|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IX.

EXTENSION OF THE DUKE'S CANAL TO THE MERSEY.

THE

CANAL had scarcely been

opened to Manchester when we find Brindley occupied, at the instance

of the Duke, in surveying the country between Stretford and the

river Mersey, with the view of carrying out a canal in that

direction for the accommodation of the growing trade between

Liverpool and Manchester. The first boat-load of coals sailed

over the Barton viaduct to Manchester on the 17th of July, 1761; on

the 7th of September following we find Brindley at Liverpool, [p.184]

"rocconitoring;" and, by the end of the month, he was busily engaged

levelling for a proposed canal to join the Mersey at Hempstones,

about eight miles below Warrington Bridge, from whence there was a

natural tideway to Liverpool, about fifteen miles distant.

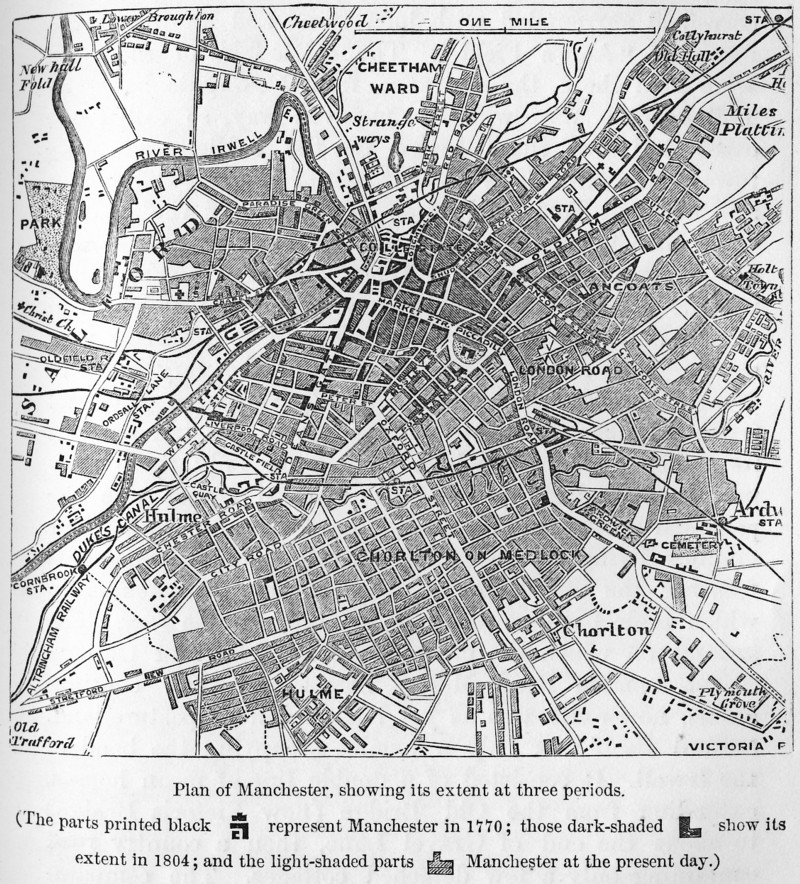

The project in question was a very important one

on public grounds. We have seen how the community of

Manchester had been hampered by defective road and water

communications, which seriously affected its supplies of food and

fuel, and, at the same time, by retarding its trade, hindered to a

considerable extent the regular employment of its population.

The Duke of Bridgewater, by constructing his canal, had opened up an

abundant supply of coal, but the transport of the raw materials of

manufacture was still as much impeded as before. Liverpool was

the natural port of Manchester, from which it drew its supplies of

cotton, wool, silk, and other produce, and to which it returned them

for export when worked up into manufactured articles.

There were two existing modes by which the

communication was kept up between the two places: one was by the

ordinary roads, and the other by the rivers Mersey and Irwell.

From a statement published in December, 1761, it appears that the

weight of goods then carried by land from Manchester to Liverpool

was "upwards of forty tons per week," or about two thousand tons a

year. This quantity, insignificant though it must appear when

compared with the enormous traffic now passing between the two

towns, was then thought very large, as no doubt it was when the

limited trade of the country is taken into account. But the

cost of transport was the important feature; it was not less than

two pounds sterling per ton—this heavy charge being almost entirely

attributable to the execrable state of the roads. It was

scarcely possible to drive waggons along the ruts and through the

sloughs which lay between the two places at certain seasons of the

year, and even pack-horses had considerable difficulty in making the

journey.

The other route between the towns was by the

navigation of the rivers Mersey and Irwell. The raw materials

used in manufacture were principally transported from Liverpool to

Manchester by this route, at a cost of about twelve shilling per

ton; the carriage of timber and such like articles costing not less

than twenty per cent. on their value at Liverpool. But the

navigation was also very tedious and difficult. The boats

could only pass up to the first lock at the Liverpool end with the

assistance of a spring tide; and further up the river there were

numerous fords and shallows which the boats could only pass in great

freshes, or, in dry seasons, by drawing extraordinary quantities of

water from the locks above. Then, in winter, the navigation

was apt to be impeded by floods, and occasionally it was stopped

altogether. In short, the growing wants of the population

demanded an improved means of transit between the two towns, which

the Duke of Bridgewater now determined to supply.

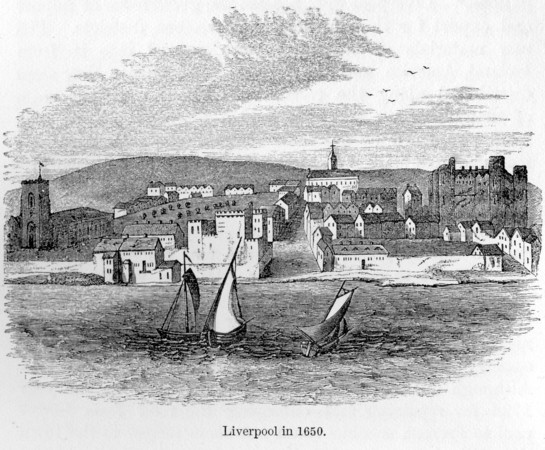

The growth of Liverpool as a seaport has been

comparatively recent. At a time when Bristol and Hull

possessed thriving harbours, resorted to by foreign ships, Liverpool

was little better than a fishing village, its only distinction being

that it was a convenient place for setting sail to Ireland. In

the war between France and England which broke out in 1347, when

Edward the Third summoned the various ports in the kingdom to make

contributions towards the naval power according to their means,

London was required to provide 25 ships and 662 men; Bristol 22

ships and 608 men; Hull, 16 ships and 466 men, whilst Liverpool was

only asked to find 1 bark and 6 men! In Queen Elizabeth's

time, the burgesses presented a petition to Her Majesty, praying her

to remit a subsidy which had been imposed upon it and other seaport

towns, in which they styled their native place "Her Majesty's poor

decayed town of Liverpool." Chester was then of considerably

greater importance as a port. In 1634-5, when Charles I. made

his unconstitutional levy of ship-money throughout England,

Liverpool was let off with a contribution of £15, whilst Chester

paid £100, and Bristol not less than £1,000.

The channel of the Dee, however, becoming silted

up, the trade of Chester decayed, and that of Liverpool rose upon

its ruins. In 1699 the excavation of the Old Dock was begun;

but it was used only as a tidal harbour (being merely an enclosed

space with a small pier) until the year 1709, when an Act was

obtained enabling its conversion into a wet dock; since which time a

series of docks have been constructed, extending for about five

miles along the north shore of the Mersey, which are among the

greatest works of modern times, and afford an almost unequalled

amount of shipping accommodation.

From that time forward the progress of the port

of Liverpool has kept steady pace with the trade and wealth of the

country behind it, and especially with the manufacturing activity

and energy of the town of Manchester. Its situation at the

mouth of a deep and navigable river, its convenient proximity to

districts abounding in coal and iron and inhabited by an industrious

and hardy population, were unquestionably great advantages.

But these of themselves would have been insufficient to account for

the extraordinary progress made by Liverpool during the last

century, without the opening up of the great system of canals, which

brought not only the towns of Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Lancashire

into immediate connection with that seaport, but also the

manufacturing districts of Staffordshire, Warwickshire, and the

other central counties of England situated at the confluence of the

various navigations. [p.188-1]

Liverpool thus became the great focus of import and export for the

northern and western districts. The raw materials of commerce

were poured into it from Ireland, America, and the Indies.

From thence they were distributed along the canals amongst the

various seats of manufacturing industry, and a large proportion was

readily returned by the same route to the same port, in a

manufactured state, for shipment to all parts of the world. |

Royal Seaforth

Container Terminal, Liverpool. [p.188-2]

© Copyright

Carl Davies and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

At the time of which we speak, however, it will be observed that the

communication between Liverpool and Manchester was very imperfect. It was not only difficult to convey goods between the two places,

but it was

also difficult to convey persons. In fine weather, those who

required to travel the thirty miles which separated them, could ride

or walk, resting at Warrington for the night. But in winter the

roads, like most of the other

country roads at the time, were simply impassable. Although an Act

had been passed as early as the year 1726 for repairing and

enlarging the road from Liverpool to Prescot, coaches could not come

nearer to the

town than Warrington in 1750, the road being impracticable for such

vehicles even in summer. [p.188-3]

A stage-coach was not started between Liverpool and Manchester until

the year 1767, performing the journey only three times a week. It

required six and sometimes eight horses to draw the lumbering

vehicle and its

load along the ruts and through the sloughs,—the whole day being

occupied in making the journey. The coach was accustomed to start

early in the morning from Liverpool; it breakfasted at Prescot,

dined at

Warrington, and arrived at Manchester usually in time for supper. On

one occasion, at Warrington, the coachman intimated his wish to

proceed, when the company requested him to take another pint, as

they had not

finished their wine, asking him at the same time if he was in a

burry? "Oh," replied the driver, "I'm not partic'lar to an hour or

so!" As late as 1775, no mail-coach ran between Liverpool and any

other town, the bags

being conveyed to and from it on horseback; and one letter-carrier

was found sufficient for the wants of the place. A heavy stage then

ran, or rather crawled, between Liverpool and London, making only

four journeys a

week in the winter time. It started from the Golden Talbot, in

Water-street, and was three days on the road. It went by Middlewich,

where one of its proprietors kept the White Bear inn; and during

the Knutsford race-week the coach was sent all the way round by that place, in order to

bring customers to the Bear.

We have said that Brindley was engaged upon the preliminary survey

of a canal to connect Manchester with the Mersey, immediately after

the original Worsley line had been opened, and before its paying

qualities had

been ascertained. But the Duke, having once made up his mind as to

the expediency of carrying out this larger project, never halted nor

looked back, but made arrangements for prosecuting a bill for the

purpose of

enabling the canal to be made in the very next session of

Parliament.

We find that Brindley's first visit to Liverpool and the intervening

district on the business of the survey was made early in September,

1761. During the remainder of the month he was principally occupied

in Staffordshire,

looking after the working of his fire-engine at Fenton Vivian,

carrying out improvements in the silk-manufactory at Congleton, and

inspecting various mills at Newcastle-under-Lyne and the

neighbourhood. His only idle

day during that month seems to have been the 22nd, which was a

holiday, for he makes the entry in his book of "crounation of Georg

and Sharlot," the new King and Queen of England. By the 25th we find

him again

with the Duke at Worsley, and on the 30th he makes the entry, "set

out at Dunham to Level for Liverpool." The work then went on

continuously until the survey was completed; and on the 19th of

November he set out

for London, with £7. 18s. in his pocket.

In the course of his numerous journeys, we find Brindley carefully

noting down the various items of his expenses, which were curiously

small. Although he was four or five days on the road to London, and

stayed eight

days there, his total expenses, both going and returning, amounted

to only £4. 8s.: it is most probable, however, that he lived at the

Duke's house whilst in town. On the 1st of December we find him, on

his return

journey to Worsley, resting the first night at a place called Brickhill; the next at Coventry, where he makes the entry, "Moy mar

had a bad fall the frasst;" the third at Sandon; the fourth at

Congleton; and the fifth at

Worsley. He had still some inquiries to make as to the depth of

water and the conditions of the tide at Hempstones; and for three

days he seems to have been occupied in traffic-taking, with a view

to the evidence to

be given before Parliament; for on the 10th of December we find him

at Stretford, "to count the caridgos," and on the 12th, he is at

Manchester for the same purpose, "counting the loded caridgos and

horses."

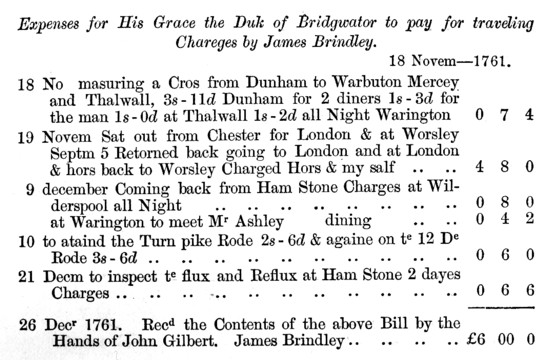

The following bill refers to some of the work done by him at this

time, and is a curious specimen of an engineer's travelling charges

in those days—the engineer himself being at the same time paid at

the rate of 3s. 6d.

a day:—

In the early part of the month of January, 1762, we find Brindley

busy measuring soughs, gauging the tides at Hempstones, and

examining and altering the Duke's paper-mills and iron

slitting-mills at Worsley; and on

the 7th we find this entry: "to masuor the Duks pools I and

Smeaton." On the following day he makes "an ochilor survey from

Saldnoor [Sale Moor] to Stockport," with a view to a branch canal

being carried in that

direction. On the 14th, he sets out from Congleton, by way of Ashbourne, Northampton, and Dunstable, arriving in London on the

fifth day.

Immediately on his arrival in town we find him proceeding to rig

himself out in a new suit of clothes. His means were small, his

habits thrifty, and his wardrobe scanty; but as he was about to

appear in an important

character, as the principal engineering witness before a

Parliamentary Committee in support of the Duke's bill, he felt it

necessary to incur an extra expenditure on dress for the occasion. Accordingly, on the morning of

the 18th we find him expending a guinea—an entire week's pay—in the

purchase of a pair of new breeches; two guineas on a coat and

waistcoat of broadcloth, and six shillings for a pair of new shoes. The subjoined is

a facsimile of the entry in his pocketbook.

It will be observed that an expenditure is here entered of nine

shillings for going to "the play." It would appear that his friend

Gilbert, who was in London with him on the canal business, prevailed

on Brindley to go with

him to the theatre to see Garrick in the play of 'Richard III.', and

he went. He had never been to an entertainment of the kind before;

but the excitement which it caused him was so great, and it so

completely disturbed

his ideas, that he was unfitted for business for several days after. He then declared that no consideration should tempt him to go a

second time, and he held to his resolution. This was his first and

only visit to the play. The following week he enters in his memorandum-book concerning

himself "ill in bed," and the first Sunday after his recovery we

find him attending service at "Sant Mary's Church." The service did

not make him ill, as

the play had done, and on the following day he attended the House of

Commons on the subject of the Duke's bill.

The proposed canal from Manchester to the Mersey at Hempstones

stirred up an opposition which none of the Duke's previous bills had

encountered. Its chief opponents were the proprietors of the Mersey

and Irwell

Navigation, who saw their monopoly assailed by the measure; and,

unable though they had been satisfactorily to conduct the then

traffic between Liverpool and Manchester, they were unwilling to

allow of any

additional water service being provided between the two towns. Having already had sufficient evidence of the Duke's energy and

enterprise, from what he had been able to effect in so short a time

in forming the canal

between Worsley and Manchester, the Navigation Company were not

without reason alarmed at his present project.

At first they tried to buy him off by concessions. They offered to

reduce the rate of 3s. 4d. per ton of coals, timber, &c., conveyed

upon the Irwell between Barton and Manchester, to 6d. if he would

join their Navigation

at Barton and abandon the part of his canal between that point and

Manchester; but he would not now be diverted from his plan, which he

resolved to carry into execution if possible. Again they tried to

conciliate his

Grace by offering him certain exclusive advantages in the use of

their Navigation. But it was again too late; and the Duke having a

clear idea of the importance of his project, and being assured by

his engineer of its

practicability and the great commercial value of the undertaking,

determined to proceed with the measure. It offered to the public the

advantages of a shorter line of navigation, not liable to be

interrupted by floods on the

one hand or droughts on the other, and, at the same time, a much

lower rate of freight, the maximum charge proposed in the bill being

6s. a ton against 12s., the rate charged by the Mersey and Irwell

Navigation

between Liverpool and Manchester.

The opposition to the bill was led by Lord Strange, son of the Earl

of Derby, one of the members for the county of Lancaster, who took

the part of the "Old Navigators," as they were called, in resisting

the bill. The

question seems also to have been treated as a political one; and,

the Duke and his friends being Whigs, Lord Strange mustered the Tory

party strongly against him. Hence we find this entry occurring in

Brindley's

notebook, under date the 16th of February: "The Toores [Tories] mad

had [made head] agave ye Duk."

The principal objections offered to the proposed canal were, that

the landowners would suffer by it from having their lands cut

through and covered with water, by which a great number of acres

would be for ever lost to

the public; that there was no necessity whatever for the canal, the

Mersey and Irwell Navigation being sufficient to carry more goods

than the trade then existing required; that the new navigation

would run almost

parallel with the old one, and offered no advantage to the public

which the existing river navigation did not supply; that the canal

would drain away the waters which supplied the rivers, and be very

prejudicial to them, if

not totally destructive, in dry seasons; that the proprietors of

the old navigation had invested their money on the faith of

protection by Parliament, and to permit the new canal to be

established would be a gross

interference with their vested rights; and so on.

To these objections there were very sufficient answers. The bill

provided for full compensation being made to the owners of lands

through which the canal passed, and, in addition, it was provided

that all sorts of manure

should be carried for them without charge. It was also shown that

the Duke's canal could not abstract water from either the Mersey or

the Irwell, as the level of both rivers was considerably below that

of the intended

canal, which would be supplied almost entirely from the drainage of

his own coal-mines at Worsley; and with respect to the plea of

vested rights set up, it was shown that Parliament, in granting

certain powers to the

old navigators, had regard mainly to the convenience and advantage

of the public; and they were not precluded from empowering a new

navigation to be formed if it could be proved to present a more

convenient and

advantageous mode of conveyance.

On these grounds the Duke was strongly supported by the inhabitants

of the localities proposed to be served by the intended canal. The "Junto

of Old Navigators of the Mersey and Irwell Company" had for many

years

carried things with a very high hand, extorted the highest rates,

and, in cases of loss by delay or damage to goods in transit,

refused all redress. A feeling very hostile to them and their

monopoly had accordingly grown

up, which now exhibited itself in a powerful array of petitions to

Parliament in favour of the Duke's bill.

On the 17th of February, 1762, the bill came before the Committee of

the House of Commons, and Brindley was examined in its support. We

regret that no copy of his evidence now exists [p.195] from which we

might

have formed an opinion of the engineer's abilities as a witness.

Some curious anecdotes have, however, been preserved of his

demeanour and evidence on canal bills before Parliament. When asked,

on one occasion,

to produce a drawing of an intended bridge, he replied that he had

no plan of it on paper, but he would illustrate it by a model. He

went out and bought a large cheese, which he brought into the room

and cut into two

equal parts, saying, "Here is my model." The two halves of the

cheese represented the semicircular arches of his bridge; and by

laying over them some long rectangular object, he could thus readily

communicate to

the Committee the position of the river flowing underneath and the

canal passing over it. [p.196-1]

On another occasion, when giving his evidence, he spoke so

frequently about "puddling," describing its uses and advantages,

that some of the members expressed a desire to know what this

extraordinary mixture

was, that could be applied to such important purposes. Preferring a

practical illustration to a verbal description, Brindley caused a

mass of clay to be brought into the committee-room, and, moulding it

in its raw untempered state into the form of a trough, he poured into it some

water, which speedily ran through and disappeared. He then worked

the clay up with water to imitate the process of puddling, and again

forming it into

a trough, filled it with water, which was now held in without a

particle of leakage. "Thus it is," said Brindley, "that I form a

water-tight trunk to carry water over rivers and valleys, wherever

they cross the path of the

canal." [p.196-2]

Again, when Brindley was giving evidence before a Committee of the

House of Peers as to the lockage of his proposed canal, one of their

Lordships asked him, "But what is a lock?" on which the engineer

took a piece

of chalk from his pocket and proceeded to explain it by means of a

diagram which he drew upon the floor, and made the matter clear at

once. [p.197] He used to be so ready with his chalk for purposes of

illustration,

that it became a common saying in Lancashire, that "Brindley and

chalk would go through the world." He was never so eloquent as when

with his chalk in hand, it stood him in lieu of tongue.

On the day following Brindley's examination before the Committee on

the Duke's bill, that is, on the 18th of February, we find him

entering in his note-book that the Duke sent out "200 leators" to

members—possible

friends of the measure; containing his statement of reasons in

favour of the bill. On the 20th Mr. Tomkinson, the Duke's solicitor,

was under examination for four hours and a half. Sunday intervened,

on which day

Brindley records that he was "at Lord Harrington's." On the

following day, the 22nd, the evidence for the bill was finished, and

the Duke followed this up by sending out 250 more letters to

members, with an abstract of

the evidence given in favour of the measure. On the 26th there was a

debate of eight hours on the bill, followed by a division, in

Committee of the whole House, thus recorded by Brindly:—

|

"ad a grate Division of 127 fort Duk

98 nos

for te Duk 29 Me Jorete" |

But the bill had still other discussions and divisions to encounter

before it was safe. The Duke and his agents worked with great

assiduity. On the 3rd of March he caused 250 more letters to be

distributed amongst the

members; and on the day after we find the House wholly occupied

with the bill. We quote again from Brindley's record: "4 [March] ade bate at the Hous with grate vigor 3 divisons the Duke carved by

Numbers evory time a 4 division moved but Noes yelded." On the next

day we read "wont thro the closes;" from which we learn that the

clauses were settled and passed. Mr. Gilbert and Mr. Tomkinson then

set out for Lancashire:

the bill was safe. It passed the third reading, Brindley making

mention that "Lord Strange" was "sick with geef [grief] on that

affair Mr. Wellbron want Rong god,"—which latter expression we do

not clearly understand,

unless it was that Mr. Wilbraham wanted to wrong God. The bill was

carried to the Lords, Brindley on the 10th March making the entry, "Touk

the Lords oath." But the bill passed the Upper House "without opposishin,"

and received the Royal Assent on the 24th of the same month.

On the day following the passage of the bill through the House of

Lords (of which Brindley makes the triumphant entry, "Lord Strange

defetted"), he set out for Lancashire, after nine weary weeks' stay

in London. To

hang about the lobbies of the House and haunt the office of the

Parliamentary agent, must have been excessively irksome to a man

like Brindley, accustomed to incessant occupation and to see works

growing under

his hands. During this time we find him frequently at the office of

the Duke's solicitor in "Mary Axs;" sometimes with Mr. Tomkinson,

who paid him his guinea a-week during the latter part of his stay;

and on several

occasions he is engaged with gentlemen from the country, advising

them about "saltworks at Droitwitch" and mill-arrangements in

Cheshire.

Many things had fallen behind during his absence and required his

attention, so he at once set out home; but the first day, on

reaching Dunstable, he was alarmed to find that his mare, so long

unaccustomed to the

road, had "allmost lost ye use of her Limes" [limbs]. He therefore

went on slowly, as the mare was a great favourite with him—his

affection for the animal having on one occasion given rise to a

serious quarrel between

him and Mr. Gilbert —and he did not reach Congleton until the sixth

day after his setting out from London. He rested at Congleton for

two days, during which he "settled the geering of the silk-mill,"

and then proceeded

straight on to Worsley to set about the working survey of the new

canal.

The course of this important canal, which unites the mills of

Manchester with the shipping of Liverpool, is about twenty-four

miles in length. [p.200] From Longford Bridge, near Manchester, its

course lies in a south-westerly direction for some distance, crossing the river Mersey at a

point about five miles above its junction with the Irwell. At

Altrincham it proceeds in a westerly direction, crossing the river Bollin about three miles

further on, near Dunham. After crossing the Bollin, it describes a

small semicircle, proceeding onward in the valley of the Mersey, and

nearly in the direction of the river as far as the crossing of the

high road from

Chester to Warrington. It then bends to the south to preserve the

high level, passing in a southerly direction as far as Preston, in

Cheshire, from whence it again turns round to the north to join the

river Mersey. [For

Map of the Canal, see pp. 168-9.]

The canal lies entirely in the lower part of the new red sandstone,

the principal earthworks consisting of the clays, marls, bog-earths,

and occasionally the sandstones of this formation. The heaviest bog

crossed in the

line of the works was Sale Moor, west of the Mersey, where the

bottom was of quicksand; and the construction of the canal at that

part was probably an undertaking of as formidable a character as the

laying of the

railroad over Chat Moss proved some sixty years later. But Brindley,

like Stephenson, looked upon a difficulty as a thing to be overcome; and when an obstruction presented itself, he at once set his wits

to work and

studied how it was best to be grappled with and surmounted. A large

number of brooks had to be crossed, and also two important rivers,

which involved the construction of numerous aqueducts, bridges, and

culverts, to

provide for the surface water supply of the district. It will,

therefore, be obvious that the undertaking was of a much more

important nature—more difficult for the engineer to execute, and

more costly to the noble

proprietor who found the means for carrying it to a completion—than the comparatively limited and inexpensive work between Worsley

and Manchester, which we have above described.

The capital idea which Brindley early formed and determined to carry

out, was to construct a level of dead water all the way from

Manchester to a point as near to the junction of the canal with the

Mersey as might be

found practicable. Such a canal, he clearly saw, would not be so

expensive to work as one furnished with locks at intermediate

points. Brindley's practice of securing long levels of water in

canals was in many respects

similar to that of George Stephenson with reference to flat

gradients upon railways; and in all the canals that he constructed,

he planned and carried them out as far as possible after this

leading principle. Hence the

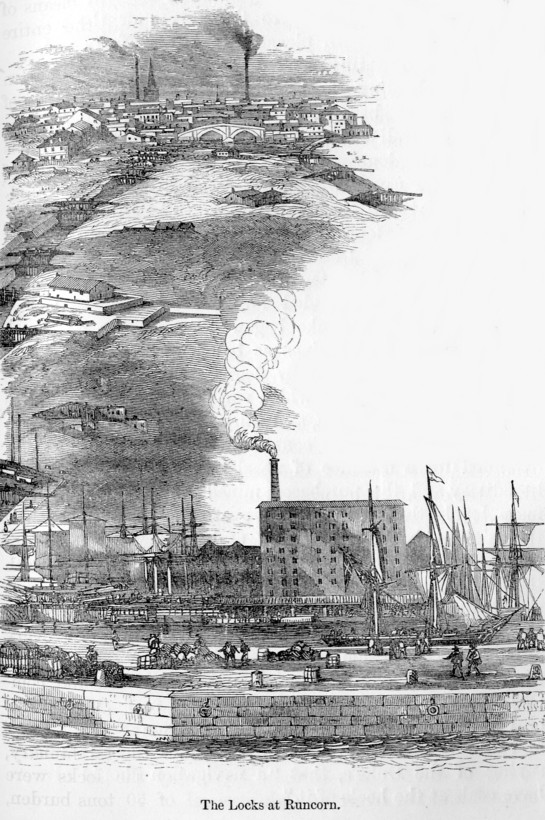

whole of the locks on the Duke's canal were concentrated at its

lower end near Runcorn, where the navigation descended, as it were

by a flight of water steps, into the river Mersey. Lord Ellesmere

has observed that

this uninterrupted level of the Bridgewater Canal from Leigh and

Manchester to Runcorn, and the concentration of its descent to the

Mersey at the latter place, have always been considered as among the

most striking

evidences of the genius and skill of Brindley.

Course of the Runcorn Locks, 2008. [p.201]

© Copyright

Michael Steele and licensed for reuse

under this

Creative Commons Licence.

There was, as usual, considerable delay in obtaining possession of

the land on which to commence the works. The tenants required a

certain notice, which must necessarily expire before the Duke's

engineer could

take possession; and numerous obstacles were thrown in his way,

both by tenants and landlords hostile to the undertaking. In many

cases the Duke had to pay dearly for the land purchased under the

compulsory

powers of his Act. Near Lymm, the canal passed through a little bit

of garden belonging to a poor man's cottage, the only produce

growing upon the ground being a pear-tree. For this the Duke had to

pay thirty guineas,

and it was thought a very extravagant price at that time. Since the

introduction of railways, the price would probably be considered

ridiculously low. For the land on which the warehouses and docks

were built at

Manchester, the Duke had to pay in all the much more formidable sum

of about forty thousand pounds.

The Old Quay Navigation, even at the last moment, thought to delay

if not to defeat the Duke's operations, by lowering their rates

nearly one-half. Only a few days after the Royal Assent had been

given to the bill, they

published an announcement, appropriately dated the 1st of April,

setting forth the large sacrifices they were about to make, and

intimating that "from their Reductions in Carriage a real and

permanent Advantage will

arise to the Public, and they will experience that Utility so cried

up of late, but which has hitherto only existed in promises." The

Duke heeded not the ineffective blow thus aimed at him: he was only

more than ever

resolved to go forward with his canal. He was even offered the

Mersey Navigation itself at the price of thirteen thousand pounds;

but he would not have it now at any price.

The public spirit and enterprise displayed by many of the young

noblemen of those days was truly admirable. Brindley had for several

years been in close personal communication with Earl Gower as to the

construction of the canal intended to unite the Mersey with the

Trent and the Severn, and thus connect the ports of Liverpool, Hull,

and Bristol, by a system of inland water-communication. With this

object, as we have

seen, he had often visited the Earl at his seat at Trentham, and

discussed with him the plans by which this truly magnificent

enterprise was to be carried out; and he had frequently visited the

Earl of Stamford at his

seat at Enville for the same purpose. But those schemes were too

extensive and costly to be carried out by the private means of

either of those noblemen, or even by both combined. They were,

therefore, under the

necessity of stirring up the latent enterprise of the landed

proprietors in their respective districts, and waiting until they

had received a sufficient amount of local support to enable them to

act with vigour in carrying their

great design into effect.

The Duke of Bridgewater's scheme of uniting Manchester and Liverpool

by an entirely new line of water-communication, cut across bogs and

out of the solid earth in some places, and carried over rivers and

valleys at

others by bridges and embankments, was scarcely less hold or costly. Though it was spoken of as another of the Duke's "castles in the

air," and his resources were by no means overflowing at the time he

projected it,

he nevertheless determined to go on alone with it, should no one be

willing to join him. The Duke thus proved himself a real Dux or

leader of industrial enterprise in his district; and by cutting his

canal, and providing a

new, short, and cheap water-way between Liverpool and Manchester,

which was afterwards extended through the counties of Chester,

Stafford, and Warwick, he unquestionably paved the way for the

creation and

development of the modern manufacturing system existing in the

north-western counties of England.

We need scarcely say how admirably he was supported throughout by

the skill and indefatigable energy of his engineer. Brindley's

fertility in resources was the theme of general admiration. Arthur

Young, who visited

the works during their progress, speaks with enthusiastic admiration

of his "bold and decisive strokes of genius," his "penetration which

sees into futurity, and prevents obstructions unthought of by the

vulgar mind,

merely by foreseeing them: a man," says he, "with such ideas, moves

in a sphere that is to the rest of the world imaginary, or at best a

terra incognita."

It would be uninteresting to describe the works of the Bridgewater

Canal in detail; for one part of a canal is usually so like

another, that to do so were merely to involve a needless amount of

repetition of a necessarily

dry description. We shall accordingly content ourselves with

referring to the original methods by which Brindley contrived to

overcome the more important difficulties of the undertaking.

From Longford Bridge, where the new works commenced, the canal,

which was originally about eight yards wide and four feet deep, was

carried upon an embankment of about a mile in extent across the

valley of the

Mersey. One might naturally suppose that the conveyance of such a

mass of earth must have exclusively employed all the horses and

carts in the neighbourhood for years. But Brindley, with his usual

fertility in

expedients, contrived to make the construction of one part of the

canal subservient to the completion of the remainder. He had the

stuff required to make up the embankment brought in boats partly

from Worsley and

partly from other parts of the canal where the cutting was in excess; and the boats, filled with this stuff, were conducted from the

canal along which they had come into watertight caissons or cisterns

placed at the

point over which the earth and clay had to be deposited.

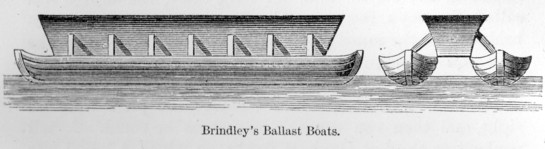

The boats, being double, fixed within two feet of each other, had a

triangular trough supported between them of sufficient capacity to

contain about seventeen tons of earth. The bottom of this trough

consisted of a line

of trap-doors, which flew open at once on a pin being drawn, and

discharged their whole burthen into the bed of the canal in an

instant. Thus the level of the embankment was raised

to the point necessary to enable the canal to be carried forward to

the next length. Arthur Young was of opinion that the saving

effected by constructing the Stretford embankment in this way,

instead of by carting the

stuff, was equivalent to not less than five thousand per cent.! The

materials of the caissons employed in executing this part of the

work were afterwards used in forming temporary locks across the

valley of the Bollin,

whilst the embankment was being constructed at that point by a

process almost the very reverse, but of equal ingenuity.

In the same valley of the Mersey the canal had to be carried over a

large brook subject to heavy floods, by means of a strong bridge of

two arches, adjoining which was a third, affording provision for a

road. Further on,

the canal was carried over the Mersey itself upon a bridge with one

arch of seventy feet span. Westward of this river lay a very

difficult part of the work, occasioned by the carrying of the

navigation over the Sale Moor

Moss. Many thought this an altogether impracticable thing; as not

only had the hollow trunk of earth in which the canal lay to be made

water-tight, but to preserve the level of the water-way it must

necessarily be

raised considerably above the level of the Moor across which it was

to be laid. Brindley overcame the difficulty in the following

manner. He made a strong casing of timber-work outside the intended

line of embankment

on either side of the canal, by placing deal balks in an erect

position, backing and supporting them on the outside with other

balks laid in rows, and fast screwed together; and on the front

side of this woodwork he had

his earth-work brought forward, hard rammed, and puddled, to form

the navigable canal; after which the casing was moved onward to the

part of the work further in advance, and the bottom having

previously been set with rubble and gravel, the embankment was thus

carried forward by degrees, the canal was raised to the proper

level, and the whole was substantially and satisfactorily finished.

A steam-engine of Brindley's contrivance was erected at Dunham Town

Bridge to pump the water from the foundations there. The engine was

called a Sawney, for what reason is not stated, and, for long after,

the

bridge was called Sawney's Bridge. The foundations of the

under-bridge, near the same place, were popularly supposed to be set

on quicksand; and old Lord Warrington, when he had occasion to pass

under it, would

pretend cautiously to look about him, as if to examine whether the

piers were all right, and then run through as fast as he could. A

tall poplar-tree stood at Dunham Banks, on which a board was nailed

showing the

height of the canal level; the people long after called the place

"The Duke's Folly," the name given to it while his scheme was still

believed to be impracticable. But the skill of the engineer baffled

these and other

prophets of evil; and the success of his expedients, in nearly

every case of difficulty that occurred, must certainly be regarded

as remarkable, considering the novel and unprecedented character of

the undertaking.

Brindley invariably contrived to economise labour as much as

possible, and many of his expedients with this object were very

ingenious. So far as he could, he endeavoured to make use of the

canal itself for the

purpose of forwarding the work. He had a floating blacksmith's forge

and shop, provided with all requisite appliances, fitted up in one

barge; a complete carpenter's shop in another; and a mason's shop

in a third; all of

which were floated on as the canal advanced, and were thus always at

hand to supply the requisite facilities for prosecuting the

operations with economy and despatch. Where there was a break in the

line of work, occasioned, for instance, by the erection of some

bridge not yet finished, the engineer had similar barges constructed

and carried by land to other lengths of the canal which were in

progress, where they were floated and advanced in like manner for

the use of the workmen. When the bridge across the Mersey, which

was pushed on as rapidly as possible with the object of economising

labour and cost of materials, was completed, the stone, lime, and

timber were brought along the canal from the Duke's property at

Worsley, as well as supplies of clay for the purpose of puddling the

bottom of the waterway; and thus the work rapidly advanced at all

points.

As one of the great objections made to the construction of the canal

had been the danger threatened to the surrounding districts by the

bursting of the embankments, Brindley made it his object to provide

against the

occurrence of such an accident by an ingenious expedient. He had

stops or flood-gates contrived and laid in various parts of the bed

of the canal, across its bottom, so that, in the event of a breach

occurring in the

bank and a rush of water taking place, the current which must

necessarily set in to that point should have the effect of

immediately raising the valvular floodgates, and so shutting off the

stream and preventing the

escape of more water than was contained in the division between the

two nearest gates on either side of the breach. At the same time,

these floodgates might be used for cutting off the waters of the

canal at different

points, for the purpose of making any necessary repairs in

particular lengths; the contrivance of waste tubes and plugs being

so arranged that the bed of any part of the canal, more especially

where it passed over the

bridges, might be laid bare in a few hours, and the repairs executed

at once.

In devising these ingenious expedients, it ought to be remembered

that Brindley had no previous experience to fall back upon, and

possessed no knowledge of the means which foreign engineers might

have adopted to

meet similar emergencies. All had been the result of his own

original thinking and contrivance; and, indeed, many of these

devices were altogether new and original, and had never before been

tried by any engineer.

It is curious to trace the progress of the works by Brindley's own

memoranda, which, though brief, clearly exhibit his marvellous

industry and close application to every detail of the business. He

settled with the farmers

for their tenant-right, sold and accounted for the wood cut down and

the gravel dug out along the line of the canal, paid the workmen

employed, [p.208] laid out the work, measured off the quantities

done from time to time, planned and erected the bridges, designed

the canal boats required for conveying the earth to form the

embankments, and united in himself the varied functions of

land-surveyor, carpenter, mason, brick-maker, boat-builder,

paymaster, and engineer. We even find him condescending to count

bricks and sell grass. Nothing was too small for him to attend to,

nor too bold for him to undertake, when necessity required. At the

same time we find him contriving a water-plane for the Duke's

collieries at Worsley, and occasionally visiting New-chapel, Leek,

and Congleton, in Staffordshire, for the purpose of attending to the

business on which he still continued to be employed at those places.

The heavy works at the crossing of the Mersey occupied him almost

exclusively towards the end of the year 1763. He was there making

dams and pushing on the building of the bridge. Occasionally he

enters the words, "short of men at Cornbrook." Indeed, he seems at

that time to have lived upon the works, for we find the almost daily

entry of "dined at the Bull, 8d." On the 10th of November he makes

this entry: "Aftor noon settled about the size of the arch over the

river Marsee [Mersey] to be 66 foot span and rise 16.4 feet." Next

day he is "landing balk out of the ould river in to the canal." Then

he goes on, "I prosceded to Worsley Mug was corking ye boats the

masons woss making the center of the waire [weir]. Whithe was osing

to put the lator side of the water-wheel srouds on I orderd the pit

for ye spindle of ye morter-mill to be sunk level with ye canal Mr.

Gilbert sade ye 20 Tun Boat should be at ye water mitang [meeting]

by 7 o'clock the next morn." Next morning he is on the works at

Cornhill, setting "a carpenter to make scrwos" [screws],

superintending the gravelling of the towing-path, and arranging

with a farmer as to Mr. Gilbert's slack. And so he goes on from day

to day with the minutest details of the undertaking.

He was not without his petty "werrets" and troubles either. Brindley

and Gilbert do not seem to have got on very well together. They were

both men of strong tempers, and neither would tolerate the other's

interference. Gilbert, being the Duke's factotum, was accustomed to call

Brindley's men from their work, which the other would not brook. Hence we have this entry on one occasion,—"A meshender [messenger]

from Mr G I retorned the anser No more society." In fact, they seem to have

quarrelled. [p.209]

We find the following further entries on the subject in Brindley's

note-book: "Thursday 17 Novr past 7 o'clock at night M Gilbert and

sun Tom caled on nice at Gorshill and I went with them to ye Coik

[sign of the Cock]

tha stade all night and the had balk [blank?] bill of parsill

18 Fryday November 7 morn I went to the Cock and Bruckfast with Gilberts

he in davred to imploye ye carpinters at Cornhill in making door and

window frames

for a Building in Castle field and shades for the mynors in Dito and

other things I want them to Saill Moor Hee took upon him diriction

of ye back drains and likwaise such Lands as be twixt the 2 hous and

ceep uper

side the large farme and was displesed with such raing as I had

pointed out."

Those differences between Brindley and Gilbert were eventually

reconciled, most probably by the mediation of the Duke, for the

services of both were alike essential to him; and we afterwards find

them working cordially

together and consulting each other as before on any important part

of the undertaking.

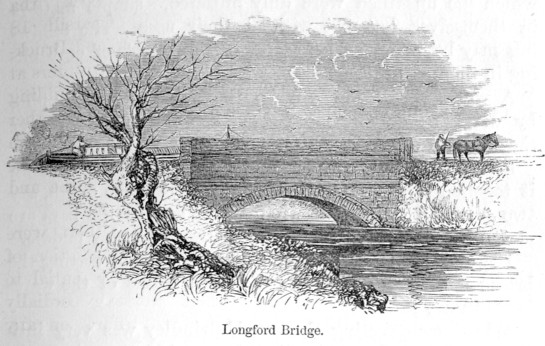

During the construction of Longford Bridge, Brindley seems, from his

note-book, to have entertained considerable apprehensions as to its

ability to resist the heavy floods with which it was threatened. Thus, on the 26th

of November, 1763, he enters:—"Grate Rains the canal rose 2 inches

extra I dreed fr [4?] clock at Longfoard;" and on the following

day, which was a Sunday, he writes:—"Lay in Bad till noon floode and

Raine." Then

in the afternoon he adds, "The water in Longfoord Brook was withe in

six inches of the high of the canter [centre] of ye waire [weir?]." The bridge, however, stood firm; and when the flood subsided, the

building was

again proceeded with; and by the end of the year it was finished

and gravelled over, while the embankment was steadily proceeding

beyond the Mersey in the manner above described.

Brindley did not want for good workmen to carry out his plans. He

found plenty of labourers in the neighbourhood accustomed to hard

work, who speedily became expert excavators; and though at first

there was a lack of skilled carpenters, blacksmiths, and

bricklayers, they soon became trained into such under the vigilant

eye of so able a master as Brindley was. We find him, in his

note-book, often referring to the men by their names, or rather

bye-names; for in Lancashire proper names seem to have been little

used at that time. "Black David" was one of the foremen most

employed on difficult matters, and "Bill o' Toms" and "Busick Jack,"

seem also to have been confidential workmen in their respective

departments. We are informed by a gentleman of the neighbourhood

[p.211] that most of the labourers employed were of a superior

class, and some of them were "wise" or "cunning men,"

blood-stoppers, herb-doctors, and planet-rulers, such as are still

to be found in the neighbourhood of Manchester. Their very

superstitions, says our informant, made them thinkers and

calculators. The foreman bricklayer, for instance, as his son used

afterwards to relate, always "ruled the planets to find out the

lucky days on which to commence any important work," and he added,

"none of our work ever gave way." The skilled men had their

trade-secrets, in which the unskilled were duly initiated,—simple

matters in themselves, but not without their uses. The following may

be taken as specimens of the secrets of embanking in those days:—

A wet embankment can be prevented from slipping by dredging or

dusting powdered lime in layers over the wet clay or earth.

Sand or gravel can be made water-tight by shaking it together with

flat bars of iron run in some depth, say two feet, and washing down

loam or soil as the bars are moved about, thus obviating the

necessity for clay

puddle.

Dry-rot can be prevented in warehouses by setting the bricks

opposite the ends of the main beams of the warehouse in dry sand.

Whilst constructing the canal, Brindley was very intimate with one Lawrence Earnshaw,

of Mottram-in-Longdendale, a kindred mechanical genius, though in a

smaller way. Lawrence was a very poor man's son, and had served a

seven years apprenticeship to the trade of a tailor, after which he

bound himself apprentice to a clothier for seven years; but these

trades not suiting his tastes, and being of a decidedly mechanical

turn, he finally bound himself apprentice to a clockmaker, whom he

also served for seven years. This eccentric person invented many

curious and ingenious machines, which were regarded as of great

merit in his time. One of these was an astronomical and geographical

machine, beautifully executed, showing the earth's diurnal and

annual motion, after the manner of an orrery. The whole of the

calculations were made by himself, and the machine is said to have

been so exactly contrived and executed that, provided the vibration of the pendulum did not vary, the machine would not alter a

minute in a hundred years; but this might probably be an extravagant

estimate on the part of Earnshawe's friends. He was also a musical

instrument maker and music teacher, a worker in metals and in wood,

a painter and glazier, an optician, a bellfounder, a chemist and

metallurgist, an engraver—in short, an almost universal mechanical

genius. But though he could make all these things, it is mentioned

as a remarkable fact, that with all his ingenuity, and after many

efforts (for he made many), he never could make a wicker-basket! Indeed, trying to

be a universal genius was his ruin. He did,

or attempted to do, so much, that he never stood still and

established himself in any one thing; and, notwithstanding his

great ability, he died "not worth a groat." Amongst Earnshaw's

various contrivances was a piece of machinery to raise water from a

coal-mine at Hague, near Mottram, and (about 1753) a machine to spin

and reel cotton at one operation—in fact, a spinning-jenny—which he

showed to some of his neighbours as a curiosity, but, after having

convinced them of what might be done by its means, he immediately

destroyed it, saying that "he would not be the means of taking bread

out of the mouths of the poor." [p.213] He was a total abstainer

from strong drink, long before the days of Teetotal Societies. Towards the end of his life he continued on intimate terms with

Brindley; and when they met they did not readily separate.

While the undertaking was in full progress, from four to six hundred

men were employed; they were divided into gangs of about fifty, each

of which was directed by a captain and setter-out of the works. One

who visited

the canal during its construction in 1765, wrote thus of the busy

scene which the works presented: "I surveyed the Duke's men for two

hours, and think the industry of bees or labour of ants is not to be

compared to them. Each man's work seems to depend on and be

connected with his neighbour's, and the whole posse appeared as I

conceive did that of the Tyrians when they wanted houses to put

their heads in at Carthage." [p.214-1] At Stretford the visitor

found "four hundred men at work, putting the finishing stroke to

about two hundred yards of the canal, which reached nearly to the

Mersey, and which, on drawing up the floodgates, was to receive a

proper quantity of water and a number of loaded barges. One of these

appeared like the hull of a collier, with its deck all covered,

after the manner of a cabin, and having an iron chimney in the

centre; this, on inquiry, proved to be the carpentry, but was shut

up, being Sabbath-day, as was another barge, which contained the

smith's forge. Some vessels were loaded with soil, which was put

into troughs (see cut, p.205), fastened together, and rested on

boards that lay across two barges; between each of these there was

room enough to discharge the loading by loosening some iron pins at

the bottom of the troughs. Other barges lay loaded with the

foundation-stones of the canal bridge, which is to carry the

navigation across the Mersey. Near two thousand oak piles are

already driven to strengthen the foundations of this bridge. The

carpenters on the Lancashire side were preparing the centre frame,

and on the Cheshire side all hands were at work in bringing down the

soil and beating the ground adjacent to the foundations of the

bridge, which is designed to be covered with stone in a month, and

finished in about ten days more." [p.214-2]

By these vigorous measures the works proceeded rapidly towards

completion. Before, however, they had made any progress at the

Liverpool end, Earl Gower, encouraged and assisted by the Duke, had

applied for and obtained an Act to enable a line of navigation to be

formed between the Mersey and the Trent; the Duke agreeing with the

promoters of the undertaking to vary the course of his canal and

meet theirs about midway between Preston-brook and Runcorn, from

which point it was to be carried northward towards the Mersey,

descending into that river by a flight of ten locks, the total fall

being not less than 79 feet from the level of the canal to low water

of spring-tides. |

Waterloo

Bridge, Runcorn. [p.214-3]

© Copyright

Stephen McKay and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

When this deviation was proposed, the bold imagination of Brindley

projected a bridge across the tideway of the Mersey itself, which

was there some four hundred and sixty yards wide, with the object of

carrying the

Duke's navigation directly onward to the port of Liverpool on the

Lancashire side of the river. [p.215] This was an admirable idea,

which, if carried out, would probably have redounded more to the

fame of Brindley than any other of his works. But the cost of that

portion of the canal which had already been executed, had reached so

excessive an amount, that the Duke was compelled to stop short at

Runcorn, at which place a dock was constructed for the accommodation

of the shipping employed in the trade connected with the

undertaking.

From Runcorn, it was arranged that the boats should navigate by the

open tideway of the Mersey to the harbour of Liverpool, at which

place the Duke made arrangements to provide another dock for their

accommodation. Brindley made frequent visits to Liverpool for the

purpose of directing its excavation, and he superintended it until

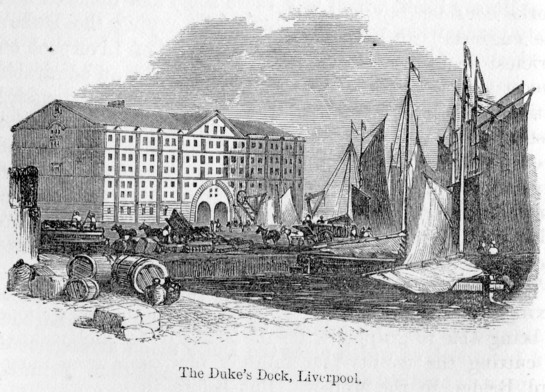

its completion. The Duke's Dock lies between the Salthouse and

Albert Docks on the north, and the Wapping and King's Docks on the

south. The Salthouse was the only public dock near it at the time

that Brindley excavated this basin. There were only three others in

Liverpool to the north, and not one to the south; but the Duke's

Dock is now the centre of about five miles of docks, extending from

it on either side along the Lancashire shore of the Mersey; and it

continues to this day to be devoted to the purposes of the

navigation. |

View west along

the line of the Duke's Dock. [p.216]

© Copyright

Eric Jones and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

――――♦――――

|

CHAPTER X.

THE DUKE'S DIFFICULTIES—COMPLETION OF THE CANAL—GROWTH OF

MANCHESTER.

LONG before the

Runcorn locks were constructed, and the canal from Longford Bridge

to the Mersey was available for purposes of traffic, the Duke found

himself reduced to the greatest straits for want of money. Numerous

unexpected difficulties had occurred, so that the cost of the works

considerably exceeded his calculations; and though the engineer

carried on the whole operations with the strictest regard to

economy, the expense was nevertheless almost more than any single

purse could bear. The execution of the original canal from Worsley

to Manchester cost about a thousand guineas a mile, besides the

outlay upon the terminus at Manchester. There was also the

expenditure incurred in building the requisite boats for the canal,

in opening out the underground workings of the collieries at

Worsley, and in erecting various mills, workshops, and warehouses

for carrying on the new business.

The Duke was enabled to do all this without severely taxing his

resources, and he even entertained the hope of being able to grapple

with the still greater undertaking of cutting the twenty-four miles

of new canal from Longford Bridge to the Mersey. But before these

works were half finished, and whilst the large amount of capital

invested in them was lying entirely unproductive, he found that the

difficulties of the undertaking were likely to prove too much for

him. Indeed, it seemed an enterprise beyond the means of any private

person, and more like that of a monarch with State revenues at his

command, than of a young English nobleman with only his private

resources.

But the Duke was possessed by a brave spirit.

He had put his hand to the work, and he would not look back.

He had become thoroughly inspired by his great idea, and determined

to bend his whole energies to the task of carrying it out. He

was only thirty years of age—the owner of several fine mansions in

different parts of the country, surrounded by noble domains—he had a

fortune sufficiently ample to enable him to command the pleasures

and luxuries of life, so far as money can secure them; yet he

voluntarily denied himself their enjoyment, and chose to devote his

time to consultations with an unlettered engineer, and his whole

resources to the cutting of a canal to unite Liverpool and

Manchester.

Taking up his residence at the Old Hall at Worsley—a fine

specimen of the old timbered houses so common in South Lancashire

and the neighbouring counties,—he cut down every unnecessary

personal expense; denied himself every superfluity, except perhaps

that of a pipe of tobacco; paid off his retinue of servants; put

down his carriages and town house; and confined himself and his

Ducal establishment to a total expenditure of £400 a-year. A

horse was, however, a necessity, for the purpose of enabling him to

visit the canal works during their progress at distant points; and

he accordingly continued to maintain one horse for himself and

another for his groom.

Notwithstanding this rigid economy, the Duke still found his

resources inadequate to meet the heavy cost of vigorously carrying

on the undertaking, and on Saturday nights he was often put to the

greatest shifts to raise the requisite money to pay his large staff

of craftsmen and labourers. Sometimes their payment had to be

postponed for a week or more, until the cash could be raised by

sending round for contributions among the Duke's tenantry.

Indeed, his credit fell to the lowest ebb, and at one time he could

not get a bill for £500 cashed in either Liverpool or Manchester. [p.219]

He was under the necessity of postponing all payments that

could be avoided, and it went abroad that the Duke was "drowned in

debt." He tried to shirk even the payment of his tithes, and

turned a deaf ear to all the applications of the collector. At

length the rector himself determined to waylay him. But the

Duke no sooner caught sight of him coming across his path than he

bolted! The rector was not thus to be baulked. He

followed—pursued—and fairly ran his debtor to earth in a saw-pit!

The Duke was not a little amused at being hunted in such a style by

his parson, and so soon as he found his breath, ho promised payment,

which shortly followed.

When Mr. George Rennie, the engineer, was engaged, in 1825,

in making the revised survey of the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway, he lunched one day at Worsley Hall with Mr. Bradshaw,

manager of the Duke's property, then a very old man. He had

been a contemporary of the Duke, and knew of the monetary straits to

which his Grace had been reduced during the construction of the

works. Whilst at table, Mr. Bradshaw pointed to a small

whitewashed cottage on the Moss, about a mile and a half distant,

and said that in that cottage, formerly a public- house, the Duke,

Brindley, and Gilbert had spent many an evening discussing the

prospects of the canal while in progress. One of the principal

topics of conversation on those occasions was the means of raising

funds against the next pay night. "One evening in particular,"

said Mr. Bradshaw, "the party was unusually dull and silent.

The Duke's ready-money was exhausted; the canal was not nearly

finished; his Grace's credit was at the lowest ebb; and he was at a

loss what step to take next. There they sat, in the small

parlour of the little public-house, smoking their pipes, with a

pitcher of ale before them, melancholy and silent. At last the

Duke broke the silence by asking in a querulous tone, 'Well,

Brindley, what's to be done now? How are we to get at the

money for finishing this canal?' Brindley, after a few long

puffs, answered through the smoke, 'Well, Duke, I can't tell; I only

know that if the money can be got, I can finish the canal, and that

it will pay well.' 'Ay,' rejoined the Duke, 'but where

are we to get the money?' Brindley could only repeat what he

had already said; and thus the little party remained in moody

silence for some time longer, when Brindley suddenly started up and

said, 'Don't mind, Duke; don't be cast down; we are sure to succeed

after all!' The party shortly after separated, the Duke going

over to Worsley to bed, to revolve in his mind the best mode of

raising money to complete his all-absorbing project."

One of the expedients adopted was to send Gilbert, the agent,

upon a round of visits among the Duke's tenants, raising five pounds

here and ten pounds there, until he had gathered together enough to

pay the week's wages. Whilst travelling about among the

farmers on one of such occasions, Gilbert was joined by a stranger

horseman, who entered into conversation with him; and it very

shortly turned upon the merits of their respective horses. The

stranger offered to swap with Gilbert, who, thinking the other's

horse better than his own, agreed to the exchange. On

afterwards alighting at a lonely village inn, which he had not

before frequented, Gilbert was surprised to be greeted by the

landlord with mysterious marks of recognition, and still more so

when he was asked if he had got a good booty. It turned out

that he had exchanged horses with a highwayman, who had adopted this

expedient for securing a nag less notorious than the one which he

had exchanged with the Duke's agent. [p.221]

At length, when the tenantry could furnish no further

advances, and loans were not to be had on any terms in Manchester or

Liverpool, and the works must needs come to a complete stand unless

money could be raised to pay the workmen, the Duke took the road to

London on horseback, attended only by his groom, to try what could

be done with his London bankers. The house of Messrs. Child

and Co., Temple Bar, was then the principal banking-house in the

metropolis, as it is the oldest; and most of the aristocratic

families kept their accounts there. The Duke had determined at

the outset of his undertaking not to mortgage his landed property,

and he had held to this resolution. But the time arrived when

he could not avoid borrowing money of his bankers on such other

security as he could offer them. He had already created a

valuable and lucrative property, which was happily available for the

purpose. The canal from Worsley to Manchester had proved

remunerative in an extraordinary degree, and was already producing a

large income. He had not the same scruples as to the pledging

of the revenues of his canal that he had to the mortgaging of his

lands; and an arrangement was concluded with the Messrs. Child under

which they agreed to advance the Duke sums of money from time to

time, by means of which he was eventually enabled to finish the

entire canal.

The Messrs. Child and Co. have kindly permitted an

examination of their books to be made for the purposes of this

memoir; and we are accordingly enabled to state that from them it

appears that the Duke obtained his first advance of £3,800 from the

firm about the middle of the year 1765, at which time he was in the

greatest difficulty; shortly after a further sum of £15,000; then

£2,000, and various other sums, making a total of £25,000; which

remained owing until the year 1769, when the whole was paid off—

doubtless from the profits of the canal traffic as well as the

economised rental of the Duke's unburthened estates.

The entire level length of the new canal from Longford Bridge

to the upper part of Runcorn, nearly twenty-eight miles in extent,

was finished and opened for traffic in the year 1767, after the

lapse of about five years from the passing of the Act. The

formidable flight of locks, from the level part of the canal down to

the waters of the Mersey at Runcorn, were not finished for several

years later, by which time the receipts derived by the Duke from the

sale of his coals and the local traffic of the undertaking enabled

him to complete them with comparatively little difficulty.

Considerable delay was occasioned by the resistance of an obstinate

landowner near Runcorn, Sir Richard Brooke, who interposed every

obstacle which it was in his power to offer; but his opposition too

was at length overcome, and the new and complete line of

water-communication between Manchester and Liverpool was finally

opened throughout.

In a letter written from Runcorn, dated the 1st January,

1773, we find it stated that "yesterday the locks were opened, and

the Heart of Oak, a vessel of 50 tons burden, for Liverpool,

passed through them. This day, upwards of six hundred of his Grace's

workmen were entertained upon the lock banks with an ox roasted

whole and plenty of good liquor. The Duke's health and many other

toasts were drunk with the loudest acclamations by the multitude,

who crowded from all parts of the country to be spectators of these

astonishing works. The gentlemen of the country for a long time

entertained a very unfavourable opinion of this undertaking,

esteeming it too difficult to be accomplished, and fearing their

lands would be cut and defaced without producing any real benefit to

themselves or the public; but they now see with pleasure that their

fears and apprehensions were ill-grounded, and they join with one

voice in applauding the work, which cannot fail to produce the most

beneficial consequences to the landed property, as well as to the

trade and commerce of this part of the kingdom."

Whilst the canal works had been in progress, great changes had taken

place at Worsley. The Duke had year by year been extending the

workings of the coal; and when the King of Denmark, travelling under

the title of Prince Travindahl, visited the Duke in 1768, the

tunnels had already been extended for nearly two miles under the

hill. When the Duke began the works, he possessed only such of the

coal-mines as belonged to the Worsley estate; but he purchased by

degrees the adjoining lands containing seams of coal which run under

the high ground between Worsley, Bolton, and Bury; and in course of

time the underground canals connecting the different workings

extended for a distance of nearly forty miles. Both the hereditary

and the purchased mines are worked upon two main levels, though in

all there are four different levels, the highest being a hundred and

twenty yards above the lowest. In opening up the underground

workings the Duke is said to have expended about £168,000; but the

immense revenue derived from the sale of the coals by canal rendered

this an exceedingly productive outlay. Besides the extension of the

canal along these tunnels, the Duke subsequently carried a branch by

the edge of Chat-Moss to Leigh, by which means new supplies of coal

were introduced to Manchester from that district, and the traffic

was still further increased. It was a saying of the Duke's, that

"a

navigation should always have coals at the heels of it."

The total cost of completing the canal from Worsley to Manchester,

and from Longford Bridge to the Mersey at Runcorn, amounted to

£220,000. A truly magnificent undertaking, nobly planned and nobly

executed. The power imparted by riches was probably never more

munificently exercised than in this case; for, though the traffic

proved a source of immense wealth to the Duke, it also conferred

incalculable blessings upon the population of the district. It added

much to their comforts, increased their employment, and facilitated

the operations of industry in all ways. As soon as the canal was

opened its advantages began to be felt. The charge for

water-carriage between Liverpool and Manchester was lowered

one-half. All sorts of produce were brought to the latter town, at

moderate rates, from the farms and gardens adjacent to the

navigation, whilst the value of agricultural property was

immediately raised by the facilities afforded for the conveyance of

lime and manure, as well as by reason of the more ready access to

good markets which it provided for the farming classes. The Earl of

Ellesmere has not less truly than elegantly observed, that "the

history of Francis Duke of Bridgewater is engraved in intaglio on

the face of the country he helped to civilize and enrich."

Probably the most remarkable circumstance connected with the money

history of the enterprise is this: that although the canal yielded

an income which eventually reached about £80,000 a year, it was

planned and executed by Brindley at a rate of pay considerably less

than that of an ordinary mechanic of the present day. The highest

wage he received whilst in the employment of the Duke was 3s. 6d. a

day. For the greater part of the time he received only half-a-crown. Brindley, no doubt, accommodated himself to the Duke's pinched

means, and the satisfactory completion of the canal was with him as

much a matter of disinterested ambition and of professional

character as of pay. He seems to have kept his own expenses down to

the very lowest point. Whilst superintending the works at Longford

Bridge, we find him making an entry for his day's personal charges

at only 6d. for "ating and drink." On other days his outgoings were

confined to "2d. for the turnpike." When living at the "Bull," near

the works at Throstle Nest, we find his dinner costing 8d, and his

breakfast 6d. His expenditure throughout was on an equally low scale

for he studied in all ways to economize the Duke's means, that every

available shilling might be devoted to the prosecution of the works.

The Earl of Bridgewater, in his singular publication, the 'Letter to

the Parisians,' above referred to, states that "Brindley offered to

stay entirely with the Duke, and do business for no one else, if he

would give him a guinea a week;" and this statement is repeated by

the late Earl of Ellesmere in his 'Essays on History, Biography,'

&c. But, on the face of it, the statement looks untrue; and we have

since found, from Brindley's own note-book, that on the 25th of May,

1762, he was receiving a guinea a day from the Earl of Warrington

for performing services for that nobleman; nor is it at all likely

that he would prefer the Duke's three-and-sixpence a day to the more

adequate rate of payment which he was accustomed to charge and to

receive from other employers. It is quite true, however—and the fact

is confirmed by Brindley's own record—that he received no more than

a guinea a week whilst in the Duke's service; which only affords an

illustration of the fact that eminent constructive genius may be

displayed and engineering greatness achieved in the absence of any

adequate material reward.

In a statement of the claims of Brindley's representatives,

forwarded to the Earl of Bridgewater on the 3rd of November, 1803,

it was stated that "during the period of his employ under His

Grace, many highly advantageous and lucrative offers were made to

him, particularly one from the Prince of Hesse, in 1766, who at that

time was meditating a canal through his dominions in Germany, and

who offered to subscribe to any terms Mr. Brindley might stipulate. To this engagement his family strongly urged him, but the

solicitation of the Duke, in this as in every other instance, to

remain with him, outweighed all pecuniary considerations; relying

upon such a remuneration from His Grace as the profits of his work

might afterwards justify." [p.227]

The inadequate character of his remuneration was doubtless well

enough known to Brindley himself, and rendered him very independent

in his bearing towards the Duke. They had frequent differences as to

the proper mode of carrying on the works; but Brindley was quite as

obstinate as the Duke on such occasions, and when he felt convinced

that his own plan was the right one he would not yield au inch. It

is said that, after long evening discussions at the hearth of the

old timbered hall at Worsley, or at the Duke's house at Liverpool,

while the works there were in progress the two would often part at

night almost at daggers-drawn. The next morning, on meeting at

breakfast, the Duke would very frankly say to his engineer, "Well,

Brindley, I have been thinking over what we were talking about last

night. I find you may be right after all; so just finish the work in

your own way."

The Duke himself, to the end of his life, took the greatest personal

interest in the working of his coal-mines, his canals, his mills,

and his various branches of industry. These were his hobbies, and he

took pleasure in nothing else. He was utterly lost to the