|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER V

"That handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give:

She was a charmer, and could almost read

The thoughts of people."—Othello. |

"THAT gipsy woman who

is coming with her cart," said the parrot, "is a fairy too, and very

malicious. It was she and others of her tribe who caught us and put

us into these cages, for they are more powerful than we. Mind you do

not let her allure you into the woods, nor wheedle you or frighten you

into giving her any of those fairies."

"No," said Jack; "I will not."

"She sold us to the brown people," continued the parrot.

"Mind you do not buy anything of her, for your money in her palm would act

as a charm against you."

"She has a baby," observed the parrot-wife, scornfully.

"Yes, a baby," repeated the old parrot; "and I hope by means

of that baby to get her driven away, and perhaps get free myself. I

shall try to put her in a passion. Here she comes."

There she was indeed, almost close at hand. She had a

little cart; her goods were hung all about it, and a small horse drew it

slowly on, and stopped when she got a customer.

Several gipsy children were with her, and as the people came

running together over the grass to see her goods, she sang a curious kind

of song, which made them wish to buy them.

Jack turned from the parrot's cage as she came up. He

had heard her singing a little way off, and now, before she began again,

he felt that already her searching eyes had found him out, and taken

notice that he was different from the other people.

When she began to sing her selling song, he felt a most

curious sensation. He felt as if there were some cobwebs before his

face, and he put up his hand as if to clear them away. There were no

real cobwebs, of course; and yet he again felt as if they floated from the

gipsy-woman to him, like gossamer threads, and attracted him towards her.

So he gazed at her, and she at him, till Jack began to forget how the

parrot had warned him.

He saw her baby too, wondered whether it was heavy for her to

carry, and wished he could help her. I mean, he saw that she had a

baby on her arm. It was wrapped in a shawl, and had a handkerchief

over its face. She seemed very fond of it, for she kept hushing it;

and Jack softly moved nearer and nearer to the cart, till the gipsy-woman

smiled, and suddenly began to sing:

|

"My good man—he's an old, old man—

And my good man got a fall,

To buy me a bargain so fast he ran

When he heard the gipsies call:

'Buy,

buy brushes,

Baskets

wrought o' rushes.

Buy

them, buy them, take them, try them,

Buy, dames all.'

"My old man, he has money and land,

And a young, young wife am I.

Let him put the penny in my white hand

When he hears the gipsies cry:

'Buy, buy laces,

Veils to screen your faces.

Buy them, buy them, take and

try them,

Buy, maids, buy.'" |

When the gipsy had finished her song, Jack felt as if he was

covered all over with cobwebs; but he could not move away, and he did not

mind them now. All his wish was to please her, and get close to her;

so when she said, in a soft wheedling voice, "What will you please to buy,

my pretty gentleman?" he was just going to answer that he would buy

anything she recommended, when, to his astonishment and displeasure, for

he thought it very rude, the parrot suddenly burst into a violent fit of

coughing, which made all the customers stare. "That's to clear my

throat," he said, in a most impertinent tone of voice; and then he began

to beat time with his foot, and sing, or rather scream out, an extremely

saucy imitation of the gipsy's song, and all his parrot friends in the

other cages joined in the chorus.

|

"My fair lady's a dear, dear lady—

I walked by her side to woo.

In a garden alley, so sweet and shady,

She answered, 'I love not you,

John,

John Brady,'

Quoth

my dear lady,

'Pray now, pray now, go your way now,

Do,

John, do!' " |

At first the gipsy did not seem to know where that mocking

song came from, but when she discovered that it was her prisoner, the old

parrot, who was thus daring to imitate her, she stood silent and glared at

him, and her face was almost white with rage.

When he came to the end of the verse he pretended to burst

into a violent fit of sobbing and crying, and screeched out to his wife,

"Mate! mate! hand up my handkerchief. Oh! oh! it's so affecting,

this song is."

Upon this the other parrot pulled Jack's handkerchief from

under her wing, hobbled up, and began, with a great show of zeal, to wipe

his horny beak with it. But this was too much for the gipsy; she

took a large brush from her cart, and flung it at the cage with all her

might.

This set it violently swinging backwards and forwards, but

did not stop the parrot, who screeched out, "How delightful it is to be

swung!" And then he began to sing another verse in the most impudent

tone possible, and with a voice that seemed to ring through Jack's head,

and almost pierce it.

|

"Yet my fair lady's my own, own lady,

For I passed another day;

While making her moan, she sat all alone,

And thus and thus did she say:

'John, John Brady,'

Quoth my dear lady,

'Do now, do now, once more woo now,

Pray, John, pray!' " |

"It's beautiful!" screeched the parrot-wife, "and so ap-pro-pri-ate."

Jack was delighted when she managed slowly to say this long word with her

black tongue, and he burst out laughing. In the meantime a good many

of the brown people came running together, attracted by the noise of the

parrots and the rage of the gipsy, who flung at his cage, one after the

other, all the largest things she had in her cart. But nothing did

the parrot any harm; the more violently his cage swung, the louder he

sang, till at last the wicked gipsy seized her poor little young baby, who

was lying in her arms, rushed frantically at the cage as it flew swiftly

through the air towards her, and struck at it with the little creature's

head. "Oh, you cruel, cruel woman!" cried Jack, and all the small

mothers who were standing near with their skinny children on their

shoulders screamed out with terror and indignation; but only for one

instant, for the handkerchief flew off that had covered its face, and was

caught in the wires of the cage, and all the people saw that it was not a

real baby at all, but a bundle of clothes, and its head was a turnip.

Yes, a turnip! You could see that as plainly as

possible, for though the green leaves had been cut off, their stalks were

visible through the lace cap that had been tied on it.

Upon this all the crowd pressed closer, throwing her baskets,

and brushes, and laces, and beads at the gipsy, and calling out, "We will

have none of your goods, you false woman! Give us back our money, or

we will drive you out of the fair. You've stuck a stick into a

turnip, and dressed it up in baby clothes. You're a cheat! a cheat!

"

"My sweet gentlemen, my kind ladies," began the gipsy; but

baskets and brushes flew at her so fast that she was obliged to sit down

on the grass and hold up the sham baby to screen her face.

While this was going on, Jack felt that the cobwebs which had

seemed to float about his face were all gone; he did not care at all any

more about the gipsy, and began to watch the parrots with great attention.

He observed that when the handkerchief stuck between the cage

wires, the parrots caught it, and drew it inside; and then Jack saw the

cunning old bird himself lay it on the floor, fold it crosswise like a

shawl, and put it on his wife.

Then she jumped upon the perch, and held it with one foot,

looking precisely like an old lady with a parrot's head. Then he

folded Jack's handkerchief in the same way, put it on, and got upon the

perch beside his wife, screaming out, in his most piercing tone:

"I like shawls; they're so becoming." Now the gipsy did

not care at all what those inferior people thought of her, and she was

calmly counting out their money, to return it; but she was very desirous

to make Jack forget her behaviour, and had begun to smile again, and tell

him she had only been joking, when the parrot spoke, and, looking up, she

saw the two birds sitting side by side, and the parrot-wife was screaming

in her mate's ear, though neither of them was at all deaf:

"If Jack lets her allure him into the woods, he'll never come

out again. She'll hang him up in a cage, as she did us. I say,

how does my shawl fit?"

So saying, the parrot-wife whisked herself round on the

perch, and lo! in the corner of the handkerchief were seen some curious

letters, marked in red. When the crowd saw these, they drew a little

farther off, and glanced at one another with alarm.

"You look charming, my dear; it fits well!" screamed the old

parrot in answer. "A word in your ear, 'Share and share alike' is a

fine motto."

"What do you mean by all this?" said the gipsy, rising, and

going with slow steps to the cage, and speaking cautiously.

"Jack," said the parrot, "do they ever eat handkerchiefs in

your part of the country?"

"No, never," answered Jack.

"Hold your tongue and be reasonable," said the gipsy,

trembling. "What do you want? I'll do it, whatever it is."

"But do they never pick out the marks?" continued the parrot.

"O Jack! are you sure they never pick out the marks?"

"The marks?" said Jack, considering. "Yes, perhaps they

do."

"Stop!" cried the gipsy, as the old parrot made a peck at the

strange letters. "Oh! you're hurting me. What do you want?

I say again, tell me what you want, and you shall have it."

"We want to get out," replied the parrot; "you must undo the

spell."

"Then give me my handkerchief," answered the gipsy, "to

bandage my eyes. I dare not say the words with my eyes open.

You had no business to steal it. It was woven by human hands, so

that nobody can see through it; and if you don't give it to me, you'll

never get out—no, never!"

"Then," said the old parrot, tossing his shawl off, "you may

have Jack's handkerchief; it will bandage your eyes just as well. It

was woven over the water, as yours was."

"It won't do!" cried the gipsy in terror; "give me my own."

"I tell you," answered the parrot, "that you shall have

Jack's handkerchief; you can do no harm with that."

By this time the parrots all around had become perfectly

silent, and none of the people ventured to say a word, for they feared the

malice of the gipsy. She was trembling dreadfully, and her dark

eyes, which had been so bright and piercing, had become dull and almost

dim; but when she found there was no help for it, she said:

"Well, pass out Jack's handkerchief. I will set you

free if you will bring out mine with you."

"Share and share alike," answered the parrot; "you must let

all my friends out too."

"Then I won't let you out," answered the gipsy. "You

shall come out first, and give me my handkerchief, or not one of their

cages will I undo. So take your choice."

"My friends, then," answered the brave old parrot; and he

poked Jack's handkerchief out to her through the wires.

The wondering crowd stood by to look, and the gipsy bandaged

her eyes tightly with the handkerchief; and then, stooping low, she began

to murmur something and clap her hands—softly at first, but by degrees

more and more violently. The noise was meant to drown the words she

muttered; but as she went on clapping, the bottom of cage after cage fell

clattering down. Out flew the parrots by hundreds, screaming and

congratulating one another; and there was such a deafening din that not

only the sound of her spell but the clapping of her hands was quite lost

in it.

But all this time Jack was very busy; for the moment the

gipsy had tied up her eyes, the old parrot snatched the real handkerchief

off his wife's shoulders, and tied it round her neck. Then she

pushed out her head through the wires, and the old parrot called to Jack,

and said, "Pull!"

Jack took the ends of the handkerchief, pulled terribly hard,

and stopped. "Go on! go on!" screamed the old parrot.

"I shall pull her head off," cried Jack.

"No matter;" cried the parrot; "no matter—only pull."

Well, Jack did pull, and he actually did pull her head off!

nearly tumbling backward himself as he did it; but he saw what the whole

thing meant then, for there was another head inside—a fairy's head.

Jack flung down the old parrot's head and great beak, for he

saw that what he had to do was to clear the fairy of its parrot covering.

The poor little creature seemed nearly dead, it was so terribly squeezed

in the wires. It had a green gown or robe on, with an ermine collar;

and Jack got hold of this dress, stripped the fairy out of the parrot

feathers, and dragged her through—velvet robe, and crimson girdle, and

little yellow shoes. She was very much exhausted, but a kind brown

woman took her instantly, and laid her in her bosom. She was a

splendid little creature, about half a foot long.

"There's a brave boy!" cried the parrot. Jack glanced

round, and saw that not all the parrots were free yet, the gipsy was still

muttering her spell.

He returned the handkerchief to the parrot, who put it round

his own neck, and again Jack pulled. But oh! what a tough old parrot

that was, and how Jack tugged before his cunning head would come off!

It did, however, at last; and just as a fine fairy was pulled through,

leaving his parrot skin and the handkerchief behind him, the gipsy untied

her eyes, and saw what Jack had done.

"Give me my handkerchief!" she screamed in despair.

"It's in the cage, gipsy," answered Jack; "you can get it

yourself. Say your words again."

But the gipsy's spell would only open places where she had

confined fairies, and no fairies were in the cage now.

"No, no, no!" she screamed; "too late! Hide me! O

good people, hide me!"

But it was indeed too late. The parrots had been

wheeling in the air, hundreds and hundreds of them, high above her head;

and as she ceased speaking, she fell shuddering on the ground, drew her

cloak over her face, and down they came, swooping in one immense flock,

and settled so thickly all over her that she was completely covered; from

her shoes to her head not an atom of her was to be seen.

All the people stood gravely looking on. So did Jack,

but he could not see much for the fluttering of the parrots, nor hear

anything for their screaming voices; but at last he made one of the cross

people hear when he shouted to her, "What are they going to do to the poor

gipsy?"

"Make her take her other form," she replied; "and then she

cannot hurt us while she stays in our country. She is a fairy, as we

have just found out, and all fairies have two forms."

"Oh!" said Jack; but he had no time for more questions.

The screaming, and fighting, and tossing about of little bits

of cloth and cotton ceased; a black lump heaved itself up from the ground

among the parrots; and as they flew aside, an ugly great condor, with a

bare neck, spread out its wings, and, skimming the ground, sailed slowly

away.

"They have pecked her so that she can hardly rise," exclaimed

the parrot fairy. "Set me on your shoulder, Jack, and let me see the

end of it."

Jack set him there; and his little wife, who had recovered

herself, sprang from her friend the brown woman, and sat on the other

shoulder. He then ran on—the tribe of brown people, and mushroom

people, and the feather-coated folks running too—after the great black

bird, who skimmed slowly on before them till she got to the gipsy carts,

when out rushed the gipsies, armed with poles, milking-stools, spades, and

everything they could get hold of to beat back the people and the parrots

from hunting their relation, who had folded her tired wings, and was

skulking under a cart, with ruffled feathers and a scowling eye.

Jack was so frightened at the violent way in which the

gipsies and the other tribes were knocking each other about, that he ran

off, thinking he had seen enough of such a dangerous country.

As he passed the place where that evil-minded gipsy had been

changed, he found the ground strewed with little bits of her clothes.

Many parrots were picking them up, and poking them into the cage where the

handkerchief was; and presently another parrot came with a lighted brand,

which she had pulled from one of the gipsies' fires.

"That's right," said the fairy on Jack's shoulder, when he

saw his friend push the brand between the wires of what had been his cage,

and set the gipsy's handkerchief on fire, and all the bits of her clothes

with it. "She won't find much of herself here," he observed, as Jack

went on. "It will not be very easy to put herself together again."

So Jack moved away. He was tired of the noise and

confusion; and the sun was just setting as he reached the little creek

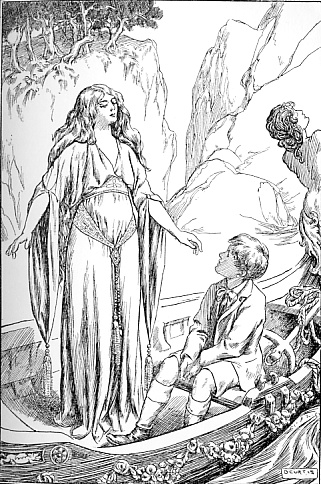

where his boat lay.

Then the parrot fairy and his wife sprang down, and kissed

their hands to him as he stepped on board, and pushed the boat off.

He saw, when he looked back, that a great fight was still going on; so he

was glad to get away, and he wished his two friends good-bye, and set off,

the old parrot fairy calling after him, "My relations have put some of our

favourite food on board for you." Then they again thanked him for

his good help, and sprang into a tree, and the boat began to go down the

wonderful river.

"This has been a most extraordinary day," thought Jack; "the

strangest day I have had yet." And after he had eaten a good supper

of what the parrots had brought, he felt so tired and sleepy that he lay

down in the boat, and presently fell fast asleep. His fairies were

sound asleep too in his pockets, and nothing happened of the least

consequence; so he slept comfortably till morning.

A great fight was still going on.

_______________

CHAPTER VI

|

" 'Master,' quoth the auld hound,

'Where will ye go?'

'Over moss, over muir,

To court my new jo.'

'Master, though the night be merk,

I'se follow through the snow.

" 'Court her, master, court her,

So shall ye do weel;

But and ben she'll guide the house,

I'se get milk and meal.

Ye'se get lilting while she sits

With her rock and reel.'

" 'For, oh! she has a sweet tongue,

And een that look down,

A gold girdle for her waist,

And a purple gown.

She has a good word forbye

Fra a' folk in the town.' " |

SOON after sunrise they

came to a great city, and it was perfectly still. There were grand

towers and terraces, wharves, too, and a large market, but there was

nobody anywhere to be seen. Jack thought that might be because it

was so early in the morning; and when the boat ran itself up against a

wooden wharf and stopped, he jumped ashore, for he thought this must be

the end of his journey. A delightful town it was, if only there had

been any people in it! The market-place was full of stalls, on which

were spread toys, baskets, fruit, butter, vegetables, and all the other

things that are usually sold in a market.

Jack walked about in it. Then he looked in at the open

doors of the houses, and at last, finding that they were all empty, he

walked into one, looked at the rooms, examined the picture-books, rang the

bells, and set the musical-boxes going. Then, after he had shouted a

good deal, and tried in vain to make some one hear, he went back to the

edge of the river where his boat was lying, and the water was so

delightfully clear and calm, that he thought he would bathe. So he

took off his clothes, and folding them very carefully, so as not to hurt

the fairies, laid them down beside a haycock, and went in, and ran about

and paddled for a long time much longer than there was any occasion for;

but then he had nothing to do.

When at last he had finished, he ran to the haycock, and

began to dress himself; but he could not find his stockings, and after

looking about for some time he was obliged to put on his clothes without

them, and he was going to put his boots on his bare feet, when, walking to

the other side of the haycock, he saw a little old woman about as large as

himself. She had a pair of spectacles on, and she was knitting.

She looked so sweet tempered that Jack asked her if she knew

anything about his stockings. "It will be time enough to ask for

them when you have had your breakfast," said she. "Sit down.

Welcome to our town. How do you like it?"

"I should like it very much indeed," said Jack, "if there was

anybody in it."

"I'm glad of that," said the woman. "You've seen a good

deal of it; but it pleases me to find that you are a very honest boy.

You did not take anything at all. I am honest too."

"Yes," said Jack, "of course you are."

"And as I am pleased with you for being honest," continued

the little woman, "I shall give you some breakfast out of my basket."

So she took out a saucer full of honey, a roll of bread, and a cup of

milk.

"Thank you," said Jack, "but I am not a beggar-boy; I have

got a half-crown, a shilling, a sixpence, and two pence; so I can buy this

breakfast of you, if you like. You look very poor."

"Do I?" said the little woman, softly; and she went on

knitting, and Jack began to eat the breakfast.

"I wonder what has become of my stockings," said Jack.

"You will never see them any more," said the old woman.

"I threw them into the river, and they floated away."

"Why did you?" asked Jack.

The little woman took no notice; but presently she had

finished a beautiful pair of stockings, and she handed them to Jack, and

said:

"Is that like the pair you lost?"

"Oh no," said Jack, "these are much more beautiful stockings

than mine."

"Do you like them as well?" asked the fairy woman.

"I like them much better," said Jack, putting them on.

"How clever you are!" "Would you like to wear these," said the

woman, "instead of yours?"

She gave Jack such a strange look when she said this, that he

was afraid to take them, and answered:

"I shouldn't like to wear them if you think I had better

not."

"Well," she answered, "I am very honest, as I told you; and

therefore I am obliged to say that if I were you I would not wear those

stockings on any account."

"Why not?" said Jack; for she looked so sweet tempered that

he could not help trusting her.

"Why not?" repeated the fairy; "why, because when you have

those stockings on, your feet belong to me."

"Oh!" said Jack. "Well, if you think that matters, I'll

take them off again. Do you think it matters?"

"Yes," said the fairy woman; "it matters, because I am a

slave, and my master can make me do whatever he pleases, for I am

completely in his power. So, if he found out that I had knitted

those stockings for you, he would make me order you to walk into his

mill—the mill which grinds the corn for the town; and there you would have

to grind and grind till I got free again."

When Jack heard this, he pulled off the beautiful stockings,

and laid them on the old woman's lap. Upon this she burst out

crying, as if her heart would break.

"If my fairies that I have in my pocket would only wake,"

said Jack, "I would fight your master; for if he is no bigger than you

are, perhaps I could beat him, and get you away."

"No, Jack," said the little woman; "that would be of no use.

The only thing you could do would be to buy me; for my cruel master has

said that if ever I am late again he shall sell me in the slave-market to

the brown people, who work underground. And, though I am dreadfully

afraid of my master, I mean to be late to-day, in hopes (as you are kind,

and as you have some money) that you will come to the slave-market and buy

me. Can you buy me, Jack, to be your slave?"

"I don't want a slave," said Jack; "and, besides, I have

hardly any money to buy you with."

"But it is real money," said the fairy woman, "not like what

my master has. His money has to be made every week, for if there

comes a hot day it cracks, so it never has time to look old, as your

half-crown does; and that is how we know the real money, for we cannot

imitate anything that is old. Oh, now, now it is twelve o'clock! now

I am late again! and though I said I would do it, I am so frightened!"

So saying, the little woman ran off towards the town,

wringing her hands, and Jack ran beside her.

"How am I to find your master?" he said.

"O Jack, buy me! buy me!" cried the fairy woman. "You

will find me in the slave- market. Bid high for me. Go back

and put your boots on, and bid high."

Now Jack had nothing on his feet, so he left the poor little

woman to run into the town by herself, and went back to put his boots on.

They were very uncomfortable, as he had no stockings; but he did not much

mind that, and he counted his money. There was the half-crown that

his grandmamma had given him on his birthday, there was a shilling, a

sixpence, and two pence, besides a silver fourpenny-piece which he had

forgotten. He then marched into the town; and now it was quite full

of people—all of them little men and women about his own height.

They thought he was somebody of consequence, and they called out to him to

buy their goods. And he bought some stockings, and said, "What I

want to buy now is a slave."

So they showed him the way to the slave-market, and there

whole rows of odd-looking little people were sitting, while in front of

them stood the slaves.

Now Jack had observed as he came along how very disrespectful

the dogs of that town were to the people. They had a habit of going

up to them and smelling at their legs, and even gnawing their feet as they

sat before the little tables selling their wares; and what made this more

surprising was that the people did not always seem to find out when they

were being gnawed. But the moment the dogs saw Jack they came and

fawned on him, and two old hounds followed him all the way to the

slave-market; and when he took a seat one of them laid down at his feet,

and said, "Master, set your handsome feet on my back, that they may be out

of the dust."

"Don't be afraid of him," said the other hound; "he won't

gnaw your feet. He knows well enough that they are real ones."

"Are the other people's feet not real?" asked Jack.

"Of course not," said the hound. "They had a feud long

ago with the fairies, and they all went one night into a great cornfield

which belonged to these enemies of theirs, intending to steal the corn.

So they made themselves invisible, as they are always obliged to do till

twelve o'clock at noon; but before morning dawn, the wheat being quite

ripe, down came the fairies with their sickles, surrounded the field, and

cut the corn. So all their legs of course got cut off with it, for

when they are invisible they cannot stir. Ever since that they have

been obliged to make their legs of wood."

While the hound was telling this story Jack looked about, but

he did not see one slave who was in the least like his poor little friend,

and he was beginning to be afraid that he should not find her, when he

heard two people talking together.

"Good day!" said one. "So you have sold that

good-for-nothing slave of yours?"

"Yes," answered a very cross-looking old man. "She was

late again this morning, and came to me crying and praying to be forgiven;

but I was determined to make an example of her, so I sold her at once to

Clink-of-the-Hole, and he has just driven her away to work in his mine."

Jack, on hearing this, whispered to the hound at his feet,

"If you will guide me to Clink's hole, you shall be my dog."

"Master, I will do my best," answered the hound; and he stole

softly out of the market, Jack following him.

"Master, I will do my best," answered the hound.

_______________

|

"So useful it is to have money, heigh ho!

So useful it is to have money!"

A. H. CLOUGH. |

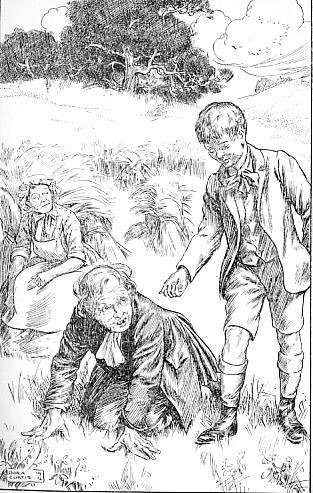

THE old hound went

straight through the town, smelling Clink's footsteps, till he came into a

large field of barley; and there, sitting against a sheaf, for it was

harvest time, they found Clink-of-the-Hole. He was a very ugly

little brown man, and he was smoking a pipe in the shade; while crouched

near him was the poor little woman, with her hands spread before her face.

"Good day, sir," said Clink to Jack. "You are a

stranger here, no doubt?"

"Yes," said Jack; "I only arrived this morning."

"Have you seen the town?" asked Clink, civilly; "there is a

very fine market."

"Yes, I have seen the market," answered Jack. "I went

into it to buy a slave, but I did not see one that I liked."

"Ah!" said Clink; "and yet they had some very fine articles."

Here he pointed to the poor little woman, and said, "Now that's a useful

body enough, and I had her very cheap."

"What did you give for her?" said Jack, sitting down.

"Three pitchers," said Clink, "and fifteen cups and saucers,

and two shillings in the money of the town."

"Is their money like this?" said Jack, taking out his

shilling.

When Clink saw the shilling he changed colour, and said, very

earnestly, "Where did you get that, dear sir?"

"Oh, it was given me," said Jack, carelessly.

Clink looked hard at the shilling, and so did the fairy

woman, and Jack let them look some time, for he amused himself with

throwing it up several times and catching it. At last he put it back

in his pocket, and then Clink heaved a deep sigh. Then Jack took out

a penny, and began to toss that up, upon which, to his great surprise, the

little brown man fell on his knees, and said, "Oh, a shilling and a

penny—a shilling and a penny of mortal coin! What would I not give

for a shilling and a penny!"

"I don't believe you have got anything to give," said Jack,

cunningly; "I see nothing but that ring on your finger, and the old

woman."

"But I have a great many things at home, sir," said the brown

man, wiping his eyes; "and besides, that ring would be cheap at a

shilling—even a shilling of mortal coin."

"Would the slave be cheap at a penny?" said Jack.

"Would you give a penny for her, dear sir?" inquired Clink,

trembling with eagerness.

"She is honest," answered Jack; "ask her whether I had better

buy her with this penny."

"It does not matter what she says," replied the brown man; "I

would sell twenty such as she is for a penny—a real one."

"Ask her," repeated Jack; and the poor little woman wept

bitterly, but she said "No."

"Why not?" asked Jack; but she only hung down her head and

cried.

"I'll make you suffer for this," said the brown man.

But when Jack took out the shilling, and said, "Shall I buy you with this,

slave?" his eyes actually shot out sparks, he was so eager.

The little brown man fell on his knees and said,

"Oh, a shilling and a penny."

"Speak!" he said to the fairy woman; "and if you don't say

'Yes,' I'll strike you."

"He cannot buy me with that," answered the fairy woman,

"unless it is the most valuable coin he has got."

The brown man, on hearing this, rose up in a rage, and was

just going to strike her a terrible blow, when Jack cried out, "Stop!" and

took out his half-crown.

"Can I buy you with this?" said he; and the fairy woman

answered, "Yes."

Upon this Clink drew a long breath, and his eyes grew bigger

and bigger as he gazed at the half-crown.

"Shall she be my slave for ever, and not yours," said Jack,

"if I give you this?"

"She shall," said the brown man. And he made such a low

bow, as he took the money, that his head actually knocked the ground.

Then he jumped up; and, as if he was afraid Jack should repent of his

bargain, he ran off towards the hole in the hill with all his might,

shouting for joy as he went.

"Slave," said Jack, "that is a very ragged old apron that you

have got, and your gown is quite worn out. Don't you think we had

better spend my shilling in buying you some new clothes? You look so

very shabby."

"Do I?" said the fairy woman, gently. "Well, master,

you will do as you please."

"But you know better than I do," said Jack, "though you are

my slave."

"You had better give me the shilling, then," answered the

little old woman; "and then I advise you to go back to the boat, and wait

there till I come."

"What!" said Jack; "can you go all the way back into the town

again? I think you must be tired, for you know you are so very old."

The fairy woman laughed when Jack said this, and she had such

a sweet laugh that he loved to hear it; but she took the shilling, and

trudged off to the town, and he went back to the boat, his hound running

after him.

He was a long time going, for he ran a good many times after

butterflies, and then he climbed up several trees; and altogether he

amused himself for such a long while that when he reached the boat his

fairy woman was there before him. So he stepped on board, the hound

followed, and the boat immediately began to swim on.

"Why, you have not bought any new clothes!" said Jack to his

slave.

"No, master," answered the fairy woman; "but I have bought

what I wanted." And she took out of her pocket a little tiny piece

of purple ribbon, with a gold-coloured satin edge, and a very small

tortoiseshell comb.

When Jack saw these he was vexed, and said, "What do you mean

by being so silly? I can't scold you properly, because I don't know

what name to call you by, and I don't like to say 'Slave,' because that

sounds so rude. Why, this bit of ribbon is such a little bit that

it's of no use at all. It's not large enough even to make one mitten

of."

"Isn't it?" said the slave. "Just take hold of it,

master, and let us see if it will stretch."

So Jack did. And she pulled, and he pulled, and very

soon the silk had stretched till it was nearly as large as a handkerchief;

and then she shook it, and they pulled again. "This is very good

fun," said Jack; "why now it is as large as an apron."

"Master, do you know what you have done?"

So she shook it again, and gave it a twitch here and a pat

there; and then they pulled again, and the silk suddenly stretched so wide

that Jack was very nearly falling overboard. So Jack's slave pulled

off her ragged gown and apron, and put it on. It was a most

beautiful robe of purple silk, it had a gold border, and it just fitted

her.

"That will do," she said. And then she took out the

little tortoiseshell comb, pulled off her cap, and threw it into the

river. She had a little knot of soft grey hair, and she let it down,

and began to comb. And as she combed the hair got much longer and

thicker, till it fell in waves all about her throat. Then she combed

again, and it all turned gold colour, and came tumbling down to her waist;

and then she stood up in the boat, and combed once more, and shook out the

hair, and there was such a quantity that it reached down to her feet, and

she was so covered with it that you could not see one bit of her,

excepting her eyes, which peeped out, and looked bright and full of tears.

Then she began to gather up her lovely locks; and when she

had dried her eyes with them, she said, "Master, do you know what you have

done? look at me now!" So she threw back the hair from her face, and

it was a beautiful young face; and she looked so happy that Jack was glad

he had bought her with his half-crown—so glad that he could not help

crying, and the fair slave cried too; and then instantly the little

fairies woke, and sprang out of Jack's pockets. As they did so,

Jovinian cried out, "Madam, I am your most humble servant;" and Roxaletta

said, "I hope your Grace is well;" but the third got on Jack's knee, and

took hold of the buttons of his waistcoat, and when the lovely slave

looked at her, she hid her face and blushed with pretty childish shyness.

"These are fairies," said Jack's slave; "but what are you?"

"Jack kissed me," said the little thing; "and I want to sit

on his knee."

"Yes," said Jack, "I took them out, and laid them in a row,

to see if they were safe, and this one I kissed, because she looked such a

little dear."

"Was she not like the others, then?" asked the slave.

"Yes," said Jack; "but I liked her the best; she was my

favourite."

Now, the instant these three fairies sprang out of Jack's

pockets, they got very much larger; in fact, they became fully grown—that

is to say, they measured exactly one foot one inch in height, which, as

most people know, is exactly the proper height for fairies of that tribe.

The two who had sprung out first were very beautifully dressed. One

had a green velvet coat, and a sword, the hilt of which was encrusted with

diamonds. The second had a white spangled robe, and the loveliest

rubies and emeralds round her neck and in her hair; but the third, the one

who sat on Jack's knee, had a white frock and a blue sash on. She

had soft, fat arms, and a face just like that of a sweet little child.

When Jack's slave saw this, she took the little creature on

her knee, and said to her, "How comes it that you are not like your

companions?"

And she answered, in a pretty lisping voice, "It's because

Jack kissed me."

"Even so it must be," answered the slave; "the love of a

mortal works changes indeed. It is not often that we win anything so

precious. Here, master, let her sit on your knee sometimes, and take

care of her, for she cannot now take the same care of herself that others

of her race are capable of."

So Jack let little Mopsa sit on his knee; and when he was

tired of admiring his slave, and wondering at the respect with which the

other two fairies treated her, and at their cleverness in getting

water-lilies for her, and fanning her with feathers, he curled himself up

in the bottom of the boat with his own little favourite, and taught her

how to play at cat's-cradle.

When they had been playing some time, and Mopsa was getting

quite clever at the game, the lovely slave said, "Master, it is a long

time since you spoke to me."

"And yet," said Jack, "there is something that I particularly

want to ask you about."

"Ask it, then," she replied.

"I don't like to have a slave," answered Jack; "and as you

are so clever, don't you think you can find out how to be free again?"

"I am very glad you asked me about that," said the fairy

woman. "Yes, master, I wish very much to be free; and as you were so

kind as to give the most valuable piece of real money you possessed in

order to buy me, I can be free if you can think of anything that you

really like better than that half-crown, and if I can give it you."

"Oh, there are many things," said Jack. "I like going up this

river to Fairyland much better."

"But you are going there, master," said the fairy woman; "you

were on the way before I met with you."

"I like this little child better," said Jack; "I love this

little Mopsa. I should like her to belong to me."

"She is yours," answered the fairy woman; "she belongs to you

already. Think of something else."

Jack thought again, and was so long about it that at last the

beautiful slave said to him, "Master, do you see those purple mountains?"

Jack turned round in the boat, and saw a splendid range of

purple mountains, going up and up. They were very great and steep,

each had a crown of snow, and the sky was very red behind them, for the

sun was going down.

"At the other side of those mountains is Fairyland," said the

slave; "but if you cannot think of something that you should like better

to have than your half-crown, I can never enter in. The river flows

straight up to yonder steep precipice, and there is a chasm in it which

pierces it, and through which the river runs down beneath, among the very

roots of the mountains, till it comes out at the other side.

Thousands and thousands of the small people will come when they see the

boat, each with a silken thread in his hand; but if there is a slave in

it, not all their strength and skill can tow it through. Look at

those rafts on the river; on them are the small people coming up."

Jack looked, and saw that the river was spotted with rafts,

on which were crowded brown fairy sailors, each one with three green

stripes on his sleeve, which looked like good-conduct marks. All

these sailors were chattering very fast, and the rafts were coming down to

meet the boat.

"All these sailors to tow my slave!" said Jack. "I

wonder, I do wonder, what you are?" But the fairy woman only smiled,

and Jack went on: "I have thought of something that I should like much

better than my half-crown. I should like to have a little tiny bit

of that purple gown of yours with the gold border."

Then the fairy woman said, "I thank you, master. Now I

can be free." So she told Jack to lend her his knife, and with it

she cut off a very small piece of the skirt of her robe, and gave it to

him. "Now mind," she said; "I advise you never to stretch this

unless you want to make some particular thing of it, for then it will only

stretch to the right size; but if you merely begin to pull it for your own

amusement, it will go on stretching and stretching, and I don't know where

it will stop."

_______________

|

"In the night she told a story,

In the night and all night through,

While the moon was in her glory,

And the branches dropped with dew.

"'Twas my life she told, and round it

Rose the years as from a deep;

In the world's great heart she found it,

Cradled like a child asleep.

"In the night I saw her weaving

By the misty moonbeam cold,

All the weft her shuttle cleaving

With a sacred thread of gold.

"Ah! she wept me tears of sorrow,

Lulling tears so mystic sweet;

Then she wove my last to-morrow,

And her web lay at my feet.

"Of my life she made the story:

I must weep—so soon 'twas told!

But your name did lend it glory,

And your love its thread of gold!" |

BY this time, as the

sun had gone down, and none of the moons had risen, it would have been

dark but that each of the rafts was rigged with a small mast that had a

lantern hung to it.

By the light of these lanterns Jack saw crowds of little

brown faces, and presently many rafts had come up to the boat, which was

now swimming very slowly. Every sailor in every raft fastened to the

boat's side a silken thread; then the rafts were rowed to shore, and the

sailors jumped out, and began to tow the boat along.

These crimson threads looked no stronger than the silk that

ladies sew with, yet by means of them the small people drew the boat along

merrily. There were so many of them that they looked like an army as

they marched in the light of the lanterns and torches. Jack thought

they were very happy, though the work was hard, for they shouted and sang.

The fairy woman looked more beautiful than ever now, and far

more stately. She had on a band of precious stones to bind back her

hair, and they shone so brightly in the night that her features could be

clearly seen.

Jack's little favourite was fast asleep, and the other two

fairies had flown away. He was beginning to feel rather sleepy

himself, when he was roused by the voice of his free lady, who said to

him, "Jack, there is no one listening now, so I will tell you my story.

I am the Fairy Queen!"

Jack opened his eyes very wide, but he was so much surprised

that he did not say a word. "One day, long, long ago," said the

Queen, "I was discontented with my own happy country. I wished to

see the world, so I set forth with a number of the one-foot-one fairies,

and went down the wonderful river, thinking to see the world.

"So we sailed down the river till we came to that town which

you know of; and there, in the very middle of the stream, stood a tower—a

tall tower built upon a rock.

"Fairies are afraid of nothing but of other fairies, and we

did not think this tower was fairy-work, so we left our ship and went up

the rock and into the tower, to see what it was like; but just as we had

descended into the dungeon keep, we heard the gurgling of water overhead,

and down came the tower. It was nothing but water enchanted into the

likeness of stone, and we all fell down with it into the very bed of the

river.

"Of course we were not drowned, but there we were obliged to

lie, for we have no power out of our own element; and the next day the

townspeople came down with a net and dragged the river, picked us all out

of the meshes, and made us slaves. The one-foot-one fairies got away

shortly; but from that day to this, in sorrow and distress, I have had to

serve my masters. Luckily, my crown had fallen off in the water, so

I was not known to be the Queen; but till you came, Jack, I had almost

forgotten that I had ever been happy and free, and I had hardly any hope

of getting away."

"How sorry your people must have been," said Jack, "when they

found you did not come home again."

"No," said the Queen; "they only went to sleep, and they will

not wake till to-morrow morning, when I pass in again. They will

think I have been absent for a day, and so will the applewoman. You

must not undeceive them; if you do, they will be very angry."

"And who is the applewoman?" inquired Jack; but the Queen

blushed, and pretended not to hear the question, so he repeated:

"Queen, who is the applewoman?"

"I've only had her for a very little while," said the Queen,

evasively.

"And how long do you think you have been a slave, Queen?"

asked Jack.

"I don't know," said the Queen. "I have never been able

to make up my mind about that."

And now all the moons began to shine, and all the trees

lighted themselves up, for almost every leaf had a glow-worm or a firefly

on it, and the water was full of fishes that had shining eyes. And

now they were close to the steep mountain side; and Jack looked and saw an

opening in it, into which the river ran. It was a kind of cave,

something like a long, long church with a vaulted roof, only the pavement

of it was that magic river, and a narrow towing-path ran on either side.

As they entered the cave there was a hollow murmuring sound,

and the Queen's crown became so bright that it lighted up the whole boat;

at the same time she began to tell Jack a wonderful story, which he liked

very much to hear, but every fresh thing she said he forgot what had gone

before; and at last, though he tried very hard to listen, he was obliged

to go to sleep; and he slept soundly and never dreamed of anything, till

it was morning.

He saw such a curious sight when he woke. They had been

going through this underground cavern all night, and now they were

approaching its opening on the other side. This opening, because

they were a good way from it yet, looked like a lovely little round window

of blue and yellow and green glass, but as they drew on he could see

far-off mountains, blue sky, and a country all covered with sunshine.

He heard singing too, such as fairies make; and he saw some

beautiful people, such as those fairies whom he had brought with him.

They were coming along the towing-path. They were all lady fairies;

but they were not very polite, for as each one came up she took a silken

rope out of a brown sailor's hand and gave him a shove which pushed him

into the water. In fact, the water became filled with such swarms of

these sailors that the boat could hardly get on. But the poor little

brown fellows did not seem to mind this conduct, for they plunged and

shook themselves about, scattering a good deal of spray. Then they

all suddenly dived, and when they came up again they were ducks—nothing

but brown ducks, I assure you, with green stripes on their wings; and with

a great deal of quacking and floundering they all began to swim back again

as fast as they could.

Then Jack was a good deal vexed, and he said to himself, "If

nobody thanks the ducks for towing us I will;" so he stood up in the boat

and shouted, "Thank you, ducks; we are very much obliged to you!"

But neither the Queen nor these new towers took the least notice, and

gradually the boat came out of that dim cave and entered Fairyland, while

the river became so narrow that you could hear the song of the towers

quite easily; those on the right bank sang the first verse, and those on

the left bank answered:

|

"Drop, drop from the leaves of lign aloes,

O honey-dew! drop from the tree.

Float up through your clear river shallows,

White lilies, beloved of the bee.

"Let the people, O Queen! say, and bless thee,

Her bounty drops soft as the dew,

And spotless in honour confess thee,

As lilies are spotless in hue.

"On the roof stands yon white stork awaking,

His feathers flush rosy the while,

For, lo! from the blushing east breaking,

The sun sheds the bloom of his smile.

"Let them boast of thy word, 'It is certain;

We doubt it no more,' let them say,

'Than to-morrow that night's dusky curtain

Shall roll back its folds for the day.'" |

"Master," whispered the old hound, who was lying at Jack's

feet.

"Well? " said Jack.

"They didn't invent that song themselves," said the hound;

"the old applewoman taught it to them—the woman whom they love because

she can make them cry."

Jack was rather ashamed of the hound's rudeness in saying

this; but the Queen took no notice. And now they had reached a

little landing-place, which ran out a few feet into the river, and was

strewed thickly with cowslips and violets.

Here the boat stopped, and the Queen rose and got out.

Jack watched her. A whole crowd of one-foot-one fairies

came down a garden to meet her, and he saw them conduct her to a beautiful

tent with golden poles and a silken covering; but nobody took the

slightest notice of him, or of little Mopsa, or of the hound, and after a

long silence the hound said, "Well, master, don't you feel hungry?

Why don't you go with the others and have some breakfast?"

"The Queen didn't invite me," said Jack. "But do you

feel as if you couldn't go?" asked the hound.

"Of course not," answered Jack; "but perhaps I may not."

"Oh, yes, master," replied the hound; "whatever you can do in

Fairyland you may do."

"Are you sure of that?" asked Jack.

"Quite sure, master," said the hound; "and I am hungry too."

"Well," said Jack, "I will go there and take Mopsa. She

shall ride on my shoulder; you may follow."

So he walked up that beautiful garden till he came to the

great tent. A banquet was going on inside. All the

one-foot-one fairies sat down the sides of the table, and at the top sat

the Queen on a larger chair; and there were two empty chairs, one on each

side of her.

Jack blushed; but the hound whispering again, "Master,

whatever you can do you may do," he came slowly up the table towards the

Queen, who was saying as he drew near, "Where is our trusty and

well-beloved the applewoman?" And she took no notice of Jack; so,

though he could not help feeling rather red and ashamed, he went and sat

in the chair beside her with Mopsa still on his shoulder. Mopsa

laughed for joy when she saw the feast. The Queen said, "O Jack, I

am so glad to see you!" and some of the one-foot-one fairies cried out,

"What a delightful little creature that is! She can laugh!

Perhaps she can also cry!"

Jack looked about, but there was no seat for Mopsa; and he

was afraid to let her run about on the floor, lest she should be hurt.

There was a very large dish standing before the Queen; for

though the people were small, the plates and dishes were exactly like

those we use, and of the same size.

This dish was raised on a foot, and filled with grapes and

peaches. Jack wondered at himself for doing it, but he saw no other

place for Mopsa; so he took out the fruit, laid it round the dish, and set

his own little one-foot-one in the dish.

Nobody looked in the least surprised; and there she sat very

happily, biting an apple with her small white teeth.

Then, as they brought him nothing to eat, Jack helped himself

from some of the dishes before him, and found that a fairy breakfast was

very nice indeed.

In the meantime there was a noise outside, and in stumped an

elderly woman. She had very thick boots on, a short gown of red

print, an orange cotton handkerchief over her shoulders, and a black silk

bonnet. She was exactly the same height as the Queen—for of course

nobody in Fairyland is allowed to be any bigger than the Queen; so, if

they are not children when they arrive, they are obliged to shrink.

"How are you, dear?" said the Queen.

"I am as well as can be expected," answered the

applewoman,

sitting down in the empty chair. "Now, then, where's my tea?

They're never ready with my cup of tea."

Two attendants immediately brought a cup of tea, and set it

down before the applewoman, with a plate of bread and butter; and she

proceeded to pour it out into the saucer, and blow it, because it was hot.

In so doing her wandering eyes caught sight of Jack and little Mopsa, and

she set down the saucer, and looked at them with attention.

Now Mopsa, I am sorry to say, was behaving so badly that Jack

was quite ashamed of her. First, she got out of her dish, took

something nice out of the Queen's plate with her fingers, and ate it; and

then, as she was going back, she tumbled over a melon, and upset a glass

of red wine, which she wiped up with her white frock; after which she got

into her dish again, and there she sat smiling, and daubing her pretty

face with a piece of buttered muffin.

"Mopsa," said Jack, "you are very naughty; if you behave in

this way, I shall never take you out to parties again."

"Pretty lamb!" said the applewoman; "it's just like a

child." And then she burst into tears, and exclaimed, sobbing, "It's

many a long day since I've seen a child. Oh dear! oh deary me!"

Upon this, to the astonishment of Jack, every one of the

guests began to cry and sob too.

"Oh dear! oh dear!" they said to one another, "we're crying;

we can cry just as well as men and women. Isn't it delightful?

What a luxury it is to cry, to be sure!"

They were evidently quite proud of it; and when Jack looked

at the Queen for an explanation, she only gave him a still little smile.

But Mopsa crept along the table to the applewoman, let her

take her and hug her, and seemed to like her very much; for as she sat on

her knee, she patted her brown face with a little dimpled hand.

"I should like vastly well to be her nurse," said the

applewoman, drying her eyes, and looking at Jack.

"If you'll always wash her, and put clean frocks on her, you

may," said Jack; "for just look at her—what a figure she is already!"

Upon this the applewoman laughed for joy, and again every

one else did the same. The fairies can only laugh and cry when they

see mortals do so.

"I should like vastly to be her nurse,"

said the applewoman. |

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)