|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XI.

SHIPBUILDING IN BELFAST—ITS ORIGIN AND PROGRESS.

BY E. J. HARLAND, ENGINEER

AND SHIPBUILDER. [p.288]

"The useful arts are but

reproductions or new combinations by the art of man, of the same

natural benefactors. He no longer waits for favouring gales,

but by means of steam he realises the fable of Æolus's bag, and

carries the two-and-thirty winds in the boiler of his boat."—EMERSON.

"The most exquisite and the most expensive machinery is

brought into play where operations on the most common materials are

to be performed, because these are executed on the widest scale.

This is the meaning of the vast and astonishing prevalence of

machine work in this country: that the machine, with its million

fingers, works for millions of purchasers, while in remote

countries, where magnificence and savagery stand side by side, tens

of thousands work for one. There Art labours for the rich

alone; here she works for the poor no less. There the

multitude produce only to give splendour and grace to the despot or

the warrior, whose slaves they are, and whom they enrich; here the

man who is powerful in the weapons of peace, capital, and machinery,

uses them to give comfort and enjoyment to the public, whose servant

he is, and thus becomes rich while lie enriches others with his

goods."—WILLIAM WHEWELL,

D.D.

I WAS born at

Scarborough in May, 1831, the sixth of a family of eight. My

father was a native of Rosedale, half-way between Whitby and

Pickering: his nurse was the sister of Captain Scoresby, celebrated

as an Arctic explorer. Arrived at manhood, he studied

medicine, graduated at Edinburgh, and practised in Scarborough until

nearly his death in 1866. He was thrice Mayor and a Justice of

the Peace for the borough. Dr. Harland was a man of much force

of character, and displayed great originality in the treatment of

disease. Besides exercising skill in his profession, he had a

great love for mechanical pursuits. He spent his leisure time

in inventions of many sorts; and, in conjunction with the late Sir

George Cayley of Brompton, he kept an excellent mechanic constantly

at work.

In 1827 he invented and patented a steam-carriage for running

on common roads. Before the adoption of railways, the old

stage coaches were found slow and insufficient for the traffic.

A working model of the steam-coach was perfected, embracing a

multitubular boiler for quickly raising high-pressure steam, with a

revolving surface condenser for reducing the steam to water again,

by means of its exposure to the cold draught of the atmosphere

through the interstices of extremely thin laminations of copper

plates. The entire machinery, placed under the bottom of the

carriage, was borne on springs; the whole being of an elegant form.

This model steam-carriage ascended with perfect ease the steepest

roads. Its success was so complete that Dr. Harland designed a

full-sized carriage; but the demands upon his professional skill

were so great that he was prevented going further than constructing

the pair of engines, the wheels, and a part of the boiler,—all of

which remnants I still preserve, as valuable links in the progress

of steam locomotion.

Other branches of practical science—such as electricity,

magnetism, and chemical cultivation of the soil—received a share of

his attention. He predicted that three or four powerful

electric lamps would yet light a whole city. He was also

convinced of the feasibility of an electric cable to New York, and

calculated the probable cost. As an example to the

neighbourhood, he successfully cultivated a tract of moorland, and

overcame difficulties which before then were thought insurmountable.

When passing through Newcastle, while still a young man, on

one of his journeys to the University at Edinburgh, and being

desirous of witnessing the operations in a coal-mine, a friend

recommended him to visit Killingworth pit, where he would find one

George Stephenson, a most intelligent workman, in charge. My

father was introduced to Mr. Stephenson accordingly; and after

rambling over the underground workings, and observing the pumping

and winding engines in full operation, a friendship was made, which

afterwards proved of the greatest service to myself, by facilitating

my being placed as a pupil at the great engineering works of Messrs.

Robert Stephenson and Co., at Newcastle.

My mother was the daughter of Gawan Pierson, a landed

proprietor of Goathland, near Rosedale. She, too, was

surprisingly mechanical in her tastes; and assisted my father in

preparing many of his plans, besides attaining considerable

proficiency in drawing, painting, and modelling in wax. Toys

in those days were poor, as well as very expensive to purchase.

But the nursery soon became a little workshop under her directions;

and the boys were usually engaged, one in making a cart, another in

carving out a horse, and a third in cutting out a boat; while the

girls were making harness, or sewing sails, or cutting out and

making perfect dresses for their dolls—whose houses were completely

furnished with everything, from the kitchen to the attic, all made

at home.

It was in a house of such industry and mechanism that I was

brought up. As a youth, I was slow at my lessons; preferring

to watch and assist workmen when I had an opportunity of doing so,

even with the certainty of having a thrashing from the schoolmaster

for my neglect. Thus I got to know every workshop and every

workman in the town. At any rate I picked up a smattering of a

variety of trades, which afterwards proved of the greatest use to

me. The chief of these was wooden shipbuilding, a branch of

industry then extensively carried on by Messrs. William and Robert

Tindall, the former of whom resided in London; he was one of the

half-dozen great shipbuilders and owners who founded "Lloyd's."

Splendid East Indiamen, of some 1,000 tons burden, were then built

at Scarborough; and scarcely a timber was moulded, a plank bent, a

spar lined off, or launching ship-ways laid, without my being

present to witness them. And thus, in course of time, I was

able to make for myself the neatest and fastest of model yachts.

At that time, I attended the Grammar School. Of the

rudiments taught, I was fondest of drawing, geometry, and Euclid.

Indeed, I went twice through the first two books of the latter

before I was twelve years old. At this age I was sent to the

Edinburgh Academy, my eldest brother William being then a medical

student at the University. I remained at Edinburgh two years.

My early progress in mathematics would have been lost in the

classical training which was then insisted upon at the academy, but

for my brother who was not only a good mathematician but an

excellent mechanic. He took care to carry on my instruction in

that branch of knowledge, as well as to teach me to make models of

machines and buildings, in which he was himself proficient. I

remember, in one of my journeys to Edinburgh, by coach from

Darlington, that a gentleman expressed his wonder what a screw

propeller could be like; for the screw, as a method of propulsion,

was then being introduced. I pointed out to him the patent

tail of a windmill by the roadside, and said, "It is just like

that!"

In 1844 my mother died; and shortly after, my brother having

become M.D., and obtained a prize gold medal, we returned to

Scarborough. It was intended that he should assist my father;

but he preferred going abroad for a few years. I may mention

further, with relation to him, that after many years of scientific

research and professional practice, he died at Hong Kong in 1858,

when a public monument was erected to his memory, in what is known

as the "Happy Valley."

I remained for a short time under the tuition of my old

master. But the time was rapidly approaching when I too must

determine what I was "to be" in life. I had no hesitation in

deciding to be an engineer, though my father wished me to be a

barrister. But I kept constant to my resolution; and

eventually he succeeded, through his early acquaintance with George

Stephenson, in gaining for me an entrance to the engineering works

of Robert Stephenson and Co., at Newcastle-upon-Tyne. I

started there as a pupil on my fifteenth birthday, for an

apprenticeship of five years. I was to spend the first four

years in the various workshops, and the last year in the

drawing-office.

I was now in my element. The working hours, it is true,

were very long,—being from six in the morning until 8.15 at night;

excepting on Saturday, when we knocked off at four. However,

all this gave me so much the more experiences; and, taking advantage

of it, I found that, when I had reached the age of eighteen, I was

intrusted with the full charge of erecting one side of a locomotive.

I had to accomplish the same amount of work as my mate on the other

side, one Murray Playfair, a powerful, hard-working Scotchman.

My strength and endurance were sometimes taxed to the utmost, and

required the intervals of my labour to be spent in merely eating and

sleeping.

I afterwards went through the machine-shops. I was

fortunate enough to get charge of the best screw-cutting and

brass-turning lathe in the shop; the former occupant, Jack

Singleton, having just been promoted to a foreman's berth at the

Messrs. Armstrong's factory. He afterwards became

superintendent of all the hydraulic machinery of the Mersey Dock

Trust at Liverpool. After my four years had been completed, I

went into the drawing-office, to which I had looked forward with

pleasure; and, having before practised lineal as well as free-hand

drawing, I soon succeeded in getting good and difficult designs to

work out, and eventually finished drawings of the engines.

Indeed, on visiting the works many years after, one of these

drawings was shown to me as a "specimen;" the person exhibiting it

not knowing that it was my own work.

In the course of my occasional visits to Scarborough, my

attention was drawn to the imperfect design of the lifeboats of the

period; the frequent shipwrecks along the coast indicating the

necessity for their improvement. After considerable

deliberation, I matured a plan for a metal lifeboat, of a

cylindrico-conical or chrysalis form, to be propelled by a screw at

each end, turned by sixteen men inside, seated on water-ballast

tanks; sufficient room being left at the ends inside for the

accommodation of ten or twelve shipwrecked persons; while a mate

near the bow, and the captain near the stern in charge of the

rudder, were stationed in recesses in the deck about three feet

deep. The whole apparatus was almost cylindrical, and

watertight, save in the self-acting ventilators, which could only

give access to the smallest portion of water. I considered

that, if the lifeboat fully manned were launched into the roughest

seas, or off the deck of a vessel, it would, even if turned on its

back, immediately right itself, without any of the crew being

disturbed from their positions, to which they were to have been

strapped.

It happened that at this time (the summer of 1850) his Grace

the late Duke of Northumberland, who had always taken a deep

interest in the Lifeboat Institution, offered a prize of one hundred

guineas for the best model and design of such a craft; so I

determined to complete my plans and make a working model of my

lifeboat. I came to the conclusion that the cylindrico-conical

form, with the frames to be carried completely round and forming

beams as well, and the two screws, one at each end, worked off the

same power, by which one or other of them would always be immersed,

were worth registering in the Patent Office. I therefore

entered a caveat there; and continued working at my model in the

evenings. I first made a wooden block model, on the scale of

an inch to the foot. I had some difficulty in procuring sheets

of copper thin enough, so that the model should draw only the

correct amount of water; but at last I succeeded, through finding

the man at Newcastle who had supplied my father with copper plates

for his early road locomotive.

The model was only 52 inches in length, and 8 inches in beam;

and in order to fix all the internal fittings, of tanks, seats,

crank handles, and pulleys, I had first to fit the shell plating,

and then, by finally securing one strake of plates on, and then

another, after all inside was complete, I at last finished for good

the last outside plate. In executing the job, my early

experience of all sorts of handiwork came serviceably to my aid.

After many a whole night's work—for the evenings alone were not

sufficient for the purpose—I at length completed my model; and

triumphantly and confidently took it to sea in an open boat; and

then cast it into the waves. The model either rode over them

or passed through them; if it was sometimes rolled over, it righted

itself at once, and resumed its proper attitude in the waters.

After a considerable trial I found scarcely a trace of water inside.

Such as had got there was merely through the joints in the sliding

hatches; though the ventilators were free to work during the

experiments.

I completed the prescribed drawings and specifications, and

sent them, together with the model, to Somerset House. Some

280 schemes of lifeboats were submitted for competition; but mine

was not successful. I suspect that the extreme novelty of the

arrangement deterred the adjudicators from awarding in its favour.

Indeed, the scheme was so unprecedented, and so entirely out of the

ordinary course of things, that there was no special mention made of

it in the report afterwards published, and even the description

there given was incorrect. The prize was awarded to Mr. James

Beaching, of Great Yarmouth, whose plans were afterwards generally

adopted by the Lifeboat Society. I have preserved my model

just as it was; and some of its features have since been introduced

with advantage into shipbuilding. [p.295]

The firm of Robert Stephenson and Co. having contracted to

build for the Government three large iron caissons for the Keyham

Docks, and as these were very similar in construction to that of an

ordinary iron ship, draughtsmen conversant with that class of work

were specially engaged to superintend it. The manager, knowing

my fondness for ships, placed me as his assistant at this new work.

After I had mastered it, I endeavoured to introduce improvements,

having observed certain defects in laying down the lines—I mean by

the use of graduated curves cut out of thin wood. In lieu of

this method, I contrived thin tapered laths of lancewood, and

weights of a particular form, with steel claws and knife edges

attached, so as to hold the lath tightly down to the paper, yet

capable of being readily adjusted, so as to produce any form of

curve, along which the pen could freely and continuously travel.

This method proved very efficient, and it has since come into

general use.

The Messrs. Stephenson were then also making marine engines,

as well as large condensing pumping engines, and a large tubular

bridge to be erected over the river Don. The splendid

high-level bridge over the Tyne, of which Robert Stephenson was the

engineer, was also in course of construction. With the

opportunity of seeing these great works in progress, and of

visiting, during my holidays and long evenings, most of the

manufactories and mines in the neighbourhood of Newcastle, I could

not fail to pick up considerable knowledge, and an acquaintance with

a vast variety of trades. There were about thirty other pupils

in the works at the same time with myself; some were there either

through favour or idle fancy; but comparatively few gave their full

attention to the work, and I have since heard nothing of them.

Indeed, unless a young fellow takes a real interest in his work, and

has a genuine love for it, the greatest advantages will prove of no

avail whatever.

It was a good plan adopted at the works, to require the

pupils to keep the same hours as the rest of the men, and, though

they paid a premium on entering, to give them the same rate of wages

as the rest of the lads. Mr. William Hutchinson, a

contemporary of George Stephenson, was the managing partner.

He was a person of great experience, and had the most thorough

knowledge of men and materials, knowing well how to handle both to

the best advantage. His son-in-law, Mr. William Weallans, was

the head draughtsman, and very proficient, not only in quickness but

in accuracy and finish. I found it of great advantage to have

the benefit of the example and the training of these very clever

men.

My five years apprenticeship was completed in May 1851, on my

twentieth birthday. Having had but very little "black time,"

as it was called, beyond the half-yearly holiday for visiting my

friends, and having only "slept in" twice during the five years, I

was at once entered on the books as a journeyman, on the "big" wage

of twenty shillings a week. Orders were, however, at that time

very difficult to be had. Railway trucks, and even navvies'

barrows, were contracted for in order to keep the men employed.

It was better not to discharge them, and to find something for them

to do. At the same time it was not very encouraging for me,

under such circumstances, to remain with the firm. I therefore

soon arranged to leave; and first of all I went to see London.

It was the Great Exhibition year of 1851. I need scarcely say

what a rich feast I found there, and how thoroughly I enjoyed it

all. I spent about two months in inspecting the works of art

and mechanics in the Exhibition, to my own great advantage. I

then returned home; and, after remaining in Scarborough for a short

time, I proceeded to Glasgow with a letter of introduction to

Messrs. J. and G. Thomson, marine engine builders, who started me on

the same wages which I had received at Stephenson's, namely twenty

shillings a-week.

I found the banks of the Clyde splendid ground for gaining

further mechanical knowledge. There were the ship and engine

works on both sides of the river, down to Govan; and below there, at

Renfrew, Dumbarton, Port Glasgow, and Greenock—no end of magnificent

yards—so that I had plenty of occupation for my leisure time on

Saturday afternoons. The works of Messrs. Robert Napier and

Sons were then at the top of the tree. The largest Cunard

steamers were built and engined there. Tod and Macgregor were

the foremost in screw steamships—those for the Peninsular and

Oriental Company being splendid models of symmetry and works of art.

Some of the fine wooden paddle-steamers built in Bristol for the

Royal Mail Company were sent round to the Clyde for their machinery.

I contrived to board all these ships from time to time, so as to

become well acquainted with their respective merits and

peculiarities.

As an illustration of how contrivances, excellent in

principle, but defective in construction, may be discarded, but

again taken up under more favourable circumstances, I may mention

that I saw a Hall's patent surface-condensor thrown to one side from

one of these steamers, the principal difficulty being in keeping it

tight. And yet, in the course of a very few years, by the

simplest possible contrivance—inserting an indiarubber ring round

each end of the tube (Spencer's patent)—surface condensation in

marine engines came into vogue; and there is probably no ocean-going

steamer afloat without it, furnished with every variety of suitable

packings.

After some time, the Messrs. Thomson determined to build

their own vessels, and an experienced naval draughtsman was engaged,

to whom I was "told off" whenever he needed assistance. In the

course of time, more and more of the ship work came in my way.

Indeed, I seemed to obtain the preference. Fortunately for us

both, my superior obtained an appointment of a similar kind on the

Tyne, at superior pay, and I was promoted to his place. The

Thomsons had now a very fine shipbuilding-yard, in full working

order, with several large steamers on the stocks. I was placed

in the drawing-office as head draughtsman. At the same time I

had no rise of wages; but still went on enjoying my twenty shillings

a week. I was, however, gaining information and experience,

and knew that better pay would follow in due course of time.

And without solicitation I was eventually offered an engagement for

a term of years, at an increased and increasing salary, with three

months' notice on either side.

I had only enjoyed the advance for a short time, when Mr.

Thomas Toward, a shipbuilder on the Tyne, being in want of a

manager, made application to the Messrs. Stephenson for such a

person. They mentioned my name, and Mr. Toward came over to

the Clyde to see me. The result was, that I became engaged,

and it was arranged that I should enter on my enlarged duties on the

Tyne in the autumn of 1853. It was with no small reluctance

that I left the Messrs. Thomson. They were first-class

practical men, and had throughout shown me every kindness and

consideration. But a managership was not to be had every day;

and being the next step to the position of a master, I could not

neglect the opportunity for advancement which now offered itself.

Before leaving Glasgow, however, I found that it would be

necessary to have a new angle and plate furnace provided for the

works on the Tyne. Now, the best man in Glasgow for building

these important requisites for shipbuilding work was scarcely ever

sober; but by watching and coaxing him, and by a liberal supply of

Glenlivat afterwards, I contrived to lay down on paper, from his

directions, what he considered to be the best class of furnace; and

by the aid of this I was afterwards enabled to construct what proved

to be the best furnace on the Tyne.

To return to my education in shipbuilding. My early

efforts in ship-draughting at Stephensons' were further developed

and matured at Thomsons' on the Clyde. Models and drawings

were more carefully worked out on the ¼-in. scale than heretofore.

The stern frames were laid off and put up at once correctly, which

before had been first shaped by full-sized wooden moulds. I

also contrived a mode of quickly and correctly laying off the

frame-lines on a model, by laying it on a plane surface, and then,

with a rectangular block traversing it—a pencil in a suitable holder

being readily applied over the curved surface. This method is

now in general use.

Even at that time, competition as regards speed in the Clyde

steamers was very keen. Foremost among the competitors was the

late Mr. David Hutchinson, who, though delighted with the

Mountaineer, built by the Thomsons in 1853, did not hesitate to

have her lengthened forward to make her sharper, so as to secure her

ascendency in speed during the ensuing season. The results

were satisfactory; and his steamers grew and grew, until they

developed into the celebrated Iona and Cambria, which

were in later years built for him by the same firm. I may

mention that the Cunard screw steamer Jura was the last heavy

job with which I was connected while at Thomsons'.

I then proceeded to the Tyne, to superintend the building of

ships and marine boilers. The shipbuilding yard was at St.

Peter's, about two and a-half miles below Newcastle. I found

the work, as practised there, rough and ready; but by steady

attention to all the details, and by careful inspection when passing

the "piece-work" (a practice much in vogue there, but which I

discouraged), I contrived to raise the standard of excellence,

without a corresponding increase of price. My object was to

raise the quality of the work turned out; and, as we had orders from

the Russian Government, from China, and the Continent, as well as

from shipowners at home, I observed that quality was a very

important element in all commercial success. My master, Mr.

Thomas Toward, was in declining health; and, being desirous of

spending his winters abroad, I was consequently left in full charge

of the works. But as there did not appear to be a satisfactory

prospect, under the circumstances, for any material development of

the business, a trifling circumstance arose, which again changed the

course of my career.

An advertisement appeared in the papers for a manager to

conduct a shipbuilding yard in Belfast. I made inquiries as to

the situation, and eventually applied for it. I was appointed,

and entered upon my duties there at Christmas, 1854. The yard

was a much larger one than that on the Tyne, and was capable of

great expansion. It was situated on what was then well known

as the Queen's Island; but now, like the Isle of Dogs, it has been

attached by reclamation. The yard, about four acres in extent,

was held by lease from the Belfast Harbour Commissioners. It

was well placed, alongside a fine patent slip, with clear frontage,

allowing of the largest ships being freely launched. Indeed,

the first ship built there, the Mary Stenhouse, had only just

been completed and launched by Messrs. Robert Hickson and Co., then

the proprietors of the undertaking. They were also the owners

of the Eliza Street Iron Works, Belfast, which were started to work

up old iron materials. But as the works were found to be

unremunerative, they were shortly afterwards closed.

On my entering the shipbuilding yard I found that the firm

had an order for two large sailing ships. One of these was

partly in frame; and I at once tackled with it and the men.

Mr. Hickson, the acting partner, not being practically acquainted

with the business, the whole proceeding connected with the building

of the ships devolved upon me. I had been engaged to supersede

a manager summarily dismissed. Although he had not given

satisfaction to his employers, he was a great favourite with the

men. Accordingly, my appearance as manager in his stead was

not very agreeable to the employed. On inquiry I found that

the rate of wages paid was above the usual value, whilst the

quantity as well as quality of the work done were below the

standard. I proceeded to rectify these defects, by paying the

ordinary rate of wages, and then by raising the quality of the work

done. I was met by the usual method—a strike. The men

turned out. They were abetted by the former manager; and the

leading hands hung about the town unemployed, in the hope of my

throwing up the post in disgust.

But, nothing daunted, I went repeatedly over to the Clyde for

the purpose of enlisting fresh hands. When I brought them

over, however, in batches, there was the greatest difficulty in

inducing them to work. They were intimidated, or enticed, or

feasted, and sent home again. The late manager had also taken

a yard on the other side of the river, and actually commenced to

build a ship, employing some of his old comrades; but beyond laying

the keel, little more was ever done. A few months after my

arrival, my firm had to arrange with its creditors, whilst I,

pending the settlement, had myself to guarantee the wages to a few

of the leading hands, whom I had only just succeeded in gathering

together. In this dilemma, an old friend, a foreman on the

Clyde, came over to Belfast to see me. After hearing my story,

and considering the difficulties I had to encounter, he advised me

at once to "throw up the job!" My reply was, that "having

mounted a restive horse, I would ride him into the stable."

Notwithstanding the advice of my friend, I held on. The

comparatively few men in the works, as well as those out, no doubt

observed my determination. The obstacles were no doubt great;

the financial difficulties were extreme; and yet there was a

prospect of profit from the work in hand, provided only the men

could be induced to settle steadily down to their ordinary

employment. I gradually gathered together a number of steady

workmen, and appointed suitable foremen. I obtained a

considerable accession of strength from Newcastle. On the

death of Mr. Toward, his head foreman, Mr. William Hanston, with a

number of the leading hands, joined me. From that time forward

the works went on apace; and we finished the ships in hand to the

perfect satisfaction of the owners.

Orders were obtained for several large sailing ships as well

as screw vessels. We lifted and repaired wrecked ships, to the

material advantage of Mr. Hickson, then the sole representative of

the firm. After three years thus engaged, I resolved to start

somewhere as a shipbuilder on my own account. I made inquiries

at Garston, Birkenhead, and other places. When Mr. Hickson

heard of my intentions, he said he had no wish to carry on the

concern after I left, and made a satisfactory proposal for the sale

to me of his holding of the Queen's Island Yard. So I agreed

to the proposed arrangement. The transfer and the purchase

were soon completed, through the kind assistance of my old and

esteemed friend Mr. G. C. Schwabe, of Liverpool; whose nephew, Mr.

G. W. Wolff, had been with me for a few months as my private

assistant.

It was necessary, however, before commencing for myself, that

I should assist Mr. Hickson in finishing off the remaining vessels

in hand, as well as to look out for orders on my own account.

Fortunately, I had not long to wait; for it had so happened that my

introduction to the Messrs. Thomson of Glasgow had been made through

the instrumentality of my good friend Mr. Schwabe, who induced Mr.

James Bibby (of J. Bibby, Sons & Co., Liverpool) to furnish me with

the necessary letter. While in Glasgow, I had endeavoured to

assist the Messrs. Bibby in the purchase of a steamer; so I was now

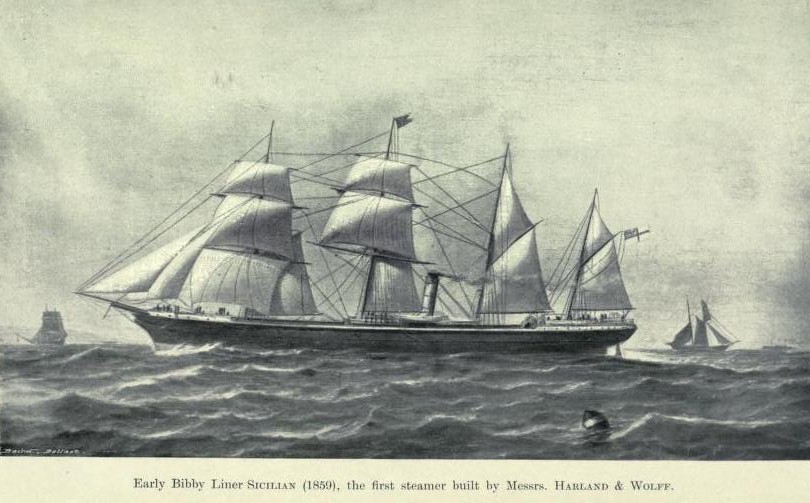

intrusted by them with the building of three screw steamers—the

Venetian, Sicilian, and Syrian, each 270 feet

long, by 34 feet beam, and 22 feet 9 inches hold; and contracted

with Macnab and Co., Greenock, to supply the requisite

steam-engines.

|

The Sicilian, Bibby Line, 1860 [p.304]

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

|

This was considered a large order in those days. It

required many additions to the machinery, plant, and tools of the

yard. I invited Mr. Wolff, then away in the Mediterranean as

engineer of a steamer, to return and take charge of the drawing

office. Mr. Wolff had served his apprenticeship with Messrs.

Joseph Whitworth and Co., of Manchester, and was a most able man,

thoroughly competent for the work. Everything went on

prosperously; and, in the midst of all my engagements, I found time

to woo and win the hand of Miss Rosa Wann, of Wilmont, Belfast, to

whom I was married on the 26th of January, 1860, and by her great

energy, soundness of judgment, and cleverness in organization, I was

soon relieved from all sources of care and anxiety, excepting those

connected with business.

GUSTAV WILHELM

WOLFF (1834-1913)

[p.305]

Picture: Wikipedia

The steamers were completed in the course of the following

year, doubtless to the satisfaction of the owners, for their

delivery was immediately followed by an order for two larger

vessels. As I required frequently to go from home, and as the

works must be carefully attended to during my absence, on the 1st of

January, 1862, I took Mr. Wolff in as a partner; and the firm has

since continued under the name of Harland and Wolff. I may

here add that I have throughout received the most able advice and

assistance from my excellent friend and partner, and that we have

together been enabled to found an entirely new branch of industry in

Belfast.

It is necessary for me here to refer back a little to a screw

steamer which was built on the Clyde for Bibby and Co. by Mr. John

Read, and engined by J. and G. Thomson while I was with them.

That steamer was called the Tiber. She was looked upon

as of an extreme length, being 235 feet, in proportion to her beam,

which was 29 feet. Serious misgivings were thrown out as to

whether she would ever stand a heavy sea. Vessels of such

proportions were thought to be crank, and even dangerous.

Nevertheless, she seemed to my mind a great success. From that

time, I began to think and work out the advantages and disadvantages

of such a vessel, from an owner's as well as from a builder's point

of view. The result was greatly in favour of the owner, though

entailing difficulties in construction as regards the builder.

These difficulties, however, I thought might easily be overcome.

In the first steamers ordered of me by the Messrs. Bibby, I

thought it more prudent to simply build to the dimensions furnished,

although they were even longer than usual. But, prior to the

precise dimensions being fixed for the second order, I with

confidence proposed my theory of the greater carrying power and

accommodation, both for cargo and passengers, that would be gained

by constructing the new vessels of increased length, without any

increase of beam. I conceived that they would show improved

qualities in a sea-way, and that, notwithstanding the increased

accommodation, the same speed with the same power would be obtained,

by only a slight increase in the first cost. The result was,

that I was allowed to settle the dimensions; and the following were

then decided on: Length, 310 feet; beam, 34 feet; depth of hold, 24

feet 9 inches; all of which were fully compensated for by making the

upper deck entirely of iron.

In this way, the hull of the ship was converted into a box

girder of immensely increased strength, and was, I believe, the

first ocean steamer ever so constructed. The rig too was

unique. The four masts were made in one continuous length,

with fore-and-aft sails, but no yards,—thereby reducing the number

of hands necessary to work them. And the steam winches were so

arranged as to be serviceable for all the heavy hauls, as well as

for the rapid handling of the cargo.

In the introduction of so many novelties, I was well

supported by Mr. F. Leyland, the junior partner of Messrs. Bibby's

firm, and by the intelligent and practical experience of Captain

Birch, the overlooker, and Captain George Wakeham, the Commodore of

the company. Unsuccessful attempts had been made many years

before to condense the steam from the engines by passing it into

variously formed chambers, tubes, &c., to be there condensed by

surfaces kept cold by the circulation of sea-water round them, so as

to preserve the pure water and return it to the boilers free of

salt. In this way, "salting up" was avoided, and a

considerable saving of fuel and expenses in repairs was effected.

Mr. Spencer had patented an improvement on Hall's method of surface

condensation, by introducing indiarubber rings at each end of the

tubes. This had been tried as an experiment on shore, and we

advised that it should be adopted in one of Messrs. Bibby's smallest

steamers, the Frankfort. The results were found

perfectly satisfactory. Some 20 per cent. of fuel was saved;

and, after the patent right had been bought, the method was adopted

in all the vessels of the company.

When these new ships were first seen at Liverpool, the "old

salts" held up their hands. They were too long! they were too

sharp! they would break their backs! They might, indeed, get

out of the Mersey, but they would never get back! The ships,

however, sailed; and they made rapid and prosperous voyages to and

from the Mediterranean. They fulfilled all the promises which

had been made. They proved the advantages of our new build of

ships; and the owners were perfectly satisfied with their superior

strength, speed, and accommodation. The Bibbys were wise men

in their day and generation. They did not stop, but went on

ordering more ships. After the Grecian and the

Italian had made two or three voyages to Alexandria, they sent

us an order for three more vessels. By our advice, they were

made twenty feet longer than the previous ones, though of no greater

beam; in other respects, they were almost identical. This was

too much for "Jack." "What!" he exclaimed, "more Bibby's

coffins?" Yes, more and more; and in the course of time, most

shipowners followed our example.

To a young firm, a repetition of orders like these was a

great advantage,—not only because of the novel design of the ships,

but also because of their constructive details. We did our

best to fit up the Egyptian, Dalmatian, and Arabian,

as first-rate vessels. Those engaged in the Mediterranean

trade finding them to be serious rivals, partly because of the great

cargos which they carried, but principally from the regularity with

which they made their voyages with such surprisingly small

consumption of coal. They were not, however, what "Jack" had

been accustomed to consider "dry ships." The ship built

Dutchman fashion, with her bluff ends, is the driest of all ships,

but the least steady, because she rises to every sea. But the

new ships, because of their length and sharpness, precluded this;

for, though they rose sufficiently to an approaching wave for all

purposes of safety, they often went through the crest of it, and,

though shipping a little water, it was not only easier for the

vessel, but the shortest road.

Nature seems to have furnished us with the finest design for

a vessel in the form of the fish: it presents such fine lines—is so

clean, so true, and so rapid in its movements. The ship,

however, must float; and to hit upon the happy medium of velocity

and stability seems to me the art and mystery of shipbuilding.

In order to give large carrying capacity, we gave flatness of bottom

and squareness of bilge. This became known in Liverpool as the

"Belfast bottom;" and it has been generally adopted. This form

not only serves to give stability, but also increases the carrying

power without lessening the speed.

While Sailor Jack and our many commercial rivals stood aghast

and wondered, our friends gave us yet another order for a still

longer ship, with still the same beam and power. The vessel

was named the Persian; she was 360 feet long, 34 feet beam,

24 feet 9 inches hold. More cargo was thus carried, at higher

speed. It was only a further development of the fish form of

structure. Venice was an important port to call at. The

channel was difficult to navigate, and the Venetian class

(270 feet long) was supposed to be the extreme length that could be

handled there. But what with the straight stem,—by cutting the

forefoot away, and by the introduction of powerful steering-gear,

worked amidships,—the captain was able to navigate the Persian,

90 feet longer than the Venetian, with much less anxiety and

inconvenience.

Until the building of the Persian, we had taken great

pride in the modelling and finish of the old style of cutwater and

figurehead, with bowsprit and jib-boom; but in urging the advantages

of greater length of hull, we were met by the fact of its being

simply impossible in certain docks to swing vessels of any greater

length than those already constructed. Not to be beaten, we

proposed to do away with all these overhanging encumbrances, and to

adopt a perpendicular stem. In this way the hull might be made

so much longer; and this was, I believe, the first occasion of its

being adopted in this country in the case of an ocean steamer;

though the once celebrated Collins Line of paddle steamers had, I

believe, such stems. The iron decks, iron bulwarks, and iron

rails, were all found very serviceable in our later vessels, there

being no leaking, no caulking of deck-planks or waterways, nor any

consequent damaging of cargo. Having found it impossible to

combine satisfactorily wood with iron, each being so differently

affected by temperature and moisture, I secured some of these

novelties of construction in a patent, by which filling in the

spaces between frames, &c., with Portland cement, instead of chocks

of wood, and covering the iron plates with cement and tiles, came

into practice, and this has since come into very general use.

The Tiber, already referred to, was 235 feet in length

when first constructed by Read, of Glasgow, and was then thought too

long; but she was now placed in our hands to be lengthened 39 feet,

as well as to have an iron deck added, both of which greatly

improved her. We also lengthened the Messrs. Bibby's Calpe—also

built by Messrs. Thomson while I was there—by no less than 93 feet.

The advantage of lengthening ships, retaining the same beam and

power, having become generally recognised, we were intrusted by the

Cunard Company to lengthen the Hecla, Olympus, Atlas, and

Marathon, each by 63 feet. The Royal Consort P.S., which

had been lengthened first at Liverpool, was again lengthened by us

at Belfast.

The success of all this heavy work, executed for successful

owners, put a sort of backbone into the Belfast shipbuilding yard.

While other concerns were slack, we were either lengthening or

building steamers as well as sailing-ships for firms in Liverpool,

London, and Belfast. Many acres of ground were added to the

works. The Harbour Commissioners had now made a fine new

graving-dock, and connected the Queen's Island with the mainland.

The yard, thus improved and extended, was surveyed by the Admiralty,

and placed on the first-class list. We afterwards built for

the Government the gun vessels Lynx and Algerine, as

well as the store and torpedo ship Hecla, of 3,360 tons.

The Suez Canal being now open, our friends the Messrs. Bibby

gave us an order for three steamers of very large tonnage, capable

of being adapted for trade with the antipodes if necessary. In

these new vessels there was no retrograde step as regards length,

for they were 390 feet keel by 37 feet beam, square-rigged on three

of the masts, with the yards for the first time fitted on

travellers, as to enable them to be readily sent clown; thus forming

a unique combination of big fore-and-aft sails, with handy square

sails. These ships were named the Istrian, Iberian,

and Illyrian, and in 1868 they went to sea; soon after to be

followed by three more ships—the Bavarian, Bohemian, and

Bulgarian—in most respects the same, though ten feet longer,

with the same beam. They were first placed in the

Mediterranean trade, but were afterwards transferred to the

Liverpool and Boston trade, for cattle and emigrants. These,

with three smaller steamers for the Spanish cattle trade, and two

larger steamers for other trades, made together twenty steam-vessels

constructed for the Messrs. James Bibby & Co.'s firm; and it was a

matter of congratulation that, after a great deal of heavy and

constant work, not one of them had exhibited the slightest

indication of weakness,—all continuing in first-rate working order.

[p.312]

The speedy and economic working of the Belfast steamers,

compared with those of the ordinary type, having now become well

known, a scheme was set on foot in 1869 for employing similar

vessels, though of larger size, for passenger and goods

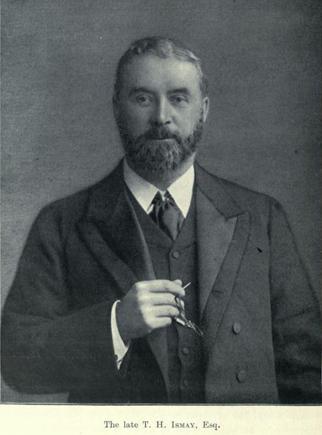

accommodation between England and America. Mr. T. H. Ismay, of

Liverpool, the spirited shipowner, then formed, in conjunction with

the late Mr. G. H. Fletcher, the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company,

Limited; and we were commissioned by them to build six large

Transatlantic steamers, capable of carrying a heavy cargo of goods,

as well as a full complement of cabin and steerage passengers,

between Liverpool and New York, at a speed equal, if not superior,

to that of the Cunard and Inman lines. The vessels were to be

longer than any we had yet constructed, being 400 feet keel and 41

feet beam, with 32 feet hold.

T. H. ISMAY

(1837-99) [p.313]

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

This was a great opportunity, and we eagerly embraced it. The

works were now up to the mark in point of extent and appliances. The

men in our employment were mostly of our own training: the foremen

had been promoted from the ranks; the manager, Mr. W. A. Wilson, and

the head draughtsman, Mr. W. J. Perrie (since become partners),

having, as pupils, worked up through all the departments, and

ultimately won their honourable and responsible positions by dint of

merit only—by character, perseverance, and ability. We were

therefore in a position to take up an important contract of this

kind, and to work it out with heart and soul.

As everything in the way of saving of fuel was of first-rate

importance, we devoted ourselves to that branch of economic working.

It was necessary that buoyancy or space should be left for cargo, at

the same time that increased speed should be secured, with as little

consumption of coal as possible. The Messrs. Elder and Co., of

Glasgow, had made great strides in this direction with the paddle

steam-engines which they had constructed for the Pacific Company on

the compound principle. They had also introduced them on some

of their screw steamers, with more or less success. Others

were trying the same principle in various forms, by the use of

high-pressure cylinders, and so on; the form of the boilers being

varied according to circumstances, for the proper economy of fuel.

The first thing absolutely wanted was, perfectly reliable

information as to the actual state of the compound engine and boiler

up to the date of our inquiry. To ascertain the facts by

experience, we dispatched Mr. Alexander Wilson, younger brother of

the manager—who had been formerly a pupil of Messrs. Macnab and Co.,

of Greenock, and was thoroughly able for the work—to make a number

of voyages in steam vessels fitted with the best examples of

compound engines.

|

|

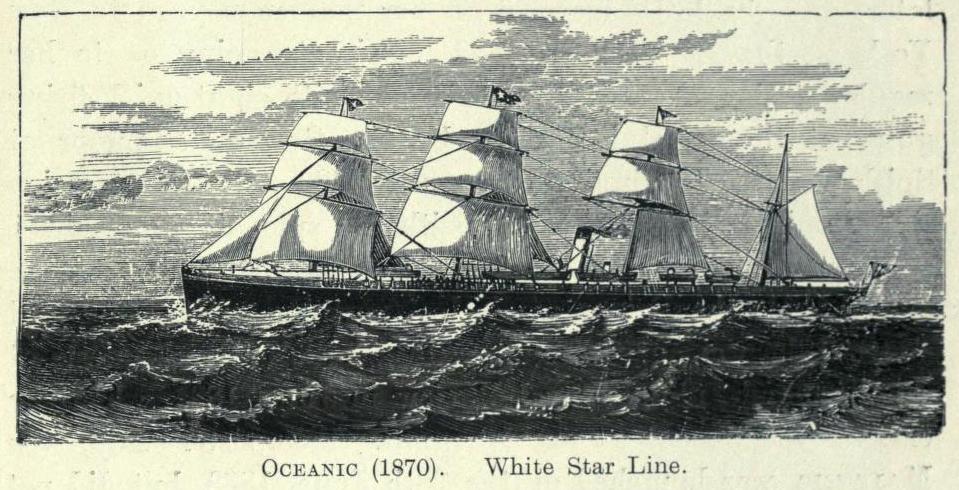

The result of this careful inquiry was the design of the

machinery and boilers of the Oceanic [p.314]

and five sister-ships. They were constructed on the vertical

overhead "tandem" type, with five-feet stroke (at that time thought

excessive), oval single-ended transverse boilers, with a working

pressure of sixty pounds. We contracted with Messrs. Maudslay,

Sons, and Field, of London, for three of these sets, and with

Messrs. George Forrester and Co., of Liverpool, for the other three;

and as we found we could build the six vessels in the same time as

the machinery was being constructed; and, as all this machinery had

to be conveyed to Belfast to be there fitted on board, whilst the

vessels were being otherwise finished, we built a little

screw-steamer, the Camel, of extra strength, with very big

hatchways, to receive these large masses of iron; and this, in

course of time, was found to work with great advantage; until

eventually we constructed our own machinery.

We were most fortunate in the type of engine we had fixed

upon, for it proved both economical and serviceable in all ways;

and, with but slight modifications, we repeated it in the many

subsequent vessels which we built for the White Star Company.

Another feature of novelty in these vessels consisted in placing the

first-class accommodation amidships, with the third-class aft and

forward. In all previous ocean steamers, the cabin passengers

had been berthed near the stern, where the heaving motion of the

vessel was far greater than in the centre, and where that most

disagreeable vibration inseparable from proximity to the propeller

was ever present. The unappetising smells from the galley were

also avoided. And last, but not least, a commodious

smoking-saloon was fitted up amidships, contrasting most favourably

with the scanty accommodation provided in other vessels. The

saloon, too, presented the novelty of extending the full width of

the vessel, and was lighted from each side. Electric bells

were for the first time fitted on board ship. The saloon and

entire range of cabins were lighted by gas, made on board, though

this has since given place to the incandescent electric light.

A fine promenade deck was provided over the saloon, which was

accessible from below in all weathers by the grand staircase.

These, and other arrangements, greatly promoted the comfort

and convenience of the cabin passengers; while those in the steerage

found great improvements in convenience, sanitation, and

accommodation. "Jack" had his forecastle well ventilated and

lighted, and a turtle-back over his head when on deck, with winches

to haul for him, and a steam-engine to work the wheel; while the

engineers and firemen berthed as near their work as possible, never

needing to wet a jacket or miss a meal. In short, for the

first time perhaps, ocean-voyaging, even in the North Atlantic, was

made not only less tedious and dreadful to all, but was rendered

enjoyable and even delightful to many. Before the Oceanic,

the pioneer of the new line, was even launched, rival companies had

already consigned her to the deepest place in the ocean. Her

first appearance in Liverpool was therefore regarded ,with much

interest. Mr. Ismay, during the construction of the vessel,

took every pains to suggest improvements and arrangements with a

view to the comfort and convenience of the travelling public.

He accompanied the vessel on her first voyage to New York in March,

1871, under command of Captain, now Sir Digby Murray, Brt.

Although severe weather was experienced, the ship made a splendid

voyage, with a heavy cargo of goods and passengers. The

Oceanic thus started the Transatlantic traffic of the Company,

with the house-flag of the White Star proudly flying on the main.

It may be mentioned that the speed of the Oceanic was

at least a knot faster than had been heretofore accomplished across

the Atlantic. The motion of the vessel was easy, without any

indication of weakness or straining, even in the heaviest weather.

The only inducement to slow was when going head to it (which often

meant head through it), to avoid the inconvenience of

shipping a heavy body of "green sea" on deck forward. A

turtle-back was therefore provided to throw it off, which proved so

satisfactory, as it had done on the Holyhead and Kingston boats,

that all the subsequent vessels were similarly constructed.

Thus, then, as with the machinery, so was the hull of the Oceanic,

a type of the succeeding vessels, which after intervals of a few

months took up their stations on the Transatlantic line.

|

Oceanic.

Picture: Wikipedia.

|

Having often observed, when at sea in heavy weather, how the

pitching of the vessel caused the weights on the safety-valves to

act irregularly, thus letting puffs of steam escape at every heave,

and as high pressure steam was too valuable a commodity to be so

wasted, we determined to try direct-acting spiral springs, similar

to those used in locomotives in connection with the compound engine.

But as no such experiment was possible in any vessels requiring the

Board of Trade certificate, the alternative of using the Camel

as an experimental vessel was adopted. The spiral springs were

accordingly fitted upon the boiler of that vessel, and with such a

satisfactory result that the Board of Trade allowed the use of the

same contrivance on all the boilers of the Oceanic and every

subsequent steamer, and the contrivance has now come into general

use.

|

[p.317]

Picture: Wikipedia

|

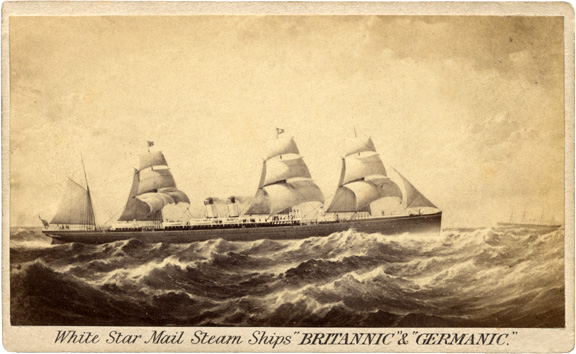

It would be too tedious to mention in detail the other ships

built for the White Star line. The Adriatic and

Baltic were made 37 feet 6 inches longer than the Oceanic,

and a little sharper, being 437 feet 6 inches keel, 41 feet beam,

and 32 feet hold. The success of the Company had been so great

under the able management of Ismay, Imrie and Co., and they had

secured so large a share of the passengers and cargo, as well as of

the mails passing between Liverpool and New York, that it was found

necessary to build two still larger and faster vessels—the

Britannic and Germanic: these were 455 feet in length; 45

feet in beam; and of 5,000 indicated horse-power. The

Britannic was in the first instance constructed with the

propeller fitted to work below the line of keel when in deep water,

by which means the "racing" of the engines was avoided. When

approaching shallow water, the propeller was raised by steam-power

to the ordinary position without any necessity for stopping the

engines during the operation. Although there was an increase

of speed by this means through the uniform revolutions of the

machinery in the heaviest sea, yet there was an objectionable amount

of vibration at certain parts of the vessel, so that we found it

necessary to return to the ordinary fixed propeller, working in the

line of direction of the vessel. Comfort at sea is of even

more importance than speed; and although we had succeeded in four

small steamers working on the new principle, it was found better to

continue in the larger ships to resort to the established modes of

propulsion. It may happen that at some future period the new

method may yet be adopted with complete success.

Meanwhile competition went on with other companies.

Monopoly cannot exist between England and America. Our plans

were followed; and sharper boats and heavier power became the rule

of the day. But increase of horse-power of engines means

increase of heating surface and largely increased boilers, when we

reach the vanishing point of profit, after which there is nothing

left but speed and expense. It may be possible to fill a ship

with boilers, and to save a few hours in the passage from Liverpool

to New York by a tremendous expenditure of coal; but whether that

will answer the purpose of any body of shareholders must be left for

the future to determine. "Brute force" may be still further

employed. It is quite possible that recent "large strides,"

towards a more speedy transit across the Atlantic may have been made

"in the dark."

The last ships we have constructed for Ismay, Imrie and Co.

have been of comparatively moderate dimensions and power—the

Arabic and Coptic, 430 feet long; and the Ionic

and Doric, 440 feet long, all of 2700 indicated horse-power.

These are large cargo steamers, with a moderate amount of saloon

accommodation, and a large space for emigrants. Some of these

are now engaged in crossing the Pacific, whilst others are engaged

in the line from London to New Zealand; the latter being specially

fitted up for carrying frozen meat.

To return to the operations of the Belfast shipbuilding yard.

A serious accident occurred in the autumn of 1867 to the mail

paddle-steamer the Wolf, belonging to the Messrs. Burns, of

Glasgow. When passing out of the Lough, about eight miles from

Belfast, she was run into by another steamer. She was cut down

and sank, and there she lay in about seven fathoms of water; the top

of her funnel and masts being only visible at low tide. She

was in a dangerous position for all vessels navigating the entrance

to the port, and it was necessary that she should be removed, either

by dynamite, gunpowder, or some other process. Divers were

sent down to examine the ship, and the injury done to her being

found to be slight, the owners conferred with us as to the

possibility of lifting her and bringing her into port. Though

such a process had never before been accomplished, yet knowing her

structure well, and finding that we might rely upon smooth water for

about a week or two in summer, we determined to do what we could to

lift the sunken vessel to the surface.

We calculated the probable weight of the vessel, and had a

number of air-tanks expressly built for her floatation. These

were secured to the ship with chains and hooks, the latter being

inserted through the side lights in her sheer strake. Early in

the following summer everything was ready. The air-tanks were

prepared and rafted together. Powerful screws were attached to

each chain, with hand-pumps for emptying the tanks, together with a

steam tender fitted with cooking appliances, berths and stores, for

all hands engaged in the enterprise. We succeeded in attaching

the hooks and chains by means of divers; the chains being ready

coiled on deck. But the weather, which before seemed to be

settled, now gave way. No sooner had we got the pair of big

tanks secured to the after body, than a fierce north-north-easterly

gale set in, and we had to run for it, leaving the tanks partly

filled, in order to lessen the strain on everything.

When the gale had settled, we returned again, and found that

no harm had been done. The remainder of the hooks were

properly attached to the rest of the tanks, the chains were screwed

tightly up, and the tanks were pumped clear. Then the tide

rose; and before high water we had the great satisfaction of getting

the body of the vessel under way, and towing her about a cable's

length from her old bed. At each tide's work she was lifted

higher and higher, and towed into shallower water towards Belfast;

until at length we had her, after eight days, safely in the harbour,

ready to enter the graving dock,—not more ready, however, than we

all were for our beds, for we had neither undressed nor shaved

during that anxious time. Indeed, our friends scarcely

recognised us on our return home.

The result of the enterprise was this. The clean cut

made into the bow of the ship by the collision was soon repaired.

The crop of oysters with which she was incrusted gave place to the

scraper and the paintbrush. The Wolf came out of the

dock to the satisfaction both of the owners and underwriters; and

she was soon "ready for the road," nothing the worse for her ten

months' immersion. [p.320]

Meanwhile the building of new iron ships went on in the

Queen's Island. We were employed by another Liverpool

Company—the British Shipowners' Company, Limited—to supply some

large steamers. The British Empire, of 3,361 gross

tonnage, was the same class of vessel as those of the White Star

line, but fuller, being intended for cargo. Though originally

intended for the Eastern trade, this vessel was eventually placed on

the Liverpool and Philadelphia line; and her working proved so

satisfactory that five more vessels were ordered like her, which

were chartered to the American Company.

The Liverpool agents, Messrs. Richardson, Spence, and Co.,

having purchased the Cunard steamer Russia, sent her over to

us to be lengthened 70 feet, and entirely refitted—another proof of

the rapid change which owners of merchant ships now found it

necessary to adopt in view of the requirements of modern traffic.

Another Liverpool firm, the Messrs. T. and J. Brocklebank, of

world-wide repute for their fine East Indiamen, having given up

building for themselves at their yard at Whitehaven, commissioned us

to build for them the Alexandria and Baroda, which

were shortly followed by the Candahar and Tenasserim.

And continuing to have a faith in the future of big iron sailing

ships, they further employed us to build for them two of yet greater

tonnage, the Belfast and the Majestic.

Indeed, there is a future for sailing ships, notwithstanding

the recent development of steam power. Sailing ships can still

hold their own, especially in the transport of heavy merchandise for

great distances. They can be built more cheaply than steamers;

they can be worked more economically, because they require no

expenditure on coal, nor on wages of engineers; besides the space

occupied by machinery is entirely occupied by merchandise, all of

which pays its quota of freight. Another thing may be

mentioned: the telegraph enables the fact of the sailing of a

vessel, with its cargo on board, to be communicated from Calcutta or

San Francisco to Liverpool, and from that moment the cargo becomes

as marketable as if it were on the spot. There are cases,

indeed, where the freight by sailing ship is even greater than by

steamer, as the charge for warehousing at home is saved, and in the

meantime the cargo while at sea is negotiable.

We have accordingly, during the last few years, built some of

the largest iron and steel sailing ships that have ever gone to sea.

The aim has been to give them great carrying capacity and fair

speed, with economy of working; and the use of steel, both in the

hull and the rigging, facilitates the attainment of these objects.

In 1882 and 1883, we built and launched four of these steel and iron

sailing ships—the Walter H. Wilson, the W. J. Pirrie,

the Fingal, and the Lord Wolseley—each of nearly 3,000

tons register, with four masts,—the owners being Mr. Lawther, of

Belfast; Mr. Martin, of Dublin; and the Irish Shipowners Company.

Besides these and other sailing ships, we have built for

Messrs. Ismay, Imrie and Co. the Garfield, of 2,347

registered tonnage; for Messrs. Thomas Dixon and Son, the Lord

Downshire (2,322); and for Messrs. Bullock's Bay Line, the

Bay of Panama (2,365).

In 1880 we took in another piece of the land reclaimed by the

Belfast Harbour Trust; and there, in close proximity to the

ship-yard, we manufacture all the machinery required for the service

of the steamers constructed by our firm. In this way we are

able to do everything "within ourselves"; and the whole land now

occupied by the works comprises about forty acres, with ten building

slips suitable for the largest vessels.

It remains for me to mention a Belfast firm, which has done

so much for the town. I mean the Messrs. J. P. Corry and Co.,

who have always been amongst our best friends. We built for

them their first iron sailing vessel, the Jane Porter, in

1860, and since then they have never failed us. They

successfully established their "Star" line of sailing clippers from

London to Calcutta, all of which were built here. They

subsequently gave us orders for yet larger vessels, in the Star

of France and the Star of Italy. In all, we have

built for that firm eleven of their well-known "Star" ships.

We have built five ships for the Asiatic Steam Navigation

Company, Limited, each of from 1,650 to 2,059 tons gross; and we are

now building for them two ships, each of about 3,000 tons gross.

In 1883 we launched thirteen iron and steel vessels, of a registered

tonnage of over 30,000 tons. Out of eleven ships now building,

seven are of steel.

Such is a brief and summary account of the means by which we

have been enabled to establish a new branch of industry in Belfast.

It has been accomplished simply by energy and hard work. We

have been well-supported by the skilled labour of our artisans; we

have been backed by the capital and the enterprise of England; and

we believe that if all true patriots would go and do likewise, there

would be nothing to fear for the prosperity and success of Ireland.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XII.

ASTRONOMERS AND STUDENTS IN HUMBLE LIFE:

A NEW CHAPTER IN THE 'PURSUIT

OF KNOWLEDGE UNDER DIFFICULTIES.'

"I first learnt to read when the

masons were at work in your house. I approached them one day,

and observed that the architect used a rule and compass, and that he

made calculations. I inquired what might be the meaning and

use of these things, and I was informed that there was a science

called Arithmetic. I purchased a book of arithmetic, and I

learned it. I was told there was another science called

Geometry; I bought the necessary books, and I learned Geometry.

By reading, I found there were good books in these two sciences in

Latin; I bought a dictionary, and I learned Latin. I

understood, also, that there were good books of the same kind in

French; I bought a dictionary, and I learned French. It seems

to me that one does not need to know anything more than the

twenty-four letters to learn everything else that one wishes."—Edmund

Stone to the Duke of Argyll. ('Pursuit of Knowledge under

Difficulties.')

"The British Census proper reckons twenty-seven and a half

million in the home countries. What makes this census

important is the quality of the units that compose it. They

are free forcible men, in a country where life is safe, and has

reached the greatest value. They give the bias to the current

age; and that not by chance or by mass, but by their character, and

by the number of individuals among them of personal ability."—EMERSON:

English Traits.

FROM Belfast to

the Highlands of Scotland is an easy route by steamers and railways. While at Birnam, near Dunkeld, I was reminded of some remarkable

characters in the neighbourhood. After the publication of the

'Scotch Naturalist' and 'Robert Dick,' I received numerous letters

informing me of many self-taught botanists and students of nature,

quite as interesting as the subjects of my memoirs. Among others,

there was Edward Duncan, the botanist weaver of Aberdeen, whose

interesting life has since been done justice to by Mr. Jolly; and

John Sim of Perth, first a shepherd boy, then a soldier, and towards

the close of his life a poet and a botanist, whose life, I was told,

was "as interesting as a romance."

There was also Alexander Croall, Custodian of the Smith Institute at

Stirling, an admirable naturalist and botanist. He was originally a

hard-working parish schoolmaster, near Montrose. During his holiday

wanderings he collected plants for his extensive herbarium. His

accomplishments having come under the notice of the late Sir William

Hooker, he was selected by that gentleman to prepare sets of the

Plants of Braemar for the Queen and Prince Albert, which he did to

their entire satisfaction. He gave up his school-mastership for an

ill-paid but more congenial occupation, that of Librarian to the

Derby Museum and Herbarium. Some years ago, he was appointed to his

present position of Custodian to the Smith Institute—perhaps the

best provincial museum and art gallery in Scotland.

I could not, however, enter into the history of these remarkable

persons; though I understand there is a probability of Mr. Croall

giving his scientific recollections to the world. He has already

brought out a beautiful work, in four volumes, 'British Seaweeds,

Nature-printed;' and anything connected with his biography will be

looked forward to with interest [p.325]. Among the other persons brought to

my notice, years ago, were Astronomers in humble life. For instance,

I received a letter from John Grierson, keeper of the Girdleness

Lighthouse, near Aberdeen, mentioning one of these persons as "an

extraordinary character." "William Ballingall," he said, "is a

weaver in the town of Lower Largo, Fifeshire; and from his early

days he has made astronomy the subject of passionate study. I used

to spend my school vacation at Largo, and have frequently heard him

expound upon his favourite subject. I believe that very high

opinions have been expressed by scientific gentlemen regarding Ballingall's attainments. They were no doubt surprised that an

individual with but a very limited amount of education, and whose

hours of labour were from five in the morning until ten or eleven at

night, should be able to acquire so much knowledge on so profound a

subject. Had he possessed a fair amount of education, and an

assortment of scientific instruments and books, the world would have

heard more about him. Should you ever find yourself," my

correspondent concludes, "in his neighbourhood, and have a few

hours to spare, you would have no reason to regret the time spent in

his company." I could not, however, arrange to pay the proposed

visit to Largo; but I found that I could, without inconvenience,

visit another astronomer in the neighbourhood of Dunkeld.

In January 1879 I received a letter from Sheriff Barclay, of Perth,

to the following effect:

"Knowing the deep interest you take in

genius and merit in humble ranks, I beg to state to you an

extraordinary case. John Robertson is a railway porter at Coupar

Angus station. From early youth he has made the heavens his study. Night after night he looks above, and from his small earnings he has

provided himself with a telescope which cost him about £30. He sends

notices of his observations to the scientific journals, under the

modest initials of 'J. R.' He is a great favourite with the public;

and it is said that he has made some observations in celestial

phenomena not before noticed. It does occur to me that he should

have a wider field for his favourite study. In connection with an

observatory, his services would be invaluable."

Nearly five years had elapsed since the receipt of this letter, and

I had done nothing to put myself in communication with the Coupar

Angus astronomer. Strange to say, his existence was again recalled

to my notice by Professor Grainger Stewart, of Edinburgh. He said

that if I was in the neighbourhood I ought to call upon him, and

that he would receive me kindly. His duty, he said, was to act as

porter at the station, and to shout the name of the place as the

trains passed. I wrote to John Robertson accordingly, and received a

reply stating that he would be glad to see me, and inclosing a

photograph, in which I recognised a good, honest, sensible face,

with his person inclosed in the usual station porter's garb, "C.R.

1446."

I started from Dunkeld, and reached Coupar Angus in due time. As I

approached the station, I heard the porter calling out, "Coupar

Angus! change here for Blairgowrie!" [p.327] It was the voice of John Robertson. I descended from the train, and

addressed him at once; after the photograph there could be no

mistaking him. An arrangement for a meeting was made, and he called

upon me in the evening. I invited him to such hospitality as the inn

afforded; but he would have nothing. "I am much obliged to you," he

said; "but it always does me harm." I knew at once what the "it"

meant. Then he invited me to his house in Causewayend Street. I

found his cottage clean and comfortable, presided over by an

evidently clever wife. He took me into his sitting-room, where I

inspected his drawings of the sun-spots, made in colour on a large

scale. In all his statements he was perfectly modest and

unpretending. The following is his story, so far as I can recollect,

in his own words:—

"Yes; I certainly take a great interest in astronomy, but I have

done nothing in it worthy of notice. I am scarcely worthy to be

called a day labourer in the science. I am very well known

hereabouts, especially to the travelling public; but I must say that

they think a great deal more of me than I deserve.

"What made me first devote my attention to the subject of astronomy?

Well, if I can trace it to one thing more than another, it was to

some evening lectures delivered by the late Dr. Dick, of Broughty

Ferry, to the men employed at the Craigs' Bleachfield Works, near

Montrose, where I then worked, about the year 1848. Dr. Dick was an

excellent lecturer, and I listened to him with attention. His

instructions were fully impressed upon our minds by Mr. Cooper, the

teacher of the evening school, which I attended. After giving the

young lads employed at the works their lessons in arithmetic, he

would come out with us into the night—and it was generally late when

we separated—and show us the principal constellations, and the

planets above the horizon. It was a wonderful sight; yet we were

told that these hundreds upon hundreds of stars, as far as the eye

could see, were but a mere vestige of the creation amidst which we

lived. I got to know the names of some of the constellations—the

Greater Bear, with 'the pointers' which pointed to the Pole Star,

Orion with his belt, the Twins, the Pleiades, and other prominent

objects in the heavens. It was a source of constant wonder and

surprise.

"When I left the Bleachfield Works, I went to Inverury, to the North

of Scotland Railway, which was then in course of formation; and for

many years, being immersed in work, I thought comparatively little

of astronomy. It remained, however, a pleasant memory. It was only

after coming to this neighbourhood in 1854, when the railway to Blairgowrie was under construction, that I began to read up a

little, during my leisure hours, on the subject of astronomy. I got

married the year after, since which time I have lived in this house.

"I became a member of a reading-room club, and read all the works of

Dr. Dick that the library contained: his 'Treatise on the Solar

System,' his 'Practical Astronomer,' and other works. There were

also some very good popular works to which I was indebted for

amusement as well as instruction: Chambers's 'Information for the

People,' Cassell's 'Popular Educator,' and a very interesting series

of articles in the 'Leisure Hour,' by Edwin Dunkin of the Royal

Observatory, Greenwich. These last papers were accompanied by maps

of the chief constellations, so that I had a renewed opportunity of

becoming a little better acquainted with the geography of the

heavens.

"I began to have a wish for a telescope, by means of which I might

be able to see a little more than with my naked eyes. But I found

that I could not get anything of much use, short of £20. I could not

for a long time feel justified in spending so much money for my own

personal enjoyment. My children were then young and dependent upon

me. They required to attend school—for education is a thing that

parents must not neglect, with a view to the future. However, about

the year 1875, my attention was called to a cheap instrument

advertised by Solomon—what he called his '£5 telescope.' I

purchased one, and it tantalised me; for the power of the instrument

was such as to teach me nothing of the surface of the planets. After