|

THE OLD FIDDLER.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I.

|

The traveller stops and gazes round and

round,

O'er all the scenes that animate his heart

With mirth and music. E'en the mendicant,

Bowbent with age, that on the old gray stone

Sole sitting, suns him in the public way,

Feels his heart leap as to himself he sings.

MICHAEL

BRUCE. |

IT was not quite

eleven in the forenoon as Lobden Ben sauntered along the road

towards the head of the Clough, near Healey Hall, as happy as the

summer day. And right well did that jolly-hearted besom-maker

harmonise with the scene around him. He was a healthy, hardy,

comely fellow, just in his prime, as clean as a new pin, and

dressed in his holiday clothes, freaked with such bits of rustic

prettiness as his little garden and his native fields afforded.

He looked like "a man of cheerful yesterdays," and hopeful future.

|

Embroidered was he, as it were a mead,

All full of freshι flowers, white and red,

Singing he was or fluting all the day:

He was as fresh as is the month of May. |

The day was hot, and Ben was idle, and, as it still wanted more than

an hour of noon, he paced the road with a slow, wandering gait.

His hat was thrown back from his broad forehead, and in his right

hand he carelessly swung a green branch, as he chanted aloud,

|

Be merry while it's day, my lads,

'Twill soon be set o' sun;

An' fate will have her way, my lads,

Let a mon do what he con!

What he con!

Let a mon do what he con! |

Then, wiping his moist forehead, he lounged onward in silence for a

few yards. But he was too glad-hearted to be silent long, and,

according to his wont when thus wandering alone, he began again to

interweave the quiet thoughts that played about his mind with quaint

threads of the minstrel memories of days gone by. Like a

fitful bird in the summer woods, he chanted as he went, now this,

now that; but nothing long,

|

I'm quite content, I do not care,

This world may wag for me;

When fuss an' fret wur o' my fare,

I geet no greawnd to see.

So, when away my carin' went

I ceawnted cost, an' wur content. |

And then, after another moment's silence, another fragment flitted

across his thoughts, and he trolled forth,

|

And she did laurel wear!

And she-e did laurel wear! |

Ben's voice rang loud and clear in that quiet scene, where the rich

repose of summer noontide seemed to steep every thing in drowsy

delight. Haymakers were at work upon the hill-sides, spreading

out the damp grass which had been cut before the previous day's

rain; and, now and then, a cheery laugh, or the cadence of some

snatch of old country song, came sailing on the sunny air, softened

by distance; but Ben had all the highway to himself, and the man and

his melody lent a charm to the landscape, as he wandered on,

chanting "like tipsy jollity that reels with tossing head."

The birds eyed him curiously from the trees as he went lounging by,

with the cosy sprig nodding in his hat at every footstep, and the

green branch swinging in his hand; and they seemed to listen

intently to his lay, till some dreamy pause of silent thought stole

in upon the fitful strain, and then they gushed forth into wilder

music than before, as if they had suddenly discovered an old friend,

and were delighted to find any human creature astir in the gay,

green world as happy as themselves.

He was approaching the head of the Clough called "The Thrutch,"

the most picturesque part of the road, and ten minutes' walk would

have brought him up to Healey Hall; but, though afraid of being too

late for his appointment with the colonel, he was too shy a man to

wish to be too soon in such an unusual place; and, therefore, he

began to linger, and look about for a place where he might rest and

cool himself during the intervening time. Seeing a bush of ripe "heps"

that overhung the pathway, he climbed the prickly hedge, and began

to pluck them, like a truant school-boy whiling away the sunny

hours, and as he put them, one by one, into his pocket, he sang,

|

An' still the burden o' my song,

Shall be, to great an' smo',

For hee and low, for weak an' strong,

Good government is o'! |

Here he suddenly leaped down from the hedge-side, and seating

himself upon the bank, he began to look at his hand, into which a

great thorn had penetrated; and, as he examined the bleeding finger,

he kept quietly repeating the last line,

Good government is o'!

over and over again, until, with the help of his pocket-knife blade,

he had extracted the thorn. Then, rising lazily to his feet again,

he sauntered on, and sang,

|

For I neverno, never,no, nev-er,

Shall see my love more!

. .

. .

.

Go from my window, love, go,

Go from my window, my dear,

The wind and the rain

Will drive you back again,

You cannot be lodgιd here.

Begone my fuggy, my puggy,

Begone my love, my dear;

The weather is warm,

'Twill do thee no harm,

Thou cannot be lodgιd here. |

Ben walked so near to the hedge-side, for the sake of the shade

afforded by the overhanging bushes, that his face came in contact

with a spider's web, fine as the down of a midge's wing. He halted,

and wiped away the ruins of the delicate rosace from his cheek; and

even this trifling incident seemed, unconsciously, to change the

tone and direction of his wandering fancy, for he burst forth with

an old ditty, of another tune:

|

Come, ye young men, come along,

With your music, dance, and song;

Bring your lasses in your hands,

For 'tis that which love commands;

Then to the Maypole hie away,

For it is now a holiday.

It is the sweetest of the year,

For the violets now appear:

Now the rose receives its birth,

And the primrose decks the earth

Come to the Maypole, come away,

For it is now a holiday.

Here each bachelor may choose

One that will not faith abuse;

Nor pay with coy disdain

Love that should be loved again;

Come to the Maypole, come away,

For it is now a holiday.

And when you well reckoned have

What kisses your sweethearts gave;

Take them back again, and more,

It will never make them poor.

Come to the Maypole, come away,

For it is now a holiday.

When you thus have spent the time,

Till the day be past its prime;

To your beds repair at night,

And dream there of your heart's delight.

Then to the Maypole hie away,

For it is now a holiday. |

Here, spying a well at a little distance, on the other side of the

road, he muttered to himself, "Hello, let's sup!" and away he went

lounging across towards it. Laying his hat on the green bank, he

knelt down upon the edge of the well; and, as he bent down to drink,

the reflection of his face rose up in the water to meet him. Ben

paused to contemplate the sight, and groping at his sore nose, which

still bore marks of the old fiddler's heel, he said, "Come, it does

look a bit better; but it's hardly fit to be sin yet. They'n be sure

to ax me abeawt it up at th' ho', yon. Well, I's be like to poo

through as weel as I con; for I connot go beawt it, that's sartin. It would do weel enough to go a-fuddlin' wi', but it's

noan fit for

a parlour. I wish I could wear eawr Betty's a day or two till this

gets mended. Hoo's a angel of a nose compar't wi' mine. Come,"

continued he, caressing it once more, "I'll poo tho through, owd

lad, as weel as I con." Then, seeing his holiday clothes, and the

posy in his button-hole, reflected in the water, he cried, "Hello,

Benjamin! what's up at you're so fine to-day? Yo're like th' better

side eawt! Are yo beawn to a weddin' or summat? I'll tell yo what,

maister, you're gettin' new things fast! Has somebry laft yo some

brass latly, or summat, at there's o' this fancy-wark agate? . . .

Posies an' o'! Eh, dear! There'll be no touchin' yo wi' a pike-fork

in a bit. . . . 'Ston fur!' said Simon o' Twitter's! 'Stone fur! I

never talk to poor folk when I've these clooas on! Ston fur! I'm

busy wi' th' quality. Co' to-morn, when th' brass is done! . .

.

Well, come, here's luck, owd lad!" And dipping his mouth into the

well, he took a long drink; then, rising slowly, and with half shut

eyes, he gave a sigh of satisfaction, wiped his mouth with his

napkin, brushed the dust carefully from his knees, donned his

rose-wreathed hat, re-arranged the posy in his button-hole, and

taking up the green branch, he lounged back to the shady side of

the road again, singing,

|

For I nev-er,no-o, nev-er,no, never,

Shall see my love more! |

"Nawe, nor I never shall," said Ben, with a sigh. "Eh,

hoo wur a

bonny lass, wur Jenny. God bless her! Eawr Betty's forgetten o' abeawt it, neaw. But

hoo use't to ding me up wi't a bit, sometimes,

when we wur cwortin'."

|

My lodging it is on the cold ground,

And oh, very hard is my fare;

But that which grieves me more, love,

Is the coldness of my dear.

Yet still he cried, "Oh turn, love,

I prythee, love, turn to me;

For thou art the only girl, love,

That art adored by me."

With a garland of straw I'll crown thee, love,

And marry thee with a rush-ring;

Thy frozen heart shall melt with love,

So merrily I will sing.

Yet still he cried, "Oh turn, love," &c.

But if thou will harden thy heart, love,

And be deaf to my pitiful moan,

Then I must endure the smart, love,

And shiver in straw all alone.

Yet still he cried, "Oh turn, love," &c. |

"Hello; what's comin' neaw!" said Ben, staring down the road. It was

a handsome, well-dressed, and well-mounted horseman, who came riding

hastily along. As soon as he had got within a few yards of Ben, he

pulled

up, and inquired how far he was from the village of Whitworth.

"Oh, three-quarters of a mile, happen," said Ben. "Th' first heawses

yo come'n to. Turn up at th' reet hond amung th' heawses, an' yon be

i'th midst on't, i' two minutes. I've just come fro' thither mysel."

"Do you think Dr. James will be at home?" inquired the rider,

"Sure to be," replied Ben. "He's seldom off, except when he's oather huntin' or shootin'; an' then he doesn't go far fro' whoam. Well, yigh; he twos into th' Red Lion a bit of a neet, after he's done."

"What kind of a place is the Red Lion?" inquired the horseman.

"Oh, the best shop i' Whit'orth, if yo wanten to put up. I know th'

folk 'at keeps it, very weel. Th' landlady's an owd friend o' my

wife's. I left my wife theer this forenoon. They'n a rare good

stable, too."

"Thank you!" said the rider, and flinging a shilling towards Ben,

he galloped off.

"Yon's moor money nor wit, I deawt," said Ben, looking after the

disappearing horseman. Then, walking up to where the shilling lay,

he looked down at it, and said, "Well, I never expected that, as

heaw. . . . He met

(might) ha' gan it one decently, beawt flingin' it o'th floor. . .

But it's no use lettin' it lie theer. It'll come in for summat

(somewhat) better nor mendin' th' hee-road wi'."

Then he pocketed the shilling, and went on singing, ―

|

Green grow the leaves on the hawthorn

tree;

Green grow the leaves on the hawthorn tree;

They hangle, an' they jangle,

An' they cannot well agree,

While the tenor o' my song goes merrilee.

Merrilee!

Merrilee-ee!

While the tenor o' my song goes merrilee! |

"I wish I'd axed yon chap what time it wur," said Ben. Then, after

walking thoughtfully on a few paces, he burst out again in a fresh

direction.

|

There wur an owd fellow coom o'er the

lea,

An' it's oh, I'll not have him!

He coom o'er the lea,

A-cwortin to me,

Wi' his owd gray beart new-shorn.

My mother hoo tow'd me to oppen him th' door.

An' it's oh, I'll not have him!

I oppen't him th' door,

An' he fell upo' th' floor,

Wi' his owd gray beart new-shorn.

My mother hoo bade me set him a stoo.

An' it's oh, I'll not have him

I set him a stoo,

An' he looked like a foo,

Wi' his owd gray beart new-shorn.

My mother hoo towed me to cut him some bread,

An' it's oh, I'll not have him

I cut him some bread,

An' threw't at his head,

An' his owd gray beart new-shorn.

My mother hoo towed me to leet him to bed.

An' it's oh, I'll not have him

I let him to bed,

An' he're very near deeod,

Wi' his owd gray beart new-shorn.

My mother hoo towed me to take him to church.

An' it's oh, I'll not have him!I

I took him to church,

An' I left him i'th lurch,

Wi' his owd gray beart new-shorn. |

When Ben had ended the ditty, he wiped the moisture from his

forehead again, and muttered to himself, "'Eh, it's warm, God bless

yo,' as th' owd woman said when they axed hur heaw hoo liked th'

thin broth. I wonder what o'clock it is. Hardly eleven, bith' day, I

think. Twelve's my time; an' I'll go noan afore, as heaw th' cat

jumps. I may no 'ceawnt o' bein' catechise't bi folk, quality or no

quality. Th' owd kurnul's sure to be theer, an' happen a parson or

two. I wish this nose o' mine wur reet; they're sich chaps for

readin' folk fro yed to fuut. . . . An' then, they're sure to begin

abeawt yon bit o'th jackass o' mine bein' round up into th' mill

chamber [Ed.― for this story, see

BESOM BEN AND HIS DONKEY]. Rare gam' for 'em, that'll be. It'll last my life-time,

that jackass dooment. Sarve me reet, too, leather-yed. I could ha' laugh't rarely if onybody else had done it but me. But th' laughin's

o' upo' one side, this time, like th' handle of a can. Ne'er mind;

it'll be somebry else's turn th' next. . . . Th' most o' folk are

fain to see other folk make fool's o' theirsels. It's th' way o'th

world. . . . An', by th' mon, if a poor lad happens to be born wi'

a hair-shorn lip, or his yure a bit cauve-lick't, he's sure to be

punce't for't, oather by one bowster-yed or another, though he's no

moor to do wi't nor he has wi' makin' moonleet. There's a decol o'

feaw flytin' i' this cote, that they co'n a world. . . . But then, I

wur a jumpt-up foo abeawt that jackass-do, there's no gettin' off

that. Well,come,I's happen larn sometime. It's a lung lone 'at's

never a turn. . . . But I's catch it, when I get to th' ho'. If it

isn't mention't o'th parlour, it'll be mention't i'th kitchen. Th'

sarvants are ten times war nor th' tother. But, never mind, every mon

mun do his do, while th' time's up. Come on!' said Kempy; 'we're noan freeten't o' frogs! Folk 'at's boggart-fear't

han nobbut a feaw

life.' 'Forrad, lads!' cried Tickle-but; 'yo'r wark's i'th front on

yo!'. . . . I'll face up at twelve, but not a minute afore, that's sattle't. An' there's an hour to do on, yet. Come, I'll keawer me deawn, an'

pike a two-thre o' these heps."

Taking a few of the red hips from his pocket, he was just preparing

to seat himself upon the hedge, when, glancing along the road, he

spied somebody sitting in a shady place, close by the wayside.

"Hello," said Ben; "what's yon? Somebry sittin' bi th' roadside,

as snug as a button, wi' o'th world to theirsel'. I wonder who it

is. A tramp o' some mak, I dar say. Come, I'll have a look at 'em,

as heaw." And away he went lazily onward, chanting,

|

Han yo sin my love, my love, my love;

Han yo sin my love, lookin' for me?

A cock't hat, an' a fither, an' buckskin breeches

An a bonny breet buckle at oather knee. |

As Ben drew nearer, he began to recognise some features of the

person he had seen from the distance, and, stopping suddenly, his

eyes began to glisten, and, raising his hands, he cried, "By th'

mass; I believe it's Dan o' Tootler's, th' owd fiddler! Eh, if it's

him! Come, that'll do!" And then he strode forward more briskly,

singing,

|

Robin Lilter's here again

Here again, here again?

Robin Lilter's here again,

Wi' th' merry bit o' timber. |

It was, indeed, Dan o' Tootler's, a blind fiddler, well known all

over the country side. His native spot was a wild moorland fold,

near to the foot of Brown Wardle Hill, at the north-eastern end of

the vale of the Roch; but he was a great wanderer; and his wide

acquaintance with old melodies, especially those peculiar to the

north of England, as well as his remarkable power as a performer

upon the violin, made him a favourite guest wherever he went. At

wakes, and weddings, and churn-suppers, or any country holiday, his

was a well-known and welcome face, in every country nook between

Blackstone Edge and the bleak ridge of Rooley Moor; and even far

beyond that great dividing line, in the hills and dales of

Rossendale Forest, and amongst the lonely folds of Ribblesdale, up

to the great end of Pendle, many a merry heart leaped with joy at

the mention of blind Dan o' Tootler's, and his fiddle. There the

minstrel sat, upon an old tree root, which had been left by the

wayside, sunning himself, and crooning a quaint tune, with his blind

eyes turned upward to the summer sky. He was called "Owd Dan"

wherever he went; but this was meant more as an acknowledgment of

kindly acquaintance than as indicating the decrepitude of age; for

he was not yet sixty, and he was a happy-hearted and remarkably hale

man for his years. He was humbly clad, but all was clean and whole

from head to toe; and even the clumsy, unconcealed patches upon his

clothing, here and there, were indicative of wholesome thrift, and

showed that, though poor, he was not severely so, and also that, in

his lowly estate, he was kindly cared for. His son, a chubby lad of

nine years old, whose business was to lead him by the hand, had

wandered into a field, hard by, to gather flowers, always keeping

within call, whilst the old man rested himself; and as the blind

fiddler sat there, with his face up-turned, and quietly swaying his

body to and fro, to the measure of an old tune, which he was

crooning dreamily to himself, there was something very touching in

the placid helplessness which pervaded his well-cut features. Indeed, there is often a strange heaven of peaceful expression in a

blind man's face; as if the loss of sight, which deprives life of so

many pleasures, had taken away also some of its troubles; and the

mute, pleading eloquence, the plaintive quietude that dwells in a

sightless countenance, moves the heart more than strength, more than

beauty ever can; as if helplessness itself was surrounded by an

angelic atmosphere, more potent for its defence than any merely

physical protection could be.

The fiddler was on his way to the house of an old friend, who farmed

a large tract of land upon the edge of the moors, near the town of

Bacup. Indeed, the minstrel and the farmer were distant relatives,

bearing the same name, apart from the personal attachment which

bound them to each other; and, according to a custom long

established between the two, the fiddler had been specially invited,

quite as much in the character of a guest as of an itinerant

musician, to enliven the rustic gathering which thronged the old

house at the Nine Oaks' Farm at the annual churn-supper, as the

feast of the hay-harvest is called in South Lancashire. The

churn-supper at Nine Oaks was famous all over the Forest of

Rossendale, no less on account of the number of the guests and the

bounty of the cheer, than on account of the presence of a minstrel

so well known and so universally welcome as Dan o' Tootler's was in

those days. He had already walked many a rough moorland mile, and,

having still several miles further to go, the old man had sat

himself down in this shady nook of the road to rest a little while. The loss of sight had made the fiddler's hearing more acute than is

common to those whose senses are all in full play; and in the

all-pervading stillness of the scene, where nothing seemed astir but

the songs of wild birds, his quick ear caught the sounds of Ben's

footsteps approaching from the distance.

"Husht!" said he, as if talking to the birds around him;? "husht!

there's somebry comin'!" Then, catching the tones of Ben's voice as he

came singing on, a quiet smile crept over the old man's up-turned

face, as he rubbed his hands and said, "Come, I know who that is! .

. . Husht! Let him goo on again! . . . Ay; it's him. Lobden Ben,

for a creawn!" As Ben drew near, the fiddler cried out, with his

smiling countenance still turned sunward, "Hello, Ben, owd lad! Is

that thee? Heaw arto gettin' on amung yon yirth-bobs (tufts of

heather) upo' Lobden Moor?"

"Eh, Dan o' Tootler's, owd dog!" cried Ben, running up, and catching

the fiddler by the hand. "God bless thy owd tweedlin' soul! Wheerever arto wanderin to, wi' thoose bonny bits o' cat-bant o'

thine?"

"Oh, a bit fur up, Rossenda' gate on," replied the fiddler. "I'm beawn to a churn-supper, at th' Nine Oaks."

"Th' dule theaw art!" cried Ben. "Eh, thae will tickle yon owd

clinkert shoon o' theirs up, aboon a bit! By th' maskins, I wish I're beawn witho', owd brid!"

"An', by the good Katty, I wish thae wur, owd crayter!" replied the

fiddler. "But I'm i' good time, yet. Come, keawer tho deawn a bit."

"I'm i' good time, too," answered Ben. "I've aboon an hour o' mi

honds."

"Well; come thi ways, an' have a keawer, then," continued the

fiddler, shifting, to make room for Ben upon the old tree root. "Keawer

tho deawn. Th' moon's had mony a reawnd sin I let on tho afore. An' wheer arto for when tho sets off again, like, conto tell? Or, thae'rt like wayter in a bruck, noan tickle if thae can keep gooin'."

"Yelley Ho's (Healey Hall) th' first shop I have to play for, as

soon as th' time comes," replied Ben.

"What, owd Kurnul (Colonel) Cherrick's?" said the fiddler.

"Ay."

"Why, thae'rt noan so fur off theer, now, arto?" replied the

fiddler.

"I can year th' dogs barkin' i'th yard, fro' here," answered Ben.

"Come, that'll do!" said old Dan, rubbing his hands; "that'll do!"

"He wants me to goo up to th' top o' Blacks'n Edge wi' him an' some

friends of his, this afternoon," continued Ben.

"Oh, ay!" replied the fiddler. "There'll be find doin's thae'll see. He's a rare owd cock, is th' kurnul.

Yo'n be nought short, if he's

theer. But yo'n be pinch't for time, winnot yo? I'd ha' started i'th

mornin'."

"Well, thae knows," replied Ben, "I go bi orders. Twelve o' clock's

my time; an' I's go noan afore."

"Shootin', I guess?" inquired the

fiddler.

"Nay; I know nought what they're after," answered Ben. "It's reet to

me, as what it is; though I like to see a bit o' good spwort, for o'

that. But twelve o' clock's my time an' it wants an hour yet."

"Well, then," said the fiddler, "thae'rt i' no peighl. So come an'

sit tho deawn, an' let's have a bit o' talk. I'll be sunken if I'm

not gooin' meawldy for th' want o' somebry to fratch wi'! Come an'

sit tho deawn."

"I'm willin'," said Ben, giving the old man a friendly slap on the

shoulder, as he sat down beside him on the tree root. "Hutch up a

bit. Well, an' heaw arto gettin' on, Dan, owd lad?"

"Oh, peeort (pert), lad; peeort as a pynot (a magpie)," replied the

old fiddler, smiling.

"That's reet," said Ben, "I like to yer o' folk doin' weel,

particilar fiddlers, ― they'n so mich fancy-wark abeawt 'em.

|

A mon 'at plays a fiddle weel,

Should never awse (attempt) to dee, |

I'll tell tho what, Dan!"

"Well."

"It's a fine day, an' we'n plenty o' time on er honds, an' it's a

good while sin we let o' one another afore; an' there isn't a wick

soul i'th seet nobbut thee an' me."

"Well; an' what bi that?"

"Why, thae met trate a body to a bit of a do upo' that friskin'-stick

o' thine. Come, strike up!"

"Well," replied Dan, drawing his fiddle from the

bag; "I've nought again that noather."

"Good again! " cried Ben. "What arto beawn to give us, owd

brid?"

"Aught 'at ever thae's a mind, Ben," answered the fiddler, as he

rosined his bow.

"Well, let's have a good owd minor, then," said Ben.

"Agreed on,"

replied the fiddler. "But I'll tell tho what, Ben."

"Well."

"I'm just thinkin' 'at I could like to yer thee tootle one o' thoose

bits o' ditties o' thine, th' first."

"So be it, then," said Ben. "What's it to be?"

"Try 'Chad'ick o'

Chadick Ho'!"'

"I don't know it through," said Ben.

"Let's ha' 'Fair Ellen o' Ratcliffe,' then," continued the fiddler.

"Oh, it's so lung," replied Ben. "Thea'll have us agate o' yeawlin'

till mornin'."

"Well," said the fiddler, "sing 'Bowd Byron an' his men,' then; or

else 'Iron Cap o' Bernshaw Tower.'"

"Oh, I couldn't get through 'em i' time, mon," replied Ben. "I could

happen manage Tuttlin' Tummy,' or 'Skudler o' Buckstones,' or 'Th'

Piper o' Wardle.'"

"Doesto know 'Thungin' Robin?'" inquired the fiddler.

"Nawe."

"Or, 'Dark Rondle o' Sceawt Scar,"' continued the fiddler.

"I don't know that, noather," replied Ben.

"Well 'Cowd Simeon,' then," continued old Dan.

"Eh, nawe," said Ben. "It's to hee, it's to hee! By th'

mon, Dan,

where I know one thae knows twenty."

"Well, I'll tell tho what," said Dan; "try 'The Flowers o' Joy.' That's short enough; an' a bonny thing too."

|

Full oft the sweetest flowers of joy.

From the soil of sorrow spring. |

"Here, here," said Ben, doffing his hat, and stroking his hair

aside. "I'll try one."

"Well, get agate," said Dan, beginning to tweedle on his fiddle. "Get agate, an' I'll put an odd note or two in as thae gwos on. Eh,

Ben, I wish I could sing like thee!

|

Bowd Buckley o'er the wild hills rode,

A darin' dance to tread;

Wi' twenty-four o'th starkest lads

That ever Rachda' bred. |

Come, get agate, Ben; or else I'll start mysel'."

The fiddler's little lad, hearing the noise, had come out from the

field, with his hand full of posies; and he was now standing by his

father's side, holding the lap of his coat, and gazing at Ben with

wondering eyes.

"Come, Ben; what is it?" said the fiddler.

"'The girl I left behind me,'" replied Ben.

"Brast off, then," replied the fiddler.

|

I'm onely since I crossed the hill,

An' o'er th' moor an' valley;

Such heavy thoughts my heart do fill

Since partin' wi' my Sally.

I seek no more the fine an' gay,

For they do but remind me

How swift the hours did pass away

With the girl I left behind me.

Oh! ne'er shall I forget the night, ―

The stars were bright above me,

An' gently lent their silver light,

When first she vow's to love me.

But now I'm bound unto the camp,

I pray that heaven may guide me,

An' send me safely back again

To the girl I left behind me.

Had I the art to sing her praise,

With all the skill of Homer,

One theme alone should fill my lays,

The charms of my true lover.

Then, let the night be e'er so dark,

Or e'er so wet an' windy,

I pray kind heaven may send me back

To the girl I've left behind me.

Her golden hair in ringlets fair,

Her eyes like diamonds shining,

Her slender waist, her carriage chaste,

May leave the swain repining.

Ye gods above! oh, hear my prayer,

To my true love to bind me,

And send me safely back again

To the girl I've left behind me.

The bee shall honey taste no more,

The dove become a ranger,

The rolling waves shall cease to roar,

Ere I shall seek to change her.

The vows we've register'd above

Shall ever cheer and bind me,

In constancy to her I love, ―

The girl I've left behind me.

My mind for her shall still retain,

In sleeping or in waking,

Until I see my love again,

For whom my heart is breaking.

If ever I return that way,

And she should not decline me,

How gladly will I live and stay

With the girl I've left behind me. |

"Weel chanted, owd lad!" cried the fiddler, slapping Ben on the back

heartily. "Weel chanted. It's a bonny owd thing, to this day. An',

eh, I'll tell tho what, Ben, there's many a poor sodiur lad has sung

that wi' a achin' heart when he's bin far away fro' whoam, an'

little chance o' comin' back again."

"Eh, ay," replied Ben; "I know summate abeawt that. Eawr Bill wur

kilt at th' stormin' o' Badajos. Thae knows Moses Whistler, th'

white-limer?"

"Sure, I do."

"Well, eawr Bill an' him listed together," said Ben.

"Oh, ay?" said the fiddler.

"Ay," continued Ben, looking thoughtfully round. "Moses has getten

whoam again, lam't for life; but eawr Bill, poor lad, he's lyin'

somewheer abeawt Badajos, quiet enough, what there is laft on him."

"Well," replied the fiddler, "my young'st brother, eawr Joe, a finer

lad, nor a better-hearted, never steps shoe-leather, he deed, wi'

Nelson, at Trafalgar. Eh, I thought my mother would ha' brokken her

heart! He're like th' nestle-cock at eawr heawse. . . . I

don't know heaw it wur, but he would be a sailor, lung afore he'd ever set een

upo' salt wayter. . . . Poor Joe!"

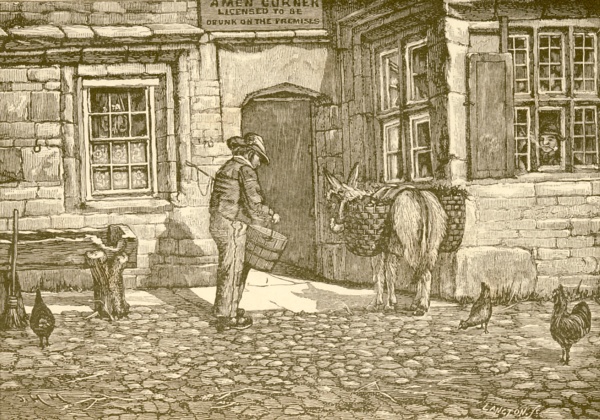

"AMEN CORNER,"

ROCHDALE.

"Ay, it's so, sometimes, for sure," said Ben, in a dreamy tone. "Th'

last time 'at I yerd 'Th' Girl I left behind me' wur at 'Th' Amen

Corner,' i' Rachda'. It wur one o'th leet horse, a fine yung chap as

ever I claps een on. He'd come upo' furlough, a-seein' his

relations; an' when he geet to Rachda' he fund 'em o' laid by i'th

churchyard, th' owd sweetheart an' o'. An' th' lad look't

lost, quite lost, as he sit theer i'th nook bi hissel', as still as

a meawse. But nought 'ud fit these tother but he mut (must) tak' his

turn, an' sing 'Th' Girl I left behind me.' Well, I tell tho, he

tried, an' I never yerd it better sung sin I're born o' mi mother. But when he'd getten abeawt th' hauve gate through, he brasts eawr

a-cryin', an', by th' mon, he sets us o' agate, th' drunkenest foo' i'th hole, they're o' cryin' at once. There weren't a dry face i'th

spot. Owd Bill Hollan', th' butcher, wur sheer, but he couldn't

ston it. He had to goo eawt. Eh, heaw that lad did cry! . . . But,

come, let's drop it, for God's sake. . . . Here, it's thy turn, Dan. Strike up summate or another."

"Agreed on," said the fiddler, drawing his sleeve across his eyes,

and then shouldering his instrument. "Agreed on; what mun us have?"

Try 'Remember the Poor,'" said Ben.

"Well done, Ben!" said the fiddler. "That's a fine owd minor tune!"

"It's nought else," replied Ben. "Brast off!"

The old man began to arrange the pegs of the instrument, and, as he

tried the strings, one after another, and then in unison, he

muttered affectionately to his fiddle, as if it was a living thing.

"Neaw, owd lad," said he, as he screwed first one peg,

then another, and tweedled over little fits of wailing prelude, to

get the tones he wanted. "Neaw, owd lad, this is a nice job

for tho. Just thee talk to 'em a bit, i'th owd fashion.

Thae can do it if thae's a mind, I know. We'n had mony a happy

day together, thee an' me, hadn't we, owd brid? Ay,

an' we'n ha' mony another, if God spares er lives. . . . Neaw, mind

thi hits! . . . 'Remember the Poor,' thae says, Ben?"

"Well, wean see what we can do," continued the fiddler.

Then he quietly began the plaintive old forest tune, and, as the

beautiful wail rose upon the air, it seemed to hush the wild birds

around, and fill the summer noontide with a sweet sadness. The

rindle of water, dribbling into the well hard by, subdued its

silvery tinkle, and the very trees and hedges seemed to stand still

and listen, as if spellbound by the old man's touching lay.

Ben was so moved that he could not help taking up the melting

strain, and so they played and sang the tender old ditty together,

till tears began to trickle down their cheeks; and when the song was

ended, and the last soft cadence was dying out upon the woods in the

clough, they sat silent together for a minute or two.

CHAPTER II.

|

Oft seated 'neath some spreading oak,

To rapturous strains his soul awoke;

Whilst ii,tening hinds would drop the spade

Forgetful of their hardy trade;

And peeping maidens raised the latch,

The minstrel's melting lay to catch;

And the lone brook that crept along,

Bore on its breast the fiddler's song.

THE

LAY OF THE POOR

FIDDLER. |

"THAT'S a nice

thing," said Ben, drawing the sleeve of his coat across his eyes.

"Ay, it is" replied the old fiddler. "Gi' me thi hont,

Ben; I con play for thee wi' some'at like comfort. But, eh,

mon, it hurts me, it hurts me to play for folk at's no feelin'.

There's nobry knows nought abeawt music if they hadn't a heart i'

their inside. But, th' most o' folk, neaw-a-days, are like as

if they'd bin made eawt o' button-tops an' scaplins, put together

cowd. . . . But, gi me thi hont, Ben, lad! Thae knows what

things belungs."

And they shook hands together, whilst the tears stood

gleaming in the old fiddler's blind eyes.

The little lad was still standing by his father's side,

gazing, wonderingly, first at one, then at the other.

"Billy," said the fiddler, "go thi ways an play tho i'th

feels again a bit. I'll shout when I want tho."

.

.

.

.

"Dan,' said Ben, groping in his pocket, "hasto had ony

dinner?"

"Nawe," replied the fiddler, "but eawr Billy has a bit in a

hankitcher somewheer."

"Wilto have a bit o' mine?" continued Ben.

"What hasto getten?" inquired the fiddler.

"Green-sauce-cake an' cheese," replied Ben.

"Ay, an' good, too," answered the fiddler. "Come, I'll

have a bite wi' tho."

.

.

.

.

"Ben," said the old man, "hasto sin 'Duck-fuut' lately?"

"What, Tummy o' Doddle's?"

"Ay," replied Dan. "They co'n him 'Duck-fuut,' for a

bye-name, dunnot they?"

"I thought his bye-name had bin 'Whelp,'" said Ben.

"Well," replied the fiddler, "I've yerd him co'd both 'Whelp'

an' Duck-fuut.' It's thoose 'at doesn't like him at co's him

'Whelp,' I dar say."

"Well, but," continued Ben, "it's same chap that I meeon.

It's lung Tummy, th' ceawnter singer, isn't it?"

"Sure it is," replied the fiddler.

"Eh, I connot tell when I seed him last," said Ben. "I

believe it wur one Sunday forenoon, up at Ash'oth Chapel, soon after

Kesmass. An' what dost think he did?"

"Nay, I know not," replied the fiddler. "Some'at quare,

for a creawn."

"Well, thae knows, they'd no organ up at Ash'oth Chapel;

they'n nought nobbut th' singers, an' a bass fiddle, an' a little

fiddle, an' a piccolo, an' sometimes a bazzoon, that's when Billy

Diggle's th' solid side eawt. Tim o' Yeawler's plays th' bass

fiddle. Well, that forenoon, owd Nobbler, th' clark, ga' th'

hymn eawt, 'Let us sing to the praise and glory of God, th'

fourteent' hymn.' Then there wur a deeod stop for a minute or

two, an' folk wur wonderin' that th' singers didn't start o' their

wark. An' just as they began o' turnin' reawnd to see what wur

to do, up rose 'Duck-fuut,' two yards hee, i'th singin' pew,

sich a seet! He'd a thick red wool muffatee reawnd his neck;

an' he'd two o'th primest black een i'th front of his face 'at ever

thae seed, for he'd bin to a fuut-bo' match, th' day afore, an' it

had finish's up wi' a battle. Well, up that figure rose i'th

singin' pew, six fuut o'th quarest-lookin' stuff 'at ever stoode i'

that spot, an' he sheawted deawn to th' clark, 'Heigh, Bobby!

doesto yer?' Owd Bob happen't to be blowin' his nose at th'

time, an' didn't just catch him, so 'Duck-fuut' sang eawt again, 'Doesto

yer, Nobbler?' Th' owd clark jumps, an' drops his hankitcher,

when he yerd that word Nobbler,' an' he stare't at th' singin' pew,

an' said, 'What's up?' 'Well,' cried 'Duck-fuut,' lookin'

deawn at him, 'you mun stop a minute or two; owd Tum's brokken a

streng. Sit yo still a bit. I'll gi' yo th' item when

we're ready."

"Just favvours him!" said the fiddler.

"A bit like him, for sure," said Ben. "But he geet th'

bag for that."

"Sarve him reet," replied the fiddler. "But he never

wur very breet. I can remember 'em tellin' on him gooin' to

Rachda' rushbearin' when he wur a little lad, an' he happened to see

a chap i'th street playin' a trombone. He'd never sin a

trombone player in his life afore, so he stood a while, watchin'

this chap play. At th' last he turn't to his faither, an' he

said, 'See yo, faither, at yon chap 'at's playin' yon brass thing;

he connot get it th' reet length, as what he does.'"

"By th' mon," said Ben, "he's as ill as owd Nukkin, 'at went

up Knowe Hill a-meetin' a sheawer o' rain."

"I yerd on him bein' at a rent-supper, once," continued the

fiddler, "an' when th' supper wur o'er, th' cheermon code for

'order!' An' when he'd getten 'em still, he said, 'There is no

parson here, is there?' 'Nawe.' 'Well; I could like to

yer some on yo say 'Grace,' after sich a supper as we'n had to-neet.

Here, Duck-fuut, thee try thi hond, thae'rt a church-singer.'

Then up jumped 'Duck-fuut' in a minute, an' he cried eawt, 'Thank

God 'at there's nobry brawsen.'"

Here Ben began to feel a little compunction, remembering how

often he had laid himself open to ridicule. And, wondering

within himself whether the old man had heard of his foolish freak

with the jackass, which was now the talk of the whole country-side,

he silently determined to seize the opportunity of turning the

conversation into a different direction.

"Dan," said Ben, "I've a good mind to gi' tho another bit of

a ditty."

"Do, Ben, do, God bless tho!" said the old man, shouldering

his fiddle once more.

"Here goes!" said Ben,

|

The day was spent, the moon shone bright,

The village clock struck eight,

Young Mary hastened with delight,

Unto the garden gate.

But what was there that made her sad?

The gate was there but not the lad;

Which made poor Mary say and sigh,

"Was ever poor girl so sad as I?"

She traced the garden here and there,

The village clock struck nine,

Which made poor Mary sigh, and say,

"You shan't, you shan't be mine.

You promised to meet me at the gate at eight,

You never shall keep me nor make me wait;

For I'll let all such creatures see,

They never shall make a fool of me!"

She traced the garden here and there,

The village clock struck ten;

Young William caught her in his arms,

No more to part again

For he'd been to buy the ring that day,

And O! he had been a long, long way;

Then, how could Mary so cruel prove,

To banish the lad she so clear did love?

Up with the morning sun they rose,

To the church they went away,

And all the village joyful were,

Upon the wedding-day.

Now, in a cot, by a river side,

William and Mary both reside;

And she blesses the night that she did wait

For her absent swain at the garden gate. |

"Bravo, Ben!" cried the fiddler. "Thae mends!

|

Bravo, bravo, very well sung,

Jolly companions, every one! |

He then quickly began to play the air of the quaint old

country song,

|

My owd wife, hoo's a good owd crayter;

My owd wife, hoo's a good owd soul! |

But before he had quite drawn out the last note of the second bar,

Ben laid his hand upon his shoulder and said, "Dan, owd lad, we'n

o'th world to ersels (ourselves), yet. There isn't a wick soul

i'th seet. Let's have a doance! These toes o' mine are

ram-jam full o' flutterment! Strike up 'The Flowers of

Edinburgh,' or else 'The Devil Rove his Shirt!' There's a bit

o' nice hard greawnd i'th front on tho here, 'at looks as if it'd

bide thumpin'. Strike up, owd brid! 'The Flowers of

Edinburgh.' I'll fuut it! Just thee hearken my feet,

neaw! Brast off! There's nobry comin'."

"Howd!" said Dan. "Howd a minute, till I get my strengs

reet!"

Then he twisted and tweedled a minute or two, and when he had

got his instrument into tune, he tapped upon the back of it with his

fiddle-stick.

"Nae then, Ben," said he, "arto ready?"

"Crash off! " replied Ben.

And at it they went, ding-dong.

Ben, though unusually strong-built for his height was a

lithe-footed, and, what is called in the country, a "lark-heeled

lad," a good runner, and a capital dancer of the dances common to

his own country-side.

The fiddler's quick ear followed Ben's footsteps with glee.

"Go it, my lad!" cried he. "Go it, Ben, owd dog!

Weel fuuted! By th' mon, weel fuuted! Rare time, Ben,

owd brid, rare time! Welt at it! Theighur! By th'

mass, thae'rt makin' that bit o' floor talk like a Christian!

Capital races! . . . Go thi ways, Ben, my lad! Dee when tho

will, thae'rt a glitterin' jewel!"

There they were, "with all the world to themselves," Ben

dancing in the sun, with the posies in his hat nodding to the tune;

and the blithe old fiddler, with his smiling face upturned, frisking

his gleeful elbow, and his whole body moving restlessly to the beat

of the dancer's feet, whilst the fiddler's lad, with his hands full

of wild flowers, leaned through a gap in the hedge, gazing upon the

scene with mingled astonishment and delight.

"Stop! stop!" cried the fiddler, ending the tune with a soft

wailing cadence. "Stop, an' rosin! Tak thi woint, Ben.

Thae's done weel this time reawnd. Eh, if thou'd had a

brewheawse-dur or summat to caper on, it would ha' made it sing!

Come, sit tho deawn, owd lad!"

"It's warm wark, Dan," said Ben, wiping his forehead.

"I wish we'd summat to sup. I'm as dry as soot."

"Eh," said the fiddler, " I wish thae'd a quart o'th best ale

'at ever wur brewed i' this world, o'th front on tho just neaw, fair

singin' for tho to seawk at it! God bless thi heart!

Thae's a fuut like a angel, Ben, an', by th' mon, thae'rt as lennock

as a snig! Gi' me thi hont! That bit o'th heart o' thine

followed th' music, or else thae could ne'er ha' stricken sich time

as that! Thae can doance both leet an' shade, owd brid!

It does my heart good to yen a doancer touch th' tender bits of a

tune with a soft fuut! Oh, it maes me feel as fain as a cat in

a tripe shop! Come, an' sit tho deawn upo' this tree-root.

Eh, it would ha' eawnded weel if it had bin a wood floor!

Let's stop an' rosin. Gi' me thi hont, lad! . . . I'll tell

tho what, Ben, thou's some music in thou,' as owd Swatter said when

th' jackass eat his tune-book. Thou has, owd lad! 'God

bless thoose hoofs o' thine!' as Tuner said when th' lon'lort

brought him two keaw-heels to his supper. Come, sit tho dawn.

By th' mon, that's warmed me up!"

"Ay, an' it's warmed me up, too, primly," replied Ben, taking

his seat by the side of the old man.

It is a remarkable thing, that blind people, even those

that have been born blind, often speak of the appearance of

persons, and places, and things, as if they had actually seen them.

Whether this is merely an imitative manner of speech in their case,

or it may be accounted for by the unusual acuteness of the senses

still left to them, and the keener attention to the reports of those

who can see, aided by the shaping power of imagination, which must

be greatly stimulated by the loss of sight, it is not easy to

decide. But the result is often so. And so it was with

old Dan, the fiddler.

"An' wheer is it 'at you're off to this afternoon, Ben?" said

the old man.

"Top o' Blacks'n Edge," replied Ben.

"Well, yo couldn't have a nicer day for th' job," said the

fiddler. . . "I guess thae never wur i' Turvin Cloof, Ben?"

"Never. I know nought mich abeawt that countryside,"

answered Ben.

"Eh, it's one o'th wildest nooks 'at ever I set een on,"

replied the fiddler. "I know o' that country-side, deawn as

far as Ripponden, hill an' dale, wood an' wayter-stid, hamil

(hamlet), an' roadside heawse. . . . Yo'n co' at th' White House,

at' top o'th Edge, I guess?"

"I dar say we sha'n," replied Ben. "There is nowheer

else to co' at up theer."

"Nawe, there isn't," said the fiddler. "It's a wild

country up theer, for sure. I've bin frost-bitten mony a time

crossin' thoose tops. . . . Hasto ever bin to Robin Hood Bed?"

"Oh, ay," replied Ben, "three or four times. It's a

fine lump o' rock, is that."

"Ay, it is," said the fiddler. "It stops upo' th' edge

o'th moor-side, as if it own't everything within seet, an' that's no

little."

"Nawe, by th' mon, it isn't so," answered Ben. "They

can see across Lancashire an' Cheshire into Wales, fro' th' top o'

Robin Hood Bed."

"Ay, they con," said the fiddler. "Let's see, I guess

thae wouldn't know th' owd folk 'at kept th' White Heawse afore Joe

Faulkner went to't."

"Nawe," replied Ben, "that wur afore my time."

"Eh,' continued the fiddler, "I once yerd a bit of a tale at

th' White Heawse. But heaw arto for time, Ben?"

"Oh, I've aboon hauve an heawer yet," replied Ben.

"Come, that'll do," said the fiddler. "This tale'll

just do to put a two-thre minutes on, while we're restin' us. . . It

wur one afternoon, i'th depth o' winter,―――

But perhaps the old fiddler's story had better begin another

chapter.

CHAPTER III.

|

How she did wish, with useless tears,

To have again about her ears

The voices that were gone.

WILLIAM

BARNES. |

|

Her lonely heart was breaking,

And crazed was her mind;

She sighed, and wandered, seeking

A face she could not find.

ANON. |

IT wur i'th depth

o' winter, an' th' snow lee thick upo' th' greawnd. This lad

o' mine an' me, we'd bin deawn at Mytholmroyd; an' late on i'th

afternoon, we set off up through Turvin Cloof, to get to th' White

Heawse, at th' top o' Blacks'n Edge. An' a wild an' lonely

cloof it is, partickilir i' winter time. Th' road wur terrible

dree, an' hard to travel; for it wur rough, an' sometimes very

steep; an' here an' theer, wheer rindles o' wayter had run o'er it

fro' th' hill side, th' keen frost had made it as slippy as a lookin'-glass.

It wur as mich as I could do to keep my feet; an' thae may depend we

didn't get forrud so very fast. I wur fain to sit me deawn

neaw an' then, an' eawr Billy started o' cryin', for th' lad

thought we're lost, an' done for, sure enough, when it geet th'

edge o' dark, an' nought but th' wild cloof abeawt us; and it made

me rayther for-think (regret) ever settin' beawt. But I

cheert't him as weel as I could; for, thae knows, th' lad wur o'

that I had to depend on. Well, we geet forrud o' someheaw, bit

by bit, but dark overtook us lung afore we geet to th' top end o'th

cloof, an' we'd o' th' wild oppen moor-side to tramp at after, afore

we coom to th' White Heawse, at th' top o'th Edge. An' th'

wynt blew so keen that it welly (well-nigh) flayed (fleeced, strips)

th' skin off my face; an' eawr Billy cried, poor lad, he cried,

but I believe he cried moor because he wur freetent o' me foin',

than he did for hissel'; for every time that I slipt, or gav' a bit

of a clunter again a stone, he brast eawt again, as if his heart wur

breighkin. An' he tremble't fro yed to fuut, an' he kept

tellin me to tak care, an he gript my hond, as tight as deeoth.

An' he'd a hard job, had th' lad, that day; for, bi what he said, bi

th' time we geet to oppen moor-side it had getten as dark as a fox's

meawth, an' he could hardly see th' gate afore us. But eawr

Billy's made o' good stuff, God bless him! an' I don't know what

I could do beawt him. . . .

Well, at th' lung-length we geet to th' White Heawse, fair

stagged up, an' as starved as otters, for th' north wynt blew as

keen across that hill as if it had bin full o' razors. I wur

some fain for us to creep into shelter, I con tell tho. But,

afore many minutes wur o'er, eawr Billy an' me wur comfortably

keawert (cowered, seated) bi a roarin' fire i'th kitchen, chatterin'

together as if we'd live't among roses, an' etten nought but lamb

an' sallet, ever sin we were born. An' th' londord an' his

wife wur as good as goose-skins to us. They're two very

daycent folk, I con tell tho. Th' owd lass, hoo set us a rare

baggin' beawt afore we'd bin mony minutes i'th heawse, an' we fell

to't wi' good heart, thae may depend. . . . An' th' woint went

whistlin' an' yeawlin' reawnd that heawse as if o'th witches between

theer an' th' big end o' Pendle had bin frozen eawt o' their holes,

an' wur ridin' reawnd upo' th' storm, like a boggart-hunt i'th air.

I yerd it o'th time; for, thae knows, I've a keen ear for sich like

things. But theer we wur, snugly heawse't for th' neet; for

they wouldn't yer on us goon' a fuut fur, till mornin'; an' to tell

tho th' truth, I wur fain on't. . . .

There wur five or six moor i'th kitchen, a gam-keeper, an'

two delph-chaps, an' three or four moor, 'at looked like hawkers;

they'd bin deawn Ripponden Road on, an' they'd dropt in, one after

another, as they'rn makin' th' best o' their gate whoam again; an',

in a bit, we wur as thick as if we'd every one bin mates together

fro' chylt-little (child-little). An' nought would suit these

chaps but I mut (must) give 'em a touch upo' th' fiddle. So I

played, first one thing, then another, an' we'rn o' as comfortable

as crickets, nobbut one on 'em, he'd rayther a three-nook't mak

of a temper. But I took no notice on him, for he'd had to mich

to drink upo' th' road, afore he geet to 'th White Heawse. . . .

Bi this time, th' moon wur up; but th' sky war o'erkest

(over-cast), an' thick snow wur drivin', white an' wild, across th'

top o' th' Edge. . . .

Well, I're agate o' playin' 'Roslin Castle,' an' th' folk

i'th kitchen wur as whist as mice, for they seam't a bit taen wi'

th' tune; an' weel they met (might), for it's as bonny a minor as

ever tremble't fro' fiddle-streng. . . .

Well, I wur up to th' eon i' this fine owd tune, an' th'

heawse wur as still as a chapel, when o' at once, we wur startle't

wi' aclatterin' o' feet eawtside, an' then th' dur flew open, an' a

chap coom runnin' into th' kitchen, o' in a cowd sweat, wi' a face

as white as millk, an' shakin' till his teeth fair chatter't i' his

yed. 'God bless us o'!' cried th' lon'lady, 'whatever's th'

matter!' But th' chap wur clean done up, an' he thrut (threw)

hissel' into a cheer, an' theer he sit, speechless an' pantin' an'

tremblin' fro' yed to fuut, like a hunted hare. O' th' heawse

wuar terrified, for they could noather make top nor tail on him an'

they thought th' felly (fellow) wur deein.

In a bit he gasped eawt for 'em to let him sup o' wayter, an,

he said that he'd 'sin summat.' Well, when this drunken hawker

yerd him say that, he began a-laughin', an' makin' o' maks o' gam on

him; but these two keepers soon stopped him, for they

threaten't mich an' moor that if he didn't howd his din they'd throw

him eawt at th' dur-hole; so he kept his tongue between his teeth,

like a good lad. . . .

Well, as soon as this chap had getten reawnd, he set to, an,

towd his tale. . . .

It seemed that he'd bin to th' owd hamil (hamlet) o' Sawrby (Sowerby),

a-seein' an uncle of his that wur just at th last; an he'd stopt

theer, bi th' bed-side till th' owd mon had drawn away; an' then

he'd come'd back i'th dim moonleet, across th' owd moor, that skirts

by th' top end o' Turvin Cloof. An' when he'd getten abeawt a

mile off th' White Heawe, as he wur feightin' on through th' drivin'

snow, o' at once he seed a tall figure of a mon, wi' summat like a

fur cap on his yed, travellin' on abeawt twenty yards afore him, but

he couldn't yer th' seawnd of a footstep. He co'd eawt to him,

for he thought he could like company, but still this tall figure

travell't on, an' not a word nor th' seawnd of a fuutstep; an'

though th' keen woint wur blowin' so strong across th' moor, he said

it never seemed to stir this traveller's clooas (clothes), an' he

began to think it very strange. But when it geet close to th'

owd division stone, between Yorkshire an' Lancashire, he said this

tall figure stopt, and seemed to stare deawn towards th' White

Heawse, an' as he drew nearer up to it he sheawted again, an' then,

he said, it turn't slowly reawnd, an' he could see streaks o' blood

fro th' for-yed, deawn a lung white face; an' then th' whole thing

began a-meltin' away into th' moonleet, an' it seemed to float

across th' road, an' o'er th' moor, i'th direction o' Robin Hood

Bed. An', wi' that, he took to his heels, like a red-shank,

an' never stops till he geet to th' inside o' th' White House

kitchen. . . .

Well, when he'd towd his tale, they made him a bed up, an' he

laft us to ersels (ourselves), for he wur quite done o'er, an' he

durstn't go east again that neet. . . .

As soon as he'd gone, some on 'em i'th kitchen reckon't that

they'd never sin no ghosts; but, evenly, if there wur ghosts o' folk

theirsels, they couldn't see heawe there could be ghosts o' folk's

clooas, ― fur caps an' sich like. But these two keepers wur

very quiet, an' as soon as th' chap had done his tale, one on 'em

whisper's to th' other, 'He's sin Breawn Dick!' An', whether

they believ't i' ghosts or not, they couldn't get one o'th lot to

goo eawt o'th heawse that neet, so they had to find 'em quarters

till mornin'. They wanted no moor music, an' as soon as these

hawkers wur gone to bed, we crope together, reawnd th' fire, an' I

yerd th' tale abeawt 'Breawn Dick,' an' it wur this:

"It seems that lung afore Joe Faulkner coom to th' White

Heawse, it wur kept bi an owd widow woman. Hoo'd buried her

husband fro' th' same heawse; but hoo kept it on, for hoo'd two or

three good owd sarvants abeawt her; an' hoo'd an only son, a fine,

strappin', swipper (active) young fellow, th' pickter of his feyther,

an' th' very leet o'th owd woman's ee. Well, it seems that

this lad, bein' th' nestle-cock, had bin very much marred when

he wur yung both by feyther an' mother. They'd letten him have

his own way, an' he grew up very yed-strung an' maisterful.

An' at after his feyther deed, he becoom quite a terror to th'

country-side, for he took to neet-huntin', an' he geet connected wi'

a lot o' desperate hee-way robbers, that prowl't abeawt th' Edge at

that time o'th day. Some on 'em coom eawt o' Turvin Cloof, an'

some fro' th' Tunshill, another fro' Booth Deighn (Dean), but th'

warst o'th lot wur 'Iron Jack,' that kept th' owd aleheawe, at 'Th'

Buckstones,' wheer th' gang stable't their horses under th' heawse.

Th' owd woman's son wur known bi th' name o' 'Breawn Dick o'

Blacks'n Edge.' . . .

Well, I believe there wur mony a feaw deed done upo' th'

moorlan' roads i' thoose days. Mony a traveller wur stopt an'

robbed, an' mony a lonely heawse wur brokken into, an' stript; an'

neaw an' then, folk disappeared fro' th' road, an' never wur yerd on

again.

News o' these things kept comin' into th' White Heawse, but th' owd

lon'lady little dreamt that her own lad had a hond i' 'em.

Well, that gang wur not brokken into for years an' years. 'Breawn

Dick' use't to be oft away fro' whoam, sometimes two or three days

together; but his mother could never get to know wheer he'd bin; for

he wur very close-temper't, an' very seldom oppen't his meawth to

onybody. . . .

But a' last there coom a lung an' weary day. A whole

week flitted by, an' he never darken't his mother's dur. An'

th' lonely woman began o' mournin' for her son; for, to th' end of

her days, he wur the leet of her ee, an' hoo couldn't see a faut in

him; but, when folk began to ax wheer Dick wur, hoo cried, an' said,

'Nay, there's no accountin' for eawr Richard. He comes an' he

gwos, just as th' fit taks him, an' I noather know wheer he's goon'

nor what he's after, nor when I mun see him again, nor wheer he's

bin, when he gets back. I wish he would stop moor a-whoam,

for I feel so lonely.' But still, day after day, an' week

after week, went by, an' he never coom; an' th' owd woman began o'

lookin' wizzen't an' weary, fur hoo wur frettin' her heart eawt,

neet an' day. At last it began to be clear to everybody that

th' poor owd crayter's senses wur givin' way, for hoo would have two

candles set i'th window every neet, so that he could see th' heawse

i'th dark; an' when th' wynt shook th' dur after hoo'd getten to

bed, hoo'd come deawn an' oppen th' dur an' look into th' dark, an'

hoo'd say, 'Richard, wheerever hasto bin, lad? Come thi ways

in, eawr o'th cowd, thae'll be starve't to deeoth! Thi

supper's i'th oon!' for hoo kept his supper ready for him, neet bi

neet, week after week. But still, he never coom. At

last, hoo geet worse an' worse, an' hoo began o' axin' every

stranger 'at entered th' heawse, if they'd sin Richard, an' hoo kept

turnin' to th' sarvants, an' sayin', 'Han yo sin aught of eawr

Richard?' An' hoo began o' wanderin' up an' deawn th' road,

an' cryin' eawt for him across th' wild moor, as if he wur a little

lad that had gwon an arrand, an' wur lingerin' bi th' way. But

still, week after week went by, an' 'Breawn Dick' never darkens' his

mother's dur. . . .

At last, one wild neet, when o'th heawse wur dark, except th'

two candles hoo kept brunnin' i'th window to leet him whoam, there

wur three men coom shuffling up to th' dur, carryin' another that

had bin shot, an' wur fast hastenin' to his end. When th' owd

woman yerd th' knock hoo wur comin' deawn th' stairs, cryin',

'Richard, wheerever hasto bin?' but th' sarvants kept her back, an'

pacified her as weel as they could. But th' rest o'th heawse

wur astir that neet, for this chap that had bin shot wur bleedin' to

deeoth. He proved to be 'Iron Jack,' a noted neet-hunter, an'

one o' this gang o' robbers that had done sich depredation upo' th'

moor-roads. An' they saddlet a horse, an' th' hostler rode

deawn to Littlebruf (Littleborough) for th' parson an' th' doctor,

an' they geet up to th' White Heawse a very light (few) minutes

afore he drew away (drew his last breath). . . .

It turned eawt that 'Iron Jack' an' another o' th' gang had

stopt these three men upo' th' hee-road, an' threaten't 'em wi'

loaded pistols, if they didn't give up what they had. Well,

they fought for it. One o' these travellers wur a desperate

strung chap, an' he gript 'Iron Jack.' Jack fired at him, an'

just grazed th' tip of his ear, an' then, as they wur wrostlin', mon

to mon, for they liives, tother robber fired, but he missed his

mark, an' shot 'Iron Jack,' an' when he seed Jack drop, he took to

his heels up th' moor-side. An' then these three travellers

carried Jack into th' White Heawse, to dee. . . .

When th' parson an' th' doctor geet to his bed-side, he

hadn't mony minutes' life in him; but he made a terrible confession

afore he drew away. I don't know heaw moray murders an'

robberies he'd had a hond in, but among other things, he said that

five o'th gang had robbed a farm heawse, up at 'Th' Whittaker,' an'

then they'd taen up th' dark moor-side, to th' little cave i'th

bottom o' 'Robin Hood Bed,' an' theer they divided what they'd taen,

bi lantron-leet. Well, to make a lung tale short, it seems

they fell eawt abeawt their spoil, an' one on 'em shot 'Brawn Dick'

through th' yed, an' they buried him abeawt forty yards below Robin

Hood Bed. . . .

Well, when he towd his terrible tale, they tried to get th'

names o'th gang fro' him, but they couldn't. He gaspt an'

moaned to his last, beawt utterin' another word. That wur th'

end o' 'Iron Jack, o' Buckstones,' an' it wur th' end o'th gang,

too; for they wur soon brokken into after that. . . .

Well, they fun th' body, as he towed 'em, sure enough, an' it

wur taen up, an' 'Breawn Dick' wur buried i' Ripponden Churchyard,

close to th' yew-tree hedge. An' th' owd woman followed him to

his grave, witheawt a word, an' witheawt a tear in her ee. Th'

White Heawse had to goo into other honds; for th' poor owd crayter

wur getten quite dateless (disordered in mind), an' hoo wur takken

to live wi' some relations not far fro' Ripponden. But, though

hoo wur harmless, rain or fair, they couldn't keep her in, an'

they had to send a lad wi' her, for hoo would goo an' sit bi th'

side of his grave, an' sing to him, as if he'd bin in his cradle.

An' one cowd day this lad left her, an' went a-playin' him a bit,

an' when he coom back to tak her whoam, he fund her lyin' across he

son's grave, as still as a stone."

CHAPTER IV.

|

Is this thi own yore, or a wig?

BEDFLOCK. |

WHEN the

fiddler's tale was ended, Ben and the old man sat in silent thought

for a few minutes; and then, being both deeply imbued with

superstitious feeling, they were beginning to talk about the old

halls and other places in the district which had the reputation of

being haunted by supernatural beings, when Ben announced the

approach of a stranger, from the direction of Rochdale.

"Hello, Dan," said he, "there's summat comin' at last."

"What's it like?" said the fiddler.

"Nay, I can hardly tell yet," replied Ben.

"Is it a mon or a woman?" inquired the fiddler.

"It should be a mon, o' some mak'," answered Ben, "for, as

far as I can see, it's getten breeches on."

"It may be a woman for that matter," replied the fiddler;

"they wear'n breeches, sometimes. I don't know heaw it is at

yor heawse, Ben, but it is so at eawrs."

"Eawr Betty may wear what hoo's a mind for me," said Ben.

"Weel, an' thae'rt reet, lad," replied the fiddler. "We

getten better through when we letten 'em have a bit o' their own

road."

"Besides, hoo's moor wit nor me, i' some things," continued

Ben, still keeping his eye on the advancing stranger.

"I dar say hoo has," replied the fiddler. "I dar say

hoo has, lad. An' it's weel 'at thae can tak it so."

"Oh, I'll al'ays give in to a reet thing, as wheer it comes

fro'," said Ben.

"That'll do, owd lad," replied the fiddler. "My mother

use't to say that onybody that had ony sense met (might) larn fro' a

foo. . . . But which gate is this thing comin', wi' breeches on?"

"Fro' Rachda' side," answered Ben. "It's a poor tramp,

o' some mak', bi th' look on him. By th' mon, it's Owd

Skudler, I believe."

"Skudler? Skudler?" said the old fiddler. "What

does he do?"

"Well, I connot tell what he is bi trade," answered Ben.

"I can hardly tell what he is, he's so mony jobs; but I think he's

keaw-jobbin' just neaw, bi th' look on him; for he's a cauve-stick

in his hond, as lung as a clooas-prop. An' I know he does a

bit for th' butchers neaw an' then; an' he use't to be a mak (make,

kind) of an odd lad abeawt th' slaughter-heawse, at th' top o'th

Bull Broo, i' Rachda'."

"Oh, I know him!" cried the fiddler. "He's better known

bi th' name o' 'Boot-jack.'"

"I never knowed him bi nought nobbut Skudler," replied Ben.

"Then, I guess thae never ye'rd heaw he geet 'Boot-jack' for

a bye-name," said the old man.

"Nawe; I don't know that ever I did," replied Ben.

"Well, thae knows, abeawt ten year sin, this Skudler wur a

sort of a sarvant mon for owd Clement Royds, at th' Failinge; an'

one time, when he're off wi' th' family, i'th south of Englan', they

put up at an inn for th' neet. Well, it seems that Skudler

geet to mich drink i'th heawse, wi' one an' another on 'em; an' when

it wur gettin' late on, th' owd lad geet wander't into a grand reawm,

wheer there wur twu or three travellers set drinkin' their glass,

afore goin' to bed. Well, one o' these travellers rang th'

bell, an' towd th' waiter to bring him a glass o' brandy an' a

boot-jack, an' owd Skudler stare't at this traveller fro' yed to

fuut, for he thought he're beawn to ha' th' boot-jack to his supper.

At last, Skudler rang th' bell, an' when th' waiter coom, he said,

'Here, bring me a glass o' brandy, an' a boot-jack, too!

If that mon can height (eat) a boot-jack, I con!' That's heaw

he geet th' name o' 'Bootjack!' But he geet th' bag fro'

Clement's, at after, through bein' to fond o' drink."

"Husht, hush!" said Ben. "Here he comes! Neaw,

Skudler, owd lad, is that thee?"

"Hello, Ben!" said Skudler. "Heaw arto?"

"Oh, as nice as ninepence," replied Ben. "Heaw arto

gettin' on, Skud?"

"Just middlin'," said Skudler. Then recognising the old

fiddler, he continued, "Hello, Dan, owd lad, art thou theer, too?"

"Aye. I'm here; I'm here," replied the old man.

"Thae sees, I keep turnin' up again, like Clegg Ho' Boggart."

"And nought but reel, noather," said Skudler. "Nought but

reet, noather, owd lad!" Then, turning towards Ben, he

whispered, as he pushed his fingers through his unkempt hair, "Eh, I

am some ill, to-day, Ben."

"Thae looks rather wild," replied Ben. "What's th'

matter, owd mon?"

"I wur wrestlin' th' champion, again, yesterday," answered

Skudler.

"Th' champion?" said Ben.

"Ay, th' champion," replied Skudler. "An' he geet me

deawn again."

"What champion?" inquired Ben.

"I're drinkin', mon; I're drinkin'!" replied Skudler.

"I geet too mich drink! That's o'!"

"Aye, aye," said the old man; that's th' champion, reet

enough! He's deawn't mony a better chap nor thee, Skudler.

An' he'll deawn mony another, yet."

"I dar say he will," replied Skudler. "I dar say he

will, if they dunnot let him alone. . . . But, beside that,"

continued he, "I've been ill trouble's wi' th' worms, this day or

two back."

"Worms!" cried Ben. "I con tell tho heaw to cure th'

worms, owd lad!"

"Let's be yerrin' (hearing), then," replied Skudler; "for

they dun punish me, to some gauge!"

"Well," answered Ben, "thae knows th' Hauve Moon, i'th Black-wayter,

at Rachda'?"

"Ay, weel enough," replied Skudler.

"Well, then; co theer, as soon as tho gets back," continued

Ben, "an' sup three pints o' their sour ale. An' if it doesn't

kill th' worms, it'll kill thee."

"Oather'll do!" cried the old fiddler, rubbing his hands. "Oather'll

do! But come an' sit tho deawn a minute or two, Skudler."

"Well," replied Skudler, "I've nought again that, noather. I

wur al'ays a good hond at sittin'. If onybody wur to look at

my breeches, they'd find that they wear'n eawt i'th sittin'-quarter

th' first of onywheer. My mother use't to say that I wur just

reet build for sittin' duck-eggs."

"Well," said the old fiddler, laughing, "an' it would be a

nice quiet job, too; for onybody that would gi' their mind to't.

But I deawt thae'd never stick to't lung enough to mak' a fortin

eawt on't. . . . But, wheer arto for, lad; wheer arto for?"

"Well," replied Skudler, "I'm beawn as fur as th' Thistley

Bonk Farm, for a wye-cauve, for Tummy Glen, th' butcher, at Rachda'.

Yo known Jem at th' Thistley Bonk, dunnot yo, Dan?"

"Aye, aye," said the old fiddler, "I know th' whole seed,

breed, an' generation. There's seventeen yards o' brothers on

'em, an' they're two sisters that are aboon five fuut eleven

a-piece. Their mother's just prick-mete their dur-hole full,

to an inch, an' hoo has to bend deawn, an' come eawt sideways.

An' then, Jem had an aint (aunt), his aint Sally, hoo wur so

tall that hoo couldn't for shame stretch hersel'! "

"There's a deeol o' stuff wasted i' makin' folk sich a length

as that, too," replied Skudler.

"Well, I don't think it's a useful size for wark, mysel,'

said the fiddler.

"It depends upo' th' build, an' what sort o' wark they han to

do," said Ben.

"It be reet enough for lamp-leeters an' white-limers, an'

sich like," continued Skudler.

"Well, aye," said the fiddler, "it would save summat i'

ladders, happen."

"Aught fresh deawn i' Rachda'," said Ben, addressing Skudler.

"Well," replied Skudler, "there's bin a bit o' damage done,

here and theer, bi thunner and leetenin', yesterday."

"I say, Dan," said Ben, addressing the old fiddler, "thae'll

remember that greight woint-storm 'at happen't i'th last back-end

(autumn)."

"I should think I do," answered the old man; "it blew part

o'th slate off eawr heawse. It wur a storm, wur that!

Slate-stones, an' windows, an' shutters flew up an' deawn, like

pigeons."

"Well," continued Ben, "that day I wur sit in a aleheawse

kitchen, at Rachda', an' folk kept comin' in wi' news o' this damage

an' that damage, when, just as we'rn sit reawnd th' fire talkin'

together, abeawt th' storm, a chimbley, belungin' th' next heawse,

coom crash deawn, an' part on't fell through th' kitchen-slate wheer

we wur sittin'. But, by th' mon, there wur some scutterin'

abeawt i' that hole. Well, while they'rn agate o' sidin' th'

dirt, an' breek an' stuff, that had fo'n through, there wur a

strange chap coom in, fro' somewheer abeawt Castleton Moor, an' when

he seed this rubbish lyin' upo' th' floor, he said, "What, yo'n had

a bit of a touch o' this woint, I see. But, eh, by th' mass,"

said he, "it's bin a deeol war (worse) wi' us! I wur in a

heawse at Castleton Moor, this forenoon, an' it blew th' window slap

eawt; an' in abeawt two minutes at after, th' woint brought another

window wap into th' same place, an' it just fitted, to a yure

(hair)."

"Nea then, Ben," said Skudler, "thae's done it at last."

"Aye," said the fiddler, "I think he's polish't that tale off

middlin' weel."

"Yo han it as I had it," replied Ben. "But I thought at

that time, that if this chap had said mich moor o' that mak, he'd

ha' bin agate o' lyin'."

"Well, come," said Skudler, rising to his feet, "I mun be

off."

So they bade him "good day!" and away he went, to fetch his

wye-calf.

And, after a few minutes' further chat together, the old

blind fiddler whistled his lad from the next field, and, taking his

fiddle-bag under his arm, he shook hands with Ben, and went his way

towards Bacup, with his face up-turned to the sky, and holding his

little lad by the hand.

.

.

.

.

"Theer he gwos!" said Ben, looking up the road after the old

fiddler. "There he gwos, like a good un, as he is!

Good luck go witho, owd crayter, for thae'rt one o'th better end o'

God Almighty's childer!" and when he had watched the old man out of

sight, he said, as he turned his face the other way, "It's time for

me to be hutchin' a bit nar (nearer) Yelley Ho! It connot be

so fur off noon."

As he went singing up the road towards the hall, under the

thick-leaved shade, through which the strong sunshine stole here and

there, freaking the highway with streaks of gold, he met a stout old

farmer descending the road, and dressed in his best, as if he was on

his way to a cattle fair. When they drew near, Ben stopped,

and asked the old man what o'clock it was.

"It's close upo' puddin'-time, if my stomach's aught to go

by," said the old man, eyeing Ben all over as he pulled a large,

old-fashioned silver watch out of his fob. "It'll be within a

light (few) minutes o' noon, I'll be bund. But I'll look at

this silver turnip o' mine, as soon as I can get it eawt."

And, as he tugged at the chain, he continued, "What, I guess thae'rt

hungry? Thae's rayther a twelve o'clock mak of a look, lad."

"Yo'n sided some beef i' your time, too, maister; bith' look

on yo," replied Ben.

"Well, lad," said the old man, looking at his watch, "I've

done middlin', for sure. . . . Let's see, I'm rayther of oather

fast; but it wants abeawt five minutes o' twelve, bi Rachda' (by

Rochdale Church clock)."

"Thank yo!" replied Ben. "Good day!"

"Good day to thee answered the old man, taking his stick from

the hedge side again, and trudging sturdily down the road.

When he had got a few yards off, he turned round, and cried out to

Ben, "Heigh, my lad!"

"Nea then!" said Ben, looking back.

"I've bin towd yo'n had some lumber done abeawt here

yesterday, bi thunner an' leetenin'. Hasto yerd aught?"

"Well, ay," replied Ben. "There's bin four keaws kilt

up i'th White Hill pastur', here; an' it's knocked th' gable-eend of

a heawse in, up Facit road on."

"So I've bin towd," said the farmer. "An' I yer there's

bin a woman kilt deawn at Shay Cloof, yon."

"Nay, sure," replied Ben. "Dun yo know who it is?"

"Well, I did yer th' name," said the old man, "but it's

slipped mi mind. But I deawt we's yer o' moor, yet; for I

don't know 'at I con recollect a heavier storm, i' my time."

"Nawe, nor me noather," replied Ben. "But it's takken

up nicely."'

"It has," said the old man. "Han yo mich hay eawt,

abeawt here?"

"Oh nawe," replied Ben. "Very light (very little)."

"Come, that's better," said the farmer. "Well, good day

to tho!"

"Good day," answered Ben.

And then the old man went his way, and Ben was left loitering

about under the shade of the trees, waiting for the stroke of

twelve.

"Come," said he, rubbing his hands, "they connot say that I'm

too lat this time! I'll walk in just to th' minute,

like clock-wark! That'll stop their meawths, I should think. .

. . It wants abeawt four minutes, yet," continued he, groping at his

sore nose. "I'll watch till it strikes." He was close to

the yard door, and as he paced to and fro in front of it, he

straightened his clothing, and trimmed his posy, and tied his

kerchief afresh, with nervous fingers; for he was naturally shy and

sensitive. There was a well by the wayside, a few yards off,

and going up to it, he bent down to examine the reflection of his

face in the water, and when he had looked himself well over, and had

given another finishing touch to his kerchief, he said, "Come, I

think I's do!" Then walking back, he halted at the yard door,

and peeping through the lock-hole, said, "I wonder wheer that dog

is?" The last word had hardly left his mouth, when the great

clock in the hall kitchen began to strike the hour of twelve, and

the kitchen-door being wide open, the sound of each stroke came with

a solemn, measured pause between, clear and sonorous, into the

noontide air of that still and shady spot. Ben's heart beat