|

CHAPTER X.

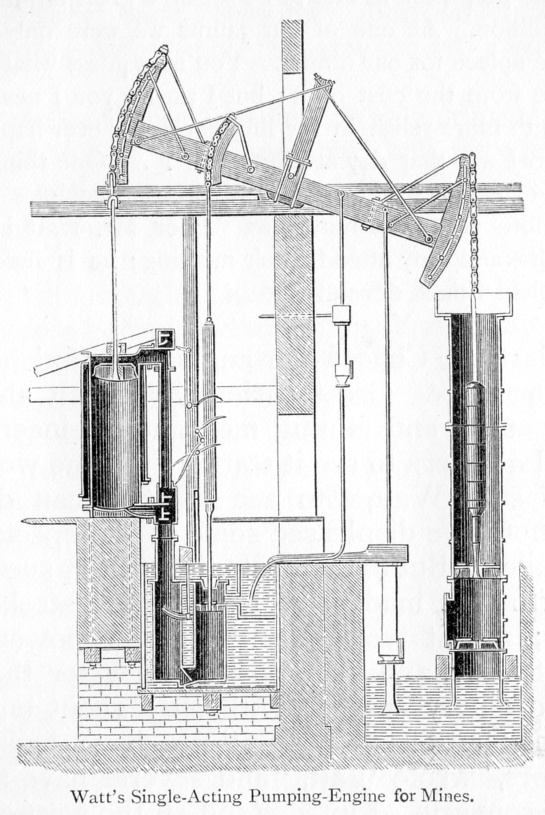

WATT IN CORNWALL—INTRODUCTION OF PUMPING-ENGINES.

THE Cornish miners continued

baffled in their attempts to get rid of the water, which hindered

the working of their mines. The Newcomen engines had been

taxed to the utmost, but were unable to send the workmen deeper into

the ground. The mine owners were accordingly ready to welcome

any invention that promised to relieve them of their difficulty.

Among the various new contrivances for pumping water, that of Watt

seemed to offer the greatest advantages; and if what was alleged of

it proved true, it could not fail to prove of the greatest advantage

to Cornish industry.

Long before Watt's arrival in Birmingham, the Cornishmen had

been in correspondence with Boulton, making inquiries about the new

Scotch invention, of which they had heard; and Dr. Small, in his

letters to Watt, repeatedly urged him to perfect his engine, with a

view to its being employed in the drainage of the Cornish mines.

Now that the engine was at work in several places, Boulton invited

his correspondents in Cornwall to inquire as to its performances, at

Soho, or Bedworth, or Bow, or any other place where it had been

erected. The result of the inquiry was satisfactory, and

several orders for engines for Cornwall were received at Soho by the

end of 1776. The two first were those ordered for Wheal Busy,

near Chacewater, and for Tingtang, near Redruth. The materials

for the former were shipped by the middle of 1777; and, as much

would necessarily depend upon the successful working of the first

engines put up in Cornwall, Watt himself went to superintend their

erection.

Watt reached his destination after a long and tedious journey

over bad roads. He rode by stage as far as Exeter, and posted

the rest of the way. At Chacewater he found himself in the

midst of perhaps the richest mining district in the world.

From thence to Camborne, which lies to the west, and Gwennap to the

south, there is a constant succession of mines. The earth has

been burrowed in all directions for miles upon miles in search of

ore, principally copper—the surface presenting an unnaturally

blasted and scarified appearance by reason of the "deads" or refuse

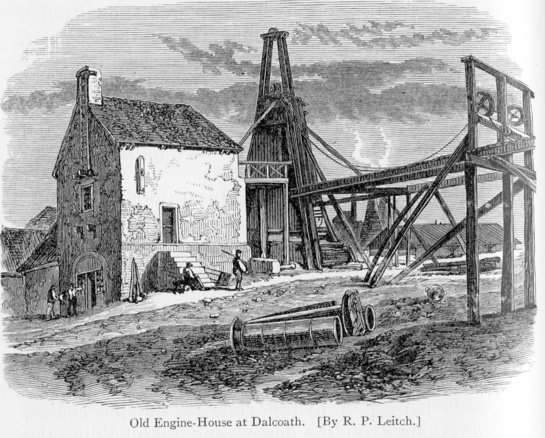

run out in heaps from the mine-heads. Engine-houses and

chimneys are the most prominent features in the landscape, and dot

the horizon as far as the eye can reach.

When Watt arrived at Chacewater he found the materials for

the Wheal Busy engine had come to hand, and that some progress had

been made with their erection. The materials for the Tingtang

engine, however, had not yet been received from Soho, and the owners

of the mine were becoming very impatient for it. Watt wrote to

his partner urging despatch, otherwise the engine might be thrown

upon their hands, especially if the Chacewater engine, now nearly

ready for work, did not give satisfaction.

From Watt's account, it would appear that the Cornish mines

were in a very bad way. "The Tingtang people," he said, "are

now fairly put out by water, and the works are quite at a stand."

The other mines in the neighbourhood were in no better plight.

The pumping-engines could not keep down the water. "Poldice

has grown worse than Wheal Virgin was: they have sunk £400 a month

for some months past, and £700 the last month; they will probably

soon give up. North Downs seems to be our next card."

The owners of the Wheal Virgin mine, though drowned out, like many

others, could not bring their minds to try Watt's engine. They

had no faith in it, and stuck to the old atmospheric of Newcomen.

They accordingly erected an additional engine of this kind to enable

them to go about eight fathoms deeper; "and they have bought," wrote

Watt, "an old boiler of monstrous size at the Briggin, which they

have offered £50 to get carried to its place."

At Chacewater, Watt first met Jonathan Hornblower, son of the

Joseph Hornblower who had come into Cornwall from Staffordshire,

some fifty years before, to erect one of the early Newcomen engines.

The son had followed in his father's steps, and become celebrated in

the Chacewater district as an engineer. It was natural that he

should regard with jealousy the patentees of the new engine; for if

it proved a success, his vocation as a maker of atmospheric engines

would be at an end. Watt thus referred to him in a letter to

Boulton: "Hornblower seems a very pleasant sort of old Presbyterian:

he carries himself very fair, though I hear that he is an

unbelieving Thomas." His unbelief strongly showed itself on

the starting of the Wheal Busy engine shortly after, when he

exclaimed, "Pshaw! she's but a bauble: I wouldn't give twopence

halfpenny for her."

There were others beside Hornblower who disliked and resented

what they considered the intrusion of Boulton and Watt into their

district, and who indeed never became wholly reconciled to the new

engine, though they were compelled to admit the inefficiency of the

old one. Among these was old Bonze, the engineer, a very

clever mechanic, who positively refused to undertake the erection of

the proposed new engine at Wheal Union if Boulton and Watt were to

be in any way concerned with it. But the mine-owners had to

study their own interests rather than the humour of their engineers,

and Watt secured the order for the Wheal Union engine. Several

other orders were promised, conditional on the performances of the

Wheal Busy engine proving satisfactory. "Ale and Cakes," [p.203]

wrote Watt, "must wait the result of Chacewater: several new engines

will be erected next year, for almost all the old mines are

exhausted, or have got to the full power of the present engines,

which are clumsy and nasty, the houses cracked, and everything

dropping with water from their cisterns."

Watt liked the people as little as he did their engines.

He thought them ungenerous, jealous, and treacherous.

"Certainly," said he, "they have the most ungracious manners of any

people I have ever yet been amongst." At the first monthly

meeting of the Wheal Virgin adventurers, which he attended, he found

a few gentlemen, but "the bulk of them would not be disgraced by

being classed with Wednesbury colliers." What annoyed him most

was, that the miners invented and propagated all sorts of rumours to

his prejudice. "We have been accused," said he, "of working

without leather upon our buckets, and making holes in the clacks in

order to deceive strangers. . . . I choose to keep out of their

company, as every word spoken by me would be bandied about and

misrepresented. I have already been accused of making several

speeches at Wheal Virgin, where, to the best of my memory, I have

only talked about eating, drinking, and the weather. The

greater part of the adventurers at Wheal Virgin are a mean dirty

pack, preying upon one another, and striving who shall impose most

upon the mine."

Watt was of too sensitive and shrinking a nature to feel

himself at home amongst such people. Besides, he was disposed

to be peevish and irritable, easily cast down, and ready to

anticipate the worst. It had been the same with him when

employed amongst the rough labourers on the Monkland Canal, where he

had declared himself as ready to face a loaded cannon as to

encounter the altercations of bargain-making. But Watt must

needs reconcile himself to his post as he best could; for none but

himself could see to the proper erection of the Wheal Busy engine,

and get it set to work with any chance of success.

A letter from Mrs. Watt to Mrs. Boulton, dated Chacewater,

September 1st, 1777, throws a little light on Watt's private life

during his stay in Cornwall. She describes the difficulty they

had in obtaining accommodation on their arrival, "no such thing as a

house or lodging to be had for any money within some miles of the

place where the engine was to be erected"; hence they had been glad

to accept of the hospitality of Mr. Wilson, the superintendent of

the mine.

"I scarcely know what to say to

you of the country. The spot we are at is the most

disagreeable in the whole county. The face of the earth is

broken up in ten thousand heaps of rubbish, and there is scarce a

tree to be seen. But don't think that all Cornwall is like

Chacewater. I have been at some places that are very pleasant,

nay beautiful. The sea-coast to me is charming, but not easy

to be got at. In some cases my poor husband has been obliged

to mount me behind him to go to some of the places we have been at.

I assure you I was not a little perplexed at first to be set on a

great tall horse with a high pillion. At one of our jaunts we

were only charged twopence apiece for our dinner. You may

guess what our fare would be from the cost of it; but I assure you I

never ate a dinner with more relish in my life, nor was I ever

happier at a feast than I was that day at Portreath. . . . One thing

I must tell you of is, to take care Mr. Boulton's principles

are well fixed before you trust him here. Poor Mr. Watt is

turned Anabaptist, and duly attends their meeting; he is indeed, and

goes to chapel most devoutly."

At last the Chacewater engine was finished and ready for

work. Great curiosity was felt about its performances, and

mining men and engineers came from all quarters to see it start.

"All the world are agape," said Watt, "to see what it can do."

It would not have displeased some of the spectators if it had

failed. But to their astonishment it succeeded. At

starting, it made eleven eight-feet strokes per minute; and it

worked with greater power, went more steadily, and "forked" more

water than any of the ordinary engines, with only about one-third

the consumption of coal. "We have had many spectators," wrote

Watt, "and several have already become converts. I understand

all the west-country captains are to be here to-morrow to see the

prodigy." Even Bonze, his rival, called to see it, and

promised not only to read his recantation as soon as convinced, but

never to touch a common engine again. "The velocity, violence,

magnitude, and horrible noise of the engine," Watt added,

"give universal satisfaction to all beholders, believers or not.

I have once or twice trimmed the engine to end its stroke gently,

and to make less noise; but Mr. Wilson cannot sleep unless it seems

quite furious, so I have left it to the engine-men; and, by the by,

the noise seems to convey great ideas of its power to the ignorant,

who seem to be no more taken with modest merit in an engine than in

a man." In a later letter he wrote, "The voice of the country

seems to be at present in our favour; and I hope will be much more

so when the engine gets on its whole load, which will be by Tuesday

next. So soon as that is done, I shall set out for home."

A number of orders for engines had come in at Soho during

Watt's absence; and it became necessary for him to return there as

speedily as possible, to prepare the plans and drawings, and put the

work in hand. No person had yet been attached to the concern

who was capable of relieving Watt of this portion of his duties;

while Boulton was fully occupied with conducting the commercial part

of the business. By the end of autumn Watt was again at home;

and for a week after his return he kept so close to his desk in his

house on Harper's Hill, that he could not even find time enough to

go out to Soho and see what had been doing in his absence. At

length he felt so exhausted by the brain-work and confinement that

he wrote to his partner, "A very little more of this hurrying and

vexation will knock me up altogether." To add to his troubles,

letters arrived from Tingtang, urging his return to Cornwall, to

erect the engine, the materials for which had at last arrived.

"I fancy," said Watt, "that I must be cut in pieces, and a portion

sent to every tribe in Israel."

After four months' labour of this sort, during which seven

out of the ten engines then in hand were finished and erected, and

the others well advanced, Watt again set out for Cornwall, which he

reached by the beginning of June, 1778. He took up his

residence at Redruth, as being more convenient for Tingtang than

Chacewater, hiring a house at Plengwarry, a hamlet on the outskirts

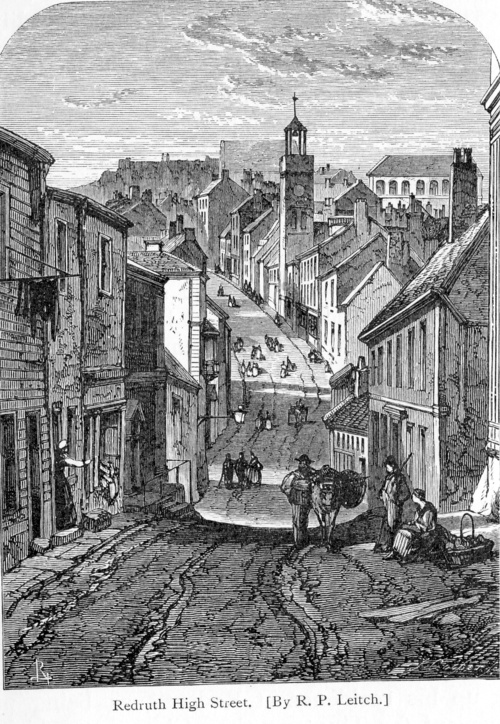

of the town. Redruth is the capital of the mining districts of

Camborne, Redruth, and Gwennap. It is an ancient town,

consisting for the most part of a long street, which runs down one

hill and up another.

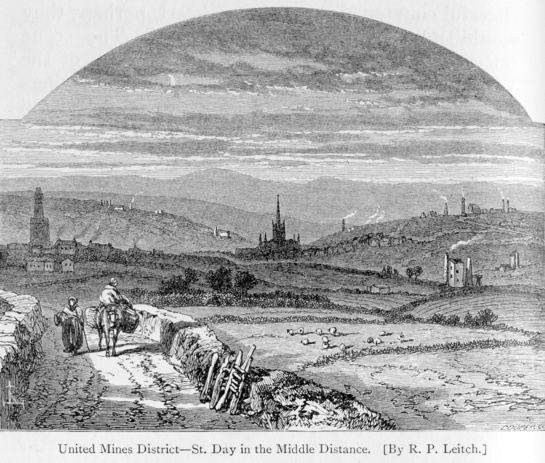

All round it the country seems to have been disembowelled;

and heaps of scoriæ, "deads," rubbish, and granite blocks cover the

surface. The view from the lofty eminence of Carn Brea, a

little to the south of Redruth, strikingly shows the scarified and

blasted character of the district, and affords a prospect the like

of which is seldom to be seen.

On making inquiry as to the materials which had arrived

during his absence, Watt was much mortified to find that the Soho

workmen had made many mistakes. "Forbes's eduction-pipe," he

wrote, "is a most vile job, and full of holes. The cylinder

they have cast for Chacewater is still worse, for it will hardly do

at all. The Soho people have sent here Chacewater

eduction-pipe instead of Wheal Union; and the gudgeon pipe has not

arrived with the nozzles. These repeated disappointments,"

said he, "will undoubtedly ruin our credit in the country; and I

cannot stay here to bear the shame of such failures of promise."

Watt had a hard time of it while in Cornwall, what with

riding and walking from mine to mine, listening to complaints of

delay in the arrival of the engines from Soho, and detecting and

remedying the blunders and bad workmanship of his mechanics.

Added to which, everybody was low-spirited and almost in despair at

the bad times,—ores falling in price, mines filled with water,

engine-men standing idle, and adventurers bemoaning their losses.

Another source of anxiety was the serious pecuniary

embarrassments in which the Soho firm had become involved.

Boulton had so many concerns going, that a vast capital was required

for the purpose of meeting current engagements; and the engine

business, instead of relieving him, had hitherto only proved a

source of additional outlay, and increased his difficulties at a

time of general commercial depression. He wrote to Watt,

urging him to send remittances for the Cornish engines but the

materials, though partly delivered, were not erected; and the miners

demurred to paying on account, until they were fixed complete, and

at work. Boulton then suggested to Watt that he should try to

obtain an advance from the Truro bankers, on security of the engine

materials. "No," replied Watt, "that cannot be done, as the

knowledge of our difficulties would damage our position in Cornwall,

and hurt our credit. Besides," said he, "no one can be more

cautious than a Cornish banker; and the principal partner of the

firm you name is himself exceedingly distressed for money."

Nor was there the least chance, in Watt's opinion, even if

they had the money to advance, of their accepting any security that

Boulton and Watt had to offer. "Such is the nature of the

people here," said he, "and so little faith have they in our engine,

that very few of them believe it to be materially better than the

ordinary one; and so far as I can judge, no one I have conversed

with would advance us £500 on a mortgage of it." [p.210]

All that Watt could do was to recommend that the evil day

should be staved off as long as possible, or at all events, until

the large engines he was then erecting were at work, when he

believed their performances would effect a complete change in the

views of the adventurers. The only suggestion he could offer

was to invite John Wilkinson, or some other moneyed man, to join

them as partner and relieve them of their difficulties; for "rather

than founder at sea," said he, "we had better run ashore."

Meanwhile, he urged Boulton to apply the pruning-knife and cut down

expenses, assuring him that he himself was practising all the

frugality in his power. But as Watt's personal expenses at the

time did not amount to £2 a week, it is clear that any savings he

could effect, however justifiable and laudable, were but as a drop

in the ocean compared with the liabilities to be met, and which must

be provided without delay to avoid insolvency and ruin.

Fothergill, Boulton's other partner, was even more desponding

than Watt. When Boulton left Soho on his journeys to raise

ways and means, Fothergill pursued him with dolorous letters,

telling of mails that had arrived without remittances, of bills that

must be met, of wages that must be paid on Saturday night, and of

the impending bankruptcy of the firm, which he again and again

declared to be "inevitable." "Better stop payment at once,"

said he, call our creditors together, and face the worst, than go on

in this neck-and-neck race with ruin." Boulton would then

hurry back to Soho, to quiet Fothergill, and keep the concern going;

on which another series of letters would pour in upon him from Mr.

Matthews, the London financial agent, pressing for remittances, and

reporting the increasingly gloomy and desperate state of affairs.

Boulton himself was, as usual, equal to the occasion.

His courage and determination rose in proportion to the difficulties

to be overcome. He was borne up by his invincible hope, by his

unswerving purpose, and above all by his unshaken belief in the

commercial value of the condensing engine. If they could only

weather the storm until its working powers could be fully

demonstrated, all would yet be well.

In illustration of his hopefulness, we may mention that in

the midst of his troubles a fire took place in the engine-room at

Soho, which was happily extinguished, but not before it had

destroyed the roof and done serious damage to the engine, which was

brought to a standstill. Boulton had long been desirous of

rebuilding the engine-house in a proper manner, but had been

hindered by Watt, who was satisfied merely with the alterations

necessary to accommodate the room to the changes made in the engine

called "Beelzebub." [p.212]

On hearing of the damage done by the fire, Boulton, instead of

lamenting over it, exclaimed, "Now I shall be able at last to have

the engine-house built as it should be."

After many negotiations, Boulton at length succeeded in

raising a sum of £7,000 by granting a Mr. Wiss security for the

payment of an annuity, while the London bankers, Lowe, Vere, and

Williams, allowed an advance of £14,000 on security of a mortgage

granted by Boulton and Watt on the royalties derived from the engine

patent, and of all their rights and privileges therein. Though

the credit of the house was thus saved, the liabilities of Boulton

and his partners continued to press heavily upon them for a long

time to come.

Meanwhile, however, a gleam of light came from Cornwall.

Watt sent the good news to Soho that "both Chacewater and Tingtang

engines go on exceedingly well, and give great satisfaction.

Chacewater goes 14 strokes of 9 foot long per minute, and burns

about 128 bushels per 24 hours. The water has sunk 12 fathoms

in the mine, and the engine will fork [i.e. pump out] the

first lift this night. No cross nor accident of any note has

happened, except the bursting of a pump at Tingtang, which was soon

repaired." Four days later Watt wrote, "The engines are both

going very well, and Chacewater has got the water down 18½ fathoms;

but after this depth it must make slower progress, as a very large

house of water begins there, and the feeders grow stronger as we go

deeper."

Watt looked upon the Chacewater trial as the experimentum

crucis, and continued to keep his partner duly informed of every

circumstance connected with it. "They say," he wrote, "that if

the new engine can fork the water from Chacewater, it can fork

anything, as that is the heaviest to fork in the whole county."

On the 15th of August he wrote, "Chacewater is now down to 10

fathoms of the second lift, and works steady and well; it sinks 9

feet per day. Chacewater people in high spirits: Captain Mayor

furiously in love with the engine." On the 29th he wrote

again, "Chacewater engine is our capital card, for should it succeed

in forking this mine, all doubts will then be removed." The

adventurers of the great Poldice mine watched the operations at

Chacewater with much interest. Two Newcomen engines, pumping

night and day for months, had failed to clear their mine of water;

and now they thought of ordering one of the new engines to take

their place; "but all this," said Watt, "depends on the success of

Chacewater, which God protect: it is now down 311 fathoms, and will

be in fork of this lift to-morrow, when it is to be put down three

fathoms lower and fixed there." On the 17th he wrote, "I have

been at Chacewater today, where they are in fork of the second lift

341 fathoms. The great connexion-rod still unbalanced.

The engine went yesterday 14 strokes per minute. To-morrow I

go to Wheal Union, and on Saturday to Truro, to meet Poldice

adventurers. . . . By attending to the business of this county

alone," said he, "we may at least live comfortably; for I cannot

suppose that less than twelve engines will be wanted in two or three

years, but after that very few more, as these will be sufficient to

get ore enough; though you cannot reckon the average profits to us

at above £200 per engine."

When Boulton and Watt first begun the manufacture of

steam-engines, they were mainly concerned to get orders, and were

not very particular as to the terms on which they were obtained.

But when the orders increased, and the merits of the invention

gradually became recognised, they found it necessary to require

preliminary agreements to be entered into as to the terms on which

the engine was to be used. It occurred to them, that as one of

its principal merits consisted in the saving of fuel, it would be a

fair arrangement to take one-third of the value of such saving by

way of royalty, leaving the owners of the engines to take the

benefit of the remaining two-thirds. Nothing could be fairer

than the spirit of this arrangement, which, it will be seen, was of

even more advantage to the owners of the engines than to the

patentees themselves. The first Cornish engines were, however,

erected without any condition as to terms; and it was only after

they had proved their power by "forking" the water, and sending the

miners twenty fathoms deeper into the ground, that the question of

terms was raised. Watt proposed that agreements should be

entered into on the basis above indicated. But the Cornish men

did not see the use of agreements. They had paid for the

engines, which were theirs, and Boulton and Watt could not take them

away. Here was the beginning of a long series of altercations.

The miners could not do without the engine. It was admitted to

be of immense value to them, rendering many of their mines workable

that would otherwise have been valueless. But why should they

have to pay for the use of such an invention? This was

what they never could clearly understand.

To prevent misunderstandings in future, Watt wrote to

Boulton, recommending that no further orders for engines should be

taken unless the terms for using them were definitely settled

beforehand. "You must excuse me," he added, "when I tell you

that, for my part, I will not put pen to paper [i.e. make the

requisite drawings] on a new subject until that is done. Until

an engine is ordered, our power is greater than that of the Lord

Chancellor; as I believe even he cannot compel us to make one unless

we choose. Let our terms be moderate, and, if possible,

consolidated into money a priori, and it is certain we shall

get some money, enough to keep us out of jail,—in continual

apprehension of which I live at present." [p.216]

To meet the case, a form of agreement was drawn up and

required to be executed before any future engine was commenced.

It usually provided that an engine of certain given dimensions and

power was to be erected at the expense of the owners of the mine;

and that the patentees were to take as their recompense for the use

of their invention, one-third of the value of the fuel saved by it

compared with the consumption of the ordinary engine. It came

to be understood that the saving of fuel was to be estimated

according to the number of strokes made. To ascertain this,

Watt contrived an ingenious piece of clockwork, termed the Counter,

which, being attached to the main beam, accurately marked and

registered, under lock and key, the number of its vibrations.

Thus the work done was calculated, and the comparative saving of

fuel was ascertained.

Though the Cornish miners had been full of doubts as to the

successful working of Watt's engine, they could not dispute the

evidence of their senses after it had been erected and was fairly at

work. There it was, "forking water" as never [an] engine

before had been known to "fork." It had completely mastered

the water at Wheal Busy; and if it could send the workmen down that

mine, it could in like manner send them down elsewhere. Wheal

Virgin was on the point of stopping work, in which case some two

thousand persons would be thrown out of bread. Bonze's new

atmospheric engine had proved a failure, and the mine continued

flooded. It had also failed at Poldice, which was drowned out.

"Notwithstanding the violence and prejudice against us," wrote Watt,

"nothing can save the mines but our engines. . .. Even the

infidels of Dalcoath are now obliquely inquiring after our

terms! Cook's Kitchen, which communicates with it, has been

drowned out some time."

Watt, accordingly, had many applications about engines; and

on that account he entreated his partner to come to his help.

He continued to hate all negotiating about terms, and it did not

seem as if he would ever learn to like it. He had neither the

patience to endure, nor the business tact to conduct a negotiation.

He wanted confidence in himself, and did not feel equal to make a

bargain. He would almost as soon have wrestled with the

Cornish miners as higgled with them. They were shrewd,

practical men, rough in manner and speech, yet honest withal; [p.217]

but Watt would not encounter them when he could avoid it.

Hence his repeated calls to Boulton to come and help him.

Writing to him about the proposed Wheal Virgin engine, he said,

"Before I make any bargain with these people, I must have you here."

A few days after, when communicating the probability of obtaining an

order for the Poldice engine, he wrote,—"I wish you would dispose

yourself for a journey here, and strike while this iron is hot."

A fortnight later he said, "Poldice people are now welding hot, and

must not be suffered to cool. They are exceedingly impatient,

as they lose £150 a month until our engine is going. . . . I hope

this will find you ready to come away. At Redruth, inquire for

Plengwarry Green, where you will find me."

Boulton must have been greatly harassed by the woes of his

partners. Fothergill was still uttering lamentable prophecies

of impending ruin; his only prospect of relief being in the success

of the steam-engine. He urged Boulton to endeavour to raise

money by the sale of engine contracts or annuities, in order to

avert a crash. Matthews, the London agent, also continued to

represent the still urgent danger of the house, and pressed Boulton

to go to Cornwall and try to raise money there upon his engine

contracts. Indeed, it was clear that the firm of Boulton and

Fothergill had been losing money by their business for several years

past; and that, unless the engine succeeded, they must, ere long, go

to the wall. When Boulton turned to Cornwall, he found little

comfort. Though the engines were successful, Watt could not

raise money upon them. The adventurers were poor,—were for the

most part losing by their ventures, in consequence of the low price

of the ore; and they almost invariably put off payment by excuses.

Thus, while Boulton was in London trying to obtain accommodation

from his bankers, the groans of his partner in Birmingham were more

than re-echoed by the lamentations of his other partner in Cornwall,

who rang the changes of misery through all the notes of the gamut.

At length, about the beginning of October, 1778, Boulton

contrived to make his long-promised journey into Cornwall. [p.219]

He went round among the mines, and had many friendly conferences

with the managers. He found the engine had grown in public

favour, and that the impression prevailed throughout the mining

districts that it would before long become generally adopted.

Encouraged by his London financial agent, he took steps to turn this

favourable impression to account. Before he left

Cornwall—where he remained until the end of the year,--he succeeded

in borrowing a sum of £2,000 from Elliot and Praed, the Truro

bankers, on security of the engines erected in the county; and the

money was at once forwarded to the London agents for the relief of

the firm. He also succeeded in getting the terms definitely

arranged for the use of several of the most important engines

erected and at work. It was agreed that £700 a year should be

paid as royalty in respect of the Chacewater engine,—an arrangement

even more advantageous to the owners of the mine than to the

patentees, as it was understood that the saving of coals amounted to

upwards of £2,400 a year. Other agreements were entered into

for the use of the engines erected at Wheal Union and Tingtang,

which brought in about £400 per annum more, so that the harvest of

profits seemed at length fairly begun.

Watt remained at Cornwall for another month, plodding at

Poldice and Wheal Virgin engines, and returned to Birmingham early

in January, 1779. Though the pumping-engine had thus far

proved remarkably successful, and accomplished all that Watt had

promised, he was in no better spirits than before. "Though we

have, in general, succeeded in our undertakings," he wrote to Dr.

Black, "yet that success has, from various unavoidable

circumstances, produced small profits to us; the struggles we have

had with natural difficulties, and with the ignorance, prejudices,

and villanies of mankind, have been very great, but I hope are now

nearly come to an end, or vanquished." [p.220-1]

His difficulties were not, however, nearly at an end, as the heavy

liabilities of the firm had still to be met. More money had to

be borrowed, and Watt continued to groan under his intolerable

burden. "The thought of the debt to Lowe, Vere, and Co.," he

wrote to his partner, "lies too heavy on my mind to leave me the

proper employment of my faculties in the prosecution of our

business; and, besides, common honesty will prevent me from loading

the scheme with debts which might be more than it could pay." [p.220-2]

A more hopeful man would have borne up under these

difficulties; for the reputation of the engine was increasing, and

orders were coming in from various quarters. Soho was full of

work; and, provided the credit of the firm could be maintained, it

was clear that the undertaking on which they had entered could not

fail to prove remunerative. Watt could not see this, but his

partner did; and Boulton accordingly strained every nerve to

maintain the character of the concern. While Watt was urging

upon him to curtail the business, Boulton sought in all ways to

extend it. He sent accounts of his marvellous engines abroad,

and orders for them came in from France and Holland. Watt was

more alarmed than gratified by the foreign orders, fearing that the

engine would be copied and extensively manufactured abroad, where

patents had not yet been secured. He did not see that the best

protection of all was in the superiority of his mechanics and tools,

enabling first-class work to be turned out,—advantages in which the

Soho firm had the start of the world. It is true his mechanics

were liable to be bribed, and foreigners were constantly haunting

Soho for the purpose of worming out the secrets of the manufacture,

and decoying away the best men. Against this, every precaution

was taken, though sometimes in vain. Two Prussian engineers

came over from Berlin in 1779, to whom Watt showed every attention;

after which, in his absence, they got into the engine-room, and

carefully examined all the details of "Old Bess," making notes.

When Watt returned, he was in high dudgeon, and wrote to his partner

that he "could not help it, unless by discountenancing every

foreigner who does not come avowedly to have an engine."

Their principal reliance, however, was necessarily on home

orders, and these came in satisfactorily. Eight more engines

were wanted for Cornwall,—those already at work continuing to give

satisfaction. Inquiries were also made about pumping-engines

for collieries in different parts of England. But where coals

were cheap, and the saving of fuel was of less consequence, the

patentees were not solicitous for orders unless the purchasers would

fix a fair sum for the patent right, or rate the coals used at a

price that would be remunerative in proportion to the savings

effected. The orders were, indeed, becoming so numerous, that

the firm, beginning to feel their power, themselves fixed the annual

royalty, though it was not always so easy to get it paid.

The working power of Watt was but limited. He still

continued to suffer from intense headaches; and, as all the drawings

of new engines were made by his own hands, it was necessary in some

measure to limit the amount of the work which was undertaken.

"I beg," he wrote to his partner in May, 1779, relative to proposals

made for two new engines, "that you will not undertake to do

anything for them before Christmas. It is, in fact,

impossible,—at least on my part; I am quite crushed." But he

was not always so dispirited, for in the following month we find him

writing to Boulton an exultant letter, announcing orders for three

new engines from Cornwall. [p.222]

Watt continued for some time longer to suffer great annoyance

from the shortcomings of his workmen. He was himself most

particular in giving his instructions, verbally, in writing, and in

drawings. When he sent a workman to erect an engine, he sent

with him a carefully drawn up detail of the step-by-step proceedings

he was to adopt in fitting the parts together. Where there was

a difficulty, and likely to be a hitch, he added a pen-and-ink

drawing, rapid but graphic, and pointed out how the difficulty was

to be avoided. It was not so easy, however, to find workmen

capable of intelligently fitting together the parts of a machine so

complicated and of so novel a construction. Moreover, the

first engines were in a great measure experimental, and to have

erected them perfectly, and provided by anticipation for their

various defects, would have involved a knowledge of the principles

of their construction almost as complete as that of Watt himself.

Nor was Watt sufficiently disposed to make allowances for the

workmen's want of knowledge and want of experience; and his letters

were accordingly full of complaints of their shortcomings. He

was especially annoyed with the mistakes of a foreman, named Hall,

who had sent the wrong articles to Cornwall, and he urged Boulton to

dismiss him at once. But Boulton knew better. Though

Watt understood engines, he did not so well understand men.

Had Boulton dismissed such men as Hall, because they made mistakes,

the shop would soon have been empty. The men were as yet but

at school, learning experience, and Boulton knew that in course of

time they would acquire dexterity. He was ready to make

allowance for their imperfections, but at the same time he did not

abate in his endeavours to find out and engage the best hands,

wherever they were to be found—in Wales, in Cornwall, or in

Scotland. He therefore kept on Hall, notwithstanding Watt's

protest, and the latter submitted. [p.224]

Watt was equally wroth with the enginemen at Bedworth.

"I beg and expect," he wrote to Boulton, "that so soon as everything

is done to that engine, you will instantly proceed to trial before

creditable witnesses, and if possible have the whole brood of these

enginemen displaced, if any others can be procured; for nothing but

slovenliness, if not malice, is to be expected of them." It

must, however, be acknowledged that the Bedworth engine was at first

very imperfect, having been made of bad iron, in consequence of

which it frequently broke down. In Cornwall the men were no

better. Dudley, Watt's erector at Wheal Chance and Hallamanin,

was pronounced incapable and a blunderer. "If something be not

very bad in London, I wish you would employ Hadley to finish those

engines, and send Joseph here to receive his instructions and

proceed to Cornwall, otherwise Dudley will ruin us."

The trusty "Joseph" was accordingly despatched to Cornwall to

look after Dudley, and remedy the defects in Wheal Chance and

Hallamanin engines; but when Watt arrived at Chacewater shortly

after, he found that Joseph, too, had proved faithless. He

wrote to Boulton, "Joseph has pursued his old practice of drinking

in a scandalous manner, until the very enginemen turned him into

ridicule. . . . I have not heard how he behaved in the west;

excepting that he gave the ale there a bad character."

Notwithstanding, however, his love of strong potations, Joseph was a

first-rate workman. Two days later Watt wrote, "Though Joseph

has attended to his drinking, he has done much good at his leisure

hours, and has certainly prevented much mischief at Hallamanin and

some at Wheal Union. He has had some hard and long jobs, and

consequently merits some indulgence for his foibles." By the

end of the month "Joseph had conquered Hallamanin engine, all but

the boiler," but Watt added, "His indulgence has brought on a slight

fit of the jaundice, and as soon as the engine is finished, he must

be sent home."

By this time Watt had called to his aid two other skilled

workmen, Law and Murdock, who arrived in Cornwall in the beginning

of September, 1779. In Watt's letters we find frequent

allusions to Murdock. Wherever any work had to be done

requiring more than ordinary attention, Watt specially directed that

"William" should be put to it. "Let William be sent for from

Bedworth," he wrote from Cornwall in 1778, "to set the patterns for

nozzles quite right for Poldice." Boulton wished to send him

into Scotland to erect the engine at Wenlockhead, but Watt would not

hear of it. "William" was the only man he could trust with the

nozzles. Then William was sent to London to take charge of the

Chelsea engine; next to Bedworth, to see to the completion of the

repairs previous to the final trial; then to Birmingham again to

attend to some further special instructions of Watt; and now we find

him in Cornwall, to take charge of the principal engines erecting

there.

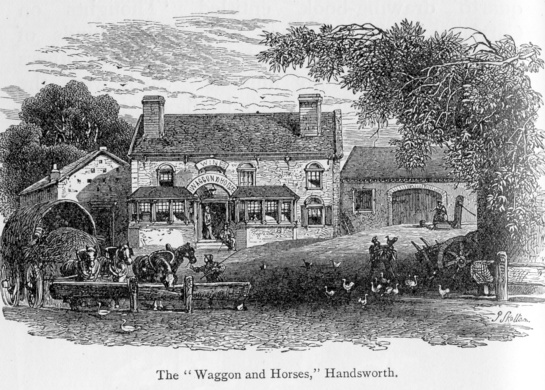

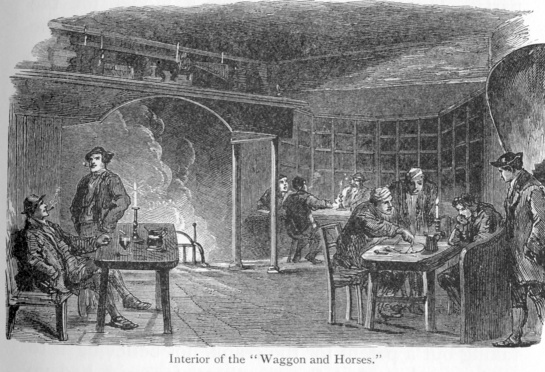

William Murdock was not only a most excellent and steady

workman, but a man of eminent mechanical genius. He was the

first maker of a model locomotive in this country; he was the

introducer of lighting by gas, and the inventor of many valuable

parts of the working steam-engine, hereafter to be described.

His father was a millwright and miller, at Bellow Mill, near Old

Cumnock, in Ayrshire, and was much esteemed for his probity and

industry, as well as for his mechanical skill. He was the

inventor of bevelled cast-iron gear for mills, and his son was proud

to exhibit, on the lawn in front of his house at Sycamore Hill,

Handsworth, a piece of the first work of the kind executed in

Britain. It was cast for him at Carron Ironworks, after the

pattern furnished by him, in 1766.

|

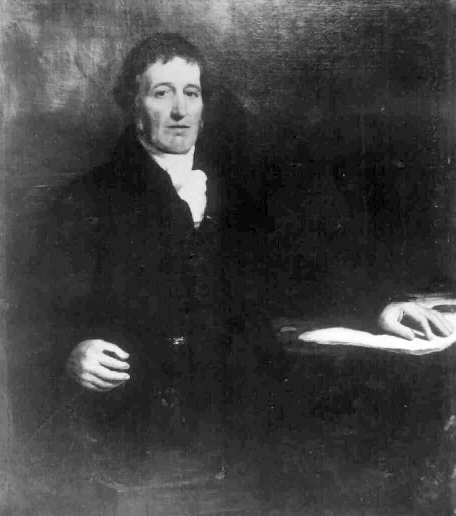

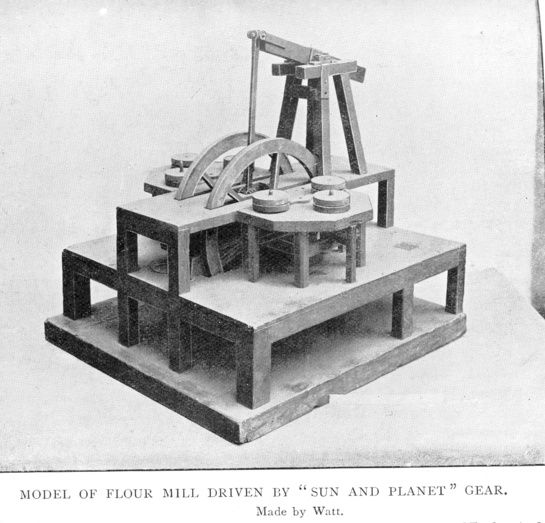

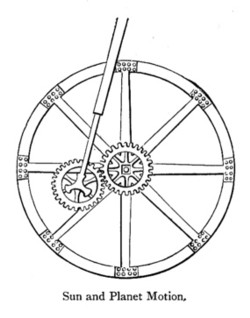

Ed.—William Murdock (1754-1839): Scottish engineer and

inventor (among other things,

of the "Sun and Planet" rotary motion and of gas lighting) later to become a partner

in the firm of Boulton and Watt.

From a portrait by John Graham Gilbert. Picture Wikipedia. |

William was born in 1754, and brought up to his father's

trade. On arriving at manhood, he became desirous of obtaining

a larger experience of millwork and mechanics than he could acquire

at his father's little mill. Hearing of the fame of Boulton

and Watt, and the success of their new engine, he determined to

travel south, and seek for a job at Soho. Many Scotchmen were

accustomed to call there on the same errand, probably relying on the

known clanship of their countrymen, and thinking that they would

find a friend and advocate in Watt. But, strange to say, Watt

did not think Scotchmen capable of becoming first-class mechanics. [p.226]

When Murdock called at Soho, in the year 1777, to ask for a

job, Watt was from home, but he saw Boulton, who was usually

accessible to callers of every rank. In answer to Murdock's

inquiry whether he could have a job, Boulton replied that work was

rather slack with them, and that every place was filled up.

During the brief conversation that ensued, the blate young

Scotchman, like most country lads in the presence of strangers, had

some difficulty in knowing what to do with his hands, and

unconsciously kept twirling his hat with them. Boulton's

attention was directed to the twirling hat, which seemed to be of a

peculiar make. It was not a felt hat, nor a cloth hat, nor a

glazed hat; but it seemed to be painted, and composed of some

unusual material. "That seems to be a curious sort of hat,"

said Boulton, looking at it more closely; "why, what is it made of?

" "Timmer, sir," said Murdock modestly. "Timmer?

Do you mean to say that it is made of wood?" "Yes, sir."

"Pray, how was it made?" "I turned it mysel', sir, in a

bit lathey of my own making." Boulton looked at the young man

again. He had risen a hundred degrees in his estimation.

He was tall, good-looking, and of open and ingenuous countenance;

and that he had been able to turn a wooden hat for himself in a

lathe of his own making was proof enough that he was a mechanic of

no mean skill. "You may call again, my man," said Boulton.

"Thank you, sir," said Murdock, giving a final twirl to his hat.

When Murdock called again, he was at once put upon a trial

job, after which he was entered as a regular hand. We learn

from Boulton's memorandum-book that he was engaged for two years, at

15s. a week when at home, 17s. when from home, and 18s. when in

London. Boulton's engagement of Murdock was amply justified by

the result. Beginning as a common mechanic, he applied himself

diligently and conscientiously to his work, and became trusted.

More responsible duties were confided to him, and he strove to

perform them to the best of his power. His industry and his

skilfulness soon marked him for promotion, and he rose from grade to

grade until he became Boulton and Watt's most trusted co-worker and

adviser in all their mechanical undertakings of importance.

When Murdock went into Cornwall to take charge of the

engines, he gave himself no rest until he had conquered their

defects and put them in thorough working order. He devoted

himself to his duties with a zeal and ability that completely won

Watt's heart. He was so filled with his work, that when he had

an important job in hand, he could scarcely sleep at nights for

thinking of it. When the engine at Wheal Union was ready for

starting, the people of the house at Redruth, in which Murdock

lodged, were greatly disturbed one night by a strange noise in his

room. Several heavy blows on the floor made them start from

their beds, thinking the house was coming down. They rushed to

Murdock's room, and there was he in his shirt, heaving away at the

bed-post in his sleep, calling out, "Now she goes, lads! now she

goes!"

Murdock was not less successful in making his is way with the

Cornishmen with whom he was brought into daily contact; indeed, he

fought his way to their affections. One day at Chacewater,

some half-dozen of the mining captains came into the engine-room and

began bullying him. This he could not stand, and adopted a

bold expedient. He locked the door and said, "Now, then, you

shall not leave this place until I have it fairly out with you."

He selected the biggest, and put himself in a fighting attitude.

The Cornishmen love fair play, and while the two engaged in battle,

the others, without interfering, looked on. The contest was

soon over; for Murdock was a tall, powerful fellow, and speedily

vanquished his opponent. The others, seeing the kind of man

they had to deal with, made overtures of reconciliation; and they

shook hands all round, and parted the best of friends. [p.229]

Watt continued to have his differences and altercations with

the Cornishmen, but he had no such way of settling them.

Indeed, he was almost helpless when he came in contact with rough

men of business. Most of the mines were then paying very

badly, and the adventurers raised all sorts of objections to making

the stipulated payment of the engine dues. Under such

circumstances, altercations with them took place for which Watt was

altogether unprepared. He was under the apprehension that they

were constantly laying their heads together for the purpose of

taking advantage of him and his partner. He never looked on

the bright side of things, but always on the darkest. "The

rascality of mankind," said he to Dr. Black, "is almost beyond

belief." Though his views of science were large, his views of

men were narrow. Much of this may have been the result of his

recluse habits and closet life, as well as of his constant

ill-health. With his racking headaches, it was indeed

difficult for him to be cheerful. But no one could be more

conscious of his own defects of his want of tact, his want of

business qualities, and his want of temper—than he was himself.

He knew his besetting infirmities, from which even the best and

wisest are not exempt. His greatness was mingled with

imperfections, and his strength with weakness. It is not in

the order of Providence that the gifts and graces of life should be

concentrated in any one perfectly adjusted character. Even

when we inquire into the "Admirable Crichton " of biography, and

seek to trace his life, it vanishes almost into a myth.

In the midst of his many troubles and difficulties, Watt's

invariable practice was to call upon Boulton for help. Boulton

was satisfied to take men as he found them, and try to make the best

of them. Watt was a man of the study; Boulton a man of the

world. Watt was a master of machines; but Boulton of men.

Though Watt might be the brain, Boulton was the heart of the

concern. "If you had been here," wrote Watt to Boulton, after

one of his disagreeable meetings with the adventurers, "If you had

been here, and gone to that meeting with your cheerful countenance

and brave heart, perhaps they would not have been so obstinate."

The scene referred to by Watt occurred at a meeting of the Wheal

Union Adventurers, at which the savings effected by the new engine

were to be calculated and settled.

In subsequent letters Watt continued to urge Boulton to come

to him. His headaches were constant, unfitting him for work.

Besides, he could scarcely stir out of doors for the rain. "It

rains here," said he, "prodigiously. When you come, bring with

you a waxed linen cloak for yourself, and another for me, as there

is no going out now for a few miles without getting wet to the skin.

When it rains in Cornwall, and it rains often, it rains solid!"

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XI.

FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES—BOULTON IN CORNWALL—ATTACK AND DEFENCE OF THE

ENGINE PATENT.

BOULTON again

went to Watt's help in Cornwall at the end of autumn, 1779. He

could not afford to make a long stay, but left as soon as he had

settled several long-pending agreements with the mine proprietors.

The partners returned to Birmingham together. Before leaving,

they installed Lieutenant Henderson as their representative, to

watch over their interests in their absence. Henderson was a

sort of Jack-of-all-trades and master of none. He had been an

officer of marines, and afterwards a West India sugar-planter.

He lost all that he possessed in Jamaica, but gained some knowledge

of levelling, draining, and machinery. He was also a bit of an

inventor, and first introduced himself to Boulton's notice by

offering to sell him a circular motion by steam which he alleged he

had discovered. This led to a correspondence, which resulted

in his engagement to travel for the firm, and to superintend the

erection of engines when necessary.

Henderson experienced the same difficulty that Watt had done

in managing the adventurers, and during his stay in Cornwall he was

never done calling upon Boulton to hasten to his assistance and help

him, as he said, "to put them in good spirits and good temper."

As the annual meetings drew near, Henderson anticipated a stormy

time of it, and pleaded harder than ever for Boulton to come to him.

It seemed as if it would be necessary for Boulton to take up his

residence in Cornwall; and as the interests at stake were great, it

might be worth his while to do so. By the summer of 1780,

Boulton and Watt had made and sold forty pumping-engines, of which

number twenty were erected and at work in different parts of

Cornwall; and it was generally expected that before long there would

scarcely be an engine of the old construction left at work in the

county. This was, in fact, the only branch of Boulton's

extensive concerns that promised to be remunerative. [p.233]

He had become loaded with a burden of debt, from which the success

of the engine business seemed to offer the only prospect of relief.

Boulton's affairs were fast approaching to a crisis. He

had raised money in all directions to carry on his extensive

concerns. He had sold the Patkington estate, which came to him

by his wife, to Lord Donegal, for £15,000; he had sold the greater

part of his father's property, and raised further sums by mortgaging

the remainder; he had borrowed largely from Day, Wedgwood, and

others of his personal friends, and obtained heavy advances from his

bankers; but all this was found insufficient, and his embarrassment

seemed only to increase. Watt could do nothing to help him

with money, though he had consented to the mortgage of the

steam-engine royalties to Mr. Wiss, by which the sum of £7,000 had

been raised. This liability lay heavy on the mind of Watt, who

could never shake himself free of the horror of having incurred such

a debt; and many were the imploring letters that he addressed to

Boulton on the subject. "I beg of you," said he, "to attend to

these money affairs. I cannot rest in my bed until they [i.e.

the mortgage and bankers' advance] have assumed some determinate

form. I beg you will pardon my importunity, but I cannot bear

the uneasiness of my own mind, and it is as much your interest as

mine to have them settled."

The other partner, Fothergill, was quite as downhearted.

He urged that the firm of Boulton and Fothergill should at once stop

payment and wind up; but as this would have seriously hurt the

credit of the engine firm, Boulton would not listen to the

suggestion. They must hold on as they had done before, until

better days came round. Fothergill recommended that at least

the unremunerative branches of the business should be brought to a

close. The heaviest losses had indeed been sustained through

Fothergill himself, whose foreign connexions, instead of being of

advantage to the firm, had proved the reverse; and Mr. Matthews, the

London agent, repeatedly pressed Boulton to decline further

transactions with foreigners.

There was one branch of the Boulton and Fothergill business

which Boulton at once agreed to give up. This was the painting

and japanning business; by which, as appears from a statement

prepared by Mr. Walker, now before us, the firm were losing at the

rate of £500 a year.

The picture-painting business seems to have been begun in

1777, and was carried on for a few years under the direction of Mr.

Eginton, who afterwards achieved considerable reputation at

Birmingham as a manufacturer of painted glass. A degree of

interest has been recently raised on the subject of the Soho

pictures, in consequence of the statements made as to the method by

which they are supposed to have been produced. It has been

surmised that they were taken by some process resembling

photography. We have, however, been unable to find anything in

the correspondence of the firm calculated to support this view.

On the contrary, they are invariably spoken of as "mechanical

paintings," "pictures," or "prints," produced by means of "paints"

or "colours." Though the precise process by which they were

produced is not now known, there seems reason to believe that they

were impressions from plates prepared in a peculiar manner.

The impressions were taken "mechanically" on paper; and both oil and

water colours [p.236]

were made use of. Some of the pictures were of large size 40

by 50 inches—the subjects being chiefly classical. This branch

of the business being found unproductive, was brought to a close in

1780, when the partnership with Eginton was at the same time

dissolved.

Another, but more fortunate branch of business into which

Boulton entered with Watt and Keir, about the same time, was the

manufacture of letter-copying machines. Watt made the

invention, Boulton found the money for taking out the patent, and

Keir conducted the business. Watt was a very voluminous

correspondent, and the time occupied by him in copying letters, the

contents of which he desired to keep secret from third parties, was

such that in order to economise it he invented the method of

letter-copying now in common use. The invention consisted in

the transfer, by pressure, of the writing made with mucilaginous

ink, to damp an unsized transparent copying-paper, by means either

of a rolling press or a screw press. Though Watt himself

preferred the rollers, the screw press is now generally adopted as

the more simple and efficacious process.

This invention was made by Watt in the summer of 1778.

In June we find him busy experimenting on copying-papers of

different kinds, requesting Boulton to send him specimens of "the

most even and whitest unsized paper"; and in the following month he

wrote to Dr. Black, "I have lately discovered a method of copying

writing instantaneously, provided it has been written the same day,

or within twenty-four hours. I send you a specimen, and will

impart the secret if it will be of any use to you. It enables

me to copy all my business letters." [p.237]

For two years Watt kept his method of copying a secret; but

hearing that certain persons were prying into it with the view of

turning it to account, he determined to anticipate them by taking

out a patent, which was secured in May, 1780. By that time

Watt had completed the details of the press and the copying-ink.

Sufficient mahogany and lignum-vitae had been ordered for making 500

machines, and Boulton went up to London to try and get the press

introduced in the public offices.

He first waited upon several noblemen to interest them in the

machine, amongst others on Lord Dartmouth, who proposed to show it

to George III. The King said Boulton, in a letter to Watt,

"writes a great deal, and takes copies of all he writes with his own

hand, so that Lord Dartmouth thinks it will be a very desirable

thing for His Majesty." Several of those to whom the machine

was first shown, apprehended that it would lead to increase of

forgery—then a great source of terror to commercial men. The

bankers concurred in this view, and strongly denounced the

invention; and they expostulated with Boulton and Watt's agent for

offering the presses for sale. "Mr. Woodmason," wrote Boulton,

"says the bankers mob him for having anything to do with it; they

say that it ought to be suppressed."

Boulton was not dismayed by this opposition, but proceeded to

issue circulars to the members of the Houses of Lords and Commons,

descriptive of the machine, inviting them to an inspection of it,

after which he communicated the results to his partner:—

. . . . "On Tuesday morning last I waited on some

particular noblemen, according to promise, at their own houses, with

the press, and at one o'clock I took possession of a private room

adjoining the Court of Requests, Westminster Hall, where I was

visited by several members of both Houses, who in general were well

pleased with the invention; but all expressed their fears of

forgery, which occasioned and obliged me to exercise my lungs very

much. Many of the members tried to copy bank notes, but in

vain. . . .

"On Thursday . . . . at half-past two . . . . I had a

tolerable good House, even a better than the Speaker, who was often

obliged to send his proper officer to fetch away from me the members

to vote, and sometimes to make a House. As soon as the House

formed into a Committee upon the Malt Tax, the Speaker left the

chair and sent for me and the machine, which was carried through the

gallery in face of the whole House into the Speaker's Chamber. . . .

Mr. Banks came to see the machine on Thursday. I thought it

might be of service to show it to the Royal Society that evening . .

. . After the business of the Society was over, he announced Mr.

Watt's invention and my readiness to show it, and it was accordingly

brought in and afforded much satisfaction to a crowded audience . .

. . I spent Friday evening with Smeaton and other engineers at a

coffee-house, when a gentleman (not knowing me) exclaimed against

the copying-machine, and wished [the inventor was hanged] and the

machines all burnt, which brought on a laugh, as I was known to most

present." [p.238]

By the end of the year, the 150 machines first made were sold

off, and more orders were coming in. Thirty were wanted for

exportation abroad, and a still great number were wanted at home.

The letter-copying machine gradually and steadily made its way,

until at length there was scarcely a house of any extensive business

transactions in which it was not to be found. Watt himself,

writing of the invention some thirty years later, observed that it

had proved so useful to himself, that it would have been worth all

the trouble of inventing it, even had it been attended with no

pecuniary profit whatever.

Boulton's principal business, however, while in town, was not

so much to push the letter-copying machine, but to set straight the

bankers' account, which had been over-drawn to the amount of

£17,000. He was able to satisfy them to a certain extent by

granting mortgages on the engine royalties payable in Cornwall,

besides giving personal bonds for repayment of the advances within a

given time. It was necessary to obtain Watt's consent to both

these measures; but, though Watt was willing to agree to the former

expedient, he positively refused to be a party to the personal

bonds.

Boulton was therefore under the necessity of arranging the

matter himself. He was enabled to meet the more pressing

claims upon the firm, and to make arrangements for pushing on the

engine business with renewed vigour. Watt was, however, by no

means so anxious on this score as Boulton was. He was even

desirous of retiring from the concern, and going abroad in search of

health. "Without I can spare time this next summer," he wrote,

"to go to some more healthy climate to procure a little health, if

climate will do, I must give up business and the world too. My

head is good for nothing."

While Boulton was earnestly pressing the invention on the

mining interest, and pushing for orders, Watt shuddered at the

prospect of any further work. He saw in increase of business

only increase of headaches. "The care and attention which our

business requires," said he, "make me at present dread a fresh order

with as much horror as other people with joy receive one. What

signifies it to a man though he gain the whole world, if he lose his

health and his life? The first of these losses has already

befallen me, and the second will probably be the consequence of it,

unless some favourable circumstances, which at present I cannot

foresee, should prevent it."

Judging by the correspondence of Watt at this time, his

sufferings of mind and body must have been excessive; and the wonder

is how he lived through it all. But "the creaking gate hangs

long on its hinges," and Watt lived to the age of eighty-three, long

surviving his stronger and more courageous partner. Intense

headache seemed to be his normal state, and his only tolerable

moments were those in which the headache was less violent than

usual.

His son has since described how he remembered seeing his

father about this time, sitting by the fireside for hours together,

with his head leaning on his elbow, suffering from most acute

sick-headaches, and scarcely able to give utterance to his thoughts.

"My headache," he would write to Boulton, "keeps its week-aversary

to-day." At another time, "I am plagued with the blues; my

head is too much confused to do any brain-work." Once, when he had

engaged to accompany his wife to an evening concert, he wrote, "I am

quite eat up with the mulligrubs, and to complete the matter I am

obliged to go to an oratorio, or serenata, or some other nonsense,

to-night."

Mrs. Watt tried her best to draw him out of himself, but it

was not often that she could divert him from his misery. What

relieved him most was sleep, when he could obtain it; and, to

recruit his powers, he was accustomed to take from nine to eleven

hours' sleep at night, besides naps during the day. When

Boulton had erysipelas, in Cornwall, and could not stir abroad, he

wrote to his partner complaining of an unusual lowness of spirits,

on which Watt undertook to be his comforter in his own peculiar way.

"There is no pitch of low spirits," said he, "that I have not a

perfect notion of, from hanging melancholy to peevish melancholy.

You must conquer the devil when he is young."

Watt experienced all the tortures of confirmed dyspepsia,

which cast its dark shadow over the life of every day. His

condition was often most pitiable. It is true, many of the

troubles which beset him were imaginary, but he suffered from them

in idea as much as if they had been real. Small evils fretted

him, and great ones overwhelmed him. He met them all more than

halfway; and usually anticipated the worst. He had few moments

of cheerfulness, hopefulness, or repose. Speaking of one of

his violent headaches, he said, "I believe it was caused by

something making my stomach very acid;" and unhappily, as in the

case of most dyspeptics, the acidity communicated itself to his

temper. When these fits came upon him, and the world was going

against him, and ruin seemed about to swallow him up quick, he would

sit down and pen a long gloomy letter to his partner, full of agony

and despair. His mental condition showed at what expense of

suffering in mind and body the triumphs of genius are sometimes

achieved.

In the autumn of 1780, Boulton went into Cornwall for a time

to look after the business there. Several new engines had been

ordered, and were either erected or in progress, at Wheal Treasury,

Tresavean, Penrydee, Dalcoath, Wheal Chance, Wheal Crenver, and the

United Mines. One of the principal objects of his visit was to

settle the agreements with the mining companies for the use of these

engines.

It had been found difficult to estimate the actual savings of

fuel, and the settlement of the accounts was a constant source of

cavil. There was so much temptation on the one side to evade

the payments according to the tables prepared by Watt, and so much

occasion for suspicion on the other that they had been evaded by

unfair means, that it appeared to Boulton that the only practicable

method was to agree to a fixed annual payment for each engine

erected, according to its power and the work it performed.

Watt was very averse to giving up the tables which had cost

him so much labour to prepare; but Boulton more wisely urged the

adoption of the plan that would work most smoothly, and get rid of

the heart-burnings on both sides. Boulton accordingly sent

down to Watt a draft agreement with the Wheal Virgin adventurers,

who were prepared to pay the large sum of £2,500 a year in respect

of five new engines erected for their firm; and urged him to agree

to the terms. "You must not be too rigid," said he, "in fixing

the dates of payment. A hard bargain is a bad bargain."

Watt replied in a long letter, urging the accuracy of his

tables, and intimating his reluctance to depart from them. To

this Boulton responded, "Now, my dear Sir, the way to do justice to

our own characters, and to trample under our feet envy, hatred, and

malice, is to dispel the doubts, and to clear up the minds of the

gentlemanly part of this our best of all kingdoms; for if they think

we do wrong, it operates against us although we do none, just as

much as if we really did the wrong. Patience and candour

should mark all our actions, as well as firmness in being just to

ourselves and others. A fair character and standing with the

people is attended with great advantage as well as satisfaction, of

which you are fully sensible, so I need say no more."

Watt did not give up his favourite tables without further

expostulation and argument, but at length he reluctantly gave his

assent to the Wheal Virgin agreement, by which the annual payment of

£2,500 was secured. This was really an excellent bargain,

though Watt seemed to regard it in the light of a calamity. In

the letter intimating his reluctant concurrence, he observed: "These

disputes are so very disagreeable to me, that I am very sorry I ever

bestowed so great a part of my time and money on the steam-engine.

I can bear with the artifices of the designing part of mankind, but

having myself no intention to deceive others, I cannot brook the

suspicions of the honest part, which I am conscious I never merited

even in intention, far less by any actual attempt to deceive."

Two days later Watt again wrote, urging the superiority of

his tables, concluding thus: "I have been so much molested with

headaches this week, that I have perhaps written in a more peevish

strain than I should have done if I had been in better health, which

I hope you will excuse." Boulton replied, expressing regret at

his lowness of spirits and bad health, and advising him to cheer up.

"At your leisure," said he, "you may amuse yourself with a

calculation of what all the engines we shall have in eighteen months

erected in Cornwall will amount to; you will find it good for low

spirits."

"I assure you," he said at another time, "you have no cause

for apprehension as to anything in this country; all is going on

well." Boulton seemed to regard his partner in the light of a

permanent invalid, which he was; and on writing to his various

correspondents on matters of business at Soho, he would adjure them

"not to cross Mr. Watt." To Fothergill he wrote respecting the

execution of an order: "the matter," he said, "must be managed with

some delicacy respecting Mr. Watt, as you know that when he is

low-spirited he is vexed at trifles."

Another important part of Boulton's business in Cornwall,

besides settling the engine agreement, was to watch the mining

adventures themselves, in which by this time Boulton and Watt had

become largely interested. In the then depressed state of the

mining interest, it was in many cases found difficult to raise the

requisite money to pay for the new engines; and the engineers must

either go without orders or become shareholders to prevent the

undertakings dropping through altogether. Watt's caution

impelled him at first to decline entering into such speculations.

He was already in despair at what he considered the bad fortunes of

the firm, and the load of debts they had incurred in carrying on the

manufacture of engines. But there seemed to be no alternative,

and he at length came to the conclusion with Boulton, that it was

better "not to lose a sheep for a ha'porth of tar."

Rather than lose the orders, therefore, or risk the losses

involved by the closing of the mines worked by their engines, the

partners resolved to incur the risk of joining in the adventures;

and in course of time they became largely interested in them.

They also induced friends in the North to join them, more

particularly Josiah Wedgwood and John Wilkinson, who took shares to

a considerable amount.

Boulton now made it his business to attend the meetings of

the adventurers, in the hope of improving their working

arrangements, which he believed were very imperfect. He became

convinced of this, after his first meeting with the adventurers of

the Wheal Virgin mine. He found their proceedings conducted

without regard to order. The principal attention was paid to

the dining, and after dinner and drink little real business could be

done. No minutes were made of the proceedings; half the

company were talking at the same time on different subjects; no one

took the lead in conducting the discussions, which were disorderly

and anarchical in the extreme.

Boulton immediately addressed himself to the work of

introducing order and despatch. He called upon his brother

adventurers to do their business first, and talk and drink

afterwards. He advised them to procure a minute-book in which

to enter the resolutions and proceedings. His clear-headed

suggestions were at once agreed to; and the next meeting, for which

he prepared the agenda, was so entirely different from all that had

preceded it, in respect of order, regularity, and business

transacted, that his influence with the adventurers was at once

established. "The business," he wrote to Watt, "was conducted

with more regularity, and more of it was done, than was ever known

at any previous meeting." He perceived, however, that there

was still room for great improvements, and added, "Somebody must be

here all next summer . . . I shall be here myself the greater part

of it, for there will want more kicking than you can do. . . .

Grace au Dieu! I neither want health, nor spirits, nor

even flesh, for I grow fat."

To increase his influence among the adventurers, and secure

the advantages of a local habitation among them, Boulton deemed it

necessary to take a mansion capable of accommodating his family, and

which should serve the same purpose for his partner when sojourning

in the neighbourhood. Boulton's first idea was to have a

portable wooden house built and fitted up in the manner of a ship's

cabin, which might readily be taken to pieces and moved from place

to place as business required. This plan was, however,

eventually abandoned in favour of a residence of a more fixed kind.

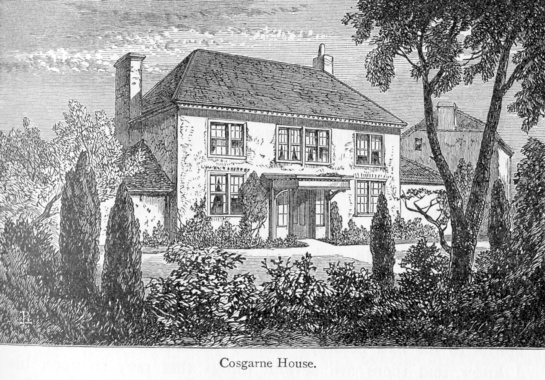

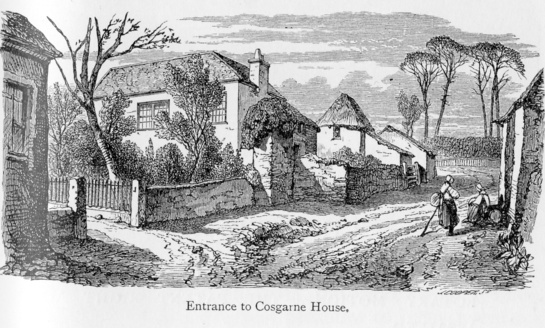

After much searching, a house was found which promised to answer the

intended purpose,—an old-fashioned, roomy mansion, with a good-sized

garden full of fruit-trees, prettily situated at Cosgarne, in the

Gwennap valley. Though the United Mines district was close at

hand, and fourteen of Boulton and Watt's engines were at work in the

immediate neighbourhood, not an engine chimney was to be seen from

the house, which overlooked Tresamble Common, then an unenclosed

moor. Here the partners by turns spent much of their time for

several successive years, travelling about on horseback, from mine

to mine, to superintend the erection and working of the engines.

By this time the old Newcomen engines had been almost

completely superseded, only one of that construction remaining at

work in the whole county of Cornwall. The prospects of the

engine business were, indeed, so promising that Boulton even

contemplated retiring altogether from his other branches of business

at Soho, and settling himself permanently in Cornwall. [p.247]

Notwithstanding the great demand for engines, the firm

continued in serious straits for money, and Boulton was under the

necessity of resorting to all manner of expedients to raise it,

sometimes with Watt's concurrence, but oftener without. Watt's

inexperience in money matters, conjoined with his extreme timidity

and nervousness, made him apprehend ruin and bankruptcy from every

fresh proposition made to him on the subject of raising money.

He was kept so utterly wretched by his fears as to be on many

occasions quite unmanned, and he would brood for days together on

the accumulation of misery and anxiety which his great invention had

brought upon him. His wife was kept almost as miserable as

himself, and as Matthew Boulton was the only person, in her opinion,

who could help him out of his troubles, Mrs. Watt privately appealed

to him in the most pathetic terms:—

"I know," she wrote, "the goodness

of your heart will readily forgive me for this freedom, and your

friendship for Mr. Watt will, I am sure, excuse me for pointing out

a few things that press upon his mind. I am very sorry to tell

you that both his health and spirits have been much worse since you

left Soho. It is all that I can do to keep him from sinking

under that fatal depression. Whether the badness of his health

is owing to the lowness of his spirits, or the lowness of his