|

[Previous

page]

CHAPTER LXX.

Mr. SECRETARY WALPOLE AND THE JACOBIN'S FRIEND.

(1858.)

A GOVERNMENT ought to be more scrupulously just and

more considerately generous than private individuals, for they have

unlimited powers of damage, annoyance, and penal revenge in their hands.

They can strike at the innocent and guilty alike, and that passes for

commendable vigilance in them which in individuals would be seen to be

rank spite. The Dr. Bernard trouble did not end with his acquittal.

One not a Frenchman, but because he was a friend of Dr. Bernard, became a

person of so much interest or anxiety to the English Government that they

offered £200 for his head. They did not put it in that plain way,

but their object was to try him for his life. He was known as a man

of noble friendships and generous courage, or he had not permitted himself

to be regarded as Dr. Bernard's personal acquaintance.

His high spirit, his disinterestedness, his philosophic mind

and personal intrepidity, were a constant cause of inspiration to all who

knew him. He became, as I have said, the subject of solicitude on

the part of the Government, who thought they had international reason for

hanging him. They had no just cause for such belief, but made a show

of assiduity in the matter, to gratify the susceptibility of the Emperor

of the French, who was then considered our "good ally." The friend

whose death was sought Dr. Bernard and I sometimes met at the White Swan

Hotel, Covent Garden, and at Ginger's Hotel, which, as I have said, then

stood near Palace Yard, Westminster Bridge Road.

|

|

|

Spencer Horatio Walpole

(1806-98) |

After the Lepelletier affair, the Government were induced to

offer a reward of £200 for the discovery of my friend, who, having means

of knowing what was in their minds, was nowhere apparent in the British

dominions. For two years he was an exile. The reward for his

apprehension being still in force at the end of that period, I and Mr.

Baxter Langley waited upon the Home Secretary, who in those days was Mr.

Spencer Walpole. We presented ourselves to him as persons who had a

friend to sell, provided we were sure of payment. We were not so

lost to self-respect as not to put a price upon our virtue. We were

prepared to be perfidious for £200. On our being guaranteed the

reward, the gentleman the Government desired to see would appear. He

had no objections to being hanged if that was thought right, but, being

accustomed to outdoor life, he objected to be imprisoned, but would (he

instructed us to say) present himself on the day appointed for trial.

We stated that the reward offered for his appearance, which we applied

for, was to defray the cost of his defence, as it was not reasonable that

any one void of offence should be put to expense to prove it. Though

aided by gratuitous services on many hands, Dr. Bernard's defence cost him

£850. He, with no means but his earnings, had many lectures,

lessons, and prescriptions to give before he paid that serious bill.

All we asked further was that when our exiled friend appeared within

British precincts, the police who might become aware of it should not have

a right of reward as against us, who brought him within their range.

The Government took time to consider the proposition. The sagacious

Home Secretary surmised some plot, and Mr. H. Waddington, writing from

"Whitehall, June 18, 1858," told us that " he was desired by Mr. Secretary

Walpole to inform us that the reward of two hundred pounds offered by the

Government in the case referred to by us had not been withdrawn."

This was so far assuring—the money was to be had if we could induce Mr.

Walpole to sign a cheque for it.

My friend the "Man in the Street" (the writing name in the

Morning Star of Mr. Langley) took steps in his way, and I in mine,

to cause Mr. Walpole to know that the object of the application made to

him was simply the return home of the political wanderer in whom the

Government had taken such complimentary but mistaken interest. Mr.

Milner Gibson put one of his skilful questions in the House of Commons.

Mr. William Coningham, M.P. for Brighton, always for justice, spoke

with Mr. Walpole. In twenty-four days Mr. Waddington wrote a much

more intelligent and satisfactory letter, thus:—

" WHITEHALL,

July 12, 1858.

"GENTLEMEN,—I

am directed by Mr. Secretary Walpole to inform you that, since the date of

my answer to your application, the law officers of the Crown have been

consulted and have expressed the opinion that it is not advisable to take

any further steps in the prosecution in question. The Government

have consequently determined to put an end to the proceedings against that

gentleman and to withdraw the offer of a reward of £200 for his

apprehension.—I remain, Gentlemen, your obedient servant, H. WADDINGTON.

"Mr. G. J. Holyoake—Mr. J. B.

Langley."

This letter was a charter of freedom. Mr. Walpole, in his

gentlemanly way, so intended it. It was explicit and complete.

We have had Home Secretaries and Irish Secretaries who would have gone so

far as to say that the reward was withdrawn, and have kept silence as to

whether other "proceedings" might or might not take place at the

discretion of the Government. The terms of our letter of inquiry as

to the reward would have been answered and no more. All the

requirements of cold, contemptuous, red-tape courtesy would have been

fulfilled, and we could have made no complaint. Besides, Mr. Walpole

was under no necessity of showing civility to one reputed to be a friend

of Orsini and Dr. Bernard, however distinguished his social position might

be. In the opinion of Mr. Walpole's class, insolence would not only

have been condoned, it would have been applauded, as we have since seen

with Irish gentlemen. Silence as to future proceedings would have

been thought politic. The Emperor of the French had his views of the

affair; and silence as to whether "further steps were put an end to" would

have amounted to an unexpressed ticket-of-leave, without incurring the

odium of formally issuing it, although no trial had been held and no

verdict of guilty given. Dr. Bernard's friend, as a gentleman of

independent spirit, would have still remained under accusation and must

have stayed abroad. But this was not Mr. Walpole's way. He did

not agree with us on any question of opinion or politics, but he was a man

of honour—an adversary of generous instinct—and his letter was a charter

of acquittal. Withdrawing the reward, he withdrew the charge.

And the exile returned to England, and dwelt many years in the land with

honour.

CHAPTER LXXI.

LORD PALMERSTON AND FEARGUS O'CONNOR'S SISTER.

(1858-64.)

LORD PALMERSTON was a Minister

for whom I had respect without sympathy. He was without prejudice,

and without enthusiasm. Mr. Cobden said of him he was absolutely

impartial, having no bias, not even towards the truth. This was not

a general estimate of him, but provoked by an incident as to what Mr.

David Urquhart called the "falsification of the Burnes despatches."

Personally Lord Palmerston was capable of generous things, but in politics

he was a Minister of the stationaries, and for years was kept in office by

Whig and Tory, because he could be trusted not to do anything. He

never said he was the enemy of reform, but he never "felt like" promoting

it.

The author of no great measure, the advocate of no great

cause; like the singer, the dancer, and the actor, Lord Palmerston's

genius was personal, and died with him. His power of waiting was

something like Talleyrand's. He became great simply by living long

and keeping his eyes open. His length of days was an advantage to

him in diplomacy, as he knew all the tricks of two generations of

intriguers all over the world, and had Palmerston any passion for the

service of the people he had opportunities to do them good. His face

was wrinkled with treaties. If pricked, he would have bled

despatches.

The best thing ever said of him was that foreign tyrants

hated him. It was not clear in his day why they did. The

reason being he was seldom ready to befriend them. He caused the

recognition of Louis Napoleon's usurpation which disgraced England and set

France against us. Yet Palmerston had merits which those whose

aspirations he opposed were unable to estimate, or Mr. Gladstone would not

have esteemed him so highly as he did. It was brought against him by

Liberal leaders abroad, that he held out to them hopes of assistance, but

rendered none when the time for it came. Still it was to his credit

that he had diplomatic sympathy with their aims. It was seldom they

found that in an English Foreign Minister. Any foreign leaders whom

I knew, who spoke to me on the subject, I warned against expecting

anything more than sympathy (and they might be glad if they got that), as

the Foreign Office was quite independent of the people, and very often a

generous Minister could not, under dynastic restraints, do what he wished.

About 1838 I was asked to join a political society which met

at Mr. Jenkinson's (No. 6, Church Street, Birmingham), a bookseller

and politician. It proved to be a Foreign Affairs Committee,

established by David Urquhart. The object of the society I found to

be to cut off Lord Palmerston's head. Things were bad among workmen

in those days, and I had no doubt somebody's head ought to be cut off, and

I hoped they had hit upon the right one. The secretary was a

Chartist leader named Warden, who ended by cutting his own head off

instead, which showed confusion of ideas by which Lord Palmerston

profited. Poor Warden cut his own throat. He was a man of

ability, and had a studious mind. He gave me a volume of the

speeches of Demosthenes, which he often read. It bore his name

written in a neat hand. Lord Palmerston was not to be assassinated,

but "impeached" in a constitutional way, and the block at the Tower was to

be looked up, and the too long disused axe was to be furbished and

sharpened for the occasion. This was my first introduction to

practical politics.

Lord Palmerston always had an airy indifference of manner—Punch

drew him with a straw in his mouth, as though he regarded politics from a

sporting point of view. Buoyancy was his characteristic.

Shortly before his death, when he was more than 80, I watched him crossing

Palace Yard, one summer evening, when the House was up early. Cabs

were running about wildly, but he dodged them with agility, and went on

foot to Cambridge House, in Piccadilly, where he resided.

This notice of Lord Palmerston is, of course, confined to

matters of personal knowledge, or of the influence he exercised on

agitations in which I was concerned or interested. Cobden warned all

reformers anxious for an extension of the franchise that nothing would be

done while Lord Palmerston lived. There was no hope until heaven

called him away. When at length he died, I wrote that "the political

atmosphere was fresher, if not sweeter." The Reform Club draped

itself in black as his remains passed by its doors. The Carlton Club

might have done this consistently. The Princess of Wales sat at the

window of St. James's Palace, next her own house, to see the

Premier's funeral pass. How they bury public men in Denmark I know

not. She could not be favourably impressed with the English way.

A dreary, ugly hearse, with horses carrying on their ribs a tinfoil,

gingerbread-painted plate of the Palmerston arms, was the tinsel centre of

the pageant—not inappropriate considering the noble lord's career as far

as the people were concerned.

He learnt from Lord Melbourne the art of doing nothing.

Melbourne valued most those advisers who could show him how a public

question could be let alone. Palmerston had the merit in his turn of

impressing Disraeli with the advantage of gaiety in politics. The

rich were glad to have reform put back with a jest, but working men had

not the same reason for satisfaction.

Towards the end of his life, Lord Palmerston was invited to

Bradford to lay the foundation-stone of the new Exchange. On that

occasion, the working men were desirous of presenting an address to him,

upon their wish for an extension of the franchise. Mr. Ripley,

chairman of the Exchange Committee, utterly ignorant of Lord Palmerston's

nature, refused to permit any approach to him. The worst enemy of

Lord Palmerston could not have done him a worse service. Nothing

would have pleased him better than to have met a working-class deputation.

His personal heartiness, his invincible temper, his humour and ready wit

would have captivated the working men, and sent them away enthusiastic,

although without anything to be enthusiastic about.

At that time, 1864, I was editing the English Leader,

read by many working-class leaders in Bradford. What I could do by

articles and lectures in the town to encourage them to maintain public

silence on Lord Palmerston's visit I did. They put out an address in

which they told the people that more was involved in the visit than the

ceremony of laying a foundation stone.

"The principal actor," they said, "being no less a personage

than the Prime Minister of England, the working classes will be expected,

by the promoters of the visit, to assemble in thousands, and give his

lordship welcome—receiving him with plaudits without a thought as to

whether the object of their homage is a friend or foe to their just rights

and privileges. But will it be wise on your part—who are as yet

unenfranchised, and mainly so through the influence of this Minister's

antagonistic policy—to greet him with demonstrations of gladness? What has

he ever done to merit it? Nothing. Then reserve your enthusiastic

cheers for such men as have with talent and influence—on the platform and

by the pen—advocated your social and political advancement in society as a

class. Working men, would it not be more manly and becoming to

exhibit, in some measure, your disappointment at the manner in which your

claims have been received—not by hisses and groans—but by a dignified and

significant abstinence from all cheering, or other noisy demonstrations of

joy?"

This was a remarkable address. I urged adherence to

this policy, saying, "The middle-class cannot cheer like the people.

Gentlemen never do it well; they don't think it respectable. It is

contemptuously said that the working class will cheer anybody, and Lord

Palmerston is just the man to make an argument against the people, if they

run after him. He is sure to say that 'they receive him with

acclamations as they do Mr. Gladstone; that their voices go for nothing,

for they have not the self-respect to keep their mouths shut, or sense to

tell a friend who would give them a right from one who will give them

nothing.'"

Bradford men did act on the advice given them. There

were said to be 30,000 in the streets. The Exchange Committee, and

friends of their way of thinking, did set up a cheer for Lord Palmerston,

but, not being taken up by the people, it had a faint-hearted effect, and

soon ceased. Lord Palmerston, as Mr. W. E. Forster afterwards told

me, was "touched and pained" at standing as it were alone in that vast and

voiceless crowd. No hissing or groans would have produced such an

effect. Hooting would have called forth counter-cheers, which would

have been magnified in the press into effective applause. Silence

could not be misrepresented.

Lord Palmerston, apart from Liberalism, had popular

qualities. He had boldness and common sense. No Minister save

himself had ever told the Scotch elders that it was useless to proclaim a

public fast to arrest the cholera until they had cleaned the city.

He thought more of scavengers' shovels than bishops' prayers.

In anything I wrote of him it was always owned that he had

generous personal qualities which adversaries might trust. On one

occasion I wrote to him, informing him "there was a Miss O'Connor living,

a sister of Feargus O'Connor, and the only survivor of the family.

She had more eloquence than her brother, but the poor lady was in very

straitened circumstances; and although Feargus O'Connor often denounced

his lordship, I believed he would not remember that against his sister in

her day of need. It would he regarded as a very generous thing by

the Chartists if his lordship would advise her Majesty to accord some

slender pension to Miss O'Connor."

She had written to me at times, by which means I became

incidentally aware of her necessitous condition. My friend Mr.

Thornton Hunt conveyed my letter to Lord Palmerston, who kindly sent me

word that "though it was not in his power at that time (the appointments

of the Civil List being made for the year) to propose a pension, yet if

the gift of £100 would be acceptable to Miss O'Connor, that sum should be

at her disposal."

I sent her the letters, which otherwise I should quote here.

I never heard further from her. The poor lady often changed her

address. Whether the letters ever reached her—whether she died in

the meantime—whether she accepted the offer and informed Lord Palmerston

privately of it as I advised her, I never heard. But Lord

Palmerston's generosity is a matter I record in his honour.

It was on Thornton Hunt's representation that Lord Palmerston

agreed to procure me a seat in Parliament. He said "he knew Mr.

Holyoake would often vote against him, but at the same time he should find

in him a fair adversary." Lord Palmerston's object was to show that

a working-class representative could be brought into Parliament, and

therefore there was no necessity for a Reform Bill for that purpose.

Lord Palmerston's death prevented him carrying his intention into

execution. Therefore I had reasons personally to respect Lord

Palmerston. But respect does not imply coincidence of opinion, and

it was on public grounds of political policy alone that I ever wrote

dissenting words concerning him. He had secular views which I could

well agree with. When Sir James Graham spoke in the China debate of

the approval of conscience and the ratification of a Higher Power, Lord

Palmerston declared that for his own part he did not look so far, and was

content with the support of that House. This was the real

Palmerston. The approval of conscience was always to be regarded,

but he took a just view when he suggested that peace or war was better

determined in Parliament by human than by ecclesiastical considerations.

CHAPTER LXXII.

THOMAS SCOTT—THE FRIEND OF BISHOP COLENSO.

(1858.)

ONE morning, at the Reception Room we kept at 147, Fleet Street, a

gentleman was announced who wished to see me. He was a tall man, of

military bearing, with a long

grey beard, abundant hair, and a voice of explosive power. It was

Mr. Thomas Scott, then of Ramsgate, well known among scholars for his

attainments in Hebrew literature.

After some conversation on means of circulating works of theological

criticism he was issuing, he said, with a pleasant frankness which I

afterwards knew to be

characteristic, "I had a great repugnance to meeting you, but I have come

at the suggestion of Bishop Colenso. I was making in his presence some

remarks against you,

when the bishop said, 'You go and see Holyoake; you will find the devil

is not so black as he is painted.'" In those days I was commonly thought

of under some Satanic

similitude, and Bishop Colenso was the first ecclesiastic who suggested an

abatement in the colour. I suppose I fulfilled the bishop's forecast

in point of hue, as Mr. Scott's

acquaintance passed into friendship which only ended with his death; and

many were the happy days I spent when his guest at his home in Ramsgate

and Norwood, which Mrs. Scott made enchanting to all visitors.

|

|

|

Thomas Scott |

Mr. Scott, I understood, had been employed in some military capacity among

North American Indians. He told me he had camped out for two years at a

time, without

sleeping in a house. The son of a Scotch professor of great learning, he

had Hebrew in his blood, and when he came home he was a Tory in politics

and a Liberal in religion. Dr. Colenso had so much confidence in his critical erudition that he

submitted the proofs of his celebrated works to him. Mr. Scott presented

to me a bound volume of proof

sheets which he had corrected or revised for the bishop.

When Bishop Colenso went down to Claybrook, in Leicestershire, to preach,

the then Bishop of Peterborough (the predecessor of Dr. Magee) sent an

inhibition. Mr. Scott,

who was skilled in things ecclesiastical, was waiting in the churchyard

the arrival of the inhibition. The bishop's messenger did not appear until

Sunday morning, shortly

before the service would commence. Mr. Scott met him and demanded the

inhibition from him. Whether, from Mr. Scott's magisterial manner or

authoritative voice—for he had

the appearance of one of the Sanhedrim—the messenger thought he was

Bishop Colenso, or an official representative thereof, was never known,

but he at once handed the inhibition to Mr. Scott, who dismissed him and put the document in his

pocket. As Bishop Colenso found the inhibition never came, he preached in

due course. The inhibition

would have been respected had it been delivered; but as it was not, the

Bishop of Peterborough could do nothing against Dr. Colenso. All the

bishop could learn was that his messenger had delivered his inhibition to

a gentleman whom he supposed to be authorised to receive it, and who

neglected to deliver it to Dr. Colenso until after the sermon

had been delivered. Dr. Colenso knew nothing of it until after, and was no

party to its being intercepted.

Mrs. Scott, who was in earlier years a ward of Mr. Scott, was a lady of

singularly bright ways—and the aptest, most indefatigable post parcel

maker in the world. The

innumerable pamphlets issued from their house were mostly made up by her.

No committee could have conducted the remarkable propagandist bureau Mr. Scott

administered. He being a gentleman, writers with a secret as to their

authorship could trust him, when a committee, however honourable, could

not command the confidence

which was accorded unhesitatingly to one. He was an institute in himself. Ecclesiastics (Bishop Hinde was one) professors, and others to whom it was

not convenient to give

their names to the public, wrote for him. His house was a theological

pamphlet manufactory. Ladies were among his contributors. In some cases

atheists wrote, whose names it would not have been prudent in Mr. Scott to print, as their

arguments on independent subjects would have been misjudged. Mr. Scott

himself was an ardent,

unswerving Theist. His own works were as remarkable as any he published

from the pens of others. He issued more than two hundred separate works to

my knowledge—none

of them mean or unimportant. The whole constituted a pamphlet library of

controversy never equalled.

Mr. Scott died, and no successor has appeared. As the wise adviser and

intrepid friend of Bishop Colenso, he will long live in the memory of all

who knew how great his

services were. To others, the old warrior devoting his years to scholastic

research and criticism, with the enthusiasm of a young professor, will be

a singular figure. He was

the greatest propagandist by pamphlets of his own origination ever known

to me, in reading or experience.

CHAPTER LXXIII.

HOW BISHOP COLENSO BECAME CONVERTED.

(1860.)

ON one or two occasions I met Bishop Colenso. His earnest, alert,

inquiring demeanour, his frankness and tolerance would suggest to any one

that he was for truth first and

faith afterwards.

|

|

|

John William Colenso

(1814-83) |

One Sunday night I was lecturing at the Hall of Science, City Road. At the

conclusion notice was given out that it was expected Bishop Colenso would

speak in that place

next Sunday. He had been invited to lay his views before the audience

assembling there. Simple as a child in matters of duty, he was ready to

vindicate his views before any

whom he supposed to be earnest inquirers. He never counted the risks; he

never thought of them. Though he rejected the literary and arithmetical

errors of the Scriptures, he

was deeply Christian, while the audience he would have met were not so. I

at once said it would be unfortunate for the bishop's cause if he came

there, and I wrote and told

him so. The Hall of Science had an atheistic reputation, and his enemies,

who were then very fierce against him, would never dissociate his

appearance at the Hall of

Science from sympathy with the far-reaching heresy promulgated in it. It

would have been a distinction to the side to which I belonged that the

bishop should appear

among us, but it would not have been generous in us to have permitted it

at his peril. The audience, I was glad to see, thought so too.

The bishop sent me a brief note of thanks, and did not appear there.

He may have had this incident in his mind when he told Mr. Scott that I was a

paler sort of Satan than I

was usually represented to be.

Or Bishop Colenso may have had in memory an earlier incident. When he was

appointed to the See of Natal, he selected (I forget how it came to pass)

an intelligent Secular

carpenter and frequent correspondent of the Reasoner—Robert Ryder— to go

out and build his church and school-house. Mr. Ryder, when I first knew

him, was employed at

New Leeds, near Bradford. He afterwards came to London, and kept a small

inn off Gray's Inn Road, which he gave up to go to Natal. As Ryder had

never been abroad, he

asked my advice as to going, and I encouraged him to accept the Natal

engagement. He had become acquainted through the Reasoner with Herbert

Spencer's writings, and

was his earliest disciple whom I knew. His fascination was the first

edition of "Social Statics." It was to him as a new Gospel. He had a copy

with him wherever he went. Its

contents had coloured his mind, and he took the book with him to Natal. He

was in the bishop's employ several years, and sent me photographs which he

had taken of the

actual Zulus who were said to have converted the bishop, long before any

such conversion was heard of in England. This English carpenter and

builder was an agnostic, an

enthusiast, and a ready disputant. Zulus were workers under him, and the

bishop saw them daily and conversed with them as to their religious views,

so far as they had any.

They were very shrewd and good at argument, as the bishop admits in one of

his works. My friend told me that the Zulus used to remark upon the fact

that the bishop had a

room built in the rear of the church, in which he stored an

eighteen-pounder. They knew what that cannon was for, and they thought

that the bishop, fair-spoken as he was,

did not place his ultimate reliance on the "Good Father " in whom he told

them to trust.

Afterwards the bishop's builder came to consider that his contract was not

fairly fulfilled by the bishop, and sent me particulars for publication in

the Reasoner. I endeavoured

to dissuade him from an action at law which he contemplated. Being a

mathematician, the bishop was more likely to be right in matters of charge

than he. Besides, the

bishop was a gentleman as well as a Christian, and therefore to be

trusted. Further, it would be a scandal for a Secularist to go to law with

a good bishop, who had incurred

the enmity of his order by his splendid tolerance. It came to pass

that Mr. Ryder had to sue the bishop, when occurred the only instance in which

the bishop displayed the

prejudice and injustice too often the characteristics of his profession.

It was years before Bishop Colenso's criticisms of the Old Testament were

"noised abroad," when my friend Robert Ryder became his mechanical manager

of works in the

diocese of Natal. Mr. Ryder, in a letter which I published in the Reasoner

in June, 1858, said:—

"I am the same R. R. I was when you knew me in England. I have laboured

for the last three years to prove that it is possible for an atheist

(so-called), holding extreme

speculative views, to work with a party, for a secular object, whose views

are diametrically opposed to mine. I endeavour to prove in my own person

that duty, faithfulness,

and honesty are moral qualities independent of creed. I have risen to the

highest honour and confidence my employer can bestow upon me—not for what

I believe, but for what

I have done, and the manner in which I have served the mission in general. The bishop is quite familiar with my views, but he is one of those noble

men who adorn Christianity

by his consideration, his kindness, his life, and his freedom from all

intolerance. He often comes to get one of your works out of my library. I

have my esteemed employer's

certificate that I have served the cause well, and faithfully discharged

my duties for three years, and am going on for two more years. I have been

entrusted with thousands of

pounds. I have built three churches, three schools, a corn-mill, a 20-feet

water wheel fitted up with lathes and smithy, potter's wheel, and simple

machines; also an industrial

training school for the natives, one hundred of whom we have in training,

chiefly young boys. We do not attend much to the old ones. I brought a

brick and tile machine from

England, with which we have made about a million bricks. The natives have

made a great number by hand, a thing they never did before. I am now

building the Bishop's Palace, 120 feet frontage, with two wings of 80 feet

each, in the Elizabethan style of architecture."

This passage is interesting as showing how early and to how great an

extent the bishop provided, not only for the spiritual, but for the

material comfort and education of the

Zulus. In publishing Mr. Ryder's letter, I divested it of all names and

allusions by which any readers in England could connect it with the Natal

Mission. A letter from Brazil

and one from Mexico, equally divested of personal references, had brought

my correspondents trouble. Therefore no mention was made of any place in

Africa, and, as there

was no reason to suppose that the Reasoner circulated there, it was

concluded that any person referred to was sufficiently protected.

However, the Rev. Calvert Spensley,

being in England, called at the Reasoner office and purchased some

numbers, one of them containing the letter in question. He

recognized that the scene of Mr. Ryder's

work was at Ekukanyeni, and sent the letter in the Reasoner to the editor

of the Natal Mercury, who reprinted it under the imaginative title of

"Atheistic Socialism in Natal." Mr. Ryder had been before described by the editor of the

Mercury as "the

bishop's very liberal-minded, shrewd, and independent agent." All

that could be brought against Mr.

Ryder was that in 1848 he had been on a deputation to Paris to

congratulate the Government on the establishment of the "Republic

Democratic and Social." The bishop was

now assailed for employing such an agent, and charged with disseminating

"Atheistic Socialism." Not a thought was given nor a word of

consideration said that Mr. Ryder

had, in spite of his convictions, generously devoted himself to aiding the

mission work and in increasing its reputation and influence by building

the churches and schools, all

the while keeping silence on his own opinions that the bishop and his work

might not be compromised.

The Rev. C. Spensley was engaged upon a rival Dissenting Mission, and his

party naturally took pleasure in disparaging the Church Mission; but it

was not justifiable to do it

by untrue and venomous accusation.

Mr. Ryder defended himself in a clear, manly letter in the

Natal Star. He

said: "I have never made a profession of atheism. I engaged to the

Bishop of Natal as mechanical

manager to the Mission. My labours have been perfectly secular, having

nothing whatever to do with either Theism or Atheism. Neither have I taken

any part in matters political or religious, private or public, or sought

to obtrude any views of mine on those subjects since I came to this

colony."

He accounted for the hostility of the Natal Mercury, the organ of the

Dissenting Mission, by stating that the editor had made overtures to join

the Church, and "offered himself

to the bishop body, soul, and paper," which being refused, the editor was

resentful.

The rival mission succeeded in doing the Church Mission some harm.

As soon as Mr. Ryder's letter to the Reasoner appeared in the colony—in

which letter Mr. Ryder had

said "the Zulus had intelligence, truth, probity, and chastity, all the

virtues of the Christian nations without their vices, and he did not see

what Christianity could do for them"—the bishop discharged him, lest the Church Mission should suffer;

and Mr. Ryder was obliged to appeal to the law to recover the claim he had

against the bishop. The decision was given in Mr. Ryder's favour. The bishop then appealed against

it and lost. The judges confirmed the decision in favour of his late

agent. An attempt was made to disqualify Mr. Ryder's evidence by reason of his opinions, but his word

was believed against the bishop. The judge who gave the judgment of the

court said: "If I followed feeling and class prejudice, I should

decide in favour of the educated man of my own class, rather than for the

uneducated man Ryder. But justice stands in the way."

Ryder had no written engagement, but his character went with his word.

It is singular that the bishop, whose characteristic was just-mindedness,

should have been unfair to one who was not a Theist. He was prejudiced

against heresy when he

was ignorantly described as having sympathy with it. He afterwards saw,

when Christian persecution befel him, that truth and fairness often

co-existed in persons who did not

hold his theistical belief—from which belief he never departed himself.

Mr. Ryder had seen frequent accounts and quotations in

the Reasoner of Lieut. Lecount's "Hunt after the Devil," and probably had the book in his

library. There was nothing

about the "Devil" in Lecount's three volumes, which were filled with

calculations of the dimensions of the ark, with reference to its required

capacity. The chief statements of

the Old Testament which could be tested by figures, Lecount, being a great

mathematician, had presented with an originality and vividness not before

shown. If the bishop

had not seen the book, it was a remarkable coincidence that he should go

over the same ground in the same way, applying the same methods, and

arriving at similar results.

Any reader of this chapter will see the bishop had ample means of becoming

acquainted with the intellectual difficulties of heretics. Being himself

an accomplished

arithmetician, the investigation by which he became distinguished was

natural to him, and it was quite out of the line of any Zulu to suggest

it. The Zulus were strongest

concerning the difficulties of Theism; but the bishop was never in any

degree moved by their arguments, except so far as their intelligence and

earnestness may have inspired

him with tolerance and respect for extreme difference of belief. The Zulus

had a quick sense of moral preception, of the discrepancies between

profession and practice, but

these were points upon which the bishop did not deal in his Pentateuchal

criticisms. He dwelt mainly with intellectual and scientific objections.

When his first volume on the Pentateuch came out it was

said of him—

|

"To Natal, where savage men so

Err in faith and badly live,

Forth from England went Colenso,

To the heathen light to give.

But, behold the issue awful!

Christian, vanquished by Zulu,

Says polygamy is lawful,

And the Bible isn't true!" |

The bishop had not said this, but it was quite as near to the truth as

clerical criticism usually gets on its first effort. Dr. Cumming was one

of his adversaries. He was an

ingenious prophet who predicted the end of the world in a certain year,

and at the same time negotiated a lease of his house for a much longer

period, whereby he obtained a

reduction of rent to which he was not morally entitled. He issued some

frenzied pamphlets entitled "Moses right, Colenso wrong," which I

answered by another series

entitled "Cumming wrong, Colenso Right; by a London Zulu." Bishop

Colenso certainly showed that an educated Christian gentleman, who had

sympathy for the people and

a genial toleration of the pagan conscience, could do much for their

elevation in the arts of life.

The bishop took his beautiful electrical apparatus and delivered lectures

with experiments in Natal to the great delight of the Zulus, who in their

grateful and appreciative way

called him Sokululeka, Sobantu, "Father of raising up"—"Father of the

People." No Zulu heart would apply such honouring words towards Dr. Cumming, whose divinity was a

snarl and his orthodoxy a sneer. One day I sent the bishop a set of the

pamphlets I had written in reply to his adversary. Here in his answer

dated from Pendyffryn, Conway, July 25, 1 863:

"DEAR SIR,—I am much obliged by your note. I enclose a letter from

Professor Kuenen, of Leyden, which you may like to see. He ranks not

merely among the first—but, I believe, as the first—of living

Biblical critics, and treats my book rather differently from Dr. Cumming

and Co.—Faithfully yours, J. W. NATAL."

The bishop also sent me the third part of his "Examination of the

Pentateuch" on its publication.

Next to Hue and Gabet's Travels in Tartary, Bishop Colenso's " Ten Weeks

in Natal " is the most alluring missionary book I ever read. Had

ecclesiastical appointments gone

by merit in Colenso's time, he would have been made Archbishop of

Canterbury, as he had more learning and more Christianity, in the best

sense of the term, than any

contemporary prelate. With noble self-sacrifice he ended his days among

the Zulu people. He was the friend of their kings—he was ceaseless in

pleading for justice to

Cetewayo. He was the only bishop for centuries who won the love of a

barbarian nation.

Mr. Ruskin, whose regard is praise, presented his large diamond to the

Natural History Museum on the condition that the following words should

always appear on the label descriptive of the specimen:—"The Colenso

diamond, presented in 1887 by John Ruskin in honour of his friend, the

loyal and patiently adamantine first Bishop of Natal."

CHAPTER LXXIV.

LORD COLERIDGE AND THOMAS HENRY BUCKLE.

(1859.)

Mr. JUSTICE ERSKINE, in his address to me, said in 1841, that "the arm of

the law was not stretched out to protect the character of the Almighty. The law did not assume

to be a protector of God." But he used it so all the same. His words,

however, admitted that blasphemy, as respects Deity, is not a crime which

the law takes cognizance

of. Blasphemy is only a secular concern, a crime that affects the

peace and taste of society.

Blasphemy is an erminic creation. In the eyes of a Theistical moralist,

orthodox Christianity is blasphemy of a bad kind. Yet a judge seldom

considers that the conscience of

an atheist is outraged by ordinary Christian language. Usually the judge

protects Christians alone, and, according as he is bigoted or tolerant

himself, his definition of

blasphemy is malignant or generous. In cases of opinion judges make the

law, and when a Lord Chief Justice is tolerant it is fortunate, since his

judgment becomes a

precedent which minor judges respect. Lord Coleridge, in giving

judgment on certain publications two or more years ago alleged to be

blasphemous, said to the jury:—

"If the law as I laid it down to you is correct—and I believe it has

always been so; [23] if the decencies of controversy are observed,

even the

fundamentals of religion may be

attacked, without a person being guilty of blasphemous libel.

There are many great and grave writers who have attacked the foundations of

Christianity. Mr. Mill undoubtedly

did so; some great writers now alive have done so too; but no one can

read their writings without seeing a difference between them and the

incriminated publications, which I am obliged to say is a difference not of degree, but of kind. There is a

grave, an earnest, a reverent, I am almost tempted to say a religious tone

in the very attacks on

Christianity itself, which shows that what is aimed at is not insult to

the opinions of the majority of Christians, but a real, quiet, honest

pursuit of truth. If the truth at which

these writers have arrived is not the truth we have been taught, and

which, if we had not been taught it, we might have discovered, yet,

because these conclusions differ from ours, they are not to be exposed to

a criminal indictment. With regard to these persons, therefore, I

should say, they are within the protection of the law as I

understand it."

This judgment gives protection against Christian penalties to such writers

as Buckle, Carlyle, Harriet Martineau, Huxley, Tyndall, Morley, and

Spencer. It is the amplest Charter of Free Discussion yet

promulgated on high authority in any nation or in any country.

|

|

|

Harriet Martineau

1802-76 |

One day Mr. William Coningham, then M.P. for Brighton, took me to call on

Thomas Henry Buckle, who was residing with his mother in Sussex Square in

that town. Mr.

Coningham had often spoken to me of Mr. Buckle as one who had long been

engaged on a great work which would make an impression upon the age. It

proved to be the

"History of Civilization," which was afterwards published. It was Sunday

morning when our visit was made. Mr. Buckle wore a light dress; he had a

fresh complexion, a

welcoming manner, and appeared to me as a country squire with unusual ease

and readiness in conversation. He did not give me the impression that he

was a philosopher, a man of ideas, of studious and immense research; but I

knew all this when I subsequently read his review in Fraser's Magazine for May, 1859,

of John Stuart Mill's famous

treatise on "Liberty." After thirty years I have read the review again

with equal wonder and admiration. We have no such reviews in these days. We have writers whose

sentences of light and music linger in the ear of the mind, but we have

none who have Buckle's passionate eloquence and generous eagerness in

defence of unfriended

heretics.

It was in that review that he animadverted on the trial of Thomas Pooley

before Mr. Justice Coleridge, at Bodmin, in 1857, and on the part taken by

Mr. John Duke Coleridge

(now Lord Chief Justice Coleridge), who was the prosecuting counsel

pleading before his father. I had written a narrative of the career and

trial of Pooley, having been down to Cornwall, at the instance of the

Secularists of that day, to report upon Pooley's case. Mr. J. D.

Coleridge replied to Mr. Buckle in defence of his

father, Sir John Coleridge, and himself, and stated, in his remarks in Fraser's Magazine,

for June, 1859, "that every fact mentioned by Mr. Buckle is to be found n the

aforesaid report, and often nearly in the language of Mr. Holyoake." It was so.

Mr. Mill had mentioned my

name in " Liberty," and that of Pooley, which led Mr. Buckle to inquire of

me what the facts of the

case were. I sent him my published narrative. Though I had been long

before, and was at the time, exposed to a storm of clerical persecution,

no resentment colours that

story. There is no publication of mine which I would more willingly see

reprinted, and by which I would consent to be judged as a controversialist

narrator, than by that. But in any such reprint I should withdraw

the phrases in which I represent that Mr. J. D. Coleridge "concealed facts from the jury," or was otherwise

consciously unfair; nor should I

use the same accusatory words I did in speaking of Sir John Coleridge, the

judge. Afterwards, when the remission of Pooley's sentence was sought, and

the Judge consulted

upon it, he wrote to say that " he saw no reason why Pooley should not

receive a free pardon under the circumstances stated." At the same time he

remarked that he did not

suspect Pooley's insanity, that " there was not the slightest suggestion

made to him" thereunto, nor had he been led to inquire into it, and "he

should have been very glad "

to arrive at the conclusion he was insane and have " directed his

acquittal on that ground." Mr. J. D. Coleridge on his own part said

in his reply to Mr. Buckle: " I took pains to

open the case in a tone of studied moderation. I carefully explained to

the jury that the prosecution was not a prosecution of opinion in any

sense. I mentioned, and I beg their pardon for here repeating, the

names of Mr. Newman, Mr. Carlyle, and Miss Martineau, as persons who maintained what I and others might think

erroneous opinions, but who

maintained them gravely, with serious argument and with a sense of

responsibility, and whom no one would dream of interfering with. I said

that the time was long gone by for

persecution, which I thought as foolish as it was wicked; but that as

liberty of opinion was to be protected, so was society to be protected

from outrage and indecency." This is not only entirely fair; it is a

generous interpretation of freedom of speech, and is consistent with what

Mr. Coleridge, as Lord Chief Justice,

avowed in yet more remarkable

language twenty-six years later. There was no report of the trial. No one

whom I could meet in Cornwall was aware of what had been said to the jury,

and the strange severity

of the sentence hid from my mind the probability of its being said. The

letter of the judge and the speech of the counsel I have quoted show that

I was wrong in saying that

there was a "concealment" of facts, or "shameful reticence" on his part,

or in suggesting conscious unfairness on his father's part. As I am the

only person remaining on Pooley's side, conversant with the facts of the trial as they subsequently

transpired, it is a duty in me to make the correction.

Pooley had no counsel, no friend, and his side was not put before the

court. The Spectator, which in those days was always well informed on

these cases, had the only

report which appeared in the London press; the writer, probably a

barrister present, was struck with the signs of insanity in Pooley.

He remarks, however, that "Mr. Coleridge was quite correct in his

statement of the law as it stood."

My own opinion of the clergy of Liskeard, of public opinion there and in

Bodmin, of the extraordinary indictment, of the lack of discernment in the

jury, and of the strange

extent of the sentence pronounced, remain the same. At the same time, it

must be owned that Pooley's manner of acting, with which, as my narrative

shows, I did not

sympathize and did not conceal, must have set all uninquiring,

unsuspecting persons against him.

Had what I learned of Pooley's life been known to the counsel and judge,

their trial of Pooley would have ended differently. Had I known what

limited knowledge of facts the

court had of Pooley's history, I should have written differently of those

who conducted the trial and decided his fate. It did not seem to me to be

possible that the pathetic

facts of Pooley's life, for fifteen years known to his family, neighbours,

and employers, could be unknown to gentlemen in the same town. It was not

then known to me that

Truth is more lame-stepping than justice, and is very dilatory in making

known what she knows. It was not then known to me that the rich know no

more of the lives of the

poor than persons on land know or care to know of the ways of fish in the

sea. It was not known to me that theological prejudice may so close the

eyes and ears of the mind

that it neither sees nor hears outside itself. It was not known to me

then, as it has been since, that in political warfare educated gentlemen

on one side do not believe in the

integrity of equally educated gentlemen on the other side, and not only

put on their acts a construction never thought of by the actors, but will

report as true the falsest

charges after they have been publicly and often confuted. So I did think,

without misgiving, that the pagan insensibility of Pooley had excited the

indignation of counsel and

judge, and led them to ignore the facts which I supposed them to know.

Mr. Buckle, I doubt not, were he living to revise the statement he made, would

cancel all imputations upon the personal honour or conscious unfairness of

judge or counsel in this case, for Mr. Buckle himself invited all readers

of his to peruse the defence of Mr. J. D.

Coleridge, and he reprinted and circulated the most vehement passages

against himself, and they were hardly less fierce than his own. Mr. Buckle

always had fairness in his

mind, and his publishing and circulating the strongest passages in reply

to himself which his adversary had penned, is a proof of it. Only a candid

man who cared more for

the truth than for himself would do it.

That such a prosecution could take place and such a sentence as that upon

Pooley could be pronounced excited Buckle's generous indignation. His

brilliant defence of the

poor, crazed, but intrepid well-sinker of Cornwall, is the only example in

this generation or this century of a gentleman coming forward in that

personal way, to vindicate the

right of Free Thought in the friendless and obscure. Mr. Mill would

give money, which was a great thing, or use his influence, which was more,

to protect them, but Mr.

Buckle descended personally into the arena to defend and deliver them.

CHAPTER LXXV.

BEQUEST OF A SUICIDE.

(1860.)

IT is the common experience of those who advocate liberty in some new

direction to receive an unforeseen and undesirable adhesion of all the

"cranks," religious, social, and

political, extant in the innovator's day. I mean by a "crank" one who

mistakes his impressions for ideas, or, having ideas resting on proof only

perceived by himself, insists,

in season and out of season, on attention being given to them. He is a

crank, whatever his "views" may be, who persistently claims notice for

them before he has thought

them out to their consequences and described the grounds on which they

rest, so that others can discern and test them. The number of "cranks" are

much larger in most

parties than are supposed.

An innovator who knows his business presents his case as that of reasoned

truth. The "crank," not knowing the justification and conditions of

innovation, rushes at you from

all directions to carry his fad forward. But discrimination is necessary,

lest you repel a thinker who seeks direction or confirmation, which your

experience may afford him.

Sometimes a well-convinced but too ardent pioneer has fallen into evil

environments from which he cannot see his way out. Among these was

Bombardier Thomas B. Scott,

7th Battery, 8th Brigade, Royal Artillery, Cove Common, Aldershot. Having

the making of a good soldier in him, he enlisted in the Royal Artillery,

on being assured by the

recruiting officer that he should have the rank and pay of a bombardier

from the date of his entering the service. On this condition he

entered, but he soon found, as Mr.

Bradlaugh found, that faith is not kept with recruits in the army. Scott

found the condition was ignored, and when he complained, he was told it

was unauthorised and used

merely as an inducement for him to enlist. He concluded, therefore,

that as his enlistment was false and a fraud, it was illegal, and he wrote

to Mr. Sydney Herbert, who did

not deny the fraud, but did not redress it. The reply of the Secretary of

War was sent to me, which I returned or I would quote it. It seems strange

that a man of Sydney

Herbert's high character for honour neither accorded censure nor redress

for admitted deceit. Scott's personal character was good, but the position

assigned him was that of

a gunner merely. He was employed as schoolmaster, and received

certificates of competency from the General Inspector of Army Schools,

from two head normal

schoolmasters, and from his colonel, captain, and officers. He was

requested to stand examination as a candidate for a studentcy in the

Military Asylum at Chelsea. He did

so, and passed. He might have risen from the ranks, as was his ambition,

had it not been for his speculative opinions and his untimely zeal. He had

in camp some works I

had written, and others, "Volney's Ruins of Empires" among them. This

becoming known, he was arraigned before his colonel and officers on the

charge of being an

"atheist," though Volney was a Theist. A soldier enlists for the purpose

of being killed, as the exigence or convenience of war may warrant. Scott

did not object to this, and it

does not appear what these officers had to do with a gunner's opinions on

outside questions, entirely apart from his duty; and his trial for the

purely ecclesiastical offence

was irrelevant.

Scott made the mistake of considering it his duty to do as the apostles

did (which is only counted meritorious in them) of standing by his

opinions. For doing this he was

sent back to do his duty as a gunner, was denied the privilege of entering

the Normal School, and his prospects of military advancement were cut off. This made him

despondent.

In December the same year (1860) Scott had written to me to advise him as

to some mode of obtaining his discharge; but as I had no means of

procuring funds for that

purpose then, I counselled him to observe circumspection as to his

opinions until he could be bought off. He then, through his captain,

sought to speak to his colonel on the subject of Mr. Sydney Herbert's letter. He was received in a very

forbidding way. The colonel denounced him for his opinions, and told him

that if he would abandon them, he

would do something for him, and further told him that, until he did, he

should not allow him to hold any rank or appointment in the Royal

Artillery. Scott replied that his

convictions were involuntary, which he could not change until stronger

evidence appeared before him; that, if the colonel believed him to be in

error, it was his duty, as a

Christian, to convince him rather than coerce him. Whereupon the colonel

sent for the sergeant-major and ordered him to confine Scott in the

guardroom, and the charge of

insubordination to be entered against him. After two days' imprisonment,

Sunday occurred, and he was marched under guard to church. Scott,

therefore, desired a

communication to be made to the officer in charge to the effect that he

did not wish to enter the church, as his habit was to attend the Wesleyan

Chapel, which he

frequented, as all soldiers are obliged to attend some place of worship. Scott did not refuse to go, but expressed his wish not to go to church,

and claimed liberty of

conscience, as he did not agree with what he should hear in church. Being

offensively addressed by the officer, he refused to go. He was then sent

back into confinement,

and an additional charge of "insubordination" was entered against him. Eventually he was taken before a court martial. Twelve hours prior to his

trial, a copy of the charges

against him was given to him, and he was told to frame his defence, but

was denied writing material. He sent me a very dramatic account, on eight

foolscap pages, of the

whole affair. Around a large table in the mess-room sat three lieutenants,

two captains, one major, and one colonel. On the table lay the Articles of

War, a large Bible, and

Jamison's Code. The officers seized the Bible, and, placing finger and

thumb upon it, each kissed it, like cabmen, and swore to give justice on

all sides, which they could not

intend to do, being a military court without ecclesiastical functions or

competence.

Scott found the court martial a mere department of the Church. Every scrap

of evidence was made the most of against him; but when he attempted to

correct the

misstatements of his judges, he was put down. He stood up manfully for his

principles, which was considered a new offence. He said he was ready to

render the best

service in his power to her Majesty, and give his life in discharge of his

duty, but his conscience was his honour, and he could not change. They

might drive him to suicide,

but he would not deny his conviction. They did drive him to suicide, which

was discreditable in gentlemen. Scott, on his own showing, spoke very

plainly, and the court

resented his contumaciousness; but they should have remembered that they

had got him into their power by fraud, and after knowing it, they kept him

there. Being an

intelligent, logical-minded man, this injustice preyed upon him. How long

he was imprisoned I never heard. His health was broken, and he became an

inmate of the hospital.

There he had been two months when I next heard of him. He was daily

harassed about his opinions. The doctor, the chaplain, the lieutenant, a

captain's wife, and others

assailed him from time to time. He stated to a Roman Catholic comrade, who

had great regard for him, that he would give four years' service to any

one who would get him

bought out, as I learned afterwards. His own family were unable to do it. He had religious connections better able; but his opinions prevented his

being aided in that

quarter. Solicitous always and to the end that no discredit should come

through him to the cause he espoused, he provided that all his few debts

should be paid. His

prospects in the army ended, friendless and assailed, he died by his own

hand. A faithful comrade of his, having occasion to write to me in 1862,

informed me, in answer to

my inquiry after Scott, that he had long been dead, of which no notice was

sent me, although he had bequeathed what little property he had to me. I

wrote to the colonel of

his troop, and otherwise obtained information of his bequest. On learning

that his family had need of anything he had, I transferred all his

possessions to them, valuing all the

same this proof of the dying regard of which he intended to assure me. Thus closed the career of the brave suicide, who will have no record save

this.

In the Indian mutiny of 1857 the Mahometans would save any one who would

consent to profess himself a Moslem. Those who would not were knocked on

the head. Only

one half-caste saved his life by denying his faith. Mr. A. C. Lyall, an

eminent Indian official, wrote lines of noble praise of their heroic

honesty. One of those who thus died held

the same opinions as poor Scott. In Mr. Lyall's poem he tells of the

honest soldier's convictions and fate:—

|

"A bullock's death, and at thirty years!

Just one phrase, and a man gets off it.

Look at that mongrel clerk in his tears,

Whining aloud the name of the prophet!

Only a formula easy to patter,

And, God Almighty, what can it matter?

I must be gone to the crowd untold

Of men by the cause which they served unknown,

Who moulder in myriad graves of old,

Never a story and never a stone

Tell of the martyrs who die like me,

Just for the pride of the old countree.

Aye, but the word, if I could have said it,

I by no terrors of hell perplext—

Hard to be silent and get no credit

From man in this world, or reward in the next.

None to bear witness and reckon the cast,

Of the name that is saved by the life that is lost." |

These lines may fitly serve as Scott's epitaph. The conscientious heroism

of the heretic is as noble as that of the Christian.

Other soldiers have written to me at times, who had found that

volunteering to fight for the liberty of others did not include freedom

for themselves—not even of their own

minds.

CHAPTER LXXVI.

VISIT TO A STRANGE TREASURER OF GARIBALDI.

(1861.)

IN the year 1860 I was acting secretary to the

London "Garibaldi Fund Committee." In many towns money was

generously given for "the General," as Garibaldi was popularly and

affectionately called. In some cases money so subscribed was sent to

Garibaldi; in others taken to him, to prevent misadventure. Some

local treasurers neither sent it nor took it. Thus some sums were

lost, and others held back by persons who did not know where to send them

to; and in some cases a treasurer would refuse to part with the funds in

his hands until he was personally and specially certain of its reaching

the General. For the convenience and satisfaction of all who held

funds given for him, Garibaldi appointed Mr. W. H. Ashurst, his personal

friend, as his treasurer. Mr. Ashurst was known in America as well

as England for patriotic services and high character.

In an important town—not Newcastle-on-Tyne and not

Birmingham—it was known that a banker held upwards of £400, which the

General needed, but which never came to hand. I do not mention the

name of the banker, because he was much and justly esteemed for his

personal honour and interest in public affairs. In this narrative I

therefore speak of him as Mr. Marvell, itself an honourable name in

history. Mr. Ashurst wrote to him from 6, Old Jewry, London, E.C.

(April 15, 186 1), saying:—

"DEAR

SIR,—I

received on Saturday a despatch from General Garibaldi, from which I beg

to forward you the following extract:—

"'I have already by my last letter requested you to act as treasurer, or

collector-general, in your country, of all monies raised in aid of the

cause of Italy, and subject to my order, and this position I request you

still to hold—advising me as before of the amount in hand, as to the

disposal of which you shall from time to time receive instructions from

me.

"'I now urgently call upon you to let it be known to the various

committees and friends of Italy throughout Great Britain, that funds are

greatly needed to complete the good work of aiding in the emancipation of

those parts of our country which are still subject to priestly misrule and

foreign oppression, and the liberation of which will require all the

efforts of the patriots of Italy.'

"I have the pleasure of bringing this instruction under your notice, and

request that you will forward to me the balance remaining in your hands on

the General Garibaldi account.—I am, dear sir, yours respectfully,

"To D. M., Esq.

W. H. ASHURST."

To this friendly letter the following singular reply was sent, April 17,

1861:—

"DEAR SIR,—We

have peculiar notions on some subjects, and do not sympathise in all the

views set forth in your favour of the 13th inst.

"We decline to send any contributions to London, as we prefer to act

independently, and shall take our own course when the proper time arrives,

—I am, dear sir, yours faithfully,

"D. M."

It had been known for some time that this gentleman was unwilling to pay

over the money in his hands to the General's treasurer. At length

the London Committee of the "Garibaldi Fund" instructed Captain de Rohan,

the General's aide-de-camp, to ask him for a special authorisation to be

shown for the fuller satisfaction of hesitating and "independent" persons

Mr. Ashurst, on April 25, 1861, wrote again to the banker in question:—

"DEAR

SIR,—I received your letter of

the 17th inst., and communicated its contents to the committee. I

found that they had already communicated with General Garibaldi in order

to obtain from him some authority which should satisfy you as to the mode

in which you should apply the money in your hands collected for him; and

it is now my duty to enclose to you the original authority from General

Garibaldi, received by me this day, to send to me, as his treasurer, the

money you have in hand. I have kept a copy of the authority and of

the translation.

"In yours of the 17th, acknowledging mine of the 15th, you say that you

'do not sympathise in all the views set forth' in mine of that date.

On reference to my letter you will find I set forth no views, but simply

enclosed you the translation of a letter from General Garibaldi, and

requested you to act upon it.

"To me personally it is of course indifferent what you do with the money

the various contributors have confided to you for the Garibaldi Fund; my

duty is simply to follow out the instructions of General Garibaldi.

"I request the favour of your prompt acknowledgment of this letter,

stating the course you intend to pursue, and remain, dear sir, yours

faithfully,

W. H. ASHURST."

To this Mr. Ashurst received no reply.

Time went on and needs increased, for Garibaldi was still in

the field—but the money came not. Mr. E. H. J. Craufurd, M.P.

for the Ayr Burgh, being the Chairman of the Garibaldi Fund Committee,

then wrote to the banker resenting the distrust and non-compliance of the

request the general treasurer made in the name of the committee. No

notice was taken of this communication, and there was no prospect,

therefore, of obtaining the money. There was no legal remedy, and,

had there been, the committee would not have felt justified in expending

any funds to obtain it. I therefore proposed to the committee that

they should give me 30s., which would be the third class fare to and fro,

to go to the town where the money lay (I paying my personal expenses

myself), and I would collect the money for them. No one thought I

should succeed, but, as they were unable to obtain the money themselves,

leave was given me to try.

On arriving in the town I went to a society of working men,

some of whom had been subscribers to the local fund, and informed them

that the money intrusted to their treasurer had never been paid over,

although a request to do so had reached him from Garibaldi. Then I

asked them to make that fact known to other subscribers. Knowing

members of the congregation where Mr. Marvell worshipped, I asked them

whether it was possible that he could not be a man of good faith, or that

he could have any object in withholding the Italian fund which had been

intrusted to him from the uses for which it had been subscribed. We

could not understand in London why he should disregard the written request

of the General which had been sent him to forward the money to his

treasurer. My calculation was that Mr. Marvell would very shortly

have inquiries addressed to him by persons whose opinions he would not be

likely to disregard. He being mayor of the town, I next communicated

the information to such members of the Town Council as were known to me,

who were promoters of the subscription. They were astonished to

learn that the money was still in Mr. Marvell's hands. I remarked

that we understood him to be a man of unquestionable honour, which they

said was the case. I asked whether it was common in that town for a

banker to withhold money contrary to the wishes of the subscribers;

besides, it was not respectful to Garibaldi (to whom it was due), whose

friend he professed to be.

When I thought that news of these remarks made in the town by

me, as acting secretary of the Garibaldi Committee, who must know what he

was speaking of, had had time to reach the bank, I called there myself,

and asked for an interview with Mr. Marvell, on business of personal

importance. I was told that he was absent at his home, through

indisposition, and I was asked whether it was business the manager could

transact for him. I said I would explain my business to him, and he

might himself judge. I said we understood in London that Mr. Marvell

was a man of honour—that he not only kept public faith, but as a

magistrate was bound to vindicate it. The manager said that was so,

and Wished to know on what ground any question to the contrary could be

raised. I answered that he was aware that his principal was

treasurer to the Garibaldi Fund, and that subscribers in that town

entrusted their money to him in the implicit belief that it would, in

reasonable time, be paid over for the use of the General. But that

was not the case, as several hundred pounds were still detained at that

bank.

He admitted that the money was detained there, but said there

were reasons why it had not been paid over. I answered that I knew

that, but I had come down to inquire what those reasons were. Had

not Mr. Marvell received communications from the General authorising and

requesting him to pay all money in his hands for the General's use to his

treasurer in London, Mr. Ashurst? The manager admitted Mr.

Marvell had received them, but he was not satisfied with them. "That

means," I said, "that Mr. Marvell doubts their authenticity. If they

were genuine, he had no choice but to comply with them; and if he thought

they were not genuine, how came it to pass that he had taken no steps in

consequence? If they were not genuine, they were forgeries,

and it was an attempt, being practised upon him, to obtain by forged

documents money in his possession. Yet he had taken no steps to

expose the forgery, or warn the subscribers or the public that he held

proofs of so infamous a proceeding in his hands. The manager looked

a little confused at that aspect of the question. I therefore

added—"You are well aware who the persons are who have sent these

fraudulent communications from the General. One is Mr. W. H. Ashurst,

the Solicitor of her Majesty's Post Office, and the other is Mr. E. H. J.

Craufurd, a member of Parliament, and counsel for the Mint. If they

have taken to forgery, and have acquired such confidence in their success

that they can venture to practise upon a banker and a magistrate, so

distinguished for sagacity and public spirit as Mr. Marvell, that is a

very serious thing, which ought not to be concealed from the public.

The law ought to have been set in motion long ago. The

Attorney-General should have been informed of the proceedings of the

Solicitor of the Post Office, and the Speaker should have been made

acquainted with this conduct of a member of Parliament and counsel for the

Mint. If Mr. Marvell doubted the authenticity of Garibaldi's

communication, he could have sent it to Count Corti, or the Marquis

D'Azeglio, the Italian Minister in London, who knew the General's

handwriting well, and in twenty-four hours Mr. Marvell could have taken

proceedings; but he had, now for two months or more, concealed or condoned

this extraordinary and scandalous forgery. If he would give me Mr.

Marvell's address, I would at once proceed there, and speak to him upon

the subject."

Upon being informed of his residence, I took a cab and drove

straight to his house in the suburbs, where I was received by Mrs.

Marvell, who informed me that her husband was unwell, and unable to see

visitors. I said in that case I would await his recovery, although

the matter upon which I wished to see him was serious and of public

importance. Upon her remarking that if it were a matter which I

could communicate to her she might, at a convenient opportunity, mention

it to him, I told her precisely what I had told the manager of the bank,

which she appeared to hear with some consternation. I learned by

post shortly after that Mr. Ashurst had received £411 from Mr. Marvell,

the amount of all the subscriptions received by him.

I knew all the while why this banker wished to retain the

money in his hands, until he had opportunity of sending it to the General

himself. It was because he thought Garibaldi might direct its

employment by Mazzini, who was doing everything in his power to send

reinforcements into the field to aid the General. It was Mazzini who

inspired the men who shed their blood under Garibaldi's standard, and not

one sixpence of the money would have been used except in Garibaldi's

service. It was not the province of any treasurer to dictate how

money should be applied which was subscribed for services in Italy, of

which he was merely the custodian, and every hour he withheld it he was in

danger of imperilling Garibaldi's interest and his fortunes in the field.

CHAPTER LXXVII.

FAMOUS FIGHTS.

(1863.)

ARE science and courage a match for overwhelming

strength? Can a man skilled in the art of hand-fighting

overcome an antagonist immensely his superior in stature and power?

I saw this done at Wadhurst in 1863.

|

|

|

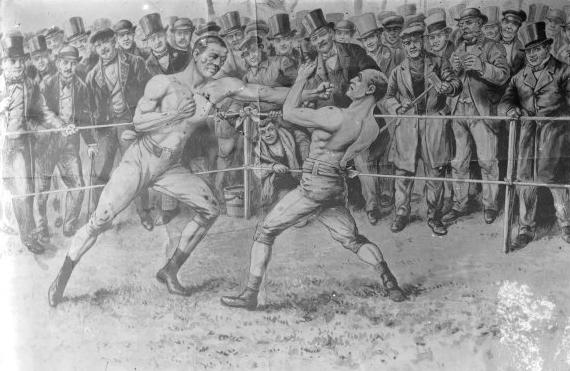

J. C. Heenan vs. Tom Sayers, Farnborough, 1860. |

After the fight between Sayers and Heenan it became a question whether

Heenan could be beaten. He certainly was not beaten by Sayers.

In his contest with Heenan, Sayers made a high name for English pluck.

Seldom had a short-built David of pugilism undertaken to fight such a

ponderous Goliath of Heenan's altitude. A single blow broke Sayers's

stout arm. Heenan struck like a battering-ram. It implied no

mean skill and pluck in Sayers to parry and return the blows of such a

tremendous assailant for many rounds, in that disabled condition.

Had not the ring been broken by the crowd, Heenan would have killed his

adversary. A subscription was made for Sayers at the House of

Commons, Lord Palmerston subscribing the first guinea. Exhaustive

training, excitement of victory and subsequent excess, have death in them,

and soon laid Sayers low. No contests or feats of great danger ought

to be encouraged. All whose presence incites them are morally

participants in self-murder, disguised as a spectacle in which the actor

kills himself for renown.