|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XII.

EXAMPLE—MODELS.

|

"Ever their phantoms rise before us,

Our loftier brothers, but one in blood;

By bed and table they lord it o'er us,

With looks of beauty and words of good."

—John

Sterling. |

"Children may be strangled, but Deeds never: they have an

indestructible life, both in and out of our consciousness."—George

Eliot.

"There is no action of man in this life, which is not the

beginning of so long chain of consequences, as that no human

providence is high enough to give us a prospect to the end."—Thomas

of Malmesbury.

EXAMPLE is one of

the most potent of instructors, though it teaches without a tongue.

It is the practical school of mankind, working by action, which is

always more forcible than words. Precept may point to us the

way, but it is silent continuous example, conveyed to us by habits,

and living with us in fact, that carries us along. Good advice

has its weight: but without the accompaniment of a good example it

is of comparatively small influence; and it will be found that the

common saying of "Do as I say, not as I do," is usually reversed in

the actual experience of life.

All persons are more or less apt to learn through the eye

rather than the ear; and, whatever is seen in fact, makes a far

deeper impression than anything that is merely read or heard.

This is especially the case in early youth, when the eye is the

chief inlet of knowledge. Whatever children see they

unconsciously imitate. They insensibly come to resemble those

who are about them—as insects take the colour of the leaves they

feed on. Hence the vast importance of domestic training.

For whatever may be the efficiency of schools, the examples set in

our Homes must always be of vastly greater influence in forming the

characters of our future men and women. The Home is the

crystal of society—the nucleus of national character; and from that

source, be it pure or tainted, issue the habits, principles and

maxims, which govern public as well as private life. The

nation comes from the nursery. Public opinion itself is for

the most part the outgrowth of the home; and the best philanthropy

comes from the fireside. "To love the little platoon we belong

to in society," says Burke, "is the germ of all public affections."

From this little central spot, the human sympathies may extend in an

ever widening circle, until the world is embraced; for, though true

philanthropy, like charity, begins at home, assuredly it does not

end there.

Example in conduct, therefore, even in apparently trivial

matters, is of no light moment, inasmuch as it is constantly

becoming inwoven with the lives of others, and contributing to form

their natures for better or for worse. The characters of

parents are thus constantly repeated in their children; and the acts

of affection, discipline, industry, and self-control, which they

daily exemplify, live and act when all else which may have been

learned through the ear has long been forgotten. Hence a wise

man was accustomed to speak of his children as his "future state."

Even the mute action and unconscious look of a parent may give a

stamp to the character which is never effaced; and who can tell how

much evil act has been stayed by the thought of some good parent,

whose memory their children may not sully by the commission of an

unworthy deed, or the indulgence of an impure thought? The

veriest trifles thus become of importance in influencing the

characters of men. "A kiss from my mother," said West, "made

me a painter." It is on the direction of such seeming trifles

when children that the future happiness and success of men mainly

depend. Fowell Buxton, when occupying an eminent and

influential station in life, wrote to his mother, "I constantly

feel, especially in action and exertion for others, the effects of

principles early implanted by you in my mind." Buxton was also

accustomed to remember with gratitude the obligations which he owed

to an illiterate man, a gamekeeper, named Abraham Plastow, with whom

he played, and rode, and sported—a man who could neither read nor

write, but was full of natural good sense and mother-wit.

"What made him particularly valuable," says Buxton, "were his

principles of integrity and honour. He never said or did a

thing in the absence of my mother of which she would have

disapproved. He always held up the highest standard of

integrity, and filled our youthful minds with sentiments as pure and

as generous as could be found in the writings of Seneca or Cicero.

Such was my first instructor, and, I must add, my best."

Lord Langdale, looking back upon the admirable example set

him by his mother, declared, "If the whole world were put into one

scale, and my mother into the other, the world would kick the beam."

Mrs. Schimmel Penninck, in her old age, was accustomed to call to

mind the personal influence exercised by her mother upon the society

amidst which she moved. When she entered a room it had the

effect of immediately raising the tone of the conversation, and as

if purifying the moral atmosphere—all seeming to breathe more

freely, and stand more erectly. "In her presence," says the

daughter, "I became for the time transformed into another person."

So much does the moral health depend upon the moral atmosphere that

is breathed, and so great is the influence daily exercised by

parents over their children by living a life before their eyes, that

perhaps the best system of parental instruction might be summed up

in these two words: "Improve thyself."

There is something solemn and awful in the thought that there

is not an act done or a word uttered by a human being but carries

with it a train of consequences, the end of which we may never

trace. Not one but, to a certain extent, gives a colour to our

life, and insensibly influences the lives of those about us.

The good deed or word will live, even though we may not see it

fructify, but so will the bad; and no person is so insignificant as

to be sure that his example will not do good on the one hand, or

evil on the other. The spirits of men do not die: they still

live and walk abroad among us. It was a fine and a true

thought uttered by Mr. Disraeli in the House of Commons on the death

of Richard Cobden, that "he was one of those men who, though not

present, were still members of that House, who were independent of

dissolutions, of the caprices of constituencies, and even of the

course of time."

There is, indeed, an essence of immortality in the life of

man, even in this world. No individual in the universe stands

alone; he is a component part of a system of mutual dependencies;

and by his several acts he either increases or diminishes the sum of

human good now and for ever. As the present is rooted in the

past, and the lives and examples of our forefathers still to a great

extent influence us, so are we by our daily acts contributing to

form the condition and character of the future. Man is a fruit

formed and ripened by the culture of all the foregoing centuries;

and the living generation continues the magnetic current of action

and example destined to bind the remotest past with the most distant

future. No man's acts die utterly; and though his body may

resolve into dust and air, his good or his bad deeds will still be

bringing forth fruit after their kind, and influencing future

generations for all time to come. It is in this momentous and

solemn fact that the great peril and responsibility of human

existence lies.

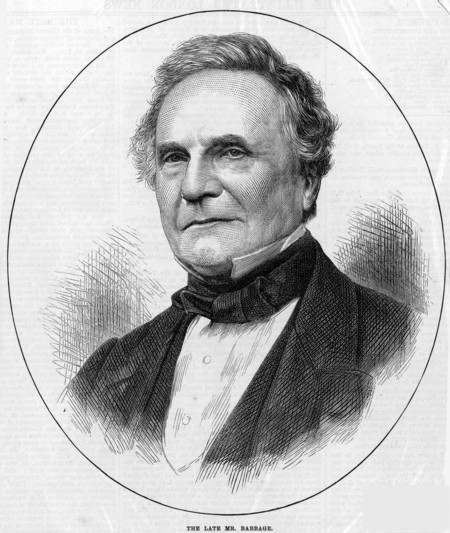

CHARLES

BABBAGE (1791-1871):

English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical

engineer:

originator of the concept of a 'programmable' computer.

Picture: Illustrated London News (1871).

Mr. Babbage has so powerfully expressed this idea in a noble

passage in one of his writings that we here venture to quote his

words: "Every atom," he says,

"impressed with good or ill, retains at once the

motions which philosophers, and sages have imparted to it, mixed and

combined in ten thousand ways with all that is worthless and base;

the air itself is one vast library, on whose pages are written for

ever all that man has ever said or whispered. There, in their

immutable but unerring characters, mixed with the earliest as well

as the latest sighs of mortality, stand for ever recorded vows

unredeemed, promises unfulfilled; perpetuating, in the united

movements of each particle, the testimony of man's changeful will.

But, if the air we breathe is the never-failing historian of the

sentiments we have uttered, earth, air, and ocean, are, in like

manner, the eternal witnesses of the acts we have done; the same

principle of the equality of action and reaction applies to them.

No motion impressed by natural causes, or by human agency, is ever

obliterated. . . . If the Almighty stamped on the brow of the first

murderer the indelible and visible mark of his guilt, He has also

established laws by which every succeeding criminal is not less

irrevocably chained to the testimony of his crime; for every atom of

his mortal frame, through whatever changes its severed particles may

migrate, will still retain adhering to it, through every

combination, some movement derived from that very muscular effort by

which the crime itself was perpetrated."

Thus, every act we do or word we utter, as well as every act

we witness or word we hear, carries with it an influence which

extends over, and gives a colour, not only to the whole of our

future life, but makes itself felt upon the whole frame of society.

We may not, and indeed cannot, possibly, trace the influence working

itself into action in its various ramifications amongst our

children, our friends, or associates, yet there it is assuredly,

working on for ever. And herein lies the great significance of

setting forth a good example,— a silent teaching which even the

poorest and least significant person can practise in his daily life.

There is no one so humble, but that he owes to others this simple

but priceless instruction. Even the meanest condition may thus

be made useful; for the light set in a low place shines as

faithfully as that set upon a hill. Everywhere, and under

almost all circumstances, however externally adverse—in moorland

shielings, in cottage hamlets, in the close alleys of great

towns—the true man may grow. He who tills a space of earth

scarce bigger than is needed for his grave, may work as faithfully,

and to as good purpose, as the heir to thousands. The

commonest workshop may thus be a school of industry, science, and

good morals, on the one hand; or of idleness, folly, and depravity,

on the other. It all depends on the individual men, and the

use they make of the opportunities for good which offer themselves.

A life well spent, a character uprightly sustained, is no

slight legacy to leave to one's children, and to the world: for it

is the most eloquent lesson of virtue and the severest reproof of

vice, while it continues an enduring source of the best kind of

riches. Well for those who can say, as Pope did, in rejoinder

to the sarcasm of Lord Hervey, "I think it enough that my parents,

such as they were, never cost me a blush, and that their son, such

as he is, never cost them a tear."

It is not enough to tell others what they are to do,

but to exhibit the actual example of doing. What Mrs. Chisholm

described to Mrs. Stowe as the secret of her success, applies to all

life. "I found," she said, "that if we want anything done,

we must go to work and do: it is of no use merely to

talk—none whatever." It is poor eloquence that only shows how

a person can talk. Had Mrs. Chisholm rested satisfied with

lecturing, her project, she was persuaded, would never have got

beyond the region of talk; but when people saw what she was doing

and had actually accomplished, they fell in with her views and came

forward to help her. Hence the most beneficent worker is not

he who says the most eloquent things, or even who thinks the most

loftily, but he who does the most eloquent acts.

|

|

|

DR.

THOMAS GUTHRIE

(1803-73):

Scottish preacher and philanthropist;

a founder of the ragged schools.

Picture (Hill & Adamson): Wikipedia. |

True-hearted persons, even in the humblest station in life, who are

energetic doers, may thus give an impulse to good works out of all

proportion, apparently, to their actual station in society.

Thomas Wright might have talked about the reclamation of criminals,

and John Pounds about the necessity for Ragged Schools, and yet done

nothing; instead of which they simply set to work without any other

idea in their minds than that of doing, not talking. And how

the example of even the poorest man may tell upon society, hear what

Dr. Guthrie, the apostle of the Ragged School movement, says of the

influence which the example of John Pounds, the humble Portsmouth

cobbler, exercised upon his own working career:—

"The interest I have been led to

take in this cause is an example of how, in Providence, a man's

destiny—his course of life, like that of a river—may be determined

and affected by very trivial circumstances. It is rather

curious—at least it is interesting to me to remember—that it was by

a picture I was first led to take an interest in ragged schools—by a

picture in an old, obscure, decaying burgh that stands on the shores

of the Frith of Forth, the birthplace of Thomas Chalmers. I

went to see this place many years ago; and, going into an inn for

refreshment, I found the room covered with pictures of shepherdesses

with their crooks, and sailors in holiday attire, not particularly

interesting. But above the chimney-piece there was a large

print, more respectable than its neighbours, which represented a

cobbler's room. The cobbler was there himself, spectacles on

nose, an old shoe between his knees—the massive forehead and firm

mouth indicating great determination of character, and, beneath his

bushy eyebrows, benevolence gleamed out on a number of poor ragged

boys and girls who stood at their lessons round the busy cobbler.

My curiosity was awakened; and in the inscription I read how this

man, John Pounds, a cobbler in Portsmouth, taking pity on the

multitude of poor ragged children left by ministers and magistrates,

and ladies and gentlemen, to go to ruin on the streets—how, like a

good shepherd, he gathered in these wretched outcasts—how he had

trained them to God and to the world—and how, while earning his

daily bread by the sweat of his brow, he had rescued from misery and

saved to society not less than five hundred of these children.

I felt ashamed of myself. I felt reproved for the little I had

done. My feelings were touched. I was astonished at this

man's achievements; and I well remember, in the enthusiasm of the

moment, saying to my companion (and I have seen in my cooler and

calmer moments no reason for unsaying the saying)—'That man is an

honour to humanity, and deserves the tallest monument ever raised

within the shores of Britain.' I took up that man's history,

and I found it animated by the spirit of Him who 'had compassion on

the multitude.' John Pounds was a clever man besides; and,

like Paul, if he could not win a poor boy any other way, he won him

by art. He would be seen chasing a ragged boy along the quays,

and compelling him to come to school, not by the power of a

policeman, but by the power of a hot potato. He knew the love

an Irishman had for a potato; and John Pounds might be seen running

holding under the boy's nose a potato, like an Irishman, very hot,

and with a coat as ragged as himself. When the day comes when

honour will be done to whom honour is due, I can fancy the crowd of

those whose fame poets have sung, and to whose memory monuments have

been raised, dividing like the wave, and, passing the great, and the

noble, and the mighty of the land, this poor, obscure old man

stepping forward and receiving the especial notice of Him who said

'Inasmuch as ye did it to one of the least of these, ye did it also

to Me.'"

The education of character is very much a question of models;

we mould ourselves so unconsciously after the characters, manners,

habits, and opinions of those who are about us. Good rules may

do much, but good models far more; for in the latter we have

instruction in action—wisdom at work. Good admonition and bad

example only build with one hand to pull down with the other.

Hence the vast importance of exercising great care in the selection

of companions, especially in youth. There is a magnetic

affinity in young persons which insensibly tends to assimilate them

to each other's likeness. Mr. Edgeworth was so strongly

convinced that from sympathy they involuntarily imitated or caught

the tone of the company they frequented, that he held it to be of

the most essential importance that they should be taught to select

the very best models. "No company, or good company," was his

motto. Lord Collingwood, writing to a young friend, said,

"Hold it as a maxim that you had better be alone than in mean

company. Let your companions be such as yourself, or superior;

for the worth of a man will always be ruled by that of his company."

It was a remark of the famous Dr. Sydenham that everybody some time

or other would be the better or the worse for having but spoken to a

good or a bad man. As Sir Peter Lely made it a rule never to

look at a bad picture if he could help it, believing that whenever

he did so his pencil caught a taint from it, so, whoever chooses to

gaze often upon a debased specimen of humanity and to frequent his

society, cannot help gradually assimilating himself to that sort of

model.

It is therefore advisable for young men to seek the

fellowship of the good, and always to aim at a higher standard than

themselves. Francis Horner, speaking of the advantages to

himself of direct personal intercourse with high-minded, intelligent

men, said, "I cannot hesitate to decide that I have derived more

intellectual improvement from them than from all the books I have

turned over." Lord Shelburne (afterwards Marquis of

Lansdowne), when a young man, paid a visit to the venerable

Malesherbes, and was so much impressed by it, that he said,—"I have

travelled much, but I have never been so influenced by personal

contact with any man; and if I ever accomplish any good in the

course of my life, I am certain that the recollection of M. de

Malesherbes will animate my soul." So Fowell Buxton was always

ready to acknowledge the powerful influence exercised upon the

formation of his character in early life by the example of the

Gurney family: "It has given a colour to my life," he used to say.

Speaking of his success at the Dublin University, he confessed, "I

can ascribe it to nothing but my Earlham visits." It was from

the Gurneys he "caught the infection" of self-improvement.

Contact with the good never fails to impart good, and we

carry away with us some of the blessing, as travellers' garments

retain the odour of the flowers and shrubs through which they have

passed. Those who knew the late John Sterling intimately, have

spoken of the beneficial influence which he exercised on all with

whom he came into personal contact. Many owed to him their

first awakening to a higher being; from him they learnt what they

were, and what they ought to be. Mr. Trench says of him:—"It

was impossible to come in contact with his noble nature without

feeling one's self in some measure ennobled and lifted up,

as I ever felt when I left him, into a higher region of objects and

aims than that in which one is tempted habitually to dwell."

It is thus that the noble character always acts; we become

insensibly elevated by him, and cannot help feeling as he does and

acquiring the habit of looking at things in the same light.

Such is the magical action and reaction of minds upon each other.

|

|

|

LUIGI

CHERUBINI

(1760-1842):

Italian composer, mostly of opera and sacred

music. Much admired by Beethoven.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

Artists, also, feel themselves elevated by contact with artists

greater than themselves. Thus Haydn's genius was first fired

by Handel. Hearing him play, Haydn's ardour for musical

composition was at once excited, and but for this circumstance, he

himself believed that he would never have written the 'Creation.'

Speaking of Handel, he said, "When he chooses, he strikes like the

thunderbolt;" and at another time, "There is not a note of him but

draws blood." Scarlatti was another of Handel's ardent

admirers, following him all over Italy; afterwards, when speaking of

the great master, he would cross himself in token of admiration.

True artists never fail generously to recognise each other's

greatness. Thus Beethoven's admiration for Cherubini was

regal: and he ardently hailed the genius of Schubert: "Truly," said

he, "in Schubert dwells a divine fire." When Northcote was a

mere youth he had such an admiration for Reynolds that, when the

great painter was once attending a public meeting down in

Devonshire, the boy pushed through the crowd, and got so near

Reynolds as to touch the skirt of his coat, "which I did," says

Northcote, "with great satisfaction to my mind,"—a true touch of

youthful enthusiasm in its admiration of genius.

The example of the brave is an inspiration to the timid,

their presence thrilling through every fibre. Hence the

miracles of valour so often performed by ordinary men under the

leadership of the heroic. The very recollection of the deeds

of the valiant stirs men's blood like the sound of a trumpet.

Ziska bequeathed his skin to be used as a drum to inspire the valour

of the Bohemians. When Scanderbeg, prince of Epirus, was dead,

the Turks wished to possess his bones, that each might wear a piece

next his heart, hoping thus to secure some portion of the courage he

had displayed while living, and which they had so often experienced

in battle. When the gallant Douglas, bearing the heart of

Bruce to the Holy Land, saw one of his knights surrounded and sorely

pressed by the Saracens, he took from his neck the silver case

containing the hero's bequest, and throwing it amidst the thickest

press of his foes, cried, "Pass first in fight, as thou wert wont to

do, and Douglas will follow thee, or die;" and so saying, he rushed

forward to the place where it fell, and was there slain.

The chief use of biography consists in the noble models of

character in which it abounds. Our great forefathers still

live among us in the records of their lives, as well as in the acts

they have done, which live also; still sit by us at table, and hold

us by the hand; furnishing examples for our benefit, which we may

still study, admire and imitate. Indeed, whoever has left

behind him the record of a noble life, has bequeathed to posterity

an enduring source of good, for it serves as a model for others to

form themselves by in all time to come; still breathing fresh life

into men, helping them to reproduce his life anew, and to illustrate

his character in other forms. Hence a book containing the life

of a true man is full of precious seed. It is a still living

voice: it is an intellect. To use Milton's words, "it is the

precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on

purpose to a life beyond life." Such a book never ceases to

exercise an elevating and ennobling influence. But, above all,

there is the Book containing the very highest Example set before us

to shape our lives by in this world—the most suitable for all the

necessities of our mind and heart—an example which we can only

follow afar off and feel after,

|

"Like plants or vines which never saw the

sun,

But dream of him and guess where he may be,

And do their best to climb and get to him." |

Again, no young man can rise from the perusal of such lives

as those of Buxton and Arnold, without feeling his mind and heart

made better, and his best resolves invigorated. Such

biographies increase a man's self-reliance by demonstrating what men

can be, and what they can do; fortifying his hopes and elevating his

aims in life. Sometimes a young man discovers himself in a

biography, as Correggio felt within him the risings of genius on

contemplating the works of Michael Angelo: "And I too, am a

painter," he exclaimed. Sir Samuel Romilly, in his

autobiography, confessed himself to have been powerfully influenced

by the life of the great and noble-minded French Chancellor

Daguesseau:—"The works of Thomas," says he, "had fallen into my

hands, and I had read with admiration his 'Eloge of Daguesseau;' and

the career of honour which he represented that illustrious

magistrate to have run, excited to a great degree my ardour and

ambition, and opened to my imagination new paths of glory."

Franklin was accustomed to attribute his usefulness and

eminence to his having early read Cotton Mather's 'Essays to do

Good'—a book which grew out of Mather's own life. And see how

good example draws other men after it, and propagates itself through

future generations in all lands. For Samuel Drew avers that he

framed his own life, and especially his business habits, after the

model left on record by Benjamin Franklin. Thus it is

impossible to say where a good example may not reach, or where it

will end, if indeed it have an end. Hence the advantage, in

literature as in life, of keeping the best society, reading the best

books, and wisely admiring and imitating the best things we find in

them. "In literature," said Lord Dudley, "I am fond of

confining myself to the best company, which consists chiefly of my

old acquaintance, with whom I am desirous of becoming more intimate;

and I suspect that nine times out of ten it is more profitable, if

not more agreeable, to read an old book over again, than to read a

new one for the first time."

Sometimes a book containing a noble exemplar of life, taken

up at random, merely with the object of reading it as a pastime, has

been known to call forth energies whose existence had not before

been suspected. Alfieri was first drawn with passion to

literature by reading 'Plutarch's Lives.' Loyola, when a

soldier serving at the siege of Pampeluna, and laid up by a

dangerous wound in his leg, asked for a book to divert his thoughts:

the 'Lives of the Saints' was brought to him, and its perusal so

inflamed his mind, that he determined thenceforth to devote himself

to the founding of a religious order. Luther, in like manner,

was inspired to undertake the great labours of his life by a perusal

of the 'Life and Writings of John Huss.' Dr. Wolff was

stimulated to enter upon his missionary career by reading the 'Life

of Francis Xavier;' and the book fired his youthful bosom with a

passion the most sincere and ardent to devote himself to the

enterprise of his life. William Carey, also, got the first

idea of entering upon his sublime labours as a missionary from a

perusal of the Voyages of Captain Cook.

Francis Horner was accustomed to note in his diary and

letters the books by which he was most improved and influenced.

Amongst these were Condorcet's 'Eloge of Haller,' Sir Joshua

Reynolds' 'Discourses,' the writings of Bacon, and 'Burnet's Account

of Sir Matthew Hale.' The perusal of the last-mentioned

book—the portrait of a prodigy of labour—Horner says, filled him

with enthusiasm. Of Condorcet's 'Eloge of Haller,' he said: "I

never rise from the account of such men without a sort of thrilling

palpitation about me, which I know not whether I should call

admiration, ambition, or despair." And speaking of the

'Discourses' of Sir Joshua Reynolds, he said: "Next to the writings

of Bacon, there is no book which has more powerfully impelled me to

self-culture. He is one of the first men of genius who has

condescended to inform the world of the steps by which greatness is

attained. The confidence with which he asserts the omnipotence

of human labour has the effect of familiarising his reader with the

idea that genius is an acquisition rather than a gift; whilst with

all there is blended so naturally and eloquently the most elevated

and passionate admiration of excellence, that upon the whole there

is no book of a more inflammatory effect." It is

remarkable that Reynolds himself attributed his first passionate

impulse towards the study of art, to reading Richardson's account of

a great painter; and Haydon was in like manner afterwards inflamed

to follow the same pursuit by reading of the career of Reynolds.

Thus the brave and aspiring life of one man lights a flame in the

minds of others of like faculties and impulse; and where there is

equally vigorous effort, like distinction and success will almost

surely follow. Thus the chain of example is carried down

through time in an endless succession of links,—admiration exciting

imitation, and perpetuating the true aristocracy of genius.

One of the most valuable, and one of the most infectious

examples which can be set before the young, is that of cheerful

working. Cheerfulness gives elasticity to the spirit.

Spectres fly before it; difficulties cause no despair, for they are

encountered with hope, and the mind acquires that happy disposition

to improve opportunities which rarely fails of success. The

fervent spirit is always a healthy and happy spirit; working

cheerfully itself, and stimulating others to work. It confers

a dignity on even the most ordinary occupations. The most

effective work, also, is usually the full-hearted work—that which

passes through the hands or the head of him whose heart is glad.

Hume was accustomed to say that he would rather possess a cheerful

disposition—inclined always to look at the bright side of

things—than with a gloomy mind to be the master of an estate of ten

thousand a year. Granville Sharp, amidst his indefatigable

labours on behalf of the slave, solaced himself in the evenings by

taking part in glees and instrumental concerts at his brother's

house, singing, or playing on the flute, the clarinet, or the oboe;

and, at the Sunday evening oratorios, when Handel was played, he

beat the kettle-drums. He also indulged, though sparingly, in

caricature drawing. Fowell Buxton also was an eminently

cheerful man; taking special pleasure in field sports, in riding

about the country with his children, and in mixing in all their

domestic amusements.

In another sphere of action, Dr. Arnold was a noble and a

cheerful worker, throwing himself into the great business of his

life, the training and teaching of young men, with his whole heart

and soul. It is stated in his admirable biography, that "the

most remarkable thing in the Laleham circle was the wonderful

healthiness of tone which prevailed there. It was a place

where a new comer at once felt that a great and earnest work was

going forward. Every pupil was made to feel that there was a

work for him to do; that his happiness, as well as his duty, lay in

doing that work well. Hence an indescribable zest was

communicated to a young man's feeling about life; a strange joy came

over him on discerning that he had the means of being useful, and

thus of being happy; and a deep respect and ardent attachment sprang

up towards him who had taught him thus to value life and his own

self, and his work and mission in the world. All this was

founded on the breadth and comprehensiveness of Arnold's character,

as well as its striking truth and reality; on the unfeigned regard

he had for work of all kinds, and the sense he had of its value,

both for the complex aggregate of society and the growth and

protection of the individual. In all this there was no

excitement; no predilection for one class of work above another; no

enthusiasm for any one-sided object; but a humble, profound, and

most religious consciousness that work is the appointed calling of

man on earth; the end for which his various faculties were given;

the element in which his nature is ordained to develop itself, and

in which his progressive advance towards heaven is to lie."

Among the many valuable men trained for public life and usefulness

by Arnold, was the gallant Hodson, of Hodson's Horse, who, writing

home from India, many years after, thus spoke of his revered master:

"The influence he produced has been most lasting and striking in its

effects. It is felt even in India; I cannot say more than

that."

The useful influence which a right-hearted man of energy and

industry may exercise amongst his neighbours and dependants, and

accomplish for his country, cannot, perhaps, be better illustrated

than by the career of Sir John Sinclair; characterized by the Abbé

Gregoire as "the most indefatigable man in Europe." He was

originally a country laird, born to a considerable estate situated

near John o' Groat's House, almost beyond the beat of civilization,

in a bare wild country fronting the stormy North Sea. His father

dying while he was a youth of sixteen, the management of the family

property thus early devolved upon him; and at eighteen he began a

course of vigorous improvement in the county of Caithness, which

eventually spread all over Scotland. Agriculture then was in a most

backward state; the fields were unenclosed, the lands undrained; the

small farmers of Caithness were so poor that they could scarcely

afford to keep a horse or shelty; the hard work was chiefly done,

and the burdens borne, by the women; and if a cottier lost a horse

it was not unusual for him to marry a wife as the cheapest

substitute. The country was without roads or bridges; and drovers

driving their cattle south had to swim the rivers along with their

beasts. The chief track leading into Caithness lay along a high

shelf on a mountain side, the road being some hundred feet of clear

perpendicular height above the sea which dashed below. Sir John,

though a mere youth, determined to make a new road over the hill of

Ben Cheilt, the old let-alone proprietors, however, regarding his

scheme with incredulity and derision. But he himself laid out the

road, assembled some twelve hundred workmen early one summer's

morning, set them simultaneously to work, superintending their

labours, and stimulating them by his presence and example; and

before night, what had been a dangerous sheep track, six miles in

length, hardly passable for led horses, was made practicable for

wheel-carriages as if by the power of magic. It was an admirable

example of energy and well-directed labour, which could not fail to

have a most salutary influence upon the surrounding population. He

then proceeded to make more roads, to erect mills, to build bridges,

and to enclose and cultivate the waste lands. He introduced improved

methods of culture, and regular rotation of crops, distributing

small premiums to encourage industry; and he thus soon quickened the

whole frame of society within reach of his influence, and infused an

entirely new spirit into the cultivators of the soil. From being one

of the most inaccessible districts of the north—the very ultima

Thule of civilization—Caithness became a pattern county for its

roads, its agriculture, and its fisheries. In Sinclair's youth, the

post was carried by a runner only once a week, and the young baronet

then declared that he would never rest till a coach drove daily to

Thurso. The people of the neighbourhood could not believe in any

such thing, and it became a proverb in the county to say of any

utterly impossible scheme, "On, ay, that will come to pass when Sit

John sees the daily mail at Thurso!" But Sir John lived to see his

dream realized, and the daily mail established to Thurso.

The circle of his benevolent operations gradually widened. Observing

the serious deterioration which had taken place in the quality of

British wool,—one of the staple commodities of the country,—he

forthwith, though but a private and little-known country gentleman,

devoted himself to its improvement. By his personal exertions he

established the British Wool Society for the purpose, and himself

led the way to practical improvement by importing 800 sheep from all

countries, at his own expense. The result was, the introduction into

Scotland of the celebrated Cheviot breed. Sheep farmers scouted the

idea of south country flocks being able to thrive in the far north.

But Sir John persevered; and in a few years there were not fewer

than 300,000 Cheviots diffused over the four northern counties

alone. The value of all grazing land was thus enormously increased;

and Scotch estates, which before were comparatively worthless, began

to yield large rentals.

SIR JOHN

SINCLAIR

(1754-1835):

Scottish politician, writer on finance and agriculture.

Picture: Wikipedia.

Returned by Caithness to Parliament, in which he remained for thirty

years, rarely missing a division, his position gave him farther

opportunities of usefulness, which he did not neglect to employ. Mr.

Pitt, observing his persevering energy in all useful public

projects, sent for him to Downing Street, and voluntarily proposed

his assistance in any object he might have in view. Another man

might have thought of himself and his own promotion; but Sir John

characteristically replied, that he desired no favour for himself,

but intimated that the reward most gratifying to his feelings would

be Mr. Pitt's assistance in the establishment of a National Board of

Agriculture. Arthur Young laid a bet with the baronet that his

scheme would never be established, adding; "Your Board of

Agriculture will be in the moon!" But vigorously setting to work, he

roused public attention to the subject, enlisted a majority of

Parliament on his side, and eventually established the Board, of

which he was appointed President. The result of its action need not

be described, but the stimulus which it gave to agriculture and

stock-raising was shortly felt throughout the whole United Kingdom,

and tens of thousands of acres were redeemed from barrenness by its

operation. He was equally indefatigable in encouraging the

establishment of fisheries; and the successful founding of these

great branches of British industry at Thurso and Wick was mainly due

to his exertions. He urged for long years, and at length succeeded

in obtaining the enclosure of a harbour for the latter place, which

is perhaps the greatest and most prosperous fishing town in the

world.

Sir John threw his personal energy into every work in which he

engaged, rousing the inert, stimulating the idle, encouraging the

hopeful, and working with all. When a French invasion was

threatened, he offered to Mr. Pitt to raise a regiment on his own

estate, and he was as good as his word. He went down to the north,

and raised a battalion of 600 men, afterwards increased to 1,000; and

it was admitted to be one of the finest volunteer regiments ever

raised, inspired throughout by his own noble and patriotic spirit. While commanding officer of the camp at Aberdeen he held the offices

of a Director of the Bank of Scotland, Chairman of the British Wool

Society, Provost of Wick, Director of the British Fishery Society,

Commissioner for issuing Exchequer Bills, Member of Parliament for

Caithness, and President of the Board of Agriculture. Amidst all

this multifarious and self-imposed work, he even found time to write

books, enough of themselves to establish a reputation. When Mr.

Rush, the American Ambassador, arrived in England, he relates that

he inquired of Mr. Coke of Holkham, what was the best work on

Agriculture, and was referred to Sir John Sinclair's; and when he

further asked of Mr. Vansittart, Chancellor of the Exchequer, what

was the best work on British Finance, he was again referred to a

work by Sir John Sinclair, his 'History of the Public Revenue.' But

the great monument of his indefatigable industry, a work that would

have appalled other men, but only served to rouse and sustain his

energy, was his 'Statistical Account of Scotland,' in twenty-one

volumes, one of the most valuable practical works ever published in

any age or country. Amid a host of other pursuits it occupied him

nearly eight years of hard labour, during which he received, and

attended to, upwards of 20,000 letters on the subject. It was a

thoroughly patriotic undertaking, from which he derived no personal

advantage whatever, beyond the honour of having completed it. The

whole of the profits were assigned by him to the Society for the

Sons of the Clergy in Scotland. The publication of the book led to

great public improvements; it was followed by the immediate

abolition of several oppressive feudal rights, to which it called

attention; the salaries of schoolmasters and clergyman in many

parishes were increased; and an increased stimulus was given to

agriculture throughout Scotland. Sir John then publicly offered to

undertake the much greater labour of collecting and publishing a

similar Statistical Account of England; but unhappily the then

Archbishop of Canterbury refused to sanction it, lest it should

interfere with the tithes of the clergy, and the idea was abandoned.

A remarkable illustration of his energetic promptitude was the

manner in which he once provided, on a great emergency, for the

relief of the manufacturing districts. In 1793 the stagnation

produced by the war led to an unusual number of bankruptcies, and

many of the first houses in Manchester and Glasgow were tottering,

not so much from want of property, but because the usual sources of

trade and credit were for the time closed up. A period of intense

distress amongst the labouring classes seemed imminent, when Sir

John urged, in Parliament, that Exchequer notes to the amount of

five millions should be issued immediately as a loan to such

merchants as could give security. This suggestion was adopted, and

his offer to carry out his plan, in conjunction with certain members

named by him, was also accepted. The vote was passed late at night,

and early next morning Sir John, anticipating the delays of officialism and red tape, proceeded to bankers in the city, and

borrowed of them, on his own personal security, the sum of £70,000,

which he despatched the same evening to those merchants who were in

the most urgent need of assistance. Pitt meeting Sir John in the

House, expressed his great regret that the pressing wants of

Manchester and Glasgow could not be supplied so soon as was

desirable, adding, "The money cannot be raised for some days." "It

is already gone! it left London by to-night's mail!" was Sir John's

triumphant reply; and in afterwards relating the anecdote he added,

with a smile of pleasure, "Pitt was as much startled as if I had

stabbed him." To the last this great, good man worked on usefully

and cheerfully, setting a great example for his family and for his

country. In so laboriously seeking others' good, it might be said

that he found his own—not wealth, for his generosity seriously

impaired his private fortune, but happiness, and self-satisfaction,

and the peace that passes knowledge. A great patriot, with

magnificent powers of work, he nobly did his duty to his country;

yet he was not neglectful of his own household and home. His sons

and daughters grew up to honour and usefulness; and it was one of

the proudest things Sir John could say, when verging on his

eightieth year, that he had lived to see seven sons grown up, not

one of whom had incurred a debt he could not pay, or caused him a

sorrow that could have been avoided.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIII.

CHARACTER—THE TRUE GENTLEMAN.

|

"For who can always act? but he,

To whom a thousand memories call,

Not being less but more than all

The gentleness he seemed to be,

But seemed the thing he was, and join'd

Each office of the social hour

To noble manners, as the flower

And native growth of noble mind;

And thus he bore without abuse

The grand old name of Gentleman.'–Tennyson. |

|

"Es billet ein Talent sich in der Stille,

Sich ein Charakter in dem Strom der Welt."—Goethe. |

"That which raises a country, that

which strengthens a country, and that which dignifies a

country,—that which spreads her power, creates her moral influence,

and makes her respected and submitted to, bends the heart of

millions, and bows down the pride of nations to her—the instrument

of obedience, the fountain of supremacy, the true throne, crown, and

sceptre of a nation;—this aristocracy is not an aristocracy of

blood, not an aristocracy of fashion, not an aristocracy of talent

only; it is an aristocracy of Character. That is the true

heraldry of man."—The Times.

THE crown and

glory of life is Character. It is the noblest possession of a

man, constituting a rank in itself, and an estate in the general

goodwill; dignifying every station, and exalting every position in

society. It exercises a greater power than wealth, and secures

all the honour without the jealousies of fame. It carries with

it an influence which always tells; for it is the result of proved

honour, rectitude, and consistency—qualities which, perhaps more

than any other, command the general confidence and respect of

mankind.

Character is human nature in its best form. It is moral

order embodied in the individual. Men of character are not

only the conscience of society, but in every well-governed State

they are its best motive power; for it is moral qualities in the

main which rule the world. Even in war, Napoleon said the

moral is to the physical as ten to one. The strength, the

industry, and the civilisation of nations—all depend upon individual

character; and the very foundations of civil security rest upon it.

Laws and institutions are but its outgrowth. In the just

balance of nature, individuals, nations, and races, will obtain just

so much as they deserve, and no more. And as effect finds its

cause, so surely does quality of character amongst a people produce

its befitting results.

|

|

|

FRANCIS

HORNER

(1778-1817):

Scottish M.P.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

Though a man have comparatively little culture, slender abilities,

and but small wealth, yet, if his character be of sterling worth, he

will always command an influence, whether it be in the workshop, the

counting-house, the mart, or the senate. Canning wisely wrote

in 1801, "My road must be through Character to power; I will try no

other course; and I am sanguine enough to believe that this course,

though not perhaps the quickest, is the surest." You may

admire men of intellect; but something more is necessary before you

will trust them. Hence Lord John Russell once observed in a

sentence full of truth, "It is the nature of party in England to ask

the assistance of men of genius, but to follow the guidance of men

of character." This was strikingly illustrated in the career

of the late Francis Horner—a man of whom Sydney Smith said that the

Ten Commandments were stamped upon his countenance. "The

valuable and peculiar light," says Lord Cockburn, "in which his

history is calculated to inspire every right-minded youth, is this.

He died at the age of thirty-eight: possessed of greater public

influence than any other private man; and admired, beloved, trusted,

and deplored by all, except the heartless or the base. No

greater homage was ever paid in Parliament to any deceased member.

Now let every young man ask—how was this attained? By rank?

He was the son of an Edinburgh merchant. By wealth? Neither

he, nor any of his relations, ever had a superfluous sixpence.

By office? He held but one, and only for a few years, of no

influence, and with very little pay. By talents? His

were not splendid, and he had no genius. Cautious and slow,

his only ambition was to be right. By eloquence? He

spoke in calm, good taste, without any of the oratory that either

terrifies or seduces. By any fascination of manner? His

was only correct and agreeable. By what, then, was it?

Merely by sense, industry, good principles, and a good

heart—qualities which no well-constituted mind need ever despair of

attaining. It was the force of his character that raised him;

and this character not impressed upon him by nature, but formed, out

of no peculiarly fine elements, by himself. There were many in

the House of Commons of far greater ability and eloquence. But

no one surpassed him in the combination of an adequate portion of

these with moral worth. Horner was born to show what moderate

powers, unaided by anything whatever except culture and goodness,

may achieve, even when these powers are displayed amidst the

competition and jealousy of public life."

Franklin, also, attributed his success as a public man, not

to his talents or his powers of speaking—for these were but

moderate—but to his known integrity of character. Hence it

was, he says, "that I had so much weight with my fellow citizens.

I was but a bad speaker, never eloquent, subject to much hesitation

in my choice of words, hardly correct in language, and yet I

generally carried my point." Character creates confidence in

men in high station as well as in humble life. It was said of

the first Emperor Alexander of Russia, that his personal character

was equivalent to a constitution. During the wars of the

Fronde, Montaigne was the only man amongst the French gentry who

kept his castle gates unbarred; and it was said of him, that his

personal character was a better protection for him than a regiment

of horse would have been.

That character is power, is true in a much higher sense than

that knowledge is power. Mind without heart, intelligence

without conduct, cleverness without goodness, are powers in their

way, but they may be powers only for mischief. We may be

instructed or amused by them; but it is sometimes as difficult to

admire them as it would be to admire the dexterity of a pickpocket

or the horsemanship of a highwayman.

Truthfulness, integrity, and goodness—qualities that hang not

on any man's breath—form the essence of manly character, or, as one

of our old writers has it, "that inbred loyalty unto Virtue which

can serve her without a livery." He who possesses these

qualities, united with strength of purpose, carries with him a power

which is irresistible. He is strong to do good, strong to

resist evil, and strong to bear up under difficulty and misfortune.

When Stephen of Colonna fell into the hands of his base assailants,

and they asked him in derision, "Where is now your fortress?"

"Here," was his bold reply, placing his hand upon his heart.

It is in misfortune that the character of the upright man shines

forth with the greatest lustre; and when all else fails, he takes

stand upon his integrity and his courage.

The rules of conduct followed by Lord Erskine—a man of

sterling independence of principle and scrupulous adherence to

truth—are worthy of being engraven on every young man's heart.

"It was a first command and counsel of my earliest youth," he said,

always to do what my conscience told me to be a duty, and to leave

the consequence to God. I shall carry with me the memory, and

I trust the practice, of this parental lesson to the grave. I

have hitherto followed it, and I have no reason to complain that my

obedience to it has been a temporal sacrifice. I have found

it, on the contrary, the road to prosperity and wealth, and I shall

point out the same path to my children for their pursuit,"

Every man is bound to aim at the possession of a good

character as one of the highest objects of life. The very

effort to secure it by worthy means will furnish him with a motive

for exertion; and his idea of manhood, in proportion as it is

elevated, will steady and animate his motive. It is well to

have a high standard of life, even though we may not be able

altogether to realize it. "The youth," says Mr. Disraeli, "who

does not look up will look down; and the spirit that does not soar

is destined perhaps to grovel." George Herbert wisely writes,

|

"Pitch thy behaviour low, thy projects

high,

So shall thou humble and magnanimous be.

Sink not in spirit; who aimeth at the sky

Shoots higher much than he that means a tree." |

He who has a high standard of living and thinking will certainly do

better than he who has none at all. "Pluck at a gown of gold,"

says the Scotch proverb, "and you may get a sleeve o't."

Whoever tries for the highest results cannot fail to reach a point

far in advance of that from which he started; and though the end

attained may fall short of that proposed, still, the very effort to

rise, of itself cannot fail to prove permanently beneficial.

There are many counterfeits of character, but the genuine

article is difficult to be mistaken. Some, knowing its money

value, would assume its disguise for the purpose of imposing upon

the unwary. Colonel Charteris said to a man distinguished for

his honesty, "I would give a thousand pounds for your good name."

"Why?" "Because I could make ten thousand by it," was the

knave's reply.

SIR ROBERT

PEEL (1788-1850):

twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Picture: Wikipedia.

Integrity in word and deed is the backbone of character; and

loyal adherence to veracity its most prominent characteristic.

One of the finest testimonies to the character of the late Sir

Robert Peel was that borne by the Duke of Wellington in the House of

Lords, a few days after the great statesman's death. "Your

lordships," he said, "must all feel the high and honourable

character of the late Sir Robert Peel. I was long connected

with him in public life. We were both in the councils of our

Sovereign together, and I had long the honour to enjoy his private

friendship. In all the course of my acquaintance with him I

never knew a man in whose truth and justice I had greater

confidence, or in whom I saw a more invariable desire to promote the

public service. In the whole course of my communication with

him, I never knew an instance in which he did not show the strongest

attachment to truth; and I never saw in the whole course of my life

the smallest reason for suspecting that he stated anything which he

did not firmly believe to be the fact." And this high-minded

truthfulness of the statesman was no doubt the secret of no small

part of his influence and power.

There is a truthfulness in action as well as in words, which

is essential to uprightness of character. A man must really be

what he seems or purposes to be. When an American gentleman

wrote to Granville Sharp, that from respect for his great virtues he

had named one of his sons after him, Sharp replied: "I must request

you to teach him a favourite maxim of the family whose name you have

given him—Always endeavour to be really what you would wish to

appear. This maxim, as my father informed me, was

carefully and humbly practised by his father, whose sincerity, as a

plain and honest man, thereby became the principal feature of his

character, both in public and private life." Every man who

respects himself, and values the respect of others, will carry out

the maxim in act—doing honestly what he proposes to do—putting the

highest character into his work, stamping nothing, but priding

himself upon his integrity and conscientiousness. Once

Cromwell said to Bernard,—a clever but somewhat unscrupulous lawyer,

"I understand that you have lately been vastly wary in your conduct;

do not be too confident of this; subtlety may deceive you, integrity

never will." Men whose acts are at direct variance with their

words, command no respect, and what they say has but little weight;

even truths, when uttered by them, seem to come blasted from their

lips.

The true character acts rightly, whether in secret or in the

sight of men. That boy was well trained who, when asked why he

did not pocket some pears, for nobody was there to see, replied,

"Yes, there was: I was there to see myself; and I don't intend ever

to see myself do a dishonest thing." This is a simple but not

inappropriate illustration of principle, or conscience, dominating

in the character, and exercising a noble protectorate over it; not

merely a passive influence, but an active power regulating the life.

Such a principle goes on moulding the character hourly and daily,

growing with a force that operates every moment. Without this

dominating influence, character has no protection, but is constantly

liable to fall away before temptation; and every such temptation

succumbed to, every act of meanness or dishonesty, however slight,

causes self-degradation. It matters not whether the act be

successful or not, discovered or concealed; the culprit is no longer

the same, but another person; and he is pursued by a secret

uneasiness, by self-reproach, or the workings of what we call

conscience, which is the inevitable doom of the guilty.

And here it may be observed how greatly the character may be

strengthened and supported by the cultivation of good habits.

Man, it has been said, is a bundle of habits, and habit is second

nature. Metastasio entertained so strong an opinion as to the

power of repetition in act and thought, that he said, "All is habit

in mankind, even virtue itself." Butler, in his 'Analogy,'

impresses the importance of careful self-discipline and firm

resistance to temptation, as tending to make virtue habitual, so

that at length it may become more easy to be good than to give way

to sin. "As habits belonging to the body," he says, "are

produced by external acts, so habits of the mind are produced by the

execution of inward practical purposes, i.e., carrying them into

act, or acting upon them—the principles of obedience, veracity,

justice, and charity." And again, Lord Brougham says, when

enforcing the immense importance of training and example in youth,

"I trust everything under God to habit, on which, in all ages, the

lawgiver, as well as the schoolmaster, has mainly placed his

reliance; habit, which makes everything easy, and casts the

difficulties upon the deviation from a wonted course." Thus,

make sobriety a habit, and intemperance will be hateful; make

prudence a habit, and reckless profligacy will become revolting to

every principle of conduct which regulates the life of the

individual. Hence the necessity for the greatest care and

watchfulness against the inroad of any evil habit; for the character

is always weakest at that point at which it has once given way; and

it is long before a principle restored can become so firm as one

that has never been moved. It is a fine remark of a Russian

writer, that "Habits are a necklace of pearls: untie the knot, and

the whole unthreads."

Wherever formed, habit acts involuntarily, and without

effort; and, it is only when you oppose it, that you find how

powerful it has become. What is done once and again, soon

gives facility and proneness. The habit at first may seem to

have no more strength than a spider's web; but, once formed, it

binds as with a chain of iron. The small events of life, taken

singly, may seem exceedingly unimportant, like snow that falls

silently, flake by flake; yet accumulated, these snow-flakes form

the avalanche.

Self-respect, self-help, application, industry, integrity—all

are of the nature of habits, not beliefs. Principles, in fact,

are but the names which we assign to habits; for the principles are

words, but the habits are the things themselves: benefactors or

tyrants, according as they are good or evil. It thus happens

that as we grow older, a portion of our free activity and

individuality becomes suspended in habit; our actions become of the

nature of fate; and we are bound by the chains which we have woven

around ourselves.

It is indeed scarcely possible to over-estimate the

importance of training the young to virtuous habits. In them

they are the easiest formed, and when formed they last for life;

like letters cut on the bark of a tree they grow and widen with age.

"Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he

will not depart from it." The beginning holds within it the

end; the first start on the road of life determines the direction

and the destination of the journey; ce n'est quie le premier pas

qui coûte. "Remember," said Lord Collingwood to a young

man whom he loved, "before you are five-and-twenty you must

establish a character that will serve you all your life." As

habit strengthens with age, and character becomes formed, any

turning into a new path becomes more and more difficult.

Hence, it is often harder to unlearn than to learn; and for this

reason the Grecian flute-player was justified who charged double

fees to those pupils who had been taught by an inferior master.

To uproot an old habit is sometimes a more painful thing, and vastly

more difficult, than to wrench out a tooth. Try and reform a

habitually indolent, or improvident, or drunken person, and in a

large majority of cases you will fail. For the habit in each

case has wound itself in and through the life until it has become an

integral part of it, and cannot be uprooted. Hence, as Mr.

Lynch observes, "the wisest habit of all is the habit of care in the

formation of good habits."

Even happiness itself may become habitual. There is a

habit of looking at the bright side of things, and also of looking

at the dark side. Dr. Johnson has said that the habit of

looking at the best side of a thing is worth more to a man than a

thousand pounds a year. And we possess the power, to a great

extent, of so exercising the will as to direct the thoughts upon

objects calculated to yield happiness and improvement rather than

their opposites. In this way the habit of happy thought may be

made to spring up like any other habit. And to bring up men or

women with a genial nature of this sort, a good temper, and a happy

frame of mind, is perhaps of even more importance, in many cases,

than to perfect them in much knowledge and many accomplishments.

As daylight can be seen through very small holes, so little

things will illustrate a person's character. Indeed character

consists in little acts, well and honourably performed; daily life

being the quarry from which we build it up, and rough-hew the habits

which form it. One of the most marked tests of character is

the manner in which we conduct ourselves towards others. A

graceful behaviour towards superiors, inferiors, and equals, is a

constant source of pleasure. It pleases others because it

indicates respect for their personality; but it gives tenfold more

pleasure to ourselves. Every man may to a large extent be a

self-educator in good behaviour, as in everything else; he can be

civil and kind, if he will, though he have not a penny in his purse.

Gentleness in society is like the silent influence of light, which

gives colour to all nature; it is far more powerful than loudness or

force, and far more fruitful. It pushes its way quietly and

persistently, like the tiniest daffodil in spring, which raises the

clod and thrusts it aside by the simple persistency of growing.

Even a kind look will give pleasure and confer happiness.

In one of Robertson of Brighton's letters, he tells of a lady who

related to him "the delight, the tears of gratitude, which she had

witnessed in a poor girl to whom, in passing, I gave a kind look on

going out of church on Sunday. What a lesson! How

cheaply happiness can be given! What opportunities we miss of

doing an angel's work! I remember doing it, full of sad

feelings, passing on, and thinking no more about it; and it gave an

hour's sunshine to a human life, and lightened the load of life to a

human heart for a time!" [p.392]

Morals and manners, which give colour to life, are of much

greater importance than laws, which are but their manifestations.

The law touches us here and there, but manners are about us

everywhere, pervading society like the air we breathe. Good

manners, as we call them, are neither more nor less than good

behaviour; consisting of courtesy and kindness; benevolence being

the preponderating element in all kinds of mutually beneficial and

pleasant intercourse amongst human beings. "Civility," said

Lady Montague, "costs nothing and buys everything." The

cheapest of all things is kindness, its exercise requiring the least

possible trouble and self-sacrifice. "Win hearts," said

Burleigh to Queen Elizabeth, "and you have all men's hearts and

purses." If we would only let nature act kindly, free from

affectation and artifice, the results on social good humour and

happiness would be incalculable. The little courtesies which

form the small change of life, may separately appear of little

intrinsic value, but they acquire their importance from repetition

and accumulation. They are like the spare minutes, or the

groat a day, which proverbially produce such momentous results in

the course of a twelvemonth, or in a lifetime.

|

.jpg) |

|

JOHN

ABERNETHY

F.R.S. (1764-1831):

English surgeon; founder of Barts Medical School.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

Manners are the ornament of action; and there is a way of speaking a

kind word, or of doing a kind thing, which greatly enhances their

value. What seems to be done with a grudge, or as an act of

condescension, is scarcely accepted as a favour. Yet there are

men who pride themselves upon their gruffness; and though they may

possess virtue and capacity, their manner is often such as to render

them almost insupportable. It is difficult to like a man who,

though he may not pull your nose, habitually wounds your

self-respect, and takes a pride in saying disagreeable things to

you. There are others who are dreadfully condescending, and

cannot avoid seizing upon every small opportunity of making their

greatness felt. When Abernethy was canvassing for the office

of surgeon to St. Bartholomew Hospital, he called upon such a

person—a rich grocer, one of the governors. The great man

behind the counter seeing the great surgeon enter, immediately

assumed the grand air towards the supposed suppliant for his vote.

"I presume, Sir, you want my vote and interest at this momentous

epoch of your life." Abernethy, who hated humbugs, and felt

nettled at the tone, replied: "No, I don't: I want a pennyworth of

figs; come, look sharp and wrap them up; I want to be off!"

The cultivation of manner—though in excess it is foppish and

foolish—is highly necessary in a person who has occasion to

negotiate with others in matters of business. Affability and

good breeding may even be regarded as essential to the success of a

man in any eminent station and enlarged sphere of life; for the want

of it has not unfrequently been found in a great measure to

neutralise the results of much industry, integrity, and honesty of

character. There are, no doubt, a few strong tolerant minds

which can bear with defects and angularities of manner, and look

only to the more genuine qualities; but the world at large is not so

forbearant, and cannot help forming its judgments and likings mainly

according to outward conduct.

Another mode of displaying true politeness is consideration

for the opinions of others. It has been said of dogmatism,

that it is only puppyism come to its full growth; and certainly the

worst form this quality can assume, is that of opinionativeness and

arrogance. Let men agree to differ, and, when they do differ,

bear and forbear. Principles and opinions may be maintained

with perfect suavity, without coming to blows or uttering hard

words; and there are circumstances in which words are blows, and

inflict wounds far less easy to heal. As bearing upon this

point, we quote an instructive little parable spoken some time since

by an itinerant preacher of the Evangelical Alliance on the borders

of Wales:—"As I was going to the hills," said he, "early one misty

morning, I saw something moving on a mountain side, so strange

looking that I took it for a monster. When I came nearer to it

I found it was a man. When I came up to him I found he was my

brother."

The inbred politeness which springs from right-heartedness

and kindly feelings, is of no exclusive rank or station. The

mechanic who works at the bench may possess it, as well as the

clergyman or the peer. It is by no means a necessary condition

of labour that it should, in any respect, be either rough or coarse.

The politeness and refinement which distinguish all classes of the

people in many continental countries show that those qualities might

become ours too—as doubtless they will become with increased culture

and more general social intercourse—without sacrificing any of our

more genuine qualities as men. From the highest to the lowest,

the richest to the poorest, to no rank or condition in life has

nature denied her highest boon—the great heart. There never

yet existed a gentleman but was lord of a great heart. And

this may exhibit itself under the hodden grey of the peasant as well

as under the laced coat of the noble. Robert Burns was once

taken to task by a young Edinburgh blood, with whom he was walking

for recognising an honest farmer in the open street. "Why you

fantastic gomeral," exclaimed Burns, "it was not the great coat, the

scone bonnet, and the saunders-boot hose that I spoke to, but the

man that was in them; and the man, sir, for true worth, would

weigh down you and me, and ten more such, any day." There may

be a homeliness in externals, which may seem vulgar to those who

cannot discern the heart beneath; but, to the right-minded,

character will always have its clear insignia.

William and Charles Grant were the sons of a farmer in

Inverness-shire, whom a sudden flood stripped of everything, even to

the very soil which he tilled. The farmer and his sons, with

the world before them where to choose, made their way southward in

search of employment until they arrived in the neighbourhood of Bury

in Lancashire. From the crown of the hill near Walmesley they

surveyed the wide extent of country which lay before them, the river

Irwell making its circuitous course through the valley. They

were utter strangers in the neighbourhood, and knew not which way to

turn. To decide their course they put up a stick, and agreed

to pursue the direction in which it fell. Thus their decision was

made, and they journeyed on accordingly until they reached the

village of Ramsbotham, not far distant. They found employment

in a print-work, in which William served his apprenticeship; and

they commended themselves to their employers by their diligence,

sobriety, and strict integrity. They plodded on, rising from

one station to another, until at length the two men themselves

became employers, and after many long years of industry, enterprise,

and benevolence, they became rich, honoured, and respected by all

who knew them. Their cotton-mills and print-works gave

employment to a large population. Their well-directed

diligence made the valley teem with activity, joy, health, and

opulence. Out of their abundant wealth they gave liberally to

all worthy objects, erecting churches, founding schools and in all

ways promoting the well-being of the class of working-men from which

they had sprung. They afterwards erected, on the top of the

hill above Walmesley, a lofty tower in commemoration of the early

event in their history which had determined the place of their

settlement. The brothers Grant became widely celebrated for

their benevolence and their various goodness, and it is said that

Mr. Dickens had them in his mind's eye when delineating the

character of the brothers Cheeryble. One amongst many

anecdotes of a similar kind may be cited to show that the character

was by no means exaggerated. A Manchester warehouseman

published an exceedingly scurrilous pamphlet against the firm of

Grant Brothers, holding up the elder partner to ridicule as "Billy

Button." William was informed by some one of the nature of the

pamphlet, and his observation was that the man would live to repent

of it. "Oh!" said the libeller, when informed of the remark,

"he thinks that some time or other I shall be in his debt; but I

will take good care of that." It happens, however, that men in

business do not always foresee who shall be their creditor, and it

so turned out that the Grants' libeller became a bankrupt, and could

not complete his certificate and begin business again without

obtaining their signature. It seemed to him a hopeless case to

call upon that firm for any favour, but the pressing claims of his

family forced him to make the application. He appeared before

the man whom he had ridiculed as "Billy Button" accordingly.

He told his tale and produced his certificate. "You wrote a

pamphlet against us once?" said Mr. Grant. The supplicant

expected to see his document thrown into the fire; instead of which

Grant signed the name of the firm, and thus completed the necessary

certificate. "We make it a rule," said he, handing it back,

"never to refuse signing the certificate of an honest tradesman, and

we have never heard that you were anything else." The tears

started into the man's eyes. "Ah," continued Mr. Grant, "you

see my saying was true, that you would live to repent writing that

pamphlet. I did not mean it as a threat—I only meant that some