|

JOHN

RENNIE, the architect of

the three great London Bridges, the engineer of the Plymouth

Breakwater, of the principal London Docks, and other works of great

national importance, was born at the farmsteading of Phantassie,

East Lothian, on the 7th of June, 1761. His father, James Rennie,

was the owner of the patrimonial estate, situated about midway

between Haddington and Dunbar, at the foot of the gently-sloping

hills which rise from it towards the south, the village of East

Linton lying close at hand, on the farther bank of the little river

Tyne.

The only post road from London to Scotland passed close in front of

the house at Phantassie in which John Rennie was born. It passed

westward over Pencrake, and followed the ridge of the Carleton Hills

towards Edinburgh. The old travellers had no aversion to hill tops,

rather preferring them because the ground was firmer to tread on,

and they could better see about them. This line of high road avoided

the county town, which, lying in a hollow, was unapproachable across

the low grounds in wet weather; and, of all things, swamps and

quagmires were most to be dreaded. A portion of the old post-road

was visible until within the last few years, upon the high ground

about a mile to the north of Haddington. In some places it was very

narrow and deep, not unlike an old broad ditch, much waterworn, and

strewn with loose stones. Along this line of way Sir John Cope

passed with his army, in 1745, to protect Edinburgh against the

Highland rebels; and it is related that, on marching northward to

intercept them, he was compelled to halt for several days, waiting

for a hundred horse-loads of bread required for the victualling of

his army.

In 1750, a project was set on foot for improving the high road

through East Lothian, and a Turnpike Act was obtained for the

purpose—the first Act of the kind obtained north of the Tweed. [p.218] The inhabitants of the town of Haddington complained loudly of the

oppression practised on them, by making them pay toll for every bit

of coal they burned; though before the road was made, it was a good

day's work for a man and horse to fetch a load of "divot" or Turf

from Gladsmuir, or of coal from the nearest colliery, only some four

miles distant. By the year 1763 this post-road must have been made

practicable for wheeled vehicles; for in that year the one

stage-coach, which for a time formed the sole communication of the

kind between London and all Scotland, began to run; and John Rennie,

when a boy, was familiar with the sight of the uncouth vehicle

lumbering along the road past his door. It "set out" from Edinburgh

only once a month, the journey to London occupying from twelve to

eighteen days, according to the state of the roads.

Dr. Carlyle, in his 'Autobiography,' says, that in 1757, he made an

excursion into England, with Sir David Kinloch and some other

gentlemen. The baronet and himself rode in a postchaise, a "vehicle

which had but recently been brought into Scotland, as our turnpike

roads were then in their infancy." [p.219-1] A short time before, when Home, the poet, accompanied by some six or

seven Merse ministers, were proceeding to London to get the play of

Douglas put upon the stage, the entire party rode on horseback. But

Home, like an oblivious poet, forgot to provide himself with a pair

of leathern bags to put his manuscript in; and he consequently had

to balance himself on his horse by putting his tragedy in one pocket

of his great coat and his clean shirt and night-cap in the other. "By good luck," says the minister, "the Tweed was not come down, and

we crossed it safely at the ford near Norham Castle." [p.219-2]

When Rennie was born, Scotland was a very poor country. Perhaps East

Lothian, being a border county, was one of the poorest. It had been

constantly overrun and despoiled during the wars with England. Haddington was thrice burnt to the ground. For four centuries, from

Edward I. to Oliver Cromwell, the border counties were constantly

liable to invasion. The last time East Lothian was spoiled was

before the battle of Dunbar. Agriculture had not yet recovered from

these frequent attacks. It had become a lost art. But about the

middle of last century, agriculture began to show signs of revival. The country as yet consisted mostly of moorland, peat, and bogs. Very little corn was raised; and when the first wheat was grown in a

field near Edinburgh, all the country flocked to see it. [p.220] James Rennie, the engineer's father, was one of the first to

introduce turnips as a regular farmer's crop; for, before his time,

neither clover, turnips, nor potatoes were grown in Scotland. Cattle

could with difficulty be kept alive; and the people themselves were

often on the brink of starvation. They were hopeless, miserable, and

without spirit. Some thought that The Union had utterly destroyed

Scottish prosperity. There were even Repealers in those days; [p.221]

but they could not successfully combine. There was very little

communication between country and town, or between one town and

another; for during the greatest part of the year, the roads were

simply impassable. The Darien Expedition had ruined those who had

put their money in it; and the people seemed to have no spirit to

make any further attempt to prosper. It would appear as if neither

skill, money, nor enterprise, remained in the land.

Engineering and architecture, like agriculture, seem also to have

become lost arts. The few small bridges built at the beginning of

the eighteenth century were of a frightful character. They were of a

circular form; so that, when erected across a stream of say twenty

feet in breadth, they rose ten feet in height from the spring of the

arch, and descended ten feet on the other side. Crossing a bridge of

this sort was like climbing over the roof of a house. The bridge

builders of those days had no notion that the segment of a circle,

well supported at its springing, was as strong as the full bow. But

bridge-building had not always been in this backward state in

Scotland. It is probable that the whole country—or at least the

Lowland part of it—was in a much more flourishing condition previous

to the commencement of the fourteenth century, than it was for some

four hundred and fifty years after that time.

The highly improved state of architecture in early times—as is still

exhibited in the ruins of the ancient abbeys of Melrose, Elgin,

Kilwinning, Aberborthwick, and other religious institutions—lead us

to conclude that the other arts and sciences were in a much more

forward state than they have been at a more recent period. The same

"Brothers of the Bridge" who erected so many fine old bridges

across the rivers of England, were equally busy beyond the Tweed,

providing those essential means of intercourse for the community. Thus we find Old Bridges early erected across most of the rapid

rivers in the Lowlands, especially in those places where the

ecclesiastical foundations were the richest; and to this day the

magnificent old abbey or cathedral of the neighbourhood—in some

corner of which the Presbyterian Church continues to hold its

worship—serves to remind one of the contemporaneous origin of both

classes of structures.

Thus, as early as the thirteenth century, there was a bridge over

the Tay at Perth; bridges over the Esk at Brechin and Marykirk; one

over the Dee at Kincardine O'Neil; one at Aberdeen; and one at the

mouth of Glenmuick. The fine old bridge over the Dee, at Aberdeen,

is still standing: it consists of seven arches, and, as usual, the

name of a bishop—Gawin Dunbar is connected with its erection. There

is another old bridge over the Don near the same city, said to have

been built by Bishop Cheyne in the time of Robert the Bruce—the

famous "Brig of Balgonie," celebrated in Lord Byron's stanzas as "Balgownie

Brig's black wa'." It consists of a spacious Gothic arch, resting

upon the rock on either side. There was even an old bridge over the

rapid Spey at Orkhill.

Then at Glasgow there was a fine bridge over the Clyde, which used,

in old times, to be called "the Great Bridge of Glasgow," said to

have been built by Bishop Rae in 1345. Though the bridge was only

twelve feet wide, it consisted of eight arches; somewhat similar to

the ancient fabric which still spans the Forth under the guns of

Stirling Castle. This last-mentioned bridge was, until recent times,

a structure of great importance, affording almost the only access

into the northern parts of Scotland for wheeled carriages.

But the art of bridge-building in Scotland, as in England, seems for

a long time to have been almost entirely lost; and until Smeaton was

employed to erect the bridges of Coldstream, Perth, and Banff, next

to nothing had been done to improve this essential part of the

communications of the country. Where attempts were made by local

builders to erect such structures, they very rarely stood the force

of a winter's, or even a summer's, flood. "I remember," says John

Maxwell, "the falling of the Bridge of Buittle, which was built by

John Frew in 1722, and fell in the succeeding summer, while I was in

Buittle garden seeing my father's servants gathering nettles [for

food]." [p.223] A similar fate

befell the few attempts that were made about the same time to

maintain the lines of communication by replacing the old bridges

where they had gone to ruin, or substituting new ones in place of

fords.

The mechanical arts had also fallen to the very lowest state. All

kinds of tools were of the most imperfect description. The

implements used in agriculture were extremely rude. They were mostly

made by the farmer himself, in the roughest possible style, without

the assistance of any mechanic. But a plough, which was regarded as

a complicated machine, was reserved for the blacksmith. It was made

of young birch trees, and, if the tradesman was expert, it was

completed in the course of a winter's evening. [p.224] This rude implement scratched, without difficulty, the surface of

old crofts, but made sorry work in out-fields, where the sward was

tough and stones were large and numerous. Lord Kaimes said of the

harrows used in his time, that they were more fitted to raise

laughter than to raise mould. Machinery of an improved kind had not

yet been introduced into any department of labour. Its first

application, as might be expected, was in agriculture,—then the

leading, and indeed almost the only, branch of industry in Scotland;

and the introduction of machinery will be found both curious and

interesting, in its bearing on the subject of our present memoir.

There was one fruitful art, however, remaining in Scotland, which

was calculated, more than anything else, to restore the prosperity

of the country —and that was, the art of teaching. The number of

schools throughout the country was considerable, in which the rising

generation were well and wisely taught. The "Grammar-schools" in the

principal boroughs existed before the Reformation; the parish

schools were one of the principal results of the Reformation. The

Grammar-schools were founded by benevolent individuals, who vested

in the church, or in the burgh corporations, certain property or

sums of money, for the purpose of educating the youth of the towns

in which they were established. That they existed in the towns when

Scotland was a Catholic country, is clear from the fact that John

Knox himself was educated at the Grammar School of Haddington, of

which town he was a native; and he relates that he there learnt the

elements of the Latin language.

But these burgh schools were insufficient for the general education

of the people,—who, for the most part, lived in the country, and

could scarcely approach the towns during the greater part of the

year, by reason of the badness of the roads. Accordingly, one of the

first measures which John Knox proposed to the Lords of the Assembly

after the Reformation, was the establishment of a school, supported

by the heritors, or proprietors of land, in every parish throughout

the country. In his first 'Book of Discipline' he explicitly set

forth, "That every several Kirke have ane schoolmaister appointed,

able to teach grammar and the Latin tongue, if the town be of any

reputation;" and, if an upland town, then a reader was to be

appointed, or the minister himself must attend to the instruction of

the children and youth of the parish. It was also enjoined that "provision be made for the attendance of those that be poore, and not

able by themselves or their friends to be sustained at letters;"

"for this," it was added, "must be carefully provided, that no

father, of what estate or condition that ever he may be, doth use

his children at his own fantasie, especially in their youthhead; but

all must be compelled to bring up their children in learning and

virtue."

This was admirable advice, but it could not be carried into effect

for more than a hundred years. The civil wars, the attempts made to

impose Episcopacy upon Scotland, and the troubles of the nation down

to the Revolution of 1688, prevented the people uniting for the

purpose of establishing a school in every parish; but at length, in

1696, the Scottish Parliament was enabled, with the concurrence of

William III., to put in force the Act of that year, which is

regarded as the charter of the parish-school system of Scotland. It

is there ordained, "that there be a school settled and established

and a schoolmaster appointed in every parish not already provided,

by advice of the heritors and minister of the parish."

In consequence of the operation of this Act, which was gradually

carried into effect, the parish schools of Scotland, [p.226]—working

steadily upon the rising generation, all of whom passed under the

hands of the parish teachers,—were training up a population whose

education and intelligence were greatly in advance of their material

condition; and it is to this circumstance, we apprehend, that the

true explanation is to be found of that rapid leap forward which the

country now took, dating more particularly from the year 1745. Agriculture was naturally the first branch of industry affected; new

crops were introduced, new methods of farming, new machinery for

ploughing, harrowing, and reaping the produce of the land. These

improvements were followed by like advances in manufactures,

commerce, and shipping—by discoveries in invention, of which the

Condensing Steam-Engine, discovered by James Watt, was by far the

most important. [p.227] Indeed,

from that period, Scotland has never looked back; but her progress

has gone on at a constantly increasing rate and has issued in

results as marvellous as they have probably been unequalled. A

century of Work has raised Scotland from the position of one of the

poorest and most miserable of countries, to that of one of the best

cultivated, most prosperous, and intelligent in Britain.

Farmer Rennie died in the old house at Phantassie in the year 1766,

leaving a family of nine children, four sons and five daughters. George, the eldest, was then seventeen years old. He was discreet,

intelligent, and shrewd beyond his years, and from that time forward

he managed the farm and acted as head of the family. The year before

his father's death he had made a tour through Berwickshire, for the

purpose of observing the improved methods of farming introduced by

some of the leading gentry of that county, and he returned to Phantassie full of valuable practical information. The agricultural

improvements which he was shortly afterwards instrumental in

introducing into East Lothian were of a highly important character. His farm came to be regarded as a model, and his reputation as a

skilled agriculturist extended far beyond the bounds of his own

country, insomuch that he was afterwards resorted to for advice as

to farming matters, by distinguished visitors from all parts of

Europe. [p.228]

Of the other sons, William, the second, went to sea: he was taken

prisoner during the first American war, and was sent to Boston,

where he died. The third, James, studied medicine at Edinburgh, and

entered the army as an assistant-surgeon. The regiment to which he

belonged was shortly after sent to India: he served in the

celebrated campaign of General Harris against Tippoo Saib, and was

killed while dressing the wound of his commanding officer when under

fire at the siege of Seringapatam.

John, the future engineer, was the youngest son, and only five years

old at the death of his father. He was accordingly brought up mainly

under the direction of his mother,—a woman possessed of many

excellent practical qualities, amongst which her strong common sense

was not the least valuable.

The boy early displayed his strong inclination for mechanical

pursuits. When about six years old, his principal toys were his

knife, hammer, chisel, and saw, by means of which he indulged his

innate love of construction. He preferred this kind of work to all

other amusements, taking but small pleasure in the ordinary sports

of boys of his own age. His greatest delight was in frequenting the

smith's and carpenter's shops in the neighbouring village of Linton,

watching the men use their tools, and trying his own hand when they

would let him.

But his favourite resort was Andrew Meikle's millwright's shop, down

by the river Tyne, only a few fields off. When he began to go to the

parish school, then at Prestonkirk, he had to pass Meikle's shop

daily, going and coming; and he either crossed the river by the

planks fixed a little below the mill, or by the miller's boat when

the waters were high. But the temptations of the millwright's

workshop while passing to school in the mornings not unfrequently

proved too great for him to resist, and he played truant. He then

tried to "make things," and worked at the bench and the forge. The

appearance of his fingers and clothes on his return home, revealed

the secret of his employment; when a severe interdict was laid

against his "idling" away his time at Andrew Meikle's shop.

The millwright, on his part, had taken a strong liking for the boy,

whose tastes were so congenial to his own. Besides, he was somewhat

proud of his landlady's son frequenting his house, and was not

disposed to discourage his visits. On the contrary, he let him have

the run of his workshop, and allowed him to make his miniature

water-mills and windmills with tools of his own. The river which

flowed in front of Houston Mill was often swollen by spates or

floods, which descended from the Lammermoors with great force; and

on such occasions young Rennie took pleasure in watching the flow of

the waters, and following the floating stacks, fieldgates, and other

farm wreck along the stream, down to where the Tyne joined the sea

at Tyningham, about four miles below.

Amongst his earliest pieces of workmanship was a fleet of miniature

ships. But not finding tools to suit his purposes, he contrived, by

working at the forge, to make them for himself; then he constructed

his fleet, and launched his ships, to the admiration and

astonishment of his playfellows. This was when he was about ten

years old. Shortly after, by the advice and assistance of his friend Meikle, who took as much pride in his performances as if they had

been his own, Rennie made a model of a windmill, another of a

fire-engine (or steam-engine), and another of Vellore's pile-engine,

displaying a considerable amount of manual dexterity; some of these

early efforts of the boy's genius being still preserved.

Though young Rennie thus employed so much of his time on amateur

work in the millwright's shop, he was not permitted to neglect his

ordinary education at the parish school. That of Prestonkirk was

kept by a Mr. Richardson, who taught his pupil well in the ordinary

branches of education; but by the time Rennie had reached twelve

years of age, he seems almost to have exhausted his master's store

of knowledge, and his mother then thought the time had arrived to

remove him to a seminary of a higher order.

He was accordingly taken from the parish school, though his friends

had not yet made up their minds as to the steps they were to adopt

with reference to his further education. The boy, however, found

abundant employment for himself with his tools, and went on

model-making; but feeling that he was only playing at work, he

became restless and impatient, and entreated his mother that he

might be allowed to go to Andrew Meikle's to learn to be a

millwright.

He was accordingly sent to Meikle's, where he worked for two years,

and learnt one of the most valuable parts of education—the use of

his hands. He seemed to overflow with energy, and was ready to work

at anything—at smith's work, carpenter's work, or millwork; taking

most pleasure in the latter, in which he shortly acquired

considerable expertness. Having the advantage of books—limited

though the literature of mechanism was in those days—he studied the

theory as well as the practice of mechanics, and the powers of his

mind became strengthened and developed by means of steady

application and self-culture.

At the end of two years, his friends determined to send him to the

burgh school of Dunbar, one of that valuable class of seminaries

directed and maintained by the magistracy, which have been

established for the last hundred years and more in nearly every town

of any importance in Scotland. Dunbar High School was then a school

of considerable celebrity. Mr. Gibson, the mathematical master, was

an excellent teacher, full of love and enthusiasm for his

profession; and it was principally for the benefit of his discipline

and instruction that young Rennie was placed under his charge. On

entering this school, he possessed the advantage of being fully

impressed with a sense of the practical value of intellectual

culture. His two years' service in Meikle's workshop, while it

trained his physical powers had also sharpened his appetite for

knowledge, and he entered upon his second course of instruction at

Dunbar with the disciplined powers of a grown man. He had also this

advantage, that he prosecuted his studies there with a definite aim

and purpose, and with a determinate desire to master certain special

branches of education required for the successful pursuit of his

intended business.

Accordingly, we are not surprised to find that in the course of a

few months he outstripped all his schoolfellows, and took the first

place in the school. A curious record of his proficiency as a

scholar is to be found in a work by Mr. David Loch,

Inspector-General of Fisheries, published in 1779. [p.233] It was his duty to hold a court of the herring skippers of Dunbar,

then the principal fishing-station on the east coast; and it appears

that at one of his visits to the town he attended an examination of

the burgh schools, and was so much pleased with the proficiency of

the pupils that he makes special mention of it in his book.

After speaking of the teachers of Latin, English, and arithmetic, he

goes on to say:

"But Mr. Gibson, teacher of mathematics, afforded a

more conspicuous proof of his abilities, by the precision and

clearness of his manner in stating the questions which he put to the

scholars; and their correct and spirited answers to his

propositions, and their clear demonstrations of his problems,

afforded the highest satisfaction to a numerous audience. And here I

must notice in a particular manner the singular proficiency of a

young man of the name of Rennie. He was intended for a millwright,

and was breeding to that business under the famous Mr. Meikle, at

Linton, East Lothian. He had not then attended Mr. Gibson for the

mathematics much more than six months, but on his examination he

discovered such amazing power of genius, that one would have

imagined him a second Newton. No problem was too hard for him to

demonstrate. With a clear head, a decent address, and a distinct

delivery, he gave ready solutions to questions in natural and

experimental philosophy, and also the reasons of the connection

between causes and effects, the power of gravitation, &c., in so

masterly and convincing a manner, that every person present admired

such an uncommon stock of knowledge amassed at his time of life. If

this young man is spared, and continues to prosecute his studies, he

will do great honour to his country."

Rennie remained with Mr. Gibson for about two years. During that

period he went as far in mathematics and natural philosophy as his

teacher could carry him; after which he again proposed to return to Meikle's workshop. But about this time the mathematical master was

promoted to a higher charge—the rectorship of the High School of

Perth—and a question arose as to the appointment of his successor. The loss to the town was felt to be great, and Mr. Gibson was

pressed by the magistrates to point out some person whom he thought

suitable for the office. The only one he could think of was his

favourite pupil; and though not quite seventeen years old, he

strongly recommended John Rennie to accept the appointment.

The young man, however, already beginning to be conscious of his

powers, had formed more extensive views of life, and could not

entertain the idea of settling down as the "dominie" of a burgh

school, respectable and responsible though that office might be. He

accordingly declined the honour which the magistrates proposed to

confer upon him, but agreed to take charge of the mathematical

classes until Mr. Gibson's successor could be appointed. He

continued to carry on the classes for about six weeks, and conducted

them so satisfactorily that it was matter of much regret when he

left the school and returned to his family at Phantassie for the

purpose of prosecuting his intended profession.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

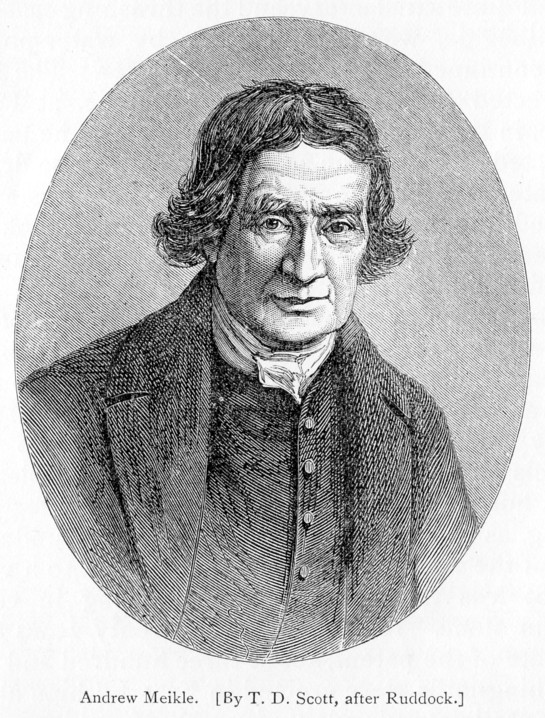

RENNIE'S MASTER—ANDREW MEIKLE.

ANDREW

FLETCHER, of Saltoun,

fled into Holland during the political troubles in the reign of

Charles II., and during his residence there, he was particularly

struck by the expert methods employed by the Dutch in winnowing corn

and shealing barley. The chaff was then ordinarily separated

from the corn by means of wind upon a knoll, or a draught of air

blowing through the barn-door; and barley was shealed by pounding

the grains with water in the hollow of a stone, until by that means

the husks were rubbed off.

Fletcher saw that there was a great waste of labour and food

in these processes—for oat-and-barley-meal formed the principal food

of Scotland—and during his residence abroad he determined to

introduce the Dutch methods into his own country. Writing home

to his brother, he desired him to send out to Holland one James

Meikle, an ingenious country wright of Wester Keith, [p.236]

for the purpose of learning the above arts and importing the

requisite machinery into Scotland.

After a stay of about two months in that country, Meikle

returned home, bringing with him a winnowing machine, commonly

called a pair of fanners, and the ironwork requisite for a

barley-mill. These were safely transported to Leith, and

afterwards conveyed to Saltoun, where the barley-mill was erected

and set to work; and for many years it was the only machine of the

kind in the British dominions—so slow were people in those days to

copy the improvements of their neighbours. "Saltoun barley"

was the name by which dressed pot barley then became known, and it

continued to preserve the name long after barley-mills had come into

general use.

James Meikle was equally successful in constructing his

fanners for winnowing corn; but they had much superstitious

prejudice to encounter,—the country people looking upon the grain

cleaned by them with suspicion, as procured by "artificially-created

wind." The clergy even argued that "winds were raised by God

alone, and it was irreligious in man to attempt to raise wind for

himself, and by efforts of his own;" and one clergyman even refused

the holy communion to such of his parishioners as irreverently

raised "Devil's wind." The readers of 'Old Mortality' will

remember Mause Headrigg's indignation when it was proposed that her

"son Cuddie should work in the barn wi' a new-fangled machine for

dightin' the corn frae the chaff, thus impiously thwarting the will

of Divine Providence by raising wind for your leddyship's ain

particular use by human art, instead of soliciting it by prayer, or

waiting patiently for whatever dispensation of wind Providence was

pleased to send upon the shealing-hill." Scott, however, was

obviously guilty of an anachronism in this passage, for the first

pair of fanners was not set up at Saltoun until the year 1720—long

after the period of Cuddie Headrigg's supposed trial—and it was not

until seventeen years later that another winnowing-machine was set

up in the neighbouring shire of Roxburgh, and employed as an

ordinary agency in farming operations.

Andrew Meikle was the only surviving son of Fletcher's

millwright, and like him was a clever mechanic. He had married

and settled at Houston Mill, on James Rennie's Phantassie estate,

where he combined the occupations of small farmer, miller, and

millwright. He had himself fitted up the machinery of the

mill, of which he was the tenant; and adjoining it was his

millwright's shop, where he carried on his small business in

connection with millwork—the demands of the district being as yet of

an extremely limited character.

But the march of agricultural improvement had by this time

fairly begun in East Lothian. [p.239-1]

The public spirit displayed by Fletcher of Saltoun was imitated by

his neighbours. But probably the gentleman who gave the

greatest impulse to agricultural progress in the county, which

shortly after extended itself over Scotland, was Mr. Cockburn of

Ormiston, to whom belongs the honour of adopting the system of long

leases. He early became convinced that the surest way of

stimulating the industry of the farmer was to give him a substantial

interest in the improvement of the land which he farmed. One

of his tenants having enclosed his fields with hedges and ditches at

his own cost—the first farmer in Scotland who adopted the practice [p.239-2]—his

landlord, to encourage his spirit of improvement, granted him a

lease of his farm for nineteen years, renewable at the expiry of

that term for a like period.

The results were found so satisfactory, that Mr. Cockburn was

induced to extend the practice, and before long it became generally

adopted throughout the county. From that point agriculture

advanced with extraordinary rapidity. The more thriving

farmers sent their sons into England—a practice long since

reversed—to learn the best methods of farming: they employed better

implements and improved methods of culture; their landlords, further

to encourage them, built more commodious steadings and farmhouses;

and they were greatly helped in this course by the unusual

facilities for obtaining credit which persons of standing and

property possessed, on the general extension, from about the middle

of last century, of what is called the Scotch system of banking. [p.240]

These measures soon put an entirely new face on the country.

The distinction of "in-field" and "out-field" altogether ceased.

Farms became completely enclosed, and sheep and black cattle were no

longer allowed to roam at large. Fields were thrown together,

and small holdings consolidated into large ones. The moorland

and the bog were reclaimed and converted into fruitful farms.

A single instance, of some historical interest, may be given.

When the Royal army lay upon the field of Prestonpans in 1745, their

front was "protected by a deep bog," across which Robert Anderson, a

young gentleman of the county, who knew every foot of the ground,

contrived to lead the Pretender's army by a path known only to

himself. That bog, like so many others, has long since been

reclaimed by drainage and cultivation, and now forms part of one of

the most fertile farms in the Lothians.

Such was the improving state of affairs in East Lothian when

Andrew Meikle began business at Houston Mill. His reputation

as a mechanic and his skill in millwork were such, that he was

usually employed in repairing and erecting mills in his own and the

adjoining counties. Being an ingenious and thoughtful man, he

eagerly turned his attention to the improvement of agricultural

machinery, more especially of that connected with the thrashing,

winnowing, dressing, and grinding of grain. Thus, as early as

the year 1768, we find him taking out a patent—one of the very first

taken out by any Scotch mechanic—for a new machine contrived by him

for dressing and cleansing corn. [p.241]

It was a combination of the riddle and fanners; and, though of no

great novelty, it showed the direction in which his inventive

faculties were at work.

Nothing caused so much loss and vexation to the farmer in

former times as the operation of separating the corn from the straw.

In some countries it was trodden out by cattle; hence the Biblical

proverb, "Thou shalt not muzzle the ox that treadeth out the corn."

Sledges or trail-carts were also used for the same purpose; but the

most common instrument employed was the flail. By either of

these methods, however, the process of thrashing was slowly

performed, whilst a considerable portion of the grain was damaged or

lost.

Many attempts had been made before Meikle's time to invent a

machine which should satisfactorily perform this operation; but

without effect. An East Lothian gentleman, named Michael

Menzies, contrived one upon the principle of the flail, arranging a

number of flails so as to be worked by a waterwheel; but they were

soon broken to pieces by the force with which they fell.

Another experiment was made in 1758 by a Stirlingshire farmer, named

Leckie, who invented a machine on the principle of the horizontal

flax-mill. It consisted of a vertical shaft, with four

cross-arms fixed in a box, and when set in motion the arms beat off

the grain from the straw when let down upon them by hand.

Though this machine succeeded very well in thrashing oats, it cut

off the heads of every other kind of corn submitted to its

operation.

Similar attempts were made about the same time by farmers in

the south, more especially by Mr. Ilderton at Alnwick, Mr. Smart at

Wark, and Mr. Oxley at Flodden, about 1772-3. The machine

employed by these gentlemen was composed of a large drum, about six

feet in diameter, resembling a sugar hogshead, round which were

placed a number of fluted rollers, which pressed inwards upon the

drum by means of springs. The corn, in passing the cylinder

and rollers, was no doubt rubbed out; but a large proportion of it

being bruised and damaged by the operation, this plan too was

eventually abandoned. Mr. Oxley is said to have afterwards

tried the plan of stripping the corn from the straw by means of a

scutcher; but the machine constructed with this object did not

answer, and it was also laid aside.

Mr. Kinloch, [p.242] of

Gilmerton in East Lothian, had however seen the last-mentioned

machine at work, and he conceived the idea of improving it. He

accordingly had a model made, in which he contrived that the drum,

mounted with four pieces of fluted wood, should work upon springs,

pressing with less force upon the corn in the process of rubbing it

out. This model was shown to Meikle, with whom Mr. Kinloch had

many conversations on the subject; and at the millwright's

suggestion several improvements were made in it, one of which was

the substitution of smooth feeding rollers for fluted ones.

When the model had been completed, Mr. Kinloch sent it to Houston

Mill to be tried by the power of Meikle's water-wheel. On

being set to work, however, it was driven to pieces in a few

minutes; and the same fate befell a larger machine after the same

model, which Mr. Kinloch got made for one of his tenants a few years

later.

The best result of Mr. Kinloch's experiments was, that they

had the effect of directing the inventive mind of Andrew Meikle to

the subject. After several years' thinking and planning, he

constructed a thrashing-machine, about the year 1776. It

consisted of a number of flails fixed in a strong beam moved by a

crank, which beat out the corn on two platforms, one on each side of

the beam. The performance of this machine, in the presence of

some East Lothian farmers who went to see it at work, was on the

whole satisfactory, [p.243] yet it

did not come up to Meikle's expectations. On one of the

gentlemen observing that the flails and platforms probably would not

bear the force of the stroke, the inventor replied, that in case the

machine did not answer, he intended to try a method of beating out

the corn by means of fixed scutchers or beaters. [p.244]

Accordingly he proceeded to work out this idea in practice,

and after a few years he succeeded in perfecting his invention on

this principle, which was entirely new. These scutchers, shod

with iron, were fixed upon a strong beam or cylinder, which revolved

with great velocity, and in the process of so revolving, beat off

the corn instead of rubbing it off by pressure, as had been

attempted by former contrivers. By dint of study and

perseverance he succeeded at length in perfecting his machine; to

which he added solid fluted feeding rollers, and afterwards a

machine for shaking the straw, fanners for winnowing the corn, and

other improvements.

Meikle is said to have been superintending a mill job at

Leith, at the time when he was engaged in working out this

contrivance in his mind. He was accustomed to walk there and

back within the same day while his job was in hand, or a distance of

about forty miles. He studied the subject during his journey,

and would occasionally stop while travelling to draw a rapid diagram

upon the road with his walking-stick. It is related of him

that on one occasion, whilst very much engrossed with the subject of

his thrashing-mill, he had, absorbed by his calculations, wandered

considerably from the right path. He stopped short suddenly,

and hastily sketching his plan on the road, exclaimed, "I have got

it! I have got it!" Archimedes himself, when he cried

"Eureka," could not have been more delighted than our millwright was

at the happy upshot of his deliberations.

The first machine erected on Meikle's new principle was put

up in 1787 for Mr. Stein of Kilbeggie, in Clackmannanshire, who had

great difficulty in procuring a sufficient number of barnsmen for

thrashing straw to litter the large stock of cattle he had on hand;

but the novelty of the experiment, and the doubt entertained by Mr.

Stein as to the efficacy of the proposed machine, induced him to

require, as a condition, that if it did not answer the intended

purpose, Meikle was not to receive any payment for it. The

result, however, proved quite satisfactory, and the

thrashing-machine at Kilbeggie, which was driven by water-power,

long continued in good working order. The next he erected was

for Mr. George Rennie, at Phantassie, in the same year; and by this

time he had so perfected his machine as to enable it to be driven by

water, wind, or horses. That at Phantassie was worked by

horse-power. In 1788 Meikle took out a patent for his

invention, describing himself in the specification as "engineer and

machinist." [p.246]

The thrashing-machine proved to be one of the greatest boons

ever conferred upon the husbandman, and effected an immense saving

of labour as well as of corn. By its means from seventy to

eighty bushels of oats, and from thirty to fifty bushels of wheat,

might be thrashed and cleaned in an hour; and it is calculated to

have effected a saving, as compared with the flail, of one-hundredth

part of the whole corn thrashed, or equal to a value of not less

than two millions sterling in Great Britain alone. In the

course of twenty years from the date of the patent, about three

hundred and fifty thrashing-mills were erected in East Lothian

alone, at an estimated outlay of nearly forty thousand pounds; and,

shortly after, it became generally adopted in England, and indeed

all over the civilised world.

We regret, however, to add, that Meikle did not reap those

pecuniary advantages from his invention, which a less modest and

more pushing man would have done. Pirates fell upon him on all

sides and deprived him of the fruits of his ingenuity, and even

denied him any originality whatever. When growing old and

infirm, Sir John Sinclair bestirred himself to raise a subscription

in his behalf; and a sum of £1,500 was collected, which was invested

for his benefit. Mr. Dempster, M.P., wrote to Sir John, when

on his charitable mission in 1809: "Should your tour in East Lothian

procure a suitable reward to the inventor of the thrashing-machine,

it will redound much to your and the country's honour; our heathen

ancestors would have assigned a place in heaven to Meikle." [p.247]

Smeaton knew Meikle intimately, and frequently met him in

consultation respecting the arrangements of the Dalry Mills, near

Edinburgh, and other works; and he was accustomed to say of him,

that if he had possessed but one-half the address of other people,

he would have rivalled all his contemporaries, and stood forth as

one of the first mechanical engineers in the kingdom.

Among the various improvements which this ingenious mechanic

introduced in millwork, were those in the sails of windmills.

Before his time, these machines were liable to serious accidents on

the occurrence of a sudden gale, or a shift in the direction of the

wind. By Meikle's contrivance, the machinery was so arranged

that the whole sails might be taken in or let out in half a minute,

according as the wind required, by a person merely pulling a rope

within the mill. The machinery was at the same time kept in

more uniform motion, and all danger from sudden squalls completely

avoided.

His additions to the power of water-wheels were also

important, and on one occasion proved effectual in carrying out an

improvement of a remarkable character in the county of Perth.

This was neither more nor less than washing away into the river

Forth some two thousand acres of peat moss, and thus laying bare an

equivalent surface of arable land, now amongst the most valuable in

the Carse of Stirling.

The Kincardine Moss was situated between the rivers Teith and

Forth. It was seven feet in depth, laid upon a bottom of rich

clay. In 1766 Lord Kaimes, who entered into possession of the

Blair Drummond estate, to which it belonged, determined, if

possible, to improve the tract of land; and it occurred to him that

the easiest plan would be to wash the moss entirely away. But

how was this to be done? The river Teith, which was the only

available stream at hand, was employed to drive a corn-mill.

But Lord Kaimes saw that it would answer his intended purpose if he

could get possession of it. He accordingly made an arrangement

by which he became owner of the mill, which he pulled down, and then

turned the mill-stream in upon the moss. Labourers were set to

work to cut away the stuff, which was thrown into the current, and

much of it thus washed away. But the process was slow, and the

clearing of the land had not advanced very far by the year 1783,

when Lord Kaimes's son, Mr. Home Drummond, entered into possession

of the estate. A thousand acres still remained, which he

determined to get rid of, if possible, in a more summary manner than

his predecessor had done.

Mr. Drummond consulted several engineers—amongst others Mr.

Whitworth, a pupil of Brindley's—who recommended one plan; but

George Meikle, a millwright at Alloa, the son of Andrew, proposed

another, the invention of his father; and Mr. Whitworth, with much

candour and liberality, at once acknowledged its superiority to his

own, and urged Mr. Drummond to adopt it. The invention

consisted of a newly-contrived wheel, 28 feet in diameter and 10

feet broad, for raising water in a simple, economical, and powerful

manner, at the rate of from 40 to 60 hogsheads a minute; and it was

necessary to raise it about 17 feet, in order to reach the higher

parts of the land. The machinery, on being erected, was set to

work, and with such good results, that in the course of a very few

years, four miles of barren moss was completely washed away, and the

district was shortly after covered with thriving farmsteads, as it

remains to this day.

Meikle was a thorough mechanical inventor, and, wherever he

could, he endeavoured to save labour by means of machinery.

Stories are still told in the neighbourhood in which he lived, of

the contrivances he adopted with this object in his own household,

some of which were of an amusing character. One day a woman

came to the mill to get some barley ground, and was desired to sit

down in the cottage hard by, until it was ready. With the

first sound of the mill-wheels the cradle and churn at her side

began to rock and to churn, as if influenced by some supernatural

agency. No-one was in the house besides herself at the time,

and she rushed from it, frightened almost out of her wits.

Such incidents as these brought an ill name on Andrew, and the

neighbours declared of him that he was "no canny."

He was often sent for to great distances, for the purpose of

repairing pumps or setting mills to rights. On one occasion,

when he undertook to supply a gentleman's house with water, so many

country mechanics had tried it before and failed, that the butler

would not believe Meikle when he told him he would send in the water

next day. Meikle, however, told him to get everything ready.

"It will be time enough to get ready," said the incredulous butler,

"when we see the water." Meikle pocketed the affront, but set

his machinery to work early next morning; and when the butler got

out of bed he found himself up to his knees in water, so

successfully had the engineer performed his promise.

Meikle lived to an extreme old age, and was cheerful to the

last. He was a capital player on the Northumbrian bagpipes.

The instrument he played on was made by himself, the chanter being

formed out of a deer's shank-bone. When ninety years old, at

the family gatherings on "Auld Hansel Monday," his six sons and

their numerous families danced about him to his music. He died

in 1811, in his ninety-second year, and was buried in Prestonkirk

churchyard, close by Houston Mill, where a simple monument is

erected to his memory, bearing the following inscription:—

"Beneath this Stone are deposited the remains of the

late Andrew Meikle, civil engineer at Houston Mill, who died in the

year 1811, aged 92 years. Descended from a race of ingenious

mechanics, to whom the country for ages had been greatly indebted,

he steadily followed the example of his ancestors, and, by inventing

and bringing to perfection a machine for separating corn from the

straw (constructed upon the principles of velocity, and furnished

with fixed beaters or skutchers), rendered to the agriculturists of

Britain and of other nations, a more beneficial service than any

hitherto recorded in the annals of ancient or modern science." [p.251]

Such was the master who first trained and disciplined the

skill of John Rennie, and implanted in his mind an enthusiasm for

mechanical excellence. Another of his apprentices was a man

who exercised almost as great an influence on the progress of

mechanics, through the number of first-rate workmen whom he trained,

as Rennie himself did in the art of engineering. We allude to

Peter Nicholson, an admirable mechanic and architect, author of

numerous works on carpentry and architecture, which to this day are

amongst the best of their kind. We now pursue the career of

Andrew Meikle's most distinguished pupil.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

RENNIE BEGINS BUSINESS AS MILLWRIGHT AND

ENGINEER.

WE have now seen

how Rennie was educated—at school and workshop—and how the ingenious

Andrew Meikle was not the least useful of his schoolmasters.

On Rennie's return to Phantassie, after conducting for a time

the burgh school at Dunbar, he continued to pursue his studies,

especially in mathematics, mechanics, and natural philosophy.

He also frequented the workshop of his friend Meikle, assisting him

with his plans, and taking an especial interest in the invention of

the thrashing-machine, which Meikle was at that time engaged in

bringing to completion. He was also entrusted to superintend

the repairs of cornmills in cases where Meikle could not attend to

them himself; and he was sent, on several occasions, to erect

machinery at a considerable distance from Prestonkirk. Rennie

thus gained much valuable experience, and acquired some confidence

in his own powers.

He next began to undertake millwork on his own account.

His brother George was already well known as a clever farmer, and

the connection helped him to considerable employment. Meikle

was also ready to recommend him in cases where he could not accept

the work offered him in distant counties; and hence, as early as

1780, when Rennie was only nineteen years of age, we find him

employed in fitting up the new mills at Invergowrie, near Dundee.

He designed the machinery as well as the buildings for its

reception, and superintended them to their completion.

His next work was to prepare an estimate and design for the

repairs of Mr. Aitcheson's flour-mills at Bonnington, near

Edinburgh. Here he employed cast-iron pinions, instead of the

wooden trundles formerly used—one of the first attempts made to

introduce iron into this portion of the machinery of mills.

These, his first essays in designs, were considered very

successful, and they brought him both money and fame. Business

flowed in upon him, and before the end of his nineteenth year he had

abundant employment. But he had no intention of confining

himself to the business of a country millwright; for he aimed at a

higher professional position, and a still wider field of work.

Desirous, therefore, of advancing himself in scientific culture, and

prosecuting those studies in mechanical philosophy which he had

begun at Phantassie and pursued at Dunbar, he determined to enter

himself a student at the University of Edinburgh. In taking

this step he formed the resolution—by no means unusual amongst young

men of even a humbler class—of supporting himself at college

entirely by his own labour. He was persuaded that by diligence

and assiduity he would be enabled to earn enough during the summer

months to pay for his winter's instruction and maintenance; and his

habits being frugal and his style of living very plain, he was

enabled to prosecute his design without difficulty.

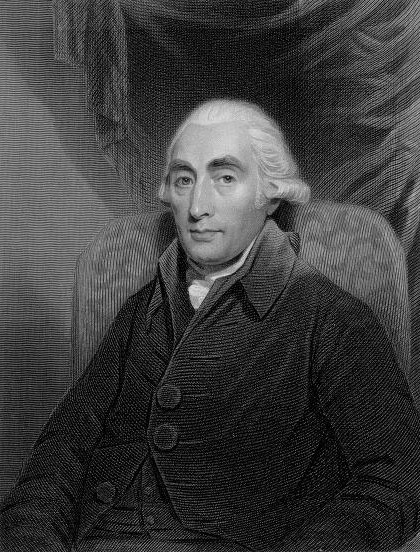

John Robison (1739-1805), Scottish physicist and

inventor,

and professor of philosophy at the University of Edinburgh.

Picture (by Sir Henry Raeburn) Wikipedia.

He accordingly matriculated at Edinburgh in November, 1780,

and entered the classes of Dr. Robison, Professor of Natural

Philosophy, and of Dr. Black, Professor of Chemistry both men of the

highest distinction in their respective walks. Robison was an

eminently prepossessing person, frank and lively in manner, full of

fancy and humour, and, though versatile in talent, a profound and

vigorous thinker. His varied experience of life, and the

thorough knowledge which he had acquired of the principles as well

as the practice of the mechanical arts, proved of great use to him

as an instructor of youth. The state of physical science was

then at a very low ebb in this country, and the labours of

Continental philosophers were but little known even to those who

occupied the chairs in our Universities; the results of their

elaborate researches lying concealed in foreign languages, or being

known, at most, to a few inquirers more active and ardent than their

fellows; while the general student, mechanic, and artisan, were left

to draw their principal information from daily observation and

experience.

Joseph Black (1728-99), Scottish physician,

physicist, and chemist

known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon

dioxide.

Picture (from Sir Henry Raeburn) Wikipedia.

Under Dr. Robison the study of natural philosophy became

invested with unusual significance and importance. The

range of his knowledge was most extensive: he was familiar with the

whole circle of the accurate sciences, and in imparting information,

his understanding seemed to work with extraordinary energy and

rapidity. The labours of others rose in value under his hands,

and new views and ingenious suggestions never failed to enliven his

prelections on mechanics, hydrodynamics, astronomy, optics,

electricity, and magnetism, the principles of which he unfolded to

his pupils in language at once fluent, elegant, and precise.

Lord Cockburn, in his 'Memorials,' remembers him as somewhat

remarkable for the humour in which he indulged in the article of

dress. "A pigtail so long and thin that it curled far down his

back, and a pair of huge blue worsted hose, without soles, and

covering the limbs from the heel to the top of the thigh, in which

he both walked and lectured, seemed rather to improve his wise

elephantine head and majestic person." He delighted in holding

familiar intercourse with his pupils, whom he charmed and elevated

by his brilliant conversation and his large and lofty views of life

and philosophy. Rennie was admitted to his delightful society,

and to the close of his career he was accustomed to look back upon

the period which he spent at Edinburgh as amongst the most

profitable and instructive in his life.

During his college career, Rennie carefully read the works of

Emerson, Switzer, Maclaurin, Belidor, and Gravesande, allowing

neither pleasure nor society to divert him from his studies.

As a relief from graver topics, he set himself to learn the French

and German languages, and was shortly enabled to read both with

ease. His recreation was mostly of a solitary kind, and,

having a little taste for music, he employed some of his leisure

time in learning to play upon various instruments. He acquired

considerable proficiency on the flute and the violin, and he even

went so far as to buy a pair of bagpipes and learn to play upon

them,—though the selection of such an instrument probably does not

say much for his musical taste. When he left Edinburgh and

entered seriously upon the business of life, the extensive nature of

his engagements so completely occupied his time, that in a few years

flute, fiddle, and bagpipes, were laid aside altogether.

During the three years that he attended college our student

was busily occupied in the summer vacation—extending from the

beginning of May to the end of October in each year in executing

millwork in various parts of the country. Amongst the

undertakings on which he was thus employed, may be mentioned the

repair or construction of the Kirkaldy and Bonnington Flour Mills,

Proctor's Mill at Glammis, and the Carron Foundry Mills. When

not engaged on distant works, his brother George's house at

Phantassie was his headquarters, where he prepared his designs and

specifications. He had the use of the workshop at Houston Mill

for making such machinery as was intended for erection in the

neighbourhood; but when he was employed at some distant point, the

work was executed in the most convenient places he could find for

the purpose. There were as yet no large manufactories in

Scotland where machinery of an important character could be turned

out as a whole; the millwright being under the necessity of sending

one portion to the blacksmith, another to the founder, another to

the brass-smith, and another to the carpenter—a state of things

involving a great deal of trouble, and risk of failure,—but which

was eminently calculated to familiarise our young engineer with the

details of every description of work required in the practice of his

profession.

His college training having ended in 1783, and being desirous

of acquiring some knowledge of English engineering practice, Rennie

set out on a tour through the manufacturing districts.

Brindley's reputation attracted him first towards Lancashire, for

the purpose of inspecting the works of the Bridgewater Canal.

There being no stage coaches convenient for his purpose, he

travelled on horseback, and in this way he was enabled readily to

diverge from his route for the purpose of visiting any structure

more interesting than ordinary. At Lancaster he inspected the

handsome bridge across the Lune, then in course of construction by

Mr. Harrison, afterwards more celebrated for his fine work of

Chester Gaol. At Manchester he examined the works of the

Bridgewater Canal; and at Liverpool he visited the docks then in

progress.

Proceeding by easy stages to Birmingham, then the centre of

the mechanical industry of England, and distinguished for the

ingenuity of its workmen and the importance of its manufactures in

metal, he took the opportunity of visiting the illustrious Boulton

and Watt at Soho. His friend, Dr. Robison, had furnished him

with a letter of introduction to James Watt, who received the young

engineer kindly and showed him every attention; and a friendship

then began which lasted until the close of Watt's life.

The condensing-engine had by this time been brought into an

efficient working state, and was found capable not only of pumping

water—almost the only purpose for which it had originally been

intended—but of driving machinery, though whether with advantageous

results was still a matter of doubt. Thus, in November, 1782,

Watt wrote to his partner Boulton, "There is now no doubt but that

fire-engines will drive mills, but I entertain some doubts whether

anything is to be got by them." About the beginning of March,

1783, however, a company was formed in London for the purpose of

erecting a large corn-mill, to be driven by one of Boulton and

Watt's steam-engines, and the work was in progress at the time that

Rennie visited Soho. Watt had much conversation with his

visitor on the subject of corn-mill machinery, and was gratified to

learn the extent and accuracy of his information. He seems to

have been provoked beyond measure by the incompetency of his own

workmen. "Our millwrights," he wrote to his partner, "have

kept working, working, at the corn-mill ever since you went away,

and it is not yet finished; but my patience being exhausted, I have

told them that it must be at an end to-morrow, done or undone.

There is no end of millwrights once you give them leave to set about

what they call machinery; here they have multiplied wheels upon

wheels until it has now almost as many as an orrery."

James Watt, F.R.S., (1736-1819), Scottish inventor

and mechanical engineer.

Watt himself had but little knowledge of millwork, and stood

greatly in need of some intelligent millwright to take charge of the

fitting up of the Albion Mills. Young Rennie seemed to him to

be a very likely person; but, with characteristic caution, he said

nothing to him of his intentions, but determined to write privately

to his friend Robison upon the subject, requesting particularly to

know his opinion as to the young man's qualifications for taking the

superintendence of such important works. Dr. Robison's answer

was decided; his opinion of Rennie's character and ability was so

favourable, and expressed in so confident a tone, that Watt no

longer hesitated; and he wrote to the young engineer, after he had

returned home, inviting him to undertake the supervision of the

proposed Albion Mills, so far as concerned the planning and erection

of the requisite machinery.

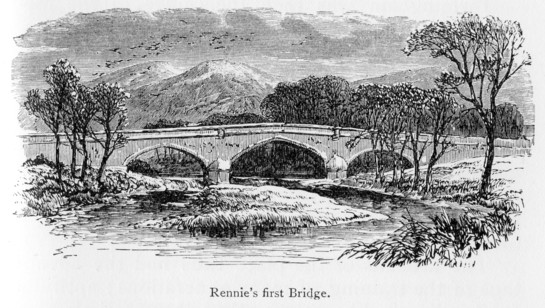

Watt's invitation found Rennie again in full employment.

He was engaged in designing and erecting mills and machinery of

different kinds. Among his earlier works, we also find him, in

1784, when only in his twenty-third year, occupied in superintending

the building of his first bridge—the forerunner of a series of

structures which have not been surpassed in any age or country.

His earliest bridge was erected for the trustees of the county of

Mid-Lothian, across the Water of Leith, near Stevenhouse Mill, about

two miles west of Edinburgh. It is the first bridge on the

Edinburgh and Glasgow turnpike-road.

Notwithstanding the extent of his engagements, and his

prospects of remunerative employment, Rennie looked upon the

invitation of Watt as a favourable opportunity for enlarging his

experience; and, after due deliberation, he replied accepting the

appointment. He proceeded, however, to finish the works he had

in hand; after which, taking leave of his friends at Phantassie, he

set out for Birmingham on the 19th of September, 1784. He

remained there for two months, during which he enjoyed the closest

personal intercourse with Watt and Boulton, and was freely admitted

to their works at Soho, which had already become the most important

of their kind in the kingdom.

Birmingham was then the centre of the mechanical industry of

England. For many centuries, working in metals had been the

staple trade of the place. Swords were made there in the time

of the ancient Britons. In the reign of Henry VIII., Leland

found "many smythes in the town that use to make knives and all

manner of cutting tools, and many loriners that make bittes, and a

great many nailers; so that a great part of the town is maintained

by smythes who have their iron and sea-coal out of Staffordshire."

The artisans of the place thus had the advantage of the

training of many generations; aptitude for handicraft, like every

other characteristic of a people, descending from father to son like

an inheritance. There was then no town in England where

mechanics were to be found so capable of satisfactorily executing

original and unaccustomed work, nor has the skill yet departed from

them. Though there are now many districts in which far more

machinery is manufactured than in Birmingham, the workmen of that

place are still superior to most others in executing machinery

requiring manipulative skill and dexterity out of the common track,

and especially in carrying out new designs. The occupation of

the people gave them an air of quickness and intelligence which was

quite new to strangers accustomed to the quieter aspects of rural

life. When Hutton entered Birmingham, he was especially struck

by the vivacity of the persons he met in the streets. "I had,"

he says, "been among dreamers, but now I was among men awake.

Their very step showed alacrity. Every man seemed to know and

prosecute his own affairs." He also adds, that men whose

former disposition was idleness no sooner breathed the air of

Birmingham than diligence became their characteristic.

Rennie did not stand in need of this infection being

communicated to him, yet he was all the better for his contact with

the population of the town. He made himself familiar with

their processes of handicraft, and, being able to work at the anvil

himself, he could fully appreciate the skill of the Birmingham

artisans. The manufacture of steam-engines at Soho chiefly

attracted his notice and his study. He had already made

himself acquainted with the principles as well as the mechanical

details of the steam-engine, and was ready to suggest improvements,

in a very modest way, even to Watt himself, who was still engaged in

perfecting his wonderful invention.

The partners thought that they saw in him a possible future

competitor in their trade; and in the agreement which they entered

into with him as to the erection of the Albion Mills, they sought to

bind him, in express terms, not only to abstain from interfering in

any way with the construction and working of the steam-engines

required for the mills, but to prohibit him from executing such work

upon his own account at any future period. Though ready to

give his word of honour that he would not in any way interfere with

Watt's patents, he firmly refused to bind himself to such

conditions; being resolved in his own mind not to be debarred from

making such improvements in the steam-engine as experience might

prove to be desirable. And on this honourable understanding

the agreement was concluded; nor did Rennie ever in any way violate

it, but retained to the last the friendship and esteem of both

Boulton and Watt.

On the 24th of November following, after making himself fully

acquainted with the arrangements of the engines by means of which

his machinery was to be driven, our engineer set out for London to

proceed with the designing of the millwork. It was also

necessary that the plans of the building—which had been prepared by

Mr. Samuel Wyatt, an architect of reputation in his day—should

undergo revision; and, after careful consideration, Rennie made an

elaborate report on the subject, recommending various alterations,

which were approved by Boulton and Watt, and forthwith ordered to be

carried into effect.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IV.

THE ALBION MILLS—MR. RENNIE AS ENGINEER.

WHEN Rennie

arrived in London in 1785, the country was in a state of serious

depression in consequence of the unsuccessful termination of the

American War. Parliament was engaged in defraying the heavy

cost of the recent struggle with the revolted colonies. The

people were ill at ease, and grumbled at the increase of the debt

and taxes. The unruly population of the capital could with

difficulty be kept in order. The police and local government

were most inefficient. Only a few years before, London had,

during the Gordon riots, been for several days in the hands of the

mob, and blackened ruins in different parts of the city still marked

the track of the rioters.

Though the largest city in Europe, the population of London

was scarcely more than a third of what it is now; yet it was thought

that it had become so vast as to be unmanageable. Its northern

threshold was at Hicks's Hall, in Clerkenwell. Somers Town,

Camden Town, and Tyburnia were as yet green fields; and Kensington,

Chelsea, Marylebone, and Bermondsey were outlying villages.

Fields and hedgerows led to the hills of Highgate and Hampstead.

The West End of London was a thinly-inhabited suburb. A wide

tract of marshy ground extended opposite Lambeth. The

westernmost building in Westminster was Mill-bank. Executions

were conducted in Tyburn fields, now known as Tyburnia, down to

1783. Oxford Street, from Princes Street eastward as far as

High Street, St. Giles's, had only a few houses on the north side.

"I remember it," says Pennant, "a deep hollow road and full of

sloughs, with here and there a ragged house, the lurking-place of

cutthroats; insomuch that I was never taken that way by night, in my

hackney-coach, to a worthy uncle's who gave me lodgings at his house

in George Street, but I went in dread the whole way."

Paddington was "in the country," and the communication with

it was kept up by means of a daily stage a lumbering vehicle, driven

by its proprietor—which was heavily dragged into the city in the

morning, down Gray's Inn Lane, with a rest at the Blue Posts,

Holborn Bars, to give passengers an opportunity of doing their

shopping. The morning journey was performed in two hours and a

half, "quick time," and the return journey in the evening in about

three hours.

Heavy coaches still lumbered along the country roads at

little more than four miles an hour. A new state of things

had, however, been recently inaugurated by the starting of the first

mail-coach on Palmer's plan, which began running between London and

Bristol on the 24th of August, 1784, and the system was shortly

extended to other places. Numerous Acts were passed by

Parliament authorising the formation of turnpike roads and the

erection of bridges. [p.264]

The general commerce of the country was also making progress.

The application of recent inventions in manufacturing industry gave

a stimulus to the general improvement, and this was further helped

by a succession of favourable harvests. The India Bill had

just been renewed by Pitt, and trade with India was brisk. A

commercial treaty with France was on foot, from which great things

were expected; but the outbreak of the Revolution, which shortly

after took place, put an end for a time to those hopes of fraternity

and peaceful trade in which it had originated. The Government

boldly interposed to check smuggling, and Pitt sent a regiment of

soldiers to burn the smugglers' boats laid upon Deal beach by the

severity of the winter, so that the honest traders might have the

full benefit of the treaty with France which Pitt had secured.

Increased trade flowed into the Thames, and ministers and monarch

indulged in drawing glowing pictures of prosperity.

When Pennant visited London in 1790, he found the river

covered with shipping, presenting a double forest of masts, with a

narrow avenue in mid-channel. The smaller vessels discharged

directly into the warehouses along the banks of the river, whilst

the India ships of large burden mostly lay down the river as far as

Blackwall, and discharged into lighters, which floated up their

cargoes to the city wharves. London as yet possessed no public

docks—only a few private ones, open to the river, of very limited

extent,—although Pennant speaks of Mr. Perry's dock and ship-yard at

Blackwall, on the eastern side of the Isle of Dogs, as "the greatest

private dock in all Europe!" Another was St. Saviour's,

denominated by Pennant "the port of Southwark," though it was only

thirty feet wide, and used for discharging barges of coal, corn, and

other commodities. There was also the Execution Dock at

Wapping, which witnessed the occasional despatch of seagoing

criminals, who were hanged on a gallows at low-water mark, and left

there until the tide flowed over their dead bodies.

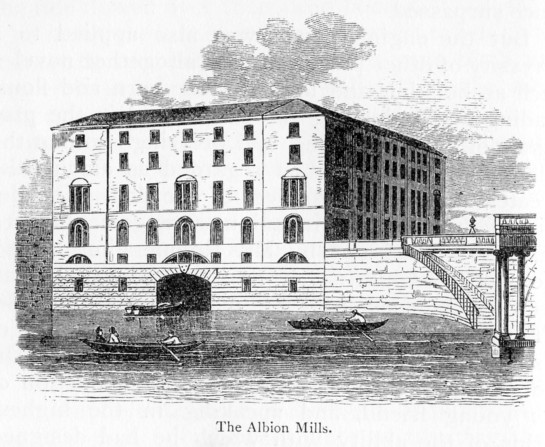

Among the commercial enterprises to which the increasing

speculation of the times gave birth, was the erection of the Albion

Mills. For the more convenient transit of corn and flour, as

well as to secure a plentiful supply of water for engine purposes,

it was determined to erect the new mills on the banks of the Thames,

near the south-east end of Blackfriars Bridge. Hand-mills,

which had in the first place been used for pounding wheat into

flour, had long since been displaced by water-mills and windmills;

and now a new agency was about to be employed, of greater power than

either —the agency of steam.

Fire-engines, or steam-engines, had heretofore been employed

almost exclusively to pump water out of mines; but the possibility

of adapting them to the driving of machinery having been suggested

to the inventive mind of James Watt, he set himself at once to the

solution of the problem, and the result was the engines for the

Albion Mills the most complete and powerful which had been produced

by the Soho manufactory. They consisted of two double-acting

engines, of the power of 50 horses each, with a pressure of steam of

five pounds to the superficial inch—the two engines, when acting

together, working with the power of 150 horses. They drove

twenty pairs of millstones, each four feet six inches in diameter,

twelve of which were usually worked together, each pair grinding ten

bushels of wheat per hour, by day and night if necessary. The

two engines working together were capable of grinding, dressing,

&c., complete, 150 bushels an hour—by far the greatest performance

achieved by any mill at that time, and probably not since surpassed.

But the engine power was also applied to a diversity of other

purposes, then altogether novel—such as hoisting and lowering the

corn and flour, loading and unloading the barges, and in the

processes of fanning, sifting, and dressing so that the Albion Mills

came to be regarded as among the greatest mechanical wonders of the

day. The details of these various ingenious arrangements were

entirely worked out by Mr. Rennie himself, and they occupied him

nearly four years in all, having been commenced in 1784, and

finished in 1788. Mr. Watt was so much satisfied with the

result of his employment of Rennie, that he wrote to Dr. Robison,

thanking him for his recommendation of his young friend, and

speaking in the highest terms of the ability with which he had

designed and executed the millwork and set the whole in Operation.

Amongst those who visited the new mills and carefully

inspected them was Mr. Smeaton, the engineer, who pronounced them to

be the most complete, in their arrangement and execution, which had

yet been erected in any country; and though naturally an

undemonstrative person, he cordially congratulated Mr. Rennie on his

success.

The completion of the Albion Mills, indeed, marked an

important stage in the history of mechanical improvements; and they

may be said to have effected an entire revolution in millwork

generally. Until then, machinery had been constructed almost

entirely of wood; it was clumsy, and involved great friction and

waste of power. Smeaton had introduced an iron wheel at Carron

in 1754, and afterwards in a mill at Belper, in Derbyshire—mere

rough castings, imperfectly executed, and neither chipped nor filed

to any particular form; and Murdock (James Watt's ingenious

assistant) had also employed cast-iron work to a limited extent in a