|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER XVI.

THE THREE NEWMANS

IN one of the last conversations I had the pleasure

to hold with Mr. Gladstone, I referred to the "three Newmans" and their

divergent careers. He said he never knew there were "three."

He knew John Henry, the Cardinal (as he afterwards became), at Oxford.

He knew Francis William there, who had repute for great attainments,

retirement of manner, and high character; but had never heard there was a

third brother, and was much interested in what I had to tell him.

The articles of Charles Newman I published in the Reasoner, and

their republication by the late J. W. Wheeler, were little known to the

general public, who will probably hear of them now for the first time.

|

|

|

|

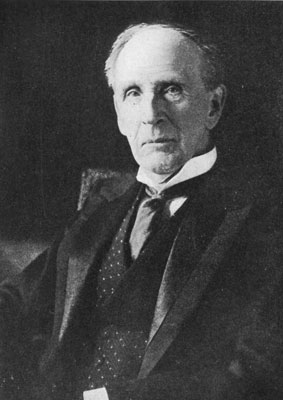

John Henry Newman

(1801-90) |

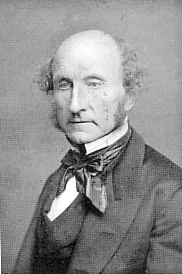

Francis William Newman

(1805-97) |

Though I name "three Newmans," this chapter relates chiefly

to the one I best knew, Francis William, known as Professor Newman.

The eldest of the three was John Henry, the famous Cardinal. The

third brother, Charles, was a propagandist of insurgent opinion.

Francis was a pure Theist, John was a Roman Catholic, and Charles a

Naturist, and nothing besides; he would be classed as an Agnostic now.

Francis William was the handsomest. He had classical features, a

placid, clear, and confident voice, and an impressive smile which lighted

up all his face. John Henry manifested in his youth the dominancy of

the ecclesiastic, and lived in a priestly world of his own creation, in

which this life was overshadowed by the terrors of another unknown. Francis believed in one sole God—not the head of a firm. His Theism was

of such intense, unquestioning devotion, of such passionate confidence, as

was seen in Mazzini and Theodore Parker, of America. Voltaire and Thomas

Paine were not more determined Theists. In all else, Francis was human. Charles believed in Nature and nothing more. In sending me papers to print

in the Reasoner on "Causation in the Universe," he would at times say,

"My mind is leaving me, and when it returns a few months hence, I will

send you a further paper." Like Charles Lamb's poor sister, Mary, who used

to put her strait waistcoat in her basket and go herself to the asylum,

when she knew the days of her aberration were approaching, Charles Newman

had premonition of a like kind. He had the thoroughness of thought of his

family. The two brothers—the Cardinal and the Professor united to supply

Charles with an income sufficient for his needs. The Cardinal, though he

knew Charles' opinions, readily joined.

When some questioning remark on Professor Newman was made incidentally in

the House of Commons, in consequence of his uncompromising views, the

Cardinal wrote

saying that "for his brother's purity he would die," which, considering

their extreme divergence of opinion, was very noble in the Cardinal.

Professor Newman, I believe, wrote more books, having regard to their

variety and quality, than any other scholar of his time. Science, history,

poetry, theology, political

economy, mathematics, travel, translations—the Iliad of Homer—among them

a Sanscrit dictionary. He wrote many pamphlets and spoke for the humblest

societies,

regardless of the amazement of his eminent contemporaries and associates. On questions relating to marital morality, he did not hesitate to publish

leaflets. I

published a series of letters for him in the Reasoner—now some fifty

years ago, so we were long acquainted. These earlier communications came

to me at a time when the

authorities of University College in London, where he was Professor of

Latin, were being called upon to consider whether his intellectual

Liberalism might deter parents from

sending their sons there. But it was bravely held that the University had

no cognisance of the personal opinions of any professor. Like Professor

Key, Mr. Newman took an open interest in public affairs. Though variedly

learned, Professor Newman's style of speech, to whomever addressed by

tongue or pen, was fresh,

direct, precise, and lucid.

Mr. Newman's quarto volume on Theism, written in metre, is the greatest

compendium of Theistical argument published in my time, and until Darwin

wrote, no entirely

conclusive answer was possible.

Francis Newman had a travelling mind. From the time when I published his "Personal Narrative" of his early missionary experience at Aleppo, he

grew, year by year, more

rationalistic in his religious judgment. In one of his papers, written in

the year of his death, he said: "It may be asked, 'Is Mr. Newman a

disciple of Jesus?' I

answer, 'Of all nations that I know, that have a religion established by

law, I have never seen the equal to what is attributed to Jesus himself. But much is attributed to

Him—I disapprove of.' On the whole, if I am asked, 'Do you call yourself

a Christian?' I say, in contrast to other religions, 'Yes! I do,' and

so far I must call myself a

Christian. But if you put upon me the words Disciple of Jesus, meaning the

believing all Jesus teaches to be light and truth I cannot say it, and I

think His words variously

unprovable. Now all disciples, when they come to full age, ought to seek

to surpass their masters. Therefore, if Jesus had faults, we, after more

than two thousand years'

experience, ought to

expect to surpass Him, especially when an immense routine of science has

been elaborately built up, with a thousand confirmations all beyond the

thought of Jesus."

What a progressive order of thought would exist now in

the Christian world had Mr. Newman's conception of discipleship prevailed in the Churches!

Mr. Newman's words about myself, occurring in his work on "The Soul," I

remember with pride. They were written at a time when I had an ominous

reputation among

theologians. When residing at Clifton as a professor, Mr. Newman came down

to Broadmead Rooms at Bristol, and took the chair at one of my lectures,

and spoke words on

my behalf which only he could frame. But he was as fearless in his

friendship as he was intrepid in his faith. He wrote to me, April 30,

1897, saying: "I appeal to your

compassion when I say, that the mere change of opinion on a doubtful fact

has perhaps cost me the regard of all who do not know me intimately." The

"fact" related

to the probability

of annihilation at death. He regretted the loss of friendship, but never

varied in his lofty fidelity to conscience. Whatever might be his interest

in a future life, if it were

the will of God not to concede it, he held it to be the duty of one who

placed his trust in Him to acquiesce. The spirit of piety never seemed to

me nobler, than in this unusual

expression of unmurmuring, unpresuming resignation.

His first wife, who was of the persuasion of the Plymouth Brethren, had

little sympathy with his boldness and fecundity of thought. Once, when he

lived at Park Village,

Regent's Park, his friend, Dr. James Martineau, came into the room; she

opened the window and stepped out on to the lawn, rather than meet him. Mr. Newman was

very tender as to her scruples, but stood by his own. When I visited him,

he asked me, from regard to her, to give the name of "Mr. Jacobs"—the

name I used when a teacher

in Worcester in 1840, where I lectured under my own name and taught under

another.

On February 12, 1897, Mr. Newman wrote:—"MY DEAR HOLYOAKE,—I am not

coming round to you, though many will think I am. On the contrary, I hope

you are half

coming round to me, but I have no time to talk on these matters." He then

asked my advice as to his rights over his own publications, then in the

hands of Mr. Frowde,

printer, of Oxford; but with such care for the rights of others, such

faultless circumspection as to the consequences to others in all he wished

done, as to cause me

agreeable surprise at the unfailing perspicacity of his mind, his

unchanging, scrupulous, and instinctive sense of justice.

He regarded death with the calmness of a philosopher. He wrote to me April

30, 1897: "Only those near me know how I daily realise the near approach

of my own death (he

was then ninety-three). I grudge every day wasted by things unfinished which remain for me to do." No apprehension, no fear, and he

wished I could "appear before him, with a document drawn up," by which he

could consign to me the

custody of all the works under his control. At the time, as he said, he

might "easily be in his grave" before I could accomplish his wishes. He

says in another letter

that his "wife, like himself, abhorred indebtedness." He provided for the

probable cost of everything he wished done. His sense of honour remained

as keen as his

sense of faith. He was a gentleman first and a Christian afterwards.

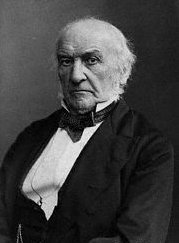

Mr. Gladstone told me he was under the impression that he had, in some way

unknown to himself,

lost the friendship of Mr. Newman, from whom he had not heard for several

years; and Mr. Newman was under an impression that Mr. Gladstone's silence

was occasioned by

disapproval of his published views of the "Errors of Jesus"—an error of

assumption respecting Mr. Gladstone into which Mr. Newman might naturally,

but not excusably,

fall; for Mr. Newman should have known that Mr. Gladstone had a noble

tolerance equal to his own, or should personally have tested it, by letter

or otherwise, before nurturing

an adverse conjecture. I mentioned the matter to Mr. Gladstone, and found

Mr. Newman's surmise groundless. At the same time I gave him a copy of Mr.

Francis Newman's

"Secret Songs" (as one copy given to me was called) which revealed

to Mr. Gladstone a devotional spirit he did not, as he said, imagine could

co-exist in one whose faith was so divergent to his own.

The following letter, which has autobiographical value, may interest the

reader:—

"NORWOOD VILLA, 15, ARUNDEL CRESCENT,

"WESTON-SUPER-MARE.

March 22, 1890.

"DEAR MR. GEORGE JACOB HOLYOAKE,—I had

no idea of writing to Mr.

Gladstone, yet am glad to hear that you gave him my 'Secret Hymns.' Probably my contrast to

my brother, the late Cardinal, always puzzled him. That we were in painful

opposition ever since 1820 had never entered his mind, much less that this

opposition

made it impossible to me to endure living in Oxford, which also would have

been my obvious course.

"I did send my 'Paul of Tarsus' to Mr. Gladstone, which partially opened

his eyes. For my brother's first pretentious religious book was against

the Arians, which I think I read

at latest in 1832. Mr. Gladstone has written that my brother's secession

to Rome was the greatest loss that the English Church ever suffered. Of

what kind was the loss

my little book on 'Paul' indirectly states, in pointing out that, as our

English New Testament shows, Paul in his own epistle plainly originated

the doctrine, three centuries

later called Arianism, and held by all the Western Church until young

Athanasius introduced his new and therefore 'false' doctrine.

My brother, with Paul's epistle open before him, condemned the doctrine of

Arian, and did not know that it was the invention of Paul, and thereby

prevailed in the whole

Western Church. Moreover, I read what I cannot imagine met Mr. Gladstone's

eyes, that 'it is not safe to quote any Pre-Athanasian doctrines

concerning the Trinity, since

the Church had not yet taught them how to express themselves.' After this,

could Mr. Gladstone, as a decent scholar, mourn over my brother's

loss to

the Church? I hope

Mr. Gladstone can now afford time to read something of the really early

Christianity. He will find the Jerusalem Christianity perishing after the

Roman revolt, and

supplanted by Pauline fancies (not Christian at all) and by Pauline

morality, often better than Christian. To me our modern problem is to

eschew Pauline fancies and

further to improve on Pauline wisdom.

"But since I have reached the point of being unable to take Human

Immortality as a Church axiom, I cannot believe that the problem is above

fully stated, or that Christianity

deserves to become coetaneous with man's body.

"Perhaps I ought to thank you more, yet I may have said too much.—Yours

truly, "F. W. NEWMAN,"

One day as Mr. Newman was leaving my room in Woburn Buildings, he looked

round and said: "I did not think there were rooms so large in this

place"; and then descending the stairs, as though the familiarity of the

remark was more than an impulse, he said: "Do you think you could join

with me in teaching the

great truth of Theism?" Alas! I had to express my regret that my belief

did not lie that way. Highly as I should think, and much as I should value

public association with Mr.

Newman, I had to decline the opportunity. If the will could create

conviction, I should also have accepted Mazzini's invitation—elsewhere

referred to—for Theism never seemed

so enchanting in my eyes as it appeared in the lives of those two

distinguished thinkers who were inspired by it.

CHAPTER XVII.

MAZZINI IN ENGLAND-INCIDENTS IN HIS CAREER

GIUSEPPE MAZZINI, whom

Englishmen know as Joseph Mazzini, was born in Genoa, June 22, 1805, and

died in Pisa, March 10, 1872. He spent the greater part of forty years of

his marvellous life in London. [30] Some incidents of his English career,

known to me, may increase or confirm the public impression of him.

Never strong from youth, abstemious, oft from privation, and always from

principle, he was as thin as Dumas describes Richelieu. Arbitrary

imprisonment, which twice befel him, and many years of voluntary

confinement, imposed upon himself by necessity of concealment—living and

working in a small room, whence it was dangerous for him to emerge by day

or by night—were inevitably enervating. When he first came to London in

1837 he brought with him three exiles, who depended upon his earnings for

subsistence. The slender income supplied him by his mother might have

sufficed for his few wants, [31] but aid for others and the ceaseless cost of

the propaganda of Italian independence, to which he devoted himself, had

to be provided by writing for reviews. At times cherished souvenirs had to

be pledged, and visits to money-lenders had to be made.

It was the knowledge all his countrymen had that he sought nothing for

himself, never spared himself in toil or peril, that was the source of his

influence. He wrote: "We follow a path strewn with sacrifices and with

sorrows." But all the tragedies of his experience we never knew until

years after his death, when his incomparable "Love Letters" were

published in the Nineteenth Century, No. 219, May, 1895.

He appeared to others to have "the complexion of a student," the air of

one who waited and listened. As Meredith said, it was not "until you meet

his large, penetrating, dark eyes, that you

were drawn suddenly among a thousand whirring wheels of a capacious, keen,

and vigorous intellect."

When anything had to be done, in my power to do, I was at his command. I

had numerous letters from him. His errorless manuscript had the appearance of Greek writing. Two letters "t" and "s," such as no other man

formed, were the signs of his hand and interpreters of his words. Of all

the communications I ever received from him or saw, none had date or

address, save one letter which had both. Many sought for conversation, if

by chance they were near him, or by letter, or interview—for ends of

their own. But no one elicited any information he did not intend to give. His mind was a fortress into which no man could enter, unless he opened

the door.

Kossuth astonished us by his knowledge of English, but he knew little of

the English people. Louis Blanc knew much; but Mazzini knew more than any

foreigner I have conversed with. Mazzini made no mistake about us. He

understood the English better than they understood themselves—their

frankness, truth, courage, impulse, pride, passions, prejudice,

inconsistency, and limitation of view. Mazzini knew them all.

His address to the Republicans of the United States (November, 1855) is an

example of his knowledge of nations, whose characteristics were as

familiar to him as those of individuals are to their associates, or as

parties are known to politicians in their own country. There may be seen his wise way of looking

all round an argument in stating it. No man of a nature so intense had so

vigilant an outside mind.

He knew theories as he knew men, and he saw the theories as they would be

in action. There was no analysis so masterly of the popular

schools—political and socialist—as that which Mazzini contributed to the

People's Journal. His criticisms of the writings of Carlyle, published in

the Westminster Review, explained the excellencies and the pernicious

tendencies—political and moral—of Carlyle's writing, which no other

critic ever did. But Mazzini wrote upon art, music, literature, poetry,

and the drama. To this day the public think of him merely as a political

writer—a sort of Italian Cobbett with a genius for conspiracy.

The list of his works fills nearly ten pages of the catalogue of the

British Museum.

Under other circumstances his pen would have brought him ample

subsistence, if not affluence. Much was written without payment, as a

means of obtaining attention to Italy. It was thus he won his first

friends in England.

No one could say of Mazzini that he was a foreigner and did not understand

us, or that the case he put was defective through not understanding our

language. The Saturday Review, which agreed with nobody, said, on reading Mazzini's "Letter to Louis Napoleon," which was written in English,

"The man can write." The finest State papers seen in Europe for

generations were those which Mazzini, when a Triumvir in Rome,

wrote—notably those to De Tocqueville. De Tocqueville had a great name

for political literature, but his icy mystifications melted away under Mazzini's fiery

pen of principle, passion, and truth. This wandering, homeless, penniless,

obscure refugee was a match for kings.

Some day a publisher of insight will bring out a cheap edition of the five

volumes of his works, issued by S. King and Co., 1867, and "dedicated to

the working classes" by P. A. Taylor, which cost him £500, few then caring

for them. Mrs. Emilie Ashurst Venturi was the translator of the five

volumes, which were all revised by Mazzini. The reader therefore can trust

the text.

Mazzini did me the honour of presenting to me his volume on the "Duties of

Man," with this inscription of reserve: "To my friend, G. J. Holyoake,

with a very faint hope." Words delicate, self-respecting and suggestive. It

was hard for me, with my convictions, to accept his great formula, "God

and the People." It was a great regret to me that I could not use the

words. They were honest on the lips of Mazzini. But I had seen that in

human danger Providence procrastinates. No peril stirs it, no prayer

quickens its action. Men perish as they supplicate. In danger the people

must trust in themselves.

Thinking as I did, I could not say or pretend otherwise.

Mazzini one day said to me, "A public man is often

bound by his past. His repute for opinions he has maintained act as

a restraint upon avowing others of a converse nature." This feeling

never had influence over me. Any one who has convictions ought to

maintain a consistency between what he believes, and what he says and

does. But to maintain to-day the opinions of former years, when you

have ceased to feel them true, is a false, foolish, even a criminal

consistency. To conceal the change, if it concerns others to know

it, is dishonest if it is misleading any persons you may have influenced.

The test, to me, of the truth of any view I hold, is that, I can state it

and dare the judgment of others to confute it. Had I new views—theistical or otherwise—that I could avow with this

confidence, I should have the same pleasure in stating them as I ever had

in stating my former ones. When I look back, upon opinions I published

long years ago, I am surprised at the continuity of conviction which,

without care or thought on my part, has remained with me. In stating my

opinions I have made many changes. Schiller truly says that "Toleration

is only possible to men of large information." As I came to know more I

have been more considerate towards the views, or errors, or mistakes of

others, and have striven to be more accurate in my own statement of

them, and more fair towards adversaries. That is all. Mazzini understood

this, and did not regard as perversity the prohibition of conscience.

In his letter to Daniel Manin, which I published in 1856, Mazzini

described as a "quibble " the use of the word "unification" instead of

"unity." "Unification" is not a bad thing in itself, though very different

from unity. To put forth unification as a substitute for unity was

forsaking unity. It was a change of front, but not "quibbling." The

Government of Italy were advised to contrive local amelioration, as a

means of impeding, if not undermining, claims for national freedom. Mazzini condemned Manin for concurring in this. All English insurgent

parties have shown similar animosity against amelioration of evil, lest it

diverted attention from absolute redress. Yet it is a great responsibility

to continue the full evil in all its sharpness and obstructiveness, on the

grounds that its abatement is an impediment to larger relief. Every

argument for amelioration is a confession that those who object to

injustice are right. What is to prevent reformers continuing their demand

for all that is necessary, when some of the evil is admitted and abated? Paramount among agitators as I think Mazzini, it is a duty to admit that

he was not errorless. High example renders an error serious.

The press being free in England, there needed no conspiracy here. An

engraved card, still hanging

in a little frame in many a weaver's and miner's house in the North of

England, was issued at a shilling each on behalf of funds for European

freedom, signed by Mazzini for Italy, Kossuth for Hungary, and Worcell for

Poland. When editing the Reasoner I received one morning a letter from

Mazzini, dated 15, Radnor Street, King's Road, Chelsea, June 12, 1852. This was the only one of Mazzini's letters bearing an address and date I

ever saw, as I have said. It began:—

|

|

|

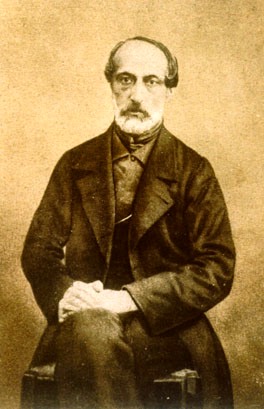

Giuseppe Mazzini

(1805-72) |

"MY DEAR SIR,—You have once, for the Taxes on Knowledge question,

collected a very large sum by dint of sixpences. Could you not do the

same, if your conscience approved the scheme, for the Shilling

Subscription [then proposed for European freedom]? I have never made any

appeal for material help to the English public, but once the scheme is

started, I cannot conceal that I feel a great interest in its success. A

supreme struggle will take place between Right and Might, and any

additional strength imparted to militant Democracy at this time is not to

be despised. Still, the moral motive is even more powerful with me. The

scheme is known in Italy, and will be known in Hungary, and it would be

extremely important for me to be able to tell my countrymen that it has

not proved a failure.

"Ever faithfully yours,

"JOSEPH MAZZINI."

I explained to the readers of the Reasoner the great service they might

render to European freedom at that time by a shilling subscription from

each. Very soon we received 4,000 shillings. Later (August 3, 1852)

Mazzini, writing from Chelsea, said:—

"MY DEAR SIR,—I have still to thank you for the noble appeal you have

inserted in the Reasoner in favour of the Shilling Subscription in aid of

European freedom. My friend Giovanni Peggotti, fearing that physical and

moral torture might weaken his determination and extort from him some

revelations, has hung himself in his dungeon at Milan, with his own

cravat. State trials are about being initiated by military commissions,

and General Benedek, the man who directed the wholesale Gallician

butcheries, is to preside over them. At Forli, under Popish rule, enforced

by Austrian bayonets, four working men have been shot as guilty of having

defended themselves against the aggression of some Government agents. The

town was fined in a heavy sum, because on that mournful day many of the

inhabitants left it, and the theatres were empty in the evening.

"Faithfully yours,

"JOSEPH MAZZINI."

People of England have mostly forgotten now

what Italians had to suffer when their necks were under the ferocious heel

of Austria.

In a short time I collected a further 5,000 shillings, making 9,000 in

all, and I had the pleasure of sending to Mazzini a cheque for £450. [32]

A shilling subscription had been previously proposed mainly at the

instigation of W. J. Linton, which bore the names of Joseph Cowen, George

Dawson, Dr. Frederic Lees, George Serle Phillips, C. D. Collet, T. S.

Duncombe, M.P., Viscount Goderich, M.P. (now Marquis of Ripon), S. M.

Hawks, Austin Holyoake, G. J. Holyoake, Thornton Hunt, Douglas Jerrold,

David Masson, Edward Miall, M.P., Professor Newman, James Stansfeld, M.P. Some of these names are interesting to recall now. But it was not until

Mazzini asked me to make an appeal in the Reasoner that response came. Its

success then was owing to the influence of Mazzini's great name. Workmen

in mill and mine gave because he wished it.

I published Weill's "Great War of the Peasants," the first and only

English translation, in aid of the war in Italy. The object was to create

confidence in the struggle of the Italian peasantry to free their country,

and to give reasons for subscriptions from English working men to aid

their Italian brethren. Madame Venturi made the translation, on Mazzini's

suggestion, for the Secular World, in which I Published it.

In 1855, wishing to publish certain papers of Mazzini's, I wrote asking

him to permit me to do so, when he replied in the most remarkable letter I

received from him:

"DEAR SIR,—You are welcome to any writing or fragment of mine which you

may wish to reprint in the Reasoner. Thought, according to me, is, as soon

as publicly uttered, the property of all, not an individual one. In this

special case, it is with true pleasure that I give the consentment you ask

for. The deep esteem I entertain for your personal character, for your

sincere love of truth, perseverance, and nobly tolerant habits, makes me

wish to do more; and time and events allowing, I shall.

"We pursue the same end—progressive improvement, association,

transformation of the corrupted medium in which we are now living,

overthrow of all idolatries, shams, lies, and conventionalities. We both

want man to be not the poor, passive, cowardly, phantasmagoric unreality

of the actual time, thinking in one way and acting in another; bending to

power which he hates and despises, carrying empty Popish, or thirty-nine

article formulas on his brow and none within; but a fragment of the living

truth, a real individual being linked to collective humanity, the bold

seeker of things to come; the gentle, mild, loving, yet firm,

uncompromising, inexorable apostle of all that

is just and heroic—the Priest, the Poet, and the Prophet. We widely

differ as to the how and why.

"I do dimly believe that all we are now struggling, hoping, discussing, and

fighting for, is a

religious question. We want a new intellect of life; we long to tear off

one more veil from the ideal, and to realise as much as we can of it; we

thirst after a deeper knowledge of what we are and of the why we are. We

want a new heaven and a new earth. We may not all be now conscious of

this, but the whole history of mankind bears witness to the inseparable

union of these terms. The clouds which are now floating between our heads

and God's sky will soon vanish and a bright sun shine on high. We may have

to pull down the despot, the arbitrary dispenser of grace and damnation,

but it will only be to make room for the Father and Educator.

"Ever faithfully yours,

"JOSEPH MAZZINI."

Another incident has instruction in it, still necessary and worth

remembering in the political world. In 1872 I found in the Boston Globe,

then edited by Edin Ballou, a circumstantial story by the Constitutional

of that day, setting forth that Sir James Hudson, our Minister at Turin,

begged Cavour to accord an interview to an English gentleman. When Cavour

received him, he was surprised by the boldness, lucidity, depth, and

perspicacity of his

English visitor, and told him that if he (Cavour) had a countryman of like

quality, he would resign the Presidency of the Council in favour of him

whereupon the "Englishman" handed Cavour his card bearing the name of

Joseph Mazzini, much to his astonishment.

There are seven things fatal to the truth of this story

received and circulated throughout Europe without question:—

1. Sir James Hudson could never have introduced to the Italian Minister a

person as an Englishman, whom Sir James knew to be an Italian.

2. Nor was Mazzini a man who would be a party to such an artifice.

3. Cavour would have known Mazzini the moment he saw him.

4. Mazzini's Italian was such as only an Italian could speak, and Cavour

would know it.

5. Mazzini's Republican and Propagandist plans were as well known to

Cavour as Cobden's were to Peel; and Mazzini's strategy of conspiracy was

so repugnant to Cavour, that he must have considered his visitor a wild

idealist, and must have become mad himself to be willing to resign his

position in Mazzini's favour.

6. Cavour could not have procured his visitor's appointment in his place

if he had resigned.

7. Mazzini could not have offered Cavour his card, for the reason that he

never carried one. As

in Turin he would be in hourly danger of arrest, he was not likely to

carry about with him an engraved identification of himself.

Nevertheless, the Pall Mall Gazette of that day (in whose hands it was

then I forget) published this crass fiction without questioning it.

The reader will rightly think that these are the incredible fictions of a

bygone time, but he will conclude wrongly if he thinks they have ceased.

Lately, not a nameless but a known and responsible person, one Sir Edward

Hertslet, K.C.B., a Foreign Office official, published a volume in which

he related that in 1848 (the 10th of April year, when no political

historian was sane) a stranger called at the Foreign Office to inquire for

letters for him from abroad. A colleague of Sir Edward's suggested that he

should inquire at the Home Office. The strange gentleman replied

indignantly, "I will not go to the Home Office. My name is Mazzini." This

answer Sir Edward put in quotation marks, as though it was really said. Sir Edward has been in the Diplomatic service. He has been a Foreign

Office librarian, and is a K.C.B., yet for more than fifty years he has

kept this astounding story by him, reserved it, cherished it, never

suspected it, nor inquired into its truth.

Mazzini was not a man to give his name to a youth (as Sir Edward was then)

at the Foreign Office. He never went there. It is doubtful

whether any letter ever came to England bearing his name. He was known

among his friends as Mr. Flower or Mr. Silva. When the late William Rathbone Greg wished to see him, he neither knew his name nor where he

resided, and his son Percy—who was then writing for a journal of which I

was editor—was asked to obtain from me an introduction, and it was only

to oblige me that Mazzini consented

to see Mr. W. R. Greg. Sir James Graham never opened any letter addressed

to Mazzini, for none ever came. He opened letters of other persons, as

every Foreign Secretary before him and since has done, in which might be

enclosed a communication for Mazzini. Was it conceivable that the Foreign

Office, then known to secretly open Mazzini's letters, would be chosen by

the Italian exile as a receiving house for his letters, and have

communications sent to its care, and addressed in his name? Was it

conceivable that Mazzini would go there and announce himself when the

Foreign Office was acting as a spy upon his proceedings in the interest of

foreign Governments? This authenticated Foreign Office story would be too

extravagant for a "penny dreadful," yet not too extravagant, in Sir Edward Hertslet's mind, to be believable by the official world now, and was sent

or found its way to Foreign Embassies and Legations for their delectation

and information. Yet Sir Edward was not known as a writer of romance, or

novels, or theological works, nor a poet, or other dealer in

imaginary matters. His book was widely reviewed in England, and nowhere

questioned save in the Sun during my term of editorship in 1902.

Mazzini preached the doctrine of Association in England when it had no

other teacher. Much more may be said of him—but Sir James Stansfeld is

dead, and Madame Venturi and Peter Alfred Taylor. Only Jessie White Mario

and Professor Masson remain who knew Mazzini well. But this chapter may

give the public a better conception than has prevailed of Mazzini's career

in England.

CHAPTER XVIII.

MAZZINI THE CONSPIRATOR

THERE have been many conspirators, but Mazzini appears to have been the

greatest of them all. In one sense, every leader of a forlorn hope is a

conspirator. Prevision, calculation of resources, plans of

campaign—mostly of an underground kind—are necessary to conspiracy. The

struggles of Garrison and Wendell Phillips for the rescue and sustentation

of fugitive slaves are well-known instances of underground conspiracy. There the violence of the slave-owner made conspiracy inevitable. In

despotic countries, without a free platform and a free press, the choice

lies between secret conspiracy and slavery. When Mazzini began to seek the

deliverance of Italy he had to confront 600,000 Austrian bayonets. How

else could he do it than by conspiracy?

Those are very much mistaken who think that the

occupation of promoting or taking part in a forlorn hope is a pastime to

which persons disinclined to business or honest industry, betake

themselves. The spy, for instance, who is a well

known instrument in war, takes the heroism out of it. The sinister

activity of the spy turns the soldier

into a sneak. Honourable men do, indeed, persuade themselves that if by

deceit they can obtain knowledge of facts which may save the lives of many

on

their own side, it is right. At the same time they also betray to death

many on the other side, including some who have trusted the spy in his

disguise. But whatever success may attend the deceit of the spy, he can

never divest himself of the character of being a fraud; and a fraud in

war is

only a little less base than a fraud in business. But it is the perils of

even the patriotic spy, which are so

often under-estimated. If discovered by the enemy, he is sure to be shot;

and he runs the risk of being killed on suspicion by friends on his own

side—too indignant to inquire into the nature of the suspicions

they entertain. The spy dare not communicate the business he is upon to

his friends. Somehow it would get out; then the spy would surely walk the

plank, or hang from the gallows as André did. The spy's own friends

being ignorant of the secret duty he has undertaken, observe him making

the acquaintance of the enemy—hear of him being seen in communication

with them—and he becomes distrusted and disowned by those whom he perils

his life to serve. Mazzini detested the Cabinets, or the Generals, who

employed spies. He made war by secrecy—open war being impossible to

him—but never by treachery. Some who had suffered and

were incensed by personal outrage or maddening oppression, would act as

spies in revenge. Because these were done on the side of Italian

independence Mazzini was accused of inspiring them and employing

them.

|

|

|

Joseph Mazzini |

Mazzini had another difficulty. Like Cromwell, he sought his combatants

among men of faith. Mazzini was, as has been said, a Theist, like Thomas

Paine, or Theodore Parker, or Francis William Newman, he was that and

nothing more; and, as with them, his belief was passionate. He did not

believe that political enthusiasm could be created or sustained without

belief in God. He seemed unable to conceive that a sense of duty could

exist separately from that belief. Hence his motto always was "God and

the People," which limited his adherents largely to Theists; and implied a

propaganda to convert persons to a belief in Deity, before they could, in

his opinion, be counted upon to fight for Italian independence. Yet there

were contradictions; but contradictions seldom disturb passionate

convictions, and Mazzini himself could not deny that he had often been

faithfully served by men who were not at all sure that God would fight on

their side, if disaster overtook them. One night at a crowded Fulham party

Mazzini was contending, as was his wont, that an Atheist could not have a

sense of duty. Garibaldi, who was present, at once asked, "What

do you say to me?

I am an Atheist. Do I lack the sense of duty?"

"Ah," said Mazzini, playfully, "you imbibed duty with your mother's milk"—which was not an answer, but a good-natured evasion. Garibaldi was not a

philosophical Atheist, but he was a fierce sentimental one, from

resentment at the cruelties and tyrannies of priests who professed to

represent God. To disbelieve unwillingly from lack of evidence, and to

disbelieve from natural indignation is a very different thing.

All the many years Mazzini was in London, Madame Venturi was constantly in

communication with him, and was present at more conversations than any one

else. Had she possessed the genius of Boswell, and put down day by day

criticisms she heard expressed, the narratives of his extraordinary

adventures, and such as came to her knowledge from correspondence, now no

longer recoverable, we might have had as wonderful a volume of political

and ethical judgment as was Boswell's "Johnson." Sometimes I expressed a

hope that she was doing this. Nevertheless, we are indebted to her for the

best biography of him that appeared in her time. I add a few sayings of

his which show the quality of his table talk:—

"Falsehood is the art of cowards. Credulity without examination is the

practice of idiots."

"Any order of things established through violence, even though in itself

superior to the old, is still a tyranny."

"Blind distrust, like blind confidence, is death to all great

enterprises."

"In morals, thought and action should be in. separable. Thought

without action is selfishness

action without thought is rashness."

"The curse of Cain is upon him who does not regard himself as the guardian

of his brother."

"Education is the bread of the soul."

"Art does not imitate, it interprets."

Only those who were in the agitation for Italian freedom can understand

the exhausting amount of labour performed by those who were adherents or

sympathisers. How much greater was the labour of the commander of the

movement, who had to create the departments he administered, to provide the funds for them, to win and inspire its adherents, and correspond

incessantly with agents scattered over Europe and America, and to

vindicate himself against false accusations rained upon him by a hostile,

ubiquitous European press.

|

|

|

Felice Orsini

(1819-58) |

Orsini was a man of invincible courage, and could be trusted to execute

any commission given him. No danger deterred him, but in enterprises

requiring

prevision of contingencies, he was inadequate. Mazzini thought so; and Orsini secretly contrived to plot against the French usurper, to extort

from Mazzini the confession that he (Orsini) could carry out an in

dependent enterprise. All the same, the adversaries

of Italian freedom made Mazzini responsible for it.

A writer in the press, who did not give his name (and when a writer does

not do that, he can say anything), published, in editorial type, this

passage: "By the way, I remember that Orsini, the day before he left

England to make his attempt upon the life of Napoleon Ill., had a solemn

discussion with Joseph Cowen and Mazzini, as to the justice of

tyrannicide." Mazzini being then dead, I sent the paragraph to Mr. Cowen

and asked him if there was any truth in it, who replied:—

"BLAYDON-ON-TYNE,

March 2, 1891.

"MY DEAR HOLYOAKE,— I have no idea where the writer of the enclosed

paragraph gets his information. I cannot speak as to Orsini having a

conversation with Mazzini, but I should think it is in the highest sense

improbable, because long before Orsini went to France, Mazzini and he had

not been in friendly intercourse. There was a difference between them

which kept them apart. I had repeated conversations with Orsini about

tyrannicide—a matter in which he seemed interested—but I did not see him

for some weeks before he went to France. "Yours truly,

"JOSEPH COWEN."

Mazzini always repudiated the dagger as a Political weapon. It answered

the purpose of his adversaries in his day and since, to accuse him of

advocating it. He pointed out that calumny was

a dagger used to assassinate character, but to that form of assassination

few politicians made objection. Sometimes partisans of Mazzini would

supply a colourable presumption of the truth of this accusation.

A circumstantial story appeared in the "Life of Charles Bradlaugh " (vol.

i. p. 69), signed W. E, Adams, as follows:—

"The year 1858 was the year of Felice Orsini's attempt on the life of

Louis Napoleon. I was at that time, and had been for years previously, a

member of the Republican Association, which was formed to propagate the

principles of Mazzini. When the press, from one end of the country to the

other, joined in a chorus of condemnation of Orsini, I put down on paper

some of the arguments and considerations which I thought told on Orsini's

side. The essay thus was read at a meeting of one of our branches; the

members assembled earnestly urged me to get the piece printed. It occurred

to me also that the publication might be of service, if only to show that

there were two sides to the question of 'Tyrannicide.' So I went to Mr. G.

J. Holyoake, then carrying on business as a publisher of advanced

literature. Mr. Holyoake not being on the premises, his brother, Austin,

asked me to leave my manuscript and call again. When I called again Mr.

Holyoake returned me the paper, giving, among other reasons for declining

to publish it, that he was already in negotiation with

Mazzini for a pamphlet on the same subject. 'Very well,' said I, 'all I

want is that something should be said on Orsini's side. If Mazzini does

this, I shall be quite content to throw my production into the fire.' "

It is true that the pamphlet was brought to me by Mr. Adams, entitled, "Tyrannicide: A Justification." What really took place on my part, as

I distinctly remember, was this. I said: "I was unwilling to publish a

pamphlet of that nature which did not bear the name of the writer, which

the MS. did not. The author answered that "a name added no force to an

argument; besides, his name was unimportant, if put on the title-page,"

which was reasonably and modestly said. My reply was, "That in an affair

of murder, 'justification' was a recommendation, and that any one acting

on his perilous suggestion ought to know who was his authority." Nothing

more was said by me. The writer made no offer to add his name to his MS.,

nor to meet my objection by a less assertive title. As any prosecution for

publishing it would be against me, and not against him, I thought I had a

right to an opinion as to the title and authorship of the work I might

have to defend. It was afterwards issued by Mr. Truelove, a bookseller of

courage and public spirit, but who suggested the very changes I had

indicated to the author; and by Mr. Truelove's desire the author not only

gave his name, but

changed the title into "Tyrannicide: Is it Justifiable?" which was quite another matter. It asked the question; it no

longer decided it.

As to Mazzini, it is impossible I could have said what is imputed to me. I

was not "in negotiation with Mazzini" to write anything upon the Orsini affair. I knew he would not do so. Orsini, as

I have said, concealed his

plot from Mazzini, who never incited it, never approved it, never

justified it—he deplored it. Only enemies of Mazzini sought to connect

him with it. If I left this story uncontradicted, it might creep into

history that, in spite of the disclaimers of Mazzini's friends, he

actually "entered into negotiation" to write in defence of Orsini's

attempt, which must imply concurrence with the deplorable method Orsini

unhappily took; and, moreover, that a publisher, regarded as being in

Mazzini's confidence, had, in an open, unqualified way, told a writer on

assassination of it. The publisher was speedily arrested on the issue of

the pamphlet, as I should have been, but that would not have deterred me

from publishing it in a reasonable and responsible form.

Soon after I printed and published a worse pamphlet by Felix Pyat, which

was signed by "A Revolutionary Committee." The Pyat pamphlet was under

prosecution at the time I voluntarily published it. As what I did I did

openly—I wrote to the Government apprising them of what I was doing.

Besides, I commenced to issue serial "Tyrannicide Literature," commencing

with pamphlets

written by Royalist advocates of assassination. Because I did not publish

the Adams Tyrannicide pamphlet right off without inquiry or suggestion, I

was freely charged with refusing to do it from fear. No one seems to have

been informed of the reasons I gave for declining. No one inquired into

the facts. Adversaries of those days did not take

the trouble. But, as I had to take the consequences of what I did, I

thought I had a right to take my own mode of incurring them.

On the last night of Orsini's life, Mazzini and a small group of the

friends both of Orsini and himself, of which I was one, kept vigil until

the morning, at which hour the axe in La Roquette would fall.

The favourite charge of the press against the great conspirator was that

he advised others to incur danger, and kept out of it himself. This was

entirely untrue—but it did not prevent it being said. The principle these

critics go upon is, that whoever is capable of advising and directing

others, should do all he can to get himself shot—a doctrine which would

rid the army of all its generals, and

the offices of all newspapers of their editors. Upon Mazzini's life the

success of twenty small cohorts of patriots depended, ready to give their

lives for

Italy. Mazzini was not only the commander of the army of Liberation, but,

as has been indicated, the provider of its reserves, its commissariat and

recruits. His life was also of priceless value to

other struggling peoples. He was the one statesman in Europe who had a

European mind—who knew the peoples of the Continent, whose knowledge

was intimate, and whose word could be trusted. So far from avoiding

danger, he was never out of it. With a price set upon his head in three

countries, hunted by seven Governments, with spies always following him

and by assassins lying in ambush, his life for forty years passed in more

peril than any other public man of his time. Yet it was fashionable to

charge him with want of courage whose whole "life," to use his own

phrase, "was a battle and a march."

Could there be a doubt of the intrepidity of a man who, with the slender

forces of insurgent patriots, confronted Austria with its 600,000

bayonets.

No sooner was Garibaldi in Rome than Mazzini was there in the streets

inspiring its defenders. What dangers he passed through to reach Rome,

knowing well that his arrest meant death!

Rome was not a safe place for Mazzini, neither was London. His life was

never safe. I have been asked by his host to walk home with him at night

from a London suburban villa where he dined, because a Royalist assassin

was known to be in London waiting to kill him.

Mazzini died at Pisa, March 10, 1872, from chill by walking over the Alps

in inclement weather, intending to visit his English friends once more.

A few of his English colleagues protested against his

embalmment. I was not one. Gorini, the greatest of his profession,

undertook to transform the body into marble, and for him Mazzini had

friendship. Dr. Bertani, Mazzini's favourite physician, approved

embalming. It could not be done by more reverent hands. How

could England—who disembowelled Nelson and sent his body home in a cask of

rum; who embalmed Jeremy Bentham, and took out O'Connell's heart, sent it

to one city, and his mutilated remains to another—reproach Italy for

observing the national rites of their illustrious dead?

The personal character of Mazzini never needed defence. In private life

and state affairs, honour was to him an instinct. He saw the path of right

with clear eyes. No advantage induced him to deviate from it. No danger

prevented his walking in it.

Carlyle, whom few satisfied, said he "found in him a man of clear

intelligence and noble virtues. True as steel, the word, the thought of

him pure and limpid as water."

It may be by experience that a nation is governed, but it is by rightness

alone that it is kept noble. It was to promote this that Mazzini walked

for forty years on the dreary highway between exile and the scaffold. It

was from belief in his heroic and unfaltering integrity that men went out

at his word, to encounter the dungeon, torture, and death, and that

families led all their days alarmed

lives, and gave up husbands and sons to enterprises in which they could

only triumph by dying.

No one save Byron has depicted the self-denial incidental to Mazzini's

career, which involved the abnegation of all that makes life worth living

to other men.

"Such ties are not

For those who are called to the high destinies

Which purify corrupted commonwealths.

We must forget all feeling save the One

We must resign all passions, save our purpose.

We must behold no object, save our country.

And only look on death as

beautiful

So that the sacrifice ascend to heaven,

And draw down freedom on her evermore." [33] |

Mazzini left a name which has become one of the landmarks, or rather

mindmarks, of public thought, and, though a bygone name, there is

instruction and inspiration in it yet.

CHAPTER XIX.

GARIBALDI—THE SOLDIER OF LIBERTY

|

|

|

Giuseppe Garibaldi

(1807-82) |

DINING one day (June 29, 1896) at Mr. Herbert Spencer's, thirty years

after Garibaldi left England, Professor Masson, who was a guest of Mr.

Spencer, told me that Garibaldi said to Sir James Stansfeld that "the

person whom he was most interested in seeing in England was myself." This

Garibaldi said at a reception given by Mr. Stansfeld to meet the

General—as we had then begun to call him. I was one of the party; but Mr. Stansfeld did not mention the remark to me, and I never heard of it until

Professor Masson told me. Of course I should have been gratified to know

it. We had met before, but it was years earlier, and Garibaldi had

forgotten it. The vicissitudes and battles of his tumultuous career may

well have effaced the circumstance from his mind.

The first occasion of my meeting Garibaldi was at an evening party at the

Swan Brewery, Fulham, when I was asked to accompany him to Regent Street,

where he was then residing. My name would be given to him at the

time, which he might not distinctly hear, as is often the case when an

unfamiliar name is heard by a foreign ear, as occurs when a foreign name

is mentioned to an English ear. On our way he asked me "how it was

that the English people had accorded such enthusiastic receptions to

Kossuth, and yet they appeared to have done nothing on behalf of Hungary?"

I explained to him that "our Foreign Office was controlled by a few

aristocratic families who had little sympathy with and less respect for

the voteless voices of the splendid crowds who greeted Kossuth with

generous acclaim. That was why large and enthusiastic concourses of

people in the streets produced so little effect upon the English

Government." The great Nizzard insurgent had been mystified by the

impotence of popular enthusiasm. In such plain, brief and abrupt

sentences as I thought would be intelligible, I explained that "he must

distinguish between popular sympathy and popular power. He might

find himself the subject of the generous enthusiasm of the streets, but he

must take it as the voice of the people, not the voice of the Government."

Kossuth, who had a better knowledge of English literature and the English

press, never made the distinction, which led him into mistakes and caused

him needlessly to suffer disappointments. To this day the House of

Lords is an alien power in England.

It was at the party which we left that night that I was first

struck with the natural intrepidity of Garibaldi. His square

shoulders and tapering body I had somehow come to associate with military

impassableness, and the easy, self-possessed way in which he moved through

the crowd in the room confirmed my impression. I was told afterwards

by one of his fellow combatants that unconscious courage was his

characteristic on the field. Calmness and imperturbable modesty were

attributes of his mind, as seen in his heroic acts, deemed utterly

impossible save in romance. He had received the triumphal

acclamation of people he freed, whose forefathers had only dreamed of

liberation.

Since the time of that casual acquaintanceship, Garibaldi had

heard of me from Mazzini, from Mr. Cowen, and as acting secretary of the

Committee who sent out the British Legion to him. We had collected a

considerable sum of money for him, which was lying in unfriendly hands,

but which his treasurer had been unable to obtain. I had sent him

other help, when help was sorely needed by his troops. Besides, I

had defended him and his cause under the names of "Landor Praed," "Disque,"

and my own name, in the press. Garibaldi sent me one of the first

photographs taken of himself after his victorious entry into Naples, on

which he had written the words, "Garibaldi, to his friend, J. G. Holyoke."

He had got name and initials transposed in those eventful days.

After the affair of Micheldever, [34] he charged his

son Menotti to show me personal and public attention on his visit to the

House of Commons. To the end of his life he saw every visitor who

came to him with a note from me.

When Menotti Garibaldi died, the family wished that the flag

which the "Thousand" carried when they made their celebrated invasion of

the Neapolitan kingdom, should be borne at the funeral. They

therefore telegraphed to the mayor of Marsala, who was supposed to be the

guardian of the relic. The mayor replied that he had not got it, but

that it was at Palermo; so the mayor of Palermo was telegraphed to.

He also replied that he had not got it, and said it was in the possession

of Signor Antonio Pellegrini, but that its authenticity was very doubtful.

General Canzio, one of the survivors of the expedition, says that the flag

possessed by Signor Pellegrini is nothing like the real one, which was

merely a tricolor of three pieces of cotton nailed to a staff. At

the battle of Calatafimi the standard-bearer was shot and the flag lost.

It was said to have been captured by a Neapolitan sub-lieutenant, but all

traces of it have now disappeared. The wonder is not that the flag

has disappeared, but that so many official persons should declare it to

exist elsewhere, of which they had no knowledge. The flag of the

Washington would have been lost had it not been taken possession of by

De Rohan. The last flag carried by the Mazzinians, which was shot

through, would have been lost also had not Mr. J. D. Hodge sought for it

before it was too late. Both flags are in my possession.

Walter Savage Landor sent me (August 20, 1 860) these fine

lines on Garibaldi's conquest of the Sicilies:—

|

"Again her brow Sicaria rears

Above the tombs—two thousand years,

Have smitten sore her beauteous breast,

And war forbidden her to rest.

Yet war at last becomes her friend,

And

shouts aloud

Thy

grief shall end.

Sicaria! hear me! rise again!

A homeless hero breaks thy chain." |

How often did I hear it said, in his great days of action,

that had Garibaldi known the perils he encountered in his enterprises, he

would never have attempted them. No one seemed able to account for

his success, save by saying he was "an inspired madman." His heroism

was not born of insanity, but knowledge. His wonderful march of

conquest through Italy was made possible by Mazzini. In every town

there was a small band, mostly of young heroic men, who were inspired by

Mazzini's teaching, who, like the brothers Bandiera, led forlorn hopes, or

who were ready to act when occasion arose. I well remember when

seeking assistance for Mazzini, how friends declined to contribute lest

they became accessory to the fruitless sacrifice of brave men. There

was no other way by which Italy could be freed, than by incurring this

risk. Mazzini knew it, and the men knew it, as Mazzini did not

conceal it from those he inspired.

The following letter to me by one of the combatants was

published at the time in the Daily Telegraph. It is a

forgotten vignette of the war, drawn by a soldier on the battlefield who

had been wounded five times before, fighting under Garibaldi:—

"DEAR SIR,—Just time to say that we are in full possession,

after streams of blood have flowed. Fights 'twixt brothers are

deadly.

"We want money; we want, as I told you, a British steamer

chartered, with revolving rifles and pistols of Colt's (17, Pall Mall),

also some cannon rayé; but for the

sake of humanity and liberty do hurry up the subscriptions. The

sooner we are strong the less the chance of more fighting. We muster

now some 30,000 all told, though not all armed. We want arms and

ammunition, and caps—Minié rifles.

Or the rifle corps pattern the General would as soon have. He is

well and radiant with joy and hope, though sighing over the necessity to

shed blood. Oh! will the world never learn to value the really great

men of the earth until the grave has closed over them? Garibaldi has

written only one or two of all the things published over his name.

The rest are the inventions of enemies or over-zealous friends.

"Messina must capitulate. If the King grant a

constitution, all will be lost. The Bourbons must be driven from

Italy, for it will never be quiet without. Warn the papers against

trusting the so-called letters, etc., from Garibaldi. He writes

little or none, and dislikes to be made prominent.

"Do try and urge on the subscriptions. The English

admiral here has behaved bravely, and Lord John Russell's praises are in

every one's mouth; but he must not falter or hesitate,

"The Royal Palace was burned down, and the fighting was

desperate indeed.

"Of all the defeats imputed to the 'insurgents, ' not one has

really taken place. The General was at times obliged to sacrifice

some lives for strategical purposes.

"Now, pray use your influence for England not to allow Naples

to patch up a peace, for I tell you it is useless. Garibaldi and his

friends will never consent to anything short of 'Italy for the Italians.'

"You may communicate this as 'official' if you wish to the

Times or News, reserving my name Yours truly, in great haste,

"———

"G. J. Holyoake, Esq.

"P.S.—I need hardly say this will have to take its chance of

getting to you. I trust it to a captain whom I have given the money

to pay the postage in Genoa, where he is going. Will you let me hear

from you?"

He did hear from me. Whether it is good to die "in

vain," as George Eliot held, I do not stay to determine. Certainly,

to die when you know it to be your duty, whether "in vain" or not, implies

a high order of nature. Sir Alfred Lyall has sung the praise of

those English soldiers captured in India, who, when offered their lives if

they would merely pronounce the name of the Prophet, refused. It was

only a word they had to patter, and Sir Alfred exclaims, "God Almighty,

what could it matter?" But the brave Englishmen died rather than be

counted on the side of a faith they did not hold. Dying for honour

is not dying in vain, and I thought the Italians entitled to help in their

holy war for manhood and independence.

When Garibaldi was at Brooke House, Isle of Wight, I was

deputed by the Society of the Friends of Italy to accompany Mazzini to

meet Garibaldi. Herzen, the Russian, who kept the "Kolokol" ringing

in the dominions of the Czar, met us at Southampton. The meeting

with Garibaldi took place at the residence of Madame Nathan. The two

heroes had not met in London when the General was a guest of the Duke of

Sutherland. As soon as Garibaldi saw Mazzini, he greeted him in the

old patois of the lagoons of Genoa. It affected Mazzini, to whom it

brought back scenes of their early career, when the inspiration of Italian

freedom first began.

Mrs. Nathan, wife of the Italian banker of Cornhill, was an

intrepid lady, true to the freedom of her country, who had assisted

Garibaldi and Mazzini in many a perilous enterprise. After the

interview at her house, she had occasion to consult Garibaldi on matters

of moment. Misled or deterred by aspersion, which every lady had to

suffer, suspected of patriotic complicity, Mrs. Nathan was not invited to

Brooke House. Under these circumstances she could not go alone to

see the General, and she asked me to take her. Offering her my arm,

we walked through the courtyard and along the corridors of the house to

Garibaldi's rooms. Going and returning from her interview, I was

much struck by the queenly grace and self-possession of Mrs. Nathan's

manner. There was neither disquietude nor consciousness in her

demeanour of the disrespect of not being invited to Brooke House, though

her residence was known.

|

|

|

Joseph Cowen

(1831-1900) |

On the night of Garibaldi's arrival at Brooke House, Mr.

Seely, the honoured host of the General, invited me to join the dinner

party, where I heard things said on some matters, which the speakers could

not possibly know to be true. Garibaldi showed no traces of

excitement, which had dazed so many at Southampton that afternoon.

The vessel which brought him there was immediately boarded by a tumultuous

crowd of visitors. All the reporters of the London and provincial

press were waiting for the vessel to be sighted, and they were foremost in

the throng on the ship. Before them all was Mrs. Colonel Chambers,

with her beseeching eyes, large, luminous and expressive, and difficult to

resist. Garibaldi gave instant audience to Joseph Cowen, whose voice

alone, or chiefly, influenced him. Years before, when Garibaldi was

unknown, friendless, and penniless, he turned his bark up the Tyne to

visit Mr. Cowen, the only Englishman from whom he would ask help.

Garibaldi's first day at Southampton was more boisterous than a battle.

Everybody wanted him to go everywhere. Houses where his name had

never been heard were now open to him. Mr. Seely was known to be his

friend. The Isle of Wight was near. Brooke House lay out of

the way of the "madding crowd," and there his friends would have time to

arrange things for him. The end of his visit to England was sudden,

unforeseen, inexplicable both to friend and foe, at the time and for long

after.

He had accepted engagements to appear in various towns in

England, where people would as wildly greet him as the people of London

had done. When it was announced that he had left England, it was

believed that the Emperor of the French had incited the Government to

prevail upon Garibaldi to leave the country. Others conjectured that

Mr. Gladstone had whispered something to him which had caused the Italian

hero to depart. I asked about it from one who knew everything that

took place—Sir James Stansfeld—and from him I learned that no foreign

suggestion had been made, that nothing whatever had been said to

Garibaldi. His leaving was entirely his own act. He had reason

to believe that Louis Napoleon was capable of anything; but with all his

heroism, Garibaldi was imaginative and proud. He fancied his

presence in England was an embarrassment to the Government. He being

the guest of the nation, they would never own to it or say it. But

his departure might be a relief to them, nevertheless. And therefore

he went. His sensitiveness of honour shrank from his being a

constructive inconvenience to a nation to whom he owed so much and for

whom he cared so much. It was an instance of the disappointment

imagination may cause in politics. [35]

But Garibaldi was a poet as well as a soldier. Like the

author of the "Marseillaise," Korner and Petöfe,

he could write inspiring verse, as witness his "Political Poem" in reply

to one Victor Hugo wrote upon him, which Sir Edwin Arnold, the "Oxford

Graduate" of that day, translated in 1868. Those do not understand

Garibaldi who fail to recognise that he had poetic as well as martial

fire. [36]

CHAPTER XX.

THE STORY OF THE BRITISH LEGION—NEVER BEFORE TOLD

GENERAL DE LACY EVANS

is no longer with us, or he might give us an instructive account of the

uncertainty and difficulty of discipline in a patriotic legion which

volunteers its services without intelligently intending obedience.

When I became Acting Secretary for sending out the British Legion to

Garibaldi, I found no one with any relevant experience who knew what to

expect or what to advise. Those likely to be in command were ready

to exercise authority, but those who were to serve under them expected to

do it more or less in their own way. The greatest merit in a

volunteer legion is that they agree in the object of the war they engage

in. They do not blindly adopt the vocation of murder—for that is

what military service means. It means the undertaking to kill at the

direction of others—without knowledge or conviction as to the right and

justice of the conflict they take part in.

General De Lacy Evans being a military man of repute, and

marching with his Spanish Legion had disciplinary influence over them.

Two of my colleagues in other enterprises of danger were among the Spanish

volunteers, but they were not at hand—one being in America and the other

in New Zealand —otherwise I might have had the benefit of their

experience.

The project of sending out to Garibaldi a British Legion came

in the air. It was probably a suggestion of De Rohan's, who had

gathered in Italy that British volunteers would influence Italian opinion;

be an encouragement in the field; and, if sent out in time, they might be

of military service. Be this as it may, the Garibaldi Committee found

themselves, without premeditation, engaged in enlisting men, at least by

proxy. It was a new business, in which none of us were experts. We knew

that men of generous motive and enterprise would come forward. At the same

time, we were opening a door to many of whom we could not know enough to

refuse, or to trust. However, the army of every country is largely

recruited from the class of dubious persons, over whom officers have the

power to compel order—which we had not.

As I was the Acting Secretary, my publishing house, 147, Fleet Street, was

crowded with inquirers when the project of the Legion became known. Many gave their names there. For convenience of enrolment, a house was taken at No. 8, Salisbury

Street, Strand, where the

volunteers, honest and otherwise, soon appeared—the otherwise being more

obtrusive and seemingly more zealous. Among them appeared a young man,

wearing the uniform

of a Garibaldian soldier, of specious manners, and who called himself "Captain Styles"—a harmless rustic name, but he was not at all rustic in

mind. Being early in the

field, volunteers who came later took it for

granted he had an official position. It was assumed that he had been in

Italy and in some army, which was more than we knew. His influence grew by

not being

questioned. Without our knowledge and without any authority, he invented

and secretly sold commissions, retaining the proceeds for his own use. To

avoid obtruding

our military objects on public attention, I drew up a notice, after the

manner of Dr. Lunn's tourist agency, as follows:—

|

XCURSION to SICILY and NAPLES.—All persons (particularly Members of

Volunteer Rifle Corps) desirous of visiting Southern Italy, and of AIDING

by their presence and

influence the CAUSE of GARIBALDI and ITALY, may learn how to proceed by

applying to the Garibaldi Committee, at the offices at No. 8, Salisbury

Street, Strand, London. |

The Committee caused, on my suggestion, applicants to

receive notice of two things:—

(1) That each man should remember that he goes

out to represent the sacred cause of Liberty, and that the cause will be

judged by his conduct. His behaviour will be as important as his bravery.

(2) Those in command will respect the high feeling by which the humblest

man is animated—but no man must make his equal patriotism a pretext for

refusing implicit

obedience to orders, upon which his safety and usefulness depend. There no

doubt will be precariousness and privation for a time, which every man

must be prepared to

share and bear.

Further, I wrote an address to the

"Excursionists" and had a copy placed in the hands of every one of them.

It was to the following effect:—

Before leaving Faro, Garibaldi issued an address to his

army, in which he said:—

"Among the qualities which ought to predominate among the officers

of an Italian army,

besides bravery, is the amiability which secures the affection of

soldiers—discipline, subordination, and firmness necessary in long

campaigns. Severe discipline may be

obtained by harshness, but it is better obtained by kindness. This secret

the numerous spies of the enemy will not discover. It brought us from

Parco to Gibil-Rosa, and

thence to Palermo. The honourable behaviour of our soldiery towards the

inhabitants did the rest. Of bravery, I am sure!" exclaims the General. "What I want is the

discipline of ancient Rome, invariable harmony one with another—the due respect for property, and above all for that of the

poor, who suffer so much to gain the scanty bread of their families. By

these means we shall lessen

the sacrifice of blood and win the lasting independence of Italy."

To this address was added the following paragraph:—

"In these words the volunteer will learn the quality of companionship he

will meet with in the field, and the spirit which prevails among the

soldiers of Italian independence."

When we had collected the Legion, the thing was to get it out of the

country—international law not being on the side of our proceedings. As

many as a thousand names [37]

were entered on the roll of British volunteers for Italy. The Great

Eastern Railway was very animated.

When they were about to set out at a late hour for

Harwich, a "Private and Confidential" note was sent to each saying:—

"As the arrangements for the departure of the detachment of Excursionists

are now complete, I have to request your attendance at Caldwell's Assembly

Rooms, Dean Street,

Oxford Street, at three o'clock precisely, on Wednesday, the 26th instant

(September, 1860 ), when you will receive information as to the time and

place of departure which

will be speedy.

"(Signed) E. STYLES, Major."

By this times the "Captain" had blossomed into

a "Major." Owing to urgency the Committee had to acquiesce in many

things. Garibaldi being in the field, and often no one knew where, it was

futile to ask

questions and impossible to get them answered.

The Government no doubt knew all about the expedition. Captain De Rohan,

or, as he styled himself, "Admiral De Rohan," was in command of the "Excursionists." He

marched up and down the platform, wearing a ponderous admiral's sword,

which was entirely indiscreet, but he was proud of the parade. By this

time he had assumed the

title

of "Rear" Admiral. De Rohan was not his name, but he was, it was said,

paternally related, in an unrecognised way, to Admiral Dalgren, of

American fame. Of De

Rohan it ought to be said, that though he had the American tendency to

self-inflation, he was a sincere friend of Italy. Honest, disinterested,

generous towards

others—and the devoted and trusted agent of Garibaldi, ready to go to the

ends of the earth in his service. When the English Committee finally

closed, and they had a

balance of £1,000 left in their hands, they were so sensible of the

services and integrity of De Rohan that they gave it to him, and on my

introduction he

deposited it in the Westminster Bank. He was one of those men for whom

some permanent provision ought to be made, as he took more delight in

serving others than

serving himself. In after years, vicissitude came to him, in which I and

members of the Garibaldi Committee befriended him.

As our Legion was going out to make war on a power in

friendly relation to Great Britain, Lord John Russell was in a position to

stop it. The vessel (the Melazzo) lay two

days in the Harwich waters before sailing. There were not wanting persons

who attempted to call Lord John's attention to what was going on, but

happily without recognition