|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VI.

WORKERS IN ART.

|

"If what shone afar so grand,

Turn to nothing in thy hand,

On again; the virtue lies

In the struggle, not the prize–R. M. Milnes.

"Excelle, et tu vivras."—Joubert. |

EXCELLENCE in

art, as in everything else, can only be achieved by dint of

painstaking labour. There is nothing less accidental than the

painting of a fine picture or the chiselling of a noble statue.

Every skilled touch of the artist's brush or chisel, though guided

by genius, is the product of unremitting study.

Sir Joshua Reynolds was such a believer in the force of

industry, that he held that artistic excellence, "however expressed

by genius, taste, or the gift of heaven, may be acquired."

Writing to Barry he said, "Whoever is resolved to excel in painting,

or indeed any other art, must bring all his mind to bear upon that

one object from the moment that he rises till he goes to bed."

And on another occasion he said, "Those who are resolved to excel

must go to their work, willing or unwilling, morning, noon, and

night: they will find it no play, but very hard labour." But

although diligent application is no doubt absolutely necessary for

the achievement of the highest distinction in art, it is equally

true that without the inborn genius, no amount or mere industry,

however well applied, will make an artist. The gift comes by

nature, but is perfected by self-culture, which is of more avail

than all the imparted education of the schools.

Some of the greatest artists have had to force their way

upward in the face of poverty and manifold obstructions.

Illustrious instances will at once flash upon the reader's mind.

Claude Lorraine, the pastry cook; Tintoretto, the dyer; the two

Caravaggios, the one a colour-grinder, the other a mortar-carrier at

the Vatican; Salvator Rosa, the associate of bandits; Giotto, the

peasant boy; Zingaro, the gipsy; Cavedone, turned out of doors to

beg by his father; Canova, the stone-cutter; these, and many other

well-known artists, succeeded in achieving distinction by severe

study and labour, under circumstances the most adverse.

Nor have the most distinguished artists of our own country been born

in a position of life more than ordinarily favourable to the culture

of artistic genius. Gainsborough and Bacon were the sons of

cloth-workers; Barry was an Irish sailor boy, and Maclise a banker's

apprentice at Cork; Opie and Romney, like Inigo Jones, were

carpenters; West was the son of a small Quaker farmer in

Pennsylvania; Northcote was a watchmaker, Jackson a tailor, and Etty

a printer; Reynolds, Wilson, and Wilkie, were the sons of clergymen;

Lawrence was the son of a publican, and Turner of a barber. Several

of our painters, it is true, originally had some connection with

art, though in a very humble way,—such as Flaxman, whose father sold

plaster casts; Bird, who ornamented tea-trays; Martin, who was a

coach-painter; Wright and Gilpin, who were ship-painters; Chantrey,

who was a carver and gilder; and David Cox, Stanfield, and Roberts,

who were scene-painters.

It was not by luck or accident that these men achieved distinction,

but by sheer industry and hard work. Though some achieved wealth,

yet this was rarely, if ever, their ruling motive. Indeed, no mere

love of money could sustain the efforts of the artist in his early

career of self-denial and application. The pleasure of the pursuit

has always been its best reward; the wealth which followed but an

accident. Many noble-minded artists have preferred following the

bent of their genius, to chaffering with the public for terms. Spagnoletto verified in his life the beautiful fiction of Xenophon,

and after he had acquired the means of luxury, preferred withdrawing

himself from their influence, and voluntarily returned to poverty

and labour. When Michael Angelo was asked his opinion respecting a

work which a painter had taken great pains to exhibit for profit, he

said, "I think that he will be a poor fellow so long as he shows

such an extreme eagerness to become rich."

Like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Michael Angelo was a great believer in the

force of labour; and he held that there was nothing which the

imagination conceived, that could not be embodied in marble, if the

hand were made vigorously to obey the mind. He was himself one of

the most indefatigable of workers; and he attributed his power of

studying for a greater number of hours than most of his

contemporaries, to his spare habits of living. A little bread and

wine was all he required for the chief part of the day when employed

at his work; and very frequently he rose in the middle of the night

to resume his labours. On these occasions, it was his practice to

fix the candle, by the light of which he chiselled, on the summit of

a pasteboard cap which he wore. Sometimes he was too wearied to

undress, and he slept in his clothes, ready to spring to his work so

soon as refreshed by sleep. He had a favourite device of an old man

in a go-cart, with an hour-glass upon it bearing the inscription, Ancora imparo! Still I am learning.

Titian, also, was an indefatigable worker. His celebrated "Pietro

Martire" was eight years in hand, and his "Last Supper" seven.

In his letter to Charles V. he said, "I send your Majesty the 'Last

Supper' after working at it almost daily for seven years—dopo sette

anni lavorandovi quasi continuamente." Few think of the patient

labour and long training involved in the greatest works of the

artist. They seem easy and quickly accomplished, yet with how great

difficulty has this ease been acquired. "You charge me fifty

sequins," said the Venetian nobleman to the sculptor, "for a bust

that cost you only ten days' labour." "You forget," said the artist,

"that I have been thirty years learning to make that bust in ten

days." Once when Domenichino was blamed for his slowness in

finishing a picture which was bespoken, he made answer, "I am

continually painting it within myself." It was eminently

characteristic of the industry of the late Sir Augustus Callcott,

that he made not fewer than forty separate sketches in the

composition of his famous picture of "Rochester." This constant

repetition is one of the main conditions of success in art, as in

life itself.

No matter how generous nature has been in bestowing the gift of

genius, the pursuit of art is nevertheless a long and continuous

labour. Many artists have been precocious, but without diligence

their precocity would have come to nothing. The anecdote related of

West is well known. When only seven years old, struck with the

beauty of the sleeping infant of his eldest sister whilst watching

by its cradle, he ran to seek some paper and forthwith drew its

portrait in red and black ink. The little incident revealed the

artist in him, and it was found impossible to draw him from his

bent. West might have been a greater painter, had he not been

injured by too early success: his fame, though great, was not

purchased by study, trials, and difficulties, and it has not been

enduring.

Richard Wilson, when a mere child, indulged himself with tracing

figures of men and animals on the walls of his father's house, with

a burnt stick. He first directed his attention to portrait painting;

but when in Italy, calling one day at the house of Zucarelli, and

growing weary with waiting, he began painting the scene on which his

friend's chamber window looked. When Zucarelli arrived, he was so

charmed with the picture, that he asked if Wilson had not studied

landscape, to which he replied that he had not. "Then, I advise

you," said the other, "to try; for you are sure of great success." Wilson adopted the advice, studied and worked hard, and became our

first great English landscape painter.

|

|

|

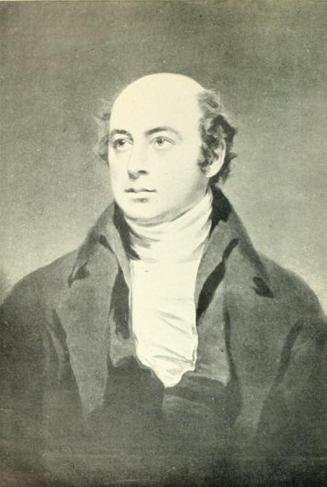

SIR

JOSHUA REYNOLDS

R.A., F.R.S., F.R.S.A. (1723-92):

English painter.

Picture: Project Gutenberg. |

Sir Joshua Reynolds, when a boy, forgot his lessons, and took

pleasure only in drawing, for which his father was accustomed to

rebuke him. The boy was destined for the profession of physic, but

his strong instinct for art could not be repressed, and he became a

painter. Gainsborough went sketching, when a schoolboy, in the woods

of Sudbury; and at twelve he was a confirmed artist: he was a keen

observer and a hard worker,—no picturesque feature of any scene he

had once looked upon, escaping his diligent pencil. William Blake, a

hosier's son, employed himself in drawing designs on the backs of

his father's shop-bills, and making sketches on the counter. Edward

Bird, when a child only three or four years old, would mount a chair

and draw figures on the walls, which he called French and English

soldiers. A box of colours was purchased for him, and his father,

desirous of turning his love of art to account, put him apprentice

to a maker of tea-trays! Out of this trade he gradually raised

himself, by study and labour, to the rank of a Royal Academician.

THOMAS

GAINSBOROUGH R.A.

(1727-88):

English painter.

Picture (self portrait): Wikipedia.

Hogarth, though a very dull boy at his lessons, took pleasure in

making drawings of the letters of the alphabet, and his school

exercises were more remarkable for the ornaments with which he

embellished them, than for the matter of the exercises themselves. In the latter respect he was beaten by all the blockheads of the

school, but in his adornments he stood alone. His father put him

apprentice to a silversmith, where he learnt to draw, and also to

engrave spoons and forks with crests and ciphers. From

silver-chasing, he went on to teach himself engraving on copper,

principally griffins and monsters of heraldry, in the course of

which practice he became ambitious to delineate the varieties of

human character. The singular excellence which he reached in this

art, was mainly the result of careful observation and study. He had

the gift, which he sedulously cultivated, of committing to memory

the precise features of any remarkable face, and afterwards

reproducing them on paper; but if any singularly fantastic form or

outré face came in his way, he would make a sketch of it on the

spot, upon his thumb-nail, and carry it home to expand at his

leisure. Everything fantastical and original had a powerful

attraction for him, and he wandered into many out-of-the-way places

for the purpose of meeting with character. By this careful storing

of his mind, he was afterwards enabled to crowd an immense amount of

thought and treasured observation into his works. Hence it is that

Hogarth's pictures are so truthful a memorial of the character, the

manners, and even the very thoughts of the times in which he lived. True painting, he himself observed, can only be learnt in one

school, and that is kept by Nature. But he was not a highly

cultivated man, except in his own walk. His school education had

been of the slenderest kind, scarcely even perfecting him in the art

of spelling; his self-culture did the rest. For a long time he was

in very straitened circumstances, but nevertheless worked on with a

cheerful heart. Poor though he was, he contrived to live within his

small means, and he boasted, with becoming pride, that he was "a

punctual paymaster." When he had conquered all his difficulties and

become a famous and thriving man, he loved to dwell upon his early

labours and privations, and to fight over again the battle which

ended so honourably to him as a man and so gloriously as an artist.

"I remember the time," said he on one occasion, "when I have gone

moping into the city with scarce a shilling, but as soon as I have

received ten guineas there for a plate, I have returned home, put on

my sword, and sallied out with all the confidence of a man who had

thousands in his pockets."

WILLIAM

HOGARTH (1697-1764):

English painter, engraver and satirist.

Picture (self portrait): Wikipedia.

"Industry and perseverance" was the motto of the sculptor Banks,

which he acted on himself, and strongly recommended to others. His

well-known kindness induced many aspiring youths to call upon him

and ask for his advice and assistance; and it is related that one

day a boy called at his door to see him with this object, but the

servant, angry at the loud knock he had given, scolded him, and was

about sending him away, when Banks overhearing her, himself went

out. The little boy stood at the door with some drawings in his

hand. "What do you want with me?" asked the sculptor. "I want, sir,

if you please, to be admitted to draw at the Academy." Banks

explained that he himself could not procure his admission, but he

asked to look at the boy's drawings. Examining them, he said, "Time

enough for the Academy, my little man! go home—mind your

schooling—try to make a better drawing of the Apollo—and in a month

come again and let me see it." The boy went home—sketched and worked

with redoubled diligence—and, at the end of the month, called again

on the sculptor. The drawing was better; but again Banks sent him

back, with good advice, to work and study. In a week the boy was

again at his door, his drawing much improved; and Banks bid him be

of good cheer, for if spared he would distinguish himself. The boy

was Mulready; and the sculptor's augury was amply fulfilled.

The fame of Claude Lorraine is partly explained by his indefatigable

industry. Born at Champagne, in Lorraine, of poor parents, he was

first apprenticed to a pastry cook. His brother, who was a

wood-carver, afterwards took him into his shop to learn that trade. Having there shown indications of artistic skill, a travelling

dealer persuaded the brother to allow Claude to accompany him to

Italy. He assented, and the young man reached Rome, where he was

shortly after engaged by Agostino Tassi, the landscape painter, as

his house-servant. In that capacity Claude first learnt landscape

painting, and in course of time he began to produce pictures. We

next find him making the tour of Italy, France, and Germany,

occasionally resting by the way to paint landscapes, and thereby

replenish his purse. On returning to Rome he found an increasing

demand for his works, and his reputation at length became European. He was unwearied in the study of nature in her various aspects. It

was his practice to spend a great part of his time in closely

copying buildings, bits of ground, trees, leaves, and such like,

which he finished in detail, keeping the drawings by him in store

for the purpose of introducing them in his studied landscapes. He

also gave close attention to the sky, watching it for whole days

from morning till night; and noting the various changes occasioned

by the passing clouds and the increasing and waning light. By this

constant practice he acquired, although it is said very slowly, such

a mastery of hand and eye as eventually secured for him the first

rank among landscape painters.

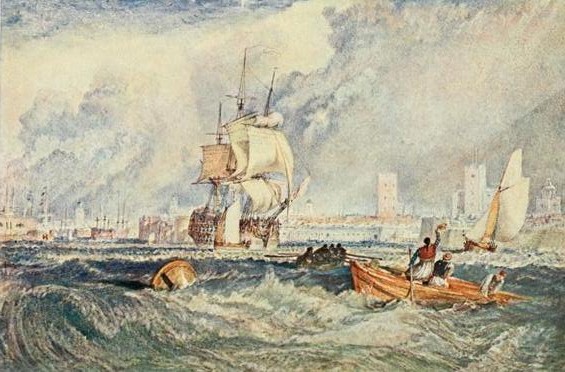

J. M. W. TURNER

R.A. (1775-1851):

English landscape painter.

Picture (self-portrait): Wikipedia.

Turner, who has been styled "the English Claude," pursued a career

of like laborious industry. He was destined by his father for his

own trade of a barber, which he carried on in London, until one day

the sketch which the boy had made of a coat of arms on a silver

salver having attracted the notice of a customer whom his father

was shaving, the latter was urged to allow his son to follow his

bias, and he was eventually permitted to follow art as a profession. Like all young artists, Turner had many difficulties to encounter,

and they were all the greater that his circumstances were so

straitened. But he was always willing to work, and to take pains

with his work, no matter how humble it might be. He was glad to hire

himself out at half-a-crown a night to wash in skies in Indian ink

upon other people's drawings, getting his supper into the bargain. Thus he earned money and acquired expertness. Then he took to

illustrating guide-books, almanacs, and any sort of books that

wanted cheap frontispieces. "What could I have done better?" said he

afterwards; "it was first-rate practice." He did everything

carefully and conscientiously, never slurring over his work because

he was ill-remunerated for it. He aimed at learning as well as

living; always doing his best, and never leaving a drawing without

having made a step in advance upon his previous work. A man who thus

laboured was sure to do much; and his growth in power and grasp of

thought was, to use Ruskin's words, "as steady as the increasing

light of sunrise." But Turner's genius needs no panegyric; his best

monument is the noble gallery of pictures bequeathed by him to the

nation, which will ever be the most lasting memorial of his fame.

Portsmouth, by J. M. W. Turner.

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

To reach Rome, the capital of the fine arts, is usually the highest

ambition of the art student. But the journey to Rome is costly, and

the student is often poor. With a will resolute to overcome

difficulties, Rome may however at last be reached. Thus François

Perrier; an early French painter, in his eager desire to visit the

Eternal City, consented to act as guide to a blind vagrant. After

long wanderings he reached the Vatican, studied and became famous.

Not less enthusiasm was displayed by Jacques Callot in his

determination to visit Rome. Though opposed by his father in his

wish to be an artist, the boy would not be baulked, but fled from

home to make his wav to Italy. Having set out without means, he was

soon reduced to great straits; but falling in with a band of

gipsies, he joined their company, and wandered about with them from

one fair to another, sharing in their numerous adventures. During

this remarkable journey Callot picked up much of that extraordinary

knowledge of figure, feature, and character which he afterwards

reproduced, sometimes in such exaggerated forms, in his wonderful

engravings.

When Callot at length reached Florence, a gentleman, pleased with

his ingenious ardour, placed him with an artist to study; but he was

not satisfied to stop short of Rome, and we find him shortly on his

way thither. At Rome he made the acquaintance of Porigi and

Thomassin, who, on seeing his crayon sketches, predicted for him a

brilliant career as an artist. But a friend of Callot's family

having accidentally encountered him, took steps to compel the

fugitive to return home. By this time he had acquired such a love of

wandering that he could not rest; so he ran away a second time, and

a second time he was brought back by his elder brother, who caught

him at Turin. At last the father, seeing resistance was in vain,

gave his reluctant consent to Callot's prosecuting his studies at

Rome. Thither he went accordingly; and this time he remained,

diligently studying design and engraving for several years, under

competent masters. On his way back to France, he was encouraged by

Cosmo II. to remain at Florence, where he studied and worked for

several years more. On the death of his patron he returned to his

family at Nancy, where, by the use of his burin and needle, he

shortly acquired both wealth and fame. When Nancy was taken by siege

during the civil wars, Callot was requested by Richelieu to make a

design and engraving of the event, but the artist would not

commemorate the disaster which had befallen his native place, and he

refused point-blank. Richelieu could not shake his resolution, and

threw him into prison. There Callot met with some of his old friends

the gipsies, who had relieved his wants on his first journey to

Rome. When Louis XIII. heard of his imprisonment, he not only released

him, but offered to grant him any favour he might ask. Callot

immediately requested that his old companions, the gipsies, might be

set free and permitted to beg in Paris without molestation. This odd

request was granted on condition that Callot should engrave their

portraits, and hence his curious book of engravings entitled "The

Beggars." Louis is said to have offered Callot a pension of 3,000

livres provided he would not leave Paris; but the artist was now too

much of a Bohemian, and prized his liberty too highly to permit him

to accept it; and he returned to Nancy, where he worked till his

death. His industry may be inferred from the number of his

engravings and etchings, of which he left not fewer than 1,600. He

was especially fond of grotesque subjects, which he treated with

great skill; his free etchings, touched with the graver, being

executed with especial delicacy and wonderful minuteness.

Still more romantic and adventurous was the career of Benvenuto

Cellini, the marvellous gold worker, painter, sculptor, engraver,

engineer, and author. His life, as told by himself, is one of the

most extraordinary autobiographies ever written. Giovanni Cellini,

his father, was one of the Court musicians to Lorenzo de Medici at

Florence; and his highest ambition concerning his son Benvenuto was

that he should become an expert player on the flute. But Giovanni

having lost his appointment, found it necessary to send his son to

learn some trade, and he was apprenticed to a goldsmith. The boy had

already displayed a love of drawing and of art; and, applying

himself to his business, he soon became a dexterous workman. Having

got mixed up in a quarrel with some of the townspeople, he was

banished for six months, during which period he worked with a

goldsmith at Sienna, gaining further experience in jewellery and

gold-working.

His father still insisting on his becoming a flute-player, Benvenuto

continued to practise on the instrument, though he detested it. His

chief pleasure was in art, which he pursued with enthusiasm. Returning to Florence,

he carefully studied the designs of Leonardo da Vinci and Michael Angelo; and, still further to improve himself

in gold-working, he went on foot to Rome, where he met with a

variety of adventures. He returned to Florence with the reputation

of being a most expert worker in the precious metals, and his skill

was soon in great request. But being of an irascible temper, he was

constantly getting into scrapes, and was frequently under the

necessity of flying for his life. Thus he fled from Florence in the

disguise of a friar, again taking refuge at Sienna, and afterwards

at Rome.

During his second residence in Rome, Cellini met with extensive

patronage, and he was taken into the Pope's service in the double

capacity of goldsmith and musician. He was constantly studying and

improving himself by acquaintance with the works of the best

masters. He mounted jewels, finished enamels, engraved seals, and

designed and executed works in gold, silver, and bronze, in such a

style as to excel all other artists. Whenever he heard of a

goldsmith who was famous in any particular branch, he immediately

determined to surpass him. Thus it was that he rivalled the medals

of one, the enamels of another, and the jewellery of a third; in

fact, there was not a branch of his business that he did not feel

impelled to excel in.

Working in this spirit, it is not so wonderful that Cellini should

have been able to accomplish so much. He was a man of indefatigable

activity, and was constantly on the move. At one time we find him at

Florence, at another at Rome; then he is at Mantua, at Rome, at

Naples, and back to Florence again; then at Venice, and in Paris,

making all his long journeys on horseback. He could not carry much

luggage with him; so, wherever he went, he usually began by making

his own tools. He not only designed his works, but executed them

himself,—hammered and carved, and cast and shaped them with his own

hands. Indeed, his works have the impress of genius so clearly

stamped upon them, that they could never have been designed by one

person, and executed by another. The humblest article—a buckle for a

lady's girdle, a seal, a locket, a brooch, a ring, or a

button—became in his hands a beautiful work of art.

Cellini was remarkable for his readiness and dexterity in

handicraft. One day a surgeon entered the shop of Raffaello del

Moro, the goldsmith, to perform an operation on his daughter's hand. On looking at the surgeon's instruments, Cellini, who was present,

found them rude and clumsy, as they usually were in those days, and

he asked the surgeon to proceed no further with the operation for a

quarter of an hour. He then ran to his shop, and taking a piece of

the finest steel, wrought out of it a beautifully finished knife,

with which the operation was successfully performed.

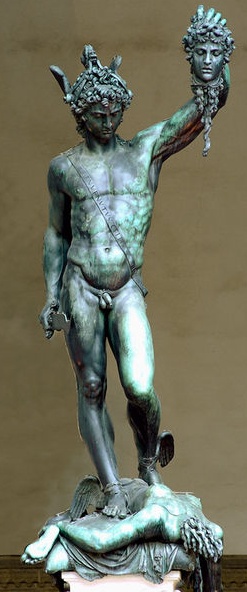

Among the statues executed by Cellini, the most important are the

silver figure of Jupiter, executed at Paris for Francis I., and the

Perseus, executed in bronze for the Grand Duke Cosmo of Florence. He

also executed statues in marble of Apollo, Hyacinthus, Narcissus,

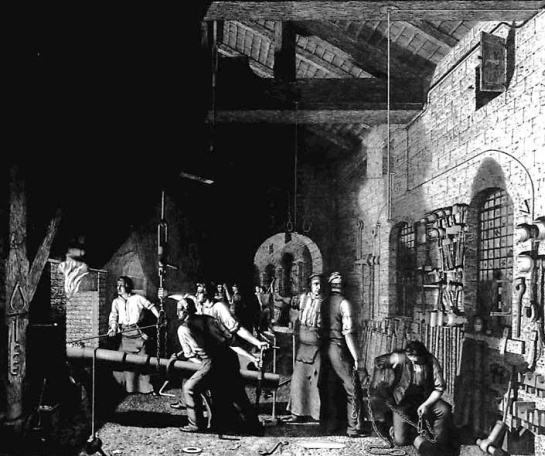

and Neptune. The extraordinary incidents connected with the casting

of the Perseus were peculiarly illustrative of the remarkable

character of the man.

The Grand Duke having expressed a decided opinion that the model,

when shown to him in wax, could not possibly be cast in bronze,

Cellini was immediately stimulated by the predicted impossibility,

not only to attempt, but to do it. He first made the clay model,

baked it, and covered it with wax, which he shaped into the perfect

form of a statue. Then coating the wax with a sort of earth, he

baked the second covering, during which the wax dissolved and

escaped, leaving the space between the two layers for the reception

of the metal. To avoid disturbance, the latter process was conducted

in a pit dug immediately under the furnace, from which the liquid

metal was to be introduced by pipes and apertures into the mould

prepared for it.

Cellini had purchased and laid in several loads of pinewood, in

anticipation of the process of casting, which now began. The furnace

was filled with pieces of brass and bronze, and the fire was lit. The resinous pine-wood was soon in such a furious blaze, that the

shop took fire, and part of the roof was burnt; while at the same

time the wind blowing and the rain falling on the furnace, kept down

the heat, and prevented the metals from melting. For hours Cellini

struggled to keep up the heat, continually throwing in more wood,

until at length he became so exhausted and ill, that he feared he

should die before the statue could be cast. He was forced to leave

to his assistants the pouring in of the metal when melted, and

betook himself to his bed. While those about him were condoling with

him in his distress, a workman suddenly entered the room, lamenting

that "poor Benvenuto's work was irretrievably spoiled!" On hearing

this, Cellini immediately sprang from his bed and rushed to the

workshop, where he found the fire so much gone down that the metal

had again become hard.

|

|

|

Cellini: Perseus with the head of Medusa.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

Sending across to a neighbour for a load of young oak which had been

more than a year in drying, he soon had the fire blazing again and

the metal melting and glittering. The wind was, however, still

blowing with fury, and the rain falling heavily; so, to protect

himself, Cellini had some tables with pieces of tapestry and old

clothes brought to him, behind which he went on hurling the wood

into the furnace. A mass of pewter was thrown in upon the other

metal, and by stirring, sometimes with iron and sometimes with long

poles, the whole soon became completely melted. At this juncture,

when the trying moment was close at hand, a terrible noise as of a

thunderbolt was heard, and a glittering of fire flashed before

Cellini's eyes. The cover of the furnace had burst, and the metal

began to flow! Finding that it did not run with the proper velocity,

Cellini rushed into the kitchen, bore away every piece of copper and

pewter that it contained—some two hundred porringers, dishes, and

kettles of different kinds —and threw them into the furnace. Then

at length the metal flowed freely, and thus the splendid statue of Perseus was cast.

The divine fury of genius in which Cellini rushed to his kitchen and

stripped it of its utensils for the purposes of his furnace, will

remind the reader of the like act of Pallissy in breaking up his

furniture for the purpose of baking his earthenware. Excepting,

however, in their enthusiasm, no two men could be less alike in

character. Cellini was an Ishmael against whom, according to his own

account, every man's hand was turned. But about his extraordinary

skill as a workman, and his genius as an artist, there cannot be two

opinions.

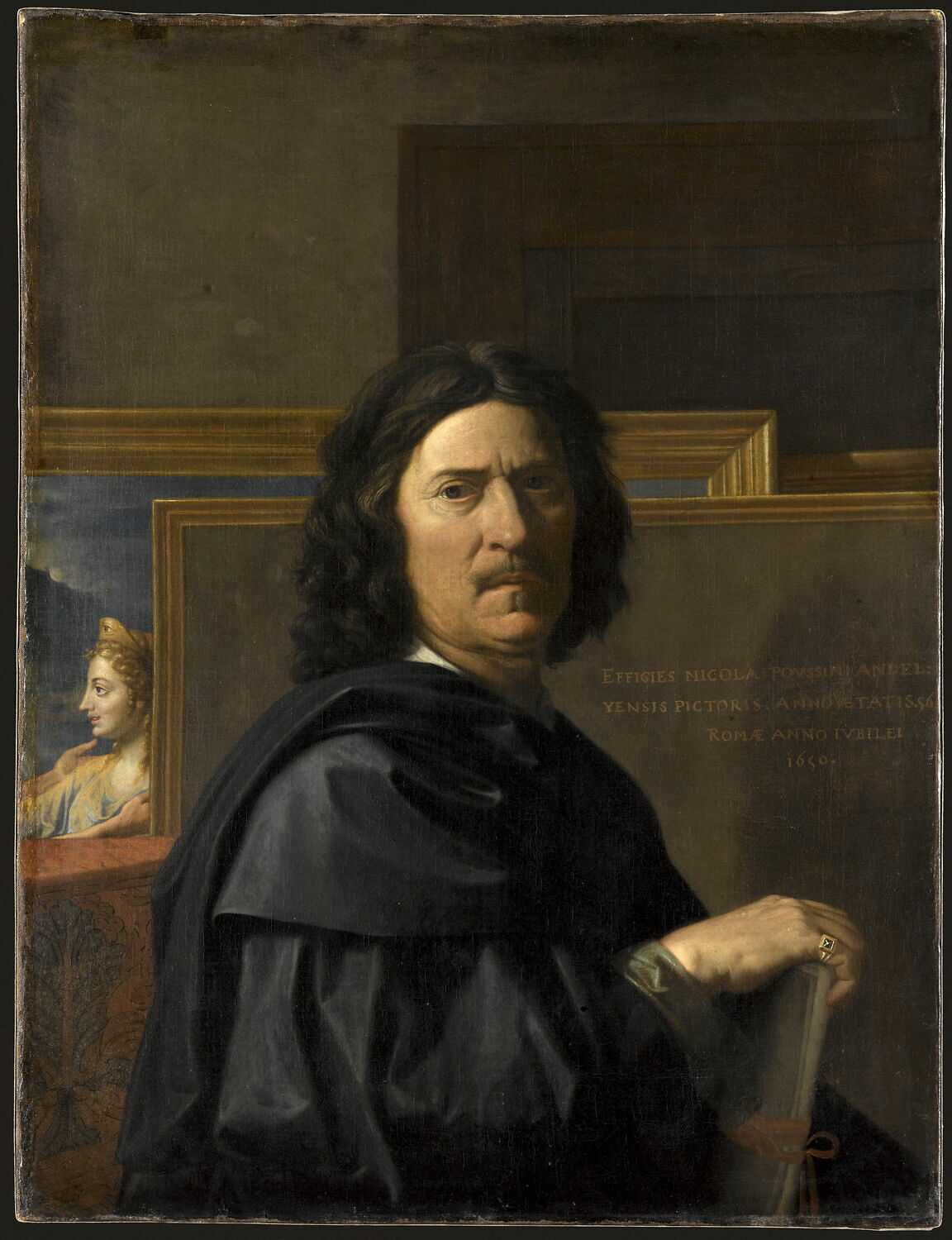

Much less turbulent was the career of Nicolas Poussin a man as pure

and elevated in his ideas of art as he was in his daily life, and

distinguished alike for his vigour of intellect, his rectitude of

character, and his noble simplicity. He was born in a very humble

station, at Andeleys, near Rouen, where his father kept a small

school. The boy had the benefit of his parent's instruction, such as

it was, but of that he is said to have been somewhat negligent,

preferring to spend his time in covering his lesson-books and his

slate with drawings. A country painter, much pleased with his

sketches, besought his parents not to thwart him in his tastes. The

painter agreed to give Poussin lessons, and he soon made such

progress that his master had nothing more to teach him. Becoming

restless, and desirous of further improving himself, Poussin, at the

age of 18, set out for Paris, painting signboards on his way for a

maintenance.

NICOLAS

POUSSIN (1594-1665):

French Painter.

Picture (self portrait): Wikipedia.

At Paris a new world of art opened before him, exciting his wonder

and stimulating his emulation. He worked diligently in many studios,

drawing, copying, and painting pictures. After a time, he resolved,

if possible, to visit Rome, and set out on his journey; but he only

succeeded in getting as far as Florence, and again returned to

Paris. A second attempt which he made to reach Rome was even less

successful; for this time he only got as far as Lyons. He was,

nevertheless, careful to take advantage of all opportunities for

improvement which came in his way, and continued as sedulous as

before in studying and working.

Thus twelve years passed, years of obscurity and toil, of failures

and disappointments, and probably of privations. At length Poussin

succeeded in reaching Rome. There he diligently studied the old

masters, and especially the ancient statues, with whose perfection

he was greatly impressed. For some time he lived with the sculptor Duquesnoi, as poor as himself, and assisted him in modelling figures

after the antique. With him he carefully measured some of the most

celebrated statues in Rome, more particularly the 'Antinous:' and it

is supposed that this practice exercised considerable influence on

the formation of his future style. At the same time he studied

anatomy, practised drawing from the life, and made a great store of

sketches of postures and attitudes of people whom he met, carefully

reading at his leisure such standard books on art as he could borrow

from his friends.

During all this time he remained very poor, satisfied to be

continually improving himself. He was glad to sell his pictures for

whatever they would bring. One, of a prophet, he sold for eight livres; and another, the 'Plague of the Philistines,' he sold for 60

crowns—a picture afterwards bought by Cardinal de Richelieu for a

thousand. To add to his troubles, he was stricken by a cruel malady,

during the helplessness occasioned by which the Chevalier del Posso

assisted him with money. For this gentleman Poussin afterwards

painted the 'Rest in the Desert,' a fine picture, which far more

than repaid the advances made during his illness.

The brave man went on toiling and learning through suffering. Still

aiming at higher things, he went to Florence and Venice, enlarging

the range of his studies. The fruits of his conscientious labour at

length appeared in the series of great pictures which he now began

to produce,—his 'Death of Germanicus,' followed by 'Extreme Unction,'

the 'Testament of Eudamidas,' the 'Manna,' and the 'Abduction of the

Sabines.'

The reputation of Poussin, however, grew but slowly. He was of a

retiring disposition and shunned society. People gave him credit for

being a thinker much more than a painter. When not actually employed

in painting, he took long solitary walks in the country, meditating

the designs of future pictures. One of his few friends while at Rome

was Claude Lorraine, with whom he spent many hours at a time on the

terrace of La Trinité-du-Mont, conversing about art and

antiquarianism. The monotony and the quiet of Rome were suited to

his taste, and, provided he could earn a moderate living by his

brush, he had no wish to leave it.

But his fame now extended beyond Rome, and repeated invitations were

sent him to return to Paris. He was offered the appointment of

principal painter to the King. At first he hesitated; quoted the

Italian proverb, Chi sta bene non si muove; said he had lived

fifteen years in Rome, married a wife there, and looked forward to

dying and being buried there. Urged again, he consented, and

returned to Paris. But his appearance there awakened much

professional jealousy, and he soon wished himself back in Rome

again. While in Paris he painted some of his greatest works—his

'Saint Xavier,' the 'Baptism,' and the 'Last Supper.' He was kept

constantly at work. At first he did whatever he was asked to do,

such as designing frontispieces for the royal books, more

particularly a Bible and a Virgil, cartoons for the Louvre, and

designs for tapestry; but at length he expostulated—"It is

impossible for me," he said to M. de Chanteloup, "to work at the

same time at frontispieces for books, at a Virgin, at a picture of

the Congregation of St. Louis, at the various designs for the

gallery, and, finally, at designs for the royal tapestry. I have

only one pair of hands and a feeble head, and can neither be helped

nor can my labours be lightened by another."

Annoyed by the enemies his success had provoked and whom he was

unable to conciliate, he determined, at the end of less than two

years' labour in Paris, to return to Rome. Again settled there in

his humble dwelling on Mont Pincio, he employed himself diligently

in the practice of his art during the remaining years of his life,

living in great simplicity and privacy. Though suffering much from

the disease which afflicted him, he solaced himself by study, always

striving after excellence. "In growing old," he said, "I feel myself

becoming more and more inflamed with the desire of surpassing myself

and reaching the highest degree of perfection." Thus toiling,

struggling, and suffering, Poussin spent his later years. He had no

children; his wife died before him; all his friends were gone: so

that in his old age he was left absolutely alone in Rome, so full of

tombs, and died there in 1665, bequeathing to his relatives at Andeleys the savings of his life, amounting to about 1,000 crowns;

and leaving behind him, as a legacy to his race, the great works of

his genius.

The career of Ary Scheffer furnishes one of the best examples in

modern times of a like high-minded devotion to art. Born at

Dordrecht, the son of a German artist, he early manifested an

aptitude for drawing and painting, which his parents encouraged. His

father dying while he was still young, his mother resolved, though

her means were but small, to remove the family to Paris, in order

that her son might obtain the best opportunities for instruction. There young Scheffer was placed with Guérin the painter. But his

mother's means were too limited to permit him to devote himself

exclusively to study. She had sold the few jewels she possessed, and

refused herself every indulgence, in order to forward the

instruction of her other children. Under such circumstances, it was

natural that Ary should wish to help her and by the time he was

eighteen years of age he began to paint small pictures of simple

subjects, which met with a ready sale at moderate prices. He also

practised portrait painting, at the same time gathering experience

and earning honest money. He gradually improved in drawing,

colouring, and composition. The 'Baptism' marked a new epoch in his

career, and from that point he went on advancing, until his fame

culminated in his pictures illustrative of 'Faust,' his 'Francisca

de Rimini,' 'Christ the Consoler,' the 'Holy Women,' 'St. Monica and

St. Augustin,' and many other noble works.

"The amount of labour, thought, and attention," says Mr. Grote,

"which Scheffer brought to the production of the 'Francisca,' must

have been enormous. In truth, his technical education having been so

imperfect, he was forced to climb the steep of art by drawing upon

his own resources, and thus, whilst his hand was at work, his mind

was engaged in meditation. He had to try various processes of

handling, and experiments in colouring; to paint and repaint, with

tedious and unremitting assiduity. But Nature had endowed him with

that which proved in some sort an equivalent for shortcomings of a

professional kind. His own elevation of character, and his profound

sensibility, aided him in acting upon the feelings of others through

the medium of the pencil." [p.173]

One of the artists whom Scheffer most admired was Flaxman; and he

once said to a friend, "If I have unconsciously borrowed from any

one in the design of the 'Francisca,' it must have been from

something I had seen among Flaxman's drawings." John Flaxman was the

son of a humble seller of plaster casts in New Street, Covent

Garden. When a child, he was such an invalid that it was his custom

to sit behind his father's shop counter propped by pillows, amusing

himself with drawing and reading. A benevolent clergyman, the Rev.

Mr. Matthews, calling at the shop one day, saw the boy trying to

read a book, and on inquiring what it was, found it to be a

Cornelius Nepos, which his father had picked up for a few pence at a

bookstall. The gentleman, after some conversation with the boy, said

that was not the proper book for him to read, but that he would

bring him one. The next day he called with translations of Homer and

'Don Quixote,' which the boy proceeded to read with great avidity. His mind was soon filled with the heroism which breathed through the

pages of the former, and, with the stucco Ajaxes and Achilleses

about him, ranged along the shop shelves, the ambition took

possession of him, that he too would design and embody in poetic

forms those majestic heroes.

Like all youthful efforts, his first designs were crude. The proud

father one day showed some of them to Roubilliac the sculptor, who

turned from them with a contemptuous "pshaw!" But the boy had the

right stuff in him; he had industry and patience; and he continued

to labour incessantly at his books and drawings. He then tried his

young powers in modelling figures in plaster of Paris, wax, and

clay. Some of these early works are still preserved, not because of

their merit, but because they are curious as the first healthy

efforts of patient genius. It was long before the boy could walk,

and he only learnt to do so by hobbling along upon crutches. At

length he became strong enough to walk without them.

The kind Mr. Matthews invited him to his house, where his wife

explained Homer and Milton to him. They helped him also in his

self-culture—giving him lessons in Greek and Latin, the study of

which he prosecuted at home. By dint of patience and perseverance,

his drawing improved so much that he obtained a commission from a

lady, to execute six original drawings in black chalk of subjects in

Homer. His first commission! What an event in the artist's life! A

surgeon's first fee, a lawyer's first retainer, a legislator's first

speech, a singer's first appearance behind the foot-lights, an

author's first book, are not any of them more full of interest to

the aspirant for fame than the artist's first commission. The boy at

once proceeded to execute the order, and he was both well praised

and well paid for his work.

At fifteen Flaxman entered a pupil at the Royal Academy. Notwithstanding his retiring disposition, he soon became known among

the students, and great things were expected of him. Nor were their

expectations disappointed: in his fifteenth year he gained the

silver prize, and next year he became a candidate for the gold one. Everybody prophesied that he would carry off the medal, for there

was none who surpassed him in ability and industry. Yet he lost it,

and the gold medal was adjudged to a pupil who was not afterwards

heard of. This failure on the part of the youth was really of

service to him; for defeats do not long cast down the

resolute-hearted, but only serve to call forth their real powers. "Give me time," said he to his father, "and I will yet produce works

that the Academy will be proud to recognise." He redoubled his

efforts, spared no pains, designed and modelled incessantly, and

made steady if not rapid progress. But meanwhile poverty threatened

his father's household; the plaster-cast trade yielded a very bare

living; and young Flaxman, with resolute self-denial, curtailed his

hours of study, and devoted himself to helping his father in the

humble details of his business. He laid aside his Homer to take up

the plaster-trowel. He was willing to work in the humblest

department of the trade so that his father's family might be

supported, and the wolf kept from the door. To this drudgery of his

art he served a long apprenticeship; but it did him good. It

familiarised him with steady work, and cultivated in him the spirit

of patience. The discipline may have been hard, but it was

wholesome.

Happily, young Flaxman's skill in design had reached the knowledge

of Josiah Wedgwood, who sought him out for the purpose of employing

him to design improved patterns of china and earthenware. It may

seem a humble department of art for such a genius as Flaxman to work

in; but it really was not so. An artist may be labouring truly in

his vocation while designing a common teapot or water-jug. Articles

in daily use amongst the people, which are before their eyes at

every meal, may be made the vehicles of education to all, and

minister to their highest culture. The most ambitious artist may

thus confer a greater practical benefit on his countrymen than by

executing an elaborate work which he may sell for thousands of

pounds to be placed in some wealthy man's gallery where it is hidden

away from public sight. Before Wedgwood's time the designs which

figured upon our china and stoneware were hideous both in drawing

and execution, and he determined to improve both. Flaxman did his

best to carry out the manufacturer's views. He supplied him from

time to time with models and designs of various pieces of

earthenware, the subjects of which were principally from ancient

verse and history. Many of them are still in existence, and some are

equal in beauty and simplicity to his after designs for marble. The

celebrated Etruscan vases, specimens of which were to be found in

public museums and in the cabinets of the curious, furnished him

with the best examples of form, and these he embellished with his

own elegant devices. 'Stuart's Athens,' then recently published,

furnished him with specimens of the purest-shaped Greek utensils; of

these he adopted the best, and worked them into new shapes of

elegance and beauty. Flaxman then saw that he was labouring in a

great work—no less than the promotion of popular education; and he

was proud, in after life, to allude to his early labours in this

walk, by which he was enabled at the same time to cultivate his love

of the beautiful, to diffuse a taste for art among the people, and

to replenish his own purse, while he promoted the prosperity of his

friend and benefactor.

At length, in the year 1782, when twenty-seven years of age, he

quitted his father's roof and rented a small house and studio in

Wardour Street, Soho; and what was more, he married—Ann Denman was

the name of his wife—and a cheerful, bright-souled, noble woman she

was. He believed that in marrying her he should be able to work with

an intenser spirit; for, like him, she had a taste for poetry and

art; and besides was an enthusiastic admirer of her husband's

genius. Yet when Sir Joshua Reynolds—himself a bachelor —met Flaxman

shortly after his marriage, he said to him, "So, Flaxman, I am told

you are married; if so, sir, I tell you you are ruined for an

artist." Flaxman went straight home, sat down beside his wife, took

her hand in his, and said, "Ann, I am ruined for an artist." "How

so, John? How has it happened? and who has done it?" "It happened,"

he replied, "in the church, and Ann Denman has done it." He then

told her of Sir Joshua's remark—whose opinion was well known, and

had often been expressed, that if students would excel they must

bring the whole powers of their mind to bear upon their art, from

the moment they rose until they went to bed; and also, that no man

could be a great artist unless he studied the grand works of Raffaelle, Michael Angelo, and others, at Rome and Florence. "And

I," said Flaxman, drawing up his little figure to its full height,

"I would be a great artist." "And a great artist you shall be,"

said his wife, "and visit Rome too, if that be really necessary to

make you great." "But how?" asked Flaxman. "Work and economise,"

rejoined the brave wife; "I will never have it said that Ann Denman

ruined John Flaxman for an artist." And so it was determined by the

pair that the journey to Rome was to be made when their means would

admit. "I will go to Rome," said Flaxman, "and show the President

that wedlock is for a man's good rather than his harm; and you, Ann,

shall accompany me."

Patiently and happily the affectionate couple plodded on during five

years in their humble little home in Wardour Street, always with the

long journey to Rome before them. It was never lost sight of for a

moment, and not a penny was uselessly spent that could be saved

towards the necessary expenses. They said no word to any one about

their project; solicited no aid from the Academy; but trusted only

to their own patient labour and love to pursue and achieve their

object. During this time Flaxman exhibited very few works. He could

not afford marble to experiment in original designs; but he obtained

frequent commissions for monuments, by the profits of which he

maintained himself. He still worked for Wedgwood, who was a prompt

paymaster; and, on the whole, he was thriving, happy, and hopeful. His local respectability was even such as to bring local honours and

local work upon him; for he was elected by the ratepayers to collect

the watch-rate for the Parish of St. Anne, when he might be seen

going about with an ink-bottle suspended from his button-hole,

collecting the money.

At length Flaxman and his wife having accumulated a sufficient store

of savings, set out for Rome. Arrived there, he applied himself

diligently to study; maintaining himself, like other poor artists,

by making copies from the antique. English visitors sought his

studio, and gave him commissions; and it was then that he composed

his beautiful designs illustrative of Homer, Æschylus, and Dante. The price paid for them was moderate—only fifteen shillings a-piece;

but Flaxman worked for art as well as money; and the beauty of the

designs brought him other friends and patrons. He executed Cupid and

Aurora for the munificent Thomas Hope, and the Fury of Athamas for

the Earl of Bristol. He then prepared to return to England, his

taste improved and cultivated by careful study; but before he left.

Italy, the Academies of Florence and Carrara recognised his merit by

electing him a member.

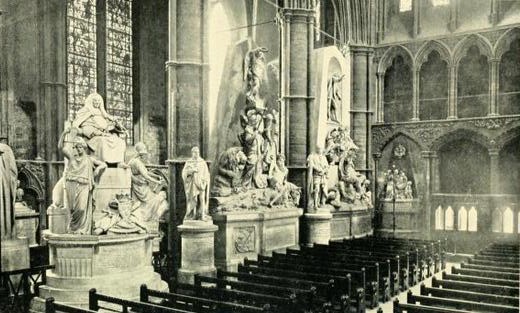

His fame had preceded him to London, where he soon found abundant

employment. While at Rome he had been commissioned to execute his

famous monument in memory of Lord Mansfield, and it was erected in

the north transept of Westminster Abbey shortly after his return. It

stands there in majestic grandeur, a monument to the genius of

Flaxman himself—calm, simple, and severe. No wonder that Banks, the

sculptor, then in the heyday of his fame, exclaimed when he saw it,

"This little man cuts us all out!"

Monument to Lord Mansfield (left) by Flaxman.

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

When the members of the Royal Academy heard of Flaxman's return, and

especially when they had an opportunity of seeing and admiring his

portrait-statue of Mansfield, they were eager to have him enrolled

among their number. He allowed his name to be proposed in the

candidates' list of associates, and was immediately elected. Shortly

after, he appeared in an entirely new character. The little boy who

had begun his studies behind the plaster-cast-seller's shop-counter

in New Street, Covent Garden, was now, a man of high intellect and

recognised supremacy in art, to instruct students, in the character

of Professor of Sculpture to the Royal Academy! And no man better

deserved to fill that distinguished office; for none is so able to

instruct others as he who, for himself and by his own efforts, has

learnt to grapple with and overcome difficulties. |

©

Copyright

Bob Jones and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

|

Reliefs by Flaxman on the Rotunda, Ikworth House. [p.178]

© Copyright

Bob Jones and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

After a long, peaceful, and happy life, Flaxman found himself

growing old. The loss which he sustained by the death of his

affectionate wife Ann, was a severe shock to him; but he survived

her several years, during which he executed his celebrated "Shield

of Achilles," and his noble "Archangel Michael vanquishing

Satan,"—perhaps his two greatest works.

Chantrey was a more robust man;—somewhat rough, but hearty in his

demeanour; proud of his successful struggle with the difficulties

which beset him in early life; and, above all, proud of his

independence. He was born a poor man's child, at Norton, near

Sheffield. His father dying when he was a mere boy, his mother

married again. Young Chantrey used to drive an ass laden with

milk-cans across its back into the neighbouring town of Sheffield,

and there serve his mother's customers with milk. Such was the

humble beginning of his industrial career; and it was by his own

strength that he rose from that position, and achieved the highest

eminence as an artist. Not taking kindly to his step-father, the boy

was sent to trade, and was first placed with a grocer in Sheffield. The business was very distasteful to him; but, passing a carver's

shop window one day, his eye was attracted by the glittering

articles it contained, and, charmed with the idea of being a carver,

he begged to be released from the grocery business with that object.

His friends consented, and he was bound apprentice to the carver and

gilder for seven years. His new master, besides being a carver in

wood, was also a dealer in prints and plaster models; and Chantrey

at once set about imitating both, studying with great industry and

energy. All his spare hours were devoted to drawing, modelling, and

self-improvement, and he often carried his labours far into the

night. Before his apprenticeship was out—at the age of twenty-one—he paid over to his master the whole wealth which he was able to

muster—a sum of £50—to cancel his indentures, determined to devote

himself to the career of an artist. He then made the best of his way

to London, and with characteristic good sense, sought employment as

an assistant carver, studying painting and modelling at his

bye-hours. Among the jobs on which he was first employed as a

journeyman carver, was the decoration of the dining-room of Mr.

Rogers, the poet—a room in which he was in after years a welcome

visitor; and he usually took pleasure in pointing out his early

handiwork to the guests whom he met at his friend's table.

Returning to Sheffield on a professional visit, he advertised

himself in the local papers as a painter of portraits in crayons and

miniatures, and also in oil. For his first crayon portrait he was

paid a guinea by a cutler; and for a portrait in oil, a confectioner

paid him as much as £5 and a pair of top boots! Chantrey was soon in

London again to study at the Royal Academy; and next time he

returned to Sheffield he advertised himself as ready to model

plaster busts of his townsmen, as well as paint portraits of them. He was even selected to design a monument to a deceased vicar of the

town, and executed it to the general satisfaction. When in London he

used a room over a stable as a studio, and there he modelled his

first original work for exhibition. It was a gigantic head of Satan. Towards the close of Chantrey's life, a friend passing through his

studio was struck by this model lying in a corner. "That head," said

the sculptor, "was the first thing that I did after I came to

London. I worked at it in a garret with a paper cap on my head; and

as I could then afford only one candle, I stuck that one in my cap

that it might move along with me, and give me light which ever way I

turned." Flaxman saw and admired this head at the Academy

Exhibition, and recommended Chantrey for the execution of the busts

of four admirals, required for the Naval Asylum at Greenwich. This

commission led to others, and painting was given up. But for eight

years before, he had not earned £5 by his modelling. His famous head

of Horne Tooke was such a success that, according to his own

account, it brought him commissions amounting to £12,000.

SIR FRANCIS

LEGATT CHANTRY,

R.A. (1782-1841):

English sculptor.

Picture (after Raeburn): Internet Text Archive.

Chantrey had now succeeded, but he had worked hard, and fairly

earned his good fortune. He was selected from amongst sixteen

competitors to execute the statue of George III. for the city of

London. A few years later, he produced the exquisite monument of the

Sleeping Children, now in Lichfield Cathedral,—a work of great

tenderness and beauty; and thenceforward his career was one of

increasing honour, fame, and prosperity. His patience, industry, and

steady perseverance were the means by which he achieved his

greatness. Nature endowed him with genius, and his sound sense

enabled him to employ the precious gift as a blessing. He was

prudent and shrewd, like the men amongst whom he was born; the

pocket-book which accompanied him on his Italian tour containing

mingled notes on art, records of daily expenses, and the current

prices of marble. His tastes were simple, and he made his finest

subjects great by the mere force of simplicity. His statue of Watt,

in Handsworth church, seems to us the very consummation of art; yet

it is perfectly artless and simple. His generosity to brother

artists in need was splendid, but quiet and unostentatious. He left

the principal part of his fortune to the Royal Academy for the

promotion of British art. |

'The Sleeping Children', by Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey, R.A., in Litchfied

Cathedral. [p.181]

Picture: Wikipedia.

|

The same honest and persistent industry was throughout distinctive

of the career of David Wilkie. The son of a Scotch minister, he gave

early indications of an artistic turn; and though he was a negligent

and inapt scholar, he was a sedulous drawer of faces and figures. A

silent boy, he already displayed that quiet concentrated energy of

character which distinguished him through life. He was always on the

look-out for an opportunity to draw,—and the walls of the manse, or

the smooth sand by the river side, were alike convenient for his

purpose. Any sort of tool would serve him; like Giotto, he found a

pencil in a burnt stick, a prepared canvas in any smooth stone, and

the subject for a picture in every ragged mendicant he met. When he

visited a house, he generally left his mark on the walls as an

indication of his presence, sometimes to the disgust of cleanly

housewives. In short, notwithstanding the aversion of his father,

the minister, to the "sinful" profession of painting, Wilkie's

strong propensity was not to be thwarted, and he became an artist;

working his way manfully up the steep of difficulty. Though rejected

on his first application as a candidate for admission to the

Scottish Academy, at Edinburgh, on account of the rudeness and

inaccuracy of his introductory specimens, he persevered in producing

better, until he was admitted. But his progress was slow. He applied

himself diligently to the drawing of the human figure, and held on

with the determination to succeed, as if with a resolute confidence

in the result. He displayed none of the eccentric humour and fitful

application of many youths who conceive themselves geniuses, but

kept up the routine of steady application to such an extent that he

himself was afterwards accustomed to attribute his success to his

dogged perseverance rather than to any higher innate power. "The

single element," he said, "in all the progressive movements of my

pencil was persevering industry." At Edinburgh he gained a few

premiums, thought of turning his attention to portrait painting,

with a view to its higher and more certain remuneration, but

eventually went boldly into the line in which he earned his

fame,—and painted his Pitlessie Fair. What was bolder still, he

determined to proceed to London, on account of its presenting so

much wider a field for study and work; and the poor Scotch lad

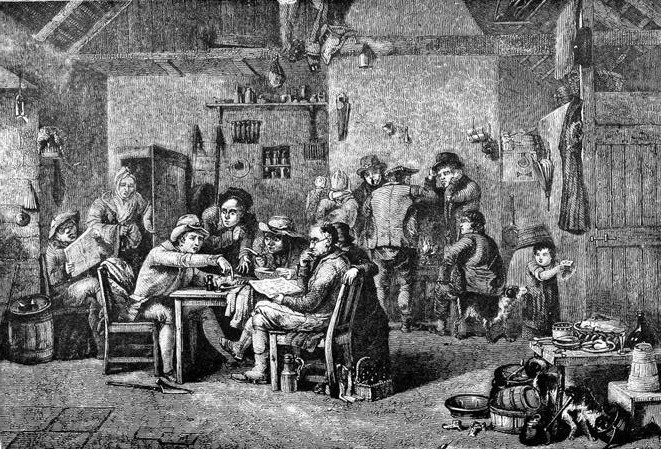

arrived in town, and painted his Village Politicians while living in

a humble lodging on eighteen shillings a week.

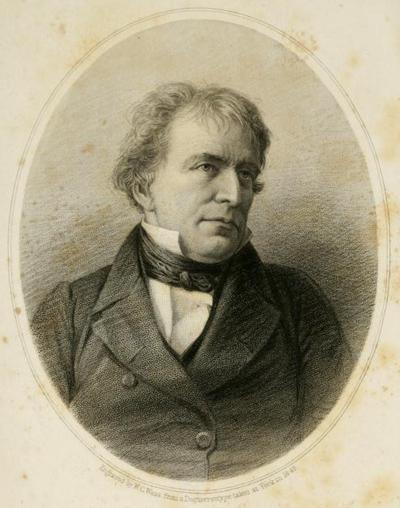

SIR DAVID

WILKIE, R.A.

(1785-1841):

Scottish painter.

Picture (early self-portrait): Wikipedia.

Notwithstanding the success of this picture, and the commissions

which followed it, Wilkie long continued poor. The prices which his

works realized were not great, for he bestowed upon them so much

time and labour, that his earnings continued comparatively small for

many years. Every picture was carefully studied and elaborated

beforehand; nothing was struck off at a heat; many occupied him for

years—touching, retouching, and improving them until they finally

passed out of his hands. As with Reynolds, his motto was "Work!

work! work!" and, like him, he expressed great dislike for talking

artists. Talkers may sow, but the silent reap. "Let us be doing

something," was his oblique mode of rebuking the loquacious and

admonishing the idle. He once related to his friend Constable that

when he studied at the Scottish Academy, Graham, the master of it,

was accustomed to say to the students, in the words of Reynolds, "

If you have genius, industry will improve it; if you have none,

industry will supply its place." "So," said Wilkie, "I was

determined to be very industrious, for I knew I had no genius." He

also told Constable that when Linnell and Burnett, his

fellow-students in London, were talking about art, he always

contrived to get as close to them as he could to hear all they said,

"for," said he, "they know a great deal, and I know very little."

This was said-with perfect sincerity, for Wilkie was habitually

modest. One of the first things that he did with the sum of thirty

pounds which he obtained from Lord Mansfield. for his Village

Politicians, was to buy a present—of bonnets, shawls. and

dresses—for his mother and sister at home; though but little able to

afford it at the time. Wilkie's early poverty had trained him in

habits of strict economy, which were, however, consistent with a

noble liberality, as appears from sundry passages in the

Autobiography of Abraham Raimbach the engraver. |

David Wilkie: The Village Politicians (1806).

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

David Wilkie: The Blind Fiddler (1807).

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

|

William Etty was another notable instance of unflagging industry and

indomitable perseverance in art. His father was a ginger-bread and

spice-maker at York, and his mother—a woman of considerable force

and originality of character—was the daughter of a rope-maker. The

boy early displayed a love of drawing, covering walls, floors, and

tables with specimens of his skill; his first crayon being a

farthing's worth of chalk, and this giving place to a piece of coal

or a bit of charred stick. His mother, knowing nothing of art, put

the boy apprentice to a trade—that of a printer. But in his leisure

hours he went on with the practice of drawing; and when his time was

out he determined to follow his bent—he would be a painter and

nothing else. Fortunately his uncle and elder brother were able and

willing to help him on in his new career, and they provided him with

the means of entering as pupil at the Royal Academy. We observe,

from Leslie's Autobiography, that Etty was looked upon by his fellow

students as a worthy but dull, plodding person, who would never

distinguish himself. But he had in him the divine faculty of work,

and diligently plodded his way upward to eminence in the highest

walks of art.

WILLIAM ETTY,

R.A. (1787-1849):

English painter, best known for his paintings of nudes.

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

Many artists have had to encounter privations which have tried their

courage and endurance to the utmost before they succeeded. What

number may have sunk under them we can never know. Martin

encountered difficulties in the course of his career such as perhaps

fall to the lot of few. More than once he found himself on the

verge of starvation while engaged on his first great picture. It is

related of him that on one occasion he found himself reduced to his

last shilling—a bright shilling—which he had kept because of its

very brightness, but at length he found it necessary to exchange it

for bread. He went to a baker's shop, bought a loaf, and was taking

it away, when the baker snatched it from him, and tossed back the

shilling to the starving painter. The bright shilling had failed him

in his hour of need—it was a bad one! Returning to his lodgings, he

rummaged his trunk for some remaining crust to satisfy his hunger. Upheld throughout by the victorious power of enthusiasm, he pursued

his design with unsubdued energy. He had the courage to work on and

to wait; and when, a few days after, he found an opportunity to

exhibit his picture, he was from that time famous. Like many other

great artists, his life proves that, in despite of outward

circumstances, genius, aided by industry, will be its own protector,

and that fame, though she comes late, will never ultimately refuse

her favours to real merit. |

Etty:

Candaules, King of Lydia, Shews his Wife by Stealth

to Gyges, One of his Ministers, As She Goes to Bed.

Picture: Wikipedia

|

The most careful discipline and training after academic methods will

fail in making an artist, unless he himself take an active part in

the work. Like every highly cultivated man, he must be mainly

self-educated. When Pugin, who was brought up in his father's

office, had learnt all that he could learn of architecture according

to the usual formulas, he still found that he had learned but

little; and that he must begin at the beginning, and pass through

the discipline of labour. Young Pugin accordingly hired himself out

as a common carpenter at Covent Garden Theatre—first working under

the stage, then behind the flys, then upon the stage itself. He thus

acquired a familiarity with work, and cultivated an architectural

taste, to which the diversity of the mechanical employment about a

large operatic establishment is peculiarly favourable. When the

theatre closed for the season, he worked a sailing-ship between

London and some of the French ports, carrying on at the same time a

profitable trade. At every opportunity he would land and make

drawings of any old building, and especially of any ecclesiastical

structure which fell in his way. Afterwards he would make special

journeys to the Continent for the same purpose, and returned home

laden with drawings. Thus he plodded and laboured on, making sure of

the excellence and distinction which he eventually achieved.

A similar illustration of plodding industry in the same walk is

presented in the career of George Kemp, the architect of the

beautiful Scott Monument at Edinburgh. He was the son of a poor

shepherd, who pursued his calling on the southern slope of the

Pentland Hills. Amidst that pastoral solitude the boy had no

opportunity of enjoying the contemplation of works of art. It

happened, however, that in his tenth year he was sent on a message

to Roslin, by the farmer for whom his father herded sheep, and the

sight of the beautiful castle and chapel there seems to have made a

vivid and enduring impression on his mind. Probably to enable him to

indulge his love of architectural construction, the boy besought his

father to let him be a joiner; and he was accordingly put apprentice

to a neighbouring village carpenter. Having served his time, he went

to Galashiels to seek work. As he was plodding along the valley of

the Tweed with his tools upon his back, a carriage overtook him near Elibank Tower; and the coachman, doubtless at the suggestion of his

master, who was seated inside, having asked the youth how far he had

to walk, and learning that he was on his way to Galashiels, invited

him to mount the box beside him, and thus to ride thither. It turned

out that the kindly gentleman inside was no other than Sir Walter

Scott, then travelling on his official duty as Sheriff of

Selkirkshire. Whilst working at Galashiels, Kemp had frequent

opportunities of visiting Melrose, Dryburgh, and Jedburgh Abbeys,

which he studied carefully. Inspired by his love of architecture, he

worked his way as a carpenter over the greater part of the north of

England, never omitting an opportunity of inspecting and making

sketches of any fine Gothic building. On one occasion, when working

in Lancashire, he walked fifty miles to York, spent a week in

carefully examining the Minster, and returned in like manner on foot.

We next find him in Glasgow, where he remained four years, studying

the fine cathedral there during his spare time. He returned to

England again, this time working his way further south; studying

Canterbury, Winchester, Tintern, and other well-known structures. In

1824 he formed the design of travelling over Europe with the same

object, supporting himself by his trade. Reaching Boulogne, he

proceeded by Abbeville and Beauvais to Paris, spending a few weeks

making drawings and studies at each place. His skill as a mechanic,

and especially his knowledge of mill-work, readily secured him

employment wherever he went; and he usually chose the site of his

employment in the neighbourhood of some fine old Gothic structure,

in studying which he occupied his leisure. After a year's working,

travel, and study abroad, he returned to Scotland. He continued his

studies, and became a proficient in drawing and perspective: Melrose

was his favourite ruin; and he produced several elaborate drawings

of the building, one of which, exhibiting it in a "restored" state,

was afterwards engraved. He also obtained employment as a modeller

of architectural designs; and made drawings for a work begun by an

Edinburgh engraver, after the plan of Britton's 'Cathedral

Antiquities.' This was a task congenial to his tastes, and he

laboured at it with an enthusiasm which ensured its rapid advance;

walking on foot for the purpose over half Scotland, and living as an

ordinary mechanic, whilst executing drawings which would have done

credit to the best masters in the art. The projector of the work

having died suddenly, the publication was however stopped, and Kemp

sought other employment. Few knew of the genius of this man—for he

was exceedingly taciturn and habitually modest—when the Committee of

the Scott Monument offered a prize for the best design. The

competitors were numerous—including some of the greatest names in

classical architecture; but the design unanimously selected was that

of George Kemp, who was working at Kilwinning Abbey in Ayrshire,

many miles off, when the letter reached him intimating the decision

of the committee. Poor Kemp! Shortly after this event he met an

untimely death, and did not live to see the first result of his

indefatigable industry and self-culture embodied in stone,—one of

the most beautiful and appropriate memorials ever erected to

literary genius.

John Gibson was another artist full of a genuine enthusiasm and love

for his art, which placed him high above those sordid temptations

which urge meaner natures to make time the measure of profit. He was

born at Gyffn, near Conway, in North Wales—the son of a gardener. He

early showed indications of his talent by the carvings in wood which

he made by means of a common pocket knife; and his father, noting

the direction of his talent, sent him to Liverpool and bound him

apprentice to a cabinet-maker and wood-carver. He rapidly improved

at his trade, and some of his carvings were much admired. He was

thus naturally led to sculpture, and when eighteen years old he

modelled a small figure of Time in wax, which attracted considerable

notice. The Messrs. Franceys, sculptors, of Liverpool, having

purchased the boy's indentures, took him as their apprentice for six

years, during which his genius displayed itself in many original

works. From thence he proceeded to London, and afterwards to Rome;

and his fame became European.

Robert Thorburn, the Royal Academician, like John Gibson, was born

of poor parents. His father was a shoemaker at Dumfries. Besides

Robert there were two other sons; one of whom is a skilful carver in

wood. One day a lady called at the shoemaker's, and found Robert,

then a mere boy, engaged in drawing upon a stool which served him

for a table. She examined his work, and observing his abilities,

interested herself in obtaining for him some employment in drawing,

and enlisted in his behalf the services of others who could assist

him in prosecuting the study of art. The boy was diligent,

pains-taking, staid, and silent, mixing little with his companions,

and forming but few intimacies. About the year 1830, some gentlemen

of the town provided him with the means of proceeding to Edinburgh,

where he was admitted a student at the Scottish Academy. There he

had the advantage of studying under competent masters, and the

progress which he made was rapid. From Edinburgh he removed to

London, where, we understand, he had the advantage of being

introduced to notice under the patronage of the Duke of Buccleuch. We need scarcely say, however, that of whatever use patronage may

have been to Thorburn in giving him an introduction to the best

circles, patronage of no kind could have made him the great artist

that he unquestionably is, without native genius and diligent

application.

|

|

|

SIR

NOEL PATON

FRSA, LL.D. (1821-1901):

Scottish artist. |

Noel Paton, the well-known painter, began his artistic career at

Dunfermline and Paisley, as a drawer of patterns for table-cloths

and muslin embroidered by hand; meanwhile working diligently at

higher subjects, including the drawing of the human figure. He was,

like Turner, ready to turn his hand to any kind of work, and in

1840, when a mere youth, we find him engaged, among his other

labours, in illustrating the 'Renfrewshire Annual.' He worked his

way step by step, slowly yet surely; but he remained unknown until

the exhibition of the prize cartoons painted for the houses of

Parliament, when his picture of the 'Spirit of Religion' (for which he

obtained one of the first prizes) revealed him to the world as a

genuine artist; and the works which he has since exhibited—such as

the 'Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania,' 'Horne,' and 'The bluidy

Tryste'—have shown a steady advance in artistic power and culture.

Another striking exemplification of perseverance and industry in the

cultivation of art in humble life is presented in the career of

James Sharples, a working blacksmith at Blackburn. He was born at

Wakefield in Yorkshire, in 1825, one of a family of thirteen

children. His father was a working iron-founder, and removed to Bury

to follow his business. The boys received no school education, but

were all sent to work as soon as they were able; and at about ten

James was placed in a foundry, where he was employed for about two

years as smithy-boy. After that he was sent into the engine-shop

where his father worked as engine-smith. The boy's employment was to

heat and carry rivets for the boiler-makers. Though his hours of

labour were very long —often from six in the morning until eight at

night—his father contrived to give him some little teaching after

working hours; and it was thus that he partially learned his

letters. An incident occurred in the course of his employment among

the boiler-makers, which first awakened in him the desire to learn

drawing. He had occasionally been employed by the foreman to hold

the chalked line with which he made the designs of boilers upon the

floor of the workshop; and on such occasions the foreman was

accustomed to hold the line, and direct the boy to make the

necessary dimensions. James soon became so expert at this as to be