|

"Good friend, for Jesus sake forbeare".

Hull's epitaph

to, and inscribed on the tomb of

William Billington |

|

|

Details of

George Hull's life are sparse. Although several writers have left

biographic sketches, they drawn mainly on a single source, an appraisal of

Hull's poetry written by the Lancashire poet Joseph Baron and published in The Blackburn Times

in 1902.

|

|

|

|

|

(1863-1933) |

Baron tell us that

GEORGE

HULL was born at 38, Eanam, Blackburn on May 10th, 1863,

to Alice (née Atkinson) and John Hull, a coal merchant.

His younger days were spent mostly in the countryside, for when

he was one year old his parents removed to Hoghton and from there to Croston.

|

O, the little thatched cot in the nook,

Where the willow bent over the stream;

Where I played the bright day

Of my childhood away,

That has passed like a Paradise-dream!

O, this earth like an Eden did seem,

On which angels in rapture might look,

To the gaze of the child,

Still by sin undefiled,

In that little thatched cot in the nook.

From....The

Little Thatched Cot in the Nook |

At Croston, George attended a dame school, an early form of a

private elementary school usually taught by a women ("dame") and often

located within her home.

Some six years later, the family returned to Blackburn where

George continued his education, first at St. Ann's, King Street, and

later at

St. Mary's, Islington, which, with other evidence—not least his poetry—suggests strongly that George was from a Roman Catholic family.

On leaving school George began a varied

career. He first found work in an architect's office; then

as clerk to an

engineer; as clerk to a brass founder; in an unknown capacity to a builder; and as engrossing clerk to a solicitor,

work in which

George

remained for eight years. In 1891, he entered his father's

coal business, where Baron records him working in 1902, but without stating

whether this was 'at the coal face'—weighing out the black nuggets at the railway

company's coal sidings, loading up the coal-wagon, and humping the

hundredweight sacks to customers'

coal-holes (in all weathers)—or whether the business was of sufficient extent to permit George to

exercise his managerial skills at head office.

|

When the mind broods in silence o'er days that are gone,

And remembrance is burdened with pain,

In the breast of the sluggard dark sorrow lives on,

For his will never strives with its chain:

But the artisan feels, 'mid the whirl of his wheels,

That joy which life's cares cannot spoil;

And with blithe heart he sings, as the loud hammer rings,

Of the grief-slaying pleasures of toil.

From....The

Pleasures of Toil |

Up to this date, Census returns (to 1901) supplemented by Hull's poetry allow a little more

flesh to be added to Baron's skeletal account. The 1871

Census shows the Hull family—John, aged 38, a "Cotton Cloth Looker";

Alice, aged 34, ditto; George, aged 7; James, aged 3; and William (aged 10

months) — to be domiciled at 74 Dean St., Saint Peter,

Blackburn, together with Charles Pickup, a "boarder" and by occupation a Railway Goods Porter. Ten

years later,

George had acquired two more siblings, John, aged 8; and Alice, aged 5,

while John Hull, now employed as a "Clerk" — as is George — had become

a widower. James is described as a "Brass Finisher Apprentice"

and William (aged 10) a "Scholar and Half Timer in Cotton Mill" (half the day at school and half in working in the mill), which

suggests that the family were not well off and that every

member was required to contribute to its exchequer. Charles

Pickup the boarder had by now been replaced by John Hull's

sister-in-law, Mary Atkinson, in the role of "House Keeper." Moving

on 10 years finds George, himself now a widower and by occupation a "Solictors'

Clerk Law", living with his mother-in-law, Sarah Bolton and her

extended family at 259 Hoghton Lane,

Walton-le-Dale, then a village to

the south of the River Ribble near Preston. In the daily experience

of our Victorian forebears, Death lurked just around the corner. Hull tells us in his poetry that his first marriage was

short-lived; the Ballad of

Lily-Mary suggests that his wife died in childbirth and, in a

postscript, that their baby soon followed its mother;

The Angel Bride adds further

detail.

In the 1901 Census return,

George (now aged 37) is shown still resident at Walton-le-Dale but now remarried—to

Mary (aged 30)—and the father

of three sons, John, aged 5; William, aged 3 and Wilfred aged 10 months,

both of whom were later to survive a trip to hospital (Two

Little Wills Away and To a

Hospital Nurse). George

describes his occupation as "Coal Merchant and Journalist on own

account." Maybe a daughter then arrived (To

Mary Winifried) and either she, or perhaps

another daughter — but not

Sweet Hannah — reached adulthood

. . . .

|

The Old House is still there to greet us, Mary, mine!

And our darling Daughter waits by the door;

While her rosy little children come to meet us, Mary, mine,

We'll return to the City never more!

We'll see the old faces—Time still spares a few,

Thanking Heaven, that has brought us again

In our life's afternoon, morning joys to renew

In our Old Home in bonnie Hoghton Lane.

From....The

Old Home |

Sometime after 1901,

George's career took another change in direction; in her "Lancashire Anthology"

(1923), May Yates describes his occupation as "Lancashire Representative to Messrs.

Burns, Oates & Washbourne, Ltd.", a firm of London publishers,

particularly of Roman Catholic literature. In the following year, John Randal Swann, in his

"Lancashire Authors", states that Hull continued to live at Walton-le-Dale.

A final entry then appears in G. H. Whittacker's "A Lancashire Garland" of

1933, which merely records George Hull's death on February 21st of that year.

|

|

I' th' daytime factory chimblies belch

Their smook i' mony a street,

There's drunken fooak an' railway trains

As rowl abeawt o neet.

There's childer thin, that's never seen

The bonny brids an' trees;

Their faces look so white for want

O' th' healthy country breeze.

From...A

Country Life for Me |

|

|

Two views of George Hull's birthplace, the Eanam area of Blackburn as it

was ca.

1930.

Photographs by kind permission of

Blackburn & Darwin Community History. |

There is more substance in the record of Hull's literary legacy, for,

in addition to his output reproduced in these pages, Baron and other

writers provide some historical context. Baron records (in "North

Country Poets," 1889) that Hull "was not at all aware that he possessed

the gift of song until he was in his 'late teens;' but the perusal of

Longfellow's poems, and the charming prose romance "Hyperion," settled the

matter beyond doubt, for he set to work at once, and poem after poem was

despatched to different magazines." Baron goes on to say that George's first verse appeared in Facts and Fancies

(ca. 1883)

followed by a considerable quantity of devotional verse which was

published in The Lamp, a Roman Catholic magazine. George also

contributed to Manchester,

Preston, Blackburn and other newspapers, including a series

entitled "Cracks bi th' Winter Fire" published in the Lancashire

Evening Post, "Lyrics of Lancashire" and

other stories in dialect published in the Preston Guardian. He was

also joint author with Cornelius McManus of a small volume of rather

sentimental "Tales from

the Ribble Valley".

Swann records that "on the occasion of the King's visit to Lancashire in

1913, Mr. Hull won the prize offered by the Daily Mail for the best

poem of welcome in the dialect", "Yo're Welcome, King George an'

Queen Mary".

|

Yo're welcome, King George an' Queen Mary,

As welcome as flowers i' May;

Frae factory, frae foundry, frae dairy,

We're creawdin' to meet yo' to-day.

Frae th' owd folk that greet yo' quite staidly

To th' childer that's dancin' wi' glee,

We're o fain to welcome yo' gradely—

We're o fain yo'r faces to see.

From....Yo're

Welcome |

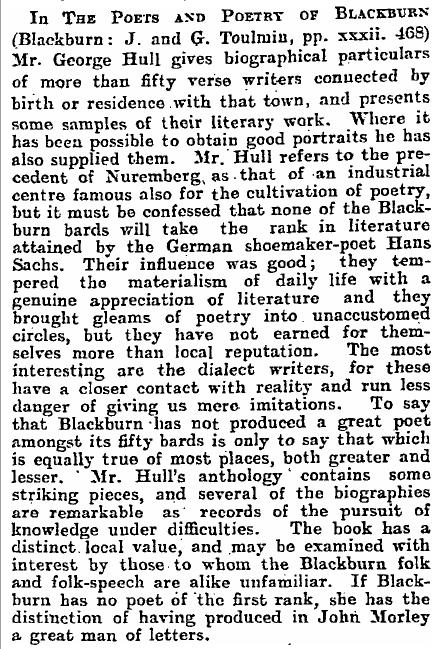

Hull's first published poetry collection appeared in 1894

under the title of "The Heroes of the Heart, and other Lyrical Poems."

This was followed in 1902 by "The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn

(1793-1902)", published by

subscription and a volume about which Baron

was enthusiastic. Writing in the Blackburn Times, he described

Hull's important anthology as

one that will remain "a monument to his industry and skill, and be

treasured by all interested in local poetry," while in G. H. Whittacker's

view, expressed some thirty years later, it comprises "a well compiled

feast of biography, with copious poetic examples, which show that not

only has Blackburn been exceptionally well blessed with poets, but also

that their output has been remarkable in quality." "The Poets and

Poetry of Blackburn" is indeed a monument to Hull's industry and skill,

to which the many photographic portraits of the poets that grace his

cameos add historical interest. Thus, the Manchester Guardian's

surprisingly parochial view of Hull's 'Poets' (from the days before the

Internet led to Blackburn's ― and, indeed, Lancashire's ― poets and

poetry acquiring wider than

"local value") . . . .

The Guardian, 3rd Feb., 1903.

In 1922, Hull's complete poetical works appeared under

the title "English Lyrics and

Lancashire Songs", some three dozen of his poems ― arguably the

best in the collection ― being in the

Lancashire dialect.

|

|

|

Poet's Corner, the humble beer-house at the corner of

Nab Lane and Bradshaw Street, which played so

important a part in Victorian Blackburn's literary life, for it was here

that both the town's and visiting poets gathered under the aegis of 'mine host',

William Billington. Among the habitues were

John Critchley Prince, Richard

Dugdale, Thomas Chippendale, Ralph Ditchfield, Clemesha, Yates,

Jardine and many others that appear in George Hull's

anthology of Blackburn poets.

Photograph by kind permission of

Blackburn & Darwin Community History. |

|

WILLIAM BILLINGTON.

(January 3rd, 1884.)

The Singer hath departed, and no more

Is heard his voice, so strong and clear and sweet,

Cheering the crowds in factory and in street,

With melody, as in the days of yore.

His was a master-mind; and 'twill be long

Before old Blackburn, through the smoke and gloom

That gather round the busy lathe and loom,

Will see another half so bright in song.

He needs no lays to blazon forth his name,—

His own will bear it o'er the sea of time!

Yet I, a Child of Song, to whom he came

With friendship true and counsel most sublime,

Would to his memory dedicate this stave,

And lay my simple wreath upon his grave. |

Hull's plain English poetry can be uncomfortably sentimental

and is much coloured — even spoiled — by his continual expression of religious

belief, in which lies a strong suggestion that the only route to eternal

salvation for the practitioners of "heresey" (or "false teaching") lies in

their returning to the "Church

of Old England". . . . .

|

I hold

the one faith of the Church of Old England—

That Church which belonged to both England and Rome—

The faith of King Alfred and Becket and Langton,

The glory for ages of our native home.

From...."Two

Noble Brothers"

_________ |

|

And with

us are united the sons of that Isle

That would never to heresy bend,

But was leal to the core through the dark days of yore

When 'twas death the old faith to defend.

.

.

.

.

.

.

And when England and Ireland are one in the

Faith—

The sweet hope through my heart sends a thrill—

While the bells are still rung, holy Mass shall be sung

Both above and below the dear hill!

From....The

Little Church under the Hill

_________ |

|

Saint Augustine! by thy spreading

Of the faith on England's shore,

We, thy children now beseech thee

Look upon our land once more.

Wicked men from Truth have torn her,

England that was Mary's Dower;

Now no more thy voice may warn her

When false teaching wields its power.

From...Saint Augustine of

England |

In his analysis, Joseph Baron links Hull's tendency to religious

expression to the

influence of the Victorian poetess Adelaide Anne

Procter, a convert to Roman Catholicism with an even stronger penchant for writing devotional verse.

As Baron puts it, "nothing

spasmodic, nothing

sensational; just enough of the religious element not to repel the student

of secular poetry". . . . but I think, only just. |

|

OUR LADY OF BLACKBURN. |

ADELAIDE ANNE PROCTER. |

|

*

*

*

* *

The ancient Church of Blackburn—

My own good honest Town—

From days of Saint Augustine

Came sweetly, proudly down:

And oft did dear Paulinus—

Not far from this our home—

Preach that same Faith, in England,

Which Peter preached at Rome.

The Church of Thee, Saint Mary,

Arose in Blackburn Town;

And from its Lady-Altar

Thine image, with its crown,

Looked on our own forefathers

Who age by age knelt there

To seek through thy own Jesus

The wondrous aid of prayer.

When I first knew my Blackburn—

A tiny studious boy—

The Tower of Old Saint Mary's

To my young heart gave joy.

The ancient Church had vanished,

Thy Shrine had passed away;

Yet that old dedication

Remains to this our day.

Magnificat is chanted

Each peaceful Sabbath morn

In many a Church at Blackburn—

Brave Town where I was born.

By long-divided Christians

Thy name is honoured yet,

O! never may my Townsmen

Thy wondrous life forget.

A second sweet 'Saint Mary's'

Arose not far away,

Where gentle Father Richard

For England used to pray.

The faithful sons of Ireland

Oft gathered with us there,—

By one glad Faith united,—

To conquer Sin and Care.

*

*

*

* * |

Sweet Poetess! though all too brief thy stay

With us on earth, "True Honours" grace thy lyre—

"The Angel's Story" lives to raise us higher;

"The Peace of God" consoles us day by day.

We read thy "Legends" with rapt hearts, and say,

"O Heaven itself did this pure verse inspire,

That it might be to us a beacon fire

In life's dark night to show the 'narrow way.'"

The true love of "the Faithful Soul" was thine,

Thou didst not "fear the beautiful Angel Death":

"Give me thy heart," said Christ the Lord; and thou

Meekly and gladly yielding up thy breath,

Didst pass from earthly pain to peace divine,

With Song's immortal crown upon thy brow.

____________________

FAITH.

There came an Angel-King to dwell with men:

He gained allegiance through celestial things,

And 'neath the shadow of his mighty wings

The peace of Eden drew near earth again.

Souls, Godlike, traversed every mount and glen

Of changing life, with hearts that knew not fear,

Their hopes were great, their aims were high and

clear,

Their lowliest lives had noble features then.

But O, if life waxed strong beneath his sway,

Far stronger death! for then the Angel strode

With lifted sword by each true

pilgrim's side,

And smote the demons by the darkling road;

Then threw the gates of Heaven open

wide,

And God's own smile became eternal day! |

|

As a poet Hull's redeeming virtue lies in his verse in the

Lancashire dialect.

In Baron's view, "excellent as are Hull's poems in book

English, it is in his dialect work that we see him at his best, and there

chiefly because of his love for the country and country folks." I

leave readers to judge. . . . |

|

LANCASHIRE FUN.

When the leet fades away at the closin' o' day,

An' toilin' an' scrapin' are done,

It's merry an' sweet wi' mi true mates to meet

For an heawr or two's Lancashire fun.

They sit reawnd yon fire, an' their tongues never tire,

As they tell o' th' wild marlocks they played

When youth's merry days seet their spirits ablaze,

An' they'd never known friendship to fade.

O! there's a sooarts o' wit, but there's nowt as con hit

The breet spot i' this grey heyd o' mine

Like a crack or a song i' eawr Lancashire tongue,

For id raises owd mem'ries so fine.

An' th' breet days ov owd, when mi heart wer so bowd

An' aw only knew sorrow bi name,

Seem as fresh an' as clear as the smiles aw meet here

When aw coom mi owd cronies to claim.

Then aw'll tooast yo', mi lads, may yo'r sons—

like ther

dads—

Still be merry, straight-farrad, an' true;

For a bit o' gay chaff, or a reet hearty laugh,

Nayther horts a wise mon nor a foo'.

An' as years rowl along, may, they join in a song

Otogether when toilin' is done,

Wi' their hearts just as leet, as yo'r own are to-neet,

Through an heawr or two's Lancashire fun!

______________

BILLY AN' BETTY.

Said Billy to Betty, "Tha's getten drest up,

Wheerever are ta beawn?"

Said Betty, "Aw'm off for a two-o'-thre' things

That aw want frae up i' th' teawn.

Thi tay's o ready—it's just fresh brewed—

There's a bit o' tooasted cheese;

Tha'rt tired, aw con see; but as for me,

Aw con do wi' a walk i' th' breeze.

"Is there owt as tha wants for thisel', mi lad?"

"Well," Billy said, "reight enough,

Though t' Government's gooin' economy mad,

Aw could do wi' a penn'o'th o' snuff.

But th' pappers is preychin' economy too,

They'd tighten us up to an inch;

It's mony a day sin' aw'd gradely pay,

Will t' times affooard a pinch?"

Said Bet, wi' a laugh—hoo wer fond of her chaff,

Though her heart were kind an' tender

"Just keawr thee i' t' nook, wi' thi papper an' book,

An' tooast thi tooas o' t' fender;

But, as for thi snuff, it's nasty stuff,

An' tha knows aw often feel

If tha'd tickle thi nooase wi' a wisp o' straw

Id would answer just as weel."

______________ |

TH' OWD GATE DEAWN AT TH' END

OF EAWR FOWD.

They tell me this wauld's allus changin',

I' th' country as weel as i' th' teawn,

An' owd Slater said th' last day were comin'

When his pair o' hand looms were poo'd

deawn.

To-day I could welly believe him,—

For they say, neaw as th' heawses are sowd,

As they're beawn to cut deawn th' garden

hedges

An' poo' deawn th' owd gate i' eawr fowd.

It's t' wo'st news I've heeard for a twelve-

month,

An' it's med mo feel fifty year' owd,

Though it's bod abeawt twelve sin' I were

swingin'

On th' gate deawn at th' end of eawr fowd.

Yo' may think I'm quite silly for frettin'

O'er sich a quare thing as a gate;

But id carries owd time on id' hinges

As id swings to an' fro' soon an' late.

I remember mi good-hearted fayther

Peearkt mo onto id mony a time,

When I waur but a wee merry lassie,

An' I laughed as he sung an' owd rhyme:

For th' happiest days o' mi childhood,

When the waurld were ne'er gloomy an'

cowd,

Were spent swingin' back'ard an' forrad

On th' gate deawn at th' end of eawr fowd.

An' then O heaw weel I remember

Heaw mi heart leapt wi' love pure an'

sweet,

When i' t' middle o' bonny September,

Young Charlie coom cooartin' one neet!

Heaw he towd mo th' owd stooary so tender,

An' begged mo to help him through life;

Heaw he said for twelve months he'd bin

longin'

To mek mo his own little wife!

I s' ne'er i' this lifetime forget id,—

Heaw sweetly that love tale were towd,

As we stood when th' owd sun were just

settin'

Bi th' gate deawn at th' end of eawr fowd.

We were wed when o t' spring birds were

singin'

An' t' fleawrs were just buddin' on t' trees,

An' t' bells o' th' owd church, gaily ringin',

Towd th' stooary to' t' sweet mornin'

breeze.

An' then we walked hooam to th' owd

cottage,

An' t' merriment started for t' day;

They were dancin' till welly next mornin',

T' lads an' lasses were never so gay.

But Charlie an' me into t' moonleet

Crept eawt—mon an' wife!—an' still

vowed

To be cooarters for ever an' ever

Bi th' gate deawn at th' end of eawr fowd!

Sin' then, as I've said, there's bin changes,—

Mi fayther went Hooam to his rest,

An' t' best mother soon followed after

As e'er held a child to her breast.

But I've still Charlie here, an' mi childer—

Two rooases—a lass an' a lad;

An' I'm sure, tekkin' life otogether;

We'n nod so mich cause to be sad;

For true love can drive away sorrow

Far better nor silver an' gowd;

So I'll keep a leet heart for to-morrow,

Though I'm loysin' th' owd gate i' eawr

fowd!

______________ |

George Hull's other

poems in the Lancashire Dialect.

<>

|