|

FOOTNOTES.

|

p.10 |

Tacitus, 'Life of Agricola.' |

|

p.13 |

Harrison's Preface to Holinshed's Chronicle, i. 313. |

|

p.20-1 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "View across the

Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve eastwards towards the

area of high ground around Epworth known as the Isle of Axholme.

You can make out the water tower on the horizon easily enough, but

the windmills need a closer look." |

|

p.20-2 |

De la Pryme, 'History of the Level of Hatfield

Chase.' |

|

p.23 |

It has been observed that the buildings in many of

the old Fen towns to this day have a Flemish appearance, as the

names of many of the inhabitants have evidently a foreign origin.

Those of Descow, Le Plas, Egar, Bruynne, &c., are said to be still

common. Among the settlers in the level of Hatfield was Mathew

de la Pryme, who emigrated from Ypres in Flanders during the

persecutions of the Duke of Alva. The Prymes of Cambridge are

lineally descended from him. Tablets to several of the name

are still to be found in Hatfield Church. |

|

p.25-1 |

R. Ansbie writes the Duke of Buckingham from Tickill

Castle, under date the 21st August, 1628, as follows:—"What has

happened betwixt Mr. Vermuyden's friends and workmen and the people

of the Isle of Axholme these inclosed will give a taste. Great

riots have been committed by the people, and a man killed by the

Dutch party, the killing of whom is conceived to be murder in all

who gave direction for there go armed that day. These outrages

will produce good effects. They will procure conformity in the

people, and enforce Vermuyden to sue for favour at the Duke's

hands,—if not for himself, for divers of his friends, especially for

Mr. Saines, a Dutchman, who has an adventure of £13,000 in this

work. Upon examination of the rest of Vermuyden's people,

thinks it will appear that he gave them orders to go armed."—'State

Papers,' vol. cxiii. 38. |

|

p.25-2 |

F. Vernatti, one of the Dutch capitalists who had

contributed largely towards the cost of the works, writes to

Monsieur St. Gillis, in October, 1628: "The absence of Mr.

Vermuyden, and the great interest the writer takes in the business

of embankment at Haxey, has led him to engage in it with eye and

hand. The mutinous people have not only desisted from their

threats, but now give their work to complete the dyke, which they

have fifty times destroyed and thrown into the river. A royal

proclamation made by a serjeant-at-arms in their village,

accompanied by the sheriff and other officials, with fifty horsemen,

and an exhortation mingled with threats of fire and vengeance, have

produced this result." —'State Papers,' vol. cxix. 73. |

|

p.26-1 |

'State Papers,' Vol. cxlvii. 21. |

|

p.26-2 |

Warrant of Council, dated Whitehall, May 12th,

1630.—'State Papers,' vol. clxvi. 56. |

|

p.27-1 |

Affidavit of George Johnson, servant of Sir Cornelius

Vermuyden.—'State Papers,' vol. clxx. 17. |

|

p.27-2 |

The Dutch settlers lived for the most part in single

houses, dispersed through the newly-recovered country. A house

built by Vermuyden remains. It was chiefly of timber, and what

is called stud-bound. It was built round a quadrangular

court. The eastern front was the dwelling-house. The

other three sides were stables and barns. Another good house

was built by Mathew Valkenburgh, on the Middle Ing, near the Don,

which afterwards became the property of the Boynton family.

Sir Philibert Vernatti and the two De Witts erected theirs near the

Idle. A chapel for the settlers was also erected at Sandtoft,

in which the various ordinances of religion were performed, and the

public service was read alternately in the Dutch and French

languages.—The Rev. Joseph Hunter's 'History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster,' 1828, vol. i. 165-6. |

|

p.29-1 |

Colonel Lilburne attempted an ineffectual defence of

himself in the tract entitled 'The Case of the Tenants of the Manor

of Epworth truly stated by Col. Jno. Lilburne,' Nov. 18th, 1651. |

|

p.29-2 |

For a long time after this, indeed, the commoners

continued at war with the settlers, and both were perpetually

resorting to the law—of the courts as well as of the strong hand.

One Reading, a counsellor, "Is engaged to defend the rights of the

drainers or participants, but his office proved a very dangerous

one. The fen-men regarded him as an enemy, and repeatedly

endeavoured to destroy him. Once they had nearly burned him

and his family in their beds. Reading died in 1716, at a

hundred years old, fifty of which he had passed in constant danger

of personal violence, having fought "thirty-one set battles" with

the fen-men in defence of the drainers' rights. |

|

p.33-1 |

We insert the map on the preceding page at this

place, although it includes the drainage-works subsequently

constructed, in order that the reader may be enabled more readily to

follow the history of the various cuts and drains executed in the

Fen country from about the middle of the sixteenth century down to

about the year 1830. |

|

p.33-2 |

A clow is a sluice regulated by being lifted or

dropped perpendicularly, like a portcullis. The other sluices

open and shut like gates. |

|

p.34 |

'The Drayner Confirmed,' tract, 1629. |

|

p.35 |

Powte—the old English word for the sea-lamprey.

|

THE

POWTE'S

COMPLAINT.

Come, Brethren of the water, and let its all assemble,

To treat upon this Matter, which makes us quake and

tremble;

For we shall rue, if it be true that Fens be undertaken,

And where we teed in Fen and Reed, they'll feed both

Beef and Bacon.

They'll sow both Beans and Oats, where never Man yet

thought it;

Where Men did row in Boats, ere Undertakers bought it;

But, Ceres, thou behold us now, let wild Oats be

their venture,

Oh, let the Frogs and miry Bogs destroy where they do

enter.

Behold the great Design, which they do now determine,

Will make our Bodies pine, a prey to Crows and vermin;

For they do mean all Fens to drain, and Waters

overmaster,

All will be dry, and we must die—'cause Essex Calves

want pasture.

Away with Boats and Rudder, farewel both Boots and

Skatches,

No need of one nor t'other, Men now make better Matches;

Stilt-makers all, and Tanners, shall complain of this

Disaster,

For they will make each muddy lake for Essex Calves a

Pasture.

The feather'd Fowls have Wings, to fly to other Nations;

But we have no such things, to help our Transportations;

We must give place, O grevious Case! to hornèd Beasts

and Cattle,

Except that we can all agree to drive them out by Battel.

Wherefore let us intreat our antient Water-Nurses

To shew their Power so great as t' help to drain their

Purses;

And send us good old Captain Flood to lead us out to

Battel,

Then Two-pennyJack, with Scales on 's Back, will drive

out all the

Cattle.

This Noble Captain yet was never know to fail us,

But did the conquest get of all that did assail us;

His furious Rage none could assuage; but to the World's

great

Wonder,

He tears down Stones, and breaks their Cranks and

Whirligigs

asunder.

God [Eolus we do thee pray that thou wilt not be

wanting;

Thou never said'st us nay—now listen to our canting;

Do thou deride their Hope and Pride that purpose our

Confusion,

And send a Blast that they in haste may work no good

Conclusion.

Great Neptune, God of Seas, this Work must needs provoke

ye;

They mean thee to disease, and with Fen-Water chock

thee;

But with thy Mace do thou deface, and quite confound

this matter,

And send thy Sands to make dry lands when they shall

want fresh

Water.

And eke we pray thee, Moon, that thou wilt be

propitious,

To see that nought be done to prosper the Malicious;

Tho' Summer's Heat hath wrought a Feat, whereby

themselves they

flatter,

Yet be so good as send a Flood, lest Essex Calves want

Water. |

|

|

p.39 |

Lives of Eminent British Statesmen (Lardner's

'Cabinet Cyclopædia,' vol. vi. p.60). |

|

p.41 |

"The party under Vermuyden waits the King's army, and

is about Deeping; has a command to join with Sir John Gell, if he

commands him."—Cromwell's Letter to Fairfax, 4th June, 1645.

This Vermuyden resigned his commission a few days before the battle

of Naseby, having, as he alleged, special reasons requiring his

presence beyond the seas, whence he does not seem to have returned

until after the Restoration. In 1665 we find him a member of

the Corporation of the Bedford Level. |

|

p.43 |

The St. John's Eau, being a straight cut, is known in

the district as "The Poker;" and Marshland Cut, being in the shape

of a pair of tongs, is commonly called "Tongs Drain." |

|

p.46 |

Since the above passage was written, in 1861, its

truth has been amply confirmed by the blowing up of the Middle Level

sluice, about three miles above Lynn, by which some 10,000 acres of

the richest agricultural land in Marshland were completely

submerged. Great loss was thereby occasioned and a fertile

crop of lawsuits has followed the inundation. The Middle Level

Drain was admirably planned by the late James Walker, C.E., and was

supposed to have been as admirably executed, at a cost of over

£400,000. For ten years it was a complete success; but the

foundations of the out-fall sluice having become undermined by the

tidal scour in the Ouse, the masonry fell in, and the waters

immediately rushed in upon the land and resumed possession.

The drainage has since been restored in a very able and efficient

manner by Mr. Hawkshaw, and Marshland is again under cultivation. |

|

p.47 |

When Dr. Whalley was presented by the Bishop of Ely

to the rectory of Hagworthingham-in-the-Fens, it was with the

singular proviso that he was not to reside in it, as the air was

fatal to any but a native. '(Journals and Correspondence of T. S.

Whalley, D.D.) Statistics, however, prove that the Fen

districts are the exceptional haunts of disease. The

Registrar-General, in one of his recent reports, states that, whilst

the mortality of Pau in the Pyrenees, a place resorted to by British

invalids on account of its salubriousness, is 23 in 1,000, that of

Ely is only 17 in 1,000. |

|

p.48 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "The New River is

something of a misnomer since it is neither a river nor new.

It is an aqueduct built under the direction of Sir Hugh Myddleton

between 1607 and 1612 to bring fresh drinking water from Chadwell

and Amwell Springs near Ware about 40 miles down the Lee Valley to

London. It is seen here with London Road beyond the railings

to the left. |

|

p.49 |

The conduits used, in former times, to be yearly

visited with considerable ceremony. For instance, we find

that—"On the 18th of September, 1862, the Lord Mayor (Harper), the

Aldermen, with many worshipful persons, and divers of the Masters

and Wardens of the twelve companies, rode to the Conduit's-head [now

the site of Conduit Street, New Bond Street] for to see them after

the old custom. And afore dinner they hunted the hare and

killed her and thence to dinner at the head of the Conduit.

There was a good number entertained with good cheere by the

Chamberlain, and, after dinner, they hunted the fox. There was

a great cry for a mile, and at length the hounds killed him at the

end of St. Giles's. Great hallooing at his death, and blowing

of hornes; and thence the Lord Mayor with all his company, rode

through London to his place in Lombard Street." Stow's 'Survey

of London.'—It would appear that the ladies of the Lord Mayor and

Aldermen attended on these jovial occasions, riding in waggons. |

|

p.50 |

'Corporation Records,' Index No. I., fo. 181 b. |

|

p.51-1 |

'Progresses of James I.,' vol. ii., 699. The

Corporation records contain numerous references to the preservation

of the purity of the water in the river. The Thames also

furnished a large portion of the food of the city, and then abounded

in salmon and other fish, the London fishermen constituting a large

class. We find numerous proclamations issued relative to the

netting of the "salmon and porpoises," wide nets and wall nets being

especially prohibited. Fleets of swans on the Thames were a

picturesque feature of the river down even to the time of James II. |

|

p.51-2 |

The water carrier was commonly called a "Cob," and

Ben Jenson seems to have given a sort of celebrity to the character

by his delineation of "Cob" in his 'Every Man in his Humour.'

Gifford, in a note on the play, pointed out that there is an avenue

still called "Cob's Court," in Broadway, Blackfriars; not improbably

(he adds) from its having formerly been inhabited principally by the

class of water carriers. |

|

p.52-1 |

The river pumping-leases continued in the family of

the Morices until 1701, when the then owner sold his rights to

Richard Seams for £38,000, and by him they were afterwards

transferred to the New River Company at a still higher price. |

|

p.52-2 |

Act 13 Eliz. c. 18. |

|

p.53-1 |

3 Jac. c. 18. |

|

p.53-2 |

4 Jac. c. 12. |

|

p.54 |

Dunsford's 'Historical Memoirs,' p. 106. |

|

p.56 |

The tradition survives to this day that Sir Francis

Drake did not cut the Leet by the power of money and engineering

skill, but by the power of magic. It is said of him that,

calling for his horse, he mounted it and rode about Dartmoor until

he came to a spring sufficiently copious for his design, on which,

pronouncing some magical words, he wheeled round, and, starting off

at a gallop, the stream formed its own channel, and followed his

horse's heels into the town. |

|

p.57 |

The plague was then a frequent visitor in the city.

Numerous proclamations were made by the Lord Mayor and Corporation

on the subject—proclamations ordering wells and pumps to be drawn,

and streets to be cleaned,—and precepts for removing hogs out of

London, and against the selling or eating of pork. Wherever

the plague was in a house, the inhabitant thereof was enjoined to

set up outside a pole of the length of seven feet, with a bundle of

straw at the top, as a sign that the deadly visitant was within.

Wife, children, and servants belonging to that house must carry

white rods in their hands for thirty-six days before they were

considered "purged." It was also ordered subsequently, that on

the street-door of every house infected, or upon a post thereby, the

inhabitant must exhibit imprinted on paper a token of St. Anthony's

Cross, otherwise called the sign of the Taw T, that all persons

might have knowledge that such house was infected—'Corporation of

City of London Records,' jor. 12, fol. 136. No. 1. Years 1590 to

1694. |

|

p.61 |

It may be remembered that Rubens was accustomed to be

paid for his pictures by so many links of gold chain. |

|

p.62 |

He resided at the old Elizabethan house in Highgate,

afterwards occupied as an inn, called the "King's Head." |

|

p.63-1 |

'Tour in Wales,' vol. ii., p. 31. Ed. 1784. |

|

p.63-2 |

Williams's 'Ancient and Modern Denbigh,' p. 105. |

|

p.66 |

"26th of February, 1604. To Hugh Middleton,

Goldsmith, the sum of £250 for a pendant of one diamond bestowed

upon the Queen by His Majesty. By writ dated 9th day of

January, 1604, £250."—Extract from the 'Pell Records.' [The

sum named would be equivalent to about £1,000 of our present money.

The Queen's passion for jewels may be inferred from the circumstance

stated by Dr. Steven in his 'Memoir of George Heriot,' the King's

goldsmith (founder of Heriot's Hospital, Edinburgh), that during the

ten years which immediately preceded the accession of King James to

the throne of Great Britain, Heriot's bills for the Queen's jewels

alone could not amount to less than £50,000 sterling.] |

|

p.74 |

Theobalds, a singularly beautiful place, where

Elizabeth held counsel with Burleigh, James often lived, and Charles

played with his children. The palace was ordered to be pulled

down by the Long Parliament, in spite of the commissioners' report

that it was "an excellent building in very good repair;" and, the

materials having been sold to the highest bidder, the proceeds were

divided amongst the soldiers of Cromwell and Fairfax. The

materials alone realised not less than £8,275.11s. |

|

p.77 |

A large print was afterwards published by G. Bickham,

in commemoration of the event, entitled 'Sir Hugh Myddelton's

Glory.' It represents the scene of the ceremony, the

reservoir, with the stream rushing into it; the Lord Mayor (Sir John

Swinnerton) on a white palfrey, pointing exultingly to Sir Hugh; the

Recorder, Sir Henry Montague, afterwards Lord Keeper and Earl of

Manchester, and by his side the Lord Mayor elect, the projector's

brother, Maister Thomas Myddelton. Various figures

gesticulating their admiration occupy the foreground, whilst the

foot of the print is garnished with little "chambers," or miniature

mortars, spontaneously exploding. There is a copy of the

original print in the British Museum. |

|

p.80-1 |

In Pennant's 'London' it is stated that the original

shares in the concern were £100 each, whereas Entick makes them to

have amounted to not less than £7,000 each! This is only

another illustration of the hap-hazard statements put forth

respecting Sir Hugh and his works. The original cost of the

New River probably did not amount to more than £18,000, in which

case the capital represented by each original share would be about

£250. |

|

p.80-2 |

On the occasion of its subsequent confirmation by

parliament, Sir Edward Coke said: "This is a very good bill, and

prevents one great mischief that hangs over the city. Nimis

potatio: frequens cendium." |

|

p.81 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "the large East

window (erected in 1962) by A. E. Buss of Goddard & Gibbs,

commemorates the building of the New River, between 1604 and 1613.

It shows the risen Christ ascending to glory, and various scenes of

the New River construction work, together with memorials to Sir Hugh

Myddelton, Dame Alice Owen (a great local benefactor) and the

Corporation of the City of London (who remain patrons of the parish

today)." |

|

p.86 |

'Domestic Calendar of State Papers.' Docquet,

13th August, 1620, |

|

p.87 |

The above view represents the present state of the

entrance to Brading Haven. A wide ridge of drifted sand lies across

it, in front of the old bank raised by Myddelton, which extended

from a point below the hill under " Mrs. Grant's house," a little to

the westward of the village of Bembridge (seen on the opposite

shore) to what are now called "The Boat Houses," situated towards

the northern side of the haven, and behind the sand-ridge extending

across the view. The black piles driven into the bottom of the haven

in the process of embankment are still to be seen sticking up at low

water; and only a few years since the old gates which served for a

sluice were dug up near the Boat Houses. At the extremity of the

sand-ridge there is a ferry across to the village of Bembridge, in

front of which is the Darrow entrance into the haven. There have

been serious encroachments of the sea on that side of late years,

and the channel has become much impeded: so much so that it has been

feared that the navigation would be lost. The old church-tower of

St. Helen's, faced with brick and whitewashed, on the right of the

view, is still used as a sea-mark. |

|

p.94-1 |

Sloane MS. (British Museum), vol. ii. 4177.

Also 'Calendar of Domestic State Papers,' Oct. 19th, 1622: "Grant to

Hugh Myddelton of the rank of Baronet, granting discharge of £1,095

due on being made a Baronet." The usual statement is to the

effect that Myddelton was knighted on the occasion of the opening of

the New River in 1613. But this was not the case, as it will

be found from the patent for draining land taken out by him in 1621

(see ante, p. 86), that

he was then described as simply "Citizen and Goldsmith, of London."

Nor is his name to be found in any contemporary list of King James's

Knights. |

|

p.94-2 |

Harleian MS., No. 1507, Art. 40. (British

Museum.) |

|

p.95 |

Subsequent to 1636, Thomas Bushell (who purchased the

lease) Paid £1,000 per annum to the King; and some years after, in

1647, we find him agreeing to pay £2,500 per annum to the

Parliament. As a Curious fact, we may here add that, under

date Die Sabbati, 14 August, 1641, Parliament granted an order or

license to Thomas Bushell to dig turf on the King's wastes within

the limits of Cardiganshire, for the purpose of smelting and

refining the lead ores, &c., his predecessor (Myddelton) having used

up almost all the wood growing in the neighbourhood of the mines. |

|

p.96 |

Dated 22nd October, 1636. The prayer of

Bushell's petition to Charles I. is, that His Majesty will ratify

his agreement with Lady Myddelton (by that time a widow) for the

purchase of the residue of her lease. |

|

p.97 |

In these rampant days of joint-stock enterprise, we

are not surprised to observe that a scheme has been set on foot to

work the long-abandoned silver and lead mines of Sir Hugh Myddelton.

With the greatly improved mining machinery of modern times, it is

not unreasonable to anticipate a considerable measure of success

from such an undertaking. |

|

p.98 |

A long time passed before the attempt was made to

reclaim the large tract of land at Traeth-Mawr; but after the lapse

of two centuries, it was undertaken by William Alexander Madocks,

Esq., and accomplished in spite of many formidable difficulties.

Two thousand acres of Penmorfa Marsh were first enclosed on the

western side of the river, after which an embankment was constructed

across the estuary, about a mile in length, by which 6,000

additional acres were secured. The sums expended on the works

are said to have exceeded £100,000; but the expenditure has proved

productive, and the principal part of the reclaimed land is now

under cultivation. Tremadoc, or Madock's Town, and Port Madoc,

are two thriving towns, built by the proprietor on the estate thus

won from the sea. |

|

p.100-1 |

The tradition still survives that Sir Hugh retired in

his old age to the village of Kemberton, near Shiffnal, Salop, where

he lived in great indigence under the assumed name of Raymond, and

that he was there occasionally employed as a street paviour!

The parish register is said to contain an entry of his burial on the

11th of March, 1702; by which date Hugh Myddelton, had he lived

until then, would have been about 150 years old! The entry in

the register was communicated by the rector of the parish in 1809 to

the 'Gentleman's Magazine' (vol. lxxix., p. 795), but it is scarcely

necessary to point out that it can have no reference whatever to the

subject of this memoir. |

|

p.100-2 |

On the 24th June, 1632, Lady Myddelton memorialised

the Common Council of London with reference to the loan of £3,000,

advanced to Sir Hugh, which does not seem to have been repaid; and

more than two years later, on the 10th Oct., 1631, we find the

Corporation allowed £1,000 of the amount, in consideration of the

public benefit conferred on the city by Sir Hugh through the

formation of the New River, and for the losses alleged to have been

sustained by him through breaches in the water-pipes on the occasion

of divers great fires, as well as for the "present comfort" of Lady

Myddelton. It is to be inferred that the balance of the loan

of £3,000 was then repaid. Lady Myddelton died at Bush Hill on

the 19th July, 1643, aged sixty-three, and was interred in the

chancel of Edmonton Church, Middlesex. On her monumental

tablet it is stated that she was " the mother of fifteen children." |

|

p.101 |

Simon's son Hugh was created a Baronet, of Hackney,

Middlesex, in 1681. He married Dorothy, the daughter of Sir

William OgIander, of Nunwell, Baronet. |

|

p.102 |

Several of the descendants of Sir Hugh Myddelton,

when reduced in circumstances, obtained assistance from this fund.

It has been stated, and often repeated, that Lady Myddelton, after

her husband's death, became a pensioner of the Goldsmiths' Company,

receiving from them £20 a year. But this annuity was paid, not

to the widow of the first Sir Hugh, but to the mother of the last

Sir Hugh, more than a century later. The last who bore the

title was an unworthy scion of this distinguished family. He

could raise his mind no higher than the enjoyment of a rummer of

ale; and towards the end of his life existed upon a pension granted

him by the New River Company. The statements so often

published (and which, on more than one occasion, have brought poor

persons up to town from Wales to make inquiries) as to an annuity of

£100 said to have been left by Sir Hugh and unclaimed for a century,

and of an advertisement calling upon his descendants to apply for

the sum of £10,000, alleged to be lying for them at the Bank of

England, are altogether un-founded. No such annuity has been

left, no such sum has accrued, and no such advertisement has

appeared. |

|

p.111 |

Boswell's price had been £16,300, and he undertook to

do the work in fifteen months. |

|

p.112 |

Description of Perry's work by S. Downing, C.E., in

Practical Mechanics' Journal, May, 1864. |

|

p.114 |

It has recently been proposed to convert the lake

into extensive docks, connected with London by the Tilbury Railway;

and a Company has been formed for the purpose of carrying out the

enterprise. |

|

p.115 |

The banks themselves are from 17 to 25 feet high in

the neighbourhood of Dagenham, and from 25to 30 feet wide at the

base. The marks of the old breach are still easily traceable. |

|

p.118-1 |

A fine statue by Colin Melbourne of the great man

overlooking the junction of the Caldon Canal with the Trent and

Mersey Canal. The statue was made in 1990. |

|

p.118-2 |

For a full account of Old Roads and Travelling in

England, we must refer the reader to 'Lives of the Engineers,' vol.

i. pp. 154-275.

Ed.―I don't have the full edition of

Lives of the Engineers to which Smiles here refers. What are

reproduced on this website are a number of the volumes sold

individually as "popular" and inexpensive editions. However, I

guess that Smiles is probably referring to the text that forms

the first chapters of the 'popular' edition dealing with

Thomas Telford and the History of Roads. |

|

p.121-1 |

Lansdowne MS. cvii. art. 73. |

|

p.121-2 |

The Lansdowne MS. xxxi., art. 74, sets forth certain

"Reasons against the proceedings of John Trew in the works of Dover

Haven, 1581." It appears from Lysons's History of Dover, that

Trew was engaged as harbour-engineer at ten shillings a-day wages;

but the corporation, thinking that he was inclined to protract the

work on which he was engaged, summarily dismissed him. This is

the last that we hear of John Trew. |

|

p.122 |

'England's Improvement by Sea and Land.' London,

1677. |

|

p.125 |

Ed.—the River Weaver is a river in West

Cheshire that is navigable in its lower reaches. Its most

notable engineering feature is the Anderton Boat Lift (1875), near

Northwich, which links the Weaver with the Trent and Mersey Canal,

some 50 feet (15 m) above it.

In 1720 the first Act of Parliament to authorise improvements to the

river was obtained—the work was completed in 1732. The river

had been improved by dredging and the construction of a series of

cuts, with locks and weirs to manage the drop of around 50 feet (15

m) over the 20 miles (32 km) between Winsford and the River Mersey.

Barges of up to 40 tons could reach Winsford, and boats called

'Weaver Flats' were the predominant vessels. These either

sailed up the river, or were bow-hauled by teams of men.

Further improvements over the years led to the river being

accessible by coastal craft of up to 1,000 tons. |

|

p.128 |

The site of the Croft is very elevated, and commands

an extensive view as far as Topley Pike, between Bakewell and

Buxton, at the top of what is called the Long Hill. Topley

Pike is behind the spectator in looking at the Croft in the above

aspect. The rising ground behind the ash tree is called

Wormhill Common, though now enclosed. The old road from Buxton

to Tides-well skirts the front of the rising ground. |

|

p.129 |

Kippis's 'Biographia Britannica,' Art. Brindley. |

|

p.130 |

Brindley's father seems afterwards to have somewhat

recovered himself; for we find him, in 1729, purchasing an undivided

share of a small estate at Lowe Hill, within a mile of Leek, in

Staffordshire, where he had before gone to settle; and he contrived

to realise the remaining portion before his death, and to leave it

to his son James. None of the Brindley family remained at

Wormhill, and the name has disappeared in the district. |

|

p.139 |

In the possession of Joseph Mayer, Esq., of

Liverpool, who has kindly permitted the author to inspect the whole

of his valuable manuscripts relating to Brindley, so curiously

illustrative of his start in life as a working and consulting

Engineer. |

|

p.143 |

The low remuneration paid for skilled labour of the

same sort long before Brindley's time is worthy of passing notice.

In 1544 John of Padua was paid only two shillings a-day as "devizour

of His Majestic's works," in other words as Royal architect.

Still later, Ingo Jones was paid only eight shillings and fourpence

a-day as architect and surveyor of the Whitehall Banqueting House,

and forty-six pounds a-year for house-rent, clerks, and incidental

expenses; whilst Nicholas Stowe, the master mason, was allowed but

four and tenpence a-day. When the Duchess of Marlborough was

afterwards engaged in resisting the claims of one of her Blenheim

surveyors, she told him indignantly "that Sir Christopher Wren,

while employed upon Saint Paul's, was content to be dragged up to

the top of the building three times a-week in a basket, at the great

hazard of his life, for only £200 a-year"—the actual amount of his

salary as architect of that magnificent Cathedral. Brindley,

however, fared worse still, and for a long time does not seem to

have risen above mere mechanic's pay, even whilst engaged in

constructing the celebrated canal for the Duke the of Bridgewater,

which laid the foundation of so many gigantic fortunes. |

|

p.147 |

'History of the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent.'

By John Ward. 1853. p.164. |

|

p.151-1 |

We find the following memorandum in Brindley's

pocket-book, relating to the expense of working the engine in the

year 1760:—

|

Miss Clare Maria Broads

fire engine

at fenian vivian. |

|

First yeer's work and repare night and day

|

£164 |

|

Do. torn back |

025 |

|

Due for te

first yeer |

139 |

|

Due for the second yeer. |

102 |

|

|

p.151-2 |

He describes it as "A Fire-Engine for Drawing Water

out of Dunes, or for Draining of Lands, or for Supplying of Cityes,

Townes, or Gardens with Water, or which may be applicable to many

other great and usefull Purposes, in a better and more effectual

Manner than any Engine or Machine that hath hitherto been made or

used for the like Purpose."—'Specifications of Patents,' No. 730. |

|

p.152 |

Stuart's 'Anecdotes of Steam-Engines,' p. 626. |

|

p.154 |

Ed.—The Sankey Canal — also known as the

Sankey Brook Navigation and the St Helens Canal — connects St Helens

with the River Mersey. The canal was built principally to transport

coal from the Lancashire Coalfields to the growing chemical

industries of Liverpool, though iron ore and corn were also

important commodities. Its immediate commercial success —

followed soon after by that of the Bridgewater Canal — led to the

'canal building mania'.

When opened in 1757, the Canal ran along the valley of the Sankey

Brook from the point where the brook joined the River Mersey, to a

location to the north west of St Helens. Extensions were later

constructed at the Mersey end of the canal, first to Fiddlers Ferry

and then to Widnes, while at the northern end, it was extended into

what became the centre of St. Helens. In common with most

British canals, the Sankey went into decline with the coming of the

railways and it was gradually abandoned between 1931 and 1963.

In more recent years it has been the subject of partial restoration

with ambitious plans to restore the Canal and extend it to join the

main canal system via the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. |

|

p.156-1 |

See Appendix, Grand Canal of Languedoc, and its

execution by Riquet de Bonrepos. |

|

p.156-2 |

'Essays in History, Biography, Geography,

Engineering,' &c. By the late Earl of Ellesmere. London, 1858.

p.226, |

|

p.157 |

'Walpole to Mann,' Feb. 27th, 1752. |

|

p.158 |

Chalmers, in his 'Biographical Dictionary,' vol.

xiii., 94, gives another account of the rumoured cause of the Duke's

subsequent antipathy to women; but the above statement of the late

Earl of Ellesmere, confirmed as it is by certain passages in

Walpole's Letters, is more likely to be the correct one. |

|

p.160 |

Aikin's 'Description of the Country from Thirty to

Forty Miles round Manchester.' London, 1795. |

|

p.162 |

Thomas Walker: The Original, No, xi. Article

entitled "Change in Commerce." |

|

p.163 |

March 3rd, 1760, the Flying Machine was started, and

advertised to perform the journey, "if God permit," in three days,

by John Hanforth Matthew Howe, Samuel Granville, and William

Richardson. Fare inside, £2. 5s.; outside, half-price. |

|

p.164 |

This "load" is still used as a measure of weight,

though the practice of carrying all sorts of commodities on horses'

backs, in which it originated, has long since ceased. |

|

p.170 |

Ed.—it was in this building that Francis

Egerton, the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, James Brindley and John

Gilbert planned the Bridgewater Canal and supervised its building. |

|

p.173-1 |

We have heard the name of Smeaton mentioned as that

of the engineer consulted on the occasion, but are unable to speak

with certainty on the point. Excepting Smeaton, however, there

was then no other engineer in the country of recognised eminence in

the profession. |

|

p.173-2 |

Ed.—the Barton Swing Aqueduct replaced

Brindley's earlier stone aqueduct (1761) across the River Irwell.

The construction of the Manchester Ship Canal in the 1890s

necessitated Brindley's aqueduct being replaced to permit

ocean-going ships to pass the Bridgewater Canal. The Barton

Swing Aqueduct pivots to give clearance to Manchester Ship Canal

traffic, and when aligned permits Bridgewater Canal traffic to cross

over the top of the Ship Canal. The Swing Aqueduct, a Grade II

listed building, was designed by Sir Edward Leader Williams and

built by Andrew Handyside of Derby. It opened in 1894 and

remains in regular use. |

|

p.174-1 |

The process of puddling is of considerable importance

in canal engineering. Puddle is formed by a mixture of

well-tempered clay and sand reduced to a semi-fluid state, and

rendered impervious to water by manual labour, as by working and

chopping it about with spades. It is usually applied in three

or more strata to a depth or thickness of about three feet: and care

is taken at each operation so to work the new layer of puddling

stuff as to unite it with the stratum immediately beneath.

Over the top course a layer of common soil is usually laid. It

is only by the careful employment of puddling that the filtration of

the water of canals into the neighbouring lower lands through which

they pass can be effectually prevented. |

|

p.174-2 |

Ed.—the photograph shows "puddling" in

progress during the restoration of a derelict part of the Montgomery

Canal in Shropshire. Puddle clay has been applied to the side

of the canal, while a large 'plug' of puddle temporarily damks the

end section. The puddle is laid about 25 cm thick at the sides

and nearly a metre thick at the bottom of a canal, built up in

layers. Puddle has to be kept wet in order to remain

waterproof so it is important for canals to be kept filled with

water. |

|

p.177 |

'Six Months' Tour through the North of England,' vol.

iii., p. 258. Ed. 1770. |

|

p.178 |

The barges are narrow and long, each conveying about

ten tons of coal. They are drawn along the tunnels by means of

staples fastened to the sides. When they are empty, and

consequently higher in the water, they are so near the roof that the

bargemen, lying on their backs, can propel them with their feet. |

|

p.181 |

A writer in the 'St. James's Chronicle,' under date

the 30th of September, 1763 gives the following account of this

apparatus, long since removed:—"At the mouth of the cavern is

erected a water-bellows, being the body of a tree, forming a hollow

cylinder, standing upright. Upon this a wooden basin is fixed, in

the form of a funnel, which receives a current of water from the

higher ground. This water falls into the cylinder, and issues

out at the bottom of it, but at the same time carries a quantity of

air with it, which is received into the pipes and forced to the

innermost recesses of the coal-pits, where it issues out as if from

a pair of bellows, and rarefies the body of thick air, which would

otherwise prevent the workmen from subsisting on the spot where the

coals are dug." |

|

p.182-1 |

'Six Months' Tour,' vol, iii., p. 270-1. Mr.

Hughes, C.E., says of this discovery: "The lime thus made would

appear to be the first cement of which we have any knowledge in this

country; since the calcareous marl here spoken of would probably

produce, when burnt, a lime of strong hydraulic properties." |

|

p.182-2 |

This story was first set on foot, we believe, by the

Earl of Bridgewater, in his singularly incoherent publication

entitled, 'A Letter to the Parisians and the French Nation upon

Inland Navigation, containing a defence of the public character of

His Grace Francis Egerton, late Duke of Bridgewater. By the

Hon. Francis Henry Egerton.' The first part of this curious

book (published at Paris was dated "Hotel Egerton, Paris, 21st Dec.,

1818;" the second part was published two years later; and a third

part, consisting entirely of a note about Hebrew interpretations,

was published subsequently. He had in the mean time become

Earl of Bridgewater, in October, 1823, having formerly been

prebendary of Durham and rector of Whit- church in Shropshire.

The late Earl of Ellesmere, in his 'Essays on History, Biography,'

&c., says of this nobleman that "he died at Paris in the odour of

eccentricity." But this is a mild description of his lordship,

who had at least a dozen distinct crazes—about canals, the Jews,

punctuation, the wonderful merits of the Egertons, the proper

translation of Hebrew, the ancient languages generally, but more

especially about prophecy and poodle-dogs. When he drove along

the Boulevards in Paris, nothing could be seen of his lordship for

poodle-dogs looking out of the carriage-windows. The poodles

sat at table with him at dinner, each being waited on by a special

valet. The most creditable thing the Earl did was to leave the

sum of £12,000. to the British Museum, and £8,000 to meritorious

literary men for writing the well-known 'Bridgewater Treatises.'

He died in February, 1829. |

|

p.183 |

Ed.—Alan Murray-Rust, who took this photograph,

writes thus: "To the right is the branch up into the Delph for the

mine workings which were the main reason for the building of the

Bridgewater Canal. The line to Leigh continues to the left.

The red colour of the water is due to the minerals leaching out of

the old mine workings. Straight ahead is Worsley Packet House.

The helmsman of the narrowboat has to make a hard left turn and hope

that there is nothing coming the other way through the bridge."

The timber-framed building in the foreground is the

Worsley Packet House. Swift passenger boats ("packets") to

Manchester used to depart from its steps. |

|

p.184 |

It would almost seem as if the extension of the canal

to the Mersey had formed part of the Duke's original plan; for

Brindley was engaged in making a survey from Longford to Dunham in

the autumn of the preceding year, as appears from the following

account, preserved at the Bridgewater Canal Office at Manchester, of

his expenses in making the survey:—

Expenses in Surveying from Longford

Bridge to Dunham.

|

Octr 21st 1760.

Spent at Stretford |

0 |

6 |

|

At Altringham all Night |

6 |

0 |

|

Gave the Men to Drink that

assisted |

1 |

0 |

|

22nd

More at Altringham |

2 |

6 |

| |

―――― |

|

|

10 |

0 |

|

Pd Mr. Brinley this." |

|

|

p.188-1 |

Progress of Liverpool.

|

Years |

Vessels |

Tonnage

entered |

Duties Paid |

|

1701 |

102 |

8,619 |

― |

|

1760 |

1,245 |

― |

£2,330 |

|

1800 |

4,746 |

450,060 |

£23,379 |

|

1858 |

21,352 |

4,441,943 |

£347,889 |

|

|

p.188-2 |

Ed.—with the advent of containerisation in the

1970s, Liverpool's elderly dock system fell into sharp decline.

Although most have now been abandoned as cargo-handling facilities

and the docks cease to be a major local employer, the Royal Seaforth

Container Terminal (opened in 1972), backed by the modernisation of

some of the older docks, permits Liverpool today to handle more

cargo than in its heyday as a seaport. |

|

p.188-3 |

Mr. Baines says: "Carriages were then very rare, and

it is mentioned as a singular fact that at the period in question

(1750) there was but one gentleman's carriage in the town of

Liverpool, and that carriage was kept by a lady of the name of

Clayton."—'History of Lancashire,' vol. iv., p.90. |

|

p.195 |

Search has been made at the Bridgewater Estate

Offices at Manchester, and in the archives of the Houses of

Parliament, but no copy can be found. It is probable that the

Parliamentary papers connected with this application to Parliament

were destroyed by the fire which consumed so many similar documents

about twenty-five years ago. |

|

p.196-1 |

Stated by Mr. Hughes, in his 'Memoir of Brindley,' as

having been communicated to him by James Loch, Esq., M.P., formerly

agent for the Duke's Trustees. |

|

p.196-2 |

'Memoir of Brindley,' by S. Hughes, C.E., in 'Weale's

Papers on Civil Engineering.' |

|

p.197 |

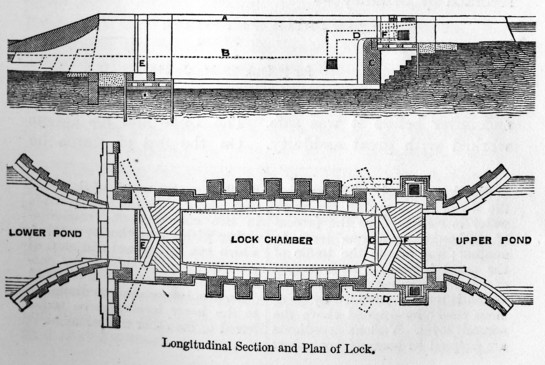

As the reader may possibly desire information on the

same point, we may here briefly explain the nature of a Canal Lock.

It is employed as a means of carrying navigation through an uneven

country, and raising the boats from one water level to another, or

vice versa. The lock is a chamber formed of masonry, occupying

the bed of the canal where the difference of level is to be

overcome. It is provided with two pairs of gates, one at each

end; and the chamber is so contrived that the level of the water

which it contains may be made to coincide with either the higher

level above, or the lower level below it. The following

diagrams will explain the form and construction of the lock.

A represents what is called the upper pond, B the

lower, C is the left wall, and DD side culverts.

When the gates at the lower end of the chamber (E) are

opened, and those at the upper end (F) are closed, the water

in the chamber will stand at the lower level of the canal; but when

the lower gates are closed, and the upper gates are opened, the

water will naturally coincide with that in the upper part of the

canal. In the first case, a boat may be floated into the lock

from the lower part, and then, if the lower gates be closed and

water is admitted from the upper level, the canal-boat is raised, by

the depth of water thus added to the lock, to the upper level, and

on the complete opening of the gates it is thus floated onward.

By reversing the process, it will readily be understood how the boat

may, in like manner, be lowered from the higher to the lower level.

The greater the lift or the lowering, the more water is consumed in

the process of exchange from one level to another; and where the

traffic of the canal is great, a large supply of water is required

to carry it on, which is usually provided by capacious reservoirs

situated above the summit level. Various expedients are

adopted for economising water: thus, when the width of the canal

will admit of it, the lock is made in two compartments,

communicating with each other by a valve, which can be opened and

shut at pleasure; and by this means one-half of the water which it

would otherwise be necessary to discharge to the lower level may be

transferred to the other compartment. |

|

|

|

p.200 |

The following statement of the lengths of the

different portions of the Duke's canal, including those originally

executed, is from the map published by Brindley in 1769:—

|

|

Miles |

furl. |

chains. |

|

|

From Worsley to Longford Bridge |

6 |

0 |

0 |

Level |

|

… Longford Bridge to Manchester |

4 |

2 |

0 |

… |

|

… Longford Bridge to Preston Brook |

19 |

0 |

0 |

… |

|

… Preston Brook to upper part of Runcorn |

4 |

4 |

0 |

… |

|

… Upper part of Runcorn to the Mersey |

0 |

5 |

7 |

79 feet fall |

|

|

p.201 |

Ed.—the former Junction of the Bridgewater

Canal with Mersey. Construction of the flight of 10 locks to

the River Mersey began in 1772 and was completed in 1776. Such

was the great expansion of waterborne merchandise passing up and

down them that it was necessary to build a second line in 1826.

For over 160 years flats and narrow boats locked up and down them in

great numbers. The second line of locks was abandoned in the mid

sixties, but the original line of the former flight of locks was

preserved when the new building shown took place. |

|

p.208 |

The following bill is preserved amongst the

Bridgewater Canal papers. Simcox was a skilled mechanic, and

acted as foreman of the carpenters:—

His Grace the Duke of Bridgewater to Saml Simcox.

|

|

£. |

s. |

d. |

|

23 Marh 1760 To 12 days work

at 21d per |

1 |

01 |

0 |

|

23 Augt To 6 days more do at

do |

0 |

10 |

6 |

|

6 Sepr To 8 days more do at d° |

0 |

14 |

0 |

|

|

―――――― |

|

|

2 |

05 |

6 |

1 Novr 1760. Recd the Contents

above by the Hands of John Gilbert

for the Use of Saml Simcox.

Pd

JAMES BRINDLEY."

The wages of what was called a "right-hand man" at

that time were from 14d. to 16d. a day, and of a "left-hand man "

from 1s. to 14d. |

|

p.209 |

The Earl of Bridgewater, in his rambling 'Letter to

the Parisians,' above referred to, alleges that the quarrel

originated in Gilbert's horse breaking into the field where

Brindley's mare was grazing, and doing her such injury that the

engineer was for a time prevented using the animal in the pursuit of

his business. The mare was a great favourite of Brindley's,

and he is said to have taken the thing very much to heart. The

Earl alleges that Brindley was under the impression Gilbert had

contrived the trick out of spite. |

|

p.211 |

R. Rawlinson. Esq., C.E., Engineer to the Bridgewater

Canal. |

|

p.213 |

Mr. Bennet Woodcroft, of the Patent Office, writes us

as follows with reference to Earnshaw's alleged invention of a

spinning machine:—"The fact really is, that the machine in question

was invented by John Kay of Bury; and when, in 1753, a mob broke

into Kay's house, and completely gutted it, the model of the

spinning machine was saved by Earnshaw, who subsequently destroyed

it." |

|

p.214-1 |

St. James's Chronicle, July 1st, 1765. |

|

p.214-2 |

'A History of Inland Navigations. Particularly

those of the Duke of Bridgewater in Lancashire and Cheshire.'

2nd Ed., p. 39. |

|

p.214-3 |

Ed.—Waterloo Bridge now marks the end of the

Runcorn Arm of the Bridgewater canal, which once continued via a

flight of locks to the River Mersey (see

p.201). The route was

blocked by the building of the A533 access road to the

Runcorn-Widnes bridge. The middle arch of the bridge gave

access to a dry dock. |

|

p.215 |

This bold scheme, so earnestly advocated by Brindley,

was thus noticed by a Liverpool paper of the time:—"On Monday last,

Mr. Brindley waited upon several of the principal gentlemen of this

town and others at Runcorn, in order to ascertain the expense that

may attend the building of a bridge over the river Mersey at the

latter place, which is estimated at a sum inferior to the advantages

that must arise both to the counties of Lancaster and Chester from a

communication of this sort.—Williamson's 'Liverpool Advertiser,'

July 19th, 1768. |

|

p.216 |

Ed.—"This [Duke's Dock] was constructed by the

late Duke of Bridgewater, for the purpose of loading and discharging

flats belonging to him. It is supplied with an elegant and

commodious range of warehouses, arched in the centre, so that

vessels can be placed under the very rooms of the building, and by

means of hatch-ways the cargoes are loaded and unloaded without

being exposed to the weather. This dock belongs to the

executors of the late Duke of Bridgewater." (From 'Picture of

Liverpool: Stranger's Guide' written in 1834.) By

1960, virtually all activity on the Duke's Dock site had ceased, the

buildings were demolished piecemeal between then and 1984, and the

river entrance was closed (but markings remain on the dock wall).

The Dock is relatively narrow and appears more like a canal than a

dock. What remains is Grade II. listed. |

|

p.219 |

There is now to be seen at Worsley, in the hands of a

private person, a promissory note given by the Duke, bearing

interest, for as low a sum as five pounds. Amongst the persons

known to be lenders of money, to whom the Duke applied at the time,

was Mr. C. Smith, a merchant at Rochdale; but he would not lend a

farthing, believing the Duke to be engaged in a perfectly ruinous

undertaking. |

|

p.221 |

The Earl of Ellesmere's ' Essays on History,

Biography,' &c., p. 236. |

|

p.227 |

We regret to have to add that Brindley's widow

(afterwards the wife of Mr. Williamson, of Longport) in vain

petitioned the Duke and his representatives, as well as the above

Earl of Bridgewater, for payment of a balance said to have been due

to Brindley for services, at the time of the engineer's death.

In her letter to Robert Bradshaw, M.P., dated the 2nd May, 1803,

Mrs. Williamson says: "It will doubtless appear to you extraordinary

that so very late an application should now be made . . . but I must

beg leave to state that repeated applications were made by me (after

Mr. Brindley's sudden and unexpected death) to the late Mr. Thomas

Gilbert and also to his brother, but without any other effect than

that of constant promises to lay the matter before His Grace and I

conceive it owing to this channel of application that no settling

ever took place. A letter was also written to His Grace on

this subject so late as the year 1801, but no answer was received.

From the year 1765 to 1772, Mr. Brindley received no money on

account of his salary. At that time he was frequently in very

great want, and made application to the Duke, whose answer (to use

the Duke's expression) was, 'I am much more distressed for money

than you; however, as soon as I can recover myself, your services

shall not go unrewarded.' In consequence of this, Mr. Brindley

was under the necessity of borrowing several sums to make good

engagements he was then under to various canal companies. In

the year 1774, two years after Mr. Brindley's death, the late Mr.

John Gilbert paid my brother, Mr. Henshall, the trifling sum of £100

on account of Mr. Brindley's time, which is all that has been

received. I beg leave to suggest how small and inadequate a

return this is for his services during a period of seven years.

Mr. B.'s travelling expenses on His Grace's account during that time

were considerable, towards which, when he had not sufficient money

to carry him the whole journey, he now and then received a small

sum. How far his plans and undertakings have been beneficial

to His Grace's interest is well known." |

|

p.228 |

When the Duke had put on the boats and established

the service, he offered to let them for £60 a year; but not being

able to find any person to take them at that price, he was under the

necessity of conducting the service himself, by means of an agent.

In the course of a short time the boats were found to yield a clear

profit of £1,600 a year. |

|

p.229 |

A similar story is told of him at Worsley. A

boy had been fetching some coal from the mouth of the tunnel, and

having rested his load could not get it cleverly on his back again.

Seeing but not knowing the Duke, he called out, "Here, felly, gie us

a hoist up." The Duke asked the boy a number of questions

before helping him up with the sack; but when the youth felt it safe

for carrying, he expressed his acknowledgments by observing "Wal,

thou's a big chap, but thou's a lazy un!" |

|

p.233-1 |

The treatise which Fulton afterwards published,

entitled 'A Treatise on Canal Navigation, exhibiting the numerous

advantages to be derived from small Canals, &c., with a description

of the machinery for facilitating conveyance by water through the

most mountainous countries, independent of Locks and Aqueducts,'

(London, 1796,) is well known amongst engineers. |

|

p.233-2 |

Lord Ellesmere's 'Essays,' p.241. |

|

p.236 |

"His purchases from Italy and Holland were judicious

and important, and, finally, the distractions of France forcing the

treasures of the Orleans Gallery into this country, he became a

principal in the fortunate speculation of its purchase."—'Essays on

History, Biography,' &c. |

|

p.237 |

Ed.—in company with other family members, the

memorial to the Duke of Bridgewater's is in the Bridgewater Chapel

of the parish church of St Peter and St Paul, Little Gaddesden,

Hertfordshire (OS Ref: SP998138). The plaque, which is on the

chapel's South wall, reads:

|

TO THE MEMORY

OF

FRANCIS

DUKE AND EARL OF BRIDGEWATER,

MARQUIS OF AND VISCOUNT BRACKLEY

AND BARON OF ELLESMERE.

HE WAS BORN 21ST MAY 1736,

AND HE DIED 6TH MARCH 1803.

HE WILL EVER BE MEMORABLE

AMONG "THOSE WHO WERE

HONOURED IN THEIR GENERATIONS,

AND WERE THE GLORY OF THEIR TIMES."

IMPULIT ILLE RATES UBI DUXIT ARATRA COLONUS

H.M.P.

J. W. COMES DE BRIDGEWATER. |

The eminent art historian Sir Nicholas Pevsner's

view was that visitors to the church would find its monuments

(of which there are many) more memorable than its architecture.

|

|

p.238-1 |

'History of Inland Navigation,' p.76. |

|

p.238-2 |

The Duke at first employed mules in hauling the

canal-boats, because of the greater endurance and freedom from

disease of those animals, and also because they could eat almost any

description of provender. The Duke's breed of mules was for a

long time the finest that had been known in England. The

popular impression in Manchester is, that the Duke's Acts of

Parliament authorising the construction of his canals, forbade the

use of horses, in order that men might be employed; and that the

Duke consequently dodged the provisions of the Acts by employing

mules. But this is not the case, there being no clause in any

of them prohibiting the use of horses. |

|

p.239-1 |

There is even a tradition surviving at Worsley, that

"the Duke" rides through the village once in every year at midnight,

drawn by six coal-black horses! |

|

p.239-2 |

The cotton trade was not of much importance at first,

though it rapidly increased when the steam-engine and spinning-jenny

had become generally adopted. It may be interesting to know

that sixty years since it was considered satisfactory if one

cotton-flat a day reached Manchester from Liverpool. In the

Duke's time the flats always "cast anchor" on their way, or at least

laid up for the night, at six o'clock precisely, starting again at

six o'clock on the following morning. |

|

p.243 |

Recent "poor-lays" exhibit a very different result

from what they did in former years. In 1860-1 the poor-rate

levied is Chorlton-upon-Medlock yielded (at 2s. 10d. in the pound)

£18,798; the property in the township being of the rateable value of

£145,844. |

|

p.244-1 |

De Quincey's 'Autobiographic Sketches,' pp. 34, 48. |

|

p.244-2 |

The corner of Irwell Street, Salford, as recently as

1828, was occupied by an old canal "flat," tenanted by an eccentric

character, after whom it was designated "Bannister's Ship."

Opposite it was a row of cottages with gardens in front.

Oldfield and Ordsall Lanes were country roads, and the streets

adjacent to them were not yet in existence. |

|

p.245 |

The growth of Manchester, and the sister borough of

Salford, will be more readily appreciated, perhaps, by a glance at

the population at different periods than by any other illustration:—

Population in 1774.

1801. 1821.

1861.

41,032 81,020

187,031 460,028. |

|

p.246 |

On the subject of watchmen it may be mentioned that

the first watchman was appointed for Chorlton-on-Medlock in 1814.

In 1832 an Act was obtained for improving and regulating that

township, and so recently was 1833 it was first lighted with gas.

The Police Act for the Township of Hulme was obtained in 1834. |

|

p.250 |

In a curious book published in 1766, by Richard

Whitworth, of Balcham Grange, Staffordshire, afterwards Sir Richard

Whitworth, member for Stafford, entitled 'The Advantages of Inland

Navigation,' be points to the various kinds of traffic that might be

expected to come upon the canal then proposed by him, and amongst

other items he enumerates the following:—"There are three

pot-waggons go from Newcastle and Burslem weekly, through Eccleshall

and Newport to Bridgenorth, and carry about eight tons of pot-ware

every week, at £3 per ton. The same waggons load back with ten

tons of close goods, consisting of white clay, grocery, and iron, at

the same price, delivered on their road to Newcastle. Large

quantities of pot-ware are conveyed on horses' backs from Burslem

and Newcastle to Bridgenorth and Bewdley for exportation—about one

hundred tons yearly, at £2 10s. per ton. Two broad-wheel

waggons (exclusive of 150 pack-horses) go from Manchester through

Stafford weekly, and may be computed to carry 312 tons of cloth and

Manchester wares in the year, at £3 10s. per ton. The great

salt-trade that is carried on at Northwich may be computed to send

600 tons yearly along this canal, together with Nantwich 400,

chiefly carried now on horses' backs, at 10s. per ton on a medium." |

|

p.252-1 |

Young's 'Six Months' Tour.' Ed. 1770.

Vol. iii., p.317. |

|

p.252-2 |

History of Birmingham.' Ed. 1836, p. 24. |

|

p.253 |

The Papers of Mr. Llewellynn Jewitt, F.S.A., on

'Wedgewood and Etruria,' published in the Art Journal, 1861,

contain many interesting particulars relating to the life and

labours of Wedgwood, and are well worthy of perusal. |

|

p.254 |

'Wedgwood;' an Address delivered at Burslem, Oct. 26,

1863. By the Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone, Chancellor of the

Exchequer. London: Murray. |

|

p.255 |

The Ivy House, in which Wedgwood began business on

his own account, is the cottage shown on the right-hand of the

engraving. The other house is the old "Turk's Head." |

|

p.256 |

Faujas Saint Fond, in his 'Travels in England,' thus

writes respecting Wedgwood's ware:—"Its excellent workmanship, its

solidity, the advantage which it possesses of standing the action of

fire, its fine glaze, impenetrable to acids, the beauty,

convenience, and variety of its forms, and its moderate price, have

created a commerce so active, and so universal, that in travelling

from Paris to St. Petersburg, from Amsterdam to the farthest point

of Sweden, from Dunkirk to the southern extremity of France, one is

served at every inn from English earthenware. The same fine

article adorns the tables of Spain, Portugal, and Italy; and it

provides the cargoes of ships to the Indies, the West Indies, and

America." |

|

p.258 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "This statue of

Josiah Wedgwood—whose name will be forever associated with the

Potteries—stands outside the North Stafford Hotel in Winton Square,

opposite the station. The artist was by Edward Davis and it

was erected in 1863." |

|

p.260 |

Wedgwood even entered the lists as a pamphleteer in

aid of the Grand Trunk project, and, in 1765, he and his partner,

Mr. Bentley, formerly of Liverpool, drew up a very able statement,

showing the advantages likely to be derived from the construction of

the proposed canal, under the title of 'A View of the Advantages of

Inland Navigation, with a plan of a Navigable Canal intended for a

communication between the ports of Liverpool and Hull.' It

pointed out in glowing language the advantages to be derived from

opening up the internal communications of a country by means of

roads, canals, &c.; and showed how the comfort and even the

necessity of all classes must be so much better provided for by a

reduction in the cost of carriage of useful and necessary

commodities. |

|

p.261 |

The Advantages of Inland Navigation,' by R.

Whitworth. 1766. |

|

p.263 |

In one of the many angry pamphlets published at the

time, the 'Supplement to a pamphlet entitled Seasonable

Considerations on a Navigable Canal intended to be cut from the

Trent to the Mersey,' &c., the following passage occurs: "When our

all is at stake, these gentlemen [the promoters of the Grand Trunk

Canal] must not be surprised at bold truths. We conceive more

favourably of their understanding than of their motive; we cannot

suspect them of entertaining the chimerical idea of cutting through

Hare Castle! We rather believe that they are desirous of

cutting their canal at both ends, and of leaving the middle for the

project of a future day. Are these projectors jealous of their

honour? Let them adopt a clause (which reason and justice

strongly enforce) to restrain them from meddling with either end

till they have finished the [great trunk]. This, and this

alone, will shield them from suspicion." |

|

p.266 |

Ed.—the photographers writes thus:

(i) "Designed by James Brindley, this aqueduct carries the Trent and

Mersey Canal [formerly the Grand Trunk Canal] cross the River Dove.

Because only shallow arches could be built to allow for the depth of

the canal, the length of the aqueduct had to provide for sufficient

arches to allow for high flows during periods of flood."

(ii) "The Croxton Aqueduct carries the Trent and Mersey Canal over

the River Dane. Its narrow width limits the size of boats that can

use the canal." |

|

p.267 |

Brindley's tunnel had only space for a narrow

canal-boat to pass through, and it was propelled by the tedious and

laborious process of what is called "legging." It still

continues to be worked in the same way, while horses haul the boats

through the whole length of Telford's wider tunnel. The men

who "leg" the boat, literally kick it along from one end to the

other. They lie on their backs on the boat-cloths, with their

shoulders resting against some package, and propel it along by means

of their feet pressing against the top or sides of the tunnel. |

|

p.268-1 |

The smaller opening into the hill on the right-hand

of the view is Brindley's tunnel; that on the left is Telford's,

executed some forty years since. Harecastle church and village

occupy the ground over the tunnel entrances. |

|

p.268-2 |

'Seasonable Considerations,' &c.; Canal pamphlet

dated 1766. |

|

p.269 |

Ed.—Harecastle Tunnel is a canal tunnel on the

Trent and Mersey Canal. It is made up of 2 separate, parallel,

tunnels described as the 'Brindley' (2880 yards) and the later

'Telford' (2926 yards) after the engineers that constructed them.

The Brindley tunnel was constructed by James Brindley between 1770

and 1777. Brindley died during its construction. At the

time of its construction it was twice the length of any other tunnel

in the world.

Today only the Telford tunnel is navigable. The tunnel is only

wide enough to carry traffic in one direction at a time and boats

are sent through in groups, alternating northbound and southbound.

Ventilation is handled by a large fan at the south portal. |

|

p.272 |

The following comparison of the rates per ton at

which goods were conveyed by land-carriage before the opening of the

Grand Trunk Canal, and those at which they were subsequently carried

by it, will show how great was the advantage conferred on the

country by the introduction of navigable canals:—"The cost of

carrying a ton of goods from Liverpool to Etruria, the centre of the

Staffordshire Potteries, by land-carriage, was 50s.; the Trent and

Mersey reduced it to 13s. 4d. The land-carriage from Liverpool

to Wolverhampton was £5 a ton; the canal reduced it to £1 5s.

The land-carriage from Liverpool to Birmingham, and also to

Stourport, was £5 a ton; the canal reduced both to £1 10s. . . . .

Thus the cost of inland transport was reduced, on the average, to

about one-fourth of the rate paid previous to the introduction of

canal navigation. The advantages were enormous: wheat, for

example, which formerly could not be conveyed a hundred miles, from

corn-growing districts to the large towns and manufacturing

districts, for less than 20s. a quarter, could be conveyed for about

5s. a quarter. These facts show how great was the service

conferred on the country by Brindley and the Duke of Bridgewater."—Baines's

'History of the Commerce and Town of Liverpool.' |

|

p.273-1 |

Ed.—the Dudson Pottery, Hanley, is a grade II

listed building. It had only one "bottle kiln". The

factory, founded in 1800, eventually closed in 1980 when all

production moved to Burslem and Tunstall. The Hope Street

factory, shown here, is now open as part of a museum devoted to 200

years of the Dudson family pottery. |

|

p.273-2 |

The population of the same district in 1861 was found

to be upwards of 120,000. |

|

p.276-1 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "Beyond the

bridge is Stourton Junction. Turn right to Stourbridge,

Netherton Tunnel and Birmingham; go straight on for Wolverhampton,

and the Potteries and the north (via the Trent and Mersey canal).

The tow paths in this area have been well restored and cycling is

encouraged." |

|

p.276-2 |

Ed.—the photographer writes: "also known as

Bishop Street Basin, this facility was opened in 1769 at the

extremity of the Coventry Canal. At one time it would have

been an industrial environment, seldom seen by anyone not involved

in the canal-carrying business, but it is now a pleasant location to

stroll round admiring the boats or visiting the retail outlets.

The statue depicts James Brindley, the canal's original engineer." |

|

p.277 |

The letter is so characteristic of Josiah Wedgwood

that we here insert it at length, as copied from the original in the

possession of Mr. Mayer of Liverpool:—

"Burslem, 12th July, 1769.

"Dear Sir,—I should have wrote to you about young Wilson, but

the multiplicity of branches you wrote me he was expected to learn,

made me despair of teaching him any. Pray give my compliments

to his father, and if he chooses to have his son to learn to be a

warehouseman and bookkeeper, which is quite sufficient and better

than more for any one person, I will learn him those in the best

manner; but, even then, Mr. Wilson must not expect him to be set on

the top of a ladder without setting his feet upon the lowermost

steps; and unless he will let the Boy pursue that method, I would

not be concerned with him on any account. I will not attempt

to teach him any more trades; it would injure the Boy, and do me no

good. If he has a mind his leisure time to amuse himself with

drawing I have no objection, and would encourage him in it, as an

innocent amusement, and what may be of use to him, but would not

make this a branch of his business. If the business I propose

is too humble for Mr. Wilson's son, I would not by any means have

him accept of it.

"Mr. Brindley desires you'll send 30 plans to each of the

undermentioned Gentlemen by the first Waggons, and let us know when

they are sent, as we shall advertise them in several of the Country

papers: Mr. Walker, of Oxford, Steward to D. of Marlbro'—you may

perhaps get them sent from Marlbro' house; Mr. Dudley,

Attorney-at-Law, Coventry; Mr. Richardson, Silversmith, in Chester;

Mr. Perry, Wolverhampton.

"We shall send you this week end, double salts, creams,

pott'y potts, table plates of all sorts, sallad dishes, covered do.,

pierced desert plates, &c. We cannot get Sadler to send us any

pierced desert ware, &c. Pay Addison 5 or 6 guineas.

"Yours, &c., J. W." |

|

p.278 |

Ed.—the Droitwich Canal

is a synthesis of two canals; the Droitwich Barge Canal and the

Droitwich Junction Canal. The Barge Canal, engineered by

Brindley, is a broad canal which opened in 1771 linking Droitwich

Spa to the River Severn at Hawford Mill, Claines. Like most of

Brindley's canals, it was a contour canal, following the contours as

much as possible, to reduce the number of embankments and cuttings

required. The Droitwich Junction Canal is a narrow canal,

opened in 1854, which linked Droitwich to the Worcester and

Birmingham Canal. Both were built to carry salt, and were abandoned

in 1939.

As with so many canals the coming of the railways spelt their

economic doom and an Act of Abandonment was passed in July 1939.

The last boat to use the Barge Canal went through in 1916. The

last boat to use the Junction Canal went through a few years later

in 1928. The canals are now the subject of a restoration plan. |

|

p.279 |

The following were the canals laid out and

principally executed by Brindley:—

|

|

Miles |

furl. |

chains |

|

The Duke's Canals Worsley to Manchester |

10 |

2 |

0 |

|

do. Longford Bridge to the Mersey below Runcorn |

24 |

1 |

7 |

|

Grand Trunk Canal Proper, from Wilden

Ferry to Preston

Brook |

88 |

7 |

9 |

|

Wolverhampton Canal |

46 |

4 |

0 |

|

Coventry |

36 |

7 |

8 |

|

Birmingham |

24 |

2 |

0 |

|

Droitwich |

5 |

4 |

9 |

|

Oxford |

82 |

7 |

3 |

|

Chesterfield |

46 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

p.280 |

'Memoir,' by Samuel Hughes, C. E. Weale's

'Quarterly Papers,' 1844. |

|

p.286 |

Ed.—Brindley married his young bride, Ann

Henshall, in 1765 and together they moved into Turnhurst Hall.

Brindley mixed with some of the finest minds in England during this

time as his friend Josiah Wedgwood introduced him to the eminent

physician and polymath Erasmus Darwin and other illustrious members

of the Lunar Circle. It was Erasmus Darwin who attended

Brindley at Turnhurst towards the end of his life and diagnosed his