|

|

|

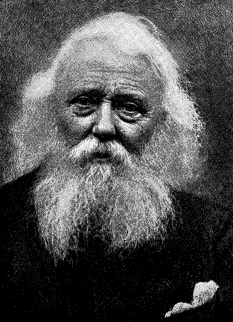

W. J. Linton

1812-1897 |

THERE is to-day an air of mild dilapidation about the picturesque farmhouse which was for so many years the scene of Mr. Linton's literary and artistic activities.

The low roofed, unassuming homestead, to which he paid a flying visit some thirty years

ago—at that time occupied by his friend, the distinguished American artist, Mr. W. J.

Hennessy—is not of the conventional New England type. The narrow front and side piazza, the friendly dormer windows, the diagonal lattice fence surmounting a rough stone wall and occasionally interlaced by creeping vines, the rising sweep of the mountain in the

rear—all give the gray, age-stained cottage an atmosphere of its own.

During his last days, however, Mr. Linton, from the south side of the porch, could hardly gain the view of the reposeful landscape that must have been one of the chief attractions of the early years, when he had ever before him the broad stretch of the Quinnipiac meadows and the blue North Haven hills. The old Boston turnpike was at that time the regular thoroughfare for the Cheshire farmers and the well loaded wagons of produce for which they found a ready market in the neighboring town; and the old Mount Carmel and Wallingford stage occasionally shambled by.

It was, indeed, not an inappropriate home for a man who, having already reached the age of well-earned leisure, had determined to devote his final years to poetry and art and to the recollections of a youth and manhood especially fruitful in friendships and noble endeavor.

Mr. Linton's life was to a great extent a process of disillusion; and not his least piquant disappointment must have been the degeneration of this same early landscape. Nearly everything has changed except the little brown domicile, whose primitive quaintness Mr. Linton himself zealously preserved. The view from the south porch has been shut off by a row of cheap citified houses, above which, incongruously enough, an occasional glimpse of the old familiar hills may still be obtained. Farther away the land has been transformed into a freight yard, and the jangling of the switching trains is hardly a fair compensation for the meadowy restfulness of a generation ago. In place of the stage coach and the hay wagons, the electric cars whiz by the house every hour of the day and night; and here and there an electric light steals all the glamour of the moon. The apple orchard too, we are afraid, has long ceased to render active service; an occasional shutter is absent from the blinds; and the regularity of the lattice fence is broken frequently by a

missing lath. Nevertheless the house still nestles behind East Rock, which forms as picturesque a background as in the early days; and the purple hills and the Sleeping Giant have lost none of their pristine splendor.

The fact that the city was gradually creeping abont his little New England home, that the old Boston road had been metamorphosed into a somewhat unkempt city thoroughfare, did not lessen the affection in which Mr. Linton regarded the place. It was

with difficulty that he could be persuaded to forsake his suburban habitat and move into the more comfortable if less congenial home

provided by his New Haven friends. He was engaged upon a final volume of poems, of which about seventy-five pages were printed at his death, and he was reluctant to leave his old printing-press before the completion of his work. In October, 1897, he was already too feeble to manage the large lever of his old hand press; but with the assistance of his grandsons he hoped to finish the volume before the end of his eighty-fifth year. This wish, however, was not realized. His printing outfit and his books were taken into the city with him; but his life-long interest in his work was never resumed. His last days at Appledore were made unhappy by other circumstances than his inability to fulfil his plans. Several months before his death

[at New Haven on the 29th of December 1897- Ed.] his trustworthy housekeeper died, and his endeavors to supply the

vacancy did not contribute to his peace of mind. Mrs. Moss was an English woman, whose acquaintance Mr. Linton had formed in London, and during her long term of service at Appledore the venerable engraver had become well nigh dependent upon her ministrations. It was of course impossible to find another housekeeper to take her place, and several candidates who had the temerity to undertake the experiment quickly gave up in despair. Up to the day of the abandonment of Appledore, however, Mr. Linton’s mind and hands were characteristically active.

His periodical trips to New York, to his friends at the Century Club, which for years had been the monthly diversions of his life, were not forgone; and while at home he still found recreation in his verses, his printing-press and his books. He perfectly realized, however, that his life had been lived, and he was reconciled to this by the fact that it had been unusually full and complete. He frequently remarked to his friends that his father and grandfather had died at eighty-five and that he did not himself desire to live beyond that time. He survived by not quite a month his eighty-fifth year.

The interior of the house is now as cheerless and forsaken as the surroundings are, for during the past few weeks all the unique furniture and paintings have been removed and the house itself has been exposed formally for sale. It is one of the things that

mark the end almost of an epoch in American arts and letters; for during

the past thirty years their foremost representatives have either been sheltered within the old homestead’s walls or have had immediate associations with it. It deserves an honored position in direct succession to the Boar’s Head Tavern, the Mermaid and Will’s Coffee

House. In Mr. Linton, Shakspere himself or Ben Jonson or Addison or Steele would have found much to love and enjoy. Only a few months ago, the small, low ceiled rooms of Appledore formed one of the most delightful and picturesque homes in the world. It represented, on Mr. Linton’s part, the work of thirty years; and to the collection of

paintings that almost concealed the walls and the books that crowded the shelves many of the foremost artists and poets of the century had made personal contributions. The north room, with its generous old New England fireplace and Yankee cupboards was the room to which Mr. Linton was especially devoted. Here he engraved and wrote and meditated in front of the old desk, his

“servant, companion and friend for more than half a century ;“ “the tombstone of my life” he was accustomed to call it. There was to his right an easel, upon which stood one of Edward Wehnert’s illustrations to Grimm’s Fairy Tales, above which was a photograph of the painter himself,

one of the friends of Mr. Linton’s youth. The portrait of another friend, William Bell Scott, and of his wife, painted

by the artist himself; a photograph of Penkill Castle; and, effectively reflecting Mr. Linton’s opinion of a celebrated nineteenth century statesman, a caricature of Louis Napoleon as a crippled tramp limping out of Sedan with the poor Prince Imperial on his back; a small painting of the Thames bank by Whistler,—these and many other similar mementoes furnished the key to Mr. Linton’s artistic and political temperament and interests. The walls were not adequate for many of the pictures, and the engravings of Mazzini and Herzen—of whom he writes so charmingly in his recollections — were obliged to find a resting place in front of a low chair. The seats of the chairs were usually covered with books, the overflow of the bursting shelves,—Selections from the Works of David Scott, the Works of Alfred Stevens, and his Biography, and Victor Hugo’s

Chatiments, presented to Mr. Linton by his Polish friend, Stanislas Worcell, and many more. The chimney-piece was covered with an array of plaster bric-a-brac, paintings, bronze medals and, especially noteworthy, a modelled dagger presented to Mazzini by the Italian Workingmen’s Association. Several of Mr. Linton’s friends are represented on or near this

chimney-piece—Mazzini, Garibaldi, Admiral de Rohan, who once paid a visit of several days to Appledore, Thomas Sibson, an artist of unfulfilled promise, and Mary Hallock Foote, one of Mr. Linton’s pupils. Mr. Linton’s sturdy republicanism, which was expressed on every hand, was especially noticeable in his favorite books—Milton, the Life and Death of Henry Vane,

Paroles d’un Croyant, a book that was a powerful “formative influence” in his younger days, Andrew Marvell, Lowell’s

Biglow Papers, and the Life of Captain John Brown. There were copies of Leigh Hunt’s poems, presented to Mr. Linton by the poet himself; Landor’s

Conversations and Last Fruit of an Old Tree, sent to Mr. Linton by the author; there were the

Early Italian Poets, the gift of Dante G. Rossetti; the Crown of Wild

Olive, sent to Appledore by John Ruskin; Walt Whitman’s Rivulet and

Leaves of Grass—the good gray poet was one of Mr. Linton’s closest

friends—London Lyrics from Frederick Locker; and Bewick and His Pupils and

Old World Idylls from Austin Dobson, the former dedicated to Mr. Linton as “Engraver and Poet, the steadfast apostle of Bewick’s White line”, with the following lines written on the fly-leaf by Mr. Dobson himself:

|

“Not white thy graver’s path alone;

May the sweet muse with whitest stone

Mark all thy days to come, and still

Delay thee on Parnassus Hill.” |

In this congenial room Mr. Linton lived a quiet life for nearly thirty years, with his books, his friends and his recollections. And what man of our own times has had more delightful companions or memories? He has written a charming book about the friendships he had made in seventy years and the important political and social movements in which he had taken part—a book whose one fault is

the too little information furnished of the author himself. Mr. Linton was a man of various gifts; but above all, even above that art of wood engraving of which he was one of the world’s greatest masters, was his supreme art of gaining and retaining friends. We have been informed since Mr. Linton’s death that his nature lacked greatness; but there surely must have been something great in the man who could gain the friendship and respect of so many great men. The position he held in the affection of such a man as Mazzini, for example, is sufficiently indicative of the largeness of his own nature. Mr. Linton’s association with the apostle of Italian unity was

the supreme enjoyment of his declining years; he fondly refers to it again and again in his

Recollections, and he wrote a large volume to commemorate that and other similar attachments. He loved to recall how in 1848—one of the most glorious dates in continental history in Mr. Linton’s view,—he had accompanied Mazzini to Paris for a visit to the

Abbé Lamennais, recently anathemized by the Pope and then editing in a small bare room in the Rue Jacob his daily paper,

Le Peuple Constituant; how he had been associated with the great Italian in the establishment of the People’s International League, whose aim, among other things, was to disseminate the principles of freedom and to interest the English public in the subject of Italian unity; how, after the meetings of this association, Mazzini would linger alone with him for a friendly talk over a glass of rum and water; and how, in the days which Mazzini spent with him at Woodford, while rambling through the Hainault forest he heard from Mazzini’s own lips the tragical story of the Bandieras, which he has reproduced in his

European Republicans.

Mr. Linton first became acquainted with Mazzini in 1837, when the fiery patriot, after a stormy and discouraging career in his own land, came to England with the hope of arousing English enthusiasm on his cherished project of Italian nationalism, and eked out a bare existence by opening a school for his countrymen in London—for the most part organ-grinders and hawkers of plaster casts. Here Mazzini and other Italian refugees delivered Sunday evening lectures; and here Mr. Linton one night met that sturdy New England transcendentalist, Margaret Fuller, who remained his friend. It was Mr. Linton’s correspondence, and that of other friends, which first brought Mazzini prominently before the English eye; their letters having been opened by Sir James Graham and the information of a threatened insurrection derived from them having been delivered by Lord Aberdeen to the Austrian ambassador, stirred up a loud protest throughout the kingdom and inspired, with a large amount of less important literature, Carlyle’s famous letter to the London Times. Mr. Linton made many friends through Mazzini—the Russian exile Herzen, George Sand, with whom he had a pleasant interview in Paris and whose works he was authorized to translate, the Polish patriot Stolzman, who spent two years with Mr. Linton

in the lake country, Albert Darasz, whose epitaph, in the handwriting of Kossuth, was one of the choicest mementoes of Appledore, and Stanislas Worcell, whose memory was immortalized by Kossuth in the same way. Mazzini’s friendship was the proudest

friendship of Mr. Linton’s life; he revered him above all other men and, unqualifiedly, believed that the nineteenth century had produced no man worthy of comparison with him. He was especially delighted to recall that he had for a single night commanded the English fleet for Garibaldi’s Sicilian expedition, planned by Mazzini, which expedition, however, subsequent events proved to have been unnecessary. He remained the close friend and correspondent of Mazzini up to the day of the patriot’s death in 1872.

Mr. Linton’s Recollections begin with the death of George III. in 1820, and extend to the publication of his

Masters of Wood Engraving in 1889. He could barely recall the tolling of the great bell in St. Paul’s cathedral and his father’s solemn face as he informed his eight-year-old son that “the old king was dead.” He remembered the funeral of Queen Caroline, as it passed his father’s door at Stratford—“the shabbiest notable funeral I ever saw,” he says. His father sympathized with this uncrowned and undivorced queen, and Mr. Linton too, in his old age, became her valiant champion. Another famous funeral he could recall was that of Nelson, at

which his father served in a military capacity. He read Scott’s Lady of the Lake and

Marmion in the original quarto editions, and he could recall the public curiosity over the authorship of the Waverley Novels, still the productions of the “Great Unknown.”

In 1828 he was apprenticed to Mr. George Wilmot Bonner, the wood engraver, a nephew and pupil of Branston, and spent six years in his family at Kennington. Here he became the friend of Thomas Wade, a poet of fine natural gifts, who has, however, obtained no permanent position in literature, and of Richard Hengist Home, a dramatist after the Elizabethan manner. During these early days he once breakfasted with Tennyson—and found him rather a dull fellow—at the house of Mary Howitt and her husband; he knew Thomas Cooper, the poet and shoemaker, author of the

Purgatory of Suicides, a long poem in Spenserian stanzas, written in prison; and he became known to Carlyle, whose signature he requested to a protest against capital punishment occasioned by the threatened execution of John Frost for political causes. Later he enjoyed an evening walk along the Strand with Carlyle, after a lecture by Emerson at Exeter Hall. At Leigh Hunt’s, Mr. Linton was a constant evening visitor; he became almost one of the family. Leech’s

earliest drawings were submitted to Mr. Linton, who at once perceived their remarkable merit; he succeeded Douglas Jerrold as editor of the

Illuminated Magazine; Mark Lemon, Thackeray, Tenniel, Cruikshank—all these and many others of the early

Punch crowd he knew well. He was the friend for over fifty years of William Bell Scott, of David Scott, his brother, and of Charles Wells, an early friend of Keats, whose story,

Claribel, Mr. Linton made liberal use of in his drama of the same name. Thornton Hunt, the wayward son of

the author of the Story of Rimini, Mr. Linton knew, but did not admire; and his experiences with George Henry Lewes were little more pleasing. One of the treasures of Appledore was a letter from Walter Savage Landor, accompanying his

Last Fruit of an Old Tree, and a manuscript poem, dedicated to Linton, beginning, “Praiser of Milton! worthy of his praise”—to be found in Landor’s collected works. In 1855 Mr. Linton also received the

Imaginary Conversations, with this inscription: “W. S. Landor to W. J. Linton, a true patriot and a true poet,—characters almost equally rare.”

Landor also contributed to Mr. Linton’s English

Republic, and was an occasional correspondent. Mr. Linton, however, never saw the venerable poet. After Landor’s indictment on a charge of libel and his consequent

abandonment of England for Italy, he left in Mr. Linton’s care a number of pamphlets in justification of his course, requesting their distribution—a request which Mr. Linton charitably ignored. Landor later sent his friend a painting, “The First Judgment,” which he believed to be by Michael Angelo. The painting was sent through Robert Browning and was the means of

introducing Mr. Linton to that poet. Other poets with whom Mr. Linton was on familiar terms, whose names occur again and again in his

Recollections, were Dante Rossetti,at whose house in Chatham Square he met a boyish looking young man who has since become famous as the author of

Atalanta in Calydon; Dinah Muloch, “a somewhat spindly woman;“ Martin Farquhar Tupper, the proverbial philosopher; Robert Montgomery, William Morris, whom he frequently recalled in the wanderings of his last sickness and the Americans, Bryant, Lowell,

Longfellow, Whittier, Emerson, Whitman, Mrs. Howe, Stedman, Stoddard and Bret Harte. The artists whom he numbered among his friends or acquaintances were, besides the contributors to

Punch, Millais, Whistler, Madox Brown, George and James Foggo, Alfred Stevens, the designer of the Duke of Wellington’s statue in St. Paul’s Cathedral,— “my very dear friend,” he calls him,—and William Page, president of the National Academy of Design. Mr. Linton’s versatility in friendship ranged all the way from the Hon. Benjamin F. Butler to Charles Sumner, from Charlotte Cushman to Harriet Martinean, and from Wendell Phillips to George Francis Train.

Associated with men and women of this stamp through his full rounded life, Mr. Linton was himself one of the hardest and most

successful workers in the fields of art, literature and politics. His life naturally divides itself into two periods;—his career in England between the years 1812 and 1867, years of political storm and stress, into whose battles Mr. Linton plunged with all the vehemence of the born reformer; and the more subdued but by no means inactive days at Appledore in New Haven. During all these years he was almost equally conspicuous as an engraver, a poet and a politician; and there are no lines of demarkation between his several vocations. These three phases were comprised in a vigorous, conscientious and indomitable nature, keenly alive to the responsibilities of life and to the necessity of recognizing a lofty ideal. Like Milton, his favorite author, Linton thought it more important to be a great citizen than a great poet; and his pencil and his pen were always dedicated to the uplifting of his countrymen. His political hatreds were always emphatic and sometimes extreme. He never refers to Thiers, and especially to his part in the Paris Commune, except

with loathing; the “historic liar” he calls him in one place. From his earliest days Mr. Linton had a fondness for the exile, for the persecuted patriot; and the small band that gathered about Mazzini comprehended, to his eye, the highest type of citizenship. His attitude upon political and religious questions was radical. He suggests that he may have inherited this tendency from his father, who was accustomed to break away from tradition, but who was not sufficiently aggressive to influence actively the young man. He was educated in the doctrines of the Church of England, and was early impressed by his mother with the worthiness of the surely not

irreproachable royalty of that day. At an early date Mr. Linton began to read Voltaire; and Shelley’s

Queen Mab and Lamennais’ Paroles d’un Croyant early stirred in him, he says, “the passion of reform.” Shortly after he had passed his twentieth year, he found

himself eagerly battling for a better and more righteous social system than that of which he found himself an unwilling member.

The republican sentiment is not notably manifest in England to-day; but the period of Mr. Linton’s youth and manhood was fruitful in demonstrations of its strength. He was twenty years of age at the time of the passage of Earl Grey’s Reform Bill—a measure as inadequate to Mr. Linton’s demands as to those of many of his countrymen. They were the days of the People’s Charter, of the uncompromising radicalism of John Arthur Roebuck, of the seditious thunderings of Feargus O’Connor, of the vehement eloquence of O’Connell, of governmental intolerance and persecution. The statesmen of that day found it impossible to restrain the ceaseless outpourings of prescribed books and pamphlets, and the repeated incarceration of their authors in no way quelled their enthusiasm. Many of Mr. Linton’s friends became the victims of a tyrannical press censorship, though he himself for some reason escaped,— honest James Watson, who devoted his energies to the publication and circulation of forbidden volumes, Henry Hetherington, whose

Poor Man’s Guardian, professedly published “contrary to law,” frequently brought himself and many of his friends into gaol. The supreme demand of these men, for universal suffrage, crystallized in the famous People’s Charter movement, into which Mr. Linton plunged with characteristic zeal. He was, however, one of the milder chartists (not one of the Feargus O’Connor brand), who believed in accomplishing their purposes by petition and peaceable agitation. His connection with such an association, however, deprived him of many influential friends and increased the hardship of his life. He supplemented his wood engraving by contributions to several political organs, became the editor of the

Odd Fellow, and started in 1835 an unsuccessful venture called the

Library for the People. The People’s International League, with which Mr. Linton became identified, contained on its council board such men as Doctor Bowring, M. P., Thomas Cooper, W. J. Fox, Thornton Hunt and Douglas Jerrold. The association, of which Mr. Linton became the honorary secretary, obtained considerable vogue on the continent, its address was translated into the various European languages, and its organization was publicly celebrated in several towns in Switzerland. These labors Linton supplemented by lectures in London,

notably upon the condition of Italy. In 1848, in company with J. D. Collett and Mazzini, he carried the address of the English workingmen to the provisional government at Paris, and was present during the days of the barricades. In 1849 he founded, in association with George Henry Lewes and Thornton Hunt, a weekly paper, the

Leader, which was to be the great organ of the republican party in England. Thornton Hunt became the chief editor of this enterprise, Lewes the literary editor, while Mr. Linton himself took charge of the foreign department. It did not take Mr. Linton long to discover, however, that his two associates lacked real enthusiasm for the republican cause, and he soon withdrew in disgust.

He was now free to undertake the most important journalistic work of his life, the editing and publication of the

English Republic. Mr. Linton started this famous series of papers in

1850, in Leeds, where they were issued in weekly form. He continued for two years on this plan, but in 1852 took a large stuccoed

house in the Lake country, which he named Brantwood, and which is now the residence of John Ruskin. The years which Mr. Linton spent beside Coniston Lake, dividing his time between a few

faithful friends, his engravings and his writing, and an occasional ramble over the hills, perhaps for a brief call at Ambleside, the home of Harriet Martineau, with whom Mr. Linton became very neighborly, were in many ways the most delightful of his life. It was here that his most vigorous prose writings, the

English Republic, were issued to a small and unappreciative audience. Mr. Linton established his own printing press at Brantwood—in this respect a forerunner of Appledore—and secured the services of three interesting young men in the work. The aim of the

English Republic was no less ambitious than the establishment of a republican party in England—an ambition hardly realized. Only a few hundred copies were issued each month, many of which were distributed free; and the venture, like most of Mr. Linton’s literary enterprises, was run on a losing basis. The writing in the

English Republic, however, is by no means to be despised. Its style is vigorous and pointed and it is readable even at this day. It was of sufficient interest in 1891 to warrant a reprint, edited with an introduction and notes by Kineton Parkes. Mr. Linton’s republicanism, as illustrated in this volume, is of a rather socialistic order. One of the early essays is especially interesting as a forecast of the single-tax idea of Mr. Henry George. He defined

monarchy as class government, and republicanism as the rule of the majority. In his ideal state, none were to be uneducated, none were to be without property, and none were to be shut out from the “people’s land.” He did not advocate representative government, but a government in which the people should themselves enact the laws—a squint toward the referendum. His

Republic was not so insular as the title of the publication would imply; he was not interested merely in the nation, the family or the parish, but looked forward to the federation of the world. He believed in a social state, capable of immediate realization, in which there should be no poverty, no wickedness, no ignorance and no injustice.

Whether Mr. Linton retained this optimistic philosophy in his latter days is not known; it is known, however, that he never abandoned his sturdy republican faith. This political apostleship ended in 1867, when he made his permanent home in America. He was still attracted to those men, however, who like himself had devoted their finest energies to their fellow men; and it was this trait

in Whittier that inspired his admiration and led him to write his life. His keen interest in American affairs is illustrated in his Hudibrastic satire, the

Adventures of Ulysses (that is, Ulysses S. Grant) and an amusing skit published during the Tweed imbroglio,

The House that Tweed Built. It is an interesting fact that the famous boss offered Mr. Linton one thousand dollars for the suppression of this little pamphlet.

In Mr. Linton’s poetry, especially that of the earlier days, this same indomitable republicanism is manifest. Linton believed that poetry, like every other form of human endeavor, should be subservient to life itself and could never speak too severely of the “art

for art’s sake” enthusiast. Mere jugglers with words, aiming to set forth no ideal of life, found harsh consideration at his hands. The one poet whom he especially abhorred on these grounds was Edgar Allan Poe, whom he ridiculed in several rather clever parodies—ghoul poems, he called them — collected and published in 1876 under the significant title,

Pot Pourri. Mr. Linton admired Poe’s marvelous technical skill, but to his mind, the author of the

Bells and Israfel was not a poet, but merely one of the curiosities of literature. His attitude towards Poe, together with his admiration for Milton and Shelley, give the key to his own poetic aspiration. The art-for-art’s-sake advocates, however, might make a telling point against Mr. Linton in his own career. His republican rhapsodies and his rythmical complaints against the landlord system in Ireland are as dead now as the “Corn-law Rhymes” of Ebenezer Elliott, and his poetical reputation rests almost entirely upon a hundred or so delightful little lyrics,

Love Lore, the productions of his old age. Like Whittier, however, in his earlier years, he used his poetic gift merely as a prop to his political and social theories. A large amount of this early verse is now inaccessible, Mr. Linton not caring to preserve it in the later editions of his works. His penchant for literary

oddities was early disclosed in a Butlerian satire, Bob Thin, The Poor House

Fugitive, published in 1845 — a criticism of the new poor law. This production was never regularly published and is now one of the rarest eccentricities of literature. Along the same line, but of greater literary merit, was his satire, directed against the commercial instinct of the English people,

The Jubilee of Trade, a Vision of the Nineteenth Century After

Christ—a palpable imitation of Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy. He had not yet outgrown Shelley’s influence when he published, in 1848,

The Dirge of the Nations, and To the Future. The tone of these poems was still didactic, but was pitched upon a somewhat higher key. He was inspired by the continental convulsions of that year, and his poems were intended as a rebuke

to his own land,

“The land of Alfred,”

he sings in splendid resonant lines,

|

“who without surcease

Toil’d for the Future’s peace;

The land of Wiclif, hearsed by God’s own

sea

Into eternity;

The land where Eliot dared a prison

doom;

The land of Vane and Hampden, not their

tomb,

But the high altar of their sacrifice;

The land of Milton, whose prophetic eyes

Beyond the shadow of the passing time

Gazed on the future’s face with calm sub-

lime;

The land of crownčd Cromwell,” |

the land, however—and this was the burden of Mr. Linton’s complaint—which remained impassive, except for a few Chartist meetings and an ill-organized mob in Kennington Common, in face of all those glorious revolutionary enterprises. Mr. Linton’s impassioned strains had little effect upon the political fortunes of his country, but they were not without their effect upon its literature. According to Mr. H. Buxton Forman, Mrs. Browning’s

Casa Guidi Widows could not have been written had it not been for Mr. Linton’s

Dirge of the Nations; and the same critic believes that he traces its influence in Swinburne’s

Eve of the Revolution, in the Songs Before Sunrise.

The Plaint of Freedom, written in the In Memoriam stanza, and the “Landlordism” series published in Sir Charles Gavan Duffy’s Irish

Nation, complete the catalogue of Mr. Linton’s early poetical attempts. They were apparently merely of ephemeral

interest, for they have been out of print many years. A few choruses and songs Mr. Linton preserved in his

Claribel and Other Poems, published in 1865 (a delightfully printed and delightfully illustrated little volume), but for the most part he was content with their obscurity.

Of Love Lore, published in 1885, there is a different story to tell. His poetical experience resembles that of Ben Jonson, in that he devoted the years of his prime to philosophical and political essays in verse, undiscouraged by the world’s neglect, and only in his declining years made evident his genuinely poetic talent. That Ben Jonson should have written his “Drink to me only with thine

eyes” under the crushing circumstances of poverty, old age and disease, and the

Sad Shepherd upon his deathbed is no less surprising than that Mr. Linton should have written his

Love Lore after he had reached his seventieth year. It was not until then that he abandoned his politics and social philosophy and devoted himself to the traditional poetic themes of flowers and love and wine. It may seem improbable that an old white-haired man could have any genuine sympathy with his own songs; but Mr. Linton’s verses are far from wooden. There is, indeed, no deep emotion, no bewildering passion, in his love songs; he always approaches the theme from the outside, as an interested and frequently cynical observer. In the hundred or so lyrics comprising the volume, he is a cavalier to the core; we can find Suckling and Lovelace and Herrick and Carew upon nearly every page. He was a constant reader and admirer of the

Elizabethan and Jacobean lyrists; and his affectation of their manner, not only in the cast of thought but frequently in the phraseology itself, is by no means displeasing. Mr. Linton was so fond of literary hoaxes—one of the first publications of the Appledore press was a little book called

Windfalls, comprising two hundred passages from imaginary plays—that it is surprising that he did not issue his

Love-Lore as the work of a forgotten seventeenth century poet. It would have

been difficult to have detected the fraud. The little volume was not only written, but printed, by Mr. Linton himself; for he had long since established an old Hoe hand-press at New Haven, from which he issued those exquisite little publications that are to-day so prized by bibliophiles. One of the rarest,

Golden Apples of Hesperus, an English anthology extending from William Dunbar to Rossetti, was edited, drawn, engraved composed and printed by Mr. Linton himself. Though he had not been bred to the printer’s trade, his

Golden Apples is regarded as a masterpiece of the craft, and “might challenge comparison,” says Mr. A. H. Bullen, “with the productions of the Chiswick

press.

Mr. Linton, however, did even finer work at the Appledore press than his

Golden Apples of Hesperus. Whatever may become of his fame as a poet and a political writer, his position among the world’s greatest engravers is secure. In the history of wood engraving, which has now well nigh become a lost art, it is safe to say that Mr. Linton’s will be the one pre-eminent name. The rise and decadence of the art is a brief though not an inglorious story, and is almost coincident with Mr. Linton’s own life. He dates the real beginning of wood engraving with Thomas Bewick, who died in the very year of his own apprenticeship, 1828. It was Linton, too, who was destined to carry the work of Bewick to its fullest completion. “However unsuccessful,” he says, “I may yet claim the distinction of ordering the whole toward the revival of ‘white line’ the intelligent graver work of the Bewick school.” His admiration for Bewick’s artistic

skill, however, is not conventionally extravagant; and one of the real services which his

Masters has contributed has been a more critical comprehension of the merits and defects of his much-misunderstood predecessor. From Bewick’s “white line,” however,

Mr. Linton traces the beginning of his art; and he witnessed to its excellence both with his pen and—even more vividly—his own performances. There are hundreds of engravings, scattered through almost as many English and American publications, in which Mr. Linton demonstrated what might be done by the proper application of Bewick’s “white line,” and there are several doughty volumes in which he combated, in his own vigorous way, a decadent age that inclined toward a different style. His most famous polemic on this theme was his essay in the

Atlantic Monthly for June, 1879, in which he criticised the prevailing modes with a candor that set the whole artistic world by the ears, and which he followed up with his

Practical Hints on Wood Engraving, a small volume which completely silenced the reviewers.

Mr. Linton came to America at an opportune hour; for the condition of his art in this country required the stimulating influence of a master like himself. A few engravers were rather unintelligently groping their way, and these immediately profited by Mr. Linton’s kind instruction. They had long revered him as the former partner of John Orrin Smith, as the man

whose work on the Illustrated London News, started in 1842, had materially contributed to the phenomenal success of that journal, and as the artist, as well as the engraver, of the dainty illustrations to Harriet Martineau’s

English Lakes (1858). His engravings of the Infant Hercules and the Haunted House had long been the inspiration of every American worker in wood. He was therefore given a cordial reception when he arrived, in 1867, to take charge of the art department of

Frank Leslie’s Weekly; and the school which he soon opened in Cooper Institute had a powerful influence upon the art in America. His position was further strengthened by his engravings to Doctor Holland’s

Katrina, from drawings by W. J. Hennessy, and by the series, in conjunction with the same artist, of Edwin Booth in twelve dramatic characters. He also furnished the drawings and engravings for an edition of Bryant’s

Thanatopsis and The Flood of Years. He soon established his home at New Haven, where he set up the printing press from which his noblest effort,

The Masters of Wood Engraving, was issued in 1889.

This is a work that must endure. It is a book, in fact, that can never be superseded; for it is almost impossible that there shall be another who will combine Mr. Linton’s

marvellous technical skill and comprehensive knowledge of the subject. Few young

men are taking up wood engraving now, for the simple reason that the growth of the new and cheaper processes is making it more and more difficult to gain a livelihood at the art. Mr. Linton had himself done little engraving during the last fifteen years of his life. It is therefore safe to assume that the

Masters of Wood Engraving is a final work—a position which its own excellence accorded it the very

day of its publication. Mr. Linton had early decided to undertake a volume of this scope, but he did not determine upon so elaborate a work until his investigations in the British Museum convinced him that it was practically a new field. In 1883 and 1884 he renewed his researches in the print room of the Museum; took by the permission of the trustees some two hundred photographs and returned to Appledore, well prepared with notes, to write his book. He was so fastidious about his masterpiece, that he determined to mount all his photographs and to print the volume himself. After two years’ hard work, he had prepared three copies in precisely the form he

desired. They were magnificent examples not only of the engraver’s but of the printer’s art. In 1889 six hundred copies of this book, in facsimile, were issued by a London publishing house. In the preface he says that his aim is not to write as a bibliographer, but as an engraver,—to give the history of engraving “through the exhibition of its masterpieces.” The book therefore, aside from its literary and historical value, forms an art gallery of English and American engravings from the early days of the modest knife work to the polished blocks of Mr. Linton’s own hand.

The only complete collection of Mr. Linton’s works are the twenty volumes which, a short time before his death, he presented to the British Museum. They contain everything of which he cared to acknowledge the authorship, and several of the books and pictures are inaccessible elsewhere. He desired to have them where they would be cared for and where they might be examined by the antiquarians and historians of the future; for he seemed to have a premonition that he was destined to become of interest to the historian. We believe that his premonition was right and that the student who, a hundred years hence, looks back to the record of engraving in England and America in

this century will find that no man did more noteworthy work or exercised a greater influence than William J. Linton. |