|

[Previous Page]

THREE BUSY PLACES:

HALIFAX, BRADFORD AND LEEDS.

(From THE

SUNDAY AT HOME,

1898-99.)

IN

visiting those places which are pre-eminently "manufacturing towns,"

one's attention is too apt to be concentrated on their commercial

and present-day aspect, forgetful that this can be scarcely

understood without

some regards being thrown upon their deeper and wider foundations in

the past. When, therefore, our steps were lately led through these

great centres of industry―Halifax, Bradford, and Leeds—we resolved

to

approach them exactly as we should any cathedral or university town,

thinking first of the historic and human relations which have

developed or directed their present industrial pre-eminence.

Halifax. There is something rather quaint about Halifax. It still

has many corners which might belong to any sleepy provincial town. The hills, too, "stand about Halifax" so closely that its streets

literally clamber up

them, and one of its special features are its flights of stairs, off

whose wide "landings" one turns into little paved quadrangles, one

above the other, offering, at least, safe playing-ground for the

children, since no

wheeled vehicle can intrude. The "closes," too, are of similar

construction. Between the dwelling-houses of any of the main

streets, one sees here and there a flight of twelve or twenty steps

not wider than those of an

ordinary house, and on mounting any of these, one again finds a

little paved quadrangle, some of whose inhabitants are sure to come

out to gaze with interest on the intruder. Many of the houses in

the east end of the

town, near the Great Crossley Mills, enjoy magnificent prospects,

and their bright windows, curtained and sometimes beflowered, give

the great "lands" of flats a cheery and comfortable appearance.

Halifax is an old place, for coats of arms in the parish church tell

us that there were "vicars of Halifax" in 1274. The parish church

is a very stately building, with some singularity of construction,

and with parts of

great antiquity, though the whole was restored by Sir Gilbert Scott

in 1878. Its interior is dark with black oak, and it might be built

of black stone, so systematically and thoroughly has the grime of

the atmosphere

covered it. Its most interesting monument is that of Robert Ferran,

Bishop of S. Davids. He was a native of Halifax, and perished at the

stake in Carmarthen in the last year of Queen Mary's persecution. So

stout of

heart was he, so firm in his faith of divine upholding, that his

last words were: "If I stir through the pains of my burning,

believe not the doctrines I have taught."

The name of Halifax is said to be derived from the old church

roads―Holy-ways―fax being the Norman for such paths. Popular

legend, however, asserts that it comes from holy face, deriving from

a representation of the

head of John the Baptist, which in the remote past was kept in the

chapel of the parish church, and was the object of much devout

pilgrimage.

In one or two of the older houses in the heart of Halifax, a little

fine oak carving is still to be found. We may note especially a

certain mantelpiece bearing date 1581. Above it is to be found the

arms of the well-known

Yorkshire family of Savile, one of whom, Sir Henry Savile, was Queen

Elizabeth's tutor in Greek and mathematics. He is further

distinguished for bringing out a magnificent edition of St.

Chrysostom's works. The

production of this is said to have cost £8000.—the pride of

litterateurs of that period being in the expense of their labours,

and not in their pecuniary profit. He was assisted in his colossal

task by the learned Dr. Boyse,

who was one of the four scholars who were hired by the Stationers'

Company to revise translations of the "Apocryphal Books" for an

honorarium of thirty shillings per week while their task was

proceeding.

Lady Savile was jealous, as wives sometimes are, of her husband's

absorption in his studies. Poor woman! She said she wished she was a

book, as she might then receive a little attention, and all the

comfort her

husband gave her was the playfully ungallant answer that "he would

fain have her an almanack that he might change her every year." On

another occasion she threatened, perhaps not quite seriously, to

burn

Chrysostom, declaring that her husband's studies were killing him.

"That were a great pity," remarked the gentle reviser Boyse. Her

response gives us the key to the whole position, for the ignorant

cannot be the

sympathetic: "Why, who was Chrysostom!" she asked. "One of the

sweetest preachers since the Apostles' time," was the answer. "Then

I would not burn him for the world," said she, instantly rebuked. Had Sir

Henry condescended to give some serious "attention" to the mind of

the living woman beside him, who knows but it might have shed some

light on his dusty tomes, as it would have certainly supported him

by

interest and admiration.

In the time of the Wars of the Roses, Halifax was a mere village of

twelve or thirteen houses. But soon after, in the course of the

reign of Henry VII., Flemish artizans and weavers settled in it, and

the growth of its

importance began.

A strange, fierce, old law had from time immemorial existed in the

district of Halifax (it can be traced to 1280), whereby any person

in the district, accused and convicted of felony to the amount of

"thirteenpence

halfpenny," was beheaded in the market-place on one of the next

market days. The engine of execution was a sort of rude guillotine,

and every spectator was expected to take hold of the rope, "or to

put forth his arm

so near to the same as he could get, in token that he is willing to

see justice executed," so as to cause the axe to descend on the neck

of the culprit. Nay, if the theft had concerned ox, sheep, horse, or

cattle, then

even the animal itself had the rope fastened to it, and was made to

join in the act of doom.

The "trial" was conducted under the supervision of the lord bailiff

and sixteen burghers. Accused, accuser, and the subject of theft,

were brought forward and confronted with each other. No oaths were

taken, but

evidence was adduced. If deemed sufficient, and a market was going

forward, the offender was instantly executed. If it was not market

day, he spent the interval in the public stocks. On the other hand,

if the evidence

failed to establish the charge he was at once set at liberty. A

thief who succeeded in escaping arrest till he got outside "the

liberty of Halifax," was safe; he could not be brought back. But if

he ever returned, he was

liable to the same punishment. There is a cruel case recorded

wherein a man who had spent seven years of honest living outside

this dread boundary, was, on his coming back, made to suffer for his

old offence. A

certain local phrase—"I trow not, quoth Dinnis,"— originated with

another culprit, who succeeded in escaping after he had been

condemned, and being met as he went away by country folk who asked

if one Dinnis was

not to be executed that day, he answered, "I trow not," and passed

on his road.

It can be readily understood that with an increasing town

population, together with the growth of manufactures, whose nature

and bulk offered more temptation to petty theft than did a fine

young bullock or some logs of

wood, these summary executions soon grew very numerous. Between 1541

and 1650, forty-nine people were thus put to death in the

market-place of Halifax, the greater number of these executions

occurring in the

reign of Queen Elizabeth. But in this respect, despite its own

special severity, Halifax is not likely to have been worse than any

other part of England, since during the thirty-eight years of Henry VIII.'s reign, no fewer

than seventy-two thousand perished on the scaffold.

The last Halifax execution took place in 1650, when the bailiff

received warning from headquarters that if another occurred he would

be held responsible for it. As capital punishment for theft and

allied offences persisted

till the second quarter of the present century, it is evident that

the objection to the Halifax arrangement was not against the

severity of the sentence, but against the summary and

self-constituted court which

pronounced it.

It is said that the "engine" employed on the Halifax criminals

furnished Earl Morton with the model for his famous "maiden," with

which he wrought such havoc in Scotland, until he himself finally

perished in her deadly

embrace.

The worsted and carpet trades form the staple of Halifax industry. Crossley's carpet works, the largest in the world, employ five

thousand hands. We found the work-people, whom we met pouring out

through the great

gates, very ready to give information, and apparently proud of the

extent and importance of their mills. The women, clean and

picturesque with their shawled heads, were pleasant mannered and

comely. One observed

that many of these "factory girls " were well on in "the forties,"

explaining the phrases "t'owd lad " and "t'owd lass," so constantly

heard in Yorkshire. We were told that they earn, mostly by

piecework, from 15s. to

20s. per week.

The centre of the town is very concentrated with its bright

well-stocked shops, fine new market-place, and handsome places of

worship. The newer part of the town, towards Skircoat, contains

pleasant residences and

large, well-timbered gardens.

Halifax has four parks. Savile Park, by Skircoat, is a large open

moor. Shroggs Park, and the Akroyd Park, both lie to the east of the

town, the latter contains an art gallery and museum, and a branch

library with

fifteen thousand volumes, and on its margin stands the fine modern

church of All Souls, erected by Mr. Edward Akroyd. The People's

Park, containing upwards of twelve acres, is not far from the centre

of the town, and

is the gift of the late Sir F. Crossley, the town contributing £300

annually for its up keep.

Sir Joseph Crossley's former residence has been converted into a

public library with 28,000 books, about 350 being issued daily. There are also the libraries of the Literary and Philosophical

Society, and the

Mechanics' Institute, the former containing 20,000 volumes, the

latter 12,000.

Halifax is also well equipped educationally. It is said that about

two-thirds of the children come under the School Board. The Blue

Coat School provides for sixty boys and girls, and its almshouse

shelters twenty-four

old dames receiving a dole of five shillings weekly. Each of the Crossley Brothers, Francis and Joseph, made special provisions for

old folks. Halifax further rejoices in a very unusual institution

founded from money left

to trustees by the late John Abbott. This is the Abbott's Ladies'

Homes, and consist of twelve four-roomed cottages, each of whose

elderly or invalid inmates receives an allowance of fifty-two pounds

per annum.

The population of Halifax is now about 84,000. It is said that its

workhouse has room for 700 inmates, exclusive of vagrants.

Nothing strikes one more in travelling through Yorkshire than the

number of its towns, evidently of considerable magnitude and

importance, whose names are quite unfamiliar outside the

manufacturing and commercial

world.

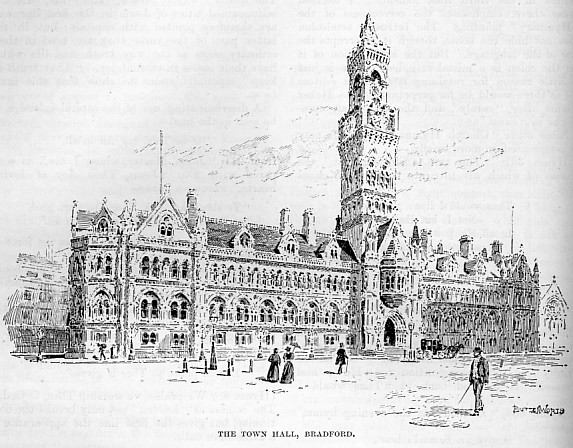

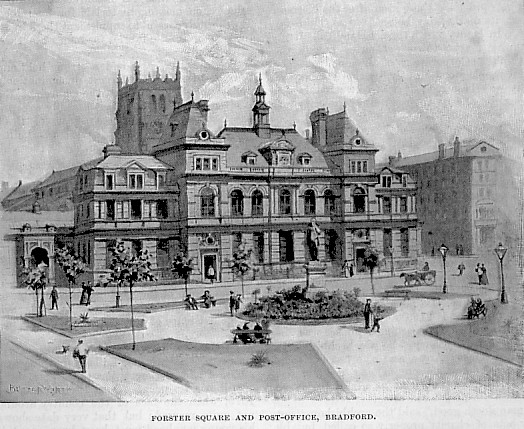

Bradford. As we approached Bradford, one of its citizens, who was

our fellow-traveller, proudly assured us that we should find there "some of the finest buildings in Great Britain," he "should not like

to say how many

storeys high." The description did not greatly cheer us, nor did the

appearance of Bradford much attract us. One's impression is that it

is all mills and business, and one wonders where the people live and

indeed where

they are, for in the intervals of going to or from work, the

streets, many wide enough, but all gloomy through the height of the

smoke-blackened buildings, seem well-nigh deserted.

The residential suburbs are rather remote from the centre of the

town, and only to be reached by wide, but rather unattractive

thoroughfares, off which are narrow openings mostly filled with tiny

houses. Here and there,

however we find signs that, at no remote period, the "better classes" lived nearer to the heart of things. These signs are little

cloistral squares looking not unlike the precincts of convents or

almshouses. The dwellings

here, without being large, are such as would have met the demands of

well-to-do people half-a-century ago. Many of these, now inhabited

by people in some way connected with "social work," are nicely

appointed and

put the best face on matters. In the little old squares one may

still see the forgotten notice boards of a once exclusive gentility,

proclaiming that anybody found walking there, except when going to

the houses, "will be

prosecuted."

But though the Bradford of to-day shows few traces of antiquity,

both it and its typical industries have a very early origin. "The

parish of Braforthe" is mentioned in very old charters, and woollen

cloth making was

practised there soon after the Norman Conquest, its market-day being

fixed as Thursday in 1256. In Henry VIII.'s time, Leland calls it "a

praty quick market-town." Charles I. sold the manor to the

Corporation of London,

but the Bradford people stood stoutly by the Parliament. Twice it

was besieged; it was converted into a royal garrison and its then

existent prosperity was well-nigh destroyed.

In those days nearly every house in Bradford had its garden, and

unsophisticated country smiled around. The situation is said to have

been peculiarly beautiful, at the junction of three smiling valleys.

When peace was again restored to the kingdom, Bradford took up the

weaving of worsted—the peculiar woollen thread which gets its name

from having been made by Flemish artizans who settled in the village

of

Worsted, Norfolk. But the tremendous influx of labour and commerce

which makes one authority say that "The real energy of Yorkshire

settles in Bradford," only came in with the present century. Its

population was

then little over 13,000, now it is 216,000.

The Bradford of the gardened houses was the birthplace of John

Sharp, who was archbishop in the reign of Queen Anne, and who has

left some practical considerations on "Doing good in our lives,"

which are every

whit as useful to-day as they were when he uttered them.

"A man doeth good," said the archbishop, "not only by acts of

charity properly so called, but by every courtesy that he doth to

another . . . . by contributing in any way to make the lives of others

more easy and

comfortable to them . . . . A man also doeth good when he makes use of

that acquaintance or friendship or interest that he hath with others

to stir them up to the doing of that good, which he, by the

narrowness of his

condition, or for want of opportunity, cannot do himself. This is a

very considerable instance of doing good, how slight soever it may

seem: the man that exercises himself this way is doubly a

benefactor, for he is not

only an instrument of good to the, person or persons for whom he

begged the kindness or the charity, but he does also a real kindness

to the man himself whom he puts upon the benefaction, for God will

not less

reward his good will for being excited by another . . . . We

do good when we so carry ourselves in all the relations in which we stand as

the nature of the relation requireth . . . . We also do good by an

honest and a diligent

pursuit of our calling and employment."

Bradford has erected statues to the politicians Sir Robert Peel, and

"Education Forster," to Oastler, the friend of factory children, and

to Sir Titus Salt, who is certainly entitled to ample recognition

under Archbishop

Sharp's last definition of a "doer of good," since Salt's shrewd

recognition of a use for what had been hitherto regarded as a waste

product―the wool of the alpaca—for many years furnished employment

to hundreds of

thousands.

A significant hint as to the substantial damage which may be

inflicted on industry by heedlessly varied fashions is found in the

fact that Bradford soon proved that its labourers could have no

reliance on making

materials for feminine wear. It was wisely careful to supplement

these by the production of textile fabrics for men's use, furniture,

cloths, and braids.

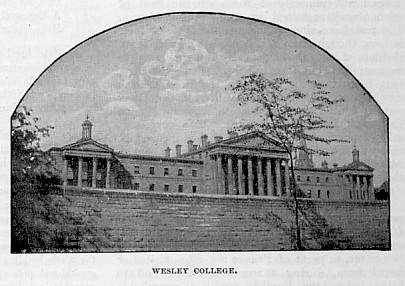

Wesleyanism early laid a strong hold on Bradford, and remains its

largest denomination. The Independents follow next, the Church of

England itself coming third, which is possibly explained by the fact

that during

twenty years of Bradford's most rapid growth no new church was built

there. That apathy has since vanished, the churches have multiplied,

and Canon Bardsley, the late vicar, has done good and active

service. On the

other hand, Nonconformity in Bradford, and even in Yorkshire

generally, is said by some to be growing rather lax and apathetic;

and to have lost not only the warmth and fervour of its first love,

but also something of its

moral and intellectual backbone.

Bradford is well equipped with educational institutions and

societies. It has five parks, skirting the town, four of them being

of considerable extent.

The Yorkshire musical faculty finds evidence in the existence of

eleven musical unions in Bradford.

Further, the Bradford of this century—the Bradford of upspringing

mills, of machine-smashing mobs, of labour competition, of poverty

and gloom —still has its poet! True, Preston was born in 1819, when

the face of the

country around was not quite marred; but that very date shows that

his young manhood must have been spent in the days of Bradford's

fiercest and angriest struggles. He was a true poet, writing of

his "ain folk" in their own homely tongue. In his verse he often embalms

fine old customs which the hard tread of modern days must soon wear

out. For instance, in the "Sacred Drawer," where the mother is

turning over

the little relics of her dead child, she wails

"I canna turn t' key wi' my bairn outside,"

an allusion to the tender old West Riding custom which left the

house door unlocked for seven nights after a funeral—a usage which

could scarcely be practised in the Bradford of to-day.

We venture to quote a few of Preston's verses, interesting in

dialect, and also as showing that the same love that is found in

huts where peasants lie, does not forget the attics of the factory

worker.

The middle aged man is thinking of his boyish love.

"I'd leet of a sun 'at has long since set;

I see t'chapel o' Primrose Brow;

An' what friends on a Sabbath day there have met,

That forever are pairted now.

"They come an' they smile an' away they pass,

But they allus leave one i' view—

A poor little fatherless country lass,

'At once sat i' t'singer's pew.

"Well, this world gets as cou'd and as hard as steel,

An' at times I feel fain Shoo's dead;

For Shoo'd hard to work at her loom an' her wheel

For a morsel o' honest bread.

"More nor twenty years Shoo's been dead an' goan,

But wherever ma lot may be,

When 'thouse is all husht an' I'm left aloan,

She allus comes back to me.

"I've wish't 'at I telled her by t'garden door

How deep were my love an' true,

For t'friends o' that orphan were few an' poor;

But noa matter—I think Shoo knew!" |

Leeds. Bradford and Leeds are as closely associated in their past

history as in their present commerce. Both are in the district which

was dominated by the great Norman family of the De Lacier, who

received from

William the Conqueror the gift of one hundred and fifty Yorkshire

manors, and who probably built that castle of Leeds which was

besieged by King Stephen, during his desperate struggle with the

Empress Matilda,

filling the land with slaughter and dismay for nigh twenty years. One writer says of the misery of that period "many abandoned their country: others forsaking their houses built wretched huts in

churchyards, hoping for protection from the sacredness of the place. Whole families,

after sustaining life as long as they could by eating herbs, roots,

dogs and horses, perished at last with hunger, and you might see

many pleasant villages

without one inhabitant of either sex."

A little later Leeds Castle was one of the prison houses of Richard

II. on his way to his mysterious end at Pontefract. The castle has

utterly disappeared; it is believed to have been situated on Mill

Hill.

Leland, who was the king's antiquary in 1533, alludes to Leeds as "a pretty market town, subsisting chiefly by cloaking."

Leeds suffered sharply in the Civil War, but still more in the great

plague, which had so baleful an effect on its activities, that it is

said grass grew over the public highways. Nevertheless, it presently

got its share of the

extraordinary advance made by the business of the whole kingdom

immediately after the Restoration—which advance, by the way, is said

to have been really due to wise measures taken during the

Commonwealth! For

Cromwell had called together what was really our first Board of

Trade, to consult how commerce and navigation could be best promoted

and regulated. Thus one sows, and another—haply his enemy—reaps,

but good

work always remains good, and worthy workers ask no other reward.

It was about this time that Leeds Cloth Halls were founded—the

forerunners of later edifices of allied purpose. Charles II. gave

Leeds a charter to protect its merchants and manufacturers from the

frauds which certain

adulterators were practising in the preparation of woollen cloths. From this period the progress of Leeds has been steady. But its

enlargement has gone up by leaps and bounds during the present

century. This is

shown by a certain account of Leeds as it was in 1806.

"The manufacturers are dispersed in villages and single houses over

the whole face of the country; they are generally men of small

capitals, and often annex a small farm to their other business. Great numbers of the

rest have a field or two to support a horse and a cow, and are for

the most part blest with the comforts, without the superfluities of

life. Of late years, however, manufactories of cloth have been

established on a larger

scale, in which the whole process of the making of cloth from the

raw material to the finishing of the piece ready for the weaver is

carried on."

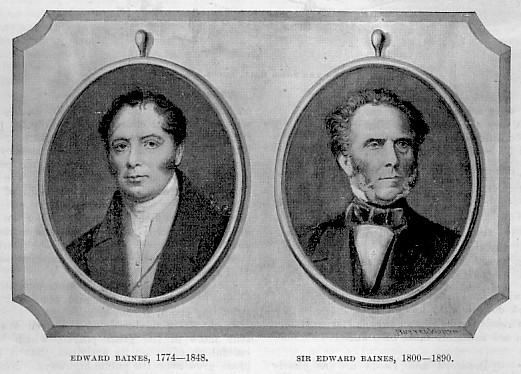

It was to such a Leeds as this that, some ten years earlier, Edward

Baines, destined to be one of its most notable and useful citizens,

had come, a printer's apprentice, trudging in on foot, with a trifle

of money in his

pocket and a bundle of small possessions in his hand. He arrived,

too, with something like an aroma of misfortune hanging about him. For he had been apprenticed in a neighbouring town, and work had

proved so

slack, that the closing years of his indentures had been given back

to him, and he had come to Leeds in search of some master willing to

take up the remnant. But there was courage and nerve and resource in

the lad,

who had already been the hero of the following curious occasion.

"At Preston, at a festival of the Guild Merchants, held with great

splendour every twenty years, the housetops had been covered with

people to witness the procession, and when all was over, and the

spectators had

withdrawn, a man was seen asleep on the roof of a house, three

storeys high. It seemed almost inevitable that if he awoke he would

fall from the roof in which case his death was certain. There was no

ladder and no

visible means of reaching the roof to warn the man of his danger

when young Baines climbed up the front of the house by a wooden

spout, and laying hold of the man, gently awoke him and enabled him

to place

himself in safety."

After Edward Baines had finished his apprenticeship in Leeds, he set

up in business for himself in the Briggate, its old fashioned

thoroughfare, often rising at three or four o'clock in the morning,

to get his own business

despatched by his own hands. He married a woman of whom it is said

that "her characteristic was outspoken sincerity" —that she was "a little given to over-anxiety, but very cheerful,"— all traits

(since over-anxiety

may well be but an exaggeration of foresight) which signify that she

was a good helpmate, especially when we are further told that a

stipulation before marriage was—not for privilege or pin money—but

for "regular

family prayer."

In due time Edward Baines became editor of the Leeds Mercury, a

paper which gave him an immense field whereon to advocate his truly

progressive principles of peace, civil and religious liberty, and

national economy.

Afterwards he sat in the House of Commons as member for Leeds,

taking his seat with the declaration: "My own judgment and

conscience shall be my guide, and the general happiness of the

people my aim." He

died in 1848, and may take his place in our memories as showing how

a man, without extraordinary advantages or shining gifts, may, by

sheer industry, energy, and worth, achieve a position of useful

influence which

far outweighs more sensational forms of success.

The cause of the poor factory children

|

"Weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free," |

found some of its prominent champions in Leeds, and among its

manufacturing class. There was Tom Sadler, both by culture and birth

something of an aristocrat, being descended from Sir Ralph Sadler,

one of Queen

Elizabeth's ministers who was deputed to carry to James of Scotland,

the news of his mother's execution. There was Robert Hall, a learned

lawyer, also enlisted in the children's cause. Above all, there was

Richard

Oastler, known as "the factory king" whose statue we had seen in

Bradford.

Those were "the days when no law prevented mill-owners from exacting

fourteen and fifteen hours of monotonous toil daily from tender

frames of young children whose ages were sometimes barely half as

many years."

In detailed fact, the Cotton Mills Act of 1819, fixed the working

age of children as nine and their number of working hours per week

at seventy-two! Even the Saturday half holiday was not exacted till

six years later. Yet

it must be remembered that a high authority asserts that between

1800 and 1850 the wealth of the country increased more rapidly than

in all the previous eighteen centuries since the coming of Julius

Caesar! It was a

wealth founded, alas on bitter pain and poverty.

Richard Oastler was born in Leeds in 1789, the son of a worthy

merchant who had often hospitably entertained John Wesley, and who

liked to tell how, on the great preacher's last visit, he had taken

little Dick in his

arms and had solemnly blessed him. The boy was educated at the

Moravian school at Fulneck. His first public work was to earnestly

support Wilberforce in his advocacy of negro emancipation. Some of

his political

views were so unpopular, that he was roughly handled by his

opponents, and on one occasion his coat was torn from top to bottom. With some grim sense of humour, he afterwards persisted in wearing

this garment in

public processions. By 1825, he was actively engaged in pleading the

wrongs of the factory children. His claim was indeed modest enough;

he asked only that their working day should be limited to ten hours! It is

said that groups of these suffering children sometimes attended his

meetings, listening with premature intelligence and adding the

pathos of their shrill voices to the applause.

In one of Oastler's speeches there occurs the following awful

sentence, a terrible indictment of fatherhood, when tempted by

indolence and cupidity—"I have seen full-grown athletic men whose

only labour was to carry

their little ones to the mill long before the sun was risen, and

bring them home long after it had set."

Oastler himself fell on evil days, for he was sent to prison for

three years for a debt which he declared had been contracted in the

service of his employer and for his interest. He received a great

deal of sympathy and

the sum was eventually paid by public subscription.

Despite the earnest and continued efforts of Lord Ashley (afterwards

Earl of Shaftesbury) and the good men we have named, there was no

really sound factory legislation till 1847, when a "ten hours'

Bill for women

and children" was passed, as it happened, while Lord Shaftesbury

was not in Parliament.

Since that period factory legislation has steadily advanced on the

wise and just lines of protecting the weak and undeveloped so that

they may have opportunity to become the strong and useful.

We reached Leeds on a Saturday, and of course found the places of

business closed—and the streets, especially the Briggate and Boar

Lane, so thronged with people that we could scarcely make our way. All the

shops in these thoroughfares were open, brilliantly lit and

abundantly stocked. Large crowds were waiting in front of the

theatres, whose advertisements seemed all of melodramatic pieces. Trams and buses were going

to and fro, crowded with people, and one very popular public

conveyance was a kind of waggonette with an awning overhead,

something like the vehicles used in Canada.

In all the crowds in the thoroughfares named, we saw absolutely no

drunkenness. It struck us that most of the people were young, rather

undersized, but well-fed, well-dressed, and in the best of spirits. We noticed,

however, many poor, starved looking children, of very tender years,

hanging on the skirts of the crowd and trying to sell flowers, small

wares, and above all newspapers recording the result of a great

football match. The

wall advertisements of all the local papers dwelt emphatically on

athletic and sporting news. We also observed many groups of elderly

men of that terribly loafing type one sees in the East End of

London. The Briggate

is, in the main, a very modern street, but here and there one finds

a timbered house-front or a quaint old shop which tell of the

earlier time.

On Sunday, we found harvest services going forward everywhere, and

we noted that even Methodist chapels, of apparently all shades of

Methodism, announced musical services, vocalists, and selections

from

Oratorios. Many also advertised the subjects of sermons.

From the point of view of the antiquarian, the most interesting

church in the town is St. John's in the Briggate, which was

consecrated in 1634. It is said to be an excellent specimen of a

"Laudian" church, and still retains its original fittings.

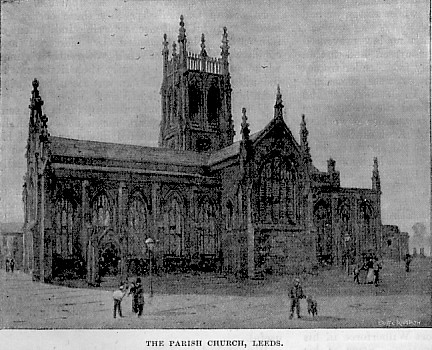

The parish church of St. Peter, in the Kirkgate, was rebuilt in

1840, under the auspices of the famous Dean Hook, who was then Vicar

of Leeds. Less than half-a-century old, its exterior is already

blackened by the atmosphere, and its interior is sombre with dark

oak and rich stained glass. The yard about it is paved with old

grave-stones, and is enclosed in a neat and pleasing precinct

comprising a Church House, a Church Club, a Church Ladies' Club, and

allied institutions.

Since the time of William the Conqueror there has always been a

church on this spot, and tradition has it that there was one even in

the time of the Saxon Heptarchy.

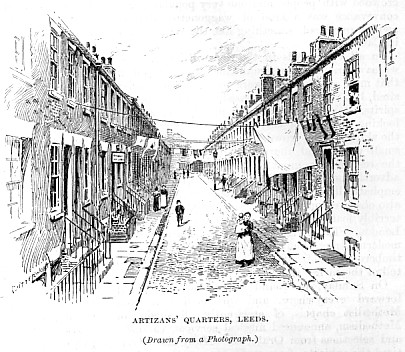

Returning from church to the centre of the town, down the highway

named "The Calls," and "Swine Gate," we passed through a poor

neighbourhood, whose corners and byways abounded with unkempt Sunday

morning loafers. We noticed that nearly every third or fourth house

had an open way through it, no wider than an ordinary house passage. These opened into little paved back courts, some bright and neat,

others utterly

squalid.

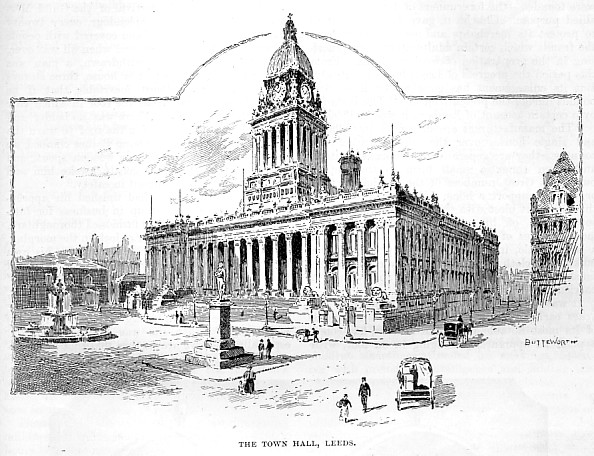

The most modern part of the town, where the great warehouses and

public buildings are, is built in a pretentious Renaissance style,

but local authorities frankly admit that "the universal coating of

grime spoils even the

finest buildings."

Ruskin tells us that "we cannot all have our gardens now nor our

pleasant fields to meditate in at eventide. Then the function of our

architecture is, as far as may be, to replace these to tell us about

Nature; to possess

us with memories of her quietness, to be solemn and full of

tenderness, like her; and rich in portraitures of her: full of

delicate imagery of the flowers we can no more gather, and of the

living creatures now far away from us in their own solitude."

In the light of such words, what are we to think of some of the

"architecture" in Leeds? The favourite decoration seems to be stone

half-figures chiselled as bent and writhing under the weight they

are made to support.

In one horrible instance, the pediments are formed of crouching

shrinking dogs, on whose bodies stand, as columns, human figures,

their own heads bowed forward, that the weight of the building may

seem to rest on

the nape of their necks! We hope that a day of better feeling and

taste has dawned, that these horrid fantasies of cruelty will pass

away, and that none like unto them will be added to their number.

Before we left Leeds, we knew it as well as it is possible, in a few

days' visit, to know a place of nearly four hundred thousand

inhabitants—the city fifth in population in the whole of England. It

is well equipped in many ways, with thirty-four churches, and more

than eighty chapels. Its municipal buildings include a reading-room,

a free library and a fine art gallery. It has other public

libraries. Its Mechanics' Institute offers many advantages—we were

struck by its attractive list of lecturers. It has a fair range of

philanthropic work of every kind.

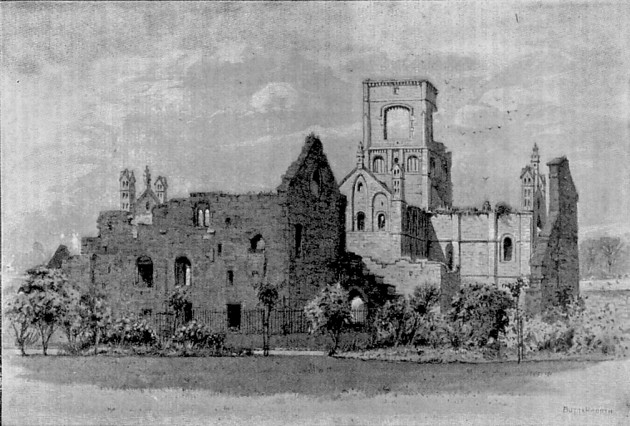

Kirkstall Abbey, Leeds, from the West.

One of the favourite "outings," of the Leeds people is to Kirkstall

Abbey. This lies to the west of the town, and is reached by a road,

the greater part of which is Dantesque in ugliness. Presently one

or two pleasant

terraces are reached, and the river comes to view. At last the town

ends quite abruptly, and one finds oneself in sight of the old

Cistercian abbey. It is in itself of great beauty and interest, but

its exterior has been

stripped so bare of ivy and tree, that at first sight, at a little

distance, it looks uncommonly like a wrecked factory. There has been

much local lamentation over the destruction of one particularly

noble old tree—a doom

accorded, it is said, lest gales should uproot it, to the possible

damage of the fragile ruins.

Down great highways, into which on either hand opened streets of

monotonous houses (many of them built back to back), we drove to

Roundhay Park, bought for public purposes by the Leeds Corporation

for £140,000. It is indeed a beautiful treasure for any city to possess,

consisting as it does of 800 richly-wooded and softly-undulating

acres, while being on the unsmoky side of Leeds, it gets little or

no damage from its grimy proprietor. But alas, it is nearly four

miles from the centre of the town, and half a mile's walk beyond the

tramway terminus. That means that it is further still from the

denizens of the crowded courts of Swine Gate. So what of the poor

old folks and the pale little children? Where have those to sit and

rest? And where have these to go and play?

Lockhart, the biographer of Sir Walter Scott, said that if the

history of any one family could be faithfully written, it might be

as generally interesting and as permanently useful as that of any

nation however great or

renowned. We have tried to prove that the same holds true of places,

even of those which are generally thought to be bare of romance and

suggestion. Good and unselfish lives are to be found everywhere,

glorifying

even factory chimneys, and softening furnace fires. The true

direction of wealth is in furnishing fit conditions for such lives. In the struggle with the difficulties and darknesses of modern

civilisation, it is helpful to

remember that the Kingdom of Heaven has been presented to our minds

by prophet and apostle, under the symbol of a city. By the vision of

brightness and beauty which their words bring, we begin to learn

what our

own duty is, if we dare to look for answer to our daily prayer. "Thy

kingdom come, on earth, as it is in heaven." I. FYVIE MAYO.

――――♦――――

SHEFFIELD, YESTERDAY AND TODAY.

(From THE

SUNDAY AT HOME,

1898-99.)

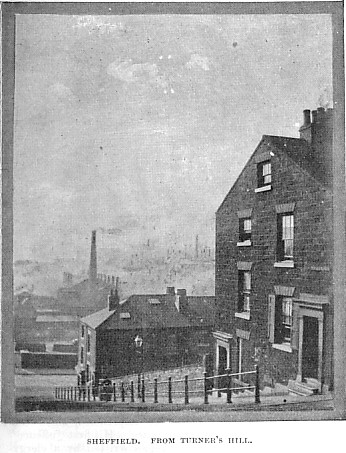

WHEN we visited

Sheffield—passing through the romantic country which still lies

around the metropolis of steel, marred only by the low smoke clouds

which hide the blue heavens—a rich autumn sunshine had just strength

enough to strike out some Turneresque effects upon the thickened

atmosphere out of which the great chimney-stacks rose, like huge

masts from a befogged sea. But we could not resist asking

ourselves:

"What of the gloomy weather?—and the winter days?"

This is the penalty which Sheffield pays for the great

industry which has made her name known throughout the civilized

world—and the uncivilized too—Sheffield knives and other cutlery

having found their way everywhere. Of these goods, the

reputation was made neither to-day nor yesterday. For Chaucer,

in his "Reve's Tale," tells of the miller:

|

"There was no man for peril durst him touch,

A Sheffield whittle bare he in his hose," |

the "whittle being evidently stuck in his stocking, after the

fashion of Highlanders with their dirks, and needing no commendation

beyond the mere name of the place where it was made.

Chaucer died in 1400. But Sheffield had had plenty of

time to build up the character of its work before that period.

Nor is its history all comprised in the skill of clever artificers.

For its name (derived from the river "Sheaf" and from the cleared

land on which trees have been felled) emerges in the remotest

periods of our island story. It is believed that a Roman camp

once existed in what is now the very heart of the city—the

bleak-looking graveyard which surrounds the fine old parish church

of St. Peter. Certain it is that Sheffield was the capital of

the Saxon district of "Hallamshire"—the domain of the Saxon earl,

whose father, "Siward" avenged the Scotch king Duncan's death upon

the murderer Macbeth. His wife was that Judith the Norman

conqueror's niece, whose jealous family pride and ambition

eventually betrayed her spouse to death, and plunged her own closing

days in misery.

The history of Sheffield is entwined with that of a Norman

family who may have come in the train of the Lady Judith, and who,

settling near Sheffield, presently became great and powerful landed

proprietors furnishing the district with monastery, hospital, market

and mill. The marriage of the last daughter of this house of

De Lacy carried its possessions and influence into another family,

which numbered among its members a Crusader who fought by the side

of Richard I. at Acre, and a staunch supporter of Henry III. against

his insurgent barons. Sheffield suffered severely at this

time, being well-nigh destroyed and most of its inhabitants put to

the sword.

Again and again this line which seems to have discharged its lordly

duties, according to the best of feudal lights—changed its course

through ending in only daughters. It was one such who finally merged

the race in that of the great Earl of Shrewsbury, that hero of

scores of victories, who received check at the hands of the

mysterious maiden Joan of Arc, and eventually died, still fighting

against France, in his eightieth year.

Again and again this line which seems to have discharged its lordly

duties, according to the best of feudal lights—changed its course

through ending in only daughters. It was one such who finally merged

the race in that of the great Earl of Shrewsbury, that hero of

scores of victories, who received check at the hands of the

mysterious maiden Joan of Arc, and eventually died, still fighting

against France, in his eightieth year.

The Shrewsbury line continued its connection with Sheffield

till it once more ended with a daughter, who married into the family

of the Dukes of Norfolk. The fourth Earl of Shrewsbury built

that "Sheffield Manor," of which nothing remains but a fragment of

restored ruin. In that house, in the days of its glory—and the

earls of Shrewsbury lived sumptuously—Cardinal Wolsey spent a few of

his last sad days, pausing there in the course of the suffering

journey which ended with his death at Leicester.

It seems to have been this fourth Earl of Shrewsbury of whom

Archbishop Parker tells a story which, though in this instance on

the side of the Englishman, yet conveys a lesson which Britons

themselves often require to consider both at home and abroad.

It seems that to the court of Hendry VIII. there came a pert

French ambassador, very fluent in speech, but with no better manners

than to criticise his hosts, dwelling on the "gluttony" of the

English race, and then dilating on the superiority of the French

language, then of almost universal use in the courtly world.

There sat at the table, Lord Shrewsbury, an agèd man, shaking with

palsy, contracted in many arduous adventures. The ambassador

singled him out for condescending notice, saying "that surely it was

a great lack to such a man's nobility that he did not speak the

French tongue." An English lord who was talking in French to

the discourteous guest, asked permission to translate his remarks to

the old earl, and then proceeded to do so in as pleasant a manner as

possible. But we must tell the rest of the story in the

Archbishop's own words:—

"When the earl heard it, where before his head, by the great

age was almost grovelling on the table, he roused himself up in such

wise that he appeared in length of body as much as he was thought

ever in all his life before. And knitting his brows, he laid

his hand on his dagger, and set his countenance in such sort, that

the French hardie ambassador turned colour wonderfully. 'Saith

the French fellow so?' saith he, 'marry, tell him if I knew I

had but one French word in all my body, I would take my dagger and

dig it out, before I rose from the table. And tell that varlet

that howsoever he hath been hunger-starved himself at home in

France, that if we should not eat our beasts and make victual of

them as fast as we do, they would so increase beyond measure, that

they would make victual of us, and eat us up.'"

Thus do thoughtless words stir up wrath, even as soft ones

turn it away, and who knows how often thoughtless words, in ever

increasing aggregate, may have solidified into those national and

racial hatreds and antipathies which finally explode in terrible

warfare, leaving behind the melancholy debris of ruined homes and

broken hearts?

Surely this grim Earl of Shrewsbury would not have been, as

was the sixth earl, unable to manage his own wife! To this

sixth earl was entrusted by Queen Elizabeth, the very ungracious

task of acting custodian to her captive "cousin," Mary of Scotland.

The Scottish queen spent the greater part of her fourteen years of

English imprisonment in this same "Manour of Sheffield." Some

authorities seem inclined to blame the royal prisoner for the

dispeace which broke out between her noble goaler and his spouse.

Mary had certainly wrought havoc wherever she moved, but in this

instance it must be remembered that the Countess of Shrewsbury had

been already three times a widow, and that bishops spoke of her as

"that sharpe and bitter shrewe." At any rate, she enlisted

Queen Elizabeth's sympathy with herself as against her lord, so that

a year after Mary of Scotland's execution, Elizabeth apportioned the

earl five hundred pounds a year, and put all the lands and revenues

in the power of his wife. The aggrieved husband wrote piteous

letters on the subject.

"Sith that her majestie hath sett dowen this harde sentence

against me, to my perpetual infamy and dishonour, to be ruled and

overawne by my wief, so bad and wicked a woman: yet her majestie

shall see that I obey her commandemente, though no curse or plage in

the erthe cold be more grievous to me."

The poor man rests at last among his ancestors in the

"Shrewsbury Chapel" of the old parish church. There is

something of humour in the fact that the inscription on his monument

was written by Foxe, the commemorator of martyrs.

His countess lived an active bustling life, superintending

her estates (she inherited from more than one of her husbands),

developing their resources, pulling political wires, and patronising

wits. She survived to the age of eighty-seven, leaving behind

immense fortunes, and the evil repute of being "a proud, furious,

selfish and unfeeling woman." What a pitiful failure for a

human life!

A very different life also has its memorial in this fine old

church of St. Peters. James Montgomery, one of the gentlest of

men and of poets, though born in Scotland, spent all his working

days as a journalist in Sheffield—then neither so prosperous, so big

nor so gloomy, as it is now. His life and story make us think

of a dove caught in a storm. For not all his gentleness and

conciliatory spirit—these being coupled with truth and justice

—could save him from being regarded as "a political offender" in

that agitated period of the great French Revolution. In 1794,

and again in 1795, he found himself imprisoned, fined and bound over

to keep the peace. His first "offence" was publishing some

verses written by a clergyman exulting over the demolition of the

Bastille: his second, his printed censure on the conduct of a

Sheffield magistrate, one Colonel Athorpe, in firing on a crowd.

How many have learned to love Montgomery's simple verses, "Sow in

the morn thy seed," or "Prayer is the soul's sincere desire," or

"For ever with the Lord," or the jubilant "Hail to the Lord's

Anointed," unknowing that this sweetness of devotion was distilled

from a, soul which had passed through experiences that might have

embittered and hardened some, but which only saddened and softened

him. It is pleasant to know that nearly fifty years after

these "contradictions of sinners," James Montgomery could say:— A very different life also has its memorial in this fine old

church of St. Peters. James Montgomery, one of the gentlest of

men and of poets, though born in Scotland, spent all his working

days as a journalist in Sheffield—then neither so prosperous, so big

nor so gloomy, as it is now. His life and story make us think

of a dove caught in a storm. For not all his gentleness and

conciliatory spirit—these being coupled with truth and justice

—could save him from being regarded as "a political offender" in

that agitated period of the great French Revolution. In 1794,

and again in 1795, he found himself imprisoned, fined and bound over

to keep the peace. His first "offence" was publishing some

verses written by a clergyman exulting over the demolition of the

Bastille: his second, his printed censure on the conduct of a

Sheffield magistrate, one Colonel Athorpe, in firing on a crowd.

How many have learned to love Montgomery's simple verses, "Sow in

the morn thy seed," or "Prayer is the soul's sincere desire," or

"For ever with the Lord," or the jubilant "Hail to the Lord's

Anointed," unknowing that this sweetness of devotion was distilled

from a, soul which had passed through experiences that might have

embittered and hardened some, but which only saddened and softened

him. It is pleasant to know that nearly fifty years after

these "contradictions of sinners," James Montgomery could say:—

"All the persons who were actively concerned in the

prosecutions against me in 1794 and '95 are dead, and, without

exception, they died in peace with me. I believe I am quite

correct in saying, that from each of them distinctly in the sequel,

I received tokens of goodwill, and from several of them substantial

proofs of kindness. . . . I mention the circumstance as an evidence

that, amidst all the violence of that distracted time, a better

spirit was not extinct, but finally prevailed, and by its healing

influence did indeed comfort those who had been conscientious

sufferers."

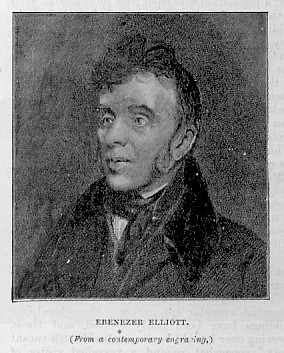

Sheffield can boast of another poet, but of a very different

calibre. Ebenezer Elliot—the "Corn-Law Rhymer," had "Border" blood

in his veins, but was born in Yorkshire, and drifted to Sheffield in

his maturer years. He had a hardy, rugged, yet not unhappy

childhood, but though he records that his schoolmaster was "one of

the best of living creatures,—a sad-looking, half-starved angel

without wings," the boy was set down as a hopeless dunce. He showed

no sense nor diligence where books were concerned, yet half a

century later he could dwell on the habits of birds which he had

watched during his walks to and from school. He was clearly one of

the many victims of educational systems which treat all minds as of

similar formation. He was quite glad when, partly as a punishment,

he was early sent to work in a foundry, for then he says he found

that he "could at least equal others in manual labour." Sheffield can boast of another poet, but of a very different

calibre. Ebenezer Elliot—the "Corn-Law Rhymer," had "Border" blood

in his veins, but was born in Yorkshire, and drifted to Sheffield in

his maturer years. He had a hardy, rugged, yet not unhappy

childhood, but though he records that his schoolmaster was "one of

the best of living creatures,—a sad-looking, half-starved angel

without wings," the boy was set down as a hopeless dunce. He showed

no sense nor diligence where books were concerned, yet half a

century later he could dwell on the habits of birds which he had

watched during his walks to and from school. He was clearly one of

the many victims of educational systems which treat all minds as of

similar formation. He was quite glad when, partly as a punishment,

he was early sent to work in a foundry, for then he says he found

that he "could at least equal others in manual labour."

He afterwards ran some risk of falling into the greater dangers of

ill-regulated young manhood. He was saved by a providence which

roused and directed the love of nature lying latent within him. A

widowed relative showed him "Sowerby's English Botany," and he took

to copying its plates, and better still, to gathering plants for

himself. His consequent wanderings leading him aside from the

alehouse and idle company, soon, says he, "made me acquainted with

the nightingales in Basinthorpe Spring, where, I am told, they still

sing sweetly, and with a beautiful green snake (he calls it "this

beautiful and harmless child of God"), which on the fine Sabbath

mornings, about ten o'clock, seemed to expect me at the top of

Primrose Lane. It became so familiar that it ceased to uncurl at my

approach."

These pursuits led him to the discovery that even books held some

things worth the learning. He set himself to make up, as well as

might be, for lost time. But long afterwards he owned that he knew

no rule of English grammar, though by study of the best masters he

could write English correctly.

In due time, he went to Sheffield and went into business for

himself, once unsuccessfully, the second time, when he was forty

years of age, with very considerable profit. Much of his gains,

however, were snatched from him when the panic and revulsion after

the operation of the Corn Laws made a very evil epoch for the United

Kingdom. At this time, he, having already attempted literature,

burst into a fiery popularity by the stormy verses which earned him

the name of the "Corn Law Rhymer."

It is hard to say whether his genius lost or gained by this special

application of it. What he lost in breadth, he possibly gained in

force. "Half Battles" were some of the words he wrote, and without

doubt they did their share in combating the evils they denounced,

and in calling for greater consideration of much that was wrong in

the lot of the labourer.

Ebenezer Elliott is essentially a Sheffield figure, for his trade of

ironmonger associates him with the peculiar industry of a city whose

"arms" have for supporters Thor and Vulcan. In Elliott's best-known

verses, beginning

|

"Idler, why lie down to die?

Better rub than rust," |

he actually draws a poetical image from his calling wherewith to

enforce a practical lesson.

In the beginnings of Sheffield—while its neighbourhood abounded with

deer, and venison was the common food of those who could afford

meat—the grinding wheels and small workshops were sprinkled about

amid much that still remained countrified. They were rough

buildings—seven or eight yards long, and four wide, seven feet high

to the spring of the roof—the walls plastered with clay the floor of

mud, hens roosting in the rafters.

In 1570, many artizans from the Netherlands, fleeing from the

Spanish tyranny there, settled in Sheffield. Still, in 1615,

Sheffield contained little more than two thousand two hundred

people, and of these more than a thousand were children, and only

ten families could afford to keep a cow. The Cutlers' Company,

though practically existent much earlier, was only formally

incorporated in 1624. Its early records shed an interesting light on

the labour questions and combinations of that period. Those who are

inclined to resent some of the modern trades'-union restrictions,

may be interested to hear that these old-fashioned "cutlers" made it

a punishable offence for work to be done at all for several weeks

during a certain period of the year. Eight or ten years of

apprenticeship were required. Each apprentice lived with his master,

who fed and clothed him, and gave him six weeks' holiday annually,

to attend "ye writing school." During this long apprenticeship,

there was no salary beyond a trifling yearly present.

The wives of the Sheffield masters were called "dames," and made all

social and domestic arrangements for the 'prentices, and, indeed,

they seem to have fulfilled many of the conditions of Solomon's wise

women. There has been a Sheffield saying that there have been no

good doings since so many fine mistresses came into fashion, and the

good old dames were supplanted. Their domestic value seems to have

earned a recognition it does not always receive, and they were not

ignored in other relations. Once, when the master cutler gave

festivity to his brethren, his wife followed it up with festivity

for the ladies. On one occasion, the "beadle" of the Company was a

woman. And the Company carefully guarded the interests of women, by

its concession known as "The Widow's Right," now we understand in

process of extinction.

The "Sheffield Grinders" have been a class by themselves. Elliott

drew one from the life:―

|

"Born to die young, he fears nor man or death;

Scorning the future, what he earns he spends.

Debauch and riot are his bosom friends.

. . . Full many a lordly freak, by night, by day,

Illustrates gloriously his lawless sway.

Behold his failings! He hath virtues, too:

He is no pauper, blackguard though he be;

Full well he knows what minds combined can do—

Full well maintains his birthright—he is free!" |

At one time, the conditions of grinding were such that the grinders

died at the age of twenty-nine. Despite the opposition of the men,

who feared lest any removal of the noxiousness of their work might

introduce more competition and cut down their wages, considerable

improvement has been made, and some of the grinders may now hope at

least to attain middle age. It seems that the "dry grinding"

required for table forks is the deadliest work. We should shudder to

have weapons from a battlefield laid down amid our household meal;

yet, in truth, our household implements seem well-nigh as fatal to

human life!

It struck one oddly, when in Sheffield, to notice how a population

who from time immemorial, even at the cost of their own length of

days, have been welding weapons of war to take the lives of folks

they have never seen, should be themselves of the kindliest and most

hospitable temper, so that it was a pleasure to be a stranger in the

place, and to throw oneself upon the courtesies so readily extended

to one. How well will it be for the world, when the Divine Spirit so

harmonises each man that he will be all of one piece, and will not

stretch out the long arm of gain, to do to those out of his sight

what his own hand would never do to the neighbour at his side.

Sheffield has not been always the wealthy city that it is to-day. About, two hundred years ago, master cutlers, when they had saved

£500, retired from business and took to farming. In 1794, the

common wage of a journeyman cutler was two shillings a day, a few

superior workmen earning three. But, in those days, meat was only

threepence or fourpence per pound, and other necessary commodities

were cheap in proportion.

Sheffield stands on so hilly a site that it has a somewhat irregular

appearance. Many handsome buildings have been lately erected, and

these, towering over low old houses, or beside still vacant "lots,"

somewhat remind a travelled visitor of certain colonial cities such

as Ottawa. Some of the lower parts of the town are very squalid and

gloomy. The old parish church, which dates from 1154, but was

thoroughly restored and enlarged in 1880, would be very handsome

could its architecture be appreciated under the blackness with which

the local atmosphere has clothed it.

Sheffield stands on so hilly a site that it has a somewhat irregular

appearance. Many handsome buildings have been lately erected, and

these, towering over low old houses, or beside still vacant "lots,"

somewhat remind a travelled visitor of certain colonial cities such

as Ottawa. Some of the lower parts of the town are very squalid and

gloomy. The old parish church, which dates from 1154, but was

thoroughly restored and enlarged in 1880, would be very handsome

could its architecture be appreciated under the blackness with which

the local atmosphere has clothed it.

This church has two quaint stories about it. One, that a girl,

falling asleep during service, awoke to find herself deserted and

locked in. Her imprisonment might have lasted for days, had she not

hit on the clever device of arresting the swinging pendulum of the

clock, stopping it, and thus calling attention to the building and

its prisoner.

The other story has in it an element of mystery and pathos. It

concerns a blank and broken tombstone, which may be noticed near the

vestry door, and has long been a favourite leaping place for the

Sheffield boys. It appears that long, long ago, an unknown visitor

arrived at an inn in Sheffield High Street. He went to his bedroom. In this chamber there was an unused door-window opening straight

upon the yard. It had been accidentally left unbolted. The stranger

opened it, and, believing he was stepping into a passage, fell on

the stones below and was killed on the spot. In those days, when

communication over the country was slow and difficult, his identity

was never discovered, and doubtless there were those who watched for

him for years—and may have even felt bitter doubts of him when he

"came not back." As he had a considerable sum with him, he was

handsomely buried; but it is believed that his tombstone got cracked

in a thievish effort to move it, owing in to a report that some of

his gold had been interred with his corpse.

Most of the other numerous churches and places of worship in

Sheffield have been built within the last fifty years. The preaching

of John Wesley and his earlier followers, gave an immense impetus to

the spiritual life of Sheffield. Several of the latter "testified"

there, not only with their lips, but by the meekness and courage

with which they endured persecution. One of them had a bucket of

bullock's blood thrown over him as he walked through the street in

his best clothes. Wesley himself is known to have paid thirty-two

distinct visits to Sheffield, though others may not have been

recorded. Of Norfolk Street Chapel it is recorded that "John Wesley

preached for the first time in the Newhouse on 30th June, 1780." It

is believed that his latest surviving hearer died as recently as

1873.

Sheffield, despite its smoke and squalor is in many ways a specially

well-equipped city. It has six parks, one of them given by Mark

Firth, also the founder of Firth College, designed to provide

university training for many who could not otherwise enjoy it. In

another, Weston Park, is the noble picture gallery presented and

equipped by the Mappins, containing many masterpieces among its

permanent treasures, and offering houseroom to a succession of loan

collections of high type. Incorporated with this gallery is a museum

of old pottery, and local natural history, industries, and

antiquities—the collection being large enough to be varied and

interesting, while not so large as to be overwhelming. On the

afternoon of our visit, we found many visitors, nearly all of the

working class.

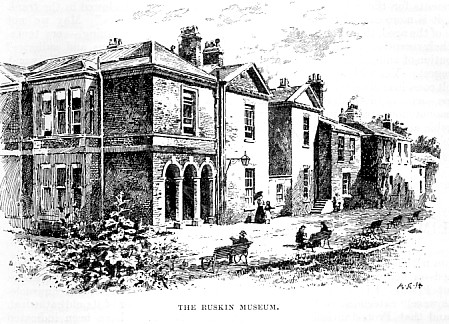

A two miles' journey through small streets with wooden shuttered

parlour windows, or low rows of humble shops, brings us to the

pleasantly-wooded and undulated Meersbrook Park, with the quaint

buildings which house the "Ruskin Museum" which the St. George's

Guild has loaned to Sheffield for twenty years from 1890. This

museum is intended as a type of the collections which Mr. Ruskin

desires to see established throughout the country for studious

culture of all that is noble in art and beautiful in nature. He

considers that such local educational museums are necessary to train

the people to appreciate the unique treasures of any worthy national

collection. As it is also his wise opinion that "a collection should

never be increased to its own confusion," only a limited number of

examples—especially of art objects—are on view at a time. The

collection includes rare minerals, a collection of exquisite

drawings in natural history, casts taken by Mr. Ruskin in Venice and

Rouen, architectural studies, rare editions of classical literature,

engravings after Turner, magnificent illuminated ancient

manuscripts, and fine Greek and English coins.

Sheffield has many excellent educational institutions, its Grammar

School dating from 1604. Its Band of Hope Union comprises 160

societies, and its Sunday School Union has on its roll 32,000

scholars. It has learned societies of every form, and a free library

which in its two departments contains nearly 50,000 books. It has

institutions for the relief of every form of physical suffering, and

with all these arrangements for the needs of the future and the

present, it is more careful than are many cities of the claims of

the agèd, there being several establishments for their reception and

other endowments for the distribution of annuities.

One left Sheffield with regret. Yet with all its industry and

wealth, one felt conscious of deterioration and loss when one

came—as one often did—in the midst of some mean monotonous street,

upon an old thatched or tiled gable and a few gnarled trees bearing

mute witness to the vanished times of the old world masters, and of

rural life. One cannot bring oneself to accept to-day's smoke and

ugliness as finalities. They must be but part of a process evolving

some beauty and order not yet apparent, unless indeed foreshadowed

in the frank warm-heartedness of the "folks." May we not see this new

order already beginning—very tentatively—in the parks and museums

and galleries? Dare we hope that we have at last seen the worst of

our factory and furnace towns, and that henceforth, the science and

invention and enterprise whose progress has made them what they now

are, will turn attention to making them all they should be?

ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO.

――――♦――――

THE STORIES OF FAMOUS SONGS.

(The GIRL'S OWN

PAPER, June, 1888.)

T has been aptly said that "the making

of the song of a people is a happy accident. . . . It must be the

result of fiery feeling long confined, and suddenly finding vent in

burning words or moving strains. Great national lyric is the

result of the conjunction of the hour and the man."

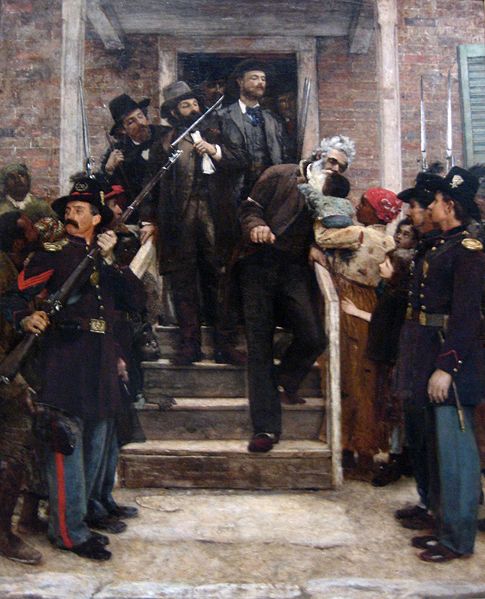

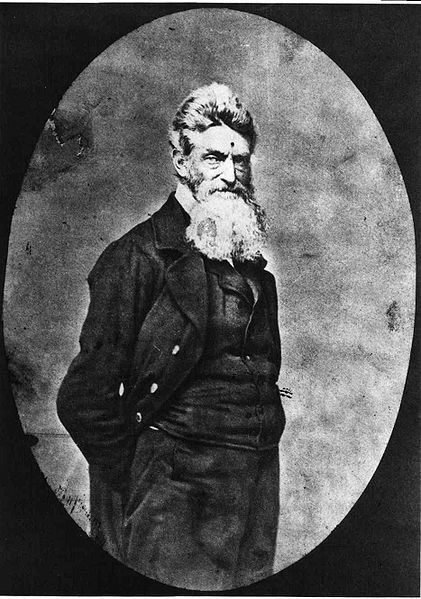

There is no better illustration of this than the popular

American war song, "John Brown's Body." There is literally

nobody who claims its authorship. Words and tune "grew"

together in the early days of that great war between the Northern

and the Southern States which settled the question of American

slavery for ever.

Yet there is no song which has a better story to tell.

And as there is seldom any historical period so misty to our minds

as that which immediately precedes the date of our own personal

histories, we are sure that there are many girls who will thank us

for a glimpse of the heroism and romance which wrought out a great

national drama in the days when their fathers and mothers were the

young folks of the world.

We are not ambitious enough to attempt any history of the

rise and development of slavery in the United States of America.

We shall only attempt to set forth, as simply as we can, a few facts

necessary to explain its existence and the varying influences that

surrounded it, and that finally brought about its extinction.

Let it suffice to say that slavery—that supreme crime against

humanity—originated in the States when they were a British colony.

Therefore, the worst indictment we have any right to bring against

them in this matter is, that they did not all come to a full

realisation of the heinousness of this evil quite so soon as did the

mother country.

Now, at the very outset of this paper we must caution our

readers against an error which we would not imagine could be fallen

into by educated people, had we not proved it to be so. They

must realise at once that the Northern and Southern States are alike

in North America, different parts of the Republic of the United

States. These have nothing whatever to do with the continent

of South America, with all its varying empires and republics, mostly

Spanish in origin and development. We should have thought such

a caution quite unnecessary, had we not heard a friend from Buenos

Ayres being constantly asked "Whether the party feeling between the

Northern and Southern States had now entirely passed away?"—the

questioners being presumably educated people and filling respectable

and indeed honourable positions in British society.

Having explained this much, we may go on to say that from the

earliest days of the British colonisation of North America a vital

difference arose between those States called the Northern and those

afterwards grouped as the Southern.

The Northern States were founded by "The Pilgrim Fathers,"

who were themselves exiles from Britain for the sake of civil and

religious freedom. In the communities under their influence

certain religious and political theories were made of the first

importance from the very beginning. They started on the path

of moral progress, though the struggle for existence and the greed

for material wealth soon entered in, to warp the nobler aims.

The Southern States, on the other hand, were colonised by

aristocratic English adventurers, often of high character and

courtly manners, but whose first aim was the profit and comfort of

their immediate followers, without any special sense of

responsibility towards the community at large. Thus in these

Southern States a wide gulf soon yawned between the upper and lower

classes. "Below the great landholders came a population

largely tainted with pauperism and crime." Further, the

development of the natural resources of these Southern States

required masses of specially cheap labour.

How was this to be supplied?

At first, the forced labour was of white people, "criminals,

beggars and vagrants" being transported there from the mother

country. Orphan or friendless children became the victims of

family cruelty or mercenary greed. But still the supply was

insufficient for the demand.

Then these our colonies in the Southern States resolved to

follow the example of our colonies in the West Indies, and to

encourage the importation of negroes. The first shipload was

landed in 1620, at Jamestown. In 1662, the Royal African

company was incorporated, with the English King Charles II. and his

brother as its chief directors, its main business to be the

exportation of negroes from Africa to slavery in the plantations.

The black slave soon supplanted not only the white bondservant, but

the white labourer of every kind. The Southern States became

the home of a white aristocracy, a black slavery, and a desperate

ruffiandom.

In 1772, a slave named Somerset, brought to England by his

master, was, on account of ill-health, turned adrift. When,

through the charity of Mr. Granville Sharp, he was restored to

health, his master again claimed him. A suit resulted, which,

mainly owing to the energy and determination of Mr. Sharp, ended in

a decision that slavery could not exist in Great Britain.

Owing to the revolt against sundry British impositions, the

United States declared their independence of Britain in 1776.

They were recognised internationally as a distinct Government in

1783; and in 1787, the American Congress passed an unalterable

article forbidding slavery in that part of their territory

north-west of the Ohio. This put the Northern States on the

same footing that Great Britain had already attained, while slavery

still persisted in the Southern States of the Republic as it did in

those West Indian colonies which remained in British possession.

Slavery finally terminated in all British possessions between

the years 1833 and 1838. Its extinction cost the British

nation £20,000,000.

It still lingered in the Southern States of America, and in

its most frightful form. In the slavery of the antique world

the masters had been content with the possession of their human

chattels, often employed as tutors and guardians, and frequently

attaining high rank in philosophy and learning. In Oriental

slavery there had been hope. The slave to-day was often Grand

Vizier to-morrow. But in America they sought to deprive the

human chattel of mind, soul, and affection. To educate him was

penal. He could have no family ties. The Courts of

Justice were closed against him, and the curse of slavery pursued

the least drop of African blood, however diluted it might be with

that of the ruling race.

The advocates of slavery had two or three arguments on which

they laid great stress. One was that the slave in the Southern

States was generally well-treated and content, in evidence of which

they told stories of domestic attachments, and brought forward his

merry plantation songs. Of course, it would be going too far

to say that the large majority of slaves were treated with personal

violence and cruelty. They were only entirely at the mercy of

their master pro tem., and away from the kindest owner they

might be sold any day, either at his own will, or at the will of any

creditors or trustees into whose hands he chanced to fall.

Among the women, wifehood and motherhood were only other names for

shame and agony. It was the cruellest wrong of all if they

were kept in such a low condition as to be unable to realise all the

bitterness of their lot. But that many of them did escape this

crowning ignominy is proved by the wildly pathetic hymns in which

they cried out to God for His help and support.

Another Southern argument was, that the Northerner, though

not a slave-holder, held the negro in such bitter contempt and

abhorrence, that his free life in the Northern States was lacking in

many of the alleviations which he often found in his Southern

slavery. There is no denying this indictment. But

neither do two wrongs added together amount to one right! In

excuse of the Northerner, it can be pleaded that this savage nation

had been poured upon his country, not for his benefit, but for the

interests of his Southern brother; that the negro was a portentous

appearance in those States where white labour abounded, and

competition was already fierce enough. Furthermore, the negro

stood to the Northerner as the outward and visible sign of the

Northerner's own subjection. For Southern voices were

predominant in the councils of the nation, and it was mainly

through, and for slavery, that such predominance was jealously

maintained.

On the side of the North we may justly urge, that whatever

might be popular prejudices, it was in her States, and under

influences that had made her what she was, that all true and loving

help for the slave originated; the voices of the North were ever on

the side of freedom. We all know Longfellow's "Poems on

Slavery." Perhaps not quite so many of us are equally familiar

with those of John Greenleaf Whittier, the American Quaker poet,

who, like so many of his sect, threw himself heart and soul into the

cause of the slave. It is characteristic of the man, and his

deathless faith and hope, that he called his outpourings "The Voices

of Freedom." One of the best known of these is "The

Christian Slave," founded on an incident at a slave auction in New

Orleans, where the auctioneer recommended the woman under the hammer

as "a good Christian." The indignant poet breaks forth:

|

"My God! can such things be?