|

[Previous

Page]

Footnotes.

|

p.218 |

G. Buchan Hepburn's 'General View of the Agriculture

and Economy of East Lothian, 1794,' p.151. |

|

p.219-1 |

Dr. Carlyle, 'Autobiography,' p.326. |

|

p.219-2 |

Ibid. 303. |

|

p.220 |

There is every reason to believe that at a remote

period, Scotland had been well cultivated. The army of Edward

I. subsisted on the beans and pease which they found in the field,

when besieging Dirleton, East Lothian, in 1298; and from the old

chartularies of the Monastic establishments, it is clear that wheat

was cultivated to a considerable extent, at the same time.

Adda, mother of William the Lion, having founded a nunnery at the

Abbey, near Haddington, about the year 1178, endowed it with the

rents of certain lands in the neighbourhood. The rents were

paid in kind for the maintenance of the nuns, and consisted, amongst

other things, of four bolls of wheat and three bolls of oatmeal

yearly. And yet, at the beginning of the eighteenth century,

the production of wheat in Scotland had been entirely discontinued. |

|

p.221 |

Among these were Fletcher of Saltoun, the Earl of

Wigton, and others. For further remarks as to the decayed

state of Scotland at this time, see vol. iii. 'History of Roads,'

pp. 48-59. |

|

p.223 |

Appendix to 'Picture of Dumfries.' By John

MacDiarmid. Edinburgh, 1832. |

|

p.224 |

'Farmer's Magazine,' No. xxxiv., p.199. |

|

p.226 |

Besides the abundance of schools, and the excellence

of the education given, the moderation of the fees charged is worthy

of notice. Dr. Guthrie, in his 'Autobiography,' mentions the

schools at Brechin, where he was educated some sixty years ago.

First, he was taught at a private school, of which the late Dr.

McCrie was the teacher. "Besides this school," he says, "there

were two others in Brechin where Latin and Greek, French and

Mathematics, were taught. One of these was endowed from

property belonging in Roman Catholic times to the Knights Templars,

who had a preceptory there. The other was the parish school.

Both were conducted by 'preachers,' or licentiates of the Church of

Scotland—university men who had spent at least eight years at

college. Both prepared young men for the university, teaching

them, besides the more common branches of education, Algebra,

Euclid, French, Latin, Greek, and all for five shillings a quarter!

That may astonish people now-a-days. But so it was; and the

bursaries which a large proportion of these pupils won by open

competition at the universities of St. Andrews and Aberdeen, while

the means of their support there, proved the goodness of the

teaching they got for this small sum. The result of this cheap

and efficient education was that the sons of many poor and humble

people pulled their way up to honourable positions in life, while

the parents had not their self-respect and feelings of independence

lowered by owing the superior education of their children to others

than themselves." ('Autobiography,' pp. 33-34.) |

|

p.227 |

A writer, in the Scotch Farmer's Magazine for

1810, makes the following observations:—"During the last fifty years

Scotland has made rapid progress in agriculture, architecture,

navigation, and commerce; and if in some she has excelled her

neighbours, it may perhaps be ascribed to that wholesome and useful

system of parochial education, which was bequeathed to her children

by the last Parliament which she ever assembled as an independent

kingdom. The elements of learning, consisting of reading,

writing, and accounts, though seemingly superficial attainments,

have nevertheless, been of immense value to the people. They

have enabled them to comprehend, adopt, and improve to the utmost,

every new branch of science, as soon as it sprung up in any corner

of Europe: and there is no circumstance so peculiar in the

possession of a little knowledge, as the desire which it

communicates, and the capacity which it bestows, of obtaining still

more." |

|

p.228 |

Amongst George Rennie's illustrious visitors in his

later years was the Grand Duke Nicholas (afterwards Emperor) of

Russia, who stayed several nights at Phantassie, and during the time

was present at the celebration of a "hind's wedding." |

|

p.233 |

'Essays on the Trade, Commerce, Manufactures, and

Fisheries of Scotland.' |

|

p.236 |

It would seem that the ancestors of Meikle were held

in esteem as ingenious workmen for generations; the Scots Parliament

having, in 1686, passed a special Act for the encouragement of John

Meikle, founder, who, it appears was the first person to introduce

the art of iron-founding into Scotland. |

|

p.239-1 |

The Marquis of Tweeddale introduced the turnip into

the county in 1740; the Earl of Haddington and Mr. Walker of

Beanston, first adopted the system of fallowing land and sowing

broad clover and rye-grass. Lord Eubank and Sir Hew

Dalrymple divided between them the merit of inventing or introducing

the practice of under-draining; and Sir George Suttie first employed

the Norfolk system of rotation of crops. |

|

p.239-2 |

Brown on 'Rural Affairs.' |

|

p.240 |

See Adam Smith's 'Wealth of Nations,' Book II., Chap.

2. |

|

p.241 |

Patent No. 896. The name of Robert Mackell

(employed with James Watt in the survey of the "ditch canal" through

Perthshire—see Life of Smeaton) was associated with that of Meikle

in this patent; Mackell probably finding the money, and Meikle the

brains. |

|

p.242 |

Afterwards Sir Francis Kinloch. |

|

p.243 |

The following is a literal copy of the memorandum

which was drawn up and signed on the occasion:—

"Know Mill, 14th Feb., 1778.—We whose names are subjoined, desired

by Andrew Meikle to witness an experiment of his threshing machine,

mett this day, and after one hour's performance of said machine,

with the assistance of one man to feed in and carry of the straw,

dight and measured up one boll, and two forpets barley being of meen

qualitie, We are of opinion that a Man, in the ordinary way of

threshing, could not threshed abuve five, or 6 firlots at most, in

one day. The machine being simple, we suppose one horse may

worke it without an aditional man. The saving most be

considerable.

|

"(Signed)

John Dudgeon,

Tenent in Tyningham

Robert Dick,

Tenent in Hedderwik,

George

Rennie, Tenent in Fantase,

William

Wilson, Tenant in Peastown

William

Craig, Tyningham." |

|

|

p.244 |

'A Reply to an Address to the Public, but more

particularly to the Landed Interest of Great Britain and Ireland, on

the subject of the Threshing Machine.' By John Sheriff.

Edinburgh 1811. |

|

p.246 |

Patent No. 1645: "Machine for separating Corn from

Straw." |

|

p.247 |

'Memoirs of Sir John Sinclair,' vol. ii. p.99. |

|

p.251 |

It is remarkable that Scotch biography should be

altogether silent respecting this ingenious and useful workman.

In the most elaborate of the Scotch biographical collections—that of

Robert Chambers, in four large volumes—not a word occurs relating to

Meikle. An article is devoted to Mickle, the translator of

another man's invention in the shape of a poem, the 'Lusiad;' but

the name of the inventor of the thrashing-machine is not even

mentioned; affording a singular illustration of the neglect which

this department of biography has heretofore experienced, though it

has been by men such as Meikle, and not by poets, that this country

has in a great measure been made what it is. |

|

p.264 |

In the interval between 1784 and 1792, not fewer than

302 Acts were passed authorising the construction of new roads and

bridges, 64 authorising the formation of canals and harbours, and

still more numerous Acts for carrying out measures of drainage,

enclosure, paving, and other local improvements—a sufficient

indication of the industrial activity of the nation at that time. |

|

p.269 |

Shortly after the completion of these mills, Mr.

Rennie was largely consulted on the subject of machinery of all

kinds. The Corporations of London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Perth,

and other places, took his advice as to flour-mills.

Agriculturists consulted him about thrashing-mills, millers about

grinding-mills, and manufacturers and distillers respecting the

better arrangement of their works. In July, 1798, he was

called upon to examine the machinery and arrangements at the Royal

Mint on Tower Hill. The result was, the construction of an

entire new mint, worked by steam-power, with improved rolling,

cutting out, and stamping machinery, after Mr. Rennie's designs.

The new machinery was introduced between the years 1806 and 1810.

The cutting-out and stamping-machines were the invention of the late

Matthew Boulton, of Soho, but the machinery was by Rennie. On

one occasion, in 1819, a million of sovereigns was turned out in

eight days! During the great silver coinage in 1826, the eight

presses turned out, for nine months, not less than 247,696 pieces

per day, the rolling going on day and night, and the stamping for

fifteen hours out of every twenty-four. Mr. Rennie also

supplied the machinery for the mints at Calcutta and Bombay; that

erected at the former place being capable of turning out 200,000

pieces of silver in every eight hours. |

|

p.272-1 |

His first place of business was at Old Jamaica Wharf,

Upper Ground Street, Lambeth. |

|

p.272-2 |

Ed.—Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, F.R.S.

(1753-1816) was a British statesman, scientist and inventor, among

his inventions being the printing press (ca. 1800) which bears his

name. In it, Stanhope retained the conventional screw for

applying pressure to the work, but separated it from the spindle and

bar, inserting a system of compound levers between them. The effect

of several levers acting upon each other was to increase

considerably the power applied resulting in sharper impressions. |

|

p.273 |

He adopted paddles, placed under the quarters of the

vessel, which were made to open and shut like the feet of a duck. |

|

p.274 |

Ed.—The Kennet & Avon Canal was opened between Newbury and Bath

in 1810 but (in common with many other British canals) the coming of

railways—in this case the opening of the Great Western Railway in

1841—removed much of the traffic and the canal went into decline,

falling into

disuse in the 1950s when a stoppage at Burghfield made it impassable

and large sections of the canal were closed due of poor lock

maintenance. However, in 1956 The

Kennet and Avon Canal Trust successfully petitioned against its

legal closure and, following the formation of the British

Waterways Board in 1963, restoration work commenced. The fully

restored canal (the first to be grade I listed) was

re-opened by HM The Queen on 8 August 1990.

The complete navigation runs from High Bridge, Reading, where it joins the River Thames, to

the floating harbour at Bristol. The original Kennet

and Avon Canal linked the River Kennet at Newbury to the

River Avon at Bath (57 miles); however, the "navigation" extends between the

River Thames at Reading and the Floating Harbour at Bristol (87

miles) using

the earlier improved river navigations of the River Kennet, between

Reading and Newbury, and River Avon between Bath and Bristol. |

|

p.276 |

Ed.—Rennie's Avoncliffe Aqueduct was opened

1801. It comprises three arches, and is 110 yards long. Its central

elliptical arch is of 60 ft span with two side arches each

semicircular and of 34 ft span, all with V-jointed arch stones. The

spandrel and wing walls are built in alternate courses of ashlar

masonry, and rock-faced blocks. Throughout its life the central span

gave structural problems and has been repaired many times. |

|

p.281-1 |

The following canal works of Mr. Rennie may be

mentioned—The Aberdeen and Inverurie, 12 miles long, laid out and

constructed by him in 1796-7; the Calder Reservoirs and improvement

of the Trent and Mersey Canal at Rudyard Valley, near Leek, 1797-8;

a branch of the Grand Trunk Canal to Henley, with a railway

connecting it with the manufactories. He also made elaborate

reports on the Leominster Canal (1798); on the Chelmer and

Blackwater Navigation; Somersetshire and Dorsetshire Canal;

Horncastle Navigation; River Foss Navigation; Polbrook Canal (1799);

Rotherhithe and Croydon; Thames and Medway (1800); and River Lea

Navigation (1804). Among the works surveyed by him, but which

were not carried out, were these: a canal through the Weald of Kent

(1802-3); a ship-canal between the Thames and Portsmouth (1803); a

ship canal between the Medway and Portsmouth (1810); a ship-canal

from Chichester Harbour to Chichester (1804); and a ship-canal from

Bristol to the English Channel (1811). He was also employed by

the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal Company, the Birmingham Canal

Company, and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company, as their

consulting engineer; and various important improvements in these

navigations were carried out by his advice and under his

superintendence. |

|

p.281-2 |

Ed.―the Lune Aqueduct, completed in 1797,

carries the Lancaster Canal over the River Lune to the east of the

City of Lancaster. One of Rennie's finest works, the aqueduct is

classical in style with rusticated masonry and curved wingwalls, and

is over 600ft long—unsurprisingly it has a Grade I preservation listing.

But Smiles fails to mention that the Canal had an unfortunate

history, which can be attributed to the Lune Aqueduct..

Rennie surveyed a route from Wigan

and Preston to Kendal, during 1791, mapping out a fine example of a

'contour' canal (one that follows the lie of the land and does not

need locks). Construction

of the Lune Aqueduct was commenced in 1794 ahead of the building of

the canal that connected to it. But at £48K its construction proved so expensive that there was no money left to build the

matching aqueduct over the

River Ribble at Preston necessary to connect to the national canal network. Thus the Lancaster Canal remained in

splendid isolation for over 200 years. It did, however, provide a

waterway between Preston and Tewitfield, which was later extended

north to Kendal (1819), while a short branch to Glasson Dock was

opened (1826) to carry the canal down to the sea via a flight of

locks.

Declining traffic during the 1950s led to the Canal being partly abandoned.

Today only

the section from Preston to Tewitfield near Carnforth—42 of the

original 57 miles north of Preston—is open to navigation, the route north of Tewitfield having been severed by

the M6 Motorway and, in places, filled in. However, in 2002 a link was

opened to connect the previously isolated Canal to the rest of the national network via a canalisation of the Savick Brook. The new link skirts the outskirts of Preston and flows

into the River Ribble. From there it uses the River Douglas to

connect to the national network via the Leeds and Liverpool Canal's

Rufford Branch. |

|

p.285 |

'Journal of Royal Agricultural Society,' 1847, vol.

viii. p.124. |

|

p.287 |

A writer in an old number of the 'Universal Magazine'

(published in 1773) describes a conversation with a

cadaverous-looking man whom he encountered in the Fens, and condoled

with on his forlorn and meagre appearance. The man rejoined,

that he had never been better since he had buried the first of his

nine wives. "Nine wives?" "Yes, nine wives!" was the

reply. The man explained that the Fen men were accustomed to

seek their wives in the upland country, selecting those who had a

little money; and as living in the Fens was certain death to

strangers during the fever season, many of the Fen men thus

contrived to accumulate a good deal of money. But the Fen

districts have long since ceased to possess this peculiar advantage,

for they are now as healthy as the upland districts themselves. |

|

p.294 |

Report, dated the 7th of April, 1800. |

|

p.296-1 |

See the Map in vol. i. of the 'Fens as Drained in

1830;' p.51. |

|

p.296-2 |

Ed.—the Witham Navigable Drains are located in

Lincolnshire, and are part of a much larger drainage system managed

by the Witham Fourth District Internal Drainage Board. In

total there are over 438 miles of drainage ditches, of which under

60 miles are navigable. Navigation is normally only possible

in the summer months, as the drains are maintained at a lower level

in winter, and are subject to sudden changes in level as a result of

their primary drainage function, which can leave boats stranded.

Access to the drains is from the River Witham at Anton's Gowt Lock. |

|

p.297 |

The following letter, written by a Lincolnshire

gentleman, in January, 1807, appears in the 'Farmer's Magazine' of

February in that year:—"Our fine drainage works begin now to show

themselves, and in the end will do great credit to Mr. Rennie, the

engineer, as being the most complete drainage that ever was made in

Lincolnshire, and perhaps in England. I have been a

commissioner in many drainages, but the proprietors never would

suffer us to raise money sufficient to dig deep enough through the

old enclosures into the sea before; and, notwithstanding the

excellency of Mr. Rennie's plan, we have a party of uninformed

people, headed by a little parson and magistrate, who keep

publishing letters in the newspapers to stop the work, and have

actually petitioned Sir Joseph Banks, the lord of the manor, against

it; but he answered them with a refusal, in a most excellent way . .

. . I think Mr. Rennie's great work will promote another general

improvement here, which is, to deepen and enlarge the river Witham

from the sea, through Boston and Lincoln to the Trent, so as to

admit of a communication for large vessels, as well as laying the

water so much below the surface of the land as to do away with the

engines. We have got an estimate, and find the cost may be

about £100,000." |

|

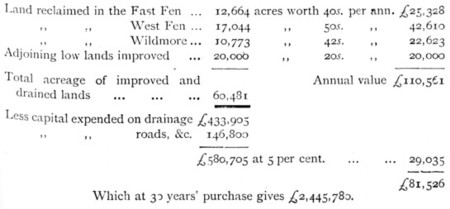

p.299 |

Mr. Bower's estimate was as follows:—

|

|

p.300 |

In his admirable Report dated the 6th October, 1800,

Mr. Rennie pointed out that the lines of direction in which the

rivers Welland and Witham entered the Wash tended to the silting-up

of the channels of both, and he suggested that the two river outlets

should be united in one, and diverted into the centre of the Wash,

at Clayhole, which would at the same time greatly increase the

depth, and enable a large area of valuable land to be reclaimed for

agricultural purposes. This suggestion has since been

elaborated by Sir John Rennie*, whose plan of 1837, when fully

carried out, will have the effect of greatly improving the outfalls

of all the rivers entering the great Wash—the Ouse, the Nene, the

Welland, and the Witham—and the drainage of the low level lands

depending upon them, comprising above a million of acres, and

ultimately gaining from the Wash between 150,000 and 200,000 acres

of rich new land, or equal to the area of a good-sized county. In

the Wash of the Nene, called Sutton Wash, 4000 acres have already

been reclaimed after this plan—the land, formerly washed by the sea

at every tide, being now covered with rich cornfields and

comfortable farmsteads. It was at this point that King John's

army was nearly destroyed when crossing the sands before the

advancing tide.

* Ed.—Sir John Rennie (1794-1874) was the

second son of engineer John Rennie and brother of George Rennie. |

|

p.301 |

Among other important works of the same kind executed

by Mr. Rennie, but which it would be tedious to describe in detail,

was the reclamation (in 1807) of 23,000 acres of fertile land in the

district of Holderness, near Hull. He was extensively employed

to embank lands exposed to the sea, and succeeded (in 1812) in

effectually protecting the thirty miles of coast extending from

Wainfleet to Boston, and thence to the mouths of the rivers Welland

and Glen. Two ears later (in 1814) he, in like manner,

furnished a plan, which was carried out, for protecting the Earl of

Lonsdale's valuable marsh land on the south shore of the Solway

Frith. |

|

p.305 |

Thompson's 'History of Boston,' 1856, p. 639. |

|

p.308 |

Dr. Robison was the first contributor to the 'Encyclopedia'

who was really a man of science, and whose articles were above the

rank of mere compilations. He sought information from all

quarters—searched the works of foreign writers, and consulted men of

practical eminence, such as Rennie, to whom he could obtain

access—and hence an extraordinary value was imparted to his

articles. |

|

p.312 |

The great arch of 450 feet was to be supported on two

stone piers, each 75 feet thick, the springing to be 100 feet above

high water. There were to be arches of stone on the Caernarvon

side to the distance of about 156 yards, and on the Anglesea side to

the distance of about 284 yards, making the total length of the

bridge, exclusive of the wing walls, about 640 yards. The

estimated cost of the whole work and approaches was £268,500.

The point at which the bridge was recommended to be thrown across

was, either opposite Inys-y-Moch island, on which one of the main

piers would rest, or at the Swilly rocks, about 800 yards to the

eastward; but, on the whole, he preferred the latter site. He

also sent in a subsequent design, showing an iron arch on each side

of the main one of 350 feet span, in lieu of masonry, with other

modifications, by which the dimensions of the main piers were

reduced, and the estimate somewhat lessened. Other plans were

prepared and submitted, embodying somewhat similar views, the

prominent idea in all of them being the spanning of the Straits by a

great cast-iron arch, the crown of which was to be 150 feet above

the sea at high water. The plans and evidence on the subject

are to be found set forth in the 'Reports from Committees of the

House of Commons on Holyhead Roads' (1810-22), ordered to be printed

25th July, 1822. |

|

p.313 |

John Rennie designed Boston's first "Town Bridge", in

one arch of cast iron of 86 feet span. The bridge was

"re-built" in 1913 to a design by John Webster—I've been unable to

discover why. |

|

p.314 |

Among his minor works may be mentioned the bridge

over the stream which issues out of Virginia Water and crosses the

Great Western Road (erected in 1805); Darlaston Bridge across the

Trent, in Staffordshire (1805); the timber and iron bridge over the

estuary of the Welland at Fossdyke Wash, about nine miles below

Spalding (1810); the granite bridge of three arches at New Galloway,

on the line of the Dumfries and Portpatrick Road (1811); a bridge of

five arches across the Cree at Newton Stewart (1812); the cast-iron

bridge over the Goomtee at Lucknow, erected after his designs in

1814, and frequently referred to in the military operations for the

relief of that city a few years ago; Wellington Bridge, over the

Aire, at Leeds (1817); Isleworth Bridge (1819); a bridge of three

elliptical arches of 75 feet span each, at Bridge of tarn,

Perthshire (1819); Cramond Bridge, of eight semicircular arches of

50 feet span, with the roadway 42 feet above the river (1819); and

Ken Bridge, New Galloway, of five stone arches, the centre go feet

span (1820). An adventure of some peril attended Mr. Rennie's

erection of the bridge at Newton Stewart. He happened to visit

the works on one occasion during a heavy flood, which swept down the

valley with great fury; and the passage of the ferry was thus

completely interrupted. Mr. Rennie and his son (the present

Sir John) were consequently unable to cross over to Newton Stewart.

About 11 p.m. the violence of the storm had somewhat abated, and the

moon came out, though obscured by the clouds which drifted across

her face. Mr. Rennie went out at that late hour to look at the

bridge works, and even to try whether he might not reach the other

side by crossing the timber platform by means of which the works

were being carried on. There was a gangway of only two planks

from pier to pier on the eastern side, and this he safely crossed.

The torrent was still raging furiously beneath, shaking the frail

timbers of the scaffolding. As Mr. Rennie was about to place

his foot on the plank which led to the third pier, his son observed

the framework tremble, and pulled his father back, just in time to

see the whole swept into the stream with a tremendous crash.

Fortunately the planking still stood across which they had passed,

and they succeeded in retracing their steps in safety. The

bridge was finished and opened during the summer of 1814. |

|

p.316 |

In their report on this design, Mr. Rennie and his

colleague observed:—"We should not have thought it necessary to

quote the production of a foreign country for the sake of showing

the practicability of constructing arches of 130 feet span, had we

not been led to it by the exact similarity of the designs, and by

the principle which is therein adopted of the compound curve;

because our own country affords examples of greater boldness in the

construction of arches than that of Neuilly. There is a bridge

over the river Taff, in the county of Glamorgan, of upwards of 135

feet span, with a rise not exceeding 32 feet, and what is more

remarkable is, that the depth of the arch-stones is only 30 inches;

so that in fact that bridge far exceeds in boldness of design that

of Neuilly." [See the Memoir of William Edwards at p. 86.]

After some observations as to the importance and necessity of making

a bridge in such a situation at the bend of the river, with as large

arches as possible, to accommodate the navigation and present as

little obstruction as possible to the rise and fall of the water,

they proceeded:—"We confess we do not wholly approve of M.

Peyronnet's construction as adapted for the intended situation.

It is complicated in its form, and, we think, wanting in effect.

The equilibrium of the arches has not been sufficiently attended to;

for when the centres of the bridge at Neuilly were struck, the top

of the arches sank to a degree far beyond anything that has come to

our knowledge, whilst the haunches retired or rose up, so that the

bridge as it now stands is very different in form from what it was

originally designed. No such change of shape took place in the

bridge over the Taff (Pont-y-Prydd); the sinking after the centres

were struck did not amount to one-half of that at Neuilly, although

the one was designed and built under the direction of the first

engineer of France, without regard to expense, whilst the other was

designed and built by a country mason with parsimonious economy.

Our opinion therefore is, that the arches of the bridge over the

Thames should either be plain ellipses, without the slanting off in

the haunches so as to deceive the eye by an apparent flatness which

does not in reality exist, or they should be of a flat segment of a

circle formed in such a manner as to give the requisite room for the

passage of the current and barges under it." |

|

p.317 |

In June, 1810, we find him accepting the direction of

the new bridge at £1,000 a-year for himself and assistants, or £7

7s. a-day and expenses; but on no account were any of his people to

have to do with the payment or receipt of moneys. |

|

p.320 |

The coffer-dams in which the foundations of the

abutments were built, were formed by driving two rows of piles 13 by

6½ inches each, with a counter or abutting pile at every 12 feet 12

by 12, driven in the form of an ellipsis, and strongly cemented

together, at low-water and high-water levels, by double horizontal

walings or bracks, having a space of about 8 inches clear between

them for the intermediate or half piles. The whole were driven

close together from 15 to 20 feet deep into the ground, well

caulked, so as to be water-tight, and all connected firmly together

by strong wrought iron bars and bolts, besides shores and

intermediate braces. The spaces between the two rows of piles

were then rammed close with well-tempered clay, so that they formed,

as it were, a solid vat or tub impermeable to water; and within

these, when pumped clear of water, the excavation was made to the

proper depth, and in the space so dug out the building operations

proceeded. The cofferdams for the piers were formed in a

similar manner, with modifications according to circumstances.

By this means the bed of the river, where the piers were to be

erected, was exposed and dug out to the proper depth, and the

foundations were commenced from a level nine feet at least below

low-water mark. The foundations there rested upon timber piles

from 20 to 22 feet long, driven into the solid bed of the river.

Upon the heads of these piles half-timber planking was spiked, and

on this the solid masonry was built—every stone being fitted,

mortared, and laid with studious accuracy and precision. The

whole work was done with such solidity that, after the lapse of

fifty years, the foundations have not yielded by a straw's breadth

at any point. |

|

p.326 |

Ed.—Rennie's bridge was indeed "a noble work",

its elegant style blending comfortably with that of the adjacent

Somerset House. The Italian sculptor Canova described it as

“the finest bridge in all Europe”—but Smiles's prediction that it

was "built for posterity" was not to be. From the

early 1880's serious problems were found in the bridge's piers

caused by scour from the increased river flow following the removal

of the old London Bridge (ironically, to be replaced by a bridge

designed by Rennie). By the 1920s the problems had become serious.

Heavy superstructure was removed and temporary reinforcements put in

place, but the remedy proved unsuccessful and the bridge was closed

to traffic in 1924. After much debate it was decided eventually to

replace Rennie's bridge with the functional but austere

Portland stone-clad structure (completed in 1945 to a design by Sir

Giles Gilbert Scott) which stands today.

Rennie's Waterloo Bridge was built for the 'Strand Bridge

Company'. Opened in 1817 as a toll bridge, the toll was

removed in 1878 when the bridge was taken over by the Metropolitan

Board of Works. Despite the toll, it soon gained a reputation

as a popular jump for suicides, as is depicted in

Thomas Hood's famous poem, "The

Bridge of Sighs" (illustrated below by Gustav Doré) . . . .

|

|

p.334 |

Article on Iron Bridges in 'Encyclopedia Britannica.'

Ed.—Rennie’s Southwark Bridge was said to be

‘unrivalled as regards its colossal proportions, its architectural

effects and the general simplicity and massive character of its

details’. Alas, as with his two other great Thames bridges,

Rennie's Southwark Bridge was not to be, as Smiles's put it (with

regard to Waterloo Bridge),"built for posterity". An increase

in traffic followed the removal of the tolls in 1868, to the extent

that by the end of the 19th century it had become apparent that

Rennie's bridge was too narrow to cope with the volume, and that a

broader bridge with better approach roads was needed.

Demolition of Rennie's fine bridge began in 1913, but with World War

I intervening the existing bridge was not completed until 1921. |

|

p.335 |

The following is the tradition as given by an old

writer:—"By the east of the Isle of May, twelve miles from all land

in the German Sea, lyes a great hidden rock called Inchcape, very

dangerous to the navigators, because it is overflowed every tide.

It is reported that, in old times, there was upon the said rock a

bell, fixed upon a tree or timber, which rang continually, being

moved by the sea, giving notice to the saylors of the danger.

This bell or clocke was put there by the Abbot of Aberbrothock, and,

being taken down by a sea-pirate, a yeare thereafter he perished

upon the same rock, with ship and goodes, by the righteous judgment

of God." (Stoddart's 'Remarks on Scotland.') |

|

p.337 |

'Fragments of Voyages and Travels,' i. 15-16.

Edinburgh, 1831. |

|

p.338 |

Baron Dupin in his 'Commercial Power of Great

Britain,' says:—"Several engineers submitted plans; but, by the

advice of Mr. Rennie, the model and dimensions of the Eddystone

Lighthouse were adopted with the improvements in lighting, which the

recent progress in optics allowed him to make." (ii. 159.) |

|

p.341 |

A detailed account of the operations was afterwards

published by the assistant-engineer, in his interesting work

entitled 'An Account of the Bell Rock Lighthouse.' By Robert

Stevenson, Civil Engineer. Edinburgh, 1824. |

|

p.343 |

Ed.—"So soon as a barrack of timber-work could

be erected on the rock as a substitute for the floating light, it

was inhabited by Mr. Stevenson and twenty-eight men. This

barrack was a singular habitation, perched on a strong framework of

timber, carefully designed with a view to strength, and no less

carefully put together in its place, and fixed to the rock with

every appliance necessary to secure stability. The tide rose

sixteen feet on it in calm weather, and in heavy seas it was exposed

to the assault of every wave." (Life of Robert Stevenson, Civil

Engineer, by David Stevenson. Adam and Charles Black,

Edinburgh, 1878.) |

|

p.347 |

Letter dated the 12th March, 1814. Boulton MSS. |

|

p.350 |

Ed.—the Bell Rock Lighthouse is maintained by

the Northern Lighthouse Board

who publish the following details:—

|

Light Established: 1811.

Engineer: Robert Stevenson.

Position: Latitude 56° 26.1’N; Longitude 02° 23.1’W.

Situated: 12 Miles from Arbroath.

Character: Flashing White every 5 secs.

Elevation: 28 metres.

Nominal Range: 18 miles.

Structure: White tower 36 metres high. |

|

|

p.351 |

The correspondence which took place on the subject

will be found recorded in the 'Civil Engineer and Architect's

Journal,' Vol. xii., 1849.

Ed.—controversy continues to surround the question of who

should be

credited with the design of this

fine (and the world's oldest water-washed) lighthouse. It's interesting

to note that the Northern Lighthouse Board

website makes no mention of Rennie's contribution, while in the

episode featuring the Bell Rock Lighthouse in the BBC Television

docudrama series, "Seven Wonders of the Industrial World", his role

in its construction (and rather at variance with his track record)

is portrayed as one of meddling

interference. However, while Stevenson undoubtedly carried the

weight of the engineering and much of the lighthouse's design, the

evidence suggests that fellow Scot

Rennie's prudent design decisions —which Stevenson saw fit to

accept—ensured that the Bell Rock's basic structure conformed closely with Smeaton's

time-proven concepts for the Eddystone.

Robert Stevenson F.R.S.E. (1772-1850)—not to be confused with

Robert

Stephenson—became a notable civil engineer specialising in

lighthouse construction but also undertaking a range of other civil engineering

projects (see . . . Robert Stevenson, Civil Engineer,

by David Stevenson, pub. Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh, 1878, a

copy of which is available online at

The Internet Text Archive. |

|

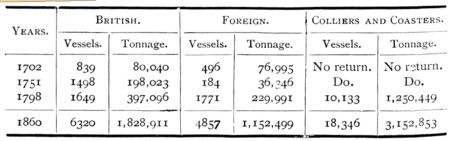

p.352 |

The increase in the trade of London is exhibited by

the following abstract of vessels entered at the port at different

periods since the beginning of last century:—

|

|

p.356-1 |

2 George I I I., cap. 28. |

|

p.356-2 |

P. Colquhoun, LL.D., 'Treatise on the Police of the

Metropolis.' [6th Ed., 237.] |

|

p.358 |

Mr. Jessop was among the most eminent engineers of

his day. His father was engaged under Smeaton in the building

of the Eddystone Lighthouse; and, dying in 1761, he left the

guardianship of his family to Mr. Smeaton, who adopted William as

his pupil, and carefully brought him up to the same profession.

Jessop continued with Smeaton for about ten years; and, after

leaving him, he was engaged successively on the Aire and Calder, the

Calder and Hebble, and the Trent Navigations. He also executed

the Cromford and the Nottingham Canals; the Loughborough and

Leicester, and the Horncastle Navigations; but the most extensive

and important of his works of this kind was the Grand Junction

Canal, by which the whole of the north-western inland navigation of

the kingdom was brought into direct connection with the metropolis.

He was also employed as engineer for the Caledonian Canal, in which

he was succeeded by Telford, who carried out the work. Mr.

Jessop was the engineer of the West India Docks (1800-2), and of the

Bristol Docks (1803-8), both works of great importance. He was

the first engineer employed to lay out and construct railroads, as a

branch of his profession; the Croydon and Merstham Railroad, worked

by donkeys and mules, having been constructed by him as early as

1803. He also laid down short railways in connection with his

canals in Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Nottinghamshire. During the

later years of his life he was much afflicted by paralysis, and died

in 1814. |

|

p.361 |

For further particulars as to these docks see Sir

John Rennie's 'British and Foreign Harbours.' Art. "London Docks." |

|

p.363 |

Among the improvements adopted by Mr. Rennie in these

docks may be mentioned the employment of cast iron, then an

altogether novel expedient, for the roofing of the sheds. One

of these, erected by him in 1813, was 1300 feet long and 29 feet 6

inches in span, supported on cast-iron columns 71 inches in diameter

at bottom and 53/4 at top. Another, still more capacious, of

54 feet clear span between the supports, was erected by him over the

mahogany warehouses in 1817. He also introduced an entirely

new description of iron cranes, first employing wheelwork in

connection with them, by which they worked much more easily and at a

great increase of power. He entirely re-arranged the working

of the mahogany sheds, greatly to the despatch of business and the

economy of labour. His quick observation enabled him to point

out new and improved methods of despatching work, even to those who

were daily occupied in the docks, but whose eyes had probably become

familiar with hurry scurry and confusion. |

|

p.366 |

The Prince's Dock at Liverpool was constructed after

Mr. Rennie's plans; but the greater part of the dock accommodation

at that port was provided under the direction of the late Mr. Jesse

Hartley. Mr. Hartley was a native of the North Riding of

Yorkshire, where his father held the position of Bridgemaster; and

his son, after receiving an ordinary education, served his

apprenticeship as a stonemason, and worked at the building of

Boroughbridge. Subsequently, he succeeded his father as

Bridgemaster, which he continued to retain, until his removal to

Liverpool, when he received the appointment of engineer to the Dock

Committee. During the period in which he held the office of

dock engineer, Mr. Hartley altered or entirely constructed every

dock belonging to the town. He was also engineer to the Bolton

and Manchester Railway and Canal, and consulting engineer for the

Dee Bridge at Chester, the centering for which was considered a

triumph of engineering skill and ability. |

|

p.367 |

See Sir John Rennie's 'British and Foreign Harbours;'

Art, "Aberdeen." |

|

p.368 |

Mr. Rennie proposed to form two docks on the

Broomielaw side of the river—one 1350 feet long and 160 feet wide,

with two entrances, and another 900 feet long and 200 feet wide;

with a third dock upon the Windmill Croft, on the south side of the

river, 300 feet long and 200 feet wide; the whole presenting a total

length of quayage of 6120 feet, besides a river quay wall 1150 feet

long. This magnificent plan, proposed more than half a century

since, viewed by the experience of this day, shows how clearly

Rennie anticipated the commercial growth and manufacturing

prosperity of Glasgow, for which these projected docks would have

afforded ample accommodation, at an estimated capital cost (at the

time the plans were made) of only £130,000. What would

not Glasgow give now to have the benefit of Rennie's docks?

Indeed it is remarkable that, to this day, so little has been done

to realise his idea, and to provide dock accommodation for the trade

of the Clyde, which is now quite as much needed as the same kind of

accommodation was in the Thames at the beginning of the present

century. |

|

p.370 |

The occasion on which this plan was first recommended

was in Mr. Rennie's report (1793) on the Hutchison Bridge across the

Clyde. That bridge, erected by another engineer, fell down on

the removal of the centres, on which Mr. Rennie was sent for, post

haste, by the Lord Provost and magistrates of Glasgow, to confer

with them on the subject; and his advice as to the rebuilding of the

bridge on another site was subsequently adopted. It appeared,

from an inspection of the ruined piers, that a breast or quay wall

had been built on the south side of the river, and to the west of

the bridge, which had not been executed according to contract.

The report stated:—"The above walls should be enlarged in their

dimensions and altered in their construction; they ought to be

carried at least to the level of the river bed, and made five feet

thick at the base next to the bridge, and four feet thick at the

top, battering one-fifth of their height in a curvilinear form,

the beds of the stones being radiated to the centre of the curve;

as the height lessens, the dimensions of the walls may be diminished

in the same proportion, and, if built as above described, I have no

doubt of the works being permanent." |

|

p.375-1 |

It will be remembered that the 'Great Eastern' was

nearly wrecked in consequence of the bad holding-ground within the

new harbour in the year 1859. |

|

p.375-2 |

Ed.—A letter was received by the Corporation

from Mr. H. Yeo, Secretary to the Commissioners of Howth Harbour,

requesting the Corporation to consider Mr. John Rennie’s plan of the

proposed lighthouse to be erected at the end of the East Pier to

direct vessels into the entrance of the harbour. . . .Mr. Rennie

stated that the light intended was to be a steady red and

consequently a distinguishing light. . . . The fixed red light was

established on 1st July 1818, it compromised twelve Argand lamps

with red lamp glasses and silvered copper catoptric reflectors. . .

. The cut stone tower is very similar to the tower designed by John

Rennie and established about the same time at Salt Island, Holyhead

Harbour. The overall height of tower lantern and dome is

approximately 14.5m (from website of

The Commissioners of Irish Lights). |

|

p.376-1 |

Mr. Rennie's plan of Kingstown Harbour consisted of

two piers of four arms each carried out from the shore 3700 feet

distant from each other, their heads inclined inwards at an angle of

122 degrees, and terminating in a depth of 26 feet at low water of

spring tides. The width between the outer angles of the two

outer arms of the pier was 1150 feet, the entrance pointing N.E. ½

E. The total space enclosed was 250 acres. The works

were commenced in 1817, the first stone being laid by the Earl of

Whitworth, the Lord Lieutenant; and the works were still in progress

at Mr. Rennie's death in 1821. The harbour subsequently fell

under the jurisdiction of the Irish Board of Works, and all sorts of

new plans were adopted at variance with the original design of Mr.

Rennie, in carrying out which it is to be feared that the harbour

has been seriously injured. |

|

p.376-2 |

This dock is 900 feet long by 370 wide. It

covers a surface of 7½ acres, and is capable of holding about

seventy sail of square-rigged vessels. The entrance lock

communicating with the tidal harbour opening into the Humber is 42

feet wide and 158 feet long between the gates, with the cill laid 6

feet below low water of spring tides. |

|

p.376-3 |

Ed.—Harwich Low Lighthouse, located on the

North Sea promenade off the Harbour Crescent, is a 45ft high,

ten-sided brick tower with a projecting canopy at ground level.

Harwich High Lighthouse, located at the south end of West Street, is

a nine-sided tower of grey

brickwork, 90ft high, being 20ft 6in wide at the base and tapering

to a 13ft-wide top capped in stone and decorated with an urn. It

contains seven floor levels and is now a private home. Both lighthouses—positioned some 150 meters

apart—were built in 1818 to replace earlier wooded structures (one

of the latter being famously

depicted by the landscape artist, John Constable). They

acted as a pair of "leading lights", which when in transit (i.e. one

appearing vertically above the other) provided shipping with a line

of entry into the harbour channel. However, due to the changing course of

the channel the lights became redundant in 1863 and were replaced

with a newly-positioned pair of lights housed in cast iron towers. |

|

p.379 |

It would occupy much space to mention in detail the

various harbours in the United Kingdom which Mr Rennie was employed

to examine, report upon, and improve; but the following summary may

suffice:—In England he examined and reported on Rye Harbour (1801);

Dover (1802); Hastings projected Harbour (1806); Berwick, where he

constructed the fine pier at the mouth of the Tweed, 2740 feet in

length ( 1807); Margate Harbour (carried out 1808); Liverpool Docks,

on which he made an elaborate report (1809); North Sunderland

(1809); Shoreham (1810); Newhaven (1810); Harbour of Refuge in the

Downs, north of Sandown Castle, on which he made a careful report

(1812); Prince's Dock, Liverpool, of which he furnished the designs

(1812); Bridlington (1812); Sidmouth (1812); Rye, a second report

(1813); Blyth (1814); Ramsey, Isle of Man (1814); Port Leven,

Mount's Bay, Cornwall (1814); Bridgewater (1814); Whitehaven (1814);

Scarborough (1816); the improvement of the navigation of the river

Tyne (1816); Yarmouth (1818); Fishguard, Wales (1819); Kidwelly,

Wales (1820); and Sunderland (1821). He also suggested various

improvements, many of which were carried out, in the following

harbours of Scotland, besides those above mentioned: Loch Buy, Isle

of Skye (1793); Port Mahomack, near Tarbet Ness (1793);

Kirkcudbright and Saltcoats (1799); Craigmore, near Boroughstoness

(1804); Montrose (1805); Ayr, where the improvements recommended by

him were carried out (1805); Peterhead (1806); Frazerburgh, only

partially carried out (1806); Charleston (1807); Alloa (1808); St.

Andrew's ( 1808); Portnessock, Galloway (1813); Ardrossan (1811 and

1815); and Portpatrick (1819). In like manner he was

consulted, and reported, as to the following Irish

harbours:—Westport (1805); Ardinglass (1809); Dublin (1811);

Balbriggan (1818); Donaghadee (1819); and Belfast (1821). He

was also consulted respecting dry docks at Malta (1815), and a

harbour and docks at Bermuda (1815). |

|

p.381 |

From the following brief description it will be

observed how skilfully he carried out these views in laying out the

intended harbour at Charleston. He proposed to construct two

great piers, one placed at the western extremity of the little

inlet, to which a railway was being laid down—the straight part

extending outwards about 154 yards, from which there were to be two

kants of about 64 yards each, the

last going 57 yards below low-water mark. From thence there

was to be a return bend about 70 yards long, in a direction

considerably to the north of east. At 50 yards from the

extremity of this pier, another of the same length was proposed to

be made, forming an angle with it of about 120 degrees, with two

other kants similar to the former, and a larger one extending to the

shore the entrance being 50 yards wide, and the outer arm or kant of

the east pier making an angle of 120 degrees with it, so that both

the outer arms made similar kants with each other. A large

space would thus be enclosed, which, he believed, would make a very

commodious and capacious harbour. "By the above construction,"

he says in his report, "though it may seem that its exposure will

admit of the swells from the south and south-west getting into the

harbour, yet when it is considered that the angle at which a wave

will strike the Heads will occasion a rebound in a similar angle to

that in which it is struck, and as this will be the case from each

Head, it follows that these reflected waves, meeting each other,

will occasion a resistance which will have the effect of preventing

a considerable part of the sea-wave from entering the harbour, and

what does enter it will expend its fury on the flat beach within,

and soon become quiet." This might, he added, be in a great

measure prevented by extending the pier-heads further seaward, but

which the large additional expense precluded him from recommending;

and, indeed, there would always be abundant shelter for the shipping

under one or other of the pier heads. Besides, as the Frith

was only about two miles wide at the place, the probability was that

there would be no such heavy seas as to render so expensive a

measure necessary. The plan was, however, carried out to only

a limited extent, and we merely quote the report because of the

valuable principles to be observed in the construction of harbours,

which are here so clearly enunciated. |

|

p.383 |

See Life of Smeaton. p. 186. |

|

p.391-1 |

See Descriptive View of Romney Marsh, vol. i. p.5. |

|

p.391-2 |

Ed.—Smiles fails to mention that building the

Royal Military Canal proved a very unsatisfactory project, and

although it did acquire an important role, this had neither military

nor commercial purpose.

The contract to build the canal

was let to a consortium of sub-contractors with whose work Rennie

was familiar, and work commenced on 30th October 1804.

Considering that this was the age of manual labour, that 22½ miles

(of the 28) had to be dug by hand, that the Canal was wider and

deeper (60 feet wide by 9 feet deep) than most navigation canals,

that it was to have flanking drains and a 30 feet wide military road

protected by a rampart, the contract completion date of June 1805

(less than eight months) seems amazingly unrealistic; and such it

proved to be. In March 1805 Rennie wrote 'In respect to the

contractors, I am sorry to say they have greatly disappointed my

expectations, founded upon the diligence and accuracy with which I

have seen other great works done by them'. The contract

was dogged by a severe labour shortage added to which were problems

with the excavations flooding. At a meeting on 6 June, five

days after the works ought to have been completed, only 6 miles had

been constructed. The consortium were dismissed from the

contract and the military took over the work. Following the

battle of Trafalgar (21 October, 1805) the threat of French invasion

diminished, nevertheless work pressed on to completion in 1809.

Following the Napoleonic War the Canal assumed a minor

commercial role, but was eventually abandoned by the Government in

1877, being leased to the Lords of the Level of Romney Marsh.

During the early years of WWII, when invasion appeared imminent, the

Canal again assumed military importance as an anti-invasion ditch

and was fortified with pillboxes.

Today, much of the Canal is managed by the Environment Agency

(Shepway District Council manage the rest) who

use it to manage water levels over the surrounding marshland

where it provides a source of irrigation during periods of drought

and a vital flood defence at other times. It is a popular

destination for walkers (its full length being

open to the public) and anglers, and a haven for wildlife,

part being designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. |

|

p.391-3 |

Mr. Rennie seems to have been frequently in

communication with the military authorities of the day on warlike

matters. Thus, in 1809, he was applied to for a gang of

workmen to proceed to Flushing, during the unfortunate Walcheren

expedition, to assist in destroying the piers, floodgates, and

basins of that port; after effecting which they returned home. |

|

p.392 |

Mr. Rennie had a very mean opinion of Fulton,

regarding him as a quack who traded upon the inventions of others.

He considered that little merit belonged to him in regard to the

invention of the steamboat. Thus, Jonathan Hulls, Miller of

Dalswinton, and Symington had been at work upon the invention long

before Fulton. Fulton's alleged invention of cast-iron bridges

was not more original. Writing to Mr. Barrow of the Admiralty,

in 1817, Mr. Rennie says:—"I send you Mr. Fulton's book on Canals,

published in 1796, when he was in England, and previous to his

application of the steam-engine to the working of wheels in boats.

On the designs (as to bridges, &c.) contained in that book, his

fame, I believe, principally rests; although he acknowledges that

Earl Stanhope had previously proposed similar plans, and that Mr.

Reynolds of Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, had actually carried them

into execution; so that all the merit he has—if merit it may be

called—is a proposal for extending the principle previously applied

in this country. The first iron bridge was erected at

Coalbrookdale in 1779, and between that and the publication of

Fulton's book in 1796 many others were erected; so that, in this

department, he has little to boast of. I consider Fulton with

whom I was personally acquainted, a man of very slender abilities,

though possessing much self-confidence and consummate impudence." |

|

p.393 |

The quarantine establishment of the port of London

was then situated at Stangate Creek, which joins the Medway about

two miles above Sheerness. It consisted of several old two and

three-decker hulks, into which goods were placed. Passengers

while performing quarantine might well fret and fume at their

detention, having before them a most uninteresting prospect—a wide

extent of flat marshland, with a fringe of mud at low water. A

small vessel of war was stationed at the entrance of the creek to

prevent infringement of the regulations. The annoyance caused

by this establishment was very great, and it was more and more

complained of as our foreign commerce extended. On several

occasions, vessels filled with passengers, having accidentally run

foul of the the ships performing quarantine, were compelled at once

to heave-to, and undergo two or three days' detention before they

could be released. To diminish this evil, the Government

determined to erect a permanent quarantine establishment about three

miles up Stangate Creek, at a place called Chetney Hill, a small

rising ground situated in the marshes. It was proposed to

isolate this hill by a canal, provided with a lock; and Mr. Rennie

was requested to prepare the requisite plans, which he did (in

1806), and the works were executed at a heavy expense; but we

believe they were never used, and the old hulks continued to be

employed until the final abandonment of the quarantine system. |

|

p.396 |

By way of illustrating his views, Mr. Rennie used to

say:—"Let any stranger visit Portsmouth Dockyard, the head

establishment of the British Navy, he will be astonished at the

vastness and number of buildings, and perhaps say, 'What a wonderful

place it is!' knowing nothing about the subject. But I can

compare the place to nothing else than to a pack of cards, with the

names of different buildings, docks, &c., marked upon them, and then

tossed up into the air, so that each, in falling, might find its

place by chance,—so completely are they devoid of all arrangement

and order." |

|

p.400 |

The site of the proposed arsenal was the flat portion

of land near Northfleet, about eight hundred acres in extent, lying

in the angular space formed by Fidlers' and Northfleet Reaches.

Its depth close to the shore was about seven fathoms at low water,

or sufficient for vessels of the largest burden. The main

entrance-lock was to be at the Northfleet end of the docks, within

which was to be an entrance-basin 1,815 feet long and 600 feet wide,

covering about twenty-five acres. Dry docks were to be placed

conveniently near, from which the water was to be pumped by powerful

steam-engines, so that vessels might be docked directly from the

basin, and have their bottoms examined with the least loss of time.

Part of the entrance-basin was to be appropriated for an

anchor-wharf, another for a gun-wharf; next the stores and

victualling wharves, with their appropriate buildings; the whole

arranged on a system, so that the materials required on shipboard

might be passed forward to their respective wharves from one stage

of preparation to another, with the greatest despatch and economy.

At the north end of the basin were to be the mast and boat ponds,

with their adjoining workshops, connected also with the Thames and

the main western basin by separate entrances. The main western

basin was to be at right angles to the entrance-basin, 4,000 feet

long and 950 feet wide, covering a surface of about eighty acres.

Alongside were to be six dry docks and eight building slips, all

fitted in the most complete manner with the requisite saw-pits,

seasoning-sheds, mould-lofts, timber stores, and smitheries,

conveniently situated in the rear. The whole of the heavy

work, such as bellows-blowing, tilt-hammering, forging of anchors,

and iron-rolling, was to be performed by the aid of steam-engines

and machinery of the most perfect kind. Seventy sail of the

line, with a proportionate number of smaller vessels, might

conveniently lie in this basin, and yet afford abundant space for

the launching of new vessels. Another basin, 980 feet long and

500 feet wide, was proposed for timber-ships, on the south-west

extremity of the great basin, with a separate entrance into the

Thames a little below Greenhithe. The whole of the arsenal was

to be connected together by a system of railways extending to every

part and all round the wharves. The plan was most complete,

some of the details being highly ingenious. But the cost of

executing the work was the real difficulty; Mr. Rennie's estimate of

the total outlay requisite to complete the Works amounting to four

millions and-a-half sterling. Yet the plan was so masterly and

comprehensive, and so obviously the right thing to be done, that the

Portland Administration determined to carry it out, and the

necessary land was bought for the purpose. Frequent changes of

Ministry, however, took place at the time; the resources of the

country were heavily taxed in carrying on the war against Napoleon

in Spain; the public attention was diverted in other quarters; and

no further steps were taken to carry out Mr. Rennie's design.

He knocked at the door of one Administration after another without

effect. In 1810 we find him writing to Lord Mulgrave, the

First Lord; to the Right Hon. George Rose; to the Earl St. Vincent,

and others; but though the more the plans were scrutinised, the more

indisputable did their merits appear, he could find no Ministry

strong enough to carry them out. When peace came, Government

and people were alike sick of wars, naval armaments, and glorious

victories; and believing that all danger from France was at an

end,—the French fleet having been destroyed or captured, and

Napoleon banished to St. Helena,—it was supposed that the old royal

harbours, patched and cobbled up, might answer every purpose.

So the land at Northfleet was sold, and the whole subject dismissed

from the public mind. But, after the lapse of half a century,

the wisdom of Mr. Rennie's advice has become more clearly apparent

even than before. For years past, the waste in our dockyards,

which it was the chief object of his Northfleet design to prevent,

has become one of the principal topics of public discussion, and it

has been the standing opprobrium of every successive Naval

Administration. What Mr. Rennie urged fifty years since still

holds as true as ever —that without concentration economy is

impossible. So long as Government goes on tinkering at the old

dockyards, spending enormous sums of money in the vain attempt to

render them severally efficient, and maintaining separate expensive

staffs in so many different places,—building a ship in one yard and

sending it round the island to another, perhaps more than a hundred

miles distant, to be finished and fitted, and then to another to

take its guns, stores, &c.,—so long shall we have increasing reason

to complain of the frightful waste of public money in the royal

dockyards. |

|

p.417 |

The propriety of this arrangement was proved by the

fact, that whereas the price paid in 1812 for taking and depositing

rubble in the Breakwater was 2s. 9d. per ton, it was

afterwards reduced to 1s. per ton, as the contractors and

workmen became better acquainted with the nature of the work. |

|

p.420 |

The largest quantity of stone deposited in one year

was in 1821, when not less than 373,773 tons were quarried,

lightened, and emptied into the work. |

|

p.423-1 |

These were Mr. Telford, Mr. Josias Jessop, Sir J.

Rennie, and Mr. G. Rennie. For more full particulars as to the

history and construction of the Breakwater, we refer the reader to

Sir John Rennie's elaborate work, entitled, 'An Historical,

Practical, and Theoretical Account of the Breakwater in Plymouth

Sound.' London, 1848. |

|

p.423-2 |

The slopes were paved. with blocks of the largest

stone, firmly wedged together; the centre line was removed 36 feet

further seawards; the top width was reduced 5 feet; a strong binding

course of dovetailed granite masonry was built at the bottom of the

sea slope, which was laid one foot convex from the bottom to the

top; whilst the land slope was laid with close-fitting rubble at the

inclination of 2 to 1. It was, however, found, in the course

of the work, that the rough paving of the rubble alone was scarcely

strong enough to withstand the violence of the waves without a

certain degree of yielding; and Sir J. Rennie, having been consulted

by the Admiralty, recommended that, in addition to the granite

basement binding course, there should be another similar course both

in the centre and at the top of the sea slope; and that the

remainder should be paved with rough-dressed limestone ashlar, set

in courses at right angles to the slope, about three feet deep on

the average—each course binding well with the one adjacent,—the

lower parts of the granite bonding courses being laid level, but the

upper parts forming part of the slope. It was still found that

there was a difficulty in preventing the outer edge or base of the

sea slope, where the main lower granite bonding courses were placed,

from being undermined by the waves; and it was determined to place a

trenching or foreshore on the outside of the sea slope, 40 feet wide

in the centre of the Breakwater, increasing to 50 feet wide at the

commencement of the western arm, and diminishing towards the eastern

arm to the width of only 30 feet. This foreshore was about 2

feet above the level of low water of spring tides next to the toe or

base; and the surface was roughly paved with rubble well wedged

together. The whole of the slope was paved with well-dressed

courses of ashlar masonry without mortar, 3 feet 6 inches deep, well

bedded down upon the rubble below. The extremity of the

western arm was furnished with a solid head of circular masonry, 75

feet diameter at the top, with slopes of 5 to 1 all round. At

the point at which the lighthouse has since been placed, an inverted

arch of solid blocks was formed, the whole well-bonded, dovetailed,

and dowelled together, and firmly united with the other parts of the

solid rock. These works answered admirably, and Plymouth

Breakwater now rests as firm as a rock upon the bottom of the sea. |

|

p.427 |

In 1817, his fame having gone abroad as the most

skilled water engineer of the day, Captain Dufour of Geneva, came to

England for the purpose of consulting him as to the extension and

improvement of the waterworks of that city. Captain Dufour was

introduced to Mr. Rennie by the mutual friend of both, the eminent

Dr. Wollaston. Mr. Rennie made a careful and detailed report

on the surveys and plans submitted to him, especially on the engine

and pumping machinery of the proposed works; and his advice was

followed, very much to the advantage of the citizens of Geneva. |

|

p.430 |

Captain Huddart died at his house in Highbury

Terrace, London, in 1816, closing a life of unblemished integrity in

the seventy-fifth year of his age. |

|

p.432-1 |

Letter to the Admiralty, 22nd May, 1820. |

|

p.432-2 |

Mr. Rennie was engaged for many years in urging the

introduction of steam power in the Royal Navy. In 1817 we find

him writing to Lord Melville, Sir J. Yorke, Sir D. Milne, and others

on the subject. It would appear that Lord Melville had

declared that he was determined to employ steam-vessels as tugs, so

soon as he could convince the Sea Lords of their advantages; on

which Mr. Rennie compliments Sir D. Milne, saying that he is "glad

to find that there is one admiral in the navy favourable to

steamboats." In July 1818, he laments that he cannot convince

Sir G. Hope or Mr. Secretary Yorke of their utility, but that he is

persuaded their adoption must come at last. On the 30th May,

1820, he writes James Watt, of Birmingham, informing him that the

Admiralty had at last decided upon having a steamboat,

notwithstanding the strong resistance of the Navy Board. "My

reasons," he says, "I understand were satisfactory; but unless the

Admiralty cram it down the throats of the Navy Board, nothing will

be done; for of all the ignorant, obstinate, and stupid boards under

the Crown, the Navy Board is the worst. I am so disgusted with

them that, could I at the present moment with decency relinquish the

works under them which I have in hand, I would do so at once." |

|

p.438 |

The new bridge was erected about thirty yards higher

up the river than the old one, and involved the construction of new

approaches on both sides. The first coffer-dam was put in on

the Southwark side, and the first pile was driven on the 15th of

March, 1824; the foundation stone was laid with great ceremony by

H.R.H. the Duke of York, on the 15th of June, 1825, assisted by the

Lord Mayor (Garrett), the Aldermen, and Common Council. The

bridge was finally completed and formally opened by His Majesty King

William the Fourth, on the 1st of August, 1831—the time occupied in

its construction having been seven years and three months. The

total cost of the bridge and approaches was about two millions

sterling. All the masonry below low water is composed of hard

sand-stone grit, from Bramley Fall, near Leeds; and the whole of the

exterior masonry above low water is of the finest hard gray granite,

from Aberdeen, Devonshire, and Cornwall. The actual width of

the arches as executed is as follows: the centre arch is 152 feet 6

inches span; the two arches next the centre are 140 feet; and the

two land arches 130 feet. The details of construction of the

coffer-dams, piers, and floating and fixing the centres, were

similar to those adopted by Mr. Rennie in building Waterloo and

Southwark bridges. The total length of the bridge is 1,005

feet; width from outside to outside, 56 feet; width of the

footpaths, 18 feet; and of the carriage-way, 35 feet. The

total quantity of stone built into the bridge is 120,000 tons.

The builders were Messrs. Joliffe and Banks, the greatest

contractors of their day. |

|

p.441 |

The Digue is of considerably greater extent than the

breakwater at Plymouth, being above 2¼ English miles long. Up to the

time of Mr. Rennie's visit, the work had been a series of attempts

and failures, which, however, eventually produced experience, and

led to success. Wooden cones filled with small stones were first

tried; they were sunk so as to form a sea rampart; but the cones

were shattered to pieces by the force of the waves, and the stones

were scattered about in the bottom of the sea. Then loose

rubble-stones were tried; but the blocks were too small, and these,

too, were driven asunder. Larger blocks were then used; but, for a

time, the smaller stones beneath acted as rollers to the larger

ones. At length, however, these found their bearing, and when

Mr. Rennie visited the place, the slope formed by the sea-ridge of

rubble was as much as 11 to 1. This greatly increased the

contents of the breakwater, while its stability was not much to be

depended on. Many accidents occurred to the work, and several

extensive breaches were made through it by the force of the sea.

At low water the height of the Digue was at some parts only three

feet; at others, considerably more; whereas, in some places, the top

of the work was from seven to eight feet below low water of spring

tides. At length, after many years' labour and vast expense,

the work has been brought to completion; and it now forms a very

excellent defence for the fine war roadstead and arsenal of

Cherbourg, greatly exceeding the humble dimensions which it

presented when Mr. Rennie visited the place. The whole cost of

the works amounted to upwards of seven millions sterling. |

|

p.444 |

Archibald Skirving, like John Rennie, was the son of

an East Lothian farmer. He was born in 1749, at Garleton, a

farm belonging to the Earl of Wemyss. His father, Adam

Skirving, was a well-known humorist and ballad-maker—one of his

songs, 'Hey, Johnny Cope,' a description of the rout of the royal

army at the battle of Prestonpans, being still popular in Scotland.

In early life Archibald went to Rome to study art, and remained in

Italy nine years. He walked back the whole way from Rome, but,

passing through France, the revolutionary war broke out, when he was

apprehended and thrown into prison, where he lay for nine months.

He subsequently studied painting under David. Returned to

Scotland, be pursued his art in a somewhat desultory manner, not

being under the necessity of applying himself to it with that

patient and continuous devotion which is essential to attaining high

eminence in any profession. He painted when, where, and whom

he pleased; and sometimes pursued a very singular course with his

sitters. Notwithstanding his eccentricity, Skirving was an

extremely clever artist, and his crayon drawings have rarely been

surpassed for vigour and brilliancy. He executed probably the

best head of Burns the poet, with whom he was intimate; and the

portrait of John Rennie, which Mr. Holl has rendered with great

skill, will give a good idea of Skirving's power as a delineator of

character. Skirving and Rennie were intimate friends, although

in most respects so unlike each other. Yet Skirving had as

true a genius; and might have secured as great a reputation in his

own walk as his friend Rennie, had he worked as patiently and

industriously. As he grew older, he became more eccentric and

sarcastic. He dressed oddly, in a broad-brimmed white hat,

without any neckcloth. Allan Cunningham relates the story of

Skirving's calling on Chantrey while he was finishing the bust of

Bird, the artist. "Well!—and who is that?" asked Skirving.

"Bird, the eminent painter." "Painter!—and what does he

paint?" "Ludicrous subjects, Sir." "Ludicrous subjects!

—Have you sat?" "Yes—he has had one sitting; but when he heard

that a gentleman with a white hat, who wore no neckcloth, had

arrived from the North, he said, 'Go—go; I know of a subject more

ludicrous still ; Skirving is come!"' This odd, but clever artist

died at Inveresk, near Edinburgh, in 1819, at the advanced age of

seventy. |

|