|

EARLY ROADS

AND

MODES OF TRAVELLING.

――――♦――――

Artist Percival Skelton.

CHAPTER I.

OLD ROADS.

ROADS have in all

times been among the most influential agencies of society; and the

makers of them, by enabling men readily to communicate with each

other, have properly been regarded as among the most effective

pioneers of civilisation.

Roads are literally the pathways not only of industry, but of

social and national intercourse. Wherever a line of

communication between men is formed, it renders commerce

practicable; and, wherever commerce penetrates, it creates a

civilisation and leaves a history.

Roads place the city and the town in connection with the

village and the farm, open up markets for field produce, and provide

outlets for manufactures. They enable the natural resources of

a country to be developed, facilitate travelling and intercourse,

break down local jealousies, and in all ways tend to bind together

society and bring out fully that healthy spirit of industry which is

the life and soul of every nation.

The road is so necessary an instrument of social well-being,

that in every new colony it is one of the first things thought of.

First roads, then commerce, institutions, schools, churches, and

newspapers. The new country, as well as the old, can only be

effectually "opened up," as the common phrase is, by roads; and

until these are made, it is virtually closed.

Freedom itself cannot exist without free communication,—every

limitation of movement on the part of the members of society

amounting to a positive abridgment of their personal liberty.

Hence roads, canals, and railways, by providing the greatest

possible facilities for locomotion and information, are essential

for the freedom of all classes, of the poorest as well as the

richest.

By bringing the ends of a kingdom together, they reduce the

inequalities of fortune and station, and, by equalising the price of

commodities, to that extent they render them accessible to all.

Without their assistance, the concentrated populations of our large

towns could neither be clothed nor fed; but by their instrumentality

an immense range of country is brought as it were to their very

doors, and the sustenance and employment of large masses of people

become comparatively easy.

In the raw materials required for food, for manufactures, and

for domestic purposes, the cost of transport necessarily forms a

considerable item; and it is clear that the more this cost can be

reduced by facilities of communication, the cheaper those articles

become, and the more they are multiplied and enter into the

consumption of the community at large.

Let any one imagine what would be the effect of closing the

roads, railways, and canals of England. The country would be

brought to a deadlock, employment would be restricted in all

directions, and a considerable proportion of the inhabitants

concentrated in the large towns must at certain seasons inevitably

perish of cold and hunger.

In the earlier periods of English history, roads were of

comparatively less consequence. While the population was thin

and scattered, and men lived by hunting and pastoral pursuits, the

track across the down, the heath, and the moor, sufficiently

answered their purpose. Yet even in those districts

unencumbered with wood, where the first settlements were made—as on

the downs of Wiltshire, the moors of Devonshire, and the wolds of

Yorkshire— stone tracks were laid down by the tribes between one

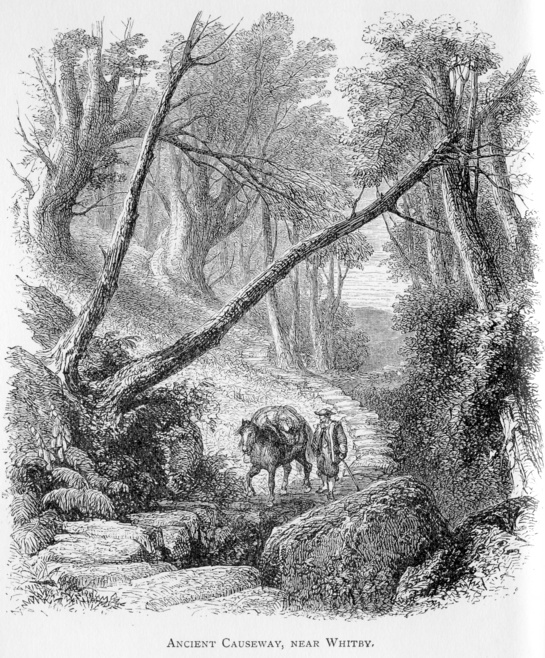

village and another. We have given, at the beginning of this

chapter, a representation of one of those ancient track-ways still

existing in the neighbourhood of Whitby, in Yorkshire; and there are

many of the same description to be met with in other parts of

England. In some districts they are called trackways or

ridgeways, being narrow causeways usually following the natural

ridge of the country, and probably serving in early times as local

boundaries. On Dartmoor they are constructed of stone blocks,

irregularly laid down on the surface of the ground, forming a rude

causeway of about five or six feet wide.

The Romans, with many other arts, first brought into England

the art of road-making. They thoroughly understood the value

of good roads, regarding them as the essential means for the

maintenance of their empire in the first instance, and of social

prosperity in the next. It was their roads, as well as their

legions, that made them masters of the world; and the pickaxe, not

less than the sword, was the ensign of their dominion.

Wherever they went, they opened up the communications of the

countries they subdued, and the roads which they made were among the

best of their kind. They were skilfully laid out and solidly

constructed. For centuries after the Romans left England,

their roads continued to be the main highways of internal

communication, and their remains are to this day to be traced in

many parts of the country. Settlements were made and towns

sprang up along the old "streets;" and the numerous Stretfords,

Stratfords, and towns ending in "le-street"—as Ardwick-le-street, in

Yorkshire, and Chester-le-street, in Durham—mostly mark the

direction of these ancient lines of road. There are also

numerous Stanfords, which were so called because they bordered the

raised military roadways of the Romans, which ran direct between

their stations.

The last-mentioned peculiarity of the roads constructed by

the Romans, must have struck many observers. Level does not

seem to have been of consequence, compared with directness.

This peculiarity is supposed to have originated in an imperfect

knowledge of mechanics; for the Romans do not appear to have been

acquainted with the moveable joint in wheeled carriages. The

carriage-body rested solid upon the axles, which in four-wheeled

vehicles were rigidly parallel with each other. Being unable

readily to turn a bend in the road, it has been concluded that for

this reason all the great Roman highways were constructed in as

straight lines as possible.

On the departure of the Romans from Britain, most of the

roads constructed by them were allowed to fall into decay, on which

the forest and the waste gradually resumed their dominion over them,

and the highways of England became about the worst in Europe. We

find, however, that numerous attempts were made in early times to

preserve the ancient ways and enable a communication to be

maintained between the metropolis and the rest of the country, as

well as between one market town and another.

The state of the highways may be inferred from the character

of the legislation applying to them. One of the first laws on

the subject was passed in 1285, directing that all bushes and trees

along the roads leading from one market to another should be cut

down for two hundred feet on either side, to prevent robbers lurking

therein; [p.5] but nothing was

proposed for amending the condition of the ways themselves. In

1346, Edward III. authorised the first toll to be levied for the

repair of the roads leading from St. Giles's-in-the-Fields to the

village of Charing (now Charing Cross), and from the same quarter to

near Temple Bar (down Drury Lane), as well as the highway then

called Perpoole (now Gray's Inn Lane). The footway at the

entrance of Temple Bar was interrupted by thickets and bushes, and

in wet weather was almost impassable. The roads further west

were so bad that when the sovereign went to Parliament faggots were

thrown into the ruts in King-street, Westminster, to enable the

royal cavalcade to pass along.

In Henry VIII.'s reign, several remarkable statutes were

passed relating to certain worn-out and impracticable roads in

Sussex and the Weald of Kent. From the earliest of these, it

would appear that when the old roads were found too deep and miry to

be passed, they were merely abandoned and new tracks struck out.

After describing "many of the wayes in the wealds as so depe and

noyous by wearyng and course of water and other occasions that

people cannot have their carriages or passages by horses uppon or by

the same but to their great paynes, perill and jeopardie," the Act

provided that owners of land might, with the consent of two justices

and twelve discreet men of the hundred, lay out new roads and close

up the old ones. Another Act passed in the same reign, related

to the repairs of bridges and of the highways at the ends of

bridges.

But as these measures were for the most part merely

permissive, they could have had but little practical effect in

improving the communications of the kingdom. In the reign of

Philip and Mary (in 1555), an Act was passed providing that each

parish should elect two surveyors of highways to see to the

maintenance of their repairs by compulsory labour, the preamble

reciting that "highwaies are now both verie noisome and tedious to

travell in, and dangerous to all passengers and cariages;" and to

this day parish and cross roads are maintained on the principle of

Mary's Act, though the compulsory labour has since been commuted

into a compulsory tax.

In the reigns of Elizabeth and James, other road Acts were

passed; but, from the statements of contemporary writers, it would

appear that they were followed by very little substantial progress,

and travelling continued to be attended with many difficulties.

Even in the neighbourhood of the metropolis, the highways were in

certain seasons scarcely passable. The great Western road into

London was especially bad, and about Knightsbridge, in winter, the

traveller had to wade through deep mud. Wyatt's men entered

the city by this approach in the rebellion of 1554, and were called

the "draggle-tails" because of their wretched plight. The ways

were equally bad as far as Windsor, which, in the reign of

Elizabeth, is described by Pote, in his history of that town, as

being "not much past half a day's journeye removed from the

flourishing citie of London."

At a greater distance from the metropolis, the roads were

still worse. They were in many cases but rude tracks across

heaths and commons, as furrowed with deep ruts as ploughed fields;

and in winter to pass along one of them was like travelling in a

ditch. The attempts made by the adjoining occupiers to mend

them, were for the most part confined to throwing large stones into

the bigger holes to fill them up. It was easier to allow new

tracks to be made than to mend the old ones. The land of the

country was still mostly unenclosed, and it was possible, in fine

weather, to get from place to place, in one way or another, with the

help of a guide. In the absence of bridges, guides were

necessary to point out the safest fords as well as to pick out the

least miry tracks. The most frequented lines of roads were

struck out from time to time by the drivers of pack-horses, who, to

avoid the bogs and sloughs, were usually careful to keep along the

higher grounds; but, to prevent those horsemen who departed from the

beaten track being swallowed up in quagmires, beacons were erected

to warn them against the more dangerous places. [p.8]

In some of the older-settled districts of England, the old

roads are still to be traced in the hollow Ways or Lanes, which are

to be met with, in some places, eight and ten feet deep. They

were horse-tracks in summer, and rivulets in winter. By dint

of weather and travel, the earth was gradually worn into these deep

furrows, many of which, in Wilts, Somerset, and Devon, represent the

tracks of roads as old as, if not older than, the Conquest.

When the ridgeways of the earliest settlers on Dartmoor, above

alluded to, were abandoned, the tracks were formed through the

valleys, but the new roads were no better than the old ones.

They were narrow and deep, fitted only for a horse passing along

laden with its crooks, as so graphically described in the ballad of

"The Devonshire Lane." [p.9]

Similar roads existed until recently in the immediate

neighbourhood of Birmingham, now the centre of an immense traffic.

The sandy soil was sawn through, as it were, by generation after

generation of human feet, and by pack-horses, helped by the rains,

until in some places the tracks were as much as from twelve to

fourteen yards deep; one of these, partly filled up, retaining to

this day the name of Holloway Head. In the neighbourhood of

London there was also a Hollow way, which now gives its name to a

populous metropolitan parish. Hagbush Lane was another of such

roads. Before the formation of the Great North Road, it was

one of the principal bridle-paths leading from London to the

northern parts of England; but it was so narrow as barely to afford

passage for more than a single horseman, and so deep that the

rider's head was beneath the level of the ground on either side.

The roads of Sussex long preserved an infamous notoriety.

Chancellor Cowper, when a barrister on circuit, wrote to his wife in

1690, that "the Sussex ways are bad and ruinous beyond imagination.

I vow 'tis melancholy consideration that mankind will inhabit such a

heap of dirt for a poor livelihood. The country is a sink of

about fourteen miles broad, which receives all the water that falls

from two long ranges of hills on both sides of it, and not being

furnished with convenient draining, is kept moist and soft by the

water till the middle of a dry summer, which is only able to make it

tolerable to ride for a short time."

It was almost as difficult for old persons to get to church

in Sussex during winter as it was in the Lincoln Fens, where they

were rowed thither in boats. Fuller saw an old lady being

drawn to church in her own coach by the aid of six oxen. The

Sussex roads were indeed so bad as to pass into a by-word. A

contemporary writer says, that in travelling a slough of

extraordinary miryness, it used to be called "the Sussex bit of the

road;" and he satirically alleged that the reason why the Sussex

girls were so long-limbed was because of the tenacity of the mud in

that county; the practice of pulling the foot out of it "by the

strength of the ancle" tending to stretch the muscle and lengthen

the bone! [p.11]

But the roads in the immediate neighbourhood of London long

continued almost as bad as those in Sussex. Thus, when the

poet Cowley retired to Chertsey, in 1665, he wrote to his friend

Sprat to visit him, and, by way of encouragement, told him that he

might sleep the first night at Hampton town; thus occupying two days

in the performance of a journey of twenty-two miles in the immediate

neighbourhood of the metropolis. As late as 1736 we find Lord

Hervey, writing from Kensington, complaining that "the road between

this place and London is grown so infamously bad that we live here

in the same solitude as we would do if cast on a rock in the middle

of the ocean; and all the Londoners tell us that there is between

them and us an impassable gulf of mud."

Nor was the mud any respecter of persons; for we are informed

that the carriage of Queen Caroline could not, in bad weather, be

dragged from St. James's Palace to Kensington in less than two

hours, and occasionally the royal coach stuck fast in a rut, or was

even capsized in the mud. About the same time, the streets of

London themselves were little better, the kennel being still

permitted to flow in the middle of the road, which was paved with

round stones,—flag-stones for the convenience of pedestrians being

as yet unknown. In short, the streets in the towns and the

roads in the country were alike rude and wretched,—indicating a

degree of social stagnation and discomfort which it is now difficult

to estimate, and almost impossible to describe.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

EARLY MODES OF CONVEYANCE.

SUCH being the

ancient state of the roads, the only practicable modes of travelling

were on foot and on horseback. The poor walked and the rich

rode. Kings rode and Queens rode. Judges rode circuit in

jack-boots. Gentlemen rode and robbers rode. The Bar

sometimes walked and sometimes rode. Chaucer's ride to

Canterbury will be remembered as long as the English language lasts.

Hooker rode to London on a hard-paced nag, that he might be in time

to preach his first sermon at St. Paul's. Ladies rode on

pillions, holding on by the gentleman or the serving-man mounted

before.

Shakespeare incidentally describes the ancient style of

travelling among the humbler classes in his 'Henry IV.' [p.13]

The party, afterwards set upon by Falstaff and his companions, bound

from Rochester to London, were up by two in the morning, expecting

to perform the journey of thirty miles by close of day, and to get

to town "in time to go to bed with a candle." Two are

carriers, one of whom has "a gammon of bacon and two razes of

ginger, to be delivered as far as Charing Cross; the other has his

panniers full of turkeys. There is also a franklin of Kent,

and another, "a kind of auditor," probably a tax-collector, with

several more, forming in all a company of eight or ten, who travel

together for mutual protection. Their robbery on Gad's Hill,

as painted by Shakespeare, is but a picture, by no means

exaggerated, of the adventures and dangers of the road at the time

of which he wrote.

Distinguished personages sometimes rode in horse-litters; but

riding on horseback was generally preferred. Queen Elizabeth

made most of her journeys in this way, [p.14]

and when she went into the City she rode on a pillion behind her

Lord Chancellor. The Queen, however, was at length provided

with a coach, which must have been a very remarkable machine.

This royal vehicle is said to have been one of the first coaches

used in England, and it was introduced by the Queen's own coachman,

one Boomen, a Dutchman. It was little better than a cart

without springs, the body resting solid upon the axles. Taking

the bad roads and ill-paved streets into account, it must have been

an excessively painful means of conveyance. At one of the

first audiences which the Queen gave to the French ambassador in

1568, she feelingly described to him "the aching pains she was

suffering in consequence of having been knocked about in a coach

which had been driven a little too fast, only a few days before." [p.15-1]

Such coaches were at first only used on state occasions.

The roads, even in the immediate neighbourhood of London, were so

bad and so narrow that the vehicles could not be taken into the

country. But, as the roads became improved, the fashion of

using them spread. When the aristocracy removed from the City

to the western parts of the metropolis, they could be better

accommodated, and in course of time they became gradually adopted.

They were still, however, neither more nor less than waggons, and,

indeed, were called by that name; but wherever they went they

excited great wonder. It is related of "that valyant knyght

Sir Harry Sidney," that on a certain day in the year 1583 he entered

Shrewsbury in his waggon, "with his Trompeter blowynge, verey

joyfull to behold and see." [p.15-2]

From this time the use of coaches gradually spread, more

particularly amongst the nobility, superseding the horse-litters

which had till then been used for the conveyance of ladies and

others unable to bear the fatigue of riding on horseback. The

first carriages were heavy and lumbering: and upon on the execrable

roads of the time they went pitching over the stones and into the

ruts, with the pole dipping and rising like a ship in a rolling sea.

That they had no springs, is clear enough from the statement of

Taylor, the waterpoet—who deplored the introduction of carriages as

a national calamity—that in the paved streets of London men and

women were "tossed, tumbled, rumbled, and jumbled about in them."

Although the road from London to Dover, along the old Roman

Watling-street, was then one of the best in England, the French

household of Queen Henrietta, when they were sent forth from the

palace of Charles I., occupied four tedious days before they reached

Dover.

But it was only a few of the main roads leading from the

metropolis that were practicable for coaches; and on the occasion of

a royal progress, or the visit of a lord-lieutenant, there was a

general turn out of labourers and masons to mend the ways and render

the bridges at least temporarily secure. Of one of Queen

Elizabeth's journeys it is said:—"It was marvellous for ease and

expedition, for such is the perfect evenness of the new highway that

Her Majesty left the coach only once, while the hinds and the folk

of a base sort lifted it on with their poles."

Sussex long continued impracticable for coach travelling at

certain seasons. As late as 1708, Prince George of Denmark had

the greatest difficulty in making his way to Petworth to meet

Charles VI. of Spain. "The last nine miles of the way," says

the reporter, "cost us six hours to conquer them." One of the

couriers in attendance complained that during fourteen hours he

never once alighted, except when the coach overturned, or stuck in

the mud.

When the judges, usually old men and bad riders, took to

going the circuit in their coaches, juries were often kept waiting

until their lordships could be dug out of a bog or hauled out of a

slough by the aid of plough-horses. In the seventeenth

century, scarcely a Quarter Session passed without presentments from

the grand jury against certain districts on account of the bad state

of the roads, and many were the fines which the judges imposed upon

them as a set-off against their bruises and other damages while on

circuit.

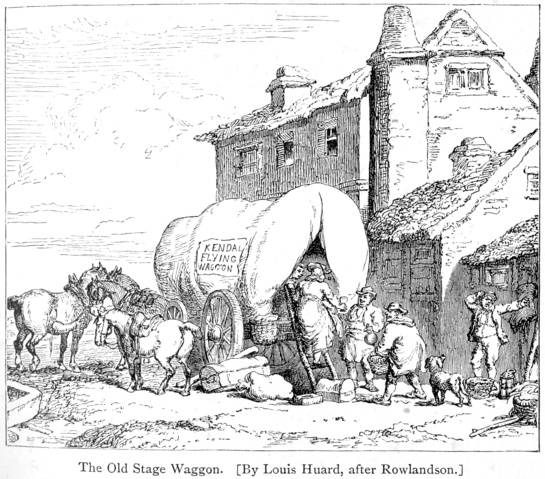

For a long time the roads continued barely practicable for

wheeled vehicles of the rudest sort, though Fynes Morison (writing

in the time of James I.) gives an account of "carryers, who have

long covered waggons, in which they carry passengers from place to

place; but this kind of journeying," he says, "is so tedious, by

reason they must take waggon very early and come very late to their

innes, that none but women and people of inferior condition travel

in this sort."

The waggons of which Morison wrote, made only from ten to

fifteen miles in a long summer's day; that is, supposing them not to

have broken down by pitching over the boulders laid along the road,

or stuck fast in a quagmire, when they had to wait for the arrival

of the next team of horses to help to drag them out. The

waggon, however, continued to be adopted as a popular mode of

travelling until late in the eighteenth century; and Hogarth's

picture illustrating the practice will be remembered, of the

cassocked parson on his lean horse, attending his daughter newly

alighted from the York waggon.

A curious description of the state of the Great North Road,

in the time of Charles II., is to be found in a tract published in

1675 by Thomas Mace, one of the clerks of Trinity College,

Cambridge. The writer there addressed himself to the King,

partly in prose and partly in verse, complaining greatly of the

"wayes, which are so grossly foul and bad;" and suggesting various

remedies. He pointed out that much ground "is now spoiled and

trampled down in all wide roads, where coaches and carts take

liberty to pick and chuse for their best advantages; besides, such

sprawling and straggling of coaches and carts utterly confound the

road in all wide places, so that it is not only unpleasurable, but

extreme perplexin and cumbersome both to themselves and all horse

travellers." It would thus appear that the country on either

side of the road was as yet entirely unenclosed.

But Mace's principal complaint was of the "innumerable

controversies, quarrellings, and disturbances" caused by the

packhorse-men, in their struggles as to which convoy should pass

along the cleaner parts of the road. From what he states, it

would seem that these "disturbances, daily committed by uncivil,

refractory, and rude Russian-like rake-shames, in contesting for the

way, too often proved mortal, and certainly were of very bad

consequences to many." He recommended a quick and prompt

punishment in all such cases. "No man," said he, "should be

pestered by giving the way (sometimes) to hundreds of pack-horses,

panniers, whifflers (i.e. paltry fellows), coaches, waggons,

wains, carts, or whatsoever others, which continually are very

grievous to weary and loaden travellers; but more especially near

the city and upon a market day, when, a man having travelled a long

and tedious journey, his horse well nigh spent, shall sometimes be

compelled to cross out of his way twenty times in one mile's riding,

by the irregularity and peevish crossness of such-like whifflers and

market women; yea, although their panniers be clearly empty, they

will stoutly contend for the way with weary travellers, be they

never so many, or almost of what quality soever." "Nay," said

he further, "I have often known many travellers, and myself very

often, to have been necessitated to stand stock still behind a

standing cart or waggon, on most beastly and unsufferable deep wet

wayes, to the great endangering of our horses, and neglect of

important business: nor durst we adventure to stirr (for most

imminent danger of those deep rutts, and unreasonable ridges) till

it has pleased Mister Carter to jog on, which we have taken very

kindly."

Mr. Mace's plan of road reform was not extravagant. He

mainly urged that only two good tracks should be maintained, and the

road be not allowed to spread out into as many as half-a-dozen very

bad ones, presenting high ridges and deep ruts, full of big stones,

and many quagmires. Breaking out into verse, he said—

"First let the wayes be regularly brought

To artificial form, and truly wrought;

So that we can suppose them firmly mended,

And in all parts the work well ended,

That not a stone's amiss; but all compleat,

All lying smooth, round, firm, and wondrous neat." |

After a good deal more in the same strain, he concluded—

|

There's only one thing yet worth

thinking on—

Which is, to put this work in execution." [p.20] |

But we shall find that more than a hundred years passed

before the roads throughout England were placed in a more

satisfactory state than they were in the time of Mr. Mace.

The introduction of stage-coaches about the middle of the

seventeenth century formed a new era in the history of travelling by

road. At first they were only a better sort of waggon, and

confined to the more practicable highways near London. Their

pace did not exceed four miles an hour, and the jolting of the

unfortunate passengers conveyed in them must have been very hard to

bear. It used to be said of their drivers that they were

"seldom sober, never civil, and always late."

The first mention of coaches for public accommodation is made

by Sir William Dugdale in his Diary, from which it appears that a

Coventry coach was on the road in 1659. But probably the first

coaches, or rather waggons, were run between London and Dover, as

one of the most practicable routes for the purpose. M.

Sobrière , a French man of letters, who landed at Dover on his way

to London in the time of Charles II., alludes to the existence of a

stage-coach, but it seems to have had no charms for him, as the

following passage will show: "That I might not," he says, "take post

or be obliged to use the stage-coach, I went from Dover to London in

a waggon. I was drawn by six horses, one before another, and

driven by a waggoner, who walked by the side of it. He was

clothed in black, and appointed in all things like another St.

George. He had a brave montrero on his head and was a merry

fellow, fancied he made a figure, and seemed mightily pleased with

himself."

Shortly after, coaches seem to have been running as far north

as Preston in Lancashire, as appears by a letter from one Edward

Parker to his father, dated November, 1663, in which he says, "I got

to London on Saturday last; but my journey was noe ways pleasant,

being forced to ride in the boote all the waye. Ye company yt

came up with mee were persons of greate quality, as knights and

ladyes. My journey's expense was 30s. This traval hath

soe indisposed nee, yt I am resolved never to ride up againe in ye

coatch." [p.22-1] These

vehicles must, however, have considerably increased, as we find a

popular agitation was got up against them. The Londoners

nicknamed them "hell-carts;" pamphlets were written recommending

their abolition; and attempts were even made to have them suppressed

by Act of Parliament.

Thoresby occasionally alludes to stage-coaches in his Diary,

speaking of one that ran between Hull and York in 1679, from which

latter place he had to proceed by Leeds in the usual way on

horseback. This Hull vehicle did not run in winter, because of

the state of the roads; stage-coaches being usually laid up in that

season like ships during Arctic frosts. [p.22-2]

Afterwards, when a coach was put on between York and Leeds, it

performed the journey of twenty-four miles in eight hours; [p.22-3]

but the road was so bad and dangerous that the travellers were

accustomed to get out and walk the greater part of the way.

Thoresby often waxes eloquent upon the subject of his

manifold deliverances from the dangers of travelling by coach.

He was especially thankful when he had passed the ferry over the

Trent in journeying between Leeds and London, having on several

occasions narrowly escaped drowning there. Once, on his

journey to London, some showers fell, which "raised the washes upon

the road near Ware to that height that passengers from London that

were upon that road swam, and a poor higgler was drowned, which

prevented me travelling for many hours; yet towards evening we

adventured with some country people, who conducted us over the

meadows, whereby we missed the deepest of the Wash at Cheshunt,

though we rode to the saddle-skirts for a considerable way, but got

safe to Waltham Cross, where we lodged." [p.23-1]

On another occasion Thoresby was detained four days at

Stamford by the state of the roads, and was only extricated from his

position by a company of fourteen members of the House of Commons

travelling towards London, who took him into their convoy, and set

out on their way southward attended by competent guides. When

the "waters were out," as the saying went, the country became

closed, the roads being simply impassable. During the Civil

Wars eight hundred horse were taken prisoners while sticking in the

mud. [p.23-2] When rain

fell, pedestrians, horsemen, and coaches alike came to a standstill

until the roads dried again and enabled the wayfarers to proceed.

Thus we read of two travellers stopped by the rains within a few

miles of Oxford, who found it impossible to accomplish their journey

in consequence of the waters that covered the country thereabout.

A curious account has been preserved of the journey of an

Irish Viceroy across North Wales towards Dublin in 1685. The

roads were so horrible that instead of the Viceroy being borne along

in his coach, the coach itself had to be borne after him the greater

part of the way. He was five hours in travelling between St.

Asaph and Conway, a distance of only fourteen miles. Between

Conway and Beaumaris he was forced to walk, while his wife was borne

along in a litter. The carriages were usually taken to pieces

at Conway and carried on the shoulders of stout Welsh peasants to be

embarked at the Straits of Menai.

The introduction of stage-coaches, like every other public

improvement, was at first regarded with prejudice, and had

considerable obloquy to encounter. In a curious book published

in 1673, entitled 'The Grand Concern of England Explained in several

Proposals to Parliament,' [p.24]

stage-coaches and caravans were denounced as among the greatest

evils that had happened to the kingdom, being alike mischievous to

the public, destructive to trade, and prejudicial to the landed

interest. It was alleged that travelling by coach was

calculated to destroy the breed of horses, and make men careless of

good horsemanship,—that it hindered the training of watermen and

seamen, and interfered with the public resources. The reasons

given are curious. It was said that those who were accustomed

to travel in coaches became weary and listless when they rode a few

miles, and were unwilling to get on horseback—"not being able to

endure frost, snow, or rain, or to lodge in the fields;" that

to save their clothes and keep themselves clean and dry, people rode

in coaches, and thus contracted an idle habit of body; that this was

ruinous to trade, for that "most gentlemen, before they travelled in

coaches, used to ride with swords, belts, pistols, holsters,

pormanteaus, and hat-cases, which, in these coaches, they have

little or no occasion for: for when they rode on horseback, they

rode in one suit and carried another to wear when they came to their

journey's end, or lay by the way; but in coaches a silk suit and an

Indian gown, with a sash, silk stockings, and beaver-hats, men ride

in, and carry no other with them, because they escape the wet and

dirt, which on horseback they cannot avoid; whereas, in two or three

journeys on horseback, these clothes and hats were wont to be

spoiled; which done, they were forced to have new very often, and

that increased the consumption of the manufactures and the

employment of the manufacturers; which travelling in coaches doth in

way do." [p.25]

The writer of the same protest against coaches gives some

idea of the extent of travelling by them in those days; for to show

the gigantic nature of the evil he was contending against, he

averred that between London and the three principal towns of York,

Chester, and Exeter, not fewer than eighteen persons, making the

journey in five days, travelled by them weekly (the coaches running

thrice in the week), and a like number back; "which come, in the

whole, to eighteen hundred and seventy-two in the year."

Another great nuisance, the writer alleged, which flowed from the

establishment of the stagecoaches, was, that not only did the

gentlemen from the country come to London in them oftener than they

need, but their ladies either came with them or quickly followed

them. "And when they are there they must be in the mode, have

all the new fashions, buy all their clothes there, and go to plays,

balls, and treats, where they get such a habit of jollity and a love

to gaiety and pleasure, that nothing afterwards in the country will

serve them, if ever they should fix their minds to live there again;

but they must have all from London, whatever it costs."

Then there were the grievous discomforts of stage-coach

travelling, to be set against the more noble method of travelling by

horseback, as of yore. "What advantage is it to men's health,"

says the writer, waxing wroth, "to be called out of their beds into

these coaches, an hour before day in the morning; to be hurried in

them from place to place, till one hour, two, or three within night;

insomuch that, after sitting all day in the summertime stifled with

heat and choked with dust, or in the winter-time starving and

freezing with cold or choked with filthy fogs, they are often

brought into their inns by torchlight, when it is too late to sit up

to get a supper; and next morning they are forced into the coach so

early that they can get no breakfast? What addition is this to

men's health or business to ride all day with strangers, oftentimes

sick, ancient, diseased persons, or young children crying; to whose

humours they are obliged to be subject, forced to bear with, and

many times are poisoned with their nasty scents and crippled by the

crowd of boxes and bundles? Is it for a man's health to travel

with tired jades, to be laid fast in the foul ways and forced to

wade up to the knees in mire; afterwards sit in the cold till teams

of horses can be sent to pull the coach out? Is it for their

health to travel in rotten coaches and to have their tackle, perch,

or axle-tree broken, and then to wait three or four hours (sometimes

half a day) to have them mended, and then to travel all night to

make good their stage? Is it for a man's pleasure, or

advantageous to his health and business, to travel with a mixed

company that he knows not how to converse with; to be affronted by

the rudeness of a surly, dogged, cursing, ill-natured coachman;

necessitated to lodge or bait at the worst inn on the road, where

there is no accommodation fit for gentlemen; and this merely because

the owners of the inns and the coachmen are agreed together to cheat

the guests?" Hence the writer loudly called for the immediate

suppression of stage-coaches as a great nuisance and crying evil.

Travelling by coach was in early times a very deliberate

affair. Time was of less consequence than safety, and coaches

were advertised to start "God willing," and "about" such and such an

hour "as shall seem good" to the majority of the passengers.

The difference of a day in the journey from London to York was a

small matter, and Thoresby was even accustomed to leave the coach

and go in search of fossil shells in the fields on either side the

road while making the journey between the two places. The long

coach "put up" at sun-down, and "slept on the road." Whether

the coach was to proceed or to stop at some favourite inn, was

determined by the vote of the passengers, who usually appointed a

chairman at the beginning of the journey.

In 1700, York was a week distant from London, and Tunbridge

Wells, now reached in an hour, was two days. Salisbury and

Oxford were also each a two days' journey, Dover was three days, and

Exeter five. The Fly coach from London to Exeter slept

at the latter place the fifth night from town; the coach proceeding

next morning to Axminster, where it breakfasted, and there a woman

barber "shaved the coach." [p.28]

Between London and Edinburgh, as late as 1763, a fortnight was

consumed, the coach only starting once a month. [p.29]

The risks of breaks-down in driving over the execrable roads may be

inferred from the circumstance that every coach carried with it a

box of carpenter's tools, and the hatchets were occasionally used in

lopping off the branches of trees overhanging the road and

obstructing the travellers' progress.

Some fastidious persons, disliking the slow travelling, as

well as the promiscuous company which they ran the risk of

encountering in the stage, were accustomed to advertise for partners

in a postchaise, to share the charges and lessen the dangers of the

road; and, indeed, to a sensitive person anything must have been

preferable to the misery of travelling by the Canterbury stage, as

thus described by a contemporary writer:—

|

"On both sides squeez'd, how highly was I

blest,

Between two plump old women to be presst!

A corp'ral fierce, a nurse, a child that cry'd,

And a fat landlord, filled the other side.

Scarce dawns the morning ere the cumbrous load

Rolls roughly rumbling o'er the rugged road:

One old wife coughs and wheezes in my ears,

Loud scolds the other, and the soldier swears;

Sour unconcocted breath escapes 'mine host,'

The sick'ning child returns his milk and toast!" |

When Samuel Johnson was taken by his mother to London in

1712, to have him touched by Queen Anne for "the evil," he

relates,—"We went in the stage-coach and returned in the waggon, as

my mother said, because my cough was violent; but the hope of saving

a few shillings was no slight motive . . . She sewed two guineas in

her petticoat lest she should be robbed. . . . We were troublesome

to the passengers; but to suffer such inconveniences in the

stage-coach was common in those days to persons in much higher

rank."

Mr. Pennant has left us the following account of his journey

in the Chester stage to London in 1739-40: "The first day," says he,

"with much labour, we got from Chester to Whitchurch, twenty miles;

the second day to the 'Welsh Harp;' the third, to Coventry; the

fourth, to Northampton; the fifth, to Dunstable; and, as a wondrous

effort, on the last, to London, before the commencement of night.

The strain and labour of six good horses, sometimes eight, drew us

through the sloughs of Mireden and many other places. We were

constantly out two hours before day, and as late at night, and in

the depth of winter proportionally later. The single

gentlemen, then a hardy race, equipped in jack-boots and trowsers,

up to their middle, rode post through thick and thin, and, guarded

against the mire, defied the frequent stumble and fall, arose and

pursued their journey with alacrity; while, in these days, their

enervated posterity sleep away their rapid journeys in easy chaises,

fitted for the conveyance of the soft inhabitants of Sybaris."

No wonder, therefore, that a great deal of the travelling of

the country continued to be performed on horseback, this being by

far the pleasantest as well as most expeditious mode of journeying.

On his marriage-day, Dr. Johnson rode from Birmingham to Derby with

his Tetty, taking the opportunity of the journey to give his bride

her first lesson in marital discipline. At a later period

James Watt rode from Glasgow to London, when

proceeding thither to learn the art of mathematical

instrument-making. And it was a cheap and pleasant method of

travelling when the weather was fine. The usual practice was,

to buy a horse at the beginning of such a journey, and to sell the

animal at the end of it. Dr. Skene, of Aberdeen, travelled

from London to Edinburgh in 1753, being nineteen days on the road,

the whole expenses of the journey amounting to only four guineas.

The mare on which he rode, cost him eight guineas in London, and he

sold her for the same price on his arrival in Edinburgh.

Nearly all the commercial gentlemen rode their own horses,

carrying their samples and luggage in two bags at the saddle-bow;

and hence their appellation of Riders or Bagmen. For safety's

sake, they usually journeyed in company; for the dangers of

travelling were not confined merely to the ruggedness of the roads.

The highways were infested by troops of robbers and vagabonds who

lived by plunder. Turpin and Bradshaw beset the Great North

Road; Duval, Macheath, Maclean, and hundreds of notorious highwaymen

infested Hounslow Heath, Finchley Common, Shooter's Hill, and all

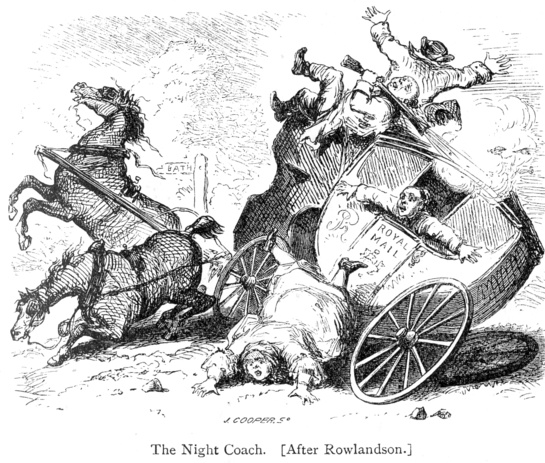

the approaches to the metropolis. A very common sight then,

was a gibbet erected by the roadside, with the skeleton of some

malefactor hanging from it in chains; and "Hangman's-lanes" were

especially numerous in the neighbourhood of London. [p.32]

It was considered most unsafe to travel after dark, and when the

first "night coach" was started, the risk was thought too great, and

it was not patronised.

Travellers armed themselves on setting out upon a journey as

if they were going to battle, and a blunderbuss was considered as

indispensable for a coachman as a whip. Dorsetshire and

Hampshire, like most other counties, were beset with gangs of

highwaymen; and when the Grand Duke Cosmo set out from Dorchester to

travel to London in 1669, he was "convoyed by a great many

horse-soldiers belonging to the militia of the county, to secure him

from robbers." [p.33-1]

Thoresby, in his Diary, alludes with awe to his having passed safely

"the great common where Sir Ralph Wharton slew the highwayman," and

he also makes special mention of Stonegate Hole, "a notorious

robbing place" near Grantham. Like every other traveller, that

good man carried loaded pistols in his bags, and on one occasion he

was thrown into great consternation near Topcliffe, in Yorkshire, on

missing them, believing that they had been abstracted by some

designing rogues at the inn where he had last slept. [p.33-2]

No wonder that, before setting out on a journey in those days, men

were accustomed to make their wills.

When Mrs. Calderwood, of Coltness, travelled from Edinburgh

to London in 1756, she relates in her Diary that she travelled in

her own postchaise, attended by John Rattray, her stout serving man,

on horseback, with pistols at his holsters, and a good broad sword

by his side. The lady had also with her in the carriage a case

of pistols, for use upon an emergency. Robberies were then of

frequent occurrence in the neighbourhood of Bawtry, in Yorkshire;

and one day a suspicious-looking character, whom they took to be a

highwayman, made his appearance; but "John Rattray talking about

powder and ball to the postboy, and showing his whanger, the fellow

made off." Mrs. Calderwood started from Edinburgh on the 3rd

of June, when the roads were dry and the weather was fine, and she

reached London on the evening of the l0th, which was considered a

rapid journey in those days.

The danger, however, from footpads and highwaymen was not

greatest in remote country places, but in and about the metropolis

itself. The proprietors of Bellsize House and gardens, in the

Hampstead-road, then one of the principal places of amusement, had

the way to London patrolled during the season by twelve "lusty

fellows;" and Sadler's Wells, Vauxhall, and Ranelagh advertised

similar advantages. Foot passengers proceeding towards

Kensington and Paddington in the evening, would wait until a

sufficiently numerous band had collected to set footpads at

defiance, and then they started in company at known intervals, of

which a bell gave due warning. Carriages were stopped in broad

daylight in Hyde Park, and even in Piccadilly itself, and pistols

presented at the breasts of fashionable people, who were called upon

to deliver up their purses. Horace Walpole relates a number of

curious instances of this sort, he himself having been robbed in

broad day, with Lord Eglinton, Sir Thomas Robinson, Lady Albemarle,

and many more. A curious robbery of the Portsmouth mail, in

1757, illustrates the imperfect postal communication of the period.

The boy who carried the post had dismounted at Hammersmith, about

three miles from Hyde Park Corner, and called for beer, when some

thieves took the opportunity of cutting the mail-bag from off the

horse's crupper and got away undiscovered!

The means adopted for the transport of merchandise were as

tedious and difficult as those ordinarily employed for the

conveyance of passengers. Corn and wool were sent to market on

horses' backs, [p.35] manure was

carried to the fields in panniers, and fuel was conveyed from the

moss or the forest in the same way. During the winter months,

the markets were inaccessible; and while in some localities the

supplies of food were distressingly deficient, in others the

superabundance actually rotted from the impossibility of consuming

it or of transporting it to places where it was needed. The

little coal used in the southern counties was principally sea-borne,

though pack-horses occasionally carried coal inland for the supply

of the blacksmiths' forges. When Wollaton Hall was built by

John of Padua for Sir Francis Willoughby in 1580, the stone was all

brought on horses' backs from Ancaster, in Lincolnshire, thirty-five

miles distant, and they loaded back with coal, which was taken in

exchange for the stone.

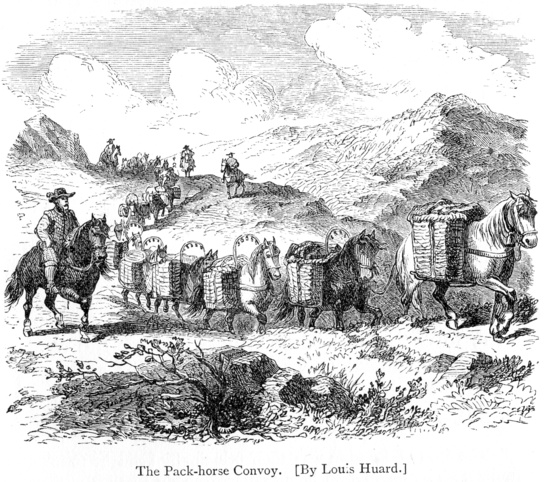

The little trade which existed between one part of the

kingdom and another was carried on by means of pack-horses, along

roads little better than bridle-paths. These horses

travelled in lines, with the bales or panniers strapped across their

backs. The foremost horse bore a bell or a collar of bells,

and was hence called the "bell-horse." He was selected because

of his sagacity; and by the tinkling of the bells he carried, the

movements of his followers were regulated. The bells also gave

notice of the approach of the convoy to those who might be advancing

from the opposite direction. This was a matter of some

importance, as in many parts of the path there was not room for two

loaded horses to pass each other, and quarrels and fights between

the drivers of the pack-horse trains were frequent as to which of

the meeting convoys was to pass down into the dirt and allow the

other to pass along the bridleway. The pack-horses not only

carried merchandise but passengers, and at certain times scholars

proceeding to and from Oxford and Cambridge. When Smollett

went from Glasgow to London, he travelled partly on packhorse,

partly by waggon, and partly on foot; and the adventures which he

described as having befallen Roderick Random are supposed to have

been drawn in a great measure from his own experiences during the

journey.

A cross-country merchandise traffic gradually sprang up

between the northern counties, since become pre-eminently the

manufacturing districts of England; and long lines of pack-horses

laden with bales of wool and cotton traversed the hill ranges which

divide Yorkshire from Lancashire. Whitaker says that as late

as 1753 the roads near Leeds consisted of a narrow hollow way little

wider than a ditch, barely allowing of the passage of a vehicle

drawn in a single line; this deep narrow road being flanked by an

elevated causeway covered with flags or boulder stones. When

travellers encountered each other on this narrow track, they often

tried to wear out each other's patience rather than descend into the

dirt alongside. The raw wool and bale goods of the district

were nearly all carried along these flagged ways on the backs of

single horses; and it is difficult to imagine the delay, the toil,

and the perils by which the conduct of the traffic was attended.

On horseback before daybreak and long after nightfall, these hardy

sons of trade pursued their object with the spirit and intrepidity

of foxhunters; and the boldest of their country neighbours had no

reason to despise either their horsemanship or their courage. [p.38]

The Manchester trade was carried on in the same way. The

chapmen used to keep gangs of pack-horses, which accompanied them to

all the principal towns, bearing their goods in packs, which they

sold to their customers, bringing back sheep's wool and other raw

materials of manufacture.

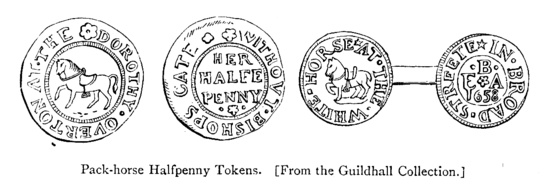

The only records of this long-superseded mode of

communication are now to be traced on the signboards of wayside

public-houses. Many of the old roads still exist in Yorkshire

and Lancashire; but all that remains of the former traffic is the

pack-horse still painted on village sign-boards—things as retentive

of odd bygone facts as the picture-writing of the ancient Mexicans.

[p.39]

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS INFLUENCED

BY THE STATE OF THE ROADS.

WHILE the road

communications of the country remained thus imperfect, the people of

one part of England knew next to nothing of the other. When a

shower of rain had the effect of rendering the highways impassable,

even horsemen were cautious in venturing far from home. But

only a very limited number of persons could then afford to travel on

horseback. The labouring people journeyed on foot, while the

middle class used the waggon or the coach. But the amount of

intercourse between the people of different districts—then

exceedingly limited at all times—was, in a country so wet as

England, necessarily suspended for all classes during the greater

part of the year.

The imperfect communication existing between districts had

the effect of perpetuating numerous local dialects, local

prejudices, and local customs, which survive to a certain extent to

this day; though they are rapidly disappearing, to the regret of

many, under the influence of improved facilities for travelling.

Every village had its witches, sometimes of different sorts, and

there was scarcely an old house but had its white lady or moaning

old man with a long beard. There were ghosts in the fens which

walked on stilts, while the sprites of the hill country rode on

flashes of fire. But the village witches and local ghosts have

long since disappeared, excepting perhaps in a few of the less

penetrable districts, where they may still survive.

It is curious to find that down even to the beginning of the

seventeenth century, the inhabitants of the southern districts of

the island regarded those of the north as a kind of ogres.

Lancashire was supposed to be almost impenetrable—as indeed it was

to a considerable extent,—and inhabited by a half-savage race.

Camden vaguely described it, previous to his visit in 1607, as that

part of the country "lying beyond the mountains towards the Western

Ocean." He acknowledged that he approached the Lancashire

people "with a kind of dread," but determined at length "to run the

hazard of the attempt," trusting in the Divine assistance.

Camden was exposed to still greater risks in his survey of

Cumberland. When he went into that county for the purpose of

exploring the remains of antiquity it contained for the purposes of

his great work, he travelled along the line of the Roman Wall as far

as Thirlwall castle, near Haltwhistle; but there the limits of

civilisation and security ended; for such was the wildness of the

country and of its lawless inhabitants beyond, that he was obliged

to desist from his pilgrimage, and leave the most important and

interesting objects of his journey unexplored.

About a century later, in 1700, the Rev. Mr. Brome, rector of

Cheriton in Kent, entered upon a series of travels in England as if

it had been a newly-discovered country. He set out in spring

so soon as the roads had become passable. His friends convoyed

him on the first stage of his journey, and left him, commending him

to the Divine protection. He was, however, careful to employ

guides to conduct him from one place to another, and in the course

of his three years' travels he saw many new and wonderful things.

He was under the necessity of suspending his travels when the winter

or wet weather set in, and to lay up, like an arctic voyager, for

several months, until the spring came round again. Mr. Brome

passed through Northumberland into Scotland, then down the western

side of the island towards Devonshire, where he found the farmers

gathering in their corn on horse-back, the roads being so narrow

that it was impossible for them to use waggons. He desired to

travel into Cornwall, the boundaries of which he reached, but was

prevented proceeding farther by the rains, and accordingly he made

the best of his way home. [p.42]

The vicar of Cheriton was considered a wonderful man in his

day,—almost as adventurous as we should now regard a traveller in

Arabia. Twenty miles of slough, or an unbridged river between

two parishes, were greater impediments to intercourse than the

Atlantic Ocean now is between England and America.

Considerable towns situated in the same county, were then more

widely separated, for practical purposes, than London and Glasgow

are at the present day. There were many districts which

travellers never visited, and where the appearance of a stranger

produced as great an excitement as the arrival of a white man in an

African village. [p.43]

The author of 'Adam Bede' has given us a poet's picture of

the leisure of last century, which has "gone where the

spinning-wheels are gone, and the pack-horses, and the slow waggons,

and the pedlars who brought bargains to the door on sunny

afternoons." Old Leisure "lived chiefly in the country, among

pleasant seats and homesteads, and was fond of sauntering by the

fruit-tree walls, and scenting the apricots when they were warmed by

the morning sunshine, or sheltering himself under the orchard boughs

at noon, when the summer pears were falling." But this picture

has also its obverse side. Whole generations then lived a

monotonous, ignorant, prejudiced, and humdrum life. They had

no enterprise, no energy, little industry, and were content to die

where they were born. The seclusion in which they were

compelled to live, produced a picturesqueness of manners which is

pleasant to look back upon, now that it is a thing of the past; but

it was also accompanied with a degree of grossness and brutality

much less pleasant to regard, and of which the occasional popular

amusements of bull-running, cock-fighting, cock-throwing, the

saturnalia of Plough-Monday, and such like, were the fitting

exponents.

People then knew little except of their own narrow district.

The world beyond was as good as closed against them. Almost

the only intelligence of general affairs which reached them was

communicated by pedlars and packmen, who were accustomed to retail

to their customers the news of the day with their wares; or, at

most, a newsletter from London, after it had been read nearly to

pieces at the great house of the district, would find its way to the

village, and its driblets of information would thus become diffused

among the little community. Matters of public interest were

long in becoming known in the remoter districts of the country.

Macaulay relates that the death of Queen Elizabeth was not heard of

in some parts of Devon until the courtiers of her successor had

ceased to wear mourning for her. The news of Cromwell's being

made Protector only reached Bridgewater nineteen days after the

event, when the bells were set a-ringing; and the churches in the

Orkneys continued to put up the usual prayers for James II. three

months after he had taken up his abode at St. Germains.

There were then no shops in the smaller towns or villages,

and comparatively few in the larger; and these were badly furnished

with articles for general use. The country people were

irregularly supplied by hawkers, who sometimes bore their whole

stock upon their back, or occasionally on that of their pack-horses.

Pots, pans, and household utensils were sold from door to door.

Until a comparatively recent period, the whole of the Pottery-ware

manufactured in Staffordshire was hawked about and disposed of in

this way. The pedlars carried frames resembling camp-stools,

on which they were accustomed to display their wares when the

opportunity occurred for showing them to advantage. The

articles which they sold were chiefly of a fanciful kind—ribbons,

laces, and female finery; the housewives' great reliance for the

supply of general clothing in those days being on domestic industry.

Every autumn, the mistress of the household was accustomed to

lay in a store of articles sufficient to serve for the entire

winter. It was like laying in a stock of provisions and

clothing for a siege during the time that the roads were closed.

The greater part of the meat required for winter's use was killed

and salted down at Martinmas, while stockfish and baconed herrings

were provided for Lent. Scatcherd says that in his district

the clothiers united in groups of three or four, and at the Leeds

winter fair they would purchase an ox, which, having divided, they

salted and hung the pieces for their winter's food. [p.45]

There was also the winter's stock of firewood to be provided, and

the rushes with which to strew the floors—carpets being a

comparatively modern invention; besides, there was the store of

wheat and barley for bread, the malt for ale, the honey for

sweetening (then used for sugar), the salt, the spiceries, and the

savoury herbs so much employed in the ancient cookery. When

the stores were laid in, the housewife was in a position to bid

defiance to bad roads for six months to come. This was the

case of the well-to-do; but the poorer classes, who could not lay in

a store for winter, were often very badly off both for food and

firing, and in many hard seasons they literally starved. But

charity was active in those days, and many a poor man's store was

eked out by his wealthier neighbour.

When the household supply was thus laid in, the mistress,

with her daughters and servants, sat down to their distaffs and

spinning-wheels; for the manufacture of the family clothing was

usually the work of the winter months. The fabrics then worn

were almost entirely of wool, silk and cotton being scarcely known.

The wool, when not grown on the farm, was purchased in a raw state,

and was carded, spun, dyed, and in many cases woven at home: so also

with the linen clothing, which, until quite a recent date, was

entirely the produce of female fingers and household

spinning-wheels. This kind of work occupied the winter months,

occasionally alternated with knitting, embroidery, and tapestry

work. Many of our country houses continue to bear witness to

the steady industry of the ladies of even the highest ranks in those

times, in the fine tapestry hangings with which the walls of many of

the older rooms in such mansions are covered.

Among the humbler classes, the same winter's work went on.

The women sat round log fires knitting, plaiting, and spinning by

fire-light, even in the daytime. Glass had not yet come into

general use, and the openings in the wall which in summer-time

served for windows, had necessarily to be shut close with boards to

keep out the cold, though at the same time they shut out the light.

The chimney, usually of lath and plaster, ending overhead in a cone

and funnel for the smoke, was so roomy in old cottages as to

accommodate almost the whole family sitting around the fire of logs

piled in the reredosse in the middle, and there they carried on

their winter's work.

Such was the domestic occupation of women in the rural

districts in olden times; and it may perhaps be questioned whether

the revolution in our social system, which has taken out of their

hands so many branches of household manufacture and useful domestic

employment, be an altogether unmixed blessing.

Winter at an end, and the roads once more available for

travelling, the Fair of the locality was looked forward to with

interest. Fairs were among the most important institutions of

past times, and were rendered necessary by the imperfect road

communications. The right of holding them was regarded as a

valuable privilege, conceded by the sovereign to the lords of the

manors, who adopted all manner of devices to draw crowds to their

markets. They were usually held at the entrances to valleys

closed against locomotion during winter, or in the middle of rich

grazing districts, or, more frequently, in the neighbourhood of

famous cathedrals or churches frequented by flocks of pilgrims.

The devotion of the people being turned to account, many of the

fairs were held on Sundays in the churchyards; and almost in every

parish a market was instituted on the day on which the parishioners

were called together to do honour to their patron saint.

The local fair, which was usually held at the beginning or

end of winter, often at both times, became the great festival as

well as market of the district; and the business as well as the

gaiety of the neighbourhood usually centred on such occasions.

High courts were held by the Bishop or Lord of the Manor, to

accommodate which special buildings were erected, used only at fair

time. Among the fairs of the first class in England were

Winchester, St. Botolph's Town (Boston), and St. Ives. We find

the great London merchants travelling thither in caravans, bearing

with them all manner of goods, and bringing back the wool purchased

by them in exchange.

Winchester Great Fair attracted merchants from all parts of

Europe. It was held on the hill of St. Giles, and was divided

into streets of booths, named after the merchants of the different

countries who exposed their wares in them. "The passes through

the great woody districts, which English merchants coming from

London and the West would be compelled to traverse, were on this

occasion carefully guarded by mounted 'serjeants-at -arms,' since

the wealth which was being conveyed to St. Giles's-hill attracted

bands of outlaws from all parts of the country." [p.48]

Weyhill Fair, near Andover, was another of the great fairs in the

same district, which was to the West country agriculturists and

clothiers what Winchester St. Giles's Fair was to the general

merchants.

The principal fair in the northern districts was that of St.

Botolph's Town (Boston), which was resorted to by people from great

distances to buy and sell commodities of various kinds. Thus

we find, from the 'Compotus' of Bolton Priory, [p.49]

that the monks of that house sent their wool to St. Botolph's Fair

to be sold, though it was a good hundred miles distant; buying in

return their winter supply of groceries, spiceries, and other

necessary articles. That fair, too, was often beset by

robbers, and on one occasion a strong party of them, under the

disguise of monks, attacked and robbed certain booths, setting fire

to the rest; and such was the amount of destroyed wealth, that it is

said the veins of molten gold and silver ran along the streets.

The concourse of persons attending these fairs was immense.

The nobility and gentry, the heads of the religious houses, the

yeomanry and the commons, resorted to them to buy and sell all

manner of agricultural produce. The farmers there sold their

wool and cattle, and hired their servants; while their wives

disposed of the surplus produce of their winter's industry, and

bought their cutlery, bijouterie, and more tasteful articles of

apparel. There were caterers there for all customers; and

stuffs and wares were offered for sale from all countries. And

in the wake of this business part of the fair there invariably

followed a crowd of ministers to the popular tastes—quack doctors

and merry andrews, jugglers and minstrels, singlestick players,

grinners through horse-collars, and sportmakers of every kind.

Smaller fairs were held in most districts for similar

purposes of exchange. At these the staples of the locality

were sold and servants usually hired. Many were for special

purposes—cattle fairs, leather fairs, cloth fairs, bonnet fairs,

fruit fairs. Scatcherd says that less than a century ago a

large fair was held between Huddersfield and Leeds, in a field still

called Fairstead, near Birstal, which used to be a great mart for

fruit, onions, and such like; and that the clothiers resorted

thither from all the country round to purchase the articles, which

were stowed away n barns, and sold at booths by lamplight in the

morning. [p.50]

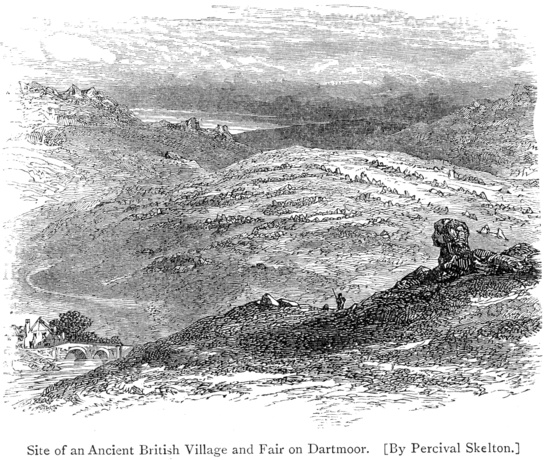

Even Dartmoor had its fair, on the site of an ancient British

village or temple near Merivale Bridge, testifying to its great

antiquity; for it is surprising how an ancient fair lingers about

the place on which it has been accustomed to be held, long after the

necessity for it has ceased. The site of this old fair at

Merivale Bridge is the more curious, as in its immediate

neighbourhood, on the road between Two Bridges and Tavistock, is

found the singular-looking granite rock, bearing so remarkable a

resemblance to the Egyptian sphynx, in a mutilated state. It

is of similarly colossal proportions, and stands in a district

almost as lonely as that in which the Egyptian sphynx looks forth

over the sands of the Memphean Desert. [p.51]

The last occasion on which the fair was held in this secluded

spot was in the year 1625, when the plague raged at Tavistock; and

there is a part of the ground, situated amidst a line of pillars

marking a stone avenue—a characteristic feature of the ancient

aboriginal worship which is to this day pointed out and called by

the name of the "Potatoe market."

But the glory of the great fairs has long since departed.

They declined with the extension of turnpikes, and railroads gave

them their deathblow. Shops now exist in every little town and

village, drawing their supplies regularly by road and canal from the

most distant parts. St. Bartholomew, the great fair of London,

[p.52] and Donnybrook, the great

fair of Dublin, have been suppressed as nuisances; and nearly all

that remains of the dead but long potent institution of the Fair, is

the occasional exhibition at periodic times in country places, of

pig-faced ladies, dwarfs, giants, double-bodied calves, and

such-like wonders, amidst a blatant clangour of drums, gongs, and

cymbals. Like the sign of the Pack-Horse over the village inn

door, the modern village fair, of which the principal article of

merchandise is gingerbread-nuts, is but the vestige of a state of

things that has long since passed away.

There were, however, remote and almost impenetrable districts

which long resisted modern inroads. Of such was Dartmoor,

which we have already more than once referred to. The

difficulties of road-engineering in that quarter, as well as the

sterility of a large proportion of the moor, had the effect of

preventing its becoming opened up to modern traffic; and it is

accordingly curious to find how much of its old manners, customs,

traditions, and language has been preserved. It looks like a

piece of England of the Middle Ages, left behind on the march.

Witches still hold their sway on Dartmoor, where there exist no less

than three distinct kinds—white, black, and grey, [p.53]—and

there are still professors of witchcraft, male as well as female, in

most of the villages.

As might be expected, the pack-horses held their ground in

Dartmoor the longest, and in some parts of North Devon they are not

yet extinct. When our artist was in the neighbourhood,

sketching the ancient bridge on the moor and the site of the old

fair, a farmer said to him, "I well remember the train of

pack-horses and the effect of their jingling bells on the silence of

Dartmoor. My grandfather, a respectable farmer in the north of

Devon, was the first to use a 'butt' (a square box without wheels,

dragged by a horse) to carry manure to field; he was also the first

man in the district to use an umbrella, which on Sundays he hung in

the church-porch, an object of curiosity to the villagers." We

are also informed by a gentleman who resided for some time at South

Brent, on the borders of the Moor, that the introduction of the

first cart in that district is remembered by many now living, the

bridges having been shortly afterwards widened to accommodate the

wheeled vehicles.

The primitive features of this secluded district are perhaps

best represented by the interesting little town of Chagford,

situated in the valley of the North Teign, an ancient stannary and

market town backed by a wide stretch of moor. The houses of

the place are built of moor stone—grey, venerable-looking, and

substantial—some with projecting porch and parvise room over, and

granite-mullioned windows; the ancient church, built of granite,

with a stout old steeple of the same material, its embattled porch

and granite-groined vault springing from low columns with

Norman-looking capitals, forming the sturdy centre of this ancient

town clump. |