|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XXIV.

CONVERSATIONS WITH MR. GLADSTONE

WERE I to edit a new journal again I should call it

Open Thought. I know no characteristic of man so wise, so

useful, so full of promise of progress as this. The great volume of

Nature, of Man and of Society opens a new page every day, and Mr.

Gladstone read it. It was this which gave him that richness of

information in which he excited the admiration of all who conversed with

him.

|

|

|

Holyoake, aged 87. |

Were Plutarch at hand to write Historical Parallels of famous

men of our time, he might compare Voltaire and Gladstone. Dissimilar

as they were in nature, their points of resemblance were notable.

Voltaire was the most conspicuous man in Europe in the eighteenth century,

as Mr. Gladstone became in the nineteenth. Both were men of wide

knowledge beyond all their contemporaries. Each wrote more letters

than any other man was ever known to write. Every Court in Europe

was concerned about the movements of each, in his day. Both were

deliverers of the oppressed, where no one else moved on their behalf.

Both attained great age, and were ceaselessly active to the last. In

decision of conviction they were also alike. Voltaire was as

determinedly Theistic as Mr. Gladstone was Christian. They

were alike also in the risks they undertook in defence of the right.

Voltaire risked his life and Gladstone his reputation to save others.

Mr. Morley relates of the Philosopher of Ferney, that when he made his

triumphal journey through Paris, some one asked a woman in the street "why

do so many people follow this man?" "Don't you know?" was the reply.

"He was the deliverer of the Calas." No applause went to Voltaire's

heart like that. Mr. Gladstone had also golden memories of

deliverance no one else moved hand or foot to effect, and multitudes, even

nations, followed him because of that.

On the first occasion of my going to breakfast with him he

was living in Harley Street, in the house in which Sir Charles Lyell died.

As Mr. Gladstone entered the room, he apologised for not greeting me

earlier, as his servant had indistinctly given him my name. He asked

me to sit next to him at breakfast. There were seven or eight

guests. The only one I knew was Mr. Walter. H. James, M.P., since

Lord Northbourne—probably present from consideration for me. One

was the editor of the Jewish World, a journal opposed to Mr.

Gladstone's anti-Turkish policy. Others were military officers and

travellers of contemporary renown. It was a breakfast to

remember—Mr. Gladstone displayed such a bright, unembarrassed vivacity.

He told amusing anecdotes of the experiences of the wife of the

Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, whose charm he said he could only describe by

the use of the English rural term "buxom." On making a time-bargain

with a cabman, he observed to her ladyship that "he wished the engagement

was for life." Mr. Gladstone thought no English cabman would have

said that. Another pleasantry was of one of Lord Lyttelton's sons,

who was very tall and lank. He being in Birmingham and wishful to

know the distance to a place he sought, asked a boy in the street who was

passing, "how far it was." "Oh, not far," was the assuring but

indefinite answer. "But can you not give me some better idea of the

distance?" Mr. Lyttelton inquired. "Well, sir," said the lad,

looking up at the obelisk-like interrogator before him, "if you was to

fall down, you would be half way there."

These incidents were not new to me, but I was glad to hear

what was probably the origin of them. From Mr. Gladstone's lips they

had a sort of historic reality which was interesting to me.

Afterwards he spoke of the singular beauty of the "Dream of

Gerontius" by Cardinal Newman, and turning to me asked if I knew of it, as

though he thought it unlikely my reading lay in that direction. He

was very much surprised when I said I had read it with great admiration.

He said it was strange, as he had mentioned the poem at three or four

breakfast tables, without finding any one who knew it.

As I left, Mr. Gladstone accompanied me downstairs. On

the way I took occasion to thank him for a paper that had appeared in the

Contemporary, containing definitions of heretical forms of thought,

so fair and accurate and actual, that Shakespeare or Bunyan, who had the

power of possessing himself of the minds of those whose thoughts he

expressed, might have produced. There had been nothing to compare

with it in my time. Theological writers described heterodox tenets

from their inferences of what they must be—never inquiring what they

actually stood for in the minds of those who held them—whereas he had

written with unimputative knowledge. Stopping on the first platform

of the stairway we reached, he paused, and (holding the lapel of his coat

with his hand, as I had seen him do in the House of Commons) he said he

was glad I was able to think so, "for that is the quality in which you

yourself excel." This amazed me, as I never imagined that he had

ever taken notice of speeches or writings of mine, or formed any opinion

upon them. Nor was he the man to say what I cite from mere courtesy.

The second time I breakfasted in Harley Street was in the

days of the Eastern question. Mr. John Morley was one of the party.

Mr. Gladstone had again the same disengaged manner. Before his

guests broke up he entered the room, bearing on his arm a pile of letters

and telegrams, and apologised for leaving us as he had to attend to them.

That morning Mr. Bright came in, and seeing me, said, "Poor Acland is

dead. Of course there was nothing in the house, and a few of us had

to subscribe to bury him." James Acland was the rider on a white

horse who preceded Cobden and Bright the day before their arrival to

address the farmers on the anti-Corn Law tour in the counties. Mr.

Gladstone's grand-daughter was to have arrived at Harley Street that

morning, but her nurse missed the train. When she appeared, Bright,

who had suggested dolorous adventures to account for her non-appearance,

proposed, when the child was announced to be upstairs, that a charge of

sixpence should be made for each person going to see her.

That morning one of the guests, who was an actor, maintained

that it was not necessary that an actor should feel his part. Mr.

Gladstone, to whom conviction was his inspiration—who never spoke without

believing what he said—dissented from the actor's theory, as I had done.

Towards the end of his life, I saw Mr. Gladstone twice at the

Lion Mansion in Brighton. On one occasion he said, after speaking of

Cardinal Newman and his brother Francis, "I remember Dr. Martineau telling

me that there was a third brother, a man also of remarkable power, but he

was touched somewhere here," putting his finger to his forehead. "Do

you know whether it was so? It is so long since Dr. Martineau named

it to me, and my impression may be wrong." I answered, "It was true.

At one time I had correspondence with Charles Newman. He would say

at times, 'My mind is going from me for a time. Do not expect to

hear from me until my mind returns.' In power of reasoning, he was,

when he did reason, distinguished for boldness and vigour." Mr.

Gladstone said, "When you write again to his brother Francis, convey to

him for me the assurance of my esteem. I am glad you believe that

the cessation in his correspondence was not occasioned by anything on my

part or any change of feeling on his. I must have been mistaken if I

ever described Mr. Francis Newman as 'a man of considerable talent.'

He was much more than that. His powers of mind may be said to amount

to genius."

Mr. Gladstone asked what I would advise as a rule of policy

as to the Anarchists who threw the bombs in the French Chambers. I

answered, "There were serious men who came to have Anarchical views from

despair of the improvement of society. There were also foolish

Anarchists who think they can put the world to rights, had they a clear

field before them. There are also a class who are quite persuaded

that by killing people who have nothing to do with the evils they complain

of, they will intimidate those who have. They take destruction to be

a mode of progress. These persons are as mad as they are made, and

you cannot legislate against insanity."

|

|

|

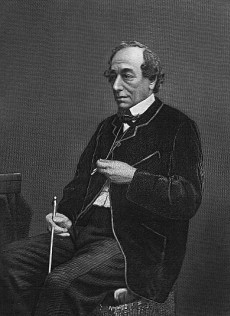

Charles Bradlaugh

(1833-91) |

I mentioned the case of a Nonconformist minister, who was so incensed by

the injustice done to Mr. Bradlaugh that he took a revolver, loaded, to

Palace Yard, intending to

shoot the policemen who maltreated him. But the member for Northampton was

altogether against such proceedings. The determined rectifier of wrong in

question had a

project of throwing a bomb from the gallery on to the floor of the House. I had great difficulty in dissuading him from this frightful act. He was

no coward, and was quite

prepared to sacrifice his own life. To those ebullitions of vengeance

society in every age has been subject, and its best protection lies in

intrepid disdain and cool precaution. The affair of Phoenix Park showed

that the English nation did not go mad in the face of desperate outrage. However, Mr. Gladstone

himself gave the best

answer to his inquiry. He said, "The Spanish Government had solicited him

to join in a federation against Anarchists. But how could we do

that? We cannot tell what other Governments may do, and we should be held

responsible for their acts which we might deplore."

He added, "It fills me with surprise, not to say disgust, to see it said

at times in Liberal papers that the Tories of to-day are superior to their

class formerly. Sir Robert Peel

was a man of high honour, patriotism, and self-respect. He would never

have joined in nor countenanced the treatment to which Mr. Bradlaugh was

subjected. I never knew

the Tories do a meaner thing. Nothing could have induced Sir Robert Peel

to consent to that."

On one occasion, after reference to out-of-the-way persons of whom I

happened to have some knowledge, Mr. Gladstone said, "I have known many

remarkable men. My

position has brought me in contact with numbers of persons." Indeed, it

seemed when talking to him that you were talking to mankind, so

diversified and plentiful were the

persons living in his memory, and who, as it were, stepped out in his

conversation before you. The individuality, the environment of persons,

all came into light. His

conversation was like an oration in miniature. Its exactness, its

modulation, its force of expression, its foreseeingness of all the issues

of ideas, came at will. I never

listened to conversation so easy, so natural, so precise, so full of

colour and truth, spoken with such spontaneity and force.

|

|

|

William Ewart Gladstone |

Mr. Morley, in his "Life of Gladstone," cites a letter he sent to me in

1875: "Differing from you, I do not believe that secular motives are

adequate either to propel or restrain

the children of our race, but I earnestly desire to hear the other side,

and I appreciate the advantage of having it stated by sincere and

high-minded men." This shows his

brave open-mindedness.

A few years later it came into my mind that my expressions of respect for

persons whose Christian belief arose from honest conviction, and was

associated with efforts for

the improvement of the material condition of the people, might lead him to

suppose that I myself inclined to belief in Christian tenets of faith. I

therefore sent him my new book

on "The Origin and Nature of Secularism: Showing that where Free Thought

commonly ends Secularism begins"—saying that as I had the honour of his

correspondence, I

ought not to leave him unaware of the nature of my own opinions. He

answered that he thought my motive a right one in sending the book to him,

and that he had read a

considerable part with general concurrence, though, in other parts, the

views expressed were painful to him. But this made no difference in his

friendship, which

continued to the end of his days.

An unknown aphorist of 1750, whom Mr. Bertram Dobell quotes, exclaims:

"Freethinker! What a term of honour; or, if you will, dishonour; but

where is he who can claim it?" Mr. Gladstone might claim it beyond any

other eminent Christian

I have known. It was he who, at the opening of

the Liverpool College some years ago, warned the clergy that "they could

no longer defend their tenets by railing or reticence"—a shaft that went

through the soul of

that policy of silence and defamation pursued by them for half a century. Mr. Gladstone was the first to see it must be abandoned.

It is Diderot who relates that one who was searching for a path through a

dark forest by the light of a taper, met a man who said to him, "Friend,

if thou wouldst find thy way

here, blow out thy light." The taper was Reason, and the man who said blow

it out was a priest. Mr. Gladstone would have said, "Take care of that

taper, friend;

and if you can convert it into a torch do so, for you will need it to see

your way through the darkness of human life."

At our last interview he said, "You and I are growing old. The day is

nearing when we shall enter—" Here he paused, as though he was going to

say another life, but not

wishing to say what I might not concur in, in his sense, he—before his

pause was well noticeable—added, "enter a changed state." What my views

were he knew, as I had

told him in a letter: "I hope there is a future life, and, if so, my not

being sure of it will not prevent it, and I know of no better way of

deserving it than

by conscious service of humanity. The universe never filled me with such

wonder and awe as when I knew I could not account for it. I admit

ignorance is a privation. But to

submit not to know, where knowledge is withheld, seems but one of the

sacrifices that reverence for truth imposes on us."

I had reason to acknowledge his noble personal courtesy, notwithstanding

convictions of mine he must think seriously erroneous, upon which, as I

told him, "I did not keep

silence."

He had the fine spirit of the Abbé Lamennais, who, writing of a book of

mark depicting the "passive" Christian, said: "The active Christian

who is ceaselessly fighting the

enemies of humanity, without omitting to pardon and love them—of this

type of Christian I find no trace whatever." Mr. Gladstone was of that

type. It was his distinction that he

applied this affectionate tolerance not only to the "enemies of humanity,"

but to the dissentients from the faith he loved so well.

At our last meeting in Brighton he asked my address, and said he would

call upon me. He wished me to know Lord Acton, whom he would ask to see

me. An official

engagement compelled Lord Acton to defer his visit, of which Mr. Glad

stone sent me notice. It was a great loss not to converse with one who

knew so much as Lord

Acton did.

Mr. Gladstone knew early what many do not know yet, that courtesy and even

honour to adversaries do not imply coincidence in opinion. As I was for

the right of free

thought, I regarded all manifestations of it with interest, whether

coinciding with or opposing views I hold. Shortly before his death I wrote

to him, when Miss Helen Gladstone

sent me word, "To-day I read to my father your letter, by which he was

much touched and pleased, and he desired me to send you his best thanks."

I shall always be proud

to think that any words of mine gave even momentary pleasure to one who

has given delight to millions, and will be an inspiration to millions

more.

In former times, when an eminent woman contributed to the distinction of

her consort, he alone received the applause. In these more discriminating

days, when the noble

companionship of a wife has made her husband's eminence possible, honour

is due to her also. Therefore, on drawing the resolution of condolence to

Mrs. Gladstone,

adopted at the Peterborough Co-operative Congress, we made the

acknowledgment how much was due to the wife as well as the husband. I

believe no resolution sent to her,

but ours, did this. Sympathy is not enough where honour is due.

In the splendid winter of Mr. Gladstone's days there was no ice in his

heart. Like the light that ever glowed in the temple of Montezuma the

generous fire of his enthusiasm never went out. The nation mourned his

loss with a pomp of sorrow more deep and universal than ever exalted the

memory of a king.

CHAPTER XXV.

HERBERT SPENCER, THE THINKER

A STAR of the first magnitude went out of the

firmament of original thought by the death of Herbert Spencer. His

was the most distinctive personality that remained with us after the death

of Mr. Gladstone. Spencer was as great in the kingdom of science as

Mr. Gladstone was in that of politics and ecclesiasticism. Men have

to go back to Aristotle to find Spencer's compeer in range of thought, and

to Gibbon for a parallel to his protracted persistence in accomplishing

his great design of creating a philosophy of evolution. Mr.

Spencer's distinction was that he laid down new landmarks of evolutionary

guidance in all the dominions of human knowledge. Gibbon lived to

relinquish his pen in triumph at the end of years of devotion to his

"History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire"—Mr. Spencer planned

the history of the rise and growth of a mightier, a more magnificent, and

more beneficent Empire—that of Universal Law—and for forty years he

pursued his mighty story in every vicissitude of strength with unfaltering

purpose, and lived to complete it amid the applause of the world and the

gratitude of all who have the grand passion to understand Nature, and

advance the lofty destiny of humanity.

|

|

|

Herbert Spencer

(1820-1903) |

Herbert Spencer was born April 27, 1820, in the town of Derby, and died in

his eighty-fourth year, December 8, 1903, at 5, Percival Terrace,

Brighton, next door to his friend, Sir James Knowles, the editor of the

Nineteenth Century. At the time of his birth, Derby was emerging from the

sleepy, dreamy, stagnant, obfuscated condition in which it had lain since

the days of the Romans.

It is difficult to write of Spencer without wondering how a thinker of his

quality should have been born in Derby—a town which had a determined

objection to individuality in ideas. It has a Charter—its first act of

enterprise in a thousand years—obtained by the solicitations of the

inhabitants from Richard I., which gave them the power of expelling every

Jew who resided in the town, or ever after should approach it. Centuries

later, in the reigns of Queen Anne and George I., not a Roman Catholic, an

Independent, a Baptist, an Israelite, nor even an unmolesting Quaker could

be found in Derby.

There still remains one lineal descendant of the stagnant race which

procured the Charter of

Darkness from Richard I.—Mr. Alderman W. Winter, who opposed in the Town

Council a resolution of honour in memory of Spencer, who had given Derby

its great distinction, because his views contradicted the antediluvian

Scriptural account of the Creation, when there was no man present to

observe what took place, and no man of science existed capable of

verifying the Mosaic tradition. The only recorded instance of independency

of opinion was that of a humble Derby girl, who was born blind, yet could

see, like others, into the nature of things. She doubted the Real

Presence. What could it matter what the poor, helpless thing thought of

that? But the town burned her alive. The brave, unchanging girl, whose

convictions were torment-proof, was only twenty-two years old.

The only Derby man of free thought who preceded Herbert Spencer was

William Hutton, a silk weaver, who became the historian of Derby and

Birmingham. In sagacity, boldness and veracity he excelled. The wisdom of

his opinions was a century in advance of his time (1770-1830).

There were no photographs in the time of Mr. Spencer's parents, and their

lineaments are little known. Mr. Spencer's uncle I knew, the Rev. Thomas

Spencer, a clergyman of middle stature, slender, with a paternal

Evangelical expression. But his sympathies were with Social Reform, in

which field he was an insurgent worker for projects then unregarded or

derided.

When I first knew Mr. Herbert Spencer, he was one of the writers on the

Leader newspaper. We dined at times at the Whittington Club, then recently

founded by Douglas Jerrold. At this period Mr. Spencer had a half-rustic

look. He was ruddy, and gave the impression of being a young country

gentleman of the sporting farmer type, looking as unlike a philosopher as

Thomas Henry Buckle looked like a historian, as he appeared to me on my

first interview with him. Mr. Spencer at that time would take part in

discussions in a determined tone, and was persistent in definite

statement. In that he resembled William Chambers, with whom I was present

at a deputation to Lord Derby on the question of the Paper Duty. Lord

Derby could not bow him out, nor bow him into silence, until he had stated

his case.

In those days Mr. Spencer spoke with misgivings of his health. Mr. Edward Pigott, chief proprietor of the

Leader (afterwards Public Examiner of

Plays) asked me to try to disabuse Mr. Spencer of his apprehensiveness,

which was constitutional and never left his mind all his life, and I

learned never to greet him in terms which implied that he was, or could be

well. Coleridge complained of ailments of which no physical sign was

apparent, and he was thought, like Mr. Spencer, to be an imaginary

invalid. But after

his death Coleridge was found to have a real cause of suffering, and the

wonder was that he did not complain more.

There must be a distinct susceptibility of the nerves—which Sir Michael

Foster could explain—peculiar to some persons. I have had two or three

friends of some literary distinction, whom I made it a rule never to

accost, or even to know when I met them, until they had recovered from the

inevitable shock of meeting some unexpected person, when they would

spontaneously become genial.

Mr. Spencer's high spirit was shown in this. Though he often had to

abandon his thinking, he resumed it on his recovery. The continuity of his

thought never ceased. One form of trouble was recurring depression, so

difficult to sustain, which James Thompson, who oft experienced it,

described—when a man has to endure

|

"The same old solid hills and leas;

The same old stupid, patient trees;

The same old ocean, blue and green;

The same sky, cloudy or serene;

The old two dozen hours to run

Between the settings of the sun."

|

Mr. Spencer was first known to London thinkers by being found the

associate of economists like Bagot; philosophers with a turn for

enterprise in the kingdom of speculation—as George Henry Lewes, Darwin,

Huxley, Tyndall; and of great

novelists like George Eliot. In those days the house of John Chapman, the

publisher, was the meeting ground of French, Italian, German and other

Continental thinkers. There, also, congregated illustrious Americans like

Ralph Waldo Emerson, and other unlicensed explorers in the new world of

thought. There Mr. Spencer became known to men of mark in America, who

made his fame before his countrymen recognised him. If it was England who

"raised" Mr. Spencer, it was America that discovered him. Mr. George Iles,

a distinguished American friend of Mr. Spencer, sends me information of

the validity of American admiration of him, on the authority of the Daily

Witness: "Mr. Spencer's income is mainly drawn from the sale of his books

in America, his copyrights there having yielded him 4,730 dollars in the

last six months. A firm of publishers have paid in the last six months

royalties amounting nearly to ten thousand dollars to Mr. Herbert Spencer

and the heirs or executors of Darwin, Huxley and Tyndall. The sales of

Spencer's and Darwin's books lead those of Huxley and Tyndall."

During the earlier publication of his famous volumes, his expenditure in

printing and in employing assistants in gathering facts for his arguments,

exhausted all his means. Lord Stanley, of that day, was understood to have

offered him an appointment, which included leisure for his investigations. But he declined the thoughtful offer, deeming the office to be of the

nature of a sinecure. Wordsworth accepted such an appointment, and repaid

the State in song, as Spencer would have repaid it in philosophy.

I had the honour to be Mr. Spencer's outdoor friend. He asked me to make

known the publication of his work to persons whom I knew to be friendly to

enterprise in thought. For years I assiduously sought to be of service in

this way.

One day in 1885, being the guest, in Preston, of the Rev. William Sharman,

he showed me a passage in one of Mr. Spencer's volumes, published in 1874,

which I had not seen, and which surprised me much, in which it appeared

Secularists were below Christians in their sense of fiduciary integrity. Mr. Sharman said, "Defective as we are supposed to be, you will see that

Secularists are one degree lower in morality than the clergy." Mr. Spencer

had given instances which, in his opinion, "showed that the cultivation

of the intellect does not advance morality." If that were so, it would

follow that it was better to remain ignorant—if ignorance better develops

the ethical sense. The instance Mr. Spencer gives occurs in the "Study of

Sociology" (pp. 4 18-19), "Written to show how little operative on

conduct is mere teaching. Let me give, says Mr. Spencer, a striking fact

falling under my observation:

"Some twelve years ago was commenced a serial publication, limited in its

circulation to the well educated. It was issued to subscribers, from each

of whom was due a small sum for every four numbers. The notification

periodically made of another subscription due received from some prompt

attention, from others an attention less tardy than before, and from

others no attention at all. After a lapse of ten years, a digest was made

of the original list, when it was found that those who finally declined

paying for what they had year after year received, constituted, among

others, the following percentages:

|

Christian defaulters .... .... .... 31 per cent.

Secularist defaulters.... .... .... 32 per cent." |

I wrote to Mr. Spencer as follows:

"EASTERN LODGE, BRIGHTON,

"December 1, 1885.

"MY DEAR MR.

SPENCER,—I am like the sailor who knocked down the Jew, and

when he was remonstrated with said, 'He did it because he had crucified

his Lord and Saviour.' When told that that occurred 2,000 years ago he

answered, 'But I only heard of it last night.'

"It was but a few days ago that your notice of Secularist fraudulency,

made in 1874, became known to me.

"From so dispassionate and analytic an authority as yourself, your

reflection on the ethical insensibility of Secularists justifies me in

asking your attention

to certain facts. By what test did you know that 32 per cent. of

defaulters were Secularists? The names I gave you were of persons likely

to take in your work if prospectuses were sent to them. But many of them

were not Secularists. Some of them were ministers of religion, others

Churchmen, but having individually a taste for philosophical inquiry,

"You do not say that these persons sent in their names as subscribers. Yet

unless they did, they cannot be justly described 'as regardless of an

equitable, claim.' Had you informed me of any whose names I gave you, who

had not paid for the work, after undertaking to do so, I could have

procured you the payment, for all whose names I gave I believe to be men

of good faith.—With real regard,

"GEORGE JACOB

HOLYOAKE.

Mr. Spencer sent me the following reply:

"38, QUEEN'S GARDENS, BAYSWATER, LONDON, W.,

"November 16, 1885.

"DEAR MR. HOLYOAKE,—You ask how I happen to know of certain defaulters

that they were Secularists. I know them as such simply because their names

came to me through you; for, as you may remember, you obtained for me,

when the prospectus of the 'System of Philosophy' was issued, sundry

subscribers.

"But for my own part, I would rather you did not refer to the matter. At

any rate, if you do, do not do so by name. You will observe, if you turn

to the 'Study of Sociology,' where the matter is referred to, that I have

spoken of the thing impersonally, and not in reference to myself. Though

those who knew something of the matter might suspect it referred to my own

case, yet there is no proof that it did so; and I should be sorry to see

myself identified by name with the matter.—Truly yours, "HERBERT

SPENCER."

But Mr. Spencer had identified Secularists as lacking ethical

scrupulousness, and as I was the reputed founder of that form of

Freethought known as Secularism, some notice became incumbent on my part. The brief article on "Intellectual Morality" in the

Present Day, which I

was editing in 1885, was my answer—the same as appears in my letter to

Mr. Spencer, above quoted.

In 1879 the great recluse meditated going to America. As I was about to do

the same myself, I volunteered to take a berth in the same vessel if I

could be of any service to him on the voyage. He thought, however, that

our sailing in the same ship might cause the constructive interviewers out

there to confuse together the opinions we represented. Yet my friends

would not know his, nor would his friends know mine. But I respected his

scruples, lest his views should become colourably

identified with my own. I had myself a preference for keeping distinct

things separate, and I sailed in another ship and never called at his

hotel but once,

when he was residing at the Falls of Niagara, which I thought was a

curious spot (the noisiest in Canada) to choose for one whose need was

quietude. He would take an entire flat in a hotel that he might be

undisturbed at night. In Montreal, Mr. George Iles gave me the same

splendid, spacious, secluded bedroom which he had assigned to Mr. Spencer

when he was his host there. Professor von Denslow, who told me that he was

the "champion non-sleeper of the United States," asked me to give a

communication from him to Mr. Spencer. That was the reason of my single

visit to him in Canada. At the farewell banquet given to Mr. Spencer in

New York, famous speakers took part; but Henry Ward Beecher, in a speech

shorter than any, excelled them all.

After his return to England, I had several

communications from him on the subject of Co-operation. Like Mr.

Gladstone, he usually made searching inquiries into the details of every

question on which he wrote. One of his letters was as follows:—

"2, LEWES CRESCENT,

"BRIGHTON,

"January 6, 1897.

"DEAR MR. HOLYOAKE,—I should have called upon you before now had I not

been so unwell. I have been kept indoors now for about three weeks. I

write partly to say this and partly to enclose you something of interest

as bearing upon my suggestion concerning piecework in co-operative

combinations.

The experience described by Miss Davenport-Hill bears indirectly, if not

directly, upon them, showing as it does the harmonising effect of

piecework. Truly yours, "HERBERT

SPENCER."

Busied as he was with the recondite application of great principles, he

had practical discernment of the possibilities of Co-operation, unthought

of by those of us engaged in promoting co-partnership in the workshop. Trades unions were mostly against piecework as giving more active workers

an advantage over the others. Mr. Spencer pointed out that in a

co-partnership workshop the fruitfulness of piece work was an advantage to

all. The piece-workers increase the output and profits of the society. The

profits, being equally divided upon wages, the least bright and active

members receive benefit from the piece-workers' industry.

Occasionally Mr. Spencer would come to my door and invite me to drive with

him. Another time when he had visitors—Mrs. Sidney Webb and Prof. Masson,

whom I wished to meet again—he would, if in the winter season, send me a

card from "2, Lewes Crescent, Jan. 24, 1897.—I will send the

carriage for you to-morrow (Sunday) at 12.40.

With the hood up and the leather curtain down you will be quite warm.—H.

S." He would occasionally send me grouse or pheasant for luncheon. Very

Pleasant were the amenities of philosophy.

The first work of Mr. Spencer's which attracted public attention was "Social Statics." Like Mr, Lewes' "Biography of Philosophy," it had a

pristine charm which fascinated young thinkers. Both authors restated

their works, but left behind their charm. Mr. Gladstone's first address to

the electors of Newark contains the germs of his whole and entire career. "Social Statics" contains the element of that philosophy which gave

Spencer the first place among thinkers of all times. Bishop Colenso found

the book in the library of the builder of his Mission Houses in South

Africa. Mr. Ryder, of Bradford, Yorkshire, procured it through me and took

it out with him. It was a book of inspiration to him.

Ten years before "Social Statics" appeared I was concerned with others

in publishing, in the "Oracle of Reason," a theory of Regular Gradation.

Our motto, from Boitard, was an explicit statement of Evolution. Five out

of seven of us were soon in prison, which shows that we did not succeed in

making Evolution attractive. Intellectual photography was then in an

infantine state. Our negatives lacked definition and our best impressions

were indistinct. It was not until Darwin and Spencer arose that the art of

developing the Evolutionary plates came to be understood.

|

|

|

Herbert Spencer |

Before the days of Spencer the world of scientific thought was mostly

without form and void. The orthodox voyagers who set out to sea steered

by a

compass which always veered to a Jewish pole, and none who sailed with

them knew where they were. Rival theologians constructed dogmatic charts,

increasing the confusion and peril. Guided by the pole star of Evolution,

Spencer sailed out alone on the ocean of Speculation and discovered a new

empire of Law—founded without blood, or the suppression of liberty, or

the waste of wealth—where any man may dwell without fear or shame.

The fascination of Mr. Spencer's pages to the pulpit-wearied inquirer was,

that they took him straight to Nature. Mr. Spencer seemed to write with a

magnifying pen which revealed objects unnoticed by other observers. His

vision, like a telescope, descried sails at sea invisible to those on

shore. His pages, if not poems, gleamed with the poetry of facts. His

facts were the handmaids always at hand which explained his principle. His

repetitions do not tire, but are fresh assurances to the reader that he is

following a continuous argument. A pedestrian passing down a long street

is glad to meet the recurrence of its name, that he may know he is still

upon the same road. In Spencer's reasonings there are no byways left open,

down which the sojourner may wander and lose himself. When cross-roads

come in sight, fingerposts are set up telling him where they lead to, and

directing him which to take. Mr. Spencer pursues a new thought, never

loses sight of it,

and takes care the reader does not. No statement goes before without

the proof following closely after.

When the reception was given to me at South Place Institute, London, in

April, 1903, on my eighty-sixth birthday, he had been confined to his

house from the previous August, yet he took trouble to write some words of

personal regard to myself beyond all my expectation. To the end of his

days—save when the weather was inclement—I used to walk up the hill to

his door to inquire as to his health, and when I could not do so, Mr. Troughton would write me word. Mr. Spencer's last letter to me was in

answer to one I had sent him on his birthday. It was so characteristic as

to deserve quoting:

"Thanks for your congratulations; but I should have liked better your

condolences on my longevity."

He wanted no twilight in his life. Like the sun in America, his wish was

to disappear at once below the horizon—having amply given his share of

light in his day.

Like Huxley, Mr. Spencer would not have slept well in Westminster Abbey. He needed no consolation in death; and if he had, there was no one who

knew enough to give it to him. His conscience was his consolation. His one

choice was that his friend Mr. John Morley—than whom none were

fitter—should speak at his death the last words

over him. Mr. Morley being in Sicily, this could not be. The next in

friendship and power of estimate—the Right Hon. Leonard Courtney—spoke

in his stead, at the Hampstead Crematorium.

Mr. Spencer had a radium mind which gave forth, of its own spontaneity,

light and heat. None who have died could more appropriately repeat the

proud lines of Sir Edward Dyer:

|

"My mind to me a kingdom is;

Such perfect joy therein I find

As far exceeds all earthly bliss

That God or Nature hath assign'd." |

CHAPTER XXVI.

SINGULAR CAREER OF MR. DISRAELI

I PREFER the picturesque name of Disraeli which he

contrived out of the tribal designation of "D'Israeli." Had it been

possible he would have transmuted Benjamin into a Gentile name.

Disraeli is far preferable to the sickly title of Beaconsfield, by which

association he sought to be taken as the Burke of the Tories, for which

his genius was too thin.

|

|

|

Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield

(1804-81) |

Disraeli is a fossilised bygone to this generation; though in the

political arena he was the most glittering performer of his day. Men

admired him as the Blondin of Parliament, who could keep his feet on a

tight-rope at any elevation. Others looked upon him as a music-hall Sandow

who could snap into two a thicker bar of bovine ignorance than any other

athlete of the "country party." He was capable of serving any party, but

preferred the party who could best serve him. He was an example how a man,

conscious of power and

unhampered by scruples, could advance himself by strenuous devices of

making himself necessary to those he served.

The showy waistcoat and dazzling jewellery in which he first presented

himself to the House of Commons, betrayed the primitive taste of a Jew of

the Minories, and foreshadowed that trinket statesmanship which captivated

his party, who thought sober, honest principles dull and unentertaining.

Germany and England contemporaneously produced the two greatest

adventurers of the century—Ferdinand Lassalle and Benjamin Disraeli. Both

were Jews. Both had dark locks and faith in jewellery. Both were Sybarites

in their pleasures; and personal ambition was the master passion of each. Both were consummate speakers. Both sought distinction in literature as a

prelude to influence. Both professed devotion to the interests of the

people by promulgating doctrines which would consolidate the power of the

governing classes. Lassalle counselled war against Liberalism, Disraeli

against the Whigs. Lassalle adjusted his views to Bismarck, as Disraeli

did to Lord Derby. Both owed their fortunes to rich ladies of maturity. Both challenged adversaries to a duel, but Disraeli had the prudence to

challenge Daniel O'Connell, who, he knew, was under a vow not to fight

one, while Lassalle challenged Count Racowitza, and was killed.

It was a triumph without parallel to bring to pass that the proud

aristocracy of England should accept a Jew for its master. Not approaching

erect, like a human thing, Disraeli stealthily crept, lizard-like, through

the crevices of Parliament, to the front of the nation, and with the sting

that nature had given him he kept his enemies at bay. No estimate of him

can explain him, which does not take into account his race. An alien in

the nation, he believed himself to belong to the sole race that God has

recognised. The Jew has an industrial daintiness which is an affront to

mankind. He, as a rule, stands by while the Gentile puts his hand to

labour. Isolated by Christian ostracism, the Jew tills no ground; he

follows no handicraft—a Spinoza here and there excepted. The Jew, as a

rule, lives by wit and thrift. He is of every nation, but of no

nationality, save his own. He takes no perilous initiation; he leads no

forlorn hope; he neither conspires for freedom, nor fights for it. He

profits by it, and acquiesces in it; but generally gives you the

impression that he will aid either despotism or liberty, as a matter of

business—as many do who are not Jews. There are, nevertheless, men of

noble qualities among them, and as a class they are as good or better than

Christians would be had they been treated for nineteen centuries as badly

as Jews have been.

Derision and persecution inspire a strong spirit with retaliation, and

absolve him from scrupulous methods of compassing it. Two things the Jew

pursues with an unappeasable passion—distinction and authority among

believers, before whom his race has been compelled to cringe. An ancient

people which subsists by subtlety and courage, has the heroic sense of

high tradition, still looks forward to efface, not the indignity of days,

but of centuries—which imparts to the Jew a lofty implacableness of aim,

which never pauses in its purpose. How else came Mr. Disraeli by that form

of assegai sentences, of which one thrust needed no repetition, and by

that art which enabled him to climb on phrases to power?

A critic, who had taken pains to inform himself, brought charges against

D'Israeli the Elder to the effect that he had taken passages of mark from

the books of Continental sceptics and had incorporated them as his own. At

the same time he denounced the authors, so as to disincline the reader to

look into their pages for the D'Israelian plagiaries. In the novels of D'Israeli the Younger I have come upon passages which I have met with

elsewhere in another form. As the reader knows, Disraeli delivered in

Parliament, as his own, a fine passage from Thiers. So that when Daniel

O'Connell described Disraeli as "the heir-at-law of the impenitent thief

who died on the cross," he was nearer the truth than he knew,

for there was petty larceny in the Disraelian family.

When Sir James Stansfeld entered Parliament he had that moral distrust of

Disraeli, which Lord Salisbury, in his Cranborne days, published a Review to

warn his party against. Sir James (then Mr. Stansfeld) expressed a similar

sentiment of distrust. Disraeli said to a friend in the lobby immediately

after, "I will do for that educated mechanic." The vitriolic spite in the

phrase was worthy of Vivian Grey. He kept his word, and caused Mr. Stansfeld's retirement from the Ministry. It was the nature of Disraeli to

destroy any one who withstood him. At the same time he could be courteous

and even kind to literary Chartists who, like Thomas Cooper and Ernest

Jones, helped to frustrate the Whigs at the poll, which served the purpose

of Tory ascendency, which was Disraeli's chance.

In Easter, 1872, I was in Manchester when Disraeli had the greatest

pantomime day of his life—when he played the Oriental Potentate in the

Pomona Gardens. All the real and imaginary Tory societies that could be

got together from surrounding counties were paraded in procession before

him. To each he made audacious little speeches, which astonished them and,

when made known, caused jubilancy in the city.

The deputation from Chorley reminded him of Mr. Charley, member for

Salford. He exclaimed,

"Chorley and Charley are good names!" When a Tory sick and burial

society came up he said "he hoped they were doing a good business, and

that their future would be prosperous!" When the night came for his

speech, the Free Trade Hall

was crowded. It was said that 2,000 persons paid a guinea each for their

seats.

Mr. Callander, his host, had taken, at Mr. Disraeli's request, some brandy

to the meeting. It was he who poured some into a glass of water. Mr.

Disraeli, on tasting it, turned to him and said in an undertone, "There's

nothing in it." This wounded the pride of his host, who took it as an

imputation of stinginess on his part, and he filled the next glass

plentifully. This was the beginning

of the orator's trouble. For the first fifteen minutes he spoke in his

customary resonant voice. Then husky, sibilant and explosive sentences

were unmistakable. Apprehensive reporters, sitting below him, moved aside

lest the orator should fall upon them. Suspicious gestures set in. An

umbrella was laid near the edge of the platform, that the speaker might

keep within the umbrella range. For this there was a good reason, as the

speaker's habit of raising himself on his toes endangered his balance.

All the meeting understood the case. The orator soon lost all sense of

time. He, who knew so well how to suit performance to occasion, was

incapable

of stopping himself. The audience had come from

distant parts. At nine o'clock they could hear the

railway bell, calling some to the trains. Ten o'clock came, when a larger

portion of the audience was again perturbed by railway warnings. Disraeli

was still speaking. Eleven o'clock came; the audience had further

decreased then, but Disraeli was still declaiming hoarse sentences. It was

a quarter-past eleven before his peroration came to an end; and many, who

wished to have their guinea's worth of Parliamentary oratory, had to sleep

in Manchester that night. Everybody knew the speaker would have ceased two

hours earlier if he could. His host in the chair was much disquieted. His

house was some distance from the city, and he had invited a large party of

gentlemen to meet the great Conservative leader at supper, which had long

been ready. Besides, he was afraid his guest would be unable to appear at

it. Arriving at the house Disraeli asked his host to give him

champagne—"a bottle of fizz" was the phrase he used—which he drank with zest, when,

to the astonishment of his host, he joined the party and was at his best. He delighted every one with his sallies and his satire.

The next morning the city Conservatives were unwilling to speak of the

protracted disappointment of the evening before. The Manchester papers

gave good reports of the long speech, which contained some passages worthy

of the speaker at any time—as when he compared the occupants of the front

bench of the Government in the House of

commons to so many extinct volcanoes. As some members of Her Majesty's

Government were known friends of Mazzini and Garibaldi, the aptitude of

the simile lives in political memory to this day. When the Times report

arrived it was found that a considerable portion of the speech was devoted

to the laudation of certain county families, which were not mentioned in

the Manchester reports, and it was said that Disraeli had dictated his

speech to Mr. Delane before he came down. But though he lost his voice and

his memory, he never lost his wit, for he praised another set of families

that came into his head.

Only in two instances has Mr. Disraeli been publicly charged with errors

of vintage. In his time I heard members manifestly inebriated, address the

House of Commons. On a memorable night Mr. Gladstone said Disraeli had

access to sources of inspiration not open to Her Majesty's Ministers.

|

|

|

Disraeli |

In the Morning Star there appeared next day a passage from Disraeli's

speech, reported in vinous forms of sibilant expression. On that occasion

Lord John Manners carried to him, from time to time during his oration,

five glasses of brandy and water. I saw them brought in. There was the

great table between the two front benches, which Mr. Disraeli said was

fortunate, as he feared Mr. Gladstone might spring upon him. All the

while it was not protection Mr. Disraeli wanted from the table,

but support, for he clutched it as he spoke. Sir John Macdonald, Premier

of Canada, whom I had the honour to visit at Ottawa, not only resembled

Disraeli in features, in the curl of his hair, but in his wit. One night

Sir John made an extraordinary after-dinner speech, which had the flavour

of a whole vintage in it. When Sir John found he had astonished the whole

Dominion, he sent for the reporter, who appeared, trembling with

apprehension. "Young man," said Sir John, "with your talent for reporting

you have a great future before you. But take my advice—never report a

speech in future when you are drunk."

Connoisseurs in art who went to the sale of his effects at Disraeli's

Mayfair house were astonished at the Houndsditch quality of what they

found there. Not a ray of taste was to be seen, not an article worth

buying. The glamour of the Oriental had lain in phrases, not in art.

It was the Liberals who were the champions of the Jews, and who were the

cause of their admission to Parliament. Mr. Disraeli must have had some

generous memory of this. Mr. Bright would cross the floor of the House

sometimes to confer with Disraeli. There must have been elements in his

character in which Mr. Bright had confidence. It was believed to be owing

to his respect for Mr. Bright's judgment that he took no part against

America, when his party did all they could to destroy the cause of the

Union in the great Anti-Slavery War. It ought to be remembered to Disraeli's credit, that he made

what John Stuart Mill called a "splendid concession" of household

suffrage, although he took it back the next night, by the pernicious

creation of the "compound householder." Still, Liberals owe it to him that

household suffrage came to prevail when it did.

Disraeli's attacks upon Peel were dictated by the policy of

self-advancement. He was capable of admiring Peel, but he admired himself

more. Standing outside English questions and interests, he was able to

treat them with an airiness which was a political relief. Yet he could see

that our Colonies might become "millstones round the neck of the Empire"

if we gave them too much of Downing Street, or maybe of Highbury.

To say Disraeli had no conscience would be to say more than any man has

knowledge enough to say of another; but he certainly never gave the

public the impression that he had one. He devised the scheme of giving the

Queen the title of "Empress." Mr. Gladstone opposed it as dangerous to

the dynasty, lowering its dignity to the level of Continental Emperorship,

and taking from the Crown the master jewel of law, which has been more or

less its security and glory for a thousand years.

Disraeli seemed to care for the Queen's favour—nothing for the integrity

of the Crown. He

declared himself a Christian, and said in the presence of the Bishop of

Oxford, with Voltairean mockery, that he was "on the side of the angels,"

and elsewhere described Judas as an accessory to the crucifixion before

the act, and to that ignoble treachery all Christians were indebted for

their salvation—an idea which could never have entered a Gentile mind. This was pure Voltairean scorn.

In his last illness he was reported to have had three different kinds of

physicians—allopath, hydropath, homoeopath; and had he chosen the

spiritual ministration of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Chief Rabbi,

and Mr. Spurgeon, no one would have been surprised at his sardonic

prudence.

I had admiration, though not respect, for his career. Yet I was for

justice being done to him. When it was thought the Tories would prevent

his accession to the Premiership, which was his right by service, I was

one of those who cheered him in the lobby of the House of Commons, to show

that adversaries of his politics were against his being defrauded of the

dignity he had won.

How was it that Disraeli's standing at Court was never affected by what

would be deemed seditious defamation of the Crown in any other person? When I mentioned in America the revolutionary license of his tongue in

declaring the Queen to be

physically and morally incapable of governing, the statement was received

with incredulity. The reporters who took down his Aylesbury speech

containing the astounding words hesitated to transcribe them, and one

asked permission to read the passage to Mr. Disraeli, who assented to its

correctness, and the words appeared in the Standard and Telegraph of

September 27, 1871. The Times and Daily News omitted the word "morally,"

deeming it incredible. But it was said. His words were: "We cannot

conceal from ourselves that Her Majesty is physically and morally

incapacitated from performing her duties." This meant that Her Majesty was

imbecile—a brutal thing to suggest, considering family traditions.

At a Lord Mayor's banquet Mr. Disraeli gave an insulting and defamatory

account of the Russian Royal Family and Government, and boasted, like an

inebriate Jingo, of England's capacity to sustain three campaigns against

that Power. As the Queen had a daughter-in-law a member of the Royal House

of Russia, this wanton act of international offensiveness must have

produced a sensation of shame and pain in the English Royal Family. I well

remember the consternation and disapproval with which both speeches were

regarded by the people. Whatever even Republicans may think of the theory

of the Crown, they are against any personal outrage upon it. Yet Mr.

Gladstone, who was always forward to sustain, by

graceful and discerning praise, the interest of the Royal Family, and

procure them national grants, to which Mr. Disraeli could never have

reconciled the nation, was simply endured by Her Majesty, while to Mr.

Disraeli ostentatious preference was shown. It was said in explanation

that Mr. Gladstone had no "small talk" with which Mr. Disraeli

entertained his eminent hostess. It was not "small talk," it was Tory

talk, which the Queen rewarded.

I am of Lord Acton's opinion, that Mr. Disraeli was morally insupportable,

though otherwise astonishing. The pitiless resentment of "Vivian Grey"

towards whoever stood in his way was the prevailing characteristic of the

triumphant Jew. Like other men of professional ambition, he had the charm

of engaging amity to those who were for the time being no longer

impediment to him. When showing distress at a few drops of rain falling,

news was brought Her Majesty that Mr. Gladstone had returned from a voyage

and addressed a crowd on the beach. Disraeli exclaimed with pleasant

gaiety,

"What a wonderful man that Gladstone is. Had I returned from a voyage I

should be glad to go to bed. Mr. Gladstone leaps on shore and makes a

speech."

The moral of this singular career worth remembering, is that genius and

versatility, animated by ambition without scruple, may attain

distinction without principle. It can win national admiration,

but not public affection. All it can accomplish is to leave behind a name

of sinister renown. If we knew all, no doubt Lord Beaconsfield had, apart

from the exigencies of ambition, personal qualities commanding esteem.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHARACTERISTICS OF JOSEPH COWEN

-I-

POLITICAL readers will long remember the name of

Joseph Cowen, who won in a single night the reputation of a national

orator. All at once he achieved that distinction in an assembly

where few attain it. After a time he retired to his tent and never

more emerged from it. The occasion of his first speech in Parliament

was the introduction of the Bill for converting the Queen into an Empress.

Queen was a wholesome monarchical name, which implied in England supremacy

under the law; while Empress, alien to the genius of the political

constitution, is a military title of sinister reputation, and implies a

rank outside and above the law. Like Imperialism, it connotes

military government, which, in the opinion of the free and prudent, is the

most odious, dangerous, and costly of all governments. Mr. Cowen

entertained a strong repugnance to the word "Empress," which might become

a prelude to Imperialism—as it has done.

|

|

|

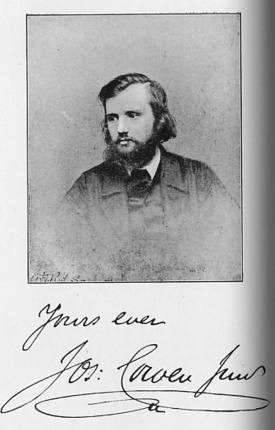

Joseph Cowen

(1831-1900) |

Mr. Cowen's father, who preceded him in the House of Commons,

was scrupulous in apparel, never affecting fashion, but keeping within its

pale. His son was not only careless of fashion—he despised it.

He employed local tailors, from neighbourliness, and was quite content

with their craftsmanship. He never wore what is called a "top" hat,

but a felt one, a better shape than what is known now as a "clerical" hat.

It was thought he would abandon it when he entered Parliament, but he did

not. He commonly left it in the cloak-room. He had no wish to

be singular. His attire was as natural to him as his skin is to an

Ethiopian. His headgear imperilled his candidature, when that came

about.

He had been two years in Parliament before he addressed it.

When he rose many members were standing impatient for division and crying

"Divide! Divide!!" Mr. Cowen, being a small man, was not at

once perceived, but his melodious, honest, and eager voice arrested

attention, though his Northumbrian accent was unfamiliar to the House.

It was as difficult to see the new orator as to see Curran in an Irish

Court, or Thiers in the French Chamber. Disraeli glanced at him

through his eyeglass, as though Mr. Cowen was one of Dean Swift's

Lilliputians, and of one near him he asked contemptuously, as a Northern

burr broke upon his ear, "What language is the fellow talking?"

The speech had all the characteristics of an oration,

historical, compact, and complete—though brief. In it he said three

things never heard in Parliament before. One was that the "Divine

right of kings perished on the scaffold with Charles I." Another was

that "the superstition of royalty had never taken any deep hold of the

English people." The third was to describe our august ally, the

Emperor Napoleon III., as an "usurper." The impression the speech

made upon the country was great. It so accorded with the popular

sentiment that some persons paid for its appearance as an advertisement in

the Daily News and other papers of the day, and the speaker

acquired the reputation of an orator by a single speech. Mr.

Disraeli's contemptuous reception of it did not prevent him, at a later

date, from going up to Mr. Cowen, when he was standing alone by a fire,

and paying him some compliment which made a lasting impression upon him.

Mr. Disraeli had discernment to recognise genius when he saw it, and

generosity enough to respect it when not directed against himself.

If it were, he was implacable.

For years, as I well knew, Mr. Cowen spent more money for the advancement

and vindication of Liberalism than any other English gentleman. He was the

most generous friend of "forlorn hopes" England has known. How many

combatants has he aided; how many has he succoured; how many has he saved! If

the other world be human like this, what crowds of grateful spirits of

divers climes must have rushed to the threshold of heaven to welcome him

as he entered.

Penniless, and his crew foodless, Garibaldi steered his vessel up the

Tyne. Mr. Cowen was the only man in England Garibaldi then sought or

confided in. Before he left the Tyne, Mr. Cowen, on behalf of subscribers

(of whom many were pitmen), presented Garibaldi with a sword which cost

£146. Goldwin Smith says, in his picturesque way, Henry III. had a "waxen

heart." Mr. Cowen had an iron heart, steeled by noble purpose. He knew no

fear, physical or mental. Not like my friend, George Henry Lewes, whose

sense of intellectual right was so strong that he never saw consequences. Cowen did see them, and disregarded

them; he "nothing knew to fear, and nothing feared to know"—neither

ideas nor persons. How many men, not afraid of ideas, are much afraid of

knowing those who have them? Unyielding to the high, how tender he was to

the low!

Riding home with him one night, after a stormy meeting in Newcastle, when

we were near to Stella House (he had not gone to reside in the Hall then)

the horse suddenly stopped. Mr. Cowen got out to see what the obstruction

was, and he found it was one of his own workmen lying drunk across the

road. His master roused him and said: "Tom,

what a fool thou art! Had not the horse been the more sensible beast, thou hadst been killed." He would use these Scriptural pronouns in speaking to

his men. The man could not stand, and Mr. Cowen and the coachman carried

him to the door of another workman, called him up, and bade him let Tom

lie in his house till morning. Then we drove on.

Another time a workman came to Mr. Cowen for an advance of thirty

shillings. Being asked what he wanted the money for, the man answered: "To

get drunk, sir; I have not been drunk for six weeks." "Thou knowest,"

said Mr. Cowen, "I never take any drink, because I think the example good

for thee. Thou will go to Gateshead Fair, get locked up, and I shall have

to bail thee out. There is the money; but take my advice, get drunk at

home, and thy wife will take care of thee." How many employers possess

workmen having that confidence in them to put such a question as this

workman did, without fear of losing their situation? No workman lied, or

had need to lie, to Mr. Cowen. He had the tolerance and tenderness of a

god.

When I was ill in his house in Essex Street, Strand, he would come up at

night and tell me of his affairs, as he did in his youth. He had for some

time been giving his support to the Conservative side. I said to him, "Disraeli is dead. Do you

not see that you may take his place if you will? It

is open. His party has no successor among them.

He had race, religion, and want of fortune against him. You have none of

these disadvantages against

you. You are rich, and you can speak as Disraeli

never could. He had neither the tone nor the fire

of conscience—you have both. You have the ear of the House, and the

personal confidence of the

country, as he never had. In his place you would

fill the ear of the world." He thought for a time on what I said to him;

then his answer was: "There is one difficulty—I am not a Tory."

I saw he was leaving the side of Liberalism and that he would inevitably

do Conservative work, and I was wishful that he should have the credit of

it. He was under a master passion which carried him he knew not whither.

It was my knowledge of Mr. Cowen, long before that night, that made me oft

say that a Tyneside man had more humility and more pride than God had

vouchsafed to any other people of the English race. Until middle life Mr.

Cowen was as his father, immovable in principle; afterwards he was as his

mother in implacableness. That is the explanation of his career.

The "passion" referred to—never avowed and never obtruded, but which "neither slumbered nor slept"—was ambition. It might be called Paramountcy—that

dangerous war-engendering word of Imperialism—which only the arrogant

pronounce, and only the subjugated submit to.

The Cowen family had no past but that of

industry, and in Mr. Cowen's youth the "slings and arrows of outrageous"

Toryism, shafts of arrogance, insolence, and contempt, flew about him. He

inherited from his mother a proud and indomitable spirit, and resolved to

create a Liberal force which should withstand all that—and he did. Then,

when he came to be, as he thought, flouted by those whom he had served

(the common experience of the noblest men), he at length resented and

turned against himself. He had reached the heights where he had been

awarded an imperishable place, and then descended in resentment to mingle

and be lost in the ignominious faction whom he had defeated and despised.

Those who had enraged him were not, as we shall see, worth his resentment.

It was not for "a handful of silver" he left us—for he had plenty—nor

for "a ribbon to stick in his coat," for he would not wear one if offered

a basketful. It was just indignation, stronger than self-respect.

Not all at once did the desire of control assume this form. By his natural

nobility of nature he inclined to the view that all the supremacy inherent

in man is that of superior capacity, to which all men yield spontaneous

allegiance.

Some time elapsed before the bent of his mind became apparent. Possibly it

was not known to himself.

When a young man, he promoted and maintained

two or three journals, in which he also wrote himself, without suggesting

to others the passion for journalism by which he was possessed. Some years

later, when proofs of one of his speeches which a reporter had taken down,

and Mr. Cowen had himself corrected, passed through my hands, I was struck

with the dexterity with which he put a word of fire into a tame sentence,

infused colour into a pale-faced expression, and established a pulse in an anæmic

one. It was clear that he had the genius of speech in him and was

ambitious of distinction in it.

Mr. Cowen's father was a tall, handsome man of the Saxon type, which goes

steadily forward and never turns back. He always described himself as a

follower of Lord Durham, and was out on the Newcastle Town Moor in 1819,

at great meetings in support of the Durham principles. His mother was

quite different in person, both in stature and appearance; somewhat of

the Spanish type—dark, and mentally capable of impassable resolution. Her

son, Joseph, with whom we are here concerned, had dark, luminous eyes

which were the admiration of London drawing-rooms—when he could be got to

enter them. His eldest sister, Mrs. Mary Carr, was as tall as her father,

with the complexion of her mother. I used to compare her to Judith, the

splendid Jewess who slew Holofernes. She used to say her brother Joseph

had her mother's spirit,

and that a "Cowen never changed." Her brother never changed in his

purpose of ascendency, but

when inspired by resentment he could change his party to attain his

end—as I have seen done in the House of Commons many times in my day. This is why I have said that in the early part of Mr. Cowen's life he was

his father—placid but purposeful. In the second half he was his

mother—resentful and implacable when affronted by non-compliance where

he expected and desired concurrence. But I have known many excellent men

who did not take dissent from their opinions in good part.

How fearless Mr. Cowen was, was shown in his conduct when a dangerous

outbreak of cholera occurred in Newcastle. People were dying in every

street and lane, but he went out from Blaydon every morning at the usual

time, and walked through the infected streets and passages into Newcastle,

to his offices on the quay, being met on his way by persons in distress,

from death in their houses, who knew they were sure of sympathy and

assistance from him. The courage of his unfailing appearance in his

ordinary way saved many from depression which might have proved fatal to

them. When a wandering guest fell ill at his home, Stella House, Blaydon,

he was sure of continued hospitality until his recovery. Mr. Cowen's voice

of sympathy and condolence was the tenderest I ever heard from human lips.

A poor man, who lived a good deal upon the moors, was charged with

shooting a doctor, and would have been hanged but for Mr. Cowen defending him by legal aid. He thought the police had apprehended him

because he was the most

likely, in their opinion, to be guilty. He was poor,

friendless, and often houseless. The man did not

seem quite right in his mind. After his acquittal, Mr. Cowen took him into

his employ, and made him his gardener. The garden was remote and solitary. I often passed my mornings in it, not without some personal misgiving. Mr.

Cowen eventually enabled the man to emigrate to America, where a little

eccentricity of demeanour does not count.

In the political estrangements of Mr. Cowen, it must be owned he had

provocations. A party of social propagandists came to Newcastle, whom he

entertained, as they had never been entertained before, at a cost of

hundreds of pounds, and was at great expense to give publicity to their

objects. They left him to defray some bills they had the means of paying. Years later, when they came again into the district, he did no more for

them in the former way. He had conceived a distrust of them. Another time

he was asked by persons whom he was willing to aid, to buy some premises

for them, as they would be prejudiced at the auction if they appeared in

person. Mr. Cowen bought the property for £5,000 They changed their minds

when it was bought, and left Mr. Cowen, who did not want it, with it upon

his hands. He did not resent it, as he might have done, but it was an act

of

meanness which would have revolted the heart of an archangel of human

susceptibility.

When the British Association first carne to Newcastle, Mr. Cowen spent

more than £500 in giving publicity to their proceedings. He brought a

railway carriage full of writers and reporters from London, that the

proceedings of every section should be made known to the public. He had

personal notices written of all the principal men of science who came

there, and when he asked for admission of his reporters, he was charged

£19 for their tickets. As I was one of those engaged in the

arrangements, I shared his indignation at this scientific greed and

ingratitude. In all the history of the British Association, before and

since, it never met with the enthusiasm, the liberality and publicity the

Newcastle Chronicle accorded it.

In the days of the great Italian struggle, little shoals of exiles found

their way to England. Learning where the great friend of Garibaldi dwelt,

they found their way to Newcastle, and many were directed there from

different parts of England. Many times he was sent for to the railway

station, where a number of destitute exiles had arrived. He relieved their

immediate wants and had them provided for at various lodgings, until they

were able to get some situation elsewhere. I think Mr. Cowen began to tire

of this, as he thought exiles were sometimes sent to him by persons who

ought to have taken part of the

responsibility themselves, but who seemed to consider that his was the

purse of the Continent.

|

|

|

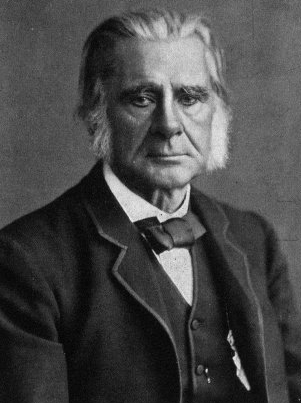

William Edward Forster

(1818-86) |

Once when Mr. Cowen attended a political conference in Leeds, he received

as he entered the room marked attention, as he was known to be the leader

of the Liberal forces of Durham and Northumberland. But Mr. W. E. Forster,

who was present, took no notice of him, though Mr. Cowen had rendered him

great political service. When Mr. Bright saw Mr. Cowen he cordially

greeted him. Immediately Mr. Forster, seeing this, stepped up also and

offered him compliments, which Mr. Cowen received very coldly without

returning them, and passed away to his seat. Mr. Cowen's impression was

that as Mr. Forster had suffered him to pass by without recognition, he

did not want to know him before that assembly; but when Mr. Forster saw

Mr. Bright's welcome of his friend, he was willing to know him. Mr.

Forster, as I had reason to know afterwards, was capable of such an

action, where recognition stood in the way of his interests, [47] but it was

not so on this occasion. Mr. Forster was short-sighted, and simply did not

see Mr. Cowen when he first passed him. But it happened that he did see

him when Mr. Bright stepped forward to speak to him, and there was no

slight of Mr. Cowen intended. Yet from that hour Mr. Cowen entertained a

contempt for Mr. Forster, and would neither meet him nor speak to him. One

day Mr. Cowen and I were at a railway station, where Mr. Forster appeared

in his volunteer uniform. We had to wait some time for the train. Mr.

Cowen asked me to walk with him as far as we could from where Mr. Forster

stood, that we should not pass near him. Some years later, at the House of

Commons, Mr. Forster asked Mr. Cowen to walk with him in the Green Park,

as he wished to speak with him. After two hours Mr. Cowen returned

reconciled. He never told me the cause of it, which he should have done,

as I had taken his part in the long years of resentment. I relate the

incident as showing how personal misconception produces political

estrangement in persons and parties alike.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHARACTERISTICS OF JOSEPH COWEN

-II-

BUT the act which most wounded him occurred at the Elswick works of Lord

Armstrong. Mr. Cowen was returning one day in his carriage at a time of

political excitement. Some of the crowd threw mud upon his coach, and, if

I remember rightly, broke the windows. Just before, when the workmen were

on strike, they went to Mr. Cowen—as all workmen in difficulties did. He

found they did not know their own case, nor how to put it. He employed

legal aid to look into the whole matter and make a statement of it. Mr.

Cowen became their negotiator, and obtained a decision in their favour. The whole expense he incurred on their behalf was £150. Services of this

kind, which had been oft rendered, should have saved him from public

contumely at their hands.

At that time Mr. Cowen was giving the support of his paper against

Liberalism, which he had so long defended and commended, which was an

incentive to the outrage. Still, the sense of gratitude for the

known services rendered to workers, which he continued irrespective of his

change of opinion, should have saved him from all personal disrespect.

The subjection of the Liberals in Newcastle in the days of

his early career, and the arrogant defamation with which it was assailed,

were what determined him to create a defiant power in its self-defence.

He bought the Newcastle Chronicle, an old Whig paper.

He published it in Grey Street, afterwards in St. Nicholas' Buildings, and