|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VIII.

WILLIAM CLOWES:

INTRODUCER OF BOOK-PRINTING

BY STEAM.

"The Images of men's wits and knowledges remain in

Books, exempted from the wrong of time, and capable of perpetual

renovation. Neither are they fitly to be called Images,

because they generate still, and cast their seeds in the minds of

others, provoking and causing infinite actions and opinions in

succeeding ages; so that, if the invention of the Ship was thought

so noble, which carrieth riches and commodities from place to place,

and consociateth the most remote Regions in participation of their

Fruits, how much more are letters to be magnified, which, as Ships,

pass through the vast Seas of time, and make ages so distant to

participate of the wisdom, illuminations, and inventions, the one of

the other?"—BACON, On

the Proficience and Advancement of Learning.

STEAM has proved

as useful and potent in the printing of books as in the printing of

newspapers. Down to the end of last century, "the divine art,"

as printing was called, had made comparatively little progress.

That is to say, although books could be beautifully printed by hand

labour, they could not be turned out in any large numbers.

The early printing press was rude. It consisted of a

table, along which the forme of type, furnished with a tympan and

frisket, was pushed by hand. The platen worked vertically

between standards, and was brought down for the impression, and

raised after it, by a common screw, worked by a bar handle.

The inking was performed by balls covered with skin pelts; they were

blacked with ink, and beaten down on the type by the pressman.

The inking was consequently irregular.

Stanhope Press.

Picture: Wikipedia

In 1798, Earl Stanhope perfected the press that bears his

name. He did not patent it, but made his invention over to the

public. In 1818, Mr. Cowper greatly improved the inking of

formes used in the Stanhope and other presses, by the use of a hand

roller covered with a composition of glue and treacle, in

combination with a distributing table. The ink was thus

applied in a more even manner, and with a considerable decrease of

labour. With the Stanhope Press, printing was as far advanced

as it could possibly be by means of hand labour. About 250

impressions could be taken off, on one side, in an hour.

But this, after all, was a very small result. When

books could be produced so slowly, there could be no popular

literature. Books were still articles for the few, instead of

for the many. Steam power, however, completely altered the

state of affairs. When Koenig invented his steam press, he

showed by the printing of Clarkson's 'Life of Penn'—the first sheets

ever printed with a cylindrical press—that books might be printed

neatly, as well as cheaply, by the new machine. Mr. Bensley

continued the process, after Koenig left England; and in 1824,

according to Johnson in his 'Typographic,' his son was "driving an

extensive business."

In the following year, 1825, Archibald Constable, of

Edinburgh, propounded his plan for revolutionising the art of

bookselling. Instead of books being articles of luxury, he

proposed to bring them into general consumption. He would sell

them, not by thousands, but by hundreds of thousands, "ay, by

millions;" and he would accomplish this by the new methods of

multiplication—by machine printing and by steam power. Mr.

Constable accordingly issued a library of excellent books; and,

although he was ruined—not by this enterprise, but the other

speculations into which he entered—he set the example which other

enterprising minds were ready to follow. Amongst these was

Charles Knight, who set the steam presses of William Clowes to work,

for the purposes of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful

Knowledge.

William Clowes was the founder of the vast printing

establishment from which these sheets are issued; and his career

furnishes another striking illustration of the force of industry and

character. He was born on the 1st of January, 1779. His

father was educated at Oxford, and kept a large school at

Chichester; but dying when William was but an infant, he left his

widow, with straitened means, to bring up her family. At a

proper age William was bound apprentice to a printer at Chichester;

and, after serving him for seven years, he came up to London, at the

beginning of 1802, to seek employment as a journeyman. He

succeeded in finding work at a small office on Tower Hill, at a

small wage. The first lodgings he took cost him 5s. a

week; but finding this beyond his means he hired a room in a garret

at 2s. 6d., which was as much as he could afford out

of his scanty earnings.

The first job he was put to, was the setting-up of a large

poster-bill—a kind of work which he had been accustomed to execute

in the country; and he knocked it together so expertly that his

master, Mr. Teape, on seeing what he could do, said to him, "Ah!

I find you are just the fellow for me." The young man,

however, felt so strange in London, where he was without a friend or

acquaintance, that at the end of the first month he thought of

leaving it; and yearned to go back to his native city. But he

had not funds enough to enable him to follow his inclinations, and

he accordingly remained in the great City, to work, to persevere,

and finally to prosper. He continued at Teape's for about two

years, living frugally, and even contriving to save a little money.

He then thought of beginning business on his own account.

The small scale on which printing was carried on in those days

enabled him to make a start with comparatively little capital.

By means of his own savings and the help of his friends, he was

enabled to take a little printing-office in Villiers Street, Strand,

about the end of 1803; and there he began with one printing press,

and one assistant. His stock of type was so small, that he was

under the necessity of working it from day to day like a banker's

gold. When his first job came in, he continued to work for the

greater part of three nights, setting the type during the day, and

working it off at night, in order that the type might be distributed

for resetting on the following morning. He succeeded, however,

in executing his first job to the entire satisfaction of his first

customer.

His business gradually increased, and then, with his

constantly saved means, he was enabled to increase his stock of

type, and to undertake larger jobs. Industry always tells, and

in the long-run leads to prosperity. He married early, but he

married well. He was only twenty-four when he found his best

fortune in a good, affectionate wife. Through this lady's

cousin, Mr. Winchester, the young printer was shortly introduced to

important official business. His punctual execution of orders,

the accuracy of his work, and the despatch with which he turned it

out soon brought him friends, and his obliging and kindly

disposition firmly secured them. Thus, in a few years, the

humble beginner with one press became a printer on a large scale.

The small concern expanded into a considerable printing-office in

Northumberland Court, which was furnished with many presses and a

large stock of type. The office was, unfortunately, burnt

down; but a larger office rose in its place.

What Mr. Clowes principally aimed at, in carrying on his

business, was accuracy, speed, and quantity. He did not seek

to produce editions de luxe in limited numbers, but large

impressions of works in popular demand—travels, biographies,

histories, blue-books, and official reports, in any quantity.

For this purpose, he found the process of hand-printing too tedious,

as well as too costly; and hence he early turned his attention to

book printing by machine presses, driven by steam power,—in this

matter following the example of Mr. Walter of The Times, who

had for some years employed the same method for newspaper printing.

Applegath & Cowper's machines had greatly advanced the art of

printing. They secured perfect inking and register; and the

sheets were printed off more neatly, regularly, and expeditiously;

and larger sheets could be printed on both sides, than by any other

method. In 1823, accordingly, Mr. Clowes erected his first

steam presses, and he soon found abundance of work for them.

But to produce steam requires boilers and engines, the working of

which occasions smoke and noise. Now, as the printing-office,

with its steam presses, was situated in Northumberland Court, close

to the palace of the Duke of Northumberland, at Charing Cross, Mr.

Clowes was required to abate the nuisance, and to stop the noise and

dirt occasioned by the use of his engines. This he failed to

do, and the Duke commenced an action against him.

The case was tried in June, 1824, in the Court of Common

Pleas. It was ludicrous to hear the extravagant terms in which

the counsel for the plaintiff and his witnesses described the

nuisance—the noise made by the engine in the underground cellar,

sometimes like thunder, at other times like a thrashing-machine, and

then again like the rumbling of carts and waggons. The printer

had retained the Attorney-General, Mr. Copley, afterwards Lord

Lyndhurst, who conducted his case with surpassing ability. The

cross-examination of a foreign artist, employed by the Duke to

repaint some portraits of the Cornaro family by Titian, is said to

have been one of the finest things on record. The sly and

pungent humour, and the banter with which the counsel derided and

laughed down this witness, were inimitable. The printer won

his case; but he eventually consented to remove his steam presses

from the neighbourhood, on the Duke paying him a certain sum to be

determined by the award of arbitrators.

It happened, about this period, that a sort of murrain fell

upon the London publishers. After the failure of Constable at

Edinburgh, they came down one after another, like a pack of cards.

Authors are not the only people who lose labour and money by

publishers; there are also cases where publishers are ruined by

authors. Printers also now lost heavily. In one week,

Mr. Clowes sustained losses through the failure of London publishers

to the extent of about £25,000. Happily, the large sum which

the arbitrators awarded him for the removal of his printing presses

enabled him to tide over the difficulty; he stood his ground

unshaken, and his character in the trade stood higher than ever.

In the following year Mr. Clowes removed to Duke Street,

Blackfriars, to premises until then occupied by Mr. Applegath, as a

printer; and much more extensive buildings and offices were now

erected. There his business transactions assumed a form of

unprecedented magnitude, and kept pace with the great demand for

popular information which set in with such force about fifty years

ago. In the course of ten years—as we find from the

'Encyclopædia Metropolitana '—there were twenty of Applegath &

Cowper's machines, worked by two five-horse engines. From

these presses were issued the numerous admirable volumes and

publications of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge;

the treatises on 'Physiology,' by Roget, and 'Animal Mechanics,' by

Charles Bell; the 'Elements of Physics,' by Neill Arnott; 'The

Pursuit of Knowledge under Difficulties,' by G. L. Craik, a most

fascinating book; the Library of Useful Knowledge; the 'Penny

Magazine,' the first illustrated publication; and the 'Penny

Cyclopædia,' that admirable compendium of knowledge and science.

These publications were of great value. Some of them

were printed in unusual numbers. The 'Penny Magazine,' of

which Charles Knight was editor, was perhaps too good, because it

was too scientific. Nevertheless, it reached a circulation of

200,000 copies. The 'Penny Cyclopædia' was still better.

It was original, and yet cheap. The articles were written by

the best men that could be found in their special departments of

knowledge. The sale was originally 75,000 weekly; but, as the

plan enlarged, the price was increased from 1d. to 2d., and then to

4d. At the end of the second year, the circulation had fallen

to 44,000; and at the end of the third year, to 20,000.

It was unfortunate for Mr. Knight to be so much under the

influence of his Society. Had the Cyclopædia been under his

own superintendence, it would have founded his fortune. As it

was, he lost over £30,000 by the venture. The 'Penny Magazine'

also went down in circulation, until it became a non-paying

publication, and then it was discontinued. It is curious to

contrast the fortunes of William Chambers of Edinburgh with those of

Charles Knight of London. 'Chambers's Edinburgh Journal' was

begun in February, 1832, and the 'Penny Magazine' in March, 1832.

Chambers was perhaps shrewder than Knight. His journal was as

good, though without illustrations; but he contrived to mix up

amusement with useful knowledge. It may be a weakness, but the

public like to be entertained, even while they are feeding upon

better food. Hence Chambers succeeded, while Knight failed.

The 'Penny Magazine' was discontinued in 1845, whereas 'Chambers's

Edinburgh Journal' has maintained its popularity to the present day.

Chambers, also, like Knight, published an ' Encyclopædia,' which

secured a large circulation. But he was not trammelled by a

Society, and the 'Encyclopædia' has become a valuable property.

The publication of these various works would not have been

possible without the aid of the steam printing press. When Mr.

Edward Cowper was examined before a Committee of the House of

Commons, he said, "The ease with which the principles and

illustrations of Art might be diffused is, I think, so obvious that

it is hardly necessary to say a word about it. Here you may

see it exemplified in the 'Penny Magazine.' Such works as this

could not have existed without the printing machine." He was

asked, "In fact, the mechanic and the peasant, in the most remote

parts of the country, have now an opportunity of seeing tolerably

correct outlines of form which they never could behold before?"

To which he answered, "Exactly; and literally at the price they used

to give for a song." "Is there not, therefore, a greater

chance of calling genius into activity?" "Yes," he said, "not

merely by books creating an artist here and there, but by the

general elevation of the taste of the public."

Mr. Clowes was always willing to promote deserving persons in

his office. One of these rose from step to step, and

eventually became one of the most prosperous publishers in London.

He entered the service as an errand-boy, and got his meals in the

kitchen. Being fond of reading, he petitioned Mrs. Clowes to

let him sit somewhere, apart from the other servants, where he might

read his book in quiet. Mrs. Clowes at length entreated her

husband to take him into the office, for "Johnnie Parker was such a

good boy." He consented, and the boy took his place at a

clerk's desk. He was well-behaved, diligent, and attentive.

As he advanced in years, his steady and steadfast conduct showed

that he could be trusted. Young fellows like these always make

their way in life; for character invariably tells, not only in

securing respect, but in commanding confidence. Parker was

promoted from one post to another, until he was at length appointed

overseer over the entire establishment.

A circumstance shortly after occurred which enabled Mr.

Clowes to advance him, though greatly to his own inconvenience, to

another important post. The Syndics of Cambridge were desirous

that Mr. Clowes should go down there to set their printing-office in

order; they offered him £400 a year if he would only appear

occasionally, and see that the organisation was kept complete.

He declined, because the magnitude of his own operations had now

become so great that they required his unremitting attention.

He, however, strongly recommended Parker to the office, though he

could ill spare him. But he would not stand in the young man's

way, and he was appointed accordingly. He did his work most

effectually at Cambridge, and put the University Press into thorough

working order.

As the 'Penny Magazine' and other publications of the Society

of Useful Knowledge were now making their appearance, the clergy

became desirous of bringing out a religious publication of a popular

character, and they were in search for a publisher. Parker,

who was well known at Cambridge, was mentioned to the Bishop of

London as the most likely person. An introduction took place,

and after an hour's conversation with Parker, the Bishop went to his

friends and said, "This is the very man we want." An offer was

accordingly made to him to undertake the publication of the

'Saturday Magazine' and the other publications of the Christian

Knowledge Society, which he accepted. It is unnecessary to

follow his fortunes. His progress was steady; he eventually

became the publisher of 'Fraser's Magazine' and of the works of John

Stuart Mill and other well-known writers. Mill never forgot

his appreciation and generosity; for when his 'System of Logic' had

been refused by the leading London publishers, Parker prized the

book at its rightful value and introduced it to the public.

To return to Mr. Clowes. In the course of a few years,

the original humble establishment of the Sussex compositor,

beginning with one press and one assistant, grew up to be one of the

largest printing-offices in the world. It had twenty-five

steam presses, twenty-eight hand-presses, six hydraulic presses, and

gave direct employment to over five hundred persons, and indirect

employment to probably more than ten times that number.

Besides the works connected with his printing-office, Mr. Clowes

found it necessary to cast his own types, to enable him to command

on emergency any quantity; and to this he afterwards added

stereotyping on an immense scale. He possessed the power of

supplying his compositors with a stream of new type at the rate of

about 50,000 pieces a day. In this way, the weight of type in

ordinary use became very great; it amounted to not less than 500

tons, and the stereotyped plates to about 2,500 tons—the value of

the latter being not less than half a million sterling.

Mr. Clowes would not hesitate, in the height of his career,

to have tons of type locked up for months in some ponderous

blue-book. To print a report of a hundred folio pages in the

course of a day or during a night, or of a thousand pages in a week,

was no uncommon occurrence. From his gigantic establishment

were turned out not fewer than 725,000 printed sheets, or equal to

30,000 volumes a week. Nearly 45,000 pounds of paper were

printed weekly. The quantity printed on both sides per week,

if laid down in a path of 22¼ inches broad, would extend 263 miles

in length.

About the year 1840, a Polish inventor brought out a

composing machine, and submitted it to Mr. Clowes for approval.

But Mr. Clowes was getting too old to take up and push any new

invention. He was also averse to doing anything to injure the

compositors, having once been a member of the craft. At the

same time he said to his son George, "If you find this to be a

likely machine, let me know. Of course we must go with the

age. If I had not started the steam press when I did, where

should I have been now?" On the whole, the composing machine,

though ingenious, was incomplete, and did not come into use at that

time, nor indeed for a long time after. Still, the idea had

been born, and, like other inventions, became eventually developed

into a useful working machine. Composing machines are now in

use in many printing-offices, and the present Clowes' firm possesses

several of them. Those in The Times newspaper office

are perhaps the most perfect of all.

Mr. Clowes was necessarily a man of great ability, industry,

and energy. Whatever could be done in printing, that he would

do. He would never admit the force of any difficulty that

might be suggested to his plans. When he found a person ready

to offer objections, he would say, "Ah! I see you are a

difficulty-maker: you will never do for me."

Mr. Clowes died in 1847, at the age of sixty-eight.

There still remain a few who can recall to mind the giant figure,

the kindly countenance, and the gentle bearing of this "Prince of

Printers," as he was styled by the members of his craft. His

life was full of hard and useful work; and it will probably be

admitted that, as the greatest multiplier of books in his day, and

as one of the most effective practical labourers for the diffusion

of useful knowledge, his name is entitled to be permanently

associated, not only with the industrial, but also with the

intellectual development of our time.

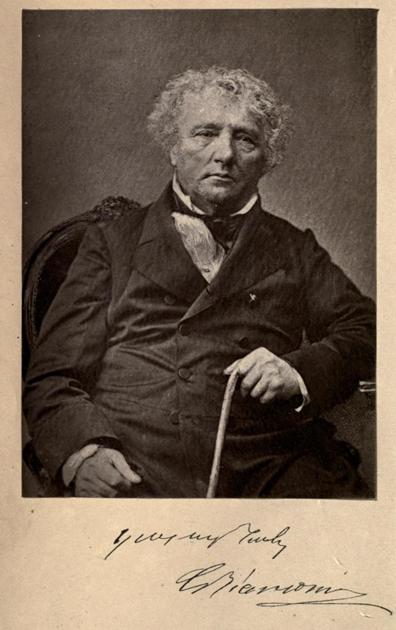

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IX.

CHARLES

BIANCONI (1786-1875):

an Italian, famous for his transport innovations

in Ireland

Picture: Internet Text Archive

____________________

CHARLES BIANCONI:

A LESSON OF SELF-HELP

IN IRELAND.

"I beg you to occupy yourself in collecting

biographical notices respecting the Italians who have honestly

enriched themselves in other regions, particularly referring to the

obstacles of their previous life, and to the efforts and the means

which they employed for vanquishing them, as well as to the

advantages which they secured for themselves, for the countries in

which they settled, and for the country to which they owed their

birth.''—GENERAL MENABREA,

Circular to Italian Consuls.

WHEN Count

Menabrea was Prime Minister of Italy, he caused a despatch to be

prepared and issued to Italian Consuls in all parts of the world,

inviting them to collect and forward to him "biographical notices

respecting the Italians who have honourably advanced themselves in

foreign countries."

His object, in issuing the despatch, was to collect information as

to the lives of his compatriots living abroad, in order to bring out

a book similar to 'Self-Help,' the examples cited in which were to

be drawn exclusively from the lives of Italian citizens. Such a

work, he intimated, "if it were once circulated among the masses,

could not fail to excite their emulation and encourage them to

follow the examples therein set forth," while "in the course of time

it might exercise a powerful influence on the increased greatness of

our country."

We are informed by Count Menabrea that, although no special work has

been published from the biographical notices collected in answer to

his despatch, yet that the Volere è Potere ('Will is Power')

of Professor Lessona, issued a few years ago, sufficiently answers

the purpose which he contemplated, and furnishes many examples of

the patient industry and untiring perseverance of Italians in all

parts of the world. Many important illustrations of life and

character are necessarily omitted from Professor Lessona's

interesting work. Among these may be mentioned the subject of the

following pages,—a distinguished Italian who entirely corresponds to

Count Menabrea's description—one who, in the face of the greatest

difficulties, raised himself to an eminent public position, at the

same time that he conferred the greatest benefits upon the country

in which he settled and carried on his industrial operations. We

mean Charles Bianconi, and his establishment of the great system of

car communication throughout Ireland. [p.221]

Charles Bianconi was born in 1786, at the village of Tregolo,

situated in the Lombard Highlands of La Brianza, about ten miles

from Como. The last elevations of the Alps disappear in the

district; and the great plain of Lombardy extends towards the south. The region is known for its richness and beauty; the inhabitants

being celebrated for the cultivation of the mulberry and the rearing

of the silkworm, the finest silk in Lombardy being produced in the

neighbourhood. Indeed, Bianconi's family, like most of the

villagers, maintained themselves by the silk culture.

Charles had three brothers and one sister. When of a sufficient age,

he was sent to school. The Abbé Radicali had turned out some good

scholars; but with Charles Bianconi his failure was complete. The

new pupil proved a tremendous dunce. He was very wild, very bold,

and very plucky; but he learned next to nothing. Learning took as

little effect upon him as pouring water upon a duck's back. Accordingly, when he left school at the age of sixteen, he was

almost as ignorant as when he had entered it; and a great deal more

wilful.

Young Bianconi had now arrived at the age at which he was expected

to do something for his own maintenance. His father wished to throw

him upon his own resources; and as he would soon be subject to the

conscription, he thought of sending him to some foreign country in

order to avoid the forced service. Young fellows, who had any love

of labour or promptings of independence in them, were then

accustomed to leave home and carry on their occupations abroad. It

was a common practice for workmen in the neighbourhood of Como to

emigrate to England and carry on various trades; more particularly

the manufacture and sale of barometers, looking-glasses, images,

prints, pictures, and other articles.

Accordingly, Bianconi's father arranged with one Andrea Faroni to

take the young man to England, and instruct him in the trade of

print-selling. Bianconi was to be Faroni's apprentice for eighteen

months; and in the event of his not liking the occupation, he was to

be placed under the care of Colnaghi, a friend of his father's, who

was then making considerable progress as a print-seller in London;

and who afterwards succeeded in achieving a considerable fortune and

reputation.

Bianconi made his preparations for leaving home. A little festive

entertainment was given at a little inn in Como, at which the whole

family were present. It was a sad thing for Bianconi's mother to

take leave of her boy, wild though he was. On the occasion of this

parting ceremony, she fainted outright, at which the young fellow

thought that things were assuming a rather serious aspect. As he

finally left the family home at Tregolo, the last words his mother

said to him were these—words which he never forgot: "When you

remember me, think of me as waiting at this window, watching for

your return."

Besides Charles Bianconi, Faroni took three other boys under his

charge. One was the son of a small village innkeeper, another the

son of a tailor, and the third the son of a flax-dealer. This party,

under charge of the Padre, ascended the Alps by the Val San Giacomo

road. From the summit of the pass they saw the plains of Lombardy

stretching) away in the blue distance. They soon crossed the Swiss

frontier, and then Bianconi found himself finally separated from

home. He now felt, that without further help from friends or

relatives, he had his own way to make in the world.

The party of travellers duly reached England; but Faroni, without

stopping in London, took them over to Ireland at once. They reached

Dublin in the summer of 1802, and lodged in Temple Bar, near Essex

Bridge. It was some little time before Faroni could send out the

boys to sell pictures. First he had the leaden frames to cast; then

they had to be trimmed and coloured; and then the pictures—mostly of

sacred subjects, or of public characters—had to be mounted. The

flowers, which were of wax, had also to be prepared and finished,

ready for sale to the passers-by.

When Bianconi went into the streets of Dublin to sell his mounted

prints, he could not speak a word of English. He could only say,

"Buy, buy!" Everybody spoke to him an unknown tongue. When asked the

price, he could only indicate by his fingers the number of pence he

wanted for his goods. At length he learned a little English,—at

least sufficient "for the road;" and then he was sent into the

country to sell his merchandize. He was despatched every Monday

morning with about forty shillings' worth of stock, and ordered to

return home on Saturdays, or as much sooner as he liked, if he had

sold all the pictures. The only money his master allowed him at

starting was four-pence. When Bianconi remonstrated at the smallness

of the amount, Faroni answered, "While you have goods you have

money; make haste to sell your goods!"

During his apprenticeship, Bianconi learnt much of the country

through which he travelled. He was constantly making acquaintances

with new people, and visiting new places. At Waterford he did a good

trade in small prints. Besides the Scripture pieces, he sold

portraits of the Royal Family, as well as of Bonaparte and his most

distinguished generals. "Bony" was the dread of all magistrates,

especially in Ireland. At Passage, near Waterford, Bianconi was

arrested for having sold a leaden framed picture of the famous

French Emperor. He was thrown into a cold guard-room, and spent the

night there without bed, or fire, or food. Next morning he was

discharged by the magistrate, but cautioned that he must not sell

any more of such pictures.

Many things struck Bianconi in making his first journeys through

Ireland. He was astonished at the dram-drinking of the men, and the

pipe-smoking of the women. The violent faction-fights which took

place at the fairs which he frequented, were of a kind which he had

never before observed among the pacific people of North Italy. These

faction-fights were the result, partly of dram-drinking, and partly

of the fighting mania which then prevailed in Ireland. There were

also numbers of crippled and deformed beggars in every town,—quarrelling and fighting in the streets,—rows and drinkings at

wakes,—gambling, duelling, and riotous living amongst all classes

of the people,—things which could not but strike any ordinary

observer at the time, but which have now, for the most part, happily

passed away.

At the end of eighteen months, Bianconi's apprenticeship was out;

and Faroni then offered to take him back to his father, in

compliance with the original understanding. But Bianconi had no wish

to return to Italy. Faroni then made over to him the money he had

retained on his account, and Bianconi set up business for himself. He was now about eighteen years old; he was strong and healthy, and

able to walk with a heavy load on his back from twenty to thirty

miles a day. He bought a large case, filled it with coloured prints

and other articles, and started from Dublin on a tour through the

south of Ireland. He succeeded, like most persons who labour

diligently. The curly-haired Italian lad became a general favourite. He took his native politeness with him everywhere; and made many

friends among his various customers throughout the country.

Bianconi used to say that it was about this time—when he was

carrying his heavy case upon his back, weighing at least a hundred

pounds—that the idea began to strike him, of some cheap method of

conveyance being established for the accommodation of the poorer

classes in Ireland. As he dismantled himself of his case of

pictures, and sat wearied and resting on the milestones along the

road, he puzzled his mind with the thought, "Why should poor people

walk and toil, and rich people ride and take their ease? Could not

some method be devised by which poor people also might have the

opportunity of travelling comfortably?"

It will thus be seen that Bianconi was already beginning to think

about the matter. When asked, not long before his death, how it was

that he had first thought of starting his extensive Car

establishment, he answered, "It grew out of my back!" It was

the hundredweight of pictures on his dorsal muscles that stimulated

his thinking faculties. But the time for starting his great

experiment had not yet arrived.

Bianconi wandered about from town to town for nearly two years. The

picture-case became heavier than ever. For a time he replaced it

with a portfolio of unframed prints. Then he became tired of the

wandering life, and in 1806 settled down at Carrick-on-Suir as a

print-seller and carver and gilder. He supplied himself with

gold-leaf from Waterford, to which town he used to proceed by Tom

Morrissey's boat. Although the distance by road between the towns

was only twelve miles, it was about twenty-four by water, in

consequence of the windings of the river Suir. Besides, the boat

could only go when the state of the tide permitted. Time was of

little consequence; and it often took half a day to make the

journey. In the course of one of his voyages, Bianconi got himself

so thoroughly soaked by rain and mud that he caught a severe cold,

which ran into pleurisy, and laid him up for about two months. He

was carefully attended to by a good, kind physician, Dr. White, who

would not take a penny for his medicine and nursing.

Business did not prove very prosperous at Carrick-on-Suir; the town

was small, and the trade was not very brisk. Accordingly, Bianconi

resolved, after a year's ineffectual trial, to remove to Waterford,

a more thriving centre of operations. He was now twenty-one years

old. He began again as a carver and gilder; and as business flowed

in upon him, he worked very hard, sometimes from six in the morning

until two hours after midnight. As usual, he made many friends. Among the best of them was Edward Rice, the founder of the

"Christian Brothers" in Ireland. Edward Rice was a true benefactor

to his country. He devoted himself to the work of education, long

before the National Schools were established; investing the whole of

his means in the foundation and management of this noble

institution.

Mr. Rice's advice and instruction set and kept Bianconi in the right

road. He helped the young foreigner to learn English. Bianconi was

no longer a dunce, as he had been at school; but a keen, active,

enterprising fellow, eager to make his way in the world. Mr. Rice

encouraged him to be sedulous and industrious, urged him to

carefulness and sobriety, and strengthened his religious

impressions. The help and friendship of this good man, operating

upon the mind and soul of a young man, whose habits of conduct and

whose moral and religious character were only in course of

formation, could not fail to exercise, as Bianconi always

acknowledged they did, a most powerful influence upon the whole of

his after life.

Although "three removes" are said to be "as bad as a fire,"

Bianconi, after remaining about two years at Waterford, made a third

removal in 1809, to Clonmel, in the county of Tipperary. Clonmel is

the centre of a large corn trade, and is in water communication, by

the Suir, with Carrick and Waterford. Bianconi, therefore, merely

extended his connection; and still continued his dealings with his

customers in the other towns. He made himself more proficient in the

mechanical part of his business; and aimed at being the first carver

and gilder in the trade. Besides, he had always an eye open for new

business. At that time, when the war was raging with France, gold

was at a premium. The guinea was worth about twenty-six or

twenty-seven shillings. Bianconi therefore began to buy up the

hoarded-up guineas of the peasantry. The loyalists became alarmed at

his proceedings, and began to circulate the report that Bianconi,

the foreigner, was buying up bullion to send secretly to Bonaparte!

The country people, however, parted with their guineas readily; for

they had no particular hatred of "Bony," but rather admired him.

Bianconi's conduct was of course quite loyal in the matter; he

merely bought the guineas as a matter of business, and sold them at

a profit to the bankers.

The country people had a difficulty in pronouncing his name. His

shop was at the corner of Johnson Street, and instead of Bianconi,

he came to be called "Bian of the Corner." He was afterwards known

as "Bian."

Bianconi soon became well known after his business was established. He became a proficient in the carving and gilding line, and was

looked upon as a thriving man. He began to employ assistants in his

trade, and had three German gilders at work. While they were working

in the shop he would travel about the country, taking orders and

delivering goods—sometimes walking and sometimes driving.

He still retained a little of his old friskiness and spirit of

mischief. He was once driving a car from Clonmel to Thurles; he had

with him a large looking-glass with a gilt frame, on which about a

fortnight's labour had been bestowed. In a fit of exuberant humour

he began to tickle the horse under his tail with a straw! In an

instant the animal reared and plunged, and then set off at a gallop

down hill. The result was, that the car was dashed to bits and the

looking-glass broken into a thousand atoms!

On another occasion, a man was carrying to Cashel on his back one of

Bianconi's large looking-glasses. An old woman by the wayside,

seeing the odd-looking, unwieldy package, asked what it was; on

which Bianconi, who was close behind the man carrying the glass,

answered that it was "the Repeal of the Union!" The old woman's

delight was unbounded! She knelt down on her knees in the middle of

the road, as if it had been a picture of the Madonna, and thanked

God for having preserved her in her old age to see the Repeal of the

Union!

But this little waywardness did not last long. Bianconi's wild oats

were soon all sown. He was careful and frugal. As he afterwards used

to say, "When I was earning a shilling a day at Clonmel, I lived

upon eight-pence." He even took lodgers, to relieve him of the

charge of his household expenses. But as his means grew, he was

soon able to have a conveyance of his own. He first started a yellow

gig, in which he drove about from place to place, and was everywhere

treated with kindness and hospitality. He was now regarded as

"respectable," and as a person worthy to hold some local office. He

was elected to a Society for Visiting the Sick Poor, and became a

Member of the House of Industry. He might have gone on in the same

business, winning his way to the Mayoralty of Clonmel, which he

afterwards held; but that the old idea, which had first sprung up in

his mind while resting wearily on the milestones along the road,

with his heavy case of pictures by his side, again laid hold of him,

and he determined now to try whether his plan could not be carried

into effect.

He had often lamented the fatigue that poor people had to undergo in

travelling with burdens from place to place upon foot, and wondered

whether some means might not be devised for alleviating their

sufferings. Other people would have suggested "the Government!" Why

should not the Government give us this, that, and the other,—give us

roads, harbours, carriages, boats, nets, and so on. This, of course,

would have been a mistaken idea; for where people are too much

helped, they invariably lose the beneficent practice of helping

themselves. Charles Bianconi had never been helped, except by advice

and friendship. He had helped himself throughout; and now he would

try to help others.

The facts were patent to everybody. There was not an Irishman who

did not know the difficulty of getting from one town to another. There were roads between them, but no conveyances. There was an

abundance of horses in the country, for at the close of the war an

unusual number of horses, bred for the army, were thrown upon the

market. Then a tax had been levied upon carriages, which sent a

large number of jaunting-cars out of employment.

The roads of Ireland were on the whole good, being at that time

quite equal, if not superior, to most of those in England. The facts

of the abundant horses, the good roads, the number of unemployed

outside cars, were generally known; but until Bianconi took the

enterprise in hand, there was no person of thought, or spirit, or

capital in the country, who put these three things together—horses,

roads, and cars—and dreamt of remedying the great public

inconvenience.

It was left for our young Italian carver and gilder, a struggling

man of small capital, to take up the enterprise, and show what could

be done by prudent action and persevering energy. Though the car

system originally "grew out of his back," Bianconi had long been

turning the subject over in his mind. His idea was, that we should

never despise small interests, nor neglect the wants of poor people. He saw the mail-coaches supplying the requirements of the rich, and

enabling them to travel rapidly from place to place. "Then," said he

to himself, "would it not be possible for me to make an ordinary

two-wheeled car pay, by running as regularly for the accommodation

of poor districts and poor people?"

When Mr. Wallace, chairman of the Select Committee on Postage, in

1838, asked Mr. Bianconi, "What induced you to commence the car

establishment?" his answer was, "I did so from what I saw, after

coming to this country, of the necessity for such cars, inasmuch as

there was no middle mode of conveyance, nothing to fill up the

vacuum that existed between those who were obliged to walk and those

who posted or rode. My want of knowledge of the language gave me

plenty of time for deliberation, and in proportion as I grew up with

the knowledge of the language and the localities, this vacuum

pressed very heavily upon my mind, till at last I hit upon the idea

of running jaunting-cars, and for that purpose I commenced running

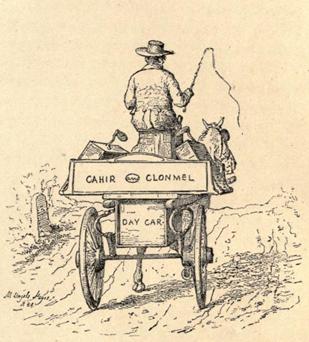

one between Clonmel and Cahir." [p.231]

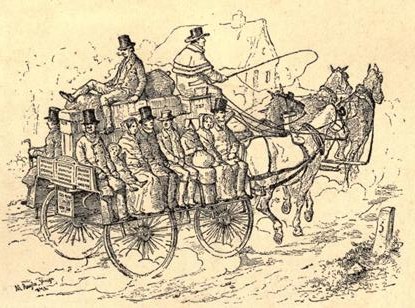

A Bianconi car

Picture: Internet Text Archive

What a happy thing it was for Bianconi and Ireland that he could not

speak with facility,—that he did not know the language or the

manners of the country! In his case silence was "golden." Had he

been able to talk like the people about him, he might have said much

and done little,—attempted nothing and consequently achieved

nothing. He might have got up a meeting and petitioned Parliament to

provide the cars, and subvention the car system; or he might have

gone amongst his personal friends, asked them to help him, and

failing their help, given up his idea in despair, and sat down

grumbling at the people and the Government.

But instead of talking, he proceeded to doing, thereby illustrating

Lessona's maxim of Volere è potere. After thinking the

subject fully over, he trusted to self-help. He found that with his

own means, carefully saved, he could make a beginning; and the

beginning once made, included the successful ending.

The beginning, it is true, was very small. It was only an ordinary

jaunting-car, drawn by a single horse, capable of accommodating six

persons. The first car ran between Clonmel and Cahir, a distance of

about twelve miles, on the 5th of July, 1815—a memorable day for

Bianconi and Ireland. Up to that time the public accommodation for

passengers was confined to a few mail and day coaches on the great

lines of road, the fares by which were very high, and quite beyond

the reach of the poorer or middle-class people.

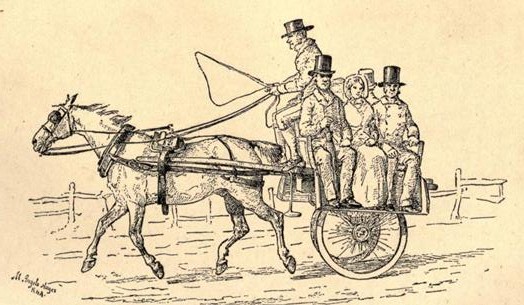

Bianconi—6-person car

Picture: The Internet Text Archive.

People did not know what to make of Bianconi's car when it first

started. There were, of course, the usual prophets of disaster, who

decided that it "would never do." Many thought that no one would pay

eighteen-pence for going to Cahir by car when they could walk there

for nothing? There were others who thought that Bianconi should have

stuck to his shop, as there was no connection whatever between

picture-gilding and car-driving!

The truth is, the enterprise at first threatened to be a failure! Scarcely anybody would go by the car. People preferred trudging on

foot, and saved their money, which was more valuable to them than

their time. The car sometimes ran for weeks without a passenger. Another man would have given up the enterprise in despair. But this

was not the way with Bianconi. He was a man of tenacity and

perseverance. What should he do but start an opposition car? Nobody

knew of it but himself; not even the driver of the opposition car. However, the rival car was started. The races between the

car-drivers, the free lifts occasionally given to passengers, the

cheapness of the fare, and the excitement of the contest, attracted

the attention of the public. The people took sides, and before long

both cars came in full. Fortunately the "great big yallah horse" of

the opposition car broke down, and Bianconi had all the trade to

himself.

The people became accustomed to travelling. They might still walk to

Cahir; but going by car saved their legs, saved their brains, and

saved their time. They might go to Cahir market, do their business

there, and be comfortably back within the day. Bianconi then thought

of extending the car to Tipperary and Limerick. In the course of the

same year, 1815, he started another car between Clonmel, Cashel, and

Thurles. Thus all the principal towns of Tipperary were, in the

first year of the undertaking, connected together by car, besides

being also connected with Limerick.

It was easy to understand the convenience of the car system to

business men, farmers, and even peasants. Before their

establishment, it took a man a whole day to walk from Thurles to

Clonmel, the second day to do his business, and the third to walk

back again; whereas he could, in one day, travel backwards and

forwards between the two towns, and have five or six intermediate

hours for the purpose of doing his business. Thus two clear days

could be saved.

Still carrying out his scheme, Bianconi, in the following year

(1816), put on a car from Clonmel to Waterford. Before that time

there was no car accommodation between Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir,

about half-way to Waterford; but there was an accommodation by boat

between Carrick and Waterford. The distance between the two latter

places was, by road, twelve miles, and by the river Suir twenty-four

miles. Tom Morrissey's boat plied two days a week; it carried from

eight to ten passengers at 6½d. of the then currency; it did the

voyage in from four to five hours, and besides had to wait for the

tide to float it up and down the river. When Bianconi's car was put

on, it did the distance daily and regularly in two hours, at a fare

of two shillings.

The people soon got accustomed to the convenience of the cars. They

also learned from them the uses of punctuality and the value of

time. They liked the open-air travelling and the sidelong motion. The new cars were also safe and well-appointed. They were drawn by

good horses and driven by good coachmen. Jaunting-car travelling had

before been rather unsafe. The country cars were of a ramshackle

order, and the drivers were often reckless. "Will I pay the pike, or

drive at it, plaise your honour?" said a driver to his passenger on

approaching a turnpike-gate. Sam Lover used to tell a story of a

car-driver, who, after driving his passenger up-hill and down-hill,

along a very bad road, asked him for something extra at the end of

his journey. "Faith," said the driver, "its not putting me off with

this ye'd be, if ye knew but all." The gentleman gave him another

shilling. "And now what do you mean by saying, 'if ye knew but

all?'" "That I druv yer honor the last three miles widout a

linch-pin!"

Bianconi, to make sure of the soundness and safety of his cars, set

up a workshop to build them for himself. He could thus depend upon

their soundness, down even to the linch-pin itself. He kept on his

carving and gilding shop until his car business had increased so

much that it required the whole of his time and attention; and then

he gave it up. In fact, when he was able to run a car from Clonmel

to Waterford—a distance of thirty-two miles—at a fare of

three-and-sixpence, his eventual triumph was secure.

He made Waterford one of the centres of his operations, as he had

already made Clonmel. In 1818 he established a car between Waterford

and Ross, in the following year a car between Waterford and Wexford,

and another between Waterford and Enniscorthy. A few years later he

established other cars between Waterford and Kilkenny, and Waterford

and Dungarvan. From these furthest points, again, other cars were

established in communication with them, carrying the line further

north, east, and west. So much had the travelling between Clonmel

and Waterford increased, that in a few years (instead of the eight

or ten passengers conveyed by Tom Morrissey's boat on the Suir)

there was horse and car power capable of conveying a hundred

passengers daily between the two places.

Bianconi did a great stroke of business at the Waterford election of

1826. Indeed it was the turning point of his fortunes. He was at

first greatly cramped for capital. The expense of maintaining and

increasing his stock of cars, and of foddering his horses was very

great; and he was always on the look-out for more capital. When the

Waterford election took place, the Beresford party, then

all-powerful, engaged all his cars to drive the electors to the

poll. The popular party, however, started a candidate, and applied

to Bianconi for help. But he could not comply, for his cars were

all engaged. The morning after his refusal of the application,

Bianconi was pelted with mud. One or two of his cars and horses were

heaved over the bridge.

Bianconi then wrote to Beresford's agent, stating that he could no

longer risk the lives of his drivers and his horses, and desiring to

be released from his engagement. The Beresford party had no desire

to endanger the lives of the car-drivers or their horses, and they

set Bianconi free. He then engaged with the popular party, and

enabled them to win the election. For this he was paid the sum of a

thousand pounds. This access of capital was greatly helpful to him

under the circumstances. He was able to command the market, both for

horses and fodder. He was also placed in a position to extend the

area of his car routes.

He now found time, amidst his numerous avocations, to get married! He was forty years of age before this event occurred. He married

Eliza Hayes, some twenty years younger than himself, the daughter of

Patrick Hayes, of Dublin, and of Henrietta Burton, an Englishwoman. The marriage was celebrated on the 14th of February, 1827; and the

ceremony was performed by the late Archbishop Murray. Mr. Bianconi

must now have been in good circumstances, as he settled two thousand

pounds upon his wife on their marriage-day. His early married life

was divided between his cars, electioneering, and Repeal

agitation—for he was always a great ally of O'Connell. Though he

joined in the Repeal movement, his sympathies were not with it; for

he preferred Imperial to Home Rule. But he could never deny himself

the pleasure of following O'Connell, "right or wrong."

Let us give a picture of Bianconi now. The curly-haired Italian boy

had grown a handsome man. His black locks curled all over his head,

like those of an ancient Roman bust. His face was full of power, his

chin was firm, his nose was finely cut and well-formed; his eyes

were keen and sparkling, as if throwing out a challenge to fortune. He was active, energetic, healthy, and strong, spending his time

mostly in the open air. He had a wonderful recollection of faces,

and rarely forgot to recognise the countenance that he had once

seen. He even knew all his horses by name. He spent little of his

time at home, but was constantly rushing about the country after

business, extending his connections, organizing his staff, and

arranging the centres of his traffic.

To return to the car arrangements. A line was early opened from

Clonmel—which was at first the centre of the entire connection—to

Cork; and that line was extended northward, through Mallow and

Limerick. Then, the Limerick car went on to Tralee, and from thence

to Cahirciveen, on the south-west coast of Ireland. The cars were

also extended northward from Thurles to Roscrea, Ballinasloe,

Athlone, Roscommon, and Sligo, and to all the principal towns in the

north-west counties of Ireland.

The cars interlaced with each other, and plied, not so much in

continuous main lines, as across country, so as to bring all

important towns, but especially the market towns, into regular daily

communication with each other. Thus, in the course of about thirty

years, Bianconi succeeded in establishing a system of internal

communication in Ireland, which traversed the main highways and

cross-roads from town to town, and gave the public a regular and

safe car accommodation at the average rate of a penny-farthing per

mile.

The traffic in all directions steadily increased. The first car used

was capable of accommodating only six persons. This was between

Clonmel and Cahir. But when it went on to Limerick, a larger car was

required. The traffic between Clonmel and Waterford was also begun

with a small-sized car. But in the course of a few years, there were

four large-sized cars, travelling daily each way, between the two

places. And so it was in other directions, between Cork in the

south; and Sligo and Strabane in the north and north-west; between

Wexford in the east, and Galway and Skibbereen in the west and

south-west.

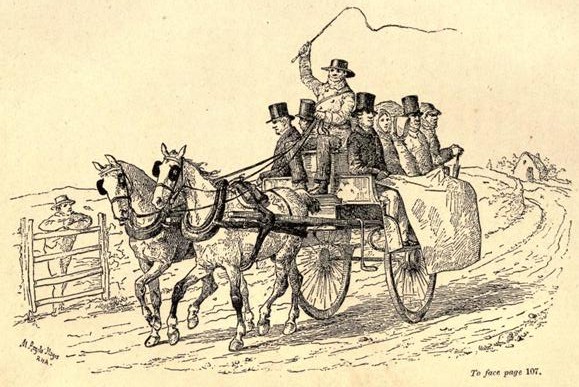

Bianconi—10-person car

Picture: The Internet Text Archive

Bianconi first increased the accommodation of these cars so as to

carry four persons on each side instead of three, drawn by two

horses. But as the two horses could quite as easily carry two

additional passengers, another piece was added to the car so as to

carry five passengers. Then another four-wheeled car was built,

drawn by three horses, so as to carry six passengers on each side. And lastly, a fourth horse was used, and the car was further

enlarged, so as to accommodate seven, and eventually eight

passengers on each side, with one on the box, which made a total

accommodation for seventeen passengers. The largest and heaviest of

the long cars, on four wheels, was called "Finn MacCoul's," after

Ossian's Giant; the fast cars, of a light build, on two wheels, were

called "Faugh-a-ballagh," or "clear the way"; while the intermediate

cars were named "Massey Dawsons," after a popular Tory squire.

A "Finn MacCoul"

Picture: The Internet Text Archive

When Bianconi's system was complete, he had about a hundred vehicles

at work; a hundred and forty stations for changing horses, where

from one to eight grooms were employed; about a hundred drivers,

thirteen hundred horses, performing an average distance of three

thousand eight hundred miles daily; passing through twenty-three

counties, and visiting no fewer than a hundred and twenty of the

principal towns and cities in the south and west and midland

counties of Ireland. Bianconi's horses consumed on an average from

three to four thousand tons of hay yearly, and from thirty to forty

thousand barrels of oats, all of which were purchased in the

respective localities in which they were grown.

Bianconi's cars—or "The Bians"—soon became very popular. Everybody

was under obligations to them. They greatly promoted the improvement

of the country. People could go to market and buy or sell their

goods more advantageously. It was cheaper for them to ride than to

walk. They brought the whole people of the country so much nearer to

each other. They virtually opened up about seven-tenths of Ireland

to civilisation and commerce, and among their other advantages, they

opened markets for the fresh fish caught by the fishermen of Galway, Clifden, Westport, and other places, enabling them to be sold

throughout the country on the day after they were caught. They also

opened the magnificent scenery of Ireland to tourists, and enabled

them to visit Bantry Bay, Killarney, South Donegal, and the wilds of

Connemara in safety, all the year round.

Bianconi's service to the public was so great, and it was done with

so much tact, that nobody had a word to say against him. Everybody

was his friend. Not even the Whiteboys [p.239] would injure him or the mails

he carried. He could say with pride, that in the most disturbed

times his cars had never been molested. Even during the Whiteboy

insurrection, though hundreds of people were on the roads at night,

the traffic went on without interference. At the meeting of the

British Association in 1857, Bianconi said: "My conveyances, many of

them carrying very important mails, have been travelling during all

hours of the day and night, often in lonely and unfrequented places;

and during the long period of forty-two years that my establishment

has been in existence, the slightest injury has never been done by

the people to my property, or that entrusted to my care; and this

fact gives me greater pleasure than any pride I might feel in

reflecting upon the other rewards of my life's labour."

Of course Bianconi's cars were found of great use for carrying the

mails. The post was, at the beginning of his enterprise, very badly

served in Ireland, chiefly by foot and horse posts. When the first

car was run from Clonmel to Cahir, Bianconi offered to carry the

mail for half the price then paid for "sending it alternately by a

mule and a bad horse." The post was afterwards found to come

regularly instead of irregularly to Cahir; and the practice of

sending the mails by Bianconi's cars increased from year to year. Dispatch won its way to popularity in Ireland as elsewhere, and Bianconi lived to see all the cross-posts in Ireland arranged on his

system.

The postage authorities frequently used the cars of Bianconi as a

means of competing with the few existing mail-coaches. For instance,

they asked him to compete for carrying the post between Limerick and

Tralee, then carried by a mail-coach. Before tendering, Bianconi

called on the contractor, to induce him to give in to the

requirements of the Post Office, because he knew that the postal

authorities only desired to make use of him to fight the coach

proprietors. But having been informed that it was the intention of

the Post Office to discontinue the mail-coach whether Bianconi took

the contract or not, he at length sent in his tender, and obtained

the contract.

He succeeded in performing the service, and delivered the mail much

earlier than it had been done before. But the former contractor,

finding that he had made a mistake, got up a movement in favour of

re-establishing the mail-coach upon that line of road; and he

eventually induced the postage authorities to take the mail contract

out of the hands of Bianconi, and give it back to himself, as

formerly. Bianconi, however, continued to keep his cars upon the

road. He had before stated to the contractor, that if he once

started his cars, he would not leave it, even though the contract

were taken from him. Both coach and car therefore ran for years upon

the road, each losing thousands of pounds. "But," said Bianconi,

when asked about the matter by the Committee on Postage in 1838, "I

kept my word: I must either lose character by breaking my word, or

lose money. I prefer losing money to giving up the line of road."

Bianconi had also other competitors to contend with, especially from

coach and car proprietors. No sooner had he shown to others the way

to fortune, than he had plenty of imitators. But they did not

possess his rare genius for organisation, nor perhaps his still

rarer principles. They had not his tact, his foresight, his

knowledge, nor his perseverance. When Bianconi was asked by the

Select Committee on Postage, "Do the opposition cars started against

you induce you to reduce your fares?" his answer was, "No; I seldom

do. Our fares are so close to the first cost, that if any man runs

cheaper than I do, he must starve off, as few can serve the public

lower and better than I do." [p.242-1]

Bianconi was once present at a meeting of car proprietors, called

for the purpose of uniting to put down a new opposition coach. Bianconi would not concur, but protested against it, saying, "If car

proprietors had united against me when I started, I should have been

crushed. But is not the country big enough for us all?" The coach

proprietors, after many angry words, threatened to unite in running

down Bianconi himself. "Very well," he said, "you may run me off the

road—that is possible; but while there is this" (pulling a flower

out of his coat) "you will not put me down." The threat

merely ended in smoke, the courage and perseverance of Bianconi

having long since become generally recognised.

We have spoken of the principles of Mr. Bianconi. They were most

honourable. His establishment might be spoken of as a school of

morality. In the first place, he practically taught and enforced the

virtues of punctuality, truthfulness, sobriety, and honesty. He also

taught the public generally the value of time, to which, in fact,

his own success was in a great measure due. While passing through Clonmel in 1840, Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Hall

[p.242-2] called upon Bianconi and

went over his establishment, as well as over his house and farm, a

short distance from the town. The travellers had a very pressing

engagement, and could not stay to hear the story of how their

entertainer had contrived to "make so much out of so little." "How

much time have you?" he asked. "Just five minutes." "The car," says

Mr. Hall, "had conveyed us to the back entrance. Bianconi instantly

rang the bell, and said to the servant, 'Tell the driver to bring

the car round to the front,' adding, 'that will save one minute,

and enable me to tell you all within the time.' This was, in truth

the secret of his success, making the most of time." [p.243-1]

But the success of Bianconi was also due to the admirable principles

on which his establishment was conducted. His drivers were noted as

being among the most civil and obliging men in Ireland, besides

being pleasant companions to boot. They were careful, punctual,

truthful, and honest; but all this was the result of strict

discipline on the part of their master.

The drivers were taken from the lowest grades of the establishment,

and promoted to higher positions according to their respective

merits as opportunity offered. "Much surprise," says Bianconi, "has often been expressed at the high order of men connected with my

car establishment and at its popularity; but parties thus expressing

themselves forget to look at Irish society with sufficient grasp. For my part, I cannot better compare it than to a man merging to

convalescence from a serious attack of malignant fever, and

requiring generous nutrition in place of medical treatment." [p.243-2]

To attach the men to the system, as well as to confer upon them the

due reward for their labour, he provided for all the workmen who had

been injured, worn out, or become superannuated in his service. The

drivers could then retire upon a full pension, which they enjoyed

during the rest of their lives. They were also paid their full wages

during sickness, and at their death Bianconi educated their

children, who grew up to manhood, and afterwards filled the

situations held by their deceased parents.

Every workman had thus a special interest in his own good conduct. They knew that nothing but misbehaviour could deprive them of the

benefits they enjoyed; and hence their endeavours to maintain their

positions by observing the strict discipline enjoined by their

employer.

Sobriety was, of course, indispensable —a drunken car-driver being

amongst the most dangerous of servants. The drivers must also be

truthful, and the man found telling a lie, however venial, was

instantly dismissed. Honesty was also strongly enforced, not only

for the sake of the public, but for the sake of the men themselves. Hence he never allowed his men to carry letters. If they did so, he

fined them in the first instance very severely, and in the second

instance dismissed them. "I do so," he said, "because if I do not

respect other institutions (the Post Office), my men will soon learn

not to respect my own. Then, for carrying letters during the extent

of their trip, the men most probably would not get money, but drink,

and hence become dissipated and unworthy of confidence."

Thus truth, accuracy, punctuality, sobriety, and honesty being

strictly enforced, formed the fundamental principle of the entire

management. At the same time, Bianconi treated his drivers with

every confidence and respect. He made them feel that, in doing their

work well, they conferred a greater benefit on him and on the public

than he did on them by paying them their wages.

When attending the British Association at Cork, Bianconi said that,

"in proportion as he advanced his drivers, he lowered their wages."

"Then," said Dr. Taylor, the Secretary, "I wouldn't like to serve

you." "Yes, you would," replied Bianconi, "because in promoting my

drivers I place them on a more lucrative line, where their certainty

of receiving fees from passengers is greater."

Bianconi was as merciful to his horses as to his men. He had much

greater difficulty at first in finding good men than good horses,

because the latter were not exposed to the temptations to which the

former were subject. Although the price of horses continued to rise,

he nevertheless bought the best horses at increased prices, and he

took care not to work them overmuch. He gave his horses as well as

his men their seventh day's rest. "I find by experience," he said,

"that I can work a horse eight miles a day for six days in the week,

easier than I can work six miles for seven days; and that is one of

my reasons for having no cars, unless carrying a mail, plying upon

Sundays."

Bianconi had confidence in men generally. The result was that men

had confidence in him. Even the Whiteboys respected him. At the

close of a long and useful life be could say with truth, "I never

yet attempted to do an act of generosity or common justice, publicly

or privately, that I was not met by manifold reciprocity."

By bringing the various classes of society into connection with each

other, Bianconi believed, and doubtless with truth, that he was the

means of making them respect each other, and that he thereby

promoted the civilisation of Ireland. At the meeting of the Social

Science Congress, [p.245] held at Dublin in 1861, he said: "The state of the

roads was such as to limit the rate of travelling to about seven

miles an hour, and the passengers were often obliged to walk up

hills. Thus all classes were brought together, and I have felt much

pleasure in believing that the intercourse thus created tended to

inspire the higher classes with respect and regard for the natural

good qualities of the humbler people, which the latter reciprocated

by a becoming deference and an anxiety to please and oblige. Such a

moral benefit appears to me to be worthy of special notice and

congratulation."

Even when railways were introduced, Bianconi did not resist them,

but welcomed them as "the great civilisers of the age." There was,

in his opinion, room enough for all methods of conveyance in

Ireland. When Captain Thomas Drummond was appointed Under-Secretary

for Ireland in 1835, and afterwards chairman of the Irish Railway

Commission, he had often occasion to confer with Mr. Bianconi, who

gave him every assistance. Mr. Drummond conceived the greatest

respect for Bianconi, and often asked him how it was that he, a

foreigner, should have acquired so extensive an influence and so

distinguished a position in Ireland?

"The question came upon me," said Bianconi, "by surprise, and I did

not at the time answer it. But another day he repeated his question,

and I replied, 'Well, it was because, while the big and the little

were fighting, I crept up between them, carried out my enterprise,

and obliged everybody.'" This, however, did not satisfy Mr.

Drummond, who asked Bianconi to write down for him an autobiography,

containing the incidents of his early life down to the period of his

great Irish enterprise. Bianconi proceeded to do this, writing down

his past history in the occasional intervals which he could snatch

from the immense business which he still continued personally to

superintend. But before the "Drummond memoir" could be finished

Mr. Drummond himself had ceased to live, having died in

1840, principally of overwork. What he thought of Bianconi, however,

has been preserved in his Report of the Irish Railway Commission of

1838, written by Mr. Drummond himself, in which he thus speaks of

his enterprising friend in starting and conducting the great Irish

car establishment:—

"With a capital little exceeding the expense of outfit he commenced. Fortune, or rather the due reward of industry and integrity,

favoured his first efforts. He soon began to increase the number of

his cars and multiply routes, until his establishment spread over

the whole of Ireland. These results are the more striking and

instructive as having been accomplished in a district which has long

been represented as the focus of unreclaimed violence and barbarism,

where neither life nor property can be deemed secure. Whilst many

possessing a personal interest in everything tending to improve or

enrich the country have been so misled or inconsiderate as to repel

by exaggerated statements British capital from their doors, this

foreigner chose Tipperary as the centre of his operations, wherein

to embark all the fruits of his industry in a traffic peculiarly

exposed to the power and even to the caprice of the peasantry. The

event has shown that his confidence in their good sense was not

ill-grounded.

"By a system of steady and just treatment he has obtained a complete

mastery, exempt from lawless intimidation or control, over the

various servants and agents employed by him, and his establishment

is popular with all classes on account of its general usefulness and

the fair liberal spirit of its management. The success achieved by

this spirited gentleman is the result, not of a single speculation,

which might have been favoured by local circumstances, but of a

series of distinct experiments, all of which have been successful."

When the railways were actually made and opened, they ran right

through the centre of Bianconi's long-established systems of

communication. They broke up his lines, and sent them to the right

and left. But, though they greatly disturbed him, they did not

destroy him. In his enterprising hands the railways merely changed

the direction of the cars. He had at first to take about a thousand

horses off the road, with thirty-seven vehicles, travelling 2,446

miles daily. But he remodelled his system so as to run his cars

between the railway stations and the towns to the right and left of

the main lines.

He also directed his attention to those parts of Ireland which had

not before had the benefit of his conveyances. And in thus still

continuing to accommodate the public, the number of his horses and

carriages again increased, until, in 1861, he was employing 900

horses, travelling over 4,000 miles daily; and in 1866, when he

resigned his business, he was running only 684 miles daily below the

maximum run in 1845, before the railways had begun to interfere with

his traffic.

His cars were then running to Dungarvan, Waterford, and Wexford in

the south-west of Ireland; to Bandon, Rosscarbery, Skibbereen, and

Cahirciveen, in the south; to Tralee, Galway, Clifden, Westport, and

Belmullet in the west; to Sligo, Enniskillen, Strabane, and

Letterkenny in the north; while, in the centre of Ireland, the towns

of Thurles, Kilkenny, Birr, and Ballinasloe were also daily served

by the cars of Bianconi.

At the meeting of the British Association, [p.248] held in Dublin in 1857,

Mr. Bianconi mentioned a fact which he thought, illustrated the

increasing prosperity of the country and the progress of the people.

It was, that although the population had so considerably decreased

by emigration and other causes, the proportion of travellers by his

conveyances continued to increase, demonstrating not only that the

people had more money, but that they appreciated the money value of

time, and also the advantages of the car system established for

their accommodation.

Although railways must necessarily have done much to promote the

prosperity of Ireland, it is very doubtful whether the general

passenger public were not better served by the cars of Bianconi than

by the railways which superseded them. Bianconi's cars were on the

whole cheaper, and were always run en correspondence, so as

to meet each other; whereas many of the railway trains in the south

of Ireland, under the competitive system existing between the

several companies, are often run so as to miss each other. The present

working of the Irish railway traffic provokes perpetual irritation

amongst the Irish people, and sufficiently accounts for the frequent

petitions presented to Parliament that they should be taken in hand

and worked by the State.

Bianconi continued to superintend his great car establishment until

within the last few years. He had a constitution of iron, which he

expended in active daily work. He liked to have a dozen irons in the

fire, all red-hot at once. At the age of seventy he was still a man

in his prime; and he might be seen at Clonmel helping, at busy

times, to load the cars, unpacking and unstrapping the luggage where

it seemed to be inconveniently placed; for he was a man who could

never stand by and see others working without having a hand in it

himself. Even when well on to eighty, he still continued to grapple