|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XVIII.

DECLINING YEARS OF BOULTON AND WATT—GREGORY WATT—DEATH OF BOULTON.

AT the

dissolution of the original partnership between Boulton and Watt, on

the expiry of the patent in 1800, Boulton was seventy-two years old,

and Watt sixty-four. The great work of their life had been

done, and the time was approaching when they must needs resign into

other hands the great branches of industry which they had created.

Watt, though the younger of the two, was the first to withdraw from

an active share in the concerns of Soho. He could scarcely be

said to taste the happiness of life until he had cast his business

altogether behind him.

It was far different with Boulton, to whom active occupation

had become a second nature. For several years, indeed, his

constitution had been showing signs of giving way, and nature

repeated her warning that it was time to retire. But in the

case of men such as Boulton, with whom business has become a habit

and necessity, as well as a pleasure and recreation, to retire is

often to die. He himself was accustomed to say that he must

either "rub or rust"; and as the latter was contrary to his nature,

he rubbed on to the end, continuing to take an active interest in

the working of the great manufactory which it had been the ambition

of his life to build up.

The department of business that most interested him in his

later years was the coinage. His chief pleasure consisted in

seeing his new and beautiful pieces following each other in quick

succession from the Soho Mint. Nor did he cease occupying

himself with new inventions; for we find him as late as 1797 taking

out a patent for raising water by impulse, somewhat after the manner

of Montgolier's Hydraulic Ram, to which he added many ingenious

improvements. His house at Soho continued to be the resort of

distinguished visitors; and his splendid hospitality never failed.

But, as years advanced and his infirmities increased, we find

him occasionally expressing a desire for quiet. He would then

retire to Cheltenham for the benefit of the waters, requesting his

young partners to keep him advised from time to time of the

proceedings at Soho. Even at Cheltenham, Boulton could not be

idle, but undertook a careful analysis of all the waters of the

place, the results of which he entered, in minute detail, in his

memorandum-book.

An alarming incident occurred at Soho towards the end of

1800, which is worthy of passing notice, as illustrative of

Boulton's vigour and courage even at this advanced period of his

life. A large gang of Birmingham housebreakers, knowing the

treasures accumulated in the silver-plate house, determined to break

into it and carry off the silver; together with the large sum of

money accumulated in the counting-house for the purpose of paying

the wages of the workmen, upwards of 600 in number, on Christmas

Eve. They had provided false keys for most of the doors, and

bribed the watchman, who communicated the plot to Boulton, to admit

them within the gates. He took his steps accordingly, arming a

number of men, and stationing them in different parts of the

building.

The robbers made the attempt on three several occasions.

On the first night they tried their keys on the counting-house door,

but failed to open it, on which they shut their dark lantern and

retired. Boulton sent an account of the proceedings each night

to his daughter in London. On the first attempt being made, he

wrote,—"The best news I can send you is that we are all alive; but I

have lost my voice and found a troublesome cough by the agreeable

employment of thief-watching."

Two nights after, the burglars came again, with altered keys,

but still they could not open the counting-house door. The

third night they determined to waive art, and break in by force.

They were allowed to break in and seize their booty, and were making

off with 150 guineas and a load of silver, when Boulton gave the

word to seize them. A quantity of tow soaked with turpentine

was instantly set fire to; numerous lights were turned on; and the

robbers found themselves surrounded on all sides by armed men.

Four of them were taken after a desperate struggle; but the fifth,

though severely wounded, contrived to escape over the tops of the

houses in Brook-row.

Writing to his friend Dumergue, in London, of the exploit,

Boulton said,—"You know I seldom do things by halves; so I have sent

the four desperate wolves to Stafford Gaol, and I believe the fifth

is much wounded. If I had made my attack with a less powerful

army than I did, we should probably have had a greater list of

killed and wounded." [p.413-1]

It was in allusion to this exploit that Sir Walter Scott said of

Boulton to Allan Cunningham, "I like Boulton; he is a brave man,—and

who can dislike the brave? [p.413-2]

The incident, when communicated to Scott during one of his visits to

Soho, is said to have suggested the scene in 'Guy Mannering,' in

which the attack is made on Dirk Hatterick in the smuggler's cave.

Occupation in business was not of the same importance to Watt

that it was to Boulton; and he was only too glad to get rid of it

and engage in those quiet pursuits in which he found the most

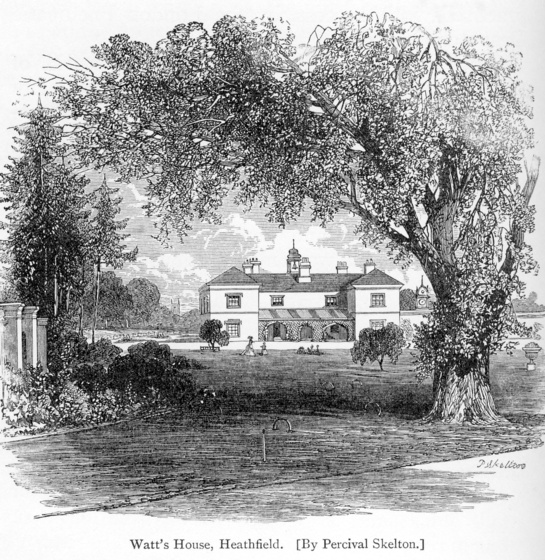

pleasure. In the year 1790 he removed from the house he had so

long occupied on Harper's Hill, to a new and comfortable house which

he had built for himself at Heathfield in the parish of Handsworth,

where he continued to live until the close of his life. The

land surrounding the place was, until then, common; and he continued

to purchase the lots as they were offered for sale, until, by the

year 1794, he had enclosed about forty acres. He took pleasure

in laying out the grounds, planting many of the trees with his own

hands; and in course of time, as the trees reached maturity, the

formerly barren heath became converted into a scene of great rural

beauty.

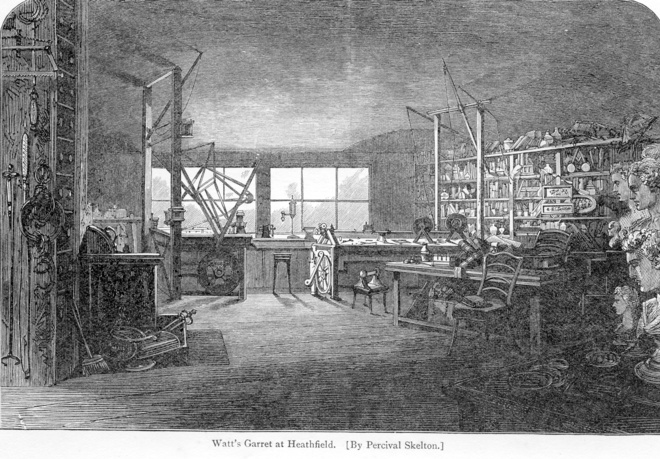

Annexed to the house, in the back yard, he built a forge, and

upstairs, in his "Garret," he fitted up a workshop, in which he

continued to pursue his mechanical studies and experiments for many

years. While Watt was settling himself for the remainder of

his life in the house at Heathfield, Boulton was erecting his large

new Mint at Soho, which was completed and ready for use in 1791.

When the lawsuits which had given Watt so much anxiety were

satisfactorily disposed of, an immense load was removed from his

mind; and he indulged in the anticipation of at last enjoying the

fruits of his labour in peace. Being of frugal habits, he had

already begun to save money, and accumulated as much as he desired.

But when the heavy arrears of Cornish dues were collected, about the

period of expiry of the patent, a considerable sum of money

necessarily fell to Watt's share; and then he began to occupy

himself in the pleasant recreation of looking out for an investment

in land. He was, however, hard to please, and made many

journeys before he succeeded in buying his estate.

Eventually Watt made several purchases of land at Doldowlod,

on the banks of the Wye, between Rhayader and Newbridge, in

Radnorshire. There was a pleasant farmhouse on the property,

in which he occasionally spent some pleasant months in summer amidst

beautiful scenery; but he had by this time grown too old to root

himself kindly in a new place; and his affections speedily drew him

back again to the neighbourhood of Soho, and to his comfortable home

at Heathfield.

During the short peace of Amiens in the following year, he

made the longest journey in his life. Accompanied by Mrs.

Watt, he travelled through Belgium, up the banks of the Rhine to

Frankfort, and home by Strasburg and Paris. While absent,

Boulton wrote him many pleasant letters, telling him of what was

going on at Soho. The brave old man was still at work there,

and wrote in as enthusiastic terms as ever of the coins and medals

he was striking at his Mint. Though strong in mind, he was,

however, growing feebler in body, and suffered much from attacks of

his old disease. "It is necessary for me," he wrote, "to pass

a great part of my time in or upon the bed; nevertheless, I go down

to the manufactory or the Mint once or twice a day, without injuring

myself as heretofore, but not without some fatigue. However,

as I am now taking bark twice a day, I find a daily increase of

strength, and flatter myself with the pleasure of taking a journey

to Paris in April or May next."

Upon Watt's arrival in London, a letter of hearty welcome

from Boulton met him; but it conveyed, at the same time, the sad

intelligence of the death of Mrs. Keir, a lady beloved by all who

knew her, and a frequent inmate at Soho and Heathfield. One by

one the members of the old circle were departing, leaving wide gaps,

which new friends could never fill up. The pleasant

associations which are the charm of old friendships were becoming

mingled with sadness and regret. The grave was closing over

one after another of the Soho group; and the survivors were

beginning to live for the most part upon the memories of the past.

But it is one of the penalties of old age to suffer a continuous

succession of such bereavements; and that state would be intolerable

but for the comparative deadening of the feelings which mercifully

accompanies the advance of years.

One of the deaths most lamented by Watt was that of Dr. Black

of Edinburgh, which occurred in 1799. Black had watched to the

last with tender interest the advancing reputation and prosperity of

his early protégé. They had kept up a continuous and

confidential correspondence on subjects of mutual interest for a

period of about thirty years. Watt, though reserved to others,

never feared unbosoming himself to his old friend, telling him of

the new schemes he had on foot and freely imparting to him his hopes

and fears, his failures and successes. When Watt visited

Scotland he usually took Edinburgh on his way, for the purpose of

spending a few days with Black and Robison. The latter went

express to London, for the purpose of giving evidence in the suit of

Watt against the Hornblowers, and his testimony proved of essential

service.

"Our friend Robison," Watt wrote to Black, "exerted himself

much; and, considering his situation, did wonders." When

Robison returned to Edinburgh, his Natural Philosophy class received

him with three cheers. He proceeded to give them a short

account of the trial, which he characterised as "not more the cause

of Watt versus Hornblower, than of science against ignorance."

"When I had finished," said he, "I got another plaudit, that Mrs.

Siddons would have envied." [p.417]

No one was more gratified at the issue of the trial than Dr.

Black, who, when Robison told him of it, was moved even to tears.

"It's very foolish," he said, "but I can't help it when I hear of

anything good to Jamie Watt." The Doctor had long been in

declining health, but was still able to work. He was busy

writing another large volume, and had engaged the engraver to come

to him for orders on the day after that on which he died. His

departure was singularly peaceful. His servant had delivered

to him a basin of milk, which was to serve for his dinner, and

retired from the room. In less than a minute he returned, and

found his master sitting where he had left him, but dead, with the

basin of milk unspilled in his hand. Without a struggle, the

spirit had fled. As the servant expressed it, "his poor master

had given over living." He had twice before said to his doctor

that "he had caught himself forgetting to breathe."

|

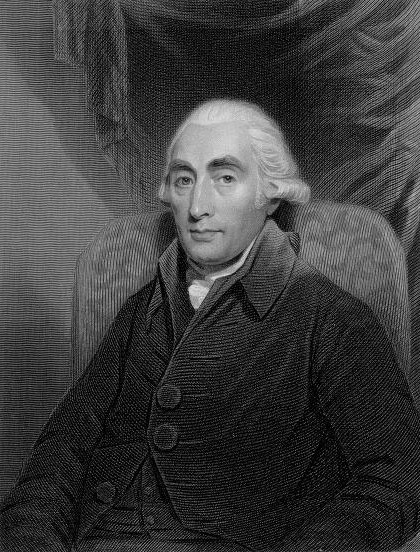

Ed.—Joseph Black (1728-99): Scottish

physician, physicist, and chemist: Professor of Anatomy

and Chemistry at Glasgow University and of Medicine at

Edinburgh University. Black is known for his discoveries

of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide.

Picture Wikipedia. |

On hearing of the good old man's death, Watt wrote to

Robison,—"I may say that to him I owe, in a great measure, what I

am; he taught me to reason and experiment in natural philosophy, and

was a true friend and philosopher, whose loss will always be

lamented while I live. We may all pray that our latter end may

be like his. He has truly gone to sleep in the arms of his

Creator, and been spared all the regrets attendant on a more

lingering exit. I could dwell longer on this subject; but

regrets are unavailing, and only tend to enfeeble our own minds, and

make them less able to bear the ills we cannot avoid. Let us

cherish the friends we have left, and do as much good as we can in

our day!"

Lord Cockburn, in his 'Memorials,' gives the following

graphic portrait of the father of modern chemistry:—

"Dr. Black was a striking and beautiful person; tall,

very thin, and cadaverously pale; his hair carefully powdered,

though there was little of it except what was collected into a long

thin queue; his eyes dark, clear, and large, like deep pools of pure

water. He wore black speck-less clothes, silk stockings,

silver buckles, and either a slim green silk umbrella, or a genteel

brown cane. His general frame and air was feeble and slender.

The wildest boy respected Black. No lad could be irreverent

towards a man so pale, so gentle, so elegant, and so illustrious.

So he glided, like a spirit, through rather mischievous sportiveness,

unharmed." [p.418]

Of the famous Lunar Society, Boulton and Watt now remained

almost the only surviving members. Day was killed by a fall

from his horse in 1789. Josiah Wedgwood closed his noble

career at Etruria in 1795, in the sixty-fifth year of his age.

Dr. Withering, distinguished alike in botany and medicine, died in

1799, of a lingering consumption. Dr. Darwin was seized by his

last attack of angina pectoris in 1802, and, being unable to bleed

himself, as he had done before, he called upon his daughter to apply

the lancet to his arm; but, before she could do so, he fell back in

his chair and expired. Dr. Priestley, driven into exile, [p.419]

closed his long and illustrious career at Northumberland in

Pennsylvania in 1803. The Lunar Society was thus all but

extinguished by death; the vacant seats remained unfilled; and the

meetings were no longer held.

But the bereavements which Watt naturally felt the most were

the deaths of his own children. He had two by his second wife,

a son and a daughter, both full of promise, who had nearly grown up

to adult age, when they died. Jessie was of a fragile

constitution from her childhood, but her health seemed to become

re-established as she grew in years. But before she had

entered womanhood, the symptoms of an old pulmonary affection made

their appearance, and she was carried off by consumption.

Mr. Watt was much distressed by the event, confessing that he

felt as if one of the strongest ties that bound him to life was

broken, and that the acquisition of riches availed him nothing when

unable to give them to those he loved. In a letter to a

friend, he thus touchingly alluded to one of the most sorrowful

associations connected with the deaths of children:—

"Mrs. Watt continues to be much affected whenever

anything recalls to her mind the amiable child we have parted with;

and these remembrances occur but too frequently,—her little works of

ingenuity, her books and other objects of study, serve as mementoes

of her who was always to the best of her power usefully employed

even to the last day of her life. With me, whom age has

rendered incapable of the passion of grief, the feeling is a deep

regret; and, did nature permit, my tears would flow as fast as her

mother's."

To divert and relieve his mind, as was his wont, he betook

himself to fresh studies and new inquiries. It is not

improbable that the disease of which his daughter had died, as well

as his own occasional sufferings from asthma, gave a direction to

his thoughts, which turned upon the inhalation of gas as a remedial

agent in pulmonary and other diseases. Dr. Beddoes of Bristol

had started the idea, which Watt now took up and prosecuted with his

usual zeal. He contrived an apparatus for extracting, washing,

and collecting gases, as well as for administering them by

inhalation. He professed that he had taken up the subject not

because he understood it, but because nobody else did, and that he

could not withhold anything which might the be of use in prompting

others to do better. The result of his investigations was

published at Bristol under the title of 'Considerations on the

Medicinal use of Fictitious Airs,' the first part of which was

written by Dr. Beddoes, and the second part by Watt.

But a still heavier blow to Watt was the death of his son

Gregory, a few years after the death of his only daughter.

Gregory Watt was a young man of the highest promise, and resembled

Watt himself in many respects—in mind, character, and temperament.

Those who knew him while a student at Glasgow College spoke of him

long after in terms of the most glowing enthusiasm. Among his

fellow-students were Francis, afterwards

Lord Jeffrey, and the poet

Campbell. Both were captivated not less by the brilliancy of

his talents than by the charming graces of his person.

Campbell spoke of him as "a splendid stripling—literally the most

beautiful youth I ever saw. When he was only twenty-two, an

eminent English artist—Howard, I think—made his head the model of a

picture of Adam." Campbell, Thomson, and Gregory Watt were

class-fellows in Greek, and avowed rivals; but the rivalry only

served to cement their friendship. In the session of 1793-4,

after a brilliant competition which excited unusual interest, the

Prize was awarded to Thomson; but, with the exception of the victor

himself, Gregory was the most delighted student in the class.

"He was," says the biographer of Campbell, "a generous, liberal, and

open-hearted youth; so attached to his friend, and so sensible of

his merit, that the honours conferred on Thomson obliterated all

recollections of personal failure." [p.421]

Francis Jeffrey was present at the commemoration of the first of

May, two years later, and was especially struck with the eloquence

of young Watt, "who obtained by far the greatest number of prizes,

and degraded the prize-readers most inhumanly by reading a short

composition of his own, a translation of the Chorus of the Medea,

with so much energy and grace, that the verses seemed to me better

perhaps than they were in reality. He is a young man of very

eminent capacity, and seems to have all the genius of his father,

with a great deal of animation and ardour which is all his own." [p.422]

Campbell thought him born to be a great orator, and

anticipated for him the greatest success in Parliament or at the

Bar. His father had, however, already destined him to follow

his own business. Indeed, Gregory was introduced as a partner

into the Soho concern, about the same time as his elder brother

James, and Matthew Robinson Boulton. But he never gave much

attention to the business. Scarcely had he left college,

before symptoms of pulmonary affection showed themselves; and, a

physician having been consulted, Mr. Watt was recommended to send

his son to reside in the south of England. He accordingly went

to Penzance for the benefit of its mild climate; and, by a curious

coincidence, he resided as boarder and lodger in the house of

Humphry Davy's mother. Davy was then a boy several years

younger than Gregory. He had already made some experiments in

chemistry, with sundry phials and kitchen utensils, assisted by an

old glyster apparatus presented to him by the surgeon of a French

vessel wrecked on the coast.

Although Gregory Watt possessed great warmth of heart there

was a degree of coldness in his manner to strangers, which repelled

any approach to familiarity. When his landlady's son,

therefore, began talking to him of metaphysics and poetry, he was

disposed to turn to him a deaf ear; but when Davy touched upon the

subject of chemistry, and made the rather daring boast for a boy,

that he would undertake to demolish the French theory in half an

hour, Gregory's curiosity was roused. The barrier of ice

between them was at once removed; and from thenceforward they became

attached friends. Young Davy was encouraged to prosecute his

experiments, which the other watched with daily increasing interest;

and in the course of the following year, Gregory communicated to Dr.

Beddoes, of Bristol, then engaged in establishing his Pneumatic

Institution, an account of Davy's experiments on light and heat, the

result of which was the appointment of the latter as superintendent

of the experiments at the Institution, and the subsequent direction

of his studies and investigations.

Gregory's health having been partially re-established by his

residence at Penzance, he shortly after returned to his father's

house at Birmingham, where Davy frequently visited him, and kept up

the flame of his ambition by intercourse with congenial minds.

Gregory heartily co-operated with his father in his investigations

on air, besides inquiring and experimenting on original subjects of

his own selection. Among these may be mentioned his inquiries

into the gradual refrigeration of basalt, his paper on which, read

before the Royal Society, would alone entitle him to a distinguished

rank among experimentalists. [p.423]

By the kindness of his elder brother James, Gregory Watt was

relieved of his share of the work at Soho, and was enabled to spend

much of his time in travelling about for the benefit of his health.

Early in 1801, we find him making excursions in the western counties

in company with Mr. Murdock, jun.; and looking forward with still

greater anticipations of pleasure to the tour which he subsequently

made through France, Germany, and Austria. We find him

afterwards writing his father from Freiburg, to the effect that he

was gradually growing stronger, and was free from pulmonary

affection. From Leipzig he sent an equally favourable account

of himself, and gave his father every hope that on his return he

would find him strong and sound.

These anticipations, however, proved delusive, for the canker

was already gnawing at poor Gregory's vitals. Returned home,

he busied himself with his books, his experiments, and his

speculations; assisting his father in recording observations on the

effects of nitrous oxide and other gases. But it was soon

found necessary to send him again to the south of England for the

benefit of a milder climate. In the beginning of 1804, his

father and mother went with him to Clifton, where he had an attack

of intermittent fever, which left him very weak. From thence

they removed to Bath, and remained there for about a month, the

invalid being carefully attended by Dr. Beddoes. During their

stay at Bath, Gregory's brother paid him a visit, and was struck by

his altered appearance. The fever had left him, but his cough

and difficulty of breathing were very distressing to witness.

As usual in such complaints, his mind was altogether unaffected.

"Indeed," wrote his brother, "he is as bright, clear, and vigorous,

upon every subject as I ever knew him to be. His voice, too,

is firm and good, and he enters into conversation I should lose the

recollection of his complaint if his appearance did not so forcibly

remind me of it. It is fortunate that he does not suffer much

bodily pain, nor, so far as I can discover, any mental anxiety as to

the issue of his complaint." [p.425-1]

When Gregory was sufficiently recovered from the debilitating

effects of his fever, he was moved to Sidmouth, where he appeared to

improve; but he himself believed the sea air to be injurious to him,

and insisted on being again removed inland. During all this

time his father's anxiety may be imagined; although he bore up with

as much equanimity as possible under circumstances so distressing.

"Ever since we left Bath," he wrote to Mr. Boulton at Soho, "ours

has been a state of anxiety very distressing to us, and the

communication of which would not have been pleasing to our friends.

To add to this, I have myself been exceedingly unwell, though I am

now much better. Gregory suffered very much from the journey,

which was augmented by his own impatience; and though he seemed to

recover a little from his fatigue during the first week, his breath

became daily worse, until we were obliged to remove him, on Thursday

last, to the neighbourhood of Exeter, where he is now with his

aunt." [p.425-2]

The invalid became rapidly worse, and survived his removal only a

few days. "This day," wrote the sorrowing father to Boulton, "the

remains of poor Gregory were deposited in a decent, though private

manner, in the north aisle of the cathedral here, near the transept.

. . . . I mean to erect a tablet to his memory on the adjoining

wall; but his virtues and merits will be best recorded in the

breasts of his friends As soon as we can settle our accounts, we

shall all return homewards, with heavy hearts." [p.426]

Davy was deeply affected by Gregory Watt's death; and in the

freshness of his grief he thus unbosomed himself to his friend

Clayfield:—

"Poor Watt! He ought not to have died. I

could not persuade myself that he would die; and until the very

moment when I was assured of his fate, I would not believe he was in

any danger. His letters to me, only three or four months ago,

were full of spirit, and spoke not of any infirmity of body, but of

an increased strength of mind. Why is this in the order of

nature,—that there is such a difference in the duration and

destruction of His works? If the mere stone decays it is to

produce a soil which is capable of nourishing the moss and the

lichen; when the moss and the lichen die and decompose, they produce

a mould which becomes the bed of life to grass, and to a more

exalted species of vegetables. Vegetables are the food of

animals,—the less perfect animals of the more perfect; but in man,

the faculties and intellect are perfected,—he rises, exists for a

little while in disease and misery, and then would seem to

disappear, without an end, and without producing any effect.

"We are deceived, my dear Clayfield, if we suppose that the

human being who has formed himself for action, but who has been

unable to act, is lost in the mass of being; there is some

arrangement of things which we can never comprehend, but in which

his faculties will be applied . . . . We know very little; but in my

opinion, we know enough to hope for the immortality, the individual

immortality of the better part of man. I have been led into

all this speculation, which you may well think wild, in reflecting

upon the fate of Gregory! My feeling has given wings to my

mind. He was a noble fellow, and would have been a great man.

Oh! there was no reason for his dying—he ought not to have died."

More deaths! A few years later, and Watt lost his

oldest friend, Professor Robison of Edinburgh, his companion and

fellow-worker at Glasgow College nearly fifty years before.

Since then, their friendship had remained unchanged, though their

respective pursuits kept them apart. Robison continued busily

and usefully occupied to the last. He had finished the editing

of his friend Black's lectures, and was occupied in writing his own

'Elements of Mechanical Philosophy,' when death came and kindly

released him from a lingering disorder which had long oppressed his

body, though it did not enervate his mind. A few years before

his death, he wrote to Watt, informing him that he had got an

addition to his family in a fine little boy,—a grandchild, healthy

and cheerful,—who promised to be a source of much amusement to him.

"I find this a great acquisition," said he, "notwithstanding a

serious thought sometimes stealing into my mind. I am

infinitely delighted with observing the growth of its little soul,

and particularly with the numberless instincts, which formerly

passed unheeded. I thank the French theorists for more

forcibly directing my attention to the finger of God, which I

discover in every awkward movement and every wayward whim.

They are all guardians of his life, and growth, and powers. I

regret that I have not time to make Infancy, and the development of

its powers, my sole study." [p.428-1]

In 1805 he was taken from his little playfellow, and from the

pursuit of his many ingenious speculations. [p.428-2]

Watt said of him, he was a man of the clearest head and the most

science, of anybody I have ever known, and his friendship to me

ended only with his life, after having continued for nearly half a

century. . . . His religion and piety, which made him patiently

submit without even a fretful or repining word during nineteen years

of unremitting pain,—his humility, in his modest opinion of

himself,—his kindness, in labouring with such industry for his

family, during all his affliction, his moderation for himself, while

indulging an unbounded generosity to all about him,—joined to his

talents, form a character so uncommon and so noble, as can with

difficulty be conceived by those who have not, like me, had the

contemplation of it during his lifetime."

Little more remains to be recorded of the business life of

Boulton and Watt. The former, notwithstanding his declining

health and the frequent return of his malady, continued to take an

active interest in the Soho coinage. Watt often expostulated

with him, but in vain, urging that it was time for him wholly to

retire from the anxieties of business. On Boulton bringing out

his Bank of England silver dollar, with which he was himself greatly

pleased, he sent some specimens to Watt, then staying at Clifton,

for his inspection. Watt replied,—"Your dollar is universally

admired by all to whom we have shown it, though your friends fear

much that your necessary attention to the operation of the coinage

may injure your health."

Mrs. Watt joined her entreaties to those of her husband,

expressing the wish that, for Mr. Boulton's sake, it might rain

every day, to prevent his fatiguing himself by walking to and from

the works, and there occupying himself with the turmoils of

business. Why should he not do as Mr. Watt had done, and give

up Soho altogether, leaving business and its anxieties to younger

and stronger men? But business, as we have already explained,

was Boulton's habit, and pleasure, and necessity. Moreover,

occupation of some sort served to divert his attention from the

ever-present pain within him and, so long as his limbs were able to

support him, he tottered down the hill to see what was going forward

at Soho.

As for Watt, we find that he had at last learnt the art of

taking things easy, and that he was trying to make life as agreeable

as possible in his old age. Thus at Cheltenham, from which

place Mrs. Watt addressed Boulton in the letter of advice above

referred to, we find the agèd pair making pleasant excursions into

the neighbourhood during the day, and reading novels and going to

the theatre occasionally in the evening. "As it is the

fashion," wrote Mrs. Watt,—"and wishing to be very fashionable

people, we subscribe to the library. Our first book was Mrs.

Opie's 'Mother and Daughter,' a tale so mournful as to make both Mr.

Watt and myself cry like schoolboys that had been whipped; . . . and

to dispel the gloom that poor Adeline hung over us we went to the

theatre last night to see the 'Honeymoon,' and were highly pleased."

Towards the end of 1807 Boulton had a serious attack of his

old disease, which fairly confined him to his bed; and his friends

feared lest it might prove his last illness. He was verging

upon his eightieth year, and his constitution, though originally

strong, was gradually succumbing to confinement and pain. He

nevertheless rallied once more, and was again able to make

occasional visits to the works as before. He had promised to

send a box of medals to the Queen, and went down to the Mint to see

them packed. The box duly reached Windsor Castle, and De Luc

acknowledged its reception: "As no words of mine," he said, "could

have conveyed your sentiments to Her Majesty so well as those

addressed to me in your name, I contented myself with putting the

letter into her hands. Her Majesty expressed her sensibility

for the sufferings you had undergone during the period of your

silence, and at your plentiful gift, for which she has charged me to

thank you; and as, at the same time that you have placed the whole

at her own disposal, you have mentioned the Princesses, Her Majesty

will make them partakers in the present."

De Luc concluded by urging Mr. Boulton to abstain from

further work and anxiety, and reminded him that after a life of such

activity as his had been, both body and mind required complete rest.

"Life," said he, "in this world is a state of trial,

and as long as God gives us strength we are not to shun even painful

employments which are duties. But in the decline of life, when

the strength fails, we ought to drop all thought of objects to which

we are no longer equal, in order to preserve the serenity and

liberty of mind with which we are to consider our exit from this

world to a better. May God prolong your life without pain for

the good you do constantly, is the sincere wish of your very

affectionate friends (father and daughter),

"DE LUC."

[p.431]

Boulton's life was, indeed, drawing to a close. He had

for many years been suffering from an agonising and incurable

disease—stone in the kidneys and bladder—and waited for death as for

a friend. The strong man was laid low; and the night had at

length come when he could work no more. The last letter which

he wrote was to his daughter, in March, 1809; but the characters are

so flickering and indistinct as to be scarcely legible. "If

you wish to see me living," he wrote, "pray come soon, for I am very

ill." Nevertheless, he suffered on for several months longer.

At last he was released from his pain, and peacefully expired on the

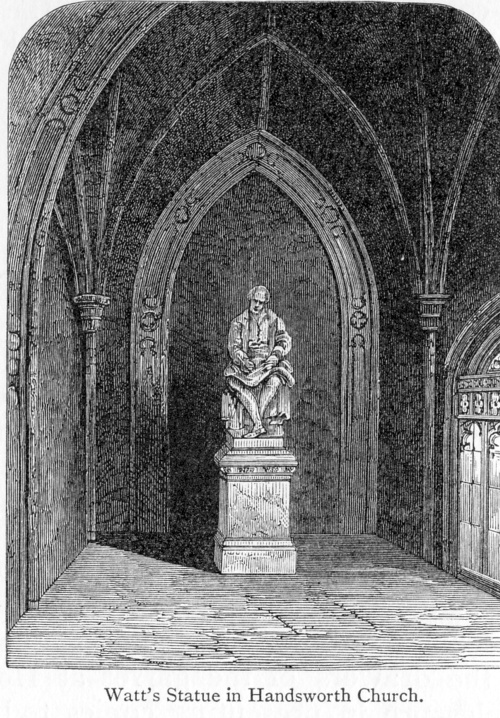

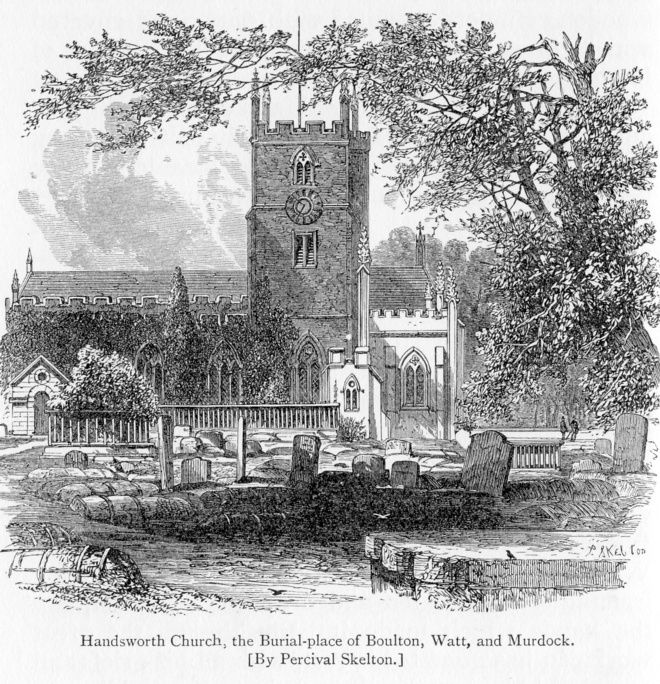

17th of August, 1809, at the age of eighty-one.

Though he fell like a shock of corn, in full season, his

death was lamented by a wide circle of relatives and friends.

A man of strong affections, with an almost insatiable appetite for

love and sympathy, he inspired others with similar feelings towards

himself; and when he died, they felt as if a brother had gone.

He was alike admired and beloved by his workmen; and when he was

carried to his last resting-place in Handsworth Church, six hundred

of them followed the hearse, and there was scarcely a dry eye among

them. [p.432]

[p.433]

Matthew Boulton was, indeed, a man of truly noble nature.

Watt, than whom none knew him better, was accustomed to speak of him

as "the princely Boulton." He was generous and high-souled, a

lover of truth, honour, and uprightness. His graces were

embodied in a manly and noble person. We are informed through

Dr. Guest, that on one occasion, when Mr. Boulton's name was

mentioned in his father's presence, he said, "he was the ablest man

I ever knew." On the remark being repeated to Dr. Edward

Johnson, a courtly man, he said, "As to his ability, other persons

can judge better than myself. But I can say that he was the

best-mannered man I ever knew." The appreciation of both was

alike just and characteristic, and has since been confirmed by Mrs.

Schimmelpenninek. She describes with admiration Boulton's

genial manner, his fine radiant countenance, and his superb

munificence: "He was in person tall, and of a noble appearance; his

temperament was sanguine, with that slight mixture of the phlegmatic

which gives calmness and dignity; his manners were eminently open

and cordial; he took the lead in conversation; and, with a social

heart, had a grandiose manner, like that arising from position,

wealth, and habitual command. He went about among his people

like a monarch bestowing largesse."

Boswell was equally struck by Boulton's personal qualities

when he visited Soho in 1776, shortly after the manufacture of

steam-engines had been begun there. "I shall never forget," he

says, "Mr. Boulton's expression to me when surveying the works.

'I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have, POWER.'

He had," continues Boswell, "about seven hundred people at work.

I contemplated him as an iron chieftain, and he seemed to be a

father of his tribe. One of the men came to him complaining

grievously of his landlord for having distrained his goods.

'Your landlord is in the right, Smith,' said Boulton; 'but I'll tell

you what—find a friend who will lay down one half of your rent, and

I'll lay down the other, and you shall have your goods again.'"

It would be a mistake to suppose that there was any

affectation in Boulton's manner, or that his dignified bearing in

society was anything but natural to him. He was frank,

cheerful, and affectionate, as his letters to his wife, his

children, and his friends, amply demonstrate. None knew better

than he how to win hearts, whether of workmen, mining adventurers,

or philosophers. "I have thought it but respectful," he wrote

to Watt from Cornwall, "to give our folks a dinner at a public-house

near Wheal Virgin to-day. There were present William Murdock,

Lawson, Pearson, Perkins, Malcolm, Robert Muir, all Scotchmen, and

John Bull, with self and Wilson,—for the engines are all now

finished, and the men have behaved well, and are attached to us."

At Soho he gave an entertainment on a much larger scale upon his son

coming of age in 1791, when seven hundred persons sat down to

dinner. Boswell's description of him as the father of his

tribe is peculiarly appropriate. No well-behaved workman was

ever turned adrift. On the contrary, fathers introduced their

sons into the factory, and brought them up under their own eye,

watching over their conduct and their mechanical training.

Thus generation after generation of workmen followed each other's

footsteps at Soho.

There was, no doubt, good business policy in this; for

Boulton knew that by attaching the workmen to him, and inspiring

them with pride in the concern, he was maintaining that prestige

which, before the days of machine tools, would not have been

possible without the aid of a staff of carefully-trained and

highly-skilled mechanics. Yet he had many scapegraces amongst

them—hard drinkers, pugilists, cock-fighters, and scamps. Watt

often got wholly out of patience with them, and urged their

dismissal, whatever might be the consequence. But though none

knew as well as Watt how to manage machines, none knew so ill how to

manage men. Boulton's practical wisdom usually came to the

rescue. He would tolerate any moral shortcoming save treachery

and dishonesty. He knew that most of the men had been brought

up in a bad school, often in no school at all. "Have pity on

them, bear with them, give them another trial," he would say; "our

work must not be brought to a standstill because perfect men are not

yet to be had." "True wisdom," he observed on another

occasion, "directs us, when we can, to turn even evils into good.

We must take men as we find them, and try to make the best of them."

Still further to increase the attachment of the workmen to

Soho, and keep together his school of skilled industry, as he called

it, Boulton instituted a Mutual Assurance Society in connexion with

the works; the first of the kind, so far as we are aware,

established by any large manufacturer for the benefit of his

workmen. Every person employed in the manufactory, in

whatsoever condition, was required to be a member. Boys

receiving 2s. 6d. a week paid a halfpenny weekly to

the box; those receiving 5s. paid a penny a week, and so on,

up to men receiving 20s. a week, who contributed 4d.;

payments being made to them out of the fund during sickness and

disablement, in proportion to their contributions during health.

The effects of the Society were most salutary; it cultivated habits

of providence and thoughtfulness amongst the men; bound them

together by ties of common interest; and it was only in the cases of

irreclaimable drunkards that any members of the Soho Friendly

Society ever came upon the parish.

But this was only a small item in the constitution of the

Soho manufactory. Before its establishment, comparatively

little attention had been given to the organisation of labour on a

large scale. Workshops were so small that everything went on

immediately under the master's eye, and workmen got accustomed to

ply at their work diligently, being well watched. But when

manufacturing was carried on upon so large a scale as at Soho, and

separate processes were conducted in different rooms and workshops,

it was impossible that the master's eye should be over all his

workers, or over even any considerable portion of them at the same

time.

It was therefore necessary to introduce a new system.

Hence the practice of inspection by deputy, and the appointment of

skilled and trustworthy foremen for the purpose of enforcing strict

discipline in the various shops, and at the same time economising

labour and ensuring excellence of workmanship. In carrying out

this arrangement, Boulton proved remarkably successful: and Soho

came to be regarded as a model establishment. Men came from

all parts to see and admire its organisation; and when Wedgwood

proceeded to erect his great pottery works at Etruria, he paid many

preliminary visits to Soho for the purpose of ascertaining how the

difficulties occasioned by the irregular habits of the workpeople

had been so successfully overcome by his friend; and of applying the

results of his experience in the organisation of his own

manufactory.

Though Boulton could not keep his eye directly on the

proceedings in the shops, he was quick to discern when anything was

going wrong. While sitting in the midst of his factory,

surrounded by the clang of hammers and the noise of engines, he

could usually detect when any stoppage occurred, or when the

machinery was going too fast or too slow, and issue his orders

accordingly. The sound of the tools going, and the hammers

clanging, which to strangers was merely an intolerable noise, was an

intelligible music to him; and, like the leader of an orchestra, who

casts his eye at once in the direction of the player of a wrong

note, so Boulton was at once conscious of the slightest dissonance

in the performances of his manufactory, and took the necessary steps

immediately to correct it.

From what we have already said, it will be sufficiently clear

that Boulton was a first-rate man of business. He had a hearty

enthusiasm for his calling, and took a just pride in it. In

conducting it, he was guided by fine tact, great knowledge of

character, and sound practical wisdom. When fully satisfied as

to the course he should pursue, he acted with remarkable vigour and

promptitude, bending his whole mind to the enterprise which he had

taken in hand. It was natural that he should admire in others

the qualities he himself desired to possess. "I can't say," he

wrote to Watt, "but that I admire John Wilkinson for his decisive,

clear, and distinct character, which is, I think, a first-rate one

of its kind." Like Wilkinson, Boulton was also distinguished

for his indomitable pluck; and in no respect was this more

strikingly displayed than in his prosecution of the steam-engine

enterprise.

Playfair has truly said, that had Watt searched all Europe

over, he could not have found another person so fitted to bring his

invention before the public in a manner worthy of its merits and

importance. Yet Boulton was by no means eager to engage in the

scheme. Watt could with difficulty persuade him to take it up;

and it was only in exchange for a bad debt that he at length became

a partner in it. But when once fairly committed, he threw

himself into the enterprise with an extraordinary degree of vigour.

He clearly recognised in the steam-engine a power destined to

revolutionise the industrial operations of the world. To M.

Argand, the famous French lamp inventor, he described it as "the

most certain, the most regular, the most durable, and the most

effective machine in Nature, so far as her powers have yet been

revealed to mortal knowledge"; and he declared to him that, finding

he could be of more use to manufactures and to mankind in general by

employing all his powers in the capacity of an engineer, than in

fabricating any kind of clincaillerie whatsoever, he would

thenceforward devote himself wholly to his new enterprise.

But it was no easy work he had undertaken. He had to

struggle against prejudices, opposition, detraction, and

difficulties of all kinds. Not the least difficulty he had to

strive against was the timidity and faintheartedness of his partner.

For years Watt was on the brink of despair. He kept imploring

Boulton to relieve him from his troubles; he wished to die and be at

rest; he "cursed his inventions"; indeed, he was the most miserable

of men. But Boulton never lost heart. He was hopeful,

courageous, and strong—he was Watt's very backbone. He felt

convinced that the invention must eventually succeed, and he never

for a moment lost faith in it. He braved and risked everything

to "carry the thing through." He mortgaged his lands to the

last farthing; borrowed from his personal friends; raised money by

annuities; obtained advances from bankers; and had invested upwards

of £40,000 in the enterprise before it began to pay.

During this terrible struggle he was more than once on the

brink of insolvency, but continued as before to cheer and encourage

his fainting partner. "Keep your mind and your heart pleasant

if possible," he wrote to Watt, "for the way to go through life

sweetly is not to regard rubs." To those about Watt he wrote,

"Do not disturb Mr. Watt, but keep him as free from anxiety as you

can." He himself took the main share of the burden,—pushing

the engine amongst the Cornish miners, bringing it under the notice

of London brewers and water companies, and finding money to meet the

heavy liabilities of the firm.

So much honest endeavour could not fail. And at last

the tide seemed to turn. The engine became recognised as a

grand working power, and there was almost a run upon Soho for

engines. Then pirates sprang up in all directions, and started

new schemes with the object of evading Watt's patent. And now

a new battle had to be fought against "the illiberal, sordid,

unjust, ungenerous, and inventionless misers, who prey upon the

vitals of the ingenious, and make haste to seize upon what their

laborious and often costly application has produced." [p.440]

At length this struggle, too, was conclusively settled in Boulton

and Watt's favour, and they were left at last to enjoy the fruits of

their labour in peace.

Watt never could have fought such a series of battles alone.

He would have been a thousand times crushed; and, but for Boulton's

unswerving courage and resolute determination, he could neither have

brought his engine into general use, nor derived any adequate reward

for his great invention. Though his specification lodged in

the Patent Office might clearly establish his extraordinary

mechanical genius, it is most probable that he himself would have

broken his heart over his scheme, and added another to the long list

of martyr inventors.

None was more ready to acknowledge the immense services of

Boulton in introducing the steam-engine to general use as a working

power, than Watt himself. In the MS. memoir of his

lately deceased friend deposited among the Soho papers, dated

Glasgow, 17th September, 1809, Watt says,—

"Through the whole of this business Mr. Boulton's

active and sanguine disposition served to counterbalance the

despondency and diffidence which were natural to me; and every

assistance which Soho or Birmingham could afford was procured.

Mr. Boulton's amiable and friendly character, together with his fame

as an engineer and active manufacturer, procured us many and very

active friends in both Houses of Parliament. . . . Suffice it to

say, that to his generous patronage, the active part he took in the

management of the business, his judicious advice, and his assistance

in contriving and arranging many of the applications of the

steam-engine to various machines, the public are indebted for great

part of the benefits they now derive from that machine.

Without him, or some similar partner (could such a one have been

found), the invention could never have been carried by me to the

length that it has been.

"Mr. Boulton was not only an ingenious mechanic, well skilled

in all the arts of the Birmingham manufacturers, but he possessed in

a high degree the faculty of rendering any new invention of his own

or of others useful to the public, by organising and arranging the

processes by which it could be carried on, as well as of promoting

the sale by his own exertions and those of his numerous friends and

correspondents. His conception of the nature of any invention

was quick, and he was not less quick in perceiving the uses to which

it might be applied, and the profits which might accrue from it.

When he took any scheme in hand, he was rapid in executing it, and

on those occasions spared neither trouble nor expense. He was

a liberal encourager of merit in others, and to him the country is

indebted for various improvements which have been brought forward

under his auspices. . . .

"In respect to myself, I can with great sincerity say that he

was a most affectionate and steady friend and patron, with whom,

during a close connexion of thirty-five years, I have never had any

serious difference.

"As to his improvements and erections at Soho—his turning a

barren heath into a delightful garden, and the population and riches

he has introduced into the parish of Handsworth, I must leave such

subjects to those whose pens are better adapted to the purpose, and

whose ideas are less benumbed with age than mine now are." [p.442]

We have spoken of Boulton's generosity, which was in keeping

with his whole character. At a time when he was himself

threatened with bankruptcy, we have seen him concerting a scheme

with his friend Wedgwood to enable Dr. Priestley to pursue his

chemical investigations free from pecuniary anxiety. To Watt

he was most liberal, voluntarily conceding to him at different times

profits derived from certain parts of the steam-engine business, far

beyond the proportions stipulated in the deed of partnership.

In the course of his correspondence we find numerous illustrations

of his generosity to partners as well as to workmen; making up the

losses they had sustained, and which at the time perhaps he could

ill afford. His conduct to Widow Swellengrebel illustrates

this fine feature in his character. She had lent money to

Fothergill, his partner in the hardware business, and the money was

never repaid. The consequence was, that the widow and her

family were seriously impoverished, and on their return to their

friends in Holland, Boulton, though under no obligation to do so,

remitted her an annuity of fifty pounds a year, which he continued

to the close of her life. "I must own," he wrote, "I am

impelled to act as I do from pity as well as from something in my

own disposition that I cannot resist." [p.443]

In fine, Matthew Boulton was a noble, manly man, and a true

leader of men. Lofty-minded, intelligent, energetic, and

liberal, he was one of those who constitute the life-blood of a

nation, and give force and dignity to the national character.

And working in conjunction with Watt, he was in no small degree

instrumental in introducing and establishing the great new working

power of steam, which has exercised so extraordinary an influence

upon all the operations of industry.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIX.

CLOSING YEARS OF JAMES WATT—HIS DEATH—CONCLUSION.

Medallion of Sir

Francis Legatt Chantrey's statue of Watt (reverse side)

By William Wyon, engraved by C. Chabot.

(The Life of James Watt, Muirhead, London, 1858.)

THE fragile and

sickly Watt outlived the most robust of his contemporaries. He

was residing at Glenarbach, near Dumbarton, with his relatives, when

the intelligence reached him of the death of his partner. To

Mr. Boulton's son and successor he wrote,—

"However we may lament our own loss, we must

consider, on the other side, the torturing pain he has so long

endured, and console ourselves with the remembrance of his virtues

and eminent qualifications. Few men have possessed his

abilities, and still fewer have exerted them as he has done; and if

to these we add his urbanity, his generosity, and his affection to

his friends, we shall make up a character rarely to be equalled.

Such was the friend we have lost, and of whose affection we have

reason to be proud, as you have to be the son of such a father."

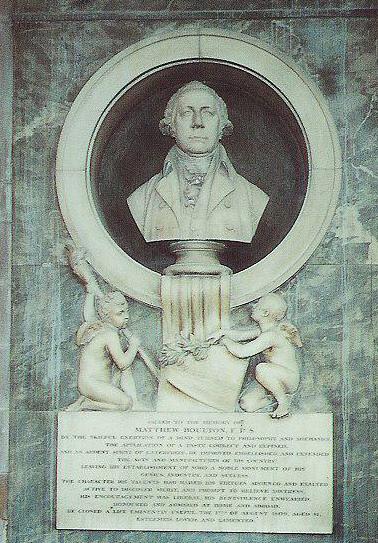

Bust of Matthew Boulton, St. Mary's Church,

Handsworth,

by John Flaxman (ca. 1809). [p.432]

Picture Wikipedia.

The deaths of his friends, one by one, reminded Watt of his

own mortality, and frequent references to the subject occur in his

letters about this time. He felt as if he were in danger of

being left in the world alone. But he did not give himself up

to melancholy, as he had been prone to do at the earlier periods of

his life. Shortly after his son Gregory died, he wrote to a

relative,—"I know that all men must die, and I submit to the decrees

of Nature, I hope with due reverence to the Disposer of events.

Yet one stimulus to exertion is taken away, and, somehow or other, I

have lost my relish for my usual occupations. Perhaps time may

remedy that in some measure; meanwhile I do not neglect the means of

amusement which are in my power."

Watt was at no loss for occupation to relieve the tedium of

old age. He possessed ample resources in himself, and found

pleasure alike in quiet meditation and in active work. His

thirst for knowledge was still unslaked, and he sought to allay it

by reading. His love of investigation was as keen as ever, and

he gratified it by proceeding with experiments on air, on light, and

on electricity. His inventive faculty was still potent, and he

occasionally varied his occupation by labouring to produce a new

machine or to improve an old one. At other times, when the

weather allowed, he would take a turn at planting in his grounds and

gardens; and occasionally vary his pleasure by a visit to Scotland,

to London, or to his estate in Wales.

Strange to say, his health improved with his advancing age,

and though occasionally dyspeptic, he was now comparatively free

from the racking headaches which had been the torment of his earlier

years. Unlike Boulton, who found pleasure in the active

pursuit of business, Watt, who had regarded it as a worry, was now

glad to have cast it altogether behind him. His mind was free

from harassing cares; his ambition in life was satisfied; he was no

more distressed by fears of Cornish pirates; and he was content

peacefully to enjoy the fruits of his invention. And thus it

was that Watt's later years may be pronounced to have been the

happiest of his life.

He had, indeed, lost nearly all his old friends, and thought

of them with a melancholy regret,—not, however, unmingled with

pleasure. But other young friends gathered about him, sat at

his feet, and looked up to him with an almost reverential

admiration. Among these we find Rennie and Telford the

engineers, Campbell the poet, Humphry Davy, Henry Brougham, Francis

Horner, and other rising men of the new generation. Lord

Brougham bears testimony to Watt's habitual cheerfulness, and to his

enjoyment of the pleasures of society during the later years of his

life. "I can speak on the point," he says, "with absolute

certainty, for my own acquaintance with him commenced after my

friend Gregory's decease. A few months after that event, he

calmly and with his wonted acuteness discussed with me the

composition of an epitaph to be inscribed on his son's tomb.

In the autumn and winter of 1805 he was a constant attendant at our

Friday Club, and in all our private circles, and was the life of

them all." [p.447]

To the close of his life, Watt continued to take great

pleasure in inventing. It had been the pursuit of his life,

and in old age it became his hobby. "Without a hobby-horse,"

said he, "what is life?" He proceeded to verify his old

experiments, and to live over again the history of his inventions.

When Mr. Kennedy of Manchester asked him, at one of his last visits

to Heathfield, if he had been able, since his retirement from

business, to discover anything new in the steam-engine, he replied,

"No; I am devoting the remainder of my life to perfect its details,

and to ascertain whether in any respect I have been wrong."

But he did not merely confine himself to verifying his old

inventions. He also contrived new ones. One of the

machines that occupied his leisure hours for many years was his

machine for copying statuary. We find him busy with it in

1810, and he was still working upon it in the year of his death,

nearly ten years later. The principle of the machine was to

make a cutting tool or drill travel over the work to be executed, in

like ratio with the motion of a guide-point placed upon the bust to

be copied. It worked, as it were, with two hands; the one

feeling the pattern, the other cutting the material into the

required form. The object could be copied either of the full

size, or reduced with the most perfect accuracy to any less size

that might be required. In preparing the necessary tools, Watt

had the able assistance of his friend Murdock, who was always ready

with his kindly suggestions and criticisms. In January, 1813,

Watt wrote to him,—"I have done a little figure of a boy lying down

and holding out one arm, very successfully; and another boy, about

six inches high, naked, and holding out both his hands, his legs

also being separate. But I have been principally employed in

making drawings for a complete machine, all in iron, which has been

a very serious job, as invention goes on very slowly with me now.

When you come home, I shall thank you for your criticisms and

assistance."

The material in which Watt executed his copies of statuary

were various,—marble, jet, alabaster, ivory, plaster of Paris, and

mahogany. Some of the specimens we have seen at Heathfield are

of exquisite accuracy and finish, and show that he must have brought

his copying-machine to a remarkable degree of perfection before he

died. There are numerous copies of medallions of his

friends,—of Dr. Black, De Luc, and Dr. Priestley; but the finest of

all is a reduced bust of himself, being an exact copy of Chantrey's

original plaster-cast. The head and neck are beautifully

finished, but there the work has stopped, for the upper part of the

chest is still in the rough. Another exquisite work, than

which Watt never executed a finer, is a medallion of Locke in ivory,

marked "January, 1812." There are numerous other busts,

statuettes, medallions,—some finished, others half-executed, and

apparently thrown aside, as if the workman had been dissatisfied

with his work, and waited, perhaps, until he had introduced some new

improvement in his machine.

Watt took out no patent for the invention, which he pursued,

as he said, merely as "a mental and bodily exercise." Neither

did he publish it, but went on working at it for several years

before his intentions to construct such a machine had become known.

When he had made considerable progress with it, he learned, to his

surprise, that a Mr. Hawkins, an ingenious person in the

neighbourhood, had been long occupied in the same pursuit. The

proposal was then made to him that the two inventors should combine

their talents and secure the invention by taking out a joint patent.

But Watt had already been too much worried by patents to venture on

taking out another at his advanced age. He preferred

prosecuting the invention at his leisure merely as an amusement; and

the project of taking out a patent for it was accordingly abandoned.

It may not be generally known that this ingenious invention of Watt

has since been revived, and applied, with sundry modifications, by

our cousins across the Atlantic, in fashioning wood and iron in

various forms; and powerful copying-machines are now in regular use

in the Government works at Enfield, where they are employed in

rapidly, accurately, and cheaply manufacturing gun-stocks!

|

|

Watt carried on the operations connected with this invention

for the most part in his Garret, a room immediately under the roof

at the kitchen end of the house at Heathfield, and approached by a

narrow staircase. It is a small room, low in the ceiling, and

lighted by a low broad window, looking into the shrubbery. The

ceiling, though low, inclines with the slope of the roof on three

sides of the room, and, being close to the slates, the place must

necessarily have been very hot in summer, and very cold in winter.

A stove was placed close to the door, for the purpose of warming the

apartment, as well as enabling the occupant to pursue his

experiments, being fitted with a sand-bath and other conveniences.

But the stove must have been insufficient for heating the garret in

very cold weather, and hence we find him occasionally informing his

correspondents that he could not proceed further with his machine

until the weather had become milder.

His foot-lathe was fixed close to the window, fitted with all

the appliances for turning in wood and metal fifty years ago; while

a case of drawers fitted into the recess on the left-hand side of

the room contained a large assortment of screws, punches, cutters,

taps, and dies. Here were neatly arranged and stowed away many

of the tools with which he worked in the early part of his life, one

of the drawers being devoted to his old "flute tools." In

other divisions were placed his compasses, dividers, scales, decimal

weights, quadrant glasses, and a large assortment of

instrument-making tools. A ladle for melting lead, and a

soldering-iron were hung ready for use near the stove.

Crucibles of metal and stone were ranged on the shelves along

the opposite side of the room, which also contained a large

assortment of bottles filled with chemicals, boxes of fossils and

minerals, jars, gallipots, blowpipes, retorts, and the various

articles used in chemical analysis. In one corner of the room

was a potter's lathe. A writing-desk was placed as close to

the window, for the sake of the light, as the turning-lathe would

allow; and in the corner was the letter-copying machine,

conveniently at hand.

In this garret Watt spent much of his time during the later

period of his life, only retiring from it when it was too hot in

summer, or too cold in winter, to enable him to continue his work.

For days together he would confine himself here, without even

descending to his meals. He had accordingly provided himself,

in addition to his various other tools, with sundry kitchen

utensils,—amongst others, with a frying-pan and Dutch oven—with

which he cooked his meals.

For it must be explained that Mrs. Watt was a thorough

martinet in household affairs, and, above all things, detested

"dirt." Mrs. Schimmelpenninck says she taught her two pug-dogs

never to cross the hall without first wiping their feet on the mat.

She hated the sight of her husband's leather apron and soiled hands

while he was engaged in his garret-work; so he kept himself out of

her sight at such times as much as possible. Some notion of

the rigidity of her rule may be inferred from the fact of her having

had a window made in the kitchen wall, through which she could watch

the servants, and observe how they were getting one with their work.

Her passion for cleanliness was carried to a pitch which

often fretted those about her by the restraints it imposed; but her

husband, like a wise man, gently submitted to her rule. He was

fond of a pinch of snuff, which Mrs. Watt detested, regarding it as

only so much "dirt"; and Mr. Muirhead says she would seize and lock

up the offending snuff-box whenever she could lay hands upon it.

He adds that at night, when she retired from the dining-room, if Mr.

Watt did not follow at the time fixed by her, a servant entered and

put out the lights, even when a friend was present; on which he

would slowly rise, and meekly say, "We must go."

One can easily understand how, under such circumstances, Watt

would enjoy the perfect liberty of his garret, where he was king;

and could enjoy his pinch of snuff in peace, and make as much "dirt"

with his turning-lathe, his crucibles, and his chemicals as he

chose, without dread of interruption.

One of the fears which haunted Watt as old age advanced upon

him was, that his mental faculties, in the exercise of which he took

so much pleasure, were deserting him. To Dr. Darwin he said,

many years before,—"Of all the evils of age, the loss of the few

mental faculties one possessed in youth is most grievous." To

test his memory, he again began the study of German, which he had

allowed himself to forget; and he speedily acquired such proficiency

as enabled him to read the language with comparative ease.

|

|

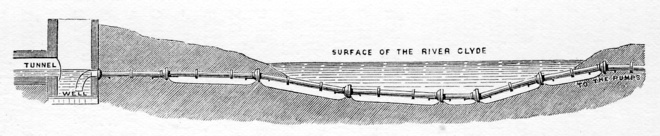

But he gave still stronger evidence of the integrity of his

powers. When in his seventy-fifth year he was consulted by the

Glasgow Waterworks Company as to the best mode of conveying water

from a peninsular across the Clyde to the Company's engines at

Dalmarnock,—a difficulty which appeared to them almost

insurmountable; for it was necessary to fit the pipes, through which

the water passed, to the uneven and shifting bed of the river.

Watt, on turning over the subject in his mind, shortly hit upon a

plan, which showed that his inventive powers were unimpaired by age.

Taking the tail of the lobster for his model, he devised a tube of

iron similarly articulated, of which he forwarded a drawing to the

Waterworks Company; and, acting upon his recommendation, they had

the tube forthwith made and laid down with complete success.

Watt declined to be paid for the essential service he had thus

rendered to the Waterworks Company; but the directors made a

handsome acknowledgment of it by presenting him with a piece of

plate of the value of a hundred guineas, accompanied by the cordial

expression of their thanks and esteem.

Watt did not, however, confine himself to mechanical

recreations at home. In summer-time he would proceed to

Cheltenham, the air of which agreed with him, and he would make a

short stay there; or he would visit his friends in London, Glasgow,

or Edinburgh. While in London, his great delight was in

looking in at the shop windows,—the best of all industrial

exhibitions,—for there he saw the progress of manufacture in all

articles in common use amongst the people. To a country

person, the sight of the streets and shop-windows of London alone,

with their display of objects of art and articles of utility, is

always worth a visit. To Watt it was more interesting than

passing through the finest gallery of pictures.

At Glasgow, where he stayed with his relatives the Macgregors,

he took pleasure in revisiting his old haunts; he dined with the

College Professors, [p.455]

and noted with lively interest the industrial progress of the place.

The growth of Glasgow in the course of his lifetime had, indeed,

been extraordinary, and it was in no small degree the result of his

own industrial labours. The steam-engine was everywhere at

work; factories had sprung up in all directions; the Broomielaw was

silent no longer; the Clyde was navigable from thence to the sea,

and its waters were plashed by the paddles of numerous steamers.

The old city of the tobacco lords had become a great centre of

manufacturing industry; it was rich, busy, and prosperous; and the

main source of its prosperity had been the steam-engine.

A long time had elapsed since Watt had first taken in hand

the repair of the little Newcomen engine in Glasgow College, and

afterwards laboured in the throes of his invention in his shop in

the back court in King Street. There were no skilled mechanics

in Glasgow then, and the death of the "old white-iron man" who

helped him had been one of his sorest vexations. Things were

entirely changed now. Glasgow had already become famous for

its engine-work, and its factories contained some of the most

skilled mechanics in the kingdom. Watt's original notion that

Scotchmen were incapable of becoming first-rate mechanics was

confuted by the experience of hundreds of workshops; and to none did

the practical contradiction of his theory give greater pleasure than

to himself. He delighted to visit the artisans at their work,

and to see with his own eyes the improvements that were going

forward; and when he heard of any new and ingenious arrangement of

engine-power, he would hasten to call upon the mechanic who had

contrived it, and make his acquaintance.

One of such calls, which Watt made during a visit to Glasgow,

in 1814, has been pleasantly related by Mr. Robert Hart, who, with

his brother, then carried on a small steam-engine factory in the

town.

"One forenoon," he says, "while we were at work, Miss

Macgregor and a tall elderly gentleman came into the shop.

She, without saying who he was, asked if we would show the gentleman

our small engine. It was not going at the time, and was

covered up. My brother uncovered it. The gentleman

examined it very minutely, and put a few pointed questions, asking

the reason for making her in that form. My brother, seeing he

understood the subject, said that she had been so made to try what

we thought was an improvement; and for this experiment we required

another cistern and air pump. He was beginning to show what

was properly Mr. Watt's engine, and what was not; when, at this

observation, Miss Macgregor stopped him, saying,—'Oh, he understands

it; this is Mr. Watt!'

"I never at any time saw my brother so much excited as he was

at that moment. He called on me to join them, saying,—'This

is Mr. Watt!' Up to this time I had continued to work at

what I was doing when they came; and, although I had heard all that

was said, I had not joined the party till I learned who he was.

Our supposed improvement was to save condensing water, and was on

the principle introduced by Sir John Leslie, to produce cold by

evaporation in a vacuum. Mr. Watt took much interest in this

experiment, and said he had tried the same thing on a larger scale,

but without the vacuum, as that invention of Professor Leslie's was

not known at the time. He tried it exposed to the air, and

also kept wet; and at one of the large porter-breweries in London he

had fitted up an apparatus of the same nature. The pipes

forming his condenser were laid in the water of the Thames, but he

could not keep them tight, from the expansion and contraction of the

metal, as they were exposed to various temperatures."

The conversation then diverged to the subject of his early

experiments with the Newcomen engine, the difficulties he had

encountered in finding a proper material for steam-pipes, the best

method of making steam-joints, and to various means of overcoming

obstacles which occur in the prosecution of mechanical experiments,

in the course of which he reverted to the many temporary expedients

which he had himself adopted in his early days.

Watt was so much pleased with the intelligence of the

brothers Hart, that he invited them to call upon him that evening at

Miss Macgregor's, where they found him alone with the ladies.

"In the course of conversation," continues Mr. Hart, "which embraced

all that was new at the time, the expansion and the slow contraction

of metals were touched on. This led to a discussion on iron in

engine-making," in which Watt explained the practice which

experience had led him to adopt as the best.

The conversation then turned upon the early scene of his

inventions, the room in the College, the shop in King Street, the

place on Glasgow Green near the Herd's house where the first idea of

a separate condenser flashed upon his mind, and the various steps by

which he had worked out his invention. He went on to speak of

his experience at Kinneil and Boroughstoness, of the Newcomen engine

he had erected and worked there for the purpose of gaining

experience, and incidentally referred to many of the other

interesting events in his past career. At a late hour the

brothers took their leave, delighted, as they well might be, with

the affability and conversableness, of "the great Mr. Watt."

But it was not in mechanics alone that Watt was so

fascinating in his conversation. He was equally at home

amongst philosophers, women, and children. When close upon his

eighty-second year, he formed one of a distinguished party assembled

in Edinburgh, at which Sir Walter Scott, Francis Jeffrey, and others

were present. He delighted the northern literati with his

kindly cheerfulness, not less than he astonished them by the extent

and profundity of his information.

"This potent commander of the elements," says

Scott,—"this abridger of time and space, this magician, whose

machinery has produced a change in the world, the effects of which,