|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IV.

HUGH MYDDELTON (continued) — HIS OTHER ENGINEERING AND MINING WORKS

— AND DEATH.

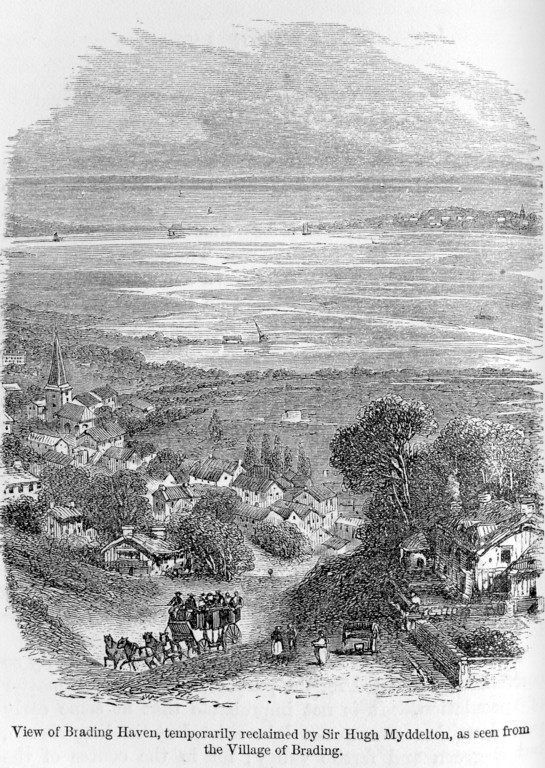

SHORTLY after the

completion of the New River, and the organization of the Company for

the supply of water to the metropolis, we find Hugh Myddelton

entering upon a new and formidable enterprise—that of enclosing a

large tract of drowned land from the sea. The scene of his

operations on this occasion was the eastern extremity of the Isle of

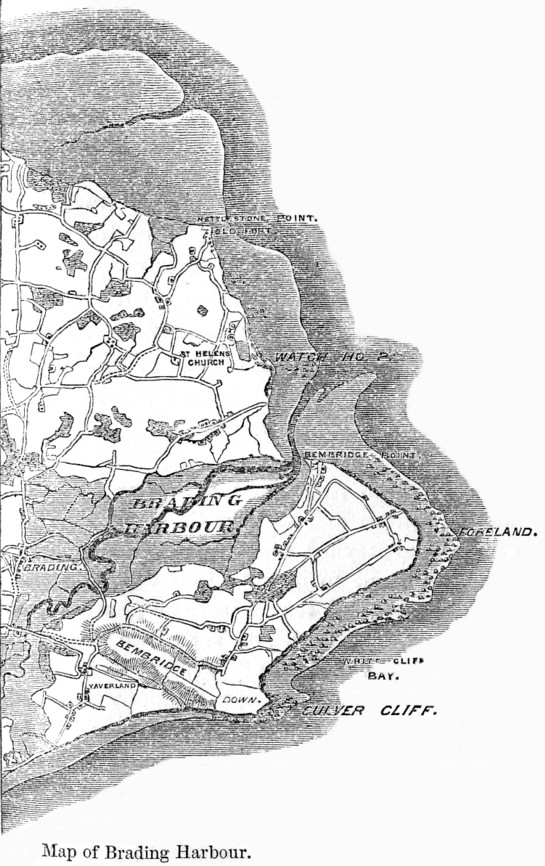

Wight, at a place now marked on the maps as Brading Harbour.

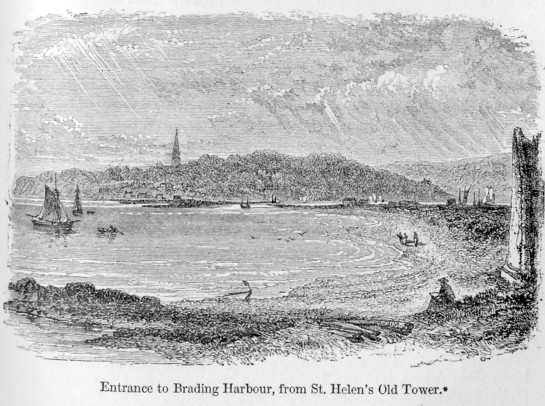

This harbour or haven consists of a tract of about eight hundred

acres in extent. At low water it appears a wide mud flat,

through the middle of which a small stream, called the Yar, winds

its way from near the village of Brading, at the head of the haven,

to the sea at its eastern extremity; whilst at high tide it forms a

beautiful and apparently inland lake, embayed between hills of

moderate elevation covered with trees, in many places down to the

water's edge. At its seaward margin Bemridge Point stretches

out as if to meet the promontory on he opposite shore, where stands

the old tower of St. Church, now used as a sea-mark; and, as seen

from most points, the bay seems to be completely landlocked.

The reclamation of so large a tract of land, apparently so

conveniently situated for the purpose, had long been matter of

speculation. It is not improbable that at some early period

neither swamp nor lake existed at Brading Haven, but a green and

fertile valley; for in the course of the works undertaken by Sir

Hugh Myddelton for its recovery from the sea, a well, strongly cased

with stone, was discovered near the middle of the haven, indicating

the existence of a population formerly settled on the soil.

The sea must, however, have burst in and destroyed the settlement,

laying the whole area under water.

In King James's reign, when the inning of drowned lands began

to receive an unusual degree of attention, the project of reclaiming

Brading Haven was again revived; and in the year 1616 a grant was

made of the drowned district to one John Gibb, the King reserving to

himself a rental of £20 per annum. The owners of the adjoining

lands contested the grant, claiming a prior right to the property in

the haven, whatever its worth might be. But the verdict of the

Exchequer went against the landowners, and the right of the King to

grant the area of the haven for the purpose of reclamation was

maintained. It appears that Gibb sold his grant to one Sir

Bevis Thelwall a page of the King's bedchamber, who at once invited

Hugh Myddelton to join him in undertaking the work; but Thelwall

would not agree to pay Gibb anything until the enterprise had been

found practicable. In 1620 we find that a correspondence was

in progress as to "the composition to be made by the

Solicitor-General with Myddelton touching the draining of certain

lands in the Isle of Wight, and the bargain having been made

according to such directions as His Majesty hath given, then to

prepare the surrender, and thereupon such other assurance for His

Majesty as shall be requisite." [p.86]

A satisfactory arrangement having been made with the King,

Myddelton began the work of reclaiming the haven in the course of

the same year. He sent to Holland for Dutch workmen familiar

with such undertakings; and from the manner in which he carried out

his embankment, it is obvious that he mainly followed the Dutch

method of reclamation, which, as we have already seen in the case of

the drainage of the Fens by Vermuyden, was not, in many respects,

well adapted for English practice. But it would also appear,

from a patent for draining land which he took out in 1621, that he

employed some invention of his own for the purpose of facilitating

the work. The introduction to the grant of the patent runs as

follows:—

"WHEREAS

wee are given to understand that our welbeloved subiect Hugh

Middleton, Citizen and Goldsmith of London, hath to his very great

charge maynteyned many strangers and others, and bestowed much of

his tyme to invent a new way, and by his industrie, greate charge,

paynes, and long experience, hath devised and found out 'A NEW

INVENČON, SKILL,

OR WAY

FOR THE WYNNING AND

DRAYNING OF MANY

GROUNDS WHICH ARE

DAYLIE AND DESPERATELIE

SURROUNDED WITHIN OUR KINGDOMS

OF ENGLAND AND

DOMINION OF

WALES,'

and is now in very great hope to bringe the same to good effect, the

same not being heretofore known, experimented, or vsed within our

said realme or dominion, whereby much benefitt, which as yet is

lost, will certenly be brought both to vs in particular and to our

comon wealth in generall, and hath offered to publish and practise

his skill amongest our loving subjects. . . . . . . ., KNOWE

YEE, that wee, tendring

the weale of this our kingdom and the benefitt of our subjects, and

out of our princely care to nourish all arts , invencions, and

studdies whereof there may be any necessary or pffitable vse within

our dominions, and out of our desire to cherish and encourage the

industries and paynes of all other our loving subiects in the like

laudable indeavors, and to recompense the labors and expenses of the

said Hugh Middleton disbursed and to be susteyned as aforesaid, and

for the good opinion wee have conceived of the said Hugh Middleton,

for that worthy worke of his in bringing the New River to our cittie

of London, and his care and industrie in busines of like nature

tending to the publicke good . . . . . doe give and graunt full,

free, and absolute licence, libertie, power, and authoritie vnto the

said Hughe Middleton, his deputies," &c. to use and practise the

same during the terme of fowerteene years next ensuing the date

hereof.

No description is given of the particular method adopted by

Myddelton in forming his embankments. It would, however,

appear that he proceeded by driving piles into the bottom of the

Haven near Bembridge Point where it is about the narrowest, and thus

formed a strong embankment at its junction with the sea, but

unfortunately without making adequate provision for the egress of

the inland waters.

[p.87]

A curious contemporary manuscript by Sir John Oglander is

still extant, preserved amongst the archives of the Oglander family,

who have held the adjoining lands from a period antecedent to the

date of the Conquest, which we cannot do better than quote, as

giving the most authentic account extant of the circumstances

connected with the enclosing of Brading Haven by Hugh Myddelton.

This manuscript says:—

"Brading Haven was begged first of

all of King James by one Mr. John Gibb, being a groom of his

bedchamber, and the man that King James trusted to carry the

reprieve to Winchester for my Lord George Cobham and Sir Walter

Rawleigh, when some of them were on the scaffold to be executed.

This man was put on to beg it of King James by one Sir Bevis

Thelwall, who was then one of the pages of the bedchamber.

After be had begged it, Sir Bevis would give him nothing for it

until the haven were cleared; for the gentlemen of the island whose

lands join to the haven challenged it as belonging unto them.

King James was wonderful earnest in the business, both because it

concerned his old servant, and also because it would be a leading

case for the fens in Lincolnshire. After the verdict went in

the Chequer against the gentlemen, then Sir Bevis Thelwall would

give nothing for it till he could see that it was feasible to be

inned from the sea; whereupon one Sir Hugh Myddelton was called in

to assist and undertake the work, and Dutchmen were brought out of

the Low Countries, and they began to inn the haven about the 20th of

December, 1620. Then, when it was taken in, King James

compelled Thelwall and Myddelton to give John Gibb (who the King

called 'Father') £2,000. Afterwards Sir Hugh Myddelton, like a

crafty fox and subtle citizen, put it off wholly to Sir Bevis

Thelwall, betwixt whom afterwards there was a great suit in the

Chancery; but Sir Bevis did enjoy it some eight years, and bestowed

much money in building of a barnhouse, mill, fencing of it, and in

many other necessary works.

"But now let me tell you somewhat of Sir Bevis Thelwall and

Sir Hugh Myddelton, and of the nature of the ground after it was

inned, and the cause of the last breach. Sir Bevis was a

gentleman's son in Wales, bound apprentice to a mercer in Cheapside,

and afterwards executed that trade till King James came into

England: then be gave up, and purchased to be one of the pages of

the bedchamber, where, being an understanding man, and knowing how

to handle the Scots, did in that infancy gain a fair estate by

getting the Scots to beg for themselves that which he first found

out for them, and then himself buying of them with ready money under

half the value. He was a very bold fellow, and one that King

James very well affected. Sir Hugh Myddelton was a goldsmith

in London. This and other famous works brought him into the

world, viz., his London waterwork, Brading Haven, and his mine in

Wales.

"The nature of the ground, after it was inned, was not

answerable to what was expected, for almost the moiety of it next to

the sea was a light running sand, and of little worth. The

best of it was down at the farther end next to Brading, my Marsh,

and Knight's Tenement, in Bembridge. I account that there was

200 acres that might be worth 6s. 8d. the acre, and all the rest 2s.

6d. the acre. The total of the haven was 706 acres. Sir

Hugh Myddelton, before he sold, tried all experiments in it: he

sowed wheat, barley, oats, cabbage seed, and last of all rape seed,

which proved best; but all the others came to nothing. The

only inconvenience was in it that the sea brought in so much sand

and ooze and seaweed that choked up the passage of the water to go

out, insomuch as I am of opinion that if the sea had not broke in

Sir Bevis could hardly have kept it, for there would have been no

current for the water to go out; for the eastern tide brought so

much sand as the water was not of force to drive it away, so that in

time it would have laid to the sea, or else the sea would have

drowned the whole country. Therefore, in my opinion, it is not

good meddling with a haven so near the main ocean.

"The country (I mean the common people) was very much against

the inning of it, as out of their slender capacity thinking by a

little fishing and fowling there would accrue more benefit than by

pasturage; but this I am sure of, it caused, after the first three

years, a great deal of more health in these parts than was ever

before; and another thing is remarkable, that whereas we thought it

would have improved our marshes, certainly they were the worse for

it, and rotted sheep which before fatted there.

"The cause of the last breach was by reason of a wet time

when the haven was full of water, and then a high spring tide, when

both the waters met underneath in the loose sand. On the 8th

of March, 1630, one Andrew Ripley that was put in earnest to look to

Brading Haven by Sir Bevis Thelwall, came in post to my house in

Newport to inform me that the sea had made a breach in the said

haven near the easternmost end. I demanded of him what the

charge might be to stop it out; he told me he thought 40s.,

whereupon I bid him go thither and get workmen against the next day

morning, and some carts, and I would pay them their wages; but the

sea the next day came so forcibly in that there was no meddling of

it, for Ripley went up presently to London to Sir Bevis Thelwall

himself, to have him come down and take some further course; but

within four days after the sea had won so much on the haven, and

made the breach so wide and deep, that on the 15th of March when I

came thither to see it I knew not well what to judge of it, for

whereas at the first £5 would have stopped it out, now I think £200

will not do it, and what will be the event of it time will tell.

Sir Bevis on news of this breach came into the island on the 17th of

March, 1630, and brought with him a letter from my Lord Conway to me

and Sir Edward Dennies, desiring us to cause my Lady Worsley, on

behalf of her son, to make up the breach which happened in her

ground through their neglect. She returned us an answer that

she thought that the law would not compel her unto it, and therefore

desired to be excused, which answer we returned to my lord.

What the event will be I know not, but it seemeth to me not

reasonable that she should suffer for not complying with his

request. If he had not inned the haven this accident could

never have happened; therefore he giving the cause, that she should

apply the cure I understand not. But this I am sure, that Sir

Bevis thinketh to recover of her and her son all his charges, which

he now sweareth every way to be £2,000. For my part, I would

wish no friend of mine to have any hand in the second inning of it.

Truly all the better sort of the island were very sorry for Sir

Bevis Thelwall, and the commoner sort were as glad as to say truly

of Sir Bevis that he did the country many good offices, and was

ready at all times to do his best for the public and for everyone.

"Sir Hugh Myddelton took it first in, and it was proper for

none but him, because he had a mine of silver in Wales to maintain

it. It cost at the first taking of it in £4,000, then they

gave £2,000 to Mr. John Gibb for it, who had begged it of King

James; afterwards, in building the barn and dwelling-house, and

water-mill, with the ditching and quick-setting, and making all the

partitions, it could not have cost less than £200 more: so in the

total it stood them, from the time they began to take it in, until

the 8th of March, a loss of £7,000."

It will thus be observed that the loss of this undertaking

fell upon Thelwall, and not upon Myddelton, who sold out of the

adventure long before the sea burst through the embankment.

The date of conveyance of his rights in the reclaimed land to Sir

Bevis Thelwall was the 4th September, 1624, nearly six years before

the final ruin of the work. He had, therefore, got his capital

out of the concern, most probably with his profit as contractor, and

was thus free to embark in the important mining enterprise in Wales,

on which we find him next engaged.

Sir Hugh continued to maintain his Parliamentary connection

with his native town of Denbigh, of which he was still the

representative. We do not find that he took an active part in

political questions. The name of his brother, Sir Thomas,

frequently appears in the Parliamentary debates of the time, and he

was throughout a strong opponent of the Court party; but that of Sir

Hugh only occurs in connection with commercial topics or schemes of

internal improvement, on which he seems to have been consulted as an

authority.

Sir Hugh's occasional visits to his constituents brought him

into contact with Welsh families, and made him acquainted with the

mining enterprises then on foot in different parts of Wales—so rich

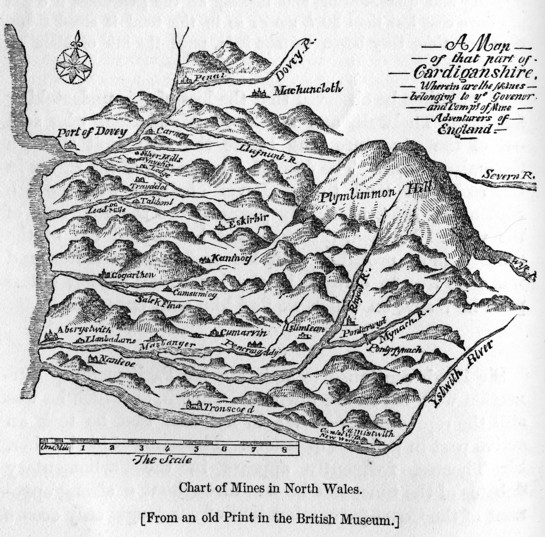

in ores of copper, lead, and iron. It appears that the

Governor and Company of Mines Royal in Cardiganshire were

incorporated in the year 1604, for the purpose of working the lead

and silver mines of that county. The principal were those at

Cwmsymlog and the Darren Hills, situated about midway, as the crow

flies, between Aberystwith and the mountain of Plinlimmon, and at

Tallybout, about midway between Aberystwith and the estuary at the

mouth of the River Dovey. They were all situated in the

township of Skibery Coed, in the northern part of the county of

Cardigan. For many years these mines (which were first opened

out by the Romans) were worked by the Corporation of Mines Royal;

but it does not appear that much success attended their operations.

Mining was little understood then, and all kinds of pumping and

lifting machinery were clumsy and inefficient. Although there

was no want of ore, the mines were so drowned by water, that the

metal could not well be got at and worked out.

Myddelton's spirit of enterprise was excited by the prospect

of battling with the water and getting at the rich ore, and he had

confidence that his mechanical ability would enable him to overcome

the difficulties. The Company of Mines Royal were only too

glad to get rid of their unprofitable undertaking, and they agreed

to farm their mines to Sir Hugh at the rental of £400 per annum.

This was in the year 1617, some time after he had completed his New

River works, but before he had begun the embankment of Brading

Haven,—and Sir Bevis Thelwall was also a partner with him in this

new venture. It took him some time to clear the mines of

water, which he did by pumping-machines of his own contrivance; but

at length sufficient ore was raised for testing, and it was found to

contain a satisfactory proportion of silver. His mining

adventure seems to have been attended with success, for we shortly

afterwards find him sending considerable quantities of silver to the

Royal Mint to be coined.

King James was so much gratified by the further proofs of

Myddelton's skill and enterprise, displayed in his embankment of

Brading Harbour and his successful mining operations in Wales, that

he raised him to the dignity of a Baronet on the 19th of October,

1622; and the compliment was all the more marked by His Majesty

directing that Sir Hugh should be discharged from the payment of the

customary fees, amounting to £1,095, and that the dignity should be

conferred upon him without any charge whatever. [p.94-1]

The patent of baronetcy granted on the occasion sets forth the

"reasons and considerations" which induced the King to confer the

honour; and it may not be out of place to remark, that though more

eminent industrial services have been rendered to the public by

succeeding engineers, there has been no such cordial or graceful

recognition of them by any succeeding monarch. The patent

states that King James had made a baronet of Hugh Myddelton, of

London, goldsmith, for the following reasons and considerations:—

"1. For bringing to the city of London, with

excessive charge and greater difficulty, a new cutt or river of

fresh water, to the great benefit and inestimable preservation

thereof. 2. For gaining a very great and spacious quantity of

land in Brading Haven, in the Isle of Wight, out of the bowells of

the sea, and with banker and pyles and most strange defensible and

chargeable mountains, fortifying the same against the violence and

fury of the waves. 3. For finding out, with a fortunate and

prosperous skill, exceeding industry, and noe small charge, in the

county of Cardigan, a royal and rych myne, from whence he hath

extracted many silver plates which have been coyned in the Tower of

London for current money of England." [p.94-2]

The King, however, did more than confer the title—he added to

it a solid benefit in confirming the lease made to Sir Hugh by the

Governor and Company of Mines Royal, "as a recompense for his

industry in bringing a new river into London," waiving all claim to

royalty upon the silver produced, although the Crown was entitled,

according to the then interpretation of the law, to a payment on all

gold and silver found in the lands of a subject; and it is certain

that the lessee [p.95] who

succeeded Sir Hugh did pay such royalty into the State Exchequer.

It also appears from documents preserved amongst the State Papers,

that large offers of royalty were actually made to the King at the

very time that this handsome concession was granted to Sir Hugh.

The discovery of silver in the Welsh mountains doubtless

caused much talk at the time, and, as in Australia and California

now, there were many attempts made by lawless persons to encroach

upon the diggings. On this, a royal proclamation was

published, warning such persons against the consequences of their

trespass, and orders were issued that summary proceedings should be

taken against them. It appears that Sir Hugh and his partners

continued to work the mines with profit for a period of about

sixteen years, although it is stated that during most of that time,

in consequence of the large quantity of water met with, little more

than the upper surface could be got at. The water must,

however, have been sufficiently kept under to enable so much ore

eventually to be raised. Waller says an engine was employed at

Cwmsymlog; and a tradition long existed among the neighbouring

miners that there were two engines placed about the middle of the

work. There were also several "levels" at Cwmsymlog, one of

which is called to this day "Sir Hugh's Level."

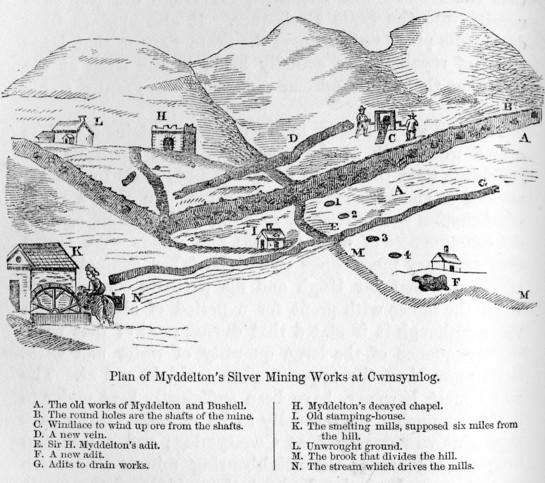

The following rude cut, from Pettus' 'Fodinæ Regales,' may

serve to give an idea of the manner in which the works of Cwmsymlog

(facetiously styled by the author or his printer "Come-some-luck")

were laid out:

From a statement made by Bushell to Parliament of the results

of the working subsequent to 1636, it appears that the lead alone

was worth above £5,000 a year, to which there was to be added the

value of the silver—Bushell alleging, in his petition to Charles I.,

deposited in the State Paper-office, [p.96]

that Sir Hugh had brought "to the Minte theis 16 yeares of puer

silver 100 poundes weekly." A ton of the lead ore is said to

have yielded about a hundred ounces of silver, and the yield at one

time was such that Myddelton's profits were alleged by Bushell to

have amounted to at least two thousand pounds a month. There

is no doubt, therefore, that Myddelton realised considerable profits

by the working of his Welsh mines, and that towards the close of his

useful life he was an eminently prosperous man. [p.97]

Successful as he had been in his enterprise, he was ready to

acknowledge the Giver of all Good in the matter. He took an

early opportunity of presenting a votive cup, manufactured by

himself out of the Welsh silver, to the corporation of Denbigh, and

another to the head of his family at Gwaenynog, in its immediate

neighbourhood, both of which are still preserved. On the

latter is inscribed "Mentem non munus—Omnia a Deo—Hugh Myddelton."

While conducting the mining operations, Sir Hugh resided at

Lodge, now called Lodge Park, in the immediate neighbourhood of the

mines. The house was the property of Sir John Pryse, of

Gogerddan, whose son Richard, afterwards created a baronet, was

married to Myddelton's daughter Hester. The house stood on the

top of a beautifully wooded hill, overlooking the estuary of the

Dovey and the great bog of Gorsfochno, the view being bounded by

picturesque hills on the one hand and by the sea on the other.

Whilst residing here, on one of his visits to the mines, a letter

reached him from his cousin, Sir John Wynn, of Gwydir, dated the 1st

September, 1625, asking his assistance in an engineering project in

which he was interested. This was the reclamation of the large

sandy marshes, called Traeth-Mawr and Traeth-Bach, situated at the

junction of the counties of Caernarvon and Merioneth, at the

northern extremity of the bay of Cardigan. Sir John, after

hailing his good cousin as "one of the great honours of the nation,"

congratulated him on the great work which he had performed in the

Isle of Wight, and added, "I may say to you what the Jews said to

Christ, We have heard of thy greats workes done abroade, doe now

somewhat in thine own country." After describing the nature of

the land proposed to be reclaimed, Sir John declares his willingness

"to adventure a brace of hundred pounds to joyne with Sir Hugh in

the worke," and concludes by urging him to take a ride to

Traeth-Mawr, which was not above a day's journey from where Sir Hugh

was residing, and afterwards to come on and see him at Gwydir House,

which was at most only another day's journey or about twenty-five

miles further to the north-west of Traeth-Mawr. The following

was Sir Hugh's reply:—

"HONOURABLE

SIR,

"I have received your kind letter. Few are the things

done by me; for which I give God the glory. It may please, you

to understand my first undertaking of public works was amongst my

owns kindred, within less than a myle of the place where I hadd my

first being, 24 or 25 years since, in seekinge of coales for the

town of Denbighe.

"Touching the drowned lands near your lyvinge; there are many

things considerable therein. Iff to be gayned, which will

hardlie be performed without great stones, which was plentiful at

the Weight [Isle of Wight], as well as wood, and great sums of money

to be spent, not hundreds, but thousands; [p.98]

and first of all his Majesty's interest must be got. As for

myself, I am grown into years, and full of business here at the

mynes, the river at London, and other places, my weeklie charge

being above £200; which maketh me verie unwillinge to undertake any

other worke; and the least of theis, whether the drowned lands or

mynes, requireth a whole man, with a large purse. Noble sir,

my desire is great to see you, which should draw me a farr longer

waie; yet such are my occasions at this tyme here, for the settlings

of this great worke, that I can hardlie be spared one hour in a daie.

My wieff being also here, I cannot leave her in a strange place.

Yet my love to publique works, and desire to see you (if God

permit), maie another tyme draws me into those parts. Soe with

my heartie comendations I comit you and all your good desires to

God.

"Your assured lovinge couzin to command,

"Lodge, Sept. 2nd, 1625."

" HUGH

MYDDELTON.

At the date of this letter Sir Hugh was an old man of

seventy, yet he still continued industriously to apply himself to

business affairs. Like most men with whom work has become a

habit, he could not be idle, and active occupation seems to have

been necessary to his happiness. To the close of his life we

find him engaged in correspondence on various subjects—on mining,

draining, and general affairs. When in London he continued to

occupy his house in Bassishaw-street, where the goldsmith business

was carried on in his absence by his son William. He also

continued to maintain his pleasant country house at Bush Bill, near

Edmonton, which he occupied when engaged on the engineering business

of the New River, near to which it was conveniently situated.

At length all correspondence ceases, and the busy hand and

head of the old man find rest in death. Sir Hugh died on the

10th of December, 1631, at the advanced age of seventy-six. In

his will, which he made on the 21st November, three weeks before his

death, when he was "sick in bodie " but "strong in mind," for which

he praised God, he directed that he should be buried in the church

of St. Matthew, Friday-street, where he had officiated as

churchwarden, and where six of his sons and five of his daughters

had been baptized. It had been his parish church, and was

hallowed in his memory by many associations of family griefs as well

as joys; for there he had buried several of his children in early

life, amongst others his two eldest-born sons. The church of

St. Matthew, however, has long since ceased to exist, though its

registers have been preserved: it was destroyed in the great fire of

1666, and the monumental record of Sir Hugh's last resting-place

perished in the common ruin.

The popular and oft-repeated story of Sir Hugh Myddelton

having died in poverty and obscurity is only one of the numerous

fables which have accumulated about his memory. [p.101-1]

He left fair portions to all the children who survived him, and an

ample, provision to his widow. [p.100-2]

His eldest son and heir, William, who succeeded to the baronetcy,

inherited the estate at Ruthin, and afterwards married the daughter

of Sir Thomas Harris, Baronet, of Shrewsbury. Elizabeth, the

daughter of Sir William, married John Grene, of Enfield, clerk to

the New River Company, and from her is lineally descended the Rev.

Henry Thomas Ellacombe, M.A., rector of Clyst St. George, Devon, who

still holds two shares in the New River Company, as trustee for the

surviving descendants of Myddelton in his family. Sir Hugh

left to his two other sons, Henry and Simon, [p.101]

besides what he had already given them, one share each in the New

River Company (after the death of his wife) and £400 a-piece.

His five daughters seem to have been equally well provided for.

Hester was left £900, the remainder of her portion of £1,900; Jane

having already had the same portion on her marriage to Dr.

Chamberlain, of London. Elizabeth and Ann, like Henry and

Simon, were left a share each in the New River Company and £500

a-piece. He bequeathed to his wife, Lady Myddelton, the house

at Bush Hill, Edmonton, and the furniture in it, for use during her

life, with remainder to his youngest son Simon and his heirs.

He also left her all the "chains, rings, jewels, pearls, bracelets,

and gold buttons, which she hath in her custody and useth to wear at

festivals, and the deep silver basin, spout pot, maudlin cup, and

small bowl;" as well as "the keeping and wearing of the great jewel

given to him by the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of London, and after her

decease to such one of his sons as she may think most worthy to wear

and enjoy it." By the same will Lady Myddelton was authorised

to dispose of her interest in the Cardiganshire mines for her own

benefit; and it afterwards appears, from documents in the State

Paper Office, that Thomas Bushell, "the great chymist," as he was

called, purchased it for £400 cash down, and £400 per annum during

the continuance of her grant, which had still twenty-five years to

run after her husband's death.

Besides these bequeathments, and the gifts of land, money,

and New River shares, which he had made to his other children during

his lifetime, Sir Hugh left numerous other sums to relatives,

friends, and clerks; for instance, to Richard Newell and Howell

Jones, £30 each, "to the end that the former may continue his care

in the works in the Mines Royal, and the latter in the New River

water-works," where they were then respectively employed. He

also left an annuity of £20 to William Lewyn, who had been engaged

in the New River undertaking from its commencement. Nor were

his men and women servants neglected, for he bequeathed to each of

them a gift of money, not forgetting "the boy in the kitchen," to

whom he left forty shillings. He remembered also the poor of

Henllan, near Denbigh, "the parish in which he was born," leaving to

them £20; a similar sum to the poor of Denbigh, which he had

represented in several successive Parliaments; and £5 to the parish

of Amwell, in Hertfordshire. To the Goldsmiths' Company, of

which he had so long been a member, he bequeathed a share in the New

River Company, for the benefit of the more necessitous brethren of

that guild, "especially to such as shall be of his name, kindred,

and county."

Such was the life and such the end of Sir Hugh Myddelton, a

man full of enterprise and resources, an energetic and untiring

worker, a great conqueror of obstacles and difficulties, an honest

and truly noble man, and one of the most distinguished benefactors

the city of London has ever known.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

CAPTAIN PERRY — STOPPAGE OF DAGENHAM BREACH.

ALTHOUGH the

cutting of the New River involved a great deal of labour, and was

attended with considerable cost, it was not a work that would now be

regarded as of any importance in an engineering point of view.

It was, nevertheless, one of the greatest undertakings of the kind

that had at that time been attempted in England; and it is most

probable that, but for the persevering energy of Myddelton and the

powerful support of the King, the New River enterprise would have

failed. As it was, a hundred years passed before another

engineering work of equal importance was attempted, and then it was

necessity, and not enterprise, that occasioned it.

We have, in a previous chapter, referred to the artificial

embankment of the Thames, almost from Richmond to the sea, by which

a large extent of fertile land is protected from inundation along

both banks of the river. The banks first raised seemed to have

been in many places of insufficient strength; and when a strong

north-easterly wind blew down the North Sea, and the waters became

pent up in that narrow part of it lying between the Belgian and the

English coasts,—and especially when this occurred at a time of the

highest spring tides,—the strength of the river embankments became

severely tested throughout their entire length, and breaches often

took place, occasioning destructive inundations.

Down to the end of the seventeenth century scarcely a season

passed without some such accident occurring. There were

frequent burstings of the banks on the south side between London

Bridge and Greenwich, the district of Bermondsey, then green fields,

being especially liable to be submerged. Commissions were appointed

on such occasions, with full powers to distrain for rates, and to

impress labourers in order that the requisite repairs might at once

be carried out. In some cases the waters for a long time held their

ground, and refused to be driven back. Thus, in the reign of Henry

VIII., the marshes of Plumstead and Lesnes, now used as a practising

ground by the Woolwich garrison, were completely drowned by the

waters which had burst through Erith Breach, and for a long time all

measures taken to reclaim them proved ineffectual. There were also

frequent inundations of the Combe Marshes, lying on the east of the

royal palace at Greenwich.

But the most destructive inundations occurred on the north bank of

the Thames. Thus, in the year 1676, a serious breach took place at

Limehouse, when many houses were swept away, and it was with the

greatest difficulty that the waters could be banked out again. The

wonder is, that sweeping, as the new current did, over the Isle of

Dogs, in the direction of Wapping, and in the line of the present

West India Docks, the channel of the river was not then permanently

altered. But Deptford was already established as a royal dockyard,

and probably the diversion of the river would have inflicted as much

local injury, judging by comparison, as it unquestionably would do

at the present day. The breach was accordingly stemmed, and the

course of the river held in its ancient channel by Deptford and

Greenwich. Another destructive inundation shortly after occurred

through a breach made in the embankment of the West Thurrock

Marshes, in what is called the Long Reach, nearly opposite Greenhithe, where the lands remained under water for seven years,

and it was with much difficulty that the breach could be closed.

But the most destructive and obstinate of all the breaches was that

made in the north bank a little to the south of the village of

Dagenham, in Essex, by which the whole of the Dagenham and Havering

Levels lay drowned at every tide. A similar breach had occurred in

1621, which Vermuyden, the Dutch engineer, succeeded in stopping;

and at the same time he embanked or "inned" the whole of Dagenham

Creek, through which the little rivulet flowing past the village of

that name found its way to the Thames. Across the mouth of this

rivulet Vermuyden had erected a sluice, of the nature of a "clow,"

being a strong gate suspended by hinges, which opened to admit of

the egress of the inland waters at low tide, and closed against the

entrance of the Thames when the tide rose. It happened, however,

that a heavy inland flood, and an unusually high spring tide,

occurred simultaneously during the prevalence of a strong

north-easterly wind, in the year 1707; when the united force of the

waters meeting from both directions blew up the sluice, the repairs

of which had been neglected, and in a very short time nearly the

whole area of the above Levels was covered by the waters of the

Thames.

At first the gap was so slight as to have been easily closed, being

only from 14 to 16 feet wide. But no measures having been taken to

stop it, the tide ran in and out for several years, every tide

wearing the channel deeper, and rendering the stoppage of the breach

more difficult. At length the channel was found upwards of 30 feet

deep at low water, and about 100 feet wide, a lake more than a mile

and a half in extent having by this time been formed inside the line

of the river embankment. Above a thousand acres of rich lands were

spoiled for all useful purposes, and by the scouring of the waters

out and in at every tide, the soil of about a hundred and twenty

acres was completely washed away. It was carried into the channel of

the Thames, and formed a bank of about a mile in length, reaching

halfway across the river. This state of things could not be allowed

to continue, for the navigation of the stream was seriously

interrupted by the obstruction, and there was no knowing where the

mischief would stop.

Various futile attempts were made by the adjoining landowners to

stem the breach. They filled old ships with chalk and stones, and

had them scuttled and sunk in the deepest places, throwing in

baskets of chalk and earth outside them, together with bundles of

straw and hay to stop up the interstices; but when the full tide

rose, it washed them away like so many chips, and the opening was

again driven clean through. Then the expedient was tried of sinking

into the hole gigantic boxes made expressly for the purpose, fitted

tightly together, and filled with chalk. Power was obtained to lay

an embargo on the cargoes of chalk and ballast contained in passing

ships, for the purpose of filling these boxes, as well as damming up

the gap; and as many as from ten to fifteen freights of chalk a day

were thrown in, but still without effect.

One day when the tide was on the turn, the force of the water lifted

one of the monster trunks sheer up from the bottom, when it toppled

round, the lid opened, out fell the chalk, and, righting again, the

immense box floated out into the stream and down the river. One of

the landowners interested in the stoppage ran along the bank, and

shouted out at the top of his voice, "Stop her! stop her!" But the

unwieldy object being under no guidance was carried down stream

towards the shipping lying at Gravesend, where its unusual

appearance, standing so high out of the water, excited great alarm

amongst the sailors. The empty trunk, however, floated safely past,

down the river, until it reached the Nore, where it stranded upon a

sandbank.

The Government next lent the undertakers an old royal ship called

the Lion, for the purpose of being sunk in the breach, which was

done, with two other ships; but the Lion was broken in pieces by a

single tide, and at the very next ebb not a vestige of her was to be

seen. No matter what was sunk, the force of the water at high tide

bored through underneath the obstacle, and only served to deepen the

breach. After the destruction of the Lion, the channel was found

deepened to 50 feet at low water, at the very place where she had

been sunk.

All this had been but tinkering at the breach, and every measure

that had been adopted merely proved the incompetency of the

undertakers. The obstruction to the navigation through the deposit

of earth and sand in the river being still on the increase, an Act

was passed in 1714, after the bank had been open for a period of

seven years, giving powers for its repair at the public expense. But

it is an indication of the very low state of engineering ability in

the kingdom at the time, that several more years passed before the

measures taken with this object were crowned with success, and the

opening was only closed after a fresh succession of failures.

The works were first let to one Boswell, a contractor. He proceeded

very much after the method which had already failed, sinking two

rows of caissons or chests across the breach, but provided with

sluices for the purpose of shutting off the inroads of the tide. All

his contrivances, however, failed to make the opening watertight;

and his chests were blown up again and again. Then he tried pontoons

of ships, which he loaded and sunk in the opening; but the force of

the tide, as before, rushed under and around them, and broke them

all to pieces, the only result being to make the gap in the bank

considerably wider and deeper than he found it. Boswell at length

abandoned all further attempts to close it, after suffering a heavy

loss; and the engineering skill of England seemed likely to be

completely baffled by this hole in a river's bank.

The competent man was, however, at length found in Captain Perry,

who had just returned from Russia, where, having been able to find

no suitable employment for his abilities in his own country, he had

for some time been employed by the Czar Peter in carrying on

extensive engineering works.

John Perry was born at Rodborough, in Gloucestershire, in 1669, and

spent the early part of his life at sea. In 1693 we find him a

lieutenant on board the royal ship the Montague. The vessel having

put into harbour at Portsmouth to be refitted, Perry is said to have

displayed considerable mechanical skill in contriving an engine for

throwing out a large quantity of water from deep sluices (probably

for purposes of dry docking) in a very short space of time. The

Montague having been repaired, went to sea, and was shortly after

lost. As the English navy had suffered greatly during the same year,

partly by mismanagement, and partly by treachery, the Government was

in a very bad temper, and Perry was tried for alleged misconduct. The result was, that he was sentenced to pay a fine of £1,000, and

to undergo ten years' imprisonment in the Marshalsea.

This sentence must, however, have been subsequently mitigated, for

we find him in 1695 publishing a "Regulation for Seamen," with a

view to the more effectual manning of the English navy; and in 1698

the Marquis of Caermarthen and others recommended him to the notice

of the Czar Peter, then resident in England, by whom he was invited

to go out to Russia, to superintend the establishment of a royal

fleet, and the execution of several gigantic works then contemplated

for the purpose of opening up the resources of that empire. Perry

was engaged by the Czar at a salary of £300 a year, and shortly

after accompanied him to Holland, thence proceeding to Moscow, to

enter upon the business of his office.

One of the Czar's grand designs was to open up a system of inland

navigation to connect his new city of St. Petersburg with the

Caspian Sea, and also to place Moscow upon another line, by forming

a canal between the Don and the Volga. In 1698 the works had been

begun by one Colonel Breckell, a German officer in the Czar's

service. But though a good military engineer, it turned out that he

knew nothing of canal making; for the first sluice which he

constructed was immediately blown up. The water, when let in, forced

itself under the foundations of the work, and the six months' labour

of several thousand workmen was destroyed in a night. The Colonel,

having a due regard for his personal safety, at once fled the

country in the disguise of a servant, and was never after heard of. Captain Perry entered upon this luckless gentleman's office, and

forthwith proceeded to survey the work he had begun, some

seventy-five miles beyond Moscow. Perry had a vast number of

labourers placed at his disposal, but they were altogether

unskilled, and therefore comparatively useless. His orders were to

have no fewer than 30,000 men at work, though he seldom had more

than from 10,000 to 15,000; but one-twentieth the number of skilled

labourers would have better served his purpose. He had many

difficulties to contend with. The local nobility or boyars were

strongly opposed to the undertaking, declaring it to be impossible;

and their observation was, that God had made the rivers to flow one

way, and it was presumption in man to think of attempting to turn

them in another.

Shortly after the Czar had returned to his dominions, he got

involved in war with Sweden, and was defeated by Charles XII. at the

battle of Narva, in 1701. Although the Don and Volga Canal was by

this time half-dug, and many of the requisite sluices were finished,

the Czar sent orders to Perry to let the works stand, and attend

upon him immediately at St. Petersburg. Leaving one of his

assistants to take charge of the work in hand, Perry waited upon his

royal employer, who had a great new design on foot of an altogether

different character. This was the formation of a royal dockyard on

one of the southern rivers of Russia, where Peter contemplated

building a fleet of warships, wherewith to act against the Turks in

the Black Sea. Perry immediately entered upon the office to which he

was appointed, of Comptroller of Russian Maritime Works, and

proceeded to carry out the new project. The site of the Royal

Dockyard was fixed at Veronize on the Don, where he was occupied for

several years, with a vast number of workmen under him, in building

a dockyard, with storehouses, ship-sheds, and workshops. He also

laid down and superintended the construction of numerous vessels,

one of them of eighty guns: the slips on which he built them are

said to have been very ingeniously connived.

The creation of this dockyard was far advanced when he received a

fresh command to undertake the survey of a canal to connect St.

Petersburg with the Volga, to enable provisions, timber, and

building materials to flow freely to the capital from the interior

of the empire. Perry surveyed three several routes, recommending the

adoption of that through Lakes Ladoga and Onega; and the works were

forthwith begun under his direction. Before they were completed,

however, he had left Russia, never to return. During the whole of

his stay in the kingdom he had been unable to get paid for his work.

His applications for his stipulated salary were put off with excuses

from year to year. Proceedings in the courts of law were out of the

question in such a country; he could only dun the Czar and his

ministers; and at length his arrears had become so great, and his

necessities so urgent, that he could no longer endure his position,

and threatened to quit the Czar's service. It came to his ears that

the Czar had threatened on his part, that if he did, he would have

Perry's head; and the engineer immediately took refuge at the house

of the British minister, who shortly after contrived to get him

conveyed safely out of the country, but without being paid. He

returned to England in 1712, as poor as he had left it, though he

had so largely contributed to create the navy of Russia, and to lay

the foundations of its afterwards splendid system of inland

navigation.

It will be remembered that all attempts made to stop the breach at

Dagenham had thus far proved ineffectual; and it threatened to bid

defiance to the engineering talent of England. Perry seemed to be

one of those men who delight in difficult undertakings, and he no

sooner heard of the work than he displayed an eager desire to enter

upon it. He went to look at the breach shortly after his return, and

gave in a tender with a plan for its repair; but on Boswell's being

accepted, which was the lowest, he held back until that contractor

had tried his best, and failed. The way was now clear for Perry, and

again he offered to stop the breach and execute the necessary works

for the sum of £25,000. [p.111] His offer was this time accepted, and operations were begun early in

1715. The opening was now of great width and depth, and a lake had

been formed on the land from 400 to 500 feet broad in some places,

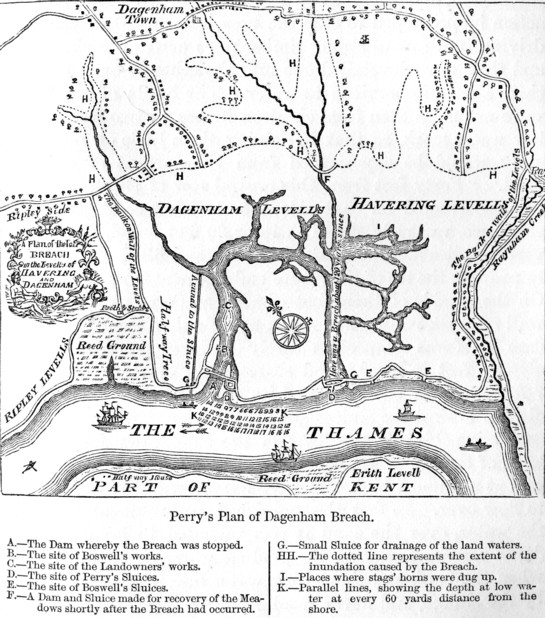

and extending nearly 2 miles in length. Perry's plan of operations

may be briefly explained with the aid of his own map.

In the first place he sought to relieve the tremendous pressure of

the waters against the breach at high tide, by making other openings

in the bank through which they might more easily flow into and out

of the inland lake, without having exclusively to pass through the

gap which it was his object to stop. He accordingly had two

openings, protected by strong sluices, made in the bank a little

below the breach, and when these had been opened and were in action

he proceeded to stop the breach itself. He began by driving in a row

of strong timber piles across the channel; and they were dovetailed

one into the other so as to render them almost impervious to water. The heads of the piles were not more than from eighteen inches to

two feet above low water mark, so that in driving them little or no

difficulty would be experienced from the current of ebb or flood. "Forty feet from this central row of sheeting piles, was constructed

on each side, a sort of low coffer-dam-like structure, variously

stated as 18 or 20 feet broad, formed of vertical piles and

horizontal boarding, and filled with chalk, to prevent the toe of

the future embankment from spreading. On the outside of these

foot-wharfs, as Perry calls them, a wall of chalk rubble was made,

as a further security. The dam itself was composed entirely of

clayey earth, in layers about 3 feet in height, and scarcements or

steps of about 7 feet; and in the course of its erection, care was

taken always to shut the sluices already mentioned when, at each

successive ebb-tide, the level of the back-water fell to the level

of the top of the work in progress. In this way there was at no time

a higher face for the water of the rising tide to flow over. In fact

the unfinished embankment held in the water, over the land it was

intended to lay dry, at a depth corresponding to its gradual

progress, until finally, when the bank was above high-water line, it

was discharged by the sluices, and never re-admitted." [p.112]

Scarcely had Perry begun the work, and proceeded so far as to

exhibit his general design, than Boswell, the former contractor,

presented a petition to Parliament against the engineer being

allowed to go on, alleging that his scheme was utterly

impracticable. The work being of great importance, and executed at

the public expense, a Parliamentary Committee was appointed, when

Perry was called before them and examined fully as to the details. His answers were so explicit, and, on the whole, so satisfactory,

that at the close of the examination one of the members thus spoke

the sense of the Committee:— "You have answered us like an artist,

and like a workman; and it is not only the scheme, but the man, that

we recommend."

Perry was then allowed to proceed, and the work went steadily

forward. About three hundred men were employed in stopping the

breach, and it occupied them about five years to accomplish it. "Perry was proceeding steadily with the dam, which was constructed

by successive scarcements about 7 feet broad and 3 feet high; these

being supported by piles and planking on the side, and protected by

layers of reeds on the top, had been able to resist the action of

the tide when it came on. In this manner he was advancing to

completion, when one of his assistants proposed to the parties who

had advanced Captain Perry the necessary capital, to set all hands

to work at neap tides, and form a narrow wall of earth, unprotected

by reeds or planking, and build it so rapidly as to get it above the

level of the springs before they should come on, and thus at once

exclude the tides from the level. Unfortunately, the next

spring-tide rose to an unexpected height under the influence of a

storm from the north-west, and overtopped this narrow dam by about

six inches, although Perry used the greatest energy, and heightened

the wall of earth by piles and boarding set on edge on the top; but

all in vain: the water poured over it, and in the course of two

hours the whole dam was swept away, and the dovetailed piles laid

bare. This accident was repaired in the winter months, and in June,

1718, the tide was again turned out of the levels; but in September

of the same year the dam gave way again, and this time with far

greater injury to the work, as upwards of 100 feet of the dovetailed

piles were torn up and carried away. In one place there was about 20

feet greater depth than before the work was begun. The third dam was

completed on the 18th June, 1719, about fourteen years after the

accident first occurred." Thus the opening was at length effectually

stopped, and the water drained away by the sluices, leaving the

extensive inland lake, which is to this day used by the Londoners as

a place for fishing and aquatic recreation." [p.114]

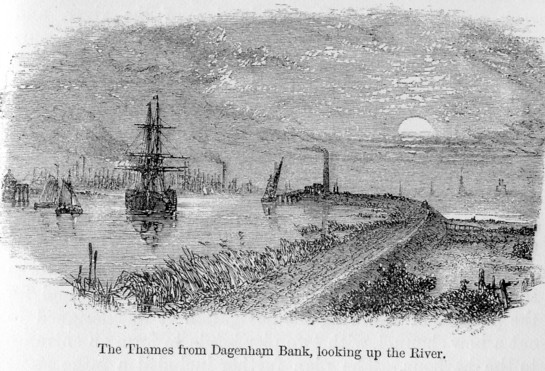

A good idea of formidable character of the embankments extending

along the Thames may be obtained by a visit to this place. Standing

on the top of the bank, which is from 40 to 50 feet above the river

level at low water, [p.115] we

see on the one side the Thames, with its shipping passing and

re-passing, high above the inland level when the tide is up, with the

still lake of Dagenham and the far extending flats on the other. Looking from the lower level on these strong banks extending along

the stream as far as the eye can reach, we can only see the masts of

sailing ships and the funnels of large steamers leaving behind them

long trails of murky smoke,—at once giving an idea of the gigantic

traffic that flows along this great water highway, and the enormous

labour which it has cost to bank up the lands and confine the river

within its present artificial creeks and tributary streams, round

islands and about marshes, from London to the mouth of the Thames,

are not less than 300 miles in extent.

It is to be regretted that Perry gained nothing but fame by his

great work. The expense of stopping the breach far exceeded his

original estimate; he required more materials than he had calculated

upon; and frequent strikes amongst his workmen for advances of wages

greatly increased the total cost. These circumstances seem to have

been taken into account by the Government in settling with the

engineer, and a grant of £15,000 was voted to him in consideration

of his extra outlay. The landowners interested also made him a

present of a sum of £1,000. But even then he was left a loser; and

although the public were so largely benefited by the success of the

work, which restored the navigation of the river, and enabled the,

adjoining proprietors again to reclaim for purposes of agriculture

the drowned lands within the embankment, the engineer did not really

receive a farthing's remuneration for his five years' anxiety and

labour.

After this period Perry seems to have been employed on harbour

works, more particularly at Rye and Dover; but none of these were of

great importance, the enterprise of the country being as yet

dormant, and its available capital for public undertakings

comparatively limited. It appears from the Corporation Records of

Rye, that in 1724 he was appointed engineer to the proposed new

harbour-works there. The port had become very much silted up, and

for the purpose of restoring the navigation it was designed to cut a

new channel, with two pier-heads, to form an entrance to the

harbour. The plan further included a large stone sluice and

draw-bridge, with gates, across the new channel, about a quarter of

a mile within the pier-heads; a wharf constructed of timber along

the two sides of the channel, up to the sluice; together with other

well-designed improvements. But the works had scarcely been begun

before the Commissioners displayed a strong disposition to job, one

of them withdrawing for the purpose of supplying the stone and

timber required for the new works at excessive prices, and others

forming what was called "the family compact," or a secret

arrangement for dividing the spoil amongst them. The plan of Perry

was not fully carried out; and though the pier-heads and stone

sluice were built, the most important part of the work, the cutting

of the new channel, was only partly executed, when the undertaking

was suspended for want of funds.

From that time forward, Perry's engineering ability was very much

confined to making reports as to what things should be done, rather

than in being employed to do them. In 1727 he published his

"Proposals for Draining the Fens in Lincolnshire;" and he seems to

have been employed there as well as in Hatfield Level, where "Perry's Drain" still marks one of his works. He was acting as

engineer for the adventurers who undertook the drainage of Deeping

Fen, in 1732, when he was taken ill and died at Spalding, in the

sixty-third year of his age. He lies buried in the churchyard of

that town; and the tombstone placed over his grave bears the

following inscription:—

|

To the Memory of

JOHN PERRY

Esqr; in 1693

Commander of His Maiesty King Willm's

Ship the Cignet; second Son of Sam' Perry

of Rodborough in Gloucestershire Gent & of

Sarah his Wife; Daughter of Sir Thos Nott; Kt

He was several Years Comptroller of the

Maritime works to Czar Peter in Russia &

on his Return home was Employed by ye

Parliament to stop Dagenham Breach which

he Effected and thereby Preserved the

Navigation of the River of Thames and

Rescued many Private Familys from Ruin

he after departed this Life in this Town &

was here Interred February 13; 1732 Aged

63 Years

This stone was placed over him by the

Order of William Perry of Penthurst in

Kent Esqr his Kindsman and Heir Male |

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VI.

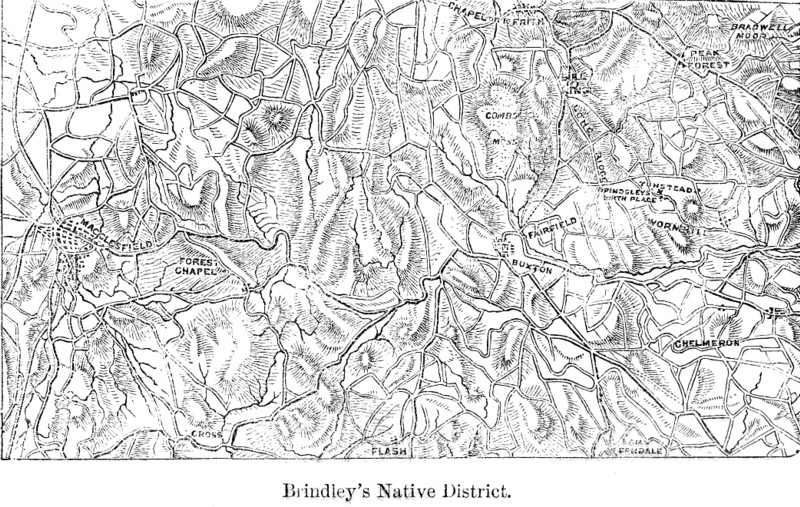

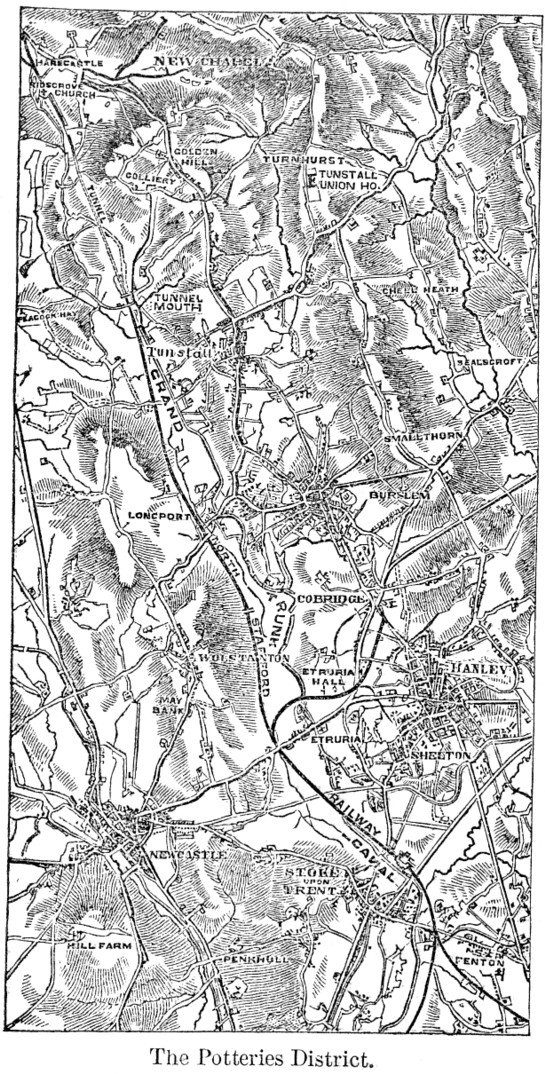

JAMES BRINDLEY — THE BEGINNINGS OF CANAL NAVIGATION.

Statue of James Brindley, Etruria Junction,

Stoke-on-Trent. [p.118-1]

© Copyright

Roger Kidd and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

IN the preceding

memoirs of Vermuyden and Perry, we have found a vigorous contest

carried on against the powers of water, the chief object of the

engineers being to dam it back by embankments, or to drain it off by

cuts and sluices; whilst in the case of Myddelton, on the other

hand, we find his chief concern to have been to collect all the

water within his reach, and lead it by conduit and aqueduct for the

supply of the thirsting metropolis. The engineer whose history

we are now about to relate dealt with water in like manner to

Myddelton, but on a much larger scale; directing it into extensive

artificial canals, for use as the means of communication between

various towns and districts.

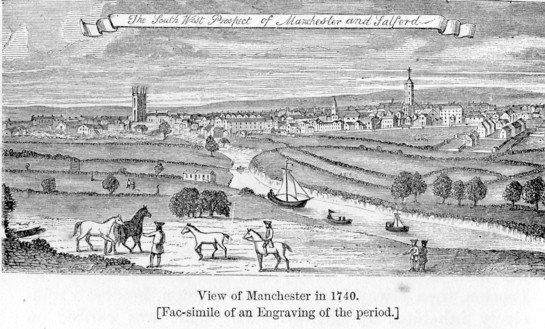

Down to the middle of last century, the trade and commerce of

England were comparatively insignificant. This is sufficiently

clear from the wretched state of our road and river communication

about that time; for it is well understood that without the ready

means of transporting commodities from place to place, either by

land or water, commerce is impossible. But the roads of

England were then about the worst in Europe, and usually impassable

for vehicles during the greater part of the year. [p.118-2]

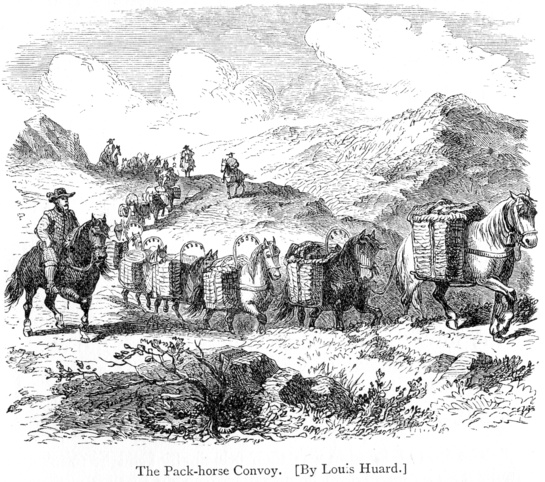

Corn, wool, and such like articles, were sent to market on horses'

or bullocks' backs, and manure was carried to the field, and fuel

conveyed from the forest or the bog, in the same way. The only

coal used in the inland southern counties was carried on horseback

in sacks for the supply of the blacksmiths' forges. The food

of London was principally brought from the surrounding country in

panniers. The little merchandise transported from place to

place was mostly of a light description,—the cloths of the West of

England, the buttons of Birmingham and Macclesfield, the baizes of

Norwich, the cutlery of Sheffield, and the tapes, coatings, and

fustians of Manchester.

Articles imported from abroad were in like manner conveyed

inland by pack-horse or waggon; and it was then cheaper to bring

most kinds of foreign wares from parts to London by sea than to

convey them from the inland parts of England to London by road.

Thus, two centuries since, the freight of merchandise from Lisbon to

London was no greater than the land carriage of the same articles

from Norwich to London; and from Amsterdam or Rotterdam the expense

of conveyance was very much less. It cost from £7 to £9 to

convey a ton of goods from Birmingham to London, and £13 from Leeds

to London. It will readily be understood that rates such as

these were altogether prohibitory as regarded many of the articles

now entering largely into the consumption of the great body of the

people. Things now considered necessaries of life, in daily

common use, were then regarded as luxuries, obtainable only by the

rich. The manufacture of pottery was as yet of the rudest

kind. Vessels of wood, of pewter, and even of leather, formed

the principal part of the household and table utensils of genteel

and opulent families; and we long continued to import our cloths,

our linen, our glass, our "Delph" ware, our cutlery, our paper, and

even our hats, from France, Spain, Germany, Flanders, and Holland.

Indeed, so long as corn, fuel, wool, iron, and manufactured articles

had to be transported on horseback, or in rude waggons dragged over

still ruder roads by horses or oxen, it is clear that trade and

commerce could make but little progress. The cost of transport

of the raw materials required for food, manufactures, and domestic

consumption, must necessarily have formed so large an item as to

have in a great measure precluded their use; and before they could

be made to enter largely into the general consumption, it was

absolutely necessary that greater facilities should be provided for

their transport.

England was not, however, like many other countries less

favourably circumstanced, necessarily dependent solely upon roads

for the means of transport, but possessed natural water

communications, and the means of improving and extending them to an

almost indefinite extent. She was provided with convenient

natural havens situated on the margin of the world's great highway,

the ocean, and had the advantage of fine tidal rivers, up which

fleets of ships might be lifted at every tide into almost the heart

of the land. Very little had as yet been done to take

advantage of this great natural water power, and to extend

navigation inland either by improving the rivers which might be made

navigable, or by means of artificial canals, as had been done in

Holland, France, and even Russia, by which those countries had in

some parts been rendered in a great measure independent of roads.

It is true, public attention had from time to time been

directed to the improvement of rivers and the cutting of canals, but

excepting a few isolated attempts, little had been done towards

carrying the numerous suggested plans in different parts of the

country into effect. If we except some of the wider drains in

the Fens, which were in certain cases made available for purposes of

navigation, though to a very limited extent, the first canal was

that constructed by John Trew, at Exeter, in 1566. In early

times the tide carried vessels up to that city, but the Countess of

Devon took the opportunity of revenging herself upon the citizens

for some affront they had offered to her, by erecting a weir across

the Exe at Topsham in 1284, which had the effect of closing the

river to sea-going vessels. This continued until the reign of

Henry VIII., when authority was granted by Parliament to cut a canal

about three miles in length along the west side of the river, from

Exeter to Topsham. The work was executed by Trew, and it is a

curious circumstance that it contained the first lock constructed in

England,—though locks are said to have been used in the Brenta in

1488, and were shortly after adopted in the Milan canals. John

Trew was a native of Glamorganshire; and though be must have been a

man of skill and enterprise, like many other projectors of

improvements and benefactors of mankind, he seems to have realised

only loss and mortification by his work. In consequence of an

alleged failure on his part in carrying out the agreement for

executing the canal, the Mayor and Chamber of the city disputed his

claims, and he became involved in ruinous litigation. In a

letter written by him to Lord Burleigh, in which he relates his suit

against the Chamber of Exeter, Trew draws a sad picture of the state

to which he was reduced. "The varyablenes of men," says he,

"and the great injury done unto me, brought me in such case that I

wyshed my credetours sattisfyd and I away from earth: what becom may

of my poor wyf and children, who lye in great mysery, for that I

have spent all." [p.121-1]

He then proceeded to recount "the things whearin God hath given

(him) exsperyance;" relating chiefly to mining operations, and

various branches of civil and even military engineering. It is

satisfactory to add that in 1573 the harassing suit was brought to a

conclusion, and Trew granted the Corporation a release on their

agreeing to pay him a sum of £224, and thirty pounds a year for

life. [p.121-2]

In the reign of James I. several Acts of Parliament were

passed, giving powers to improve rivers, so as to facilitate the

passage of boats and barges carrying merchandise. Thus, in

1623, Sir Hugh Myddelton was engaged upon a Committee on a bill then

under consideration "for the making of the river of Thames navigable

to Oxford." In the same year Taylor, the water poet, pointed

out to the inhabitants of Salisbury that their city might be

effectually relieved of its poor by having their river made

navigable from thence to Christchurch. The progress of

improvement, however, must have been slow; as urgent appeals, on the

same subject, continued to be addressed to Parliament and the public

for a century later.

In 1656 we find one Francis Mathew addressing Cromwell and

his Parliament on the immense advantage of opening up a

water-communication between London and Bristol. But he only

proposed to make the rivers Isis and Avon navigable to their

sources, and then either to connect their heads by means of a short

sasse or canal of about three miles across the intervening ridge of

country, or to form a fair stone causeway between the heads of the

two rivers, across which horses or carts might carry produce between

the one and the other. His object, it will be observed, was

mainly the opening up of the existing rivers; "and not," he says,

"to have the old channel of any river to be forsaken for a shorter

passage." Mathew fully recognised the formidable character of

his project, and considered it quite beyond the range of private

enterprise, whether of individuals or of any corporation, to

undertake it; but he ventured to think that it might not be too much

for the power of the State to construct the three miles of canal and

carry out the other improvements suggested by him, with a reasonable

prospect of success. The scheme was, however, too bold for

Mathew's time, and a century elapsed before another canal was made

in England.

A few years later, in 1677, a curious work was published by

Andrew Yarranton, [p.122] in

which he pointed out what the Dutch had accomplished by means of

inland navigation, and what England ought to do as the best means of

excelling the Dutch without fighting them. The main purpose of

his scheme was the improvement of our rivers so as to render them

navigable and the inland country thus more readily accessible to

commerce. For, in England, said he, there are large rivers

well situated for trade, great woods, good wool and large beasts,

with plenty of iron stone, and pit coals, with lands fit to bear

flax, and with mines of tin and lead; and besides all these things

in it, England has a good air. But to make these advantages

available, the country, he held, must be opened up by navigation.

First of all, he proposed that the Thames should be improved to

Oxford, and connected with the Severn by the Avon to Bristol—these

two rivers, he insisted, being the master rivers of England.

When this has been done, says Mr. Yarranton, all the great and heavy

carriage from Cheshire, all Wales, Shropshire, Staffordshire, and

Bristol, will be carried to London and re-carried back to the great

towns, especially in the winter time, at half the rates they now

pay, which will much promote and advance manufactures in the

counties and places above named. "If I were a doctor," he

says,

"and could read a Lecture of the Circulation of the

Blood, I should by that awaken all the City: For London is as the

Heart is in the Body, and the great Rivers are as its Veins; let

them be stopt, there will then be great danger either of death, or

else such Veins will apply themselves to feed some other part of the

Body, which it was not properly intended for: For I tell you, Trade

will creep and steal away from any place, provided she may be better

treated elsewhere." But he goes on—"I hear some say, You projected

the making Navigable the River Stoure in Worcestershire: what is the

reason it was not finished? I say it was my projection, and I

will tell you the reason it was not finished. The River Stoure

and some other Rivers were granted by an Act of Parliament to

certain Persons of Honour, and some progress was made in the work;

but within a small while after the Act passed it was let fall again.

But it being a brat of my own, I was not willing it should be

Abortive; therefore I made offers to perfect it, leaving a third

part of the Inheritance to me and my heirs for ever, and we came to

an agreement. Upon which I fell on, and made it compleatly

Navigable from Sturbridge to Kederminster; and carried down many

hundred Tuns of Coales, and laid out near one thousand pounds, and

then it was obstructed for Want of Money, which by Contract was to

be paid."

There is no question that this "want of money" was the secret

of the little progress made in the improvement of the internal

communications of the country, as well as the cause of the backward

state of industry generally. England was then possessed of

little capital and less spirit, and hence the miserable poverty,

starvation, and beggary which prevailed to a great extent amongst

the lower classes of society at the time when Mr. Yarranton wrote,

and which he so often refers to in the course of his book. For

the same reason most of the early Acts of Parliament for the

improvement of navigable rivers remained a dead letter: there was

not money enough to carry them out, modest though the projects

usually were. Among the few schemes which were actually

carried out about the beginning of the eighteenth century, was the

opening up of the navigation of the rivers Aire and Calder, in

Yorkshire. Though a work of no great difficulty, Thoresby

speaks of it in his diary as one of vast magnitude. It was,

however, of much utility, and gave no little impetus to the trade of

that important district.

It was, indeed, natural that the demand for improvements in

inland navigation should arise in those quarters where the

communications were the most imperfect and where good communications

were most needed, namely, in the manufacturing districts of the

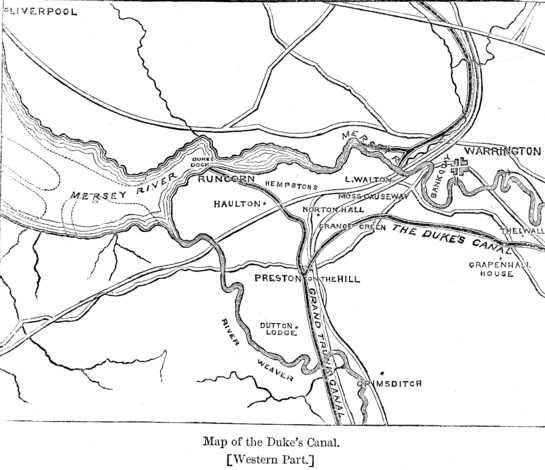

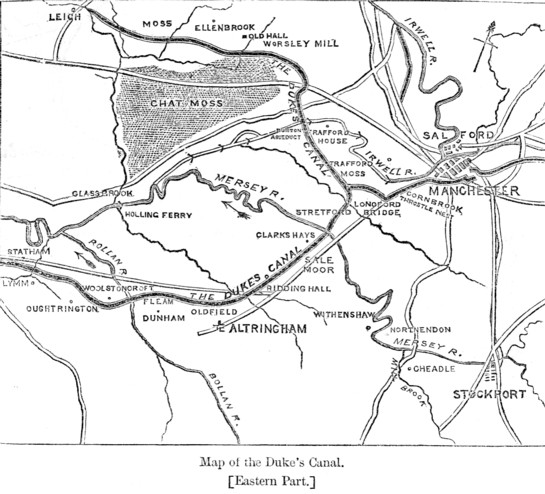

north of England. On the western side of the island Liverpool

was then rising in importance, and the necessity became urgent for

opening up its water communications with the interior. By the

assistance of the tide, vessels were enabled to reach as high up the

Mersey as Warrington; but there they were stopped by the shallows,

which it was necessary to remove to enable them to reach Manchester

and the adjacent districts. Accordingly, in 1720, an Act was

obtained empowering certain persons to take steps to make navigable

the rivers Mersey and Irwell from Liverpool to Manchester.

This was effected by the usual contrivance of wears, locks, and

flushes, and a considerable improvement in the navigation was

thereby effected. Acts were also passed for the improvement of

the Weaver navigation, the Douglas navigation, and the Sankey

navigation, all in the same neighbourhood; and the works carried out

proved of much service to the district.

Anderton Boat Lift, Weaver Navigation. [p.125]

Picture Wikipedia.

But these improvements, it will be observed, were principally

confined to clearing out the channels of existing rivers, and did

not contemplate the making of new and direct navigable cuts between

important towns or districts. It was not until about the

middle of last century that English enterprise was fairly awakened

to the necessity of carrying out a system of artificial canals

throughout the kingdom; and from the time when canals began to be

made, it will be found that the industry of the nation made a sudden

start forward. Abroad, monarchs had stimulated like

undertakings, and drawn largely on the public resources for the

purpose of carrying them into effect; but in England such projects

are usually left to private enterprise, which follows rather than

anticipates the public wants. In the upshot, however, the

English system, as it may be termed—which is the outgrowth in a

great measure of individual energy—does not prove the least

efficient; for we shall find that the English canals, like the

English railways, were eventually executed with a skill, despatch,

and completeness, which imperial enterprise, backed by the resources

of great states, was unable to surpass or even to equal. How

the first English canals were made, how they prospered, and how the

system extended, will appear from the following biography of James