|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VI.

FRIEDRICH GOTTLOB KOENIG

(1774-1833),

GERMAN INVENTOR.

Picture: Wikipedia

_________________________

FREDERICK KOENIG:

INVENTOR OF THE STEAM-PRINTING

MACHINE.

"The honest projector is he who, having by fair and

plain principles of sense, honesty, and ingenuity, brought any

contrivance to a suitable perfection, makes out what he pretends to,

picks nobody's pocket, puts his project in execution, and contents

himself with the real produce as the profit of his invention."—DE

FOE.

I PUBLISHED an

article in 'Macmillan's Magazine' for December, 1869, under the

above title. The materials were principally obtained from William

and Frederick Koenig, sons of the inventor. Since then an elaborate

life has been published at Stuttgart, under the title of 'Friederich

Koenig and die Erfindung Der Schnellpresse, Ein Biographisches

Denkmal. Von Theodor Goebel.' The author, in sending me a copy of

the volume, refers to the article published in 'Macmillan,' and

says, "I hope you will please to accept it as a small acknowledgment

of the thanks, which every German, and especially the sons of

Koenig, in whose name I send the book as well as in mine, owe to you

for having bravely taken up the cause of the much wronged inventor,

their father—an action all the more praiseworthy, as you had to

write against the prejudices and the interests of your own

countrymen."

I believe it is now generally admitted that Koenig was entitled to

the merit of being the first person practically to apply the power

of steam to indefinitely multiplying the productions of the

printing-press; and that no one now attempts to deny him this

honour. It is true others, who followed him, greatly improved upon

his first idea; but this was the case with Watt, Symington,

Crompton, Maudslay, and many more. The true inventor is not merely

the man who registers an idea and takes a patent for it, or who

compiles an invention by borrowing the idea of another, improving

upon or adding to his arrangements, but the man who constructs a

machine such as has never before been made, which executes

satisfactorily all the functions it was intended to perform. And

this is what Koenig's invention did, as will be observed from the

following brief summary of his life and labours.

Frederick Koenig was born on the 17th of April, 1774, at Eisleben,

in Saxony, the birthplace also of a still more famous person, Martin

Luther. His father was a respectable peasant proprietor, described

by Herr Goebel as Anspänner. But this word has now gone out

of use. In feudal times it described the farmer who was obliged to

keep draught cattle to perform service due to the landlord. The boy

received a solid education at the Gymnasium, or public school of

the town. At a proper age he was bound apprentice for five years to Breitkopf and Härtel, of Leipzig, as compositor and printer; but

after serving for four and a quarter years, he was released from his

engagement because of his exceptional skill, which was an unusual

occurrence.

During the later years of his apprenticeship, Koenig was permitted

to attend the classes in the University, more especially those of

Ernst Platner, "physician, philosopher, and anthropologist." After

that he proceeded to the printing-office of his uncle, Anton F. Röse, at Greifswald, an old seaport town on the Baltic, where he

remained a few years. He next went to Halle as a journeyman

printer,—German workmen going about from place to place, during

their wanderschaft, for the purpose of learning their

business. After that, he returned to Brietkopf and Härtel, at

Leipzig, where he had first learnt his trade. During this time,

having saved a little money, he enrolled himself for a year as a

regular student at the University of Leipzig.

According to Koenig's own account, he first began to devise ways and

means for improving the art of printing in the year 1802, when he

was twenty-eight years old. Printing large sheets of paper by hand

was a very slow as well as a very laborious process. One of the

things that most occupied the young printer's mind was how to get

rid of this "horse-work," for such it was, in the business of

printing. He was not, however, over-burdened with means, though

he

devised a machine with this object. But to make a little money, he

made translations for the publishers. In 1803 Koenig returned to his

native town of Eisleben, where he entered into an arrangement with

Frederick Riedel, who furnished the necessary capital for carrying

on the business of a printer and bookseller. Koenig alleges that his

reason for adopting this step was to raise sufficient money to

enable him to carry out his plans for the improvement of printing.

The business, however, did not succeed, as we find him in the

following year carrying on a printing trade at Mayence. Having sold

this business, he removed to Suhl in Thuringia. Here he was occupied

with a stereotyping process, suggested by what he had read about the

art as perfected in England by Earl Stanhope. He also contrived an

improved press, provided with a moveable carriage, on which the

types were placed, with inking rollers, and a new mechanical method

of taking off the impression by flat pressure.

Koenig brought his new machine under the notice of the leading

printers in Germany, but they would not undertake to use it. The

plan seemed to them too complicated and costly. He tried to enlist

men of capital in his scheme, but they all turned a deaf ear to him. He went from town to town, but could obtain no encouragement

whatever. Besides, industrial enterprise in Germany was then in a

measure paralysed by the impending war with France, and men of

capital were naturally averse to risk their money on what seemed a

merely speculative undertaking.

Finding no sympathisers or helpers at home, Koenig next turned his

attention abroad. England was then, as now, the refuge of inventors

who could not find the means of bringing out their schemes

elsewhere; and to England he wistfully turned his eyes. In the

meantime, however, his inventive ability having become known, an

offer was made to him by the Russian Government to proceed to St.

Petersburg and organise the State printing-office there. The

invitation was accepted, and Koenig proceeded to St. Petersburg in

the spring of 1806. But the official difficulties thrown in his way

were very great, and so disgusted him, that he decided to throw up

his appointment, and try his fortune in England. He accordingly took

ship for London, and arrived there in the following November, poor

in means, but rich in his great idea, then his only property.

As Koenig himself said, when giving an account of his

invention:—"There is on the Continent no sort of encouragement for

an enterprise of this description. The system of patents, as it

exists in England, being either unknown, or not adopted in the

Continental States, there is no inducement for industrial

enterprise; and projectors are commonly obliged to offer their

discoveries to some Government, and to solicit their encouragement. I need hardly add that scarcely ever is an invention brought to

maturity under such circumstances. The well-known fact, that almost

every invention seeks, as it were, refuge in England, and is there

brought to perfection, though the Government does not afford any

other protection to inventors beyond what is derived from the wisdom

of the laws, seems to indicate that the Continent has yet to learn

from her the best manner of encouraging the mechanical arts. I had

my full share in the ordinary disappointments of Continental

projectors; and after having lost in Germany and Russia upwards of

two years in fruitless applications, I at last resorted to England."

[p.160]

After arriving in London, Koenig maintained himself with difficulty

by working at his trade, for his comparative ignorance of the

English language stood in his way. But to work manually at the

printer's "case," was not Koenig's object in coming to England. His

idea of a printing machine was always uppermost in his mind, and he

lost no opportunity of bringing the subject under the notice of

master printers likely to take it up. He worked for a time in the

printing office of Richard Taylor, Shoe Lane, Fleet Street, and

mentioned the matter to him. Taylor would not undertake the

invention himself, but he furnished Koenig with an introduction to

Thomas Bensley, the well-known printer of Bolt Court, Fleet Street. On the 11th of March, 1807, Bensley invited Koenig to meet him on

the subject of their recent conversation about "the discovery;" and

on the 31st of the same month, the following agreement was entered

into between Koenig and Bensley:—

"Mr. Koenig, having discovered an entire new Method

of Printing by Machinery, agrees to communicate the same to Mr.

Bensley under the following conditions:—that, if Mr. Bensley shall

be satisfied the Invention will answer all the purposes Mr. Koenig

has stated in the Particulars he has delivered to Mr. Bensley,

signed with his name, he shall enter into a legal Engagement to

purchase the Secret from Mr. Koenig, or enter into such other

agreement as may be deemed mutually beneficial to both parties; or,

should Mr. Bensley wish to decline having any concern with the said

Invention, then he engages not to make any use of the Machinery, or

to communicate the Secret to any person whatsoever, until it is

proved that the Invention is made use of by any one without

restriction of Patent, or other particular agreement on the part of

Mr. Koenig, under the penalty of Six Thousand Pounds.

"(Signed) T. BENSLEY,

"FRIEDERICH KÖNIG.

Witness— J. HUNNEMAN."

Koenig now proceeded to put his idea in execution. He prepared his

plans of the new printing machine. It seems, however, that the

progress made by him was very slow. Indeed, three years passed

before a working model could be got ready, to show his idea in

actual practice. In the meantime, Mr. Walter of The Times had

been seen by Bensley, and consulted on the subject of the invention. On the 9th of August, 1809, more than two years after the date of

the above agreement, Hensley writes to Koenig: "I made a point of

calling upon Mr. Walter yesterday, who, I am sorry to say, declines

our proposition altogether, having (as he says) so many engagements

as to prevent him entering into more."

It may be mentioned that Koenig's original plan was confined to an

improved press, in which the operation of laying the ink on the

types was to be performed by an apparatus connected with the motions

of the coffin, in such a manner as that one hand could be saved. As

little could be gained in expedition by this plan, the idea soon

suggested itself of moving the press by machinery, or to reduce the

several operations to one rotary motion, to which the first mover

might be applied. Whilst Koenig was in the throes of his invention,

he was joined by his friend Andrew F. Bauer, a native of Stuttgart,

who possessed considerable mechanical power, in which the inventor

himself was probably somewhat deficient. At all events, these two

together proceeded to work out the idea, and to construct the first

actual working printing machine.

A patent was taken out, dated the 29th of March, 1810, which

describes the details of the invention. The arrangement was somewhat

similar to that known as the platen machine; the printing being

produced by two flat plates, as in the common hand-press. It also

embodied an ingenious arrangement for inking the type. Instead of

the old-fashioned inking balls, which were beaten on the type by

hand labour, several cylinders covered with felt and leather were

used, and formed part of the machine itself. Two of the cylinders

revolved in opposite directions, so as to spread the ink, which was

then transferred by two other inking cylinders alternately applied

to the "forme" by the action of spiral springs. The movement of

all the parts ,of the machine were to be derived from a

steam-engine, or other first mover.

"After many obstructions and delays," says Koenig himself, in

describing the history of his invention, "the first printing

machine was completed exactly upon the plan which I have described

in the specification of my first patent. It was set to Work in

April, 1811. The sheet (H) of the new Annual Register for 1810,

'Principal Occurrences,' 3,000 copies, was printed with it; and is,

I have no doubt, the first part of a book ever printed with a

machine. The actual use of it, however, soon suggested new ideas,

and led to the rendering it less complicated and more powerful." [p.163] Of course! No great invention was ever completed at one effort. It

would have been strange if Koenig had been satisfied with his first

attempt. It was only a beginning, and he naturally proceeded with

the improvement of his machine. It took Watt more than twenty years

to elaborate his condensing steam-engine; and since his day, owing

to the perfection of self-acting tools, it has been greatly

improved. The power of the Steamboat and the Locomotive also, as

well as of all other inventions, have been developed by the

constantly succeeding improvements of a nation of mechanical

engineers.

Koenig's experiment was only a beginning, and he naturally proceeded

with the improvement of his machine. Although the platen machine of

Koenig's has since been taken up anew, and perfected, it was not

considered by him sufficiently simple in its arrangements as to be

adapted for common use; and he had scarcely completed it, when he

was already revolving in his mind a plan of a second machine on a

new principle, with the object of ensuring greater speed, economy,

and simplicity.

By this time, other well-known London printers, Messrs. Taylor and

Woodfall, had joined Koenig and Beesley in their partnership for the

manufacture and sale of printing machines. The idea which now

occurred to Koenig was, to employ a cylinder instead of a flat

platen machine, for taking the impressions off the type, and to

place the sheet round the cylinder, thereby making it, as it were,

part of the periphery. As early as the year 1790, one William

Nicholson had taken out a patent for a machine for printing "on

paper, linen, cotton, woollen, and other articles," by means of

"blocks, forms, types, plates, and originals," which were to be

"firmly imposed upon a cylindrical surface in the same manner as

common letter is imposed upon a flat stone." [p.164] From the mention of "colouring cylinder," and paper-hangings,

floor-cloths, cottons, linens, woollens, leather, skin, and every

other flexible material," mentioned in the specification, it would

appear as if Nicholson's invention were adapted for calico-printing

and paper-hangings, as well as for the printing of books. But it was

never used for any of these purposes. It contained merely the

register of an idea, and that was all. It was left for Adam

Parkinson, of Manchester, to invent and make practical use of the

cylinder printing machine for calico in the year 1805, and this was

still further advanced by the invention of James Thompson, of

Clitheroe, in 1813; while it was left for Frederick Koenig to invent

and carry into practical operation the cylinder printing press for

newspapers.

After some promising experiments, the plans for a new machine on the

cylindrical principle were proceeded with. Koenig admitted

throughout the great benefit he derived from the assistance of his

friend Bauer. "By the judgment and precision," he said, "with which

he executed my plans, he greatly contributed to my success." A

patent was taken out on October 30th, 1811; and the new machine was

completed in December, 1812. The first sheets ever printed with an

entirely cylindrical press, were sheets G and X of Clarkson's 'Life

of Penn.' The papers of the Protestant Union were also printed with

it in February and March, 1813. Mr. Koenig, in his account of the

invention, says that "sheet M of Acton's 'Hortus Kewensis,' vol.

v., will show the progress of improvement in the use of the

invention. Altogether, there are about 160,000 sheets now in the

hands of the public, printed with this machine, which, with the aid

of two hands, takes off 800 impressions in the hour." [p.165]

Koenig took out a further patent on July 23rd, 1813 and a fourth

(the last) on the 14th of March, 1814. The contrivance of these

various arrangements cost the inventor many anxious days and nights

of study and labour. But he saw before him only the end he wished to

compass, and thought but little of himself and his toils. It may be

mentioned that the principal feature of the invention was the

printing cylinder in the centre of the machine, by which the

impression was taken from the types, instead of by flat plates as in

the first arrangement. The forme was fixed in a cast-iron plate

which was carried to and fro on a table, being received at either

end by strong spiral springs. A double machine, on the same

principle,—the forme alternately passing under and giving an

impression at one of two cylinders at either end of the press,—was

also included in the patent of 1811.

How diligently Koenig continued to elaborate the details of his

invention will be obvious from the two last patents which he took

out, in 1813 and 1814. In the first he introduced an important

improvement in the inking arrangement, and a contrivance for holding

and carrying on the sheet, keeping it close to the printing cylinder

by means of endless tapes; while in the second, he added the

following new expedients: a feeder, consisting of an endless web,—an

improved arrangement of the endless tapes by inner as well as outer friskets,—an improvement of the register (that is, one page falling

exactly on the back of another), by which greater accuracy of

impression was also secured; and finally, an arrangement by which

the sheet was thrown out of the machine, printed by the revolving

cylinder on both sides.

The partners in Koenig's Patents had established a manufactory in

Whitecross Street for the production of the new machines. The

workmen employed were sworn to secrecy. They entered into an

agreement by which they were liable to forfeit £100 if they

communicated to others the secret of the machines, either by

drawings or description, or if they told by whom or for whom they

were constructed. This was to avoid the hostility of the pressmen,

who, having heard of the new invention, were up in arms against it,

as likely to deprive them of their employment. And yet, as stated by

Johnson in his 'Typographia,' the manual labour of the men who

worked at the hand press, was so severe and exhausting, "that the

stoutest constitutions fell a sacrifice to it in a few years." The

number of sheets that could be thrown off was also extremely

limited. With the improved press, perfected by Earl Stanhope, about

250 impressions could be taken, or 125 sheets printed on both sides

in an hour. Although a greater number was produced in newspaper

printing offices by excessive labour, yet it was necessary to have

duplicate presses, and to set up duplicate forms of type, to carry

on such extra work; and still the production of copies was quite

inadequate to satisfy the rapidly increasing demand for newspapers. The time was therefore evidently ripe for the adoption of such a

machine as that of Koenig. Attempts had been made by many inventors,

but every one of them had failed. Printers generally regarded the

steam-press as altogether chimerical.

Such was the condition of affairs when Koenig finished his improved

printing machine in the manufactory in Whitecross Street. The

partners in the invention were now in great hopes. When the machine

had been got ready for work, the proprietors of several of the

leading London newspapers were invited to witness its performances. Amongst them were Mr. Perry of the Morning Chronicle, and Mr.

Walter of The Times. Mr. Perry would have nothing to do with

the machine; he would not even go to see it, for he regarded it as a

gimcrack. [p.167] On the

contrary, Mr. Walter, though he had five years before declined to

enter into any arrangement with Bensley, now that he heard the

machine was finished, and at work, decided to go and inspect it. It

was thoroughly characteristic of the business spirit of the man. He

had been very anxious to apply increased mechanical power to the

printing of his newspaper. He had consulted Isambard Brunel—one of

the cleverest inventors of the day—on the subject; but Brunel, after

studying the subject, and labouring over a variety of plans, finally

gave it up. He had next tried Thomas Martyr, an ingenious young

compositor, who had a scheme for a self-acting machine for working

the printing press. But, although Mr. Walter supplied him with the

necessary funds, his scheme never came to anything. Now, therefore,

was the chance for Koenig!

After carefully examining the machine at work, Mr. Walter was at

once satisfied as to the great value of the invention. He saw it

turning out the impressions with unusual speed and great regularity. This was the very machine of which he had been in search. But it

turned out the impressions printed on one side only. Koenig,

however, having briefly explained the more rapid action of a double

machine on the same principle for the printing of newspapers, Mr.

Walter, after a few minutes' consideration, and before leaving the

premises, ordered two double machines for the printing of The

Times newspaper. Here, at last, was the opportunity for a

triumphant issue out of Koenig's difficulties.

The construction of the first newspaper machine was still, however,

a work of great difficulty and labour. It must be remembered that

nothing of the kind had yet been made by any other inventor. The

single-cylinder machine, which Mr. Walter had seen at work, was

intended for bookwork only. Now Koenig had to construct a

double-cylinder machine for printing newspapers, in which many of

the arrangements must necessarily be entirely new. With the

assistance of his leading mechanic, Bauer, aided by the valuable

suggestions of Mr. Walter himself, Koenig at length completed his

plans, and proceeded with the erection of the working machine. The

several parts were prepared at the workshop in Whitecross Street,

and taken from thence, in as secret a way as possible, to the

premises in Printing House Square adjoining The Times office, where

they were fitted together and erected into a working machine. Nearly

two years elapsed before the press was ready for work. Great as was

the secrecy with which the operations were conducted, the pressmen

of The Times office obtained some inkling of what was going

on, and they vowed vengeance to the foreign inventor who threatened

their craft with destruction. There was, however, always this

consolation: every attempt that had heretofore been made to print

newspapers in any other way than by manual labour had proved an

utter failure!

At length the day arrived when the first newspaper steam-press was

ready for use. The pressmen were in a state of great excitement, for

they knew by rumour that the machine of which they had so long been

apprehensive was fast approaching completion. One night they were

told to wait in the press-room, as important news was expected from

abroad. At six o'clock in the morning of the 29th November, 1814,

Mr. Walter, who had been watching the working of the machine all

through the night, suddenly appeared among the pressmen, and

announced that "The Times is already printed by steam!"

Knowing that the pressmen had vowed vengeance against the inventor

and his invention, and that they had threatened "destruction to him

and his traps," he informed them that if they attempted violence,

there was a force ready to suppress it; but that if they were

peaceable, their wages should be continued to every one of them

until they could obtain similar employment. This proved satisfactory

so far, and he proceeded to distribute several copies of the

newspaper amongst them—the first newspaper printed by steam! That

paper contained the following memorable announcement:—

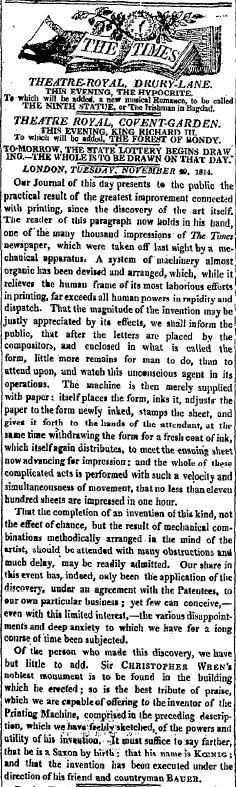

"Our Journal of this day presents to the public the practical result

of the greatest improvement connected with printing since the

discovery of the art itself. The reader of this paragraph now holds

in his hand one of the many thousand impressions of The Times

newspaper which were taken off last night by a mechanical apparatus. A system of machinery almost organic has been devised and arranged,

which, while it relieves the human frame of its most laborious

efforts in printing, far exceeds all human powers in rapidity and

dispatch. That the magnitude of the invention may be justly

appreciated by its effects, we shall inform the public, that after

the letters are placed by the compositors, and enclosed in what is

called the forme, little more remains for man to do than to attend

upon and to watch this unconscious agent in its operations. The

machine is then merely supplied with paper: itself places the forme,

inks it, adjusts the paper to the forme newly inked, stamps the

sheet, and gives it forth to the hands of the attendant, at the same

time withdrawing the forme for a fresh coat of ink, which itself

again distributes, to meet the ensuing sheet now advancing for

impression; and the whole of these complicated acts is performed

with such a velocity and simultaneousness of movement, that no less

than 1,100 sheets are impressed in one hour.

"That the completion of an invention of this kind, not the effect of

chance, but the result of mechanical combinations methodically

arranged in the mind of the artist, should be attended with many

obstructions and much delay, may be readily imagined. Our share in

this event has, indeed, only been the application of the discovery,

under an agreement with the patentees, to our own particular

business; yet few can conceive—even with this limited interest—the

various disappointments and deep anxiety to which we have for a long

course of time been subjected.

"Of the person who made this discovery we have but little to add.

Sir Christopher Wren's noblest monument is to be found in the

building which he erected so is the best tribute of praise which we

are capable of offering to the inventor of the printing machine,

comprised in the preceding description, which we have feebly

sketched, of the powers and utility of his invention. It must

suffice to say further, that he is a Saxon by birth; that his name

is Koenig; and that the invention has been executed under the

direction of his friend and countryman, Bauer."

The machine continued to work steadily and satisfactorily,

notwithstanding the doubters, the unbelievers, and the threateners

of vengeance. The leading article of The Times for December

3rd, 1814, contains the following statement:—

"The machine of which we announced the discovery and our adoption a

few days ago, has been whirling on its course ever since, with

improving order, regularity, and even speed. The length of the

debates on Thursday, the day when Parliament was adjourned, will

have been observed; on such an occasion the operation of composing

and printing the last page must commence among all the journals at

the same moment; and starting from that moment, we, with our

infinitely superior circulation, were enabled to throw off our whole

impression many hours before the other respectable rival prints. The

accuracy and clearness of the impression will likewise excite

attention.

"We shall make no reflections upon those by whom this wonderful

discovery has been opposed,—the doubters and unbelievers,—however

uncharitable they may have been to us; were it not that the efforts

of genius are always impeded by drivellers of this description, and

that we owe it to such men as Mr. Koenig and his Friend, and all

future promulgators of beneficial inventions, to warn them that they

will have to contend with everything that selfishness and conceited

ignorance can devise or say; and if we cannot clear their way before

them, we would at least give them notice to prepare a panoply

against its dirt and filth.

"There is another class of men from whom we receive dark and

anonymous threats of vengeance if we persevere in the use of this

machine. These are the Pressmen. They well know, at least should

well know, that such menace is thrown away upon us. There is nothing

that we will not do to assist and serve those whom we have

discharged. They themselves can see the greater rapidity and

precision with which the paper is printed. What right have they to

make us print it slower and worse for their supposed benefit? A

little reflection, indeed, would show them that it is neither in

their power nor in ours to stop a discovery now made, if it is

beneficial to mankind; or to force it down if it is useless. They

had better, therefore; acquiesce in a result which they cannot

alter; more especially as there will still be employment enough for

the old race of pressmen, before the new method obtains general use,

and no new ones need be brought up to the business; but we caution

them seriously against involving themselves and their families in

ruin, by becoming amenable to the laws of their country. It has

always been matter of great satisfaction to us to reflect, that we

encountered and crushed one conspiracy; and we should be sorry to

find our work half done.

"It is proper to undeceive the world in one particular; that is, as

to the number of men discharged. We in fact employ only eight fewer

workmen than formerly; whereas more than three times that number

have been employed for a year and a half in building the machine."

On the 8th of December following, Mr. Koenig addressed an

advertisement "To the Public" in the columns of The Times,

giving an account of the origin and progress of his invention. We

have already cited several passages from the statement. After

referring to his two last patents, he says:

"The machines now

printing The Times and Mail are upon the same

principle; but they have been contrived for the particular purpose

of a newspaper of extensive circulation, where expedition is the

great object.

"The public are undoubtedly aware, that never, perhaps, was a new

invention put to so severe a trial as the present one, by being used

on its first public introduction for the minting of newspapers, and

will, I trust, be indulgent with respect to the many defects in the

performance, though none of them are inherent in the principle of

the machine; and we hope, that in less than two months, the whole

will be corrected by greater adroitness in the management of it, so

far at least as the hurry of newspaper printing will at all admit.

"It will appear from the foregoing narrative, that it was

incorrectly stated in several newspapers, that I had sold my

interest to two other foreigners; my partners in this enterprise

being at present two Englishmen, Mr. Bensley and Mr. Taylor; and it

is gratifying to my feelings to avail myself of this opportunity to

thank those gentlemen publicly for the confidence which they have

reposed in me, for the aid of their practical skill, and for the

persevering support which they have afforded me in long and very

expensive experiments; thus risking their fortunes in the

prosecution of my invention.

"The first introduction of the invention was considered by some as a

difficult and even hazardous step. The Proprietor of The Times

having made that his task, the public are aware that it is in good

hands."

One would think that Koenig would now feel himself in smooth water,

and receive a share of the good fortune which he had so laboriously

prepared for others. Nothing of the kind! His merits were disputed;

his rights were denied; his patents were infringed; and he never

received any solid advantages for his invention, until he left the

country and took refuge in Germany. It is true, he remained for a

few years longer, in charge of the manufactory in Whitecross Street,

but they were years to him of trouble and sorrow.

In 1816, Koenig designed and superintended the construction of a

single cylinder registering machine for book-printing. This was

supplied to Bensley and Son, and turned out 1,000 sheets, printed on

both sides, in the hour. Blumenbach's 'Physiology' was the first

entire book printed by steam, by this new machine. It was afterwards

employed, in 1818, in working off the Literary Gazette. A

machine of the same kind was supplied to Mr. Richard Taylor for the

purpose of printing the 'Philosophical Magazine,' and books

generally. This was afterwards altered to a double machine, and

employed for printing the Weekly Dispatch.

But what about Koenig's patents? They proved of little use to him. They only proclaimed his methods, and enabled other ingenious

mechanics to borrow his adaptations. Now that he had succeeded in

making machines that would work, the way was clear for everybody

else to follow his footsteps. It had taken him more than six years

to invent and construct a successful steam printing press; but any

clever mechanic, by merely studying his specification, and examining

his machine at work, might arrive at the same results in less than a

week.

The patents did not protect him. New specifications, embodying some

modification or alteration in detail, were lodged by other inventors

and new patents taken out. New printing machines were constructed in

defiance of his supposed legal rights; and he found himself stripped

of the reward that he had been labouring for during so many long and

toilsome years. He could not go to law, and increase his own

vexation and loss. He might get into Chancery easy enough but when

would he get out of it, and in what condition?

It must also be added, that Koenig was unfortunate in his partner

Bensley. While the inventor was taking steps to push the sale of his

book-printing machines among the London printers, Bensley, who was

himself a book-printer, was hindering him in every way in his

negotiations. Koenig was of opinion that Bensley wished to retain

the exclusive advantage which the possession of his registering book

machine gave him over the other printers, by enabling him to print

more quickly and correctly than they could, and thus give him an

advantage over them in his printing contracts.

When Koenig, in despair at his position, consulted counsel as to the

infringement of his patent, he was told that he might institute

proceedings with the best prospect of success; but to this end a

perfect agreement by the partners was essential. When, however,

Koenig asked Bensley to concur with him in taking proceedings in

defence of the patent right, the latter positively refused to do so. Indeed, Koenig was under the impression that his partner had even

entered into an arrangement with the infringers of the patent to

share with them the proceeds of their piracy.

Under these circumstances, it appeared to Koenig that only two

alternatives remained for him to adopt. One was to commence an

expensive, and it might be a protracted, suit in Chancery, in

defence of his patent rights, with possibly his partner, Bensley,

against him; and the other, to abandon his invention in England

without further struggle, and settle abroad. He chose the latter

alternative, and left England finally in August, 1817.

Mr. Richard Taylor, the other partner in the patent, was an

honourable man; but he could not control the proceedings of Bensley. In a memoir published by him in the 'Philosophical Magazine,' "On

the Invention and First Introduction of Mr. Koenig's Printing

Machine," in which he honestly attributes to him the sole merit of

the invention, he says, "Mr. Koenig left England, suddenly, in

disgust at the treacherous conduct of Bensley, always shabby and

overreaching, and whom he found to be laying a scheme for defrauding

his partners in the patents of all the advantages to arise from

them. Bensley, however, while he destroyed the prospects of his

partners, outwitted himself, and grasping at all, lost all, becoming

bankrupt in fortune as well as in character." [p.176]

Koenig was badly used throughout. His merits as an inventor were

denied. On the 3rd of January, 1818, after he had left England, Bensley published a letter in the Literary Gazette, in which

he speaks of the printing machine as his own, without mentioning a

word of Koenig. The 'British Encyclopedia,' in describing the

inventors of the printing machine, omitted the name of Koenig

altogether. The 'Mechanics Magazine,' for September, 1847,

attributed the invention to the Proprietors of The Times,

though Mr. Walter himself had said that his share in the event had

been "only the application of the discovery;" and the late Mr.

Bennet Woodcroft, usually a fair man, in his introductory chapter to

'Patents for Inventions in Printing,' attributes the merit to

William Nicholson's patent (No. 1748), which, he said, "produced an

entire revolution in the mechanism of the art." In other

publications, the claims of Bacon and Donkin were put forward, while

those of Koenig were ignored. The memoir of Mr. Richard Taylor, in

the 'Philosophical Magazine,' was honest and satisfactory; and

should have set the question at rest.

It may further be mentioned that William Nicholson,—who was a patent

agent, and a great taker out of patents, both in his own name and in

the names of others,—was the person employed by Koenig as his agent

to take the requisite steps for registering his invention. When

Koenig consulted him on the subject, Nicholson observed that

"seventeen years before he had taken out a patent for machine

printing, but he had abandoned it, thinking that it wouldn't do; and

had never taken it up again." Indeed, the two machines were on

different principles. Nor did Nicholson himself ever make any claim

to priority of invention, when the success of Koenig's machine was

publicly proclaimed by Mr. Walter of The Times some seven years

later.

When Koenig, now settled abroad, heard of the attempts made in

England to deny his merits as an inventor, he merely observed to his

friend Bauer, "It is really too bad that these people, who have

already robbed me of my invention, should now try to rob me of my

reputation." Had he made any reply to the charges against him, it

might have been comprised in a very few words: "When I arrived in

England, no steam printing machine had ever before been seen; when

I left it, the only printing machines in actual work were those

which I had constructed." But Koenig never took the trouble to defend

the originality of his invention in England, now that he had finally

abandoned the field to others.

There can be no question as to the great improvements introduced in

the printing machine by Mr. Applegath and Mr. Cowper; by Messrs. Hoe

and Sons, of New York; and still later by the present Mr. Walter of

The Times, which have brought the art of machine printing to an

extraordinary degree of perfection and speed. But the original

merits of an invention are not to be determined by a comparison of

the first machine of the kind ever made with the last, after some

sixty years' experience and skill have been applied in bringing it

to perfection. Were the first condensing engine made at Soho—now to

be seen at the Museum in South Kensington—in like manner to be

compared with the last improved pumping-engine made yesterday, even

the great James Watt might be made out to have been a very poor

contriver. It would be much fairer to compare Koenig's

steam-printing machine with the hand-press newspaper printing

machine which it superseded. Though there were steam engines before

Watt, and steamboats before Fulton, and steam locomotives before

Stephenson, there were no steam printing presses before Koenig with

which to compare them. Koenig's was undoubtedly the first, and stood

unequalled and alone.

The rest of Koenig's life, after he retired to Germany, was spent in

industry, if not in peace and quietness. He could not fail to be

cast down by the utter failure of his English partnership, and the

loss of the fruits of his ingenious labours. But instead of brooding

over his troubles, he determined to break away from them, and begin

the world anew. He was only forty-three when he left England, and he

might yet be able to establish himself prosperously in life. He had

his own head and hands to help him. Though England was virtually

closed against him, the whole continent of Europe was open to him,

and presented a wide field for the sale of his printing machines.

While residing in England, Koenig had received many communications

from influential printers in Germany. Johann Spencer and George

Decker wrote to him in 1815, asking for particulars about his

invention; but finding his machine too expensive, [p.179]

the latter commissioned Koenig to send him a Stanhope printing

press—the first ever introduced into Germany—the price of which was

£95. Koenig did this service for his friend, for although he stood

by the superior merits of his own invention, he was sufficiently

liberal to recognise the merits of the inventions of others. Now

that he was about to settle in Germany, he was able to supply his

friends and patrons on the spot.

The question arose, where was he to settle? He made enquiries about

sites along the Rhine, the Neckar, and the Main. At last he was

attracted by a specially interesting spot at Oberzell on the Main,

near Würzburg. It was an old disused convent of the Præmonstratensian monks. The place was conveniently situated for

business, being nearly in the centre of Germany. The Bavarian

Government, desirous of giving encouragement to so useful a genius,

granted Koenig the use of the secularised monastery on easy terms;

and there accordingly he began his operations in the course of the

following year. Bauer soon joined him, with an order from Mr. Walter

for an improved Times machine; and the two men entered into a

partnership which lasted for life.

The partners had at first great difficulties to encounter in getting

their establishment to work. Oberzell was a rural village,

containing only common labourers, from whom they had to select their

workmen. Every person taken into the concern had to be trained and

educated to mechanical work by the partners themselves. With

indescribable patience they taught these labourers the use of the

hammer, the file, the turning-lathe, and other tools, which the

greater number of them had never before seen, and of whose uses they

were entirely ignorant. The machinery of the workshop was got

together with equal difficulty piece by piece, some of the parts

from a great distance,—the mechanical arts being then at a very low

ebb in Germany, which was still suffering from the effects of the

long continental war. At length the workshop was fitted up, the old

barn of the monastery being converted into an iron foundry.

Orders for printing machines were gradually obtained. The first came

from Brockhaus, of Leipzig. By the end of the fourth year two other

single-cylinder machines were completed and sent to Berlin, for use

in the State printing office. By the end of the eighth year seven

double-cylinder steam presses had been manufactured for the largest

newspaper printers in Germany. The recognised excellence of Koenig

and Bauer's book-printing machines—their perfect register, and the

quality of the work they turned out—secured for them an increasing

demand, and by the year 1829 the firm had manufactured fifty-one

machines for the leading book printers throughout Germany. The Oberzell manufactory was now in full work, and gave regular

employment to about 120 men. |

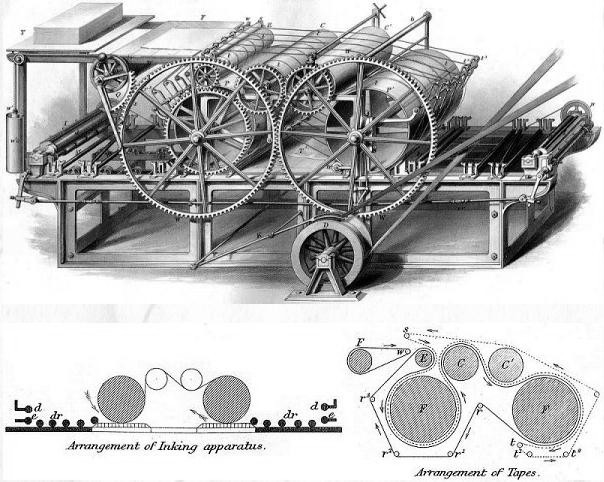

A Koenig-type cylindrical press manufactured by Applegath and Cowper, London,

showing the inking scheme and the movement of paper.

|

A period of considerable depression followed. As was the case in

England, the introduction of the printing machine in Germany excited

considerable hostility among the pressmen. In some of the principal

towns they entered into combinations to destroy them, and several

printing machines were broken by violence and irretrievably injured. But progress could not be stopped; the printing machine had been

fairly born, and must eventually do its work for mankind. These

combinations, however, had an effect for a time. They deterred other

printers from giving orders for the machines; and Koenig and Bauer

were under the necessity of suspending their manufacture to a

considerable extent. To keep their men employed, the partners

proceeded to fit up a paper manufactory, Mr. Cotta, of Stuttgart,

joining them in the adventure; and a mill was fitted up, embodying

all the latest improvements in paper-making.

Koenig, however, did not live to enjoy the fruits of all his study,

labour, toil, and anxiety; for, while this enterprise was still in

progress, and before the machine trade had revived, he was taken

ill, and confined to bed. He became sleepless; his nerves were

unstrung; and no wonder. Brain disease carried him off on the 17th

of January, 1833; and this good, ingenious, and admirable inventor

was removed from all further care and trouble. He died at the early

age of fifty-eight, respected and beloved by all who knew him.

His partner Bauer survived to continue the business for twenty years

longer. It was during this later period that the Oberzell

manufactory enjoyed its greatest prosperity. The prejudices of the

workmen gradually subsided when they found that machine printing,

instead of abridging employment, as they feared it would do,

enormously increased it; and orders accordingly flowed in from

Berlin, Vienna, and all the leading towns and cities of Germany,

Austria, Denmark, Russia, and Sweden. The six hundredth machine,

turned out in 1847, was capable of printing 6,000 impressions in the

hour. In March, 1865, the thousandth machine was completed at Oberzell, on the occasion of the celebration of the fifty years'

jubilee of the invention of the steam press by Koenig.

The sons of Koenig carried on the business; and in the biography by

Goebel, it is stated that the manufactory of Oberzell has now turned

out no fewer than 3,000 printing machines. The greater number have

been supplied to Germany; but 660 were sent to Russia, 61 to Asia,

12 to England, and 11 to America. The rest were despatched to Italy,

Switzerland, Sweden, Spain, Holland, and other countries.

It remains to be said that Koenig and Bauer, united in life, were

not divided by death. Bauer died on February 27, 1860, and the

remains of the partners now lie side by side in the little cemetery

at Oberzell, close to the scene of their labours and the valuable

establishment which they founded.

―――♦―――

CHAPTER VII.

THE WALTERS OF THE TIMES:

INVENTION OF THE WALTER

PRESS.

"Intellect and industry are never

incompatible. There is more wisdom, and will be more benefit, in

combining them than scholars like to believe, or than the common

world imagine. Life has time enough for both, and its happiness will

be increased by the union."—SHARON

TURNER.

|

"I have beheld with most respect the man

Who knew himself, and knew the ways before him,

And from among them chose considerately,

With a clear foresight, not a blindfold courage;

And, having chosen, with a steadfast mind

Pursued his purpose."

HENRY

TAYLOR—Philip

von Artevelde. |

|

|

|

JOHN

WALTER

(1776-1847):

second Editor of The Times.

Picture: Wikipedia |

THE late John

Walter, who adopted Koenig's steam printing press in printing The

Times, was virtually the inventor of the modern newspaper. The

first John Walter, his father, learnt the art of printing in the

office of Dodsley, the proprietor of the 'Annual Register.' He

afterwards pursued the profession of an underwriter, but his

fortunes were literally shipwrecked by the capture of a fleet of

merchantmen by a French Squadron. Compelled by this loss to return

to his trade, he succeeded in obtaining the publication of 'Lloyd's

List,' as well as the printing of the Board of Customs. He also

established himself as a publisher and bookseller at No. 8, Charing

Cross. But his principal achievement was in founding The

Times newspaper.

The Daily Universal Register was started

on the 1st of January, 1785, and was described in the heading as

"printed logographically." The type had still to be composed,

letter by letter, each placed alongside of its predecessor by human

fingers. Mr. Walter's invention consisted in using stereotyped

words and parts of words instead of separate metal letters, by which

a certain saving of time and labour was effected. The name of

the 'Register' did not suit, there being many other publications

bearing a similar title. Accordingly, it was re-named The

Times, and the first number was issued from Printing House

Square on the 1st of January, 1788. |

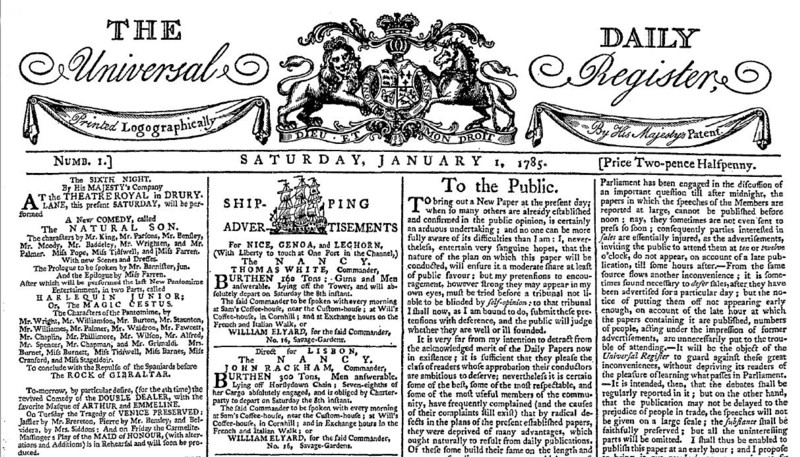

"NUMB. 1." of the Universal Daily

Register, January 1, 1785.

|

The Times was at first a very meagre

publication. It was not much bigger than a number of the old

'Penny Magazine,' containing a single short leader on some current

topic, without any pretensions to excellence; some driblets of news

spread out in large type; half a column of foreign intelligence,

with a column of facetious paragraphs under the heading of "The

Cuckoo;" while the rest of each number consisted of advertisements.

Notwithstanding the comparative innocence of the contents of the

early numbers of the paper, certain passages which appeared in it on

two occasions subjected the publisher to imprisonment in Newgate.

The extent of the offence, on one occasion, consisted in the

publication of a short paragraph intimating that their Royal

Highnesses the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York had "so demeaned

themselves as to incur the just disapprobation of his Majesty!"

For such slight offences were printers sent to gaol in those days.

Although the first Mr. Walter was a man of considerable

business ability, his exertions were probably too much divided

amongst a variety of pursuits to enable him to devote that exclusive

attention to The Times which was necessary to ensure its

success. He possibly regarded it, as other publishers of

newspapers then did, mainly as a means of obtaining a profitable

business in job-printing. Hence, in the elder Walter's hands,

the paper was not only unprofitable in itself, but its maintenance

became a source of gradually increasing expenditure; and the

proprietor seriously contemplated its discontinuance.

At this juncture, John Walter, junior, who had been taken

into the business as a partner, entreated his father to entrust him

with the sole conduct of the paper, and to give it "one more trial."

This was at the beginning of 1803. The new editor and

conductor was then only twenty-seven years of age. He had been

trained to the manual work of a printer "at case," and passed

through nearly every department in the office, literary and

mechanical. But in the first place, he had received a very

liberal education, first at Merchant Taylors' School, and afterwards

at Trinity College, Oxford, where he pursued his classical studies

with much success. He was thus a man of well-cultured mind; he

had been thoroughly disciplined to work; he was, moreover, a man of

tact and energy, full of expedients, and possessed by a passion for

business. His father, urged by the young man's entreaties, at

length consented, although not without misgivings, to resign into

his hands the entire future control of The Times.

Young Walter proceeded forthwith to remodel the

establishment, and to introduce improvements into every department,

as far as the scanty capital at his command would admit.

Before he assumed the direction, The Times did not seek to

guide opinion or to exercise political influence. It was a

scanty newspaper—nothing more. Any political matters referred

to were usually introduced in "Letters to the Editor," in the form

in which Junius's Letters first appeared in the Public Advertiser.

The comments on political affairs by the Editor were meagre and

brief, and confined to a mere statement of supposed facts.

Mr. Walter, very much to the dismay of his father, struck out

an entirely new course. He boldly stated his views on public

affairs, bringing his strong and original judgment to bear upon the

political and social topics of the day. He carefully watched

and closely studied public opinion, and discussed general questions

in all their bearings. He thus invented the modern Leading

Article. The adoption of an independent line of politics

necessarily led him to canvass freely, and occasionally to condemn,

the measures of the Government. Thus, he had only been about a

year in office as editor, when the Sidmouth Administration was

succeeded by that of Mr. Pitt, under whom Lord Melville undertook

the unfortunate Catamaran expedition. His Lordship's

malpractices in the Navy Department had also been brought to light

by the Commissioners of Naval Inquiry. On both these topics

Mr. Walter spoke out freely in terms of reprobation; and the result

was, that the printing for the Customs and the Government

advertisements were at once removed from The Times office.

Two years later Mr. Pitt died, and an Administration

succeeded which contained a portion of the political chiefs whom the

editor had formerly supported on his undertaking the management of

the paper. He was invited by one of them to state the

injustice which had been done to him by the loss of the Customs

printing, and a memorial to the Treasury was submitted for his

signature, with a view to its recovery. But believing that the

reparation of the injury in this manner was likely to be considered

as a favour, entitling those who granted it to a certain degree of

influence over the politics of the journal, Walter refused to sign

it, or to have any concern in presenting the memorial. He did

more; he wrote to those from whom the restoration of the employment

was expected to come, disavowing all connection with the proceeding.

The matter then dropped, and the Customs printing was never restored

to the office.

This course was so unprecedented, and, as his father thought,

was so very wrong-headed, that young Walter had for some time

considerable difficulty in holding his ground and maintaining the

independent position he had assumed. But with great tenacity

of purpose he held on his course undismayed. He was a man who

looked far ahead,—not so much taking into account the results at the

end of each day or of each year, but how the plan he had laid down

for conducting the paper would work out in the long run. And

events proved that the high-minded course he had pursued with so

much firmness of purpose was the wisest course after all.

Another feature in the management which showed

clear-sightedness and business acuteness, was the pains which the

Editor took to ensure greater celerity of information and dispatch

in printing. The expense which he incurred in carrying out

these objects excited the serious displeasure of his father, who

regarded them as acts of juvenile folly and extravagance.

Another circumstance strongly roused the old man's wrath. It

appears that in those days the insertion of theatrical puffs formed

a considerable source of newspaper income; and yet young Walter

determined at once to abolish them. It is not a little

remarkable that these earliest acts of Mr. Walter—which so clearly

marked his enterprise and high-mindedness—should have been made the

subject of painful comments in his father's will.

Notwithstanding this serious opposition from within, the

power and influence of the paper visibly and rapidly grew. The

new Editor concentrated in the columns of his paper a range of

information such as had never before been attempted, or indeed

thought possible. His vigilant eye was directed to every

detail of his business. He greatly improved the reporting of

public meetings, the money market, and other intelligence,—aiming at

greater fulness and accuracy. In the department of criticism

his labours were unwearied. He sought to elevate the character

of the paper, and rendered it more dignified by insisting that it

should be impartial. He thus conferred the greatest public

service upon literature, the drama, and the fine arts, by protecting

them against the evil influences of venal panegyric on the one hand,

and of prejudiced hostility on the other.

But the most remarkable feature of The Times—that

which emphatically commended it to public support and ensured its

commercial success—was its department of foreign intelligence.

At the time that Walter undertook the management of the journal,

Europe was a vast theatre of war; and in the conduct of commercial

affairs—not to speak of political movements—it was of the most vital

importance that early information should be obtained of affairs on

the Continent. The Editor resolved to become himself the

purveyor of foreign intelligence, and at great expense he despatched

his agents in all directions, even in the track of armies; while

others were employed, under various disguises and by means of sundry

pretexts, in many parts of the Continent. These agents

collected information, and despatched it to London, often at

considerable risks, for publication in The Times, where it

usually appeared long in advance of the government despatches.

The late Mr. Pryme, in his 'Autobiographic Recollections,'

mentions a visit which he paid to Mr. Walter at his seat at Bearwood.

"He described to me," says Mr. Pryme, "the cause of the large

extension in the circulation of The Times. He was the

first to establish a foreign correspondent. This was Henry

Crabb Robinson, at a salary of £300 a year. . . . Mr. Walter also

established local reporters, instead of copying from the country

papers. His father doubted the wisdom of such a large

expenditure, but the son prophesied a gradual and certain success,

which has actually been realised."

Mr. Robinson has described in his Diary the manner in which

he became connected with the foreign correspondence. "In

January, 1807," he says, "I received, through my friend J. D.

Collier, a proposal from Mr. Walter that I should take up my

residence at Altona, and become The Times correspondent.

I was to receive from the editor of the 'Hamburger Correspondenten'

all the public documents at his disposal, and was to have the

benefit also of a mass of information, of which the restraints of

the German Press did not permit him to avail himself. The

honorarium I was to receive was ample with my habits of life.

I gladly accepted the offer, and never repented having done so.

My acquaintance with Mr. Walter ripened into friendship, and lasted

as long as he lived." [p.189]

Mr. Robinson was forced to leave Germany by the Battle of

Friedland and the Treaty of Tilsit, which resulted in the naval

coalition against England. Returning to London, he became

foreign editor of The Times until the following year, when he

proceeded to Spain as foreign correspondent. Mr. Walter had

also an agent in the track of the army in the unfortunate Walcheren

expedition; and The Times announced the capitulation of

Flushing forty-eight hours before the news had arrived by any other

channel. By this prompt method of communicating public

intelligence, the practice, which had previously existed, of

systematically retarding the publication of foreign news by

officials at the General Post-office, who made gain by selling them

to the Lombard Street brokers, was effectually extinguished.

This circumstance, as well as the independent course which

Mr. Walter adopted in the discussion of foreign politics, explains

in some measure the opposition which he had to encounter in the

transmission of his despatches. As early as the year 1805,

when he had come into collision with the Government and lost the

Customs printing, The Times despatches were regularly stopped

at the outports, whilst those for the Ministerial journals were

allowed to proceed. This might have crushed a weaker man, but

it did not crush Walter. Of course he expostulated. He

was informed at the Home Secretary's office that he might be

permitted to receive his foreign papers as a favour. But as

this implied the expectation of a favour from him in return, the

proposal was rejected; and, determined not to be baffled, he

employed special couriers, at great cost, for the purpose of

obtaining the earliest transmission of foreign intelligence.

These important qualities—enterprise, energy, business tact,

and public spirit—sufficiently account for his remarkable success.

To these, however, must be added another of no small

importance—discernment and knowledge of character. Though

himself the head and front of his enterprise, it was necessary that

he should secure the services and co-operation of men of first-rate

ability; and in the selection of such men his judgment was almost

unerring. By his discernment and munificence, he collected

round him some of the ablest writers of the age. These were

frequently revealed to him in the communications of

correspondents—the author of the letters signed "Vetus" being thus

selected to write in the leading columns of the paper. But

Walter himself was the soul of The Times. It was he who

gave the tone to its articles, directed its influence, and

superintended its entire conduct with unremitting vigilance.

Even in conducting the mechanical arrangements of the paper—a

business of no small difficulty—he had often occasion to exercise

promptness and boldness of decision in cases of emergency.

Printers in those days were a rather refractory class of workmen,

and not unfrequently took advantage of their position to impose hard

terms on their employers, especially in the daily press, where

everything must be promptly done within a very limited time.

Thus on one occasion, in 1810, the pressmen made a sudden demand

upon the proprietor for an increase of wages, and insisted upon a

uniform rate being paid to all hands, whether good or bad.

Walter was at first disposed to make concessions to the men; but

having been privately informed that a combination was already

entered into by the compositors, as well as by the pressmen, to

leave his employment suddenly, under circumstances that would have

stopped the publication of the paper, and inflicted on him the most

serious injury, he determined to run all risks, rather than submit

to what now appeared to him in the light of an extortion.

The strike took place on a Saturday morning, when suddenly,

and without notice, all the hands turned out. Mr. Walter had

only a few hours' notice of it, but he had already resolved upon his

course. He collected apprentices from half a dozen different

quarters, and a few inferior workmen, who were glad to obtain

employment on any terms. He himself stript to his

shirt-sleeves, and went to work with the rest; and for the next

six-and-thirty hours he was incessantly employed at case and at

press. On the Monday morning, the conspirators, who had

assembled to triumph over his ruin, to their inexpressible amazement

saw The Times issue from the publishing office at the usual

hour, affording a memorable example of what one man's resolute

energy may accomplish in a moment of difficulty.

The journal continued to appear with regularity, though the

printers employed at the office lived in a state of daily peril.

The conspirators, finding themselves baffled, resolved upon trying

another game. They contrived to have two of the men employed

by Walter as compositors apprehended as deserters from the Royal

Navy. The men were taken before the magistrate; but the charge

was only sustained by the testimony of clumsy, perjured witnesses,

and fell to the ground. The turn-outs next proceeded to

assault the new hands, when Mr. Walter resolved to throw around them

the protection of the law. By the advice of counsel, he had

twenty-one of the conspirators apprehended and tried, and nineteen

of them were found guilty and condemned to various periods of

imprisonment. From that moment combination was at an end in

Printing House Square.

Mr. Walter's greatest achievement was his successful

application of steam power to newspaper printing. Although he

had greatly improved the mechanical arrangements after he took

command of the paper, the rate at which the copies could be printed

off remained almost stationary. It took a very long time

indeed to throw off, by the hand-labour of pressmen, the three or

four thousand copies which then constituted the ordinary circulation

of The Times. On the occasion of any event of great

public interest being reported in the paper, it was found almost

impossible to meet the demand for copies. Only about 300

copies could be printed in the hour, with one man to ink the types

and another to work the press, while the labour was very severe.

Thus it took a long time to get out the daily impression, and very

often the evening papers were out before The Times had half

supplied the demand.

Mr. Walter could not brook the tedium of this irksome and

laborious process. To increase the number of impressions, he

resorted to various expedients. The type was set up in

duplicate, and even in triplicate; several Stanhope presses were

kept constantly at work; and still the insatiable demands of the

newsmen on certain occasions could not be met. Thus the

question was early forced upon his consideration, whether he could

not devise machinery for the purpose of expediting the production of

newspapers. Instead of 300 impressions an hour, he wanted from

1,500 to 2,000. Although such a speed as this seemed quite as

chimerical as propelling a ship through the water against wind and

tide at fifteen miles an hour, or running a locomotive on a railway

at fifty, yet Mr. Walter was impressed with the conviction that a

much more rapid printing of newspapers was feasible than by the slow

hand-labour process; and he endeavoured to induce several ingenious

mechanical contrivers to take up and work out his idea.

The principle of producing impressions by means of a

cylinder, and of inking the types by means of a roller, was not new.

We have seen, in the preceding memoir, that as early as 1790 William

Nicholson had patented such a method, but his scheme had never been

brought into practical operation. Mr. Walter endeavoured to

enlist Marc Isambard Brunel—one of the cleverest inventors of the

day—in his proposed method of rapid printing by machinery; but after

labouring over a variety of plans for a considerable time, Brunel

finally gave up the printing machine, unable to make anything of it.

Mr. Walter next tried Thomas Martyr, an ingenious young compositor,

who had a scheme for a self-acting machinery for working the

printing press. He was supplied with the necessary funds to

enable him to prosecute his idea; but Mr. Walter's father was

opposed to the scheme, and when the funds became exhausted, this

scheme also fell to the ground.

|

|

|

The Times,

29 November, 1814 |

As years passed on, and the circulation of the paper increased, the

necessity for some more expeditious method of printing became still

more urgent. Although Mr. Walter had declined to enter into an

arrangement with Bensley in 1809, before Koenig had completed his

invention of printing by cylinders, it was different five years

later, when Koenig's printing machine was actually at work. In

the preceding memoir, the circumstances connected with the adoption

of the invention by Mr. Walter are fully related; as well as the

announcement made in The Times on the 29th of November,

1814—the day on which the first newspaper printed by steam was given

to the world.

But Koenig's printing machine was but the beginning of a

great new branch of industry. After he had left this country

in disgust, it remained for others to perfect the invention;

although the ingenious German was entitled to the greatest credit

for having made the first satisfactory beginning. Great

inventions are not brought forth at a heat. They are begun by

one man, improved by another, and perfected by a whole host of

mechanical inventors. Numerous patents were taken out for the

mechanical improvement of printing. Donkin and Bacon contrived

a machine in 1813, in which the types were placed on a revolving

prism. One of them was made for the University of Cambridge,

but it was found too complicated; the inking was defective; and the

project was abandoned.

In 1816, Mr. Cowper obtained a patent (No. 3974) entitled, "A

Method of Printing Paper for Paper Hangings, and Other Purposes."

The principal feature of this invention consisted in the curving or

bending of stereotype plates for the purpose of being printed in

that form. A number of machines for printing in two colours,

in exact register, was made for the Bank of England, and four

millions of One Pound notes were printed before the Bank Directors

determined to abolish their further issue. The regular mode of

producing stereotype plates, from plaster of Paris moulds, took so

much time, that they could not then be used for newspaper printing.

Two years later, in 1818, Mr. Cowper invented and patented

(No. 4194) his great improvements in printing. It may be

mentioned that he was then himself a printer, in partnership with

Mr. Applegath, his brother-in-law. His invention consisted in

the perfect distribution of the ink, by giving end motion to the

rollers, so as to get a distribution cross ways, as well as

lengthways. This principle is at the very foundation of good

printing, and has been adopted in every machine since made.

The very first experiment proved that the principle was right.

Mr. Cowper was asked by Mr. Walter to alter Koenig's machine at

The Times office, so as to obtain good distribution. He

adopted two of Nicholson's single cylinders and flat formes of type.

Two "drums" were placed betwixt the cylinders to ensure accuracy in

the register,—over and under which the sheet was conveyed in its

progress from one cylinder to the other,—the sheet being at all

times firmly held between two tapes, which bound it to the cylinders

and drums. This is commonly called, in the trade, a

"perfecting machine;" that is, it printed the paper on both sides

simultaneously, and is still much used for "book-work," whilst

single cylinder machines are often used for provincial newspapers.

After this, Mr. Cowper designed the four cylinder machine for

The Times,—by means of which from 4,000 to 5,000 sheets could

be printed from one forme in the hour. In 1823, Mr. Applegath

invented an improvement in the inking apparatus, by placing the

distributing rollers at an angle across the distributing table,

instead of forcing them endways by other means.

Mr. Walter continued to devote the same unremitting attention

to his business as before. He looked into all the details, was

familiar with every department, and, on an emergency, was willing to

lend a hand in any work requiring more than ordinary despatch.

Thus, it is related of him that, in the spring of 1833, shortly

after his return to Parliament as Member for Berkshire, he was at

The Times office one day, when an express arrived from Paris,

bringing the speech of the King of the French on the opening of the

Chambers. The express arrived at 10 A.M., after the day's

impression of the paper had been published, and the editors and

compositors had left the office. It was important that the

speech should be published at once; and Mr. Walter immediately set

to work upon it. He first translated the document; then,

assisted by one compositor, he took his place at the type-case, and

set it up. To the amazement of one of the staff, who dropped

in about noon, he "found Mr. Walter, M.P. for Berks, working in his

shirt-sleeves!" The speech was set and printed, and the second

edition was in the City by one o'clock. Had he not "turned to"

as he did, the whole expense of the express service would have been

lost. And it is probable that there was not another man in the

whole establishment who could have performed the double

work—intellectual and physical—which he that day executed with his

own bead and bands.

Such an incident curiously illustrates his eminent success in

life. It was simply the result of persevering diligence, which

shrank from no effort and neglected no detail; as well as of

prudence allied to boldness, but certainly not "of chance; " and,

above all, of high-minded integrity and unimpeachable honesty.

It is perhaps unnecessary to add more as to the merits of Mr. Walter

as a man of enterprise in business, or as a public man and a Member

of Parliament. The great work of his life was the development

of his journal, the history of which forms the best monument to his

merits and his powers.

The progressive improvement of steam printing machinery was

not affected by Mr. Walter's death, which occurred in 1847. He

had given it an impulse which it never lost. In 1846 Mr.

Applegath patented certain important improvements in the steam

press. The general disposition of his new machine was that of

a vertical cylinder 200 inches in circumference, holding on it the