|

JAMES BRINDLEY

AND

THE EARLY ENGINEERS.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY.

IT has taken the

labour and the skill of many generations of men to make England the

country that it now is; to reclaim and subdue its lands for purposes

of agriculture, to build its towns and supply them with water, to

render it easily accessible by means of roads, bridges, canals, and

railways, and to construct lighthouses, breakwaters, docks, and

harbours for the protection and accommodation of its commerce.

Those great works have been the result of the continuous industry of

the nation, and the men who have designed and executed them are

entitled to be regarded in a great measure as the founders of modern

England.

Engineering, like architecture, strikingly marks the several

stages which have occurred in the development of society, and throws

much curious light upon history. The ancient British

encampment, of which many specimens are still to be found on the

summits of hills, with occasional indications of human dwellings

within them in the circular hollows or pits over which huts once

stood,—the feudal castle perched upon its all but inaccessible rock,

provided with drawbridge and portcullis to secure its occupants

against sudden assault,—then the moated dwelling, situated in the

midst of the champaign country, indicating a growing, though as yet

but half-hearted confidence in the loyalty of neighbours,—and,

lastly, the modern mansion, with its drawing-room windows opening

level with the sward of the adjacent country,—all these are not more

striking indications of social progress at the different stages in

our history, than the reclamation and cultivation of lands won from

the sea, the making of roads and building of bridges, the supplying

of towns with water, and the construction of canals and railroads

for the ready conveyance of persons and merchandise throughout the

empire.

In England, as in all countries, men began with making

provision for food and shelter. The valleys and low-lying

grounds being mostly covered with dense forests, the naturally

cleared high lands, where timber would not grow, were doubtless

occupied by the first settlers. Tillage was not as yet

understood nor practised; the people subsisted by hunting, or upon

their herds of cattle, which found ample grazing among the hills of

Dartmoor, and on the grassy downs of Wiltshire and Sussex.

Numerous remains or traces of ancient dwellings have been found in

those districts, as at Bowhill in Sussex, along the skirts of

Dartmoor where the hills slope down to the watercourses, and on the

Wiltshire downs, where Old Sarum, Stonehenge and Avebury, mark the

earliest and most flourishing of the British settlements.

The art of reclaiming, embanking, and draining land, is

supposed to have been introduced by men from Belgium and Friesland,

who early landed in great numbers along the south-eastern coasts,

and made good their footing by the power of numbers, as well as

probably by their superior civilization. The lands from which

they came had been won by skill and industry from the sea and from

the fen; and when they swarmed over into England, they brought their

arts with them. The early settlement of Britain by the races

which at present occupy it, is usually spoken of as a series of

invasions and conquests; but it is probable that it was for the most

part effected by a system of colonization, such as is going forward

at this day in America, Australia, and New Zealand; and that the

immigrants from Friesland, Belgium, and Jutland, secured their

settlement by the spade far more than by the sword. Wherever

the new men came, they settled themselves down on their several bits

of land, which became their holdings; and they bent their backs over

the stubborn soil, watering it with their sweat; and delved, and

drained, and cultivated it, until it became fruitful. They

also spread themselves over the richer arable lands of the interior,

the older population receding before them to the hunting and

pastoral grounds of the north and west. Thus the men of

Teutonic race gradually occupied the whole of the reclaimable land,

and became dominant, as is shown by the dominancy of their language,

until they were stopped by the hills of Cumberland, of Wales, and of

Cornwall. The same process seems to have gone on in the arable

districts of Scotland, into which a swarm of colonists from

Northumberland poured in the reign of David I., and quietly settled

upon the soil, which they proceeded to cultivate. It is a

remarkable confirmation of this view of the early settlement of the

country by its present races, that the modern English language

extends over the whole of the arable land of England and Scotland,

and the Celtic tongue only begins where the plough ends.

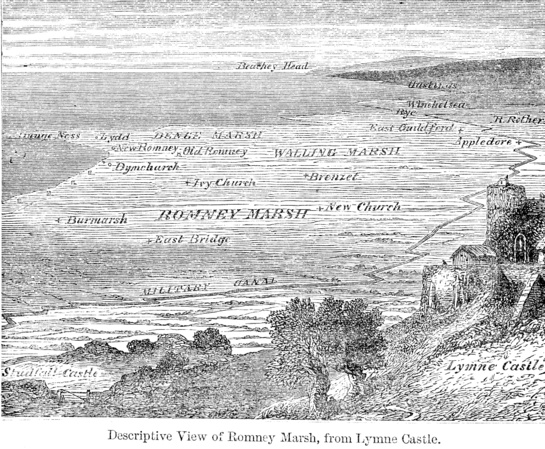

One of the most extensive districts along the English coast,

lying the nearest to the country from which the continental

immigrants first landed, was the tract of Romney Marsh, containing

about 60,000 acres of land along the south coast of Kent. The

reclamation of this tract is supposed to be due to the Frisians.

English history does not reach so far back as the period at which

Romney Marsh was first reclaimed, but doubtless the work is one of

great antiquity. The district is about fourteen miles long and

eight broad, divided into Romney Marsh, Wallend Marsh, Denge Marsh,

and Guildford Marsh. The tract is a dead, uniform level,

extending from Hythe, in Kent, westward to Winchelsea, in Sussex;

and it is to this day held from the sea by a continuous wall or

bank, on the solidity of which the preservation of the district

depends, the surface of the marsh being under the level of the sea

at the highest tides. The following descriptive view of the

marsh, taken from the high ground above the ancient Roman fortress

of Portus Limanis, near the more modern but still ancient castle of

Lymne, will give an idea of the extent and geographical relations of

the district.

The tract is so isolated, that the marshmen say the world is

divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America, and Romney Marsh.

It contains few or no trees, its principal divisions being formed by

dykes and watercourses. It is thinly peopled, but abounds in

cattle and sheep of a peculiarly hardy breed, which are a source of

considerable wealth to the marshmen; and it affords sufficient

grazing for more than half a million of sheep, besides numerous

herds of cattle.

The first portion of the district reclaimed was an island, on

which the town of Old Romney now stands; and embankments were

extended southward as far as New Romney, where an accumulation of

beach took place, forming a natural barrier against further

encroachments of the sea at that point. The old town of Lydd

originally stood upon another island, as did Ivychurch Old

Winchelsea, and Guildford; the sea sweeping round them and rising

far inland at every tide. Burmarsh, and the districts

thereabout, were reclaimed at a more recent period; and by degrees

the islands disappeared, the sea was shut out, and the whole became

firm land. Large additions were made to it from time to time

by the deposits of shingle along the coast, which left several

towns, formerly important seaports, stranded upon the beach far

inland. Thus the ancient Roman port at Lymne, past which the

Limen or Rother is supposed originally to have flowed, is left high

and dry more than three miles from the sea, and sheep now graze

where formerly the galleys of the Romans rode. West Hythe, one

of the Cinque Ports, originally the port for Boulogne, is silted up

by the wide extent of shingle used by the modern School of Musketry

as their practising ground. Old Romney, past which the Rother

afterwards flowed, was one of the ancient ports of the district, but

it is now about two miles from the sea. The marshmen followed

up the receding waters, and founded the town of New Romney, which

also became a Cinque Port; but a storm that occurred in the reign of

Edward I. so blocked up the Rother with shingle, at the same time

breaching the wall, that the river took a new course, and flowed

thenceforward by Rye into the sea; and the port of New Romney became

lost. The point of Dungeness, running almost due south, gains

accumulations of shingle so rapidly from the sea, that it is said to

have extended more than a mile seaward within the memory of persons

living. Rye was founded on the ruins of the Romneys, and also

became a Cinque Port; but notwithstanding the advantage of the river

Rother flowing past it, that port also has become nearly silted up,

and now stands about two miles from the sea. New Winchelsea,

the Portsmouth and Spithead of its day, is left stranded like the

rest of the old Cinque Ports, and is now but a village surrounded by

the remains of its ancient grandeur. All this ruin, however,

wrought by the invasions of the shingle upon the seacoast towns, has

only served to increase the area of the rich grazing ground of the

marsh, which continues year by year to extend itself seaward.

St Thomas Becket Church, Fairfield, Romney Marsh.

© Copyright

dennis smith and licensed for reuse under

this

Creative Commons Licence.

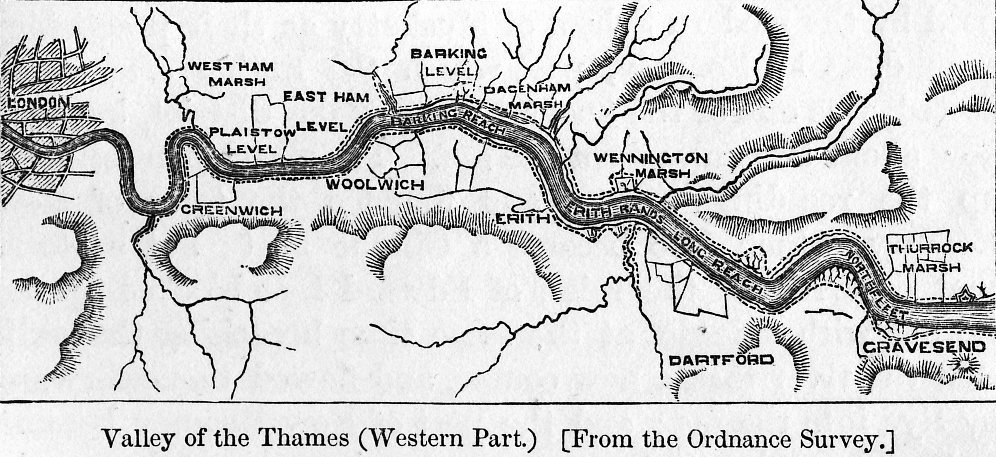

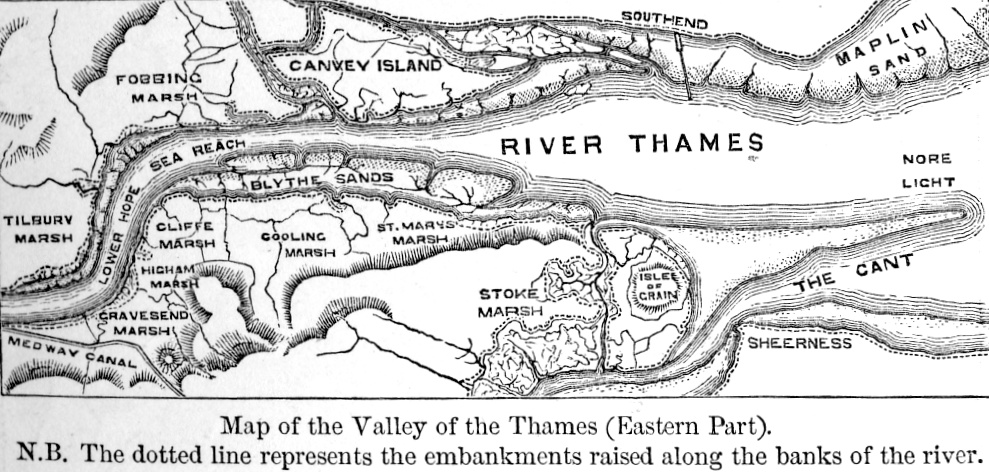

Another highly important work of the same class was the

embankment of the Thames, now the watery highway between the capital

of Great Britain and the world. Before human industry had

confined the river within its present channel, it was a broad

estuary, in many parts between London and Gravesend several miles

wide. The higher tides covered Plumstead and Erith Marshes on

the south, and Plaistow, East Ham, and Barking Levels on the north;

the river meandering in many devious channels at low water, leaving

on either side vast expanses of rich mud and ooze. Opposite

the City of London, the tides washed over the ground now covered by

Southwark and Lambeth; the district called Marsh still reminding us

of its former state, as Bankside informs us of the mode by which it

was reclaimed by the banking out of the tidal waters. |

|

A British settlement is supposed to have been formed at an

early period on the high ground on which St. Paul's Cathedral

stands, by reason of its natural defences, being bounded on the

south by the Thames, on the west by the Fleet, and on the north and

east by morasses, Moorfields Marsh having only been reclaimed within

a comparatively recent period. The natural advantages of the

situation were great, and the City seems to have acquired

considerable importance even before the Roman period. The

embanking of the river has been attributed to that indefatigable

people; but on this point no evidence exists. The numerous

ancient British camps found in all parts of the kingdom afford

sufficient proof that the early inhabitants of the country possessed

a knowledge of the art of earthwork; and it is not improbable that

the same Belgian tribes who reclaimed Romney Marsh were equally

quick to detect the value for agricultural purposes of the rich

alluvial lands along the valley of the Thames, and proceeded

accordingly to embank them after the practice of the country from

which they had come. The work was carried on from one

generation to another, as necessity required, until the Thames was

confined within its present limits, the process of embanking serving

to deepen the river and improve it for purposes of navigation, while

large tracts of fertile land were at the same time added to the

food-producing capacity of the country.

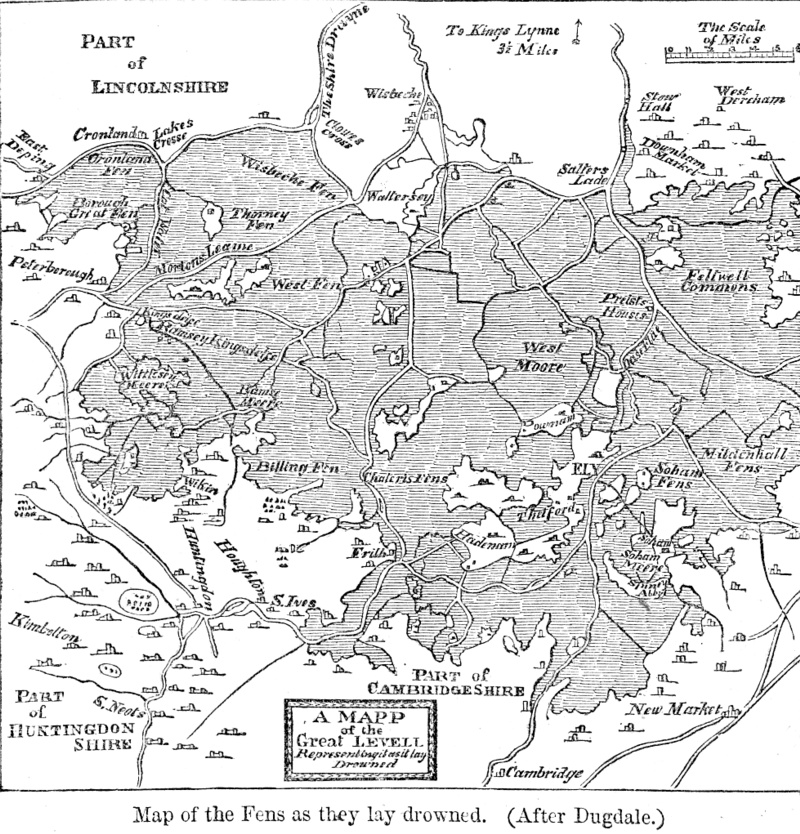

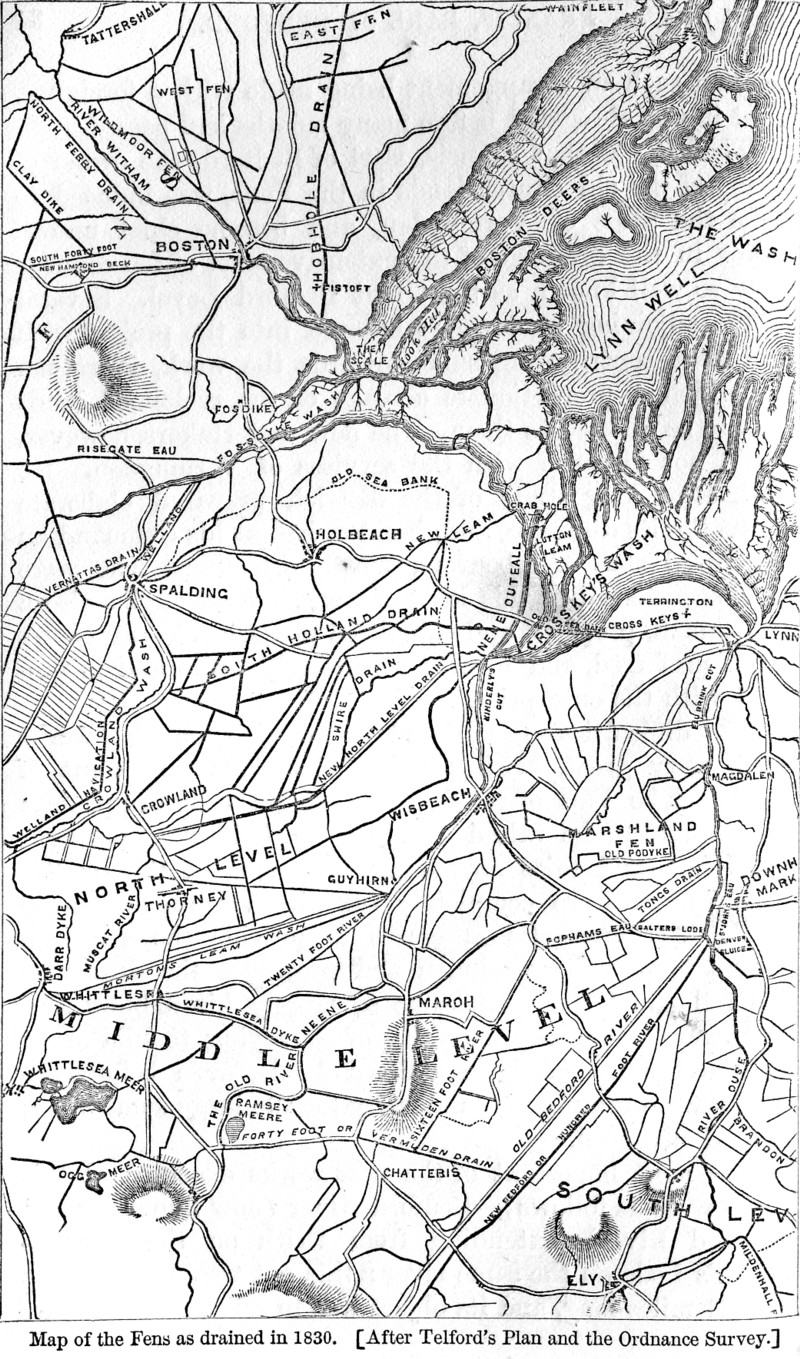

Another of the districts won from the sea, in which a

struggle of skill and industry against the power of water, both

fresh and salt, has been persistently maintained for centuries, is

the extensive low-lying tract of country, situated at the junction

of the counties of Lincoln, Huntingdon, Cambridge, and Norfolk,

commonly known as the Great Level of the Fens. The area of

this district presents almost the dimensions of a province, being

from sixty to seventy miles from north to south, and from twenty to

thirty miles broad, the high lands of the interior bounding it

somewhat in the form of a horse-shoe. It contains about

680,000 acres of the richest land in England, and is as much the

product of art as the kingdom of Holland, opposite to which it lies.

|

|

Not many centuries ago, this vast tract of about two thousand

square miles of land was entirely abandoned to the waters, forming

an immense estuary of the Wash, into which the rivers Witham,

Welland, Glen, Nene, and Ouse discharged the rainfall of the central

counties of England. It was an inland sea in winter, and a

noxious swamp in summer, the waters expanding in many places into

settled seas or mores, swarming with fish and screaming with

wildfowl. The more elevated parts were overgrown with tall

reeds, which appeared at a distance like fields of waving corn; and

they were haunted by immense flocks of starlings, which, when

disturbed, would rise in such numbers as almost to darken the air.

Into this great dismal swamp the floods descending from the interior

were carried, their waters mingling and winding by many devious

channels before they reached the sea. They were laden with

silt, which became deposited in the basin of the Fens. Thus

the river-beds were from time to time choked up, and the intercepted

waters forced new channels through the ooze, meandering across the

level, and often winding back upon themselves, until at length the

surplus waters, through many openings, drained away into the Wash.

Hence the numerous abandoned beds of old rivers still traceable

amidst the Great Level of the Fens—the old Nene, the old Ouse, and

the old Welland. The Ouse, which in past times flowed into the

Wash at Wisbeach (or Ouse Beach), now enters at King's Lynn, near

which there is another old Ouse. But the probability is that

all the rivers flowed into a lake, which existed on the tract known

as the Great Bedford Level, from thence finding their way, by

numerous and frequently shifting channels, into the sea.

Along the shores of the Wash, where the fresh and salt waters

met, the tendency to the deposit of silt was the greatest and in the

course of ages, the land at the outlets of the inland waters became

raised above the level of the interior. Accordingly, the first

land reclaimed in the district was the rich fringe of deposited silt

lying along the shores of the Wash, now known as Marshland and South

Holland. This was effected by the Romans, a hard-working,

energetic, and skilful people; of whom the Britons are said to have

complained [p.10] that they

wore out and consumed their hands and bodies in clearing the woods

and banking the fens. The bulwarks or causeways which they

raised to keep out the sea are still traceable at Po-Dyke in

Marshland, and at various points near the old coast-line. On

the inland side of the Fens the Romans are supposed to have

constructed another great work of drainage, still known as Carr

Dyke, extending from the Nene to the Witham. It means Fen

Dyke, the fens being still called Carrs in certain parts of Lincoln.

This old drain is about sixty feet wide, with a broad, flat bank on

each side; and originally it must have been at least forty miles in

extent, winding along under the eastern side of the high land, which

extends in an irregular line up the centre of the district from

Stamford to Lincoln.

The eastern parts of Marshland and Holland were thus the

first lands reclaimed in the Level, and they were available for

purposes of agriculture long before any attempts had been made to

drain the lands of the interior. Indeed, it is not improbable

that the early embankments thrown up along the coast had the effect

of increasing the inundations of the lower-lying lands farther west;

for, whilst they dammed the salt water out, they also held back the

fresh, no provision having been made for improving and deepening the

outfalls of the rivers flowing through the Level into the Wash.

The Fen lands in winter were thus not only flooded by the rainfall

of the Fens themselves, and by the upland waters which flowed from

the interior, but also by the daily flux of the tides which drove in

from the German Ocean, holding back the fresh waters, and even

mixing with them far inland.

The Fens, therefore, continued flooded with water down to the

period of the Middle Ages, when there was water enough in the Witham

to float the ships of the Danish sea rovers as far inland as

Lincoln, where ships' ribs and timbers have recently been found deep

sunk in the bed of the river. The first reclaimers of the Fen

lands seem to have been the religious recluses, who settled upon the

islands overgrown with reeds and rushes, which rose up at intervals

in the Fen level, and where they formed their solitary settlements.

One of the first of the Fen islands thus occupied was the Isle of

Ely, or Eely—so called, it is said, because of the abundance and

goodness of the eels caught in the neighbourhood, and in which rents

were paid in early times. It stood solitary amid the waste of

waters, and was literally an island. Etheldreda, afterwards

known as St. Audrey, the daughter of the King of the East Angles,

retired thither, secluding herself from the world and devoting

herself to a recluse life. A nunnery was built, then a town,

and the place became famous in the religious world. The pagan

Danes, however, had no regard for Christian shrines, and a fleet of

their pirate ships, sailing across the Fens, attacked the island and

burnt the nunnery. It was again rebuilt, and a church sprang

up, the fame of which so spread abroad that Canute, the Danish king,

determined to visit it. It is related that as his ships sailed

towards the island his soul rejoiced greatly, and on hearing the

chanting of the monks in the quire wafted across the waters, the

king joined in the singing and ceased not until he had come to land.

Canute more than once sailed across the Fens with his ships, and the

tradition survives that on one occasion, when passing from Ramsey to

Peterborough, the waves were so boisterous on Whittlesea Mere (now a

district of fruitful cornfields), that he ordered a channel to be

cut through the body of the Fen westward of Whittlesea to

Peterborough, which to this day is called by the name of the "King's

Delph."

Draining Soham Great Fen.

© Copyright

Alison Rawson and licensed for reuse

under this

Creative Commons Licence.

The other Fen islands which became the centres of subsequent

reclamations were Crowland, Ramsey, Thorney, and Spinney, each the

seat of a monastic establishment. The old churchmen,

notwithstanding their industry, were, however, only able to bring

into cultivation a few detached points, and made very little

impression upon the drowned lands of the Great Level. It often

happened, indeed, that the steps which they took to drain one spot

merely had the effect of sending an increased flood of water upon

another, and perhaps diverting in some new direction the water which

before had driven a mill, or formed a channel for purposes of

navigation. The rivers also were constantly liable to get

silted up, and form for themselves new courses; and sometimes,

during a high tide, the sea would burst in, and in a single night

undo the tedious industry of centuries.

Each suffering locality, acting for itself, did what it could

to preserve the land which had been won, and to prevent the

recurrence of inundations. Dyke-reeves were appointed along

the sea-borders, with a force of shore-labourers at their disposal,

to see to the security of the embankments; and fen-wards were

constituted inland, over which commissioners were set, for the

purpose of keeping open the drains, maintaining the dykes, and

preventing destruction of life and property by floods, whether

descending into the Fens from the high lands or bursting in upon

them from the sea. Where lands became suddenly drowned, the

Sheriff was authorised to impress diggers and labourers for raising

embankments; and commissioners of sewers were afterwards appointed,

with full powers of local action, after the law and usage of Romney

Marsh. In one district we find a public order made that every

man should plant with willows the bank opposite his portion of land

towards the fen, "so as to break off the force of the waves in flood

times;" and swine were not to be allowed to go upon the banks unless

they were ringed, under a penalty of a penny (equal to a shilling in

our money) for every hog found unringed. A still more terrible

penalty for neglect is mentioned by Harrison, who says, "Such as

having walls or banks near unto the sea, and do suffer the same to

decay (after convenient admonition), whereby the water entereth and

drowneth up the country, are by a certain ancient custom

apprehended, condemned, and staked in the breach, where they

remain for ever as parcel of the new wall that is to be made upon

them, as I have heard reported." [p.13]

The Great Level of the Fens remained in a comparatively

unreclaimed state down even to the end of the sixteenth century; and

constant inundations took place, destroying the value of the little

settlements which had by that time been won from the watery waste.

It would be difficult to imagine anything more dismal than the

aspect which the Great Level then presented. In winter, a sea

without waves; in summer, a dreary mud-swamp. The atmosphere

was heavy with pestilential vapours, and swarmed with insects.

The mores and pools were, however, rich in fish and wild-fowl.

The Welland was noted for sticklebacks, a little fish about two

inches long, which appeared in dense shoals near Spalding every

seventh or eighth year, and used to be sold during the season at a

halfpenny a bushel, for field manure. Pike was plentiful near

Lincoln: hence the proverb, "Witham pike, England hath none like."

Fen-nightingales, or frogs, especially abounded. The

birds-proper were of all kinds; wild-geese, herons, teal, widgeons,

mallards, grebes, coots, godwits, whimbrels, knots, dottrels,

yelpers, ruffs, and reeves, some of which have long since

disappeared from England. Mallards were so plentiful that

3,000 of them, with other birds in addition, have been known to be

taken at one draught. Round the borders of the Fens there

lived a thin and haggard population of "Fenslodgers," called

"yellow-bellies" in the inland counties, who derived a precarious

subsistence from fowling and fishing. They were described by

writers of the time as "a rude and almost barbarous sort of lazy and

beggarly people." Disease always hung over the district, ready

to pounce upon the half-starved fenmen. Camden spoke of the

country between Lincoln and Cambridge as "a vast morass, inhabited

by fenmen, a kind of people, according to the nature of the place

where they dwell, who, walking high upon stilts, apply their minds

to grazing, fishing, or fowling." The proverb of

"Cambridgeshire camels" doubtless originated in this old practice of

stilt-walking in the Fens; the fen-men, like the inhabitants of the

Landes, mounting upon high stilts to spy out their flocks across the

dead level. But the flocks of the fenmen consisted principally

of geese, which were called the "fenmen's treasure;" the fenman's

dowry being "three-score geese and a pelt" or sheep-skin used as an

outer garment. The geese throve where nothing else could

exist, being equally proof against rheumatism and ague, though

lodging with the natives in their sleeping-places. Even of

this poor property, however, the slodgers were liable at any time to

be stripped by sudden inundations.

In the oldest reclaimed district of Holland, containing many

old village churches, the inhabitants, in wet seasons, were under

the necessity of rowing to church in their boats. In the other

less reclaimed parts of the Fens the inhabitants were much worse

off. "In the winter time," said Dugdale, "when the ice is only

strong enough to hinder the passage of boats, and yet not able to

bear a man, the inhabitants upon the hards and banks within the Fens

can have no help of food, nor comfort for body or soul; no woman aid

in her travail, no means to baptize a child or partake of the

Communion, nor supply of any necessity saving what these poor

desolate places do afford. And what expectation of health can

there be to the bodies of men, where there is no element good? the

air being for the most part cloudy, gross, and full of rotten harrs;

the water putrid and muddy, yea, full of loathsome vermin; the earth

spungy and boggy, and the fire noisome by the stink of smoaky

hassocks."

The wet character of the soil at Ely may be inferred from the

circumstance that the chief crop grown in the neighbourhood was

willows; and it was a common saying there, that "the profit of

willows will buy the owner a horse before that by any other crop he

can pay for his saddle." There was so much water constantly

lying above Ely, that in olden times the Bishop of Ely was

accustomed to go in his boat to Cambridge. When the outfalls

of the Ouse became choked up by neglect, the surrounding districts

were subject to severe inundations; and after a heavy fall of rain,

or after a thaw in winter, when the river swelled suddenly, the

alarm spread abroad, "the bailiff of Bedford is coming!" the Ouse

passing by that town. But there was even a more terrible

visitor than the bailiff of Bedford; for when a man was stricken

down by the ague, it was said of him, "he is arrested by the bailiff

of Marsh-land;" this disease extensively prevailing all over the

district when the poisoned air of the marshes began to work.

The great perils which constantly threatened the district at

length compelled the attention of the legislature. In 1607,

shortly after the accession of James I., a series of destructive

floods burst in the embankments along the east coast, and swept over

farms, homesteads, and villages, drowning large numbers of people

and cattle. When the King was informed of the great calamity

which had befallen the inhabitants of the Fens, principally through

the decay of the old works of drainage and embankment, he is said to

have made the right royal declaration, that "for the honour of his

kingdom, he would not any longer suffer these countries to be

abandoned to the will of the waters, nor to let them lie waste and

unprofitable; and that if no one else would undertake their

drainage, he himself would become their undertaker." A

Commission was appointed to inquire into the extent of the evil,

from which it appeared that there were not less than 317,242 acres

of land lying outside the then dykes which required drainage and

protection. A bill was brought into Parliament to enable rates

to be levied for the drainage of this land, but it was summarily

rejected. Two years later, a "little bill," for draining 6000

acres in Waldersea County, was passed—the first district Act for Fen

drainage that received the sanction of Parliament. The King

then called Chief-Justice Popham to his aid, and sent him down to

the Fens to undertake a portion of the work; and he induced a

company of Londoners to undertake another portion, the adventurers

receiving two-thirds of the reclaimed lands as a recompense. "Popham's

Eau," and "The Londoners' Lode," still mark the scene of their

operations. The works, however, did not prove very successful, not

having been carried out with sufficient practical knowledge on the

part of the adventurers, nor after any well-devised plan.

There were loud calls for some skilled undertaker or engineer

(though the latter word was not then in use) to stay the mischief,

reclaim the drowned lands, and save the industrious settlers in the

Fens from total ruin. But no English engineer was to be found

ready to enter upon so large an undertaking; and in his dilemma the

King called to his aid one Cornelius Vermuyden, a Dutch engineer, a

man well skilled in works of embanking and draining.

The necessity for employing a foreign engineer to undertake

so great a national work is sufficiently explained by the

circumstance that England was then very backward in all enterprises

of this sort. We had not yet begun that career of industrial

skill in which we have since achieved so many triumphs, but were

content to rely mainly upon the assistance of foreigners.

Holland and Flanders supplied us with our best mechanics and

engineers. Not only did Vermuyden prepare the plans and

superintend the execution of the Great Level drainage, but the works

were principally executed by Flemish workmen. Many other

foreign "adventurers" as they were called, besides Vermuyden,

carried out extensive works of reclamation and embankment of waste

lands in England. Thus a Fleming named Freeston reclaimed the

extensive marsh near Wells in Norfolk; Joas Croppenburgh and his

company of Dutch workmen reclaimed and embanked Canvey Island near

the mouth of the Thames; Cornelius Vanderwelt, another Dutchman,

enclosed Wapping Marsh by means of a high bank, along which a road

was made, called "High Street" to this day; while two Italians,

named Acontius and Castilione, reclaimed the Combo and East

Greenwich marshes on the south bank of the river.

We also relied very much on foreigners for our harbour

engineering. Thus, when a new haven was required at Yarmouth,

Joas Johnson, the Dutchman, was employed to plan and construct it.

When a serious breach occurred in the banks of the Witham at Boston,

Mathew Hakes was sent for from Gravelines, in Flanders, to repair

it; and he brought with him not only the mechanics, but the

manufactured iron required for the work. In like manner, any

unusual kind of machinery was imported from Holland or Flanders

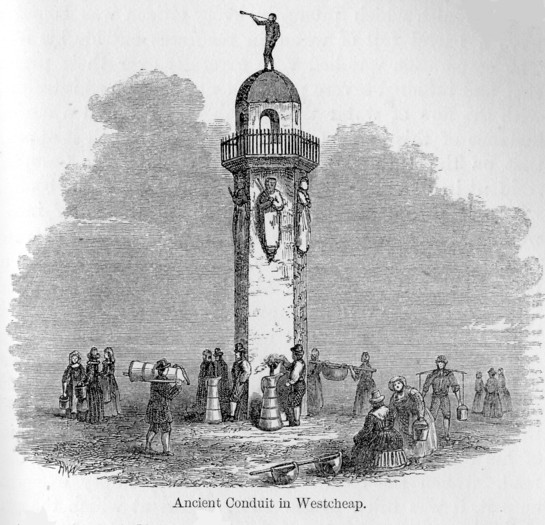

ready made. When an engine was needed to pump water from the

Thames for the supply of London, Peter Morice, the Dutchman, brought

one from Holland, together with the necessary workmen.

England was in former times regarded principally as a

magazine for the supply of raw materials, which were carried away in

foreign ships, and returned to us worked up by foreign artisans.

We grew wool for Flanders, as India, America, and Egypt grow cotton

for England now. Even the wool manufactured at home was sent

to the Low Countries to be dyed. Our fisheries were so

unproductive, that the English markets were supplied by the Dutch,

who sold us the herrings caught in our own seas, off our own shores.

Our best ships were built for us by Danes and Genoese; and when any

skilled sailors' work was wanted, foreigners were employed.

Thus, when the "Mary Rose" sank at Spithead in 1545, Peter de

Andreas, the Venetian, with his ship carpenter and three Italian

sailors, were employed to raise her, sixty English mariners being

appointed to attend upon them merely as labourers.

In short, we depended for our engineering, even more than we

did for our pictures and our music, upon foreigners. Nearly

all the continental nations had a long start of us in art, in

science, in mechanics, in navigation, and in engineering. At a

time when Holland had completed its magnificent system of water

communication, and when France, Germany, and even Russia had opened

up important lines of inland navigation, England had not cut a

single canal, whilst our roads were about the worst in Europe.

It was not until the year 1760 that Brindley began his first canal

for the Duke of Bridgewater.

After the lapse of a century we find the state of things has

become entirely reversed. Instead of borrowing engineers from

abroad, we now send them to all parts of the world.

British-built steam-ships ply on every sea; we export machinery to

all quarters, and supply Holland itself with pumping engines.

During that period our engineers have completed a magnificent system

of canals, turnpike-roads, bridges, and railways, by which the

internal communications of the country have been completely opened

up; they have built lighthouses round our coasts, by which ships

freighted with the produce of all lands, when nearing our shores in

the dark, are safely lighted along to their destined havens; they

have hewn out and built docks and harbours for the accommodation of

a gigantic commerce; whilst their inventive genius has rendered fire

and water the most untiring workers in all branches of industry, and

the most effective agents in locomotion by land and sea.

Nearly all this has been accomplished during the last century, and

much of it within the life of the present generation. How and

by whom certain of these great things have been achieved, it is the

object of the following pages to relate.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

SIR CORNELIUS VERMUYDEN — DRAINAGE OF THE FENS.

CORNELIUS

VERMUYDEN, the Dutch

engineer, was invited over to England about the year 1621, to stem a

breach in the Thames embankment near Dagenham, which had been burst

through by the tide. He was a person of good birth and

education, and was born at St. Martin's Dyke, in the island of

Thelon, in Zealand. He had been trained as an engineer, and

having been brought up in a district where embanking was studied as

a profession, and gave employment to a large number of persons, he

was familiar with the most approved methods of protecting land

against the encroachments of the sea. He was so successful in

his operations at Dagenham, that when it was found necessary to

drain the Royal Park at Windsor, he was employed to conduct the

work; and he thus became known to the king, who shortly after

employed him in the drainage of Hatfield Level, then a royal chase

on the borders of Yorkshire.

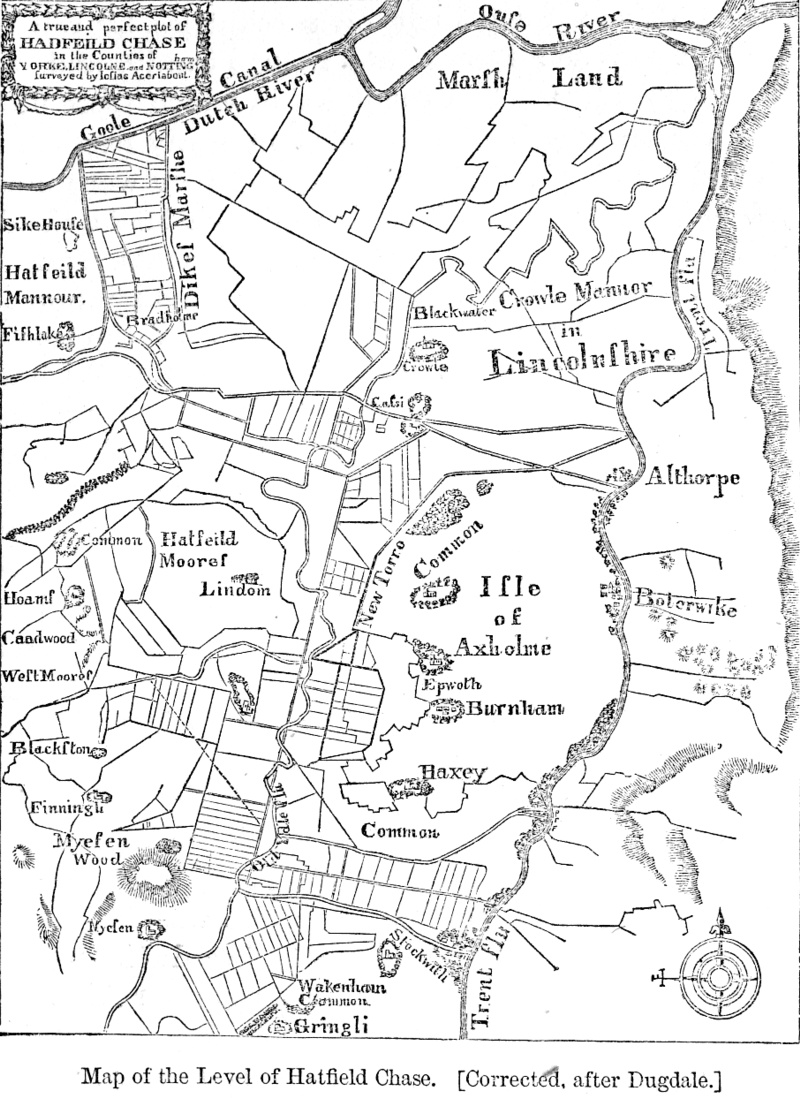

The extensive district of Axholme, of which Hatfield Chase

formed only a part, resembled the Great Level of the Fens in many

respects, being a large fresh-water bay formed by the confluence of

the rivers Don, Went, Ouse, and Trent, which brought down into the

Humber almost the entire rainfall of Yorkshire, Derbyshire,

Nottingham, and North Lincoln, and into which the sea also washed.

The uplands of Yorkshire bounded this watery tract on the west, and

those of Lincolnshire on the east. Rising up about midway

between them was a single hill, or rather elevated ground, formerly

an island, and still known as the Isle of Axholme. There was a ferry

between Sandtoft and that island in times not very remote, and the

farmers of Axholme were accustomed to attend market at Doncaster in

their boats, though the bottom of the sea over which they then rowed

is now amongst the most productive corn-land in England. The waters

extended to Hatfield, which lies along the Yorkshire edge of the

level on the west; and it is recorded in the ecclesiastical history

of that place that a company of mourners, with the corpse they

carried, were once lost when proceeding by boat from Thorne to

Hatfield. When Leland visited the county in 1607, he went by boat

from Thorne to Tudworth, over what at this day is rich ploughed

land. The district was marked by numerous merestones, and many

fisheries are still traceable in local history as having existed at

places now far inland.

|

Across Hatfield

Moors towards the Isle of Axholme. [p.20-1]

© Copyright

Ian Paterson and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

The Isle of Axholme was in former times a stronghold of the Mowbrays,

being unapproachable save by water. In the reign of Henry II., when

Lord Mowbray held it against the King, it was taken by the

Lincolnshire men, who attacked it in boats; and, down to the reign

of James I., the only green spot which rose above the wide waste of

waters was this solitary isle. Before that monarch's time the

south-eastern part of the county of York, from Conisborough Castle

to the sea, belonged for the most part to the crown; but one estate

after another was alienated, until at length, when James succeeded

to the throne of England, there only remained the manor of Hatfield,

which, watery though it was, continued to be dignified with the

appellation of a Royal Chase. There was, however, plenty of deer in

the neighbourhood, for De la Pryme says that in his time they were

as numerous as sheep on a hill, and that venison was as abundant as

mutton in a poor man's kitchen. [p.20-2]

But the principal sport which Hatfield furnished was in the waters

and mores adjacent to the old timber manor-house. Prince Henry, the

King's eldest son, on the occasion of a journey to York, rested at

Hatfield on his way, and had a day's sport in the Royal Chase, which

is thus described by De la Pryme:—"The prince and his retinue all

embarked themselves in almost a hundred boats that were provided

there ready, and having frightened some five hundred deer out of the

woods, grounds, and closes adjoining, which had been drawn there the

night before, they all, as they were commonly wont, took to the

water, and this little royal navy pursuing them, soon drove them

into that lower part of the level, called Thorne Mere, and there,

being up to their very necks in water, their horned heads raised

themselves so as almost to represent a little wood. Here being

encompassed about with the little fleet, some ventured amongst them,

and feeling such and such as were fattest, they either immediately

cut their throats, or else tying a strong long rope to their heads,

drew them to land and killed them."

Such was the last battue in the Royal Chase of Hatfield. Shortly

after, King James brought the subject of the drainage of the tract

under the notice of Cornelius Vermuyden, who, on inspecting it,

declared the project to be quite practicable. The level of the Chase

contained about 70,000 acres, the waters of which, like those of the

Fens, found their way to the sea through many changing channels. Various attempts had been made to diminish the flooding of the

lands. In the fourteenth century several deep trenches were dug, to

let off the water, but they probably admitted as much as they

allowed to escape, and the drowning continued. Commissioners were

appointed, but they did nothing. The country was too poor, and the

people too unskilled, to undertake so expensive and laborious an

enterprise as the effectual drainage of so large a tract.

A local jury was summoned by the King to consider the question, but

they broke up, after expressing their opinion of the utter

impracticability of carrying out any effective plan for the

withdrawal of the waters. Vermuyden, however, declared that he would

undertake and bind himself to do that which the jury had pronounced

to be impossible. The Dutch had certainly been successful beyond all

other nations in projects of the same kind. No people had fought

against water so boldly, so perseveringly, and so successfully. They

had made their own land out of the mud of the rest of Europe, and,

being rich and prosperous, were ready to enter upon similar

enterprises in other countries. On the death of James I., his

successor confirmed the preliminary arrangement which had been made

with Vermuyden, with a view to the drainage of Hatfield Manor; and

on the 24th of May, 1626, after a good deal of negotiation as to

terms, articles were drawn up and signed between the Crown and

Vermuyden, by which the latter undertook to reclaim the drowned

lands, and make them fit for tillage and pasturage. It was a

condition of the contract that Vermuyden and his partners in the

adventure were to have granted to them one entire third of the lands

so recovered from the waters.

Vermuyden was a bold and enterprising man, full of energy and

resources. He also seems to have possessed the confidence of

capitalists in his own country, for we find him shortly after

proceeding to Amsterdam to raise the requisite money, of which

England was then so deficient; and a company was formed composed

almost entirely of Dutchmen, for the purpose of carrying out the

necessary works of reclamation. Amongst those early speculators in

English drainage we find the names of the Valkenburgh family, the

Van Peenens, the Vernatti, Andrew Boccard, and John Corsellis. Of

the whole number of shareholders amongst whom the lands were

ultimately divided, the only names of English sound are those of Sir

James Cambell, Knight, and Sir John Ogle, Knight, who were about the

smallest of the participants.

Several of the Dutch capitalists came over in person to look after

their respective interests in the concern, and Vermuyden proceeded

to bring together from all quarters a large number of workmen,

mostly Dutch and Flemish. It so happened that there were then

settled in England numerous foreign labourers—Dutchmen who had

been brought from Holland to embank the lands at Dagenham and Canvey

Island on the Thames, and others who had been driven from their own

countries by religious persecution—French Protestants from Picardy,

and Walloons from Flanders. The countries in which those people had

been born and bred resembled in many respects the marsh and fen

districts of England, and they were practically familiar with the

reclamation of such lands, the digging of drains, the raising of

embankments, and the cultivation of marshy ground. Those immigrants

had already settled down in large numbers in the eastern counties,

and along the borders of the Fens, at Wisbeach, Whittlesea, Thorny,

Spalding, and the neighbourhood. [p.23] The poor foreigners readily answered Vermuyden's call, and many of

them took service under him at Hatfield Chase, where they set to

work with such zeal, and laboured with such diligence, that before

the end of the second year the work was so far advanced, that a

commission was issued for the survey and division amongst the

participants of the reclaimed lands.

The plan of drainage adopted seems to have been, to carry the waters

of the Idle by direct channels into the Trent, instead of allowing

them to meander at will through the level of the Chase. Deep drains

were cut, through which the water was drawn from the large pools

standing near Hatfield and Thorne. The Don also was blocked out of

the level by embankments, and forced through its northern branch, by

Turnbridge, into the river Aire. But this last attempt proved a

mistake, for the northern channel was found insufficient for the

discharge of the waters, and floodings of the old lands about

Fishlake, Sykehouse, and Snaith took place; to prevent which, a wide

and deep channel, called the Dutch River, was afterwards cut, and

the waters of the Don were sent directly into the Ouse, near Goole. This great and unexpected addition to the cost of the undertaking

appears to have had a calamitous effect, and brought distress and

ruin on many who had engaged in it. The people who dwelt on the

northern branch of the Don complained loudly of the adventurers, who

were denounced as foreigners and marauders; and they were not

satisfied with mere outcry, but took the law into their own hands;

broke down the embankments, assaulted the Flemish workmen, and

several persons lost their lives in the course of the riots which

ensued. [p.25-1] |

|

Vermuyden did what he could to satisfy the inhabitants. He employed

large numbers of native workmen, at considerably higher wages than

had before been paid; and he strenuously exerted himself to relieve

those who had suffered from the changes he had effected, so far as

could be done without incurring a ruinous expense. [p.25-2] Dugdale relates that there could be no question about the great

benefits which the execution of the drainage works conferred upon

the labouring population; for whereas, before the reclamation, the

country round about had been "full of wandering beggars," these had

now entirely disappeared, and there was abundant employment for all

who would work, at good wages. An immense tract of rich land had

been completely recovered from the waters, but it could only be made

valuable and productive after long and diligent cultivation.

Vermuyden was throughout well supported by the Crown, and on the 6th

of January, 1629, he received the honour of knighthood at the hands

of Charles I., in recognition of the skill and energy which he had

displayed in adding so large a tract to the cultivable lands of

England. In the same year he took a grant from the Crown of the

whole of the reclaimed lands in the manor of Hatfield, amounting to

about 24,500 acres, agreeing to pay the Crown the sum of £16,080, an

annual rent of £193. 3s. 5½d., one red rose ancient rent, and an

improved rent of £425 from Christmas, 1630. [p.26-1] Power was also granted him to erect one or more chapels wherein the

Dutch and Flemish settlers might worship in their own language. They

built houses, farmsteads, and windmills; intending to settle down

peacefully to cultivate the soil which their labours had won.

It was long, however, before the hostility and jealousy of the

native population could be appeased. The idea of foreigners settling

as colonists upon lands over which, though mere waste and swamp,

their forefathers had enjoyed rights of common, was especially

distasteful to them, and bred bitterness in many hearts. The

dispossessed fenmen had numerous sympathisers among the rest of the

population. Thus, on one occasion, we find the Privy Council sending

down a warrant to all Postmasters to furnish Sir Cornelius Vermuyden

with horses and a guide to enable him to ride post from London to

Boston, and from thence to Hatfield. [p.26-2] But at Royston "Edward Whitehead, the constable, in the absence of

the postmaster, refused to provide horses, and on being told he

should answer for his neglect, replied, 'Tush! do your worst: you

shall have none of my horses in spite of your teeth.'" [p.27-1] Complaints were made to the Council of the injury done to the

surrounding districts by the drainage works; and an inquisition was

held on the subject before the Earls of Clare and Newcastle, and Sir Gervase Clifton. Vermuyden was heard in defence, and a decision was

given in his favour; but he seems to have acted with precipitancy in

taking out subpoenas against many of the old inhabitants for damage

said to have been done to him and his agents. Several persons were

apprehended and confined in York gaol, and the feeling of bitterness

between the native population and the Dutch settlers grew more

intense from day to day. Lord Wentworth, President of the North, at

length interfered; and after surveying the lands, he ordered that

all suits should cease. Vermuyden was also directed to assign to the

tenants certain tracts of moor and marsh ground, to be enjoyed by

them in common. He attempted to evade the decision, holding it to be

unjust; but the Lord President was too powerful for him, and feeling

that further opposition was of little use, he resolved to withdraw

from the undertaking, which he did accordingly; first conveying his

lands to trustees, and afterwards disposing of his interest in them

altogether. [p.27-2]

The necessary steps were then taken to relieve the old lands which

had been flooded, by the cutting of the Dutch River at a heavy

expense. Great difficulty was experienced in raising the requisite

funds; the Dutch capitalists now holding their hand, or transferring

their interest to other proprietors, at a serious depreciation in

the value of their shares. The Dutch River was, however, at length

cut, and all reasonable ground of complaint so far as respected the

lands along the North Don was removed. For some years the new

settlers cultivated their lands in peace; when suddenly they were

reduced to the greatest distress, through the troubles arising out

of the wars of the Commonwealth.

In 1642 a committee sat at Lincoln to watch over the interests of

the Parliament in that county. The Yorkshire royalists were very

active on the other side of the Don, and the rumour went abroad that

Sir Ralph Humby was about to march into the Isle of Axholme with his

forces. To prevent this, the committee at Lincoln gave orders to

break the dykes, and pull up the flood-gates at Snow-sewer and

Millerton-sluice. Thus in one night the results of many years'

labour were undone, and the greater part of the level again lay

under water. The damage inflicted on the Hatfield settlers in that

one night was estimated at not less than £20,000. The people who

broke the dykes were, no doubt, glad to have the opportunity of

taking their full revenge upon the foreigners for robbing them of

their commons. They levelled the Dutchmen's houses, destroyed their

growing corn, and broke down their fences; and, when some of them

tried to stop the destruction of the sluices at Snow-sewer, the

rioters stood by with loaded guns, and swore they would stay until

the whole levels were drowned again, and the foreigners forced to

swim away like ducks.

After the mischief had been done, the commoners set up their claims

as participants in the lands which had not been drowned, from which

the foreigners had been driven. In this they were countenanced by

Colonel Lilburne, who, with a force of Parliamentarians, occupied

Sandtoft, driving the Protestant minister out of his house, and

stabling their horses in his chapel. A bargain was actually made

between the Colonel and the commoners, by which 2,000 acres of

Epworth Common were to be assigned to him, on condition of their

right being established as to the remainder, while he undertook to

hold them harmless in respect of the cruelties which they had

perpetrated on the poor settlers of the level. When the injured

parties attempted to obtain redress by law, Lilburne, by his

influence with the Parliament, the army, and the magistrates,

parried their efforts for eleven years. [p.29-1] He was, however, eventually compelled to disgorge; and though the

original settlers at length got a decree of the Council of State in

their favour, and those of them who survived were again permitted to

occupy their holdings, the nature of the case rendered it impossible

that they should receive any adequate redress for their losses and

sufferings. [p.29-2]

In the meantime Sir Cornelius Vermuyden had not been idle. He was

as eagerly speculative as ever. Before he parted with his interest

in the reclaimed lands at Hatfield, he was endeavouring to set on

foot his scheme for the reclamation of the drowned lands in the

Cambridge Fens; for we find the Earl of Bedford, in July, 1630,

writing to Sir Harry Vane, recommending him to join Sir Cornelius

and himself in the enterprise. Before the end of the year Vermuyden

entered into a contract with the Crown for the purchase of Malvern

Chase, in the county of Worcester, for the sum of £5,000, which he

forthwith proceeded to reclaim and enclose. Shortly after he took a

grant of 4,000 acres of waste land on Sedgemoor, with the same

object, for which he paid £12,000. Then in 1631 we find him, in

conjunction with Sir Robert Heath, taking a lease for thirty years

of the Dovegang lead-mine, near Wirksworth, reckoned the best in the

county of Derby. But from this point he seems to have become

involved in a series of lawsuits, from which he never altogether

shook himself free. His connection with the Hatfield estates got

him into legal, if not pecuniary difficulties, and he appears for

some time to have suffered imprisonment. He was also harassed by the

disappointed Dutch capitalists at the Hague and Amsterdam, who had

suffered heavy losses by their investments at Hatfield, and took

legal proceedings against him. He had no sooner, however, emerged

from confinement than we find him fully occupied with his new and

grand project for the drainage of the Great Level of the Fens.

The outfalls of the numerous rivers flowing through the Fen Level

having become neglected, the waters were everywhere regaining their

old dominion. Districts which had been partially reclaimed were

again becoming drowned, and even the older settled farms and

villages situated upon the islands of the Fens were threatened with

like ruin. The Commissioners of Sewers at Huntingdon attempted to

raise funds for improving the drainage by levying a tax of six

shillings an acre upon all marsh and fen lands, but not a shilling

of the tax was collected. This measure having failed, the

Commissioners of Sewers of Norfolk, at a session held at King's

Lynn, in 1629, determined to call to their aid Sir Cornelius Vermuyden. At an interview to which he was invited, he offered to

find the requisite funds to undertake the drainage of the Level, and

to carry out the works after the plans submitted by him, on

condition that 95,000 acres of the reclaimed lands were granted to

him as a recompense. A contract was entered into on those terms, but

so great an outcry was immediately raised against such an

arrangement being made with a foreigner, that it was abrogated

before many months had passed.

Then it was that Francis, Earl of Bedford, the owner of many of the

old church-lands in the Fens, was induced to take the place of

Vermuyden, and become chief undertaker in the drainage of the

extensive tract of fen country now so well known as the Great

Bedford Level. Several of the adjoining landowners entered into the

project with the Earl, contributing sums towards the work, in return

for which a proportionate acreage of the reclaimed lands was to be

allotted to them. The new undertakers, however, could not dispense

with the services of Vermuyden. He had, after long study of the

district, prepared elaborate plans for its drainage, and, besides,

had at his command an organized staff of labourers, mostly Flemings,

who were well accustomed to this kind of work. Westerdyke, also a

Dutchman, prepared and submitted plans, but Vermuyden's were

preferred, and he was accordingly authorised to proceed with the

enterprise.

The difficulties encountered in carrying on the works were very

great, arising principally from the want of funds. The Earl of

Bedford became seriously crippled in his resources; he raised money

upon his other property until he could raise no more, while many of

the smaller undertakers were completely ruined. Vermuyden meanwhile

took energetic measures to provide the requisite means to pay the

workmen and prosecute the drainage; until the undertakers became so

largely his debtors that they were under the necessity of conveying

to him many thousand acres of the reclaimed lands, even before the

works were completed, as security for the large sums which he had

advanced.

Old Bedford River.

Looking downstream along Vermuyden's artificially

channelled watercourse,

dating from the 1630s.

© Copyright

Derek Harper and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

The most important of the new works executed at this stage were as

follows;—Bedford River (now known as Old Bedford River), extending

from Erith on the Ouse to Salter's Lode on the same river: this cut

was 70 feet wide and 21 miles long, and its object was to relieve

and take off the high floods of the Ouse. [p.33-1] Bevill's Leam was another extensive cut, extending from Whittlesea

Mere to Guyhirne, 40 feet wide and 10 miles long; Sam's Cut, from

Feltwell to the Ouse, 20 feet wide and 6 miles long; Sandy's Cut,

near Ely, 40 feet wide and 2 miles long; Peakirk Drain, 17 feet wide

and 10 miles long; with other drains, such as Mildenhall, New South

Eau, and Shire Drain. Sluices were also erected at Tydd upon Shire

Drain, at Salter's Lode, and at the Horseshoe below Wisbeach,

together with a clow, [p.33-2]

at Clow's Cross, to keep out the tides; while a strong fresh-water

sluice was also provided at the upper end of the Bedford River. |

|

These works were not permitted to proceed without great opposition

on the part of the Fen-men, who frequently assembled to fill up the

cuts which the labourers had dug, and to pull down the banks which

they had constructed. They also abused and maltreated the foreigners

when the opportunity offered, and sometimes mobbed them while

employed upon the drains, so that in several places they had to work

under a guard of armed men. Difficult though it was to deal with the unreclaimed bogs, the unreclaimed "fen-slodgers" were still more

impracticable. Although their condition was very miserable, they

nevertheless enjoyed a sort of wild liberty amidst the watery

wastes, which they were not disposed to give up. Though they might

alternately shiver and burn with ague, and become prematurely bowed

and twisted with rheumatism, still the Fens were their "native

land," such as it was, and their only source of subsistence,

precarious though it might be. The Fens were their commons, on which

their geese grazed. They furnished them with food, though the

finding thereof was full of adventure and hazard. What cared the

Fen-men for the drowning of the land? Did not the water bring them

fish, and the fish attract wild fowl, which they could snare and

shoot? Thus the proposal to drain the Fens and to convert them into

wholesome and fruitful lands, however important in a national point

of view, as enlarging the resources and increasing the wealth of the

country, had no attraction whatever in the eyes of the Fen-men. They

muttered their discontent, and everywhere met the "adventurers," as

the reclaimers were called, with angry though ineffectual

opposition. But their numbers were too few, and they were too widely

scattered, to make any combined effort at resistance. They could

only retreat to other fens where they thought they might still be

safe, carrying their discontent with them, and complaining that

their commons were taken from them by the rich, and, what was worse,

by foreigners—Dutch and Flemings. The jealous John Bull of the towns

became alarmed at this idea, and had rather that the water than

these foreigners had possession of the land. "What!" asked one of

the objectors, "is the old activitie and abilities of the English

nation grown now see dull and insufficient that wee must pray in

ayde of our neighbours to improve our own demaynes? For matter of securitie, shall wee esteem it of small moment to put into the hands

of strangers three or four such ports as Linne, Wisbeach, Spalding,

and Boston, and permit the countrie within and between them to be

peopled with overthwart neighbours; or, if they quaile themselves,

must wee give place to our most auncient and daungerous enemies, who

will be readie enough to take advantage of soe manic fair inlets

into the bosom of our land, lying soe near together that an army

landing in each of them may easily meet and strongly entrench

themselves with walls of water, and drown the countrie about them at

their pleasure?" [p.34]

Thus a great agitation against the drainage sprang up in the Fen

districts, and a wide-spread discontent prevailed, which, as we

shall afterwards find, exercised an important influence on the

events which culminated in the Great Rebellion of a few years later. Among the other agencies brought to bear against the Fen drainers

was the publication of satirical songs and ballads—the only popular

press of the time; and the popular poets doubtless represented

accurately enough the then state of public opinion, as their ballads

were sung with great applause about the streets of the Fen towns.

One of these, entitled 'The Powte's [p.35]

Complaint,' was among the most popular.

In another popular drinking song, entitled 'The Draining of the

Fennes,' the Dutchmen are pointed out as the great offenders. The

following stanzas may serve as a Specimen:—

|

The Dutchman hath a thirsty soul,

Our cellars are subject to his call;

Let every man, then, lay hold on his bowl,

'Tis pity the German sea should have all.

Then apace, apace drink, drink deep, drink deep,

Whilst 'tis to be had let's the liquor ply;

The drainers are up, and a coile they keep,

And threaten to drain the kingdom dry.

Why should we stay here, and perish with thirst?

To th' new world in the moon away let us goe,

For if the Dutch colony get thither first,

'Tis a thousand to one but they'll drain that too!

Chorus—Then apace, apace drink, &c. |

The Fen drainers might, however, have outlived these attacks, had

the works executed by them been successful; but unhappily they

failed in many respects. Notwithstanding the numerous deep cuts made

across the Fens in all directions at such great cost, the waters

still retained their hold upon the land. The Bedford River and the

other drains merely acted as so many additional receptacles for the

surplus water, without relieving the drowned districts to any

appreciable extent. This arose from the engineer confining his

attention almost exclusively to the inland draining and embankments,

while he neglected to provide any sufficient outfalls for the waters

themselves into the sea. Vermuyden committed the error of adopting

the Dutch method of drainage, in a district where the circumstances

differed in many material respects from those which prevailed in

Holland. In Zeeland, for instance, the few rivers passing through it

were easily banked up and carried out to sea, whilst the low-lying

lands were kept clear of surplus water by pumps driven by windmills. There, the main object of the engineer was to build back the river

and the ocean; whereas in the Great Level the problem to be solved

was, how to provide a ready outfall to the sea for the vast body of

fresh water falling upon as well as flowing through the Fens

themselves. This essential point was unhappily overlooked by the

early drainers; and it has thus happened that the chief work of

modern engineers has been to rectify the errors of Vermuyden and his

followers; more especially by providing efficient outlets for the

discharge of the Fen waters, deepening and straightening the rivers,

and compressing the streams in their course through the Level, so as

to produce a more powerful current and scour, down to their point of

outfall into the sea.

This important condition of successful drainage having been

overlooked, it may readily be understood how unsatisfactory was the

result of the works first carried out in the Bedford Level. In some

districts the lands were no doubt improved by the additional

receptacles provided for the surplus waters, but the great extent of

fen land still lay for the most part wet, waste, and unprofitable. Hence, in 1634, a Commission of Sewers held at Huntingdon pronounced

the drainage to be defective, and the 400,000 acres of the Great

Level to be still subject to inundation, especially in the winter

season. The King, Charles I., then resolved himself to undertake the

reclamation, with the object of converting the Level, if possible,

into "winter grounds." He took so much personal interest in the work

that he even designed a town to be called Charleville, which was to

be built in the midst of the Level, for the purpose of commemorating

the undertaking. Sir Cornelius Vermuyden was again employed, and he

proceeded to carry out the King's design. He had many enemies, but

he could not be dispensed with; being the only man of recognised

ability in works of drainage at that time in England.

The works constructed in pursuance of this new design were these:—an

embankment on the south side of Morton's Leam, from Peterborough to

Wisbeach; a navigable sasse, or sluice, at Standground; a new river

cut between the stone sluice at the Horse-shoe and the sea below

Wisbeach, 60 feet broad and 2 miles long, embanked at both sides;

and a new sluice in the marshes below Tydd, upon the outfall of

Shire Drain. These and other works were in full progress, when the

political troubles of the time came to a height, and brought all

operations to a stand-still for many years. The discontent caused

throughout the Fens by the drainage operations had by no means

abated; but, on the contrary, considerably increased. In other parts

of the kingdom, the attempts made about the same time by Charles I.

to levy taxes without the authority of Parliament gave rise to much

agitation. In 1637 occurred Hampden's trial, arising out of his

resistance to the payment of ship-money: by the end of the same year

the King and the Parliamentary party were mustering their

respective forces, and a collision between them seemed imminent.

At this juncture the discontent which prevailed throughout the Fen

counties was an element of influence, not to be neglected. It was

adroitly represented that the King's sole object in draining the

Fens was merely to fill his impoverished exchequer, and enable him

to govern without a Parliament. The discontent became fanned into a

fierce flame; on which Oliver Cromwell, the member for Huntingdon,

until then comparatively unknown, availing himself of the

opportunity which offered, of increasing the influence of the

Parliamentary party in the Fen counties, immediately put himself at

the head of a vigorous agitation against the further prosecution of

the scheme. He was very soon the most popular man in the district;

he was hailed 'Lord of the Fens' by the Fen-men: and he went from

meeting to meeting, stirring up the public discontent, and giving it

a suitable direction. "From that instant," says Mr. Forster, [p.39]

"the scheme became thoroughly hopeless. With such desperate

determination he followed up his purpose—so actively traversed the

district, and inflamed the people everywhere—so passionately

described the greedy claims of royalty, the gross exactions of the

commission, nay, the questionable character of the improvement

itself, even could it have gone on unaccompanied by incidents of

tyranny,—to the small proprietors insisting that their poor claims

would be merely scorned in the new distribution of the property

reclaimed,—to the labouring peasants that all the profit and

amusement they had derived from commoning in those extensive

wastes were about to be snatched for ever from them,—that, before

his almost individual energy, King, commissioners,

noblemen-projectors, all were forced to retire, and the great

project, even in the state it then was, fell to the ground."

The success of the Cambridge Fen-men, in resisting the reclamation

of the wastes, encouraged those in the more northern districts to

take even more summary measures to get rid of the drainers, and

restore the lands to their former state. The Earl of Lindsey had

succeeded at great cost in enclosing and draining about 35,000 acres

of the Lindsey Level, and induced numerous farmers and labourers to

settle upon the land. They erected dwellings and farm-buildings, and

were busily at work, when the Fen-men suddenly broke in upon them,

destroyed their buildings, killed their cattle, and let in the

waters again upon the land. So, too, in the West and Wildmore Fen

district between Tattershall and Boston in Lincolnshire, where

considerable progress had been made by a body of "adventurers" in

reclaiming the wastes. After many years' labour and much cost, they

had succeeded in draining, enclosing and cultivating an extensive

tract of rich land, and they were peaceably occupied with their

farming pursuits, when a mob of Fen-men collected from the

surrounding districts, and under pretence of playing at football,

levelled the enclosures, burnt the corn and the houses, destroyed

the cattle, and even killed many of the people who occupied the

land. They then proceeded to destroy the drainage works, by cutting

across the embankments and damming up the drains, by which the

country was again inundated and restored to its original state.

|

Wildmore Fen: a

classic Lincolnshire fenland view.

© Copyright

Richard Croft and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

The greater part of the Level thus again lay waste, and the waters

were everywhere extending their dominion over the dry land through

the choking up of the drains and river outfalls by the deposit of

silt. Matters were becoming even worse than before, but could not be

allowed thus to continue. In 1641 the Earl of Bedford and his

participants made an application to the Long Parliament, then

sitting, for permission to re-enter upon the works; but the civil

commotions which still continued prevented any steps being taken,

and the Earl himself shortly after died in a state of comparative

penury, to which he had reduced himself by his devotion to this

great work. Again, however, we find Sir Cornelius Vermuyden upon the

scene. Undaunted by adversity, and undismayed by the popular

outrages committed upon his poor countrymen in Lincolnshire and

Yorkshire, he still urged that the common weal of England demanded

that the rich lands lying under the waters of the Fens should be

reclaimed, and made profitable for human uses. He saw a district

almost as large as the whole of the Dutch United Provinces remaining

waste and worse than useless, and he gave himself no rest until he

had set on foot some efficient measure for its drainage and

reclamation. What part he took in the political discussions of the

time, we know not; but we find the eldest of his sons, Cornelius, a

colonel in the Parliamentary army [p.41]

stationed in the Fens under Fairfax, shortly before the battle of

Naseby. Vermuyden himself was probably too much engrossed by his

drainage project to give heed to political affairs; and besides, he

could not forget that Charles, and Charles's father, had been his

fast friends.

In 1642, while the civil war was still raging, appeared Vermuyden's

'Discourse' on the Drainage of the Fens, wherein he pointed out the

works which still remained to be executed in order effectually to

reclaim the 400,000 acres of land capable of growing corn, which

formed the area of the Great Level. His suggestions formed the

subject of much pamphleteering discussion for several years, during

which also numerous petitions were presented to Parliament urging

the necessity for perfecting the drainage. At length, in 1649,

authority was granted to William, Earl of Bedford, and other

participants, to prosecute the undertaking which his father had

begun, and steps were shortly after taken to recommence the works. Again was Westerdyke, the Dutch engineer, called in to criticise

Vermuyden's plans; and again was Vermuyden triumphant over his

opponent. He was selected, once more, to direct the drainage, which,

looking at the defects of the works previously executed by him, and

the difficulties in which the first Earl had thereby become

involved, must be regarded as a marked proof of the man's force of

purpose, as well as of his recognised integrity of character.

Vermuyden again collected his Dutchmen about him, and vigorously

began operations. But they had not proceeded far before they were

again almost at a standstill for want of funds; and throughout their

entire progress they were hampered and hindered by the same great

difficulty. Some of the participants sold and alienated their shares

in order to get rid of further liabilities; others held on, but

became reduced to the lowest ebb. Means were, however, adopted to

obtain a supply of cheaper labour; and application was made by the

adventurers for a supply of men from amongst the Scotch prisoners

who had been taken at the battle of Dunbar. A thousand of them were

granted for the purpose, and employed on the works to the north of

Bedford River, where they continued to labour until the political

arrangements between the two countries enabled them to return home. When the Scotch labourers had left, some difficulty was again

experienced in carrying on the works. The local population were

still hostile, and occasionally interrupted the labourers employed

upon them; a serious riot at Swaffham having only been put down by

the help of the military. Blake's victory over Van Tromp, in 1652,

opportunely supplied the Government with a large number of Dutch

prisoners, five hundred of whom were at once forwarded to the Level,

where they proved of essential service as labourers.

The most important of the new rivers, drains, and sluices included

in this further undertaking, were the following:—The New Bedford

River, cut from Erith on the Ouse to Salter's Lode on the same

river, reducing its course between these points from 40 to 20 miles:

this new river was 100 feet broad, and ran nearly parallel with the

Old Bedford River. A high bank was raised along the south side of

the new cut, and an equally high bank along the north side of the

old river, a large space of land, of about 5,000 acres, being left

between them, called the Washes, for the floods to "bed in," as

Vermuyden termed it. Then the river Welland was defended by a bank,

70 feet broad and 8 feet high, extending from Peakirk to the Holland

bank. The river Nene was also defended by a similar bank, extending

from Peterborough to Guyhirne and another bank was raised between

Standground and Guyhirne, so as to defend the Middle Level from the

overflowing of the Northamptonshire waters. The river Ouse was in

like manner restrained by high banks extending from Over to Erith,

where a navigable sluice was provided. Smith's Leam was cut, by

which the navigation from Wisbeach to Peterborough was opened out. Among the other cuts and drains completed at the same time, were Vermuyden's Eau, or the Forty Feet Drain, extending from Welch's Dam

to the river Nene near Ramsey Mere; Hammond's Eau, near Somersham,

in the county of Huntingdon; Stonea Drain and Moore's Drain, near

March, in the Isle of Ely; Thurlow's Drain, extending from the Forty

Feet to Popham's Eau; and Conquest Lode, leading to Whittlesea Mere.