|

MOPSA THE FAIRY

CHAPTER I

ABOVE THE CLOUDS

|

" 'And can this be my own world?

'Tis all gold and snow,

Save where scarlet waves are hurled

Down yon gulf below.'

' 'Tis thy world, 'tis my world,

City, mead, and shore,

For he that hath his own world

Hath many worlds more.' " |

A BOY, whom I knew very

well, was once going through a meadow, which was full of buttercups.

The nurse and his baby sister were with him; and when they got to an old

hawthorn, which grew in the hedge and was covered with blossom, they all

sat down in its shade; and the nurse took out three slices of plum-cake,

gave one to each of the children, and kept one for herself.

While the boy was eating, he observed that this hedge was

very high and thick, and that there was a great hollow in the trunk of the

old thorn-tree, and he heard a twittering, as if there was a nest

somewhere inside; so he thrust his head in, twisted himself round, and

looked up.

It was a very great thorn-tree, and the hollow was so large

that two or three boys could have stood upright in it; and when he got

used to the dim light in that brown, still place, he saw that a good way

above his head there was a nest—rather a curious one too, for it was as

large as a pair of blackbirds would have built—and yet it was made of fine

white wool and delicate bits of moss; in short, it was like a goldfinch's

nest magnified three times.

Just then he thought he heard some little voices cry, "Jack!

Jack!" His baby sister was asleep, and the nurse was reading a story

book, so it could not have been either of them who called. "I must

get in here," said the boy. "I wish this hole was larger." So

he began to wriggle and twist himself through, and just as he pulled in

his last foot, he looked up, and three heads which had been peeping over

the edge of the nest suddenly popped down again.

"Those heads had no beaks, I am sure," said Jack, and he

stood on tiptoe and poked in one of his fingers. "And the things

have no feathers," he continued; so, the hollow being rather rugged, he

managed to climb up and look in.

His eyes were not used yet to the dim light; but he was sure

those things were not birds—no. He poked them, and they took no

notice; but when he snatched one of them out of the nest, it gave a loud

squeak, and said, "O don't, Jack!" as plainly as possible, upon which he

was so frightened that he lost his footing, dropped the thing, and slipped

down himself. Luckily, he was not hurt, nor the thing either; he

could see it quite plainly now: it was creeping about like rather an old

baby, and had on a little frock and pinafore.

"It's a fairy! " exclaimed Jack to himself. "How

curious! and this must be a fairy's nest. Oh, how angry the old

mother will be if this little thing creeps away and gets out of the hole!"

So he looked down. "Oh, the hole is on the other side," he said; and

he turned round, but the hole was not on the other side; it was not on any

side; it must have closed up all on a sudden, while he was looking into

the nest, for, look whichever way he would, there was no hole at all,

excepting a very little one high up over the nest, which let in a very

small sunbeam.

Jack was very much astonished, but he went on eating his

cake, and was so delighted to see the young fairy climb up the side of the

hollow and scramble again into her nest, that he laughed heartily; upon

which all the nestlings popped up their heads, and, showing their pretty

white teeth, pointed at the slice of cake.

"Well," said Jack, "I may have to stay inside here for a long

time, and I have nothing to eat but this cake; however, your mouths are

very small, so you shall have a piece;" and he broke off a small piece,

and put it into the nest, climbing up to see them eat it.

These young fairies were a long time dividing and munching

the cake, and before they had finished, it began to be rather dark, for a

black cloud came over and covered the little sunbeam. At the same

time the wind rose, and rocked the boughs, and made the old tree creak and

tremble. Then there was thunder and rain, and the little fairies

were so frightened that they got out of the nest and crept into Jack's

pockets. One got into each waistcoat pocket, and the other two were

very comfortable, for he took out his handkerchief and made room for them

in the pocket of his jacket.

It got darker and darker, till at last Jack could only just

see the hole, and it seemed to be a very long way off. Every time he

looked at it, it was farther off, and at last he saw a thin crescent moon

shining through it.

"I am sure it cannot be night yet," he said; and he took out

one of the fattest of the young fairies, and held it up towards the hole.

"Look at that," said he; "what is to be done now? the hole is

so far off that it's night up there, and down here I haven't done eating

my lunch."

"Well," answered the young fairy, "then why don't you

whistle?"

Jack was surprised to hear her speak in this sensible manner,

and in the light of the moon he looked at her very attentively.

"When first I saw you in the nest," said he, "you had a

pinafore on, and now you have a smart little apron, with lace round it."

"That is because I am much older now," said the fairy; "we

never take such a long time to grow up as you do."

"But your pinafore?" said Jack.

"Turned into an apron, of course," replied the fairy, "just

as your velvet jacket will turn into a tail-coat when you are old enough."

"It won't," said Jack.

"Yes, it will," answered the fairy, with an air of superior

wisdom. "Don't argue with me; I am older now than you are—nearly

grown up in fact. Put me into your pocket again, and whistle as

loudly as you can."

Jack laughed, put her in, and pulled out another.

"Worse and worse," he said; "why, this was a boy fairy, and now he has a

moustache and a sword, and looks as fierce as possible!"

"I think I heard my sister tell you to whistle?" said this

fairy, very sternly.

"Yes, she did," said Jack. "Well, I suppose I had

better do it." So he whistled very loudly indeed.

"Why did you leave off so soon?" said another of them,

peeping out.

"Why, if you wish to know," answered Jack, "it was because I

thought something took hold of my legs."

"Ridiculous child!" cried the last of the four, "how do you

think you are ever to get out, if she doesn't take hold of your legs?"

Jack thought he would rather have done a long-division sum

than have been obliged to whistle; but he could not help doing it when

they told him, and he felt something take hold of his legs again, and then

give him a jerk, which hoisted him on to its back, where he sat astride,

and wondered whether the thing was a pony; but it was not, for he

presently observed that it had a very slender neck, and then that it was

covered with feathers. It was a large bird, and he presently found

that they were rising towards the hole, which had become so very far off,

and in a few minutes she dashed through the hole, with Jack on her back

and all the fairies in his pockets.

It was so dark that he could see nothing, and he twined his

arms round the bird's neck, to hold on, upon which this agreeable fowl

told him not to be afraid, and said she hoped he was comfortable.

"I should be more comfortable," replied Jack, "if I knew how

I could get home again. I don't wish to go home just yet, for I want

to see where we are flying to, but papa and mamma will be frightened if I

never do."

"Oh no," replied the albatross (for she was an albatross),

"you need not be at all afraid about that. When boys go to

Fairyland, their parents never are uneasy about them."

"Really?" exclaimed Jack.

"Quite true," replied the albatross.

"And so we are going to Fairyland?" exclaimed Jack; "how

delightful! "

"Yes," said the albatross; "the back way, mind; we are only

going the back way. You could go in two minutes by the usual route;

but these young fairies want to go before they are summoned, and therefore

you and I are taking them." And she continued to fly on in the dark

sky for a very long time.

"They seem to be all fast asleep," said Jack.

"Perhaps they will sleep till we come to the wonderful

river," replied the albatross; and just then she flew with a great bump

against something that met her in the air.

"What craft is this that hangs out no light?" said a gruff

voice.

"I might ask the same question of you," answered the

albatross sullenly.

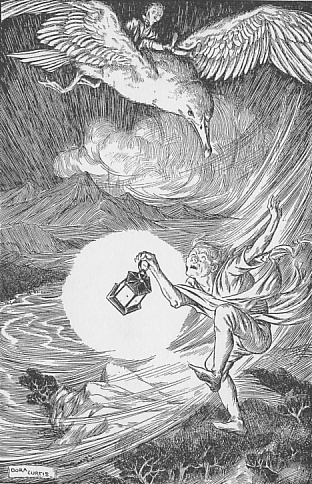

"I'm only a poor Will-o'-the-wisp," replied the voice, "and

you know very well that I have but a lantern to show." Thereupon a

lantern became visible, and Jack saw by the light of it a man, who looked

old and tired, and he was so transparent that you could see through him,

lantern and all.

"I hope I have not hurt you, William," said the albatross; "I

will light up immediately, Good night."

"Good night," answered the Will-o'-the-wisp. "I am

going down as fast as I can; the storm blew me up, and I am never easy

excepting in my native swamps."

Jack might have taken more notice of Will, if the albatross

had not begun to light up. She did it in this way. First, one

of her eyes began to gleam with a beautiful green light, which cast its

rays far and near, and then, when it was as bright as a lamp, the other

eye began to shine, and the light of that eye was red. In short, she

was lighted up just like a vessel at sea.

Thereupon a lantern became visible.

Jack was so happy that he hardly knew which to look at first,

there really were so many remarkable things.

"They snore," said the albatross, "they are very fast asleep,

and before they wake I should like to talk to you a little."

She meant that the fairies snored, and so they did, in Jack's

pockets.

"My name," continued the albatross, "is Jenny. Do you

think you shall remember that? because when you are in Fairyland and want

some one to take you home again, and call 'Jenny,' I shall be able to come

to you; and I shall come with pleasure, for I like boys better than

fairies."

"Thank you," said Jack. "Oh yes, I shall remember your

name, it is such a very easy one."

"If it is in the night that you want me, just look up,"

continued the albatross, "and you will see a green and a red spark moving

in the air; you will then call Jenny, and I will come; but remember that I

cannot come unless you do call me."

"Very well," said Jack; but he was not attending, because

there was so much to be seen.

In the first place, all the stars excepting a few large ones

were gone, and they looked frightened; and as it got lighter, one after

the other seemed to give a little start in the blue sky and go out.

And then Jack looked down and saw, as he thought, a great country covered

with very jagged snow mountains with astonishingly sharp peaks. Here

and there he saw a very deep lake—at least he thought it was a lake; but

while he was admiring the mountains, there came an enormous crack between

two of the largest, and he saw the sun come rolling up among them, and it

seemed to be almost smothered.

"Why, those are clouds!" exclaimed Jack; "and O how

rosy they have all turned! I thought they were mountains."

"Yes, they are clouds," said the albatross; and then they

turned gold colour; and next they began to plunge and tumble, and every

one of the peaks put on a glittering crown; and next they broke themselves

to pieces, and began to drift away. In fact, Jack had been out all

night, and now it was morning.

_______________

"It has been our

lot to sail with many captains, not one of whom is fit to be a patch on

your back."—Letter of the Ship's Company of H.M.S.S. Royalist to

Captain W. T. Bate.

ALL this time the

albatross kept dropping down and down like a stone till Jack was quite out

of breath, and they fell or flew, whichever you like to call it, straight

through one of the great chasms which he had thought were lakes, and he

looked down as he sat on the bird's back to see what the world is like

when you hang a good way above it at sunrise.

It was a very beautiful sight; the sheep and lambs were still

fast asleep on the green hills, and the sea birds were asleep in long rows

upon the ledges of the cliffs, with their heads under their wings.

"Are those young fairies awake yet?" asked the albatross.

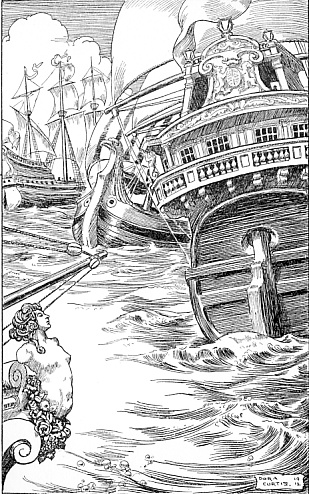

"Those five grand ones with high prows. . .

were part of the Spanish Armada and those

open boats with the blue sails belonged to

the Romans."

"As sound asleep as ever," answered Jack; "but, Albatross, is

not that the sea which lies under us? You are a sea bird, I know,

but I am not a sea boy, and I cannot live in the water."

"Yes, that is the sea," answered the albatross. "Don't

you observe that it is covered with ships?"

"I see boats and vessels," answered Jack, "and all their

sails are set, but they cannot sail because there is no wind."

"The wind never does blow in this great bay," said the bird;

"and those ships would all lie there becalmed till they dropped to pieces

if one of them was not wanted now and then to go up the wonderful river."

"But how did they come there?" asked Jack.

"Some of them had captains who ill-used their cabin-boys,

some were pirate ships, and others were going out on evil errands.

The consequence was, that when they chanced to sail within this great bay

they got becalmed; the fairies came and picked all the sailors out and

threw them into the water; they then took away the flags and pennons to

make their best coats of, threw the ship-biscuits and other provisions to

the fishes, and set all the sails. Many ships which are supposed by

men to have foundered lie becalmed in this quiet sea. Look at those

five grand ones with high prows, they are moored close together, they were

part of the Spanish Armada; and those open boats with blue sails belonged

to the Romans, they sailed with Cæsar

when he invaded Britain."

By this time the albatross was hovering about among the

vessels, making choice of one to take Jack and the fairies up the

wonderful river.

"It must not be a large one," she said, "for the river in

some places is very shallow."

Jack would have liked very much to have a fine three-master,

all to himself; but then he considered that he did not know anything about

sails and rigging, he thought it would be just as well to be contented

with whatever the albatross might choose, so he let her set him down in a

beautiful little open boat, with a great carved figure-head to it.

There he seated himself in great state, and the albatross perched herself

on the next bench, and faced him.

"You remember my name?" asked the albatross.

"Oh yes," said Jack; but he was not attending—he was thinking

what a fine thing it was to have such a curious boat all to himself.

"That's well," answered the bird; "then, in the next place,

are those fairies awake yet?" "No, they are not," said Jack; and he

took them out of his pockets, and laid them down in a row before the

albatross.

"They are certainly asleep," said the bird. "Put them

away again, and take care of them. Mind you don't lose any of them,

for I really don't know what will happen if you do. Now I have one

thing more to say to you, and that is, are you hungry?"

"Rather," said Jack.

"Then," replied the albatross, "as soon as you feel very

hungry, lie down in the bottom of the boat and go to sleep. You will

dream that you see before you a roasted fowl, some new potatoes, and an

apple-pie. Mind you don't eat too much in your dream, or you will be

sorry for it when you wake. That is all. Good-bye! I

must go."

Jack put his arms round the neck of the bird, and hugged her;

then she spread her magnificent wings and sailed slowly away. At

first he felt very lonely, but in a few minutes he forgot that, because

the little boat began to swim so fast.

She was not sailing, for she had no sail, and he was not

rowing, for he had no oars; so I am obliged to call her motion swimming,

because I don't know of a better word. In less than a quarter of an

hour they passed close under the bows of a splendid three-decker, a

seventy-gun ship. The gannets who live in those parts had taken

possession of her, and she was so covered with nests that you could not

have walked one step on her deck without treading on them. The

father birds were aloft in the rigging, or swimming in the warm green sea,

and they made such a clamour when they saw Jack that they nearly woke the

fairies—nearly, but not quite, for the little things turned round in

Jack's pockets, and sneezed, and began to snore again.

Then the boat swam past a fine brig. Some sea fairies

had just flung her cargo overboard, and were playing at leap-frog on deck.

These were not at all like Jack's own fairies; they were about the same

height and size as himself, and they had brown faces, and red flannel

shirts and red caps on. A large fleet of the pearly nautilus was

collected close under the vessel's lee. The little creatures were

feasting on what the sea fairies had thrown overboard, and Jack's boat, in

its eagerness to get on, went plunging through them so roughly that

several were capsized. Upon this the brown sea fairies looked over,

and called out angrily, "Boat ahoy!" and the boat stopped.

"Tell that boat of yours to mind what she is about," said the

fairy sea-captain to Jack.

Jack touched his cap, and said, "Yes, sir," and then called

out to his boat, "You ought to be ashamed of yourself, running down these

little live fishing-vessels so carelessly. Go at a more gentle

pace."

So it swam more slowly; and Jack, being by this time hungry,

curled himself up in the bottom of the boat, and fell asleep.

He dreamt directly about a fowl and some potatoes, and he ate

a wing, and then he ate a merrythought, and then somebody said to him that

he had better not eat any more, but he did, he ate another wing; and

presently an apple-pie came, and he ate some of that, and then he ate some

more, and then he immediately woke.

"Now that bird told me not to eat too much," said Jack, "and

yet I have done it. I never felt so full in my life," and for more

than half an hour he scarcely noticed anything.

At last he lifted up his head, and saw straight before him

two great brown cliffs, and between them flowed in the wonderful river.

Other rivers flow out, but this river flowed in, and took with it far into

the land dolphins, sword-fish, mullet, sunfish, and many other strange

creatures; and that is one reason why it was called the magic river, or

the wonderful river.

At first it was rather wide, and Jack was alarmed to see what

multitudes of soldiers stood on either side to guard the banks, and

prevent any person from landing.

He wondered how he should get the fairies on shore.

However, in about an hour the river became much narrower, and then Jack

saw that the guards were not real soldiers, but rose-coloured flamingos.

There they stood, in long regiments, among the reeds, and never stirred.

They are the only foot-soldiers the fairies have in their pay; they are

very fierce, and never allow anything but a fairy ship to come up the

river.

They guarded the banks for miles and miles, many thousands of

them, standing a little way into the water among the flags and rushes; but

at last there were no more reeds and no soldier guards, for the stream

became narrower, and flowed between such steep rocks that no one could

possibly have climbed them.

_______________

|

" 'Wake, baillie, wake! the crafts are out;

Wake!' said the knight, 'be quick!

For high street, bye street, over the town

They fight with poker and stick.'

Said the squire, 'A fight so fell was ne'er

In all thy bailliewick.'

What said the old clock in the tower?

'Tick, tick, tick!'

" 'Wake, daughter, wake! the hour draws on;

Wake!' quoth the dame, 'be quick!

The meats are set, the guests are coming,

The fiddler waxing his stick.'

She said, 'The bridegroom waiting and waiting

To see thy face is sick.'

What said the new clock in her bower?

'Tick, tick, tick!' " |

JACK looked at these

hot brown rocks, first on the left bank and then on the right, till he was

quite tired; but at last the shore on the right bank became flat, and he

saw a beautiful little bay, where the water was still, and where grass

grew down to the brink.

He was so much pleased at this change, that he cried out

hastily, "Oh how I wish my boat would swim into that bay and let me land!"

He had no sooner spoken than the boat altered her course, as if somebody

had been steering her, and began to make for the bay as fast as she could

go.

"How odd!" thought Jack. "I wonder whether I ought to

have spoken; for the boat certainly did not intend to come into this bay.

However, I think I will let her alone now, for I certainly do wish very

much to land here."

As they drew towards the strand the water got so shallow that

you could see crabs and lobsters walking about at the bottom. At

last the boat's keel grated on the pebbles; and just as Jack began to

think of jumping on shore, he saw two little old women approaching and

gently driving a white horse before them.

The horse had panniers, one on each side; and when his feet

were in the water he stood still; and Jack said to one of the old women,

"Will you be so kind as to tell me whether this is Fairyland? "

"What does he say?" asked one old woman of the other.

"I asked if this was Fairyland," repeated Jack, for he

thought the first old woman might have been deaf. She was very

handsomely dressed in a red satin gown, and did not look in the least like

a washerwoman, though it afterwards appeared that she was one.

"He says 'Is this Fairyland?'" she replied; and the other,

who had a blue satin cloak, answered, "Oh, does he?" and then they began

to empty the panniers of many small blue, and pink, and scarlet shirts,

and coats, and stockings; and when they had made them into two little

heaps they knelt down and began to wash them in the river, taking no

notice of him whatever.

Jack stared at them. They were not much taller than

himself, and they were not taking the slightest care of their handsome

clothes; then he looked at the old white horse, who was hanging his head

over the lovely clear water with a very discontented air.

At last the blue washerwoman said, "I shall leave off now;

I've got a pain in my works."

"Do," said the other. "We'll go home and have a cup of

tea." Then she glanced at Jack, who was still sitting in the boat,

and said, "Can you strike?"

"I can if I choose," replied Jack, a little astonished at

this speech. And the red and blue washerwomen wrung out the clothes,

put them again into the panniers, and, taking the old horse by the bridle,

began gently to lead him away.

"I have a great mind to land," thought Jack. "I should

not wonder at all if this is Fairyland. So as the boat came here to

please me, I shall ask it to stay where it is, in case I should want it

again."

So he sprang ashore, and said to the boat, "Stay just where

you are, will you?" and he ran after the old women, calling to them:

"Is there any law to prevent my coming into your country?"

"Wo!" cried the red-coated old woman, and the horse stopped,

while the blue-coated woman repeated, "Any law? No, not that I know

of; but if you are a stranger here you had better look out."

"Why?" asked Jack.

"You don't suppose, do you," she answered, "that our Queen

will wind up strangers?" While Jack was wondering what she meant,

the other said:

"I shouldn't wonder if he goes eight days. Gee!" and

the horse went on.

"No, wo!" said the other.

"No, no. Gee! I tell you," cried the first. Upon

this, to Jack's intense astonishment, the old horse stopped, and said,

speaking through his nose:

"Now, then, which is it to be? I'm willing to gee, and

I'm agreeable to wo; but what's a fellow to do when you say them both

together?"

"Why, he talks! " exclaimed Jack.

"It's because he's got a cold in his head," observed one of

the washerwomen; "he always talks when he's got a cold, and there's no

pleasing him; whatever you say, he's not satisfied. Gee, Boney, do!"

"Gee it is, then," said the horse, and began to jog on.

"He spoke again!" said Jack, upon which the horse laughed,

and Jack was quite alarmed.

"It appears that your horses don't talk?" observed the

blue-coated woman.

"Never," answered Jack; "they can't."

"You mean they won't," observed the old horse; and though he

spoke the words of mankind, it was not in a voice like theirs. Still

Jack felt that his was just the natural tone for a horse, and that it did

not arise only from the length of his nose. "You'll find out some

day, perhaps," he continued, "whether horses can talk or not."

" Shall I?" said Jack, very earnestly.

"They'll TELL," proceeded the white

horse. "I wouldn't be you when they tell how you've used them."

"Have you been ill used?" said Jack, in an anxious tone.

"Yes, yes, of course he has," one of the women broke in; "but

he has come here to get all right again. This is a very wholesome

country for horses; isn't it, Boney?"

"Yes," said the horse.

"Well, then, jog on, there's a dear," continued the old

woman. "Why, you will be young again soon, you know—young, and

gamesome, and handsome; you'll be quite a colt by and by, and then we

shall set you free to join your companions in the happy meadows."

The old horse was so comforted by this kind speech, that he

pricked up his ears and quickened his pace considerably.

"He was shamefully used," observed one washerwoman. "Look at

him, how lean he is! You can see all his ribs."

"Yes," said the other, as if apologising for the poor old

horse. "He gets low-spirited when he thinks of all he has gone

through; but he is a vast deal better already than he was. He used

to live in London; his master always carried a long whip to beat him with,

and never spoke civilly to him."

"London!" exclaimed Jack; "why that is in my country.

How did the horse get here?"

"That's no business of yours," answered one of the women.

"But I can tell you he came because he was wanted, which is more than you

are."

"You let him alone," said the horse in a querulous tone.

"I don't bear any malice."

"No; he has a good disposition has Boney," observed the red

old woman. "Pray, are you a boy? "

"Yes," said Jack.

"A real boy, that wants no winding up?" inquired the old

woman.

"I don't know what you mean," answered Jack; "but I am a real

boy, certainly."

"Ah!" she replied. "Well, I thought you were, by the

way Boney spoke to you. How frightened you must be! I wonder

what will be done to all your people for driving, and working, and beating

so many beautiful creatures to death every year that comes? They'll

have to pay for it some day, you may depend."

Jack was a little alarmed, and answered that he had never

been unkind himself to horses, and he was glad that Boney bore no malice.

"They worked him, and often drove him about all night in the

miserable streets, and never let him have so much as a canter in a green

field," said one of the women; "but he'll be all right now, only he has to

begin at the wrong end."

"What do you mean?" said Jack.

"Why, in this country," answered the old woman, "they begin

by being terribly old and stiff, and they seem miserable and jaded at

first, but by degrees they get young again, as you heard me reminding

him."

"Indeed," said Jack; "and do you like that?"

"It has nothing to do with me," she answered. "We are

only here to take care of all the creatures that men have ill used.

While they are sick and old, which they are when first they come to

us—after they are dead, you know—we take care of them, and gradually bring

them up to be young and happy again."

"This must be a very nice country to live in then," said

Jack.

"For horses it is," said the old lady, significantly.

"Well," said Jack, "it does seem very full of haystacks

certainly, and all the air smells of fresh grass."

At this moment they came to a beautiful meadow, and the old

horse stopped, and, turning to the blue-coated woman, said, "Faxa, I think

I could fancy a handful of clover." Upon this Faxa snatched Jack's

cap off his head, and in a very active manner jumped over a little ditch,

and gathering some clover, presently brought it back full, handing it to

the old horse with great civility.

"You shouldn't be in such a hurry," observed the old horse;

"your weights will be running down some day, if you don't mind."

"It's all zeal," observed the red-coated woman.

Just then a little man, dressed like a groom, came running

up, out of breath. "Oh, here you are, Dow!" he exclaimed to the

red-coated woman. "Come along, will you? Lady Betty wants you;

it's such a hot day, and nobody, she says, can fan her so well as you

can."

The red-coated woman, without a word, went off with the

groom, and Jack thought he would go with them, for this Lady Betty could

surely tell him whether the country was called Fairyland, or whether he

must get into his boat and go farther. He did not like either to

hear the way in which Faxa and Dow talked about their works and their

weights; so he asked Faxa to give him his cap, which she did, and he heard

a curious sort of little ticking noise as he came close to her, which

startled him.

"Oh, this must be Fairyland, I am sure," thought Jack, "for

in my country our pulses beat quite differently from that."

"Well," said Faxa, rather sharply, "do you find any fault

with the way I go?"

"No," said Jack, a little ashamed of having listened.

"I think you walk beautifully; your steps are so regular."

"She's machine-made," observed the old horse, in a melancholy

voice, and with a deep sigh. "In the largest magnifying-glass you'll

hardly find the least fault with her chain. She's not like the goods

they turn out in Clerkenwell."

Jack was more and more startled, and so glad to get his cap

and run after the groom and Dow to find Lady Betty, that he might be with

ordinary human beings again; but when he got up to them, he found that

Lady Betty was a beautiful brown mare! She was lying in a languid

and rather affected attitude, with a load of fresh hay before her, and two

attendants, one of whom stood holding a parasol over her head, and the

other was fanning her.

"I'm so glad you are come, my good Dow," said the brown mare.

"Don't you think I am strong enough to-day to set off for the happy

meadows?"

"Well," said Dow, "I'm afraid not yet; you must remember that

it is of no use your leaving us till you have quite got over the effects

of the fall."

Just then Lady Betty observed Jack, and said, "Take that boy

away; he reminds me of a jockey."

The attentive groom instantly started forward, but Jack was

too nimble for him; he ran and ran with all his might, and only wished he

had never left the boat. But still he heard the groom behind him;

and in fact the groom caught him at last, and held him so fast that

struggling was of no use at all.

"You young rascal!" he exclaimed, as he recovered breath.

"How you do run! It's enough to break your mainspring."

"What harm did I do?" asked Jack. "I was only looking

at the mare."

"Harm!" exclaimed the groom; "harm, indeed! Why, you

reminded her of a jockey. It's enough to hold her back, poor

thing!—and we trying so hard, too, to make her forget what a cruel end she

came to in the old world."

"You need not hold me so tightly," said Jack. "I shall

not run away again; but," he added, "if this is Fairyland, it is not half

such a nice country as I expected."

"Fairyland!" exclaimed the groom, stepping back with

surprise. "Why, what made you think of such a thing? This is

only one of the border countries, where things are set right again that

people have caused to go wrong in the world. The world, you know, is

what men and women call their own home."

"I know," said Jack; "and that's where I came from."

Then, as the groom seemed no longer to be angry, he went on: "And I wish

you would tell me about Lady Betty."

"She was a beautiful fleet creature, of the racehorse breed,"

said the groom; "and she won 'silver cups for her master, and then they

made her run a steeplechase, which frightened her, but still she won it;

and then they made her run another, and she cleared some terribly high

hurdles, and many gates and ditches, till she came to an awful one, and at

first she would not take it, but her rider spurred and beat her till she

tried. It was beyond her powers, and she fell and broke her

forelegs. Then they shot her. After she had died that

miserable death, we had her here, to make her all right again."

"Is this the only country where you set things right?" asked

Jack.

"Certainly not," answered the groom; "they lie about in all

directions. Why, you might wander for years, and never come to the

end of this one."

"I am afraid I shall not find the one I am looking for," said

Jack, "if your countries are so large."

"I don't think our world is much larger than yours," answered

the groom. "But come along; I hear the bell, and we are a good way

from the palace."

Jack, in fact, heard the violent ringing of a bell at some

distance; and when the groom began to run, he ran beside him, for he

thought he should like to see the palace. As they ran, people

gathered from all sides—fields, cottages, mills—till at last there was a

little crowd, among whom Jack saw Dow and Faxa, and they were all making

for a large house, the wide door of which was standing open. Jack

stood with the crowd, and peeped in. There was a woman sitting

inside upon a rocking-chair, a tall, large woman, with a gold-coloured

gown on, and beside her stood a table, covered with things that looked

like keys.

"What is that woman doing?" said he to Faxa, who was standing

close to him.

"Winding us up, to be sure," answered Faxa. "You don't

suppose, surely, that we can go for ever?"

"Extraordinary!" said Jack. "Then are you wound up

every evening, like watches?"

"Unless we have misbehaved ourselves," she answered; "and

then she lets us run down."

"And what then?"

"What then?" repeated Faxa, "why, then we have to stop and

stand against a wall, till she is pleased to forgive us, and let our

friends carry us in to be set going again."

Jack looked in, and saw the people pass in and stand close by

the woman. One after the other she took by the chin with her left

hand, and with her right hand found a key that pleased her. It

seemed to Jack that there was a tiny keyhole in the back of their heads,

and that she put the key in and wound them up.

"You must take your turn with the others," said the groom.

"There's no keyhole in my head," said Jack; "besides, I do

not want any woman to wind me up."

"But you must do as others do," he persisted; "and if you

have no keyhole, our Queen can easily have one made, I should think."

"Make one in my head!" exclaimed Jack. "She shall do no

such thing."

"We shall see," said Faxa quietly. And Jack was so

frightened that he set off, and ran back towards the river with all his

might. Many of the people called to him to stop, but they could not

run after him, because they wanted winding up. However, they would

certainly have caught him if he had not been very quick, for before he got

to the river he heard behind him the footsteps of those who had been first

attended to by the Queen, and he had only just time to spring into the

boat when they reached the edge of the water.

No sooner was he on board than the boat swung round, and got

again into the middle of the stream; but he could not feel safe till not

only was there a long reach of water between him and the shore, but till

he had gone so far down the river that the beautiful bay had passed out of

sight, and the sun was going down. By this time he began to feel

very tired and sleepy; so, having looked at his fairies, and found that

they were all safe and fast asleep, he laid down in the bottom of the

boat, and fell into a doze, and then into a dream.

They would certainly have caught him if he had not

been very quick.

_______________

BEES AND OTHER FELLOW-CREATURES

|

"The dove laid some little sticks,

Then began to coo;

The gnat took his trumpet up

To play the day through;

The pie chattered soft and long—

But that she always does;

The bee did all he had to do,

And only said 'Buzz.' " |

WHEN Jack at length

opened his eyes, he found that it was night, for the full moon was

shining; but it was not at all a dark night, for he could see distinctly

some black birds, that looked like ravens. They were sitting in a

row on the edge of the boat.

Now that he had fairies in his pockets, he could understand

bird-talk, and he heard one of these ravens saying, "There is no meat so

tender; I wish I could pick their little eyes out."

"Yes," said another, "fairies are delicate eating indeed.

We must speak Jack fair if we want to get at them." And she heaved

up a deep sigh.

Jack lay still, and thought he had better pretend to be

asleep; but they soon noticed that his eyes were open, and one of them

presently walked up his leg and bowed, and asked if he was hungry.

Jack said, "No."

"No more am I," replied the raven, "not at all hungry."

Then she hopped off his leg, and Jack sat up.

"And how are the sweet fairies that my young master is taking

to their home?" asked another of the ravens. "I hope they are safe

in my young master's pockets?"

Jack felt in his pockets. Yes, they were all safe; but

he did not take any of them out, lest the ravens should snatch at them.

"Eh?" continued the raven, pretending to listen; "did this

dear young gentleman say that the fairies were asleep?"

"It doesn't amuse me to talk about fairies," said Jack; "but

if you would explain some of the things in this country that I cannot make

out, I should be very glad."

"What things?" asked the blackest of the ravens.

"Why," said Jack, "I see a full moon lying down there among

the water-flags and just going to set, and there is a half-moon overhead

plunging among those great grey clouds, and just this moment I saw a thin

crescent moon peeping out between the branches of that tree."

"Well," said all the ravens at once, "did the young master

never see a crescent moon in the men and women's world?"

"Oh yes," said Jack.

"Did he never see a full moon?" asked the ravens.

"Yes, of course," said Jack; "but they are the same moon.

I could never see all three of them at the same time."

The ravens were very much surprised at this, and one of them

said:

"If my young master did not see the moons it must have been

because he didn't look. Perhaps my young master slept in a room, and

had only one window; if so, he couldn't see all the sky at once."

"I tell you, Raven," said Jack, laughing, "that I

KNOW there is never more than one moon in my

country, and sometimes there is no moon at all!"

Upon this all the ravens hung down their heads, and looked

very much ashamed; for there is nothing that birds hate so much as to be

laughed at, and they believed that Jack was saying this to mock them, and

that he knew what they had come for. So first one and then another

hopped to the other end of the boat and flew away, till at last there was

only one left, and she appeared to be out of spirits, and did not speak

again till he spoke to her.

"Raven," said Jack, "there's something very cold and slippery

lying at the bottom of the boat. I touched it just now, and I don't

like it at all."

"It's a water-snake," said the raven, and she stooped and

picked up a long thing with her beak, which she threw out, and then looked

over. "The water swarms with them, wicked, murderous creatures; they

smell the young fairies, and they want to eat them."

Jack was so thrown off his guard that he snatched one fairy

out, just to make sure that it was safe. It was the one with the

moustache; and, alas! in one instant the raven flew at it, got it out of

his hand, and pecked off its head before it had time to wake or Jack to

rescue it. Then, as she slowly rose, she croaked, and said to Jack,

"You'll catch it for this, my young master!" and she flew to the bough of

a tree, where she finished eating the fairy, and threw his little empty

coat into the river.

On this Jack began to cry bitterly, and to think what a

foolish boy he had been. He was the more sorry because he did not

even know that poor little fellow's name. But he had heard the

others calling by name to their companions, and very grand names they were

too. One was Jovinian—he was a very fierce-looking gentleman; the

other two were Roxaletta and Mopsa.

Presently, however, Jack forgot to be unhappy, for two of the

moons went down, and then the sun rose, and he was delighted to find that

however many moons there might be, there was only one sun, even in the

country of the wonderful river.

So on and on they went; but the river was very wide, and the

waves were boisterous. On the right brink was a thick forest of

trees, with such heavy foliage that a little way off they looked like a

bank, green and smooth and steep; but as the light became clearer, Jack

could see here and there the great stems, and see creatures like foxes,

wild boars, and deer, come stealing down to drink in the river.

It was very hot here; not at all like the spring weather he

had left behind. And as the low sunbeams shone into Jack's face he

said hastily, without thinking of what would occur, "I wish I might land

among those lovely glades on the left bank."

No sooner said than the boat began to make for the left bank,

and the nearer they got towards it the more beautiful it became; but also

the more stormy were the reaches of water they had to traverse.

A lovely country indeed! It sloped gently down to the

water's edge, and beautiful trees were scattered over it, soft mossy grass

grew everywhere, great old laburnum trees stretched their boughs down in

patches over the water, and higher up camellias, almost as large as

hawthorns, grew together and mingled their red and white flowers.

The country was not so open as a park, it was more like a

half-cleared woodland; but there was a wide space just where the boat was

steering for, that had no trees, only a few flowering shrubs. Here

groups of strange-looking people were bustling about, and there were

shrill fifes sounding, and drums.

Farther back he saw rows of booths or tents under the shade

of the trees.

In another place some people dressed like gipsies had made

fires of sticks just at the skirts of the woodland, and were boiling their

pots. Some of these had very gaudy tilted carts, hung all over with

goods, such as baskets, brushes, mats, little glasses, pottery, and beads.

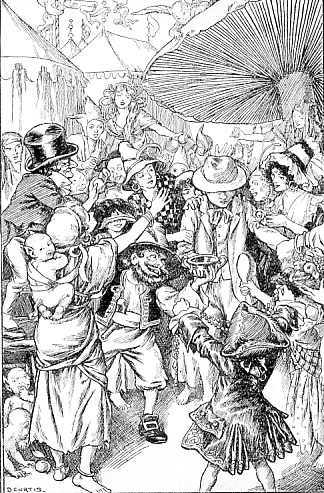

It seemed to be a kind of fair, to which people had gathered

from all parts; but there was not one house to be seen. All the

goods were either hung upon the trees or collected in strange-looking

tents.

The people were not all of the same race; indeed, he thought

the only human beings were the gipsies, for the folks who had tents were

no taller than himself.

"What'll you buy?—what'll you buy, sir?"

How hot it was that morning! and as the boat pushed itself

into a little creek, and made its way among the beds of yellow and purple

iris which skirted the brink, what a crowd of dragonflies and large

butterflies rose from them!

"Stay where you are!" cried Jack to the boat; and at that

instant such a splendid moth rose slowly, that he sprang on shore after

it, and quite forgot the fair and the people in his desire to follow it.

The moth settled on a great red honey-flower, and he stole up

to look at it. As large as a swallow, it floated on before him.

Its wings were nearly black, and they had spots of gold on them.

When it rose again Jack ran after it, till he found himself

close to the rows of tents where the brown people stood; and they began to

cry out to him, "What'll you buy? what'll you buy, sir?" and they crowded

about him, so that he soon lost sight of the moth, and forgot everything

else in his surprise at the booths.

They were full of splendid things—clocks and musical boxes,

strange china ornaments, embroidered slippers, red caps, and many kinds of

splendid silks and small carpets. In other booths were swords and

dirks, glittering with jewels; and the chatter of the people when they

talked together was not in a language that Jack could understand.

Some of the booths were square, and evidently made of common

canvas, for when you went into them and the sun shone you could distinctly

see the threads.

But scattered a little farther on in groups were some round

tents, which were far more curious. They were open on all sides, and

consisted only of a thick canopy overhead, which was supported by one

beautiful round pillar in the middle.

Outside, the canopy was white or brownish; but when Jack

stood under these tents, he saw that they were lined with splendid

flutings of brown or pink silk: what looked like silk, at least, for it

was impossible to be sure whether these were real tents or gigantic

mushrooms.

They varied in size, also, as mushrooms do, and in shape:

some were large enough for twenty people to stand under them, and had flat

tops with a brown lining; others had dome-shaped roofs; these were lined

with pink, and would only shelter six or seven.

The people who sold in these tents were as strange as their

neighbours; each had a little high cap on his head, in shape just like a

beehive, and it was made of straw, and had a little hole in front.

In fact, Jack very soon saw bees flying in and out, and it was evident

that these people had their honey made on the premises. They were

chiefly selling country produce. They had cheeses so large as to

reach to their waists, and the women trundled them along as boys do their

hoops. They sold a great many kinds of seed too, in wooden bowls,

and cakes and good things to eat, such as gilt gingerbread. Jack

bought some of this, and found it very nice indeed. But when he took

out his money to pay for it, the little man looked rather strangely at it,

and turned it over with an air of disgust. Then Jack saw him hand it

to his wife, who also seemed to dislike it; and presently Jack observed

that they followed him about, first on one side, then on the other.

At last, the little woman slipped her hand into his pocket, and Jack,

putting his hand in directly, found his sixpence had been returned.

"Why, you've given me back my money!" he said.

The little woman put her hands behind her. "I do not

like it," she said; "it's dirty; at least, it's not new."

"No, it's not new," said Jack, a good deal surprised, "but it

is a good sixpence."

"The bees don't like it," continued the little woman.

"They like things to be neat and new, and that sixpence is bent."

"What shall I give you then?" said Jack. The good

little woman laughed and blushed.

"This young gentleman has a beautiful whistle round his

neck," she observed, politely, but did not ask for it.

Jack had a dog-whistle, so he took it off and gave it to her.

"Thank you for the bees," she said. "They love to be

called home when we've collected flowers for them."

So she made a pretty little curtsey, and went away to her

customers.

There were some very strange creatures also, about the same

height as Jack, who had no tents, and seemed there to buy, not to sell.

Yet they looked poorer than the other folks and they were also very cross

and discontented; nothing pleased them. Their clothes were made of

moss, and their mantles of feathers; and they talked in a queer whistling

tone of voice, and carried their skinny little children on their backs and

on their shoulders.

They were treated with great respect by the people in the

tents; and when Jack asked his friend to whom he had given the whistle

what they were, and where they got so much money as they had, she replied

that they lived over the hills, and were afraid to come in their best

clothes. They were rich and powerful at home, and they came shabbily

dressed, and behaved humbly, lest their enemies should envy them. It

was very dangerous, she said, to fairies to be envied.

Jack wanted to listen to their strange whistling talk, but he

could not for the noise and cheerful chattering of the brown folks, and

more still for the screaming and talking of parrots.

Among the goods were hundreds of splendid gilt cages, which

were hung by long gold chains from the trees. Each cage contained a

parrot and his mate, and they all seemed to be very unhappy indeed.

The parrot could talk, and they kept screaming to the

discontented women to buy things for them, and trying very hard to attract

attention.

One old parrot made himself quite conspicuous by these

efforts. He flung himself against the wires of his cage, he

squalled, he screamed, he knocked the floor with his beak, till Jack and

one of the customers came running up to see what was the matter.

"What do you make such a fuss for?" cried the discontented

woman. "You've set your cage swinging with knocking yourself about;

and what good does that do? I cannot break the spell and open it for

you."

"I know that," answered the parrot, sobbing; "but it hurts my

feelings so that you should take no notice of me now that I have come down

in the world."

"Yes," said the parrot's mate, "it hurts our feelings."

"I hav'nt forgotten you," answered the woman, more crossly

than ever; "I was buying a measure of maize for you when you began to make

such a noise."

Jack thought this was the queerest conversation he had ever

heard in his life, and he was still more surprised when the bird answered:

"I would much rather you would buy me a pocket-handkerchief.

Here we are, shut up, without a chance of getting out, and with nobody to

pity us; and we can't even have the comfort of crying, because we've got

nothing to wipe our eyes with."

"But at least," replied the woman, "you CAN

cry now if you please, and when you had your other face you could not."

"Buy me a handkerchief," sobbed the parrot.

"I can't afford both," whined the cross woman, "and I've paid

now for the maize." So saying, she went back to the tent to fetch

her present to the parrots, and as their cage was still swinging Jack put

out his hand to steady it for them, and the instant he did so they became

perfectly silent, and all the other parrots on that tree, who had been

flinging themselves about in their cages, left off screaming and became

silent too.

The old parrot looked very cunning. His cage hung by

such a long gold chain that it was just on a level with Jack's face, and

so many odd things had happened that day that it did not seem more odd

than usual to hear him say, in a tone of great astonishment:

"It's a BOY, if ever there was one!"

"Yes," said Jack, "I'm a boy."

"You won't go yet, will you?" said the parrot.

"No, don't," said a great many other parrots. Jack

agreed to stay a little while, upon which they all thanked him.

"I had no notion you were a boy till you touched my cage,"

said the old parrot.

Jack did not know how this could have told him, so he only

answered, "Indeed!"

"I'm a fairy," observed the parrot, in a confidential tone.

"We are imprisoned here by our enemies the gipsies."

"So we are," answered a chorus of other parrots.

"I'm sorry for that," replied Jack. "I'm friends with

the fairies."

"Don't tell," said the parrot, drawing a film over his eyes,

and pretending to be asleep. At that moment his friend in the moss

petticoat and feather cloak came up with a little measure of maize, and

poured it into the cage.

"Here, neighbour," she said; "I must say good-bye now, for

the gipsy is coming this way, and I want to buy some of her goods."

"Well, thank you," answered the parrot, sobbing again; "but I

could have wished it had been a pocket-handkerchief."

"I'll lend you my handkerchief," said Jack. "Here!"

And he drew it out and pushed it between the wires.

The parrot and his wife were in a great hurry to get Jack's

handkerchief. They pulled it in very hastily; but instead of using

it they rolled it up into a ball, and the parrot-wife tucked it under her

wing.

"It makes me tremble all over," said she, "to think of such

good luck."

"I say!" observed the parrot to Jack, "I know all about it

now. You've got some of my people in your pockets—not of my own

tribe, but fairies."

By this Jack was sure that the parrot really was a fairy

himself, and he listened to what he had to say the more attentively.

|

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)