|

MEN OF INVENTION AND INDUSTRY.

CHAPTER I.

PHINEAS PETT:

BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH SHIP-BUILDING.

"A speck in the Northern Ocean, with a rocky coast,

an ungenial climate, and a soil scarcely fruitful,—this was the

material patrimony which descended to the English race—an

inheritance that would have been little worth but for the

inestimable moral gift that accompanied it. Yes; from Celts,

Saxons, Danes, Normans—from some or all of them—have come down with

English nationality a talisman that could command sunshine, and

plenty, and empire, and fame. The 'go' which they transmitted

to us—the national vis—this it is which made the old

Angle-land a glorious heritage. Of this we have had a

portion above our brethren—good measure, running over. Through

this our island-mother has stretched out her arms till they

enriched the globe of the earth. . . . Britain, without her energy

and enterprise, what would she be in Europe?"— Blackwood's

Edinburgh Magazine (1870).

IN one of the few

records of Sir Isaac Newton's life which he left for the benefit of

others, the following comprehensive thought occurs:

"It is certainly apparent that the inhabitants of this world

are of a short date, seeing that all arts, as letters, ships,

printing, the needle, &c., were discovered within the memory of

history."

If this were true in Newton's time, how much truer is it now.

Most of the inventions which are so greatly influencing, as well as

advancing, the civilization of the world at the present time, have

been discovered within the last hundred or hundred and fifty years.

We do not say that man has become so much wiser during that

period; for, though he has grown in Knowledge, the most fruitful of

all things were said by "the heirs of all the ages" thousands of

years ago.

But as regards Physical Science, the progress made during the

last hundred years has been very great. Its most recent

triumphs have been in connection with the discovery of electric

power and electric light. Perhaps the most important

invention, however, was that of the working steam engine, made by

Watt only about a hundred years ago. The most recent

application of this form of energy has been in the propulsion of

ships, which has already produced so great an effect upon commerce,

navigation, and the spread of population over the world.

Equally important has been the influence of the Railway—now

the principal means of communication in all civilized countries.

This invention has started into full life within our own time.

The locomotive engine had for some years been employed in the

haulage of coals; but it was not until the opening of the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway in 1830 that the importance of the invention

came to be acknowledged. The locomotive railway has since been

everywhere adopted throughout Europe. In America, Canada, and

the Colonies, it has opened up the boundless resources of the soil,

bringing the country nearer to the towns, and the towns to the

country. It has enhanced the celerity of time, and imparted a

new series of conditions to every rank of life.

The importance of steam navigation has been still more

recently ascertained. When it was first proposed, Sir Joseph

Banks, President of the Royal Society, said: "It is a pretty plan,

but there is just one point overlooked: that the steam-engine

requires a firm basis on which to work." Symington, the

practical mechanic, put this theory to the test by his successful

experiments, first on Dalswinton Lake, and then on the Forth and

Clyde Canal. Fulton and Bell afterwards showed the power of

steamboats in navigating the rivers of America and Britain.

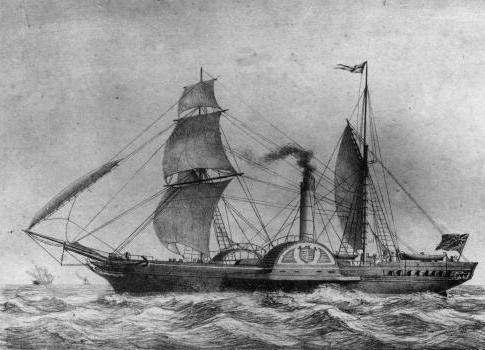

S.S. Sirius.

Picture Wikipedia.

After various experiments, it was proposed to unite England

and America by steam. Dr. Lardner, however, delivered a

lecture before the Royal Institution, in 1838, "proving" that

steamers could never cross the Atlantic, because they could not

carry sufficient coal to raise steam enough during the voyage.

But this theory was also tested by experience in the same year, when

the Sirius, of London, left Cork for New York, and made the

passage in nineteen days. Four days after the departure of the

Sirius, the Great Western left Bristol for New York,

and made the passage in thirteen days five hours. [p.3]

The problem was solved; and great ocean steamers have ever since

passed in continuous streams between the shores of England and

America.

In an age of progress, one invention merely paves the way for

another. The first steamers were impelled by means of paddle

wheels; but these are now almost entirely superseded by the screw.

And this, too, is an invention almost of yesterday. It was

only in 1840 that the Archimedes was fitted as a screw yacht.

A few years later, in 1845, the Great Britain, propelled by

the screw, left Liverpool for New York, and made the voyage in

fourteen days. The screw is now invariably adopted in all long

ocean voyages.

It is curious to look back, and observe the small beginnings

of maritime navigation. As regards this country, though its

institutions are old, modern England is still young. As

respects its mechanical and scientific achievements, it is the

youngest of all countries. Watt's steam engine was the

beginning of our manufacturing supremacy; and since its adoption,

inventions and discoveries in Art and Science, within the last

hundred years, have succeeded each other with extraordinary

rapidity. In 1814 there was only one steam vessel in Scotland;

while England possessed none at all. Now, the British

mercantile steam-ships number about 5,000, with about 4 millions of

aggregate tonnage. [p.4]

In olden times this country possessed the materials for great

things, as well as the men fitted to develop them into great

results. But the nation was slow to awake and take advantage

of its opportunities. There was no enterprise, no commerce—no

"go" in the people. The roads were frightfully bad; and there

was little communication between one part of the country and

another. If anything important had to be done, we used to send

for foreigners to come and teach us how to do it. We sent for

them to drain our fens, to build our piers and harbours, and even to

pump our water at London Bridge. Though a seafaring population

lived round our coasts, we did not fish our own seas, but left it to

the industrious Dutchmen to catch the fish, and supply our markets.

It was not until the year 1787 that the Yarmouth people began the

deep-sea herring fishery; and yet these were the most enterprising

amongst the English fishermen.

English commerce also had very slender beginnings. At the

commencement of the fifteenth century, England was of very little

account in the affairs of Europe. Indeed, the history of

modern England is nearly coincident with the accession of the Tudors

to the throne. With the exception of Calais and Dunkirk, her

dominions on the Continent had been wrested from her by the French.

The country at home had been made desolate by the Wars of the Roses.

The population was very small, and had been kept down by war,

pestilence, and famine. [p.5]

The chief staple was wool, which was exported to Flanders in foreign

ships, there to be manufactured into cloth. Nearly every

article of importance was brought from abroad; and the little

commerce which existed was in the hands of foreigners. The

seas were swept by privateers, little better than pirates, who

plundered without scruple every vessel, whether friend or foe, which

fell in their way.

The British navy has risen from very low beginnings.

The English fleet had fallen from its high estate since the reign of

Edward III., who won a battle from the French and Flemings in 1340,

with 260 ships; but his vessels were all of moderate size, being

boats, yachts, and caravels, of very small tonnage. According

to the contemporary chronicles, Weymouth, Fowey, Sandwich, and

Bristol, were then of nearly almost as much importance as London; [p.6-1]

which latter city only furnished twenty-five vessels, with 662

mariners.

The Royal Fleet began in the reign of Henry VII. Only

six or seven vessels then belonged to the King, the largest being

the Grace de Dieu, of comparatively small tonnage. The

custom then was, to hire ships from the Venetians, the Genoese, the

Hanse towns, and other trading people; and as soon as the service

for which the vessels so hired was performed, they were dismissed.

When Henry VIII. ascended the throne in 1509, he directed his

attention to the state of the navy. Although the insular

position of England was calculated to stimulate the art of

shipbuilding more than in most continental countries, our best ships

long continued to be built by foreigners. Henry invited from

abroad, especially from Italy, where the art of shipbuilding had

made the greatest progress, as many skilful artists and workmen as

he could procure, either by the hope of gain, or the high honours

and distinguished countenance which he paid them. "By

incorporating" says Charnock, "these useful persons among his own

subjects, he soon formed a corps sufficient to rival those states

which had rendered themselves most distinguished by their knowledge

in this art; so that the fame of Genoa and Venice, which had long

excited the envy of the greater part of Europe, became suddenly

transferred to the shores of Britain." [p.6-2]

In fitting out his fleet, we find Henry disbursing large sums

to foreigners for shipbuilding, for "harness" or armour, and for

munitions of all sorts. The State Papers [p.7]

particularize the amounts paid to Lewez do la Fava for "harness;" to

William Gurre, "bragandy-maker;" to Leonard Friscobald for "almayn

ryvetts." Francis de Errona, a Spaniard, supplied the

gunpowder. Among the foreign mechanics and artizans employed

were Hans Popenruyter, gunfounder of Mechlin; Robert Sakfeld, Robert

Skorer, Fortune, de Catalenago, and John Cavelcant. On one

occasion £2,797 19s. 4½d. was disbursed for guns and grindstones.

This sum must be multiplied by about four, to give the proper

present value. Popenruyter seems to have been the great

gunfounder of the age; he supplied the principal guns and gun stores

for the English navy, and his name occurs in every Ordnance account

of the series, generally for sums of the largest amounts.

Henry VIII. was the first to establish Royal dock-yards,

first at Woolwich, then at Portsmouth, and thirdly at Deptford, for

the erection and repair of ships. Before then, England had

been principally dependent upon Dutchmen and Venetians, both for

ships of war and merchantmen. The sovereign had neither naval

arsenals nor dockyards, nor any regular establishment of civil or

naval affairs to provide ships of war. Sir Edward Howard, Lord

High Admiral of England, at the accession of Henry VIII., actually

entered into a "contract" with that monarch to fight his enemies.

This singular document is still preserved in the State Paper office.

Even after the establishment of royal dockyards, the sovereign—as

late as the reign of Elizabeth—entered into formal contracts with

shipwrights for the repair and maintenance of ships, as well as for

additions to the fleet.

The King, having made his first effort at establishing a

royal navy, sent the fleet to sea against the ships of France.

The Regent was the ship royal, with Sir Thomas Knivet, Master

of the Horse, and Sir John Crew of Devonshire, as Captains.

The fleet amounted to twenty-five well furnished ships. The

French fleet were thirty-nine in number. They met in Brittany

Bay, and had a fierce fight. The Regent grappled with a

great carack of Brest; the French, on the English boarding their

ship, set fire to the gunpowder, and both ships were blown up, with

all their men. The French fleet fled, and the English kept the

seas. The King, hearing of the loss of the Regent,

caused a great ship to be built, the like of which had never before

been seen in England, and called it Harry Grace de Dieu.

This ship was constructed by foreign artizans, principally by

Italians, and was launched in 1515. She was said to be of a

thousand tons portage—the largest ship in England. The vessel

was four-masted, with two round tops on each mast, except the

shortest wizen. She had a high forecastle and poop, from which

the crew could shoot down upon the deck or waist of another vessel.

The object was to have a sort of castle at each end of the ship.

This style of shipbuilding was doubtless borrowed from the

Venetians, then the greatest naval power in Europe. The length

of the masts, the height of the ship above the water's edge, and the

ornaments and decorations, were better adapted for the stillness of

the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas, than for the boisterous ocean

of the northern parts of Europe. [p.9-1]

The story long prevailed that "the Great Harry swept a dozen flocks

of sheep off the Isle of Man with her bob-stay." An American

gentleman (N. B. Anderson, LL.D., Boston) informed the present

author that this saying is still proverbial amongst the United

States sailors.

The same features were reproduced in merchant ships.

Most of them were suited for defence, to prevent the attacks of

pirates, which swarmed the seas round the coast at that time.

Shipbuilding by the natives in private shipyards was in a miserable

condition. Mr. Willet, in his memoir relative to the navy,

observes: "It is said, and I believe with truth, that at this time

(the middle of the sixteenth century) there was not a private

builder between London Bridge and Gravesend, who could lay down a

ship in the mould left from a Navy Board's draught, without applying

to a tinker who lived in Knave's Acre." [p.9-2]

Mary Rose.

Picture Wikipedia.

Another ship of some note built at the instance of Henry

VIII. was the Mary Rose, of the portage of 500 tons. We

find her in the "pond at Deptford" in 1515. Seven years later,

in the thirtieth year of Henry VIII.'s reign, she was sent to sea,

with five other English ships of war, to protect such commerce as

then existed from the depredations of the French and Scotch pirates.

The Mary Rose was sent many years later (in 1544) with the

English fleet to the coast of France, but returned with the rest of

the fleet to Portsmouth without entering into any engagement.

While laid at anchor, not far from the place where the Royal

George afterwards went down, and the ship was under repair, her

gun-ports being very low when she was laid over, "the shipp turned,

the water entered, and sodainly she sanke."

What was to be done? There were no English engineers or

workmen who could raise the ship. Accordingly, Henry VIII.

sent to Venice for assistance, and when the men arrived, Pietro de

Andreas was dispatched with the Venetian marines and carpenters to

raise the Mary Rose. Sixty English mariners were

appointed to attend upon them. The Venetians were then the

skilled "heads," the English were only the "hands."

Nevertheless they failed with all their efforts; and it was not

until the year 1836 that Mr. Dean, the engineer, succeeded in

raising not only the Royal George, but the Mary Rose,

and cleared the roadstead at Portsmouth of the remains of the sunken

ships.

When Elizabeth ascended the throne in 1558, the commerce and

navigation of England were still of very small amount. The

population of the kingdom amounted to only about five millions—not

much more than the population of London is now. The country

had little commerce, and what it had was still mostly in the hands

of foreigners. The Hanse towns had their large entrepôt

for merchandise in Cannon Street, on the site of the present Cannon

Street Station. The wool was still sent abroad to Flanders to

be fashioned into cloth, and even garden produce was principally

imported from Holland. Dutch, Germans, Flemings, French, and

Venetians continued to be our principal workmen. Our iron was

mostly obtained from Spain and Germany. The best arms and

armour came from France and Italy. Linen was imported from

Flanders and Holland, though the best came from Rheims. Even

the coarsest dowlas, or sailcloth, was imported from the Low

Countries.

The royal ships continued to be of very small burthen, and

the mercantile ships were still smaller. The Queen, however,

did what she could to improve the number and burthen of our ships.

"Foreigners," says Camden, "stiled her the restorer of naval glory

and Queen of the Northern Seas." In imitation of the Queen,

opulent subjects built ships of force; and in course of time England

no longer depended upon Hamburg, Dantzic, Genoa, and Venice, for her

fleet in time of war.

Spain was then the most potent power in Europe, and the

Netherlands, which formed part of the dominions of Spain, was the

centre of commercial prosperity. Holland possessed above 800

good ships, of from 200 to 700 tons burthen, and above 600 busses

for fishing, of from 100 to 200 tons. Amsterdam and Antwerp

were in the heyday of their prosperity. Sometimes 500 great ships

were to be seen lying together before Amsterdam; [p.11]

whereas England at that time had not four merchant ships of 400 tons

each! Antwerp, however, was the most important city in the Low

Countries. It was no uncommon thing to see as many as 2,500

ships in the Scheldt, laden with merchandize. Sometimes 500

ships would come and go from Antwerp in one day, bound to or

returning from the distant parts of the world. The place was

immensely rich, and was frequented by Spaniards, Germans, Danes,

English, Italians, and Portuguese—the Spaniards being the most

numerous. Camden, in his history of Queen Elizabeth, relates

that our general trade with the Netherlands in 1564 amounted to

twelve millions of ducats, five millions of which was for English

cloth alone.

The religious persecutions of Philip II. of Spain and of

Charles IX. of France shortly supplied England with the population

of which she stood in need—active, industrious, intelligent

artizans. Philip set up the Inquisition in Flanders, and in a

few years more than 50,000 persons were deliberately murdered.

The Duchess of Parma, writing to Philip II. in 1567, informed him

that in a few days above 100,000 men had already left the country

with their money and goods, and that more were following every day.

They fled to Germany, to Holland, and above all to England, which

they hailed as Asylum Christi. The emigrants settled in

the decayed cities and towns of Canterbury, Norwich, Sandwich,

Colchester, Maidstone, Southampton, and many other places, where

they carried on their manufactures of woollen, linen, and silk, and

established many new branches of industry. [p.12]

Five years later, in 1572, the Massacre of St. Bartholomew

took place in France, during which the Roman Catholic Bishop

Péréfixe alleges that 100,000 persons were put to death because of

their religious opinions. All this persecution, carried on so

near the English shores, rapidly increased the number of foreign

fugitives into England, which was followed by the rapid advancement

of the industrial arts in this Country.

The asylum which Queen Elizabeth gave to the persecuted

foreigners brought down upon her the hatred of Philip II. and

Charles IX. When they found that they could not prevent her

furnishing them with an asylum, they proceeded to compass her death.

She was excommunicated by the Pope, and Vitelli was hired to

assassinate her. Philip also proceeded to prepare the Sacred

Armada for the subjugation of the English nation, and he was master

of the most powerful army and navy in the world.

Modern England was then in the throes of her birth. She

had not yet reached the vigour of her youth, though she was full of

life and energy. She was about to become the England of free

thought, commerce, and manufactures; to plough the ocean with her

navies, and to plant her colonies over the earth. Up to the

accession of Elizabeth, she had done little, but now she was about

to do much. It was a period of sudden emancipation of thought,

and of immense fertility and originality. The poets and prose

writers of the time united the freshness of youth with the vigour of

manhood. Among these were Spenser, Shakespeare, Sir Philip

Sidney, the Fletchers, Marlowe, and Ben Jonson. Among the

statesmen of Elizabeth were Burleigh, Leicester, Walsingham, Howard,

and Sir Nicholas Bacon. But perhaps greatest of all were the

sailors, who, as Clarendon said, "were a nation by themselves;" and

their leaders—Drake, Frobisher, Cavendish, Hawkins, Howard, Raleigh,

Davis, and many more distinguished seamen.

They were the representative men of their time, the creation

in a great measure of the national spirit. They were the

offspring of long generations of seamen and lovers of the sea.

They could not have been great but for the nation which gave them

birth, and imbued them with their worth and spirit. The great

sailors, for instance, could not have originated in a nation of mere

landsmen. They simply took the lead in a country whose coasts

were fringed with sailors. Their greatness was but the result

of an excellence in seamanship which prevailed widely around them.

The age of English maritime adventure only began in the reign

of Elizabeth. England had then no colonies—no foreign

possessions whatever. The first of her extensive colonial

possessions was established in this reign. "Ships, colonies,

and commerce" began to be the national motto—not that colonies make

ships and commerce, but that ships and commerce make colonies.

Yet what cockle-shells of ships our pioneer navigators first sailed

in!

Although John Cabot or Gabota, of Bristol, originally a

citizen of Venice, had discovered the continent of North America in

1496, in the reign of Henry VII., he made no settlement there, but

returned to Bristol with his four small ships. Columbus did

not see the continent of America until two years later, in 1498, his

first discoveries being the islands of the West Indies.

It was not until the year 1553 that an attempt was made to

discover a North-west passage to Cathaya or China. Sir Hugh

Willoughby was put in command of the expedition, which consisted of

three ships,—the Bona Esperanza, the Bona Ventura

(Captain Chancellor), and the Bona Confulentia (Captain

Durforth),—most probably ships built by Venetians. Sir Hugh

reached 72 degrees of north latitude, and was compelled by the

buffeting of the winds to take refuge with Captain Durforth's vessel

at Arcing Keca, in Russian Lapland, where the two captains and the

crews of these ships, seventy in number, were frozen to death.

In the following year some Russian fishermen found Sir John

Willoughby sitting dead in his cabin, with his diary and other

papers beside him.

Captain Chancellor was more fortunate. He reached

Archangel in the White Sea, where no ship had ever been seen before.

He pointed out to the English the way to the whale fishery at

Spitzbergen, and opened up a trade with the northern parts of

Russia. Two years later, in 1556, Stephen Burroughs sailed

with one small ship, which entered the Kara Sea; but he was

compelled by frost and ice to return to England. The strait

which he entered is still called "Burrough Strait."

It was not, however, until the reign of Elizabeth that great

maritime adventures began to be made. Navigators were not so

venturous as they afterwards became. Without proper methods of

navigation, they were apt to be carried away to the south, across an

ocean without limit. In 1565 a young captain, Martin

Frobisher, came into notice. At the age of twenty-five he

captured in the South Seas the Flying Spirit, a Spanish ship

laden with a rich cargo of cochineal. Four years later, in

1569, he made his first attempt to discover the north-west passage

to the Indies, being assisted by Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick.

The ships of Frobisher were three in number, the Gabriel, of

from 15 to 20 tons; the Michael, of from 20 to 25 tons, or

half the size of a modern fishing boat; and a pinnace, of from 7 to

10 tons! The aggregate of the crews of the three ships was

only thirty-five, men and boys. Think of the daring of these

early navigators in attempting to pass by the North Pole to Cathay

through snow, and storm, and ice, in such miserable little

cockboats! The pinnace was lost; the Michael, under

Owen Griffith, a Welshman, deserted; and Martin Frobisher in the

Gabriel went alone into the north-western sea!

He entered the great bay, since called Hudson's Bay, by

Frobisher's Strait. He returned to England without making the

discovery of the Passage, which with long remained the problem of

arctic voyagers. Yet ten long years later, in 1577, he made

another voyage, and though he made his second attempt with one of

Queen Elizabeth's own ships, and two barks, with 140 persons in all,

he was as unsuccessful as before. He brought home some

supposed gold ore; and on the strength of the stones containing

gold, a third expedition went out in the following year. After

losing one of the ships, consuming the provisions, and suffering

greatly from ice and storms, the fleet returned home one by one.

The supposed gold ore proved to be only glittering sand.

Francis Drake (1540-96): statue at Plymouth.

Photograph: Wikipedia.

While Frobisher was seeking El-Dorado in the North, Francis

Drake was finding it in the South. He was a sailor, every inch

of him. "Pains, with patience in his youth," says Fuller,

"knit the joints of his soul, and made them more solid and compact."

At an early age, when carrying on a coasting trade, his imagination

was inflamed by the exploits of his protector Hawkins in the New

World, and he joined him in his last unfortunate adventure on the

Spanish Main. He was not, however, discouraged by his first

misfortune, but having assembled about him a number of seamen who

believed in him, he made other adventures to the West Indies, and

learnt the navigation of that part of the ocean. In 1570, he

obtained a regular commission from Queen Elizabeth, though he sailed

his own ships, and made his own ventures. Every Englishman,

who had the means, was at liberty to fit out his own ships; and with

tolerable vouchers, he was able to procure a commission from the

Court, and proceed to sea at his own risk and cost. Thus, the

naval enterprise and pioneering of new countries under Elizabeth,

was almost altogether a matter of private enterprise and adventure.

In 1572, the butchery of the Huguenots took place at Paris

and throughout France; while at the same time the murderous power of

Philip II. reigned supreme in the Netherlands. The sailors

knew what they had to expect from the Spanish king in the event of

his obtaining his threatened revenge upon England; and under their

chosen chiefs they proceeded to make war upon him. In the year

of the massacre of St. Bartholomew, Drake set sail for the Spanish

Main in the Pasha, of seventy tons, accompanied by the

Swan, of twenty-five tons; the united crews of the vessels

amounting to seventy-three men and boys. With this

insignificant force, Drake made great havoc amongst the Spanish

shipping at Nombre de Dios. He partially crossed the Isthmus

of Darien, and obtained his first sight of the great Pacific Ocean.

He returned to England in August 1573, with his frail barks crammed

with treasure.

A few years later, in 1577, he made his ever-memorable

expedition. Charnock says it was "an attempt in its nature so

bold and unprecedented, that we should scarcely know whether to

applaud it as a brave, or condemn it as a rash one, but for its

success." The squadron with which he sailed for South America

consisted of five vessels, the largest of which, the Pelican,

was only of 100 tons burthen; the next, the Elizabeth, was of

80; the third, the Swan, a fly-boat, was of 50; the

Marygold bark, of 30; and the Christopher, a pinnace, of

15 tons. The united crews of these vessels amounted to only

164, gentlemen and sailors.

The gentlemen went with Drake "to learn the art of

navigation." After various adventures along the South American

coast, the little fleet passed through the Straits of Magellan, and

entered the Pacific Ocean. Drake took an immense amount of booty

from the Spanish towns along the coast, and captured the royal

galleon, the Cacafuego, laden with treasure. After

trying in vain to discover a passage home by the North-eastern

ocean, though what is now known as Behring Straits, he took shelter

in Port San Francisco, which he took possession of in the name of

the Queen of England, and called New Albion. He eventually

crossed the Pacific for the Moluccas and Java, from which he sailed

right across the Indian Ocean, and by the Cape of Good Hope to

England, thus making the circumnavigation of the world. He was

absent with his little fleet for about two years and ten months.

Not less extraordinary was the voyage of Captain Cavendish,

who made the circumnavigation of the globe at his own expense.

He set out from Plymouth in three small vessels on the 21st July,

1586. One vessel was of 120 tons, the second of 60 tons, and

the third of 40 tons—not much bigger than a Thames yacht. The

united crews, of officers, men, and boys, did not exceed 123!

Cavendish sailed along the South American continent, and made

through the Straits of Magellan, reaching the Pacific Ocean.

He burnt and plundered the Spanish settlements along the coast,

captured some Spanish ships, and took by boarding the galleon St.

Anna, with 122,000 Spanish dollars on board. He then

sailed across the Pacific to the Ladrone Islands, and returned home

through the Straits of Java and the Indian Archipelago by the Cape

of Good Hope, and reached England after an absence of two years and

a month.

The sacred and invincible Armada was now ready. Phillip II.

was determined to put down those English adventurers who had swept

the coasts of Spain and plundered his galleons on the high seas.

The English sailors knew that the sword of Philip was forged in the

gold mines of South America, and that the only way to defend their

country was to intercept the plunder on its voyage home to Spain.

But the sailors and their captains— Drake, Hawkins, Frobisher,

Howard, Grenville, Raleigh, and the rest—could not altogether

interrupt the enterprise of the King of Spain. The Armada

sailed, and came in sight of the English coast on the 20th of July,

1588.

An English warship of the Armada period: a replica of

the Golden Hind

now berthed as a floating museum in St.Mary Overie Dock, near to

Southwark Cathedral.

© Copyright

Martin Addison and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

The struggle was of an extraordinary character. On the

one side was the most powerful naval armament that had ever put to

sea. It consisted of six squadrons of sixty fine large ships,

the smallest being of 700 tons. Besides these were four

gigantic galleasses, each carrying fifty guns, four large armed

galleys, fifty-six armed merchant ships, and twenty caravels—in all,

149 vessels. On board were 8,000 sailors, 20,000 soldiers, and

a large number of galley-slaves. The ships carried provisions

enough for six months' consumption; and the supply of ammunition was

enormous.

On the other side was the small English fleet under Hawkins

and Drake. The Royal ships were only thirteen in number.

The rest were contributed by Private enterprise, there being only

thirty-eight vessels of all sorts and sizes, including cutters and

pinnaces, carrying the Queen's flag. The principal armed

merchant ships were provided by London, Southampton, Bristol, and

the other southern ports. Drake was followed by some

privateers; Hawkins had four or five ships, and Howard of Effingham

two. The fleet was, however, very badly found in provisions

and ammunition. There was only a week's provisions on board,

and scarcely enough ammunition for one day's hard fighting.

But the ships, small though they were, were in good condition.

They could sail, whether in pursuit or in flight, for the men who

navigated them were thorough sailors.

The success of the defence was due to tact, courage, and

seamanship. At the first contact of the fleets, the Spanish

towering galleons wished to close, to grapple with their

contemptuous enemies, and crush them to death. "Come on!" said

Medina Sidonia. Lord Howard came on with the Ark and

three other ships, and fired with immense rapidity into the great

floating castles. The San Mateo luffed, and wanted them

to board. "No! not yet!" The English tacked, returned,

fired again, riddled the Spaniards, and shot away in the eye of the

wind. To the astonishment of the Spanish Admiral, the English

ships approached him or left him just as they chose. "The

enemy pursue me," wrote the Spanish Admiral to the Prince of Parma;

"they fire upon me most days from morning till nightfall, but they

will not close and grapple, though I have given them every

opportunity." The Capitana, a galleon of 1,200 tons,

dropped behind, struck her flag to Drake, and increased the store of

the English fleet by some tons of gunpowder. Another Spanish

ship surrendered, and another store of powder and shot was rescued

for the destruction of the Armada. And so it happened

throughout, until the Spanish fleet was driven to wreck and ruin,

and the remaining ships were scattered by the tempests of the north.

After all, Philip proved to be, what the sailors called him, only "a

Colossus stuffed with clouts."

The English sailors followed up their advantage. They

went on "singeing the King of Spain's beard." Private

adventurers fitted up a fleet under the command of Drake, and

invaded the mainland of Spain. They took the lower part of the

town of Corunna; sailed to the Tagus, and captured a fleet of ships

laden with wheat and warlike stores for a new Armada. They

next sacked Vigo, and returned to England with 150 pieces of cannon

and a rich booty. The Earl of Cumberland sailed to the West

Indies on a private adventure, and captured more Spanish prizes.

In 1590, ten English merchantmen, returning from the Levant,

attacked twelve Spanish galleons, and after six hours' contest, put

them to flight with great loss. In the following year, three

merchant ships set sail for the East Indies, and in the course of

their voyage took several Portuguese vessels.

A powerful Spanish fleet still kept the seas, and in 1591

they conquered the noble Sir Richard Grenville at the Azores—fifteen

great Spanish galleons against one Queen's ship, the Revenge.

In 1593, two of the Queen's ships, accompanied by a number of

merchant ships, sailed for the West Indies, under Burroughs,

Frobisher, and Cross, and amongst their other captures they took the

greatest of all the East India caracks, a vessel of 1,600 tons, 700

men, and 36 brass cannon, laden with a magnificent cargo. She

was taken to Dartmouth, and surprised all who saw her, being the

largest ship that had ever been seen in England. In 1594,

Captain James Lancaster set sail with three ships upon a voyage of

adventure. He was joined by some Dutch and French privateers.

The result was, that they captured thirty-nine of the Spanish ships.

Sir Amias Preston, Sir John Hawkins, and Sir Francis Drake, also

continued their action upon the seas. Lord Admiral Howard and

the Earl of Essex made their famous attack upon Cadiz for the

purpose of destroying the new Armada; they demolished all the forts;

sank eleven of the King of Spain's best ships, forty-four merchant

ships, and brought home much booty.

Nor was maritime discovery neglected. The planting of

new colonies began, for the English people had already begun to

swarm. In 1578, Sir Humphrey Gilbert planted Newfoundland for

the Queen. In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh planted the first

settlement in Virginia. Nor was the North-west passage

neglected; for in 1580, Captain Pett (a name famous on the Thames)

set sail from Harwich in the George, accompanied by Captain

Jackman in the William. They reached the ice in the

North Sea, but were compelled to return without effecting their

purpose. Will it be believed that the George was only

of 40 tons, and that its crew consisted of nine men and a boy; and

that the William was of 20 tons, with five men and a boy?

The wonder is that these little vessels should resist the terrible

icefields, and return to England again with their hardy crews.

Then in 1585, another of our adventurous sailors, John Davis,

of Sandridge on the Dart, set sail with two barks, the Sunshine

and the Moonshine, of 50 and 35 tons respectively, and

discovered in the far North-west the Strait which now bears his

name. He was driven back by the ice; but, undeterred by his

failure, he set out on a second, and then on a third voyage of

discovery in the two following years. But he never succeeded

in discovering the North-west passage. It all reads like a

mystery—these repeated, determined, and energetic attempts to

discover a new way of reaching the fabled region of Cathay.

In these early times the Dutch were not unworthy rivals of

the English. After they had succeeded in throwing off the

Spanish yoke and achieved their independence, they became one of the

most formidable of maritime powers. In the course of another

century Holland possessed more colonies, and had a larger share of

the carrying trade of the world than Britain. It was natural

therefore that the Dutch republic should take an interest in the

North-west passage; and the Dutch sailors, by their enterprise and

bravery, were among the first to point the way to Arctic discovery.

Barents and Behring, above all others, proved the courage and

determination of their heroic ancestors.

The romance of the East India Company begins with an

advertisement in the London Gazette of 1599, towards the end

of the reign of Queen Elizabeth. As with all other enterprises

of the nation, it was established by private means. The

Company was started with a capital of £72,000 in £50 shares.

The adventurers bought four vessels of an average burthen of 350

tons. These were stocked with provisions, "Norwich stuffs,"

and other merchandise. The tiny fleet sailed from Billingsgate

on the 13th February, 1601. It went by the Cape of Good Hope

to the East Indies, under the command of Captain James Lancaster.

It took no less than sixteen months to reach the Indian Archipelago.

The little fleet reached Acheen in June, 1602. The king of the

territory received the visitors with courtesy, and exchanged spices

with them freely. The four vessels sailed homeward, taking

possession of the island of St. Helena on their way back; having

been absent exactly thirty-one months. The profits of the

first voyage proved to be about one hundred per cent. Such was

the origin of the great East India Company—now expanded into an

empire, and containing about two hundred millions of people.

To return to the shipping and the mercantile marine of the

time of Queen Elizabeth. The number of Royal ships was only

thirteen, the rest of the navy consisting of merchant ships, which

were hired and discharged when their purpose was served. [p.24-1]

According to Wheeler, at the accession of the Queen, there were not

more than four ships belonging to the river Thames, excepting those

of the Royal Navy, which were over 120 tons in burthen; [p.24-2]

and after forty years, the whole of the merchant ships of England,

over 100 tons, amounted to 135; only a few of these being of 500

tons. In 1588, the number had increased to 150, "of about 150

tons one with another, employed in trading voyages to all parts and

countries." The principal shipping which frequented the

English ports still continued to be foreign—Italian, Flemish, and

German.

Liverpool, now possessing the largest shipping tonnage in the

world, had not yet come into existence. It was little better

than a fishing village. The people of the place presented a

petition to the Queen, praying her to remit a subsidy which had been

imposed upon them, and speaking of their native place as "Her

Majesty's poor decayed town of Liverpool." In 1565, seven

years after Queen Elizabeth began to reign, the number of vessels

belonging to Liverpool was only twelve. The largest was of

forty tons burthen, with twelve men; and the smallest was a boat of

six tons, with three men. [p.24-3]

James I., on his accession to the throne of England in 1603,

called in all the ships of war, as well as the numerous privateers

which had been employed during the previous reign in waging war

against the commerce of Spain, and declared himself to be at peace

with all the world. James was as peaceful as a Quaker.

He was not a fighting king; and, partly on this account, he was not

popular. He encouraged manufactures in wool, silk, and

tapestry. He gave every encouragement to the mercantile and

colonizing adventurers to plant and improve the rising settlements

of Virginia, New England, and Newfoundland. He also promoted

the trade to the East Indies. Attempts continued to be made,

by Hudson, Poole, Button, Hall, Baffin, and other courageous seamen,

to discover the North-West passage, but always without effect.

The shores of England being still much infested by Algerine

and other pirates, [p.25] King

James found it necessary to maintain the ships of war in order to

protect navigation and commerce. He nearly doubled the ships

of the Royal Navy, and increased the number from thirteen to

twenty-four. Their size, however, continued small, both Royal

and merchant ships. Sir William Monson says, that at the

accession of James I. there were not above four merchant ships in

England of 400 tons burthen. [p.26-1]

The East Indian merchants were the first to increase the size.

In 1609, encouraged by their Charter, they built the Trade's

Increase, of 1,100 tons burthen, the largest merchant ship that

had ever been built in England. As it was necessary that the

crew of the ship should be able to beat off the pirates, she was

fully armed. The additional ships of war were also of heavier

burthen. In the same year, the Prince, of 1,400 tons

burthen, was launched; she carried sixty-four cannon, and was

superior to any ship of the kind hitherto seen in England.

And now we arrive at the subject of this memoir. The Petts were the

principal ship-builders of the time. They had long been known upon

the Thames, and had held posts in the Royal Dockyards since the

reign of Henry VII. They were gallant sailors, too; one of them, as

already mentioned, having made an adventurous voyage to the Arctic

Ocean in his little bark, the George, of only 40 tons burthen. Phineas Pett was the first of the great ship-builders. His father,

Peter Pett, was one of the Queen's master shipwrights. Besides being

a ship-builder, he was also a poet, being the author of a poetical

piece entitled, "Time's Journey to seek his daughter Truth," [p.26-2]

a very respectable performance. Indeed, poetry is by no means

incompatible with ship-building—the late Chief Constructor of the

Navy being, perhaps, as proud of his poetry as of his ships. Pett's

poem was dedicated to the Lord High Admiral, Howard, Earl of

Nottingham; and this may possibly have been the reason of the

singular interest which he afterwards took in Phineas Pett, the poet

shipwright's son.

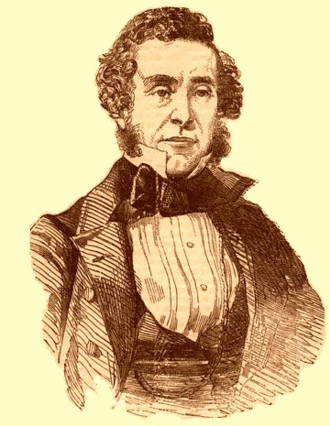

Phineas Pett (1570-1647): shipwright.

© National Portrait

Gallery, London.

Phineas Pett was the second son of his father. He was born at

Deptford, or "Deptford Strond," as the place used to be called, on

the 1st of November, 1570. At nine years old, he was sent to the

free-school at Rochester, and remained there for four years. Not

profiting much by his education there, his father removed him to a

private school at Greenwich, kept by a Mr. Adams. Here he made so

much progress, that in three years time he was ready for Cambridge. He was accordingly sent to that University at Shrovetide, 1586, and

was entered at Emmanuel College, under charge of Mr. Charles

Chadwick, the president. His father allowed him £20 per annum,

besides books, apparel, and other necessaries.

Phineas remained at Cambridge for three years. He was obliged to

quit the University by the death of his "reverend, ever-loving

father," whose loss, he says, "proved afterwards my utter undoing

almost, had not God been more merciful to me." His mother married

again, "a most wicked husband," says Pett in his autobiography, [p.27]

"one, Mr. Thomas Nunn, a minister," but of what denomination he does

not state. His mother's imprudence wholly deprived him of his

maintenance, and having no hopes of preferment from his friends, he

necessarily abandoned his University career, "presently after

Christmas, 1590."

Early in the following year, he was persuaded by his mother to

apprentice himself to Mr. Richard Chapman, of Deptford Stroud, one

of the Queen's Master shipwrights, whom his late father had "bred

up from a child to that profession." He was allowed £2 6s. 8d. per

annum, with which he had to provide himself with tools and apparel. Pett spent two years in this man's service to very little purpose;

Chapman then died, and the apprentice was dismissed. Pett applied to

his elder brother Joseph, who would not help him, although he had

succeeded to his father's post in the Royal Dockyard. He was

accordingly "constrained to ship himself to sea upon a desperate

voyage in a man-of-war." He accepted the humble place of carpenter's

mate on board the galleon Constance, of London. Pett's younger

brother, Peter, then living at Wapping, gave him lodging, meat, and

drink, until the ship was ready to sail. But he had no money to buy

clothes. Fortunately one William King, a yoeman in Essex, taking

pity upon the unfortunate young man, lent him £3 for that purpose;

which Pett afterwards repaid.

The Constance was of only 200 tons burden. She set sail for the

South a few days before Christmas, 1592. There is no doubt that she

was bound upon a piratical adventure. Piracy was not thought

dishonourable in those days. Four years had elapsed since the Armada

had approached the English coast; and now the English and Dutch

ships were scouring the seas in search of Spanish galleons. Whoever

had the means of furnishing a ship, and could find a plucky captain

to command her, sent her out as a privateer. Even the Companies of

the City of London clubbed their means together for the purpose of

sending out Sir Walter Raleigh to capture Spanish ships, and

afterwards to divide the plunder; as any one may see on referring to

the documents of the London Corporation. [p.29]

The adventure in which Pett was concerned did not prove very

fortunate. He was absent for about twenty months on the coasts of

Spain and Barbary, and in the Levant, enduring much misery for want

of victuals and apparel, and "without taking any purchase of any

value." The Constance returned to the Irish coast, "extreme poorly."

The vessel entered Cork harbour, and then Pett, thoroughly disgusted

with privateering life, took leave of both ship and voyage. With

much difficulty, he made his way across the country to Waterford,

from whence he took ship for London. He arrived there three days

before Christmas, 1594, in a beggarly condition, and made his way to

his brother Peter's house at Wapping, who again kindly entertained

him. The elder brother Joseph received him more coldly, though he

lent him forty shillings to find himself in clothes. At that time,

the fleet was ordered to be got ready for the last expedition of

Drake and Hawkins to the West Indies. The Defiance was sent into

Woolwich dock to be sheathed; and as Joseph Pett was in charge of

the job, he allowed his brother to be employed as a carpenter.

In the following year, Phineas succeeded in attracting the notice of

Matthew Baker, who was commissioned to rebuild Her Majesty's

Triumph. Baker employed Pett as an ordinary workman; but he had

scarcely begun the job before Baker was ordered to proceed with the

building of a great new ship at Deptford, called the Repulse. Phineas wished to follow the progress of the

Triumph, but finding

his brother Joseph unwilling to retain him in his employment, he

followed Baker to Deptford, and continued to work at the Repulse

until she was finished, launched, and set sail on her voyage, at the

end of April, 1596. This was the leading ship of the squadron which

set sail for Cadiz, under the command of the Earl of Essex and the

Lord Admiral Howard, and which did so much damage to the forts and

shipping of Philip II. of Spain.

During the winter months, while the work was in progress, Pett spent

the leisure of his evenings in perfecting himself in learning,

especially in drawing, cyphering, and mathematics, for the purpose,

as he says, of attaining the knowledge of his profession. His

master, Mr. Baker, gave him every encouragement, and from his

assistance, he adds, "I must acknowledge I received my greatest

lights." The Lord Admiral was often present at Baker's house. Pett

was importuned to set sail with the ship when finished, but he

preferred remaining at home. The principal reason, no doubt, that

restrained him at this moment from seeking the patronage of the

great, was the care of his two sisters, [p.31]

who, having fled from the house of their barbarous stepfather, could

find no refuge but in that of their brother Phineas. Joseph refused

to receive them, and Peter of Wapping was perhaps less able than

willing to do so.

In April, 1597, Pett had the advantage of being introduced to

Howard, Earl of Nottingham, then Lord High Admiral of England. This,

he says, was the first beginning of his rising. Two years later,

Howard recommended him for employment in purveying plank and timber

in Norfolk and Suffolk for shipbuilding purposes. Pett accomplished

his business satisfactorily, though he had some malicious enemies to

contend against. In his leisure, he began to prepare models of

ships, which he rigged and finished complete. He also proceeded with

the study of mathematics. The beginning of the year 1600 found Pett

once more out of employment; and during his enforced idleness,

which continued for six months, he seriously contemplated abandoning

his profession and attempting to gain "an honest and convenient

maintenance" by joining a friend in purchasing a caravel (a small

vessel), and navigating it himself.

He was, however, prevented from undertaking this enterprise by a

message which he received from the Court, then stationed at

Greenwich. The Lord High Admiral desired to see him; and after many

civil compliments, he offered him the post of keeper of the plankyard at Chatham. Pett was only too glad to accept this offer,

though the salary was small. He shipped his furniture on board a hoy

of Rainham, and accompanied it down the Thames to the junction with

the Medway. There he escaped a great danger—one of the sea perils of

the time. The mouths of navigable rivers were still infested with

pirates; and as the hoy containing Pett approached the Nore about

three o'clock in the morning, and while still dark, she came upon a

Dunkirk picaroon, full of men. Fortunately the pirate was at anchor;

she weighed and gave chase, and had not the hoy set full sail, and

been impelled up the Swale by a fresh wind, Pett would have been

taken prisoner, with all his furniture. [p.32]

Arrived at Chatham, Pett met his brother Joseph, became reconciled

to him, and ever after they lived together as loving brethren. At

his brother's suggestion, Pett took a lease of the Manor House, and

settled there with his sisters. He was now in the direct way to

preferment. Early in the following year (March, 1601) he succeeded

to the place of assistant to the principal master shipwright at

Chatham, and undertook the repairs of Her Majesty's ship The Lion's

Whelp, and in the next year he new-built the Moon, enlarging her

both in length and breadth.

At the accession of James I. in 1603, Pett was commanded by the Lord

High Admiral with all possible speed to build a little vessel for

the young Prince Henry, eldest son of His Majesty. It was to be a

sort of copy of the Ark Royal, which was the flagship of the Lord

High Admiral when he defeated the Spanish Armada. Pett proceeded to

accomplish the order with all dispatch. The little ship was in

length by the keel 28 feet, in breadth 12 feet, and very curiously

garnished within and without with painting and carving. After

working by torch and candle-light, night and day, the ship was

launched, and set sail for the Thames, with the noise of drums,

trumpets, and cannon, at the beginning of March, 1604. After passing

through a great storm at the Nore, the vessel reached the Tower,

where the King and the young Prince inspected her with delight. She

was christened Disdain by the Lord High Admiral, and Pett was

appointed captain of the ship.

After his return to Chatham, Pett, at his own charge, built a small

ship at Gillingham, of 300 tons, which he launched in the same year,

and named the Resistance. The ship was scarcely out of hand, when Pett was ordered to Woolwich, to prepare the

Bear and other vessels

for conveying his patron, the Lord High Admiral, as an Ambassador

Extraordinary to Spain, for the purpose of concluding peace, after a

strife of more than forty years. The Resistance was hired by the

Government as a transport, and Pett was put in command. He seems to

have been married at this time, as he mentions in his memoir that he

parted with his wife and children at Chatham on the 24th of March,

1605, and that he sailed from Queen-borough on Easter Sunday.

During the voyage to Lisbon the Resistance became separated from the

Ambassador's squadron, and took refuge in Corunna. She then set sail

for Lisbon, which she reached on the 24th of April; and afterwards

for St. Lucar, on the Guadalquivir, near Seville, which she reached

on the 11th of May following. After revisiting Corunna, "according

to instructions," on the homeward voyage, Pett directed his course

for England, and reached Rye on the 26th of June, "amidst much rain,

thunder, and lightning." In the course of the same year, his brother

Joseph died, and Phineas succeeded to his post as master shipbuilder

at Chatham. He was permitted, in conjunction with one Henry Farvey

and three others, to receive the usual reward of 5s. per ton for

building five new merchant ships, [p.34]

most probably for East Indian commerce, now assuming large

dimensions. He was despatched by the Government to Bearwood, in

Hampshire, to make a selection of timber from the estate of the Earl

of Worcester for the use of the navy, and on presenting his report

3,000 tons were purchased. What with his building of ships, his

attendance on the Lord Admiral to Spain, and his selection of timber

for the Government, his hands seem to have been kept very full

during the whole of 1605.

In July, 1606, Pett received private instructions from the Lord High

Admiral to have all the King's ships "put into comely readiness" for

the reception of the King of Denmark, who was expected on a Royal

visit. "Wherein," he says, "I strove extraordinarily to express my

service for the honour of the kingdom; but by reason the time

limited was short, and the business great, we laboured night and day

to effect it, which accordingly was done, to the great honour of our

sovereign king and master, and no less admiration of all strangers

that were eye-witnesses to the same." The reception took place on

the 10th of August, 1606.

Shortly after the departure of His Majesty of Denmark, four of the

Royal ships—the Ark, Victory, Golden Lion, and

Swiftsure—were

ordered to be dry-docked; the two last mentioned at Deptford, under

charge of Matthew Baker; and the two former at Woolwich, under that

of Pett. For greater convenience, Pett removed his family to

Woolwich. After being elected and sworn Master of the Company of

Shipwrights, he refers in his manuscript, for the first time, to his

magnificent and original design of the Prince Royal. [p.35]

"After settling at Woolwich," he says, "I began a curious model for

the prince my master, most part whereof I wrought with my own

hands." After finishing the model, he exhibited it to the Lord High

Admiral, and, after receiving his approval and commands, he

presented it to the young prince at Richmond. "His Majesty (who was

present) was exceedingly delighted with the sight of the model, and

passed some time in questioning the divers material things

concerning it, and demanded whether I could build the great ship in

all parts like the same; for I will, says His Majesty, compare them

together when she shall be finished. Then the Lord Admiral commanded

me to tell His Majesty the story of the Three Ravens [p.36]

I had seen at Lisbon, in St. Vincent's Church; which I did as well

as I could, with my best expressions, though somewhat daunted at

first at His Majesty's presence, having never before spoken before

any King."

Before, however, he could accomplish his purpose, Pett was overtaken

by misfortunes. His enemies, very likely seeing with spite the

favour with which he had been received by men in high position,

stirred up an agitation against him. There may, and there very

probably was, a great deal of jobbery going on in the dockyards. It

was difficult, under the system which prevailed, to have any proper

check upon the expenditure for the repair and construction of ships. At all events, a commission was appointed for the purpose of

inquiring into the abuses and misdemeanours of those in office; and Pett's enemies took care that his past proceedings should be

thoroughly overhauled,—together with those of Sir Robert Mansell,

then Treasurer to the Navy; Sir John Trevor, surveyor; Sir Henry

Palmer, controller; Sir Thomas Blather, victualler; and many others.

While the commission was still sitting and holding what Pett calls

their "malicious proceedings," he was able to lay the keel of his

new great ship upon the stocks in the dock at Woolwich on the 20th

of October, 1608. He had a clear conscience, for his hands were

clean. He went on vigorously with his work, though he knew that the

inquisition against him was at its full height. His enemies reported

that he was "no artist, and that he was altogether insufficient to

perform such a service" as that of building his great ship. Nevertheless, he persevered, believing in the goodness of his cause.

Eventually, he was enabled to turn the tables upon his accusers, and

to completely justify himself in all his transactions with the king,

the Lord Admiral, and the public officers, who were privy to all his

transactions. Indeed, the result of the enquiry was not only to

cause a great trouble and expense to all the persons accused, but,

as Pett says in his Memoir, "the Government itself of that royal

office was so shaken and disjoined as brought almost ruin upon the

whole Navy, and a far greater charge to his Majesty in his yearly

expense than ever was known before." [p.37]

In the midst of his troubles and anxieties, Pett was unexpectedly

cheered with the presence of his "Master" Prince Henry, who

specially travelled out of his way from Essex to visit him at

Woolwich, to see with his own eyes what progress he was making with

the great ship. After viewing the dry dock, which had been

constructed by Pett, and was one of the first, if not the very first

in England,—his Highness partook of a banquet which the shipbuilder

had hastily prepared for him in his temporary lodgings.

One of the circumstances which troubled Pett so much at this time,

was the strenuous opposition of the other shipbuilders to his plans

of the great ship. There never had been such a frightful innovation. The model was all wrong. The lines were detestable. The man who

planned the whole thing was a fool, a "cozener" of the king, and the

ship, suppose it to be made, was "unfit for any other use but a

dung-boat!" This attack upon his professional character weighed very

heavily upon his mind.

He determined to put his case in a straightforward manner before the

Lord High Admiral. He set down in writing in the briefest manner

everything that he had done, and the plots that had been hatched

against him; and beseeched his lordship, for the honour of the

State, and the reputation of his office, to cause the entire matter

to be thoroughly investigated "by judicious and impartial persons." After a conference with Pett, and an interview with his Majesty, the

Lord High Admiral was authorised by the latter to invite the Earls

of Worcester and Suffolk to attend with him at Woolwich, and bring

all the accusers of Pett's design of the great ship before them for

the purpose of examination, and to report to him as to the actual

state of affairs. Meanwhile Pett's enemies had been equally busy. They obtained a private warrant from the Earl of Northampton [p.38]

to survey the work; "which being done," says Pett, "upon return of

the insufficiency of the same under their hands, and confirmation by

oath, it was resolved amongst them I should be turned out, and for

ever disgraced."

But the lords appointed by the King now interfered between Pett and

his adversaries. They first inspected the ship, and made a diligent

survey of the form and manner of the work and the goodness of the

materials, and then called all the accusers before them to hear

their allegations. They were examined separately. First, Baker the

master shipbuilder was called. He objected to the size of the ship,

to the length, breadth, depth, draught of water, height of jack,

rake before and aft, breadth of the floor, scantling of the timber,

and so on. Then another of the objectors was called; and his

evidence was so clearly in contradiction to that which had already

been given, that either one or both must be wrong. The principal

objector, Captain Waymouth, next gave his evidence; but he was able

to say nothing to any purpose, except giving their lordships "a

long, tedious discourse of proportions, measures, lines, and an

infinite rabble of idle and unprofitable speeches, clean from the

matter."

The result was that their lordships reported favourably of the

design of the ship, and the progress which had already been made. The Earl of Nottingham interposed his influence; and the King

himself, accompanied by the young Prince, went down to Woolwich, and

made a personal examination. [p.39] A great many witnesses were again examined, twenty-four on one side,

and twenty-seven on the other. The King then carefully examined the

ship himself: "the planks, the tree-nails, the workmanship, and the

cross-grained timber." "The cross-grain," he concluded, "was in the

men and not in the timber." After all the measurements had been made

and found correct, "his Majesty," says Pett, "with a loud voice

commanded the measurers to declare publicly the very truth; which

when they had delivered clearly on our side, all the whole multitude

heaved up their hats, and gave a great and loud shout and

acclamation. And then the Prince, his Highness, called with a high

voice in these words: 'Where be now these perjured fellows that dare

thus abuse his Majesty with these false accusations? Do they not

worthily deserve hanging?'"

Thus Pett triumphed over all his enemies, and was allowed to finish

the great ship in his own way. By the middle of September 1610, the

vessel was ready to be "strucken down upon her ways"; and a dozen of

the choice master carpenters of his Majesty's navy came from Chatham

to assist in launching her. The ship was decorated, gilded, draped,

and garlanded; and on the 24th the King, the Queen, and the Royal

family came from the palace at Theobald's to witness the great

sight. Unfortunately, the day proved very rough; and it was little

better than a neap tide. The ship started very well, but the wind overblew the tide; she caught in the dock-gates, and settled hard

upon the ground, so that there was no possibility of launching her

that day.

This was a great disappointment. The King retired to the palace at

Greenwich, though the Prince lingered behind. When he left, he

promised to return by midnight, after which it was proposed to make

another effort to set the ship afloat. When the time arrived, the

Prince again made his appearance, and joined the Lord High Admiral,

and the principal naval officials. It was bright moonshine. After

midnight the rain began to fall, and the wind to blow from the

southwest. But about two o'clock, an hour before high water, the

word was given to set all taut, and the ship went away without any

straining of screws and tackles, till she came clear afloat into the

midst of the Thames. The Prince was aboard, and amidst the blast of

trumpets and expressions of joy, he performed the ceremony of

drinking from the great standing cup, and throwing the rest of the

wine towards the half-deck, and christening the ship by the name of

the Prince Royal. [p.41-1]

Prince Royal by Willem

van de Velde the Younger. [p.41-2]

Picture Wikipedia.

The dimensions of the ship may be briefly described. Her keel was

114 feet long, and her cross-beam 44 feet. She was of 1,100 tons

burthen, and carried 64 pieces of great ordnance. She was the

largest ship that had yet been constructed in England.

The Prince Royal was, at the time she was built, considered one of

the most wonderful efforts of human genius. Mr. Charnock, in his

'Treatise on Marine Architecture,' speaks of her as abounding in

striking peculiarities. Previous to the construction of this ship,

vessels were built in the style of the Venetian galley, which

although well adapted for the quiet Mediterranean, were not suited

for the stormy northern ocean. The fighting ships also of the time

of Henry VIII. and Elizabeth were too full of "top-hamper" for

modern navigation. They were oppressed by high forecastles and

poops. Pett struck out entirely new ideas in the build and lines of

his new ship; and the course which he adopted had its effect upon

all future marine structures. The ship was more handy, more wieldy,

and more convenient. She was unquestionably the first effort of

English ingenuity in the direction of manageableness and simplicity. "The vessel in question," says Charnock, "may be considered the

parent of the class of shipping which continues in practice even to

the present moment."

It is scarcely necessary to pursue in detail the further history of

Phineas Pett. We may briefly mention the principal points. In 1612,

the Prince Royal was appointed to convey the Princess Elizabeth and

her husband, The Palsgrave, to the Continent. Pett was on board the

ship, and found that "it wrought exceedingly well, and was so yare

of conduct that a foot of helm would steer her." While at Flushing,

"such a multitude of people, men, women, and children, came from

all places in Holland to see the ship, that we could scarce have

room to go up and down till very night."

About the 27th of March, 1616, Pett bargained with Sir Walter

Raleigh to build a vessel of 500 tons, [p.42]

and received £500 from him on account. The King, through the

interposition of the Lord Admiral, allowed Pett to lay her keel on

the galley dock at Woolwich. In the same year he was commissioned by

the Lord Zouche, now Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, to construct a

pinnace of 40 tons, in respect of which Pett remarks, "towards the

whole of the hull of the pinnace, and all her rigging, I received

only £100 from the Lord Zouche, the rest Sir Henry Mainwaring

(half-brother to Raleigh) cunningly received on my behalf, without

my knowledge, which I never got from him but by piecemeal, so that

by the bargain I was loser £100 at least."

Pett fared much worse at the hands of Raleigh himself. His great

ship, the Destiny, was finished and launched in December, 1616. "I

delivered her to him," says Pett, "on float, in good order and

fashion; by which business I lost £700, and could never get any

recompense at all for it; Sir Walter going to sea and leaving me

unsatisfied." [p.43-1] Nor

was this the only loss that Pett met with this year. The King, he

states, "bestowed upon me for the supply of my present relief the

making of a knight-baronet," which authority Pett passed to a

recusant, one Francis Ratcliffe, for £700; but that worthy defrauded

him, so that he lost £30 by the bargain.

Next year, Pett was despatched by the Government to the New Forest

in Hampshire, "where," he says, "one Sir Giles Mompesson [p.43-2]

had made a vast waste in the spoil of his Majesty's timber, to

redress which I was employed thither, to make choice out of the

number of trees he had felled of all such timber as was useful for

shipping, in which business I spent a great deal of time, and

brought myself into a great deal of trouble." About this period,

poor Pett's wife and two of his children lay for some time at

death's door. Then more enquiries took place into the abuses of the

dockyards, in which it was sought to implicate Pett. During the next

three years (1618-20) he worked under the immediate orders of the

Commissioners in the New Dock at Chatham.

In 1620, Pett's friend Sir Robert Mansell was appointed General of

the Fleet destined to chastise the Algerine pirates, who still

continued their depredations on the shipping in the Channel, and the

King thereupon commissioned Pett to build with all dispatch two

pinnaces, of 120 and 80 tons respectively. "I was myself," he says,

"to serve as Captain in the voyage"—being glad, no doubt, to escape

from his tormentors. The two pinnaces were built at Ratcliffe, and

were launched on the 16th and 18th of October, 1620. On the 30th, Pett sailed with the fleet, and after driving the pirates out of the

Channel, he returned to port after an absence of eleven months.

His enemies had taken advantage of his absence from England to get

an order for the survey of the Prince Royal, his masterpiece; the

result of which was, he says, that "they maliciously certified the

ship to be unserviceable, and not fit to continue—that what charges

should be bestowed upon her would be lost." Nevertheless, the

Prince

Royal was docked, and fitted for a voyage to Spain. She was sent

thither with Charles Prince of Wales and the Duke of Buckingham, the

former going in search of a Spanish wife. Pett, the builder of the

ship, was commanded to accompany the young Prince and the Duke.

The expedition sailed on the 24th of August, 1623, and returned on

the 14th of October. Pett was entertained on board the Prince Royal,

and rendered occasional services to the officers in command, though

nothing of importance occurred during the voyage. The Prince of

Wales presented him with a valuable gold chain as a reward for his

attendance. In 1625, Pett, after rendering many important services

to the Admiralty, was ordered again to prepare the Prince Royal for

sea. She was to bring over the Prince of Wales's bride from France. While the preparations were making for the voyage, news reached

Chatham of the death of King James. Pett was afterwards commanded to

go forward with the work of preparing the Prince Royal, as well as

the whole fleet, which was intended to escort the French Princess,

or rather the Queen, to England. The expedition took place in May,

and the young Queen landed at Dover on the 12th of that month.

Pett continued to be employed in building and repairing ships, as

well as in preparing new designs, which he submitted to the King and

the Commissioners of the Navy. In 1626, he was appointed a joint

commissioner,

with the Lord High Admiral, the Lord Treasurer Marlborough, and

others, "to enquire into certain alleged abuses of the Navy, and to

view the state thereof, and also the stores thereof," clearly

showing he was regaining his old position. He was also engaged in

determining the best mode of measuring the tonnage of ships. [p.45] Four years later

he was again appointed a commissioner for making

"a general survey of the whole navy at Chatham." For this and his

other services the King promoted Pett to be a principal officer of

the Navy, with a fee of £200 per annum. His patent was sealed on

the 16th of January, 1631. In the same year the King visited

Woolwich to witness the launching of the Vanguard, which Pett had

built; and his Majesty honoured the shipwright by participating in a

banquet at his lodgings.

From this period to the year 1637, Pett records nothing of

particular importance in his autobiography. He was chiefly occupied

in aiding his son Peter—who was rapidly increasing his fame as a

shipwright—in repairing and building first-class ships of war. As Pett had, on an early occasion in his life, prepared a miniature

ship for Prince Henry, eldest son of James I., he now proceeded, to

prepare a similar model for the Prince of Wales, the King's eldest

son, afterwards Charles II. This model was presented to the Prince

at St. James's, "who entertained it with great joy, being purposely

made to disport himself withal." On the next visit of his Majesty to

Woolwich, he inspected the progress made with the Leopard, a

sloop-of-war built by Peter Pett. While in the hold of the vessel,

the King called Phineas to one side, and told him of his resolution

to have a great new ship built, and that Phineas must be the

builder. This great new ship was The Sovereign of the Seas,