|

THE

DOMESTIC NOVEL

As represented by Jane Austen.

By EDWARD GARRETT.

(From: Atalanta: The

Victorian Magazine, 1893.)

JANE

AUSTEN has never been a widely "popular" author. In her own day, her

work made neither fame nor profit, though it was speedily

appreciated by such judges as Walter

Scott, Southey, Coleridge, Archbishop Whately, and Lord Macaulay.

The latter, be it noted, set her down as second in rank only to

Shakespeare. Her fame has this true test of genuineness, that it has

been slow of growth, and that it is still growing. It may be

interesting to study the secret of her strength and excellence.

We must first consider what she was in herself. She was a young

woman of the upper class, in circumstances of easy affluence. She

never married, but there is no streak of real tragedy or romance

visible in the scanty materials of her biography. Her strongest

personal attachment seems to have been to her elder sister

Cassandra, and one traces this sisterly affection in the attachment

between her "Elizabeth" and "Jane Bennett," her "Elinor and Marianne

Dashwood," even in the bond which so readily forms between "Fanny

Price" and her sister. Nearly all Jane Austen's known correspondence

is what passed between herself and this beloved Cassandra during

their brief separations. These letters reveal the life in which she

lived--a life of happy household affection, petty neighbourly

interests, and the "genteel" diversions of the day, balls, routs,

and

country-house visiting. It is often hard to believe that her letters

are not chapters from novels! One can scarcely tell whether she is

writing about the movement of her living acquaintances or of her

"characters."

Letters and novels alike display fine insight into character, and a

humorous perception of its intricacies. We may note that in her

letters, Jane Austen occasionally allows herself a more cynical tone

than she would put directly into the mouths of her own favourite

heroines. This flavour of cynicism, though it certainly appears in

the novels, is created there rather by the skilful way in which the

characters are played off one upon another, or by the wonderful

little sentences, so few and far between, wherein the authoress

herself plays the part of the Greek chorus, and also occasionally by

the utterances of characters not on the heroine-level. Thus in

"Mansfield Park " it is not Fanny Price, but Mary Crawford, who

says, "We seemed very glad to see each other, and I do really think

we were a little!"—a sentence which might have come out of one of

Miss Austen's own letters, abounding as they do in such remarks as,

"We have been very gay since I wrote last; dining at Nackington,

returning by moonlight, and everything quite in moonlight,

everything style, not to mention Mr. Claringbould's funeral, which

we saw go by on Sunday;" or, again, "I rather wish the Lefroys may

have the curacy. It would be an amusement to Mary to superintend

their household management, and abuse them for expense, especially

as Mrs. L―― means to advise them to

put their washing out;" or, once more, "Fanny Austen's match is

quite news, and I am sorry she has behaved so ill. There is

some comfort to us in her misconduct, that we have not a

congratulatory letter to write."

The first thing that strikes us about Jane Austen is that she

(in this particular like the otherwise widely dissimilar Tolstoi of

our own time) wrote only of what she really knew. Her scenes

are laid in the country towns and watering places and London visits,

which made the surroundings of her own life. Her characters

are chosen from the country gentry, and the clerical, naval, and

military circles in which she was familiar. On the margin are

one or two "city people," or yeoman farmers like poor Robert Martin

in "Emma." Her little section of the world is sharply focussed

in her pages (as in her letters). The rest remains in the

outer darkness, as if it did not exist. There may he 'poor'

without individuality who are 'visited,' and who receive doles of

tea, sugar, and flannel, or who bully young ladies in country lanes,

as when Churchill overtakes Harriet on the Richmond Road. The

'church' is regarded as a conveniently profitable and genteel

calling for younger sons of the steadier sort. Henry Tilney,

Edmund Bertram, and Edward Ferraris, are all clergymen. They

dance, hunt, and flirt as if these made the whole of life.

Edmund is in love, in a way, with Mary Crawford and Fanny Price,

both at once. Edward Ferraris is in love with Elinor Dashwood

while he is engaged to Lucy Steele. When he gets a living, the

items concerning it which are summed up as worthy of interest, are

the state of the house, garden and glebe, extent of the parish,

condition of the land and rate of the tithes! Oft Austen, in

her own person, had no view of ministerial duty which could prevent

her from describing its discharge by the coined verb, "to clergy!"

She lived and wrote in stirring times. The Napoleonic wars

were going on, Nelson conquered and died, the slave trade was

abolished, the war of American Independence separated the United

States from Great Britain, the battle of Waterloo was fought.

But no trace of any influence from these events is to be found in

her books (save that some of the families are a little disturbed in

their West Indian properties, or some of the naval or military

youths obtain promotion), nor yet in Jane's own letters, except by

such slight references as to Southey's "Life of Nelson." "I am

tired of Lives of Nelson, being that I never read any. I will

read this, however, if Frank is mentioned in it." ("Frank"

being her brother.) There are some pretty but very slight

vignettes of English scenery in the stories. No animals cross

their pages, save horses for riding or driving. Nor do we find

any "pets" mentioned in her letters.

All of Jane Austens's stories end "happily." That is to

say, all "entanglements" are cleared away, financial arrangements

drop into right condition, and the heroine gets married to the

hero—and all this in a fashion quite inconsistent with the sternly

truthful tone of the preceding story. We know that no such

endings are true to real life, where the right people will often go

on and marry the wrongs ones, and where character persists in spite

of matrimony! All this was but Jane Austen's concession to

convention, and was, perhaps, made the more easily because no iron

ever seems to have entered into her soul, to impress her with life's

deeper problems and perplexities!

What we have hitherto said only serves to show that Jane

Austen put on her canvas but a small section of the world's life,

and to most eyes a common-place and uninteresting section. She

was entirely and frankly limited by the social customs, conventions,

and ways of life and thought around her, so that her pictures of

these are already of almost antiquarian interest. Yet her fame

is growing! In what, then, does her greatness consist?

It consists in her insight into human character. Her

range of human life might be small, but her knowledge of human

nature was boundless. She likened her own work to miniature

painting "with so fine a brush as produces little effect after so

much labour." But then each miniature is a matchless portrait,

and as we know, it takes greater skill to bring out individuality in

such a delicate and tiny scale, especially when, to coarser visions,

there might seem a general resemblance in the faces of the subjects,

even as in their garb! It is comparatively easy to draw

angels, because, as nobody has seen one, the likeness cannot be

questioned, or monsters, because if one has not seen the like, he

still cannot absolutely deny that they may exist. Take for

instance, Dickens' "Quilp." I remember once, many years ago,

venturing to suggest that he was an exaggeration, when a lady in the

company silenced me by the remark that she knew such a man—he had

been her own husband! But even that singular testimonial to

reality cannot give "Quilp" more than a purely pathological value.

He is in the scheme of human life only as are "the Siamese twins,"

or "the living skeleton." There are no "Quilps" among Jane

Austen's characters. We have all known every one of them—which

simply means that we have all known some of the faces which go to

make up the wonderful "composite" with which she presents us.

We are not to confound this marvellous faculty of true

presentation, with mere observation, or with what is called "drawing

from the life." These are part of it, but it is more than

these. Observation is worth very little unless we know what to

observe, and how to co-relate our observations. And when all

that can be said of any character-drawing is that it is "a study

from the life" it has probably seized only the accidental and not

the essential, and is apt to be as valueless as those awful amateur

photographs which "must be like, you know," but which simply cannot

be identified by the uninitiated!

Observation is of slight value, unless it accompanies such a

grasp of character as will enable the portrayer not merely to depict

words and actions which have been heard and seen, but also to

predicate words which would be spoken and the line of conduct which

would be pursued by the subject of the portraiture on any given

occasion or under any imaginable pressure. As it was said that

if a bone was given to Sir Richard Owen, he could construct the

animal to which it belonged, so a phrase or an action becomes to the

seeing eye, the revelation of a whole character—the prophecy of a

complete history.

It is almost impossible to point out special instances of

Jane Austen's faculty in this wise, because her books are simply

compact with them. If, in explanation of what we have said, we

indicate a few scenes for our readers' special consideration, it is

not that they excel thousands of others, but simply that they

suffice to serve our purpose.

Take the wonderfully drawn characters of "Mr. and Mrs. John

Dashwood" in "Sense and Sensibility." It is little likely

indeed that Jane Austin had ever heard such a dialogue as she

reports in Chapter II. But she had observed the tendency of

human nature to minimize its "good intentions" when brought to the

point of fulfilment, and to yield to influences which sway it in the

direction of its own worst tendencies. And again, in Chapter

XVII., how pithily the few remarks between Elinor and Marianne

concerning "competence" and "wealth," set forth the perpetual trap

into which plain people fall if they do not carefully insist that

their gushing controverters shall explain their terms!

The Steele girls are life-like presentments of inbred

vulgarity. In "Northanger Abbey," how the

shallowness—entailing falseness—of Isabella Thorpe's character is

revealed by dainty touches in the conversation between her and

Catherine in Chapter Vl., and again where they meet at the theatre.

How inimitable is that young lady's championship of "Miss Andrews."

"The men think us incapable of real friendship, you know and I am

determined to show them the difference . . . You have so much

animation, which is exactly what Miss Andrews wants; for I must

confess there is something amazingly insipid about her." How

John Thorpe makes himself known to us, uttering contradictory

commonplaces with conceited dogmatism, and shining especially as a

literary critic! And how consonant with this introduction is

the part he plays in the story, whose very simple plot hinges on his

wild assertions and retractions!

"Pride and Prejudice" is one of the best of Jane Austen's

novels. Elizabeth Bennett, with her quiet good sense, is a

delightful heroine, with Jane for a pleasant second, and the other

Bennett girls for foils. The mother's "extraordinary

ordinariness" often rises to sublimity!—as, when eagerly pressing

forward the marriage of her runaway Lydia, she pauses in all her

agitation, to think of Lydia's clothes and to reflect that Lydia

does not know the best warehouses!

Mr. Collins, the young clergyman, is made to show himself

exactly as he is, unctuous, pragmatic, and underbred, and this

without any suspicion of caricature! His enjoyment of Lady

Catherine's offensive patronage, as set forth in Chapter XIV., is

delightfully realistic, as is his proposal to Elizabeth in Chapter

XIX., and his sententious and selfish moralities throughout.

Quiet, cool Mr. Bennett, who is aware he has married a fool, and

that against stupidity even the gods fight in vain, is very

skilfully depicted. The studied rudeness of a fine lady is

well brought out when Lady Catherine first appears in Chapter XXIX.,

and critics particularly admire Chapter LVI.,—calling the scene

between Lady Catherine and Elizabeth "delicious and inimitable."

There is much exquisite character-drawing in "Mansfield

Park." Every scene in which Mrs. Norris appears is worthy of

careful study. More vividly than any sermon could, does the

episode of the private theatricals show the force of frivolity and

persistence in wearing away better principles. The three

sisters, Lady Bertram, Mrs. Norris, and Mrs. Price, all equally

self-engrossed, though in such different fashion, are very well

brought out. Fanny Price herself, with all her sweetness and

docility, has plenty of sense and spirit, which evidently develop in

the suffering caused by Edmund's devotion to Miss Crawford, and

which we cannot help half hoping may some day prove the Nemesis of

that infatuation!

"Emma" seems to us the least attractive of Miss Austen's

books. Emma herself is a charming study, but only because she

is so naively conceited, so frankly puffed up with her own wisdom!

She can be so unkind to poor Miss Bates, so unjust to worthy Robert

Martin. Her father, so kindly a gentleman, in all his

valetudinarianism, is a delicate triumph of skill. Miss Bates

herself is a delightful compound of sweetness of nature, muddle-headness,

and volubility.

"Persuasion" has a great charm. It was Jane Austen's

last book. Her own youth had passed away, she was in the

trying days of early middle life, the very hand of death was upon

her, when she wrote it. Anne, gentle, refined Anne, is

described in two words "only Anne,"―that

is all she is to those for whom she had sacrificed her love and

surrendered her will. "She had been forced into prudence in

her youth, she learned romance as she grew older," and such a nature

and history is well set off between her two sisters, the hard and

haughty spinster and the selfish, narrow-minded young married woman,

living in perpetual friction with her mother-in-law. Chapter

X. is full of pathos, only deepened by the severe reserve of its

expression. It makes us feel as tired as Anne herself―the

tiredness of a sad heart. Very subtle is Anne's secret

reflection, in the following chapter, that the much-pitied Captain

Renwick "has not a more sorrowing heart than I have; I cannot

believe his prospects so blighted for ever. He is younger than

I am, younger in feeling; younger as a man." And what deep

reading of the human heart is in the little incident when Anne's

alienated lover, Captain Wentworth, notices a stranger's casual

admiration of her, and straightway turning to look at her, sees

"something like Anne Elliott again."

All this is observation, but it is imagination too, and that

deep insight born of the sympathy which can project itself not only

into others' circumstances, but into their very natures.

Jane Austen's knowledge of the human heart was positively

uncanny for a woman so young and so fortunately placed. She

was undoubtedly cynical. There are no signs of tenderness in

her letters, and but few in her books. Even in "Persuasion,"

she can actually raise a smile at a matron's "fat sighs" over her

worthless dead son! Yet, as Lord Brabourne says, her works

"make virtue lovely and vice the reverse . . . Without ever

preaching to us, they continually impress upon our minds lessons of

a purifying and elevating tendency. The different motives

which influence men and women in various circumstances of life—the

special faults which beset certain natures; the effects those faults

produce upon others . . . all these are drawn by the master hand of

a great artist."

It is worth noting that one of the last utterances Jane

Austell put into the mouth of her latest and meekest heroine is an

expression of belief "that a strong sense of duty is no bad part of

a woman's portion."

―――♦―――

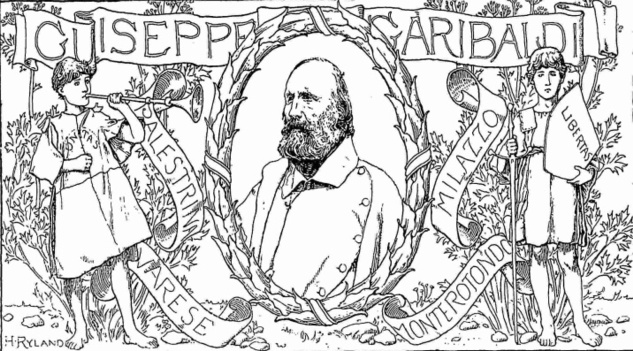

GARIBALDI IN LONDON.

BY

ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO.

(From: Atalanta: The Victorian Magazine,

1894.)

THERE are few historic periods

which are to us so misty and indistinct as those just beyond the

reach of our own memories. In general, we know far more about the

Norman Conquest, or the Plantagenet or Tudor dynasties, than we know

of the sequence and significance of events occurring within the twenty-five

years before own existence. One finds that, by the time one

approaches middle life, one can occasionally make oneself quire interesting to

younger people, by relating personal recollections of striking

incidents of famous personages, and telling their story to those who

find them so new and fresh, though they are so familiar to their

elders!

What meaning can most readers of ATLANTA attach

date, April 11th, 1864? Yet what a day that was in London, ay, and in all Great

Britain—a day when the heart of the whole land went forth to welcome a

man of the grand antique type—"one of Plutarch's men," as he has

been aptly called—Giuseppe Garibaldi the "Liberator" of Italy.

He had been a great conqueror, a man before whom a kingdom had

fallen like a house of cards. But it was not as a conqueror only that we

thought of him—indeed, by that time he was no conqueror, but a

defeated and wounded man. A touch of chivalric tenderness saved our

admiration from my suspicion of vulgarly. His past militancy

glories served but as the pedestal on which to raise him high enough for us to see the simple grace and dignity, the sterling

worth,

of the man himself.

The young people of to-day can scarcely realise the time when the

name of "Italy" conjured up thoughts of dungeons and exiles, and

cruel deaths by swift execution or slow tortured. Indeed, there was no "Italy" in those days. "Italy"—but the dream in which

patriots and poets foresaw the fusion of the little states and

kingdoms in which their beautiful country, "the Juliet of the

nations," lay divided, with foreign armies

occupying well nigh all her classic cities. We used to see the

Italian exile in our streets, and to note the gentle music of their

voices. After the attempted revolution of 1848 there were crowds of

them—grave, stately folk they generally were, easily to be

discriminated from the more voluble refugees from France. Quiet,

law-abiding people they appeared to be, only now and again a

terrible assassination of some unknown foreigner seemed to denote that

the last dread penalty had been exacted from some traitor to one of those

"secrete societies" which ramified the Italian nations at home or

in exile. Nearly every schoolgirl of those days had at least heard

of the poet

Silvio Pellico and his pathetic book, "In my Prison," the

record of his ten years' solitary confinement in the dungeons of Venice

and Spielberg. The British Government itself had protested

against the King of

Naples' barbarous treatment of political prisoners. London had

witnessed the jubilation of its Italian residents, when the patriot

Poerio, with 66 companions—released after years of miserable

confinement, only to be deported to South America—siezed the vessel

in which they were voyaging, and brought her triumphantly into

British waters and freedom.

This was in 1859. In the following year, the history of modern Italy

began. But we are not to attempt its formal recapitulation here.

"Italia Unita!" was the battle cry of this revolution, and the

statesman Cavour was its brain, and the hero Garibaldi was its arm. Its history reads like

a chapter from Tacitus. Think of Garibaldi with

his "thousand heroes," landing at Marsala, marching on to Naples

and driving in his open carriage right under the guns of the royal

fort!

Some of us may have heard the Rev. Mr. Haweis tell the

story of that

scene—how there was a sort of awful suspense—would the royal troops be

true to their master, or to their country? General Garibaldi was

face to face with magical victory or certain death. He rose in

his carriage, and, looking straight up at the enemies' guns, in

stentorian tones he bade his coachman "Drive slower!"—and yet again,

"Slower still!" And then the

ringing cheers broke from the Neapolitan troops-and the kingdom

passed from cruel Bomba's son and his poor young Bavarian queen.

Think of that other scene, when, victory following victory,

Garibaldi met the patriot King of Sardinia, and hailed him "King of

Italy," while the other acknowledged the power of "the Kingmaker" by

the simple words—"I thank you."

Alas! alas! the virtue of gratitude, and of loyal support to those

whose past services merit it, are at least as rare among nations as

among individuals! Garibaldi could not rest until the whole of

Italy was made one. The new Italian government—the government which

owed its very existence to his efforts—by its vacillating policies first encouraged him to

make onslaught on the Papal States; and then,

probably in fear of provoking the

hostility of the Emperor of the French, actually sent troops against

him, engaged him in conflict, wounded him (so that ever afterwards

he was lame), and took him prisoner!

And that was the last of his public life, before he — to us on that

April day!

It was such a beautiful day. April is often one of the

happiest months in London. The great city has brushed aside her

winter gloom and dust, and is prinking herself for her "season." The budding

trees are fresh and green, not yet scorched and wilted. And the

London of 1864 was not quite the London of today. True, it could

not boast its noble embankment by the river, but it was then full of

quaint corners, which have since been invaded by railway stations and

monster hotels. The air, too, seemed purer and sweeter—there was no

"underground" in those days to belch forth sulphurous vapours.

There had been no formal preparation for Garibaldi's entranced into

London. He was to be received by some private friends connected with

the City Corporation, and he was to be the guest of the Duke of

Sutherland at that Stafford House which the Queen is said to have

called "a palace." During the day before the General's arrival, some

people in the suburbs, hearing that seats where to be for letting

on the line of route, laughed the idea to scorn, and suggested that

very low fees would suffice!

Garibaldi was expected to reach the West-End in the early

afternoon. Full of ardent girlish enthusiasm, I and a companion

started forth in very good time to secure a coign of vantage. But

where should we find it? Charing Cross was one densely packed mass of

humanity. We managed to push our way through wide Cocksure Street. Pall-Mall we found well nigh impassable, so we skirted it by back

by-ways, turning into it again and again to see if prospects were

more hopeful. In vain. There were few flags and little decorations to

be seen; but the fronts of the houses were all crowded, save one or

two of the most fashionable clubs, whose members stood about at the

windows in pairs, with slightly discontented countenance, while the

appearance of some unpopular politician elicited an occasioned

expressions of disapprobation, or a jeer from the crowd.

I suppose there must have been policemen in that crowd, but

certainly they were so little in evidenced that I do not remember

them as one of its features. Yet the multitude was of that vast,

dense character which is often supposed to require the control of

cavalry. The people filled the roadways as well as the pavements,

standing about without any pretence of forming line. Carriage

traffic seemed wholly suspended.

But the crowd itself was so wonderful. The "rough" element seemed

entirely absent: it was evident that the interest of the occasion

appealed to another set. There were a great many men and women of

the higher artisan class, who must have snatched their holiday only at some

cost. Everybody looked neat and respectable. Hour after hour passed, yet

all remained cheerful and orderly in their long patience. Faces were

shining with enthusiasm. Friends talked eagerly together. Even

stranger exchanged confidences. "A touch of high emotion" was on us

all.

|

"It was a sight for sin, and wrong.

And slavish cranny to see—

A sight to make our faith more pure and strong

In high humanity." |

The romantic nerve which runs in the hardest nature was a-thrill in all of

us.

At last we found a place where we could stand at our ease. The line

of route did not seem to be quite surely ascertained, and some

people had doubts whether it comprised this corner, so that there was

room for us.

We stood there for hours, content that, though we might not see very

well, we should yet see something. I remember the drift of our

conversation:

it was doubtless a fair type of much of the talk going on in that

vast crowd. We talked about the hardy rearing this great man had

had in his fisher-father's home in Genoa. It was not till years

afterwards that I saw the portraits of his mother—a noble,

severe-looking old dame, doubtless a strict disciplinarian, and true

and staunch to the backbone, such a woman as we may readily find

among "grave livers" in the Scotland even of to day.

We spoke of Garibaldi's adventurous youth—his energies ever thrown

into the scale against tyranny wherever he found it—of his impetuous

wooing of the beautiful Anita de Silva, who, alas! broke her

engagement with an earlier lover for the sake of this bold

bridegroom. It is not every day that a Giuseppe Garibaldi comes to

woo, and who knows may have been the strange magnetic attraction

possessed by this man, who could dare

to "drive slower" in he face of a presumably hostile garrison? Pity

poor Anita in her short, sweet, stormy, married life, nursing her

little ones, and then surrendering them to her husband's mother, and

sharing all his dangers in the blighted revolution of 1849, until that

day of flight and misery, when heart and strength failed her, and

she lay down and died, and was buried by strangers in a brave which

nobody knows, on the shores of

the Adriatic. Pity her the more, because all the tragedy of her

romantic love did not save her from the Nemeses of her slighted

faith to her first love. We are told that the bitterest agony of her

last hour was the sense that she was leaving behind him for whom

she had sacrificed all, and was going alone into the spirit land

where her slighted lover, who had died before her, was awaiting

her. Poor Anita!

We waited and waited. The great crowd swayed slowly to and fro. We

all wondered at the delay, and conjectured that it was due to the

unprepared-for warmth of the British welcome.

At last we felt we must wait no longer. It was not that our patience

failed. We had been on our feet for nearly two hours, and we

would have remained to the end, however long it might be postponed. But we knew there were elders at home who would be anxious about us,

and sorrowful and disappointed we took our homeward way, leaving

behind the great crowd, never growing less, but always more.

We had gone a little distance, away down back streets, when a mighty

roar of acclamations announced that the triumphant moment had come

just too late for us! But not too late for us to have earned for ever that

human nature has a passion for hero-worship, and is never so happy

as in yielding to a rapture of reverence and love!

Though we did not see Garibaldi that day, we saw him afterwards, two or three

times, driving to and from the houses of his hosts. There was never

the slightest pomp or formality about his entourage. He sat in his

carriage with twos or three English friends about him. He wore his

famous red shirt, with a grey cloak thrown about his shoulders, and

a small cap on his head, which, however, was generally raised as he

saluted the cheering

crowds which attended him, whenever and wherever went out. In short,

those crowds hung about all day on the pavement outside Stafford

House, and about the area railings of the General's later host—a

Member of Parliament living on the margin of Hyde Park.

|

|

GARIBALDI

(Taken from Good Words, collected

edition, 1882) |

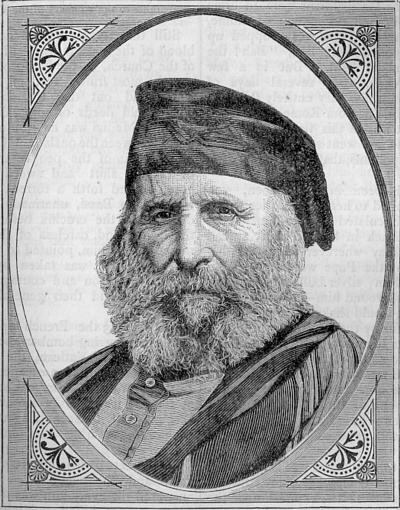

The General's costume, as we have described it, was absolutely

appropriate to the man, and as fit for direct artistic treatment

as was his character for the page of romance and poetry. His face

was

characterised by its

simplicity and good humour. He always looked pleased by the

enthusiasm about him, but his pleasure was as unself-conscious as if

anther had been the object of that enthusiasm. His complexion was

fresh, though his face was lined. His thin hair was of chestnut, softening into silver. His grey eyes beamed with kindliness. His

presence had that ineffable charm that always

attends strength, which is

held at the service of others. "He is like what my father was,"

cried one good daughter, who had had cause to adorer her dead

parent. One felt so about Garibaldi: all his life long he had

probably reminded everybody of what was dearest and best. Yet one

could easily see the fire and force beneath the geniality. The

upright figure and the noble pose of the head, were the of the

spirit within. "He who bends his back too low," said the General,

"may find it hard to straighten it again." He knew no such

temptation!

His two sons had accompanied him to this county. They seldom drove

with him, but generally in a carriages following his. The eldest,

Menotti, had already been the partner of his father's victories, had

been wounded with him at Aspromonte, and had shared his imprisonment. He

was a handsome young man, dark in complexion (it was said he

resembled his mother) and somewhat reserved and severe of aspect. The younger, Ricciotti, who had spent his early life in England,

under the kind care of a lady who had taken compassion on his

motherless infancy, was of a softer type, with the suggestion of a slightly

cynical smile.

The General's daughter Teresa not with her farther in England,

having already (if I remember rightly) become the wife of one of his

officers, Signor Canzio. Those who had seen her at Caprera, her

father's island home, spoke of her as a dignified and fine-looking

damsel, of a grave and thoughtful mien, which can well be believed,

if there was any truth in the story current in society at the

time, that Magin, the sculptor, had modelled his famous "Reading

Girl" from the face and form of Teresa Garibaldi.

The home life at Caprera was always of the simplest and most

wholesome kind. The man who had made a nation had never wasted a

thought on making his own fortune. There were no servants, in the

ordinary sense, at Caprera. The "Kingmaker's" family worked with

their own hands. They got through all their farming and domestic

operations with the assistant of the "friends" who were always

staying with them, for the General's house was never closed to old

comrades. Indeed, his unsuspecting goodness of heart made him an

easy prey to the scheming, the indolent, or the odd.

Travellers

visiting Caper were often unfavourably struck by the appearance of

some of those to whom the great man ungrudgingly dispensed

prolonged hospitalities. When some of Garibaldi's English friends

resolved to present him with a yacht that he might be the more free to

move about or leave his island home, it was mooted that the cost of

the upkeep and manning of the vessel would involve the General in more

expanse than he might like. When this came to the ears of one of his

sons, the young man eagerly explained that there need be no fear that

score: "We will do all the work among ourselves," said he.

Among my memories of that time, though rather later than the

General's visit to England, is a curious little glimpse of the Caper

home, and of "the lives that the women live" in the shadowy

backgrounds of history-making. It was shown in a story told me by Ricciotti

Garibaldi, whom I met in the company of his adoptive

English mother at a quiet little evening party, given in the pretty

Kensington home of a well-known literary man and his better-known wife.

[Ed.―possibly Mr. & Mrs. S. C. Hall

(Anne Maria Fielding)]

In an aside from a general conversation on the many strange things

which lie beyond the philosophy of the merely practical "Horatios"

of Society, Riciotti Garibaldi said that they

had had their own "mystery" at Caprera. One of his

fathers expeditions (he told me which expedition, but my memory will

not be quite positive on that point) had begun, as usual, in the

utmost secrecy. A band of trusted men, many of them old personal friends,

had gathered on the island, and then under the shadow of night had

embarked in little vessel for the mainland. Among these was a youth

whose family had been on the most intimated terms with the

General's, a sister of his being Teresa Garibaldi's special friend. This sister

had accompanied her brother to Caprera, and was to remains there as

Teresa's companion during the dreadful suspense of the expedition.

The embarkation took place—the ship sailed. All was silent and

desolate where recently there had been such excitement. The

two

girls were left in the deserted house without any other companion

than an aged man, who was to serve them in their simple

housekeeping. They got through some dreary hours in the best fashion

they could, and were not sorry to retire to rest. Leaving

their old servitor clearing away their evening meal, the two girls

went off to their sleeping chamber—a room approached from a

corridor, on which opened three or four other dormitories, all empty

and echoing now. The young visitor carrying a light in her hand,

advanced a few steps before the General's daughter, who heard her

utter a sudden exclamation, not of alarm, and then saw her step hastily forwards

and pause. She explained that her bother must have come back, he was

standing at the door of his room, and, as they came in sight, had

retired within. They thought it very strange, but they were quite

used to unexpected comings and goings, and to the need for

secrecy. So they made a brief pause, but, when one or two

gently-uttered callings of the familiar name failed to bring any answer,

a feeling of uneasiness awoke. They went to the room, found the door

still wide open and the apartment empty! The old attendant was

summoned, and a general search made, wholly without result. Uneasiness now gave place to terror and premonitions of evil. The

young visitor was inconsolable. She was sure her bother was killed,

and that, thinking of her in his last moments, he had appeared to her to

break the blow of the sad news. Teresa Garibaldi and the old Italian

refused to take this gloomy view, especially, as the latter sensibly urged,

no real danger was yet incurred by anybody, since no fighting have

could have been begun, for the whole party must be still safely

voyaging through the fine, clear night across the calm waters.

"But for all that," said Ricotta Garibaldi "the first tidings from

the expeditionary party conveyed the news of that young man's death. In the course of some nautical manipulations he had fallen

overboard, and was drowned at the very hour that his sister had

sprung forward to greet his wraith in the corridor of the Caprera

house."

The story itself is one of the type most commons among all those

legends of the unknown world, which we are apt to whisper of "between the

lights." Its only interest is in the place where it occurred and the the

individuals and incidents connected with it. But think of that

lonely house, within sound of the eternal wash of the unresting sea,

and of the two girls, their dear ones all gone, waiting, waiting,

with nothing more to do but wait, and―

|

"Bear to think

You're gone— to feel you may not come—

To heard the door latch stir and clink,

Yet no more you." |

Before men dare to be heroes they must, surely, have heroic women at

home!

General Garibaldi's visit to this country came to a rather abrupt

conclusion. There were perplexities, misgivings. His was an uncomfortable

figure for politicians to find in their narrow and sinuous paths. He not only told simple truths, and nothing but

the truth, but he

told all the truth. He did not understand reserves. In political

life he was as awkward a subject as a plain-spoken school-boy at an

afternoon tea, where the polite people cannot help loving him, even

while they sigh, "Oh dear, dear, what will he say or do next?" That

is about the worst that can be said of General Garibaldi that his

faults were virtues to an extremity. He was a man of action,

not of argument or artifice.

So he came among us and went away. But I feel sure that he, and his

story, and his character, passed through our stifling social

atmosphere like a breeze from the hills blowing down a fœtid

street.

―――♦―――

From . . . .

THE GIRL'S OWN PAPER

12th March, 1898.

WE women are

sometimes sorely tempted to fancy that we have gifts and graces

which have been smothered and stultified by adverse circumstances.

We bewail that we have never got our chance. It is possible

that men are not exempt from this failing, but there are some

reasons why they have less temptation to it. All biography is

full of stories of men who have triumphed over every sort of

obstacle and disability, and a man can scarcely realise any

disadvantages of his own lot, whatever they may be, without

recalling some other man who was strong and brave enough to master

similar drawbacks. Then, again, the difficulties or hindrances

to a man's career are generally of an active nature, so that if

there be any "go" at all in him, he understands at once that they

serve only to test his strength and energy.

But with women there is a difference, less indeed than it

used to be, but still persisting and likely to persist. First,

they have comparatively little biographical guidance. And such

biography of women as there is, deals chiefly with women of high

place and fortune, of rare, adventurous career, or of tragic

eminence of some sort. The peculiar difficulties and

discouragement which beset most of their sex, seldom come much into

such women's lives. Those women's lives whose history,

experience and result would most benefit the majority of their

sisters, remain yet for the most part unwritten.

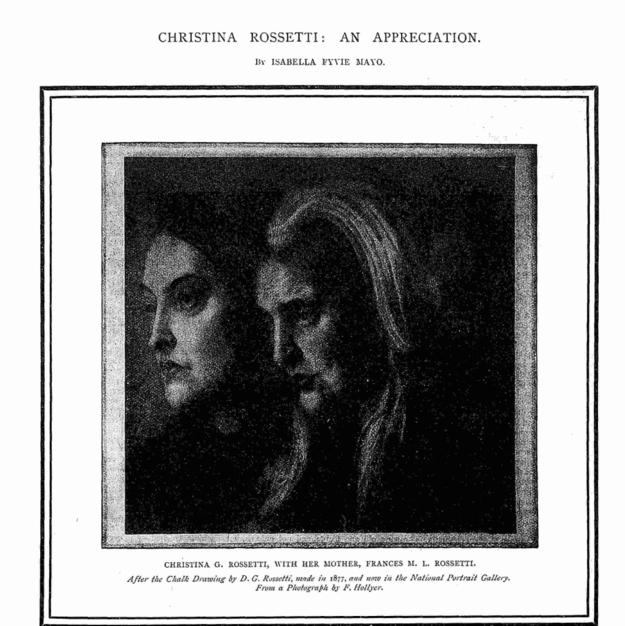

This is why we wish to have a little talk over Christina

Rossetti, the poet who not very long ago passed from us, and whom

the verdict of critics ventures to place in comparison not only with

Jean Ingelow but with Mrs.

Barrett-Browning. For we think the story of her life is one

which may come with peculiar strengthening and comfort to many a

disheartened girl and woman. Yet had she happened to fall even

just below the very high level of poetic power to which she rose, or

had she chanced to lack the one advantage which her life possessed,

it is very likely the world would never have heard a word of her

life's history.

She was born in a prosy, dingy district of Landon, one of the

long uniform streets lying to the south-cast of Regent's Park, and

then as now, the haunt of foreign refugees of every shade of

political opinion. She herself was the daughter of an Italian

refugee, and her mother was the daughter of another Italian, so it

was by right only of her mother's English mother that Christina

Rossetti could claim to be English.

Her father, who gained his livelihood as a teacher of Italian

and who eventually became professor of that language at King's

College, was somewhat of a poet, a great student of Dante, and

altogether a clever and interesting man. Her two brothers, a

little older than herself, have both reached celebrity, the elder of

the two, the poet-painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti attaining great

fame, though he was a man of an unfortunate temperament leading to

an unhappy history.

But from the first, it is evident that the paramount

influence in Christina's life was that of her mother, a woman of

sweet character, but one who, in modern parlance, "did nothing,"

save the housekeeping and mothering of a little household whose

means were at once narrow and precarious.

The little girl throve somewhat feebly in her London home.

She did not go to school, gaining all substantial instruction from

her mother. Though we hear that she enjoyed Hone's Every

Day Book when she was nine, she does not seem to have been a

specially bookish child, not so bookish as the elder sister and the

two brothers, who were her only youthful companions. For

visitors, there were only bearded Italian "patriots," in whose

tragic histories, however, the well-trained little ones had sense

and sympathy enough to take interest—Christina, with characteristic

faithfulness, cherishing a relic of one all her life long, so that

it stood in the chamber of her death-bed.

For pleasures, she had games with her brothers and sister,

walks in Regent's Park, every corner of which she knew, investing

the more picturesque points with romantic characteristics which

would have escaped less poetic eyes. Above all, she had

occasional visits to her maternal grandfather at Holmer's End—about

thirty miles from London, a distance which in those days involved

six hours driving in a stage coach! There she got her first

revelation of the beauty of genuine nature and the first inspiration

of her love and sympathy for the undomesticated animal creation.

For animals nearer us, she had already learned a tender affection,

for some of her earliest verses, written when she was about sixteen,

were "On the Death of a Cat, a friend of mine, aged ten years and a

half." Her happy visits to Holmer End ceased when she was

about nine, at which time her grandfather removed to London and

became a near neighbour. The old gentleman was very fond of

little Christina, and prophesied great things of her. To the

very end of her life she cherished the memory of these country

visits, and spoke of the way in which they had awakened her

imagination. A book, Time Flies, which she wrote fully

forty years afterwards, abounds with allusions to those early days,

whose slight incidents, indelibly impressed on her sensitive mind,

she often wove into exquisite parables.

Another youthful joy lay in visits to the Zoological Gardens,

though there her feeling was that the imprisoned birds should sing

"plaintive verses." It is said that, as a child, she told of a

strange dream she had. "She thought she was in Regent's Park

at dawn, while, just as the sun ruse, she seemed to see a wave of

yellow light sweep from the trees. It was a multitude of

canaries, thousands of them, all the canaries in London. They

had met and were now going back to captivity."

A most interesting reminiscence of her childhood we find,

when, veiling her own identity, she told―

"I know of a little girl who, not

far from half a century ago, having heard that oil calmed troubled

waters, suggested to her mother its adoption for such a purpose in

case of a sea-storm.

"Her suggestion fell flat, as from her it deserved to fall.

Yet nowadays here is science working out the babyish hint of

ignorance."

She called herself "the ill-tempered one of the family,"

there having been, in her earlier life, a decidedly irritable strain

in her disposition, partly caused by the infirmity of her health.

"In later life," says her last biographer, Mackenzie Bell, "this was

entirely conquered, and this conquest strengthened her character, as

moral conquests ever do strengthen the character."

As Christina advanced into young womanhood the family means

grew narrower. The brothers had not yet had time to make any

mark in their respective careers, the father was growing old and

feeble, and not only so, but his subject, Italian, was giving place

to German as a favourite study. One of those critical times

came when a household is brought to realise that "something must be

done." It was decided that Mrs. Rossetti and Christina should

start a little school. The experiment was first made in the

house where the family had lived for some time, near Mornington

Crescent. Fifty years ago this school-keeping was the

favourite resource of gentle poverty. It would be as wrong as

it is idle to wish that such avenue of profit was still open, for

too often it admitted women who had little to impart beyond their

own prejudices and ineptitude. It must, however, be owned that

it had some advantages, since it could offer an opportunity to such

women as Christina and her mother. Neither of them might have

been found able to pass modern examinations or to fulfil present-day

"requirements," and yet surely their sweet, conscientious natures

would be a priceless influence on any young girl with whom they came

in contact.

The London school-keeping, however, did not succeed.

Accordingly Christina and her mother, the invalid father

accompanying them, resolved to renew the experiment at Frome,

Somersetshire, the brothers and the elder daughter struggling on in

London.

In Frome they stayed for about a year. It is

significant that this was longest period that Christina ever lived

out of London. She was not very happy while she was there; it

was scarcely likely that she could be. Her father's health was

failing day by day, so that he died almost immediately their sojourn

at Frome came to an end. The school venture succeeded no

better than the first one had done. Also Christina had not

long before had her first love-affair, receiving an offer of

marriage which, as happened with another offer later on, she

resolutely put aside in the belief that both were accompanied by

circumstances which would not have conduced to her highest spiritual

life.

But all these shadows, outer and inner, did not prevent her

from keeping her mind and heart open to impressions and influences.

Among those dull, grey days she laid up beautiful thoughts, albeit

they may be sometimes tremulous with the misgivings of a

self-mistrustful heart. She tells us that on one of her

country walks she found a four-leaved trefoil. She did not

then know of its rarity. She Says—

"Perhaps I plucked and so

destroyed it: I certainly left it, for most certainly I have it not

. . . Now I would give something to recover that wonder: then,

when I might have it for the carrying, I left it.

"Once missed, one may peer about in vain all the rest of

one's days for a second four-leaved trefoil.

"No one expects to find whole fields of such: even one for

once is an extra allowance.

"Life has, so to say, its four-leaved trefoils for a favoured

few: and how many of us overlook once and finally our rare chance!"

It is pretty to know that one who read this parable sent her

a gift of a four-leaved trefoil, and doubtless Christina saw a still

sweeter parable in the substitution.

After the return to London, and the father's death, the

little family struggled on again, its path, however steep being at

least upward. Christina did some literary work in the way of

of compilation and translating: she also began to publish her poems.

But she was not a voluminous writer, nor was any of her work, prose

or poetry, from first to last, of the class which readily commands

"a large market." Consequently, though her name was more or

less before the public from 1855 to her death in 1894, and though

some of her best poems were produced comparatively early, yet her

income from literature never exceeded—and seldom reached—£45 per

annum, until 1890!

Nevertheless, through the success of the brothers and other

circumstances, the family affairs grew easier. In 1861 and

1865, the younger son took his mother and Christina for visits to

the continent. Neither trip exceeded six weeks in duration,

nor did either go beyond tracks tolerably beaten even then: the

first was to Paris and Normandy, returning by the Channel Islands;

in the second, Basle, Como, Milan, Freiburg and the Black Forest

were visited. Christina wrote of those holidays that they were

"enjoyable beyond words; a pleasure in one's life never to he

forgotten," adding that all she had seen made her "proud of her

Italian blood." It appears that the little party walked into

Italy by the Pass of Mount St. Gothard, for she says: "We did not

tunnel our way like worms through its dense substance. We

surmounted its crest like eagles. Or, if you please, not at

all like eagles, yet assuredly as like those born monarchs as it

consisted with our possibilities."

If we did not know that "Uphill" (which, short as it is,

remains to many minds as her masterpiece) had been written in 1858,

we might imagine it to be the outcome of such a pilgrimage.

Mr. Mackenzie Bell aptly says that this "brief sixteen line poem

reveals quaintly, with one flash of genius, a whole philosophy of

life." It is not yet so widely known as to make quotation

superfluous.

|

UPHILL.

"Does the road wind uphill all the way?

Yes, to the very

end.

Will the day's journeys take the whole long day?

From morn to

night, my friend.

But is there for the night a resting place

A bed for

when the slow dark hours begin.

May not the darkness hide it from my face?

You cannot

miss that inn.

Shall I meet other wayfarers at night

Those who

have gone before.

Then must I knock, or call when just in sight?

They will not

keep you standing at that door.

Shall I find comfort, travel-sore and weak?

Of labour you

shall find the sum.

Will there be beds for me and all who seek?

Yes, beds for

all who come." |

Much that had made the interests and pleasures of Christina's life

till this time, now began to fade out of her daily living. The

brothers got married. The very success of the circle of brilliant

young people who had frequented the Rossetti household during its

struggling time, now drew them apart into spheres of their own. So

just as Christina's own genius had obtained some sort of worthy

recognition (pecuniarily unprofitable as it remained till long

afterwards) her personal life settled down upon the narrowest lines.

She was not very much over thirty when she found herself the

youngest member of a household consisting of her ageing mother and

two old maiden aunts. Even her elder sister, Maria Francesca, for

whom Christina had a most reverent love, was much withdrawn by

duties connected with an Anglican sisterhood to which she had

attached herself, her younger sister Christina's self-devotion

enabling her to do thus without dereliction of home duty.

Henceforth, Christina devoted herself to the old ladies, not in any

self-conscious spirit of sacrifice, but with joyful loving service. From that time, with the exceptions of one or two brief visits to a

friend in Scotland, her "holidays" were taken in little

commonplace seaside or spa resorts not far from London, and always

selected solely with a view to the comfort and pleasure of the

seniors. She had no "study" to herself nor made her work of any

importance in the household life. All her daily comings and goings

were regulated in the interests of mother and aunts, so that as

their age and infirmities increased, she was little seen in society,

and could receive nothing in the way of formal visits in her own

house—that house in Torrington Square where she lived on till her

death. Indeed in time its public rooms were converted into bedrooms

for the bed-ridden sufferers.

Despite her tender love for her brother, the poet-painter Dante

Gabriel, and her interest and pride in his genius, there was much in

his history which must have touched her tender spirit to the quick. She was very true about it, too. She would not put a gloss on his

infirmities,

There is no doubt that Christina Rossetti's love for her mother was

the "grand passion" of her life. All her books, save two, were

dedicated to her. After the mother's death, which occurred at a

great age, and only eight years before Christina's own, they were

dedicated to her memory. Through the revelations of her made by her

gifted daughter, we gain a glimpse of a singularly sweet and strong

character, not without some of the mental limitations common to her

period, but a woman with whom tender caressing speeches were a daily

habit, one delicately scrupulous in money matters and always careful

how to spare trouble to everybody.

Such was the life and the surroundings which sufficed Christina

Rossetti for well-nigh thirty years. From everything about her she

drew good and satisfaction and delight. As a young girl she had been

of pensive nature, but it was the avowed creed of her later years

that "Cheerfulness is a fundamental and essential Christian

virtue—the blithe cheerfulness which one can put over one's sadness

like a veil—a bright-shining veil."

She was always ready to learn lessons from the quiet, patient lives

about her, those, as she herself expresses it―

"Learned in life's sufficient school."

telling us how "a good, unobtrusive soul," whom we now know to have

been her aunt Eliza, found comfort in the recollection "that no day

lasted longer than twenty-four hours," and setting before herself

and others the example of "an exemplary Christian" (her aunt

Charlotte) who said "that she was never blamed without perceiving

some justice in the charge." Sometimes such little autobiographic

touches (their secret kept till after her death) take very

beautiful form, as when she tells us―

"Once in conversation I happened to lay stress on the virtue of

resignation, when the friend I spoke to depreciated resignation in

comparison with conformity to the Divine will.

"My spiritual height was my friend's spiritual

hillock."

Her quiet matter-of-fact "changes" sufficed to help her to vivid or

beautiful imagery. The sight of a spider running down the bare wall

of a seaside bedroom, apparently frightened of its own huge shadow

cast by the gas-jet, was to her a symbol of "an impenitent sinner

who, having outlived enjoyment, remains isolated irretrievably with

his own horrible, loathsome self."

The sight of swallows perched on a telegraph wire at Walton-on-Naze

could give rise to a parable of subtle beauty, thus―

"There they sat steadily. After a

while, when someone looked again, they were gone.

"This happened so late in the year as to suggest that the

birds had mustered for migration and then had started.

"The sight was quaint, comfortable-looking, pretty. The small

creatures seemed so fit and so ready to launch out on their pathless

journey: contented to wait, contented to start, at peace and

fearless.

"Altogether they formed an apt emblem or souls, willing to

willing to depart.

*

*

*

*

"That combination of swallows with

telegraph wire sets in vivid contrast before our mental eye the sort

of evidence we put confidence in, and the sort of evidence we

mistrust.

"The telegraph conveys messages from man to man.

"The swallows, by dint of analogy, of suggestion, of parallel

experience, if I may call it so, convey messages from the Creator to

the human creature.

"We act instantly, eagerly, on telegrams. Who would dream of

stopping to question their genuineness ?

"Who, watching us, could suppose that the senders of the

telegrams were fallible, and that the only Sender of providential

messages is infallible?"

She had, as we have said before, that love of all created life which

did not only care for those which touched her own personality, as

"Muff," the pet cat, but was also aware of links between her soul

and those creatures which seem remotest from humanity. She did not

think all is waste which does not served man. She sang―

|

"And other eyes not ours

Were made to look on flowers,

Eyes of small birds and insects small:

The deep sun-blushing rose

Round which the prickles close

Opens her bosom to them all.

The tiniest living thing

That soars on feathered wing,

Or crawls among the long grass out of sight,

Has just as good a right

To its appointed portion of delight

As any king," |

Of course, such a temperament is open to soothing and consolation

which could not touch the coarser natures which have not cultivated

sympathy. She tells us how in her earlier, troubled times—

"One day long ago, I sat in a

certain garden by a certain ornamental water.

"I sat so long and so quietly that a wild garden creatures or

two made its appearance: a water-rat, perhaps, or a water-haunting

bird. Few have been my personal experiences of this sort, and this

one gratified me. I was absorbed that afternoon in anxious thought,

yet the slight incident pleased me.

*

*

*

*

"Many (I hope) whom we pity as

even wretched, may in reality, as I was at that moment, be conscious

of some small secret fount of pleasure: a bubble, perhaps, yet lit

by a dancing rainbow.

"I hope so and I think so: for we and all creatures alike are

in God's hands, and God loves us."

With such thoughts and feelings, vivisection was, of course,

abhorrence to her, as much from the thought of those who inflict

agony as of the dumb innocent who endure it. In her quiet way she

worked in the cause of mercy and justice in this matter, as also in

the effort to secure better legal protection for young people under

the age of responsibility. She was much interested in endeavours to

help the poorest girl-workers of London, such as the matchmakers,

jam-makers, and rope-makers. She had a friend actively engaged in

this work and used to look for her accounts with great interest,

saying―

|

"London makes mirth, but I know God bears

The sobs in the dark and the dropping of tears." |

She would have liked herself to join in these labours, but felt that

her duties kept her at home, for though by that time her dear mother

had been taken from—doubtless leaving a void which nothing could

have filled so well as active good works—the two aged invalid aunts

remained.

But in neighbourly services she abounded: she was ready to seek work

for the workless: and a most touching little relic is an

accidentally preserved list of seaside lodgings, with a detailed

description of accommodations and charges, drawn up by her to spare

trouble to a suffering lady, the wife of a valued friend. Such

books as she had in her little library—which after all was not hers

in a way, for she had few books save those which had been bought by

her mother—were always eagerly pressed into the service of any

friend likely to find them useful. Mr. Mackenzie Bell says,

"Whenever Christina Rossetti wished to confer a favour, her manner

of doing so was as if she were about to ask one." That is the

hall-mark of God's ladyhood.

It is said she was a great judge of character and had strong

likes and dislikes. But she held all this in charity.

None of her parables are more telling than that which narrates how a

traveller was received at a certain house with great hospitality and

courtesy, so that he felt "he lacked nothing but a welcome," and so

went away with a most gloomy impression, only to learn afterwards

that the hosts he had thought so chill, had been bearing an

irretrievable grief, which they could hide from him, though they

could not rejoice with him. So they had given him all they

could. Her comment is―

"The fret of temper we despise may

have its rise in the agony of some great, unflinching, unsuspected

self-sacrifice, or in the sustained strain of self-conquest, or in

the endurance of unavowed, almost intolerable pain."

Elsewhere, remarking that even our most cherished opinions

are almost inevitably modified by time, she adds, with subtle

wisdom—

"If even time lasts long enough to

reverse a verdict of time, how much more eternity?

"Let us take courage, secondary as we may for the present

appear. Of ourselves likewise, the comparative aspect will

fade away, the positive will remain."

She drained all the little pleasures of life to their last

drop, loving to tend her ferns, to watch the sunlight effects in the

trees of the London square, to walk in the London square itself.

But let nobody think that this noble contentment is reached without

effort. She was not one to talk of her struggles but we can

trace the marks of them, as it were, in her poems. She had

cried—

|

"If I might only love my God and die!

But now He bids me love Him and live on." |

She had felt—

|

"These thorns are sharp, yet I can tread

on them;

This cup is loathsome, yet

Christ makes it sweet,

My face is steadfast towards Jerusalem—

My heart remembers it.

Although to-day, I walk in tedious ways,

To-day His staff is turned into

a rod,

Yet will I wait for Him the appointed days

And stay upon my God." |

And thus she reached the calm heights where she could sing—

|

"Chimes that keep time are neither slow

nor fast,

Not many are the numbered sands nor few;

A time to suffer, and a time to do,

And then the time is past." |

The end came to her just when her selfless nature would have

chosen, for as she had thanked God that she was left to mourn her

mother and not her mother to mourn her, so she survived till both

the agèd aunts were also removed.

Indeed, all the family circle, save her youngest brother, had gone

before her—Dante Gabriel, the unhappy genius, her sister, and both

her brothers' wives.

Christina Rossetti had suffered much from physical ill-health

all her life, and her end was full of bodily pain of a peculiar

nature which tended to gather clouds of depression about her.

But one of those who best knew and appreciated her, declares that

Christina herself would accept even this with joy, could she but

have realised how the thought of her passage through these deep

waters must strengthen and cheer others called to follow her by the

same dark way. Her beautiful spirit never failed. To the

offertory of the church, in whose services she had found so much

comfort, she sent the regular contribution she could no longer give

with her own hand. She liked to be told when visitors called,

though she could no longer see them, and she liked them to be

detained till she could send down some special, kind little message.

She even instructed her nurse that if a certain valued friend should

call soon after her departure, that friend should be at once

admitted to look on her dead face.

In person, Christina Rossetti was very attractive, though an

illness from which she suffered twenty years before her death,

slightly marred the beauty of her face. She had a placid,

gentle manner. "In going into her house," says her biographer,

"one seemed to have passed into an atmosphere of rest and of peace."

Speaking, as she spoke, in symbols, we would say that the

sweetest fruits often ripen in walled gardens.

―――♦―――

ECCENTRICITY.

(From Good Words)

Do you flatter yourself that nobody thinks you eccentric? Do

not. If there is not something about you which would seem to

others eccentric, then you have no reasonable hope of immortality,

for you have no centre of individuality, nothing to show that you

are a being and not a mould.

We call people eccentric whose ways are not our ways.

“She is so eccentric, poor thing!” says the woman of society,

speaking of some old friend. “She never goes anywhere.

She says she does not receive nor pay calls. There is no use

in asking her to take a stall at a bazaar. She has buried

herself alive with that husband of hers and those four rough boys.”

Yet probably the woman who speaks and the woman who is spoken about,

both say alike that home should take precedence, and all the

“eccentricity” lies in the fact that the one puts her precepts into

practice.

The eccentricities of genius have long been a handy theme for

the leisurely comments of people of safely limited talent. The

genius is eccentric, because, having discovered the diet best suited

to his constitution, he keeps to it and will not eat pickled salmon,

no, not even to please a lord mayor. The genius is eccentric,

because he did not pay the least attention to the Countess of Dulborough, but spent the whole evening talking to that old maid,

Miss Good, who is nobody at all.

The word “eccentric” is commonly applied to any deviation from

custom, or from the habits and manners of others, but as they never

profess to radiate from any centre, ought it not rather, in mere

strictness of speech, to be applied to any deviation from the

declared centre of our own existence?

Is not true eccentricity simply a wish to do an easy and plain thing

in a hard and intricate way, or else to do something which had

better not be done at all? To call a merely unusual or novel action

eccentric is to confound eccentricity with originality and progress. The first man to build a house or to carry an umbrella was no

eccentric. Any man who would persist in walking on his hands, or in

going to bed in all his day-apparel, would have been always

eccentric, and will be ever so.

On the other hand, what is generally called eccentricity is commonly

the discovery of easier and swifter methods, or of novelties,

whether in duty or circumstance. Such a man is said to be so

“peculiar“— he made all his friends in such queer ways, — one

friendship began in a chance conversation on a steamer, another in a

meeting at an inn. Now, everybody admits that the making of friends

is perfectly legitimate and normal; only most prefer the manufacture

to be carried on by an elaborate machinery of introductions, calls,

cards, etc., through which all our carpets are worn out by the feet

of casual comers and goers, before we hear the footfall of one who

really brings good tidings of love and fellowship to our own soul. Or another is called eccentric, because, heartily believing

something to be of vital good to his fellow-creatures, he invests

all his money in furthering it, and spends himself in recommending

it in season and out of season. His belief itself may be eccentric,

or it may not; it may be in the golden rule or in a particular pill,

but his honest application of that belief is not eccentric, and

never can be. At that point precisely he is at one with all the

great men who have soiled and strained themselves to push the world

towards God and good, — and one against the huge army of charlatans

who impose burdens which they do not bear.

What a huge mass of small misery would vanish if people could dare

to be eccentric in the sense of doing something which is right for

themselves as individuals! How many a woman suffering under the

close pinches of a narrow income, with a constant dispiriting sense

of shabbiness, could be set free from her worst torture, if she gave

up the use of gloves except when needed for warmth, and put their

price into her general treasury! Is it best to have hands a little

brown or a face worried and anxious? The real beauty of a hand is

not spoiled by exposure, or even by hard work, and nothing can be

more hideous than the preserved whiteness and plumpness of a coarse

hand. We cannot imagine angels in gloves. We cannot imagine the old

healthy heathen goddesses in gloves. The hand-clasps which we shall

never forget were given by ungloved fingers.

To hide hands or face from ordinary wear and tear lest they spoil

them is as bad as to starve with money in the bank lest we spend it. Hands and faces were given us to be used and worn out, and wear out

they will whether or no. The true test of beauty is its long

resistance and its faculty for wearing well. Who would put brown holland over Russia leather chairs? While new, they might be taken

for good imitation, but when old they are undoubted.

Everybody has to be eccentric somehow. It takes many a queer twist

before the infinite variety of human character and circumstances can

be reduced to a similarity almost as striking as that in a packet of

pins. It was a humorous and suggestive illustration of this that a

book, lately written to advise ladies of limited income how to look

like their richer neighbours, hinted that in order to secure the

conventional number of silk dresses and parasols, they might even

wear coloured under-linen!

It is often said that when poverty approaches as “an armed man,” the

first retrenchment is made on the table, the last in the wardrobe.

This ought not to be. Is not “the body more than raiment”? Put the

boy into corduroys instead of broadcloth, but spare him a good

dinner, and so give him a chance of getting his own broadcloth when

his turn comes, instead of wearing out yours till it drops in rags

about him in some casual ward. Any linen shirts and beaver hats you

can buy will soon be translated to some other sphere of matter quite

beyond his use, while muscle and nerve will remain. There is nothing

sadder than the study of the children of shabby-genteel families. They retain the well-moulded features and lithe forms of “good

blood,” long after the departure of the hot energy or cool staying

power which really constituted it. To borrow a phrase from the

stable, “They are good ones to look at, but bad ones to go.” They

are our social slaves — the drug of our labour-market, and capital

shrewdly knows that it can extort any terms from them, while it does

not insist on fustian jackets or white caps and aprons.

There may be table-retrenchments for which nobody needs pity. If the

children get porridge instead of tea, rosy apples instead of

jellies, they may bless the poverty that suggested the change. It is

the poorer tea and the thinner bread and butter which is to be

deprecated. Even the moderate cost of the carefully hoarded black

silk dress, which deceives nobody, if put into the bread account,

would relieve all tightness in that quarter for the whole period

that it would wear.

Let a widowed mother make her Sabbath-best of serge, and boldly

teach her lads the virtues of holland and corduroy, that she may

grudge no quantity of wholesome food, no cost of merry holiday, and

she may live to display the rich gifts from her eldest, and to boast

that her youngest, though he does not make money, has learned to

live so simply that he can easily afford to give his life to the art

or science of his ambition, and so to write the name she gave him on

the best page of his country’s history.

To wish to be like other people is as futile as it is fatal. We

cannot be like anybody but ourselves. The more conventional we are,

the more we resemble the jay which borrowed a feather from every

other bird. We do not succeed in our attempted resemblance, we only

spoil our own appearance and our own capacities. Nobody admires

such. They are ridiculous even in the eyes of similarly bedecked

jays. How the people in a theatre laugh as old Polonius proses! There is wisdom in his words, but it is wisdom as a rose after a

snail has slimed it. He knows right, wrongly. And yet we may be

quite sure there are more of Poloniuses in box, pit, and gallery

than there are of vacillating Hamlets, blunt Horatios, or guilty

kings and queens. These belie the prince’s words. These “galled

jades” do not wince. Their criticism is, “This is a fool:” the moral

they deduce appears to be, “Let us be so likewise.”

Our use of the word “must” should be greatly in our minds when we

confess that we do those things which we ought not to do, and leave

undone those things which we should do. We neglect duties that

should be done at any cost of will-power; we helplessly accept as

duties actions which, done as such, lose all their value. How many

“cannot” dismiss a servant, and open their own hall-door or dust

their own shoes, even though their annual expenditure is regularly

in excess of their annual income! Yet they “must” pay calls on

people whom they do not like, and they “must” go to parties where

two or three hours of black-hole atmosphere and ten minutes’ gobble

at unwholesome food leave them with a week’s indigestion and bad

temper. Or on higher levels it may be that we “cannot” keep a

certain commandment, but we “must” believe a certain creed. We

cannot serve some fellow-creature, but we must love him! It is

simply a double lie, as transparent as if one should say he cannot

cross a gutter, but can easily jump over the moon.

From some people’s talk one might infer that public opinion was a

solid body of resistless force, or at least a policeman with a

truncheon. “One cannot go to two parties in the same dress,” said a

lady. “What prevents you?” asked her companion. “Simply do it.”

What is public opinion? The aggregate of many persons’ opinions,

mostly founded on their own ways. Do you acknowledge even to

yourself that their ways and their opinions are better than yours? You think Mrs. S. a feather-brained creature, in fact a fool, and