rocky lanes, full of hugeous stones as big as one's

horse, and abominable holes. The first six miles from Newport

they were so detestable, and without either direction-posts or

milestones, that I could not well persuade myself I was on the

turnpike, but had mistook the road, and therefore asked every one I

met, who answered me, to my astonishment, 'Ya-as!'

Whatever business carries you into this country, avoid it, at least

till they have good roads: if they were good, travelling would be

very pleasant." [p.81]

At a subsequent period Arthur Young visited the northern

counties; but his account of the roads in that quarter is not more

satisfactory. Between Richmond and Darlington he found them

like to "dislocate his bones," being broken in many places into deep

holes, and almost impassable; "yet," says he, "the people will

drink tea!"—a decoction against the use of which the traveller is

found constantly declaiming. The roads in Lancashire made him

almost frantic, and he gasped for words to express his rage.

Of the road between Proud Preston and Wigan he says: "I know not in

the whole range of language terms sufficiently expressive to

describe this infernal road. Let me most seriously caution all

travellers who may accidentally propose to travel this terrible

country, to avoid it as they would the devil; for a thousand to one

they break their necks or their limbs by overthrows or

breakings-down. They will here meet with ruts, which I

actually measured, four feet deep, and floating with mud only

from a wet summer. What, therefore, must it be after a winter?

The only mending it receives is tumbling in some loose stones, which

serve no other purpose than jolting a carriage in the most

intolerable manner. These are not merely opinions, but facts;

for I actually passed three carts broken down in those

eighteen miles of execrable memory." [p.82]

It would even appear that the bad state of the roads in the

Midland counties, about the same time, had nearly caused the death

of the heir to the throne. On the 2nd of September, 1789, the

Prince of Wales left Wentworth Hall, where he had been on a visit to

Earl Fitzwilliam, and took the road for London in his carriage.

When about two miles from Newark the Prince's coach was overturned

by a cart in a narrow part of the road; it rolled down a slope,

turning over three times, and landed at the bottom, shivered to

pieces. Fortunately the Prince escaped with only a few bruises

and a sprain; but the incident had no effect in stirring up the

local authorities to make any improvement in the road, which

remained in the same wretched state until a comparatively recent

period.

When Palmer's new mail-coaches were introduced, an attempt

was made to diminish the jolting of the passengers by having the

carriages hung upon new patent springs, but with very indifferent

results. Mathew Boulton, the engineer, thus described their

effect upon himself in a journey he made in one of them from London

into Devonshire, in 1787:—

"I had the most disagreeable

journey I ever experienced the night after I left you, owing to the

new improved patent coach, a vehicle loaded with iron trappings and

the greatest complication of unmechanical contrivances jumbled

together, that I have ever witnessed. The coach swings

sideways, with a sickly sway without any vertical spring; the point

of suspense bearing upon an arch called a spring, though it is

nothing of the sort. The severity of the jolting occasioned me

such disorder that I was obliged to stop at Axminster and go to bed

very ill. However, I was able next day to proceed in a

post-chaise. The landlady in the London Inn, at Exeter,

assured me that the passengers who arrived every night were in

general so ill that they were obliged to go supperless to bed; and,

unless they go back to the old-fashioned coach, hung a little lower,

the mail-coaches will lose all their custom." [p.83]

We may briefly refer to the several stages of improvement if

improvement it could be called—in the most frequented highways of

the kingdom, and to the action of the legislature with reference to

the extension of turnpikes. The trade and industry of the

country had been steadily improving; but the greatest obstacle to

their further progress was always felt to be the disgraceful state

of the roads. As long ago as the year 1663 an Act was passed [p.84-1]

authorising the first toll-gates or turnpikes to be erected at which

collectors were stationed to levy small sums from those using the

road, for the purpose of defraying the needful expenses of their

maintenance. This Act, however, only applied to a portion of

the Great North Road between London and York, and it authorised the

new toll-bars to be erected at Wade's Mill in Hertfordshire, at

Caxton in Cambridgeshire, and at Stilton in Huntingdonshire. [p.84-2]

The Act was not followed by any others for a quarter of a century,

and even after that lapse of time such Acts as were passed of a

similar character were very few and far between.

For nearly a century more, travellers from Edinburgh to

London met with no turnpikes until within about 110 miles of the

metropolis. North of that point there was only a narrow

causeway fit for pack-horses, flanked with clay sloughs on either

side. It is, however, stated that the Duke of Cumberland and

the Earl of Albemarle, when on their way to Scotland in pursuit of

the rebels in 1746, did contrive to reach Durham in a coach and six;

but there the roads were found so wretched, that they were under the

necessity of taking to horse, and Mr. George Bowes, the county

member, made his Royal Highness a present of his nag to enable him

to proceed on his journey. The roads west of Newcastle were so

bad, that in the previous year the royal forces under General Wade,

which left Newcastle for Carlisle to intercept the Pretender and his

army, halted the first night at Ovingham, and the second at Hexham,

being able to travel only twenty miles in two days. [p.85]

The rebellion of 1745 gave a great impulse to the

construction of roads for military as well as civil purposes.

The nimble Highlanders, without baggage or waggons, had been able to

cross the border and penetrate almost to the centre of England

before any definite knowledge of their proceedings had reached the

rest of the kingdom. In the metropolis itself little

information could be obtained of the movements of the rebel army for

several days after they had left Edinburgh. Light of foot,

they outstripped the cavalry and artillery of the royal army, which

were delayed at all points by impassable roads. No sooner,

however, was the rebellion put down, than Government directed its

attention to the best means of securing the permanent subordination

of the Highlands, and with this object the construction of good

highways was declared to be indispensable. The expediency of

opening up the communication between the capital and the principal

towns of Scotland was also generally admitted; and from that time,

though slowly, the construction of the main high routes between

north and south made steady progress.

The extension of the turnpike system, however, encountered

violent opposition from the people, being regarded as a grievous tax

upon their freedom of movement from place to place. Armed

bodies of men assembled to destroy the turnpikes; and they burnt

down the toll-houses and blew up the posts with gunpowder. The

resistance was the greatest in Yorkshire, along the line of the

Great North Road towards Scotland, though riots also took place in

Somersetshire and Gloucestershire, and even in the immediate

neighbourhood of London. One fine May morning, at Selby, in

Yorkshire, the public bellman summoned the inhabitants to assemble

with their hatchets and axes that night at midnight, and cut down

the turnpikes erected by Act of Parliament; nor were they slow to

act upon his summons. Soldiers were then sent into the

district to protect the toll-bars and the toll-takers; but this was

a difficult matter, for the toll-gates were numerous, and wherever a

"pike" was left unprotected at night, it was found destroyed in the

morning. The Yeadon and Otley mobs, near Leeds, were

especially violent. On the 18th of June, 1753, they made quite

a raid upon the turnpikes, burning or destroying about a dozen in

one week. A score of the rioters were apprehended, and while

on their way to York Castle a rescue was attempted, when the

soldiers were under the necessity of firing, and many persons were

killed and wounded.

The prejudices entertained against the turnpikes were so

strong, that in some places the country people would not even use

the improved roads after they were made. [p.87-1]

For instance, the driver of the Marlborough coach obstinately

refused to use the New Bath road, but stuck to the old waggon-track,

called "Ramsbury." He was an old man, he said: his grandfather

and father had driven the aforesaid way before him, and he would

continue in the old track till death. [p.87-2]

Petitions were also presented to Parliament against the

extension of turnpikes; but the opposition represented by the

petitioners was of a much less honest character than that of the

misguided and prejudiced country folks, who burnt down the

toll-houses. It was principally got up by the agriculturists

in the neighbourhood of the metropolis, who, having secured the

advantages which the turnpike-roads first constructed had conferred

upon them, desired to retain a monopoly of the improved means of

communication. They alleged that if turnpike-roads were

extended into the remoter counties, the greater cheapness of labour

there would enable the distant farmers to sell their grass and corn

cheaper in the London market than themselves, and that thus they

would be ruined. [p.88]

This opposition, however, did not prevent the progress of turnpike

and highway legislation; and we find that, from 1760 to 1774, no

fewer than four hundred and fifty-two Acts were passed for making

and repairing highways. Nevertheless the roads of the kingdom

long continued in a very unsatisfactory state, chiefly arising from

the extremely imperfect manner in which they were made.

Road-making as a profession was as yet unknown.

Deviations were made in the old roads to make them more easy and

straight; but the deep ruts were merely filled up with any materials

that lay nearest at hand, and stones taken from the quarry, instead

of being broken and laid on carefully to a proper depth, were

tumbled down and roughly spread, the country road-maker trusting to

the operation of cart-wheels and waggons to crush them into a proper

shape. Men of eminence as engineers—and there were very few

such at the time—considered road-making beneath their consideration;

and it was even thought singular that, in 1768, the distinguished

Smeaton should have condescended to make a road across the valley of

the Trent, between Markham and Newark.

The making of the new roads was thus left to such persons as

might choose to take up the trade, special skill not being thought

at all necessary on the part of a road-maker. It is only in

this way that we can account for the remarkable fact, that the first

extensive maker of roads who pursued it as a business, was not an

engineer, nor even a mechanic, but a Blind Man, bred to no trade,

and possessing no experience whatever in the arts of surveying or

bridge-building, yet a man possessed of extraordinary natural gifts,

and unquestionably most successful as a road-maker. We allude

to John Metcalf, commonly known as "Blind Jack of Knaresborough," to

whose biography, as the constructor of nearly two hundred miles of

capital roads—as, indeed, the first great English road-maker—we

propose to devote the next chapter.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VI.

JOHN METCALF, ROAD-MAKER.

JOHN

METCALF [p.90] was born at

Knaresborough in 1717, the son of poor working people. When

only six years old he was seized with virulent small-pox, which

totally destroyed his sight. The blind boy, when sufficiently

recovered to go abroad, first learnt to grope from door to door

along the walls on either side of his parents' dwelling. In

about six months he was able to feel his way to the end of the

street and back without a guide, and in three years he could go on a

message to any part of the town. He grew strong and healthy,

and longed to join in the sports of boys of his age. He went

bird-nesting with them, and climbed the trees while the boys below

directed him to the nests, receiving his share of eggs and young

birds. Thus he shortly became an expert climber, and could

mount with ease any tree that he was able to grasp. He rambled

into the lanes and fields alone, and soon knew every foot of the

ground for miles round Knaresborough. He next learnt to ride,

delighting above all things in a gallop. He contrived to keep

a dog and coursed hares: indeed, the boy was the marvel of the

neighbourhood. His unrestrainable activity, his acuteness of

sense, his shrewdness, and his cleverness, astonished everybody.

The boy's confidence in himself was such, that though blind, he was

ready to undertake almost any adventure. Among his other arts he

learned to swim in the Nidd, and became so expert that on one

occasion he saved the lives of three of his companions. Once, when

two men were drowned in a deep part of the river, Metcalf was sent

for to dive for them, which he did, and brought up one of the bodies

at the fourth diving: the other had been carried down the stream. He

thus also saved a manufacturer's yarn, a large quantity of which had

been carried by a sudden flood into a deep hole under the High

Bridge. At home, in the evenings, he learnt to play the fiddle, and

became so skilled on the instrument, that he was shortly able to

earn money by playing dance music at country parties. At Christmas

time he played waits, and during the Harrogate season he played to

the assemblies at the 'Queen's Head' and the 'Green Dragon.'

On one occasion, towards dusk, he acted as guide to a belated

gentleman along the difficult road from York to Harrogate. The road

was then full of windings and turnings, and in many places it was no

better than a track across unenclosed moors. Metcalf brought the

gentleman safe to his inn, 'The Granby,' late at night, and was

invited to join in a tankard of negus. On Metcalf leaving the room,

the gentleman observed to the landlord —"I think, landlord, my guide

must have drunk a great deal of spirits since we came here." "Why

so, Sir?" "Well, I judge so, from the appearance of his eyes." "Eyes!

bless you, Sir," rejoined the landlord, "don't you know that he

is blind?" "Blind! What do you mean by that?" "I mean, Sir, that he

cannot see—he is as blind as a stone." "Well, landlord," said the

gentleman, "this is really too much: call him in." Enter Metcalf "My

friend, are you really blind?" "Yes, Sir," said he, "I lost my sight

when six years old." "Had I known that, I would not have ventured

with you on that road from York for a hundred pounds." "And I,

Sir," said Metcalf, "would not have lost my way for a thousand."

Metcalf having thriven and saved money, bought and rode a horse of

his own. He had a great affection for the animal, and when he

called, it would immediately answer him by neighing. The most

surprising thing is that he was a good huntsman; and to follow the

hounds was one of his greatest pleasures. He was as bold a rider as

ever took the field. He trusted much, no doubt, to the sagacity of

his horse; but he himself was apparently regardless of danger. The

hunting adventures which are related of him, considering his

blindness, seem altogether marvellous. He would also run his horse

for the petty prizes or plates given at the "feasts" in the

neighbourhood, and he attended the races at York and other places,

where he made bets with considerable skill, keeping well in his

memory the winning and losing horses. After the races, he would

return to Knaresborough late at night, guiding others who but for

him could never have made out the way.

On one occasion he rode his horse in a match in Knaresborough

Forest. The ground was marked out by posts, including a circle of a

mile, and the race was three times round. Great odds were laid

against the blind man, because of his supposed inability to keep the

course. But his ingenuity was never at fault. He procured a number

of dinner-bells from the Harrogate inns and set men to ring them at

the several posts. Their sound was enough to direct him during the

race, and the blind man came in the winner! After the race was over,

a gentleman who owned a notorious runaway horse came up and offered

to lay a bet with Metcalf that he could not gallop the horse fifty

yards and stop it within two hundred. Metcalf accepted the bet, with

the condition that he might choose his ground. This was agreed to,

but there was to be neither hedge nor wall in the distance. Metcalf

forthwith proceeded to the neighbourhood of the large bog near the

Harrogate Old Spa, and having placed a person on the line in which

he proposed to ride, who was to sing a song to guide him by its

sound, he mounted and rode straight into the bog, where he had the

horse effectually stopped within the stipulated two hundred yards,

stuck up to his saddle-girths in the mire. Metcalf scrambled out and

claimed his wager; but it was with the greatest difficulty that the

horse could be extricated.

The blind man also played at bowls very successfully, receiving the

odds of a bowl extra for the deficiency of each eye. He had thus

three bowls for the other's one; and he took care to place one

friend at the jack and another midway, who, keeping up a constant

discourse with him, enabled him readily to judge of the distance. In

athletic sports, such as wrestling and boxing, he was also a great

adept; and being now a full-grown man, of great strength and

robustness, about six feet two in height, few durst try upon him the

practical jokes which cowardly persons are sometimes disposed to

play upon the blind.

Notwithstanding his mischievous tricks and youthful wildness, there

must have been something exceedingly winning about the man,

possessed, as he was, of a strong, manly, and affectionate nature;

and we are not, therefore, surprised to learn that the landlord's

daughter of 'The Granby' fairly fell in love with Blind Jack and

married him, much to the disgust of her relatives. When asked how it

was that she could marry such a man, her womanlike reply was,

"Because I could not be happy without him: his actions are so

singular, and his spirit so manly and enterprising, that I could not

help loving him." But, after all, Dolly was not so far wrong in the

choice as her parents thought her. As the result proved, Metcalf had

in him elements of success in life, which, even according to the

world's estimate, made him eventually a very "good match," and the

woman's clear sight in this case stood her in good stead.

But before this marriage was consummated, Metcalf had wandered far

and "seen" a good deal of the world, as he termed it. He travelled

on horseback to Whitby, and from thence he sailed for London, taking

with him his fiddle, by the aid of which he continued to earn enough

to maintain himself for several weeks in the metropolis. Returning

to Whitby, he sailed from thence to Newcastle to "see" some friends

there, whom he had known at Harrogate while visiting that

watering-place. He was welcomed by many families and spent an

agreeable month, afterwards visiting Sunderland, still supporting

himself by his violin playing. Then he returned to Whitby for his

horse, and rode homeward alone to Knaresborough by Pickering, Malton,

and York, over very bad roads, the greater part of which he had

never travelled before, yet without once missing his way. When he

arrived at York, it was the dead of night, and he found the city

gates at Middlethorp shut. They were of strong planks, with iron

spikes fixed on the top; but throwing his horse's bridle-rein over

one of the spikes, he climbed up, and by the help of a corner of the

wall that joined the gates, he got safely over: then opening them

from the inside, he led his horse through.

After another season at Harrogate, he made a second visit to London,

in the company of a North countryman who played the small pipes. He

was kindly entertained by Colonel Liddell, of Ravensworth Castle,

who gave him a general invitation to his house. During this visit,

which was in 1740-1, Metcalf ranged freely over the metropolis,

visiting Maidenhead and Reading, and returning by Windsor and

Hampton Court. The Harrogate season being at hand, he prepared to

proceed thither,—Colonel Liddell, who was also about setting out for

Harrogate, offering him a seat behind his coach. Metcalf thanked

him, but declined the offer, observing that he could, with great

ease, walk as far in a day as he, the Colonel, was likely to travel

in his carriage; besides, he preferred the walking. That a blind man

should undertake to walk a distance of two hundred miles over an

unknown road, in the same time that it took a gentleman to perform

the same distance in his coach, dragged by post-horses, seems almost

incredible; yet Metcalf actually arrived at Harrogate before the

Colonel, and that without hurrying by the way. The circumstance is

easily accounted for by the deplorable state of the roads, which

made travelling by foot on the whole considerably more expeditious

than travelling by coach. The story is even extant of a man with a

wooden leg being once offered a lift upon a stagecoach; but he

declined, with "Thank'ee, I can't wait; I'm in a hurry." And he

stumped on, ahead of the coach.

The account of Metcalf's journey on foot from London to Harrogate is

not without a special bearing on our subject, as illustrative of the

state of the roads at the time. He started on a Monday morning,

about an hour before the Colonel in his carriage, with his suite,

which consisted of sixteen servants on horseback. It was arranged

that they should sleep that night at Welwyn, in Hertfordshire.

Metcalf made his way to Barnet; but a little north of that town,

where the road branches off to St. Albans, he took the wrong way,

and thus made a considerable detour. Nevertheless he arrived at

Welwyn first, to the surprise of the Colonel. Next morning he set

off as before, reached Biggleswade; but there he found the river

swollen and no bridge provided to enable travellers to cross to the

further side. He made a considerable circuit, in the hope of finding

some method of crossing the stream, and was so fortunate as to fall

in with a fellow wayfarer, who led the way across some planks,

Metcalf following the sound of his feet. Arrived at the other side,

Metcalf, taking some pence from his pocket, said, "Here, my good

fellow, take that and get a pint of beer." The stranger declined,

saying he was welcome to his services. Metcalf, however, pressed

upon his guide the small reward, when the other asked, "Pray, can

you see very well?" "Not remarkably well," said Metcalf. "My

friend," said the stranger, "I do not mean to tithe you: I am the

rector of this parish; so God bless you, and I wish you a good

journey." Metcalf set forward again with the blessing, and reached

his journey's end safely, again before the Colonel. On the Saturday

after their setting out from London, the travellers reached Wetherby,

where Colonel Liddell desired to rest until the Monday; but Metcalf

proceeded on to Harrogate, thus completing the journey in six

days,—the Colonel arriving two days later.

He now renewed his musical performances at Harrogate, and was also

in considerable request at the Ripon assemblies, which were attended

by most of the families of distinction in that neighbourhood. When

the season at Harrogate was over, he retired to Knaresborough with

his young wife, and having purchased an old house, he had it pulled

down and another built on its site,—he himself getting the requisite

stones for the masonry out of the bed of the adjoining river. The

uncertainty of the income derived from musical performances led him

to think of following some more settled pursuit, now that he had a

wife to maintain as well as himself. He accordingly set up a

four-wheeled and a one-horse chaise for the public

accommodation,—Harrogate up to that time being without any vehicle

for hire. The innkeepers of the town having followed his example,

and abstracted most of his business, Metcalf next took to

fish-dealing. He bought fish at the coast, which he conveyed on

horseback to Leeds and other towns for sale. He continued

indefatigable at this trade for some time, being on the road often

for nights together; but he was at length forced to abandon it in

consequence of the inadequacy of the returns. He was therefore under

the necessity of again taking up his violin; and he was employed as

a musician in the Long Room at Harrogate, at the time of the

outbreak of the Rebellion of 1745.

The news of the rout of the Royal army at Prestonpans, and the

intended march of the Highlanders southwards, put a stop to business

as well as pleasure, and caused a general consternation throughout

the northern counties. The great bulk of the people were, however,

comparatively indifferent to the measures of defence which were

adopted; and but for the energy displayed by the country gentlemen

in raising forces in support of the established government, the

Stuarts might again have been seated on the throne of Britain. Among

the county gentlemen of York who distinguished themselves on the

occasion was William Thornton, Esq., of Thornville Royal. The county

having voted ninety thousand pounds for raising, clothing, and

maintaining a body of four thousand men, Mr. Thornton proposed, at a

public meeting held at York, that they should be embodied with the

regulars and march with the King's forces to meet the Pretender in

the field. This proposal was, however, overruled, the majority of

the meeting resolving that the men should be retained at home for

purposes merely of local defence. On this decision being come to,

Mr. Thornton determined to raise a company of volunteers at his own

expense, and to join the Royal army with such force as he could

muster. He then went abroad among his tenantry and servants, and

endeavoured to induce them to follow him, but without success.

Still determined on raising his company, Mr. Thornton next cast

about him for other means; and who should he think of in his

emergency but Blind Jack! Metcalf had often played to his family at

Christmas time, and the Squire knew him to be one of the most

popular men in the neighbourhood. He accordingly proceeded to

Knaresborough to confer with Metcalf on the subject. It was then

about the beginning of October, only a fortnight after the battle of Prestonpans. Sending for Jack to his inn, Mr. Thornton told him of

the state of affairs—that the French were coming to join the

rebels—and that if the country were allowed to fall into their

hands, no man's wife, daughter, nor sister would be safe. Jack's

loyalty was at once kindled. If no one else would join the Squire,

he would! Thus enlisted—perhaps carried away by his love of

adventure not less than by his feeling of patriotism—Metcalf

proceeded to enlist others, and in two days a hundred and forty men

were obtained, from whom Mr. Thornton drafted sixty-four, the

intended number of his company. The men were immediately drilled and

brought into a state of as much efficiency as was practicable in the

time; and when they marched off to join General Wade's army at Boroughbridge, the Captain said to them on setting out, "My lads!

you are going to form part of a ring-fence to the finest estate in

the world!" Blind Jack played a march at the head of the company,

dressed in blue and buff, and in a gold-laced hat. The Captain said

he would willingly give a hundred guineas for only one eye to put in

Jack's head: he was such a useful, spirited, handy fellow.

On arriving at Newcastle, Captain Thornton's company was united to

Pulteney's regiment, one of the weakest. The army lay for a week in

tents on the Moor. Winter had set in, and the snow lay thick on the

ground; but intelligence arriving that Prince Charles, with his

Highlanders, was proceeding southwards by way of Carlisle, General

Wade gave orders for the immediate advance of the army on Hexham, in

the hope of intercepting them by that route. They set out on their

march amidst hail and snow; and in addition to the obstruction

caused by the weather, they had to overcome the difficulties

occasioned by the badness of the roads. The men were often three or

four hours in marching a mile, the pioneers having to fill up

ditches and clear away many obstructions in making a practicable

passage for the artillery and baggage. The army was only able to

reach Ovingham, a distance of little more than ten miles, after

fifteen hours' marching. The night was bitter cold; the ground was

frozen so hard that but few of the tent-pins could be driven; and

the men lay down upon the earth amongst their straw. Metcalf, to

keep up the spirits of his company—for sleep was next to

impossible—took out his fiddle and played lively tunes whilst the

men danced round the straw, which they set on fire.

Next day the army marched for Hexham; but the rebels having already

passed southward, General Wade retraced his steps to Newcastle to

gain the high road leading to Yorkshire, whither he marched in all

haste; and for a time his army lay before Leeds on fields now

covered with streets, some of which still bear the names of

Wade-lane, Camp-road, and Camp-field, in consequence of the event. On the retreat of Prince Charles from Derby, General Wade again

proceeded to Newcastle, while the Duke of Cumberland hung upon the

rear of the rebels along their line of retreat by Penrith and

Carlisle. Wade's army proceeded by forced marches into Scotland, and

at length came up with the Highlanders at Falkirk. Metcalf continued

with Captain Thornton and his company throughout all these marchings

and counter-marchings, determined to be of service to his master if

he could, and at all events to see the end of the campaign. At the

battle of Falkirk he played his company to the field; but it was a

grossly-mismanaged battle on the part of the Royalist General, and

the result was a total defeat. Twenty of Thornton's men were made

prisoners, with the lieutenant and ensign. The Captain himself only

escaped by taking refuge in a poor woman's house in the town of

Falkirk, where he lay hidden for many days; Metcalf returning to

Edinburgh with the rest of the defeated army. [p.103]

Some of the Dragoon officers, hearing of Jack's escape, sent for him

to head-quarters at Holyrood, to question him about his Captain. One

of them took occasion to speak ironically of Thornton's men, and

asked Metcalf how he had contrived to escape. "Oh!" said Jack, "I

found it easy to follow the sound of the Dragoons' horses they made

such a clatter over the stones when flying from the Highlandmen." Another asked him how he, a blind man, durst venture upon such a

service; to which Metcalf replied, that had he possessed a pair of

good eyes, perhaps he would not have come there to risk the loss of

them by gunpowder. No more questions were asked, and Jack withdrew;

but he was not satisfied about the disappearance of Captain

Thornton, and determined on going back to Falkirk, within the

enemy's lines, to get news of him, and perhaps to rescue him, if

that were still possible.

The rest of the company were very much disheartened at the loss of

their officers and so many of their comrades, and wished Metcalf to

furnish them with the means of returning home. But he would not hear

of such a thing, and strongly encouraged them to remain until, at

all events, he had got news of the Captain. He then set out for

Prince Charles's camp. On reaching the outposts of the English army,

he was urged by the officer in command to lay aside his project,

which would certainly cost him his life. But Metcalf was not to be

dissuaded, and he was permitted to proceed, which he did in the

company of one of the rebel spies, pretending that he wished to be

engaged as a musician in the Prince's army. A woman whom they met

returning to Edinburgh from the field of Falkirk, laden with

plunder, gave Metcalf a token to her husband, who was Lord George

Murray's cook, and this secured him an access to the Prince's

quarters; but, notwithstanding a most diligent search, he could

hear nothing of his master. Unfortunately for him, a person who had

seen him at Harrogate, pointed him out as a suspicious character,

and he was seized and put in confinement for three days, after which

he was tried by court martial; but as nothing could be alleged

against him, he was acquitted, and shortly after made his escape

from the rebel camp. On reaching Edinburgh, very much to his delight

he found Captain Thornton had arrived there before him.

On the 30th of January, 1746, the Duke of Cumberland reached

Edinburgh, and put himself at the head of the Royal army, which

proceeded northward in pursuit of the Highlanders. At Aberdeen,

where the Duke gave a ball, Metcalf was found to be the only

musician in camp who could play country dances, and he played to the

company, standing on a chair, for eight hours, the Duke several

times, as he passed him, shouting out "Thornton, play up!" Next

morning the Duke sent him a present of two guineas; but as the

Captain would not allow him to receive such gifts while in his pay,

Metcalf spent the money, with his permission, in giving a treat to

the Duke's two body servants. The battle of Culloden, so disastrous

to the poor Highlanders, shortly followed; after which Captain

Thornton, Metcalf, and the Yorkshire Volunteer Company, proceeded

homewards. Metcalf's young wife had been in great fears for the

safety of her blind, fearless, and almost reckless partner; but she

received him with open arms, and his spirit of adventure being now

considerably allayed, he determined to settle quietly down to the

steady pursuit of business.

During his stay in Aberdeen, Metcalf had made himself familiar with

the articles of clothing manufactured at that place, and he came to

the conclusion that a profitable trade might be carried on by buying

them on the spot and selling them by retail to customers in

Yorkshire. He accordingly proceeded to Aberdeen in the following

spring, and bought a considerable stock of cotton and worsted

stockings, which he found he could readily dispose of on his return

home. His knowledge of horseflesh—in which he was, of course,

mainly guided by his acute sense of feeling—also proved highly

serviceable to him, and he bought considerable numbers of horses in

Yorkshire for sale in Scotland, bringing back galloways in return.

It is supposed that at the same time he carried on a profitable

contraband trade in tea and such like articles.

After this, Metcalf began a new line of business, that of common

carrier between York and Knaresborough, plying the first

stage-waggon on that road. He made the journey twice a week in

summer and once a week in winter. He also undertook the conveyance

of army baggage, most other owners of carts at that time being

afraid of soldiers, regarding them as a wild rough set, with whom it

was dangerous to have any dealings. But the blind man knew them

better, and while he drove a profitable trade in carrying their

baggage from town to town, they never did him any harm. By these

means, he very shortly succeeded in realising a considerable store

of savings, besides being able to maintain his family in

respectability and comfort.

Metcalf, however, had not yet entered upon the main business of his

life. The reader will already have observed how strong of heart and

resolute of purpose he was. During his adventurous career he had

acquired a more than ordinary share of experience of the world. Stone blind as he was from his childhood, he had not been able to

study books, but he had carefully studied men. He could read

characters with wonderful quickness, rapidly taking stock, as he

called it, of those with whom he came in contact. In his youth, as

we have seen, he could follow the hounds on horse or on foot, and

managed to be in at the death with the most expert riders. His

travels about the country as a guide to those who could see, as a

musician, soldier, chapman, fish-dealer, horse-dealer, and waggoner,

had given him a perfectly familiar acquaintance with the northern

roads. He could measure timber or hay in the stack, and rapidly

reduce their contents to feet and inches after a mental process of

his own. Withal he was endowed with an extraordinary activity and

spirit of enterprise, which, had his sight been spared him, would

probably have rendered him one of the most extraordinary men of his

age. As it was, Metcalf now became one of the greatest of its

road-makers and bridge-builders.

About the year 1765 an Act was passed empowering a turnpike-road to

be constructed between Harrogate and Boroughbridge. The business of

contractor had not yet come into existence, nor was the art of

road-making much understood; and in a remote country place such as

Knaresborough the surveyor had some difficulty in finding persons

capable of executing the necessary work. The shrewd Metcalf

discerned in the proposed enterprise the first of a series of public

roads of a similar kind throughout the northern counties, for none

knew better than he did how great was the need of them. He

determined, therefore, to enter upon this new line of business, and

offered to Mr. Ostler, the master surveyor, to construct three miles

of the proposed road between Minskip and Fearnsby. Ostler knew the

man well, and having the greatest confidence in his abilities, he

let him the contract. Metcalf sold his stage-waggons and his

interest in the carrying business between York and Knaresborough,

and at once proceeded with his new undertaking. The materials for metaling the road were to be obtained from one gravel-pit for the

whole length, and he made his arrangements on a large scale

accordingly, hauling out the ballast with unusual expedition and

economy, at the same time proceeding with the formation of the road

at all points; by which means he was enabled the first to complete

his contract, to the entire satisfaction of the surveyor and

trustees.

This was only the first of a vast number of similar projects on

which Metcalf was afterwards engaged, extending over a period of

more than thirty years. By the time that he had finished the road,

the building of a bridge at Boroughbridge was advertised, and

Metcalf sent in his tender with many others. At the same time he

frankly stated that, though he wished to undertake the work, he had

not before executed anything of the kind. His tender being on the

whole the most favourable, the trustees sent for Metcalf, and on his

appearing before them, they asked him what he knew of a bridge. He

replied that he could readily describe his plan of the one they

proposed to build, if they would be good enough to write down his

figures. "The span of the arch, 18 feet," said he "being a

semi-circle, makes 27: the arch-stones must be a foot deep, which,

if multiplied by 27, will be 486; and the basis will be 72 feet

more. This for the arch; but it will require good backing, for which

purpose there are proper stones in the old Roman wall at Aldborough,

which may be used for the purpose, if you please to give directions

to that effect." It is doubtful whether the trustees were able to

follow his rapid calculations; but they were so much struck by his

readiness and apparently complete knowledge of the work he proposed

to execute, that they gave him the contract to build the bridge; and

he completed it within the stipulated time in a satisfactory and

workmanlike manner.

He next agreed to make the mile and a half of turnpike-road between

his native town of Knaresborough and Harrogate—ground with which he

was more than ordinarily familiar. Walking one day over a portion of

the ground on which the road was to be made, while still covered

with grass, he told the workmen that he thought it differed from the

ground adjoining it, and he directed them to try for stone or gravel

underneath; and, strange to say, not many feet down, the men came

upon the stones of an old Roman causeway, from which he obtained

much valuable material for the making of his new road. At another

part of the contract there was a bog to be crossed, and the surveyor

thought it impossible to make a road over it. Metcalf assured him

that he could readily accomplish it; on which the other offered, if

he succeeded, to pay him for the straight road the price which he

would have to pay if the road were constructed round the bog. Metcalf set to work accordingly, and had a large quantity of furze

and ling laid upon the bog, over which he spread layers of gravel. The plan answered effectually, and when the materials had become

consolidated, it proved one of the best parts of the road.

It would be tedious to describe in detail the construction of the

various roads and bridges which Metcalf subsequently executed, but a

brief summary of the more important will suffice. In Yorkshire, he

made the roads between Harrogate and Harewood Bridge; between

Chapeltown and Leeds; between Broughton and Addingham; between Mill

Bridge and Halifax; between Wakefield and Dewsbury; between

Wakefield and Doncaster; between Wakefield, Huddersfield, and

Saddleworth (the Manchester road); between Standish and Thurston

Clough; between Huddersfield and Highmoor; between Huddersfield and

Halifax, and between Knaresborough and Wetherby.

In Lancashire also, Metcalf made a large extent of roads, which were

of the greatest importance in opening up the resources of that

county. Previous to their construction, almost the only means of

communication between districts was by horse-tracks and mill-roads,

of sufficient width to enable a laden horse to pass along them with

a pack of goods or a sack of corn slung across its back. Metcalf's

principal roads in Lancashire were those constructed by him between

Bury and Blackburn, with a branch to Accrington; between Bury and Haslingden; and between Haslingden and Accrington, with a branch to

Blackburn. He also made some highly important main roads connecting

Yorkshire and Lancashire with each other at many parts: as, for

instance, those between Skipton, Colne, and Burnley; and between

Docklane Head and Ashton-under-Lyne. The roads from Ashton to

Stockport and from Stockport to Mottram Langdale were also his work.

Our road-maker was also extensively employed in the same way in the

counties of Cheshire and Derby; constructing the roads between

Macclesfield and Chapel-le-Frith, between Whaley and Buxton, between

Congleton and the 'Red Bull' (entering Staffordshire), and in

various other directions. The total mileage of the turnpike-roads

thus constructed was about one hundred and eighty miles, for which

Metcalf received in all about sixty-five thousand pounds. The making

of these roads also involved the building of many bridges,

retaining-walls, and culverts. We believe it was generally admitted

of the works constructed by Metcalf that they well stood the test of

time and use; and, with a degree of justifiable pride, he was

afterwards accustomed to point to his bridges, when others were

tumbling during floods, and boast that none of his had fallen.

This extraordinary man not only made the highways which were

designed for him by other surveyors, but himself personally surveyed

and laid out many of the most important roads which he constructed,

in difficult and mountainous parts of Yorkshire and Lancashire. One

who personally knew Metcalf thus wrote of him during his lifetime:

"With the assistance only of a long staff, I have several times met

this man traversing the roads, ascending steep and rugged heights,

exploring valleys and investigating their several extents, forms,

and situations, so as to answer his designs in the best manner. The

plans which he makes, and the estimates he prepares, are done in a

method peculiar to himself, and of which he cannot well convey the

meaning to others. His abilities in this respect are, nevertheless,

so great that he finds constant employment. Most of the roads over

the Peak in Derbyshire have been altered by his directions,

particularly those in the vicinity of Buxton; and he is at this time

constructing a new one betwixt Wilmslow and Congleton, to open a

communication with the great London road, without being obliged to

pass over the mountains. I have met this blind projector while

engaged in making his survey. He was alone as usual, and, amongst

other conversation, I made some inquiries respecting this new road. It was really astonishing to hear with what accuracy he described

its course and the nature of the different soils through which it

was conducted. Having mentioned to him a boggy piece of ground it

passed through, he observed that 'that was the only place he had

doubts concerning, and that he was apprehensive they had, contrary

to his directions, been too sparing of their materials.'" [p.114]

Metcalf's skill in constructing his roads over boggy ground was very

great and the following may be cited as an instance. When the

high-road from Huddersfield to Manchester was determined on, he

agreed to make it at so much a rood, though at that time the line

had not been marked out. When this was done, Metcalf, to his dismay,

found that the surveyor had laid it out across some deep marshy

ground on Pule and Standish Commons. On this he expostulated with

the trustees, alleging the much greater expense that he must

necessarily incur in carrying out the work after their surveyor's

plan. They told him, however, that if he succeeded in making a

complete road to their satisfaction, he should not be a loser; but

they pointed out that, according to their surveyor's views, it would

be requisite for him to dig out the bog until he came to a solid

bottom. Metcalf, on making his calculations, found that in that case

he would have to dig a trench some nine feet deep and fourteen yards

broad on the average, making about two hundred and ninety-four solid

yards of bog in every rood, to be excavated and carried away. This,

he naturally conceived, would have proved both tedious as well as

costly, and, after all, the road would in wet weather have been no

better than a broad ditch, and in winter liable to be blocked up

with snow. He strongly represented this view to the trustees as well

as the surveyor, but they were immovable. It was, therefore,

necessary for him to surmount the difficulty in some other way,

though he remained firm in his resolution not to adopt the plan

proposed by the surveyor. After much cogitation he appeared again

before the trustees, and made this proposal to them: that he should

make the road across the marshes after his own plan, and then, if it

should be found not to answer, he would be at the expense of making

it over again after the surveyor's proposed method. This was agreed

to; and as he had undertaken to make nine miles of the road within

ten months, he immediately set to work with all despatch.

Nearly four hundred men were employed upon the work at six different

points, and their first operation was to cut a deep ditch along

either side of the intended road, and throw the excavated stuff

inwards so as to raise it to a circular form. His greatest

difficulty was in getting the stones laid to make the drains, there

being no firm footing for a horse in the more boggy places. The

Yorkshire clothiers, who passed that way to Huddersfield market—by

no means a soft-spoken race—ridiculed Metcalf's proceedings, and

declared that he and his men would some day have to be dragged out

of the bog by the hair of their heads! Undeterred, however, by

sarcasm, he persistently pursued his plan of making the road

practicable for laden vehicles but he strictly enjoined his men for

the present to keep his manner of proceeding a secret.

His plan was this. He ordered heather and ling to be pulled from the

adjacent ground, and after binding it together in little round

bundles, which could be grasped with the hand, these bundles were

placed close together in rows in the direction of the line of road,

after which other similar bundles were placed transversely over

them; and when all had been pressed well down, stone and gravel were

led on in broad-wheeled waggons, and spread over the bundles, so as

to make a firm and level way. When the first load was brought and

laid on, and the horses reached the firm ground again in safety,

loud cheers were set up by the persons who had assembled in the

expectation of seeing both horses and waggons disappear in the bog. The whole length was finished in like manner, and it proved one of

the best, and even the driest, parts of the road, standing in very

little need of repair for nearly twelve years after its

construction. The plan adopted by Metcalf, we need scarcely point

out, was precisely similar to that afterwards adopted by George

Stephenson, under like circumstances, when constructing the railway

across Chat Moss. It consisted simply in a large extension of the

bearing surface, by which, in fact, the road was made to float upon

the surface of the bog; and the ingenuity of the expedient proved

the practical shrewdness and mother-wit of the blind Metcalf, as it

afterwards illustrated the promptitude as well as skill of the

clear-sighted George Stephenson.

Metcalf was upwards of seventy years old before he left off

road-making. He was still hale and hearty, wonderfully active for so

old a man, and always full of enterprise. Occupation was absolutely

necessary for his comfort, and even to the last day of his life he

could not bear to be idle. While engaged on road-making in Cheshire,

he brought his wife to Stockport for a time, and there she died,

after thirty-nine years of happy married life. One of Metcalf's

daughters became married to a person engaged in the cotton business

at Stockport, and, as that trade was then very brisk, Metcalf

himself commenced it in a small way. He began with six

spinning-jennies and a carding-engine, to which he afterwards added

looms for weaving calicoes, jeans, and velveteens. But trade was

fickle, and finding that he could not sell his yarns except at a

loss, he made over his jennies to his son-in-law, and again went on

with his road-making. The last line which he constructed was one of

the most difficult he had ever undertaken,--that between Haslingden

and Accrington, with a branch road to Bury. Numerous canals being

under construction at the same time, employment was abundant and

wages rose, so that though he honourably fulfilled his contract, and

was paid for it the sum of £3500, he found himself a loser of

exactly £40 after two years' labour and anxiety. He completed the

road in 1792, when he was seventy-five years of age, after which he

retired to his farm at Spofforth, near Wetherby, where for some

years longer he continued to do a little business in his old line,

buying and selling hay and standing wood, and superintending the

operations of his little farm. During the later years of his career

he occupied himself in dictating to an amanuensis an account of the

incidents in his remarkable life, and finally, in the year 1810,

this strong-hearted and resolute man—his life's work over—laid down

his staff and peacefully departed in the ninety-third year of his

age; leaving behind him four children, twenty grand-children, and

ninety great grand-children.

The roads constructed by Metcalf and others had the effect of

greatly improving the communications of Yorkshire and Lancashire,

and opening up those counties to the trade then flowing into them

from all directions. But the administration of the highways and

turnpikes being entirely local, their good or bad management

depending upon the public spirit and enterprise of the gentlemen of

the locality, it frequently happened that while the roads of one

county were exceedingly good, those of the adjoining county were

altogether execrable.

Even in the immediate vicinity of the metropolis the Surrey roads

remained comparatively unimproved. Those through the interior of

Kent were wretched. When Mr. Rennie, the engineer, was engaged in

surveying the Weald with a view to the cutting of a canal through it

in 1802, he found the country almost destitute of practicable roads,

though so near to the metropolis on the one hand and to the

sea-coast on the other. The interior of the county was then

comparatively untraversed, except by bands of smugglers, who kept

the inhabitants in a state of constant terror. In an agricultural

report on the county of Northampton as late as the year 1813, it was

stated that the only way of getting along some of the main lines of

road in rainy weather, was by swimming!

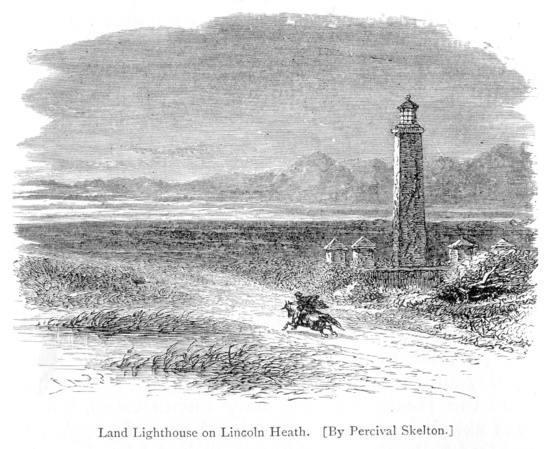

In the neighbourhood of the city of Lincoln the communications were

little better, and there still stands upon what is called Lincoln

Heath—though a heath no longer—a curious memorial of the past in the

shape of Dunstan Pillar, a column seventy feet high, erected about

the middle of last century in the midst of the then dreary, barren

waste, for the purpose of serving as a mark to wayfarers by day and

a beacon to them by night. [p.119] At that time the Heath was not

only uncultivated, but it was also unprovided with a road across it. When the late Lady Robert Manners visited Lincoln from her residence

at Bloxholm, she was accustomed to send forward a groom to examine

some track, that on his return he might be able to report one that

was practicable. Travellers frequently lost themselves upon this

heath. Thus a

family, returning from a ball at Lincoln, strayed from

the track twice in one night, and they were obliged to remain there

until morning. All this is now changed, and Lincoln Heath has become

covered with excellent roads and thriving farmsteads. "This Dunstan

Pillar," says Mr. Pusey, in his review of the agriculture of

Lincolnshire, in 1843, "lighted up no longer time ago for so

singular a purpose, did appear to me a striking witness of the

spirit of industry which, in our own days, has reared the thriving

homesteads around it, and spread a mantle of teeming vegetation to

its very base. And it was certainly surprising to discover at once

the finest farming I had ever seen and the only land lighthouse ever

raised. [p.121-1] Now that the pillar has ceased to cheer the

wayfarer, it may serve as a beacon to encourage other landowners in

converting their dreary moors into similar scenes of thriving

industry." [p.121-2]

When the improvement of the high roads of the country fairly set in,

the progress made was very rapid. This was greatly stimulated by the

important inventions of tools, machines, and engines, made towards

the close of last century, the products of which—more especially of

the steam-engine and spinning-machine—so largely increased the

wealth of the nation. Manufactures, commerce, and shipping, made

unprecedented strides; life became more active; persons and

commodities circulated more rapidly; every improvement in the

internal communications being followed by an increase of ease,

rapidity, and economy in locomotion. Turnpike and post roads were

speedily extended all over the country, and even the rugged mountain

districts of North Wales and the Scotch Highlands became as

accessible as any English county. The riding postman was superseded

by the smartly appointed mail-coach, performing its journeys with

remarkable regularity at the average speed of ten miles an hour. Slow stage-coaches gave place to fast ones, splendidly horsed and

"tooled," until travelling by road in England was pronounced almost

perfect.

But all this was not enough. The roads and canals, numerous and

perfect though they might be, were found altogether inadequate to

the accommodation of the traffic of the country, which had

increased, at a constantly accelerating ratio, with the increased

application of steam power to the purposes of productive industry. At length steam itself was applied to remedy the inconveniences

which it had caused; the locomotive engine was invented, and

travelling by railway became generally adopted. The effect of these

several improvements in the means of locomotion, has been to greatly

increase the public activity, and to promote the general comfort and

well-being. They have tended to bring the country and the town much

closer together; and, by annihilating distance as measured by time,

to make the whole kingdom as one great city. What the personal

blessings of improved communication have been, no one has described

so well as the witty and sensible Sydney Smith:—

"It is of some importance," he wrote, "at what period a man is

born. A young man alive at this period hardly knows to what

improvement of human life he has been introduced; and I would bring

before his notice the changes which have taken place in England

since I began to breathe the breath of life, a period amounting to

over eighty years. Gas was unknown: I groped about the streets of

London in the all but utter darkness of a twinkling oil lamp, under

the protection of watchmen in their grand climacteric, and exposed

to every species of degradation and insult. I have been nine hours

in sailing from Dover to Calais, before the invention of steam. It

took me nine hours to go from Taunton to Bath, before the invention

of railroads; and I now go in six hours from Taunton to London! In

going from Taunton to Bath, I suffered between 10,000 to 12,000

severe contusions, before stone-breaking Macadam was born. . . . As

the basket of stagecoaches in which luggage was then carried had no

springs, your clothes were rubbed all to pieces; and, even in the

best society, one-third of the gentlemen at least were always drunk.

. . I paid £15 in a single year for repairs of carriage-springs on

the pavement of London; and I now glide without noise or fracture on

wooden pavement. I can walk, by the assistance of the police, from

one end of London to the other without molestation; or, if tired,

get into a cheap and active cab, instead of those cottages on wheels

which the hackney coaches were at the beginning of my life. . . .

Whatever miseries I suffered, there was no post to whisk my

complaints for a single penny to the remotest corner of the empire;

and yet, in spite of all these privations, I lived on quietly, and

am now ashamed that I was not more discontented, and utterly

surprised that all these changes and inventions did not occur two

centuries ago."

With the history of these great improvements is also mixed up the

story of human labour and genius, and of the patience and

perseverance displayed in carrying them out. Probably one of the

best illustrations of character in connection with the development

of the inventions of the last century, is to be found in the life of

Thomas Telford, the greatest and most scientific road-maker of his

day, to which we proceed to direct the attention of the reader.

――――♦――――

LIFE OF THOMAS TELFORD.

CHAPTER I.

ESKDALE.

THOMAS

TELFORD was born in one

of the most solitary nooks of the narrow valley of the Esk, in the

eastern part of the county of Dumfries, in Scotland. Eskdale

runs north and south, its lower end having been in former times the

western march of the Scottish border. Near the entrance to the

dale is a tall column erected on Langholm Hill, some twelve miles to

the north of the Gretna Green station of the Caledonian

Railway,—which many travellers to and from Scotland may have

observed,—a monument to the late Sir John Malcolm, Governor of

Bombay, one of the distinguished natives of the district. It

looks far over the English borderlands, which stretch away towards

the south, and marks the entrance to the mountainous parts of the

dale, which lie to the north. From that point upwards the

valley gradually contracts, the road winding along the river's

banks, in some places high above the stream, which rushes swiftly

over the rocky bed below.

A few miles upward from the lower end of Eskdale

lies the little capital of the district, the town of Langholm; and

there, in the market-place, stands another monument to the virtues

of the Malcolm family in the statue erected to the memory of Admiral

Sir Pulteney Malcolm, a distinguished naval officer. Above

Langholm, the country becomes more hilly and moorland. In many

places only a narrow strip of holm land by the river's side is left

available for cultivation; until at length the dale contracts so