|

ONCE upon a time

there were four little children, three boys and a girl, who lived

near a beautiful forest. The eldest was called Dreamyeyes; the

second (the little girl) was called Brightface; the third was called

Saucymouth; and the little one of all Softcheek.

One fine spring day their mother sent them all out for a walk

in the forest; and told Dreamyeyes, as he was the biggest, that he

must take great care of the others. Away they all ran, as

merrily as possible, in great haste to get to the wood; yet for all

their hurry they stopped every minute to wish good morning to the

flowers that grew on each side of their way.

Before they could get to the wood they had to climb up a high

hill. It was a famous hill, with a number of fir-trees on the

top. In the autumn time they used to go and pick up the

fir-cones that lay strown all under the trees, and pelt each other

with them in play, for they were not hard or heavy enough to hurt;

and when they were tired of pelting each other, or when the little

ones were tired, then they all picked up the cones and carried them

home, to light their mother's fire. But now it was spring, and

there were no fir-cones. But for all that they went almost

every morning up to the top of the hill. And the top was sand,

into which their feet used to sink; and little Softcheek could

hardly get on at all, he sank so deep, so the others had to help

him up. And it was prime fun to run down again as fast as they

could through the soft sand; and if they fell ever so often they

could not hurt themselves.

This morning, when they got to the top, there was a lark high

high up in the sky, a long way above the highest of the trees; and

he was singing all the merry things in the world. And his song

came down through the fir boughs, as sweetly as the song of the rain

when the clouds touch the tree-tops. The lark flew higher and

higher, till he seemed like a speck in the clear blue sky; and then

higher still, until he was quite out of sight and they could only

just hear his merry voice; and then away ran the four children down

through the sand, on their way to the wood which grew in the valley

below and up the side of a hill directly before them.

It was a most magnificent forest, with clumps of oaks with

their old twisted branches, and long avenues of smooth-skinned

beeches with their graceful boughs drooping to the ground, and

birches with their flickering foliage and white stems like silver in

the sunlight; and there were many other trees besides. And the

great boughs arched over like the roof of some grand cathedral; and

the wind made music there; and the light played in and out among the

leaves, leaping through the green windows, chasing the wind.

When the wind blew through the leaves, in came the light; and the

wind shouted out, and the light laughed; and then the birds sang as

if they were playmates too; and the children laughed, enjoying the

forest pleasures.

And the forest was so full of all sweet sounds, the glad

voices of happy creatures! Sometimes a wood-pigeon would

whisper coaxingly from the thickest part of the beech-trees,

inviting them to come into the forest depths; and then a great

blackbird would bounce past them, singing and shouting out loud,

"I'll be there first"; and the bees sang too; and the ants went

bustling about their great loose ant-hills, and they sang, too, a

low sweet song at their work; and the green grasshoppers jumped and

sang, and sang and jumped, as if they were not quite sure how high

they could jump, or how high they could sing either; and sometimes

the frogs would pop their heads out of the water, or get out of the

pools and sit on the bank, and sing too,and very well they could

sing when they pleased; and though the butterflies did not sing they

were none the less loved by the children, for they seemed to be like

children, so happy and so loving, though they said nothing about it;

and there were the moths, quieter than any, in the dim evenings

they glided out of the shadows of the bushes, and looked so

beautiful they had no need to sing; and in this wonderful forest,

too, or rather round the margin of it, under the hedge-rows and

bushes, were the glow-worms who lit their bright green lamps for the

fairies to dance by, when the moon was busy lighting other forests.

And in this wonderful forest, too, were such multitudes of

flowers: primroses under the trees, and violets with them, in all

sorts of out-of-the-way corners; and wind-flowers living in crowds,

like flocks of little sheep, their delicate blossoms waving with the

least breath of wind; and then the forest would be full of yellow

celandine, lying like gold coin in such great heaps; and then the

hyacinths would ring their peals of blue bells under every tree, for

joy that the may was beginning to blossom; and the water-ranunculuses

lifted their white cups out of the water; and the honeysuckle and

the bryony climbed up over the shoulders of the great brambles, and

the white wild rose scrambled up after them, and the red campion

tried to lift its head as high as theirs; and then the ferns would

come, and grow up from little tiny stalks with tops like shepherds'

crooks, till their great fan-like leaves were big enough to hide the

rabbits. For there were a great many rabbits, too, in this

wonderful forest; and sometimes the children would nearly catch some

little one that had strayed too far from its hole, and then away

would scamper the little rabbit and the children after it, and

sometimes they were just in time to see its little white tail as it

seemed to tumble into its burrow.

There was one large mound, where a great many rabbits lived,

close to some of the largest oaks in the forest. There were

holes all round the mound; which the rabbits had dug, deep down in

the earth, under the roots of the oak-trees. The children used

very often to go there, and sit quietly under the oak boughs,

waiting for the rabbits to come out.

They waited a long while this morning, watching two birds

that were feeding their young ones in their nest on one of the

branches of the biggest oak. When they were tired of watching

the birds, they began to make chains of daisies, for there were

always daisies; and when they were tired of that the three eldest

children showered blackthorn blossoms over the head of little

Softcheek. There were heaps of blackthorn blossoms, that have

very little scent, and that come out into flower before the leaves

come; but they could find only one branch of the may, the

sweet-scented white-thorn, that blossoms after the leaves are out.

Brightface was the first to see it; and up they jumped and ran to

the bush, and Dreamyeyes reached up and pulled down the branch, that

Softcheek might smell how fragrant it was. There were only two

or three flowers full blown, but a great many buds, with little pink

lips, as if they wanted to be kissed. And Softcheek did kiss

them; and Saucymouth laughed; and then Dreamyeyes called gently,

"Hush! hush!" and they all listened, and heard the Cuckoo. And

Dreamyeyes said, "I was sure I heard him"; and the bird sang again,

"Cuckoo, Cuckoo!" and the children all cried "Cuckoo" too; and then

the other birds began singing; and the children began to sing one of

papa's songs.

And while they were singing under the may-bush, they saw,

peeping from behind the golden oak-buds in the great oak under which

they had been sitting, such a, beautiful face, that, instead of

being frightened, or even startled at it, though they had never seen

it before, they felt quite glad, and their eyes brightened, as if

they had seen some one they were very fond of. And little

Softcheek clapped his hands; and Saucymouth called to the lady with

the beautiful face, "Come down to us!" And the lady, who was

one of the forest fairies, slid down out of the golden branches, and

stood by them, and kissed them all, and stroked the head of

Dreamyeyes, and patted the plump cheeks of Brightface, and looked so

lovingly on Softcheek, and told Saucymouth to guess what she had

brought them. And Saucymouth looked up and laughed; and they

all guessed; and Brightface said "A fountain"; and the fairy

laughed, and said, "No"; and Dreamyeyes said, "Some flowers"; and

the fairy said, "What flowers?" And while Dreamyeyes was

thinking, Saucymouth stole behind the fairy, and peeped round again,

and whispered, "Heart's-ease."

It was the finest bunch of heart's-ease they had ever seen,

a bunch with three flowers and a little bud. And the fairy

told them it must never be divided, and by and by the little bud

would grow as fine a flower as the others; and it was not to belong

to any one of them, but to all of them together, and then it would

never die. And then Brightface turned to Dreamyeyes and said:

"We'll take it home, and put it in the lovely shell on the

mantelpiece, where the flowers die now; and then we shall always

have some in the shell." And then they looked round to thank

the kind fairy for her present; but she was gone, and they could not

see here anywhere. And Saucymouth called out, "Come back!" and

they all called, "Come back!" but it was of no use. And so

they said they would go home directly, and tell mamma what they had

seen and all the fairy had said to them, and ask papa to put the

flower in the shell. And Dreamyeyes told Brightface she should carry

it: "Because," he said, "I must help little Softcheek over the hill

again and all through the sand; and you know, Saucymouth, you must

help me to lift him over the big stones. So Brightface had

better carry it." And then they all said they wished the lady would

come again to them, for she smiled so kindly, and her voice was so

sweet and gentle; and they kept looking for her among the trees as

they walked on.

And all at once they heard a rustling in the branches, and

Saucymouth cried out, "There is the lady!" and a pretty wood-pigeon

flew out of the branches of an oak; and Dreamyeyes said, "Why,

Saucymouth, it isn't the fairy, but a wood-pigeon!" And the

pigeon flew over their heads, and right up to the top of the hill

where the great waterfall came from. And then they all ran

after it, and through the trees, and scrambled up among the bushes,

past the delicate young leaves of the honeysuckle, and Dreamyeyes

carried Softcheek pickaback, that they might get on faster, till

they reached the top of the hill. And while they were resting

there, Brightface dropped the flower into the tiny stream that made

the waterfall; and the stream whirled the flower round and round

till it was quite giddy, and then ran away with it, O, so fast, over

a lot of little stones, till it came to the edge of the rock, and

there it tumbled over, flower and all. And when Saucymouth saw

that, he threw himself down on the ground, and cried, and began to

kick, and then Softcheek cried too, till Brightface said, "it would

be very silly to make a noise, Saucymouth, for that could not bring

the flower back"; and Dreamyeyes said, "Perhaps we shall find it at

the bottom of the waterfall, or perhaps, we shall see the fairy

again, and then we will ask her to get it for us." "And if she

can't it will be of no use to cry," said Brightface. So then

Saucymouth got up, and he and Softcheek left off crying, and they

all set off to try and find the heart's-ease.

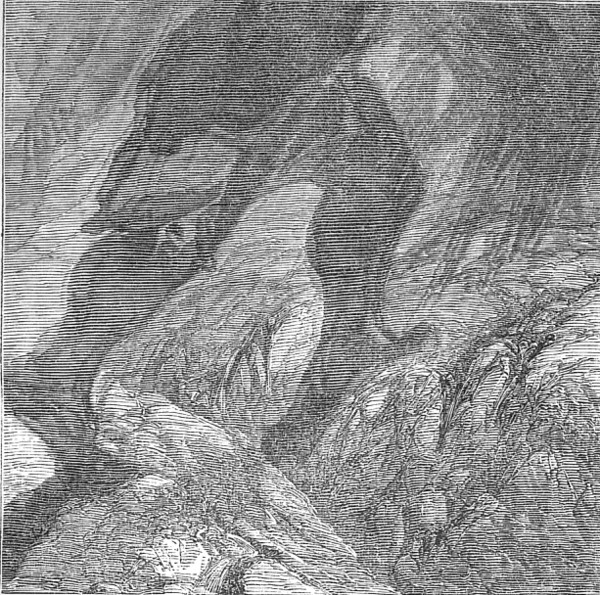

They had some trouble at first to get down by the side of the

waterfall, though it was easy enough for the stream that leaped

plump off the edge of the rock, shouting and laughing out loud, as

if it had had a good joke. And it did not leave off laughing

even when it got to the bottom, but jumped on, from one lump of rock

to another, laughing all the while so boisterously, as if it never

had had such fun before in all its life. And even at the

bottom of the fall it was very hard work to follow the merry stream,

for the rocks were very large and rough, and so awkwardly shaped;

and little Softcheek had to be lifted up, and then let down on the

other side of every great piece; and even Saucymouth, and once

Brightface, had to be helped by Dreamyeyes. But they went on

as fast as they could, looking very carefully, at every turn, into

the stream, to see if they could find the lost heart's-ease.

Then they came to a part of the hillside where there were several

little streams racing each other through the heath, till the

children did not know which was the one into which they had dropped

the flower. So they ran along as fast as the streams to the

bottom of the hill, where they found again the main stream into

which all the little ones were hurrying. But they could see no

heart's-ease. And now again there were great heaps of rocks,

some rough and some with sharp edges; and while the stream jumped

from one to another, laughing and singing, and not seeming to care

in the least how fast it ran or how often it tumbled, the children

began to grow tired; for they had to clamber over some of the rocks,

and to slide down others; and then to walk along narrow ledges, with

the water running wildly past them, and almost pushing them off, so

that they were continually afraid of falling; and then between

little walls of rock where there was hardly room to move; and over

flat, broad tables that looked very easy, but where they could

scarcely stand, because the green moss and weed that seemed like

soft grass was as slippery as ice. Even Brightface was almost

crying; but the stream went on gurgling and laughing as if it were

sobbing in fun, and after all, though it pretended to mock them, its

voice was so pleasant that they could not be angry with it, and

sometimes it slid very gently over a broad piece of slate, and

sometimes ran round a great rock quite out of its way, and then up

into a far corner, and leisurely back again, just as though it was

playing with them, and all the while sang so deliciously that

Dreamyeyes could not help singing too; and then Brightface laughed

out gladly again, and Saucymouth stepped out bravely, and they

carried little Softcheek among them over the rough rocks, and over

the slippery rocks, till at last they jumped down on the smooth

grass, and there they all ran on merrily enough, even faster than

the stream.

But now there were all sorts of things that hindered them

from making haste to overtake the heart's-ease. There were

some steppingstones across the water, and they could not help

stepping over them, though they had no occasion to do so; and

stopping to look up the stream, and then down the stream into the

larch wood, where all sight of it was lost. And then they were

obliged to track it by its song or by trees that grew on each side

of the gorge it ran through. And then, when the trees were

fewer on one side, and the little travellers could walk along the

meadows, there were so many things to admire. There were the

butterflies fluttering lightly by, as if they wanted to tempt the

children to play with them; and there were the beetles with their

shiny green backs and long, slender horns; and perhaps a bird would

fly out of the grass almost at their feet, perching on the ground

close by them, and then flying off again. Sometimes they

turned to look at the mountain where the stream was born; sometimes

they stopped to admire the feathery look of the firs, with their

filmy branches dropping like green icicles; and sometimes they went

down the bank to be nearer the sweet breath of the may-bush that was

dipping its long hair in the stream, while the little waves rippled

gently and kissingly over it, or else foamed up over some stone in

their way, till their spray was almost as white as the may-bloom.

Then they had to watch the honeysuckle just bursting into

leaf, and to think of the time when the fairies would gather the

honeysuckle's trumpet-like flowers, to blow a grand chorus for the

stars. And the wild rose, too, was about putting out little

shoots of new wood; and the folks'glove's young velvety leaves were

just beginning to peep out of the rank grass; and along with the

folks'glove were some great rocks putting their heads up as if they

wanted to ask the children about their old friends, the rocks upon

the mountains. They looked so strangely, those gray heads

pushing out among a lot of straggling, weedy hair in the middle of

the fields and some were in the middle of the water; and the waves

washed their old foreheads so clean; and all round one of them in a

corner the children found a great family of cuckoo-flowers with

their delicate pink blossoms growing out of the water, and they were

nodding their heads at the old rock and at the waves that ran by

them.

And as the children came farther on through the fields, they saw

some grand trees standing by the side of the river (for the stream

was now broad enough to be a river), and the trees leaned over it as

if they were looking at their own shadows in the water; and so, the

children stopped to look in the water; and the water was so clear

that it reflected all the blue sky and the clouds, and the children

saw their own images in it; and Dreamyeyes thought he saw the fairy

in the water; and they all leaned over to look, and there was a

beautiful face smiling up at them, through the long, smooth,

hair-like grass that was trailing along the current, as if the fairy

was floating in the river. But when they looked again they

only saw their own faces among the flags on the water; and they

thought that perhaps they had not seen the fairy there, that it

was Brightface they had seen instead. And then a little fish

seemed to fly through the clouds under the water; and the children

laughed to see the fish; and then the water laughed too, and a

little gust of wind came and blew all their reflections away.

And on went the children again. On they went through

the bright meadows, among the white daisies, and the purpled clover,

and the yellow dandelions and buttercups, and then again under long

avenues of such high trees, with the blue sky peeping through, among

the violets and the blue hyacinths and the yellow strawberry-blossom

and the little blue speedwell; and then out again from under the

trees, over yellow crow's-foot, and down to the river-side, where

the blue forget-me-not looked up at the sky through the golden

sunshine, and reminded them of their lost flower.

And the four children sat down for a while by the side of the

blue forget-me-not, in the sunshine, and asked each other where the

fairy's flower could be. Dreamyeyes said he was sure they

should see the lady again; and Brightface looked at him and grew

brighter; and Saucymouth said, "I will get the flower.

Come on!" But they would not go directly, because little

Softcheek was tired. So they rested there some time till he

asked to go on again; and then Saucymouth said, "Come on!" again,

and ran on before them through the grass. And now they saw

some cottages on each side of the river, and little gardens round

them, and clumps of elm-trees in between; and the river widened and

widened, and flowed more leisurely, as if it were a very little

tired with its long journey. And the children walked slowly by

the side of it, looking very steadfastly across it. But there

was no heart's-ease there. They looked round, and they saw the

blue smoke curling up to the sky from the cottage chimneys, and they

saw the men at work in the fields, and the waggons going along the

road, and the sheep lying on a hillside in the sunlight, and the

swallows skimming over the surface of the river; but they could see

no heart's-ease. And they heard the blacksmith at his forge,

and the carpenter hammering, and the dogs barking as they drove the

cows home, and the thumping of the flail on the threshing-floor, and

the church-bells ringing merrily; but they only thought now of the

lost heart's-ease.

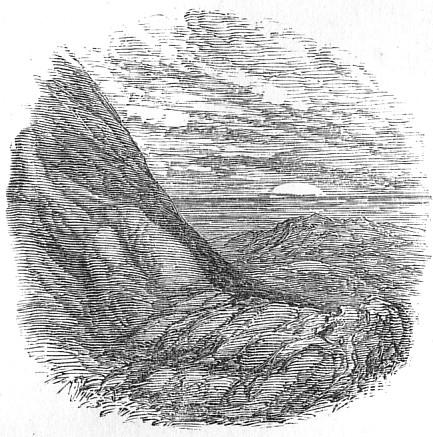

And the river widened and widened, and they grew puzzled, for they

did not know how far it might lead them; and at last they sat down

again on the grass, not knowing at all what to do. At last

Dreamyeyes looked up and said, "We will go to the top of the hill

beyond the village, and from there we shall be able to see where the

river goes to." They were soon there; and O, so glad they had

come, for they saw from the top of the hill the most splendid view

they had ever seen. There were broad masses of trees close

under where they sat, and the wide river flowing grandly below them,

and farther on more trees, great heaps with their rich spring

foliage, and the river beyond them, and then trees again; miles on

miles of the glorious river winding in and out among the trees until

it reached the sea. And just as they first caught sight of the

sea, one wide sun ray gleamed out from under a violet-coloured

cloud, and poured its light all along the river and over the trees,

so that they looked as if they were growing out of a gold mine, and

the river like melted gold running between them. And the

children sat like four golden statues on the top of the hill, with

eyes half dazzled, watching the wonderful scene.

At last, Saucymouth said, "We will come back to-morrow, and go all

the way down to the sea, and get the heart's-ease." And

Dreamyeyes smiled, and said, "We should never find it by ourselves,

Saucymouth; I wish the lady would come again." Brightface

could only look at the bright river, and said nothing; and Softcheek

asked to go home.

There the four children sat, like gold statues in the

sunlight, till it was quite evening; and then the sky grew all

bright with the golden light, and they saw the great round sun drop

gently down, like a ball of fire, behind the sea. Just before

it was quite gone, Dreamyeyes said, gently, "Look!" They all

looked, and saw, between them and the sun, a long way off, as if it

were over the sea, a lady rising in the air. It was the fairy.

They were too much delighted for any of them, even for Saucymouth,

to speak to her. There they all sat on the golden hill, as

still as statues, looking at the lady fairy. She came nearer

to them, nearer and nearer, till she was near enough for them see

that she had the bunch of heart's-ease in her hair, over her

beautiful forehead; and then she floated away again like one of the

sunset clouds, and the sunlight just touched the flower on the top

of her beautiful forehead, and made it shine like a star; and they

saw her rise higher and higher towards the sky; and, as they looked,

the flower became brighter and brighter, till at last it changed to

a star; and then the lady faded away, and they saw only the bright

star shining on them from the delicate sky,shining if so tenderly

and lovingly, as it were smiling on them, as the beautiful lady

smiled when she first gave them the heart's-ease.

The sun went quite down; and Dreamy-eyes led his sister and

his little brothers down the hill, homeward, to their mother and

father. The twilight was very pleasant, and the Star of the

Flower went before them, lighting them all the way.

The night was coming on; the sleepy flowers were nodding

their heads; the primroses and daisies, and even the tallest

buttercups, closed their drowsy eyes; the birds went home to their

nests; the dragonflies rattled past on their way to the pool; the

children saw the grey moths gliding in and out of the bushes, and

the bats flittering over their heads. Now and then some little

bird chirruped as the sound of their footsteps woke him from some

sweet dream in the tree where he loved to roost, and then he turned

round, and was asleep again almost before they had passed.

Brightface was tired, but walked on very happily, looking sometimes

at the Star, and sometimes at her brothers. Saucymouth was

tired too, but sang a merry song, and so helped on both the others

and himself. Little Softcheek put his arms round the neck of

Dreamyeyes and laid his head upon his shoulder, and went fairly off

to sleep; but sometimes he woke up, and looked to see if the Star

was still there; and then Dreamyeyes smiled on him, and hugged him

more closely. And after a little while, when Saucymouth was

too tired to sing, the nightingales came out of the forest and sat

in the trees on their way, and sang to them so deliciously such

sweet songs, like those their father sang to them. And so they

went bravely on, till they came to the old door, where their mother

waited for them. And they all ran into her arms, and she

kissed their dim eyes, and their father sang to them as they fell

asleep.

And that night Dreamyeyes dreamed that the great

chestnut-tree was in full bloom, and that every bunch of fragrant

blossom stood up, like a rosy flame, pointing to the sky, as if the

chestnut-flowers, too, hoped to become stars.

DEAR CHILDREN!

Let the elders teach the young ones that, though the

Heart's-ease be lost, it may be found again. Seek it

cheerfully; never despair; and the Star of the Flower shall light

you even homeward.

――――♦――――

ALL the long

summer day Willie had been playing and working in the garden,

running about, looking at the butterflies with their differently

spotted wings, watching the bees as they plumped headforemost into

the companula bells and came back again loaded with honey, noticing

what new flowers were in bloom, how many more strawberries and

raspberries were ripe. Some of the ripest strawberries he had

gathered and taken on a broad vine-leaf to his grandmamma; he had

weeded the carrots too; and taken the beautiful black and yellow

caterpillars off the cabbages and carried them far away to the

common, where they could do no harm. He had seen one slender

blue dragon-fly, and found the first ripe cherry. And at last,

just as the great blue beetles began to fly about, stumbling against

everybody in their way, he went to bed quite tired, and fell asleep

in the very middle of one of papa's songs. When he was fast

asleep, the moon rose behind the hills; and, after looking for some

time at its reflection in the little stream at the bottom of the

orchard, the stream where the marsh marigolds grew, it glided

through a host of silvery clouds, and came very silently to peep in

at the window of the room where the little boy slept. And

Willie, as soon as the moonbeam lighted his face, making it as

bright as if mamma had kissed him, began to dream.

He dreamed that some one had kissed him in his sleep,

and that he looked up and saw the moon shining into the chamber, and

in the middle of the moonbeams was a very lovely face smiling on

him; and he thought the beautiful lips moved, and a very sweet and

gentle voice told him to get up and come out into the forest in the

moonlight. And then he dreamed that he got up, and made great

haste, and very quietly dressed himself for fear of waking his

little brother, who slept in the same room with him; and he thought

the lovely face lighted him down stairs, so that he easily found his

way out of the house into the garden. And in the garden it was

nearly as bright as day. All the difference was, that there

were very soft shadows under all the trees and shrubs and flowers,

and that the colours of the leaves and flowers were much more

delicate than in the sunshine. The flaming cheeks of the

nasturtiums were not near so red as he used to see them, but the

tints of the lilac were more beautiful than ever.

And Willie dreamed that he went through the garden, and

across the road, and over the common among the daisies (who were all

fast asleep with their leaves close shut up), till he came to the

forest. All was so still and quiet! He could hear

nothing except the low sweet breathing of the wind among the wild

roses and honeysuckles that hung over his path. Now and then

the wind blew down a tiny rose leaf; and all was so quiet, he could

almost hear it fall on the grass. He thought the roses and

honeysuckles had never been so fragrant.

On he went, through the bright moonlight, till he came to a

part of the forest where the foliage was very thick, so thick that

the moonbeams could hardly find their way between the leaves to the

little path on which Willie was walking. Still he went on very

happily, quite sure that the lovely, smiling face was taking care of

him; and the forest branches became closer and closer, and more

crowded with leaves, till it was so dim he could scarcely see where

the path was. And just as he came to the very darkest part of

the forest, all at once a nightingale sang to him from one of the

branches close by; and the moment the nightingale sang he saw a

little green light in the long grass beside him, and he looked down,

and found it was a glow-worm whom the nightingale had called to

light him on his way. While he was leaning down to thank the

glow-worm, a great many more nightingales began singing; so many

that all the dark part of the forest seemed to be as full of music

as the bright part was of moonlight; and when he lifted up his head

to go on, he saw, on each side of his path, rows of glow-worms,

waiting to light him with their green lamps.

And then Willie dreamed that he went on, thinking whether he

should see any of the fairies carrying dew to the flowers; and

sometimes he fancied they were close to him, when the dew-drop fell

off the honeysuckle leaves as he pulled down a branch to smell the

sweet blossoms.

So he went along through the forest till the light began to

come again; and then the nightingales left off singing, and the

glow-worms put out their lamps. And there was a great sound of

wings, as if all the nightingales had flown away together; and when

they were gone the forest was so still he could almost fancy he

heard the sound of his own footsteps on the white grass. And

the dim light grew, even though the moon was now gone behind the

farthest trees; and the trees stood out like great gray shadows in

the mist; and then the clouds above, where the forest was not so

thickly overarched, were tinged with a delicate rose-colour.

And presently it grew lighter than ever, and he heard a cock

crow, and almost directly after found that he was on the edge of the

forest, in a large field, and that it was nearly morning. He

could not imagine how he should have wandered so long and so far

into the forest; and then he thought he would turn and go home,

but when he looked back to the trees, they were all so dim and

dreamy he thought he should not find his way. So he went

across the field; and as he turned round the corner of the hedge he

saw a little round, smooth hill, and on the side of the hill, among

the yellow cowslips and grass, there were some people sitting.

And Willie dreamed that they all looked very handsome and

good-natured; and so he ran up the hill, and asked them what they

were doing there. And they told him they were waiting for him

to go with them to see the sun rise, and that they must make haste,

or they should be too late.

And then Willie dreamed that he went with all the people over

the hill, and down the other side to the edge of a great river; and

there, fastened to a willow that was hanging over the water, he saw

two little boats. And he and some of the people got into one

of the boats, and the rest of the people got into the other; and

they untied some brambles that had held the boats, and the boats

began to float very smoothly down the stream. And there was a

light mist hanging about the river, so that the great trees standing

on the banks and all up the hills on each side, though the moon was

gone, had still a very moonlighty look in the grey morning; for the

sun was not yet up. But there was one pale star in the east,

showing them which way the sun would come. And the river was

all full of white and yellow water-lilies, the largest flowers

Willie had ever seen; and their great broad flat leaves he thought

were nearly big enough for boats; and a little sky-blue dragon-fly

was asleep in one of the white lily-cups.

While the boats glided down the river, the people in them sat

just as they liked, and did nothing but sing; and Willie wondered

how it was they knew all papa's songs, for they sang them all to

him, and he sang with them.

After a very little while the two boats stopped against the

bank in a bend of the river, under a great tree; and all the people

got out, and began to climb a hill on the opposite side of the river

to that where Willie had first seen them. And then Willie

again heard a cock crow; and the people took hold of his hands, and

they all ran together to the top of the hill, just in time to see

the sun rise. And then the good people sat down on the top of

the hill and had some breakfast; and they gave Willie some bread and

honey, and some strawberries, and some milk for his breakfast; and

when they all had enough, they asked Willie if he would go any

farther with them.

And so Willie dreamed that they went on together through the

fields. And the fields were all full of very strange flowers,

with scarcely any colour in them; and there were long rows of trees

and hedges of a very pale green all round the fields; and they

walked through a great many fields, and over a great many very high

stiles; and the birds kept chattering; and the wind blew; and the

people talked very fast in a language that Willie did not

understand. But whenever he felt as if he were going to be

frightened, they smiled on him, and spoke so that he could

understand them, and then he was very glad to go on again with them.

At last they came to a village. They went through a

farm-yard, and so into the road, and up a rising ground to the

houses. It was a very beautiful village, very nice cottages

with roses, and jessamine, and clematis, and vines, and fig-trees,

growing all over them; and round each cottage a little garden full

of cabbages and peas and sweet-scented beans and all sorts of

flowers and fruit-trees, and a broad road between them, with, rows

of trees on each side; and the bees were singing in the gardens, and

such hosts of butterflies sporting everywhere! And it seemed

to be a grand holiday, for everybody was coming out of doors, and

they all wore their best clothes, and looked as bright as the

sunshine itself. And some of them had bows and arrows, and

some had long thin swords, and some had music, and they were all

very busy; and then Willie dreamed that he and the people who were

with him went and walked along with all these other people, singing

papa's songs, till they came, a very little way from the village, to

a large common. And then he and a great many more of them sat

down on some seats that had been made of turf, and the games began.

First, at one end of the common they set up a target, painted

all the colours of the rainbow, and white in the middle; and a great

many boys came with bows and arrows, and shot at the target, and

several went very near to the white, but only two or three of them

could touch it. And then Willie dreamed that he shot at the

target, and after trying a great many times he hit it in the very

middle of the white. And all the people clapped their hands,

and said he was a very good boy, all except one little old man

with a very dark face, and he came and said to him very kindly, "You

know, Willie, you are dreaming."

And then they all went and stood on the two sides of the

common, and left a clear place in the middle; and at one end they

hung up a crown of daisies and then all the boys set off running,

and Willie tried very hard to keep first; and for a little while he

got on very well; and then some one seemed to be pulling him back,

and everybody ran past him, and he could not get on at all.

And then he thought he left off being tired, and ran on so fast that

he passed every one, and got the daisy-crown, and then he saw that

the daisies were all shut up, and the little man said, "You are

dreaming, Willie."

And then he thought a great many of the boys stood up for a

wrestling-match, to try which were the strongest. And two very

beautiful boys, the one who had shot nearest to the middle of the

target, and the one who had run fastest next to Willie, stood by to

see that they played properly; and then they wrestled together, and

tried to throw each other down. And when all the bigger boys

had done, Willie went and wrestled too, and his foot slipped, and he

fell flat down on his back; and then, while he was getting up, the

little man came to help him, and smiled very kindly on him, and

said, "Never mind, Willie! you know it is only a dream."

And then some of them brought the long thin swords, and the

boy who had wrestled best sat down in a chair; and they gave Willie

some of the swords to hold; and two of the biggest boys began to

play with the swords; and when one touched the other with his sword,

the boy in the chair gave the winner a crown of heart's-ease to

wear. And then two other boys came and played with the swords;

and every time one touched another with his sword, and the boy in

the chair got up to give him his crown, the little old man came up

to Willie, and patted him on his head, and kissed him, and pointed

to the winner, and said, " It is nothing but a dream, you know,

Willie."

When they had done playing, a great many beautiful children came

running on to the common with their pinafores full of flowers; and

they began to pelt everybody with the flowers, and to throw them

about in all directions; and they never seemed to empty their

pinafores, but as fast as ever they threw the flowers out more

flowers came there, till the whole common was covered with them.

And the children ran before everybody, throwing the flowers all over

the road, and all the people set off to go home through the flowers

that covered their feet and reached nearly up to their knees.

And then some trees all at once grew up among the flowers; and the

trees were all covered with pink and white blossoms; and then a gust

of wind blew off all the blossoms, and the trees were all covered

with ripe fruit; and just as Willie and the people were going to

pick some of the fruit, another gust of wind blew it all off the

trees, and the plums and pears and apples and peaches and greengages

rolled all about the road, and the little children picked them all

up, and ran away laughing with them; and then a great many laughing

larks began to sing papa's songs in the branches; and then another

gust of wind blew all the leaves off the trees, and the birds flew

away, and it began to snow very fast. And the wind blew very

loudly, and the snow flew about in all directions, so that Willie

could not see his way; and then the good old man with the dark face

took him on his back, and carried him through the snow to a little

house thatched with grass; and just as they were going under the

door, Willie saw the sun rising behind the house; and when he was

about to ask the little old man why the sun was rising again, he

heard mamma say, "Why, Willie, boy! will you never get up this

morning?" And then he looked up and found that he was lying

snug in bed, and the sun was shining in at the window.

――――♦――――

EVENING came

again, with the long shadows. The great troop of rooks flew

over the garden, on their way to the elms in the churchyard, the

last one was gone by; the great long-legged heron was just off for

his night's fishing; the little white moths glided out from under

the vine-leaves that grew round the window where mamma sat, singing

the baby to sleep. Willie came and kissed them both, and ran

back to his little bed, and was soon asleep too. The pale

stars came out very slowly, one by one; and the evening primroses

opened their yellowish flowers in the cool quiet of the fragrant

twilight.

And Willie dreamed that he had grown up to be a man, and that

he was walking in a very large garden; and he thought he carried on

his shoulder a long pole, with a great bunch of ripe purple grapes

hanging from each end of it. And he had a pitcher in his hand,

into which he wanted to squeeze the grapes, for he was very thirsty;

but yet for all he could do he could not help walking on

continually, so that he was never able to set down the pitcher to

squeeze the grapes into it. And then he dreamed that he was a

boy again, walking through some cornfields with a beautiful little

girl. And he thought he had given her one of the bunches of

grapes, and that he had lost the other; but he did not care anything

about it, or about the pitcher, for he had no time to do anything

except to look at the blue eyes of the little girl who walked beside

him, and at the blue cornflowers that grew in among the golden corn.

And he thought they walked for a long while through the field,

without ever seeing the end of it; and the little girl talked and

laughed with him; and sometimes she stopped to tell him to look at

the cloud-shadows which the warm wind every now and then blew across

the bright cornfield; and then he thought instead of the blue

corn-flowers there were a great many red poppies growing in the

corn, and presently there were more poppies than corn. And

then he thought they sat down on a bed of red poppies, and he

gathered an armful of their great flowers, and made two crowns of

them, for himself and the little blue-eyed girl; and then they fell

fast asleep, just as the ripe corn was getting almost as red as the

poppies, in the cloudy sunset.

And then he dreamed that a cold wind woke him, and he found

himself alone in a wide place, in the grey of the evening; and he

could see no houses anywhere, and only a few stunted trees.

And there were no stars, nor moon, nor sun, but a dim sort of

twilight that made the trees and the ground and the clouds all one

dull grey. And the clouds hung so low that sometimes he almost

walked through them. And he was standing by the side of a

broad stream that was flowing very slowly. And he thought he

wanted to go across the stream, and so he walked into the water, and

went in deeper and deeper, hardly able to stand against the current,

which, though slow, was very strong, till he was nearly in the

middle; and then the stream lifted him off his legs, and carried him

head foremost for miles and miles and miles, past very long rows of

willow-pollards, all of one height, that stood on each side of the

stream. And he thought he could not help counting the willows

as he floated along the water; but whenever he counted near to a

hundred, he forgot the number, and had to begin again.

And so he went on for a long while; and then the stream began

to run faster and faster, till he went so fast that he could not

count the willows; and then all at once he went down a waterfall,

where he kept falling and falling, till he thought he never should

get to the bottom. At last he did get there, and found himself

on a smooth floor, strewn all over with soft gold sand, in the midst

of a great many tall white coral pillars, that reached up to the

roof. And the roof was made of water-lily leaves, with blue

sky and sunshine peeping in between them.

And he walked on a great way under the water, looking at the

gold and silver fishes playing among the lilies over his head.

And then the sun set, and while it was setting it made all the coral

pillars red, and the gold-fishes looked like flashes of lightning,

as they leaped in and out among the lily-leaves and the purple

evening clouds. And then the stars came out, and turned all

the coral pillars white again; and the stars looked like white

lilies among the leaves. And then the full moon rose, and hung

for a moment over the lily-leaves, till they looked like green ice,

and their long stalks like icicles, and the green light slid all

down the sides of the white coral; then the moon seemed to melt a

great hole in the green ice, and all the water rushed in like a

waterspout. And Willie thought that the water knocked him

down, and he had to scramble up again, out of a heap of very

beautiful shells, of all sorts of strange, shapes, and of all the

most delicate colours possible; and some of the shells were playing

such delicious music!

And then he thought he rose up through the water, and the

fishes swam all about him; and after a little while his head reached

the top, and then a lady took hold of his hand, and helped him out

of the water. And as he stood on the bank, in the moonlight he

turned round to look at the lady, and she was floating over the

water, as if she were almost water herself; and everywhere, as she

moved, an arch like a rainbow moved with her. He called to

her, but she did not answer him, though she seemed to beckon him

again into the water; and before he could even think whether or not

he should try to reach her, she had faded into the moonlight, and he

was alone again. And when he looked round, he saw that he was

on a very little island, in the middle of the sea; and he walked

across the island, and found the opposite side was very rocky; and

the waves were singing up and clown the shingle as the tide came up,

and the creamy foam broke over the rocks a long way above his head.

But in one little bay the water was so clear that he could

see the green and the black and the red and white sea-weeds growing

like great forests, out of the rocks, far underneath; and their

branches waved when the water moved, just as the boughs of the tall

trees wave in the wind. And the rocks on shore were covered

with flowers, the yellow sea-poppy, and the blue holly, and the

purple onion blossom; and, farther up, the little yellow rose and

the purple heath, all growing in the sand on the rocks. And

then the sea came up higher and higher, and he had to mount the

cliffs till he came to some patches of folks'glove and wild

heart's-ease. And then he found a cavern, hollowed all under

the ground, and he went in; and the cavern went down very steeply,

and he wandered on a great way quite in the dark; and then it became

a little light (just light enough for him to make out very dimly the

forms of some trees and hills); and then several rays of light came

down through a great cloud, and there seemed to be steps in the

rays; and he climbed up them through the mist, for though the steps

themselves were only mist they did not give way under his feet, but

bore him up, with a pleasant springy feeling, like the softest

possible moss or close turf, till he got to the top of the cloud,

and there, a long way up in the clear blue sky, he saw a number

many more than he could count of angels, all clothed in white,

with silver harps in their hands. And he heard them singing;

and their song sounded like the song of the shells and of the sea

only far more delightful.

He thought he never could hear enough of that song. And

then he looked back to the clouds, and as the wind every now and

then blew them aside, he saw the grey mountain-tops peeping up

between them, and then patches of green with the sunshine on them;

and then he saw down into the valleys, and was able to make out

quite plainly the fields and woods, and rivers, and great lakes, all

lying like a silver map in the sunlight. And on one of the

highest of the mountains he saw a lady sitting among thorns and

brambles. There she sat till the sun went down; and then the

evening star poured one bright ray down on her head, and a great

rosy light like the aurora borealis came up out of the sea, so

bright that the lady was obliged to shade her eyes with her hand.

But still she sat there looking so patient and so serious, as if

watching for some one who would not come, till the light filled the

whole sky, growing brighter and brighter, so that Willie was half

blinded and bewildered with its brightness. And as the cloud

upon which he stood melted in the rosy splendour, he found himself

close before the beautiful lady on the mountain-top; and it seemed

to him that she had the blue eyes of the little girl who used to

walk with him in the cornfields, only she was so much older and

grander, and more womanly; and her voice was sweet and gentle as the

voice of the blue-eyed girl, as she asked him why he had left the

cornfields and the coral palaces to climb among the clouds to the

barren mountain-top. And as she spoke all the sadness went out

of her beautiful face, and she smiled on him, and put forth her hand

to take his, and leaned her beautiful face forward till her hair

hung over his forehead.

When Willie awoke his cheeks were wet with tears, and he was

sad, though he did not know why. He seemed still to hear the

wonderful harmonies of the silver harps and the voice of the

blue-eyed lady. Was it only that the moon was just stooping

down behind the forest, and that the birds were singing merrily in

the rosy dawn?

――――♦――――

JACK was a good

boy, and very fond of his mother; but he did not know how to make

bargains. So what do you think he did when his mother sent him

to sell her cow?

But first I must tell you about Jack and his mother, who

they were, where they came from, where they lived, and what they did

for their living.

Well, Jack's mother was a very poor woman; and you may be

sure Jack was of the same family, and no richer. No one could

say where they came from, because Jack's mother had not told

anybody; neither had Jack, for Jack did not know. They lived

in the country, in a very neat little house, with a pretty garden

and a few trees about it. It was not far from the roadside;

and in front of it was a pond where Jack's mother's ducks used to

swim and wash themselves. Jack's mother kept chickens, too, as

well as ducks, and a pig, sometimes two pigs, and a red cow, and

a tortoiseshell cat. The ducks and chickens laid eggs; and the

red cow gave milk, of the cream of which Jack's mother made butter;

and the butter and eggs Jack took to market. They made bacon

of the pigs, and very good bacon it was. The tortoiseshell

cat, too, was good, though not exactly good to eat; but she caught

mice, and ate them. Jack was very fond of the tortoiseshell

cat; and puss was fond of him in her cat way, and liked to sit on

his knee or his shoulder, or to follow him about the garden when he

was at work in it. There was a little redbreast that also

followed him in the garden, and was on good terms with him and the

cat.

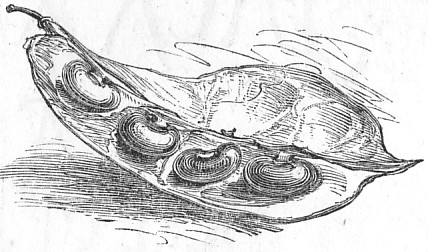

Jack was a capital gardener. He grew potatoes, red champions

and ladies' fingers and first and second earlies; and carrots,

fine, long, straight orange carrots; and cabbages, sometimes

purple cabbages for pickling, and broccoli; and spinach; and peas,

and beans, that is broad beans like these. But there was one

sort of beans called scarlet runners, which, he had been told, grew

up to a wonderful height, almost to the sky. These he had

not been able to get; and if there was one thing more than another

that Jack longed to see growing in his his garden (for he was very

proud of his garden both for its beauty and for its use to his

mother and himself) it was some of these giant scarlet runners.

And this reminds me that you are wanting to know what Jack did when

his mother sent him to sell her cow.

But why did his mother want to sell her? I will tell

you. Last year the potatoes were nearly all spoiled. So

Jack's mother was not able to keep a pig. So they had no

bacon. So they were obliged to eat their butter and eggs

instead of sending them to market. So they had no money to buy

clothes or to pay the rent of their house, for the cottage did not

belong to them. And so they had to sell the cow.

Then Jack's mother bade good-bye to the cow (for she was very

sorry to part from her); and as Jack was setting off his mother said

to him, "Now, Jack, dear! do think of what you are about, and do not

sell the cow unless you can get a good price for her."

Away went Jack with the cow to market, but before they could

reach there they met the butcher. "Good morning!" said Jack:

"Good morning!" said the butcher. "Where are you taking the

cow?" said he. "I am taking her to market, to sell her,"

answered Jack. "How's that?" said the butcher. So Jack

told him all I have told you,how they wanted money, and must sell

the cow, though they did not like to do so. "Well!" said the

butcher, "how much do you want for her?" "I don't know," said

Jack, "but my mother told me not to sell her unless I had a good

price for her." "Will this be enough?" said the butcher,

showing him a handful of money. Jack saw it was a great deal

more than he had ever had before; so he did not stop to count it,

but said directly, "I think it would." "You shall have it,"

said the butcher, "and you need not go any farther." "I should

like to go to the market, though," said Jack, "because I want to buy

some beans, some very beautiful beans, that grow up nearly to the

sky; and I think if my mother saw some of them growing in our garden

she would not be so sorry for losing our cow." "O, you mean

scarlet runners," said the butcher; and he pulled a few of them out

of his pocket. "O, how beautiful! said Jack; will you sell me

some? have you any more?" "No! these are all," said the

butcher; "but I'll sell you them; only they are very dear!"

"You shall have the cow for them instead of for your money; take the

money back, and give me the beans!" said Jack. So the butcher

took back his money, and gave Jack the beans, and wished him good

morning again, and walked away whistling and driving the cow before

him. And Jack ran home with the beans.

When he got home, his mother was gone to a neighbour's; so

away he went into the garden, and dug a piece of ground, and sowed

the beans. And as his mother was not coming home till late in

the evening, he went to bed, and left telling her about his great

bargain till next day.

In the morning he was up with the sun; and the first thing he

did was to run into the garden to look where he had sown his beans.

He did not expect to find them growing, but to his astonishment not

only were all above the ground, but some three or four of them had

twined round each other and grown up so high that Jack could not see

the tops, which indeed were quite hidden in the clouds. While

Jack stood wondering, and looking up at them, he fancied he saw a

bunch of scarlet blossoms a long way up. That was stranger

still, for the beans to grow up to the sky and blossom too, all in

one night. So he thought he would climb up the stalks, to get

the blossom to show to his mother. He put his foot on one of

the cross stems, and found it quite strong enough to bear him; and

up he went.

When he was nearly as high as the tops of the trees he missed

the blossom; but he saw some higher still, and so climbed up

farther. Then he lost that bunch, and climbed again toward another,

and so up, up, up, right through the clouds, climbing and climbing

till he was tired, and, looking down, could not see his mother's

house, nor the fields, nor the road, nor the tree-tops, nor even the

great mountains. There was nothing but cloud below him.

And then he looked up; and there was such a splendid bunch of

scarlet blossoms that he could not help going on again.

Just as he reached it (and he had to go into the cloud

to come at it), the wind blew away the cloud, and he found that the

bean-tops were hanging over a road-side; and in front of him, some

way along the road, was a very strange-looking house. He was

not sure, at first, but what it was the head of a giant looking at

him; and the windows looked like the giant's two eyes. Then

all at once he recollected how his mother had used to tell him about

a giant, and what he had done to her and to Jack's father,how they

had once been very rich, 'till the giant came and took away all they

had. Jack thought to himself, perhaps that is the giant, or

at all events, his house; it's quite big enough for a giant's home.

I'll go there and see if I can find anything belonging to my mother,

and make her rich again. So he stepped off the bean-stalks

into the road, and walked toward the giant's house. And then

he saw that the sun was very low, and the night coming on; for he

had been all the day climbing up the beanstalks without thinking of

the time, and now he was hungry.

At last he reached the house. There was a little ugly

old woman at the door, and she asked him what he wanted. Jack

said he would be very glad of anything to eat. So the old

woman gave him some young bean-pods cut up small and boiled, which

he found were very good. Then she asked him if he wanted

anything else. "Yes!" said Jack, "I want to know if this house

belongs to the giant who robbed my mother."

"I know nothing about your mother," said the old woman; "but

this is the giant's house, and the giant is coming home directly;

you had better not say such things to him. There!" she went

on, "get away into that cupboard, for if the giant finds you here he

will beat us both. You wait there till he goes to sleep after

supper; and then, as soon as the Moon is up, you can run off and get

down the bean-stalks again."

Then she pushed him into the cupboard, and went to make the

supper ready. In came the giant, very tired, and very hungry,

and very ill-tempered. He was such a big fellow that his head

almost touched the ceiling. Down he sat in his chair, such a

bump that Jack thought the floor was breaking in. And then he

bawled out for his supper so loudly that Jack was obliged to put his

fingers in his ears. When he had eaten a very great supper, he

shouted out again for the old woman to bring him his two MONEY-BAGS.

The old woman brought them, and put them on the table before him.

And the giant emptied a great heap of bright gold coins out of one,

and a heap of silver coins out of the other, and counted them, and

laughed, and said very loudly to himself, "Jack's mother shall not

have these again!" And then he put all the coins into the bags

again, and tied up the bags and leaned back in his chair, and fell

asleep, and snored like thunder. Jack knew by what the giant

said that the money belonged to his mother; so as soon as the moon

shone through the window he slipped out of the cupboard, laid hold

of the bags, popped one under each arm, and ran out of the house

along the road to the beans, and down the bean-stalks as fast as he

could till he was at home again.

His mother was so glad to see him, and gave him his supper,

and got him to bed. It was very late next morning when he

awoke. But as soon as he had finished his breakfast he said,

"Mother! I shall go up the bean-stalks again." "What

for, dear?" said his mother. "To see what else of yours the

giant has," said Jack. Then his mother was frightened, for she

recollected what a terrible big strong fellow the giant was; but

Jack said he was not afraid. He would not go to the house till it

was nearly dark; and he would hide himself, so that the giant should

not see him. Off he went, but this time he took with him

something to eat, so that he got on faster. Still for all that

it was evening when he reached the top of the beans; and when he

stepped down into the road he could hear the noise the giant made

eating his supper. So he had to make haste.

As he came near to the house he heard the giant roar out to

the old woman to bring him his HEN THAT LAID THE

GOLDEN EGGS. Jack made more haste. Luckily, as it

was summertime, the giant's door was left open; and in slid Jack,

into the great dark hall, and peeped through the hinges of the

kitchen door, and saw the giant sitting at table, with a beautiful

little grey hen before him, and in his hand a golden egg which the

hen had just been laying. The giant sat looking at the hen;

and presently his great eyes began to wink, and then to shut, and

his head began to nod. So Jack knew there was no time to be

lost; and he stepped quietly into the room, and the hen flew down on

to his hand, and he took her under his arm, and, not caring for the

golden egg, ran off as fast as he could through the moonlight.

His mother was sitting up for him, and very much frightened

about him; but she was too glad to have him again, and the hen with

him, to scold him for being so long. But she begged him never

to go any more up the bean-stalks. Jack asked her if the giant

had anything else of hers; and, as she could not deny that he had,

Jack next morning started again. The beans were now all full

of blossoms, and as Jack went up his wonderful ladder the sun shone

so brightly on the scarlet flowers, he could not help stopping

sometimes to admire them, so that it was late again when he got to

the giant's road.

The sun was down, and all was hushed and quiet. As he

came near the house, he was surprised to hear some most gentle and

delicious music, the sweetest he had ever heard in his life.

He went on slowly, listening, walked through the moonlight into the

giant's house, and there, before the giant, stood a delicate-shaped

HARP, which had been playing the giant to

sleep. Now the music ceased; and the great giant began to

breathe heavily, with a sound like the rush of the tide on the

sea-shore.

Jack recollected the wonderful harp of which his mother had

talked to him when he was a very little child, telling him how it

played of itself, and better than any one could play it, and how

much more she cared for it than for the money-bags, or even the

beautiful hen that laid the golden eggs. So Jack took up the

harp. But, the moment he touched it, it began to play again,

such a merry tune that the giant opened his great heavy eyes and

stared sleepily at Jack.

Jack did not look twice at him, but ran off with the harp

faster than he had ever run before; down the bean-stalks, hardly

knowing or caring where he set his foot, as fast as he could

scramble down, the harp twanging merrily all the while, and Jack's

heart beating as fast as the music, till he was on the ground again.

He did not dare to look back till then. Then he did; and high

up in the clouds he saw one of the giant's feet, like a great black

cloud, coming down the bean-ladder. There was his father's axe

lying on the ground; so he set down the harp, snatched up the axe,

and began to chop away at the bean-stalks. They were very

thick and tough; and it was dark, for the clouds had come over the

moon; but he worked manfully on. At last he cut them through.

There was a tremendous crash, like a clap of thunder, as if the

giant had fallen; and Jack ran into the cottage with the harp.

All night long there was a terrible storm and uproar.

Sometimes, when the wind blew fiercely, he thought the giant was

shaking the house-walls. But at last he was so tired that he

fell asleep. When he awoke next morning the beans were all

blown away. He never saw or heard anything more of the giant.

But his mother had the money-bags and the hen with the golden eggs;

and so they were able to buy clothes and bacon, and another cow, and

whatever else they needed to make them comfortable. And Jack

kept the harp (his mother gave it to him), and had music for all the

rest of his life.

――――♦―――

"'TWOULD be a

grand thing to kill a giant" thought Jack. It might have been

the same Jack who climbed up the bean-stalks, but I do not know.

"'Twould be a grand thing to kill a giant!" So, instead of

minding his work, he went to look for one.

Very hungry he was, and tired, before the day was out; but

not a giant came in his way. It was just in the dusk of the

evening when he heard a rumbling behind him. It might have

been from a stone quarry on the other side of the hill; it might

have been a giant grumbling because Jack went so fast that he could

not overtake him, for Jack wore seven-leagued boots, and was a match

for any one at running. The rumbling came again, and then Jack

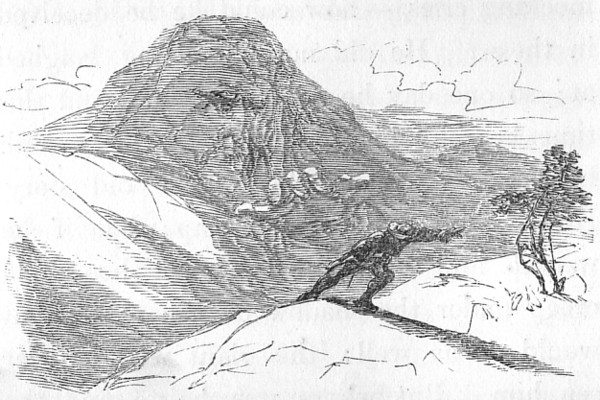

turned to see what it was. Sure enough there was a giant

looking over the top of the hill, and a terrible fellow too; with

a head as big as a mountain-top, and lowering eyebrows for all the

world like bushes overhanging great clefts in a rock, so deep and

dark you could see no eyeballs in them. He seemed to be

smoking a pipe too (very likely, as it was evening), for a thin

cloud was curling up where his mouth should have been. Ay,

what a tremendous fellow the giant was! Half a mile high he

looked, at the very least. "O," cried Jack, "I wish I had my

sword of sharpness." "O, sword of sharpness," shouted the

giant back; not so loud, though, as Jack, but like his echo, "sword

of sharpness," as if he were mocking him. "O," cried Jack

again. And the giant did the same. Jack's courage was

gone; and he ran away home as fast as his seven-leagued boots would

carry him, never once looking to see if the giant's arm was

stretched forth to reach him.

He minded his work for a day or two but he could not forget the

giant. "I never thought there were giants so big as that,"

said he to his playmates and school-fellows. No more did they;

and he was only laughed at when he talked of the Giant Half-a-mile

high.

Perhaps the laughing only made him more fixed in his opinion.

It was a giant. He saw him so plainly that he could not have

mistaken him for anything else; and then the smoke from his pipe,

and the mocking cries, how could he be deceived in these? He

did not like being laughed at; so one day he set off again.

And this time he took his sword of sharpness with him, like his

namesake in the old story. He had not an invisible cap; but if

he waited for the evening, when he could creep under the shadow of

the rocks, that would do as well: the giant would never see him.

But where was he to find the giant? He could not even be sure

of the exact place where he saw him; for at first he was not

thinking of anything, and afterwards he was too frightened to take

much notice. However, he had a half-holiday, wandered all the

afternoon, saw no giant; and when it grew dark was obliged to wait,

for he could not find his way home. So he plucked up as good a

heart as he could, though he was afraid to whistle for fear any

giant should hear him, and sat down, leaning against a large rock to

watch. No one came. Once or twice during the afternoon

he had thought he heard the giant growling; but it was a long way

off. Now all was quiet. After a while he ate his supper,

which be had been thoughtful enough to bring with him. Then he

walked about a little to prevent himself from falling asleep; then

he sat down to rest himself.

He had scarcely seated himself when he was sure he did hear

the rumbling, and, looking up, he saw not the giant's head, as

before, peeping over the hill, but the end of a foot, almost

directly over him, as if the giant was going to step from the crag

under which brave Jack was sitting. What a foot! almost as

large as a house. Jack was too frightened to draw his sword of

sharpness; but, instead, crouched close down under his bit of rock.

But if the giant's foot had come upon it, the rock and Jack and all

must have been crumbled to powder. Fortunately the giant did

not step directly down, but strode with one wide step right across

the valley, setting his foot at once upon the opposite hill; Jack

saw him pass over, two enormous legs; the body was high up in the

clouds.

Whether Jack fainted with terror or fell asleep he never knew.

It was morning when he woke up, pale and faint, and his teeth

chattering. Little breakfast he was able to eat when he

reached home. And when he told his story (everybody knew he

would not say an untruth) all his companions, except some few who

thought he had been dreaming, gave over laughing at him, for a giant

as big as that, you know, was no joke at all. Suppose he came

one day and set his foot on the school when they were all in it, or

kicked over their fathers' houses. It was hardly safe to go to

sleep now.

Jack thought so too. But the first penny ever given to

him he had spent in buying the old story of "Jack the Giant-Killer"

(which, indeed, had first set him giant-hunting), and now, spite of

his fear, he could not help wondering whether the old Cornish giant

was as big as this one of his. If so, even yet he might be

killed. And then he would be Jack the Giant-Killer too,

Giant-Killer the Second!

So one day he again ventured out. He was, after all, a

brave fellow, and if he could but find the giant! Once more he

had a long day's wandering. At last he thought he found the

very hill over which he had first seen the giant's head. He

climbed boldly up the front, then crept on all-fours to the top and

lay down in the fern to look over. It was evening,

the shapes of the mountains were already growing indistinct;

but surely he could not mistake what lay beneath him, some little

way down the hill. It was a giant form, ay! of a man dressed all

in green, except that he had a purple sash round his waist and a

purple cap drawn down over his face. He lay on his back, with

his knees rather up, and his arms under his head. It was the

giant, and asleep.

Jack looked a long time intently on him; he did not move, nor

did he seem to have any weapon. He was certainly asleep then,

and unarmed. Jack drew his sword of sharpness. He

listened: there was no sound but what might have been either the ebb

and flow of the distant sea or the giant's heavy breathing. He

crept slowly down through the fern to the giant's side.

Evening was darkening round him, and in a little while he would not

see even the giant,what if he should fall up against him and

disturb him; the giant roll upon him, or snatch him up? He

kept his eyes fixed on the purple sash of the giant, that he might

guess where the great fellow's heart was. It would never do to

miss his blow.

At last, stepping noiselessly over the turf, he was at the

giant's side, and thrust his sword of sharpness up to the very hilt

into him, with such force that he could not draw it back again.

The giant never moved nor groaned. The one blow was enough.

Brave Jack!

But now it was quite dark, and Jack did not like the thought

of staying there with the dead giant. So, leaving the sword in

him, he returned home.

Early next morning he summoned his friends to come with him

to the scene of triumph, some few of them to be favoured by first

witnessing the monster. Then Jack would draw out his sword,

and they should rouse the whole village to carry the body off.

Would it not be a glorious day?

They reached the hill-top whence Jack had first espied him.

They all stopped: he pointed down. Why, Jack! your giant is

only a part of the hill, and the cap and sash are great patches of

the purple heath!

Jack never went giant-killing again; he thought it a waste of

time.

――――♦――――

THE three people

were an old woman, a man, and a little girl.

The old woman had an egg for supper; and when she had broken

off the top she found it was not done enough. How was that to

be mended? The little girl brought a sauce-pan, but the

trouble was to put the egg into it. They made a noose in a

piece of string, put it round the egg-cup, and let the egg-cup, egg

and all, down into the saucepan, and then set the saucepan on the

fire.

After a little while they took it off, to see if the egg was

done. Not a bit, and all, no doubt, because they had

forgotten to put the egg's end on. So they set the end on, and

the saucepan on the fire, and presently looked again. But the

water had all boiled away, so the little girl had to go for more.

She was a very clever child, and brought hot water and did not the

egg wabble about in it, and make them all three quite nervous for

fear the egg-cup should be overset and the yolk run out!

After half an hour or so they thought it must be done.

But the difficulty was how to get at the egg for eating. The

old woman said she would pick it out; but they told her she would

scald her fingers, and perhaps spoil her gown. The man said,

"Set it down outside the door to cool!" but then the dog might run

away with it. The little girl talked of boring a hole in the

saucepan, and so draining off the hot water. She was a very

clever child, but they had nothing to bore the hole with.

At last the man held the saucepan over the hearth-rug, and

the old woman and the little girl took each a spoon and lifted the

egg safely out of the egg-cup into the old woman's lap. And

the old woman made an excellent supper, for all the egg was rather

watery, which she said made it more like a duck's egg; and there was

prime egg-broth left in the saucepan for the cat.

――――♦――――

"O, HOW nice it

would be to be a kitten! Just think, Maggie! No lessons,

no sewing, no scolding, no chilblains. Nothing to do but to

lie cozily on the hearth-rug before the fire, and be petted, and

play with her tail. Don't I wish I was a kitten!"

"I wish I was anything else," said the kitten, looking up in

the little girl's face.

"Just listen, Maggie! to the foolish thing! Why, you

naughty, wicked, ungrateful, silly little puss! Here I've been

nursing you in my lap nearly all the day; and if I did let you fall

twice, you did not hurt yourself, for you only fell on the carpet.

And I wrapped you up in my best frock. And you've nice milk

and bread. And your mother is so kind to you. Why, she

brought you a mouse the other day, nasty thing! And she lets

you do what you like with her, and is never angry with you, or cross

as our governess is; and you've no clothes to mend, because you

can't tear your clothes; and no spelling; and you're not washed of a

morning in cold water; and "