|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIII.

MORE DIFFICULTIES AND MORE INVENTIONS—BOULTON AGAIN IN CORNWALL.

THE battle of the

firm had hitherto been all up-hill. Nearly twenty years had

passed since Watt had made his invention. His life since then

had been a constant struggle; it was a struggle still.

Thirteen years had passed since the original patent had been taken

out, and seven since the Act had been passed for its extension.

But the engine had as yet yielded no profit, and the outlay of

capital continued. Notwithstanding Boulton's energy and

resources, the partners were often in the greatest straits for

money, and sometimes, as Saturday nights came round, they had to

beat about among their friends for the means of paying the workmen's

wages.

Though Watt continued to imagine himself on the brink of

ruin, things were not really so gloomy as he supposed. We find

Boulton stating in a confidential letter to Matthews, that the dues

payable on the pumping-engines actually erected in 1782 amounted to

£4,320 a year; and that when all the engines in progress had been

finished, they would probably amount to about £9,000. It is

true, the dues were paid with difficulty by the mining interest, but

Boulton looked forward with confidence to better days coming round.

Indeed, he already saw his way through the difficulties of the firm,

and encouraged his doleful partner to hope that in the course of a

very few years more, they would be rid of their burdens.

As Cornwall was, however, now becoming well supplied with

pumping-engines, it became necessary to open up new branches of

business to keep the Soho manufactory at work. With this

object, Boulton became more and more desirous of applying the engine

to the various purposes of rotary motion. In one of his visits

to Wales, in 1781, he had seen a powerful copper-rolling mill driven

by water. When told that its defect was, that it was liable to

be stopped in summer during the drought, he immediately asked—"Why

not use our engine? It goes night and day, summer and winter,

and is altogether unaffected by drought." Immediately on his

return home, he made a model of a steam-rolling mill, with two

cylinders and two beams, connecting the power by a horizontal axis;

and by the end of the year he had a steam forge erected at Soho on

this plan. "It answers very well," he wrote to Matthews, "and

astonishes all the ironmasters; for, although it is a small engine,

it draws even more steel per day than a large rolling-mill in this

neighbourhood draws by water."

Mr. Wilkinson was so much pleased with this rolling-mill,

that he ordered one to be made on a large scale for the Bradley

ironworks; and another was shortly after ordered for Rotherham.

But the number of iron mills was exceedingly limited, and Boulton

did not anticipate any large extension of business in that quarter.

If, however, he could once get the rotary engine introduced as a

motive power for corn and flour mills, he believed that the demand

would be considerable. Writing to Watt on the subject, he

said, "When Wheal Virgin is at work, and all the Cornish business is

in good train, we must look out for orders, as all our treaties are

seemingly at an end, having none now on the Lapis. There is no

other Cornwall to be found, and the most likely line for increasing

the consumption of our engines is the application of them to mills,

which is certainly an extensive field."

Watt on his return to Birmingham proceeded to embody his plan

for securing rotary motion in a working engine, so that he might be

enabled to exhibit the thing in actual work. He was stimulated

to action by the report which reached his ears that a person in

Birmingham had set agoing a self-moving steam rotator, in imitation

of his, on which he exclaimed, "Surely the Devil of Rotations is

afoot! I hope he will whirl them into Bedlam or Newgate."

Boulton, who had by this time gone to Cornwall for the winter, wrote

to him from Cosgarne, "It is certainly expensive; but nevertheless I

think, as we have so much at stake, that we should proceed to

execute such rotatives as you have specified . . . . You should get

a good workman or two to execute your ideas with despatch, lest they

perish. The value of their wages for a year might be £100, but

it would be the means of our keeping the start that we now have of

all others. But above all, there is nothing of more importance

than the perfect completion of the double expansive reciprocating

engine as soon as may be." Watt replied that he was busily

occupied in getting the rotative motion applied to one of the Soho

engines. "These rotatives," said he, "have taken up all my

time and attention for months, so that I can scarcely say that I

have done anything which can be called business. Our accounts

lie miserably confused. We are going on in a very considerable

weekly expense at Soho, and I can see nothing likely to be produced

from it which will be an equivalent." Speaking of the prospect

of further improvements, he added, "It is very possible that,

excepting what can be done in improving the mechanics of the engine,

nothing much better than we have already done will be allowed by

Nature, who has fixed a ne plus ultra in most things."

While thus hopelessly proceeding with the rotative engine,

Watt was disquieted by the intelligence which reached him from

Boulton, as to the untoward state of affairs in Cornwall. At

some of the most important mines, in which Boulton and Watt held

shares, the yield had considerably fallen off, and as the price of

the ores was still very low, they had in a great measure ceased to

be remunerative. Hence appeals were made to Boulton on all

sides for an abatement of the engine dues. Unwilling to

concede this, the adventurers proceeded to threaten him with the

Hornblowers, whose engine they declared their intention of adopting.

[p.291]

Boulton resisted them at every point; the battle being, as he

said, "Boulton and Watt against all Cornwall." He kept Watt

fully informed from day to day of all that passed, and longed for

more rapid means of communication,—the postal service being then so

defective that no less than thirteen days elapsed before Boulton, at

Truro, could receive an answer from Watt at Birmingham. On one

occasion we find Watt's letter eleven days on the road between the

two places. The partners even had fears that their letters

were tampered with in transit; and, in order to carry on their

correspondence confidentially, Watt proposed to employ a shorthand

alphabet, which he had learnt from Dr. Priestley, in which to write

at least the names of persons "as our correspondence," he observed,

"ought to be managed with all possible secrecy, especially as to

names."

Boulton, as usual, led a very active life in Cornwall.

Much of his time was occupied in riding from mine to mine,

inspecting the engines at work, and superintending the erection of

others. The season being far advanced, the weather was bad,

and the roads miry; but, wet or dry, he went his rounds. In

one of his letters he gives an account of a miserable journey home

on horseback, on a certain rainy, windy, dark night in November,

when he was "caught in water up to 12 hands." "It was very

disagreeable," he adds, "that one cannot stay out till dark upon the

most emergent business without risking one's life." But once

at home he was happy. "The greatest comfort I find here," he

says, "is in being shut out from the world, and the world from me.

At the same time I have quite as much visiting as I wish for."

One of his favourite amusements was collecting and arranging

fossils,—some for his friend Wedgwood, and others for his own "fossilry"

at Soho.

Boulton was well supported out of doors by William Murdock,

now regarded as "the right hand" of the concern in Cornwall.

"Murdock hath been indefatigable," he wrote to Watt, "ever since

they began [at Wheal Virgin new Engine]. He has scarcely been

in bed or taken necessary food. . . . After slaving day and night on

Thursday and Friday, a letter came from Wheal Virgin that he must go

instantly to set their engine to work or they would let out the

fire. He went and set the engine to work; it worked well for

the five or six hours he remained. He left it and returned to

the Consolidated Mines about eleven at night, and was employed about

the engines till four this morning, and then went to bed. I

found him at ten this morning in Poldice Cistern, seeking for pins

and casters that had jumped out, when I insisted on his going home

to bed."

On one occasion, when an engine superintended by Murdock

stopped through some accident, the water rose in the mine, and the

miners were drowned out. Upon this occurring, they came

"roaring at him" for having thrown them out of work, and threatened

to tear him to pieces. Nothing daunted, he went through the

midst of the men, and proceeded to the invalided engine, which he

succeeded in very shortly repairing and setting to work again.

The miners were so rejoiced that they were carried by their feelings

into the opposite extreme; and when he came out of the engine-house

they cheered him vociferously, and insisted upon carrying him home

on their shoulders in triumph!

About this time, Boulton became increasingly anxious to

ascertain what the Hornblowers were doing. They continued to

brag of the extraordinary powers of the engine erected by them at

Radstoke, near Bristol, whither he proposed to go, to ascertain its

construction and qualities, as well as to warn the persons who were

employing them as to the consequences of their infringing the

existing patent. But he was tied to Cornwall by urgent

business, and could not leave his post for a day. "During the

forking of these two great mines," said he, "I dare not stir two

miles from the spot, and it will yet be six weeks before I regain my

liberty." He determined, therefore, to send over James Law, a

Soho man on whom he could rely, to ascertain, if possible, the

character of the new engine, and he also asked his partner Watt to

wait upon the proprietors of Radstoke so soon as he could make it

convenient to do so. Law accordingly proceeded to Radstoke,

and soon found out where the engine was; but as the Horners were all

in the neighbourhood, keeping watch and ward over it, turn and turn

about, he was unable to see it, except through the engine-house

window, when it was not working. He learnt, however, that

there was something seriously wrong with it, and that the engineers

were considerably crestfallen about its performances.

Watt proceeded to Bristol, as recommended by his partner, for

the purpose of having a personal interview with the Hornblowers'

employers. On his arrival, he found that Major Tucker, the

principal partner, was absent; and though he succeeded in seeing Mr.

Hill, another of the partners, he could get no satisfactory reply

from him as to the intentions of the firm with respect to the new

engine. Having travelled a hundred miles on his special

errand, Watt determined not to return to Birmingham until he had

seen the principal partner. On inquiry he found that Major

Tucker had gone to Bath, and thither Watt followed him. At

Bath he found that the Major had gone to Melcompton. Watt took

a chaise and followed him. The Major was out hunting; and Watt

waited impatiently at a little alehouse in the village till three

o'clock, when the Major returned—"a potato-faced, chuckle-headed

fellow, with a scar on the pupil of one eye. In short," said

Watt, "I did not like his physiog." After shortly informing

the Major of the object of his visit, who promised to bring the

subject under the notice of his partners at a meeting to be held in

about three weeks' time, Watt, finding that he could do no more,

took his leave; but before he left Bristol, he inserted in the local

papers an advertisement, prepared by Boulton, cautioning the public

against using the Hornblowers' engine, as being a direct

infringement of their patent.

Watt then returned to Birmingham, to proceed with the

completion of his rotary motion. Boulton kept urging that the

field for pumping-engines was limited, that their Cornish prospects

were still gloomy, and that they must very soon look out for new

fields. One of his schemes was the applying of the

steam-engine to the winding of coals. "A hundred engines at

£100 a year each," he said, "would be a better thing than all

Cornwall." But the best field of all, he still held, was

mills. "Let us remember," said he, "the Birmingham motto, to

'strike while the iron is hot.'"

Watt, as usual, was not so sanguine as his partner, and

rather doubtful of the profit to be derived from this source.

From a correspondence between him and Mr. William Wyatt, of London,

on the subject, we find him discouraging the scheme of applying

steam-engines to drive corn-mills; on which Boulton wrote to

Wyatt,—"You have had a correspondence with my friend Watt, but I

know not the particulars. . . . You must make allowance for what Mr.

Watt says ... he undervalues the merits of his own works. . .

. I will take all risks in erecting an engine for a corn-mill. . . .

I think I can safely say our engine will grind four times the

quantity of corn per bushel of coal compared with any engine

hitherto erected." [p.296]

In the meantime Watt, notwithstanding his doubts, had been

proceeding with the completion of his rotative machine, and by the

end of the year applied it with success to a tilt-hammer, as well as

to a corn-mill at Soho. Several difficulties presented

themselves at first, but they were speedily surmounted. The

number of strokes made by the hammer was increased from 18 per

minute in the first experiment, to 25 in the second; and Watt

contemplated increasing the speed to even 250 or 300 strokes a

minute, by diminishing the height to which the hammer rose before

making its descending blow. "There is now no doubt," said he,

"that fire-engines will drive mills; but I entertain some doubts

whether anything is to be got by them, as by any computation I have

yet made of the mill for Reynolds [recently ordered] I cannot make

it come to more than £20 per annum, which will do little more than

pay trouble. Perhaps some others may do better."

The problem of producing rotary motion by steam-power was

thus solved to the satisfaction even of Watt himself. But

though a boundless field for the employment of the engine now

presented itself, Watt was anything but elated at the prospect.

For some time he doubted whether it would be worth the while of the

Soho firm to accept orders for engines of this sort. When

Boulton went to Dublin to endeavour to secure a patent for Ireland,

Watt wrote to him thus:—"Some people at Burton are making

application to us for an engine to work a cotton-mill; but from

their letter and the man they have sent here, I have no great

opinion of their abilities. . . . If you come home by way of

Manchester, please not to seek for orders for cotton-mill engines,

because I hear that there are so many mills erecting on powerful

streams in the north of England, that the trade must soon be

overdone, and consequently our labour may be lost." Boulton,

however, had no such misgivings. He foresaw that before long

the superior power, regularity, speed, and economy of the

steam-engine, must recommend it for adoption in all branches of

manufacture in which rotative motion was employed; and he had no

hesitation in applying for orders notwithstanding the opposition of

his partner.

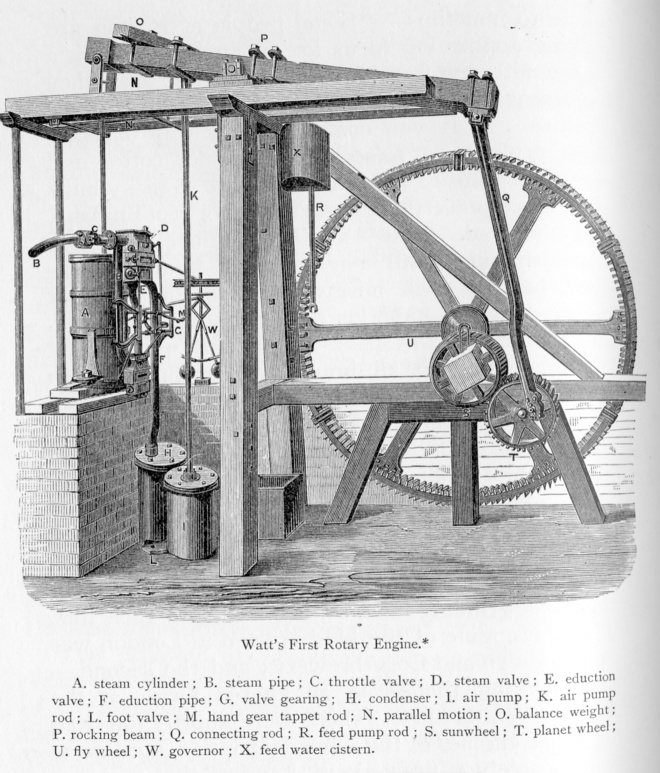

The first rotary engine was made for Mr. Reynolds, of Ketley,

towards the end of 1782, and was used to drive a corn-mill. It

was some time before another order was received, though various

inquiries were made about engines for the purpose of polishing

glass, grinding malt, rolling iron, and such like. The first

engine of the kind erected in London was at Goodwyn and Co.'s

brewery; and the second,—still working, though in an altered

form,—at the Messrs. Whitbread's. These were shortly followed

by other engines of the same description, until there was scarcely a

brewery in London that was not supplied with one.

In the mean time, the works at Soho continued to be fully

employed in the manufacture of pumping-engines. But as the

county of Cornwall was becoming well supplied,—no fewer than

twenty-one having now been erected there, only one of the old

Newcomen construction continuing in work,—it was probable that

before long the demand from that quarter must slacken, if not come

to an end. There were, however, other uses to which the

pumping-engine might be applied; and one of the most promising was

the drainage of the Fen lands. Some adventurers at Soham, near

Cambridge, having made inquiries on the subject, Watt wrote to his

partner, "I look upon these Fens as the only trump card we have left

in our hand." The adventurers proposed that Boulton and Watt

should take an interest in their scheme by subscribing part of the

necessary capital. But Watt decidedly objected to do so, as he

did not wish to repeat his Cornish difficulties in the Fens.

He was willing to supply engines on reasonable terms, but as for

shares he would have none of them. The conclusion he

eventually arrived at with respect to his proposed customers was

this,—"Consider Fen men as Cornish men, only more cunning." |

[p.298]

|

In the midst of his great labours, Boulton was reminded that

he was human. He had for years been working at too high

pressure, and the tear and wear began to tell upon his health.

Watt expostulated with him, telling him that he was trying to do

half-a-dozen men's work; but in vain. He was committed to so

many important enterprises—he had so much at stake—the liabilities

he had to meet from day to day were so heavy—that he was in a

measure forced to be active. To his friend Matthews he

lamented that he was under the necessity of "slaving from morning

till night, working fourteen hours a day, in the drudgery of a

Birmingham manufacturer and hardware merchant." But this could

not last, and before long he was threatened with a breakdown.

His friends Drs. Withering and Darwin urged him at once to "knock

off" and take a long holiday—to leave Soho and its business, its

correspondence, and its visitors, and get as far away from it as

possible.

Acting on their advice, he resolved on making a long promised

visit to Scotland, and he set out on his tour in the autumn of 1783.

He went by Newcastle, where he visited the principal coal mines, and

from thence to Edinburgh, where he had some pleasant intercourse

with Dr. Black and Professor Robison. It is evident from his

letters that he did not take much ease during his journey. "I

talked with Dr. Black and another chemical friend," he wrote,

"respecting my plan for saving alkali at such bleach-grounds as our

fire-engines are used instead of water-wheels: the Doctor did not

start any objections, but, on the contrary, much approved it."

From Edinburgh he proceeded to the celebrated ironworks at Carron, a

place in which he naturally felt a peculiar interest. There

his friend Roebuck had started his great enterprise, and there Watt

had erected his first engine. His visit there, however, was

not so much for curiosity or pleasure, but for business and

experiment. "During my residence in Scotland," said he, "one

month of my time was closely employed at Carron Ironworks in

settling accounts, but principally in making a great number of

experiments on all their iron ores, and in putting them into the

train of making good bar iron, in which I succeeded to my wishes,

although they had never made a single bar of tough iron at Carron

before." In the course of his journey he made a large

collection of fossils for his museum, and the weight of his bags

daily increased. On his way through Ayrshire he called on Lord

Dundonald, a kindred spirit in chemical and mechanical scheming, and

examined his mineral tar works.

Boulton returned to Soho greatly improved in health, and was

shortly immersed as before in the business of the factory. He

found considerable arrears of correspondence requiring to be worked

up. Several of the letters waiting for him were from schemers

of new inventions connected with the steam-engine. Whenever an

inventor thought he had discovered anything new, he at once rushed

to Boulton with it. He was looked upon as the lord and leader

of steam power. His reputation for enterprise and business

aptitude, and the energetic manner in which he had pushed Watt's

invention, were now so widely known, that every new schemer saw a

fortune within his reach could he but enlist Boulton on his side.

Hence much of his time was occupied in replying to letters from

schemers,—inventors of perpetual motion, flying machines, locomotion

by steam, and various kinds of rotary motion. In one of his

letters we find him complaining of so much of his time being "taken

up in answering great numbers of letters he had lately been plagued

with from eccentric persons of no business"; for it was his practice

never to leave a letter unanswered, no matter how insignificant or

unreasonable his correspondent might be.

After a short visit to London, Boulton proceeded into

Cornwall to look after the engines there, and watch the progress of

the mining operations in which by this time he had become so largely

interested. He found the adventurers in a state of general

grumble at the badness of the times, the lowness of prices, the

losses incurred in sinking for ore that could not be found, and the

heaviness of the dues for engine-power payable to Boulton and Watt.

At such times, the partners were usually beset with applications for

abatement, to which they were under the necessity of submitting, to

prevent the mines being altogether closed. Thus the dues at

Chacewater were reduced from £2,500 to £1,000 a year, and the

adventurers were still pressing for further reductions. What

provoked Boulton most, however, was not the loss of dues so much as

the threats which were constantly held out to him that unless the

demands of the adventurers were complied with, they would employ the

Hornblowers.

While Boulton was fighting for dues in Cornwall, and

labouring as before to improve the business management of the mines

in which he was interested as a shareholder, Watt was busily

occupied at Soho in turning out new engines for various purposes, as

well as in perfecting several long-contemplated inventions.

The manufactory, which had for a time been unusually slack, was

again in full work. Several engines were in hand for the

London brewers. Wedgwood had ordered an engine to grind

flints; and orders were coming in for rotative engines for various

purposes, such as driving saw-mills in America and sugar-mills in

the West Indies. Work was, indeed, so plentiful that Watt was

opposed to further orders for rotatives being taken, as the drawings

for them occupied so much time, and they brought in but small

profit. "I see plainly," said he to his partner, "that every

rotation engine will cost twice the trouble of one for raising

water, and will in general pay only half the money. Therefore

I beg you will not undertake any more rotatives until our hands are

clear, which will not be before 1785. We have already more

work in hand than we have people to execute it in the interval."

One reason why Watt was more than usually economical of his time

was, that he was then in the throes of the inventions patented by

him in the course of this year. Though racked by headaches

which, he complained, completely "dumfounded" him and perplexed his

mind, he could not restrain his irrepressible instinct to invent;

and the result was the series of inventions embodied in his patent

of 1784, including, among other things, the application of the

steam-engine to the working of a tilt-hammer for forging iron and

steel, to driving wheel-carriages for carrying persons and goods,

and for other purposes. The specification also included the

beautiful invention of the Parallel Motion, of which Watt himself

said, "Though I am not over anxious after fame, yet I am more proud

of the parallel motion than of any other mechanical invention I have

ever made." Watt was led to meditate this contrivance by the

practical inconvenience which he experienced in communicating the

direct vertical motion of the piston-rod, by means of racks and

sectors, to the angular motion of the working beam. He was

gradually led to entertain the opinion that some means might be

contrived for accomplishing this object by motions turning upon

centres; and, working upon this idea, he gradually elaborated his

invention. So soon as he caught sight of the possible means of

overcoming the difficulty, he wrote to Boulton in Cornwall,—"I have

started a new hare. I have got a glimpse of a method of

causing a piston-rod to move up and down perpendicularly by only

fixing it to a piece of iron upon the beam, without chains or

perpendicular guides or untowardly friction, arch heads, or other

pieces of clumsiness; by which contrivance it answers fully to

expectation. About 5 feet in the height of the house may be

saved in 8-feet strokes, which I look upon as a capital saving, and

it will answer for double engines as well as for single ones.

I have only tried it in a slight model yet, so cannot build upon it,

though I think it a very probable thing to succeed. It is one

of the most ingenious, simple pieces of mechanism I have ever

contrived, but I beg nothing may be said on it till I specify." [p.304]

He immediately set to work to put his idea to the practical

proof, and only eleven days later he wrote,—"I have made a very

large model of the new substitute for racks and sectors, which seems

to bid fair to answer. The rod goes up and down quite in a

perpendicular line without racks, chains, or guides. It is a

perpendicular motion derived from a combination of motions about

centres—very simple, has very little friction, has nothing standing

higher than the back of the beam, and requires the centre of the

beam to be only half the stroke of the engine higher than the top of

the piston-rod when at lowest, and has no inclination to pull the

piston-rod either one way or another, only straight up and down. . .

. However, don't pride yourself on it—it is not fairly tried yet,

and may have unknown faults." [p.305]

Another of Watt's beautiful inventions of the same period, was the

Governor, contrived for the purpose of regulating the speed of the

engine. This was a point of great importance in all cases

where steam-power was employed in processes of manufacture. To

modify the speed of the piston in the single-acting pumping-engine,

Watt had been accustomed to use what is called a throttle-valve,

which was regulated by hand as occasion required. But he saw

that to ensure perfect uniformity of speed, the action of the engine

must be made automatic; and with this object he contrived the

Governor, which has received no improvement since it left his hand.

Two balls are fixed to the ends of arms connected with the

engine by a movable socket, which plays up and down a vertical rod

revolving by a band placed upon the axis or spindle of the flywheel.

According to the centrifugal force with which the balls revolve,

they diverge more or less from the central fixed point, and push up

or draw down the movable collar; which, being connected by a crank

with the throttle-valve, thereby regulates with the most perfect

precision the passage of the steam between the boiler and the

cylinder. When the pressure of steam is great, and the

tendency of the engine is to go faster, the governor shuts off the

steam; and when it is less, the governor opens the throttle-valve

and increases the supply. By this simple and elegant

contrivance the engine is made to regulate its own speed with the

most beautiful precision.

Among the numerous proposed applications of the steam-engine

about this time, was its employment as a locomotive in driving

wheel-carriages. It will be remembered that Watt's friend

Robison had, at a very early period, directed his attention to the

subject; and the idea had since been revived by Mr. Edgeworth, who

laboured with great zeal to indoctrinate Watt with his views.

The latter, though he had but little faith in the project,

nevertheless included the plan of a locomotive engine in his patent

of 1784; but he took no steps to put it in execution, being too much

engrossed with other business at the time. His plan

contemplated the employment of steam either in the form of

high-pressure or low-pressure, working the pistons by the force of

steam only, and discharging it into the atmosphere after it had

performed its office, or discharging it into an air-tight condenser

made of thin plates or pipes, with their outsides exposed to the

wind or to an artificial current of air, thereby economising the

water which would otherwise be lost.

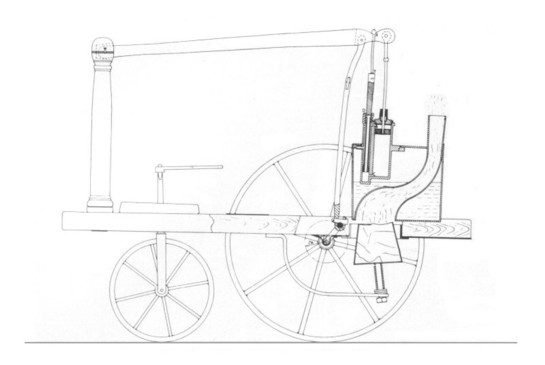

Watt did not carry his design into effect; and, so far as he

was concerned, the question of steam locomotion would have gone no

further. But the subject had already attracted the attention

of William Murdock, who had for some time been occupied during his

leisure hours in constructing an actual working model of a

locomotive. When his model was finished, he proceeded to try

it in the long avenue leading to the parsonage at Redruth, in the

summer of 1784; and in so doing nearly frightened out of his wits

the village pastor, who encountered the hissing, fiery little

machine, while enjoying his evening walk.

William Murdoch's working model of a steam carriage,

or road locomotive, of 1784.

Picture Wikipedia.

When Watt heard of this experiment, he wrote to Boulton

advising that Murdock should be gently counselled to give up his

scheme, which, if pursued, might have the effect of withdrawing him

from the work of the firm, to which he had become increasingly

useful. Boulton accordingly dissuaded Murdock from pursuing

the subject; and we hear nothing further of Murdock's experiments

upon Steam Locomotion.

Notwithstanding Watt's fears of a falling off, the engine

business still continued to prosper in Cornwall. Although the

mining interests were suffering from continued depression, new mines

were being opened out, for which pumping-engines were wanted; and

Boulton and Watt's continued to maintain their superiority over all

others. None of their threatened rivals had yet been able to

exhibit an engine in successful work; and those of the old

construction had been completely superseded. In 1784, new

engines were in course of erection at Poldice, New Poldony, Wheal

Maid, Polgooth, and other mines. The last of the Newcomen

engines in Cornwall had been discarded at Polgooth in favour of one

of Boulton and Watt's 58-inch cylinder engines.

The dues paid yearly in respect of these and other engines

previously erected were very considerable; Boulton estimating that,

if duly paid, they would amount to about £12,000 a year. There

seemed, therefore, every reasonable prospect of the financial

difficulties of the firm at last coming to an end.

Boulton's visit to Cornwall on this occasion was enlivened by

the companionship of his wife, and her friend Miss Mynd.

Towards midsummer he looked forward with anticipations of increased

pleasure to the visit of his two children—his son Matt and his

daughter Nancy—during their school holidays. It was a source

of much regret to him, affectionate as his nature was, that the

engrossing character of his business prevented him from enjoying the

society of his family so much as he desired. But he

endeavoured to make up for it by maintaining a regular

correspondence with them when absent.

His letters to his children were full of playfulness,

affection, and good advice. To his son at school he wrote,

telling him of his life in Cornwall, describing to him the house at

Cosgarne, the garden and the trees which he had planted in it, the

pleasant rides in the neighbourhood, and the visit he had just been

paying to the top of Pendennis Castle, from which he had seen about

a hundred sail of ships at sea, and a boundless prospect of land and

water. He proceeded to tell him of the quantity of work he did

connected with the engine business,—how he had no clerk to assist

him, but did all the writing and drawing of plans himself: "When I

have time," said he, "I pick up curiosities in ores for the purpose

of assays, for I have a laboratory here. There is nothing

would so much add to my pleasure as having your assistance in making

solutions, precipitates, evaporations, and crystallisations."

After giving his son some good advice as to the cultivation

of his mind, as being calculated to render him an intelligent and

useful member of society, he proceeded to urge upon him the duty of

cultivating polite manners, as a means of making himself agreeable

to others, and at the same time of promoting his own comfort.

"But remember," he added, "I do not wish you to be polite at the

expense of honour, truth, sincerity, and honesty; for these are the

props of a manly character, and without them politeness is mean and

deceitful. Therefore, be always tenacious of your honour.

Be honest, just, and benevolent, even when it appears difficult to

be so. I say, cherish those principles, and guard them as

sacred treasures."

At length his son and daughter joined him and took part in

his domestic and outdoor enjoyments. They accompanied him in

his drives and rides, and Matt took part in his chemical

experiments. One of their great delights was the fabrication

of an immense paper balloon, and the making of the hydrogen gas to

fill it with. After great preparations the balloon was made

and filled, and sent up in the field behind the house, to the

delight of the makers, and of the villagers who surrounded Cosgarne.

To Mrs. Watt he wrote expressing to her how much pleasanter

his residence in Cornwall had become since his son's and daughter's

visit. "I shall be happier," he said, "during the remainder of

my residence here than in the former part of it; for I am ill

calculated to live alone in an enemy's country, and to contest

lawsuits. Besides, the only source of happiness I look for in

my future life is in my children. Matt behaves extremely well,

is active and good-humoured; and my daughter, too, has, I think,

good dispositions and sentiments, which I shall cherish, and prevent

as much as possible from being sullied by narrow and

illiberal-minded companions."

After a few months' pleasant social intercourse with his

family at Cosgarne, varied by occasional bickerings with the

adventurers out of doors about dues, Boulton returned to Birmingham,

to enter upon new duties and undertake new enterprises.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIV.

COMMERCIAL POLITICS—THE ALBION MILLS—RIOTS IN CORNWALL—PROSPERITY OF

BOULTON AND WATT.

WHEN Boulton

returned to Birmingham, he was urgently called upon to take part in

a movement altogether foreign to his habits. He had heretofore

been too much engrossed by business to admit of his taking any

active part in political affairs. Being, however, of an active

temperament, and mixing with men of all classes, he could not but

feel an interest in the public movements of his time. Early in

1784, we find him taking the lead in getting up a loyal address to

the King on the resignation of the Portland Administration and the

appointment of Mr. Pitt as Prime Minister. It appears,

however, that Pitt disappointed his expectations. One of his

first projects was a scheme of taxation, which he introduced for the

purpose of remedying the disordered state of the finances, but

which, in Boulton's opinion, would, if carried, have had the effect

of seriously damaging the national industry.

The Minister proposed to tax coal, iron, copper, and other

raw materials of manufacture, to the amount of about a million a

year. Boulton immediately bestirred himself to oppose the

adoption of the scheme. He held that for a manufacturing

nation to tax the raw materials of wealth was a suicidal measure,

calculated, if persevered in, to involve the producers of wealth in

ruin. Let taxes," he said, "be laid upon luxuries, upon vices, and,

if you like, upon property; tax riches when got, and the expenditure

of them, but not the means of getting them; but of all things, don't

cut open the hen that lays the golden eggs." [p.312]

Petitions and memorials were forthwith got up in the midland

counties, and presented against the measure; and Boulton being

recognised as the leader of the movement in his district, was

summoned by Mr. Pitt to London to an interview with him on the

subject. He then took the opportunity of pressing upon the

Minister the necessity of taking measures to secure reciprocity of

trade with foreign nations, as being of vital importance to the

trade of England. Writing to his partner, Scale, he said,

"Surely our Ministers must be bad politicians, to suffer the gates

of nearly every commercial city in the world to be shut against us."

"There is no doubt," he wrote to his friend Garbett, "but the

edicts, prohibitions, and high duties laid upon our manufacturers by

foreign powers will be severely felt, unless some new commercial

treaties are entered into with such powers. I fear our young

Minister is not sufficiently aware of the importance of the subject,

and I likewise fear he will pledge himself before Parliament meets

to carry other measures in the next session that will be as odious

to the country as his late attempts."

As Boulton had anticipated, the Ministry introduced several

important measures, calculated to have a highly injurious effect

upon English industry, and he immediately bestirred himself, in

conjunction with Josiah Wedgwood, of Etruria, to organise a movement

in opposition to them. Wedgwood and Boulton met at Birmingham,

in February 1785, and arranged to assemble a meeting of delegates

from the manufacturing districts, who were to meet and sit in London

"all the time the Irish commercial affairs were pending." A

printed statement of the objects of the movement was circulated, and

Boulton and Wedgwood wrote to their friends in all quarters to meet

and appoint delegates to the central committee in London.

Boulton was unanimously appointed the delegate for Birmingham, and

he proceeded to London furnished with a bundle of petitions from his

neighbourhood. The delegates proceeded to form themselves into

a Chamber of Manufacturers, over the deliberations of which

Wedgwood, Boulton, or John Wilkinson usually presided.

The principal object of these meetings and petitionings was

to prevent, if possible, the imposition of the proposed taxes on

coal, iron, and raw materials generally, as well as the proposed

export duties on manufactured articles. At a time when foreign

governments were seeking to exclude English manufactures from their

dominions by heavy import duties, it was felt that this double

burden was more than English industry could bear. The Irish

Parliament were at the same time legislating in a hostile spirit

towards English commerce; imposing taxes upon all manufactures

imported into Ireland from England, while Irish manufactures were

not only sent into England duty free, but their own parliament

encouraged them by a bounty on exportation. The committee

strongly expostulated against the partial and unjust spirit of this

legislation, and petitioned for free interchange on equal terms.

So long as such a state of things continued, the petitioners urged

that "every idea of reciprocity in the interchange of manufactures

between Britain and Ireland was a mere mockery of words."

Although Watt was naturally averse to taking any public part

in politics, his services were enlisted in the cause, and he drew up

for circulation, "An answer to the Treasury Paper on the Iron Trade

of England and Ireland." The object of his statement was to

show that the true way of encouraging manufactures in Ireland was,

not by bounties, not by prohibitions, but by an entire freedom of

industry. It was asserted by the supporters of the

propositions, that the natives of Ireland were ignorant, indolent,

and poor. "If they be so," said Watt, "the best method of

giving them vigour is to have recourse to British manufacturers,

possessed of capital, industry, and knowledge of trade." The

old covenanting spirit of his race fairly breaks out in the

following passage:—

"It is contemptible nonsense to

argue that because Ireland has never had iron manufactories she

cannot soon have them. . . . One hundred years ago the Irish had no

linen manufacture; they imported linen; and now they sell to us to

the amount of a million annually. How came this about?

The civil wars under Charles I., and the tyranny of the Scotch Privy

Council under Charles II., chased the people out of Scotland because

they were Presbyterians. Ireland received and protected them;

they peopled the northern provinces; many of them were weavers; they

followed their business in Ireland, and taught others. Philip

II. chased the inhabitants out of Flanders, on account of religion;

Queen Elizabeth received and protected them; and England learnt to

manufacture woollen cloth. The persecutions of Lewis XIV.

occasioned the establishment of a colony in Spitalfields. And

the Parliament of Britain, under the auspices of—and—, and others,

imposed oppressive duties on glass; and —'s Act gave the Irish

liberty to export it to our Colonies; the glass-makers fled from the

tyranny of the excise; Ireland has now nine glass-houses.

Britain has lost the export trade of that article! More

examples of the migrations of manufactures could be adduced, but it

seems unnecessary; for it cannot be denied that men will fly from

tyranny to liberty, whether Philip's Priests, Charles's Dragoons, or

our Excisemen, be the instruments of the tyranny. And it must

also be allowed that even the Inquisition itself is not more

formidable than our Excise Laws (as far as property is concerned) to

those who unhappily are subjected to them."

Towards the end of the statement he asks, "Would it not be

more manly and proper at once to invite the Irish to come into a

perfect union with Britain, and to pay the same duties and excises

that we do? Then every distinction of country might with

justice be done away with, and they would have a fair claim to all

the advantages which we enjoy."

The result of the agitation was that most of the proposals to

impose new taxes on the raw materials of manufacture were withdrawn

by the Ministry, and the Irish resolutions were considerably

modified. But the relations of British and Irish industry were

by no means settled. The Irish Parliament might refuse to

affirm the resolutions adopted by the British Parliament, in which

case it might be necessary again to oppose the Ministerial measures;

and to provide for this contingency, the delegates separated, with

the resolution to maintain and extend their organisation in the

manufacturing districts. Watt did not, however, like the idea

of his partner becoming engrossed in political agitation, even in

matters relating to commerce. He accordingly wrote to Boulton

in London, "I find myself quite unequal to the various business now

lying behind, and wish much that you were at home, and that you

would direct your attention solely to your own and to Boulton and

Watt's business until affairs can be brought into reasonable

compass."

Watt was at this time distressed by an adverse decision

against the firm in one of the Scotch courts. "I have

generally observed," he wrote, "that there is a tide in our affairs.

We have had peace for some time, but now cross accidents have begun,

and more are to be feared." His anxieties were increased by

the rumour which reached his ears from several quarters of a grand

combination of opulent manufacturers to make use of every beneficial

patent that had been taken out, and cut them down by scire facias,

as they had already cut down Arkwright's. It was said that

subscriptions had been obtained by the association amounting to

£50,000. Watt was requested to join a counter combination of

patentees to resist the threatened proceedings. To this,

however, he objected, on the ground that the association of men to

support one another in lawsuits was illegal, and would preclude the

members from giving evidence in support of each other's rights.

"Besides," he said, "the greater number of patentees are such as we

could not associate with, and if we did, it would do us more harm

than good."

Towards the end of 1785 the engines which had been in hand

were nearly finished, and work was getting slacker than usual at

Soho. Though new orders gave Watt much trouble, and occasioned

him anxiety, still he would rather not be without them. It was

matter of gratification to him to be able to report that the engines

last delivered had given great satisfaction. The mechanics

were improving in skill, and their workmanship was becoming of a

superior character. "Strood and Curtis's engine," said he,

"has been at work some time, and does very well. Whitbread's

has also been tried, and performs exceedingly well." The

success of Whitbread's engine was such that it had the honour of a

visit from the King, who was greatly pleased with its performances.

Not to be outdone, "Felix Calvert," wrote Watt, "has bespoken one,

which is to outdo Whitbread's in magnificence."

The slackness of work at Soho was not of long continuance.

Orders for rotative engines came in gradually; one from Harris, of

Nottingham; another from Macclesfield, to drive a silk-mill; a third

from Edinburgh, for the purposes of a distillery; and others from

different quarters. The influx of orders had the effect at the

same time of filling Soho with work, and plunging Watt into his

usual labyrinth of perplexity and distress. In September we

find him writing to Boulton, "My health is so bad that I do not

think I can hold out much longer, at least as a man of business, and

I wish to consolidate something before I give over . . . . again, I

cannot help being dispirited, because I find my head fail me much,

business an excessive burden to me, and little prospect of my speedy

release from it. Were we both young and healthy, I should see

no reason to despair, but very much the contrary. However, we

must do the best we can, and hope for quiet in heaven when our weary

bones are laid to rest." [p.317]

A few months later, so many more orders had come in, that

Watt described Soho as "fast for the next four months," but the

additional work only had the effect of increasing his headaches.

"In the anguish of my mind," he wrote, "amid the vexations

occasioned by new and unsuccessful schemes, like Lovelace, I 'curse

my inventions,' and almost wish, if we could gather our money

together, that somebody else should succeed in getting our trade

from us. However, all may yet be well. Nature can be

conquered if we can but find out her weak side."

We return to the affairs of the Cornish copper-miners, which

were now in a very disheartening condition. The mines were

badly and wastefully worked; and the competition of many small

companies of poor adventurers kept the copper trade in a state of

permanent depression. In this crisis of their affairs it was

determined that a Copper Company should be formed, backed by ample

capital, with the view of regulating this important branch of

industry, and rescuing the mines and miners from ruin. Boulton

took an active part in its formation, and induced many of his

intimate friends in the north to subscribe largely for shares.

An arrangement was entered into by the Company with the adventurers

in the principal mines, to buy of them the whole of the ore raised,

at remunerative prices, for a period of eleven years.

At the first meeting, held in September, 1785, for the

election of Governor, Deputy-Governor, and Directors, Boulton held

in his hands the power of determining the appointments,

representing, as he did by proxy, shares held by his northern

friends to the amount of £86,000. The meeting took place in

the Town-hall at Truro, and the proceedings passed off

satisfactorily; Boulton using his power with due discretion.

"We met again on Friday," he wrote to Matthews, "and chose the

assayers and other subordinate officers, after which we paid our

subscriptions, and dined together, all in good humour; and thus this

important revolution in the copper trade was finally settled for

eleven years."

Matters were not yet, however, finally settled as many

arrangements, in which Boulton took the leading part, had to be made

for setting the Company to work; the Governor and Directors pressing

him not to leave Cornwall until they were definitely settled.

It happened to suit his convenience to remain until the Wheal

Fortune engine was finished—one of the most formidable engines the

firm had yet erected in Cornwall. In the mean time he entered

into correspondence with various consumers of copper at home and

abroad, with the object of finding a vend for the metal. He

succeeded in obtaining a contract through Mr. Hope, of Amsterdam,

for supplying the copper required for the new Dutch coinage; and he

opened out new markets for the produce in other quarters.

Being a large holder of mining shares, Boulton also tried to

introduce new and economical methods of working the mines; but with

comparatively little result.

Though actively bestirring himself for the good of the mining

interest, Boulton had but small thanks for his pains. The

prominence of his position had this disadvantage, that if the price

of the ore went down, or profits declined, or the yield fell off, or

the mines were closed, or anything went wrong, the miners were but

too ready to identify him in some way with the mischief; and the

services which he had rendered to the mining interest were in a

moment forgotten. On one occasion the discontent of the miners

broke out into open revolt, and Boulton was even threatened with

personal violence. The United Mines having proved unprofitable

in the working, notice was given by the manager of an intended

reduction of wages, this being the only condition on which the mines

could be carried on. If this could not be arranged, the works

must be closed, as the adventurers declined to go on at a loss.

On the announcement of the intended lowering of wages being

made, there was great excitement and discontent among the

workpeople. Several hundreds of them hastily assembled at

Redruth, and took the road for Truro, to pull down the offices of

the Copper Mining Company, and burn the house of the manager.

They were especially furious with Boulton, vowing vengeance on him,

and declaring that they would pull down every pumping-engine he had

set up in Cornwall. When the rioters reached Truro, they found

a body of men, hastily armed with muskets taken from the arsenal,

stationed in front of the Copper Mining Company's premises,

supported by six pieces of cannon. At sight of this formidable

demonstration, the miners drew back, and, muttering threats that

they would repeat their visit, returned to Redruth.

This was, however, but the wild and unreasoning clamour of

misguided and ignorant men. Boulton was personally much

esteemed by all who were able to appreciate his character, and to

understand the position of himself and his partner with reference to

the engine patent. The larger mining owners invited him to

their houses, and regarded him as their friend. The more

intelligent of the managers were his strenuous supporters.

First and foremost among these was Mr. Phillips, manager of the

Chacewater mines, of whom he always spoke with the highest respect,

as a man of the most scrupulous integrity and honour. Mr.

Phillips was a member of the Society of Friends, and his wife

Catherine was one of the most celebrated preachers of the body.

Boulton and Watt occasionally resided with them before the house at

Cosgarne was taken, and conceived for both the warmest friendship.

If Watt was attracted by the Cornish Anabaptists, Boulton was

equally attracted by the Cornish Quakers. We find him, in one

of his letters to Mrs. Boulton, describing a great meeting of

Friends at Truro which he had attended, "where," he said, "I heard

our friend Catherine Phillips preach with great energy and good

sense for an hour and a half, although so weak in body that she was

obliged to lie abed for several days before." Boulton

afterwards dined with the whole body of Friends at the principal

inn, being the only person present who was not of the Society; and

he confessed to have spent in their company a very pleasant evening.

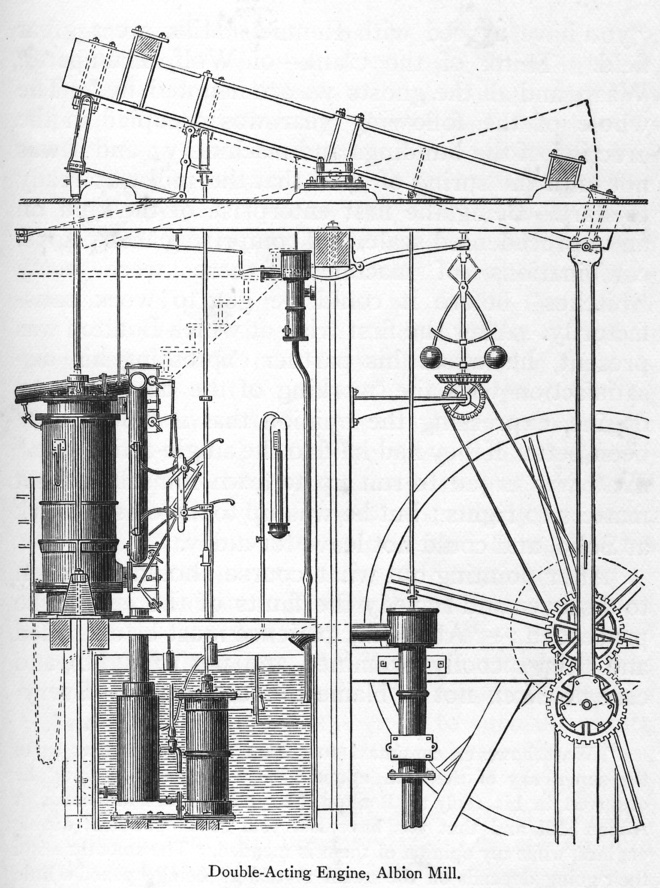

We return to the progress of the engine business at Soho.

The most important work in hand about this time was the

double-acting engine intended for the Albion Mill, in Southwark. [p.321]

This was the first rotative with a parallel motion erected in London

and as the more extended use of the engine would in a great measure

depend upon its success, the firm naturally looked forward with very

great interest to its performances. The Albion Mill scheme was

started by Boulton as early as 1783. Orders for rotatives were

then coming in very slowly, and it occurred to him that if he had

but the opportunity of exhibiting the powers of the new engine in

its best form, and in connexion with the best machinery, the results

would be so satisfactory and conclusive as to induce manufacturers

generally to follow the example. On applying to the London

capitalists, Boulton found them averse to the undertaking; and at

length Boulton and Watt became persuaded that if the concern was to

be launched at all, they must themselves find the principal part of

the capital. A sufficient number of shareholders was got

together to make a start, and application was made for a charter of

incorporation in 1784; but it was so strongly opposed by the millers

and mealmen, on the ground that the application of steam-power to

flour-grinding would throw wind and water-mills out of work, take

away employment from the labouring classes, and reduce the price of

bread, [p.322] that the

charter was refused; and the Albion Mill Company was accordingly

constituted on the ordinary principles of partnership. |

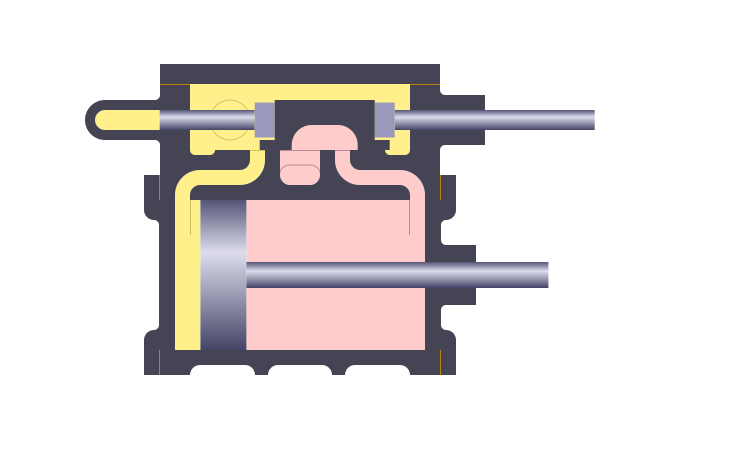

Ed.—a double acting reciprocating engine, showing the

valve-gear and governor (live steam

from the boiler is in red, steam exhausted to the condenser

is in blue). Picture Wikipedia.

|

Ed.—a closer view of a

double-acting engine's cylinder and piston. Above it is the

"steam chest" and the "slide valve", which control the flow of live

and exhaust steam. The amount of travel by the slide valve

also controls the amount of live steam injected into the cylinder at

each stroke (the "cut-off"), thereby determining how "expansively"

the steam is to work, which in turn affects fuel economy.

Picture Wikipedia. |

|

Ed.—application of the

double-acting steam reciprocating engine to a railway

locomotive. Note the action of the "reverser"

on the valve-gear in order to change the direction of rotation of

the locomotive's driving wheels. Picture Wikipedia. |

|

Ed.—a three cylinder

"compound" steam reciprocating engine. A type much used for

marine propulsion, improved fuel economy was obtained by passing the

steam through three stages of expansion before exhausting it to the

condenser, thus maximising heat use. Four cylinder compound

marine engines were also built, although less common. Picture

Wikipedia. |

|

By the end of the year the Albion Mill engines, carefully

designed by Watt, were put in hand at Soho; the building was in

course of erection, after the designs of Mr. Wyatt, the architect;

while John Rennie, the young Scotch engineer, was engaged to design

and fit up the flour-grinding and dressing machinery. "I am

glad," wrote Boulton to Watt, "you have agreed with Rennie. Mills

are a great field. Think of the crank—of Wolf, Trumpeter,

Wasp, and all the ghosts we are haunted by." The whole of the

following year was occupied in the erection of the buildings and

machinery; and it was not until the spring of 1786 that the mill was

ready to start. Being the first enterprise of the kind, on an

unprecedented scale, and comprising many novel combinations of

machinery, there were many "hitches" before it could be got to work

satisfactorily. After the first trial, at which Boulton was

present, he wrote his partner expressing his dissatisfaction with

the working of the double-acting engine, expressing the opinion that

it would have been better if they had held to the single-acting one.

[p.324] Watt was

urged to run up to town himself and set matters to rights; but he

was up to the ears in work at Soho, and could not leave for a day.

.jpg)

Ed.—John Rennie (1761-1821): Scottish civil engineer,

the designer of many bridges,

canals and docks. Portrait by Sir Henry Raeburn

(1810). Picture Wikipedia.

After pointing out what course should be taken to discover

and remedy the faults of the engine, he proceeded:—

"Above all, patience must be exercised and things

coolly examined and put to rights, and care be taken not to blame

innocent parts. Everything must, as much as possible, be tried

separately. Remind those who begin to growl, that in new,

complicated and difficult things, human foresight falls short—that

time and money must be given to perfect things and find out their

defects, otherwise they cannot be remedied." [p.325]

The cost of erecting the mill proved to be considerably in

excess of the original estimate, and Watt early feared that it would

turn out a losing concern. He had no doubt about the engines

or the machinery being able to do all that had been promised but he

feared that the absence of business capacity on the part of the

managers would be fatal to its commercial success. He was

especially annoyed at finding the mill made a public show of, and

that it was constantly crowded with curious and frivolous people,

whose presence seriously interfered with the operations of the

workmen. It reached his ears that the managers of the mill

even intended to hold a masquerade in it, with the professed object

of starting the concern with éclat! Watt denounced this

as sheer humbug. "What have Dukes, Lords, and Ladies," said

he, "to do with masquerading in a flour-mill? You must take

steps to curb the vanity of ―― else it will ruin him. As for

ourselves, considering that we are much envied at any rate,

everything which contributes to render us conspicuous ought to be

avoided. Let us content ourselves with doing."

When the mill was at length set to work, the engine performed

to the entire satisfaction of its projector. The usual rate of

work per week of six days was 16,000 bushels of wheat, cleaned,

ground, and dressed into fine flour (some of it being ground two or

three times over)—or sufficient, according to Boulton's estimate,

for the weekly consumption of 150,000 people. The important

uses of the double rotative engine were exhibited in the most

striking manner; and the fame of the Albion Mill extended far and

wide.

It so far answered the main purpose which Boulton and Watt

had in view in originally embarking in the enterprise; but it must

be added that the success was accomplished at a very serious

sacrifice. The mill never succeeded commercially. It was

too costly in its construction and in its management, and though it

did an immense business, it was done at a loss. The concern,

was, doubtless, capable of great improvement, and, had time been

allowed, it would probably have come round. When its prospects

seemed to be brightening, [p.326-1]

it was set on fire in several places by incendiaries on the night of

the 3rd of March, 1791. The villains had made their

arrangements with deliberation and skill. They fastened the

main cock of the water-cistern, and chose the hour of low tide for

firing the building, so that water could not be got to play upon the

flames, and the mill was burnt to the ground in a few hours. A

reward was offered for the apprehension of the criminals, but they

were never discovered. The loss sustained by the Company was

about £10,000. Boulton and Watt were the principal sufferers;

the former holding £6,000 and the latter £3,000 interest in the

undertaking. [p.326-2]

Meanwhile, orders for rotative engines were coming in apace

at Soho,—engines for paper-mills and cotton-mills, for flour-mills

and iron-mills, and for sugar-mills in America and the West Indies.

At the same time pumping-engines were in hand for France, Spain, and

Italy. The steam-engine was becoming an established power, and

its advantages were every day more clearly recognised. It was

alike docile, regular, economical, and effective, at all times and

seasons, by night as by day, in summer and in winter. While

the wind-mills were stopped by calms and the water-mills by frosts,

the steam-mill worked on with untiring power. "There is not a

single water-mill now at work in Staffordshire," wrote Boulton to

Wyatt in December; "they are all frozen up, and were it not for

Wilkinson's steam-mill, the poor nailers must have perished; but his

mill goes on rolling and slitting ten tons of iron a day, which is

carried away as fast as it can be bundled up; and thus the

employment and subsistence of these poor people are secured."

As the demand for rotative engines set in, Watt became more

hopeful as to the prospects of this branch of manufacture. He

even began to fear lest the firm should be unable to execute the

orders, so fast did they follow each other. "I have no doubt,"

he wrote to Boulton, "that we shall soon so methodize the rotative

engines as to get on with them at a great pace. Indeed, that

is already in some degree the case. But we must have more men,

and these we can only have by the slow process of breeding them." [327]

Want of skilled workmen was one of Watt's greatest

difficulties. When the amount of work to be executed was

comparatively small, and sufficient time was given to execute it, he

was able to turn out very satisfactory workmanship; but when the

orders came pouring in, new hands were necessarily taken on, who

proved a constant source of anxiety and trouble. Even the "old

hands," when sent to a distance to fit up engines, being left, in a

great measure, to themselves, were apt to become careless and

ill-conditioned. With some, self-conceit was the

stumbling-block, with others temper, but with the greater number,

drink.

Another foreman sent to erect an engine in Craven was

afflicted with a distemper of a different sort. He was found

to have put the engine very badly together, and, instead of

attending to his work, had gone a-hunting in a pig-tail wig!

William Murdock continued, as before, an admirable exception.

He was as indefatigable as ever, always ready with an expedient to

remedy a defect, and willing to work at all hours. A great

clamour had been raised in Cornwall during his stay in London while

setting the Albion Mill to rights, as there was no other person

there capable of supplying his place, and fulfilling his numerous

and responsible duties. Boulton deplored that more men such as

Murdock were not to be had; "He is now flying from mine to mine," he

wrote, "and hath so many calls upon him that he is inclined to grow

peevish; and if we take him from North Downs, Chacewater, and Towan

(all of which engines he has the care of), they will run into

disorder and ruin; for they have not a man at North Downs that is

better than a stoker."

Towards the end of 1786 the press of orders increased at

Soho. A rotative engine of forty horse-power was ordered by

the Plate Glass Company to grind glass. A powerful

pumping-engine was in hand for the Oxford Canal Company. Two

engines, one of twenty and the other of ten horse-power, were

ordered for Scotch distilleries, and another order was shortly

expected from the same quarter. The engine supplied for the

Hull paper-mill having been found to answer admirably, more orders

for engines for the same purpose were promised. At the same

time pumping-engines were in hand for the great French waterworks at

Marly. "In short," said Watt, "I foresee I shall be driven

almost mad in finding men for the engines ordered here and coming

in."

Watt was necessarily kept very full of work by these orders,

and we gather from his letters that he was equally full of

headaches. He continued to give his personal attention to the

preparation of the drawings of the engines, even to the minutest

detail. On an engine being ordered by Mr. Morris, of Bristol,

for the purpose of driving a tilt-hammer, Boulton wrote to him,—"Mr.

Watt can never be prevailed upon to begin any piece of machinery

until the plan of the whole is settled, as it often happens that a

change in one thing puts many others wrong. However, he has

now settled the whole of yours, but waits answers to certain

questions before the drawings for the founder can be issued."

At an early period his friend Wedgwood had strongly urged

upon Watt that he should work less with his own head and hands, and

more through the heads and hands of others. Watt's brain was

too active for his body, and needed rest; but rest he would not

take, and persisted in executing all the plans of the new engines

himself. Thus in his fragile, nervous, dyspeptic state, every

increase of business was to him increase of brain-work and increase

of pain; until it seemed as if not only his health, but the very

foundations of his reason must give way. At the very time that

Soho was beginning to bask in the sunshine of prosperity, and the

financial troubles of the firm seemed coming to an end, Watt wrote

the following profoundly melancholy letter to a friend:—

"I have been effete and listless, neither daring to

face business, nor capable of it, my head and memory failing me

much; my stable of hobby-horses pulled down, and the horses given to

the dogs for carrion. . . . I have had serious thoughts of laying

down the burden I find myself unable to carry, and perhaps, if other

sentiments had not been stronger, should have thought of throwing

off the mortal coil; but, if matters do not grow worse, I may

perhaps stagger on. Solomon said that in the increase of

knowledge there is increase of sorrow; if he had substituted

business for knowledge, it would have been perfectly true." [p.330]

As might be expected, from the large number of engines

already sold by the firm, and from the increasing amounts yearly

payable as dues, their income from the business was becoming

considerable, and promised, before many years had passed, to be very

large. Down to the year 1785, however, the outlay upon new

foundries, workshops, and machinery had been so great, and the large

increase of business had so completely absorbed the capital of the

firm, that Watt continued to be paid his household expenses, at the

rate of so much a year, out of the hardware business, and no

division of profits upon the engines sold and at work had as yet

been made, because none had accrued.

After the lapse of two or more years, matters had completely

changed; and after long waiting, and indescribable distress of mind

and body, Watt's invention at length began to be productive.

During the early part of his career, though his income had been

small, his wants were few, and easily satisfied. Though

Boulton had liberally provided for these from the time of his

settling at Birmingham, Watt continued to feel oppressed by the

thought of the debt to the bankers for which he and his partner were

jointly liable. In his own little business at Glasgow, he had

been accustomed to deal with such small sums, that the idea of being

responsible for the repayment of thousands of pounds appalled and

unnerved him; and he had no peace of mind until the debt was

discharged.

Now at last he was free, and in the happy position of having

a balance at his bankers. On the 7th of December, 1787,

Boulton wrote to Matthews, the London agent,—"As Mr. Watt is now at

Mr. Macgregor's, in Glasgow, I wish you would write him a line to

say that you have transferred £4,000 to his own account, that you

have paid for him another £1,000 to the Albion Mill, and that about

Christmas you suppose you shall transfer £2,007 more to him, to

balance."

But while Watt's argosies were coming into port richly laden,

Boulton's were still at sea. Though the latter had risked, and

often lost, capital in his various undertakings, he continued as

venturesome, and as enterprising as ever. When any project was

started calculated to bring the steam-engine into notice, he was

immediately ready with his subscription. Thus he embarked

£6,000 in the Albion Mill, a luckless adventure in itself, though

productive in other respects. But he sadly missed the money,

and as late as 1789, feelingly said to Matthews, "Oh, that I had my

Albion Mill capital back again!" When any mining adventure was

started in Cornwall for which a new engine was wanted, Boulton would

write, "If you want a stop-gap, put me down as an adventurer"; and

too often the adventure proved a failure. Then, to encourage

the Cornish Copper Mining Company, he bought large quantities of

copper, and had it sent down to Birmingham, where it long lay on his

hands without a purchaser. At the same time we find him

expending £5,000 in building and rebuilding two mills and a

warehouse at Soho, and an equal amount in "preparing for the

coinage."

These large investments had the effect of crippling his

resources for years to come; and when the commercial convulsion of

1788 occurred, he felt himself in a state of the most distressing

embarrassment. The circumstances of the partners being thus in

a measure reversed, Boulton fell back upon Watt for temporary help;

but, more cautious than his partner, Watt had already invested his

profits elsewhere, and could not help him. [p.332]

He had got together his store of gains with too much difficulty to

part with them easily; and he was unwilling to let them float away

in what he regarded as an unknown sea of speculation.

To add to his distresses, Boulton's health again began to

fail him. To have seen the two men, no one would have thought

that Boulton would have been the first to break down; but so it was.

Though Watt's sufferings from headaches, and afterwards from asthma,

seem to have been almost continuous, he struggled on, and even grew

in strength and spirits. His fragile frame bent before

disease, as the reed bends to the storm, and rose erect again; but

it was different with Boulton. He had toiled too unsparingly,

and was now feeling the effects. The strain upon him had

throughout been greater than upon Watt, whose headache had acted as

a sort of safety-valve by disabling him from pursuing further study

until it had gone off. Boulton, on the other hand, was kept in

a state of constant anxiety by business that could not possibly be

postponed. He had to provide the means for carrying on his

many businesses, to sustain his partner against despondency, and to

keep the whole organisation of the firm in working order.

While engaged in bearing his gigantic burden, disease came

upon him. In 1784 we find him writing to his wine-merchant,

with a cheque in payment of his account,—"We have had a visit from a

new acquaintance—the gout." The visitor returned, and four

years later we find him complaining of violent pain from gravel and

stone, to which he continued a martyr to the close of his life.

"I am very unwell indeed," he wrote to Matthews in London; "I can

get no sleep; and yet I have been obliged to wear a cheerful face,

and attend all this week on M. l'Abbé de Callone and his friend

Brunelle." He felt as if life was drawing to an end; he asked

his friend for a continuance of his sympathy, and promised still to

exert himself, "otherwise," said he, "I will lay me down and die."

He was distressed, above all things, at the prospect of leaving his

family unprovided for, notwithstanding all the labours, anxieties,

and risks he had undergone.

"When I reflect," he said, "that I

have given up my extra advantage of one-third on all the engines we

are now making and are likely to make, [p.334]—when

I think of my children now upon the verge of that time of life when

they are naturally entitled to expect a portion of their

patrimony,—when I feel the consciousness of being unable to restore

to them the property which their mother entrusted to me,—when I see

all whom I am connected with growing rich, whilst I am groaning

under a load of debt and annuities that would sink me into the grave

if my anxieties for my children did not sustain me,—I say, when I

consider all these things, it behoves me to struggle through the

small remaining fragment of my life (being now in my 6oth year), and

do my children all the justice in my power by wiping away as many of

my encumbrances as possible."

It was seldom that Boulton wrote in so desponding a strain as

this; but it was his "darkest hour," and happily it proved the one

"nearest the dawn." Yet, we shortly after find him applying