|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER IV.

WATT'S EXPERIMENTS ON STEAM-INVENTS THE

SEPARATE CONDENSER.

IT was in the year 1759

that Robison first called the attention of his friend Watt to the

subject of the steam-engine. Robison was then only in his

twentieth, and Watt in his twenty-third year. Robison's idea

was that the power of steam might be advantageously applied to the

driving of wheel-carriages, and he suggested that it would be most

convenient for the purpose to place the cylinder with its open end

downwards to avoid the necessity of using a working beam. Watt

admits that he was very ignorant of the steam-engine at that time.

Nevertheless, he began making a model with two cylinders of

tin-plate, intending that the pistons and their connecting-rods

should act alternately on two pinions attached to the axles of the

carriage-wheels. But the model, being slightly and

inaccurately made, did not answer his expectations. Other

difficulties presented themselves, and the scheme was laid aside on

Robison leaving Glasgow to go to sea. Indeed, mechanical

science was not yet ripe for the locomotive. Robison's idea

had, however, dropped silently into the mind of his friend, where it

grew from day to day, slowly and at length fruitfully.

At his intervals of leisure and in the quiet of his evenings,

Watt continued to prosecute his various studies. He was shortly

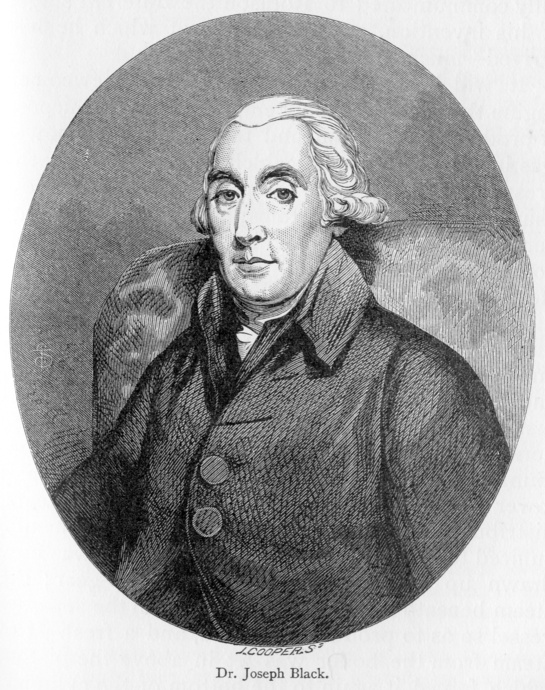

attracted by the science of chemistry, then in its infancy. Dr.

Black was at that time occupied with the investigations which led to

his discovery of the theory of latent heat, and it is probable that

his familiar conversations with Watt on the subject induced the

latter to enter upon a series of experiments with the view of giving

the theory some practical direction. His attention again and again

reverted to the steam-engine, though he had not yet seen even a

model of one. Steam was as yet almost unknown in Scotland as a

working power. The first engine was erected at Elphinstone Colliery,

in Stirlingshire, about the year 1750; and the second more than ten

years later, at Govan Colliery, near Glasgow, where it was known by

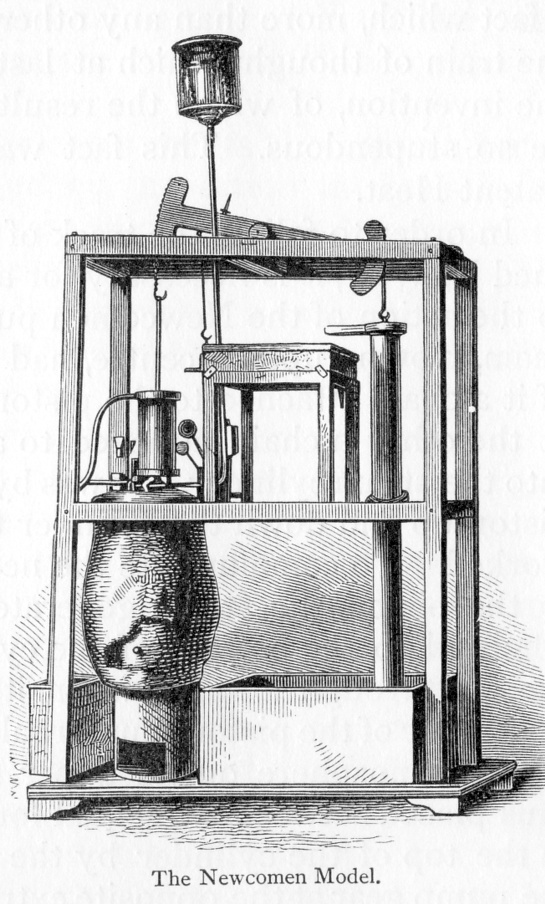

the startling name of "The Firework." Watt found that the College

possessed the model of a Newcomen engine for the use of the Natural

Philosophy class, which, at the time of his inquiry, had been sent

to London for repair. On hearing of its existence, he suggested to

his friend Dr. Anderson, Professor of Natural Philosophy, the

propriety of getting back the model; and a sum of money was placed

by the Senatus at the Professor's disposal "to recover the

steam-engine from Mr. Sisson, instrument maker, in London."

In the meantime Watt sought to learn all that had been written on

the subject of the steam-engine. He ascertained from

Desaguliers, from Switzer, and other writers, what had been

accomplished by Savery, Newcomen, Beighton and others: and he went

on with his own independent experiments. His first apparatus

was of the simplest possible kind. He used common

apothecaries' phials for his steam reservoirs, and canes hollowed

out for his steam pipes. [p.81]

In 1761 he proceeded to experiment on the force of steam by means of

a small Papin's digester and a syringe. The syringe was only

the third of an inch in diameter, fitted with a solid piston; and it

was connected with the digester by a pipe furnished with a stopcock,

by which the steam was admitted or shut off at will. It was

also itself provided with a stopcock, enabling a communication to be

opened between the syringe and the outer air to permit the steam in

the syringe to escape. The apparatus, though rude, enabled the

experimenter to ascertain some important facts. When the steam

in the digester was raised and the cock turned, enabling it to rush

against the lower side of the piston, he found that the expansive

force of the steam raised a weight of fifteen pounds with which the

piston was loaded. Then, on turning the cock and shutting off

the connexion with the digester at the same time that a passage was

opened to the air, the steam was allowed to escape, when the weight

upon the piston, being no longer counteracted, immediately forced it

to descend.

Watt saw that it would be easy to contrive that the cocks

should be turned by the machinery itself instead of by the hand, and

the whole be made to work by itself with perfect regularity.

But there was an objection to this method. Water is converted

into vapour as soon as its elasticity is sufficient to overcome the

weight of the air which keeps it down. Under the ordinary

pressure of the atmosphere water acquires this necessary elasticity

at 212°; but as the steam in the digester was prevented from

escaping, it acquired increased heat, and by consequence increased

elasticity. Hence it was that the steam which issued from the

digester was not only able to support the piston and the air which

pressed upon its upper surface, but the additional load with which

the piston was weighted. With the imperfect mechanical

construction, however, of those days, there was a risk lest the

boiler should be burst by the steam, which forced its way through

the ill-made joints of the machine. This, conjoined with the

great expenditure of steam on the high-pressure system, led Watt to

abandon the plan; and the exigencies of his business for a time

prevented him pursuing his experiments.

At length the Newcomen model arrived from London; and, in

1763, the little engine, which was destined to become so famous, was

put into the hands of Watt. The boiler was somewhat smaller

than an ordinary tea-kettle. The cylinder of the engine was

only of two inches diameter and six inches stroke. Watt at

first regarded it as merely "a fine play thing." It was,

however, enough to set him upon a track of thinking which led to the

most important results.

When he had repaired the model and set it to work, he found

that the boiler, though apparently large enough, could not supply

steam in sufficient quantity, and only a few strokes of the piston

could be obtained, when the engine stopped. The fire was urged

by blowing, and more steam was produced, but still it would not work

properly.

Exactly at the point at which another man would have

abandoned the task in despair, the mind of Watt became thoroughly

roused. "Everything," says Professor Robison, "was to him the

beginning of a new and serious study; and I knew that he would not

quit it till he had either discovered its insignificance, or had

made something of it." Thus it happened with the phenomena

presented by the model of the steam-engine. Watt referred to

his books, and endeavoured to ascertain from them by what means he

might remedy the defects which he found in the model; but they could

tell him nothing. He then proceeded with an independent course

of experiments, resolved to work out the problem for himself.

In the course of his inquiries he came upon a fact which, more than

any other, led his mind into the train of thought which at last

conducted him to the invention, of which the results were destined

to be so stupendous. This fact was the existence of Latent

Heat.

Ed.—Newcomen pumping engine. Picture Wikipedia.

In order to follow the track of investigation pursued by

Watt, it is necessary for a moment to revert to the action of the

Newcomen pumping-engine. A beam, moving upon a centre, had

affixed to one end of it a chain attached to the piston of the pump,

and at the other a chain attached to a piston that fitted into the

steam cylinder. It was by driving this latter piston up and

down the cylinder that the pump was worked. To communicate the

necessary movement to the piston, the steam generated in a boiler

was admitted to the bottom of the cylinder, forcing out the air

through a valve, when its pressure on the under side of the piston

counterbalanced the pressure of the atmosphere on its upper side.

The piston, thus placed between two equal forces, was drawn up to

the top of the cylinder by the greater weight of the pump gear at

the opposite extremity of the beam. The steam, so far, only

discharged the office which was performed by the air it displaced;

but, if the air had been allowed to remain, the piston once at the

top of the cylinder could not have returned, being pressed as much

by the atmosphere underneath as by the atmosphere above it.

The steam, on the contrary, which was admitted by the exclusion of

the air, could be condensed, and a vacuum created, by injecting cold

water through the bottom of the cylinder. The piston, being

now unsupported, was forced down by the pressure of the atmosphere

on its upper surface. When the piston reached the bottom, the

steam was again let in, and the process was repeated. Such was

the engine in ordinary use for pumping water at the time that Watt

began his investigations.

Among his other experiments, he constructed a boiler which

showed by inspection the quantity of water evaporated in any given

time, and the quantity of steam used in every stroke of the engine.

He was astonished to discover that a small quantity of water in the

form of steam heated a large quantity of cold water injected into

the cylinder for the purpose of cooling it; and upon further

examination he ascertained that steam heated six times its weight of

cold water down to 212°, which was the temperature of the steam

itself. "Being struck with this remarkable fact," says Watt,

"and not understanding the reason of it, I mentioned it to my friend

Dr. Black, who then explained to me his doctrine of latent heat,

which he had taught for some time before this period (the summer of

1764); but having myself been occupied by the pursuits of business,

if I had heard of it I had not attended to it, when I thus stumbled

upon one of the material facts by which that beautiful theory is

supported."

When Watt found that water, in its conversion into vapour,

became such a reservoir of heat, he was more than ever bent on

economising it; for the great waste of heat, involving so heavy a

consumption of fuel, was felt to be the principal obstacle to the

extended employment of steam as a motive power. He accordingly

endeavoured, with the same quantity of fuel, at once to increase the

production of steam, and to diminish its waste. He increased

the heating surface of the boiler by making flues through it; he

surrounded his boiler with wood, as being a worse conductor of heat

than the brickwork which surrounds common furnaces; and he cased the

cylinders and all the conducting-pipes in materials which conducted

heat very slowly. But none of these contrivances were

effectual; for it turned out that the chief expenditure of steam,

and consequently of fuel, in the Newcomen engine was occasioned by

the re-heating of the cylinder after the steam had been condensed by

the cold water admitted into it. Nearly four-fifths of the

whole steam employed was condensed on its first admission, before

the surplus could act upon the piston.

Watt therefore came to the conclusion that to make a perfect

steam-engine it was necessary that the cylinder should be always

as hot as the steam that entered it; but it was equally

necessary that the steam should be condensed when the piston

descended—nay, that it should be cooled down below 100°, or a

considerable amount of vapour would be given off, which would resist

the descent of the piston, and diminish the power of the engine.

Thus the cylinder was never to be at a less temperature than 212°,

and yet at each descent of the piston it was to be less than 100°;

conditions which, on the very face of them, seemed to be wholly

incompatible.

We revert for a moment to the progress of Watt's

instrument-making business. The shop in the College was not

found to answer, being too far from the principal thoroughfares.

If he wanted business he must go nearer to the public, for it was

evident that they would not come to him. But to remove to a

larger shop, in a more central quarter, involved an expenditure of

capital for which he was himself unequal. His father had

helped him with money as long as he could, but could do so no

longer. He had grown poor by his losses, and, instead of

giving his son help, needed help himself. Watt therefore

looked about him for a partner with some means, and succeeded in

finding one in a Mr. John Craig; in conjunction with whom he opened

a retail shop in the Salt-market, nearly opposite St. Andrew's

Street, about the year 1760; removing from thence to Buchanan's

Land, on the north side of the Trongate, a few years later. [p.87]

Watt's partner was not a mechanic, but he supplied the requisite

capital, and attended to the books. The partnership was on the

whole successful, as we infer from the increased number of hands

employed. At first Watt could execute all his orders himself,

and afterwards by the help of a man and a boy; but by the end of

1764 the number of hands employed by the firm had increased to

sixteen.

His improving business brought with it an improving income,

and Watt—always a frugal and thrifty man—began to save a little

money. He was encouraged to economise by another

circumstance—his intended marriage with his cousin, Margaret Miller.

In anticipation of this event, he had removed from his rooms in the

College to a house in Delftfield Lane—a narrow passage then parallel

with York Street, but now converted into the spacious thoroughfare

of Watt Street. Having furnished his house in a plain yet

comfortable style, he brought home his young wife, and installed her

there in July, 1764. The step was one of much importance to

his personal well-being. Mrs. Watt was of a lively, cheerful

temperament and as Watt himself was of a meditative disposition,

prone to melancholy, and a frequent sufferer from nervous headache,

her presence at his fireside could not fail to have a beneficial

influence upon his health and comfort.

Watt continued to pursue his studies as before. Though

still occupied with his inquiries and experiments as to steam, he

did not neglect his proper business, but was constantly on the

look-out for improvements in instrument making. A machine

which he invented for drawing in perspective proved a success; and

he made a considerable number of them to order for customers in

London as well as abroad. He was also an indefatigable reader,

and continued to extend his knowledge of chemistry and mechanics by

perusal of the best books on these sciences.

Above all other subjects, however, the improvement of the

steam-engine continued to keep the fastest hold upon his mind.

He still brooded over his experiments with the Newcomen model, but

did not seem to make much way in introducing any practical

improvement in its mode of working. His friend Robison says he

struggled long to condense with sufficient rapidity without

injection, trying one expedient after another, finding out what

would do by what would not do, and exhibiting many beautiful

specimens of ingenuity and fertility of resource. He

continued, to use his own words, "to grope in the dark, misled by

many an ignis fatuus." It was a favourite saying of his

that "Nature has a weak side, if we can only find it out;" and he

went on groping and feeling for it, but as yet in vain. At

length light burst upon him, and all at once the problem over which

he had been brooding was solved.

One Sunday afternoon, in the spring of 1765, he went to take

an afternoon walk on the Green, then a quiet, grassy meadow, used as

a bleaching and grazing ground. On week-days the Glasgow

lasses came thither with their largest kail-pots, to boil their

clothes in; and sturdy queans might be seen, with coats kilted,

tramping blankets in their tubs. On Sundays the place was

comparatively deserted, and hence Watt went thither to take a quiet

afternoon stroll. His thoughts were as usual running on the

subject of his unsatisfactory experiments with the Newcomen engine,

when the first idea of the separate condenser suddenly

flashed upon his mind. But the notable discovery is best told

in his own words, as related to Mr. Robert Hart many years after:—

"I had gone to take a walk on a fine Sabbath afternoon.

I had entered the Green by the gate at the foot of Charlotte Street,

and had passed the old washing-house. I was thinking upon the

engine at the time, and had gone as far as the herd's house, when

the idea came into my mind that as steam was an elastic body it

would rush into a vacuum, and if a communication were made between

the cylinder and an exhausted vessel, it would rush into it, and

might be there condensed without cooling the cylinder. I then

saw that I must get rid of the condensed steam and injection water

if I used a jet, as in Newcomen's engine. Two ways of doing

this occurred to me. First, the water might be run off by a

descending pipe, if an off-let could be got at the depth of 35 or 36

feet, and any air might be extracted by a small pump. The

second was to make the pump large enough to extract both water and

air." He continued: "I had not walked further than the

Golf-house [p.90-1]

when the whole thing was arranged in my mind." [p.90-2]

Great and prolific ideas are almost always simple. What

seems impossible at the outset appears so obvious when it is

effected that we are prone to marvel that it did not force itself at

once upon the mind. Late in life Watt, with his accustomed

modesty, declared his belief that if he had excelled it had been by

chance and the neglect of others. To Professor Jardine he said

"that when it was analysed, the invention would not appear so great

as it seemed to be. In the state," said he, "in which I found

the steam-engine, it was no great effort of mind to observe that the

quantity of fuel necessary to make it work would for ever prevent

its extensive utility. The next step in my progress was

equally easy—to inquire what was the cause of the great consumption

of fuel: this, too, was readily suggested, viz., the waste of fuel

which was necessary to bring the whole cylinder, piston, and

adjacent parts from the coldness of water to the heat of steam, no

fewer than from fifteen to twenty times in a minute." The

question then occurred, how was this to be avoided or remedied?

It was at this stage that the idea of carrying on the condensation

in a separate vessel flashed upon his mind, and solved the

difficulty.

Mankind has been more just to Watt than he was to himself.

There was no accident in the discovery. It was the result of

close and continuous study; and the idea of the separate condenser

was merely the last step of a long journey—a step which could not

have been taken unless the road which led to it had been carefully

and thoughtfully traversed. Dr. Black says, "This capital

improvement flashed upon his mind at once, and filled him with

rapture"; a statement which, spite of the unimpassioned nature of

Watt, we can readily believe.

On the morning following his Sunday afternoon's walk on Glasgow

Green, Watt was up betimes making arrangements for a speedy trial of

his new plan. He borrowed from a college friend a large brass

syringe, an inch and a third in diameter, and ten inches long, of

the kind used by anatomists for injecting arteries with wax previous

to dissection. The body of the syringe served for a cylinder,

the piston-rod passing through a collar of leather in its cover.

A pipe connected with the boiler was inserted at both ends for the

admission of steam, and at the upper end was another pipe to convey

the steam to the condenser. The axis of the stem of the piston

was drilled with a hole, fitted with a valve at its lower end, to

permit the water produced by the condensed steam on first filling

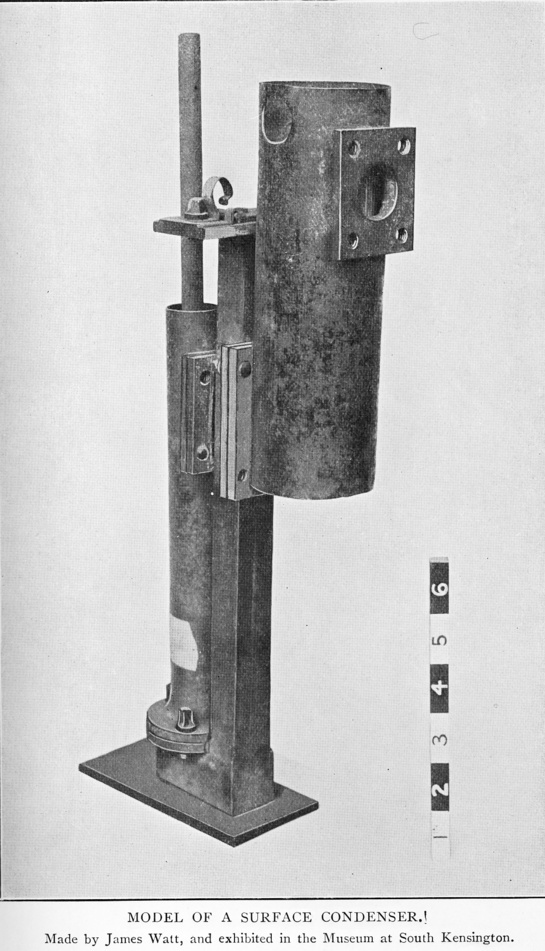

the cylinder to escape. The first condenser made use of was an

improvised cistern of tinned plate, provided with a pump to get rid

of the water formed by the condensation of the steam, both the

condensing-pipes and the air-pump being placed in a reservoir of

cold water.

"The steam-pipe," says Watt, "was adjusted to a small boiler.

When steam was produced, it was admitted into the cylinder, and soon

issued through the perforation of the rod, and at the valve of the

condenser; when it was judged that the air was expelled, the

steam-cock was shut, and the air-pump piston-rod was drawn up, which

leaving the small pipes of the condenser in a state of vacuum, the

steam entered them and was condensed. The piston of the

cylinder immediately rose and lifted a weight of about 18 lbs.,

which was hung to the lower end of the piston-rod. The

exhaustion-cock was shut, the steam was re-admitted into the

cylinder, and the operation was repeated. The quantity of

steam consumed and the weights it could raise were observed, and,

excepting the non-application of the steam-case and external

covering, the invention was complete, in so far as regarded the

savings of steam and fuel."

But, although the invention was complete in Watt's mind, it

took him many long and laborious years to work out the details of

the engine. His friend Robison, with whom his intimacy was

maintained during these interesting experiments, has given a graphic

account of the difficulties which he successively encountered and

overcame. He relates that on his return from the country,

after the College vacation in 1765, he went to have a chat with Watt

and communicate to him some observations he had made on Desagulier's

and Belidor's account of the steam-engine. He went straight

into the parlour, without ceremony, and found Watt sitting before

the fire looking at a little tin cistern which he had on his knee.

Robison immediately started the conversation about steam, his mind,

like Watt's, being occupied with the means of avoiding the excessive

waste of heat in the Newcomen engine. Watt, all the while,

kept looking into the fire, and after a time laid down the cistern

at the foot of his chair, saying nothing. It seems that Watt

felt rather nettled at Robison having communicated to a mechanic of

the town a contrivance which he had hit upon for turning the cocks

of his engine. When Robison therefore pressed his inquiry,

Watt at length looked at him and said briskly, "You need not fash

yourself any more about that, man; I have now made an engine that

shall not waste a particle of steam. It shall all be boiling

hot,—ay, and hot water injected, if I please." He then pushed

the little tin cistern with his foot under the table.

Robison could learn no more of the new contrivance from Watt

at that time; but on the same evening he accidentally met a mutual

acquaintance, who, supposing he knew as usual the progress of Watt's

experiments, observed to him, "Well, have you seen Jamie Watt?"

"Yes." "He'll be in fine spirits now with his engine?"

"Yes," said Robison, "very fine spirits." "Gad!" said the

other, "the separate condenser's the very thing: keep it but cold

enough, and you may have a perfect vacuum, whatever be the heat of

the cylinder." This was Watt's secret, and the nature of the

contrivance was clear to Robison at once.

It will be observed that Watt had not made a secret of it to

his other friends. Indeed Robison himself admitted that one of

Watt's greatest delights was to communicate the results of his

experiments to others, and set them upon the same road to knowledge

with himself; and that no one could display less of the small

jealousy of the tradesman than he did. To his intimate friend,

Dr. Black, he communicated the progress made by him at every stage;

and the Doctor kindly encouraged him in his struggles, cheered him

in his encounter with difficulty, and, what was of still more

practical value at the time, he helped him with money to enable him

to prosecute his invention.

Communicative though Watt was disposed to be, he learnt

reticence when he found himself exposed to the depredations of the

smaller fry of inventors. Robison says that had he lived in

Birmingham or London at the time, the probability is that some one

or other of the numerous harpies who live by sucking other people's

brains would have secured patents for his more important inventions,

and thereby deprived him of the benefits of his skill, science, and

labour. As yet, however, there were but few mechanics in

Glasgow capable of understanding or appreciating the steam-engine;

and the intimate friends to whom he freely spoke of his discovery

were too honourable-minded to take advantage of his confidence.

Shortly after, Watt fully communicated to Robison the different

stages of his invention, and the results at which he had

arrived—much to the delight of his friend.

It will be remembered that in the Newcomen engine the steam

was only employed for the purpose of producing a vacuum, and that

its working power was in the down stroke, which was effected by the

pressure of the air upon the piston; hence it is now usual to call

it the Atmospheric engine. Watt perceived that the air which

followed the piston down the cylinder would cool the latter, and

that steam would be wasted in re-heating it. In order,

therefore, to avoid this loss of heat, he resolved to put an

air-tight cover upon the cylinder, with a hole and stuffing-box for

the piston-rod to slide through, and to admit steam above the

piston, to act upon it instead of the atmosphere. When the

steam had done its duty in driving down the piston, a communication

was opened between the upper and lower part of the cylinder, and the

same steam, distributing itself equally in both compartments,

sufficed to restore equilibrium. The piston was now drawn up

by the weight of the pump-gear; the steam beneath it was then

condensed in the separate vessel so as to produce a vacuum, and a

fresh jet of steam from the boiler was let in above the piston,

which forced it again to the bottom of the cylinder. From an

atmospheric it had thus become a true steam engine, and with a much

greater economy of steam than when the air did half the duty.

But it was not only important to keep the air from flowing down the

inside of the cylinder: the air which circulated within cooled the

metal and condensed a portion of the steam within; and this Watt

proposed to remedy by a second cylinder, surrounding the first with

an interval between the two which was to be kept full of steam.

One by one these various contrivances were struck out,

modified, settled, and reduced to definite plans; the separate

condenser, the air and water pumps, the use of fat and oil (instead

of water as in the Newcomen engine) to keep the piston working in

the cylinder air-tight, and the enclosing of the cylinder itself

within another to prevent the loss of heat. They were all but

emanations from the first idea of inventing an engine working by a

piston in which the cylinder should be kept continually hot and

perfectly dry. "When once," says Watt, "the idea of separate

condensation was started, all these improvements followed as

corollaries in quick succession; so that in the course of one or two

days the invention was thus far complete in my mind." [p.97]

The next step was to construct a model engine for the purpose

of embodying the invention in a working form. With this object

Watt hired an old cellar, situated in the first wide entry to the

north of the beef-market in King-street, and there proceeded with

his model. He found it much easier, however, to prepare his

plan than to execute it. Like most ingenious and inventive

men, Watt was extremely fastidious; and this occasioned considerable

delay in the execution of the work. His very inventiveness to

some extent proved a hindrance; for new expedients were perpetually

occurring to him, which he thought would be improvements, and which

he, by turns, endeavoured to introduce. Some of these

expedients he admits proved fruitless, and all of them occasioned

delay. Another of his chief difficulties was in finding

competent workmen to execute his plans. He himself had been

accustomed only to small metal work, with comparatively delicate

tools, and had very little experience "in the practice of mechanics

in great," as he termed it. He was therefore under the

necessity of depending, in a great measure, upon the handiwork of

others. Mechanics capable of working out Watt's designs in

metal were scarcely to be found at that time in Scotland. The

beautiful self-acting tools and workmanship which have since been

called into being, principally by his own invention, did not then

exist. The only available hands in Glasgow were the

blacksmiths and tinners, little capable of constructing articles out

of their ordinary business; and even in these they were found

clumsy, blundering, and incompetent. The result was, that in

consequence of the malconstruction of the larger parts, Watt's first

model was only partially successful. The experiments made with

it, however, served to verify the expectations he had formed, and to

place the advantages of the invention beyond the reach of doubt.

On the exhausting-cock being turned, the piston, when loaded with 18

lbs., ascended as quick as the blow of a hammer; and the moment the

steam-cock was opened, it descended with like rapidity, though the

steam was weak, and the machine snifted at many openings.

Satisfied that he had laid hold of the right principle of a

working steam-engine, Watt felt impelled to follow it to an issue.

He could give his mind to no other business in peace until this was

done. He wrote to a friend that he was quite barren on every

other subject. "My whole thoughts," said he, "are bent on this

machine. I can think of nothing else." [p.99]

He proceeded to make another and bigger, and, he hoped, a

satisfactory engine in the following August; and with that object he

removed from the old cellar in King-street to a larger apartment in

the then disused pottery or delftwork near the Broomielaw.

There he shut himself up with his assistant, John Gardiner, for the

purpose of erecting his engine. The cylinder was five or six

inches in diameter, with a two-feet stroke. The inner cylinder

was enclosed in a wooden steam-case, and placed inverted, the piston

working through a hole in the bottom of the steam-case. After

two months' continuous application and labour it was finished and

set to work; but it leaked in all directions, and the piston was far

from air-tight. The condenser also was in a bad way, and

needed many alterations. Nevertheless, the engine readily

worked with 10½ lbs. pressure on the inch, and the piston lifted a

weight of 14 lbs.

The improvement of the cylinder and piston continued Watt's

chief difficulty, and taxed his ingenuity to the utmost. At so

low an ebb was the art of making cylinders that the one he used was

not bored but hammered, the collective mechanical skill of Glasgow

being then unequal to the boring of a cylinder of the simplest kind;

nor, indeed, did the necessary appliances for the purpose exist

anywhere else. In the Newcomen engine a little water was

poured upon the upper surface of the piston, and sufficiently filled

up the interstices between the piston and the cylinder. But

when Watt employed steam to drive down the piston, he was deprived

of this resource, for the water and the steam could not coexist.

Even if he had retained the agency of the air above, the drip of

water from the crevices into the lower part of the cylinder would

have been incompatible with keeping the surface hot and dry, and, by

turning into vapour as it fell upon the heated metal, it would have

impaired the vacuum during the descent of the piston.

While he was occupied with this difficulty, and striving to

overcome it by the adoption of new expedients, such as leather

collars and improved workmanship, he wrote to a friend, "My old

white-iron man is dead"; the old white-iron man, or tinner, being

his leading mechanic. Unhappily, also, just as he seemed to

have got the engine into working order, the beam broke, and having

great difficulty in replacing the damaged part, the accident

threatened, together with the loss of his best workman, to bring the

experiment to an end. But though discouraged by these

misadventures, he was far from defeated, but went on as before,

battling down difficulty inch by inch, and holding good the ground

he had won, becoming every day more strongly convinced that he was

in the right track, and that the important uses of his invention,

could he but find time and means to perfect it, were beyond the

reach of doubt.

But how to find the means! Watt himself was a

comparatively poor man. He had no money but what he earned by

his business of mechanical instrument making, which he had for some

time been neglecting through his devotion to the construction of his

engine. What he wanted was capital, or the help of a

capitalist willing to advance the necessary funds to perfect his

invention. To give a fair trial to the new apparatus would

involve an expenditure of several thousand pounds; and who on the

spot could be expected to invest so large a sum in trying a machine

so entirely new, depending for its success on physical principles so

very imperfectly understood?

There was no such help to be found in Glasgow. The

tobacco lords, though rich, took no interest in steam power and the

manufacturing class, though growing in importance, had full

employment for their little capital in their own concerns.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER V.

WATT'S CONNEXION WITH DR. ROEBUCK—WATT

ACTS AS SURVEYOR AND ENGINEER.

DR.

BLACK continued to

take a lively interest in Watt's experiments, and lent him

occasional sums of money from time to time to enable him to

prosecute them to an issue. But the Doctor's means were too

limited to permit him to do more than supply Watt's more pressing

necessities. Meanwhile, the debts which the latter had already

incurred, small though they were in amount, hung like a millstone

round his neck. Black then bethought him whether it would not

be possible to associate Watt with some person possessed of

sufficient means, and of an active commercial spirit, who should

join as a partner in the risk, and share in the profits of the

enterprise. Such a person, he thought, was Dr. Roebuck, the

founder of the Carron Iron Works, an enterprising man, of undaunted

spirit, not scared by difficulties, nor a niggard of expense when he

saw before him any reasonable prospect of advantage. [p.102]

Roebuck was at that time engaged in sinking for coal on a

large scale near Boroughstoness, where he experienced considerable

difficulty in keeping the shafts clear of water. The Newcomen

engine, which he had erected, was found comparatively useless, and

he was ready to embrace any other scheme which held out a reasonable

prospect of success. Accordingly, when his friend Dr. Black

informed him of an ingenious young mechanic at Glasgow who had

invented a steam-engine, capable of working with increased power,

speed, and economy, Roebuck immediately felt interested and entered

into correspondence with Watt on the subject. He was at first

somewhat sceptical as to the practicability of the new engine, so

different in its action from that of Newcomen; and he freely stated

his doubts to Dr. Black. He was under the impression that

condensation might in some way be effected in the cylinder without

injection; and he urged Watt to try whether this might not be done.

Contrary to his own judgment, Watt tried a series of experiments

with this object, and at last abandoned them, Roebuck himself

admitting his error.

Up to this time Watt and Roebuck had not met, though they

carried on a long correspondence on the subject of the engine.

In September, 1765, we find Roebuck inviting Watt to come over with

Dr. Black to Kinneil (where Roebuck lived), and discuss with him the

subject of the engine. Watt wrote to say that "if his foot

allowed him" he would visit Carron on a certain day,—from which we

infer that he intended to walk. But the way was long and the

road miry, and Watt could not then leave his instrument shop; so the

visit was postponed. In the meantime Roebuck urged Watt to

press forward his invention with all speed, "whether he pursued it

as a philosopher or as a man of business."

In the month of November following Watt forwarded to Roebuck

the detailed drawings of a covered cylinder and piston to be cast at

the Carron Works. Though the cylinder was the best that could

be made there, it was very ill-bored, and was eventually laid aside

as useless. The piston-rod was made at Glasgow, under Watt's

own supervision; and when it was completed he was afraid to send it

on a common cart, lest the workpeople should see it, which would

"occasion speculation." "I believe," he wrote in July, 1766,

"it would be best to send it in a box." These precautions

would seem to have been dictated, in some measure, by fear of

piracy; and it is obvious that the necessity of acting by stealth

increased the difficulty of getting the various parts of the

proposed engine constructed. Watt's greatest obstacle

continued to be the clumsiness and inexpertness of his mechanics.

"My principal hindrance in erecting engines," he wrote to Roebuck,

"is always the smith-work."

In the meantime it was necessary for Watt to attend to the

maintenance of his family. He found that the steam-engine

experiments brought nothing in, while they were a constant source of

expense. Besides, they diverted him from his retail business,

which needed constant attention. It ought also to be mentioned

that, his partner having lately died, the business had been somewhat

neglected and had consequently fallen off. At length he

determined to give it up altogether, and to begin the business of a

surveyor. He accordingly removed from the shop in Buchanan's

Land to an office on the east side of King-street a little south of

Prince's-street. It would appear that he succeeded in

obtaining a fair share of business in his new vocation. He

already possessed a sufficient knowledge of surveying from the study

of the instruments which it had been his business to make; and

application and industry did the rest. His first jobs were in

surveying lands, defining boundaries, and surveyor's work of the

ordinary sort; from which he gradually proceeded to surveys of a

more important character.

It affords some indication of the local estimation in which

Watt was held that the magistrates of Glasgow should have selected

him as a proper person to survey a canal for the purpose of opening

up a new coal-field in the neighbourhood, and connecting it with the

city, with a view to a cheaper and more abundant supply of fuel.

He also surveyed a ditch-canal for the purpose of connecting the

rivers Forth and Clyde, by what was called the Loch Lomond passage;

though the scheme of Brindley and Smeaton was eventually preferred

as the more direct line. Watt came up to London in 1767, in

connection with the application to Parliament for powers to

construct his canal; and he seems to have been very much disgusted

with the proceedings before "the confounded committee of

Parliament," as he called it; adding, "I think I shall not wish to

have anything to do with the House of Commons again. I never

saw so many wrong-headed people on all sides gathered together."

The fact, however, that they had decided against him had probably

some share in leading him to form this opinion as to the

wrongheadedness of the Parliamentary Committee.

Though interrupted by indispensable business of this sort,

Watt proceeded with the improvement of his steam-engine whenever

leisure permitted. Roebuck's confidence in its eventual

success was such that in 1767 he undertook to pay debts to the

amount of £1,000 which Watt had incurred in prosecuting his project

up to that time, and also to provide the means of prosecuting

further experiments, as well as to secure a patent for the engine.

In return for this outlay Roebuck was to have two-thirds of the

property in the invention. Early in 1768 Watt made trial of a

new and larger model, with a cylinder of seven or eight inches

diameter. But the result was not very satisfactory. "By

an unforeseen misfortune," he wrote to Roebuck, "the mercury found

its way into the cylinder, and played the devil with the solder.

This throws us back at least three days, and is very vexatious,

especially as it happened in spite of the precautions I had taken to

prevent it." Roebuck, becoming impatient, urged Watt to meet

him to talk the matter over; and suggested that as Watt could not

come as far as Carron, they should meet at Kilsyth, about fifteen

miles from Glasgow. Watt replied, saying he was too unwell to

be able to ride so far, and that his health was such that the

journey would disable him from doing anything for three or four days

after. But he went on with his experiments, patching up his

engine, and endeavouring to get it into working condition.

After about a month's labour he at last succeeded to his heart's

content; and he at once communicated the news to his partner,

intimating his intention of at last paying his long-promised visit

to Roebuck at Kinneil. "I sincerely wish you joy of this

successful result," he said, "and hope it will make some return for

the obligations I owe you."

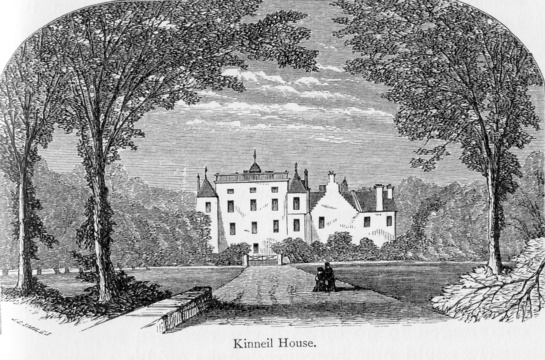

Kinneil House, to which Watt hastened to pay his visit of

congratulation to Dr. Roebuck, is an old-fashioned building,

somewhat resembling an old French chateau. It was a former

country-seat of the Dukes of Hamilton, and is finely situated on the

shores of the Frith of Forth. The mansion is rich in classical

associations, having been inhabited, since Roebuck's time, by Dugald

Stewart, who wrote in it his 'Philosophy of the Human Mind.'

There he was visited by Wilkie, the painter, when in search of

subjects for his pictures; and Dugald Stewart found for him, in an

old farmhouse in the neighbourhood, the cradle-chimney introduced in

the "Penny Wedding." But none of these names can stand by the

side of that of Watt; and the first thought at Kinneil, of every one

who is familiar with his history, would be of the memorable day when

he rode over in exultation to wish Dr. Roebuck joy of the success of

the steam-engine. His note of triumph was, however, premature.

He had yet to suffer many sickening delays and bitter

disappointments; for, though he had contrived to get his model

executed with fair precision, the skill was still wanting to

manufacture the parts of their full size with the requisite unity;

and his present elation was consequently doomed to be succeeded by

repeated discomfiture.

The model went on so well, however, that it was determined at

once to take out a patent for the engine. The first step was

to secure its provisional protection, and with that object Watt went

to Berwick-upon-Tweed, and made a declaration before a Master in

Chancery of the nature of the invention. In August, 1768, we

find him in London on the business of the patent. He became

utterly wearied with the delays interposed by sluggish officialism,

and disgusted with the heavy fees which he was required to pay in

order to protect his invention. He wrote home to his wife at

Glasgow in a very desponding mood. Knowing her husband's

diffidence and modesty, but having the fullest confidence in his

genius, she replied, "I beg that you will not make yourself uneasy,

though things should not succeed to your wish. If it [the

condensing engine] will not do, something else will; never

despair." Watt must have felt cheered by these brave words

of his noble helpmate, and encouraged to go onward cheerfully in

hope.

He could not, however, shake off his recurring fits of

despondency, and on his return to Glasgow we find him occasionally

in very low spirits. Though his head was full of his engine,

his heart ached with anxiety for his family, who could not be

maintained on hope, already so long deferred. The more

sanguine Roebuck was elated with the good working of the model, and

impatient to bring the invention into practice. He wrote Watt

in October, 1768, "You are now letting the most active part of your

life insensibly glide away. A day, a moment, ought not to be

lost. And you should not suffer your thoughts to be diverted

by any other object, or even improvement of this, but only the

speediest and most effectual manner of executing an engine of a

proper size, according to your present ideas."

Watt, however, felt that his invention was capable of many

improvements, and he was never done introducing new expedients.

He proceeded, in the intervals of leisure which he could spare from

his surveying business, to complete the details of the drawings and

specification,—making various trials of pipe-condensers,

plate-condensers, and drum-condensers,—contriving steam-jackets to

prevent the waste of heat and new methods for securing greater

tightness of the piston,—inventing condenser-pumps, oil-pumps,

gauge-pumps, exhausting-cylinders, loading-valves, double cylinders,

beams, and cranks. All these contrivances had to be thought

out and tested, elaborately and painfully, amidst many failures and

disappointments; and Dr. Roebuck began to fear that the fresh

expedients which were always starting up in Watt's brain would

endlessly protract the consummation of the invention. Watt, on

his part, felt that he could only bring the engine nearer to

perfection by never resting satisfied with imperfect devices, and

hence he left no means untried to overcome the many practical

defects in it of which he was so conscious. Long after, when a

noble lord was expressing to him the admiration with which he

regarded his great achievement, Watt replied: "The public only look

at my success, and not at the intermediate failures and uncouth

constructions which have served me as so many steps to climb to the

top of the ladder."

As to the lethargy from which Roebuck sought to raise Watt,

it was merely the temporary reaction of a mind strained and wearied

with long-continued application to a single subject, and from which

it seemed to be occasionally on the point of breaking down

altogether. To his intimate friends, Watt bemoaned his many

failures, his low spirits, his bad health, and his sleepless nights.

He wrote to his friend Dr. Small [p.111]

in January, 1769, "I have many things I could talk to you about—much

contrived, and little executed. How much would good health and

spirits be worth to me!" A month later he wrote, "I am still

plagued with head-aches, and sometimes heart-aches."

It is nevertheless a remarkable proof of Watt's indefatigable

perseverance in his favourite pursuit, that at this very time, when

apparently sunk in the depths of gloom, he learnt German for the

purpose of getting at the contents of a curious book, the

Theatrum Machinarum of Leupold, which just then fell into his

hands, and contained an account of the machines, furnaces, methods

of working, profits, &c., of the mines in the Upper Hartz. His

instructor in the language was a Swiss dyer, settled in Glasgow.

With the like object of gaining access to untranslated books in

French and Italian—then the great depositories of mechanical and

engineering knowledge—Watt had already mastered both these

languages.

In preparing his specification, Watt viewed the subject in

all its bearings. The production of power by steam is a very

large one, but Watt grasped it thoroughly. The insight with

which he searched, analysed, arranged, and even provided for future

modifications, was the true insight of genius. He seems with

an almost prophetic eye to have seen all that steam was capable of

accomplishing. This is well illustrated by his early plan of

working steam expansively by cutting it off at about half-stroke,

thereby greatly economising its use; as well as by his proposal to

employ high-pressure steam where cold water could not be used for

purposes of condensation. [p.111]

The careful and elaborate manner in which he studied the

specification, and the consideration which he gave to each of its

various details, are clear from his correspondence with Dr. Small,

which is peculiarly interesting, as showing Watt's mind actively

engaged in the very process of invention. At length the

necessary specification and drawings were completed and lodged early

in 1769,—a year also memorable as that in which Arkwright took out

the patent for his spinning-machine.

In order to master thoroughly the details of the ordinary

Newcomen engine, and to ascertain the extent of its capabilities as

well as of its imperfections, Watt undertook the erection of several

engines of this construction; and during his residence at Kinneil

took charge of the Schoolyard engine near Boroughstoness, in order

that he might thereby acquire a full practical knowledge of its

working. Mr. Hart, in his interesting 'Reminiscences of James

Watt,' gives the following account. "My late brother had

learned from an old man who had been a workman at Dr. Roebuck's

coal-works when Mr. Watt was there, that he had erected a small

engine on a pit they called Taylor's Pitt. The workman could

not remember what kind of engine it was, but it was the

fastest-going one he ever saw. From its size, and from its

being placed in a small timber-house, the colliers called it the

'Box Bed.' We thought it likely to have been the first of the

patent engines made by Mr. Watt, and took the opportunity of

mentioning this to him at our interview. He said he had

erected that engine, but he did not wish at the time to venture on a

patent one until he had a little more experience."

At length he proceeded to erect the trial-engine after his

new patent, and made arrangements to stay at Kinneil until the work

was finished. It had been originally intended to erect it in

the little town of Boroughstoness; but as prying eyes might have

watched his proceedings there, and as he wished to avoid display,

being determined, as he said, "not to puff," he fixed upon an

outhouse behind Kinneil, close by the burnside in the glen, where

there was abundance of water and secure privacy. The materials

were brought to the place, partly from Watt's small works at

Glasgow, and partly from Carron, where the cylinder—of eighteen

inches diameter and five feet stroke—had been cast and a few workmen

were placed at his disposal.

The process of erection was very tedious, owing

to the clumsiness of the mechanics employed on the job. Watt

was occasionally compelled to be absent on other business, and on

his return he usually found the men at a standstill, not knowing

what to do next. As the engine neared completion, his "anxiety

for his approaching doom" kept him sleepless at nights; for his

fears were more than equal to his hopes. He was easily cast

down by little obstructions, and especially discouraged by

unforeseen expense. Roebuck, on the contrary, was hopeful and

energetic, and often took occasion to rally the other on his

despondency under difficulties, and his almost painful want of

confidence in himself. Roebuck was, doubtless, of much service

to Watt in encouraging him to proceed with his invention, and also

in suggesting some important modifications in the construction of

the engine. It is probable, indeed, that, but for his help,

Watt could not have gone on. Robison says, "I remember Mrs.

Roebuck remarking one evening, 'Jamie is a queer lad, and, without

the Doctor, his invention would have been lost; but Dr. Roebuck

won't let it perish.'"

The new engine, on which Watt had expended so much labour,

anxiety, and ingenuity, was completed in September, 1759, about six

months after the date of its commencement. But its success was

far from decided. Watt himself declared it to be "a clumsy

job." His new arrangement of the pipe-condenser did not work

well; and the cylinder, having been badly cast, was found almost

useless. One of his greatest difficulties consisted in keeping

the piston tight. He wrapped it round with cork, oiled rags,

tow, old hat, paper, horse-dung, and other things, but still there

were open spaces left, sufficient to let the air in and the steam

out. Watt was grievously depressed by his want of success, and

he had serious thoughts of giving up the thing altogether.

Before abandoning it, however, the engine was again thoroughly

overhauled, many improvements were introduced in it, and a new trial

was made of its powers. But this did not prove more successful

than the earlier ones had been. "You cannot conceive," he

wrote to Small, "how mortified I am with this disappointment.

It is a damned thing for a man to have his all hanging by a single

string. If I had wherewithal to pay the loss, I don't think I

should so much fear a failure but I cannot bear the thought of other

people becoming losers by my schemes; and I have the happy

disposition of always painting the worst."

Watt was therefore bound to prosecute his project by honour,

not less than by interest; and summoning up his courage, he went on

with it anew. He continued to have the same confidence as ever

in the principles of his engine: where it broke down, it was in

workmanship. Could mechanics but be found capable of

accurately executing its several parts, he believed that its success

was certain. But no such mechanics were to be found at Carron.

By this time Roebuck was becoming embarrassed with debt, and

involved in various difficulties. The pits were drowned with

water, which no existing machinery could pump out, and ruin

threatened to overtake him before Watt's engine could come to his

help. He had sunk in the coalmine, not only his own fortune,

but much of the property of his relatives; and he was so straitened

for money that he was unable to defray the cost of taking out the

patent according to the terms of his engagement, and Watt had

accordingly to borrow the necessary money from his never-failing

friend, Dr. Black. He was thus adding to his own debts,

without any clearer prospect before him of ultimate relief. No

wonder that he should, after his apparently fruitless labour,

express to Small his belief that, "of all things in life, there is

nothing more foolish than inventing." The unhappy state of his

mind may be further inferred from his lamentation expressed to the

same friend on the 31st of January, 1770. "To-day," said he,

"I enter the thirty-fifth year of my life, and I think I have hardly

yet done thirty-five pence worth of good in the world; but I cannot

help it."

Notwithstanding the failure of his engine thus far, and the

repeated resolution expressed to Small that he would invent no more,

leading, as inventing did, only to vexation, failure, loss, and

increase of headache, Watt could not control his irrepressible

instinct to invent; and whether the result might be profitable or

not, his mind went on as before,—working, scheming, and speculating.

Thus, at different times in the course of his correspondence with

Small, who was a man of a like ingenious turn of mind, we find him

communicating various new things, "gimcracks," as he termed them,

which he had contrived.

He was equally ready to contrive a cure for smoky chimneys, a

canal sluice for economising water, a method of determining "the

force necessary to dredge up a cubic foot of mud from any given

depth of water," and a means of "clearing the observed distance of

the moon from any given star of the effects of refraction and

parallax"; illustrating his views by rapid but graphic designs

embodied in the text of his letters to Small and other

correspondents.

One of his minor inventions was a new method of readily

measuring distances by means of a telescope. [p.116]

At the same time he was occupied in making experiments on kaolin,

with the intention of introducing the manufacture of porcelain in

the pottery work on the Broomielaw, of which he was a partner.

He was also concerned with Dr. Black and Dr. Roebuck in pursuing

experiments with the view of decomposing sea-salt by lime, and

thereby obtaining alkali for purposes of commerce. A patent

for the process was taken out by Dr. Roebuck, but eventually proved

a failure, like most of his other projects. We also find Watt

inventing a muffling furnace for melting metals, and sending the

drawings to Mr. Boulton at Birmingham for trial.

At other times he was occupied with Chaillet, the Swiss dyer,

experimenting on various chemical substances; corresponding with Dr.

Black as to the new fluoric or spar acid; and at another time making

experiments to ascertain the heats at which water boils at every

inch of mercury from vacuum to air. Later we find him

inventing a prismatic micrometer for measuring distances, which he

described in considerable detail in his letters to Small. [p.117]

At the same time he was busy inventing and constructing a new

surveying quadrant by reflection, and making improvements in

barometers and hygrometers. "I should like to know," he wrote

to Small, "the principles of your barometer; De Luc's

hygrometer is nonsense. Probavi." Another of his

contrivances was his dividing screw, for dividing an inch accurately

into 1,000 equal parts. He states that he found this screw

exceedingly useful, as it saved him much needless compass-work, and,

moreover, enabled him to divide lines into the ordinates of any

curve whatsoever.

Such were the multifarious pursuits in which this

indefatigable student and enquirer was engaged; all tending to

cultivate his mind and advance his education, but comparatively

unproductive as regarded his pecuniary returns. So

unfortunate, indeed, had Watt's speculations proved, that his friend

Dr. Hutton, of Edinburgh, addressed to him a New Year's Day letter,

with the object of dissuading him from proceeding further with his

unprofitable, brain-distressing work. "A happy new year to

you!" said Hutton; "may it be fertile to you in lucky events, but no

new inventions!" He went on to say that invention was only for

those who live by the public, and those who from pride chose to

leave a legacy to the public. It was not a thing likely to be

well paid for, under a system where the rule was, to be the best

paid for the work that was easiest done. It was of no use,

however, telling Watt that he must not invent. One might as

well have told Burns that he was not to sing because it would not

pay, or Wilkie that he was not to paint, or Hutton himself that he

was not to think and speculate as to the hidden operations of

nature. To invent was the natural and habitual operation of

Watt's intellect, and he could not restrain it.

Watt had already been too long occupied with this profitless

work: his money was all gone; he was in debt; and it behoved him to

turn to some other employment by which he might provide for the

indispensable wants of his family. Having now given up the

instrument-making business, he confined himself almost entirely to

surveying. Amongst his earliest surveys was one of a coal

canal from Monkland to Glasgow, in 1769; and the Act authorising its

construction was obtained in the following year. Watt was

invited to superintend the execution of the works, and he had

accordingly to elect whether he would go on with the engine

experiments, the event of which was doubtful, or embrace an

honourable and perhaps profitable employment, attended with much

less risk and uncertainty. His necessities decided him.

"I had," he said, "a wife and children, and saw myself growing grey

without having any settled way of providing for them." He

accordingly accepted the appointment offered him by the directors of

the canal, and undertook to superintend the construction of the

works at a salary of £200 a year. At the same time he

determined not to drop the engine, but to proceed with it at such

leisure moments as he could command.

The Monkland Canal was a small concern, and Watt had to

undertake a variety of duties. He acted at the same time as

surveyor, superintendent, engineer, and treasurer, assisted only by

a clerk. But the appointment proved useful to him. The

salary he earned placed his family above want, and the out-doors

life he was required to lead improved his health and spirits.

After a few months he wrote Dr. Small that he found himself more

strong, more resolute, less lazy, and less confused than when he

began the occupation. His pecuniary affairs were also more

promising. "Supposing the engine to stand good for itself," he

said, "I am able to pay all my debts and some little thing more, so

that I hope in time to be on a par with the world."

But there was a dark side to the picture. His

occupation exposed him to fatigue, vexation, hunger, wet, and cold.

Then the quiet and secluded habits of his early life did not fit him

for the out-door work of the engineer. He was timid and

reserved, and had nothing of the navvy in his nature. He had

neither the roughness of tongue nor stiffness of back to enable him

to deal with rude butty gangs. He was nervously fearful lest

his want of practical experience should betray him into scrapes, and

lead to impositions on the part of his workmen. He hated

higgling, and declared that he would rather "face a loaded cannon

than settle an account or make a bargain." He had been

"cheated," he said, "by undertakers, and was unlucky enough to know

it."

Watt continued to act as engineer for the Monkland Canal

Company for about a year and a half, during which he was employed in

other engineering works. Among these was a survey of the River

Clyde, with a view to the improvement of the navigation. Watt

sent in his report; but no steps were taken to carry out his

suggestions until several years later, when the beginning was made

of a series of improvements, which have resulted in the conversion

of the Clyde from a pleasant trouting and salmon stream into one of

the busiest navigable highways in the world.

Among Watt's other labours about the same period may be

mentioned his survey of a canal between Perth and Cupar Angus,

through Strathmore; of the Crinan Canal, afterwards carried out by

Rennie; and other projects in the western highlands. The

Strathmore Canal survey was conducted at the instance of the

Commissioners of Forfeited Estates. It was forty miles long,

through a very rough country. Watt set out to make it in

September, 1770, and was accompanied by snowstorms during almost the

entire survey. He suffered severely from the cold: the winds swept

down from the Grampians with fury, and chilled him to the bone. The

making of this survey occupied him forty-three days, and the

remuneration he received for it was only eighty pounds, which

included expenses.

The small pay of engineers at that time may be further

illustrated by the fee paid him in the same year for supplying the

magistrates of Hamilton with a design for the proposed new bridge

over the Clyde at that town. It was originally intended to

employ Mr. Smeaton; but as his charge was ten pounds, which was

thought too high, Watt was employed in his stead. After the

Act of 1770 had been obtained, the Burgh minutes record that Baillie

Naismith was appointed to proceed to Glasgow to see Mr. Watt on the

subject of a design, and his charge being only £7. 7s., he was

requested to supply it accordingly. "I have lately," wrote

Watt to Small, "made a plan and estimate of a bridge over our River

Clyde, eight miles above this: it is to be of five arches and 220

feet waterway, founded upon piles on a muddy bottom." The

bridge, after Watt's plan, was begun in 1771, but it was not

finished until 1780.

About the same time Watt prepared plans of docks and piers at

Port Glasgow, and of a new harbour at Ayr. The Port Glasgow

works were carried out, but those at Ayr were postponed. When

Rennie came to examine the design for the improvement of the Ayr

navigation, of which the new harbour formed part, he took objections

to it, principally because of the parallelism of the piers, and

another plan was eventually adopted. Watt's principal

engineering job, and the last of the kind on which he was engaged in

Scotland, was a survey of the Caledonian Canal, long afterwards

carried out by Telford. The survey was made in the autumn of

1773, through a country without roads. "An incessant rain,"

said he, "kept me for three days as wet as water could make me; I

could hardly preserve my journal book."

In the midst of this dreary work Watt was summoned to Glasgow

by the intelligence which reached him of the illness of his wife;

and when he reached home he found that she had died in childbed. [p.123]

Of all the heavy blows he had suffered, he felt this to be the

worst. His wife had struggled with him through poverty.

She had often cheered his fainting spirit when borne down by doubt,

perplexity and disappointment; and now she had died, without being

able to share in his good fortune as she had shared his adversity.

For some time after, when about to enter his humble dwelling, he

would pause on the threshold, unable to summon courage to enter the

room where he was never more to meet "the comfort of his life."

"Yet this misfortune," he wrote to Small, "might have fallen upon me

when I had less ability to bear it, and my poor children might have

been left suppliants to the mercy of the wide world."

Watt tried to forget his sorrow, as was his custom, in

increased application to work, though the recovery of the elasticity

of his mind was in a measure beyond the power of his will.

There were at that time very few bright spots in his life. A

combination of unfortunate circumstances threatened to overwhelm

him. No further progress had yet been made with his

steam-engine, which indeed he almost cursed as the cause of his

misfortunes. Dr. Roebuck's embarrassments had reached their

climax. He had fought against the water which drowned his coal

until he could fight no more, and he was at last delivered into the

hands of his creditors a ruined man. "My heart bleeds for

him," said Watt, "but I can do nothing to help him. I have

stuck by him, indeed, till I have hurt myself."

But the darkest hour is nearest the dawn. Watt had

passed through a long night, and a gleam of sunshine at last beamed

upon him. Matthew Boulton, of Birmingham, was about to take up

the invention on which Watt had expended so many of the best years

of his life; and the turning-point in Watt's fortunes had at last

arrived.

――――♦―――― |