|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER X.

MONEY—ITS USE AND ABUSE.

|

"Not for to hide it in a

hedge,

Nor for a train attendant,

But for the glorious privilege

Of being independent.—Burns. |

|

"Neither a borrower nor a

lender be:

For loan oft loses both itself and friend;

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry."—Shakespeare. |

Never treat money affairs with levity—Money is

character.—Sir E. L. Bulwer Lytton. |

HOW a man uses

money—makes it, saves it, and spends it—is perhaps one of the best

tests of practical wisdom. Although money ought by no means to

be regarded as a chief end of man's life, neither is it a trifling

matter, to be held in philosophic contempt, representing as it does

to so large an extent, the means of physical comfort and social

well-being. Indeed, some of the finest qualities of human

nature are intimately related to the right use of money; such as

generosity, honesty, justice, and self-sacrifice; as well as the

practical virtues of economy and providence. On the other

hand, there are their counterparts of avarice, fraud, injustice, and

selfishness, as displayed by the inordinate lovers of gain; and the

vices of thriftlessness, extravagance, and improvidence, on the part

of those who misuse and abuse the means entrusted to them. "So

that," as is wisely observed by Henry Taylor in his thoughtful

'Notes from Life,' "a right measure and manner in getting, saving,

spending, giving, taking, lending, borrowing, and bequeathing, would

almost argue a perfect man."

Comfort in worldly circumstances is a condition which every

man is justified in striving to attain by all worthy means. It

secures that physical satisfaction, which is necessary for the

culture of the better part of his nature; and enables him to provide

for those of his own household, without which, says the Apostle, a

man is "worse than an infidel." Nor ought the duty to be any

the less indifferent to us, that the respect which our fellow-men

entertain for as in no slight degree depends upon the manner in

which we exercise the opportunities which present themselves for our

honourable advancement in life. The very effort required to be

made to succeed in life with this object, is of itself an education;

stimulating a man's sense of self-respect, bringing out his

practical qualities, and disciplining him in the exercise of

patience, perseverance, and such like virtues. The provident

and careful man must necessarily be a thoughtful man, for he lives

not merely for the present, but with provident forecast makes

arrangements for the future. He must also be a temperate man,

and exercise the virtue of self-denial, than which nothing is so

much calculated to give strength to the character. John

Sterling says truly, that "the worst education which teaches

self-denial, is better than the best which teaches everything else,

and not that." The Romans rightly employed the same word (virtus)

to designate courage, which is in a physical sense what the other is

in a moral; the highest virtue of all being victory over ourselves.

Hence the lesson of self-denial—the sacrificing of a present

gratification for a future good—is one of the last that is learnt.

Those classes which work the hardest might naturally be expected to

value the most the money which they earn. Yet the readiness

with which so many are accustomed to eat up and drink up their

earnings as they go, renders them to a great extent helpless and

dependent upon the frugal. There are large numbers of persons

among us who, though enjoying sufficient means of comfort and

independence, are often found to be barely a day's march ahead of

actual want when a time of pressure occurs; and hence a great cause

of social helplessness and suffering. On one occasion a

deputation waited on Lord John Russell, respecting the taxation

levied on the working classes of the country, when the noble lord

took the opportunity of remarking, "You may rely upon it that the

Government of this country durst not tax the working classes to

anything like the extent to which they tax themselves in their

expenditure upon intoxicating drinks alone!" Of all great

public questions, there is perhaps none more important than this,—no

great work of reform calling more loudly for labourers. But it

must be admitted that "self-denial and self-help" would make a poor

rallying cry for the hustings; and it is to be feared that the

patriotism of this day has but little regard for such common things

as individual economy and providence, although it is by the practice

of such virtues that the genuine independence of the industrial

classes is to be secured. "Prudence, frugality, and good

management," said Samuel Drew, the philosophical shoemaker, "are

excellent artists for mending bad times: they occupy but little room

in any dwelling, but would furnish a more effectual remedy for the

evils of life than any Reform Bill that ever passed the Houses of

Parliament." Socrates said, "Let him that would move the world

move first himself." Or as the old rhyme runs

|

"If every one would see

To his own reformation,

How very easily

You might reform a nation." |

It is, however, generally felt to be a far easier thing to reform

the Church and the State than to reform the least of our own bad

habits; and in such matters it is usually found more agreeable to

our tastes, as it certainly is the common practice, to begin with

our neighbours rather than with ourselves.

Any class of men that lives from hand to mouth will ever be

an inferior class. They will necessarily remain impotent and

helpless, hanging on to the skirts of society, the sport of times

and seasons. Having no respect for themselves, they will fail

in securing the respect of others. In commercial crises, such

men must inevitably go to the wall. Wanting that husbanded

power which a store of savings, no matter how small, invariably

gives them, they will be at every man's mercy, and, if possessed of

right feelings, they cannot but regard with fear and trembling the

future possible fate of their wives and children. "The world,"

once said Mr. Cobden to the working men of Huddersfield, "has always

been divided into two classes,—those who have saved, and those who

have spent—the thrifty and the extravagant. The building of

all the houses, the mills, the bridges, and the ships, and the

accomplishment of all other great works which have rendered man

civilized and happy, has been done by the savers, the thrifty; and

those who have wasted their resources have always been their slaves.

It has been the law of nature and of Providence that this should be

so; and I were an impostor if I promised any class that they would

advance themselves if they were improvident, thoughtless, and idle."

Equally sound was the advice given by Mr. Bright to an

assembly of working men at Rochdale, in 1847, when, after expressing

his belief that, "so far as honesty was concerned, it was to be

found in pretty equal amount among all classes," he used the

following words:—"There is only one way that is safe for any man, or

any number of men, by which they can maintain their present position

if it be a good one, or raise themselves above it if it be a bad

one,—that is, by the practice of the virtues of industry, frugality,

temperance, and honesty. There is no royal road by which men

can raise themselves from a position which they feel to be

uncomfortable and unsatisfactory, as regards their mental or

physical condition, except by the practice of those virtues by which

they find numbers amongst them are continually advancing and

bettering themselves."

There is no reason why the condition of the average workman

should not be a useful, honourable, respectable, and happy one.

The whole body of the working classes might, (with few exceptions)

be as frugal, virtuous, well-informed, and well-conditioned as many

individuals of the same class have already made themselves.

What some men are, all without difficulty might be. Employ the

same means, and the same results will follow. That there

should be a class of men who live by their daily labour in every

state is the ordinance of God, and doubtless is a wise and righteous

one; but that this class should be otherwise than frugal, contented,

intelligent, and happy, is not the design of Providence, but springs

solely from the weakness, self-indulgence, and perverseness of man

himself. The healthy spirit of self-help created amongst

working people would more than any other measure serve to raise them

as a class, and this, not by pulling down others, but by levelling

them up to a higher and still advancing standard of religion,

intelligence, and virtue. "All moral philosophy," says

Montaigne, "is as applicable to a common and private life as to the

most splendid. Every man carries the entire form of the human

condition within him."

When a man casts his glance forward, he will find that the

three chief temporal contingencies for which he has to provide are

want of employment, sickness, and death. The two first he may

escape, but the last is inevitable. It is, however, the duty

of the prudent man so to live, and so to arrange, that the pressure

of suffering, in event of either contingency occurring, shall be

mitigated to as great an extent as possible, not only to himself,

but also to those who are dependent upon him for their comfort and

subsistence. Viewed in this light the honest earning and the

frugal use of money are of the greatest importance. Rightly

earned, it is the representative of patient industry and untiring

effort, of temptation resisted, and hope rewarded; and rightly used,

it affords indications of prudence, fore-thought and self-denial—the

true basis of manly character. Though money represents a crowd

of objects without any real worth or utility, it also represents

many things of great value; not only food, clothing, and household

satisfaction, but personal self-respect and independence. Thus

a store of savings is to the working man as a barricade against

want; it secures him a footing, and enables him to wait, it may be

in cheerfulness and hope, until better days come round. The

very endeavour to gain a firmer position in the world has a certain

dignity in it, and tends to make a man stronger and better. At

all events it gives him greater freedom of action, and enables him

to husband his strength for future effort.

But the man who is always hovering on the verge of want is in

a state not far removed from that of slavery. He is in no

sense his own master, but is in constant peril of falling under the

bondage of others, and accepting the terms which they dictate to

him. He cannot help being in a measure, servile, for he dares

not look the world boldly in the face and in adverse times he must

look either to alms or the poor's rates. If work fails him

altogether, he has not the means of moving to another field of

employment; he is fixed to his parish like a limpet to its rock, and

can neither migrate nor emigrate.

To secure independence, the practice of simple economy is all

that is necessary. Economy requires neither superior courage

nor eminent virtue; it is satisfied with ordinary energy, and the

capacity of average minds. Economy, at bottom, is but the

spirit of order applied in the administration of domestic affairs:

it means management, regularity, prudence, and the avoidance of

waste. The spirit of economy was expressed by our Divine

Master in the words 'Gather up the fragments that remain, so that

nothing may be lost.' His omnipotence did not disdain the

small things of life; and even while revealing His infinite power to

the multitude, he taught the pregnant lesson of carefulness of which

all stand so much in need.

Economy also means the power of resisting present

gratification for the purpose of securing a future good, and in this

light it represents the ascendancy of reason over the animal

instincts. It is altogether different from penuriousness: for

it is economy that can always best afford to be generous. It

does not make money an idol but regards it as a useful agent.

As Dean Swift observes, "we must carry money in the head, not in the

heart." Economy may be styled the daughter of Prudence, the sister

of Temperance, and the mother of Liberty. It is evidently

conservative—conservative of character, of domestic happiness, and

social wellbeing. It is, in short, the exhibition of self-help

in one of its best forms.

Francis Homer's father gave him this advice on entering

life:—"Whilst I wish you to be comfortable in every respect, I

cannot too strongly inculcate economy. It is a necessary

virtue to all; and however the shallow part of mankind may despise

it, it certainly leads to independence, which is a grand object to

every man of a high spirit." Burns' lines, quoted at the head

of this chapter, contain the right idea; but unhappily his strain of

song was higher than his practice; his ideal better than his habit.

When laid on his death-bed he wrote to a friend, "Alas! Clarke, I

begin to feel the worst. Burns' poor widow, and half a dozen

of his dear little ones helpless orphans;—there I am weak as a

woman's tear. Enough of this;—'tis half my disease."

Every man ought so to contrive as to live within his means.

This practice is of the very essence of honesty. For if a man

do not manage honestly to live within his own means, he must

necessarily be living dishonestly upon the means of somebody else.

Those who are careless about personal expenditure, and consider

merely their own gratification, without regard for the comfort of

others, generally find out the real uses of money when it is too

late. Though by nature generous, these thriftless persons are

often driven in the end to do very shabby things. They waste

their money as they do their time; draw bills upon the future;

anticipate their earnings; and are thus under the necessity of

dragging after them a load of debts and obligations which seriously

affect their action as free and independent men.

It was a maxim of Lord Bacon, that when it was necessary to

economize, it was better to look after petty savings than to descend

to petty gettings. The loose cash which many persons throw

away uselessly, and worse, would often form a basis of fortune and

independence for life. These wasters are their own worst

enemies, though generally found amongst the ranks of those who rail

at the injustice of "the world." But if a man will not be his

own friend, how can he expect that others will? Orderly men of

moderate means have always something left in their pockets to help

others whereas your prodigal and careless fellows who spend all

never find an opportunity for helping anybody. It is poor

economy, however, to be a scrub. Narrow-mindedness in living

and in dealing is generally short-sighted, and leads to failure.

The penny soul, it is said, never came to twopence. Generosity

and liberality, like honesty, prove the best policy after all.

Though Jenkinson, in the 'Vicar of Wakefield,' cheated his

kind-hearted neighbour Flamborough in one way or another every year,

"Flamborough," said he, "has been regularly growing in riches, while

I have come to poverty and a gaol." And practical life abounds

in cases of brilliant results from a course of generous and honest

policy.

The proverb says that "an empty bag cannot stand upright;"

neither can a man who is in debt. It is also difficult for a

man who is in debt to be truthful; hence it is said that lying rides

on debt's back. The debtor has to frame excuses to his

creditor for postponing payment of the money he owes him; and

probably also to contrive falsehoods. It is easy enough for a

man who will exercise a healthy resolution, to avoid incurring the

first obligation; but the facility with which that has been incurred

often becomes a temptation to a second; and very soon the

unfortunate borrower becomes so entangled that no late exertion of

industry can set him free. The first step in debt is like the

first step in falsehood; almost involving the necessity of

proceeding in the same course, debt following debt, as lie follows

lie. Haydon, the painter, dated his decline from the day on

which he first borrowed money. He realized the truth of the

proverb, "Who goes a-borrowing, goes a-sorrowing." The

significant entry in his diary is: "Here began debt and obligation,

out of which I have never been and never shall be extricated as long

as I live." His Autobiography shows but too painfully how

embarrassment in money matters produces poignant distress of mind,

utter incapacity for work, and constantly recurring humiliations.

The written advice which he gave to a youth when entering the navy

was as follows: "Never purchase any enjoyment if it cannot be

procured without borrowing of others. Never borrow money: it

is degrading. I do not say never lend, but never lend if by

lending you render yourself unable to pay what you owe; but under

any circumstances never borrow." Fichte, the poor student,

refused to accept even presents from his still poorer parents.

Dr. Johnson held that early debt is ruin. His words on

the subject are weighty, and worthy of being held in remembrance.

"Do not," said he, "accustom yourself to consider debt only as an

inconvenience; you will find it a calamity. Poverty takes away

so many means of doing good, and produces so much inability to

resist evil, both natural and moral, that it is by all virtuous

means to be avoided. . . . Let it be your first care, then, not to

be in any man's debt. Resolve not to be poor; whatever you

have spend less. Poverty is a great enemy to human happiness;

it certainly destroys liberty, and it makes some virtues

impracticable and others extremely difficult. Frugality is not

only the basis of quiet, but of beneficence. No man can help

others that wants help himself; we must have enough before we have

to spare."

It is the bounden duty of every man to look his affairs in

the face, and to keep an account of his incomings and outgoings in

money matters. The exercise of a little simple arithmetic in

this way will be found of great value. Prudence requires that

we shall pitch our scale of living a degree below our means, rather

than up to them; but this can only be done by carrying out

faithfully a plan of living by which both ends may be made to meet.

John Locke strongly advised this course: "Nothing," said he "is

likelier to keep a man within compass than having constantly before

his eyes the state of his affairs in a regular course of account."

The Duke of Wellington kept an accurate detailed account of all the

monies received and expended by him. "I make a point," said he

to Mr. Gleig, "of paying my own bills, and I advise every one to do

the same; formerly I used to trust a confidential servant to pay

them, but I was cured of that folly by receiving one morning, to my

great surprise, duns of a year or two's standing. The fellow

had speculated with my money, and left my bills unpaid."

Talking of debt his remark was, "It makes a slave of a man. I

have often known what it was to be in want of money, but I never got

into debt." Washington was as particular as Wellington was, in

matters of business detail; and it is a remarkable fact, that he did

not disdain to scrutinize the smallest outgoings of his

household—determined as he was to live honestly within his

means—even while holding the high office of President of the

American Union.

Admiral Jervis, Earl St. Vincent, has told the story of his

early struggles, and, amongst other things, of his determination to

keep out of debt. "My father had a very large family," said

he, "with limited means. He gave me twenty pounds at starting,

and that was all he ever gave me. After I had been a

considerable time at the station [at sea], I drew for twenty more,

but the bill came back protested. I was mortified at this

rebuke, and made a promise, which I have ever kept, that I would

never draw another bill without a certainty of its being paid.

I immediately changed my mode of living, quitted my mess, lived

alone, and took up the ship's allowance, which I found quite

sufficient; washed and mended my own clothes; made a pair of

trousers out of the ticking of my bed; and having by these means

saved as much money as would redeem my honour, I took up my bill,

and from that time to this I have taken care to keep within my

means." Jervis for six years endured pinching privation, but

preserved his integrity, studied his profession with success, and

gradually and steadily rose by merit and bravery to the highest

rank.

Mr. Hume hit the mark when he once stated in the House of

Commons—though his words were followed by "laughter"—that the tone

of living in England is altogether too high. Middle-class

people are too apt to live up to their incomes, if not beyond them:

affecting a degree of "style" which is most unhealthy in its effects

upon society at large. There is an ambition to bring up boys

as gentlemen, or rather "genteel" men; though the result frequently

is, only to make them gents. They acquire a taste for dress,

style, luxuries, and amusements, which can never form any solid

foundation for manly or gentlemanly character; and the result is,

that we have a vast number of gingerbread young gentry thrown upon

the world, who remind one of the abandoned hulls sometimes picked up

at sea, with only a monkey on board.

There is a dreadful ambition abroad for being "genteel."

We keep up appearances, too often at the expense of honesty; and,

though we may not be rich, yet we must seem to be so. We must

be "respectable," though only in the meanest sense—in mere vulgar

outward show. We have not the courage to go patiently onward

in the condition of life in which it has pleased God to call us; but

must needs live in some fashionable state to which we ridiculously

please to call ourselves, and all to gratify the vanity of that

unsubstantial genteel world of which we form a part. There is

a constant struggle and pressure for front seats in the social

amphitheatre in the midst of which all noble self-denying resolve is

trodden down, and many fine natures are inevitably crushed to death.

What waste, what misery, what bankruptcy, come from all this

ambition to dazzle others with the glare of apparent worldly

success, we need not describe. The mischievous results show

themselves in a thousand ways—in the rank frauds committed by men

who dare to be dishonest, but do not dare to seem poor; and in the

desperate dashes at fortune, in which the pity is not so much for

those who fail, as for the hundreds of innocent families who are so

often involved in their ruin.

|

|

|

SIR

CHARLES JAMES

NAPIER

GCB (1782-1853)

British general and C-in-C in India.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

The late Sir Charles Napier, in taking leave of his command in

India, did a bold and honest thing in publishing his strong protest,

embodied in his List General Order to the officers of the Indian

army, against the "fast" life led by so many young officers in that

service, involving them in ignominious obligations. Sir

Charles strongly urged in that famous document—what had almost been

lost sight of—that "honesty is inseparable from the character of a

thorough-bred gentleman;" and that "to drink unpaid-for champagne

and unpaid-for beer, and to ride unpaid-for horses, is to be a

cheat, and not a gentleman." Men who lived beyond their means

and were summoned, often by their own servants, before Courts of

Requests for debts contracted in extravagant living, might be

officers by virtue of their commissions, but they were not

gentlemen. The habit of being constantly in debt, the

Commander-in-chief held, made men grow callous to the proper

feelings of a gentleman. It was not enough that an officer

should be able to fight: that any bull-dog could do. But did

he hold his word inviolate?—did he pay his debts? These were

among the points of honour which, he insisted, illuminated the true

gentleman's and soldier's career. As Bayard was of old, so

would Sir Charles Napier have all British officers to be. He

knew them to be "without fear," but he would also have them "without

reproach." There are, however, many gallant young fellows,

both in India and at home, capable of mounting a breach on an

emergency amidst belching fire, and of performing the most desperate

deeds of valour, who nevertheless cannot or will not exercise the

moral courage necessary to enable them to resist a petty temptation

presented to their senses. They cannot utter their valiant

"No," or "I can't afford it," to the invitations of pleasure and

self-enjoyment; and they are found ready to brave death rather than

the ridicule of their companions.

The young man, as he passes through life, advances through a

long line of tempters ranged on either side of him, and the

inevitable effect of yielding, is degradation in a greater or a less

degree. Contact with them tends insensibly to draw away from

him some portion of the divine electric element with which his

nature is charged; and his only mode of resisting them is to utter

and to act out his "no" manfully and resolutely. He must decide at

once, not waiting to deliberate and balance reasons; for the youth,

like "the woman who deliberates, is lost." Many deliberate, without

deciding; but "not to resolve, is to resolve." A perfect

knowledge of man is in the prayer, "Lead us not into temptation."

But temptation will come to try the young man's strength; and once

yielded to, the power to resist grows weaker and weaker. Yield

once, and a portion of virtue has gone. Resist manfully, and

the first decision will give strength for life; repeated, it will

become a habit. It is in the outworks of the habits formed in

early life that the real strength of the defence must lie; for it

has been wisely ordained, that the machinery of moral existence

should be carried on principally through the medium of the habits,

so as to save the wear and tear of the great principles within.

It is good habits, which insinuate themselves into the thousand

inconsiderable acts of life, that really constitute by far the

greater part of man's moral conduct.

Hugh Miller has told how, by an act of youthful decision, he

saved himself from one of the strong temptations so peculiar to a

life of toil. When employed as a mason, it was usual for his

fellow-workmen to have an occasional treat of drink, and one day two

glasses of whisky fell to his share, which he swallowed. When

he reached home, he found, on opening his favourite book—'Bacon's

Essays'—that the letters danced before his eyes, and that he could

no longer master the sense. "The condition," he says, "into

which I had brought myself was, I felt, one of degradation. I

had sunk, by my own act, for the time, to a lower level of

intelligence than that on which it was my privilege to be placed;

and though the state could have been no very favourable one for

forming a resolution, I in that hour determined that I should never

again sacrifice my capacity of intellectual enjoyment to a drinking

usage; and, with God's help, I was enabled to hold by the

determination." It is such decisions as this that often form

the turning-points in a man's life, and furnish the foundation of

his future character. And this rock, on which Hugh Miller

might have been wrecked, if he had not at the right moment put forth

his moral strength to strike away from it, is one that youth and

manhood alike need to be constantly on their guard against. It

is about one of the worst and most deadly, as well as extravagant,

temptations which lie in the way of youth. Sir Walter Scott

used to say that "of all vices drinking is the most incompatible

with greatness." Not only so, but it is incompatible with

economy, decency, health, and honest living. When a youth

cannot restrain, he must abstain. Dr. Johnson's case is the

case of many. He said, referring to his own habits, "Sir, I

can abstain; but I can't be moderate."

But to wrestle vigorously and successfully with any vicious

habit, we must not merely be satisfied with contending on the low

ground of worldly prudence, though that is of use, but take stand

upon a higher moral elevation. Mechanical aids, such as

pledges, may be of service to some, but the great thing is to set up

a high standard of thinking and acting, and endeavour to strengthen

and purify the principles as well as to reform the habits. For

this purpose a youth must study himself, watch his steps, and

compare his thoughts and acts with his rule. The more

knowledge of himself he gains, the more humble will he be, and

perhaps the less confident in his own strength. But the

discipline will be always found most valuable which is acquired by

resisting small present gratifications to secure a prospective

greater and higher one. It is the noblest work in

self-education,—for

|

"Real glory

Springs from the silent conquest of ourselves,

And without that the conqueror is nought

But the first slave." |

Many popular books have been written for the purpose of

communicating to the public the grand secret of making money.

But there is no secret whatever about it, as the proverbs of every

nation abundantly testify. "Take care of the pennies and the

pounds will take care of themselves." "Diligence is the mother

of good luck." "No pains no gains." "No sweat no sweet."

"Work and thou shalt have." "The world is his who has patience

and industry." "Better go to bed supperless than rise in

debt." Such are specimens of the proverbial philosophy,

embodying the hoarded experience of many generations, as to the best

means of thriving in the world. They were current in people's

mouths long before books were invented; and like other popular

proverbs they were the first codes of popular morals. Moreover

they have stood the test of time, and the experience of every day

still bears witness to their accuracy, force, and soundness.

The proverbs of Solomon are full of wisdom as to the force of

industry, and the use and abuse of money:—"He that is slothful in

work is brother to him that is a great waster." "Go to the ant

thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise." Poverty, says

the preacher, shall come upon the idler, "as one that travelleth,

and want as an armed man;" but of the industrious and upright, "the

hand of the diligent maketh rich." "The drunkard and the

glutton shall come to poverty; and drowsiness shall clothe a man

with rags." "Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he

shall stand before kings." But above all "It is better to get

wisdom than gold; for wisdom is better than rubies, and all the

things that may be desired are not to be compared to it."

Simple industry and thrift will go far towards making any

person of ordinary working faculty comparatively independent in his

means. Even a working man may be so, provided he will

carefully husband his resources, and watch the little outlets of

useless expenditure. A penny is a very small matter, yet the

comfort of thousands of families depends upon the proper spending

and saving of pennies. If a man allows the little pennies, the

results of his hard work, to slip out of his fingers—some to the

beer shop, some this way and some that—he will find that his life is

little raised above one of mere animal drudgery. On the other

hand, if he take care of the pennies—putting some weekly into a

benefit society or an insurance fund, others into a savings' bank,

and confiding the rest to his wife to be carefully laid out, with a

view to the comfortable maintenance and education of his family—he

will soon find that this attention to small matters will abundantly

repay him, in increasing means, growing comfort at home, and a mind

comparatively free from fears as to the future. And if a

working man have high ambition and possess richness in spirit,—a

kind of wealth which far transcends all mere worldly possessions—he

may not only help himself, but be a profitable helper of others in

his path through life. That this is no impossible thing even

for a common labourer in a workshop, may be illustrated by the

remarkable career of Thomas Wright of Manchester, who not only

attempted but succeeded in the reclamation of many criminals while

working for weekly wages in a foundry.

Accident first directed Thomas Wright's attention to the

difficulty encountered by liberated convicts in returning to habits

of honest industry. His mind was shortly possessed by the

subject; and to remedy the evil became the purpose of his life.

Though he worked from six in the morning till six at night, still

there were leisure minutes that he could call his own—more

especially his Sundays—and these he employed in the service of

convicted criminals; a class then far more neglected than they are

now. But a few minutes a day, well employed, can effect a

great deal; and it will scarcely be credited, that in ten years this

working man, by steadfastly holding to his purpose, succeeded in

rescuing not fewer than three hundred felons from continuance in a

life of villany! He came to be regarded as the moral physician

of the Manchester Old Bailey; and where the Chaplain and all others

failed, Thomas Wright often succeeded. Children he thus

restored reformed to their parents; sons and daughters otherwise

lost, to their homes; and many a returned convict did he contrive to

settle down to honest and industrious pursuits. The task was

by no means easy. It required money, time, energy, prudence,

and above all, character, and the confidence which character

invariably inspires. The most remarkable circumstance was that

Wright relieved many of these poor outcasts out of the comparatively

small wages earned by him at foundry work. He did all this on

an income which did not average, during his working career, £100 per

annum; and yet, while he was able to bestow substantial aid on

criminals, to whom he owed no more than the service of kindness

which every human being owes to another, he also maintained his

family in comfort, and was, by frugality and carefulness, enabled to

lay by a store of savings against his approaching old age.

Every week he apportioned his income with deliberate care; so much

for the indispensable necessaries of food and clothing, so much for

the landlord, so much for the schoolmaster, so much for the poor and

needy; and the lines of distribution were resolutely observed.

By such means did this humble workman pursue his great work, with

the results we have so briefly described. Indeed, his career

affords one of the most remarkable and striking illustrations of the

force of purpose in a man, of the might of small means carefully and

sedulously applied, and, above all, of the power which an energetic

and upright character invariably exercises upon the lives and

conduct of others.

There is no discredit, but honour, in every right walk of

industry, whether it be in tilling the ground, making tools, weaving

fabrics, or selling the products behind a counter. A youth may

handle a yard-stick, or measure a piece of ribbon; and there will be

no discredit in doing so, unless he allows his mind to have no

higher range than the stick and ribbon; to be as short as the one,

and as narrow as the other. "Let not those blush who have,"

said Fuller, "but those who have not a lawful calling." And

Bishop Hall said, "Sweet is the destiny of all trades, whether of

the brow or of the mind." Men who have raised themselves from

a humble calling, need not be ashamed, but rather ought to be proud

of the difficulties they have surmounted. An American

President, when asked what was his coat-of-arms, remembering that he

had been a hewer of wood in his youth, replied, "A pair of shirt

sleeves." A French doctor once taunted Flechier, Bishop of

Nismes, who had been a tallow-chandler in his youth, with the

meanness of his origin, to which Flechier replied, "If you had been

born in the same condition that I was, you would still have been but

a maker of candles."

Nothing is more common than energy in money-making, quite

independent of any higher object than its accumulation. A man

who devotes himself to this pursuit, body and soul, can scarcely

fail to become rich. Very little brains will do; spend less

than you earn; add guinea to guinea; scrape and save; and the pile

of gold will gradually rise. Osterwald the Parisian banker,

began life a poor man. He was accustomed every evening to

drink a pint of beer for supper at a tavern which he visited, during

which he collected and pocketed all the corks that he could lay his

hands on. In eight years he had collected as many corks as

sold for eight Louis d'ors. With that sum he laid the

foundations of his fortune—gained mostly by stock-jobbing; leaving

at his death some three millions of francs. John Foster has

cited a striking illustration of what this kind of determination

will do in money-making. A young man who ran through his

patrimony, spending it in profligacy, was at length reduced to utter

want and despair. He rushed out of his house intending to put

an end to his life, and stopped on arriving at an eminence

overlooking what were once his estates. He sat down, ruminated

for a time, and rose with the determination that he would recover

them. He returned to the streets, saw a load of coals which

had been shot out of a cart on to the pavement before a house,

offered to carry them in, and was employed. He thus earned a

few pence, requested some meat and drink as a gratuity, which was

given him, and the pennies were laid by. Pursuing this menial

labour, he earned and saved more pennies; accumulated sufficient to

enable him to purchase some cattle, the value of which he

understood, and these he sold to advantage. He proceeded by

degrees to undertake larger transactions, until at length he became

rich. The result was, that he more than recovered his

possessions, and died an inveterate miser. When he was buried,

mere earth went to earth. With a nobler spirit, the same

determination might have enabled such a man to be a benefactor to

others as well as to himself. But the life and its end in this

case were alike sordid.

To provide for others and for our own comfort and

independence in old age, is honourable, and greatly to be commended;

but to hoard for mere wealth's sake is the characteristic of the

narrow-souled and the miserly. It is against the growth of

this habit of inordinate saving that the wise man needs most

carefully to guard himself: else, what in youth was simple economy,

may in old age grow into avarice, and what was a duty in the one

case, may become a vice in the other. It is the love of

money—not money itself—which is "the root of evil,"—a love which

narrows and contracts the soul, and closes it against generous life

and action. Hence, Sir Walter Scott makes one of his

characters declare that "the penny siller slew more souls than the

naked sword slew bodies." It is one of the defects of business

too exclusively followed, that it insensibly tends to a mechanism of

character. The business man gets into a rut, and often does

not look beyond it. If he lives for himself only, he becomes

apt to regard other human beings only in so far as they minister to,

his ends. Take a leaf from such men's ledger and you have

their life.

Worldly success, measured by the accumulation of money, is no

doubt a very dazzling thing; and all men are naturally more or less

the admirers of worldly success. But though men of

persevering, sharp, dexterous, and unscrupulous habits, ever on the

watch to push opportunities, may and do "get on" in the world, yet

it is quite possible that they may not possess the slightest

elevation of character, nor a particle of real goodness. He

who recognizes no higher logic than that of the shilling, may become

a very rich man, and yet remain all the while an exceedingly poor

creature. For riches are no proof whatever of moral worth; and

their glitter often serves only to draw attention to the

worthlessness of their possessor, as the light of the glow-worm

reveals the grub.

The manner in which many allow themselves to be sacrificed to

their love of wealth reminds one of the cupidity of the monkey—that

caricature of our species. In Algiers, the Kabyle peasant

attaches a gourd, well fixed, to a tree, and places within it some

rice. The gourd has an opening merely sufficient to admit the

monkey's paw. The creature comes to the tree by night, inserts

his paw, and grasps his booty. He tries to draw it back, but

it is clenched, and he has not the wisdom to unclench it. So

there he stands till morning, when he is caught, looking as foolish

as may be, though with the prize in his grasp. The moral of

this little story is capable of a very extensive application in

life.

The power of money is on the whole over-estimated. The

greatest things which have been done for the world have not been

accomplished by rich men, nor by subscription lists, but by men

generally of small pecuniary means. Christianity was

propagated over half the world by men of the poorest class; and the

greatest thinkers, discoverers, inventors, and artists, have been

men of moderate wealth, many of them little raised above the

condition of manual labourers in point of worldly circumstances.

And it will always be so. Riches are oftener an impediment

than a stimulus to action; and in many cases they are quite as much

a misfortune as a blessing. The youth who inherits wealth is

apt to have life made too easy for him, and he soon grows sated with

it, because he has nothing left to desire. Having no special

object to struggle for he finds time hang heavy on his hands; he

remains morally and spiritually asleep; and his position in society

is often no higher than that of a polypus over which the tide

floats.

|

"His only labour is to kill the time,

And labour dire it is, and weary woe." |

Yet the rich man, inspired by a right spirit, will spurn

idleness as unmanly; and if he bethink himself of the

responsibilities which attach to the possession of wealth and

property he will feel even a higher call to work than men of humbler

lot. This, however, must be admitted to be by no means the

practice of life. The golden mean of Agur's perfect prayer is,

perhaps, the best lot of all, did we but know it: "Give me neither

poverty nor riches; feed me with food convenient for me." The

late Joseph Brotherton, M.P., left a fine motto to be recorded upon

his monument in the Peel Park at Manchester,—the declaration in his

case being strictly true: "My richness consisted not in the

greatness of my possessions, but in the smallness of my wants."

He rose from the humblest station, that of a factory boy, to an

eminent position of usefulness, by the simple exercise of homely

honesty, industry, punctuality, and self-denial. Down to the

close of his life, when not attending Parliament, he did duty as

minister in a small chapel in Manchester to which he was attached;

and in all things he made it appear, to those who knew him in

private life, that the glory he sought was not "to be seen of men,"

or to excite their praise, but to earn the consciousness of

discharging the every-day duties of life, down to the smallest and

humblest of them, in an honest, upright, truthful, and loving

spirit.

"Respectability," in its best sense, is good. The

respectable man is one worthy of regard, literally worth turning to

look at. But the respectability that consists in merely

keeping up appearances is not worth looking at in any sense.

Far better and more respectable is the good poor man than the bad

rich one—better the humble silent man than the agreeable

well-appointed rogue who keeps his gig. A well balanced and

well-stored mind, a life full of useful purpose, whatever the

position occupied in it may be, is of far greater importance than

average worldly respectability. The highest object of life we

take to be, to form a manly character, and to work out the best

development possible, of body and spirit—of mind, conscience, heart,

and soul. This is the end: all else ought to be regarded but

as the means. Accordingly, that is not the most successful

life in which a man gets the most pleasure, the most money, the most

power or place, honour or fame; but that in which a man gets the

most manhood, and performs the greatest amount of useful work and of

human duty. Money is power after its sort, it is true; but

intelligence, public spirit, and moral virtue, are powers too, and

far nobler ones. "Let others plead for pensions," wrote Lord

Collingwood to a friend; "I can be rich without money, by

endeavouring to be superior to everything poor. I would have

my services to my country unstained by any interested motive; and

old Scott [p.313] and I can go

on in our cabbage-garden without much greater expense than

formerly." On another occasion he said, "I have motives for my

conduct which I would not give in exchange for a hundred pensions."

The making of a fortune may no doubt enable some people to

"enter society," as it is called; but to be esteemed there, they

must possess qualities of mind, manners, or heart, else they are

merely rich people, nothing more. There are men "in society"

now, as rich as Crœsus, who have no consideration extended towards

them, and elicit no respect. For why? They are but as

money-bags: their only power is in their till. The men of mark

in society—the guides and rulers of opinion—the really successful

and useful men—are not necessarily rich men; but men of sterling

character, of disciplined experience, and of moral excellence.

Even the poor man, like Thomas Wright, though he possess but little

of this world's goods, may, in the enjoyment of a cultivated nature,

of opportunities used and not abused, of a life spent to the best of

his means and ability, look down, without the slightest feeling of

envy, upon the person of mere worldly success, the man of money-bags

and acres.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XI.

SELF-CULTURE — FACILITIES AND DIFFICULTIES.

"Every person has two educations,

one which be receives from others, and one, more important, which he

gives to himself."—Gibbon.

"Is there one whom difficulties dishearten—who bends to the

storm? He will do little. Is there one who will conquer?

That kind of man never fails."—John Hunter.

|

"The wise and active conquer

difficulties,

By daring to attempt them: sloth and folly

Shiver and shrink at sight of toil and danger,

And make the impossibility they fear."—Rowe. |

"THE best part of

every man's education," said Sir Walter Scott, "is that which he

gives to himself." The late Sir Benjamin Brodie delighted to

remember this saying, and he used to congratulate himself on the

fact that professionally he was self-taught. But this is

necessarily the case with all men who have acquired distinction in

letters, science, or art. The education received at school or

college is but a beginning, and is valuable mainly inasmuch as it

trains the mind and habituates it to continuous application and

study. That which is put into us by others is always far less

ours than that which we acquire by our own diligent and persevering

effort. Knowledge conquered by labour becomes a possession—a

property entirely our own. A greater vividness and permanency

of impression is secured; and facts thus acquired become registered

in the mind in a way that mere imparted information can never

effect. This kind of self-culture also calls forth power and

cultivates strength. The solution of one problem helps the

mastery of another; and thus knowledge is carried into faculty.

Our own active effort is the essential thing; and no facilities, no

books, no teachers, no amount of lessons learnt by rote will enable

us to dispense with it.

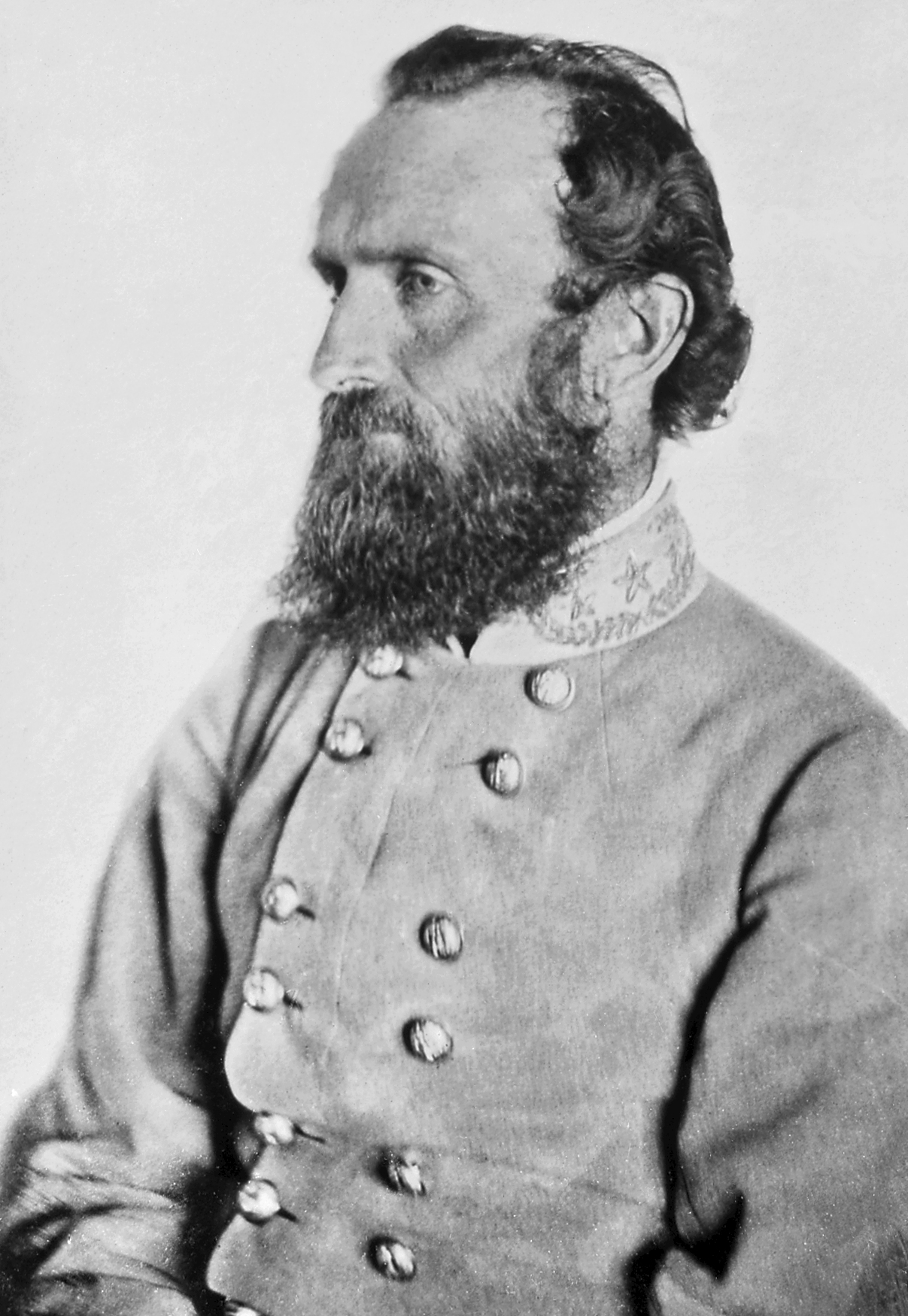

THOMAS ARNOLD

(1795-1842):

English educator and historian.

Picture: Wikipedia.

The best teachers have been the readiest to recognise the

importance of self-culture, and of stimulating the student to

acquire knowledge by the active exercise of his own faculties.

They have relied more upon training than upon telling,

and sought to make their pupils themselves active parties to the

work in which they were engaged; thus making teaching something far

higher than the mere passive reception of the scraps and details of

knowledge. This was the spirit in which the great Dr. Arnold

worked; he strove to teach his pupils to rely upon themselves, and

develop their powers by their own active efforts, himself merely

guiding, directing, stimulating, and encouraging them. "I

would far rather," he said, "send a boy to Van Diemen's Land, where

he must work for his bread, than send him to Oxford to live in

luxury, without any desire in his mind to avail himself of his

advantages." "If there be one thing on earth," he observed on

another occasion, "which is truly admirable, it is to see God's

wisdom blessing an inferiority of natural powers, when they have

been honestly, truly, and zealously cultivated." Speaking of a

pupil of this character, he said, "I would stand to that man hat in

hand." Once at Laleham, when teaching a rather dull boy,

Arnold spoke somewhat sharply to him, on which the pupil looked up

in his face and said, "Why do you speak angrily, sir? indeed,

I am doing the best I can." Years afterwards, Arnold used to

tell the story to his children, and added, "I never felt so much in

my life—that look and that speech I have never forgotten."

From the numerous instances already cited of men of humble

station who have risen to distinction in science and literature, it

will be obvious that labour is by no means incompatible with the

highest intellectual culture. Work in moderation is healthy,

as well as agreeable to the human constitution. Work educates

the body, as study educates the mind; and that is the best state of

society in which there is some work for every man's leisure, and

some leisure for every man's work. Even the leisure classes

are in a measure compelled to work, sometimes as a relief from

ennui, but in most cases to gratify an instinct which they cannot

resist. Some go foxhunting in the English counties, others

grouse-shooting on the Scotch hills, while many wander away every

summer to climb mountains in Switzerland. Hence the boating,

running, cricketing, and athletic sports of the public schools, in

which our young men at the same time so healthfully cultivate their

strength both of mind and body. It is said that the Duke of

Wellington, when once looking on at the boys engaged in their sports

in the play-ground at Eton, where he had spent many of his own

younger days, made the remark, "It was there that the battle of

Waterloo was won!"

Daniel Malthus urged his son when at college to be most

diligent in the cultivation of knowledge, but he also enjoined him

to pursue manly sports as the best means of keeping up the full

working power of his mind, as well as of enjoying the pleasures of

intellect. "Every kind of knowledge," said he, "every

acquaintance with nature and art, will amuse and strengthen your

mind, and I am perfectly pleased that cricket should do the same by

your arms and legs; I love to see you excel in exercises of the

body, and I think myself that the better half, and much the most

agreeable part, of the pleasures of the mind is best enjoyed while

one is upon one's legs." But a still more important use of

active employment is that referred to by the great divine, Jeremy

Taylor. "Avoid idleness," he says, "and fill up all the spaces

of thy time with severe and useful employment; for lust easily

creeps in at those emptinesses where the soul is unemployed and the

body is at ease; for no easy, healthful, idle person was ever chaste

if he could be tempted; but of all employments bodily labour is the

most useful, and of the greatest benefit for driving away the

devil."

Practical success in life depends more upon physical health

than is generally imagined. Hodson, of Hodson's Horse [p.317],

writing home to a friend in England, said, "I believe, if I get on

well in India, it will be owing, physically speaking, to a sound

digestion." The capacity for continuous working in any calling

must necessarily depend in a great measure upon this; and hence the

necessity for attending to health, even as a means of intellectual

labour. It is perhaps to the neglect of physical exercise that

we find amongst students so frequent a tendency towards discontent,

unhappiness, inaction, and reverie,—displaying itself in contempt

for real life and disgust at the beaten tracks of men,—a tendency

which in England has been called Byronism, and in Germany Wertherism.

Dr. Channing noted the same growth in America, which led him to make

the remark, that "too many of our young men grow up in a school of

despair." The only remedy for this green-sickness in youth is

physical exercise—action, work, and bodily occupation.

|

|

|

ELIHU

BURRITT

(1810-79);

American philanthropist and social activist.

Picture Wikipedia. |

The use of early labour in self-imposed mechanical employments may

be illustrated by the boyhood of Sir Isaac Newton. Though a

comparatively dull scholar, he was very assiduous in the use of his

saw, hammer, and hatchet "knocking and hammering in his lodging

room"—making models of windmills, carriages, and machines of all

sorts, and as he grew older, he took delight in making little tables

and cupboards for his friends. Smeaton, Watt, and Stephenson,

were equally handy with tools when mere boys; and but for such kind

of self-culture in their youth, it is doubtful whether they would

have accomplished so much in their manhood. Such was also the

early training of the great inventors and mechanics described in the

preceding pages, whose contrivance and intelligence were practically

trained by the constant use of their hands in early life. Even

where men belonging to the manual labour class have risen above it,

and become more purely intellectual labourers, they have found the

advantages of their early training in their later pursuits.

Elihu Burritt says he found hard labour necessary to enable him to

study with effect; and more than once he gave up school-teaching and

study, and, taking to his leather-apron again, went back to his

blacksmith's forge and anvil for his health of body and mind's sake.

The training of young men in the use of tools would, at the

same time that it educated them in "common things," teach them the

use of their hands and arms, familiarize them with healthy work,

exercise their faculties upon things tangible and actual, give them

some practical acquaintance with mechanics, impart to them the

ability of being useful, and implant in them the habit of

persevering physical effort. This is an advantage which the

working classes, strictly so called, certainly possess over the

leisure classes,—that they are in early life under the necessity of

applying themselves laboriously to some mechanical pursuit or

other,—thus acquiring manual dexterity and the use of their physical

powers. The chief disadvantage attached to the calling of the

laborious classes is, not that they are employed in physical work,

but that they are too exclusively so employed, often to the neglect

of their moral and intellectual faculties. While the youths of

the leisure classes, having been taught to associate labour with

servility, have shunned it, and been allowed to grow up practically

ignorant, the poorer classes, confining themselves within the circle

of their laborious callings, have been allowed to grow up in a large

proportion of cases absolutely illiterate. It seems possible,

however, to avoid both these evils by combining physical training or

physical work with intellectual culture; and there are various signs

abroad which seem to mark the gradual adoption of this healthier

system of education.

The success of even professional men depends in no slight degree on

their physical health; and a public writer has gone so far as to say

that "the greatness of our great men is quite as much a bodily

affair as a mental one." [p.319] A healthy breathing apparatus is as indispensable to the successful

lawyer or politician as a well-cultured intellect. The thorough

aeration of the blood by free exposure to a large breathing surface

in the lungs, is necessary to maintain that full vital power on

which the vigorous working of the brain in so large a measure

depends. The lawyer has to climb the heights of his profession

through close and heated courts, and the political leader has to

bear the fatigue and excitement of long and anxious debates in a

crowded House. Hence the lawyer in full practice and the

parliamentary leader in full work are called upon to display powers

of physical endurance and activity even more extraordinary than

those of the intellect,—such powers as have been exhibited in so

remarkable a degree by Brougham, Lyndhurst, and Campbell; by Peel,

Graham, and Palmerston—all full-chested men.

Though Sir Walter Scott, when at Edinburgh College, went by the name

of "The Greek Blockhead," he was, notwithstanding his lameness, a

remarkably healthy youth: he could spear a salmon with the best

fisher on the Tweed, and ride a wild horse with any hunter in

Yarrow. When devoting himself in after life to literary pursuits,

Sir Walter never lost his taste for field sports; but while writing

'Waverley' in the morning, he would in the afternoon course hares. Professor Wilson was a very athlete, as great at throwing the hammer

as in his flights of eloquence and poetry; and Burns, when a youth,

was remarkable chiefly for his leaping, putting, and wrestling. Some

of our greatest divines were distinguished in their youth for their

physical energies. Isaac Barrow, when at the Charterhouse School,

was notorious for his pugilistic encounters, in which he got many a

bloody nose; Andrew Fuller, when working as a farmer's lad at Soham,

was chiefly famous for his skill in boxing; and Adam Clarke, when a

boy, was only remarkable for the strength displayed by him in

"rolling large stones about,"—the secret, possibly, of some of the

power which he subsequently displayed in rolling forth large

thoughts in his manhood.

While it is necessary, then, in the first place to secure this solid

foundation of physical health, it must also be observed that the

cultivation of the habit of mental application is quite

indispensable for the education of the student. The maxim that

"Labour conquers all things" holds especially true in the case of

the conquest of knowledge. The road into learning is alike free to

all who will give the labour and the study requisite to gather it;

nor are there any difficulties so great that the student of resolute

purpose may not surmount and overcome them. It was one of the

characteristic expressions of Chatterton, that God had sent his

creatures into the world with arms long enough to reach anything if

they chose to be at the trouble. In study, as in business, energy is

the great thing. There must be the "fervet opus": we must not only

strike the iron while it is hot, but strike it till it is made hot. It is astonishing how much may be accomplished in self-culture by

the energetic and the persevering, who are careful to avail

themselves of opportunities, and use up the fragments of spare time

which the idle permit to run to waste. Thus Ferguson learnt

astronomy from the heavens, while wrapt in a sheep-skin on the

highland hills. Thus Stone learnt mathematics while working as a

journeyman gardener; thus Drew studied the highest philosophy in the

intervals of cobbling shoes; and thus Miller taught himself geology

while working as a day labourer in a quarry.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, as we have already observed, was so earnest a

believer in the force of industry that he held that all men might

achieve excellence if they would but exercise the power of assiduous

and patient working. He held that drudgery lay on the road to

genius, and that there was no limit to the proficiency of an artist

except the limit of his own painstaking. He would not believe in

what is called inspiration, but only in study and labour.

"Excellence," he said, "is never granted to man but as the reward of

labour." "If you have great talents, industry will improve them; if

you have but moderate abilities, industry will supply their

deficiency. Nothing is denied to well-directed labour; nothing is to

be obtained without it." Sir Fowell Buxton was an equal believer in

the power of study; and he entertained the modest idea that he could

do as well as other men if he devoted to the pursuit double the time

and labour that they did. He placed his great confidence in ordinary

means and extraordinary application.

"I have known several men in my life," says Dr. Ross, who may be

recognized in days to come as men of genius, and they were all

plodders, hard-working, intent men. Genius is known by its

works; genius without works is a blind faith, a dumb oracle. But

meritorious works are the result of time and labour, and cannot be

accomplished by intention or by a wish . . . . Every great work is

the result of vast preparatory training. Facility comes by labour. Nothing seems easy, not even walking, that was not difficult at

first. The orator whose eye flashes instantaneous fire, and whose

lips pour out a flood of noble thoughts, startling by their

unexpectedness, and elevating by their wisdom and truth, has learned

his secret by patient repetition, and after many bitter

disappointments." [p.321]

Thoroughness and accuracy are two principal points to be aimed at in

study. Francis Horner, in laying down rules for the cultivation of

his mind, placed great stress upon the habit of continuous

application to one subject for the sake of mastering it thoroughly;

he confined himself, with this object, to only a few books, and

resisted with the greatest firmness "every approach to a habit of

desultory reading." The value of knowledge to any man consists not

in its quantity, but mainly in the good uses to which he can apply

it. Hence a little knowledge, of an exact and perfect character, is

always found more valuable for practical purposes than any extent of

superficial learning.

One of Ignatius Loyola's maxims was, "He who does well one work at a

time, does more than all." By spreading our efforts over too large a

surface we inevitably weaken our force, hinder our progress, and

acquire a habit of fitfulness and ineffective working. Lord St.

Leopards once communicated to Sir Fowell Buxton the mode in which he

had conducted his studies, and thus explained the secret of his

success. "I resolved," said he, "when beginning to read law, to make

everything I acquired perfectly my own, and never to go to a second

thing till I had entirely accomplished the first. Many of my

competitors read as much in a day as I read in a week; but, at the

end of twelve months, my knowledge was as fresh as the day it was

acquired, while theirs had glided away from recollection."

It is not the quantity of study that one gets through, or the amount

of reading, that makes a wise man; but the appositeness of the study

to the purpose for which it is pursued; the concentration of the

mind for the time being on the subject under consideration; and the

habitual discipline by which the whole system of mental application

is regulated. Abernethy was even of opinion that there was a point

of saturation in his own mind, and that if he took into it something

more than it could hold, it only had the effect of pushing something

else out. Speaking of the study of medicine, he said, "If a man has

a clear idea of what he desires to do, he will seldom fail in

selecting the proper means of accomplishing it."

The most profitable study is that which is conducted with a definite

aim and object. By thoroughly mastering any given branch of

knowledge we render it more available for use at any moment. Hence

it is not enough merely to have books, or to know where to read for

information as we want it. Practical wisdom, for the purposes of

life, must be carried about with us, and be ready for use at call. It is not sufficient that we have a fund laid up at home, but not a

farthing in the pocket: we must carry about with us a store of the

current coin of knowledge ready for exchange on all occasions, else

we are comparatively helpless when the opportunity for using it

occurs.

Decision and promptitude are as requisite in self-culture as in

business. The growth of these qualities may be encouraged by

accustoming young people to rely upon their own resources, leaving

them to enjoy as much freedom of action in early life as is

practicable. Too much guidance and restraint hinder the formation of

habits of self-help. They are like bladders tied under the arms of

one who has not taught himself to swim. Want of confidence is

perhaps a greater obstacle to improvement than is generally

imagined. It has been said that half the failures in life arise from

pulling in one's horse while he is leaping. Dr. Johnson was

accustomed to attribute his success to confidence in his own powers. True modesty is quite compatible with a due estimate of one's own

merits, and does not demand the abnegation of all merit. Though

there are those who deceive themselves by putting a false figure

before their ciphers, the want of confidence, the want of faith in

one's self, and consequently the want of promptitude in action, is a

defect of character which is found to stand very much in the way of

individual progress; and the reason why so little is done, is

generally because so little is attempted.

There is usually no want of desire on the part of most persons to

arrive at the results of self-culture, but there is a great aversion

to pay the inevitable price for it, of hard work. Dr. Johnson held

that "impatience of study was the mental disease of the present

generation;" and the remark is still applicable. We may not believe

that there is a royal road to learning, but we seem to believe very

firmly in a "popular" one. In education, we invent labour-saving

processes, seek short cuts to science, learn French and Latin "in

twelve lessons," or "without a master." We resemble the lady of

fashion, who engaged a master to teach her on condition that he did

not plague her with verbs and participles. We get our smattering of

science in the same way; we learn chemistry by listening to a short

course of lectures enlivened by experiments, and when we have

inhaled laughing gas, seen green water turned to red, and phosphorus

burnt in oxygen, we have got our smattering, of which the most that

can be said is, that though it may be better than nothing, it is yet

good for nothing. Thus we often imagine we are being educated while

we are only being amused.

The facility with which young people are thus induced to acquire

knowledge, without study and labour, is not education. It occupies

but does not enrich the mind. It imparts a stimulus for the time,

and produces a sort of intellectual keenness and cleverness; but,

without an implanted purpose and a higher object than mere pleasure,

it will bring with it no solid advantage. In such cases knowledge

produces but a passing impression, a sensation, but no more; it is,

in fact, the merest epicurism of intelligence—sensuous, but

certainly not intellectual. Thus the best qualities of many minds,

those which are evoked by vigorous effort and independent action,

sleep a deep sleep, and are often never called to life, except by

the rough awakening of sudden calamity or suffering, which, in such

cases, comes as a blessing, if it serves to rouse up a courageous

spirit that, but for it, would have slept on.

Accustomed to acquire information under the guise of amusement,

young people will soon reject that which is presented to them under

the aspect of study and labour. Learning their knowledge and science

in sport, they will be too apt to make sport of both; while the

habit of intellectual dissipation, thus engendered, cannot fail, in

course of time, to produce a thoroughly emasculating effect both

upon their mind and character. "Multifarious reading," said

Robertson of Brighton, "weakens the mind like smoking, and is an

excuse for its lying dormant. It is the idlest of all idlenesses,

and leaves more of impotency than any other."

The evil is a growing one, and operates in various ways. Its least

mischief is shallowness; its greatest, the aversion to steady labour

which it induces, and the low and feeble tone of mind which it

encourages. If we would be really wise, we must diligently apply

ourselves, and confront the same continuous application which our

forefathers did; for labour is still, and ever will be, the

inevitable price set upon everything which is valuable. We must be

satisfied to work with a purpose, and wait the results with

patience. All progress, of the best kind, is slow; but to him who

works faithfully and zealously the reward will, doubtless, be

vouchsafed in good time. The spirit of industry, embodied in a man's

daily life, will gradually lead him to exercise his powers on

objects outside himself, of greater dignity and more extended

usefulness. And still we must labour on; for the work of

self-culture is never finished. "To be employed," said the poet

Gray, "is to be happy." "It is better to wear out than rust out,"

said Bishop Cumberland. "Have we not all eternity to rest in?"

exclaimed Arnauld. "Repos ailleurs" was the motto of Marnix de St.

Aldegonde, the energetic and ever-working friend of William the

Silent.

It is the use we make of the powers entrusted to us, which

constitutes our only just claim to respect. He who employs his one

talent aright is as much to be honoured as he to whom ten talents

have been given. There is really no more personal merit attaching to

the possession of superior intellectual powers than there is in the

succession to a large estate. How are those powers used—how is that

estate employed? The mind may accumulate large stores of knowledge

without any useful purpose; but the knowledge must be allied to

goodness and wisdom, and embodied in upright character, else it is

naught. Pestalozzi even held intellectual training by itself to be

pernicious; insisting that the roots of all knowledge must strike

and feed in the soil of the rightly-governed will. The acquisition

of knowledge may, it is true, protect a man against the meaner

felonies of life; but not in any degree against its selfish vices,

unless fortified by sound principles and habits. Hence do we find in

daily life so many instances of men who are well-informed in

intellect, but utterly deformed in character; filled with the

learning of the schools, yet possessing little practical wisdom, and

offering examples for warning rather than imitation. An often quoted

expression at this day is that "Knowledge is power;" but so also are

fanaticism, despotism, and ambition. Knowledge of itself, unless

wisely directed, might merely make bad men more dangerous, and the

society in which it was regarded as the highest good, little better

than a pandemonium.

It is possible that at this day we may even exaggerate the

importance of literary culture. We are apt to imagine that because

we possess many libraries, institutes, and museums, we are making

great progress. But such facilities may as often be a hindrance as a

help to individual self-culture of the highest kind. The possession

of a library, or the free use of it, no more constitutes learning,

than the possession of wealth constitutes generosity. Though we

undoubtedly possess great facilities it is nevertheless true, as of

old, that wisdom and understanding can only become the possession of

individual men by travelling the old road of observation, attention,

perseverance, and industry. The possession of the mere materials of

knowledge is something very different from wisdom and understanding,

which are reached through a higher kind of discipline than that of

reading,—which is often but a mere passive reception of other men's

thoughts; there being little or no active effort of mind in the

transaction. Then how much of our reading is but the indulgence of a

sort of intellectual dram-drinking, imparting a grateful excitement

for the moment, without the slightest effect in improving and

enriching the mind or building up the character. Thus many indulge

themselves in the conceit that they are cultivating their minds,

when they are only employed in the humbler occupation of killing

time, of which perhaps the best that can be said is that it keeps

them from doing worse things.

It is also to be borne in mind that the experience gathered from

books, though often valuable, is but of the nature of learning;

whereas the experience gained from actual life is of the nature of

wisdom; and a small store of the latter is worth vastly more than

any stock of the former. Lord Bolingbroke truly said that "Whatever

study tends neither directly nor indirectly to make us better men

and citizens, is at best but a specious and ingenious sort of