|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XXXI.

THINGS WHICH WENT AS THEY WOULD

I COMMENCE with Judge Hughes' first candidature.

There are cases in which gratitude is submerged by prejudice, even among

the cultivated classes. There was Thomas Hughes, whose statue has

been deservedly erected in Rugby. Three years before he became a

member of Parliament I told him he might enter the House were he so

minded. And when opportunity arose I was able to confirm my

assurance.

|

|

|

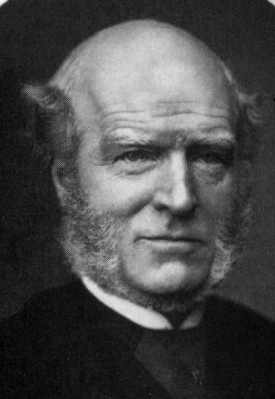

Thomas Hughes

(1822-96).

Author of Tom Brown's School Days |

One Friday afternoon in 1865 some Lambeth politicians of the middle and

working classes, whom Bernal Osborne had disappointed of being their

candidate (a vacancy having attracted him elsewhere), came to me at the

House of Commons to inquire if I could suggest one to them. I named

Mr. Hughes as a good fighting candidate, who had sympathy with working

people, and who, being honest, could be trusted in what he promised, and

being an athlete, could, like Feargus O'Connor, be depended upon on a

turbulent platform. I was to see Mr. Hughes at once, which I did,

and after much argument satisfied him that if he took the "occasion by the

hand" he might succeed. He said, "he must first consult

Sally"—meaning Mrs. Hughes. I had heard him sing " Sally in our

Alley," and took his remark as a playful allusion to his wife as the

heroine of the song. That he might be under no illusion, I suggested

that he should not enter upon the contest unless he was prepared to lose

£1,000.

The next morning he consented. I took him to my friends

of the Electoral Committee, by whom he was accepted. When he entered

the vestibule of the hall of meeting I left him, lest my known opinions on

other subjects should compromise him in the minds of some electors.

This was on the Saturday afternoon. I saw that by issuing an address

in the Monday morning papers he would be first in the field. On

Sunday morning, therefore, I waited for him at the Vere Street Church

door, where the Rev. F. D. Maurice preached, to ask him to write at once

his address to the electors. He thought more of his soul than of his

success, and reluctantly complied with my request. His candidature

might prevent a Tory member being elected, and the labours of the Liberal

electors for years being rendered futile, education put back, the Liberal

Association discouraged, taxation of the people increased, and the moral

and political deterioration of the borough ensue. To avert all such

evils the candidate was loath to peril his salvation for an hour.

Yet would it not have been a work of human holiness to do it, which would

make his soul better worth saving? That day I had lunch at his table

in Park Lane, while he thought the matter over. That was the first

and last time I was asked to his house. That afternoon he brought

the address to my home, then known as Dymoke Lodge, Oval Road, Regent's

Park, and had tea with my family. I had collected several persons in

another room ready to make copies of the address.

I wrote letters to various editors, took a cab, and left a

copy of the address myself, before ten o'clock, at the offices of all the

chief newspapers published on Monday morning. The editor of the

Daily News and one or two others I saw personally. All printed

the address as news, free of expense. Next morning the Liberal

electors were amazed to see their candidate "first in the field" before

any other had time to appear. All the while I knew Mr. Hughes would

vote against three things which I valued, and in favour of which I had

written and spoken. He would vote against the ballot, against

opening picture galleries and museums on Sunday, and against the

separation of the Church from the State. But on the whole he was

calculated to promote the interests of the country, and therefore I did

what I could to promote his election.

I wrote for the election two or three bills. The

following is one:—

|

HUGHES FOR LAMBETH.

Vote for "Tom Brown."

Vote for a Gentleman who is a friend of the People.

Vote for a Churchman who will do justice to Dissenters.

Vote for a tried Politician who will support just measures and can

give

sensible reasons for them.

Vote for a distinguished writer and raise the character of

metropolitan

constituencies.

Vote for a candidate who can defend your cause in the Press as well

as

in Parliament.

Vote for a man known to be honest and who has long worked for the

industrious classes.

Electors of Lambeth, vote for Thomas Hughes.

|

Mr. Hughes would have had no address out but for me.

Had he spent £100 in advertisements a day or two later he could not have

purchased the advantage this promptitude gave him. I worked very

hard all that Sunday, a son and daughter helping—but our souls did not

count. Two weeks went by—during which I ceaselessly promulgated his

candidature—and I heard nothing from the candidate. As I had paid

the emergency expenses of the Sunday copyists, found them refreshments

while they wrote, and paid for the cab on its round to the offices, I

found myself £2 "out of pocket," as lawyers put it, and I sent a note to

Mr. Hughes to say that amount would cover costs incurred. He replied

in a curt note saying I should "find a cheque for £2 within"—giving me

the impression that he regarded it as an extortion, which he thought it

better to submit to than resent. He never thanked me, then or at any

time, for what I did. Never in all his life did he refer to the

service I had rendered him.

A number of friends were invited to Great Ormond Street

College to celebrate his election, but I was not one. This was not

handsome treatment, but I thought little of it. It was not Mr.

Hughes's natural, but his ecclesiastical self. I withstood him and

his friends, the Christian Socialists, who sought to colour Co-operation

with Church tenets, which would put distraction into it. Association

with me was at that time repugnant to Mr. Hughes. Nevertheless, I

continued to serve him whenever I could. He was a friend of

Co-operation, to his cost, and was true to the Liberal interests of the

people. My daughter, Mrs. Praill, and her husband gave their house

as a committeeroom when Mr. Hughes was subsequently a candidate in

Marylebone, and she canvassed for him so assiduously that he paid her a

special visit of acknowledgment.

|

|

|

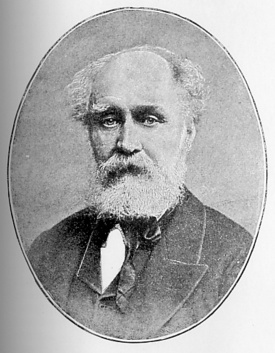

Edward Vansittart Neale

(1810-92) |

The Christian Socialist propaganda is another instance of the

wilfulness of things which went as you did not want them to go. In those

days not only did I fail to find favour in the eyes of Mr. Hughes—even

Mr. Vansittart Neale, the most liberal of Christian Socialists, thought

me, for some years, an unengaging colleague. General Maurice, in the Life

of his eminent father (Professor Denison Maurice), relates that Mr.

Maurice regarded me as an antagonist. This was never so. I had always

respect for Professor Maurice because of his theological liberality. He

believed that perdition was limited to æons. The duration of an

æon he was not clear upon; but whatever its length, it

was then an unusual and merciful limitation of eternal torture. This cost

him his Professorship at King's College, through the enmity, it was said,

of Professor Jelf. I endeavoured to avenge Professor Maurice by dedicating

to Dr. Jelf my "Limits of Atheism." Elsewhere I assailed him because I had

honour for Professor Maurice, for his powerful friendship to Co-operation. When the news of his death came to the Bolton Congress it was I who drew

up and proposed the resolution of honour and sorrow which we passed.

It was always the complaint against the early "Socialists"—as the

Co-operators were then called—that they mixed up polemical controversy

with social advocacy. The Christian Socialists strenuously made this

objection, yet all the while they were seeking to do the same thing. What

they rightly objected to was that the chief Co-operators gave irrelevant

prominence to the alien question of theology, and repelled, all persons

who differed from them.

All the while, what they objected to was not theology, but to a kind of

theology not their own, and this kind, as soon as they acquired authority,

they proceeded to introduce. They proceeded to compile a handbook intended

to pledge the Cooperators to the Church of England, and I received

proofs, which I still have, in which Mr. Hughes made an attack on all

persons of Freethinking views. I objected to this as violating the

principle on which we had long agreed, namely, of Co-operative neutrality

in religion [52] and politics, as their introduction was the signal of

disputation which diverted the attention of members from the advancement

of Co-operation in life, trade, and labour. At the Leeds Congress I

maintained that the congress was like Parliament, where, as Canning said,

no question is introduced which cannot be discussed. If Church views were

imported into the societies, Heretics and Nonconformists, who were the

originators of the movement, would have the right of introducing their

tenets. Mr. Hughes was so indignant at my protest that he, being in the

chair, refused to call upon me to move a resolution officially assigned to

me upon another subject. At the meeting of the United Board for revising

motions to be brought before Congress, I gave notice that if the Church

question should be raised I should object to it, as it would then be in

order (should the introduction of theology be sanctioned) for an Atheist

(Agnostic was not a current word then) to propose the adoption of his

views, and an Atheist, as such, might be a president. Whereupon Mr. Vansittart Neale, our general secretary, declared with impassioned

vehemence that he hoped the day would never come when an Atheist would be

elected president. Yet when, some years later, I was appointed president

of the Carlisle Congress (1887)—though I was still considered entirely

deficient in proper theological convictions—Mr. Hughes and Mr. Neale, who

were both present, were most genial, and with their concurrence 100,000

copies of my address were printed—a distinction which befel no other

president.

In another instance I had to withstand Church ascendancy.

I was the earliest and foremost advocate of the neutrality of pious

opinion in Co-operation; when others who knew its value were

silent—afraid or unwilling to give pain to the Christian Socialists, whom

we all respected, and to whom we and friendly assistance. But integrity

of principle is higher than friendship. Some Northumbrian societies,

whose members were largely Nonconformists, were greatly indignant at the

attempt to give ascendancy to Church opinions, and volunteered to support

my protest against it. But when the day of protest came at the Leeds

Congress they all deserted me—not one raised a voice on my side; though

they saw me browbeaten in their interest. My argument was, that if we

assented to become a Church party we might come to have our proceedings

opened with a collect, or by prayer, to which it would be hypocrisy in

many to pretend to assent. At the following Derby Congress this came to

pass: Bishop Southwell, who opened the Industrial Exhibition, made a

prayer and members of the United Board knelt round him. I was the only one

who stood up, it being the only seemly form of protest there. This scene

was never afterwards repeated. Bishop Southwell was a devout, kindly, and

intellectually liberal prelate, but he did not know, or did not respect,

as other Bishops did, the neutrality of Congress.

For myself, I was always in favour of the individuality of the religious

conscience in its proper place. I love the picturesqueness of personal

conviction. It was I who first proposed that we should accept offers of

sermons on Congress Sunday by ministers of every denomination. Co-operators included members of all religious persuasions, and I was for

their opportunity of hearing favourite preachers apart from Co-operative

proceedings.

It is only necessary for the moral of these instances to pursue them. There is education in them and public suggestiveness which may justify the

continuance of the subject.

When the Co-operative News was begun in Manchester (1871), I wrote its

early leaders, and as its prospects were not hopeful, it was agreed that

the Social Economist, which I and Mr. E. O. Greening had established in

London in 1868, should cease in favour of the Co-operative News, as we

wished to see one paper, one interest, and one party. As the Manchester

office was too poor to purchase our journal, we agreed that it should be

paid for when the Manchester paper succeeded, and the price should be what

the cessation of the Social Economist should be thought to be worth to the

new paper. It was sixteen years before the fulfilment of their side of the

bargain. The award, if I remember rightly, was £15, but I know the period

was as long and the amount as small. The Co-operative News had then been

established many years. It was worth much more than £100 to the Manchester

paper to have a London rival out of the way. It was not an encouraging

transaction; and but for Mr. Neale, Abraham Greenwood and Mr. Crabtree it

would not have ended as it did. But the committee were workmen without

knowledge of literary matters. So I made no complaint, and worked with

them and for their paper all the same. It was a mistake to discontinue

the Social Economist, which had some powerful friends. Co-operation was

soon narrowed in Manchester. Co-operative workshops were excluded from

participation in profit. We should have kept Co-operation on a higher

level in London.

The Rochdale jubilee is the last instance I shall cite. In 1892 was

celebrated the jubilee of the Rochdale Society. I received no invitation

and no official notice. The handbook published by the society, in

commemoration of its fifty years' success, made no reference to me nor to

the services I had rendered the society. I had written its history, which

had been printed in America, and translated into the chief languages of

Europe—in Spain, in Hungary, several times in France and Italy. I had put

the name of the Pioneers into the mouth of the world, yet my name was

never mentioned by any one. Speaking on the part of the Rochdale Cooperators, the President of Jubilee Congress, who knew the facts of my

devotion to the reputation of Rochdale, was silent. Archdeacon Wilson was

the only one who showed me public regard. The local press said some

gracious things, but they were not Co-operators. I had spoken at the

graves of the men who had made the fortunes of the store, and had written

words of honour of all the political leaders of the town, and of those

best remembered in connection with the famous society, which I had

vindicated, without ceasing, during half a century.

In the earlier struggles of the Pioneers I had looked forward to the day

of their jubilee, when I should stand in their regard as I had done in

their day of need. Of course, this gave me a little concern to find

myself treated as one unknown to them. But in truth they had not forgotten

me, though they ignored me. The new generation of Co-operators had

abandoned, to Mr. Bright's regret, participation of profit with Labour,

the noblest aspiration of the Pioneers. I had addressed them in

remonstrance, in the language of Lord Byron, who was Lord of the Manor of

Rochdale:-

|

"You have the Rochdale store as yet,

Where has the Rochdale workshop gone?

Of two such lessons why forget

The nobler and the manlier one?" |

Saying this cost me their cordiality and their gratitude; but I cared for

the principle and for the future, and was consoled.

In every party, the men who made it great die, and leave no immediate

successors. But in time their example recreates them. But at the Jubilee of 1892, they had not re-appeared, and those who had memories

and gratitude were dead. I spoke over the grave of Cooper, of Smithies, of

Thomas Livesey—John Bright's schoolfellow—the great friend of the dead

Pioneers saying:—

|

"They are gone, the holy ones,

Who trod with me this lovely vale;

My old star-bright companions

Are silent, low and pale." [53] |

The question arises, does this kind of experience justify a person in

deserting his party?

The last incident and others preceding it are given as instances of

outrage or neglect, which in public life explain ignominious desertion of

principle. I have known men change sides in Parliament because the

Premier, who had defect of sight, passed them by in the lobby without

recognition. I have seen others desert a party, which they had brilliantly

served, because their personal ambition had not been recognised. Because

of this I have seen a man turn heels over head in the presence of

Parliament, and land himself in the laps of adversaries who had been

kicking him all his life.

If I did not do so, it was because I remembered that parties are like

persons, who at one time do mean things, but at other times generous

things.

Besides, a democratic party is continually changing in its component

members, and many come to act in the name of the movement who are ignorant

of its earlier history and of the obligation it may be under to those who

have served it in its struggling days. But whether affronts are

consciously given or not, they do not count where allegiance to a cause is

concerned. Ingratitude does not invalidate a true principle. When contrary

winds blow, a fairweather partisan tacks about, and will even sail into a

different sea where the breezes are more complacent. I remained the

friend of the cause alike in summer and winter, not because I was

insensible to vicissitudes, but because it was a simple duty to remain

true to a principle whose integrity was not and could not be affected by

the caprice, the meanness, the obliviousness, or the malignity of its

followers.

Such are some of the incidents—of which others of more public interest

may be given—of the nature of bygones which have instruction in them. They are not peculiar to any party. They occur continually in Parliament

and in the Church. I have seen persons who had rendered costly service of

long duration who, by some act of ingratitude on the part of the few, have

turned against the whole class, which shows that, consciously or

unconsciously, it was selfrecognition they sought, or most cared for,

rather than the service of the principle they had espoused.

There is no security for the permanence of public effort, save in the

clear conviction of its intrinsic rightfulness and conduciveness to the

public good. The rest must be left to time and posterity. True, the debt

is sometimes paid after the creditor is dead. But if reparation never

comes to the living, unknown persons whose condition needs betterment

receive it, and that is the proud and consoling thought of those

who—unrequited—effected it. The wholesome policy of persistence is

expressed in the noble maxim of Helvetius to which John Morley has given

new currency: "Love men, but do not expect too much from them."

Fewer persons would fall into despair if their anticipations were, like a

commercial company; "limited." Many men expect in others perfection, who

make no conspicuous contribution themselves to the sum of that excellent

attribute.

|

"Giving too little and asking too much

Is not alone a fault of the Dutch." |

I do not disguise that standing by Rightness is an onerous duty. It is as

much a merit as it is a distinction to have been, at any time, in the

employ of Truth. But Truth, though an illustrious, is an exacting

mistress, and that is why so many people who enter her service soon give

notice to leave.

[With respect to this chapter, Mr. Ludlow wrote supplying some particulars

regarding the Christian Socialists, to which it is due to him that equal

publicity be given. He states "that the first Council of Promoters

included two members, neither of whom professed to be a Christian; that

the first secretary of the Society for Promoting Working Men's

Associations was not one, during the whole of his faithful service (he

became one twenty years later), and that his successors were, at the time

we took them on, one an Agnostic, the other a strong Congregationalist." This is the first time these facts have been made known. But none of the

persons thus described had anything to do with the production of the

Handbook referred to and discussed at the Leeds Congress of 1881. Quite

apart from the theological tendencies of the "Christian Socialists," the

Co-operative movement has been indebted to them for organisation and

invaluable counsel, as I have never ceased to say. They were all for the

participation of profits in workshops, which is the essential part of

higher Co-operation. There was always light in their speeches, and it was

the light of principle. In this respect Mr. Ludlow was the first, as he is

the last to display it, as he alone survives that distinguished band. Of

Mr. Edward Vansittart Neale I have unmeasured admiration and regard. To

use the fine saying of

Abd-el-Kader, "Benefits conferred are golden fetters which bind men of

noble mind to the giver." This is the lasting sentiment of the

most

experienced Co-operators towards the Christian Socialists.]

CHAPTER XXXII.

STORY OF THE LAMBETH PALACE GROUNDS

SEED sown upon the waters, we are told, may bring

forth fruit after many days. This chapter tells the story of seed sown on

very stony soil, which brought forth fruit twenty-five years later.

In 1878, Mr. George Anderson, an eminent consulting gas engineer, in whom

business had not abated human sympathy, passed every morning on his way to

his chambers in Westminster, by the Lambeth Palace grounds. He was struck

by the contrast of the spacious and idle acres adjoining the Palace and

the narrow, dismal streets where poor children peered in corners and

alleys. The sheep in the Palace grounds were fat and florid, and the

children in the street were lean and pallid. The smoke from works around

dyed dark the fleece of the sheep.

Mr. Anderson thought how much happier a sight it would be to see the

children take the place of the sheep, and asked me if something could not

be done.

The difficulty of rescuing or of alienating nine acres of

land from the Church, so skilled in holding, did not seem a hopeful

undertaking, while the resentment of good vicars and expectant curates

might surely be counted upon. Nevertheless the attempt was worth

making.

Before long I spent portions of some days in exploring the

Palace grounds, and interviewing persons who had evidence to give, or

interest to use, on behalf of a change which seemed so desirable.

Eventually I brought the matter before a meeting I knew to be

interested in ethical improvement, and read to them the draft of a

memorial that I thought ought to be sent to the Archbishop at Lambeth

Palace. Persons in stations low and high alike, often suffer wrong

to exist which they might arrest, because they have not seen it to be

wrong or have not been told that it is so. Blame of any one could

not be justly expressed who had not personal knowledge of an evil

complained of. Therefore I urged that we should give the Archbishop

information which we thought justified his action, and I was authorised to

send to him the memorial I had read.

I wrote myself to his Grace, stating that I could testify as

to the social facts detailed the memorial I enclosed, which was as

follows:—

"MAY IT PLEASE YOUR GRACE,—We, the evening congregation assembled in

South Place Chapel, Finsbury—some assenting and some dissenting from the

tenets represented by your Grace—represented as worthily as by any one

who has occupied your high station, and with greater fairness to those who

stand outside the Church than is shown by many prelates—we pray your

Grace to give heed to a secular plea on behalf of certain little

neighbours of yours whom, amid the pressure of spiritual duties, your

Grace may have overlooked.

"Crouching under the very walls of Lambeth Palace, where your

Grace has the pleasant responsibility of illustrating the opulence and

paternal sympathy of the legal Church of the land, lie streets as dismal,

cheerless, and discreditable as any that God in His wrath ever permitted

to remain unconsumed. In the houses are polluted air, squalor, dirt

and pale-faced children. The only green thing upon which their

feverish eyes could look is enclosed in your Grace's Palace Park, and shut

out from their sight by dead Walls. What we pray is that your Grace,

in mercy and humanity, will substitute for those Penal walls some pervious

palisades through which children may behold the refreshing paradise of

Nature, though they may never enter therein. In this ever-crowding

metropolis, where field and tree belong to the extinct sights of a happier

age, children are born and die without ever knowing their soothing charm,

and hunger and thirst for a green thing to look upon—as sojourners in a

desert do for the sight of shrub or water. No prayer your Grace

could offer to heaven would be so welcome in its kindly courts, as the

prayer of gladness and gratitude which would go up with the screams of

change and joy from the pallid little ones, breathing the fresh air from

the green meadows, which only a few more fortunate sheep now enjoy.

"Might we pray that the gates should be open, and that the

children themselves should be free to enter the meadows? Even the

Temple Gardens of the City are open to little friendless people.

They who give this gracious permission are hard-souled lawyers, usually

regarded as representing the rigid, exacting, and unsympathetic side of

human life—yet they show such noble tenderness to the little miserables

who crawl round the Temple pavement, that they grant entrance to their

splendid gardens; and half-clad cellar urchins from the purlieus of Drury

Lane and Clare Market romp with their ragged sisters on the glorious

grass, in the sight and scent of beauteous flowers. If lawyers do this,

may we not ask it of one who is appointed to represent what we are told is

the kindliness and tenderness of Christianity, and whose Master said,

'Suffer little children to come unto Me, and forbid them not, for of such

is the kingdom of heaven'? We ask not that they should personally

approach your Grace, but that the children of your desolate neighbourhood

should be allowed to disport in the vacant meadows of the Palace—that

their souls may acquire some scent of Nature which their lives may never

know.

"Let your Grace take a walk down 'Royal Street,' which flanks

your Palace grounds, and see whether houses so pestilential ever stood in

a street of so dainty a name? Go into the houses (as the writer of

this memorial has) and see how a blank wall has been kept up so that no

occupant of the rooms may look on grass or tree, and the window which

admits light and air has been turned, by order of a former archbishop, the

opposite way upon an outlook as wretched as the lot of the inhabitants.

For forty years many inmates have lived and slept by the side of your

Grace's park, without ever being allowed a glimpse of it. You may

have no power to cancel such social outrage—but your Grace may condone it

by kindly and considerately according the use of the meadows to the poor

children—doomed to burrow in these close, unwholesome tenements at your

doors.

"No one accuses your Grace of being wanting in personal

kindliness. It must be that no one has called your attention to the

unregarded misery under the shadow of your Palace. Should Your Grace

visit the forlorn streets and sickly homes around you, and hear the

despairing words o f the mothers when asked 'whether they would not be

grateful could their children have a daily run in the great Archbishop's

meadows?' there would not be wanting a plea from the gentle heart of the

Lady of the Palace on behalf of these hapless children of these poor

mothers.

"Disregard not our appeal, we pray, because ours are

unlicensed voices. Humanity is of every creed, and it will not

detract from the glory of the Church that gratitude and praise should

proceed from unaccustomed tongues.

"Signed on behalf of the Assembly, with deference and

respect.

"GEORGE JACOB

HOLYOAKE.

"Newcastle

Chambers, Temple Bar,

"November 21, 1878."

Within two days I had the pleasure to receive a reply from

the Archbishop.

|

|

|

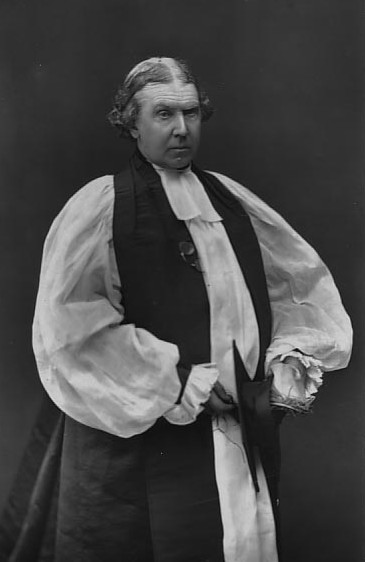

Archibald Campbell Tait

(1811-82)

Archbishop of Canterbury, 1868-82. |

"PHILPSTOUN HOUSE,

"November 23, 1878.

"SIR,—You may feel confident that the subject of the

memorial which you have forwarded to me with your letter of the 21st will

receive my attentive consideration. The condition of the inhabitants

of the poor streets in Lambeth has often given me anxiety. My

daughters and Mrs. Tait are well acquainted with many of the houses which

you describe, and, so far as my other duties have allowed, I have taken

opportunities of visiting some of the inmates of such houses personally.

I should esteem it a great privilege if I were able to assist in maturing

any scheme for improving the dwellings of the poor families to which your

memorial alludes. Respecting the use of the open ground which

surrounds Lambeth Palace, I have, in common with my predecessors, had the

subject often under consideration. The plan which has been adopted

and which has appeared on the whole the best for the interests of the

neighbourhood, has been that now pursued for many years. The ground

is freely given for cricket and football to as many schools and clubs as

it is capable of containing, and, on application, liberty of entrance is

accorded to children and others. Many school treats are also held in

the grounds, and they are from time to time used for volunteer corps to

exercise in. We have always been afraid that a more public opening

of the grounds would interfere with the useful purposes to which they are

at present turned for the benefit of the neighbourhood, and that,

considering the somewhat limited extent of the space, no advantage could

be secured by throwing it entirely open, which would at all compensate for

the loss of the advantages at present enjoyed. I shall give the

matter serious consideration, consulting with those best qualified from

local experience to judge what is best for the neighbourhood, but my

present impression is that more good is, on the whole, done by the

arrangements now adopted, than by any other which I could devise.

"I have the honour to be, Sir,

"Your obedient humble servant,

"A. C. CANTUAR.

"To Mr. George Jacob Holyoake."

This correspondence I sent to the Daily News, always open to questions of

interest to the people, and it received notice in various papers. The

Liverpool Daily Mail gave an effective summary of the memorial,

saying:—

"Of all strange people in the world, Mr. G. J. Holyoake and the Archbishop

of Canterbury have been in correspondence—and not in unfriendly

correspondence either. Mr. Holyoake, on behalf of himself and some friends

like-minded, ventured to draw the Archbishop's attention to the fact that

just opposite Lambeth Palace was a nest of very poor and squalid

dwellings, in which many families were crowded together, without any

regard for either decency or sanitary law. The only chance of looking upon

anything green that the children of these poor people could have would be

in the

grounds that surround the Primate's dwelling, and these were absolutely

shut off from their view by a high dead wall. In some cases a former

Archbishop had actually ordered the windows of these miserable houses to

be blocked up, and opened in another direction, in order, we suppose, that

the Archiepiscopal eyes might not be offended by the sight of such

unpleasant neighbours." The writer ended by expressing the hope that if

the Archbishop could not open the grounds he might substitute "pervious

palisades" for the stone walls impervious to the curious and wistful eyes

of children." For reasons which will appear, the subject slumbered for four

years, when I addressed the following letter to the editors of the

Telegraph and the Times, which appeared December 20, 1882:—

"SIR,—On returning to England I read an announcement that the Lambeth

Vestry had resolved to send a memorial to the Queen praying that the nine

acres of field, now devoted to sheep, adjoining the Archbishop of

Canterbury's Palace garden, may be appropriated to public recreation

in that crowded and verdureless parish. Four years ago I sent a memorial

upon this subject to the

late Archbishop. It set forth that the parish was so densely populated

that it would be an act of mercy to throw open the sheep fields to the

poor children of the neighbourhood. It expressed the hope that Mrs. Tait,

whose compassionate nature

was known to the people, would plead for these little ones, who lived and

died at her very door, as it were, seeing no green thing during all their

wretched days. I visited poor women in the street next to the fields who

brought fever-stricken children to the door wrapped in shawls. Their

mothers told me how glad they should be were the gates open, that the

little ones, whose only recreation ground was the gutter, could enter at

will. The memorial—if I remember accurately, for I cannot refer to it as

I write—stated that the houses which, as built, overlooked the fields,

had had the windows bricked in by order of a former Archbishop, because

they overlooked the garden. I was taken to the rooms and found that the

view was closed up. The trees of the garden have well grown now, and a

telescope could not reveal walkers therein. The late Archbishop sent me a

kindly reply, but it did not answer my question, which was that, if his

Grace could not consent to open the gates to his humble friends, we prayed

that he, whose Master (in words of tenderness which had moved the hearts

of men during nineteen centuries) had said, 'Suffer little children to

come unto Me,' would at least substitute palisades for the dead walls

which hid the green fields so that no little eyes could see the daisies in

the spring. His Grace's reply was in substance the same as Dr. Randall

Davidson's, which appeared in the Times on Monday, who tells the public that rifle

corps and cricketers are admitted to the fields and that 'arrangements

are made for "treats" for infant and other schools' (whether of all

denominations is not stated). How can poor mothers and sickly children get

within these 'arrangements'? Cricketers are not helpless, rifle corps do

not die for want of drill-grounds, as children in fever-dens do for want

of the refreshment of verdure and pure air. To open the gates is the only

generous and fitting thing to do, as the lawyers have who admit the

outcasts of Drury and the adjacent lanes to the flowers of the Temple

Gardens. Dr. Davidson says that the advice of those 'best qualified from

local experience to judge' is that 'no gain could be secured by throwing

the fields entirely open.' Let the opinion be asked of workmen in the

Lambeth factories and that of their wives. These are the 'best qualified

local judges,' whose verdict would be instructive. Mrs. Tait's illness and

death followed soon after the memorial in question was sent in, and I

thought it not the time to press his Grace further when stricken with that

calamity. All honour to the Lambeth Vestry, which proposes to pray Her

Majesty to cause, if in her power, these vacant fields to be consigned to

the Board of Works, who will give some gleam of a green paradise to the

poor little ones of Lambeth. The vestry does well to appeal to the Queen,

from whose kindly heart a thousand acts of sympathy have emanated. She

has opened many portals, but none through which happier or more grateful

groups will pass than through the garden gates of Lambeth Palace."

Immediately a letter appeared in the Times from the Rev. T. B.

Robertson, expressed as follows:—

"SIR,—Mr. Holyoake may be glad to hear that 'Lambeth Green' is open to

schools of all denominations to hold their festivals in. I should think

that no school was ever refused the use unless the field was previously

engaged. The present method of utilising the field—viz., opening it to a

large but limited number of persons (by ticket) seems about the best that

could be devised. Mr. HoIyoake asks how poor mothers and sickly children

are to gain entrance. It is well known in the neighbourhood that tickets

of admission are issued annually. The days for distribution are advertised

on the gates some time previous, when those desirous of using the grounds

can attend, and the tickets are issued till exhausted. No sick person has

any difficulty in getting admission. I do not know the number of tickets

issued, but I have seen when cricket clubs were unable to find a place to

pitch their stumps. If the grounds are open to the public without

limitation, it seems that the only way it could be done would be by laying

it out in gardens and gravelled walks, with the usual park seats; but

there is hardly occasion for such a place since the formation of the

Thames Embankment, a long strip of which runs immediately in front of the

Palace well provided with seats. It is evident that if the grounds were

open to the public in general, the space being small—about seven

acres—the cricketers and other clubs would have to give up their sports,

and Lambeth schools and societies would be deprived of their only

meeting-place for summer gatherings.

"Yours obediently,

"T. B. ROBERTSON,

"Curate of St. Mary, Lambeth.

"December 22."

The comment of the Times upon this letter made it necessary

to address a further communication to the editor. This comment occurred in

a leader, which, referring to a letter of the Lambeth Curate, says: "Mr.

Holyoake, in a letter which we published on Wednesday, asked with some

vehemence, what was the value of permission accorded to cricketers and

schools, to the poor children of Lambeth; but Mr. Robertson, the Curate

of St. Mary's, Lambeth, answers this morning, that no Poor or sick person

has any difficulty in obtaining admission for purposes of recreation and

health, and shows that 'Lambeth Green,' as it is called, is in fact

available to a large class of the neighbouring inhabitants. There is

certainly force in

Mr. Robertson's argument, that an unlimited use would defeat its own

object, which is presumably to preserve the grounds as a playground. The

large surrounding population would soon destroy the sylvan and park-like

character of the place, and necessitate its laying out in the style of an

ornamental pleasure garden, with formal walks, and turf only to be kept

green by fencing."

This is the old defence of exclusive enjoyment of parks and pleasure

grounds, as the people, if admitted to them, would destroy them—which

they do not. Why should they destroy what they value?

My reply to the Times appeared December 28, 1882:—

"SIR,—It is the weight that you attach to the letter of the Curate of St.

Mary, Lambeth, which appeared in the Times of Saturday, which makes it

important. When I have viewed the Lambeth Palace from the railway which

overlooks it and seen how completely the sheep fields are separate and

apart from the Archbishop's garden, it has seemed a pity that the poor

little children of Lambeth should not have the freedom and privilege of

those sheep. No humane person could look into the houses of the crowded

and cheerless streets which lie near the Palace walls without wishing to

take the children by the hand

into the Palace fields at once. Does the Rev. Mr. Robertson not understand

the difference between a ticket gate and an open gate? How are poor, busy women to watch the

gates to find out when the annual tickets of admission are given? And

what is the chance of those families who arrive after the number issued is exhausted? If all the persons who need admissions

can have them, the

gates might as well be thrown open. Of course, the nine acres would not

hold all the parish; but

all the parish would not go at once. No statement has been made which

shows that the grounds have been occupied by tickets of admission more

than forty days in the year, whereas there are 365 days when little people

might go in. To them one hour in that green paradise would be more than a

week jostled by passengers on the Embankment watching a stone wall, for

the little people could not well overlook it. But if they could, can the

Curate of St. Mary really think this limited recreation a sufficient

substitute for quiet fields and flowers? The Board of Works, if the

grounds come into their hands, may be trusted to give school treats a

chance as well as local little children.

"No one who has seen the crowds of ragged, dreary, pale-faced boys and

girls rushing to the fields and flowers at Temple Gardens when the lawyers

graciously open the gates to them and watched them pour out at evening

through the Temple Gates into Fleet Street, leaping, laughing, and

refreshed, could help thinking that it would be a gladsome sight sight to

see such groups issue from the Lambeth Palace gates. I never thought when

sending the memorial to the Archbishop that the fields should be divested

from the see or sold away from it. I believed that the late Archbishop

would, as the new Archbishop may, by an act of grace accord his little

neighbours free admission, or at least exchange the dead walls for

palisades, so that children playing around may vary the stones of the

Embankment for a sight of sheep and grass through

the bars. The late Canon Kingsley asked me to visit him when he came into

residence at Westminster. My intention was to ask him and the late Dean,

whom I had the honour to know, to judge themselves whether the matter now

in question was not practicable, and then to speak to the Archbishop about

it. But death carried them both away one after the other before this

opportunity could occur. My belief remains unchanged that the late

Archbishop would have done what is now asked had time and the state of his

health permitted him to attend to the matter himself. It would have been

but an extension of the unselfish and kindly uses to which he had long

permitted the grounds to be put."

From several letters I received at the time, I quote

one dated Christmas Eve, 1882:—

"Honour and thanks to you, Mr. Holyoake, for our recent and former letters

respecting Lambeth Palace field. Very much more good could be got out of

it than as a place for cricketing on half-holidays and occasional

school-treats, and for desolation at other times except as regards an

approved few.

"There is no recreation ground in London that I look upon with so much

satisfaction as a triangular inclosure of plain grass by Kennington

Church, enjoyed commonly by the dirtiest and poorest children."

But a letter of a very different character appeared in the Standard,

December 20 1882, entitled, "The Lambeth Palace Garden":—

"SIR,—No right-minded

person can fail to be deeply impressed by Mr. Holyoake's touching letter

in your impression of to-day. Its sentiments are so very beautiful

and its principles so exactly popular, and in such perfect accordance with

the blessed Liberal maxim—'What is yours is mine and what is mine is my

own,' that I myself am overcome with delight at their enunciation.

The

pleasure of being perfectly free and easy with other people's property,

evidently becoming so sincere and abounding, and the simple manner in

which such liberality can be now readily practised without any personal

self-denial or inconvenience, makes the principle in action perfectly

commendable, and one to be duly applied and most carefully expanded.

"With the latter view, I venture to point out that there is a very

excellent library of books at Lambeth Palace, which, comparatively

speaking, very few people take down or read. Do not, however, think me

selfishly covetous or hankering after my neighbour's property if I venture

to point out that there exist more than twenty clergymen in Lambeth, to

whom a share or division of these scarcely used volumes would be a great

boon. If the pictures, furniture, and cellars of wine could, at the same

time, be benevolently divided, I should have no objection to receiving a

share of the same under such philanthropic 're-arrangement.'—I am, sir,

your obedient servant,

"A LAMBETH

PARSON.

"Lambeth, December 20."

My reply to this letter appeared in the Standard, December 22,

1882:—

"SIR, —This morning I received a letter from a clergyman, who gives his

name and address, and who knows Lambeth well, thanking me for the letter

which I had addressed to you, as he takes great interest in the welfare of

the little ones in the crowded homes around the Palace. Lest, however, I

should be elated by such an unexpected, though welcome, concurrence of

opinion, the same post brought me a letter to the same purport of that

signed 'A Lambeth Parson,' which appeared in the Standard yesterday. The

letter which you printed assumes that the sheep fields of the Palace are

private property, and that I propose to steal them in the name of

humanity. Permit me to say that I have as much detestation as the Lambeth

Parson can have for that sympathy for the people which has plunder for its

motive.

"The memorial I sent to his Grace the late Archbishop asked him to give

his permission for little ones to enter his grounds. We never proposed to

take permission, nor assumed any right to pass the gates. There never was

a doubt in my mind, that had his Grace opportunity of looking into the

matter for himself, he would have granted the request, for his kindness of

heart we all knew. That he gave the use of the fields to what he thought

equally useful purposes showed how unselfishly he used the grounds. If

the question is raised as to private property, I would do what I could to

promote the purchase of it (if it can rightly be sold) by a penny

subscription from the parents of the poor children and others who would

chiefly benefit by it. It would be an evil day if working people could

consent that their little ones should have enjoyment at the price of

theft.—I am, sir, your obedient servant,

"GEORGE

JACOB HOLYOAKE.

"22 Essex Street, W.C., December 21."

Meanwhile an important public body had taken up the question. "The

Metropolitan Public Garden, Boulevard, and Playground Association, had,

through its officers, Lord Brabazon, Mr. Ernest Hart, Mr. J. Tennant, and

the Rev. Sidney Vatcher, addressed the following letter to the Prime

Minister:—

"SIR,—The

undersigned members of the Metropolitan Public Garden, Boulevard, and

Playground Association' desire to draw your attention to an article

enclosed which recently appeared in a London daily paper, and to request

that you will bring the needs of Lambeth district, as regards open spaces,

to the notice of the future Primate, in the hope that his Grace may take

into consideration the suggestions contained in the article, and with the

co-operation of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and the Metropolitan

Board of Works, take such steps as may seem to him most advisable for the

purpose of securing in perpetuity to the poor and crowded population of

Lambeth the use and enjoyment of the open space around Lambeth Palace.—We

have the honour to be, sir, your most obedient and humble servants,

"BRABAZON, Chairman."

Mr. Gladstone willingly gave attention to the subject, and sent the

following reply:—

10, DOWNING

STREET, WHITEHALL,

December 21, 1882.

MY LORD,—I am directed by Mr. Gladstone to acknowledge the receipt of the

letter which was signed by your lordship and other members of the

Metropolitan Public Garden, etc., Association in favour of securing for

the use of the population of the neighbourhood the grounds at present

attached to Lambeth Palace. I have to inform your lordship that Mr.

Gladstone has already been in communication with the vestry of Lambeth on

this subject, and as it appears to be one of metropolitan improvement it

is not a matter in which Mr. Gladstone can take the initiative. He will,

however, make known your views to the prelate designated to succeed to the

Archbishopric, and should the Metropolitan Board of Works intervene Mr.

Gladstone will be happy to consider the matter further.—I am, my Lord,

your obedient servant,

" HORACE

SEYMOUR.

"The Lord Brabazon."

Next Colonel Sir J. M'Garel Hogg, M.P., Chairman of the Metropolitan Board

of Works, had the matter before him. It was stated that the use of the

nine acres of ground (of which a plan was presented) depended upon the

permission of the Archbishop. The Lambeth Vestry had sent a memorial to

the Queen and the Government saying that the pasture and recreation acres

might be severed from the Archbishop's residence.

The following is the reply received from Mr. Gladstone:—

"10, DOWNING STREET, WHITEHALL,

December 19th,

"SIR,—Mr. Gladstone has had the honour to receive the communication which

you have made to him on behalf of the vestry of the parish of Lambeth on

the subject of acquiring the grounds of Lambeth Palace as a place of

public recreation. In reply I am directed to say that as far as he is able

to understand this important matter it seems to be a case of metropolitan

improvement, and if, as he supposes, that is the case, the proper course

for the vestry to take would be to bring the case before the Metropolitan

Board of Works for their consideration. In this view Mr. Gladstone is not

aware that Her Majesty's Government could undertake to interfere, but he

will make known this correspondence to the person who may be designated to

succeed the Archbishop of Canterbury, and he will further consider the

matter should the Metropolitan Board intervene. Mr. Gladstone would have

been glad if the vestry had supplied him with the particulars of the case,

in regard to which he has only a very general knowledge.—I am, sir, your

obedient servant,

" E. W. HAMILTON

"The Vestry Clerk of Lambeth."

Mr. Hill gave notice of the following motion:—

"That an instruction be given to the Prime Minister that if the proper

authorities are willing to hand over the Lambeth Palace grounds for the

free use of the public, this Board will accept the charge and preserve the

grounds as a portion of the open spaces."

Then came a hopeless and defensive letter, before referred to, addressed

both to the Standard, Telegraph, and the Times:—

SIR,—Some of the statements (including a correspondence with the Prime

Minister) which have, during the last few days, appeared in the newspapers

with reference to Lambeth Palace grounds, would, I think, lead those who

are unacquainted with the circumstances to suppose that these grounds have

been hitherto altogether closed to the public, and reserved for the sole

use of the Archbishop and his household. Will you, therefore, to prevent

misapprehension, kindly allow me to state the facts of the case?

"For many years past the Archbishop of Canterbury endeavoured, in what

seemed to him the best way, to make the grounds in question available,

under certain restrictions, to the general public. During the summer

months twenty-eight cricket clubs, some from the Lambeth parishes and some

from other parts of London, have received permission to play cricket in

the field, and similar arrangements have been made for football in the

winter, though necessarily upon a smaller scale. The whole available

ground has been carefully

allotted for the different hours of each day. On certain fixed occasions

the field is used for rifle corps' drill and exercises, and throughout the

summer, arrangements are constantly made for 'treats' for infant and

other schools unable to go out of London. Tickets giving admission to the

field at all hours have been issued for some years past, in very large

numbers, to the sick, aged, and poor of the surrounding streets ; and the

whole grounds, including the private garden, have been opened without

restriction to the nurses and others of St. Thomas's Hospital.

"His Grace frequently consulted those best qualified from local experience

to judge what is for the advantage of the neighbourhood, and invariably

found their opinion to coincide with his own—namely, that a more public

opening of the ground would interfere with the useful purposes to which it

is at present turned for the benefit of the neighbourhood, and that,

considering the limited space, no gain could be secured by throwing it

entirely open which would at all compensate for the inevitable loss of the

advantages at present enjoyed.—I am, sir, your obedient servant,

"RANDALL

T. DAVIDSON.

"Lambeth Palace, December 16."

On January 6, 1883, I wrote to the Daily News, saying:—

|

|

|

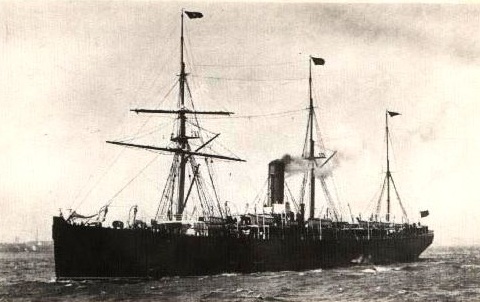

Edward White Benson

(1829-96)

Archbishop of Canterbury, 1883-96. |

"SIR,—Your columns have recorded the steps taken by the Lambeth

Vestry and by Lord BRABAZON (on the part of the Open Space Society, for

which he acts) with respect to the use of the

pasture acres connected with the Palace grounds of Lambeth. I have been

asked by a clergyman, for whose judgment I have great respect, to write

some letter which shall make it plain to the public that it is not the

gardens of the Palace for the use of which any one has asked, but for the

nine acres of fields outside the gardens, as a small recreation ground

which shall be open to the children of Lambeth, who are numerous there,

and much in need of some pleasant change of that scarce and pleasant kind. No one has dined at the Lambeth Palace, or been otherwise a visitor there,

without valuing the gardens which surround it and which are necessary to

an episcopal residence in London. No one wishes to interfere with or

curtail the garden grounds. I thought the public understood this. I shall

therefore be obliged if you can insert this explanation in your columns. Much better than anything I could say upon the subject are the words which

occur in the Family Churchman of December 27th, which gives the portraits

of the new Archbishop, Dr. Benson, and the late Bishop of Llandaff. The

editor says that 'every one knows the Archbishops of Canterbury have a

splendid country seat at Addington, within easy driving distance of

London. Within the same distance there are few parks so beautiful as Addington Palace, whilst, unlike some

parks in other parts of the country, it is jealously closed against the

public. The Palace park is remarkable for its romantic dells, filled with

noble trees and an undergrowth of rhododendrons. There are, moreover,

within the park, heights which command fine views of the surrounding

country. It is thought, perhaps not unjustly, that the new Archbishop

might well be content with this country place, and, whilst retaining the

gardens at Lambeth Palace, might with graceful content see conceded to the

poor, whose houses throng the neighbourhood, the nine acres of pasture

land.' This is very distinct and even generous testimony on the part of

the Family Churchman to the seemliness and legitimacy—of the plea put

forward on the part of the little people of Lambeth.—Very faithfully

yours,

"GEORGE

JACOB HOLYOAKE.

" 22, Essex Street, W.C."

News of the Palace grounds agitation reached as far as Mentone, and Mr. R.

Ffrench Blake, who was residing at the Hotel Splendide, sent an

interesting letter to the Times—historical, defensive, and suggestive.

He wrote on January 3, 1883, saying:—

"SIR,—Attention having recently been drawn to the Lambeth Palace grounds

and the use which the late Primate made of them for the recreation of the

masses, it may be interesting, especially at this juncture, to place on

record what were his views with regard to those historic parts of the

buildings of the

Palace itself which are not actually used as the residence of the

Archbishops. These chiefly consist of what is known as the Lollards'

Tower, and the noble Gate Tower, called after its founder, Archbishop

Moreton. The former of these has recently been put into repair, and rooms

in it were granted to the late Bishop of Lichfield and his brother, by

virtue of their connection with the Palace library."

Mr. Blake then adverts to the affair of the grounds. He says:—

"Nor can I suppose that any well-informed member of the vestry could

imagine that it is in the lawful power of a Prime Minister, or even of

Parliament, to alienate, without consent, any portion

of the Church's inheritance. It maybe a somewhat high standard of right,

which is referred to in the sacred writings, to 'pay for the things which

we never took,' but in no standard of right whatsoever can the motto find

place to 'take the things for which we never pay.' Although the Archbishop

may have deemed that he turned to the very best account the ground in

question, for the purposes of enjoyment and health to the surrounding

population, he was far too wise and too charitable to disregard, so far as

he deemed he had the power, any petition or request which might, if

granted, add to the pleasure and happiness of others, and if it had been

made clear to him as his duty, and an offer to that effect had been made

to him by the Metropolitan Board of Works or others, I am satisfied he

would have consented, not to the alienation of Church property, but to the

sale of the field for a people's park, and the application of the value of

the ground to mission purposes for South London, and such a scheme I

happen to know was at one time discussed by some of those most intimately

connected with him."

Afterwards, January 13, 1883, the Pall Mall Gazette remarked that "it is

not a happy omen that the consent of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners is

required before the well-fed donkey who disports himself in the Palace

grounds can be joined by the ill-fed, ragged urchins who now have no

playground but the streets." The Daily News rendered further aid in a

leader. Then a report was made that the condition of the streets, "to

which, in his correspondence with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Mr.

Holyoake had called attention, had been illustrated by the fall of several

miserable tenements, in which a woman and several children were fatally

buried in the ruins." The writer says there is "no hope that the unkindly

exclusiveness of 'Cantuar ' will be broken down."

So the matter rested for nearly twenty years before the happy news came

that the London County Council had come into possession of the

ecclesiastical fields, and converted them into a holy park, where

pale-faced mothers and sickly children may stroll or disport themselves at

will evermore. All honour to the later agents of this merciful change. There is an open gleam of Nature now in the doleful district. Sir Hudibras

exclaims:—

"What perils do environ

Him who meddles with cold iron." |

Not less so if the meddlement be with ecclesiastical iron and the contest

lasts a longer time.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

SOCIAL WONDERS ACROSS THE WATER

BEING several times in France, twice in

America and Canada, thrice in Italy and as many times in Holland, under

circumstances which brought me into relation with representative people,

enabled me to become acquainted with the ways of persons of other

countries than my own. There I met great orators, poets, statesmen,

philosophers, and great preachers of whom I had read--but whom to know was

a greater inspiration. Thus I learned the art of not being

surprised, and of regarding strangeness as a curiosity, not an offence

awakening resentment as something unpardonable, or at least, an

impropriety the traveller is bound to reprehend, as Mrs. Trollope and her

successors have done on American peculiarities. On the Continent I

found incidents to wonder at, but I confine myself in this chapter to

America and Canada, countries we are accustomed to designate as "Across

the Water," as the United States and the Dominion which have imperishable

interest to all of the British race.

Notwithstanding the thousands of persons who now make sea

journeys for the first time, I found, when it came to my turn, there was

no book--nor is there now--on the art of being a sea passenger. I

could find no teaching Handbook of the Ocean--what to expect under

entirely new conditions, and what to do when they come, so as to extract

out of a voyage the pleasure in it and increase the discomforts which

occur in wave-life. One of the pleasures is--there is no dust at

sea.

On my visit to America in 1879, I, at the request of Mr.

Hodgson Pratt, undertook to inquire what were the prospects of emigrants

to that country and Canada, which cost me labour and expense. What I

found wanting, and did not exist, and which does not exist still, was an

emigrant guide book informing him of the conditions of industry in

different States, the rules of health necessary to be observed in

different climates, and the vicissitudes to which health is liable.

The book wanted is one on an epitome plan of the People's Blue Books,

issued by Lord Clarendon on my suggestion, as he stated in them.

When I was at Washington, Mr. Evarts, the Secretary of State,

gave me a book, published by local authorities at Washington, with maps of

every department of the city, marking the portion where special diseases

prevailed. London has no such book yet. Similar information

concerning every State and territory in America existed in official

reports. But I found that neither the Government of Washington nor

Ottawa would take the responsibility of giving emigrants this information

in a public and portable form, as land agents would be in revolt at the

preferential choice emigrants would then have before them. It was

continually denied that such information existed. Senators in their

turn said so. Possibly they did not know, but Mr. Henry Villard, a

son-in-law of Lloyd Garrison, told me that when he was secretary of the

Social Science Association he began the kind of book I sought, and that

its issue was discouraged.

On my second visit to America in 1882, I had introductions to

the President of the United States and to Lord Lorne, the Governor of

Canada, from his father, the Duke of Argyll, with a view of obtaining the

publication of a protecting guide book such as I have described, under its

authority. When I first mentioned this in New York (1879) the editor

of the Star (an Irishman) wrote friendly and applauding leaders

upon my project. On my second visit, in 1882, this friendly editor

(having seen in the papers that Mr. Gladstone approved of my quest) wrote

furious leaders against it. On asking him the reason of the change

of view, he said, "Mr. Holyoake, were Mr. Gladstone and his Cabinet in

this room, and I could open a trap-door under their feet and let them all

fall into hell, I would do it," using words still more venomous.

Then I realised the fatuity of the anti-Irish policy which drives the

ablest Irishmen into exile and maintains a body of unappeasable enemies of

England wherever they go. Then I saw what crazy statesmanship it was

in the English to deny self-government to the Irish people, and spend ten

millions a year to prevent them taking care of themselves.

The Irish learned to think better of Mr. Gladstone some years

later. One night when he was sitting alone in the House of Commons

writing his usual letter to the Queen, after debates were over, he was

startled by a ringing cheer that filled the chamber, when looking up he

found the Irish members, who had returned to express their gratitude to

him. Surely no nation ever proclaimed its obligation in so romantic

a way. The tenderest prayer put up in my time was that of W. D.

Sullivan:--

"God be good to Gladdy,

Says Sandy, John and Paddy,

For he is a noble laddy,

A grand old chiel is he." |

I take pride in the thought that I was the first person who

lectured upon "English Co-operation" in Montreal and Boston. It was with

pride I spoke in Stacey Hall in Boston, from the desk at which Lloyd

Garrison was once speaking, when he was seized by a slave-owning mob with

intent to hang him. As I spoke I could look into the stairway on my right,

down which he was dragged.

The interviewers, the terror of most "strangers," were welcome to me.

The engraving in Frank Leslie's paper reproduced in "Among the Americans,"

representing the interview with me in the Hoffman House, was probably the

first picture of that process published in England (1881). I advocated the

cultivation of the art in Great Britain, which, though prevalent in

America, was still in a crude state there. The questions put to me were

poor, abrupt, containing no adequate suggestion of the information sought. The interviewer should have some conception of the knowledge of the person

questioned,

and skill in reporting his answers. Some whom I met put down the very

opposite of what was said to them. The only protection against such perverters, when they came again, was to say the contrary to what I meant,

when their rendering would be what

I wished it to be. Some interviewers put into your

mouth what they desired you to say. Against them

there is no remedy save avoidance. On the whole,

I found interviewers a great advantage. I had certain ideas to make known

and information to ask for, and the skilful interviewer, in his alluring

way, sends everything all over the land. Wise questioning is the fine art

of daily life. "It is misunderstanding," says the Dutch proverb,

"which brings lies to town." Everybody knows

that misunderstandings create divisions in families and alienations in

friendships--in parties as well as in persons--which timely inquiries would

dissipate. Intelligent questioning elicits hidden facts--it increases

knowledge without ostentation--it clears away obscurity, and renders

information definite--it supersedes assumptions--it tests suspicions and

throws light upon conjecture--it undermines error, without incensing those

who hold it--it leads misconception to confute itself without the affront

of direct refutation--it warns inquirers not to give absolute assent to

anything uncorroborated, or which cannot be interrogated. Relevant

questioning is the handmaid of accuracy, and makes straight the pathway of

Truth.

The privations of Protection, which a quick and independent-minded people

endured, was one of the wonders I saw. In Montreal, for a writing pad to

use on my voyage home, I had to pay seven shillings and sixpence, which I

could have bought in London for eighteen-pence. I took to America a noble, full-length portrait of John Bright, just as he stood when addressing the

House of Commons, more than half life-size--the greatest of Mayall's

triumphs. Though it was not for sale, but a present to my friend, James

Charlton, of Chicago, the well-known railway agent, the Custom House

demanded a payment of 3o dols.

(£6) import duty. It was only after much negotiations in high quarters,

and in consideration that it

was a portrait of Mr. Bright, brought as a gift to an American citizen,

that that the import duty was reduced to 6 dollars.

The disadvantage of Protection is that is no one can make a gift to

America or to its citizens without being heavily taxed to discourage

international generosity.

The Mayor of Brighton, Mr. Alderman Hallet, had entrusted to me some 200

volumes, of considerable value, on City Sanitation, greatly needed in

America. They lay in the Custom House three months, before I discovered

that the Smithsonian Institute could claim them under its charter. Otherwise I must have paid a return freight to Brighton, as America is

protected from accepting offerings of civil or sanitary service. There

often come to us, from that country, emissaries of Evangelism, to improve

us in piety, but at home they levy 25 per cent. upon the importation of

the Holy Scriptures--thus taxing the very means of Salvation.

For a time I sent presents of books to working-class friends in America

whom I wished to serve or to interest, who wrote to me to say that "they

were unable to redeem them from the post-office, the import tax being more

than they could pay," and they reminded me that "having been in America,

I ought to know that working people could not afford to have imported

presents made to them." Indeed, I had often noticed how destitute their

homes were in

matters of table service and all bright decoration, plentiful even in the

houses of our miners and mechanics in England. American workmen would tell

me that a present of cutlery or porcelain, if I could bring that about,

would interest them greatly.

On leaving New York a friend of mine, a Custom House officer, told me he

needed a coast coat, suitable to the service he was engaged in, and that

he would be much obliged if I would have one made for him in England. He

would leave it to me to contrive how it could reach him. The coat he

wanted, he said, would cost him £9 in New York. I had it made in London,

entirely to his satisfaction, for £4 15s., but how to get it to him free

of Custom duties was a problem. I had to wait until a friend of mine--a

property owner in Montreal--was returning there. He went out in the vessel

in which Princess Louise sailed. He wore it occasionally on deck to

qualify it being regarded as a personal garment. So it arrived duty free

at Montreal. After looking about for two or three months for a friend who

would wear it across the frontier, it arrived, after six months'

travelling diplomacy, at the house of my friend in New York.

I did not find in America or Canada anything more wonderful, beggarly and

humiliating than the policy of Protection. But we are not without

counterparts in folly of another kind.

Visitors to England no doubt wonder to find us, a

commercial nation, fining the merchant of enterprise a shilling (the

workman was so fined until late years) for every pound he expends on

journeys of business--keeping a travelling tax to discourage trade.

But John Bull does not profess to be over-bright, while Uncle Sam thinks

himself the smartest man in creation. We retain in 1904 a tax Peel

condemned in 1844. But then we live under a monarchy

from which Uncle Sam

is free.

France used to be the one land which was hospitable to

new ideas, and for that it is still pre-eminent in Europe. But America excels Europe now in

this respect. Canada has not emerged from its Colonialism, and has no

national aspiration. Voltaire found when he was in London, that England

had fifty religions and only one sauce. America has no distinction in

sauces, but it has more than 200 religions, and having no State Church

there is no poison of Social Ascendency in piety, but equality in worship

and prophesying. I found that a man might be of any religion he

pleased--though as a matter of civility he was expected to be of some--and

if he said he was of none, he was thought to be phenomenally fastidious,

if not one of theirs would suit him, since America provided a greater

variety for the visitor to choose from any other country in the world.

Though naturally dissapointed at being unable

to suit the stranger's taste, they were not intolerant. He was at

liberty to import or invent a religion of his own. Let not the reader

imagine that because people are free to believe as they please, there is

no religion in America.

Nearing Santa Fé in New Mexico, I passed by the adobe temple of Montezuma.

Adobe is pronounced in three syllables--a-dö-be--and is the Mexican name

for a mud-built house, which is usually one story high; so that Santa Fé

has been compared to a town blown down. When the Emperor Montezuma

perished he told his followers to keep the fire burning in the Temple, as

he would come again from the east, and they should see "his face bright

and fair." In warfare and pestilence and decimation of their race, these

faithful worshippers kept the fire burning night and day for three

centuries, and it has not long been extinguished. Europe can show no faith

so patient, enduring, and pathetic as this.

The pleasantest hours of exploration I spent in Santa Fé were in the old

church of San Miguel. Though the oldest church in America, there are those

who would remove rather than restore it. A book lay upon an altar in which

all who would subscribe to save it had inserted their names, and I added

mine for five shillings.

When an Englishman goes abroad, he takes with him a greater load of

prejudices than any man of any other nation could bear, and, as a rule, he expresses pretty freely his opinion of things which do not conform to

his notions, as though the inhabitants ought to have consulted his

preferences, forgetting that in his own country he seldom shows that

consideration to others. On fit occasion I did not withhold my opinion of

things which seemed to me capable of improvement; but before giving my

impressions I thought over what equivalent absurdity existed in England,

and by comparing British instances with those before me, no one took

offence--some were instructed or amused at finding that hardly any nation

enjoyed a monopoly of

stupidity. There is all the difference in the world between saying to an

international host, "How badly you do things in your country," and

saying, "We are as unsuccessful as you in 'striking twelve all at once.'"

We all know the maxim: " Before finding fault with another, think of your

own." But Charles Dickens, with all his brightness, forgot this when he

wrote of America. Few nations have as yet attained perfection in all

things--not even England.