|

FOOTNOTES. |

|

PAGE |

|

|

p5. |

Brunetto Latini, the tutor of Dante, describes a

journey made by him from London to Oxford about the end of the

thirteenth century, resting by the way at Shirburn Castle. He

says, "Our journey from London to Oxford was, with some difficulty

and danger, made in two days; for the roads are bad, and we had to

climb hills of hazardous ascent, and which to descend are equally

perilous. We passed through many woods, considered here as

dangerous places, as they are infested with robbers, which indeed is

the case with most of the roads in England. This is a

circumstance connived at by the neighbouring barons, on

consideration of sharing in the booty, and of these robbers serving

as their protectors on all occasions, personally, and with the whole

strength of their hand. However, as our company was numerous,

we had less to fear. Accordingly, we arrived the first night

at Shirburn Castle, in the neighbourhood of Watlington, under the

chain of hills over which we passed at Stokenchurch." This

passage is given in Mr. Edward's work on 'Libraries' (p. 328), as

supplied to him by Lady Macclesfield. |

|

p.8 |

See Ogilby's 'Britannia Depicta,' the traveller's

ordinary guide-book between 1675 and 1717, as Bradshaw's Railway

Time-book is now. The Grand Duke Cosmo, in his 'Travels in

England in 1669,' speaks of the country between Northampton and

Oxford as for the most part unenclosed and uncultivated, abounding

in weeds. From Ogilby's fourth edition, published in 1749, it

appears that the roads in the midland and northern districts of

England were still, for the most part, entirely unenclosed. |

|

p.9 |

This ballad is so descriptive of the old roads of the

southwest of England that we are tempted to quote it at length. It

was written by the Rev. John Marriott, sometime vicar of Broadclist,

Devon; and Mr. Rowe, vicar of Creditors, says, in his

'Perambulation of Dartmoor,' that he can readily imagine the

identical lane near Broadclist, leading towards Poltemore, which

might have sat for the portrait.

|

In a Devonshire lane, as I trotted along

T'other day, much in want of a subject for song,

Thinks I to myself, half-inspired by the rain,

Sure marriage is much like a Devonshire lane.

In the first place 'tis long, and when once you are in

it,

It holds you as fast as a cage does a linnet;

For howe'er rough and dirty the road may be found,

Drive forward you must, there is no turning round.

But tho' 'tis so long, it is not very wide,

For two are the most that together can ride;

And e'en then, 'tis a chance but they get in a pother,

And jostle and cross and run foul of each other.

Oft poverty meets them with mendicant looks,

And care pushes by them with dirt-laden crooks;

And strife's grazing wheels try between them to pass,

And stubbornness blocks up the way on her ass.

Then the banks are so high, to the left hand and right,

That they shut up the beauties around them from sight;

And hence, you'll allow, 'tis an inference plain,

That marriage is just like a Devonshire lane.

But thinks I, too, these banks, within which we are

pent,

With bud, blossom, and berry, are richly besprent;

And the conjugal fence, which forbids us to roam,

Looks lovely, when deck'd with the comforts of home.

In the rock's gloomy crevice the bright holly grows;

The ivy waves fresh o'er the withering rose,

And the ever-green love of a virtuous wife

Soothes the roughness of care, cheers the winter of

life.

Then long be the journey, and narrow the way,

I'll rejoice that I've seldom a turnpike to pay ;

And what'er others say, be the last to complain,

Though marriage is just like a Devonshire lane.

|

|

|

p.11 |

'Iter Sussexiense.' By Dr. John Burton. |

|

p.13 |

'King Henry the Fourth' (Part I.), Act. II. Scene i. |

|

p.14 |

Part of

the riding road along which the Queen was accustomed to pass on

horseback between her palaces at Greenwich and Eltham is still in

existence, a little to the south of Morden College, Blackheath.

It winds irregularly through the fields, broad in some places, and

narrow in others. Probably it is very little different from what it

was when used as a royal road. It is now very appropriately

termed "Muddy Lane." |

|

p.15-1 |

'Dépêches de La Mothe F[enelon,' 8vo., 1838.

Vol. i. p.27. |

|

p.15-2 |

Nichols's 'Progresses,' vol. ii., 309. |

|

p.20 |

The title of Mace's tract (British Museum) is "The

Profit, Conveniency, and Pleasure for the whole nation: being a

short rational Discourse lately presented to his Majesty concerning

the Highways of England: their badness, the causes thereof, the

reasons of these causes, the impossibility of ever having them well

mended according to the old way of mending: but may most certainly

be done, and for ever so maintained (according to this NEW WAY)

substantially and with very much ease, &c., &c. Printed for

the public good in the year 1675." |

|

p.22-1 |

See 'Archæologia,' xx., pp. 443-76. |

|

p.22-2 |

"4th

May, 1714. Morning: we dined at Grantham, had the annual

solemnity (this being the first time the coach passed the road in

May), and the coachman and horses being decked with ribbons and

flowers, the town music and young people in couples before us: we

lodged at Stamford, a scurvy, dear town. 5th May: had other

passengers, which, though females, were more chargeable with wine

and brandy than the former part of the journey, wherein we had

neither; but the next day we gave them leave to treat themselves."—Thoresby's

'Diary,' vol. ii., 207. |

|

p.22-3 |

"May 22,

1708. At York. Rose between three and four, the coach

being hasted by Captain Crone (whose company we had) upon the

Queen's business, that we got to Leeds by noon; blessed be God for

mercies to me and my poor family."—Thoresby's 'Diary,' vol. ii., 7. |

|

p.23-1 |

Thoresby's ' Diary,' vol. i., 295. |

|

p.23-2 |

Waylen's 'Marlborough.' |

|

p.24 |

Reprinted in the 'Harleian Miscellany,' vol. viii.,

p.547. Supposed to have been written by one John Gressot, of

the Charterhouse. |

|

p.25 |

There were other publications of the time as absurd

(viewed by the light of the present day) as Gressot's. Thus,

"A Country Tradesman," addressing the public in 1678, in a pamphlet

entitled 'The Ancient Trades decayed, repaired again,—wherein are

declared the several abuses that have utterly impaired all the

ancient trades in the Kingdom,' urges that the chief cause of the

evil had been the setting up of Stage-coaches some twenty years

before. Besides the reasons for suppressing them set forth in

the treatise referred to in the text, he says, "Were it not for them

(the Stagecoaches), there would be more Wine, Beer, and Ale, drunk

in the Inns than is now, which would be a means to augment the

King's Custom and Excise. Furthermore they hinder the breed of

horses in this kingdom [the same argument was used against

Railways], because many would be necessitated to keep a good horse

that keeps none now. Seeing, then, that there are few that are

gainers by them, and that they are against the common and general

good of the Nation, and are only a conveniency to some that have

occasion to go to London, who might still have the same wages as

before these coaches were in use, therefore there is good reason

they should be suppressed. Not but that it may be lawful

to hire a coach upon occasion, but that it should be unlawful only

to keep a coach that should go long journeys constantly from one

stage or place to another upon certain days of the week as they do

now.'—p. 27. |

|

p.28 |

Roberts's 'Social History of the Southern Counties,'

p. 494—Little more than a century ago, we find the following

advertisement of a Newcastle flying coach:—"May 9, 1734.—A coach

will set out towards the end of next week for London, or any place

on the road. To be performed in nine days,—being three days

sooner than any other coach that travels the road; for which purpose

eight stout horses are stationed at proper distances." |

|

p.29 |

In 1710 a Manchester manufacturer taking his family

up to London, hired a coach for the whole way, which, in the then

state of the roads, must have made it a journey of probably eight or

ten days. And, in 1742, the system of travelling had so little

improved, that a lady, wanting to come with her niece from Worcester

to Manchester, wrote to a friend in the latter place to send her a

hired coach, because the man knew the road, having brought from

thence a family some time before."—Aikin's 'Manchester.' |

|

p.32 |

Lord Campbell mentions the remarkable circumstance

that Popham, afterwards Lord Chief Justice in the reign of

Elizabeth, took to the road in early life, and robbed travellers on

Gad's Hill. Highway robbery could not, however, have been

considered a very ignominious pursuit at that time, as during

Popham's youth a statute was made by which, on a first conviction

for robbery, a peer of the realm or lord of parliament was entitled

to have benefit of clergy, "though he cannot read!" What is

still more extraordinary is, that Popham is supposed to have

continued in his course as a highwayman even after he was called to

the Bar. This seems to have

been quite notorious, for when he was made Serjeant the wags

reported that he served up some wine destined for an Alderman of

London, which be had intercepted on its way from

Southampton.—Aubrey, iii., 492.— Campbell's 'Chief Justices,' i.,

210. |

|

p.33-1 |

'Travels of Cosmo the Third, Grand Duke of Tuscany,'

p. 147. |

|

p.33-2 |

"It is as common a custom, as a cunning policie in

thieves, to place chamberlains in such great inns where cloathiers

and graziers do lye; and by their large bribes to infect others, who

were not of their own preferring; who noting your purses when you

draw them, they'l gripe your cloak-bags, and feel the weight, and so

inform the master thieves of what they think, and not those alone,

but the Host himself is oft as base as they, if it be left in charge

with them all night; he to his roaring guests either gives item, or

shews the purse itself, who spend liberally, in hope of a speedie

recruit." See 'A Brief yet Notable Discovery of

Housebreakers,' &c., 1659. See also 'Street Robberies

Considered; a Warning for Housekeepers,' 1676; 'Hanging not

Punishment Enough,' 1701 ; &c. |

|

p.35 |

The food of London was then principally brought to

town in panniers. The population being comparatively small,

the feeding of London was still practicable in this way; besides,

the city always possessed the great advantage of the Thames, which

secured a supply of food by sea. In 'The Grand Concern of

England Explained,' it is stated that the hay, straw, beans, peas,

and oats, used in London, were principally raised within a circuit

of twenty miles of the metropolis; but large quantities were also

brought from Henley-on-Thames and other western parts, as well as

from below Gravesend by water; and many ships laden with beans came

from Hull, and with oats from Lynn and Boston. |

|

p.38 |

'Loides and Elmete,' by T. D. Whitaker, LL.D., 1816,

p. 81. Notwithstanding its dangers, Dr. Whitaker seems to have

been of opinion that the old mode of travelling was even safer than

that which immediately followed it; "Under the old state of roads

and manners," he says, "it was impossible that more than one death

could happen at once; what, by any possibility, could take place

analogous to a race betwixt two stage-coaches, in which the lives of

thirty or forty distressed and helpless individuals are at the mercy

of two intoxicated brutes?" |

|

p.39 |

In the curious collection of old coins at the

Guildhall there are several halfpenny tokens issued by the

proprietors of inns bearing the sign of the pack-horse. Some

of these would indicate that pack-horses were kept for hire.

We append a couple of illustrations of these curious old coins. |

|

p.42 |

'Three

Years' Travels in England, Scotland, and Wales.' By James

Brome, M.A., Rector of Cheriton, Kent. London, 1726. |

|

p.43 |

The treatment the stranger received was often very

rude. When William Hutton, of Birmingham, accompanied by

another gentleman, went to view the field of Bosworth, in 770, "the

inhabitants," he says, "set their dogs at us in the street, merely

because we were strangers. Human figures not their own are

seldom seen in these inhospitable regions. Surrounded with

impassable roads, no intercourse with man to humanise the mind, nor

commerce to smooth their rugged manners, they continue the boors of

Nature." In certain villages in Lancashire and Yorkshire, not

very remote from large towns, the appearance of a stranger, down to

a comparatively recent period, excited a similar commotion amongst

the villagers, and the word would pass from door to door, "Dost knaw

'im?" "Naya." "Is 'e straunger?" "Ey for sewer." "Then

paus' 'im—'Eave a duck [stone] at 'im—Fettle 'im!" And the "straunger"

would straightway find the "ducks" flying about his head, and be

glad to make his escape from the village with his life. |

|

p.45 |

Scatcherd, 'History of Morley.' |

|

p.48 |

Murray's 'Handbook of Surrey, Hants, and Isle of

Wight,' 168. |

|

p.49 |

Whitaker's 'History of Craven.' |

|

p.50 |

Scatcherd's 'History of Morley,' 226. |

|

p.51 |

Vixen Tor is the name of this singular-looking rock.

But it is proper to add, that its appearance is probably accidental,

the head of the Sphynx being produced by the three angular blocks of

rock seen in profile. Mr. Borlase, however, in his

'Antiquities of Cornwall,' expresses the opinion that the

rock-basins on the summit of the rock were used by the Druids for

purposes connected with their religious ceremonies. |

|

p.52 |

The provisioning of London, now grown so populous,

would be almost impossible but for the perfect system of roads now

converging on it from all parts. In early times, London, like

country places, had to lay in its stock of salt-provisions against

winter, drawing its supplies of vegetables from the country within

easy reach of the capital. Hence the London market-gardeners

petitioned against the extension of turnpike-roads about a century

ago, as they afterwards petitioned against the extension of

railways, fearing lest their trade should be destroyed by the

competition of country-grown cabbages. But the extension of

the roads had become a matter of absolute necessity, in order to

feed the huge and ever-increasing mouth of the Great Metropolis, the

population of which has grown in about two centuries from four

hundred thousand to three millions. This enormous population

has, perhaps, never at any time more than a fortnight's supply of

food in stock, and most families not more than a few days; yet no

one ever entertains the slightest apprehension of a failure in the

supply, or even of a variation in the price from day to day in

consequence of any possible shortcoming. That this should be

so, would be one of the most surprising things in the history of

modern London, but that it is sufficiently accounted for by the

magnificent system of roads, canals, and railways, which connect it

with the remotest corners of the kingdom. Modern London is

mainly fed by steam. The Express Meat-Train, which runs

nightly from Aberdeen to London, drawn by two engines, and makes the

journey in twenty-four hours, is but a single illustration of the

rapid and certain method by which modern London is fed. The

north Highlands of Scotland have thus, by means of railways, become

grazing-grounds for the metropolis. Express fish-trains from

Dunbar and Eye-mouth (Smeaton's harbours), augmented by fish-trucks

from Cullercoats and Tynemouth on the Northumberland coast, and from

Redcar, Whitby, and Scarborough on the Yorkshire coast, also arrive

in London every morning. And what with steam-vessels bearing

cattle, and meat and fish arriving by sea, and canal-boats laden

with potatoes from inland, and railway-vans laden with butter and

milk drawn from a wide circuit of country, and road-vans piled high

with vegetables within easy drive of Covent Garden, the Great Mouth

is thus from day to day regularly, satisfactorily, and expeditiously

filled. |

|

p.53 |

The white witches are kindly disposed, the black cast

the "evil eye," and the grey are consulted for the discovery of

theft, &c. |

|

p.55 |

See 'The Devonshire Lane,' above quoted, note

to p. 9. |

|

p.56 |

Willow saplings, crooked and dried in the required

form. |

|

p.58 |

'Farmer's Magazine,' 1803. No. xiii. p.101. |

|

p.60 |

Bad although the condition of Scotland was at the

beginning of last century, there were many who believed that it

would be made worse by the carrying of the Act of Union. The

Earl of Wigton was one of these. Possessing large estates in

the county of Stirling, and desirous of taking every precaution

against what he supposed to be impending ruin, he made over to his

tenants, on condition that they continued to pay him their then low

rents, his extensive estates in the parishes of Denny, Kirkintulloch,

and Cumbernauld, retaining only a few fields round the family

mansion ['Farmer's Magazine,' 1808, No. xxxiv. p.193].

Fletcher of Saltoun also feared the ruinous results of the Union,

though he was less precipitate in his conduct than the Earl of

Wigton. We need scarcely say how entirely such apprehensions

were falsified by the actual results. |

|

p.61 |

'Fletcher's Political Works,' London, 1737, p.149.

As the population of Scotland was then only about 1,200,000, the

beggars of the country, according to the above account, must have

constituted about one-sixth of the whole community. |

|

p.62 |

Act 39th George III. c. 56. See 'Lord

Cockburn's Memorials,' pp. 76-9. As not many persons may be

aware how recent has been the abolition of slavery in Britain, the

author of this book may mention the fact, that he personally knew a

man who had been "born a slave in Scotland," to use his own words,

and lived to tell it. He had resisted being transferred to

another owner on the sale of the estate to which he was "bound," and

refused to "go below," on which he was imprisoned in Edinburgh gaol,

where he lay for a considerable time. The case excited much

interest, and probably had some effect in leading to the alteration

in the law relating to colliers and salters which shortly after

followed. |

|

p.63 |

See 'Autobiography of Dr. Alexander Carlyle,'

passim. |

|

p.64-1 |

'Farmer's Magazine,' June, 1811, No. xlvi. p. 155. |

|

p.64-2 |

See Buchan Hepburn's 'General View of the Agriculture

and Economy of East Lothian,' 1794, p.95. |

|

p.65-1 |

Letter of John Maxwell, in Appendix to Macdiarmid's

'Picture of Dumfries,' 1823. |

|

p.65-2 |

Robertson's 'Rural Recollections,' p.38. |

|

p.68 |

Very little was known of the geography of the

Highlands down to the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The principal information on the subject being derived from Danish

materials. It appears, however, that in 1608, one Timothy

Pont, a young man without fortune or patronage, formed the singular

resolution of travelling over the whole of Scotland, with the sole

view of informing himself as to the geography of the country, and he

persevered to the end of his task through every kind of difficulty;

exploring all the islands with the zeal of a missionary, though

often pillaged and stript of everything by the then barbarous

inhabitants. The enterprising youth received no recognition

nor reward for his exertions, and he died in obscurity, leaving his

maps and papers to his heirs. Fortunately, James I. heard of

the existence of Pont's papers, and purchased them for public use.

They lay, however, unused for a long time in the offices of the

Scotch Court of Chancery, until they were at length brought to light

by Mr. Robert Gordon, of Straloch, who made them the basis of the

first map of Scotland having any pretensions to accuracy that was

ever published. |

|

p.69 |

Mr. Grant, of Corrymorry, used to relate that his

father, when speaking of the Rebellion of 1745, always insisted that

a rising in the Highlands was absolutely necessary to give

employment to the numerous bands of lawless and idle young men who

infested every property.—Anderson's 'Highlands and Islands of

Scotland,' p.432. |

|

p.71-1 |

'Lord Hailes's Annals,' i., 379. |

|

p.71-2 |

Professor Innes's 'Sketches of Early Scottish

History.' The principal ancient bridges in Scotland were those

over the Tay at Perth (erected in the thirteenth century); over the

Esk at Brechin and Marykirk; over the Dee at Kincardine, O'Neil, and

Aberdeen; over the Don, near the same city; over the Spey at Orkhill;

over the Clyde at Glasgow; over the Forth at Stirling; and over the

Tyne at Haddington. |

|

p.73 |

Lady Luxborough, in a letter to Shenstone the poet,

in 1749, says,—"A Birmingham coach is newly established to our great

emolument. Would it not be a good scheme (this dirty weather,

when riding is no more a pleasure) for you to come some Monday in

the said stage-coach from Birmingham to breakfast at Barrells, (for

they always breakfast at Henley); and on the Saturday following it

would convey you back to Birmingham, unless you would stay longer,

which would be better still, and equally easy; for the stage goes

every week the same road. It breakfasts at Henley, and lies at

Chipping Horton; goes early next day to Oxford, stays there all day

and night, and gets on the third day to London ; which from

Birmingham at this season is firefly well, considering how long they

are at Oxford; and it is much more agreeable as to the country than

the Warwick way was." |

|

p.74 |

We may incidentally mention three other journeys

south by future Lords Chancellors. Mansfield rode up from

Scotland to London when a boy, taking two months to make the journey

on his pony. Wedderburn's journey by coach from Edinburgh to

London, in 1757, occupied him six days. "When I first reached

London," said the late Lord Campbell, "I performed the same journey

in three nights and two days, Mr. Palmer's mail-coaches being then

established; but this swift travelling was considered dangerous as

well as wonderful, and I was gravely advised to stay a day at York,

as several passengers who had gone through without stopping had died

of apoplexy from the rapidity of the motion!" |

|

p.79 |

C. H. Moritz: 'Reise eines Deutschen in England im

Jahr, 1782.' Berlin, 1783. |

|

p.80 |

Arthur Young's 'Six Weeks' Tour through the Southern

Counties of England and Wales.' 2nd ed., 1769, pp. 88-9. |

|

p.81 |

'Six Weeks' Tour in the Southern Counties of England

and Wales,' pp. 153-5. The roads all over South Wales were

equally bad down to the beginning of the present century. At

Halfway, near Trecastle, in Breconshire, South Wales, a small

obelisk is still to be seen, which was erected to commemorate the

turn over and destruction of the mail coach over a steep of 130

feet; the driver and passengers escaping unhurt. |

|

p.82 |

'A Six Months' Tour through the North of England,'

vol. iv., p.431. |

|

p.83 |

Letter to Wyatt, October 5th, 1787, MS. |

|

p.84-1 |

Act 15 Car. I I., c. 1. |

|

p.84-2 |

The preamble of the Act recites that "The ancient

highway and post-road leading from London to York, and so into

Scotland, and likewise from London into Lincolnshire, lieth for many

miles in the counties of Hertford, Cambridge, and Huntingdon, in

many of which places the road, by reason of the great and many loads

which are weekly drawn in waggons through the said places, as well

as by reason of the great trade of barley and malt that cometh to

Ware, and so is conveyed by water to the city of London, as well as

other carriages, both from the north parts as also from the city of

Norwich, St. Edmondsbury, and the town of Cambridge, to London, is

very ruinous, and become almost impassable, insomuch that it is

become very dangerous to all his Majesty's liege people that pass

that way," &c. |

|

p.85 |

Down to the year 1756, Newcastle and Carlisle were

only connected by a bridle way. In that year, Marshal Wade

employed his army to construct a road by way of Harlaw and

Cholterford, following for thirty miles the line of the old Roman

Wall, the materials of which he used to construct his "agger " and

culverts. This was long after known as "the military road." |

|

p.87-1 |

The Blandford waggoner said, "Roads had but one

object—for waggon-driving. He required but four-foot width in

a lane, and all the rest might go to the devil.' He added,

"The gentry ought to stay at home, and be d――d, and not run

gossiping up and down the country."—Roberts's 'Social History of the

Southern Counties.' |

|

p.87-2 |

'Gentleman's Magazine ' for December, 1752. |

|

p.88 |

Adam Smith's 'Wealth of Nations,' book i., chap. xi.,

part i. |

|

p.90 |

Ed.—also known as John Metcalfe.

Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. |

|

p.103 |

Ed.—Field Marshall George Wade (1673-1748).

Smiles's text at this point gives the impression that Wade was the

battlefield commander at Falkirk; this was not the case. Wade,

by then over seventy and in poor health, retired from active service

in January 1746 to be replaced by Lieutenant-General Hawley,

whose disdain for the Scots resulted in a further significant defeat

for the government forces. Despite a distinguished military

career—the 1745 uprising apart—Wade is probably remembered today for

his military engineering works (roads, bridges, barracks and

fortifications) in suppression of the Highlands. Source:

(principally) the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. |

|

p.114 |

'Observations on Blindness and on the Employment of

the other Senses to supply the Loss of Sight.' By Mr.

Bew.—Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of

Manchester, vol. i., pp. 172-174. Paper read 17th April, 1782. |

|

p.119 |

The pillar was erected by Squire Dashwood in 1751;

the lantern on its summit was regularly lighted till 1788, and

occasionally till 1808, when it was thrown down and never replaced.

The Earl of Buckingham afterwards mounted a statue of George III. on

the top. |

|

p.121-1 |

Since the appearance of the first edition of this

book, a correspondent has informed us that there is another

lighthouse within 24 miles of London, not unlike that on Lincoln

Heath. It is situated a little to the south-east of the Woking

Station of the South-Western Railway, and is popularly known as

"Woking Monument." It stands on the verge of Woking Heath,

which is a continuation of the vast tract of heath land which

extends in one direction as far as Bagshot. The tradition

among the inhabitants is, that one of the kings of England was wont

to hunt in the neighbourhood, when a fire was lighted up in the

beacon to guide him in case he should be belated; but the

probability is, that it was erected like that on Lincoln Heath, for

the guidance of ordinary wayfarers at night. |

|

p.121-2 |

'Journal of the Agricultural Society of England,

1843.' |

|

p.129 |

Sir Walter Scott, in his notes to the 'Minstrelsy of

the Scottish Border,' says that the common people of the high parts

of Liddlesdale and the country adjacent to this day hold the memory

of Johnnie Armstrong in very high respect. |

|

p.130 |

It was long before the Reformation flowed into the

secluded valley of the Esk; but when it did, the energy of the

Borderers displayed itself in the extreme form of their opposition

to the old religion. The Eskdale people became as resolute in

their covenanting as they had before been in their freebooting; the

moorland fastnesses of the moss-troopers becoming the haunts of the

persecuted ministers in the reign of the second James. A

little above Langholm is a hill known as "Peden's View," and the

well in the green hollow at its foot is still called "Peden's

Well"—that place having been the haunt of Alexander Peden, the

"prophet." His hiding-place was among the alder-bushes in the

hollow, while from the hill-top he could look up the valley, and see

whether the Johnstones of Wester Hall were coming. Quite at

the head of the same valley, at a place called Craighaugh, on

Eskdale Muir, one Hislop, a young covenanter, was shot by

Johnstone's men, and buried where he fell; a gray slabstone still

marking the place of his rest. Since that time, however, quiet

has reigned in Eskdale, and its small population have gone about

their daily industry from one generation to another in peace.

Yet though secluded and apparently shut out by the surrounding hills

from the outer world, there is not a throb of the nation's heart but

pulsates along the valley; and when the author visited it some years

since, he found that a wave of the great Volunteer movement had

flowed into Eskdale; and the "lads of Langholm" were drilling and

marching under their chief, young Mr. Malcolm of the Burnfoot, with

even more zeal than in the populous towns and cities of the south. |

|

p.132 |

The names of the families in the valley remain very

nearly the same as they were three hundred years ago—the Johnstones,

Littles, Scotts, and Beatties prevailing above Langholm; and the

Armstrongs, Bells, Irwins, and Graemes lower down towards Canobie

and Netherby. It is interesting to find that Sir David

Lindesay, in his curious drama published in 'Pinkerton's Scottish

Poems' (vol. ii., p. 156), gives these as among the names of the

Borderers some three hundred years since. One Common Thift,

when sentenced to condign punishment, thus remembers his Border

friends in his dying speech:—

"Adew! my brother Annan thieves,

That holpit me in my mischeivis;

Adew! Grossars, Niksonis, and Bells,

Oft have we fairne owrthreuch the fells;

Adew! Robsons, Howis, and Pylis,

That in our craft her mony wilis;

Littlis, Trumbells, and Armestranges;

Baileowes, Erewynis, and Elwandis,

Speedy of flicht, and slicht of handis;

The Scotts of Eisdale, and the Gramis,

I haf na time to tell your nameis." |

Telford, or Telfer, is an old name in the same neighbourhood, commemorated

in the well known border ballad of 'Jamie Telfer of the fair Dodhead.'

Sir W. Scott says, in the 'Minstrelsy,' that "there is still a

family of Telfers, residing near Langholm, who pretend to derive

their descent from the Telfers of the Dodhead." A member of

the family of "Pylis" above mentioned, is said to have migrated from

Ecclefechan southward to Blackburn, and there founded the celebrated

Peel family. |

|

p.136 |

We were informed in the valley that about the time of

Telford's birth there were only two tea-kettles in the whole parish

of Westerkirk, one of which was in the house of Sir James Johnstone

of Wester Hall, and the other at "The Burn," the residence of Mr.

Pasley, grandfather of General Sir Charles Pasley. |

|

p.144 |

In his 'Epistle to Mr. Walter Ruddiman,' first

published in 'Ruddiman's Weekly Magazine,' in 1779, occur the

following lines addressed to Burns, in which Telford incidentally

sketches himself at the time, and hints at his own subsequent

meritorious career:—

|

"Nor pass the tentie curious lad,

Who o'er the ingle hangs his head,

And begs of neighbours books to read;

For hence arise

Thy country's sons, who far are spread,

Baith bold and wise." |

|

|

p.148 |

The 'Poetical Museum,' Hawick, p. 267.

'Eskdale' was afterwards reprinted by Telford when living at

Shrewsbury, when he added a few lines by way of conclusion.

The poem describes very pleasantly the fine pastoral scenery of the

district:—

"Deep 'mid the green sequester'd glens below,

Where murmuring streams among the alders flow,

Where flowery meadows down their margins spread,

And the brown hamlet lifts its humble head—

There, round his little fields, the peasant strays,

And sees his flock along the mountain graze;

And, while the gale breathes o'er his ripening grain,

And soft repeats his upland shepherd's strain,

And western suns with yellow radiance play,

And gild his straw-roof'd cottage with their ray,

Feels Nature's love his throbbing heart employ,

Nor envies towns their artificial joy." |

The features of the valley are very fairly described. Its

early history is then rapidly sketched; next its period of border

strife, at length happily allayed by the union of the kingdoms,

under which the Johnstones, Pasleys, and others, men of Eskdale,

achieve honour and fame. Nor did he forget to mention

Armstrong, the author of the 'Art of Preserving Health,' son of the

minister of Castleton, a few miles east of Westerkirk; and Mickle,

the translator of the 'Lusiad,' whose father was minister of the

parish of Langholm; both of whom Telford took a natural pride in as

native poets of Eskdale. |

|

p.154 |

Robert and John Adam were architects of considerable

repute in their day. Among their London erections were the

Adelphi Buildings, in the Strand; Lansdowne House, in Berkeley

Square; Caen Wood House, near Hampstead (Lord Mansfield's); Portland

Place, Regent's Park; and numerous West End streets and mansions.

The screen of the Admiralty and the ornaments of Draper's Hall were

also designed by them. |

|

p.155 |

Long after Telford had become famous, he was passing

over Waterloo Bridge one day with a friend, when, pointing to some

finely-cut stones in the corner nearest the bridge, he said: "You

see those stones there; forty years since I hewed and laid them,

when working on that building as a common mason." |

|

p.157-1 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated London,

July, 1783. |

|

p.157-2 |

Mr., afterwards Sir William, Pulteney, was the second

son of Sir James Johnstone, of Wester Hall, and assumed the name of

Pulteney, on his marriage to Miss Pulteney, niece of the Earl of

Bath and of General Pulteney, by whom he succeeded to a large

fortune. He afterwards succeeded to the baronetcy of his elder

brother James, who died without issue in 1797. Sir William

Pulteney represented Cromarty, and afterwards Shrewsbury, where he

usually resided, in seven successive Parliaments. He was a

great patron of Telford's, as we shall afterwards find. |

|

p.159 |

Letter to Andrew Little, Langholm, dated Portsmouth,

July 23rd, 1784. |

|

p.160 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Portsmouth Dockyard, Feb. 1, 1786. |

|

p.161 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Portsmouth Dockyard, Feb. 1, 1786. |

|

p.164 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shewsbury Castle, 21st Feb., 1788. |

|

p.165 |

This practice of noting down information, the result

of reading and observation, was continued by Mr. Telford until the

close of his life; his last pocket memorandum book, containing a

large amount of valuable information on mechanical subjects—a sort

of engineer's vade mecum—being printed in the appendix to the

4to 'Life of Telford' published by his executors in 1838, pp.

663-90. |

|

p.166-1 |

A medical man, a native of Eskdale, of great promise,

who died comparatively young. |

|

p.166-2 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm. |

|

p.167 |

It would occupy unnecessary space to cite these

poems. The following, from the verses in memory of William

Telford, relates to schoolboy days. After alluding to the

lofty Fell Hills, which formed part of the sheep farm of his

deceased friend's father, the poet goes on to say:—

|

"There 'mongst those rocks I'll form a rural seat,

And plant some ivy with its moss compleat;

I'll benches form of fragments from the stone,

Which, nicely, pois'd, was by our hands o'erthrown,—

A simple frolic, but now dear to me,

Because, my Telford, 'twas performed with thee.

There, in the centre, sacred to his name,

I'll place an altar, where the lambent flame

Shall yearly rise, and every youth shall join

The willing voice, and sing the enraptured line.

But we, my friend, will often steal away

To this lone seat, and quiet pass the day;

Here oft recall the pleasing scenes we knew

In early youth, when every scene was new,

When rural happiness our moments blest,

And joys untainted rose in every breast." |

|

|

p.168 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated 16th

July, 1788. |

|

p.169-1 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated 16th

July, 1788. |

|

p.169-2 |

Ibid. |

|

p.171 |

The discovery formed the subject of a paper read

before the Society of Antiquaries in London on the 7th of May, 1789,

published in the 'Archæologia,' together with a drawing of the

remains supplied by Mr. Telford. |

|

p.172-1 |

An Eskdale crony. His son, Colonel Josias

Stewart, rose to eminence in the East India Company's service,

having been for many years Resident at Gwalior and Indore. |

|

p.172-2 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated 3rd

Sept. 1788. |

|

p.173 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 8th October, 1789. |

|

p.175 |

It was then under seventeen millions sterling, or

about a fourth of what it is now. |

|

p.176-1 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated 28th

July, 1791. Notwithstanding the theoretical ruin of England

which pressed so heavy on his mind at this time, we find Telford

strongly recommending his correspondent to send any good wrights he

could find in his neighbourhood to Bath, where they would be enabled

to earn twenty shillings or a guinea a week at piece-work—the wages

paid at Langholm for similar work being only about half those

amounts. |

|

p.176-2 |

The writer of a memoir of Telford, in the 'Encyclopedia

Britannica,' says:—"Andrew Little kept a private and very small

school at Langholm. Telford did not neglect to send him a copy

of Paine's 'Rights of Man;' and as he was totally blind, he employed

one of his scholars to read it in the evenings. Mr. Little had

received an academical education before he lost his sight and, aided

by a memory of uncommon powers, he taught the classics, and

particularly Greek, with much higher reputation than any other

schoolmaster within a pretty extensive circuit. Two of his

pupils read all the Iliad, and all or the greater part of Sophocles.

After hearing a long sentence of Greek or Latin distinctly recited,

he could generally construe and translate it with little or no

hesitation. He was always much gratified by Telford's visits,

which were not infrequent, to his native district." |

|

p.182 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 10th March, 1793. |

|

p.184 |

Referring to the burning of Dr. Priestley's library. |

|

p.186-1 |

The preparation of some translations from Buchanan

which he had contemplated. |

|

p.186-2 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 29th September, 1793. |

|

p.187 |

John Wilkinson and his brother William were the first

of the great class of ironmasters. They possessed iron forges

at Bersham near Chester, at Bradley, Brimbo, Merthyr Tydvil, and

other places; and became by far the largest iron manufacturers of

their day. For notice of them see 'Lives of Boulton and Watt,'

p. 184. |

|

p.188 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 3rd November, 1793. |

|

p.190 |

The Ellesmere Canal now pays about 4 per cent.

dividend. |

|

p.192 |

'A General History of Inland Navigation, Foreign and

Domestic,' &c. By J. Phillips. Fourth edition. London, 1803. |

|

p.194 |

Telford himself thus modestly describes the merit of

this original contrivance: "Previously to this time such canal

aqueducts had been uniformly made to retain the water necessary for

navigation by means of puddled earth retained by masonry; and in

order to obtain sufficient breadth for this superstructure, the

masonry of the piers, abutments, and arches was of massive strength;

and after all this expense, and every imaginable precaution, the

frosts, by swelling the moist puddle, frequently created fissures,

which burst the masonry, and suffered the water to escape—nay,

sometimes actually threw down the aqueducts; instances of this kind

having occurred even in the works of the justly celebrated Brindley.

It was evident that the increased pressure of the puddled earth was

the chief cause of such failures: I therefore had recourse to the

following scheme in order to avoid using it. The spandrels of

the stone arches were constructed with longitudinal walls, instead

of being filled in with earth (as at Kirkcudbright Bridge), and

across these the canal bottom was formed by cast iron plates at each

side, infixed in square stone masonry. These bottom plates had

flanches on their edges, and were secured by nuts and screws at

every juncture. The sides of the canal were made waterproof by

ashlar masonry, backed with hard burnt bricks laid in Parker's

cement, on the outside of which was rubble stone work, like the rest

of the aqueduct. The towing path had a thin bed of clay under

the gravel, and its outer edge was protected by an iron railing.

The width of the water-way is 11 feet; of the masonry on each side,

5 feet 6 inches; and the depth of the water in the canal, 5 feet.

By this mode of construction the quantity of masonry is much

diminished, and the iron bottom plate forms a continuous tie,

preventing the side-walls from separation by lateral pressure of the

contained water."—'Life of Telford,' p.40. |

|

p.199 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 13th March, 1795. |

|

p.200-1 |

Matthew Davidson had been Telford's fellow workman at

Langholm, and was reckoned an excellent mason. He died at

Inverness, where he had a situation on the Caledonian Canal. |

|

p.200-2 |

Mr. Hughes, C.E., in his 'Memoir of William Jessop,'

published in 'Weale's Quarterly Papers on Engineering,' points out

the bold and original idea here adopted, of constructing a

watertight trough of cast-iron, in which the water of the canal was

to be carried over the valleys, instead of an immense puddled

trough, in accordance with the practice at that time in use; and he

adds, "the immense importance of this improvement on the old

practice is apt to be lost sight of at the present day by those who

overlook the enormous size and strength of masonry which would have

been required to support a puddled channel at the height of 120

feet." Mr. Hughes, however, claims for Mr. Jessop the merit of

having suggested the employment of iron, though, in our opinion,

without sufficient reason. Mr. Jessop was, no doubt, consulted

by Mr. Telford on the subject; but the whole details of the design,

as well as the suggestion of the use of iron (as admitted by Mr.

Hughes himself), and the execution of the entire works, rested with

the acting engineer. This is borne out by the report published

by the Company immediately after the formal opening of the Canal in

1805, in which they state: "Having now detailed the particulars

relative to the Canal, and the circumstances of the concern, the

committee, in concluding their report, think it but justice due to

Mr. Telford to state that the works have been planned with great

skill and science, and executed with much economy and stability,

doing him, as well as those employed by him, infinite credit.

" (Signed) BRIDGEWATER." |

|

p.202 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 16th Sept., 1794. |

|

p.203 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 16th Sept., 1794. |

|

p.205 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated Salop,

20th Aug., 1797. |

|

p.210 |

'Encyclopedia Britannica,' 8th ed. Art. "Iron

Bridges." |

|

p.211 |

According to the statement made in the petition drawn

by Paine, excise officers were then (1772) paid only 1s. 9¼d. a day. |

|

p.212 |

In England, Paine took out a patent for his Iron

Bridge in 1788.—Specification of Patents (old law) No. 1667. |

|

p.216 |

The following are further details "Each of the main

ribs of the flat arch consists of three pieces, and at each junction

they are secured by a grated plate, which connects all the parallel

ribs together into one frame. The back of each abutment is in

a wedge-shape, so as to throw off laterally much of the pressure of

the earth. Under the bridge is a towing path on each side of

the river. The bridge was cast in an admirable manner by the

Coalbrookdale iron-masters in the year 1796, under contract with the

county magistrates. The total cost was £6,034. 13s. 3d." |

|

p.217 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Shrewsbury, 18th March, 1795. |

|

p.218 |

Douglas was first mentioned to Telford, in a letter

from Mr. Pasley, as a young man, a native of Bigholmes, Eskdale, who

had, after serving his time there as a mechanic, emigrated to

America, where he showed such proofs of mechanical genius that he

attracted the notice of Mr. Liston, the British Minister, who paid

his expenses home to England, that his services might not be lost to

his country, and at the same time gave him a letter of introduction

to the Society of Arts in London. Telford, in a letter to

Andrew Little, dated 4th December, 1797, expressed a desire "to know

more of this Eskdale Archimedes." Shortly after, we find

Douglas mentioned as having invented a brick machine, a

shearing-machine, and a ball for destroying the rigging of ships;

for the two former of which he secured patents. He afterwards

settled in France, where he introduced machinery for the improved

manufacture of woollen cloth; and being patronised by the

Government, he succeeded in realising considerable wealth, which,

however, he did not live to enjoy. |

|

p.219 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated London,

13th May, 1800. |

|

p.221 |

The evidence is fairly set forth in 'Cresy's

Encyclopedia of Civil Engineering,' p. 475. |

|

p.223 |

Article on Iron Bridges, in the 'Encyclopedia

Britannica,' Edinburgh, 1857. |

|

p.225 |

His foreman of masons at Bewdley Bridge, and

afterwards Bridge assistant in numerous important works. |

|

p.226 |

The work is thus described in Robert Chambers's

'Picture of Scotland':—"Opposite Compston there is a magnificent new

bridge over the Dee. It consists of a single arch, the span of

which is 112 feet; and it is built of vast blocks of freestone

brought from the Isle of Arran. The cost of this work was

somewhere about £7,000 sterling; and it may be mentioned, to the

honour of the Stewartry, that this sum was raised by the private

contributions of the gentlemen of the district. From

Tongueland Hill, in the immediate vicinity of the bridge, there is a

view well worthy of a painter's eye, and which is not inferior in

beauty and magnificence to any in Scotland." |

|

p.228-1 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated Salop,

13th July, 1799. |

|

p.228-2 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated

Liverpool, 9th September, 1800. |

|

p.228-3 |

Brodie was originally a blacksmith. He was a

man of much ingenuity and industry, and introduced many improvements

in iron work; he invented stoves for chimneys, ships' hearths, &c.

He had above a hundred men working in his London shop, besides

carrying on an iron work at Coalbrookdale. He afterwards

established a woollen manufactory near Peebles. |

|

p.230-1 |

Dated London, 14th April, 1802. |

|

p.230-2 |

Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated Salop,

30th November, 1799. |

|

p.233 |

'Romilly's

Autobiography,' ii. 22. |

|

p.234 |

'Statistical Account of Scotland,' iii. 185. |

|

p.235 |

The

cas-chrom was a rude combination of a lever for the removal of

rocks, a spade to cut the earth, and a foot-plough to turn it.

We annex an illustration of this curious and now obsolete

instrument. It weighed about eighteen pounds. In working

it, the upper part of the handle, to which the left-hand was

applied, reached the workman's shoulder, and being slightly

elevated, the point, shod with iron, was pushed into the ground

horizontally; the soil being turned over by inclining the handle to

the furrow side, at the same time making the heel act as a fulcrum

to raise the point of the instrument. In turning up unbroken

ground, it was first employed with the heel uppermost, with pushing

strokes to cut the breadth of the sward to be turned over, after

which, it was used horizontally as above described. We are

indebted to a Parliamentary Blue Book for the above representation

of this interesting relic of ancient agriculture. It is given

in the appendix to the 'Ninth Report of the Commissioners for

Highland Roads and Bridges,' ordered by the House of Commons to be

printed, 19th April, 1821. |

|

p.237 |

Anderson's 'Guide to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland,' 3rd ed.

p.48. |

|

p.238-1 |

He was

accompanied on this tour by Colonel Dirom, with whom he returned to

his house at Mount Annan, in Dumfries. Telford says of him:

"The Colonel seems to have roused the county of Dumfries from the

lethargy in which it has slumbered for centuries. The map of

the county, the mineralogical survey, the new roads, the opening of

lime works, the competition of ploughing, the improving harbours,

the building of bridges, are works which bespeak the exertions of no

common man."—Letter to Mr. Andrew Little, dated Shrewsbury, 30th

November, 1801. |

|

p.238-2 |

Ordered

to be printed 5th of April, 1803. |

|

p.240-1 |

'Memorials of his Time,' by Henry Cockburn, pp. 341-3. |

|

p.240-2 |

'Memoirs

of the Life and Writings of Sir John Sinclair, Bart.,' vol. i.,

p.339. |

|

p.241 |

Extract

of a letter from a gentleman residing in Sunderland, quoted in 'Life

of Telford,' p.465. |

|

p.242 |

Letter

to Mr. Andrew Little, Langholm, dated Salop, 18th February, 1803. |

|

p.247 |

The

names of Celtic places are highly descriptive. Thus

Craig-Ellachie literally means, the rock of separation;

Badenoch, bushy or woody; Cairngorm, the blue cairn;

Lochinet, the lake of nests; Balknockan, the town of

knolls; Dalnasealg, the hunting dale ; All'n dater,

the burn of the horn-blower; and so on. |

|

p.249-1 |

Sir

Thomas Dick Lauder has vividly described the destructive character

of the Spey-side inundations in his capital book on the 'Morayshire

Floods.' |

|

p.249-2 |

Ed.—Craigellachie

Bridge was cast in sections at the Plas Kynaston iron foundry at

Cefn Mawr, near Ruabon, North Wales and transported by canal and sea

to the harbour of Speymouth from where it was conveyed to site in

horse-drawn wagons. In 2007, the Institution of Civil

Engineers and American Society of Civil Engineers unveiled a plaque

on the bridge to acknowledge its international importance. |

|

p.250-1 |

'Report

of the Commissioners on Highland Roads and Bridges.' Appendix

to 'Life of Telford,' p.400. |

|

p.250-2 |

Ed.—Telford's

bridge at Bonar was swept away by a flood on 29 January 1892, a

winter of many great floods in the North of Scotland. |

|

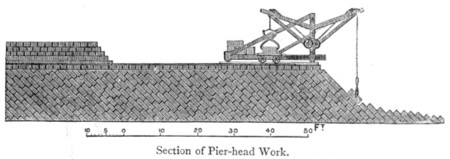

p.258 |

Hugh

Miller, in his 'Cruise of the Betsy,'

attributes the invention of columnar pier-work to Mr. Bremner, whom

he terms "the Brindley of Scotland." He has acquired great

fame for his skill in raising sunken ships, having been employed to

warp the S.S. Great Britain from Dundrum Bay. But we believe

Mr. Telford had adopted the practice of columnar pier-work before

Mr. Bremner, in forming the little harbour of Folkestone in 1808,

where the work is still to be seen quite perfect. The most

solid mode of laying stone on land is in flat courses; but in open

pier-work the reverse process is adopted. The blocks are laid

on end in columns, like upright beams jammed together. Thus

laid, the wave which dashes against them is broken, and spends

itself on the interstices; whereas, if it struck the broad solid

blocks, the tendency would be to lift them from their beds and set

the work afloat; and in a furious storm such blocks would be driven

about almost like pebbles. The rebound from flat surfaces is

also very heavy, and produces violent commotion; whereas these

broken, upright, columnar-looking piers seem to absorb the fury of

the sea, and render its wildest waves comparatively innocuous. |

|

p.265 |

'Memorials from Peterhead and Banff, concerning Damage occasioned by

a Storm.' Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed, 5th July,

1820. [242.] |

|

p.271 |

'A

Description of Bothe Touns of Aberdeene.' By James Gordon,

Parson of Rothiemay. Reprinted in Gavin Turreffs 'Antiquarian

Gleanings from Aberdeenshire Records' Aberdeen, 1859. |

|

p.272-1 |

Robertson's 'Book of Bon-Accord.' |

|

p.272-2 |

Ibid.,

quoted in Turreff's 'Antiquarian Gleanings,' p.222. |

|

p.272-3 |

One of

them, however, did return—Peter Williamson, a native of the town,

sold for a slave in Pennsylvania, "a rough, ragged, humle-headed,

long, stowie, clever boy," who, reaching York, published an account

of the infamous traffic, in a pamphlet which excited extraordinary

interest at the time, and met with a rapid and extensive

circulation. But his exposure of kidnapping gave very great

offence to the magistrates, who dragged him before their tribunal as

having "published a scurrilous and infamous libel on the

corporation," and he was sentenced to be imprisoned until he should

sign a denial of the truth of his statements. He brought an

action against the corporation for their proceedings, and obtained a

verdict and damages; and he further proceeded against Baillie

Fordyce (one of his kidnappers), and others, from whom he obtained

£200 damages, with costs. The system was thus effectually put

a stop to. |

|

p.273 |

'A

Description of Bothe Touns of Aberdeene.' By James Gordon,

Parson of Rothiemay. Quoted by Turreff, p.109. |

|

p.274 |

Communication with London was as yet by no means frequent, and far

from expeditious, as the following advertisement of 1778 will

show:—"For London: To sail positively on Saturday next, the 7th

November, wind and weather permitting, the Aberdeen smack.

Will lie a short time at London, and, if no convoy is appointed,

will sail under care of a fleet of colliers—the best convoy of any.

For particulars apply," &c., &c. |

|

p.279 |

"The bottom under the foundations," says Mr. Gibb, in

his description of the work, "is nothing better than loose sand and

gravel, constantly thrown up by the sea on that stormy coast, so

that it was necessary to consolidate the work under low water by

dropping large stones from lighters, and filling the interstices

with smaller ones, until it was brought within about a foot of the

level of low water, when the ashlar work was commenced; but in place

of laying the stones horizontally in their beds, each course was

laid at an angle of 45 degrees, to within about 18 inches of the

top, when a level coping was added. This mode of building

enabled the work to be carried on expeditiously, and rendered it

while in progress less liable to temporary damage, likewise

affording three points of bearing; for while the ashlar walling was

carrying up on both sides, the middle or body of the pier was

carried up at the same time by a careful backing throughout of large

rubble-stone, to within 18 inches of the top, when the whole was

covered with granite coping and paving 18 inches deep, with a cut

granite parapet wall on the north side of the whole length of the

pier, thus protected for the convenience of those who might have

occasion to frequent it."—Mr. Gibb's 'Narrative of Aberdeen Harbour

Works,' |

[Footnotes (con't)]

|