|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XI.

BRINDLEY CONSTRUCTS THE GRAND TRUNK CANAL.

LONG before the

Duke's Canal was finished, Brindley was actively employed in

carrying out a still larger enterprise,—a canal to connect the

Mersey with the Trent, and both with the Severn,—thus uniting by a

grand line of water-communication the ports of Liverpool, Hull, and

Bristol. He had, as we have already seen, made a survey of

such a canal, at the instance of Earl Gower, before his engagement

as engineer for the Bridgewater undertaking. Thus, in the

beginning of February, 1758, before the Duke's bill had been even

applied for, we find him occupied for days together "a bout the

novogation," and he then surveyed the country between Longbridge in

Staffordshire, and King's Mills in Derbyshire.

The enterprise, however, made very little progress. The

success of canals in England was as yet entirely problematical; and

this was of too formidable a character to be hastily undertaken.

But again, in 1759, we find Brindley proceeding with his survey of

the Staffordshire Canal; and in the middle of the following year he

was occupied about twenty days in levelling from Harecastle, at the

summit of the proposed canal, to Wilden, near Derby. During

that time he had many interviews with Earl Gower at Trentham, and

with the Earl of Stamford at Enville, discussing the project.

The next step taken was the holding of a public meeting at

Sandon, in Staffordshire, as to the proper course which the canal

should take, if finally decided upon. Considerable difference

of opinion was expressed at the meeting, in consequence of which it

was arranged that Mr. Smeaton should be called upon to co-operate

with Brindley in making a joint survey and a joint report.

A second meeting was held at Wolseley Bridge, at which the

plans of the two engineers were ordered to be engraved and

circulated amongst the landowners and others interested in the

project. Here the matter rested for several years more,

without any further action being taken. Brindley was hard at

work upon the Duke's Canal, and the Staffordshire projectors were

disposed to wait the issue of that experiment; but no sooner had it

been opened, and its extraordinary success become matter of fact,

than the project of the canal through Staffordshire was again

revived. The gentlemen of Cheshire and Staffordshire,

especially the salt manufacturers of the former county and the

earthenware-manufacturers of the latter, now determined to enter

into co-operation with the leading landowners in concerting the

necessary measures with the object of opening up a line of

water-communication with the Mersey and the Trent.

The earthenware manufacture, though in its infancy, had

already made considerable progress; but, like every other branch of

industry in England at that time, its further development was

greatly hampered by the wretched state of the roads.

Throughout Staffordshire they were as yet, for the most part,

narrow, deep, circuitous, miry, and inconvenient; barely passable

with rude waggons in summer, and almost impassable, even with

pack-horses, in winter. Yet the principal materials used in

the manufacture of pottery, especially of the best kinds, were

necessarily brought from a great distance —flint-stones from the

south-eastern ports of England, and clay from Devonshire and

Cornwall. The flints were brought by sea to Hull, and the clay

to Liverpool. From Hull the materials were brought up the

Trent in boats to Willington; and the clay was in like manner

brought from Liverpool up the Weaver to Winsford, in Cheshire.

Considerable quantities of clay were also conveyed in boats from

Bristol, up the Severn, to Bridgenorth and Bewdley. From these

various points the materials were conveyed by land-carriage, mostly

on the backs of horses, to the towns in the Potteries, where they

were worked up into earthenware and china.

The manufactured articles were returned for export in the

same rude way. Large crates of pot-ware were slung across

horses' backs, and thus conveyed to their respective ports, not only

at great risk of breakage and pilferage, but also at a heavy cost.

The expense of carriage was not less than a shilling a ton per mile,

and the lowest charge was eight shillings the ton for ten miles.

Besides, the navigation of the rivers above mentioned was most

uncertain, arising from floods in winter and droughts in summer.

The effect was, to prevent the expansion of the earthenware

manufacture, and very greatly to restrict the distribution of the

lower-priced articles in common use.

The same difficulty and cost of transport checked the growth

of nearly all other branches of industry, and made living both dear

and uncomfortable. The indispensable article of salt,

manufactured at the Cheshire Wiches, was in like manner carried on

horses' backs all over the country, and reached almost a fabulous

price by the time it was sold two or three counties off. About

a hundred and fifty pack-horses, in gangs, were occupied in going

weekly from Manchester, through Stafford, to Bewdley and

Bridgenorth, loaded with woollen and cotton cloth for exportation; [p.250]

but the cost of the carriage by this mode so enhanced the price,

that it is clear that in the case of many articles it must have

acted as a prohibition, and greatly checked both production and

consumption. Even corn, coal, lime, and iron-stone were

conveyed in the same way, and the operations of agriculture, as of

manufacture, were alike injuriously impeded. There were no

shops then in the Potteries, the people being supplied with wares

and drapery by packmen and hucksters, or from Newcastle-under-Lyne,

which was the only town in the neighbourhood worthy of the name.

The people of the district in question were quite as rough as

their roads. Their manners were coarse, and their amusements

brutal. Bull-baiting, cock-throwing, and goose-riding were

their favourite sports. When Wesley first visited Burslem, in

1760, the potters assembled to jeer and laugh at him. They

then proceeded to pelt him. "One of them," he says, "threw a

clod of earth which struck me on the side of the head; but it

neither disturbed me nor the congregation." At that time the

whole population of the Potteries did not amount to more than about

7,000 souls. The villages in which they lived were poor and

mean, scattered up and down, and the houses were mostly covered with

thatch. Hence the Rev. Mr. Middleton, incumbent of Stone—a man

of great shrewdness and quaintness, distinguished for his love of

harmless mirth and sarcastic humour—when enforcing the duty of

humility upon his leading parishioners, took the opportunity, on one

occasion, after the period of which we speak, of reminding them of

the indigence and obscurity from which they had risen to opulence

and respectability. He said they might be compared to so many

sparrows, for that all of them had been hatched under the thatch.

When the congregation of this gentleman, growing rich, bought an

organ and placed it in the church, he persisted in calling it the

hurdy-gurdy, and often took occasion to lament the loss of his old

psalm-singers.

The people towards the north were no better, nor were those

further south. When Wesley preached at Congleton, four years

later, he said, "even the poor potters [though they had pelted him]

are a more civilized people than the better sort (so called) at

Congleton." Arthur Young visited the neighbourhood of

Newcastle-under-Lyne in 1770, and found poor-rates high, wages low,

and employment scarce. "Idleness," said he, "is the chief

employment of the women and children. All drink tea, and fly

to the parishes for relief at the very time that even a woman for

washing is not to be had. By many accounts I received of the

poor in this neighbourhood, I apprehend the rates are burthened for

the spreading of laziness, drunkenness, tea-drinking, and

debauchery,—the general effect of them, indeed, all over the

kingdom." [p.252-1]

Hutton's account of the population inhabiting the southern

portion of the same county is even more dismal. Between Hales

Owen and Stourbridge was a district usually called the Lie Waste,

and sometimes the Mud City. Houses stood about in every

direction, composed of clay scooped out into a tenement, hardened by

the sun, and often destroyed by the frost. The males were

half-naked, the children dirty and hung over with rags. "One

might as well look for the moon in a coal-pit," says Hutton, "as for

stays or white linen in the City of Mud. The principal tool in

business is the hammer, and the beast of burden the ass." [p.252-2]

The district, however, was not without its sprinkling of

public-spirited men who were actively engaged in devising new

sources of employment for the population; and, as one of the most

effective means of accomplishing this object, opening up the

communications, by road and canal, with near as well as distant

parts of the country. One of the most zealous of such workers

was the illustrious Josiah Wedgwood. He was one of those

indefatigable men who from time to time spring from the ranks of the

common people, and by their energy, skill, and enterprise, not only

practically educate the working population in habits of industry,

but, by the example of diligence and perseverance which they set

before them, largely influence public action in all directions, and

contribute in a great measure to form the national character.

Josiah Wedgwood was born in a humble position in life; and

though he rose to eminence as a man of science as well as a

manufacturer, he possessed no greater advantages at starting than

Brindley himself did. His grandfather and granduncle were both

potters, as was also his father Thomas, who died when Josiah was a

mere boy, the youngest of a family of thirteen children. He

began his industrial life as a thrower in a small pot-work,

conducted by his elder brother; and he might have continued working

at the wheel but for an attack of virulent small-pox, which, being

neglected, led to a disease in his right leg, which in a great

measure unfitted him for following even that humble employment.

When he returned to his work, most probably before he was

sufficiently recovered from his illness, the pain in his limb was

such that he had to keep it almost constantly rested upon a stool

before him. [p.253] The

disease continued increasing as he advanced in years, and it was

greatly aggravated by an unfortunate bruise, which kept him to his

bed for months, and reduced him to the last extremity of debility.

At length the disorder reached the knee, and threatened to endanger

his life, when amputation was found necessary. During the

enforced leisure of his many illnesses arising from this cause,

Wedgwood took to reading and thinking, and turned over in his mind

the various ways of making a living by his trade, now that he could

no longer work at the potter's wheel. It has been no less

elegantly than truthfully observed by Mr. Gladstone, that

"it is not often that we have such palpable occasion

to record our obligations to the small-pox. But in the

wonderful ways of Providence, that disease, which came to him as a

twofold scourge, was probably the occasion of his subsequent

excellence. It prevented him from growing up to be the active,

vigorous English workman, possessed of all his limbs, and knowing

right well the use of them; but it put him upon considering whether,

as he could not be that, he might not be something else, and

something greater. It sent his mind inwards; it drove him to

meditate upon the laws and secrets of his art. The result was,

that he arrived at a perception and a grasp of them which might,

perhaps, have been envied, certainly have been owned, by an Athenian

potter." [p.254]

[p.255]

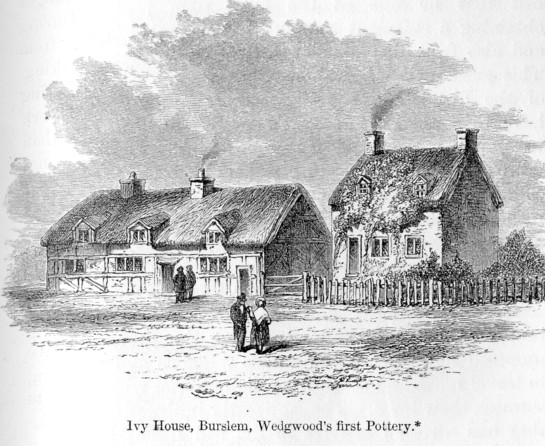

Wedgwood began operations on his own account by making

various ornamental objects out of potter's clay, such as

knife-hafts, boxes, and sundry curious little articles for domestic

use. He joined in several successive partnerships with other

workmen, but made comparatively small progress until he began

business for himself, in 1759, in a humble cottage near the Market

House in Burslem, known by the name of the Ivy House. He there

pursued his manufacture of knife-handles and wares, other small

wares, striving at the same time to acquire such a knowledge of

practical chemistry as might enable him to improve the quality of

his work in respect of colour, glaze, and durability. Success

attended Wedgwood's diligent and persistent efforts, and he

proceeded from one stage of improvement to another, until at length,

after a course of about thirty years' labour, he firmly established

a new branch of industry, which not only added greatly to the

conveniences of domestic life, but proved a source of remunerative

employment to many thousand families throughout England.

His trade having begun to expand, an extensive demand for his

articles sprang up, not only in London, but in foreign countries. [p.256]

But there was this great difficulty in his way, that the roads in

his neighbourhood were so bad that he was at the same time prevented

from obtaining a sufficient supply of the best kinds of clay and

also from disposing of his wares in distant markets. This

great evil weighed heavily upon the whole industry of the district,

and Wedgwood accordingly appears to have bestirred himself at an

early period in his career to improve the local communications.

In conjunction with several of the leading potters he promoted an

application to Parliament for powers to repair and widen the road

from the Red Bull, at Lawton, in Cheshire, to Cliff Bank, in

Staffordshire. This line, if formed, would run right through

the centre of the Potteries, open them to traffic, and fall at

either end into a turnpike road.

The measure was, however, violently opposed by the people of

Newcastle-under-Lyne, on the ground that the proposed new road would

enable waggons and packhorses to travel north and south from the

Potteries without passing through their town. The Newcastle

innkeepers acted as if they had a vested interest in the bad roads;

but the bill passed, and the new line was made, stopping short at

Burslem. This was, no doubt, a great advantage, but it was not

enough. The heavy carriage of clay, coal, and earthenware

needed some more convenient means of transport than waggons and

roads; and, when the subject of water communication came to be

discussed, Josiah Wedgwood at once saw that a canal was the very

thing for the Potteries. Hence he immediately entered with

great spirit into the movement again set on foot for the

construction of Brindley's Grand Trunk Canal.

The field was not, however, so clear now as it had been

before. The success of the Duke's canal led to the projection

of a host of competing schemes in the county of Chester, and it

appeared that Brindley's Grand Trunk project would have to run the

gauntlet of a powerful local opposition. There were two other

schemes besides his, which formed the subject of much pamphleteering

and controversy at the time, one entering the district by the river

Weaver, and another by the Dee. Neither of these proposed to

join the Duke of Bridgewater's canal, whereas the Grand Trunk line

was laid out so as to run into his at Preston-on-the-Hill near

Runcorn. As the Duke was desirous of placing his

navigation—and through it Manchester, Liverpool, and the intervening

districts—in connection with the Cheshire Wiches and the

Staffordshire Potteries, he at once threw the whole weight of his

support upon the side of Brindley's Grand Trunk. Indeed, he

had himself been partly at the expense of its preliminary survey, as

we find from an entry in Brindley's memorandum-book, under date the

12th of April, 1762, as follows: "Worsley—Recd from Mr Tho Gilbert

for ye Staffordshire survey, on account, £33 16s. 11d."

Josiah Wedgwood. [p.258]

© Copyright

Stephen McKay and licensed for reuse

under this

Creative Commons Licence.

The Cheshire gentlemen protested against the Grand Trunk

scheme, as calculated to place a monopoly of the Staffordshire and

Cheshire traffic in the hands of the Duke; but they concealed the

fact, that the adoption of their respective measures would have

established a similar monopoly in the hands of the Weaver Canal

Company, whose line of navigation, so far as it went, was tedious,

irregular, and expensive. Both parties mustered their forces

for a Parliamentary struggle, and Brindley exerted himself at

Manchester and Liverpool in obtaining support and evidence on behalf

of his plan. The following letter from him to Gilbert, then at

Worsley, relates to the rival schemes.

"21 Decr. 1765

"On Tusdey Sr Georg [Warren] sent Nuton in to Manchester to

make what intrest he could for Sir Georg and to gather ye old

Navogtors togather to meet Sir Georg at Stoperd to make Head a ganst

His Grace

"I sawe Docter Seswige who sese Hee wants to see you about

pamant of His Land in Cheshire

"On Wednesday ther was not much transpired but was so dark I

could carse do aneything

"On Thursdey Wadgwood of Burslam came to Dunham & sant for

mee and wee dined with Lord Gree [Grey] & Sir Hare Mainwering and

others Sir Hare cud not ceep His Tamer [temper] Mr.

Wedgwood came to seliset Lord Gree in faver of the Staffordshire

Canal & stade at Mrs Latoune all night & I whith him & on frydey sat

out to wate on Mr Edgerton to seliset Him Hee sase Sparrow and

others are indavering to gat ye Land owners consants from Hare

Castle to Agden

"I have ordered Simcock to ye Langth falls of Sanke

Navegacion.

"Ryle wants to have coals sant faster to Alteringham that Hee

may have an opertunety dray of ye sale Moor Canal in a bout a weeks

time.

"I in tend being back on Tusdy at fardest."

The first public movement was made by the supporters of

Brindley's scheme. They held an open meeting at Wolseley

Bridge, Staffordshire, on the 30th of December, 1765, at which the

subject was fully discussed. Earl Gower, the lord-lieutenant

of the county, occupied the chair; and Lord Grey and Mr. Bagot,

members for the county,—Mr. Anson, member for Lichfield, Mr. Thomas

Gilbert, the agent for Earl Gower, then member for

Newcastle-under-Lyne,—Mr. Wedgwood, and many other influential

gentlemen, were present to take part in the proceedings. Mr.

Brindley was called upon to explain his plans, which he did to the

satisfaction of the meeting; and these having been adopted, with a

few immaterial alterations, it was determined that steps should be

taken to apply for a bill conferring the necessary powers in the

next session of Parliament. Mr. Wedgwood put his name down for

a thousand pounds towards the preliminary expenses, and promised to

subscribe largely for shares besides. [p.260]

The promoters of the measure proposed to designate the undertaking

"The Canal from the Trent to the Mersey;" but Brindley, with

sagacious foresight, urged that it should be called The Grand Trunk,

because, in his judgment, numerous other canals would branch out

from it at various points of its course, in like manner as the

arteries of the human system branch out from the aorta; and before

many years had passed, his anticipations in this respect were fully

realized. The Staffordshire potters were greatly pleased with

the decision of the meeting, and on the following evening they

assembled round a large bonfire at Burslem, and drank the healths of

Lord Gower, Mr. Gilbert, and the other promoters of the scheme, with

fervent demonstrations of joy.

The opponents of the measure also held meetings, at which

they strongly declaimed against the Duke's proposed monopoly, and

set forth the superior merits of their respective schemes. One

of these was a canal from the river Weaver, by Nantwich, Eccleshall,

and Stafford, to the Trent at Wilden Ferry, without touching the

Potteries at all. Another was for a canal from the Weaver at

Northwich, passing by Macclesfield and Stockport, round to

Manchester, thus completely surrounding the Duke's navigation, and

preventing its extension southward into Staffordshire or any other

part of the Midland districts.

But there was also a strong party opposed to all canals

whatever—the party of croakers, who are always found in opposition

to improved communications, whether in the shape of turnpike roads,

canals, or railways. They prophesied that if the proposed

canals were made, the country would be ruined, the breed of English

horses would be destroyed, the innkeepers would be made bankrupts,

and the pack-horses and their drivers would be deprived of their

subsistence. It was even said that the canals, by putting a

stop to the coasting trade, would destroy the race of seamen.

It is a fortunate thing for England that it has contrived to survive

these repeated prophecies of ruin. But the manner in which our

countrymen contrive to grumble their way along the high road of

enterprise, thriving and grumbling, is one of the peculiar features

in our character which perhaps only Englishmen can understand and

appreciate.

It is a curious illustration of the timidity with which the

projectors of those days entered upon canal enterprise, that one of

their most able advocates, in order to mitigate the opposition of

the pack-horse and waggon interest, proposed that "no main trunk of

a canal should be carried nearer than within four miles of any great

manufacturing and trading town; which distance from the canal would

be, sufficient to maintain the same number of carriers and to employ

almost the same number of horses as before." [p.261]

But as none of the towns in the Potteries were as yet large

manufacturing or trading places, this objection did not apply to

them, nor prevent the canals from being carried quite through the

centre of what has since become a continuous district of populous

manufacturing towns and villages. The vested interests of some

of the larger towns were, however, for this reason, preserved,

greatly to their own ultimate injury; and when the canal, to

conciliate the local opposition, was so laid out as to leave them at

a distance, not many years elapsed before they became clamorous for

branches to join the main trunk— but not until the mischief had been

done, and a blow dealt to their own trade, in consequence of their

being left so far outside the main line of water communication, from

which many of them never after recovered.

It is not necessary to describe the Parliamentary contest

upon the Grand Trunk Canal Bill. There was the usual muster of

hostile interests,—the river navigation companies uniting to oppose

the new and rival company—the array of witnesses on both

sides,—Brindley, Wedgwood, Gilbert, and many more, giving their

evidence in support of their own scheme, and a powerful array of the

Cheshire gentry and Weaver Navigation Trustees appearing on behalf

of the others,—and the whipping-up of votes, in which the Duke of

Bridgewater and Earl Gower worked their influence with the Whig

party to good purpose.

Brindley's plan was, on the whole, considered the best.

It was the longest and the most circuitous, but it appeared

calculated to afford the largest amount of accommodation to the

public. It would pass through important districts, urgently in

need of an improved communication with the port of Liverpool on the

one hand, and with Hull on the other. But it was not so much

the connection of those ports with each other that was needed, as a

more convenient means of communication between them and the

Staffordshire manufacturing districts; and the Grand Trunk

system—somewhat in the form of a horse-shoe, with the Potteries

lying along its extreme convex part—promised effectually to answer

this purpose, and to open up a ready means of access to the coast on

both sides of the island.

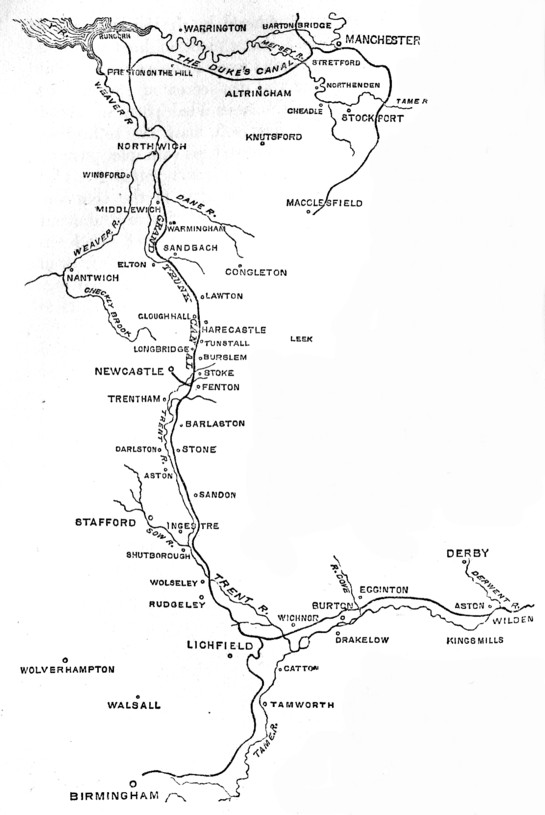

A glance at the course of the proposed line will show its

great importance. Starting from the Duke's canal at

Preston-on-the-Hill, near Runcorn, it passed southwards by Northwich

and Middlewich, through the great salt-manufacturing districts of

Cheshire, to the summit at Harecastle. It was alleged that the

difficulties presented by the long tunnel at that point were so

great that it could never be the intention of the projectors of the

canal to carry their "chimerical idea," as it was called, into

effect. Brindley however insisted, not only that the tunnel

was practicable, but that, if the necessary powers were granted, he

would certainly execute it. [p.263]

Descending from the summit level into the valley of the Trent, the

canal proceeded southwards through the Pottery districts, passing

close to Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, and Lane End. It then passed

onward, still south, by Trentham, Stone, and Shutborough, to

Haywood, where it joined the canal projected to unite the Severn

with the Mersey. Still following the valley of the Trent, the

canal near Rugeley, turning sharp round, proceeded in a

north-easterly direction, nearly parallel with the river, passing

Burton and Ashton, to a junction with the main stream at Wilden

Ferry, a little above where the Derwent falls into the Trent near

Derby. From thence there was a clear line of navigation, by

Nottingham, Newark, and Gainsborough, to the Humber. Provided

this admirable project could be carried out, it appeared likely to

meet all the necessities of the case. Ample evidence was given

in support of the allegations of its promoters; and the result was,

that Parliament threw out the bills promoted by the Cheshire

gentlemen on behalf of the old river navigation interest, and the

Grand Trunk Canal Act passed into law. At the same time

another important Act was passed, empowering the construction of the

Wolverhampton Canal, from the river Severn, near Bewdley, to the

river Trent, near Haywood Mill; thus uniting the navigation of the

three rivers which had their termini at the ports of Liverpool,

Hull, and Bristol, on the opposite sides of the island.

There was great rejoicing at Burslem on the news arriving at

that place of the passing of the bill; and very shortly after, on

the 26th of July, 1766, the works were formally commenced by Josiah

Wedgwood on the declivity of Bramhills, in a piece of land within a

few yards of the bridge which crosses the canal at that place.

Brindley was present at the ceremony, when due honours were paid him

by the assembled potters. After Mr. Wedgwood had cut the first

sod, many of the leading persons of the neighbourhood followed his

example, putting their hand to the work by turns, and each cutting a

turf or wheeling a barrow of earth in honour of the occasion.

It was, indeed, a great day for the Potteries, as the event proved.

In the afternoon a sheep was roasted whole in Burslem market-place,

for the good of the poorer class of potters; a feu de joie

was fired in front of Mr. Wedgwood's house, and sundry other

demonstrations of local rejoicing wound up the day's proceedings.

Wedgwood was of all others the most strongly impressed with

the advantages of the proposed canal. He knew and felt how

much his trade had been hindered by the defective communications of

the neighbourhood, and to what extent it might be increased provided

a ready means of transit to Liverpool, Hull, and Bristol could be

secured; and, confident in the accuracy of his anticipations, he

proceeded to make the purchase of a considerable estate in Shelton,

intersected by the canal, on the banks of which he built the

celebrated Etruria—the finest manufactory of the kind up to that

time erected in England, alongside of which he built a mansion for

himself and cottages for his workpeople. He removed his works

thither from Burslem, partially in 1769, and wholly in 1771, shortly

before the works of the canal had been completed.

The Grand Trunk was the most formidable undertaking of the

kind that had yet been attempted in England. Its whole length,

including the junctions with the Birmingham Canal and the river

Severn, was 139½ miles. In conformity with Brindley's

practice, he laid out as much of the navigation as possible upon a

level, concentrating the locks in this case at the summit, near

Harecastle, from which point the waters fell in both directions,

north and south. Brindley's liking for long flat reaches of

dead water made him keep clear of rivers as much as possible.

He likened water in a river flowing down a declivity, to a furious

giant running along and overturning everything; whereas (said he)

"if you lay the giant flat upon his back, he loses all his force,

and becomes completely passive, whatever his size may be."

Hence he contrived that from Middlewich, a distance of seventeen

miles, to the Duke's Canal at Preston Brook, there should not be a

lock; but goods might be conveyed from the centre of Cheshire to

Manchester, for a distance of about seventy miles, along one uniform

water level. He carried out the same practice, in like manner,

on the Trent side of Harecastle, where he laid out the canal in as

many long lengths of dead water as possible.

The whole rise of the canal from the level of the Mersey,

including the Duke's locks at Runcorn, to the summit at Harecastle,

is 395 feet; and the fall from thence to the Trent at Wilden is 288

feet 8 inches. The locks of the Grand Trunk proper, on the

northern side of Harecastle, are thirty-five, and on the southern

side forty. The dimensions of the canal, as originally

constructed, were twenty-eight feet in breadth at the top, sixteen

at the bottom, and four and a half feet in depth; but from Wilden to

Burton, and from Middlewich to Preston-on-the-Hill, it was

thirty-one feet broad at the top, eighteen at the bottom, and five

and a half feet deep, so as to be navigable by large barges; and the

locks at those parts of the canal were of correspondingly large

dimensions. The width was afterwards made uniform throughout.

The canal was carried over the river Dove on an aqueduct of

twenty-three arches, approached by an embankment on either side—in

all a mile and two furlongs in length. There were also

aqueducts over the Trent, which it crosses at four different

points—one of these being of six arches of twenty-one feet span

each—and over the Dane and other smaller streams. The number

of minor aqueducts was about 160, and of road-bridges 109. |

Dove Aqueduct: crossing the River Dove, Trent & Mersey Canal. [p.266]

© Copyright

Alan Murray-Rust and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

Croxton Aqueduct: crossing the River Dane, Trent & Mersey Canal.

© Copyright

Mike W Hallett and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

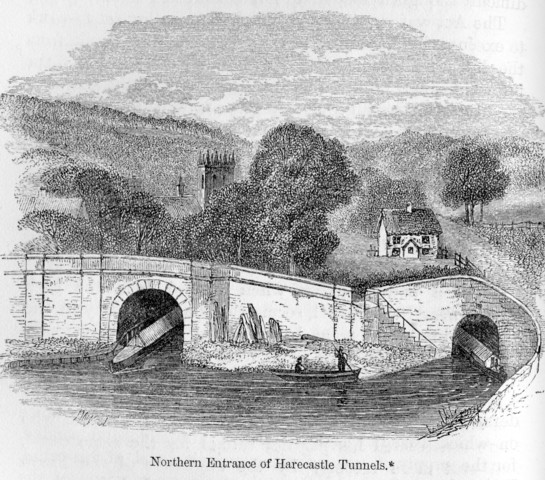

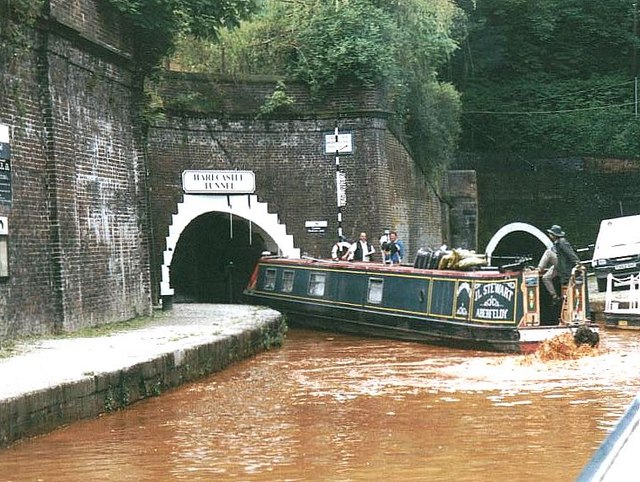

But the most formidable works on the canal were the tunnels,

of which there were five—the Harecastle, 2,880 yards long; the

Hermitage, 120 yards; the Barnton, 560 yards; the Saltenford, 350

yards; and the Preston-on-the Hill, 1,241 yards. The

Harecastle tunnel (subsequently duplicated by Telford) was

constructed only nine feet wide and twelve feet high; [p.267]

but the others were seventeen feet four inches high, and thirteen

feet six inches wide. The most extensive ridge of country to

be penetrated was at Harecastle, involving by far the most difficult

work in the whole undertaking. This ridge is but a

continuation of the high ground, forming what is called the

"back-bone of England," which extends in a south-westerly direction

from the Yorkshire mountains to the Wrekin in Shropshire. The

flat county of Cheshire, which looks almost as level as a

bowling-green when viewed from the high ground near New Chapel,

seems to form a deep bay in the land, its innermost point being

almost immediately under the village of Harecastle; and from thence

to the valley of the Trent the ridge is at the narrowest. That

Brindley was correct in determining to form his tunnel at this point

has since been confirmed by the survey of Telford, who there

constructed his parallel tunnel for the same canal, and still more

recently by the engineers of the North Staffordshire Railway, who

have also formed their railway tunnel almost parallel with the line

of both canals.

When Brindley proposed to cut a navigable way under this

ridge, it was declared to be chimerical in the extreme. The

defeated promoters of the rival projects continued to make war upon

it in pamphlets, and in the exasperating language of mock sympathy

proclaimed Brindley's proposed tunnel to be "a sad misfortune," [p.268-2]

inasmuch as it would utterly waste the capital raised by the

subscribers, and end in the inevitable ruin of the concern.

Some of the small local wits spoke of it as another of Brindley's,

"Air Castles;" but the allusion was not a happy one, as his first

"castle in the air," despite all prophecies to the contrary, had

been built, and continued to stand firm at Barton; and judging by

the issue of that undertaking, it was reasonable to infer that he

might equally succeed in this, difficult though it was on all hands

admitted to be.

[268-1]

The Act was no sooner passed than Brindley set to work to

execute the impossible tunnel. Shafts were sunk from the

hill-top at different points down to the level of the intended

canal. The stuff was drawn out of the shafts in the usual way

by horse-gins; and so long as the water was met with in but small

quantities, the power of windmills and watermills working pumps over

each shaft was sufficient to keep the excavators at work. But

as the miners descended and cut through the various strata of the

hill on their downward progress, water was met with in vast

quantities; and here Brindley's skill in pumping machinery proved of

great value. The miners were often drowned out, and as often

set to work again by his mechanical skill in raising water. He

had a fire-engine, or atmospheric steam-engine; of the best

construction possible at that time, erected on the top of the hill,

by the action of which great volumes of water were pumped out night

and day.

This abundance of water, though it was a serious hinderance

to the execution of the work, was a circumstance on which Brindley

had calculated, and indeed depended, for the supply of water for the

summit level of his canal. When the shafts had been sunk to

the proper line of the intended waterway, the excavation then

proceeded in opposite directions, to meet the other driftways which

were in progress. The work was also carried forward at both

ends of the tunnel, and the whole line of excavation was at length

united by a continuous driftway—it is true, after long and expensive

labour—when the water ran freely out at both ends, and the pumping

apparatus on the hilltop was no longer needed. At a general

meeting of the Company, held on the 1st October, 1768, after the

works had been in progress about two years, it appeared from the

report of the Committee that four hundred and nine yards of the

tunnel were cut and vaulted, besides the vast excavations at either

end for the purpose of reservoirs; and the Committee expressed their

opinion that the work would be finished without difficulty. |

Harecastle

Tunnels — North Entrances. [p.269]

© Copyright

Maurice Pullin and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

Active operations had also been in progress at other parts of

the canal. About six hundred men in all were employed, and

Brindley went from point to point superintending and directing their

labours. A Burslem correspondent, in September, 1767, wrote to

a distant friend thus:—

"Gentlemen come to view our eighth wonder of the

world, the subterraneous navigation, which is cutting by the great

Mr. Brindley, who handles rocks as easily as you would plum-pies,

and makes the four elements subservient to his will. He is as

plain a looking man as one of the boors of the Peak, or as one of

his own carters; but when he speaks, all ears listen, and every mind

is filled with wonder at the things he pronounces to be practicable.

He has cut a mile through bogs, which he binds up, embanking them

with stones which he gets out of other parts of the navigation,

besides about a quarter of a mile into the hill Yelden, on the side

of which he has a pump worked by water, and a stove, the fire of

which sucks through a pipe the damps that would annoy the men who

are cutting towards the Centre of the hill. The clay he cuts

out serves for bricks to arch the subterraneous part, which we

heartily wish to see finished to Wilden Ferry, when we shall be able

to send Coals and Pots to London, and to different parts of the

globe."

In the course of the first two years' operations, twenty-two

miles of the navigation had been cut and finished, and it was

expected that before eighteen months more had elapsed the canal

would be ready for traffic by water between the Potteries and Hull

on the one hand, and Bristol on the other. It was also

expected that by the same time the canal would be ready for traffic

from the north end of Harecastle Tunnel to the river Mersey.

The execution of the tunnel, however, proved so tedious and

difficult, and the excavation and building went on so slowly, that

the Committee could not promise that it would be finished in less

than five years from that time. As it was, the completion of

the Harecastle Tunnel occupied nine years more; and it was not

finished until the year 1777, by which time the great engineer had

finally rested from all his labours.

It is scarcely necessary to describe the benefits which the

canal conferred upon the inhabitants of the districts through which

it passed. As we have already seen, Staffordshire and the

adjoining counties had been inaccessible during the chief part of

each year. The great natural wealth which they contained was

of little value, because it could with difficulty be got at; and

even when reached, there was still greater difficulty in

distributing it. Coal could not be worked at a profit, the

price of land-carriage so much restricting its use, that it was

placed altogether beyond the reach of the great body of consumers.

It is difficult now to realise the condition of poor people

situated in remote districts of England less than a century ago.

In winter time they shivered over scanty wood-fires, for timber was

almost as scarce and as dear as coal. Fuel was burnt only at

cooking times, or to cast a glow about the hearth in the winter

evenings. The fireplaces were little apartments of themselves,

sufficiently capacious to enable the whole family to sit within the

wide chimney, where they listened to stories or related to each

other the events of the day. Fortunate were the villagers who

lived hard by a bog or a moor, from which they could cut peat or

turf at will. They ran all risks of ague and fever in summer,

for the sake of the ready fuel in winter. But in places remote

from bogs, and scantily timbered, existence was scarcely possible;

and hence the settlement and cultivation of the country were in no

slight degree retarded until comparatively recent times, when better

communications were opened up.

When the canals were made, and enabled coals to be readily

conveyed along them at comparatively moderate rates, the results

were immediately felt in the increased comfort of the people.

Employment became more abundant, and industry sprang up in their

neighbourhood in all directions. The Duke's canal, as we have

seen, gave the first great impetus to the industry of Manchester and

that district. The Grand Trunk had precisely the same effect

throughout the Pottery and other districts of Staffordshire; and

their joint action was not only to employ, but actually to civilize

the people. The salt of Cheshire could now be manufactured in

immense quantities, readily conveyed away, and sold at a

comparatively moderate price in all the midland districts of

England. The potters of Burslem and Stoke, by the same mode of

conveyance, received their gypsum from Northwich, their clay and

flints from the seaports now directly connected with the canal, and

returned their manufactures by the same route. The carriage of

all articles being reduced to about one-fourth of their previous

rates, [p.272] articles of

necessity and comfort, such as had formerly been unknown except

amongst the wealthier classes, came into common use amongst the

people. Employment increased, and the difficulties of

subsistence diminished. Led by the enterprise of Wedgwood and

others like him, new branches of industry sprang up, and the

manufacture of earthenware, instead of being insignificant and

comparatively unprofitable, which it was before his time, became a

staple branch of English trade. Only about ten years after the

Grand Trunk Canal had been opened, Wedgwood stated in evidence

before the House of Commons, that from 15,000 to 20,000 persons were

then employed in the earthenware-manufacture alone, besides the

large number of labourers employed in digging coals for their use,

and the still larger number occupied in providing materials at

distant parts, and in the carrying and distributing trade by land

and sea. The annual import of clay and flints into

Staffordshire at that time was from fifty to sixty thousand tons;

and yet, as Wedgwood truly predicted, the trade was but in its

infancy. The tonnage outwards and inwards at the Potteries is

now upwards of three hundred thousand tons a-year. |

Dudson Pottery, Hanley [p.273-1]

© Copyright

Steven Birks and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

Bottle Kiln at Dudson Pottery, Hanley.

© Copyright

Steven Birks and licensed for reuse

under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

The moral and social influences exercised by the canals upon

the Pottery districts were not less remarkable. From a

half-savage, thinly-peopled district of some 7,000 persons in 1760,

partially employed and ill-remunerated, we find them increased, in

the course of some twenty-five years, to about treble the

population, abundantly employed, prosperous, and comfortable. [p.273-2]

Civilization is doubtless a plant of very slow growth, and does not

necessarily accompany the rapid increase of wealth. On the

contrary, higher earnings, without improved morale, may only lead to

wild waste and gross indulgence. But the testimony of Wesley

to the improved character of the population of the Pottery district

in 1781, within a few years after the opening of Brindley's Grand

Trunk Canal, is so remarkable, that we cannot do better than quote

it here; and the more so, as we have already given the account of

his first visit in 1760, on the occasion of his being pelted.

"I returned to Burslem," says Wesley; "how is the whole face of the

country changed in about twenty years! Since which,

inhabitants have continually flowed in from every side. Hence

the wilderness is literally become a fruitful field. Houses,

villages, towns, have sprung up, and the country is not more

improved than the people."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XII.

BRINDLEY'S LAST CANALS — HIS DEATH AND CHARACTER.

IT is related of

Brindley that, on one occasion, when giving evidence before a

Committee of the House of Commons, in which he urged the superiority

of canals over rivers for purposes of inland navigation, the

question was asked by a member, "Pray, Mr. Brindley, what then do

you think is the use of navigable rivers?" "To make canal

navigations, to be sure," was his instant reply. It is easy to

understand the gist of the engineer's meaning. For purposes of

trade he regarded regularity and certainty of communication as

essential conditions of any inland navigation; and he held that

neither of these could be relied upon in the case of rivers, which

are in winter liable to interruption by floods, and in summer by

droughts. In his opinion, a canal, with enough of water always

kept banked up, or locked up where the country would not admit of

the level being maintained throughout, was absolutely necessary to

satisfy the requirements of commerce. Hence he held that one

of the great uses of rivers was to furnish a supply of water for

canals. It was only another illustration of the "nothing like

leather" principle; Brindley's head being so full of canals, and his

labours so much confined to the making of canals, that he could

think of little else.

In connection with the Grand Trunk—which proved, as Brindley

had anticipated, to be the great aorta of the canal system of the

midland districts of England—numerous lines were projected and

afterwards carried out under our engineer's superintendence.

One of the most important of these was the Wolverhampton Canal,

connecting the Trent with the Severn, and authorised in the same

year as the Grand Trunk itself. It is now known as the

Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal, passing close to the towns

of Wolverhampton and Kidderminster, and falling into the Severn at

Stourport. This branch opened up several valuable coal-fields,

and placed Wolverhampton and the intermediate districts, now teeming

with population and full of iron manufactories, in direct connection

with the ports of Liverpool, Hull, and Bristol. Two years

later, in 1768, three more canals, laid out by Brindley, were

authorised to be constructed: the Coventry Canal to Oxford,

connecting the Grand Trunk system by Lichfield with London and the

navigation of the Thames; the Birmingham Canal, which brought the

advantages of inland navigation to the very doors of the central

manufacturing town in England; and the Droitwich Canal, to connect

that town by a short branch with the river Severn. In the

following year a further Act was obtained for a canal laid out by

Brindley, from Oxford to the Coventry Canal at Longford, eighty-two

miles in length. |

The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal near Stourton. [p.276-1]

© Copyright

Roger Kidd and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

These were highly important works; and though they were not

all carried out strictly after Brindley's plans, they nevertheless

formed the groundwork of future Acts, and laid the foundations of

the midland canal system. Thus, the Coventry Canal was never

fully carried out after Brindley's designs; a difference having

arisen between the engineer and the Company during the progress of

the undertaking, in consequence, as is supposed, of the capital

provided being altogether inadequate to execute the works considered

by Brindley as indispensable. He probably foresaw that there

would be nothing but difficulty, and very likely there might be

discredit attached to himself by continuing connected with an

undertaking the proprietors of which would not provide him with

sufficient means for carrying it forward to completion; and though

he finished the first fourteen miles between Coventry and

Atherstone, he shortly after gave up his connection with the

undertaking, and it remained in an unfinished state for many years,

in consequence of the financial difficulties in which the Company

had become involved through the insufficiency of their capital.

The connection of the Coventry Canal with the Grand Trunk was

afterwards completed, in 1785, by the Birmingham and Fawley and

Grand Trunk Companies conjointly, and the property eventually proved

of great value to all parties concerned.

|

Coventry Basin, with statue of Brindley. [p.276-2]

© Copyright

Stephen McKay and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

The Droitwich Canal, though only a short branch five and a

half miles in length, was a very important work, opening up as it

did an immense trade in coal and salt between Droitwich and the

Severn. The works of this navigation were wholly executed by

Brindley, and are considered superior to those of any others on

which he was engaged. Whilst residing at Droitwich, we find

our engineer actively engaged in pushing on the subscription to the

Birmingham Canal, the capital of which was taken slowly.

Matthew Boulton, of Birmingham, was one of the most active promoters

of the scheme, and Josiah Wedgwood also bestirred himself in its

behalf. In a letter written by him about this time, we find

him requesting one of his agents to send out plans to gentlemen whom

he names, in the hope of completing the subscription-list. [p.277]

Brindley did not live to finish the Birmingham Canal; it was carried

out by his successors,—partly by his pupil, Mr. Whitworth, and

partly by Smeaton and

Telford. Brindley's plan was, as

usual, to cut the canal as flat as possible, to avoid the necessity

for lockage; but his successors, in order to relieve the capital

expenditure, as they supposed, constructed it with a number of locks

to carry it over the summit at Smithwick. Shortly after its

opening, however, the Company found reason to regret their rejection

of Mr. Brindley's advice, and they lowered the summit by cutting a

tunnel, as he had originally recommended, thereby incurring an extra

expense of about £30,000.

Droitwich Barge Canal at Porter's Mill. [p.278]

© Copyright

Philip Halling and licensed for reuse

under this

Creative Commons Licence.

Another of Brindley's canals, authorised in 1769, was that

between Chesterfield and the river Trent, at Stockwith, about

forty-six miles in length, intended for the transport of coal, lime,

and lead from the rich mineral districts of Derbyshire, and the

return trade of deals, corn, and groceries to the same districts.

It would appear that Mr. Grundy, another engineer, of considerable

reputation in his day, was consulted about the project, and that he

advised a much more direct route than that pointed out by Brindley,

who looked to the accommodation of the existing towns, rather than

shortness of route, as the main thing to be provided for.

Brindley, in this respect, took very much the same view in laying

out his canals as was afterwards taken by

George Stephenson—a man whom he resembled in many respects—in

laying out railways. He would rather go round an obstacle in

the shape of an elevated range of country, than go through it,

especially if in going round and avoiding expense he could

accommodate a number of towns and villages. Besides, by

avoiding the hills and following the course of the valleys, along

which the population usually lies, he avoided expense of

construction and secured flatness of canal; just as Stephenson

secured flatness of railway gradient. Although the length of

canal to be worked was longer, yet the cost of tunnelling and

lockage was avoided. The population of the district was also

fully accommodated, which could not have been accomplished by the

more direct route through unpopulated districts or under barren

hills. The proprietors of the Chesterfield Canal concurred in

Brindley's view, adopting his plan in preference to Grundy's, and it

was accordingly carried into effect. This navigation was,

nevertheless, a work of considerable difficulty, proceeding, as it

did, across a very hilly country, the summit tunnel at Hartshill

being 2,850 yards in extent. Like many of Brindley's other

works projected about this time, it was finished by his

brother-in-law, Mr. Henshall, and opened for traffic several years

after the great engineer's death. [p.279]

The whole of these canals were laid out by Brindley, though

they were not all executed by him, nor precisely after his plans.

No record of any kind has been preserved of the manner in which the

works were carried out. Brindley himself made few reports, and

these merely stated results, not methods; yet he had doubtless many

formidable difficulties to encounter, and must have overcome them by

the adoption of those ingenious expedients, varying according to the

circumstances of each case, in which he was always found so fertile.

He had no treasury of past experience, as recorded in books, to

consult, for he could scarcely read English; and certainly he could

neither read French nor Italian, in which languages the only

engineering works of any value were then written; nor had he any

store of native experience to draw from he himself being the first

English canal engineer of eminence, and having all his methods and

expedients to devise for himself.

It would doubtless have been most interesting could we have

had some authentic record of this strong original man's struggles

with opposition and difficulty, and the means by which be contrived

not only to win persons of high station to support him with their

influence but also with their purses, at a time when money was

comparatively a much rarer commodity than it is now. "That

want of records, journals, and memoranda," says Mr. Hughes, "which

is ever to be deplored when we seek to review the progress of

engineering works, is particularly felt when we have to look back

upon those undertakings which first called for the exercise of

engineering skill in many new and untried departments. In

Brindley's day, the entire absence of experience derived from former

works, the obscure position which the engineer occupied in the scale

of society, the imperfect communication between the profession in

this country and the engineers and works of other countries, and,

lastly, the backward condition of all the mechanical arts and of the

physical sciences connected with engineering, may all be ranked in

striking contrast with the vast appliances which are placed at the

command of modern engineers." [p.280]

Moreover, the great canal works upon which Brindley was

engaged during the later part of his career, were as yet scarcely

appreciated as respects the important influences which they were

calculated to exercise upon society at large. The only persons

who seem to have regarded them with interest were far-sighted men

like Josiah Wedgwood, who saw in them the means not only of

promoting the trade of his own county, but of developing the rich

natural resources of the kingdom, and diffusing amongst the people

the elements of comfort, intelligence, and civilization. The

literary and scientific classes as yet took little or no interest in

them. The most industrious and observant literary man of the

age, Dr. Johnson, though he had a word to say upon nearly every

subject, never so much as alluded to them, though all Brindley's

canals were finished in Johnson's lifetime, and he must have

observed the works in progress when passing on his various journeys

through the midland districts. The only reference which he

makes to the projects set on foot for opening up the country by

means of better roads, was to the effect, that whereas there were

before cheap places and dear places, now all refuges were destroyed

for elegant or genteel poverty.

Before leaving this part of the subject, it is proper to

state that during the latter part of Brindley's life, whilst canals

were being projected in various directions, he was, on many

occasions, called upon to give his opinion as to the plans which

other engineers had prepared. Among the most important of the

new projects on which he was thus consulted were, the Leeds and

Liverpool Canal; the improvement of the navigation of the Thames to

Reading; the Calder Navigation; the Forth and Clyde Canal; the

Salisbury and Southampton Canal; the Lancaster Canal; and the

Andover Canal. Many of these schemes were of great importance

in a national point of view. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal,

for instance, brought the whole manufacturing district of Yorkshire

along the valley of the Aire into communication with Liverpool and

the intermediate districts of Lancashire. The advantages of

this navigation to Leeds, Bradford, Keighley, and the neighbouring

towns, are felt to this day, and their extraordinary prosperity is

doubtless in no small degree attributable to the facilities which

the canal has provided for the ready conveyance of raw materials and

manufactured produce between those places and the towns and

sea-ports of the west. Brindley surveyed and laid out the

whole line of this navigation, 130 miles in length, and he framed

the estimate on which the Company proceeded to Parliament for their

bill. On the passing of the Act in 1768-9, the Directors

appointed him their engineer; but, being almost overwhelmed with

other business at the time, and feeling that he could not give the

proper degree of personal attention to carrying out so extensive an

undertaking, he was under the necessity of declining the

appointment. The works were immediately begun at both ends of

the canal, and portions were speedily made use of; but the

difficulty and expensiveness of the remaining works greatly delayed

their execution, and the canal was not finished until the year 1816.

Twenty miles, extending from near Bingley to the neighbourhood of

Bradford, were opened on 21st March, 1774. A correspondent of

'Williamson's Liverpool Advertiser' thus describes the opening:

"From Bingley and about three miles down, the noblest

works of the kind that perhaps are to be found in the universe are

exhibited, namely, a five-fold, a three-fold, a two-fold, and a

single lock, making together a fall of 120 feet; a large

aqueduct-bridge of seven arches over the river Aire, and an aqueduct

on a large embankment over Shipley valley. Five boats of

burden passed the grand lock, the first of which descended through a

fall of sixty-six feet in less than twenty-nine minutes. This

much wished-for-event was welcomed with ringing of bells, a band of

music, the firing of guns by the neighbouring militia, the shouts of

spectators, and all the marks of satisfaction that so important an

acquisition merits."

On the 21st October of the same year the following paragraph

appeared:—

"The Liverpool end of the canal was opened from

Liverpool to Wigan on Wednesday, the 19th instant, with great

festivity and rejoicings. The water had been led into the

basin the evening before. At nine A.M.

the proprietors sailed up the canal in their barge, preceded by

another with music, colours flying, &c., and returned to Liverpool

about one. They were saluted with two royal salutes of

twenty-one guns each, besides the swivels on board the boats, and

welcomed with the repeated shouts of the numerous crowds assembled

on the banks, who made a most cheerful and agreeable sight.

The gentlemen then adjourned to a tent, on the quay, where a cold

collation was set out for themselves and their friends. From

thence they went in procession to George's coffee-house, where an

elegant dinner was provided. The workmen, 215 in number,

walked first, with their tools on their shoulders, and cockades in

their hats, and were afterwards plentifully regaled at a dinner

provided for them. The bells rang all day, and the greatest

joy and order prevailed on the occasion."

Brindley being now the recognised head of his profession, and

the great authority on all questions of navigation, he was, in 1770,

employed by the Corporation of London to make a survey of the Thames

above Battersea, with the object of having it improved for purposes

of navigation. As usual, Brindley strongly recommended the

construction of a canal in preference to carrying on the navigation

by the river, where it was liable to be interrupted by the tides and

floods, or by the varying deposits of silt in the shallow places.

In his first report to the Common Council, dated the 16th of June,

1770, he pointed out that the cost of hauling the barges was greatly

in favour of the canal. For example, he stated that the

expense of taking a vessel of 100 or 120 tons from Isleworth to

Sunning, and back again to Isleworth, was £80, and sometimes more;

whilst the cost by the canal would only be £16. The saving in

time would be still greater, for the double voyage might easily be

performed in fifteen hours; whereas by the river the boats were

sometimes three weeks in going up, and almost as much in coming

down. He estimated that there would be a saving to the public

of at least £64 on every voyage, besides the saving of time in

performing it. After making a further detailed examination of

the district, and maturing his views on the whole subject, he sent

in a report, accompanied by a profile of the river about seven feet

long, which is still to be seen amongst the records of the

Corporation of London. His plan was not, however, carried out;

the proposal to construct a canal parallel with the Thames having

been abandoned so soon as the Grand Junction Canal was undertaken.

These and numerous other schemes in various parts of the

country—at Stockton, at Leeds, at Cambridge, at Chester, at

Salisbury and Southampton, at Lancaster, and in Scotland—fully

occupied the attention of Brindley; in addition to which, there was

the personal superintendence which he must necessarily give to the

canals in active progress, and for the execution of which he was

responsible. In fact, there was scarcely a design of a canal

navigation set on foot throughout the kingdom during the later years

of his life, on which he was not consulted, and the plans of which

he did not entirely make, revise, or improve.

In addition to his canal works, Brindley was also consulted

as to the best means of draining the low lands in different parts of

Lincolnshire, and the Great Level in the neighbourhood of the Isle

of Ely. He supplied the corporation of Liverpool with a plan

for cleansing the docks and keeping them clear of mud, which is said

to have proved very effective; and he pointed out to them an

economical method of building walls against the sea without mortar,

which long continued to be employed with complete success. In

such cases he laid his plans freely open to the public, not seeking

to secure them by patent, nor shrouding his proceedings in any

mystery. He was perfectly open with professional men,

harbouring no petty jealousy of rivals. His pupils had free

access to all his methods, and he took a pride in so training them

that they should reflect credit on the engineer's profession, then

rising into importance, and be enabled, after he left the rising

scene, to carry on those great industrial enterprises which he

probably foresaw clearly enough in England's future.

It will be observed, from what we have said, that Brindley's

engagements as an engineer extended over a very wide district.

Even before his employment by the Duke of Bridgewater, he was under

the necessity of travelling great distances to fit up water-mills,

pumping-engines, and manufacturing machinery of various kinds, in

the counties of Stafford, Cheshire, and Lancashire. But when

he had been appointed to superintend the construction of the Duke's

canals, his engagements necessarily became of a still more

engrossing character, and he had very little leisure left to devote

to the affairs of private life. He lived principally at inns,

in the immediate neighbourhood of his work; and though his home was

at Leek, he sometimes did not visit it for weeks together.

Brindley had very little time for friendship, and still less

for courtship. Nevertheless, he did contrive to find time for

marrying, though at a comparatively advanced period of his life.

In laying out the Grand Trunk Canal, he was necessarily brought into

close connection with Mr. John Henshall, of the Bent, near New

Chapel, land-surveyor, who assisted him in making the survey.

He visited Henshall at his house in September, 1762, and then

settled with him the preliminary operations. During his visits

Brindley seems to have taken a special liking for Mr. Henshall's

daughter Anne, then a girl at school, and when he went to see her

father, he was accustomed to take a store of gingerbread for Anne in

his pocket. She must have been a comely girl, judging by the

portrait of her as a woman, which we have seen.

In due course of time, the liking ripened into an attachment;

and shortly after the girl had left school, at the age of only

nineteen, Brindley proposed to her, and was accepted. By that

time he was close upon his fiftieth year, so that the union may

possibly have been quite as much a matter of convenience as of love

on his part. He had now left the Duke's service for the

purpose of entering upon the construction of the Grand Trunk Canal,

and with that object resolved to transfer his home to the immediate

neighbourhood of Harecastle, as well as of his colliery at Golden

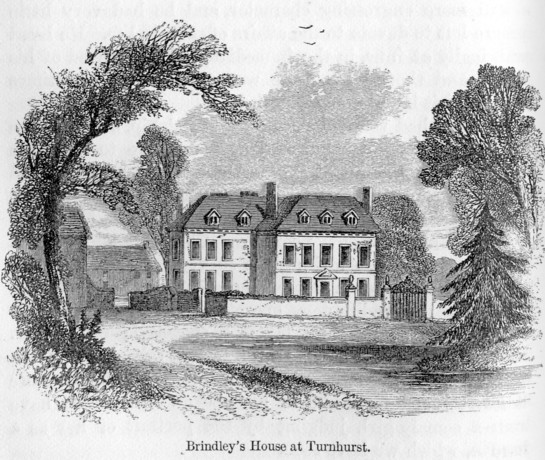

Hill. Shortly after the marriage, the old mansion of Turnhurst

fell vacant, and Brindley with his young wife became its occupants.

The marriage took place on the 8th December, 1765, in the parish

church of Wolstanton, Brindley being described in the register as

"of the parish of Leek, engineer;" but from that time until the date

of his death his home was at Turnhurst.

[p.286]

The house at Turnhurst was a comfortable, roomy,

old-fashioned dwelling, with a garden and pleasure-ground behind,

and a little lake in front. It was formerly the residence of

the Bellot family, and is said to have been the last mansion in

England in which a family fool was maintained. Sir Thomas

Bellot, the last of the name, was a keen sportsman, and the panels

of several of the upper rooms contain pictorial records of some of

his exploits in the field. In this way Sir Thomas seems to

have squandered his estate, and it shortly after became the property

of the Alsager family, from whom Brindley rented it. A little

summer-house, standing at the corner of the outer courtyard, is

still pointed out as Brindley's office, where he sketched his plans

and prepared his calculations. As for his correspondence, it

was nearly all conducted, subsequent to his marriage, by his wife,

who, notwithstanding her youth, proved a most clever, useful, and

affectionate partner.

Turnhurst was conveniently near to the works then in progress

at Harecastle Tunnel, which was within easy walking distance, whilst

the colliery at Golden Hill was only a few fields off. From

the elevated ground at Golden Hill, the whole range of high ground

may be seen under which the tunnel runs—the populous Pottery towns

of Tunstall and Burslem filling the valley of the Trent towards the

south. At Golden Hill, Brindley carried out an idea which he

had doubtless brought with him from Worsley. He and his

partners had an underground canal made from the main line of the

Harecastle Tunnel into their coal-mine, about a mile and a half in

length; and by that tunnel the whole of the coal above that level

was afterwards worked out, and conveyed away for sale in the Pottery

and other districts, to the great profit of the owners and much to

the convenience of the public.

These various avocations involved a great amount of labour as

well as anxiety, and probably considerable tear and wear of the

vital powers. But we doubt whether mere hard work ever killed

any man, or whether Brindley's labours, extraordinary though they

were, would have shortened his life, but for the far more trying

condition of the engineer's vocation—irregular living, exposure in

all weathers, long fasting, and then, perhaps, heavy feeding when

the nervous system was exhausted, together with habitual disregard

of the ordinary conditions of physical health. These are the

main causes of the shortness of life of most of our eminent

engineers, rather than the amount and duration of their labours.

Thus the constitution becomes strained, and is ever ready to break

down at the weakest place. Some violation of the natural laws

more flagrant than usual, or a sudden exposure to cold or wet,

merely presents the opportunity for an attack of disease which the

ill-used physical system is found unable to resist.

Such an accidental exposure unhappily proved fatal to

Brindley. While engaged one day in surveying a branch canal

between Leek and Froghall, he got drenched near Ipstones, and went

about for some time in his wet clothes. This he had often

before done with impunity, and he might have done so again; but,

unfortunately, he was put into a damp bed in the inn at Ipstones,

and this proved too much for his constitution, robust though he

naturally was. He became seriously ill, and was disabled from

all further work. Diabetes shortly developed itself, and,

after an illness of some duration, he expired at his house at

Turnhurst, on the 27th of September, 1772, in the fifty-sixth year

of his age, and was interred in the burying-ground at New Chapel, a

few fields distant from his dwelling.

James Brindley was probably one of the most remarkable

instances of self-taught genius to be found in the whole range of

biography. The impulse which he gave to social activity, and

the ameliorative influence which he exercised upon the condition of

his countrymen, seem out of all proportion to the meagre

intellectual culture which he had received in the course of his

laborious and active career. We must not, however, judge him

merely by the literary test. It is true, he could scarcely

read, and he was thus cut off, to his own great loss, from familiar

intercourse with a large class of cultivated minds, living and dead;

for he could with difficulty take part in the conversation of

educated men, and he was unable to profit by the rich stores of

experience treasured up in books. Neither could he write,

except with difficulty and inaccurately, as we have shown by the

extracts above quoted from his note-books, which are still extant.

Brindley was, nevertheless, a highly-instructed man in many

respects. He was full of the results of careful observation,

ready at devising the best methods of overcoming material

difficulties, and possessed of a powerful and correct judgment in

matters of business. When any emergency arose, his quick

invention and ingenuity, cultivated by experience, enabled him

almost at once unerringly to suggest the best means of providing for

it. His ability in this way was so remarkable, that those

about him attributed the process by which he arrived at his

conclusions rather to instinct than reflection—the true instinct of

genius. "Mr. Brindley," said one of his contemporaries, "is

one of those great geniuses whom Nature sometimes rears by her own

force, and brings to maturity without the necessity of cultivation.

His whole plan is admirable, and so well concerted that he is never

at a loss; for, if any difficulty arises, he removes it with a

facility which appears so much like inspiration, that yon would

think Minerva was at his fingers' ends."

His mechanical genius was indeed most highly cultivated.

From the time when he bound himself apprentice to the trade of a

millwright—impelled to do so by the strong bias of his nature—he had

been undergoing a course of daily and hourly instruction.

There was nothing to distract his attention, or turn him from

pursuing his favourite study of practical mechanics. The

training of his inventive faculty and constructive skill was,

indeed, a slow but a continuous process; and when the time and the

opportunity arrived for turning these to account—when the

silk-throwing machinery of the Congleton mill, for instance, had to

be perfected and brought to the point of effectively performing its

intended work—Brindley was found able to take it in hand and carry

out the plan, when even its own designer had given it up in despair.

But it must also be remembered that this extraordinary ability of

Brindley was in a great measure the result of close observation,

pains-taking study of details, and the most indefatigable industry.

The same qualities were displayed in his improvements of the

steam-engine, and his arrangements to economise power in the pumping

of water from drowned mines. It was often said of his works,

as was said of Columbus's discovery, "How easy! how simple!" but

this was after the fact. Before he had brought his fund of

experience and clearness of vision to bear upon a difficulty, every

one was equally ready to exclaim "How difficult! how absolutely

impracticable!" This was the case with his "castle in the

air," the Barton Viaduct—such a work as had never before been

attempted in England, though now any common mason would undertake

it. It was Brindley's merit always to be ready with his

simple, practical expedient; and he rarely failed to effect his

purpose, difficult although at first sight its accomplishment might

seem to be.

Like men of a similar stamp, Brindley had great confidence in

himself and in his powers and resources. Without this, it had

been impossible for him to have accomplished so much as he did.

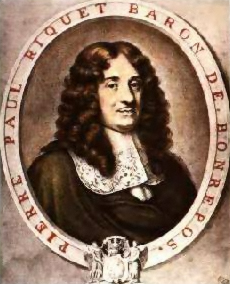

It is said that the King of France, hearing of his wonderful genius,

and the works he had performed for the Duke of Bridgewater at

Worsley, expressed a desire to see him, and sent a message inviting

him to view the Grand Canal of Languedoc. But Brindley's reply

was characteristic: "I will have no journeys to foreign countries,"

said he, "unless to be employed in surpassing all that has been

already done in them."

His observation was remarkably quick. In surveying a

district, he rapidly noted the character of the country, the

direction of the hills and the valleys, and, after a few journeys on

horseback, he clearly settled in his mind the best line to be

selected for a canal, which almost invariably proved to be the right