|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER II.

LANGHOLM—TELFORD LEARNS THE TRADE

OF A STONEMASON.

THE time arrived

when young Telford must be put to some regular calling. Was he

to be a shepherd like his father and his uncle, or was he to be a

farm-labourer, or put apprentice to a trade? There was not

much choice; but at length it was determined to bind him to a

stonemason. In Eskdale that trade was for the most part

confined to the building of drystone walls, and there was very

little more art employed in it than an ordinarily neat-handed

labourer could manage. It was eventually decided to send the

youth—and he was now a strong lad of about fifteen—to a mason at

Lochmaben, a small town across the hills to the westward, where a

little more building and of a better sort—such as of farmhouses,

barns, and road-bridges—was carried on than in his own immediate

neighbourhood. There he remained only a few months; for his

master using him badly, the high-spirited youth would not brook it,

and ran away, taking refuge with his mother at The Crooks, very much

to her dismay.

What was now to be done with Tom? He was willing to do

anything or go anywhere rather than back to his Lochmaben master.

In this emergency his cousin Thomas Jackson, the factor or

land-steward at Wester Hall, offered to do what he could to induce

Andrew Thomson, a small mason at Langholm, to take Telford for the

remainder of his apprenticeship; and to him he went accordingly.

The business carried on by his new master was of a very humble sort.

Telford, in his autobiography, states that most of the farmers'

houses in the district then consisted of "one storey of mud walls,

or rubble stones bedded in clay, and thatched with straw, rushes, or

heather; the floors being of earth, and the fire in the middle,

having a plastered creel chimney for the escape of the smoke; while,

instead of windows, small openings in the thick mud walls admitted a

scanty light." The farm-buildings were of a similarly wretched

description.

The principal owner of the landed property in the

neighbourhood was the Duke of Buccleugh. Shortly after the

young Duke Henry succeeded to the title and estates, in 1767, he

introduced considerable improvements in the farmers' houses and

farm-steadings, and the peasants' dwellings, as well as in the roads

throughout Eskdale. Thus a demand sprang up for masons'

labour, and Telford's master had no want of regular employment for

his hands. Telford profited by the experience which this

increase in the building operations of the neighbourhood gave him;

being employed in raising rough walls and farm enclosures, as well

as in erecting bridges across rivers wherever regular roads for

wheel carriages were substituted for the horse-tracks formerly in

use.

During the greater part of his apprenticeship Telford lived

in the little town of Langholm, taking frequent opportunities of

visiting his mother at The Crooks on Saturday evenings, and

accompanying her to the parish church of Westerkirk on Sundays.

Langholm was then a very poor place, being no better in that respect

than the district that surrounded it. It consisted chiefly of

mud hovels, covered with thatch—the principal building in it being

the Tolbooth, a stone and lime structure, the upper part of which

was used as a justice-hall and the lower part as a gaol. There

were, however, a few good houses in the little town, occupied by

people of the better class, and in one of these lived an elderly

lady, Miss Pasley, one of the family of the Pasleys of Craig.

As the town was so small that everybody in it knew everybody else,

the ruddy-checked, laughing mason's apprentice soon became generally

known to all the townspeople, and amongst others to Miss Pasley.

When she heard that he was the poor orphan boy from up the valley,

the son of the hard-working widow woman, Janet Jackson, so "eident"

and so industrious, her heart warmed to the mason's apprentice, and

she sent for him to her house. That was a proud day for Tom;

and when he called upon her, he was not more pleased with Miss

Pasley's kindness than delighted at the sight of her little library

of books, which contained more volumes than he had ever seen before.

Having by this time acquired a strong taste for reading, and

exhausted all the little book stores of his friends, the joy of the

young mason may be imagined when Miss Pasley volunteered to lend him

some books from her own library. Of course, he eagerly and

thankfully availed himself of the privilege; and thus, while working

as an apprentice and afterwards as a journeyman, Telford gathered

his first knowledge of British literature, in which he was

accustomed to the close of his life to take such pleasure. He

almost always had some book with him, which he would snatch a few

minutes to read in the intervals of his work; and on winter evenings

he occupied his spare time in poring over such volumes as came in

his way, usually with no better light than the cottage fire.

On one occasion Miss Pasley lent him 'Paradise Lost,' and he took

the book with him to the hill-side to read. His delight was

such that it fairly taxed his powers of expression to describe it.

He could only say, "I read, and read, and glowred; then read, and

read again." He was also a great admirer of Burns, whose

writings so inflamed his mind that at the age of twenty-two, when

barely out of his apprenticeship, we find the young mason actually

breaking out in verse. [p.144]

By diligently reading all the books that he could borrow from

friends and neighbours, Telford made considerable progress in his

learning; and, what with his scribbling of "poetry" and various

attempts at composition, he had become so good and legible a writer

that he was often called upon by his less-educated acquaintances to

pen letters for them to their distant friends. He was always

willing to help them in this way; and, the other working people of

the town making use of his services in the same manner, all the

little domestic and family histories of the place soon became

familiar to him. One evening a Langholm man asked Tom to write

a letter for him to his son in England; and when the young scribe

read over what had been written to the old man's dictation, the

latter, at the end of almost every sentence, exclaimed, "Capital!

capital!" and at the close he said, "Well! I declare, Tom!

Werricht himsel' couldna ha' written a better!"—Wright being a

well-known lawyer or writer" in Langholm.

His apprenticeship over, Telford went on working as a journeyman at

Langholm, his wages at the time being only eighteen pence a day.

What was called the New Town was then in course of erection, and

there are houses still pointed out in it, the walls of which Telford

helped to put together. In the town are three arched

door-heads of a more ornamental character than the rest, of

Telford's hewing; for he was already beginning to set up his

pretensions as a craftsman, and took pride in pointing to the

superior handiwork which proceeded from his chisel. About the

same time, the bridge connecting the Old with the New Town was built

across the Esk at Langholm, and upon that structure he was also

employed. Many of the stones in it were hewn by his hand, and

on several of the blocks forming the land-breast his tool-mark is

still to be seen.

Not long after the bridge was finished, an unusually high

flood or spate swept down the valley. The Esk was "roaring red

frae bank to brae," and it was generally feared that the new brig

would be carried away. Robin Hotson, the master mason, was

from home at the time, and his wife, Tibby, knowing that he was

bound by his contract to maintain the fabric for a period of seven

years, was in a state of great alarm. She ran from one person

to another, wringing her hands and sobbing, "Oh we'll be

ruined—we'll a' be ruined!" In her distress she thought of

Telford, in whom she had great confidence, and called out, "Oh!

where's Tammy Telfer—where's Tammy?" He was immediately sent

for. It was evening, and he was soon found at the house of

Miss Pasley. When he came running up, Tibby exclaimed, "Oh,

Tammy! they've been on the brig, and they say it's shakin'!

It'll be doon!" "Never you heed them, Tibby," said Telford,

clapping her on the shoulder, "there's nae fear o' the brig. I

like it a' the better that it shakes—it proves its weel put the

gither." Tibby's fears, however, were not so easily allayed;

and insisting that she heard the brig "rumlin," she ran up—so the

neighbours afterwards used to say of her—and set her back against

the parapet to hold it together. At this, it is said, "Tam

hodged and leuch;" and Tibby, observing how easily he took it, at

length grew more calm. It soon became clear enough that the

bridge was sufficiently strong; for the flood subsided without doing

it any harm, and it has stood the furious spates of nearly a century

uninjured.

Telford acquired considerable general experience about the

same time as a house-builder, though the structures on which he was

engaged were of a humble order, being chiefly small farm-houses on

the Duke of Buccleugh's estate, with the usual outbuildings.

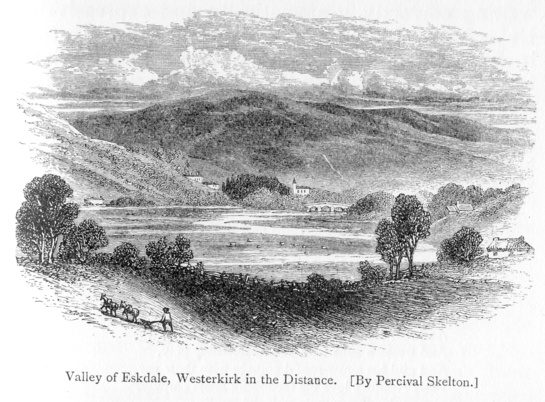

Perhaps the most important of the jobs on which he was employed was

the manse of Westerkirk, where he was comparatively at home.

The hamlet stands on a green hill-side, a little below the entrance

to the valley of the Meggat. It consists of the kirk, the

minister's manse, the parish-school, and a few cottages, every

occupant of which was known to Telford. It is backed by the

purple moors up which he loved to wander in his leisure hours and

read the poems of Fergusson and Burns. The river Esk gurgles

along its rocky bed of the dale, separated from the kirkyard by a

steep bank, covered with natural wood; while near at hand, behind

the manse, stretch the fine woods of Wester Hall, where Telford was

often wont to roam. We can scarcely therefore wonder that,

amidst such pastoral scenery, and reading such books as he did, the

poetic faculty of the country mason should have become so decidedly

developed. It was while working at Westerkirk manse that he

sketched the first draft of his descriptive poem entitled 'Eskdale,'

which was published in the 'Poetical Museum' [p.148]

in 1784.

These early poetical efforts were at least useful in

stimulating his self-education. For the practice of poetical

composition, while it cultivates the sentiment of beauty in thought

and feeling, is probably the best of all exercises in the art of

writing correctly, grammatically, and expressively. By drawing

a man out of his ordinary calling, too, it often furnishes him with

a power of happy thinking which may in after life become a source of

the purest pleasure; and this, we believe, proved to be the case

with Telford, even though he ceased in later years to pursue the

special cultivation of the art.

Shortly after, when work became slack in the district,

Telford undertook to do small jobs on his own account—such as the

hewing of grave-stones and ornamental doorheads. He prided

himself especially upon his hewing, and from the specimens of his

workmanship which are still to be seen in the churchyards of

Langholm and Westerkirk, he had evidently attained considerable

skill. On some of these pieces of masonry the year is carved

1779, or 1780. One of the most ornamental is that set into the

wall of Westerkirk church, being a monumental slab, with an

inscription and moulding, surmounted by a coat of arms, to the

memory of James Pasley of Craig.

He had now learnt all that his native valley could teach him

of the art of masonry; and, bent upon self-improvement and gaining a

larger experience of life, as well as knowledge of his trade, he

determined to seek employment elsewhere. He accordingly left

Eskdale for the first time, in 1780, and sought work in Edinburgh,

where the New Town was then in course of erection on the elevated

land, formerly green fields, extending along the north bank of the

"Nor' Loch." A bridge had been thrown across the Loch in 1769,

the stagnant pond or marsh in the hollow had been filled up, and

Princes Street was rising as if by magic. Skilled masons were

in great demand for the purpose of carrying out these and the

numerous other architectural improvements which were in progress,

and Telford had no difficulty in obtaining employment.

Our stone-mason remained at Edinburgh for about two years,

during which he had the advantage of taking part in first-rate work

and maintaining himself comfortably, while he devoted much of his

spare time to drawing, in its application to architecture. He

took the opportunity of visiting and carefully studying the fine

specimens of ancient work at Holyrood House and Chapel, the Castle,

Heriot's Hospital, and the numerous curious illustrations of middle

age domestic architecture with which the Old Town abounds. He

also made several journeys to the beautiful old chapel of Rosslyn

situated some miles to the south of Edinburgh, making careful

drawings of the more important parts of that building.

When he had thus improved himself, "and studied all that was

to be seen in Edinburgh, in returning to the western border," he

says, "I visited the justly celebrated Abbey of Melrose."

There he was charmed by the delicate and perfect workmanship still

visible even in the ruins of that fine old Abbey; and with his folio

filled with sketches and drawings, he made his way back to Eskdale

and the humble cottage at The Crooks. But not to remain there

long. He merely wished to pay a parting visit to his mother

and other relatives before starting upon a longer journey.

"Having acquired," he says in his Autobiography, "the rudiments of

my profession, I considered that my native country afforded few

opportunities of exercising it to any extent, and therefore judged

it advisable (like many of my countrymen) to proceed southward,

where industry might find more employment and be better

remunerated."

Before setting out, he called upon all his old friends and

acquaintances in the dale—the neighbouring farmers, who had

befriended him and his mother when struggling with poverty—his

schoolfellows, many of whom were preparing to migrate, like himself,

from their native valley—and the many friends and acquaintances he

had made while working as a mason in Langholm. Everybody knew

that Tom was going south, and all wished him God speed. At

length the leave-taking was over, and he set out for London in the

year 1782, when twenty-five years old. He had, like the little

river Meggat, on the banks of which he was born, floated gradually

on towards the outer world: first from the nook in the valley, to

Westerkirk school; then to Langholm and its little circle; and now,

like the Meggat, which flows with the Esk into the ocean, he was

about to be borne away into the wide world. Telford, however,

had confidence in himself, and no one had fears for him. As

the neighbours said, wisely wagging their heads, "Ah, he's an

auldfarran chap is Tam; he'll either mak a spoon or spoil a horn;

any how, he's gatten a good trade at his fingers' ends."

Telford had made all his previous journeys on foot; but this

one he made on horseback. It happened that Sir James

Johnstone, the laird of Wester Hall, had occasion to send a horse

from Eskdale to a member of his family in London, and he had some

difficulty in finding a person to take charge of it. It

occurred to Mr. Jackson, the laird's factor, that this was a capital

opportunity for his cousin Tom, the mason; and it was accordingly

arranged that he should ride the horse to town. When a boy, he

had learnt rough-riding sufficiently well for the purpose; and the

better to fit him for the hardships of the road, Mr. Jackson lent

him his buckskin breeches. Thus Tom set out from his native

valley well mounted, with his little bundle of "traps" buckled

behind him, and, after a prosperous journey, duly reached London,

and delivered up the horse as he had been directed. Long

after, Mr. Jackson used to tell the story of his cousin's first ride

to London with great glee, and he always took care to wind up

with—"but Tam forgot to send me back my breeks!"

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

TELFORD A WORKING MASON IN LONDON, AND FOREMAN

OF MASONS AT PORTSMOUTH.

A COMMON working

man, whose sole property consisted in his mallet and chisels, his

leathern apron and his industry, might not seem to amount to much in

"the great world of London." But, as Telford afterwards used

to say, very much depends on whether the man has got a head with

brains in it of the right sort upon his shoulders. In London,

the weak man is simply a unit added to the vast floating crowd, and

may be driven hither and thither, if he do not sink altogether;

while the strong man will strike out, keep his head above water, and

make a course for himself, as Telford did. There is indeed a

wonderful impartiality about London. There the capable person

usually finds his place. When work of importance is required,

nobody cares to ask where the man who can do it best comes from, or

what he has been, but what he is, and what he can do. Nor did

it ever stand in Telford's way that his father had been a poor

shepherd in Eskdale, and that he himself had begun his London career

by working for weekly wages with a mallet and chisel.

After duly delivering up the horse, Telford proceeded to

present a letter with which he had been charged by his friend Miss

Pasley on leaving Langholm. It was addressed to her brother,

Mr. John Pasley, an eminent London merchant, brother also of Sir

Thomas Pasley, and uncle of the Malcolms. Miss Pasley

requested his influence on behalf of the young mason from Eskdale,

the bearer of the letter. Mr. Pasley received his countryman

kindly, and furnished him with letters of introduction to Sir

William Chambers, the architect of Somerset House, then in course of

erection. It was the finest architectural work in progress in

the metropolis, and Telford, desirous of improving himself by

experience of the best kind, wished to be employed upon it. It

did not, indeed, need any influence to obtain work there, for good

hewers were in demand; but our mason thought it well to make sure,

and accordingly provided himself beforehand with the letter of

introduction to the architect. He was employed immediately,

and set to work among the hewers, receiving the usual wages for his

labour.

Mr. Pasley also furnished him with a letter to Mr. Robert

Adam, [p.154] another

distinguished architect of the time; and Telford seems to have been

much gratified by the civility which he received from him. Sir

William Chambers he found haughty and reserved, probably being too

much occupied to bestow attention on the Somerset House hewer, while

he found Adam to be affable and communicative. "Although I

derived no direct advantage from either," Telford says, "yet so

powerful is manner, that the latter left the most favourable

impression; while the interviews with both convinced me that my

safest plan was to endeavour to advance, if by slower steps, yet by

independent conduct."

There was a good deal of fine hewer's work about Somerset

House, and from the first Telford aimed at taking the highest place

as an artist and tradesman in that line. [p.155]

Diligence, carefulness, and observation will always carry a man

onward and upward; and before long we find that Telford had

succeeded in advancing himself to the rank of a first-class mason.

Judging from his letters written about this time to his friends in

Eskdale, he seems to have been very cheerful and happy; and his

greatest pleasure was in calling up recollections of his native

valley. He was full of kind remembrances for everybody.

"How is Andrew, and Sandy, and Aleck, and Davie?" he would say; and

"remember me to all the folk of the nook." He seems to have

made a round of the persons from Eskdale in or about London before

he wrote, as his letters were full of messages from them to their

friends at home; for in those days postage was dear, and as much as

possible was necessarily packed within the compass of a working

man's letter. In one, written after more than a year's

absence, he said he envied the visit which a young surgeon of his

acquaintance was about to pay to the valley; "for the meeting of

long absent friends," he added, "is a pleasure to be equalled by few

other enjoyments here below." [p.157-1]

He had now been more than a year in London, during which he

had acquired much practical information both in the useful and

ornamental branches of architecture. Was he to go on as a

working mason? or what was to be his next move? He had been

quietly making his observations upon his companions, and had come to

the conclusion that they very much wanted spirit, and, more than

all, forethought. He found very clever workmen about him with

no idea whatever beyond their week's wages. For these they

would make every effort: they would work hard, exert themselves to

keep their earnings up to the highest point, and very readily

"strike" to secure an advance; but as for making a provision for the

next week, or the next year, he thought them exceedingly

thoughtless. On the Monday mornings they began "clean;" and on

Saturdays their week's earnings were spent. Thus they lived

from one week to another—their limited notion of "the week" seeming

to bound their existence.

Telford, on the other hand, looked upon the week as only one

of the storeys of a building; and upon the succession of weeks,

running on through years, he thought that the complete life

structure should be built up. He thus describes one of the

best of his fellow-workmen at that time the only individual he had

formed an intimacy with: "He has been six years at Somerset House,

and is esteemed the finest workman in London, and consequently in

England. He works equally in stone and marble. He has

excelled the professed carvers in cutting Corinthian capitals and

other ornaments about this edifice, many of which will stand as a

monument to his honour. He understands drawing thoroughly, and

the master he works under looks on him as the principal support of

his business. This man, whose name is Mr. Hatton, may be half

a dozen years older than myself at most. He is honesty and

good nature itself, and is adored by both his master and

fellow-workmen. Notwithstanding his extraordinary skill and

abilities, he has been working all this time as a common journeyman,

contented with a few shillings a week more than the rest; but I

believe your uneasy friend has kindled a spark in his breast that he

never felt before." [p.157-1]

In fact, Telford had formed the intention of inducing this

admirable fellow to join him in commencing business as builders on

their own account. "There is nothing done in stone or marble,"

he says, "that we cannot do in the completest manner." Mr.

Robert Adam, to whom the scheme was mentioned, promised his support,

and said he would do all in his power to recommend them. But

the great difficulty was money, which neither of them possessed; and

Telford, with grief, admitting that this was an "insuperable bar,"

went no further with the scheme.

About this time Telford was consulted by Mr. Pulteney [p.157-2]

respecting the alterations making in the mansion at Wester Hall, and

was often with him on this business. We find him also writing

down to Langholm for the prices of roofing, masonry, and

timber-work, with a view to preparing estimates for a friend who was

building a house in that neighbourhood. Although determined to

reach the highest excellence as a manual worker, it is clear that he

was already aspiring to be something more. Indeed, his

steadiness, perseverance, and general ability, pointed him out as

one well worthy of promotion.

How he achieved his next step we are not informed; but we

find him, in July, 1784, engaged in superintending the erection of a

house, after a design by Mr. Samuel Wyatt, intended for the

residence of the Commissioner (now occupied by the Port Admiral) at

Portsmouth Dockyard, together with a new chapel, and several

buildings connected with the Yard. Telford took care to keep

his eyes open to all the other works going forward in the

neighbourhood, and he states that he had frequent opportunities of

observing the various operations necessary in the foundation and

construction of graving-docks, wharf-walls, and such like, which

were among the principal occupations of his after-life.

The letters written by him from Portsmouth to his Eskdale

correspondents about this time were cheerful and hopeful, like those

he had sent from London. His principal grievance was that he

received so few from home, but he supposed that opportunities for

forwarding them by hand had not occurred, postage being so dear as

scarcely then to be thought of. To tempt them to

correspondence he sent copies of the poems which he still continued

to compose in the leisure of his evenings: one of these was a 'Poem

on Portsdown Hill.' As for himself, he was doing very well.

The buildings were advancing satisfactorily; but, "above all," said

he, "my proceedings are entirely approved by the Commissioners and

officers here—so much so that they would sooner go by my advice than

my master's, which is a dangerous point, being difficult to keep

their good graces as well as his. However, I will contrive to

manage it." [p.159]

The following is his own account of the manner in which he

was usually occupied during the winter months while at Portsmouth

Dock:—"I rise in the morning at 7 (February 1st), and will get up

earlier as the days lengthen until it come to 5 o'clock. I

immediately set to work to make out accounts, write on matters of

business, or draw, until breakfast, which is at 9. Then I go

into the Yard about 10, see that all are at their posts, and am

ready to advise about any matters that may require attention.

This, and going round the several works, occupies until about

dinner-time, which is at 2 and after that I again go round and

attend to what may be wanted. I draw till 5; then tea; and

after that I write, draw, or read until half after 9; then comes

supper and bed. This is my ordinary round, unless when I dine

or spend an evening with a friend; but I do not make many friends,

being very particular, nay, nice to a degree. My business

requires a great deal of writing and drawing, and this work I always

take care to keep under by reserving my time for it, and being in

advance of my work rather than behind it. Then, as knowledge

is my most ardent pursuit, a thousand things occur which call for

investigation which would pass unnoticed by those who are content to

trudge only in the beaten path. I am not contented unless I

can give a reason for every particular method or practice which is

pursued. Hence I am now very deep in chemistry. The mode

of making mortar in the best way led me to inquire into the nature

of lime. Having, in pursuit of this inquiry, looked into some

books on chemistry, I perceived the field was boundless; but that to

assign satisfactory reasons for many mechanical processes required a

general knowledge of that science. I have therefore borrowed a

MS. copy of Dr. Black's Lectures. I have bought his

'Experiments on Magnesia and Quicklime,' and also Fourcroy's

Lectures, translated from the French by one Mr. Elliot, of

Edinburgh. And I am determined to study the subject with

unwearied attention until I attain some accurate knowledge of

chemistry, which is of no less use in the practice of the arts than

it is in that of medicine." He adds, that he continues to

receive the cordial approval of the Commissioners for the manner in

which he performs his duties, and says, "I take care to be so far

master of the business committed to me as that none shall be able to

eclipse me in that respect." [p.160]

At the same time he states he is taking great delight in

Freemasonry, and is about to have a lodge-room at the George Inn

fitted up after his plans and under his direction. Nor does he

forget to add that he has his hair powdered every day, and puts on a

clean shirt three times a week.

The Eskdale mason was evidently getting on, as he deserved to

do. But he was not puffed up. To his Langholm friend he

averred that "he would rather have it said of him that he possessed

one grain of good nature or good sense than shine the finest puppet

in Christendom." "Let my mother know that I am well," he wrote

to Andrew Little, "and that I will print her a letter soon." [p.161]

For it was a practice of this good son, down to the period of his

mother's death, no matter how much burdened he was with business, to

set apart occasional times for the careful penning of a letter in

printed characters, that she might the more easily be able to

decipher it with her old and dimmed eyes by her cottage fireside at

The Crooks. As a man's real disposition usually displays

itself most strikingly in small matters—like light, which gleams the

most brightly when seen through narrow chinks—it will probably be

admitted that this trait, trifling though it may appear, was truly

characteristic of the simple and affectionate nature of the hero of

our story.

The buildings at Portsmouth were finished by the end of 1786,

when Telford's duties there being at an end, and having no

engagement beyond the termination of the contract, he prepared to

leave, and began to look about him for other employment.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

BECOMES SURVEYOR FOR THE COUNTY OF SALOP.

MR.

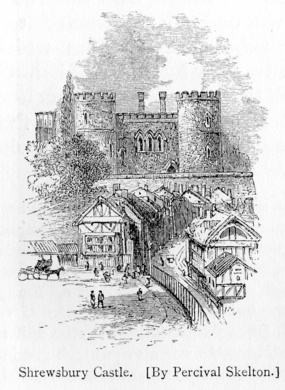

PULTENEY, member for

Shrewsbury, was the owner of extensive estates in that neighbourhood

by virtue of his marriage with the niece of the last Earl of Bath.

Having resolved to fit up the Castle there as a residence, he

bethought him of the young Eskdale mason, who had, some years

before, advised him as to the repairs of the Johnstone mansion at

Wester Hall. Telford was soon found, and engaged to go down to

Shrewsbury to superintend the necessary alterations. Their

execution occupied his attention for some time, and during their

progress he was so fortunate as to obtain the appointment of

Surveyor of Public Works for the county of Salop, most probably

through the influence of his patron. Indeed, Telford was known

to be so great a favourite with Mr. Pulteney that at Shrewsbury he

usually went by the name of "Young Pulteney."

Much of his attention was from this time occupied with the

surveys and repairs of roads, bridges, and gaols, and the

supervision of all public buildings under the control of the

magistrates of the county. He was also frequently called upon

by the corporation of the borough of Shrewsbury to furnish plans for

the improvement of the streets and buildings of that fine old town;

and many alterations were carried out under his direction during the

period of his residence there.

While the Castle repairs were in course of execution, Telford

was called upon by the justices to superintend the erection of a new

gaol, the plans for which had already been prepared and settled.

The benevolent Howard, who devoted himself with such zeal to gaol

improvement, on hearing of the intentions of the magistrates, made a

visit to Shrewsbury for the purpose of examining the plans; and the

circumstance is thus adverted to by Telford in one of his letters to

his Eskdale correspondent:—"About ten days ago I had a visit from

the celebrated John Howard, Esq. I say I, for he was on his

tour of gaols and infirmaries; and those of Shrewsbury being both

under my direction, this was, of course, the cause of my being thus

distinguished. I accompanied him through the infirmary and the

gaol. I showed him the plans of the proposed new buildings,

and had much conversation with him on both subjects. In

consequence of his suggestions as to the former, I have revised and

amended the plans, so as to carry out a thorough reformation; and my

alterations having been approved by a general board, they have been

referred to a committee to carry out. Mr. Howard also took

objection to the plan of the proposed gaol, and requested me to

inform the magistrates that, in his opinion, the interior courts

were too small, and not sufficiently ventilated; and the

magistrates, having approved his suggestions, ordered the plans to

be amended accordingly. You may easily conceive how I enjoyed

the conversation of this truly good man, and how much I would strive

to possess his good opinion. I regard him as the guardian

angel of the miserable. He travels into all parts of Europe

with the sole object of doing good, merely for its own sake, and not

for the sake of men's praise. To give an instance of his

delicacy, and his desire to avoid public notice, I may mention that,

being a Presbyterian, he attended the meeting-house of that

denomination in Shrewsbury on Sunday morning, on which occasion I

accompanied him; but in the afternoon he expressed a wish to attend

another place of worship, his presence in the town having excited

considerable curiosity, though his wish was to avoid public

recognition. Nay, more, he assures me that he hates

travelling, and was born to be a domestic man. He never sees

his country-house but he says within himself, 'Oh! might I but rest

here, and never more travel three miles from home; then should I be

happy indeed!' But he has become so committed, and so pledged

himself to his own conscience to carry out his great work, that he

says he is doubtful whether he will ever be able to attain the

desire of his heart—life at home. He never dines out, and

scarcely takes time to dine at all: he says he is growing old, and

has no time to lose. His manner is simplicity itself.

Indeed, I have never yet met so noble a being. He is going

abroad again shortly on one of his long tours of mercy." [p.164]

The journey to which Telford here refers was Howard's last. In

the following year he left England to return no more; and the great

and good man died at Cherson, on the shores of the Black Sea, less

than two years after his interview with the young engineer at

Shrewsbury.

Telford writes to his Langholm friend at the same time, that

he is working very hard, and studying to improve himself in branches

of knowledge in which he feels himself deficient. He is

practising very temperate habits: for half a year past he has taken

to drinking water only, avoiding all sweets, and eating no "nick-nacks."

He has "sowens and milk" (oatmeal flummery) every night, for his

supper. His friend having asked his opinion of politics, he

says he really knows nothing about them; he had been so completely

engrossed by his own business that he has not had time to read even

a newspaper. But, though an ignoramus in politics, he has been

studying lime, which is more to his purpose. If his

friend can give him any information about that, he will promise to

read a newspaper now and then in the ensuing session of Parliament,

for the purpose of forming some opinion of politics: he adds,

however, "not if it interfere with my business—mind that!"

His friend told him that he proposed translating a system of

chemistry. "Now you know," wrote Telford, "that I am chemistry

mad; and if I were near you, I would make you promise to communicate

any information on the subject that you thought would be of service

to your friend, especially about calcareous matters and the mode of

forming the best composition for building with, as well above as

below water. But not to be confined to that alone, for you

must know I have a book for the pocket, [p.165]

which I always carry with me, into which I have extracted the

essence of Fourcroy's Lectures, Black on Quicklime, Scheele's

Essays, Watson's Essays, and various points from the letters of my

respected friend Dr. Irving. [p.166-1]

So much for chemistry. But I have also crammed into it facts

relating to mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics, and all manner of

stuff, to which I keep continually adding, and it will be a charity

to me if you will kindly contribute your mite." [p.166-2]

He says it has been, and will continue to be, his aim to endeavour

to unite those "two frequently jarring pursuits, literature and

business;" and he does not see why a man should be less efficient in

the latter capacity because he has well informed, stored, and

humanised his mind by the cultivation of letters. There was

both good sense and sound practical wisdom in this view of Telford.

While the gaol was in course of erection, after the improved

plans suggested by Howard, a variety of important matters occupied

the county surveyor's attention. During the summer of 1788 he

says he is very much occupied, having about ten different jobs on

hand: roads, bridges, streets, drainage-works, gaol, and infirmary.

Yet he had time to write verses, copies of which he forwarded to his

Eskdale correspondent, inviting his criticism. Several of

these were elegiac lines, somewhat exaggerated in their praises of

the deceased, though doubtless sincere. One poem was in memory

of George Johnstone, Esq., a member of the Wester Hall family, and

another on the death of William Telford, an Eskdale farmer's son, an

intimate friend and schoolfellow of our engineer. [p.167]

These, however, were but the votive offerings of private friendship,

persons more immediately about him knowing nothing of his stolen

pleasures in verse-making. He continued to be shy of

strangers, and was very "nice," as he calls it, as to those whom he

admitted to his bosom.

Two circumstances of considerable interest occurred in the

course of the same year (1788), which are worthy of passing notice.

The one was the fall of the church of St. Chad's, at Shrewsbury; the

other was the discovery of the ruins of the Roman city of Uriconium,

in the immediate neighbourhood. The church of St. Chad's was

about four centuries old, and stood greatly in need of repairs.

The roof let in the rain upon the congregation, and the parish

vestry met to settle the plans for mending it; but they could not

agree about the mode of procedure. In this emergency Telford

was sent for, and requested to advise what was best to be done.

After a rapid glance at the interior, which was in an exceedingly

dangerous state, he said to the churchwardens, "Gentlemen, we'll

consult together on the outside, if you please." He found that

not only the roof but the walls of the church were in a most decayed

state. It appeared that, in consequence of graves having been

dug in the loose soil close to the shallow foundation of the

north-west pillar of the tower, it had sunk so as to endanger the

whole structure. "I discovered," says he, "that there were

large fractures in the walls, on tracing which I found that the old

building was in a most shattered and decrepit condition, though

until then it had been scarcely noticed. Upon this I declined

giving any recommendation as to the repairs of the roof unless they

would come to the resolution to secure the more essential parts, as

the fabric appeared to me to be in a very alarming condition.

I sent in a written report to the same effect." [p.168]

The parish vestry again met, and the report was read; but the

meeting exclaimed against so extensive a proposal, imputing mere

motives of self-interest to the surveyor. "Popular clamour,"

says Telford, "overcame my report. 'These fractures,'

exclaimed the vestrymen, 'have been there from time immemorial;' and

there were some otherwise sensible persons, who remarked that

professional men always wanted to carve out employment for

themselves, and that the whole of the necessary repairs could be

done at a comparatively small expense." [p.169-1]

The vestry then called in another person, a mason of the town, and

directed him to cut away the injured part of a particular pillar, in

order to underbuild it. On the second evening after the

commencement of the operations, the sexton was alarmed by a fall of

lime-dust and mortar when he attempted to toll the great bell, on

which he immediately desisted and left the church. Early next

morning (on the 9th of July), while the workmen were waiting at the

church door for the key, the bell struck four, and the vibration at

once brought down the tower, which overwhelmed the nave, demolishing

all the pillars along the north side, and shattering the rest.

"The very parts I had pointed out," says Telford, "were those which

gave way, and down tumbled the tower, forming a very remarkable

ruin, which astonished and surprised the vestry, and roused them

from their infatuation, though they have not yet recovered from the

shock." [p.169-2]

The other circumstance to which we have above referred was

the discovery of the Roman city of Uriconium, near Wroxeter, about

five miles from Shrewsbury, in the year 1788. The situation of

the place is extremely beautiful, the river Severn flowing along its

western margin, and forming a barrier against what were once the

hostile districts of West Britain. For many centuries the dead

city had slept under the irregular mounds of earth which covered it,

like those of Mossul and Nineveh. Farmers raised heavy crops

of turnips and grain from the surface; and they scarcely ever

ploughed or harrowed the ground without turning up Roman coins or

pieces of pottery. They also observed that in certain places

the corn was more apt to be scorched in dry weather than in others—a

sure sign to them that there were ruins underneath; and their

practice, when they wished to find stones for building, was to set a

mark upon the scorched places when the corn was on the ground, and

after harvest to dig down, sure of finding the store of stones which

they wanted for walls, cottages, or farm-houses. In fact, the

place came to be regarded in the light of a quarry, rich in

ready-worked materials for building purposes. A quantity of

stone being wanted for the purpose of erecting a blacksmith's shop,

on digging down upon one of the marked places, the labourers came

upon some ancient works of a more perfect appearance than usual.

Curiosity was excited—antiquarians made their way to the spot—and

lo! they pronounced the ruins to be neither more nor less than a

Roman bath, in a remarkably perfect state of preservation. Mr.

Telford was requested to apply to Mr. Pulteney, the lord of the

manor, to prevent the destruction of these interesting remains, and

also to permit the excavations to proceed, with a view to the

buildings being completely explored. This was readily granted,

and Mr. Pulteney authorised Telford himself to conduct the necessary

excavations at his expense. This he promptly proceeded to do,

and the result was, that an extensive hypocaust apartment was

brought to light, with baths, sudatorium, dressing-room, and a

number of tile pillars all forming parts of a Roman

floor—sufficiently perfect to show the manner in which the building

had been constructed and used. [p.171]

Among Telford's less agreeable duties about the same time was

that of keeping the felons at work. He had to devise the ways

and means of employing them without risk of their escaping, which

gave him much trouble and anxiety. "Really," he said, "my

felons are a very troublesome family. I have had a great deal

of plague from them, and I have not yet got things quite in the

train that I could wish. I have had a dress made for them of

white and brown cloth, in such a way that they are pyebald.

They have each a light chain about one leg. Their allowance in

food is a penny loaf and a halfpenny worth of cheese for breakfast;

a penny loaf, a quart of soup, and half a pound of meat for dinner;

and a penny loaf and a halfpenny worth of cheese for supper; so that

they have meat and clothes at all events. I employ them in

removing earth, serving masons or bricklayers, or in any common

labouring work on which they can be employed; during which time, of

course, I have them strictly watched."

Much more pleasant was his first sight of Mrs. Jordan at the

Shrewsbury theatre, where he seems to have been worked up to a pitch

of rapturous enjoyment. She played for six nights there at the

race time, during which there were various other entertainments.

On the second day there was what was called an Infirmary Meeting, or

an assemblage of the principal county gentlemen in the infirmary, at

which, as county surveyor, Telford was present. They proceeded

thence to church to hear a sermon preached for the occasion; after

which there was a dinner, followed by a concert. He attended

all. The sermon was preached in the new pulpit, which had just

been finished after his design, in the Gothic style; and he

confidentially informed his Langholm correspondent that he believed

the pulpit secured greater admiration than the sermon. With

the concert he was completely disappointed, and he then became

convinced that he had no ear for music. Other people seemed

very much pleased; but for the life of him he could make nothing of

it. The only difference that he recognised between one tune

and another was that there was a difference in the noise. "It

was all very fine," he said, "I have no doubt; but I would not give

a song of Jock Stewart [p.172-1]

for the whole of them. The melody of sound is thrown away upon

me. One look, one word of Mrs. Jordan, has more effect upon me

than all the fiddlers in England. Yet I sat down and tried to

be as attentive as any mortal could be. I endeavoured, if

possible, to get up an interest in what was going on; but it was all

of no use. I felt no emotion whatever, excepting only a strong

inclination to go to sleep. It must be a defect; but it is a

fact, and I cannot help it. I suppose my ignorance of the

subject, and the want of musical experience in my youth, may be the

cause of it." [p.172-2]

Telford's mother was still living in her old cottage at The

Crooks. Since he had parted from her, he had written many

printed letters to keep her informed of his progress; and he never

wrote to any of his friends in the dale without including some

message or other to his mother. Like a good and dutiful son,

he had taken care out of his means to provide for her comfort in her

declining years. "She has been a good mother to me," he said,

"and I will try and be a good son to her." In a letter written

from Shrewsbury about this time, enclosing a ten pound note, seven

pounds of which were to be given to his mother, he said, "I have

from time to time written William Jackson [his cousin] and told him

to furnish her with whatever she wants to make her comfortable; but

there may be many little things she may wish to have, and yet not

like to ask him for. You will therefore agree with me that it

is right she should have a little cash to dispose of in her own way.

. . . I am not rich yet; but it will ease my mind to set my mother

above the fear of want. That has always been my first object;

and next to that, to be the somebody which you have always

encouraged me to believe I might aspire to become. Perhaps

after all there may be something in it!" [p.173]

He now seems to have occupied much of his leisure hours in

miscellaneous reading. Among the numerous books which he read,

he expressed the highest admiration for Sheridan's 'Life of Swift.'

But his Langholm friend, who was a great politician, having invited

his attention to politics, Telford's reading gradually extended in

that direction. Indeed the exciting events of the French

Revolution then tended to make all men more or less politicians.

The capture of the Bastille by the people of Paris in 1789 passed

like an electric thrill through Europe. Then followed the

Declaration of Rights; after which, in the course of six months, all

the institutions which had before existed in France were swept away,

and the reign of justice was fairly inaugurated upon earth!

In the spring of 1791 the first part of Paine's 'Rights of

Man' appeared, and Telford, like many others, read it, and was at

once carried away by it. Only a short time before, he had

admitted with truth that he knew nothing of politics; but no sooner

had he read Paine than he felt completely enlightened. He now

suddenly discovered how much reason he and everybody else in England

had for being miserable. While residing at Portsmouth, he had

quoted to his Langholm friend the lines from Cowper's 'Task,' then

just published, beginning "Slaves cannot breathe in England;" but

lo! Mr. Paine had filled his imagination with the idea that England

was nothing but a nation of bondmen and aristocrats. To his

natural mind, the kingdom had appeared to be one in which a man had

pretty fair play, could think and speak, and do the thing he

would,—tolerably happy, tolerably prosperous, and enjoying many

blessings. He himself had felt free to labour, to prosper, and

to rise from manual to head work. No one had hindered him; his

personal liberty had never been interfered with; and he had freely

employed his earnings as he thought proper. But now the whole

thing appeared a delusion. Those rosy-cheeked old country

gentlemen who came riding into Shrewsbury to quarter sessions, and

were so fond of their young Scotch surveyor—occupying themselves in

building bridges, maintaining infirmaries, making roads, and

regulating gaols those county magistrates and members of parliament,

aristocrats all, were the very men who, according to Paine, were

carrying the country headlong to ruin!

If Telford could not offer an opinion on politics before,

because he "knew nothing about them," he had now no such difficulty.

Had his advice been asked about the foundations of a bridge, or the

security of an arch, he would have read and studied much before

giving it; he would have carefully inquired into the chemical

qualities of different kinds of lime into the mechanical principles

of weight and resistance, and such like; but he had no such

hesitation in giving an opinion about the foundations of a

constitution of more than a thousand years' growth. Here, like

other young politicians, with Paine's book before him, he felt

competent to pronounce a decisive judgment at once. "I am

convinced," said he, writing to his Langholm friend, "that the

situation of Great Britain is such, that nothing short of some

signal revolution can prevent her from sinking into bankruptcy,

slavery, and insignificancy." He held that the national

expenditure was so enormous, [p.175]

arising from the corrupt administration of the country, that it was

impossible the "bloated mass" could hold together any longer; and as

he could not expect that "a hundred Pulteneys," such as his

employer, could be found to restore it to health, the conclusion he

arrived at was that ruin was "inevitable." [p.176-1]

In the same letter in which these observations occur, Telford

alluded to the disgraceful riots at Birmingham, in the course of

which Dr. Priestley's house and library were destroyed. As the

outrages were the work of the mob, Telford could not charge the

aristocracy with them; but with equal injustice he laid the blame at

the door of "the clergy," who had still less to do with them,

winding up with the prayer, "May the Lord mend their hearts and

lessen their incomes!"

Fortunately for Telford, his intercourse with the townspeople

of Shrewsbury was so small that his views on these subjects were

never known; and we very shortly find him employed by the clergy

themselves in building for them a new church in the town of

Bridgenorth. His patron and employer, Mr. Pulteney, however,

knew of his extreme views, and the knowledge came to him quite

accidentally. He found that Telford had made use of his frank

to send through the post a copy of Paine's 'Rights of Man' to his

Langholm correspondent, [p.176-2]

where the pamphlet excited as much fury in the minds of some of the

people of that town as it had done in that of Telford himself.

The "Langholm patriots" broke out into drinking revolutionary toasts

at the Cross, and so disturbed the peace of the little town that

some of them were confined for six weeks in the county gaol.

Mr. Pulteney was very indignant at the liberty Telford had

taken with his frank, and a rupture between them seemed likely to

ensue; but the former was forgiving, and the matter went no further.

It is only right to add, that as Telford grew older and wiser, he

became more careful in jumping at conclusions on political topics.

The events which shortly occurred in France tended in a great

measure to heal his mental distresses as to the future of England.

When the "liberty" won by the Parisians ran into riot, and the

"Friends of Man" occupied themselves in taking off the heads of

those who differed from them, he became wonderfully reconciled to

the enjoyment of the substantial freedom which, after all, was

secured to him by the English Constitution. At the same time,

he was so much occupied in carrying out his important works, that he

found but little time to devote either to political speculation or

to verse-making.

While living at Shrewsbury, he had his poem of 'Eskdale'

reprinted for private circulation. We have also seen several

MS. verses by him, written about the same period, which do

not appear ever to have been printed. One of these—the best—is

entitled 'Verses to the Memory of James Thomson, author of "Liberty,

a poem;"' another is a translation from Buchanan, 'On the Spheres;'

and a third, written in April, 1792, is entitled 'To Robin Burns,

being a postscript to some verses addressed to him on the

establishment of an Agricultural Chair in Edinburgh.' It would

unnecessarily occupy our space to print these effusions; and, to

tell the truth, they exhibit few if any indications of poetic power.

No amount of perseverance will make a poet of a man in whom the

divine gift is not born. The true line of Telford's genius lay

in building and engineering, in which direction we now propose to

follow him.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

TELFORD'S FIRST EMPLOYMENT AS AN ENGINEER.

AS surveyor for

the county, Telford was frequently called upon by the magistrates to

advise them as to the improvement of roads and the building or

repair of bridges. His early experience of bridge-building in

his native district now proved of much service to him, and he used

often to congratulate himself, even when he had reached the highest

rank in his profession, upon the circumstances which had compelled

him to begin his career by working with his own hands. To be a

thorough judge of work, he held that a man must himself have been

practically engaged in it. "Not only," he said, "are the

natural senses of seeing and feeling requisite in the examination of

materials, but also the practised eye, and the hand which has had

experience of the kind and qualities of stone, of lime, of iron, of

timber, and even of earth, and of the effects of human ingenuity in

applying and combining all these substances, are necessary for

arriving at mastery in the profession; for, how can a man give

judicious directions unless he possesses personal knowledge of the

details requisite to effect his ultimate purpose in the best and

cheapest manner? It has happened to me more than once, when

taking opportunities of being useful to a young man of merit, that I

have experienced opposition in taking him from his books and

drawings, and placing a mallet, chisel, or trowel in his hand, till,

rendered confident by the solid knowledge which experience only can

bestow, he was qualified to insist on the due performance of

workmanship, and to judge of merit in the lower as well as the

higher departments of a profession in which no kind or degree of

practical knowledge is superfluous."

Telford's Montford Bridge, Shropshire, spanning the

River Severn.

Built by John Carline Jr and John Tilley between 1790 and 1792.

Picture Wikipedia.

The first bridge designed and built under Telford's

superintendence was one of no great magnitude, across the river

Severn at Montford, about four miles west of Shrewsbury. It

was a stone bridge of three elliptical arches, one of 58 feet and

two of 55 feet span each. The Severn at that point is deep and

narrow, and its bed and banks are of alluvial earth. It was

necessary to make the foundations very secure, as the river is

subject to high floods; and this was effectually accomplished by

means of coffer-dams. The building was substantially executed

in red sandstone, and proved a very serviceable bridge, forming part

of the great high road from Shrewsbury into Wales. It was

finished in the year 1792.

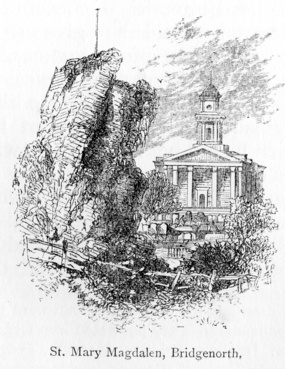

St. Mary Magdalen Church, Bridgnorth. Designed

by Telford

and built by John Rhodes and Michael Head between 1792 and 1795.

Picture Wikipedia.

In the same year, we find Telford engaged as an architect in

preparing the designs and superintending the construction of the new

parish church of St. Mary Magdalen at Bridgenorth. It stands

at the end of Castle Street, near to the old ruined fortress perched

upon the bold red sandstone bluff on which the upper part of the

town is built. The situation of the church is very fine, and

an extensive view of the beautiful vale of the Severn is obtained

from it. Telford's design is by no means striking; "being," as

he said, "a regular Tuscan elevation; the inside is as regularly

Ionic: its only merit is simplicity and uniformity; it is surmounted

by a Doric tower, which contains the bells and a clock." A

graceful Gothic church would have been more appropriate to the

situation, and a much finer object in the landscape; but Gothic was

not then in fashion—only a mongrel mixture of many styles, without

regard to either purity or gracefulness. The church, however,

proved comfortable and commodious, and these were doubtless the

points to which the architect paid most attention.

His completion of the church at Bridgenorth to the

satisfaction of the inhabitants, brought Telford a commission, in

the following year, to erect a similar edifice at Coalbrookdale.

But in the mean time, to enlarge his knowledge and increase his

acquaintance with the best forms of architecture, he determined to

make a journey to London and through some of the principal towns of

the south of England. He accordingly visited Gloucester,

Worcester, and Bath, remaining several days in the last-mentioned

city. He was charmed beyond expression by his journey through

the manufacturing districts of Gloucestershire, more particularly by

the fine scenery of the Vale of Stroud. The whole seemed to

him a smiling scene of prosperous industry and middle-class comfort.

But passing out of this "Paradise," as he styled it, another

stage brought him into a region the very opposite. "We

stopped," says he, "at a little alehouse on the side of a rough hill

to water the horses, and lo! the place was full of drunken

blackguards, bellowing out 'Church and King!' A poor ragged

German Jew happened to come up, whom those furious loyalists had set

upon and accused of being a Frenchman in disguise. He

protested that he was only a poor German who 'cut de corns,' and

that all he wanted was to buy a little bread and cheese.

Nothing would serve them but they must carry him before the Justice.

The great brawny fellow of a landlord swore he should have nothing

in his house, and, being a constable, told him that he would carry

him to gaol. I interfered, and endeavoured to pacify the

assailants of the poor man; when suddenly the landlord, snatching up

a long knife, sliced off about a pound of raw bacon from a ham which

hung overhead, and, presenting it to the Jew, swore that if he did

not swallow it down at once he should not be allowed to go.

The man was in a worse plight than ever. He said he was a

'poor Shoe,' and durst not eat that. In the midst of the

uproar, Church and King were forgotten, and eventually I prevailed

upon the landlord to accept from me as much as enabled poor little

Moses to get his meal of bread and cheese; and by the time the coach

started they all seemed perfectly reconciled." [p.182]

Telford was much gratified by his visit to Bath, and

inspected its fine buildings with admiration. But he thought

that Mr. Wood, who, he says, "created modern Bath," had left no

worthy successor. In the buildings then in progress he saw

clumsy designers at work, "blundering round about a meaning," if,

indeed, there was any meaning at all in their designs, which he

confessed he failed to see. From Bath he went to London by

coach, making the journey in safety, "although," he says, "the

collectors had been doing duty on Hounslow Heath." During his

stay in London he carefully examined the principal public buildings

by the light of the experience which he had gained since he last saw

them. He also spent a good deal of his time in studying rare

and expensive works on architecture—the use of which he could not

elsewhere procure—at the libraries of the Antiquarian Society and

the British Museum. There he perused the various editions of

Vitruvius and Palladio, as well as Wren's 'Parentalia.' He

found a rich store of ancient architectural remains in the British

Museum, which he studied with great care; antiquities from Athens,

Baalbec, Palmyra, and Herculaneum; "so that," he says, "what with

the information I was before possessed of, and that which I have now

accumulated, I think I have obtained a tolerably good general notion

of architecture."

From London he proceeded to Oxford, where he carefully

inspected its colleges and churches, afterwards expressing the great

delight and profit which he had derived from his visit. He was

entertained while there by Mr. Robertson, an eminent mathematician,

then superintending the publication of an edition of the works of

Archimedes. The architectural designs of buildings that most

pleased him were those of Dr. Aldrich, Dean of Christchurch about

the time of Sir Christopher Wren. He tore himself from Oxford

with great regret, proceeding by Birmingham on his way home to

Shrewsbury: "Birmingham," he says, "famous for its buttons and

locks, its ignorance and barbarism—its prosperity increases with the

corruption of taste and morals. Its nick-nacks, hardware, and

gilt gimcracks are proofs of the former; and its locks and bars, and

the recent barbarous conduct of its populace, [p.184]

are evidences of the latter." His principal object in visiting

the place was to call upon a stained glass-maker respecting a window

for the new church at Bridgenorth.

On his return to Shrewsbury, Telford proposed to proceed with

his favourite study of architecture; but this, said he, "will

probably be very slowly, as I must attend to my every day

employment," namely, the superintendence of the county road and

bridge repairs, and the direction of the convicts' labour. "If

I keep my health, however," he added, "and have no unforeseen

hindrance, it shall not be forgotten, but will be creeping on by

degrees." An unforeseen circumstance, though not a hindrance,

did very shortly occur, which launched Telford upon a new career,

for which his unremitting study, as well as his carefully improved

experience, eminently fitted him: we refer to his appointment as

engineer to the Ellesmere Canal Company.

The conscientious carefulness with which Telford performed

the duties entrusted to him, and the skill with which he directed

the works placed under his charge, had secured the general

approbation of the gentlemen of the county. His

straightforward and outspoken manner had further obtained for him

the friendship of many of them. At the meetings of

quarter-sessions his plans had often to encounter considerable

opposition, and, when called upon to defend them, he did so with

such firmness, persuasiveness, and good temper, that he usually

carried his point. "Some of the magistrates are ignorant," he

wrote in 1789, "and some are obstinate: though I must say that on

the whole there is a very respectable bench, and with the sensible

part I believe I am on good terms." This was amply proved some

four years later, when it became necessary to appoint an engineer to

the Ellesmere Canal, on which occasion the magistrates, who were

mainly the promoters of the undertaking, almost unanimously

solicited their Surveyor to accept the office.

Indeed, Telford had become a general favourite in the county.

He was cheerful and cordial in his manner, though somewhat brusque.

Though now thirty-five years old, he had not lost the humorousness

which had procured for him the sobriquet of "Laughing Tam." He

laughed at his own jokes as well as at others. He was spoken

of as jolly—a word then much more rarely as well as more choicely

used than it is now. Yet he had a manly spirit, and was very

jealous of his independence. All this made him none the less

liked by free-minded men. Speaking of the friendly support

which he had throughout received from Mr. Pulteney, he said, "His

good opinion has always been a great satisfaction to me; and the

more so, as it has neither been obtained nor preserved by deceit,

cringing, nor flattery. On the contrary, I believe I am almost

the only man that speaks out fairly to him, and who contradicts him

the most. In fact, between us, we sometimes quarrel like tinkers;

but I hold my ground, and when he sees I am right he quietly gives

in."

Although Mr. Pulteney's influence had no doubt assisted

Telford in obtaining the appointment of surveyor, it had nothing to

do with the unsolicited invitation which now emanated from the

county gentlemen. Telford was not even a candidate for the

engineership, and had not dreamt of offering himself, so that the

proposal came upon him entirely by surprise. Though he

admitted he had self-confidence, he frankly confessed that he had

not a sufficient amount of it to justify him in aspiring to the

office of engineer to one of the most important undertakings of the

day. The following is his own account of the circumstance:—

"My literary project [p.186-1]

is at present at a stand, and may be retarded for some time to come,

as I was last Monday appointed sole agent, architect, and engineer

to the canal which is projected to join the Mersey, the Dee, and the

Severn. It is the greatest work, I believe, now in hand in

this kingdom, and will not be completed for many years to come.

You will be surprised that I have not mentioned this to you before;

but the fact is that I had no idea of any such appointment until an

application was made to me by some of the leading gentlemen, and I

was appointed, though many others had made much interest for the

place. This will be a great and laborious undertaking, but the

line which it opens is vast and noble; and coming as the appointment

does in this honourable way, I thought it too great an opportunity

to be neglected, especially as I have stipulated for, and been

allowed, the privilege of carrying on my architectural profession.

The work will require great labour and exertions, but it is worthy

of them all." [p.186-2]

Telford's appointment was duly confirmed by the next general

meeting of the shareholders of the Ellesmere Canal. An attempt

was made to get up a party against him, but it failed. "I am

fortunate," he said, "in being on good terms with most of the

leading men, both of property and abilities; and on this occasion I

had the decided support of the great John Wilkinson, king of the

ironmasters, himself a host. I travelled in his carriage to

the meeting, and found him much disposed to be friendly." [p.187]

The salary at which Telford was engaged was £500. a year, out

of which he had to pay one clerk and one confidential foreman,

besides defraying his own travelling expenses. It would not

appear that after making these disbursements much would remain for

Telford's own labour; but in those days engineers were satisfied

with comparatively small pay, and did not dream of making large

fortunes.

Though Telford intended to continue his architectural

business, he decided to give up his county surveyorship and other

minor matters, which, he said, "give a great deal of very unpleasant

labour for little very little profit; in short they are like the

calls of a country surgeon." One part of his former business

which he did not give up was what related to the affairs of Mr.

Pulteney and Lady Bath, with whom he continued on intimate and

friendly terms. He incidentally mentions in one of his letters

a graceful and charming act of her Ladyship. On going into his

room one day he found that, before setting out for Buxton, she had

left upon his table a copy of Ferguson's 'Roman Republic,' in three

quarto volumes, superbly bound and gilt.

He now looked forward with anxiety to the commencement of the

canal, the execution of which would necessarily call for great

exertion on his part, as well as unremitting attention and industry;

"for," said he, " besides the actual labour which necessarily

attends so extensive a public work, there are contentions,

jealousies, and prejudices, stationed like gloomy sentinels from one

extremity of the line to the other. But, as I have heard my

mother say that an honest man might look the Devil in the face

without being afraid, so we must just trudge along in the old way."

[p.188]

――――♦―――― |