|

[Previous Page]

BOULTON AND WATT.

ENGINEERS, BIRMINGHAM.

―――♦―――

CHAPTER VI.

BIRMINGHAM-MATTHEW BOULTON.

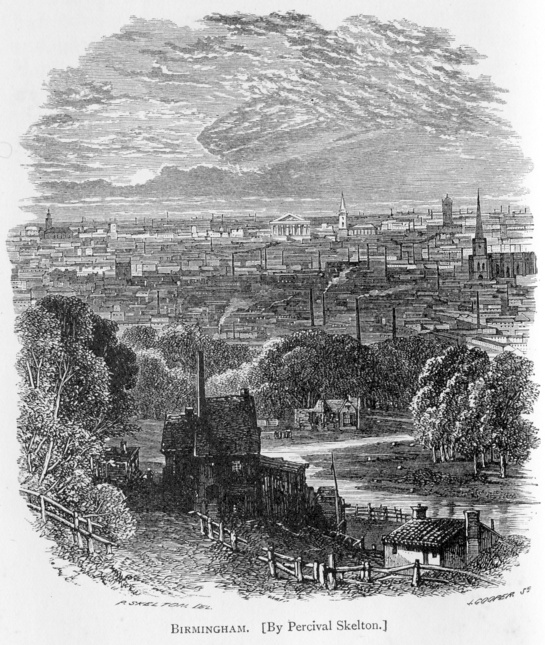

FROM an early

period Birmingham has been one of the principal centres of

mechanical industry in England. The neighbourhood abounds in

coal and iron, and has long been famous for the skill of its

artisans. Swords were forged there in the middle ages.

The first guns made in England bore the Birmingham mark. In

1538 Leland found "many smiths in the town that use to make knives

and all manner of cutting tools, and many loriners that makes bittes,

and a great many nailers." About a century later Camden

described the place as "full of inhabitants, and resounding with

hammers and anvils, for the most part of them smiths." As the

skill of the Birmingham artisans increased, they gradually gave up

the commoner kinds of smithery, and devoted themselves to ornamental

metal-work, in brass, steel, and iron. They became celebrated

for their manufacture of buckles, buttons, and various fancy

articles; and they turned out such abundance of toys that towards

the close of last century Burke characterised Birmingham as "the

great toy-shop of Europe."

The ancient industry of Birmingham was of a more staid, and

steady character, in keeping with the age. Each manufacturer

kept within the warmth of his own forge. He did not go in

search of orders, but waited for the orders to come to him.

Ironmongers brought their money in their saddle-bags, took away the

goods in exchange, or saw them packed ready for the next waggon

before they left. Notwithstanding this quiet way of doing

business, many comfortable fortunes were made in the place; the

manufacturers, like their buttons, moving off so soon as they had

received the stamp and the gilt. Hutton, the Birmingham

bookseller, says he knew men who left the town in chariots who had

first approached it on foot. Hutton himself entered the town a

poor boy, and lived to write its history, and make a fortune by his

industry.

Until towards the end of last century the town was not very

easy of approach from any direction. The roads leading to it

had become worn by the traffic of many generations. The hoofs

of the packhorses, helped by the rains, had deepened the tracks in

the sandy soil, until in many places they were twelve or fourteen

feet deep, so that it was said of travellers that they approached

the town by sap. One of these old hollow roads, still called

Holloway-head, though now filled up, was so deep that a waggon-load

of hay might pass along it without being seen. There was no

direct communication between Birmingham and London until about the

middle of the century. Before then the Great Road from London

to Chester passed it four miles off, and the Birmingham

manufacturer, when sending wares to London, had to forward his

package to Castle Bromwich, there to await the approach of the

packhorse train or the stage-waggon journeying south. The

Birmingham men, however, began to waken up, and in 1747 a coach was

advertised to run to London in two days, "if the roads permit."

Twenty years later a stage-waggon was put on, and the communication

by coach became gradually improved.

When Hutton entered Birmingham in 1740, he was struck by the

activity of the place and the vivacity of the inhabitants, which

expressed itself in their looks as he passed them in the streets.

"I had," he says, "been among dreamers, but now I saw men awake.

Their very step showed alacrity. Every man seemed to know and

to prosecute his own affairs." The Birmingham men were indeed

as alert as they looked—steady workers and clever mechanics—men who

struck hard on the anvil. The artisans of the place had the

advantage of a long training in mechanical skill. It had been

bred in their bone, and descended to them from their fathers as an

inheritance. In no town in England were there then to be found

so many mechanics capable of executing entirely new work; nor,

indeed, has the ability yet departed from them, the Birmingham

artisans maintaining their individual superiority in intelligent

execution of skilled work to the present day. We are informed

that inventors of new machines, foreign as well as English, are

still in the practice of resorting to them for the purpose of

getting their inventions embodied in the best forms, with greater

chances of success than in any other town in England.

About the middle of last century the two Boultons, father and

son, were recognised as among the most enterprising and prosperous

of Birmingham manufacturers. The father of the elder Matthew

Boulton was John Boulton of Northamptonshire, in which county

Boultons or Boltons had long been settled. About the end of

the seventeenth century John Boulton lived at Lichfield, where he

married Elizabeth, heir of Matthew Dyott of Stitchbrooke, by whom he

obtained considerable property. His means must, however, have

become reduced; in consequence of which his son Matthew was sent to

Birmingham to enter upon a career of business, and make his own way

in the world. He became established in the town as a silver

stamper and piecer, to which he added other branches of manufacture,

which his son Matthew afterwards largely extended.

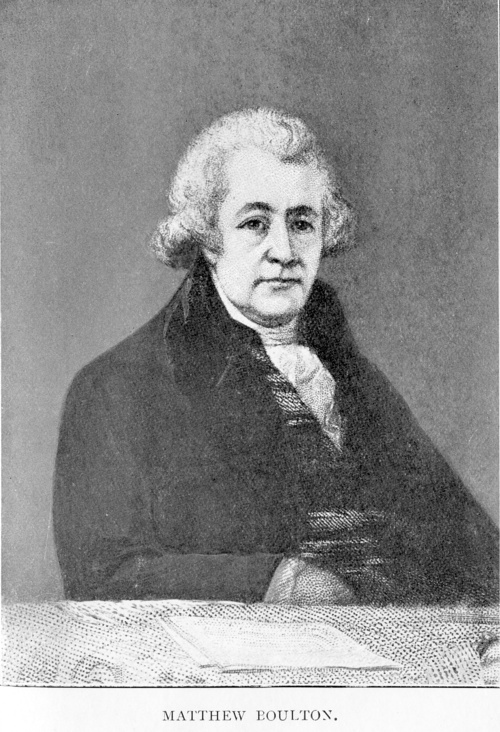

Matthew Boulton the younger was born at Birmingham on the 3rd

September, 1728. Little is known of his early life, beyond

that he was a bright, clever boy, and a general favourite with his

companions. He received his principal education at a private

academy at Deritend, kept by the Rev. Mr. Ansted, under whom he

acquired the rudiments of a good English education. Though he

left school early, for the purpose of following his father's

business, he nevertheless continued the work of self-instruction,

and afterwards acquired considerable knowledge of Latin and French,

as well as of drawing and mathematics.

Young Boulton appears to have engaged in business with much

spirit. By the time he was seventeen he had introduced several

important improvements in the manufacture of buttons, watch-chains,

and other trinkets; and he had invented the inlaid steel buckles

which shortly after came into fashion. These buckles were

exported in large quantities to France, from whence they were

returned to England and sold as the most recent productions of

French ingenuity. The elder Boulton, having every confidence

in his son's discretion and judgment, adopted him as a partners as

soon as he came of age, and from that time forward he took almost

the entire management of the concern. Although in his letters

he signed "for father and self," he always spoke in the first person

of matters connected with the business.

From the earliest glimpses we can get of Boulton as a man of

business, it seems to have been his aim to get at the head of

whatsoever branch of manufacture he undertook. He endeavoured

to produce the best possible articles, in regard to design,

material, and workmanship. Taste was then at a low ebb, and

"Brummagem" had become a byword for everything that was gaudy,

vulgar, and meretricious. Boulton endeavoured to get rid of

this reproach, and aimed at raising the standard of taste in

manufacture to the highest point. With this object, he

employed the best artists to design his articles, and the cleverest

artisans to manufacture them.

In 1759 Boulton's father died, bequeathing to him the

considerable property which he had accumulated by his business.

The year following, when thirty-two years of age, Matthew married

Anne, the daughter of Luke Robinson, Esq., of Lichfield. The

lady was a distant relation of his own; the Dyotts of Stitchbrooke,

whose heir his grandfather had married, being nearly related to the

Babingtons of Curborough, from whom Miss Robinson was lineally

descended—Luke Robinson having married the daughter and co-heir of

John Babington of Curborough and Patkington. Considerable

opposition was offered to the marriage by the lady's friends, on

account of Matthew Boulton's occupation; but he pressed his suit,

and with good looks and a handsome presence to back him, he

eventually succeeded in winning the heart and hand of Anne Robinson.

He was now, indeed, in a position to have retired from

business altogether. But a life of inactivity had no charms

for him. He liked to mix with men in the affairs of active

life, and to take his full share in the world's business.

Indeed, he hated ease and idleness, and found his greatest pleasure

in constant occupation.

Instead, therefore, of retiring from trade, he determined to

engage in it more extensively. He entertained the ambition of

founding a manufactory that should be the first of its kind, and

serve as a model for the manufacturers of his neighbourhood.

His premises on Snowhill, Birmingham, having become too small for

his purpose, he looked about him for a suitable spot on which to

erect more commodious workshops; and he was shortly attracted by the

facilities presented by the property afterwards so extensively known

as the famous Soho.

Soho is about two miles north of Birmingham, on the

Wolverhampton road. It is not in the parish of Birmingham, nor

in the county of Warwick, but just over the border, in the county of

Stafford. Down to the middle of last century the ground on

which it stands was a barren heath, used only as a rabbit-warren.

The sole dwelling on it was the warrener's hut, which stood near the

summit of the hill on the spot afterwards occupied by Soho House;

and the warrener's well is still to be found in one of the cellars

of the mansion. In 1756 Mr. Edward Ruston took a lease of the

ground for ninety-nine years from Mr. Wyerley, the lord of the

manor, with liberty to make a cut about half a mile in length for

the purpose of turning the waters of Hockley Brook into a pool under

the brow of the hill. When Mr. Boulton was satisfied that the

place would suit his purpose, he entered into arrangements with Mr.

Ruston for the purchase of his lease, on the completion of which he

proceeded to rebuild the mill on a large scale, and in course of

time removed thither the whole of his tools, machinery, and workmen.

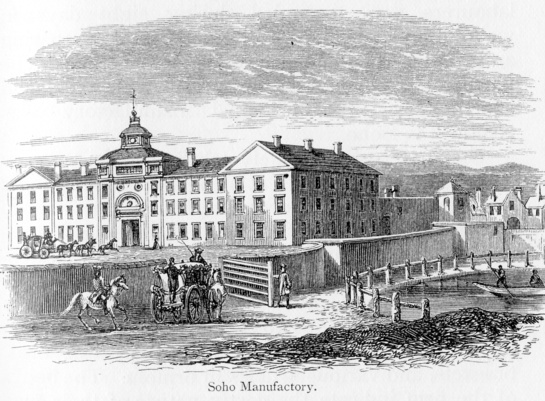

The new manufactory, when finished, consisted of a series of roomy

workshops conveniently connected with each other, and capable of

accommodating upwards of a thousand workmen. The building and

stocking of the premises cost upwards of £20,000.

Before removing to Soho, Mr. Boulton took into partnership

Mr. John Fothergill, with the object of more vigorously extending

his business operations. Mr. Fothergill possessed a very

limited capital, but he was a man of good character and active

habits of business, with a considerable knowledge of foreign

markets. On the occasion of his entering the concern, stock

was taken of the warehouse on Snow Hill; and some idea of the extent

of Boulton's business at the time may be formed from the fact that

his manager, Mr. Zaccheus Walker, assisted by Farquharson, Nuttall,

Frogatt, and half-a-dozen labourers, were occupied during eight days

in weighing metals, counting goods, and preparing an inventory of

the effects and stock-in-trade. The partnership commenced at

midsummer, 1762, and shortly after the principal manufactory was

removed to Soho.

Steps were immediately taken to open up new connexions and

agencies at home and abroad; and a large business was shortly

established in many of the principal towns and cities of Europe, in

filagree and inlaid work, in buttons, buckles, clasps, watch-chains,

and various kinds of ornamental metal wares. The firm shortly

added the manufacture of silver plate and plated goods to their

other branches, and turned out large quantities of candlesticks,

urns, brackets, and various articles in ormolu. The books of

the firm indicate the costly nature of their productions, 500 ounces

of silver being given out at a time, besides considerable quantities

of gold and plating for purposes of fabrication. Boulton

himself attended to the organization and management of the works and

to the extension of the trade at home, while Fothergill devoted

himself to establishing and superintending the foreign agencies.

From the first, Boulton aimed at establishing a character for

the excellence of his productions. They must not only be

honest in workmanship, but tasteful in design. He determined,

so far as in him lay, to get rid of the "Brummagem" reproach.

Thus we find him writing to his partner from London:—"The prejudice

that Birmingham hath so justly established against itself makes

every fault conspicuous in all articles that have the least

pretensions to taste. How can I expect the public to

countenance rubbish from Soho while they can procure sound and

perfect work from any other quarter?"

He frequently went to town for the express purpose of reading

and making drawings of rare works in metal in the British Museum,

sending the results down to Soho. When rare objects of art

were offered for sale, he endeavoured to secure them. "I bid

five guineas," he wrote his partner on one occasion, "for the Duke

of Marlborough's great blue vase, but it sold for ten . .

. . I bought two bronzed figures, which are sent

herewith." He borrowed antique candlesticks, vases, and

articles in metal from the Queen and from various members of the

nobility. "I wish Mr. Eginton," he wrote, "would take good

casts from the Hercules and the Hydra, and then let it be well gilt

and returned with the seven vases; for 'tis the Queen's. I

perceive we shall want many such figures, and therefore we should

omit no opportunity of taking good casts."

The Duke of Northumberland lent Boulton many of his most

highly-prized articles for imitation by his workmen. Among his

other liberal helpers in the same way, we find the Duke of Richmond,

Lord Shelburne, and the Earl of Dartmouth. The Duke gave him

an introduction to Horace Walpole, for the purpose of enabling him

to visit and examine the art treasures of Strawberry Hill.

"The vases," said he, in writing to Boulton, "are, in my opinion,

better worth your seeing than anything in England, and I wish you

would have exact drawings of them taken, as I may very possibly like

to have them copied by you." Lord Shelburne's opinion of

Boulton may be gathered from his letter to Mr. Adams, the architect,

in which he said:—"Mr. Boulton is the most enterprising man in

Birmingham. He is very desirous of cultivating Mr. Adams's

taste in his productions, and has bought his Dioclesian by Lord

Shelburne's advice."

Boulton, however, did not confine himself to England; he

caused search to be made over the Continent for the best specimens

of handicraft as models for imitation; and when he found them he

strove to equal, if not to excel them, in style and quality.

He sent his agent, Mr. Wendler, on a special mission of this sort to

Venice, Rome, and other Italian cities, to purchase for him the best

specimens of metal-work, and obtain for him designs of various

ornaments—vases, cameos, intaglios, and statuary. On one

occasion we find Wendler sending him 456 prints, Boulton

acknowledging that they will prove exceedingly useful for the

purposes of his manufacture. At the same time, Fothergill was

travelling through France and Germany with a like object, whilst he

was also establishing new connexions with a view to extended trade.

While Boulton was ambitious of reaching the highest

excellence in his own line of business, he did not confine himself

to that, but was feeling his way in various directions outside of

it. Thus to his friend Wedgwood he wrote on one occasion that

he admired his vases so much that he "almost wished to be a potter."

At one time, indeed, he had serious thoughts of beginning the

fictile manufacture; but he rested satisfied with mounting in metal

the vases which Wedgwood made. "The mounting of vases," he

wrote, "is a large field for fancy, in which I shall indulge, as I

perceive it possible to convert even a very ugly vessel into a

beautiful vase."

Another branch of business that he sought to establish was

the manufacture of clocks. It was one of his leading ideas,

that articles in common use might be made much better and cheaper if

manufactured on a large scale with the help of the best machinery;

and he thought this might be successfully done in the making of

clocks and timepieces. The necessary machinery was erected

accordingly, and the new branch of business was started. Some

of the timepieces were of an entirely novel arrangement. One

of them, invented by Dr. Small, contained but a single wheel, and

was considered a piece of very ingenious construction. Boulton

also sought to rival the French makers of ornamental timepieces, by

whom the English markets were then almost entirely supplied; and

some of the articles of this sort turned out by him were of great

beauty.

One of his most ardent encouragers and admirers, the Hon.

Mrs. Montagu, wrote to him,—"I take greater pleasure in our

victories over the French in the contention of arts than of arms.

The achievements of Soho, instead of making widows and orphans, make

marriages and christenings. Your noble industry, while

elevating the public taste, provides new occupations for the poor,

and enables them to bring up their families in comfort. Go on,

then, sir, to triumph over the French in taste, and to embellish

your country with useful inventions and elegant productions."

Boulton's efforts to improve the industrial arts did not,

however, always meet with such glowing eulogy as this. Two of

his most highly finished astronomical clocks could not find

purchasers at his London sale; on which he wrote to his wife at

Soho, "I find philosophy at a very low ebb in London, and I have

therefore brought back my two fine clocks, which I will send to a

market where common sense is not out of fashion. If I had made

the clocks play jigs upon bells, and a dancing bear keeping time, or

if I had made a horse-race upon their faces, I believe they would

have had better bidders. I shall therefore bring them back to

Soho, and some time this summer will send them to the Empress of

Russia, who, I believe, would be glad of them." [p.138]

During the same visit to London he was more successful with

the king and queen, who warmly patronised his productions.

"The king," he wrote to his wife, "hath bought a pair of cassolets,

a Titus, a Venus clock, and some other things, and inquired this

morning how yesterday's sale went. I shall see him again, I

believe. I was with them, the queen and all the children,

between two and three hours. There were, likewise, many of the

nobility present. Never was man so much complimented as I have

been; but I find that compliments don't make fat nor fill the

pocket. The queen showed me her last child, which is a beauty,

but none of 'em are equal to the General of Soho or the fair Maid of

the Mill. [p.139-1]

God bless them both, and kiss them for me."

In another letter he described a subsequent visit to the

palace. "I am to wait upon their majesties again so soon as

our Tripod Tea-kitchen arrives, and again upon some other business.

The queen, I think, is much improved in her person, and she now

speaks English like an English lady. She draws very finely, is

a great musician and works with her needle better than Mrs. Betty.

However, without joke she is extremely sensible, very affable, and a

great patroness of English manufactures. Of this she gave me a

particular instance; for, after the king and she had talked to me

for nearly three hours, they withdrew, and then the queen sent for

me into her boudoir, showed me her chimneypiece, and asked me how

many vases it would take to furnish it; 'for,' said she, 'all that

china shall be taken away.' She also desired that I would

fetch her the two finest steel chains I could make. All this

she did of her own accord, without the presence of the king, which I

could not help putting a kind construction upon." [p.139-2]

Thus stimulated by royal and noble patronage, Boulton exerted

himself to the utmost to produce articles of the highest excellence.

Like his friend Wedgwood, he employed Flaxman and other London

artists to design his choicer goods; but he had many foreign

designers and skilled workmen, French and Italian, in his regular

employment. He attracted these men by liberal wages, and kept

them attached to him by kind and generous treatment. On one

occasion we find the Duke of Richmond applying to him to recommend a

first-class artist to execute some special work in metal for him.

Boulton replies that he can strongly recommend one of his own men,

an honest, steady workman, an excellent metal turner. "He hath

made for me some exceeding good acromatic telescopes [another branch

of Boulton's business]. . . . I give him two guineas a week and a

house to live in. He is a Frenchman, and formerly worked with

the famous M. Germain; he afterwards worked for the Academy of

Sciences at Berlin, and he hath worked upwards of two years for me."

[p.140-1]

Before many years had passed, Soho was spoken of with pride

as one of the best schools of skilled industry in England. Its

fame extended abroad as well as at home, and when distinguished

foreigners came to England, they usually visited Soho as one of the

national sights. When the manufactory was complete [p.140-2]

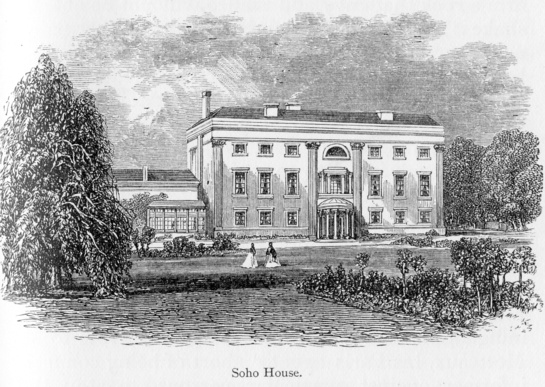

and in full work, Boulton removed from his house on Snow Hill to the

mansion of Soho. There he continued to live until the close of

his life, maintaining a splendid hospitality. Men of all

nations, and of all classes and opinions, were received there by

turns—princes, philosophers, artists, authors, merchants, and poets.

In August, 1767, while executing the two chains for the queen, we

find him writing to his London agent as his excuse for a day's delay

in forwarding it: "I had lords and ladies to wait on yesterday; I

have French and Spaniards to-day; and to-morrow I shall have

Germans, Russians, and Norwegians." For many years the

visitors at Soho House were so numerous and arrived in such constant

succession, that it more resembled an hotel than a private mansion.

The rapid extension of the Soho business necessarily led to

the increase of the capital invested in it. Boulton had to

find large sums of money for increased stock, plant, and credits.

He raised £3,000 on his wife's estate; he borrowed £5,000 from his

friend Baumgarten; and he sold considerable portions of the property

left him by his father, by which means he was enabled considerably

to extend his operations. There were envious busybodies about

who circulated rumours to his discredit, and set the report on foot

that to carry on a business on so large a scale would require a

capital of £80,000. "Their evil speaking," said he to a

correspondent, "will avail but little, as our house is founded on so

firm a rock that envy and malice will not be able to shake it; and I

am determined to spare neither pains nor money to establish such a

house as will acquire both honour and wealth." The rapid

strides he was making may be inferred from the statement made to the

same correspondent, which showed that the gross returns of the firm,

which were £7,000 in 1763, had advanced to £30,000 in 1767, with

orders still upon the increase.

Though he had a keen eye for business, Boulton regarded

character more than profit. He would have no connexion with

any transaction of a discreditable kind. Orders were sent to

him from France for base money, but he spurned them with

indignation. "I will do anything," he wrote to M. Motteaux,

his Paris agent, "short of being common informer against particular

persons, to stop the malpractices of the Birmingham coiners."

He declared he was as ready to do business on reasonable terms as

any other person, but he would not undersell; "for," said he, "to

run down prices would be to run down quality, which could only have

the effect of undermining confidence, and eventually ruining trade."

His principles were equally honourable as regarded the workmen of

rival employers. "I have had many offers and opportunities,"

he said to one, "of taking your people, whom I could, with

convenience to myself, have employed; but it is a practice I abhor.

Nevertheless, whatever game we play at, I shall always avail myself

of the rules with which 'tis played, or I know I shall make but a

very indifferent figure in it." [p.143]

He was frequently asked to take gentleman apprentices into

his works, but declined to receive them, though hundreds of pounds'

premium were in many cases offered with them. He preferred

employing the humbler class of boys, whom he could train up as

skilled workmen. He was also induced to prefer the latter for

another reason, of a still more creditable kind. "I have,"

said he, in answer to a gentleman applicant, "built and furnished a

house for the reception of one kind of apprentices—fatherless

children, parish apprentices, and hospital boys; and gentlemen's

sons would probably find themselves out of place in such

companionship."

While occupied with his own affairs, and in conducting what

he described as "the largest hardware manufactory in the world,"

Boulton found time to take an active part in promoting the measures

then on foot for opening up the internal navigation of the country.

He was a large subscriber to the Grand Trunk and Birmingham Canal

schemes, the latter of which was of the greater importance to him

personally, as it passed close by Soho, and thus placed his works in

direct communication both with London and the northern coal and

manufacturing districts.

Coming down to a few years later, in 1770, we find his

business still growing, and his works and plant absorbing still more

capital, principally obtained by borrowing. In a letter to Mr.

Adams, the celebrated architect, requesting him to prepare the

design of a new sale-room in London, he described the manufactory at

Soho as in full progress, from 700 to 800 persons being employed as

metallic artists and workers in tortoiseshell, stones, glass, and

enamel. "I have almost every machine," said he, "that is

applicable to those arts; I have two water-mills employed in

rolling, polishing, grinding, and turning various sorts of lathes.

I have trained up many, and am training up more plain country lads

into good workmen; and wherever I find indications of skill and

ability, I encourage them. I have likewise established

correspondence with almost every mercantile town in Europe, and am

thus regularly supplied with orders for the grosser articles in

common demand, by which I am enabled to employ such a number of

hands as to provide me with an ample choice of artists for the finer

branches of work; and I am thereby encouraged to erect and employ a

more extensive apparatus than it would be prudent to provide for the

production of the finer articles only."

It is indeed probable—though Boulton was slow to admit

it—that he had been extending his business more rapidly than his

capital would conveniently allow; for we find him becoming more and

more pressed for means to meet the interest on the borrowed money

invested in buildings, tools, and machinery. He had obtained

£10,000 from a Mr. Tonson of London; and on the death of that

gentleman, in 1772, he had considerable difficulty in raising the

means to pay off the debt. His embarrassment was increased by

a serious commercial panic, aggravated by the failure of Fordyce

Brothers, by which a considerable sum deposited with them remained

locked up for some time, and he was eventually a loser to the extent

of £2,000.

Other failures and losses followed; and trade came almost to

a standstill. Yet he bravely held on. "We have a

thousand mouths at Soho to feed," he says; "and it has taken so much

labour and pains to get so valuable and well-organised a staff of

workmen together, that the operations of the manufactory must

be carried on at whatever risk."

He continued to receive distinguished visitors at his works.

"Last week," he wrote Mr. Ebbenhouse, "we had Prince Poniatowski,

nephew of the King of Poland, and the French, Danish, Sardinian, and

Dutch Ambassadors; this week we have had Count Orloff, one of the

five celebrated brothers who are such favourites with the Empress of

Russia; and only yesterday I had the Viceroy of Ireland, who dined

with me. Scarcely a day passes without a visit from some

distinguished personage."

Besides carrying on the extensive business connected with his

manufactory at Soho, this indefatigable man found time to prosecute

the study of several important branches of practical science.

It was scarcely to be supposed that he had much leisure at his

disposal; but in life it often happens that the busiest men contrive

to find the most leisure; and he who is "up to the ears" in work

can, nevertheless, snatch occasional intervals to devote to

inquiries in which his heart is engaged. Hence we find Boulton

ranging at intervals over a wide field of inquiry; at one time

studying geology, and collecting fossils, minerals, and specimens

for his museum; at another, reading and experimenting on fixed air;

and at another studying Newton's works with the object of increasing

the force of projectiles. But the subject which perhaps more

than all interested him was the improvement of the Steam-Engine,

which shortly after led to his introduction to James Watt.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VII.

BOULTON AND THE STEAM-ENGINE—CORRESPONDENCE WITH WATT.

WANT of

water-power was one of the great defects of Soho as a manufacturing

establishment, and for a long time Boulton struggled with the

difficulty. The severe summer droughts obliged him to connect

a horse-mill with the water-wheel. From six to ten horses were

employed as an auxiliary power, at an expense of from five to eight

guineas a week. But this expedient, though costly, was found

very inconvenient. Boulton next thought of erecting a

pumping-engine after Savery or Newcomen's construction, for the

purpose of raising the water from the mill-stream and returning it

back into the reservoir thereby maintaining a head of water

sufficient to supply the water-wheel and keep the mill in regular

work. "The enormous expense of the horse-power," he wrote to a

friend, "put me upon thinking of turning the mill by fire, and I

made many fruitless experiments on the subject."

In 1766 we find him engaged in a correspondence with the

distinguished Benjamin Franklin as to steam power. Eight years

before, Franklin had visited Boulton at Birmingham and made his

acquaintance. They were mutually pleased with each other, and

continued to correspond during Franklin's stay in England,

exchanging their views on magnetism, electricity, and other

subjects. [p.148]

When Boulton began to study the fire-engine with a view to its

improvement, Franklin was one of the first whom he consulted.

Writing to him on the 22nd February, 1766, Boulton said,—

"My engagements since Christmas

have not permitted me to make any further progress with my

fire-engine; but, as the thirsty season is approaching apace,

necessity will oblige me to set about it in good earnest.

Query,—Which of the steam-valves do you like best? Is it

better to introduce the jet of cold water at the bottom of the

receiver or at the top? Each has its advantages and

disadvantages. My thoughts about the secondary or mechanical

contrivances of the engine are too numerous to trouble you with in

this letter, and yet I have not been lucky enough to hit upon any

that are objectionless. I therefore beg, if any thought occurs

to your fertile genius which you think may be useful, or preserve me

from error in the execution of this engine, you'll be so kind as to

communicate it to me, and you'll very greatly oblige me."

From a subsequent letter it appears that Boulton, like

Watt—who was about the same time occupied with his invention at

Glasgow—had a model constructed for experimental purposes, and that

this model was now with Franklin in London; for we find Boulton

requesting the latter to "order a porter to nail up the model in the

box again and take it to the Birmingham carrier at the Bell Inn,

Smithfield." After a silence of about a month Franklin

replied,—

"You will, I trust, excuse my so long omitting to

answer your kind letter, when you consider the excessive hurry and

anxiety I have been engaged in with our American affairs I know not

which of the valves to give the preference to, nor whether it is

best to introduce your jet of cold water above or below.

Experiments will best decide in such cases. I would only

repeat to you the hint I gave, of fixing your grate in such a manner

as to burn all your smoke. I think a great deal of fuel will

then be saved, for two reasons. One, that smoke is fuel, and

is wasted when it escapes uninflamed. The other, that it forms

a sooty crust on the bottom of the boiler, which crust not being a

good conductor of heat, and preventing flame and hot air coming into

immediate contact with the vessel, lessens their effect in giving

heat to the water. All that is necessary is, to make the smoke

of fresh coals pass descending through those that are already

thoroughly ignited. I sent the model last week, with your

papers in it, which I hope got safe to hand." [p.149]

The model duly arrived at Soho, and we find Boulton shortly

after occupied in making experiments with it, the results of which

are duly entered in his note-books. Dr. Erasmus Darwin, with

whom he was on very intimate terms, wrote to him from Lichfield,

inquiring what Franklin thought of the model and what suggestions he

had made for its improvement. "Your model of a steam-engine, I

am told," said he, "has gained so much approbation in London, that I

cannot but congratulate you on the mechanical fame you have acquired

by it, which, assure yourself, is as great a pleasure to me as it

could possibly be to yourself." [p.150]

Another letter of Darwin to Boulton is preserved without

date, but apparently written earlier than the preceding, in which

the Doctor lays before the mechanical philosopher the scheme of "a

fiery chariot" which he had conceived,—in other words, of a

locomotive steam-carriage. He proposed to apply an engine with

a pair of cylinders working alternately, to drive the proposed

vehicle; and he sent Boulton some rough diagrams illustrative of his

views, which he begged might be kept a profound secret, as it was

his intention, if Boulton approved of his plan and would join him as

a partner, to endeavour to build a model engine, and, if it

answered, to take out a joint patent for it. But Dr. Darwin's

scheme was too crude to be capable of being embodied in a working

model; and nothing more was heard of his fiery chariot.

Another of Boulton's numerous correspondents about the same

time was Dr. Roebuck, of Kinneil, then occupied with his enterprise

at Carron. He was also about to engage in working the

Boroughstoness coal mines, of the result of which he was extremely

sanguine. Roebuck wished Boulton to join him as a partner,

offering a tenth share in the concern, and to take back the share if

the result did not answer expectations. But Boulton's hands

were already full of business nearer home, and he declined the

venture. Roebuck then informed him of the invention made by

his ingenious friend Watt, and of the progress of the model engine.

This was a subject calculated to excite the interest of Boulton, who

was himself occupied in studying the same object; and he expressed a

desire to see Watt, if he could make it convenient to visit him at

Soho.

It so happened that Watt had occasion to be in London in the

summer of 1767, on the business connected with the Forth and Clyde

Canal Bill, and he determined to take Soho on his way home.

When Watt paid his promised visit, Boulton was absent; but he was

shown over the works by his friend Dr. Small, who had settled in

Birmingham as a physician, and already secured a high place in

Boulton's esteem. Watt was much struck with the admirable

arrangements of the Soho manufactory, and recognised at a glance the

admirable power of organisation which they displayed. Still

plodding wearily with his model, and contending with the "villanous

bad workmanship" of his Glasgow artisans, he could not but envy the

precision of the Soho tools and the dexterity of the Soho workmen.

Some conversation on the subject of Steam must have occurred between

him and Small, to whom he explained the nature of his invention; for

we find the latter shortly after writing Watt, urging him to come to

Birmingham and join partnership with Boulton and himself in the

manufacture of steam-engines. Although nothing came of this

proposal at the time, it had probably some effect, when communicated

to Dr. Roebuck, in inducing him to close with Watt as a partner, and

thus anticipate his Birmingham correspondents, of whose sagacity he

had the highest opinion.

In the following year Watt visited London on the business

connected with the engine patent. Small wrote to him there,

saying, "Get your patent and come to Birmingham, with as much time

to spend as you can." Watt accordingly again took Birmingham

on his way home. There he saw his future partner for the first

time, and they at once conceived a hearty liking for each other.

They had much conversation about the engine, and it greatly cheered

Watt to find that the sagacious and practical Birmingham

manufacturer should augur so favourably of its success as he did.

Shortly after, when Dr. Robison visited Soho, Boulton told him that

although he had begun the construction of his proposed

pumping-engine, he had determined to proceed no further with it

until he had ascertained the success or otherwise of Watt and

Roebuck's scheme. "In erecting my proposed engine," said he,

"I would necessarily avail myself of what I learned from Mr. Watt's

conversation; but this would not now be right without his consent."

Boulton's conduct in this proceeding was thoroughly characteristic

of the man, and affords another illustration of the general fairness

and honesty with which he acted in all his business transactions.

Watt returned to Glasgow to resume his engine experiments,

and proceed with his canal surveys. He kept up a

correspondence with Boulton, and advised him from time to time of

the progress made with his model. Towards the end of the year

we find him sending Boulton a package from Glasgow containing "one

dozen German flutes at 5s., and a copper digester £1. 10s." He

added, "I have almost finished a most complete model of my

reciprocating-engine; when it is tried, I shall advise the success."

To Dr. Small he wrote more confidentially, sending him in

January, 1769, a copy of the intended specification of his

steam-engine. He also spoke of his general business: "Our

pottery," said he, "is doing tolerably, though not as I wish.

I am sick of the people I have to do with, though not of the

business, which I expect will turn out a very good one. I have

a fine scheme for doing it all by fire or water mills, but not in

this country nor with the present people." Later, he wrote: "I

have had another three days of fever, from which I am not quite

recovered. This cursed climate and constitution will undo me."

Watt must have told Small when at Birmingham of the

probability of his being able to apply his steam-engine to

locomotion; for the latter writes him, "I told Dr. Robison and his

pupil that I hope soon to travel in a fiery chariot of your

invention." Later, Small wrote: "A linen-draper at London, one

Moore, has taken out a patent for moving wheel-carriages by steam.

This comes of thy delays. I dare say he has heard of your

inventions . . . . Do come to England with all possible speed.

At this moment how I could scold you for negligence! However,

if you will come hither soon, I will promise to be very civil, and

buy a steam-chaise of you and not of Moore. And yet it vexes

me abominably to see a man of your superior genius neglect to avail

himself properly of his great talents. These short fevers will

do you good." [p.153]

Watt replied: "If linen-draper Moore does not use my engines

to drive his chaises, he can't drive them by steam. If he

does, I will stop them. I suppose by the rapidity of his

progress and puffing he is too volatile to be dangerous . . . . You

talk to me about coming to England just as if I was an Indian that

had nothing to remove but my person. Why do we encumber

ourselves with anything else? I can't see you before July at

soonest, unless you come here. If you do I can recommend you

to a fine sweet girl, who will be anything you want her to be if you

can make yourself agreeable to her."

Badinage apart, however, there was one point on which Watt

earnestly solicited the kind services of his friend. He had

become more than ever desirous of securing the powerful co-operation

of Matthew Boulton in introducing his invention to public notice:—

"Seriously," says he, "you will

oblige me if you will negotiate the following affair:—I find that if

the engine succeeds, my whole time will be taken up in planning and

erecting Reciprocating engines, and the circulator must stand still

unless I do what I have done too often, neglect certainty for hope.

Now Mr. Boulton wants one or more engines for his own use. If

he will make a model of one of 20 inches diameter at least, I will

give him my advice and as much assistance as I can. He shall

have liberty to erect one of any size for his own use. If he

should choose to have more the terms will be easy, and I shall

consider myself much obliged to him. If it should answer, and

he should not think himself repaid for his trouble by the use of it,

he shall make and use it until he is repaid. If this be

agreeable to him let me know, and I will propose it to the Doctor

[Roebuck], and doubt not of his consent. I wish Mr. Boulton

and you had entered into some negotiation with the Doctor about

coming in as partners. I am afraid it is now too late; for the

nearer it approaches to certainty, he grows the more tenacious of

it. [p.154] For

my part I shall continue to think as I did, that it would be for our

mutual advantage. His expectations are solely from the

Reciprocator. Possibly he may be tempted to part with the half

of the Circulator to you. This I say of myself. Mr.

Boulton asked if the Circulator was contrived since our agreement.

It was; but it is a part of the scheme, and virtually included in

it." [p.155-1]

From this it will be seen how anxious Watt was to engage

Boulton in taking an interest in his invention. But though the

fly was artfully cast over the nose of the fish, still he would not

rise. The times were out of joint, business was stagnant, and

Boulton was of necessity cautious about venturing upon new

enterprises. Small doubtless communicated the views thus

confidentially conveyed to him by Watt; and in his next letter he

again pressed him to come to Birmingham and have a personal

interview with Boulton as to the engine, adding, "bring this pretty

girl with you when you come."

But, instead of Watt, Roebuck himself went to see Boulton on

the subject. During the time of this visit Watt again

communicated to Small his anxiety that Boulton should join in the

partnership. "As for myself," said he, "I shall say nothing;

but if you three can agree among yourselves, you may appoint me what

share you please, and you will find me willing to do my best to

advance the good of the whole; or, if this [the engine] should not

succeed, to do any other thing I can to make you all amends, only

reserving to myself the liberty of grumbling when I am in an ill

humour." [155-2]

Small's reply was discouraging. Both Boulton and he had

just engaged in another scheme, which would require all the ready

money at their command. Possibly the ill-success of the

experiment Watt had by this time made with his new model at Kinneil

may have had some influence in deterring them from engaging upon

what looked a very unpromising speculation. Watt was greatly

cast down at this intelligence, though he could not blame his friend

for the caution he displayed in the matter. He nevertheless

again returned to the subject in his letters to Small; and at last

Boulton was persuaded to enter into a conditional arrangement with

Roebuck, which was immediately communicated to Watt, who received

the intelligence with great exultation. "I shake hands," he

wrote to Small, "with you and Mr. Boulton in our connexion, which I

hope will prove agreeable to us all."

His joy, however, proved premature, as it turned out that the

agreement was only to the effect, that if Boulton thought proper to

exercise the option of becoming a partner in the engine to the

extent of one-third, he was to do so within a period of twelve

months, paying Roebuck a sum of £100; but this option Boulton never

exercised, and the engine enterprise seemed to be as far from

success as ever.

In the meantime Watt became increasingly anxious about his

own position. He had been spending more money on fruitless

experiments, and getting into more debt. The six months he had

been living at Kinneil had brought him in nothing. He had been

neglecting his business, and could not afford to waste more time in

prosecuting an apparently hopeless speculation. He accordingly

returned to his regular work, and proceeded with the survey of the

river Clyde, at the instance of the Glasgow Corporation. "I

would not have meddled with this," he wrote to Dr. Small, "had I

been certain of being able to bring the engine to bear. But I

cannot, on an uncertainty, refuse every piece of business that

offers. I have refused some common fire-engines, because they

must have taken my attention so up as to hinder my going on with my

own. However, if I cannot make it answer soon, I shall

certainly undertake the next that offers, for I cannot afford to

trifle away my whole life, which—God knows—may not be long.

Not that I think myself a proper hand for keeping men to their duty;

but I must use my endeavours to make myself square with the world,

though I much fear I never shall." [p.157-1]

Small lamented this apparent abandonment of the condensing

steam-engine. But although he had failed in inducing Boulton

heartily to join Watt in the enterprise he did not yet despair.

He continued to urge Watt to complete his engine, as the fourteen

years during which the patent lasted would soon be gone. At

all events he might send the drawings of his engine to Soho; and Mr.

Boulton and he would undertake to do their best to have one

constructed for the purpose of exhibiting its powers. [p.157-2]

To this Watt agreed, and about the beginning of 1770 the necessary

drawings were sent to Soho, and an engine was immediately put in

course of execution. Patterns were made and sent to

Coalbrookdale to be cast; but when the castings were received they

were found exceedingly imperfect, and were thrown aside as useless.

They were then sent to an iron-founder at Bilston to be executed;

but the result was only another failure.

About the beginning of 1770 another unsuccessful experiment

was made by Watt and Roebuck with the engine at Kinneil. The

cylinder had been repaired and made true by beating, but as the

metal of which it was made was soft, it was feared that the working

of the piston might throw it out of form. To prevent this, two

firm parallel planes were fixed, through which the piston worked, in

order to prevent its vibration. "If this should fail," Roebuck

wrote to Boulton, in giving an account of the intended trial, "then

the cylinder must be made of cast-iron. But I have great

confidence that the present engine will work completely, and by this

day se'nnight (sic.) you may expect to hear the result of our

experiments." [p.158]

The good news, however, never went to Birmingham; on the contrary,

the trial proved a failure. There was some more tinkering at

the engine, but it would not work satisfactorily; and Watt went back

to Glasgow with a heavy heart.

Small again endeavoured to induce Watt to visit Birmingham,

to superintend the erection of the engine, the materials for which

were now lying at Soho. He also held out to Watt the hope of

obtaining some employment for him in the midland counties as a

consulting engineer. But Watt could not afford to lose more

time in erecting trial-engines; and he was too much occupied at

Glasgow to leave it for the proposed uncertainty at Birmingham.

He accordingly declined the visit, but invited Small to continue the

correspondence; "for," said he, "we have abundance of matters to

discuss, though the damned engine sleep in quiet."

Small replied, professing himself satisfied that Watt was so

fully employed in his own profession at Glasgow. "Let

nothing," he said, "divert you from the business of engineering.

You are sensible that both Boulton and I engaged in the patent

scheme much more from inclination to be in some degree useful to you

than from any other principle; so that, if you are prosperous and

happy, we do not care whether you find the scheme worth prosecuting

or not." [p.159]

In replying to Small's complaint of himself, that he felt

ennuye and stupid, taking pleasure in nothing but sleep, Watt

said: "You complain of physic; I find it sufficiently stupefying to

be obliged to think on any subject but one's hobby; and I really am

become monstrously stupid, and can seldom think at all. I wish

to God I could afford to live without it; though I don't admire your

sleeping scheme. I must fatigue myself, otherwise I can

neither eat nor sleep. In short, I greatly doubt whether the

silent mansion of the grave be not the happiest abode. I am

cured of most of my youthful desires, and if ambition or avarice do

not lay hold of me, I shall be almost as much ennuye as you

say you are." [p.160-1]

Watt's prospects were, however, brightening. He was

then busily occupied in superintending the construction of the

Monkland Canal. He wrote Small that he had a hundred men

working under him, who had "made a confounded gash in a hill," at

which they had been working for twelve months; that by frugal living

he had contrived to save money enough to pay his debts,—and that he

had plenty of remunerative work before him. "The pottery," he

said, "does very well, though we make monstrous bad ware." [p.160-2]

He had not, indeed, got rid of his headaches, though he was not so

much afflicted by low spirits as he had been.

This comparatively prosperous state of Watt's affairs did

not, however, last long. The commercial panic of 1772 put a

sudden stop to most of the canal schemes then on foot. The

proprietors of the Monkland Canal could not find the necessary means

for carrying on the works, and Watt consequently lost his employment

as their engineer. He was again thrown upon the world, and

where was he to look for help? Naturally enough, he reverted

to his engine. But it was in the hands of Dr. Roebuck, who was

overwhelmed with debt, and upon the verge of insolvency. It

was clear that no help was to be looked for in that quarter.

Again he bethought him of Small's invitations to Birmingham, and of

the interest that Boulton had taken in the engine scheme.

Could he be induced at last to become a partner? He again

broached the subject to Small, telling him how his canal occupation

had failed him; and informing him that he was now ready to go to

Birmingham or anywhere else, and engage in English surveys, or do

anything that would bring him in an honest income. But, above

all, why should not Boulton and Small, now that Roebuck had failed,

join him as partners in the engine business?

By this time, Boulton himself had become involved in

difficulties arising out of the general commercial pressure, and was

more than ever averse to enter upon such an enterprise. But

Boulton having lent Roebuck a considerable sum of money, it occurred

to Watt that the amount might be taken as part of the price of

Boulton's share in the patent, if he would consent to enter into the

proposed partnership. He represented to Small the great

distress of Roebuck's situation, which he had done all that he could

to relieve. "What little I can do for him," he said, "is

purchased by denying myself the conveniences of life my station

requires, or by remaining in debt, which it galls me to the bone to

owe."

Reverting to the idea of a partnership with Boulton, he

added, "I shall be content to hold a very small share in it, or none

at all, provided I am to be freed from my pecuniary obligations to

Roebuck, and have any kind of recompense for even a part of the

anxiety and ruin it has involved me in." And again: "Although

I am out of pocket a much greater sum upon these experiments than my

proportion of the profits of the engine, I do not look upon that

money as the price of my share, but as money spent on my education.

I thank God I have now reason to believe that I can never, while I

have health, be at any loss to pay what I owe, and to live at least

in a decent manner; more, I do not violently desire." [p.162-1]

In a subsequent letter Watt promised Small that he would pay

an early visit to Birmingham, and added, "there is nowhere I so much

wish to be." In replying, Small pointed out a difficulty in

the way of the proposed partnership: "It is impossible," he wrote,

"for Mr. Boulton and me, or any other honest man, to purchase,

especially from two particular friends, what has no market price,

and at a time when they might be inclined to part with the commodity

at an undue value." [p.162-2]

He added that the high-pressure wheel-engine constructing at Soho,

after Watt's plans, was nearly ready, and that Wilkinson, of

Bradley, had promised that the boiler should be sent next week.

"Should the experiment succeed, or seem likely to succeed," he said,

"you ought to come hither immediately upon receiving the notice,

which I will instantly send. In that case we propose to unite

three things under your direction, which would altogether, we hope,

prove tolerably satisfactory to you, at least until your merit shall

be better known."

But before the experiment with the wheel-engine could be

tried at Soho, the financial ruin of Dr. Roebuck brought matters to

a crisis. He was now in the hands of his creditors, who found

his affairs in inextricable confusion. He owed some £1,200 to

Boulton, who, rather than claim against the estate, offered to take

Roebuck's two-thirds share in the engine patent in lieu of the debt.

The creditors did not value the engine patent as worth one

farthing, and were but too glad to agree to the proposal.

As Watt himself said, it was only "paying one bad debt with

another."

Boulton wrote to Watt requesting him to act as his attorney

in the matter. He confessed that he was by no means sanguine

as to the success of the engine, but, being an assayer, he was

willing "to assay it and try how much gold it contains." "The

thing," he added, "is now a shadow; 'tis merely ideal, and will cost

time and money to realise it. We have made no experiment yet

that answers my purpose, and the times are so horrible throughout

the mercantile part of Europe, that I have not had my thoughts

sufficiently disengaged to think further of new schemes." [p.163-1]

So soon as the arrangement for the transfer of Roebuck's

share to Boulton was concluded, Watt ordered the engine in the

outhouse of Kinneil to be taken to pieces, packed up, and sent to

Birmingham. [163-2]

Small again pressed him to come and superintend the work in person.

But before he could leave Scotland it was necessary that he should

complete the survey of the Caledonian Canal, which was still

unfinished. This done, he promised at once to set out for

Soho.

Watt had a very bad opinion of the fortunes of his native

country at the time when he determined to leave it. Besides

his own incessant troubles, he thought Scotland was going to the

devil. "I am still," he said, "monstrously plagued with my

headaches, and not a little with unprofitable business. I

don't mean my own whims: these I never work at when I can do any

other thing; but I have got too many acquaintances; and there are

too many beggars in this country, which I am afraid is going to the

devil altogether. Provisions continue excessively dear, and

laws are made to keep them so. But luckily the spirit of

emigration rises high, and the people seem disposed to show their

oppressive masters that they can live without them. By the

time some twenty or thirty thousand more leave the country, matters

will take a turn not much to the profit of the landholders." [p.164]

In any case, he had made up his mind to leave his own

country, of which he declared himself "heart-sick." He hated

its harsh climate, so trying to his fragile constitution.

Moreover, he disliked the people he had to deal with. He was

also badly paid for his work, a whole year's surveying having

brought him in only about £200. Out of this he had paid some

portion to Dr. Roebuck to help him in his necessity, "so that," as

he said to Dr. Small, "I can barely support myself and keep

untouched the small sum I have allotted for my visit to you."

Watt's intention was either to try to find employment as a

surveyor or engineer in England, or obtain a situation of a similar

kind abroad. He was, however, naturally desirous of

ascertaining whether it was yet possible to do anything with the

materials which now lay at Soho; and with the object of visiting his

friends there and superintending the erection of the trial-engine,

he at length made his final arrangements to leave Glasgow. We

find him arrived in Birmingham in May, 1774, where he at once

entered on a new and important phase of his professional career.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VIII.

BOULTON AND WATT—THEIR PARTNERSHIP.

WATT had now been

occupied for about nine years in working out the details of his

invention. Five years had passed since he had taken out his

patent, and he was still struggling with difficulties. Several

thousand pounds had already been expended on the engine, besides all

his study, labour, and ingenuity; yet it was still, as Boulton

expressed it, "a shadow as regarded its practical utility and

value." So long as Watt's connexion with Roebuck continued,

there was very little chance of getting it introduced to public

notice. What it was yet to become as a working power, depended

in no small degree upon the business ability, the strength of

purpose, and the length of purse, of his new partner.

Had Watt searched Europe through, probably he could not have

found a man better fitted than Matthew Boulton was, for bringing his

invention fairly before the world. Many would have thought it

rash on the part of the latter, burdened as he was with heavy

liabilities, to engage in a new undertaking of so speculative a

character. Feasible though the scheme might be, it was an

admitted fact that nearly all the experiments with the models

heretofore made had proved failures. It is true Watt firmly

believed that he had hit upon the right principle, and he was as

sanguine as ever of the eventual success of his engine. But

though inventors are usually sanguine, men of capital are not.

Capitalists are rather disposed to regard inventors as visionaries,

full of theories of what is possible rather than of well-defined

plans of what is practicable and useful.

Boulton, however, amongst his many other gifts possessed an

admirable knowledge of character. His judgment of men was

almost unerring. In Watt he had recognised at his first visit

to Soho, not only a man of original inventive genius, but a

plodding, earnest, intent, and withal an exceedingly modest man; not

given to puff, but on the contrary rather disposed to underrate the

merit of his inventions. Different though their characters

were in most respects, Boulton at once conceived a hearty liking for

him. The one displayed, in perfection, precisely those

qualities which the other wanted. Boulton was a man of ardent

and generous temperament, bold and enterprising, undaunted by

difficulty, and possessing an almost boundless capacity for work.

He was a man of great tact, clear perception, and sound judgment.

Moreover, he possessed that indispensable quality of perseverance,

without which the best talents are of comparatively little avail in

the conduct of important affairs.

While Watt hated business, Boulton loved it. He had,

indeed, a genius for business,—a gift almost as rare as a genius for

poetry, for art, or for war. He possessed a marvellous power

of organisation. With a keen eye for details he combined a

comprehensive grasp of intellect. While his senses were so

acute, that while sitting in his office at Soho, he could detect the

slightest stoppage or derangement in the machinery of that vast

establishment, and would send his messenger direct to the spot where

it had occurred, his power of imagination was such as enabled him to

look clearly along extensive lines of possible action in Europe,

America, and the East. For there is a poetic as well as a

commonplace side to business; and the man of business genius lights

up the humdrum routine of daily life by exploring the boundless

region of possibility wherever it may lie open before him.

Boulton had already won his way to the very front rank in his

calling, honestly and honourably; and he was proud of it. He

had created many new branches of industry, which gave regular

employment to hundreds of families. He had erected and

organised a manufactory which was looked upon as one of the most

complete of its kind in England, and was resorted to by visitors

from all parts of the world. But Boulton was more than a man

of business: he was a man of culture, and the friend of cultivated

men. His hospitable mansion at Soho was the resort of persons

eminent in art, in literature, and in science; and the love and

admiration with which he inspired such men, affords one of the best

proofs of his own elevation of character. Among the most

intimate of his friends and associates were Richard Lovell Edgeworth,

a gentleman of fortune, enthusiastically devoted to his

long-conceived design of moving land-carriages by steam; Captain

Keir, an excellent practical chemist, a wit and a man of learning;

Dr. Small, the accomplished physician, chemist, and mechanist;

Josiah Wedgwood, the practical philosopher and manufacturer, founder

of a new and important branch of skilled industry; Thomas Day, the

ingenious author of 'Sandford and Merton'; Dr. Darwin, the

poet-physician; Dr. Withering, the botanist; besides others who

afterwards joined the Soho circle,—not the least distinguished of

whom were Joseph Priestley and James Watt. [p.169]

Boulton could not have been very sanguine as to the success

of Watt's engine. There were a thousand difficulties in the

way of getting it introduced to general use. The principal one

was the difficulty of finding workmen capable of making it.

Watt had been constantly worried by "villanous bad workmen," who

failed to make any model that would go. It mattered not that

the principle of the engine was right; if its construction was

beyond the skill of ordinary handicraftsmen, the invention was

practically worthless. The great Smeaton was of this opinion.

When he saw the first model working at Soho, he admitted the

excellence of the contrivance, but predicted its failure, on the

ground that it was too complicated, and that workmen were not to be

found capable of manufacturing it on any large scale for general

uses.

Watt himself felt that, if the engine was ever to have a fair

chance, it was now; and that if Boulton, with his staff of skilled

workmen at command, could not make it go, the scheme must be

abandoned henceforward as impracticable. Boulton must,

however, have seen the elements of success in the invention,

otherwise he would not have taken up with it. He knew the

difficulties Watt had encountered in designing it, and he could well

appreciate the skill with which he had overcome them; for Boulton

himself, as we have seen, had for some time been occupied with the

study of the subject. But the views of Boulton on entering

into his new branch of business cannot be better expressed than in

his own words, as stated in a letter written by him to Watt in 1769,

when then invited to join the Roebuck partnership:—

"The plan proposed to me," [p.170]

said he, "is so very different from that which I had conceived at

the time I talked with you upon the subject, that I cannot think it

a proper one for me to meddle with, as I do not intend turning

engineer. I was excited by two motives to offer you my

assistance—which were, love of you, and love of a money-getting

ingenious project. I presumed that your engine would require

money, very accurate workmanship, and extensive correspondence, to

make it turn out to the best advantage; and that the best means of

keeping up our reputation and doing the invention justice would be

to keep the executive part out of the hands of the multitude of

empirical engineers, who, from ignorance, want of experience, and

want of necessary convenience, would be very liable to produce bad

and inaccurate workmanship; all which deficiencies would affect the

reputation of the invention. To remedy which, and to produce

the most profit, my idea was to settle a manufactory near my own, by

the side of our canal, where I would erect all the conveniences

necessary for the completion of engines, and from which manufactory

we would serve the world with engines of all sizes. By these

means and your assistance we could engage and instruct some

excellent workmen, who (with more excellent tools than would be

worth any man's while to procure for one single engine) could

execute the invention 20 per cent. cheaper than it would be

otherwise executed, and with as great a difference of accuracy as

there is between the blacksmith and the mathematical instrument

maker."

He went on to state that he was willing to enter upon the

speculation with these views, considering it well worth his while

"to make engines for all the world," though it would not be worth

his while "to make for three counties only"; besides, he declared

himself averse to embark in any trade that he had not the inspection

of himself. He concluded by saying, "Although there seem to be

some obstructions to our partnership in the engine trade, yet I live

in hopes that you or I may hit upon some scheme or other that may

associate us in this part of the world, which would render it still

more agreeable to me than it is, by the acquisition of such a

neighbour." [p.171]

Five years had passed since this letter was written, during

which the engine had made no way in the world. The partnership

of Roebuck and Watt had yielded nothing but vexation and debt; until

at last, fortunately for Watt—though at the time he regarded it as a

terrible calamity—Roebuck broke down, and the obstruction was

removed which prevented Watt and Boulton from coming together.

The latter at once reverted to the plan of action which he had with

so much sagacity laid down in 1769; and he invited Watt to take up

his abode at Soho until the necessary preliminary arrangements could

be made. He thought it desirable, in the first place, to erect

the engine, of which the several parts had been sent to Soho from

Kinneil, in order, if possible, to exhibit a specimen of the machine

in actual work. Boulton undertook to defray all the necessary

expenses, and to find competent workmen to carry out the

instructions of Watt, whom Boulton was also to maintain until the

engine business had become productive. [p.172]

The materials brought from Kinneil were accordingly put

together with as little delay as possible and, thanks to the greater

skill of the workmen who assisted in its erection, the engine, when

finished, worked in a more satisfactory manner than it had ever done

before. In November, 1774, Watt wrote to Dr. Roebuck,

informing him of the success of his trials; on which the Doctor

expressed his surprise that the engine should have worked at all,

"considering the slightness of the materials and its long exposure

to the injuries of the weather." Watt also wrote to his father

at Greenock. "The business I am here about has turned out

rather successful; that is to say, the fire-engine I have invented

is now going, and answers much better than any other that has yet

been made; and I expect that the invention will be very beneficial

to me." Such was Watt's modest announcement of the successful

working of the engine on which such great results depended.

Much, however, remained to be done before either Watt or

Boulton could reap any benefit from the invention. Six years

out of the fourteen for which the patent was originally taken had

already expired; and all that had been accomplished was the erection

of this experimental engine at Soho. What further period might

elapse before capitalists could be brought to recognise the

practical uses of the invention could only be guessed at; but the

probability was that the patent right would expire long before a

demand arose for the engines which should remunerate Boulton and

Watt for their investment of time, labour, and capital. And

the patent once expired, the world at large would be free to make

the engines, though Watt himself had not recovered a single farthing

towards recouping him for the long years of experiment, study, and

ingenuity which he had bestowed in bringing his invention to

perfection. These considerations made Boulton hesitate before

launching out the money necessary to provide the tools, machinery,

and buildings, for carrying on the intended manufacture on a large

scale and in the best style.

When it became known that Boulton had taken an interest in a

new engine for pumping water, he had many inquiries about it from

the mining districts. The need of a more effective engine than

any then in use was every year becoming more urgent. The

powers of Newcomen's engine had been tried to the utmost. So

long as the surface-lodes in Cornwall were worked, its power was

sufficient to clear the mines of water; but as they were carried

deeper, it was found totally inadequate for the work, and many mines

were consequently becoming gradually drowned out and abandoned.

The excessive consumption of coals by the Newcomen engines was

another serious objection to their use, especially in districts such

as Cornwall, where coal was very dear.

When Small was urging Watt to come to Birmingham and make

engines, he wrote: "A friend of Boulton's, in Cornwall, sent us word

a few days ago that four or five copper-mines are just going to be

abandoned because of the high price of coals, and begs us to apply

to them instantly. The York Buildings Company delay rebuilding

their engine, with great inconvenience to themselves, waiting for

yours. Yesterday application was made to me by a Mining

Company in Derbyshire to know when you are to be in England about

the engines, because they must quit their mine if you cannot relieve

them."

The necessity for an improved pumping power had set many

inventors to work besides Watt, and some of the less scrupulous of

them were already trying to adopt his principle in such a way as to

evade his patent. Moore, the London linen-draper, and Hatley,

one of Watt's Carron workmen, had brought out and were pushing

engines similar to Watt's; the latter having stolen and sold for a

considerable sum the working drawings of the Kinneil engine.

From these signs Boulton saw that, in the event of the engine

proving successful, he and his partner would have to defend the

invention against a host of pirates; and he became persuaded that he

would not be justified in risking his capital in the establishment

of a steam-engine manufactory unless a considerable extension of the

patent-right could be secured. To ascertain whether this was

practicable, Watt proceeded to London in the beginning of 1775, to

confer with his patent agent and take the opinion of counsel on the

subject. Mr. Wedderburn, who was advised with, recommended

that the existing patent should be surrendered, and in that case he

did not doubt that a new one would be granted.

While in London, Watt looked out for possible orders for his

engine: "I have," he wrote Boulton, "a prospect of two orders for

fire-engines here, one to water Piccadilly, and the other to serve

the south end of Blackfriars Bridge with water. I have taken

advice of several people whom I could trust about the patent.

They all agree that an Act would be much better and cheaper, a

patent being now £130, the Act, if obtainable, £110. The

present patent has eight years still to run, bearing date January,

1769. I understand there will be an almost unlimited sale for

wheel-engines to the West Indies, at the rate of £100 for each

horse's power." [p.176]

Watt also occupied some of his time in London in

superintending the adjustment of weights manufactured by Boulton and

Fothergill, then sold in considerable quantities through their

London agent. That he continued to take an interest in his old

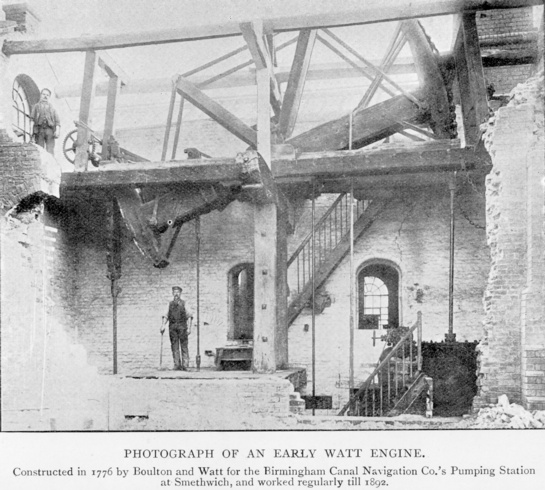

business of mathematical instrument making is apparent from the