|

[Previous Page]

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WORLD.

By ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO.

(From THE

GIRL'S OWN

PAPER, 1881.)

[Ed.―see

also Isa Craig's essay, "Emigration

as a Preventive Agency."]

PART I.

"IN all the wide

world I wonder if there is a place where we are really wanted?"

It was a sad speech for a girl of nineteen to make to another

of twenty. But perhaps there are few, either men or women,

whose hearts have not known that bitterness at some time or other,

though it is oftenest on the lips of those who do not make

themselves very desirable blessings. She who uttered the cry

now might easily be forgiven for doing so. For when one has

been fatherless and motherless nearly all one's life, and has passed

from orphan-school to teaching in a boarding-school, and has for the

last three months looked daily through three newspapers'

advertisements of situations vacant, and written upwards of fifty

"answers" thereto, all fruitless, it is small wonder if one feels

disheartened and even despairing.

The elder girl, Bell Aubrey, did not answer for a few

minutes. She had had a life-history very different from that

of Annie Steele. For Bell Aubrey was the third daughter in a

family of eleven; and in the house of her father—a country

surgeon—there had always been joy and love, and simple plenty in her

younger days. It was only of late that the burden of life had

begun to press upon Bell. One of her elder sisters was an

invalid; the "boys" had got to be started in life, and five of the

younger children had still to be educated. Papa was growing

careworn, and mamma's eyes often "filled with tears." We girls

must be doing something," Bell had thought. "I must begin.

But for what am I fit?"

That was a serious question. It was in a secret hope to

find its answer that Bell Aubrey had gone to pay a long visit to the

Misses Brand, distant connections of her mother's, who kept a girls'

boarding-school. One of the Misses Brand had been indisposed,

and Bell undertook some of her duties, while Annie Steele was

temporarily engaged to fulfil the rest.

But Miss Brand was now convalescent, and so Annie Steele's

engagement was drawing to an end, and Bell Aubrey would be free to

return home. And instead of having found an answer to her

question, all the progress the poor girl had made was the

discovering what a very perplexing question it was.

She had never hoped that she might be a governess, for she

had no accomplishments; but she had had a thorough English

education, and she had thought she might be a school teacher.

Now she knew that she did not like teaching, and did not teach

well—that by the time lessons were over she had not cleared her

pupils' brains, but had only confused her own.

"It is dishonest to try to get a living by doing what one

cannot do well," mused straightforward Bell; "and, besides, here is

poor Annie, who loves to teach, and yet can get no engagement."

But when Bell heard Annie's despairing cry, she felt "this

would never do."

"Of course, there is a place for us,” she said, cheerfully.

"We may be quite sure of that. All we have to do is to find

it, only that seems the difficult thing."

"Those dreadful letters!" wailed the poor little teacher.

"After paying all my necessary expenses here, every penny that might

have saved from my salary has gone on stationery, and postages, and

advertisements. And what an investment it has been!You know

the answers I have got! Nearly all of them from school

agencies, telling me what a large connection they have, and advising

me to register at once, and then, as soon as I have paid my fee,

writing back that there is nothing on their books at present to suit

me, but that they will let me know when there is. And two or

three from people at the other end of the kingdom, offering me

sixteen pounds a year to teach everything to six children. And

then that terrible letter, Bell! That has done me more harm

than anything, because it has frightened me. I always knew

there were wicked people in the world seeking to lead others astray,

but I never realised that they were so near us. I feel like a

poor lost sheep in a wood, with wolves dogging it behind every

tree!"

"Poor little Annie!" said Bell, soothingly. "I am so

sorry you burned that letter after you showed it to me, for I would

have sent it to papa, and he would have given it to the police, and

the wicked people who sent it might have been punished, or at least

disturbed in their wickedness."

"Oh, I could not help burning it!" cried Annie. "It

seemed a disgraced to have had such a letter sent to one. And

then, Bell, even if I do get a situation, I shall never be able to

save money, not so much because the salaries are low, as because the

situations are so uncertain; and when one is obliged to leave, one

is sure to have to wait weeks and weeks for another, and spend all

one has on board and travelling expenses. It may be very well

for girls who have friends."

"No," said Bell, with decision; "it is not well for girls who

have friends, for girls who are doing work in the world should be

able to help their friends rather than be driven to prey on them.

I'm not at all sure whether it is not the way in which girls are

content to be propped up, and to think they may shuffle along

anyhow, in hopes they may get married at last, which has made things

so hard for working women."

"But most women do get married, of course," said Annie,

"especially girls with happy homes and circles of friends."

"Yes, certainly," said Bell. "But don't you think there

is something wrong in the way in which girls will spend their lives

doing fancy work to earn a few shillings for finery, spoiling their

health, and learning nothing which will be of any use to them

afterwards, instead of dismissing the servant and doing their own

housework, leaving crewels and so forth to those who have no servant

to dismiss, and who, being too poor to save, are obliged to earn?"

"But if many girls did that, what would become of the

servants" asked Annie.

"There are plenty of places for them," said Bell. "If

you knew all I know of domestic service, you would understand that

it would be a real blessing to them to find that they could not get

work unless they were really honest, capable, and respectable.

Besides, they are wanted everywhere. They are the only people

which are too scarce in England. And they are the very people

who are always welcome in the colonies."

"I wonder if there is a corner in the colonies for me!"

sighed Annie.

"I have wondered that, too," said Bell. "And the other

day I saw in the papers an announcement about a women's emigration

society."

"How you have thought over these things!" exclaimer Annie.

"And it is quite time," said Bell, gravely. "I must be

as self-dependent as you. At our house we keep no servant; my

mother and sisters do everything; and they have managed perfectly

without me for these four months. We can save no more at home,

and yet it is not enough. I must not think of going home

again. Your experience has convinced me of the uselessness of

advertising for teaching appointments. Annie," she added,

suddenly, "suppose we write to this emigration society, and see what

they can offer us?"

Annie caught her friend's arm in a tight clasp. Her

grave face was lit up. A breath of hope and adventure was

wafted over her Sisyphus-like life.

"We can, at least, see what they say," she cried. "But

your people will never let you go abroad, Bell."

"Yes, they will," said Bell "if the circumstances are such as

to make it right and fit for you to go, they will let me go.

My father is a wise man; he and I have had many talks over these

matters."

And so a letter was despatched to the Secretary of the

Women's Emigration Society. The girls kept that a secret.

"It will be time enough to tell anybody when we see what answer we

get," said Bell. And while they waited they went about their

work with a delightful feeling of enterprise and elation. Two

or three days brought back a little packet of circulars. Annie

Steele knew what it was when the servant laid it down beside Bell's

breakfast-plate, and Bell put it into her pocket unopened.

Both the girls sought their bed-chamber at the earliest opportunity,

and eagerly devoured its contents.

First came a statement of a public meeting at which the

objects of the society were discussed. Among the people

present were good and great men in many walks of life, ladies of

rank, and influential colonies perfectly familiar with the subject.

Attention was drawn to the fact that emigration is almost given over

to men, thereby leaving undue number of women in the mother country

deprived of their natural duties and employments, whether domestic

or industrial.

"People will say we go to look for husbands," murmured Annie.

"Never mind what they say," said brave Bell.

At this meeting it was further said that to the objection

often raised in England by women upon whom emigration was urged,

"How can I leave all dear to me?" it might be replied that there is

hardly a family in the highest class the members of which do not

travel and settle in different parts of the world and that surely,

then, other classes may do the same.

Another question, "How can a woman take her passage in a

merchant ship to find her way to a distant colony?" the Women's

Emigration Society was intended to answer, as all preliminary

arrangements together with adequate provision for the safe transport

and reception of emigrants, were now made by it.

Then a distinguished statesman said that he supposed there

was no parish in the United Kingdom which had not already sent its

contingent to the colonies, and that the class of educated women is

perhaps the only one which is not represented in them. He

dwelt upon the excellent arrangements made for the transport of

emigrants of all ranks, and the almost paternal care which many of

the captains show to those under their charge.

Then a colonial bishop rose and remarked that when he first

went to his work in the southern hemisphere he found that the

greatest want of the colony was the presence of women of a class

superior to those hitherto sent out by the ordinary mode of

emigration, and wherever he went he found the need growing still

greater.

Another bishop from a northern colony dwelt on the importance

of a careful selection of the emigrants, and of providing them with

specific recommendations to employers in the colonies. He said

that in his diocese there were Young Women's Christian Associations,

who made it their business to welcome persons from England, and to

secure situations for them; and that there is ample room for a large

influx of servants, and also for women, who, though they may not

have actually been in domestic service, are capable of practically

assisting the ladies of the family in cooking and household matters.

And the account concluded with a statement of the number of

women who had already gone out under the auspice of the society

during the first year of its working, and who were now doing well at

their respective destinations.

"I think it will do," said Bell Aubrey, though at that moment

there rose before her mind's eye a vision of the old house at home,

and the merry children shouting and playing among the ancient hedges

of the roomy garden. And it did seem so hard to have to go

away. But she said nothing. Why should she cry out,

because it was now her duty to give up what Annie Steele had never

had?

"I shall write one more letter to the society before I tell

father," she said. "I shall write and ask what it costs to get

to the respective colonies—in short, the step which should be taken

next by young women in our present positions, if desirous of

emigration. You see, Annie, we are as yet only seeking full

information; when we have obtained that, it will be the right time

to ask for counsel and consent."

Then followed a few days more of patient waiting, and then

came a little packet enclosed in the prepaid book-wrapper which Bell

had sent to the secretary along with the modest request.

The first paper the girls unfolded was a large sheet, which

set forth on its front page the principles on which the Women's

Emigration Society work. It stated its functions as―(1st)

"Collecting and distributing information from reliable sources

respecting each colony; its climate, resources, &c.; (2nd) arranging

for the comfort and safety of emigrants during transit to those

colonies, for which their circumstances appear to render them most

suitable; (3rd) establishing relations with trustworthy persons at

each port, who shall pledge themselves to receive and befriend the

emigrants accredited to them by the society; and (4th) raising and

administering a fund for the purpose of assisting, after due and

careful investigation, the emigration of suitable women of sound

health and good character, who are unable to raise the sum required

for the purpose, such assistance taking the form of a loan, for

which security is required and interest expected."

As Annie Steele read the last words her brightened

countenance clouded.

"It may do for you, Bell," she said, "but I have no money of

my own, and who would be security for me, even if I cared to start

in life under a load of debt?"

"But stop a minute," said Bell, turning over the page.

"Listen to this." And she read―

"Free or assisted emigration is still open to most of the

colonies for young single women who will register themselves.

The women must be of good character, and willing to perform domestic

service, as the agents in England are responsible to the colonial

authorities for the class of emigrants they send out; but, of

course, many of them are very rough. The accommodation is

divided into compartments containing eight or ten berths, with a

separate mess for each party. The present regulations in

emigrant vessels removed all the real dangers to which single women

were formerly exposed when on board ship. The best or saloon

end of the vessel is set apart for them, and they are not allowed to

quit it. A well-qualified matron is put in charge of them;

they are under strict rules and discipline as to leaving their

berths, taking the air on deck, &c."

"There!" said Bell, "I should be able to 'register,' as they

call it, for domestic work is exactly the work I want to do.

You are a governess, Annie, and wish to be a governess wherever you

go; but if you are willing to take a situation as a nurse or a

sewing maid till better chances are offered, I have no doubt you

will be allowed to register, too."

"But I don't believe your father will allow you to go in that

fashion," suggested Annie.

"I think I might persuade him," returned Bell. "Look at

the cost of the paid passages," she said, running her finger down

the next page, below items varying from eight guineas to twenty-six.

"If I can once prove to father that there is no hardship or

roughness which any good girl need fear, I think he many yield.

To put up with a few privations, such as the families of the

Mayflower pilgrims and of all other pioneers must have encountered,

is not a bad way of earning such a sum of money as that."

The other papers were simply a detailed report of work

already done by the society, and a schedule to be filled up by

intending applicants for its assistance.

"I shall write to father at once now," said Bell, looking up

from the papers with a set, steady face.

"It will all end in nothing," sighed Annie Steele.

"Your people will never consent, and I shall be afraid to go alone,

and shall have to go back to my hopeless advertisements and my

Tantalus successes."

"I shall go home in a fortnight from this time," said Bell,

not heeding Annie's sorrowing tones. "But I shall write and

tell father all about it while I am here. I think it may be

easier for him and mother to consider it all calmly while I am out

of sight. I shall tell them you want to go too, Annie.

There has always been a great deal about you in my letters home.

They say they seem to know you quite well."

There were some people who said that Bell Aubrey had a secret

for getting her own way. Perhaps Bell had a knack of

convincing people that her ways were likely to he right.

Perhaps one of Bell's secrets was that she always stated her case

temperately, making due reservations for the exercise of lawful

authority or of wisdom greater than her own; also, that she looked

facts in the face, and admitted the existence of unfavourable ones,

even while she brought forward others which seemed to her to

outweigh them.

She wrote how she found she did not like teaching, and how

many women were contending for every post that was to be had.

Then narrated her impulse towards emigration, and enclosed the

papers with which she backed it up. Next, she spoke of Annie

Steele's friendlessness and poverty. Emigration was doubly

desirable for Annie, yet Annie could not emigrate, except she went

in the humblest way. And if that could be right and safe for

Annie, it could not be wrong or dangerous for her. For if she

went, they might indeed spare the money to pay her passage, but they

could only do so by deducting something from money already needed

for the other children. Did not they know that she would work

very hard, that her brother next in age might get the

drawing-lessons he coveted so eagerly, and which might set free a

real gift struggling within hint, and so elevate and brighten all

his life—for that matter, all their lives? If they thought she

had a right to this passage-money, let them allow her to save it in

this way, and give it to him instead. And that would also

enable her to do Annie the service of accompanying her. And

they knew she always delighted in adventure!

It was two days before Dr. Aubrey's answer came.

"Dear Bell," he wrote, "your have made us very sorry—and very

glad. We are very sorry to think of parting from you, and very

glad to feel that one of our daughters is proving herself to be a

brave, true woman―a working bee and

not a destroying moth. I cannot go into all your arguments

now, and must think over them much longer and get much more

information upon the matter before I can give them any answer worthy

of them. You will not wonder that the thought or the first

child's going away, and going so far, touched your mother to the

quick. She cried out that when one of a family takes flight,

more are sure to follow the lead! But after the pain was over,

she realised fully that we cannot keep you all at home, and then she

thanked God, through her tears, that the lead you were giving was so

good and so unselfish. And when your poor lame sister said,

'What could we do without Bell?' our mother actually said, 'I can

see even that is a happier question than the other, 'What can we do

with her?' which so many households have to ask about their

daughters. All I shall say now is, that we cordially invite

Miss Steele to accompany you on your return home, and then we can

all think over the whole matter together, and at leisure."

And Annie Steele thought within herself, "They will let her

go after all. They have invited me there that they may know

the companion Bell is to have, and so be able to make a better

picture of her in their minds when she is away."

As under no circumstances were either of the girls to return

to the Misses Brands' school, they packed up all their little

belongings to take with them to Dr. Aubrey's. The good

governesses rather wondered that Annie Steele going away for a short

holiday, and with no engagement in view, could be so excited and

elated. Just at the very last, Annie confided their secret to them,

and found that they were aghast at its bare idea. They almost

frightened Annie by the picture of horrors which they conjured up. It needed all Bell's calm philosophy to restore her courage; most of

all, it needed Bell's reassuring, "We will see what father says." It

is only very foolish young people who chafe at authority; the wiser

sort know that it does not impose a fetter, but grants true and safe

freedom.

Beyond a very few words on the night of the girl's arrival at the

old green-clad house in the country, nothing was said on the subject

of emigration for some days. At least, nothing was said in the

general household. It is quite true that more than once Dr. Aubrey

took Bell to drive with him in his rounds among his patients. Perhaps it was then that Bell reiterated her telling arguments.

"If it is not right and safe for me to go out in this way, then it

cannot be right and safe for an orphan like Annie Steele. If there

is nothing worse than hardship and privation, then I must be a poor

creature if I cannot endure them that I may spare you so much money. Father, let me go. I shall be able to send you

home word if there

are any openings out there for my younger brothers, and if they

should go out, you would not feet so anxious about them, if I, quite

an experienced colonist, was there to receive them."

During those early days, too, the Doctor was taking great note of

Annie Steele.

"She is such a fragile-looking thing," his wife said. "Though Bell

is our own daughter, and I am likely to be fanciful and tender over

her, I should say she is twenty times more fit for hard work and for

roughing it than is this poor little fairy."

Annie was made free of the kitchen, and she expressed delight in no

measured terms for what was a real blessing to one who had spent her

life in schoolrooms and drawing-rooms. Annie was made free of the

garden, and could race and romp with the children without fear of

compromising tutorial dignity. It was a little difficult for her to

see children in any light but that of "pupils," but a few days'

experience of the young Aubreys made it easier. Annie's voice began

to ring out in merry laughter. The roses began to bloom on Annie's

checks.

"She's healthy enough," said the Doctor, who was a great gardener. "She has only been potted too long. She wanted planting out. Give her

plenty of active work and a due share of hope and joy, and she has

as good a chance of reaching a hundred years as most of us."

It was hard to tell when "out there" gradually changed to the more

definite locality of Queensland. For one thing, the society, when

applied to, recommended this colony. For another, the Doctor thought

its climate would suit Bell, and would be decidedly wholesome for

Annie. So they got the schedule for "applicants," and with a little

pathetic merriment they wrote out answers to questions as to age and

condition, health, religion, and capabilities, and stated their

determination to accept the free passage offered to any who could

describe themselves as "domestic servants." There was a little

debate as to how this could be done honestly in Annie's case, since

she wished ultimately to find employment as a governess; but as she

was quite ready to engage as a sewing woman or to give assistance in

any domestic duty within her strength, that difficulty was soon got

over. For Bell there was no difficulty. She could simply describe

herself as a "daughter at home," who had done household service in a

school, and was prepared to do it again, wherever she could find it. References as to character were, of course, easily obtained by both

the girls, and each got a favourable medical certificate. These

formalities being finally gone through, they were warned to hold

themselves in readiness to sail in a fortnight's time, which would

be about the end of March.

There was not very much time to be sad: there was so much preparation

to make. Mrs. Aubrey and her elder daughters winced a little when

Bell received the "Regulations for Female Emigrants." They brought

before them so plainly that their bonnie pet was going to seek her

fortune as a simple working woman. But Bell did not wince; she said

there was some comfort in seeing that female necessities in the way

of garments could be reduced to the bald list of "the lowest

quantity that can be admitted"—to wit, "six shifts, two warm and

strong flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of

strong shoes, two strong gowns—one of which must be warm." She was

not sure whether life, even if really reduced to such necessities,

might not stand a chance of being truer, more wholesome, and more

womanly than life under conditions stringently requiring frills and

flounces.

As for the Aubrey boys, they found fine fun in the description of

the "ship kit" with which the girls would be provided on payment

by each of £1, which seemed, indeed, a very moderate sum to buy "a

pillow and a bed, a rug, two sheets, one wash-basin, one plate, one

pint drinking-mug, one knife and two spoons, three pounds of marine

soap, and a canvass bag."

As a matter of fact, Bell and Annie took with them considerable

outfits of a plain, serviceable kind. Old under-linen and stockings,

even of extreme "holiness," as Bell expressed it, were utilised for

voyage use, to be worn through once more and then thrown overboard,

to spare the labour and discomfort of ship-washing. Each girl was

provided with two robes, made in easy dressing-gown fashion, the

one of dirk flannel for use during the colder parts of the voyage,

the other of strong "Oxford shirting" for the tropical regions. For

head-gear, each had a thick wadded hood, and a light straw hat of

wide, antiquated shape, which Bell picked up for a few pence at a

village shop. In the matter of shoes they happened to be

particularly fortunate—friends of Dr. Aubrey's presenting each with

a pair of "alpargátas," an article worn in Spain and Spanish

colonies, and which might be introduced into this country with great

advantage, since it gives the maximum of warmth and protection from

damp with the minimum of weight and noise. When Bell put them on she

said she felt "like a cat." The upper part of this shoe is roughly

made of any material (in this case it was white canvas), tightened

across the instep by bright-coloured braid, while the sole consists

of fine rope twisted and bound into the proper shape. The article

might form a new-industry for the blind or for cripples, and has

many special advantages for wear in kitchens or in hospital wards.

They found they would not be allowed to take trunks into their

berths, and that the clothes for use on the voyage would have to be

contained in the "canvas bag." So they each made themselves a second

and smaller bag, which they stocked with underclothing-neatly cut

out, which they could make up during the leisure of the three

months' voyage; and being duly warned that they would find such

leisure very long and tedious, they further provided themselves with

materials for lace-work, selecting them as capable of being packed

into very small compass. They provided themselves with plenty of

foreign writing paper, a big and strong travelling inkstand, some

pencils, and a few sheets of stronger paper for possible sketches.

Inquiry proved that the ship commissariat would be ample and

wholesome for all ordinary purposes, but that emigrants usually

provided against emergencies by a few little dainties of their own. Therefore they procured an ordinary tin biscuit-box, which they

stocked with the following creature comforts: two pounds of good

tea, a pound of fine sugar, a small box of figs, a pot of Liebig's

extract of meat, and a bottle of strong home-made calves'-foot

jelly.

There was a goof deal of fun over these little arrangement, and the

many wild suggestions which were made. The interest in the girls'

adventure had spread beyond the Aubrey household, and they were for

the time the heroines of the neighbourhood.

"How happy everything seems!" Annie Steele mused, as she jogged home

in the Aubreys' old chaise, through sweet new-budding, English

lanes, steeped in silvery moonlight. "I have just learned to love my

country and to find how kind its people are, as I am going away. But is there not something like

that all through life? I have heard

old people say that we have only just learned how to live when it is

nearly time for us to die. It seems sad, if one looks at it only in

one way, but not in another. Perhaps it is God's way of teaching us

that love is the only-true possessing, and that this life is but the

school for another."

There was a little pathos in packing the trunks, which would be

opened and unpacked so far away, and amid such different scenes.

Bell would pack hers entirely herself, the secret of which she

confided to Annie.

"If mother or the girls did it, I could not bear to lift out and

unfold the things when I get there!" she said, looking straight into

Annie's face. Annie's own eyes filled a moment, but Bell's remained

bright and dry.

Those trunks were most sensibly stocked. No ready-made bonnet or hat

was taken; only useful materials for the same, nicely prepared, were

neatly packed away. Then followed some plain dresses suitable for a

hot climate, and a pretty store of neat ribbons and washing frills,

folded up "in the rough," together with packets of buttons, marked

stockings, thread gloves, and other little sundries which would

spare the young emigrants' purses for a long time after their

arrival. They had a due store of well-chosen books, each of them

with some dear autograph in it, mostly flanked by a date or the

name of some place, which would serve to keep tender memories alive.

One friend contributed a few sheets of the newest music. The invalid

Miss Aubrey set herself busily to copy some simple "out-line" work,

which adorned the bedrooms at home, and whose replica would take

little space in packing, and give a kindly welcoming look to the

strange home in the far-off land. Another sister added two or three

hand-painted wooden plaques for the same purpose, while a little

portfolio was made up for each girl containing as many slight

sketches, small engravings, &c., as could be mustered.

At last came the letter from the secretary of the emigration

society, bidding both the girls to be ready to go one shipboard at a

southern port in the first week in April, and announcing that six

more young ladies were also starting out under the same auspices,

and that the eight would have the advantage of berthing and messing

together, and so escaping all immediate contact with any rougher

element.

Bell put in a petition that they should say "good-bye" at the

familiar green gate of the old home-garden. "I should like to have

my last look of you, all standing together," she said. "You could

not all come to the sea-port, even if we could afford the expense,

and we should not leave a sweet last impression on each other, if we

parted after a day or two of fagging in railway carriages and among

our luggage."

And to her father she said, "Mamma, could not come you know, and it

would be terrible for her not to have you beside her in the first shock

and silence of our going away."

And to her sisters she said, "Dear Alice cannot leave her sofa, and

it would make her feel her weakness so much to have to stay behind

while you came with us."

And to her mother she said, "It would be very trying for papa to

have to part from us at last in the crowd at the depot, and to return

alone by the same road as that on which we had accompanied him."

Once more, Bell got her way.

But to Annie Steele she said, "All I have urged against their seeing

us off is true, but, above all, I did not want them to have too

vivid a picture of the hardships we are encountering. It is

harder to see what others have to bear than to bear it oneself; and

things always look at their worst at an embarkation, and it is not

easy to realise how much better they will be when everybody has

settled down and the ship is out of dock and on the broad, free

ocean."

So at last they said "good-bye." Bell even persuaded her father to

humour her "last wish" by not driving them to the railway-station,

which was twelve miles from home. The two girls kissed and hugged

them all, and then went back into the house to stroke the cat, and

came out and kissed and hugged them again, and then took the reigns

into her own hands and drove steadily off without looking back till

she was so far off that they could not see her face, and she could

only discern their forms against the bright spring hedge. There,

just where a turn in the road would hide them and the old home from

view, she stood up in the chaise and waved her handkerchief—once,

twice, thrice; and then as the old horse jogged on again she dropped

into her seat and gave way to one storm of tears. It was not very

long, but when it ceased it seemed to Annie Steele to have taken

something from Bell Aubrey's face which never came back again.

But all she said was, "Now we must begin to take notice of

everything pleasant, for the sake of the first letter home."

PART II.

HOW the two girls got through their railway journey they never quite

remembered. Poor Annie Steele sat wide awake, dreamily looking at

the landscape they were flying past, and vaguely thinking over the

dull, monotonous details of her life, over whose dreariness there

now gleamed a pale ray of that tender sunshine which always

illumines the past. She did not speak to Bell, whose dry, glazed

eyes and clenched, burning lips told their own tale. Only once, when

between station and station they chanced to be alone, she put out

her hand to clasp Bell's, but Bell's was hastily withdrawn. Only for

a moment. The next instant it was outstretched and folded about

Annie's. Bell was of too generous a nature to repel sympathy, even

when her heart was so sore that its soft touch wrung it.

But when the girls alighted from the train at Plymouth they felt as

if they had awakened from a troubled slumber. There lay the little,

wild, scrambling seaport town, full of hearts which knew all about

the pains of parting and the aching longing of absence. And there

stretched the wide, sunny sea, and there was the soft summer sky

bending over it. Bell stood still and drew a long breath.

"When one is out in the open air," said she, "it seems always as if

there was time for everything. I think God's days are long, so that

we can spare to lose sight of each other for a little space, while

we do our business and His."

They took a cab and drove straight to the emigrant depôt. Annie

Steele winced a little as Bell gave that address to the cabman, and

he received it with so matter-of-fact an air that she felt her

shrinking had been quite unnecessary.

"He must have driven others not so very unlike us there before,"

pronounced Bell. The depot was a huge building, situated in a corner

of the harbour, and enclosed by gates. The girls' hearts sank a

little when they found that, having once entered it, they would not

be permitted to leave it till they embarked on the tender which

would convey them to the emigrant ship.

This they found would not take place till Thursday, and this was

Monday. One or two of the lady emigrants had obtained this

information beforehand, and had stayed with friends in lodgings in

the town; but others of their party who, like themselves, had come

from a distance, like them also had taken up their abode in the

depot.

There was nothing to be done but to make the best of things, and the

utter novelty of all surroundings made some matters endurable which

might have otherwise been hard enough. Despite the medical

certificates already obtained, they underwent another medical

scrutiny, and were then free of the establishment, and at liberty to

introduce themselves to the community of which, for the next three

months, they would form a part.

A handsome, dark-eyed young woman, neat in attire and peasant in

manner, looking something like the daughter off a respectable farmer

or shopkeeper, came forward to meet them, and saying that she

fancied they "must belong to our party," offered to introduce them

to the others, to show them the place, and to "explain things."

"My name is Miss Gunn," she said; "I come from Shropshire. I arrived

here this morning. Everything seems very queer at first, but I

suppose we shall soon get used to it. And our party will keep

together. It's not the tin pannikins and the cleaning-up which

signify much—it's the company. I'm afraid that some of it, not of

our party, will not be too select."

"I suppose not," said Bell. "You know the secretary never said there

would not be hardships, but only that we should encounter nothing

that a good woman need shrink from."

"These are our beds," announced Miss Gunn, leading the way to a long

room with great windows overlooking the beautiful harbour. Annie

Steel gave an involuntary-grip to Bell's arm. How queer and dreadful

these beds looked!—like nothing so much as tiny "four-posters" all

stuck together, with nothing but the posts and a narrow ledge to

separated them.

"You are lucky in being two friends," said Miss Gann, with a comical

grimace. "For we sleep two in a bed, and you two will keep together. My bed-fellow to be has not arrived yet."

"Why! there are two rows of beds, one beneath the other!" exclaimed

Annie Steele.

"Oh, yes," said Miss Gunn, "and I have not yet made up my mind which

is the greater drawback: to have to mount on high when one goes to

one's rest, or to creep into the lower shelf and feel as if a

mattress was coming down to extinguish one. But hark, there's the

bell for supper! We must go down at once, though I hope you are not

hungry, for we have always to sit waiting nearly half-an-hour before

the meal is served. We 'mess' ten at a table, but on hoard, they

say, the mess consists of only eight. One of each ten is called the

'captain,' and she appoints two 'butlers' each day. I am one to-day. Of course, we wash up and sweep the floors ourselves; that is the

duty of the 'butlers' for the time being, and oh! the knives were

dirty to-day—dirty with ancient dirt—but we shall have fresh ones

when we go on board."

"Is the matron here yet?" asked Annie Steele.

"Oh, yes," replied Miss Gunn.

"And of course she is kind and nice," observed Bell Aubrey.

"She is like a little cackling hen," was Miss Gunn's rejoinder.

"I don't think our new acquaintance looks on the sunny side of

things or people," whispered Bell to Annie, for she felt by the

tightening grasp of Annie's little hand that her companion's heart

was sinking.

But Annie's spirits were somewhat revived by the sight of three or

four nice girls who came to their mess, and who, belonging to their

party, would remain their nearest companions through their long

journey. Of course, even names, still less histories, could scarcely

be learned at first sight, but shrewd Bell was not long in forming

certain opinions about these more interesting fellow-travellers. There was the sensible, worn, rather weary-looking spinster, Miss Wylde, who had probably trodden other people's staircases, and sat

at other people's tables, till she found the competition for even

such humble dependency waxing too strong for her, and who was not so

much going out to a new country as being driven forth from the old

one. And there was Miss Thorpe, strong and countrified, physically

fit for the roughest farm service, and yet with something of

breeding and mind that might well make her prefer the harder life

and higher chances of a young community to the pampered menialism

and rigidly limited range of an old civilisation. And there was Miss

Gunn herself, energetic and wiry, with a suspicion of acidity and

unrest, which might have mitigated her friends' regret in parting

from her. And there was the pale, picturesque-looking person who

called herself "Agnes Perceval"

without prefix of Miss or Mrs., whose voice was so low and sad, and

whose dark eyes seemed ever fixed upon some vanished scene.

"Now, Annie," said Bell, softly, as the two walked up and down the

little bit of the quay which belonged to the deport, "there is

hardly anything in our new life just now which has not a pathetic and

a comic side. We may think of the pathetic one, but I think we'll speak

of the comic one. Is it not funny to find that our food is suddenly

become 'rations'? I mean to send home all particulars about these

rations, and then the dear folks will be certainly convinced that we

are not starved. We cannot say we have a very limited dietary

either, Annie. It contains everything necessary and wholesome, and

some decided luxuries. You see it includes beef, pork, preserved

meats, suet, butter, biscuits, flour, oatmeal, peas, rice, potatoes,

carrots, onions, raisins, tea, coffee, sugar, molasses, mustard,

salt, pepper, water, and actually mixed pickles, and lime juice

twice a week! Do you you suppose Christopher Columbus had such

fare? Why, Annie, I begin to think that by-and-by everything will

be made so easy and comfortable for everybody everywhere that there

will be no chance for heroism. I declare I am cheated out of my

dream of adventure. The molasses and the mixed pickles detract from

the glory of a pioneer."

And then there was silence, for Annie could not altogether respond

to Bell's high hearted appeal. Rather too much of the glory of

hardship and adventure still remained for her. Amid the constant

shock off strange discomfort she could not help building new hopes

that things would be better on the ship.

But after the day of embarkation had come and passed, and they were

all fairly on board, when Annie ventured to resume a diary-letter

which she had promised Bell's invalid sister should be kept and

forwarded home on the first opportunity, and in which she had

already described the depôt, the first line she added was:

"I have told you all about the depôt—now for the ship. It is very

much like it—the same four posters, with hardly room to move down

the one side that is not joined to other beds. And we eat in the

same room, cook is the same room—one room common to a hundred

girls, or rather some of them are uncouth, rough Irishwomen. There

are few among our 'mess' who can take things as bravely as Bell

does, or even as I do, for having her with me keeps me up. We are

now recovering from what was only to be expected. Some of us are not

well yet. Bell was very ill at first, only I was not sea-sick; only

directly I went below deck the first night the smell of the room

turned me faint. But the 'rolling' of the ship has no such effect. At last we have got the place into something like order. I have been

down on my hands and knees this morning, doing some honest

scouring―such a floor as I have never seen anywhere but in an

Irish cabin. I am thankful to say that 'our mess' are all once more

on their feet. We are a pattern of order. You never see waste in our

quarter, and our tin things are always clean. We have a farmer's

daughter among us—Miss Thorpe; she is our cook; and we had a very

good tart to-day. So you see we make ourselves comfortable in spite

of circumstances; in fact, after a little sea air, we are rather

oblivious of our surroundings during meals. But this happier state

of things is only just beginning. The coarse habit of some of the

people during the first few days were simply abominable. I think

many of us would have turned back if we could, but it only seemed to

rouse Bell's courage."

A few days later Bell took up Annie's pen and continued her

narrative―

"Things are looking brighter and brighter. For about a week we

'tipped it up lively,' as some of the Irish girls sang, but today we

are becalmed. There are one or two vessels in sight, all like

'painted ships on painted oceans.' Oh, it is warm—and yet we have

been only one week on the water. Our party are getting more

sociable as they get better, and we all feel we are having a regular

holiday. I bought a chair at the depôt, and to-day have been

sitting with a book in my hand, but did not read mach. I am all

bruised from the knocks I got thorough the rolling of the ship, and

as we do not sleep much at night, we cannot resist it during the hot

day! Though this is the matron's sixth for seventh voyage, she suffers

from sea-sickness, and is keeping her cabin still, though we are all better.

There two sub-matrons, one an Irish girl, the other one of 'our

mess,'—both very nice girls. Our party are in very good favour; when we send

our dishes to be baked them ship's cook improves them, and the

officer are all most polite to us; but the Irish have a sort of

league among themselves, and are very jealous of everybody. They

have threatened to murder one of the sub-matrons when we land. I must

tell you something about our doctor, who is always a very important

personage on an emigrant ship. Ours is a jovial, amusing fellow, who

calls us his "seven and sixpences," and tells us the funniest little

anecdotes, which we only half believe. We all bother him to let us

have our boxes up, and he says the word "box" will be found

written on his heart, and tells us of a man who came on board a

vessel at Glasgow, bound for Sydney, and whose box got lost and

could not be found during the voyage. Wherever anything went wrong,

or any accident happened, that man always shook his head and

hinted that if he could only have got at his box he could have

repaired the damage, or done whatever service was required. On

arriving at Sydney the famous box turned up among the cargo―a

box,

says the doctor, 6 feet 4 by 3, and anxious to see what a box so

large and so light (for it was light) could contain, he stood by

while its owner opened it, and there he saw—a hat, an old pair of

shoes, and four red hearings! This story is told to insinuate what

he thinks of our declarations that we could be quite happy if we got

our boxes. We are about the line now, and have only seen land once,

and that was the Cape Verde Islands. I am to be 'watch' to-night;

the duties are to sit up half the night, to give alarm in case of

fire breaking out or water coming in, to shut the ports, if stormy,

and keep the lights burning. I have been 'watch' once already. Next

week I shall be 'on duty,' which means that I shall have scrubbing

to do, the washing of our mess utensils, &c. I had rather my turn

had come in a cooler part, but I shall be glad when it is over. Annie has had her turn already, and got through it very cheerfully. I think she is contented now.

I am really enjoying myself. There is a

very decent library of fiction on hoard, but the supply of fancy

work to occupy us, of which we were told, is a delusion and a snare. I am glad we brought work of our own, but we might have brought a

great deal more. Ours is the only 'mess' that has not quarrelled; we

set quite an example of sisterly love and community. The captain

reads service to us on Sunday morning, and in the afternoon fathers

and brothers visit their respective relations. We have a dog, a

canary, and two cats on board."

Later on, Annie Steele resumed the task of reporter.

"On Friday last we saw a meteor. It was

like a flame or fire proceeding from a star. The flame

disappeared, as the meteor shot across the sky. It fell into

the sea with a tremendous thundering noise, that I thought would

never cease. The heat in the cabin keeps one in a continual

bath. As soon as we are down there for the evening we put on

our nightdresses, and find them more than sufficient clothing.

I must tell you about the cleaning. Before breakfast we take

out the boards from the underneath beds, and scrub the boards with

dry sand and a heavy stone, then sweep the floor. After

breakfast, we wash up, scrub forms, tables, cupboards, and painted

walls with soap and water; then take a kind of hoe and scrape the

floor, sandstone, and sweep, during which time you require to take a

towel half a dozen times to dry yourself! We have

had a little rain during the last week; very heavy showers—so

refreshing. The phosphorus at night is very pretty, and the fish in

a calm look like emeralds. Such quaint groups of people as we see

around us it would take volumes to describe. We both look at all

your photographs every night, and――"

Here the letter broke off abruptly, and in a rapid, large hand was

added—

"Ship is just starting!"

There seemed to have been no time for any last message, or for even

a signature. Some sudden opportunity had evidently been suddenly

seized. When the letter reached the Aubreys it looked

travel-stained, bore no postage stamp, but was charged only regular

postal rates, being marked "ship's letter."

PART III.

AFTER the arrival

of that most welcome but half mysterious "ship's letter," the

Aubreys had to wait a long while before one came with the pretty

Queensland postage stamp and the Brisbane postmark upon it; but it

came at last, and was opened and read with eager, trembling

interest.

"All my darlings at home," Bell began. "We are here, safe and well,

at last, and as there is scarcely anything to add to our budget

about the voyage—for one day is very like another at sea―I will tell

you about that budget, which I do hope reached you in safety. I

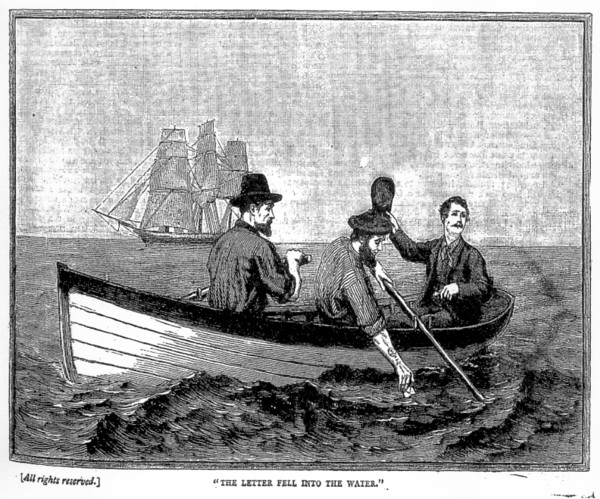

suppose you guess we sent you that letter a passing ship. We got only

three minutes' notice that there would be a chance of sending home

letters. None of the other passengers had time to prepare anything,

only, you see, we had obeyed your 'wishes, and written ours by

degrees. We had not even time to sign it, only to find an envelope

and direct it; there was not even time to seal it, the captain

kindly threw it to the little boat as they pushed off to the other

slip. The letter fell into the water, but they fished it out again, and the

captain shouted to them to seal it up for us, and further than that

I cannot tell its fate, but we hope it reached you.

"And now I will go on to our landing. As we sailed up Moreton Bay

towards Brisbane, we found nothing very striking in the scenery,

only it was a treat to our sea-eyes to see any scenery at all! It

was quite plain we were going to no out-of-the-world corner, but to

a very busy place. Steamers and craft of every kind were passing in

and out, and when we got into the Brisbane river the shores were

covered with wharves and warehouses and works of every kind, while

on the wooded heights behind we caught glimpses of stately villas

and pretty cottages. A steamer came down the river to take us off

the ship, and on that steamer was the lady (Mrs. F—) who had

undertaken to meet 'our party' on behalf of the Women's Emigration

Society. We were all allowed to stand with her on the bridge of the

boat. When we reached the pier, we watched for our boxes to be

passed out, and then drove straight away from the depôt. Of course,

had there been any mistake about the time of our arrival, or any

other misadventure which had prevented our being met, the depôt

would have been a safe though perhaps not a very pleasant refuge. Mrs. F—, in her kindness, would fain have acted hostess to us all,

but as in her own house she could only comfortably accommodate one,

we decided that that one should be the sub-matron from our party;

for, of course, she had had a great deal of responsibility during

the voyage, and deserved the most consideration. Mrs. F— knew of

respectable temporary lodgings for all of us. Annie and I and Miss

Gann went to a nice little house belonging to a person whose

daughters keep a school."

Then came a parenthetic paragraph.

"After writing thus far, it occurs to me that I will keep back my

letter for a few days, in hopes that I may have some definite news

to give you."

Then followed a later date, and the narrative went on.

"Hurrah! Annie Steele has got a situation as daily governess. She

did not get it through the society, but by answering an

advertisement. We have left our temporary lodgings and gone to

board with some friends of Miss Wylde's. Annie and I share one room;

she will have have to pay £40 a year, but I am to get my board free,

in return for my household help while I am waiting to hear of

something better. The teaching Annie has got already will exactly pay for

her board, and no more, but then she only goes to it three days out

of the six, and the family are very kind to her, and she hopes to

fill up the other three days soon, and so earn twice as much. I

think this bright climate is doing Annie good. She seems always

bright and happy and in high spirits, and you may guess her energy

when I tell you that she has already sent a pretty painted panel to

the Brisbane Art Exhibition! I don't think Annie feels half so

lonely here as she did in England. There are so many people in this

place who are lonely too, and I fancy a number of lonely people make

up something like a large family.

"And now that I have told you where we are and what we are doing, I

suppose you will like to hear something of the place, and of our

impressions of things in general. Everybody here seems comfortably

off; nobody is very rich, and there are no destitute classes. Brisbane itself looks like an incomplete place. Splendid buildings

stand side by side with rickety sheds. I have heard it said that

'Queensland is a fine poor man's country,' and I think it is true:

the necessaries of life are cheap, but anything in the way of luxury

is dear, and so is much that we call 'comfort,' and the people seem

very careful of their money. In the house where Annie and I are

staying there is no servant kept; nobody keeps a servant here who

can possibly do without one. Many of the ladies who receive

you in pretty caps and laces in the afternoon, in their own drawing

rooms, have spent their mornings in the kitchen and done all their

own work. This is a most hard-working country. All the houses have

verandas: in many the rooms are all on one floor. The houses

themselves are mostly of wood, the boards of which are beaded and

fit into one another, so that there can be no cracks. The rooms

generally are very small. Annie and I share one; we have hung

up

all the crewel work we brought out with us, and what with our little

ornaments and photographs, and some home-made brackets, Annie says

that, despite its rough boards and rafters, it is the most unphilistine-like apartment she has seen here as yet.

"The climate is simply delicious; but it is winter here now, and

everyone talks of being roasted in summer. The flowers and fruit

remind me of what our friends from Ceylon used to tell us, and

Chinamen come round with fruits and vegetables in baskets as they

said the Singhalese people did. The children here are fearfully bold

and 'terrible.' The street boys are a terror to wayfarers at night. These boys are called 'Larrikins.' We hear sad stories of the state

of morality in the town. Wines and spirits are mixed with sleeping

draughts, when made to be drunk on the premises of licensed houses,

and the consumer is robbed, and when he comes to his senses is told

that he has drunk the value of his money. It is on sheep-shearers

coming into town from the country that this trick is most frequently

practised. It is awful to know that some of the girls who came out

with us went straight to ruin the second day after the arrival, in

much the same way as the shearers, only, of course, more to their

utter ruin, and some of them were those who had seemed nice steady

girls on board.

"I cannot advise a flood of female emigration to this place under

present circumstances. It may certainly be a good opening for

sensible young women fit for hard work and willing to do it, or for

women who have friends or connections here, or a little capital. Annie and I have been exceptionally fortunate, but, you see, we are

only just paying our way, with not a penny over towards those extra

expenses which must come, even to the most economical. Others of our

party have got nothing whatever to do yet! Miss Wylde came out

believing herself to be engaged as governess in some state

official's family, but when she arrived she found they had secured

somebody else: though they would have got her a situation of some

sort. Fortunately, she had friends here to go to—the Roys, the

family with whom we board and with whom she also is living. I do not

think governesses are much wanted here. The grammar school in the

town ruins them and the private schools, and chances of teaching

up-country are few and far between. A man calling himself a

'reverend' wrote up for half -a-dozen governesses, but Mrs. F— says

he is a scamp, and would not let any of us communicate with him. The

people most in demand are lady-helps, but the work required is rough

and the pay small—I have not yet heard more than £20 offered. Under

all these circumstances, could one recommend girls to come out here

on a loan, either from friends or from the Society, for how could

they ever pay it off? Mrs. F— says that the first batch of

lady-emigrants whom the Society sent out all got comfortable homes,

free off expense, till they got good situations. But they tired their

entertainers and went off to their work so reluctantly, that the

colonists have left the late-comers to pay their own expenses and

shift for themselves. Even in my short experience of life I have

been often struck by the reckless way in which people spoil

blessings; they don't take them as 'talents,' to be increased in

value as they pass them on, but they wear them out, and make them

'second-hand articles.'"

In due course, other letters followed. Annie Steele presently got a

double set of pupils, so that she was comfortably provided for, with

a modest margin for saving. And when Bell Aubrey had an offer of a

lady-help's situation in a farmhouse, the Roys found they could not

bear to part from her, and entreated her to stay on with them, at

the same salary which the farmer was willing to give, namely

£25―and Bell, delighted at remaining with Annie, and among faces

already grown familiar, gladly accepted the offer.

She wrote, by-and-by—

"Through Mrs. F—'s goodness, and the kindness of Annie's employers

and the cordiality of the Roys, we have got into quite a pleasant

society. When there is a good public entertainment in the town,

Annie generally goes with her pupils and their parents, and we are

constantly asked out to homely little evening parties in South

Brisbane, and even to the 'musical evenings,' charades, &c.. of the

most fashionable quarter. Annie actually went with her pupils to the

entertainment given by the Mayor to the two young Princes when they

were here. We are certainly very happy—only the length of time it

takes to receive an answer to a letter makes us realise the immense

distance which stretches between us and all whom we love. But though

I can say this, and say it truly, yet I could not advise any girls

to come out here to fight their own battle, except those who know the world

thoroughly and are able and willing to turn their hands to almost

anything. It is not fancy-work lady-helps who are wanted, but women

who can really take a servant's place, scrub, wash, and cook. Women

like these could easily get a living in the old county without

exile, with gentler surroundings and with, I think, much better pay,

especially considering the relative prices of clothing, &c. Of course, you can

see from what I have told you that social conditions are somewhat

different here, but I feel sure, even among the prejudices of

English life, that whatever work ladies did would soon become

lady-like! And many women who might not have the physical strength

to bear the hardships of the voyage and the hard life out here,

might have the moral courage to contend with the remnants of caste

at home—especially as those remnants are already getting out of

fashion and descending to the vulgar and pretentious classes.

"If English girls of a better classes are to be found willing to leave

home and friends and to face all sorts of hardships, and to counter

great risks and difficulties to earn £20 per annum by doing real

servants' work simply because the public opinion of the strange

country does not ostracise them for so doing, then I cannot help

saying that English men and women, heads of households at home, and

English girls of the better class seeking employment, have in their

own hands the solution of the great 'domestic servant difficulty,'

which, as mamma used to say, makes so much English female life one

perpetual struggle and defeat.

"But because I think that many women—and men too, for that

matter—might do as well at home as in the colonies if they were

prepared to encounter the same hardships and labours, do not imagine

that therefore I think women ought not to emigrate. Where the men of

a nation go the women should go also. When I see some of the evils

and miseries of society out here, and remember the evils and

miseries of society in England, I feel that the one-sided way in

which emigration has been too often carried on has much to answer

for. Society in the colonies is apt to be bare and coarse for lack

of the gentler elements of life, and the society at home to grow

vapid and indolent through the elimination of its stronger ones. When sons and brothers and friends and neighbours go abroad, I think

it would be well if their womenkind and their dependents went with

them, instead of getting assistance or support sent to them from

abroad. I know that this would involve a great deal of

self-sacrifice and courage on the part of such womankind and

dependents, but, then, everything that is worth doing involves

self-sacrifice and courage. The Bible says that woman was made to be

the helpmeet for man, which means, I should think, that she shares

and dares with him while he wants help, not that she comes in like

a base camp-follower after the victory to divide the spoil! I am

glad I came out here. It is the right thing for some women to do,

only they should do it knowing exactly what will be expected from

them and

what they must expect."

Mrs. Aubrey sat thoughtful with a half smile on her face after she

read that letter. At last she said:

"I expect Bell will have some important news for us soon."

Her motherly instinct was right. The name of a Mr. Edward Wylde, a

brother of Miss Wylde's, had appeared more than once in the girl's

home letters. And at last there came one about nothing else but him,

because Bell had promised to marry him as soon as he could build a

little cottage on the pretty "lot" he had bought by the river.

Annie Steele wrote about him too, "Because," she said, "I know you

will like an impartial judgment concerning him, which dear Bell's

cannot be. Through our association with his sister and the Roys, we

have seen him almost daily since we first arrived. I feel it like an

insult to him to say how steady and good he is. I have scarcely ever

seen him without a smile on his face and a pleasant word on his

lips. He is one of those people who are always ready to help

everybody and who hinders nobody. Yet he has a firm will of his own,

and a strong sense of right and wrong, and recognises no

in-betweens. He has been taking such pride and pleasure in getting

ready his married home. It is the sweetest little house, with one

pleasant living room, a tiny kitchen, one large bedroom and two

small bedrooms, and a lovely garden stretching down to the river's

edge. They have planted two young palms beside the door; and they

are to be called 'the Doctor' and 'Mamma.' All the

domestic-plans are settling down most happily. Miss Wylde, his

sister, who has had two or three uncomfortable situations, is to

take Bell's place at the Roys. Bell will do all her own domestic work,

at least at present and as Edward Wylde often has to be away from

home for a day or two on business, I am to take up my abode with the

young couple, continuing my daily teaching and paying for my board

as I

have done at the Roys, but giving Bell the inestimable boon of my

cheerful society, during the early mornings and the evenings of

her husband's enforced absences. We mean the wedding to be very

quiet and pretty. Heigho! I always told Bell that people would say

we came out here to get husbands. And she said we had to do right

and not care what people said! And if any girl says that she

shrinks from starting for the colonies for fear she would not be able

to contrive to keep single, tell her I have been here two years

already and have not had a solitary offer!

"Bell says it is so nice to reflect that if, as years pass on, you

think some of her younger brothers should try colonial life, there

will be a home for them to come to, and experienced friends to meet

and advise them. Whether Bell has children of her own or not, I think

she will be one of those whom the Hebrew historians called 'a mother

in Israel.' And these are the sort of women who are wanted in new

countries."

THE END.

――――♦―――― |

|

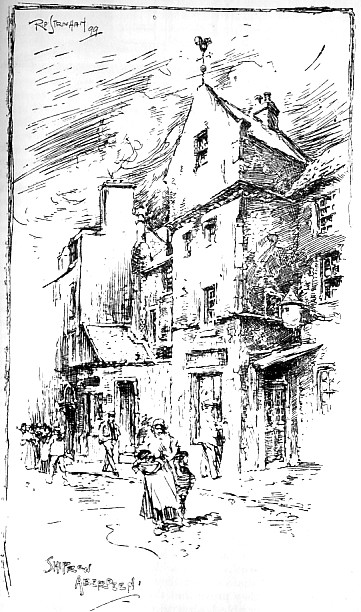

THE STORY OF ABERDEEN.

I.

BY ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO.

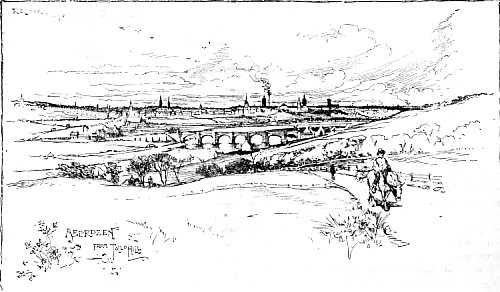

ABERDEEN,

from Tollo Hill.

ABERDEEN is among

the early names which emerge from the mists about the cradle of

Scottish history. Yet to many "Southrons," it is known chiefly

as the point from which tourists diverge to visit the Queen's

Highlands. It is said that "in a Gazetteer published in this

century, Aberdeen was described as a small fishing village on the

east coast of Scotland, the inhabitants of which live chiefly on

fish and seaweed." Within the last twenty years the

metropolitan illustrated papers have set forth the citizens as

arrayed in kilts—a picturesque garment, alas! never seen on Aberdeen

streets, save when worn by a Highland soldier or a dramatic English

tourist.

It is hard to realise how Aberdeen must have looked before

Union Bridge spanned the valley which cuts through it and made

possible its noble Union Street, with the lofty tower of the fine

County Buildings at its east end, and the massive block of the Free

Church College to the west. Only a century ago Aberdeen had

but ten streets and about twenty thousand inhabitants. Now its

buildings cover a considerable mileage; it has more than sixty

places of worship, mostly well supported and fully equipped with

schools, classes, guilds, and kindred agencies. Its population

numbers about 126,000. It has a large infirmary, well

appointed within, though the external aspect though of its newer

sections certainly adds much to the dreariness of the dwellers in

the huge tenement houses whose windows look upon them. It has

a splendid market, both for vegetable produce and fish. It was

opened in 1842, and though it has since been destroyed by fire, yet

the original plan has been closely adhered to. Friday is

market-day, and then the market presents a pretty and lively scene.

White mutches and short blue skirts are still visible among the

fisher-folk and a few of the country-women; but, alas! recent years

have watched the gradual disappearance of the older generation of

fish-wives, with their high Norman caps, trimmed with real lace, and

their long earrings of gold or silver. Aberdeen butter has

been always famous. Does not Sir Walter Scott tell us that the

laird of Culrossie fought a duel to defend its honour? Even

when worsted he still remarked, "I'll say yet, that better than

Aberdeen butter ne'er gaed down a Southern thrapple."

The fishing industry—now supplemented by trawling—has always

been active and profitable in Aberdeen. There are also large

paper and linen manufactories. The city has the largest comb

works in the kingdom—the industry doubtless originating in the

nearness of a great cattle-breeding country, has now grown to such

extent that cargoes of horns are shipped from the continent for its

uses. Granite from the neighbouring quarries—the very rock, as

it were, from which Aberdeen is herself hewn—has given her a share

not only in many of the world's public buildings, but in almost all

of earth's remotest "God's acres." Aberdeen granite may be

taken as a type of the best side of Aberdeen life, solid,

unpretentious, enduring, and capable of receiving a high polish.

Aberdeen stands between the Don and the Dee, and is in two

portions, Old Aberdeen and Aberdeen, once quite separate; even yet,

though almost merged in each other (and absolutely united for

municipal purposes), they retain many of their distinctive features.

Old Aberdeen is said to be simply a corruption of "Aulton," an

appellation often bestowed on places of similar position. The city

of Aberdeen makes its first clear appearance in Scottish history in

a still extant charter of William the Lion (1178), but that charter

confirms rights already granted by his grandfather David I. "Old

Aberdeen" has vague traditions of greater antiquity, but little can

be verified until the same David I. settled the seat of the diocese

there.

From remote antiquity a Christian place of worship is believed to

have occupied the same site as the present cathedral. That was begun

about 1357, and progressed slowly through succeeding centuries until

it was completed in 1518. It is dedicated to St. Machar, probably

the Scottish form of the name of Macarius, of Alexandria, who,

when a youth, left his fruit-stall in that city to join the famed

St. Antony. Macarius' special virtues were self-subjugation and

self-denial. He used to give himself the hardest and coarsest

necessary labours, pleading, "whenever I am slothful and idle, I am

pestered by desires for distant travel." Though he stayed thus at

home, his name travelled far, and this sturdy old edifice, amid its

fine trees and worn gravestones, has weathered the fury of civil war

and fanaticism, seems no bad emblem of the rugged and austere

hermit.

St. Machar's Cathedral was greatly increased and beautified by

Bishop Chiene. In those days its demesne was of considerable extent,

sloping down to the banks of the Don, and the houses of its

ecclesiastics filled the quarter known as "the Chanonry," in which

some quaint bits of antiquity may still be seen. Before the erection

of these "canons' houses," the bishops of Aberdeen had lived at what

is still called "The Bishops' Loch," a picturesque piece of water in

the midst of the wild moor of Scotston which skirts the sea coast,

to the north of the city.

During the long struggle of Wallace and Bruce to maintain the

independence of Scotland against the encroachments of Edward I. of

England, Aberdeen had its full share of disaster. It was more or

less "divided against itself." Bishop Chiene, with probably a

considerable following, supported the invaders against the natives,

and when fortune turned against him, fled to England.

"Bon Accord," the motto on the city arms, is said to have been the

Scots battle-cry on the occasion when Bruce defeated the English at Inverurie, while another part of his army drove the invaders out of

the citadel of Aberdeen. It is said that a little later Wallace

burned the English ships in Aberdeen harbour, and that it was to

"avenge" this that when the Scottish patriot was betrayed by his

own countrymen into the hands of the enemy and executed, one of his

dismembered limbs was sent to Aberdeen to be exposed there. But was

this so? The best authorities give Newcastle, Stirling, Berwick, and

St. Johnston, as the places which received the hero's mortal

remains. Yet certain chroniclers specify Aberdeen and Dumfries

instead of two of the towns. An old inhabitant of Aberdeen has been

heard to say that in his boyhood a stone bearing a curious mark used

to be pointed out in the wall of St. Machar's graveyard, as showing

the last resting-place of some of Wallace's remains. But considering

the devastation which befell Old Aberdeen more than two centuries

later on, it is hard to credit this. Indeed, the whole story of

Bruce and Wallace in Aberdeen is of so legendary a nature, so

contradictory in its details, and so wholly dependent on the

accounts of one Hector Boece (of whom we shall hear again), that it

is absolutely set aside by some of the best authorities.

The old "Brig o' Balgownie," whose single arch spans the Don where

its waters lie sparkling beneath wooded shelving banks, was erected

in this period. Yet its story, too, is somewhat uncertain. Rather,

it has two stories, not wholly incompatible. One is that it was

founded by Robert the Bruce as a favour to a district which had

been, in the main, loyal to him. The other avers that after the

Scots king was established on his throne, he recalled the runaway

Bishop Chiene and reinstated him, and that the Bishop in his

penitence devoted to the erection of this bridge the revenues which

had accumulated during his absence. It can be readily seen, as the

antiquarian Munro remarks, that "the truth probably lies in a

combination of both stories."

Popular interest in the old "Brig," is generally confined to the

antique rhyming "prophesy" which thus invokes the structure:

|

"Brig o' Balgownie, Wight (strong) is thy wa':

Wi' ae wife's ae son an' ae mear's ae foal,

Down thou sall fa'." |

Byron has spread the knowledge of this local "freit" far and wide,

by telling how the superstition terrorised his boyhood, because he

and his pony fulfilled the fated conditions. But the real history of

the "Brig" has its own suggestion towards a solution of the

problem of the "unearned increment." Nearly three hundred years ago

Sir Andrew Hay devoted to its future upkeep land of the annual worth