|

[Previous Page]

POETRY ON TWELVE SHILLINGS A-WEEK.

AMONG the

countless "copies of verses" sent to The Argosy, there

reached us last month a few pages entitled "Fairy Revels."

These verses had a freshness as of early flowers; there was a happy

music in their rhyme, and their theme was so graceful and so gay

that it seemed as if they must be the production of some young poet,

with the spring-time working in his blood. Andyet it was no

"new poet" who had written "Fairy Revels," but, as we have since

learned, an old man who has borne the burden of half a century of

poverty and toil.

About thirteen years ago, when more than forty years of his

life had passed in labour which at no time yielded him more than

twelve shillings a-week, the passing of a stranger through a field

in which the poet was reaping brought about the first recognition of

his genius. Born before the days of National and British

Schools, a good mother taught him to read, and by dint of buying and

borrowing, principally the latter, he made acquaintance with the

English poets, and learnt the art of song. He says:—"I well

remember taking Shakspeare in sixpenny numbers when I was working

for seven shillings a-week, and had to maintain myself and pay for

lodgings, and even then I regretted not the loss of a day's work in

wet weather (scanty as my earnings were) if I could spend it in

reading. I have sat up many nights reading Milton when others

have been sleeping, and passed many, many hours with Shakspeare when

perhaps I should have been otherwise employed. And thus my

youth passed away, with but few enjoyments in the estimation of

those around me, whose company I shunned, preferring the solitary

walk in fields or lanes to the noise and laughter of the

streets,—calm communion with silent nature to the mad excitement of

intoxication,—and the lay of the nightingale to the song of the

drunkard. In all my lonely musings I had bread to eat that

they knew not of: from a boy I loved the trees and flowers, woods

and waters, and have conversed more with them than with men. I

loved all that was beautiful in nature; and, if I cannot express

myself as a poet, I have always felt as one."

Of his power of expression the reader may judge for himself.

|

FAIRY REVELS : A FRAGMENT. |

|

Now the full moon climbs the sky,

And hinds in heavy slumber lie;

The bleating sheep are penned at rest,

Their fleeces on the daisies press'd;

Ands all around is hush'd and still,

Except the tinkling of the rill,

And songs of wakeful nightingales

Floating o'er the dewy vales.

Now is the time we fairies meet,

And dance our rounds with noiseless feet.

Hie thee! my attendant sprite,

To yonder mead with kingcups bright,

And bring me from the cowslip pale

A freckled flower, called a male.

There is music in that flower,

And children know its magic power,

For late I in a primrose lay,

Where a group had met to play;

One had pluck'd the wild white rose,

And wreathed her fair unwrinkled brows;

Another, round her flaxen head,

Wore bindweed blossoms, white and red;

A third had cull'd the light blue-bell,

And it became her beauty well;

Another's dark and glossy hair

Was intermixed with lilies fair;

And all were happy, all were gay,

Though mortal creatures form'd of clay.

How they laugh'd, and danced, and sang,

Till the answering echoes rang;

One, the merriest of them all,

Toss'd and caught a cowslip ball,

Till, warm and wearied, down she sank

In softest moss upon the bank;

And from that globe of fragrant flowers

She pluck'd a tube of wonderous powers,

And biting off its slender tip,

With swollen cheek and pouting lip,

She blew its trumpet sound so clear,

It charm'd and won my listening ear;

And much I wished that each could be

Always, as then, from sorrow free,

Exempt from suffering, care, and sin,

They seemed to us so near akin.

That flower shall now our trumpet be,

Sound it loudly, three times three.

SONG.

Awake, awake, ye fairies all,

Come at the cowslip trumpet's call;

Come from the rose, where all day ye sleep,

Come from the banks where the wild vines

creep,

Come from the foxglove's painted cells,

Come from the lily's waxen bells,

Come from the tubes of the sweet woodbine,

Come from the leaves of the eglantine.

Awake, awake, ye fairies all,

Come at the cowslip trumpet's call.

Ye that couch in the gorse and broom,

Ye that hide in the clover's bloom,

Ye that peep from the pansy's hood,

Ye that shroud in the dark green wood,

On sycamores with honey wet,

Or willows by the rivulet,

Awake, ye elves and fairies all,

Come at the cowslip trumpet's call.

From the plaits of the daisy's frill,

From the folds of the daffodil,

From the May buds on the thorn,

From the larkspurs in the corn,

From the cockles white and red,

From the wild thyme's fragrant bed,

Awake, arise, ye fairies all,

Come at the cowslip trumpet's call.

Ye that in the tulips lie,

Rocking as the winds go by,

Ye that in the harebells swing,

Or to the sturdy orchis cling,

Ye that sleep in the leafy bowers,

Curtain'd by the lilac's flowers,

Hasten o'er the spangled green,

To the summons of your queen.

________________

You my trusty guards attend,

And this sacred place defend.

Here is armour tried and true,

Helmets of the monkshood blue,

Lances keen and pointed spear

On the thistle standing near:

And for shields, my champions bold,

Daisy disks embossed with gold.

Whilst this mystic ring we dance

Let no noxious thing advance,

Newt, or toad, or beetle black,

Snail with castle on his back,

Bloated spider, sly and grim,

Earwig gaunt, or earthworm slim,

Slimy slug, or centipede,

Or caterpillar, ravenous breed.

Emmets pinched, and small green lice,

Mining moles, and pilfering mice,

Prowling, lurking, green-eyed cats,

Weasels fierce, and whisker'd rats,

Thorny hedgehog, scaly snake.

Hiding under fern and brake,

Chase them, keep them far away,

While we feast, and dance, and play.

Sweetly blow your breathing flutes,

Softly touch your tinkling lutes,

Mellow flutes from oaten sheaves,

Lutes of stringèd plantain leaves,

Clarionets of knotted reeds,

Kettledrums of poppy seeds;

Hand in hand the measure tread,

O'er the bending cowslip's head,

With springing toe and lightsome heel,

In and out in mazy reel;

Thus we sing, and dance, and play

Till the blushing dawn of day.

Come, the banquet now prepare;

Bring the viands rich and rare.

Here's a mushroom, white and round,

Peeping from the heaving ground—

Now I touch it with my wand,

See its swelling globe expand;

Now its stalk is shooting up,

Now it opes its pinky cup,—

This shall be our festive board,

Here shall sup our merry horde.

Here are kingcups, bright with gold,

Bowls of acorns, carved and old,

Tankards of primroses pale,

Stoups of lilies of the vale,

Nettle flagons, ivory white,

Chalices of silver bright,

That in shady thickets gleam,

Or shine like stars beside the stream,

Flasks of purple columbine,

Filled with liquor crystalline,

Whatsoe'r the wild bee sips

Is not gross for fairy lips.

Let the vessels all be fill'd

With pearly dew by night distill'd,

And honey wrung from sweetest flowers,

From hills and valleys woods and bowers,

Candied drops from bluebells deep

Tears the blue-eyed violets weep,

Aroma by roses shed,

Spices from the wild thyme's bed,

Ruddy drops from bleeding cherries,

Juices crush'd from swelling berries,

Nectar press'd from purple plums,

Pulp of peaches, amber gums,

Temper well and mix the whole

In our acorn wassail bowl.

Sit we now upon the grass,

Quaff the cup and let it pass;

Freely drink and do not fear,

No inebriate fumes are here.

Hark, I hear the booming chime

By which dull mortals measure time;

And the high ascending moon

Tells that night is at its noon. |

Nor is there wanting in our peasant poet a keen sense of humour, as

witness:―

|

TEA-TABLE TALK. |

|

In a garden nook, by a wide-spreading yew,

A stingy old Nettle and Dockweed once grew;

They were sipping the dew, and between you and me,

They mixed it with scandal as ladies do tea.

"I can't think, my dear Dock," the old Nettle began,

"Why the Rose has been always a favourite with man;

Her breath's very sweet, we all must allow it,

And true she has beauty, at least folks avow it,

But then she's so vain, she thinks all must adore her,

And that such as we ought to fall down before her.

Her greatest delight's, you may see by her eye,

To be fondled and kissed by each fop passing by;

And her dress is the oddest that ever was seen,

She wears throughout July a moss victorine!"

"Whilst little Miss Snowdrop," replied Madam Dock,

"Comes out in the frost in a white muslin frock;

And though she's so modest, and hangs down her head,

Young Crocus and she were caught both in one bed.

And that little minx too, so sickly and pale,

You know who I mean, dear, Miss Lill of the Vale,

So shy and retired, all her company shun,

So modest and humble you'd think her a nun;

Yet her I once saw, and it augured no good,

Tête-à-tête in a nook with old solemn Monkshood.

Then there's Madam Poppy, so vulgar and red,

How gaily and gaudy she dresses her head;

She always looks sleepy, and most people think,

And I quite believe it, she's given to drink.

You know Mrs. Pansy, with dark velvet hood,

And a face like to some you see carved out in wood;

I hear that she's lately come out in great state,

And has wholly forgotten the old garden gate.

Do you hear if Miss Dahlia has got a new dress,

To appear at the show? Why she cannot do less;

And though she has dresses of every hue,

She is sighing and pining to have one of blue.

Madam Tulip last Sunday was splendidly dressed;

But then, dear, her character's none of the best.

She is painted and powdered, but smell of her breath,

I am sure it will make you sick nigh unto death."

"Well, now then, I'll tell you a capital joke,"

Mrs. Nettle replied, and she laughed as she spoke

"Here's old Dolly Daisy, that lives in the dell,

Has a daughter who's gone with my lady to dwell

She calls herself now by a high-sounding name,

You would scarcely believe that from field-work she

came.

She'd a sister, you know, overturned by the plough,

When Bobby Burns blubbered and made such a row.

And there's those Geraniums, a proud idle set;

Whilst we are abroad in the cold and the wet,

They dress themselves out in pink, scarlet, and white,

And stare out at the windows from morning till night.

Those delicate gentry that come from abroad—

I know they are glad of their bed and their board—

They boast of the sunshine of Naples and Rome,

If they don't like our climate, why not stay at home?

Our land's overrun by such strangers as these,

By singers and dancers and poor refugees:

Only think how our language is broken and maul'd,

And to hear now what jaw-twisting names they are called;

But I will be bound if their right names were known,

They'd be something as common as Smith, Jones, and

Brown.

But 'tis time to be going; the moon's shining bright,

And I cannot bear scandal. Good night, ma'am, good

night." |

On how dark a background of poverty and misery this bright and cherry

humour could play, may be seen in the following verses:―

|

WRITTEN FROM NEWMARKET UNION.

(To my Sister at Cambridge, 1846.) |

|

Since I cannot, dear sister, with you hold communion,

I'll give you a sketch of our life in the Union.

But how to begin I don't know, I declare:

Let me see; well, the first is our grand bill of fare.

We've skilly for breakfast; at night bread-and-cheese,

And we eat it and then go to bed, if we please.

Two days in the week we have puddings for dinner,

And two we have broth, so like water, but thinner;

Two meat and potatoes, of this none to spare,

One day bread-and-cheese—and so much for our fare.

And now then my clothes I will try to portray,

They're made of coarse cloth and the colour is grey.

My jacket and waistcoat don't fit me at all;

My shirt is too short, or I am too tall;

A sort of Scotch bonnet we wear on our heads;

And I sleep in a room where are just fourteen beds.

Some are sleeping, some snoring, some talking, some

playing,

Some fighting, some swearing, but very few praying.

Here are nine at a time who work at the mill,

We take it by turns, so it never stands still:

A half hour each gang, so 'tis not very hard,

And when we are off we can walk in the yard.

We have nurseries here where the children are crying,

And hospitals too for the sick and the dying.

I sometimes look up to the bit of blue sky,

High over my head, with a tear in my eye.

Surrounded by walls that are too high to climb,

Confined as a felon without any crime,

Not a field, nor a house, nor a hedge can I see,

Not a plant, not a flower, not a bush, nor a tree,

Nought except a geranium or two that appear

At the governor's window, to smile even here. |

And in such a dismal prison-house as this, the author of "Fairy

Revels" might, but for the intervention of friends, end his days. A

London Publisher, has undertaken to bring out a small collection of

his poems, and it is hoped that the sale of the volume may at least

avert a fate so hard.

EDITOR.

[Isa Craig]

Ed. - why Miss Craig fails to identify the

subject of her article is a mystery because it rather defeats its

purpose. However, the poet in question is J. R. Withers

(alternatively James Withers Reynolds), an impoverished

Cambridgeshire shoemaker. He and his family were inmates in

Newmarket Workhouse in 1846 from where the above verse letter to his

sister was written. He is later reported to have come to the attention of literary

society and was fashionable for a while, but nevertheless met the

fate of other artizan poets, dying in poverty.

Withers' volume "Poems Upon Various Subjects" (1854) is

available online via Google Books. (For other workhouse verse, see

Gerald Massey, "Little

Willie".)

―――♦―――

AN OLD FRENCH CITY.

Y a

special interposition of providence, and the prayers (sous

extendu) of its patron saint, St. Etienne, Bourges is on the

road to nowhere. It is approached, in this year of grace

eighteen hundred and sixty-six, by a little branch railway between

the Ligne du Centre and the Ligne du Bourbonnais.

It is also built upon a small hill, overlooking the wide plains of

Berri; in consequence it would be both expensive and useless to

drive boulevarts through its antique streets. It therefore

remains much what it was twenty years ago, when we drove into the

town with post-horses, being bound from Geneva to Paris. Oh,

those days of trotting horses and jingling bells, across the bare

wide fields of France, along the interminable pavés

lined with low fruit-trees, past the dirty villages, each with its

small hostelerie, and its little church, and so at night clattering

into the gates of the fortified town. Those days are gone for

ever. I am glad I have known them: "I, too, have been in

Arcadia," and have driven post like Sterne, like Arthur Young, like

Louis XVI. flying to Varennes, like Marie Antoinette looking in

agonized suspicion from her chariot window. You, my little

heir of the nineteenth century! you, oh child of the train and the

telegraph! nothing will you ever know of ancient France—of

l'ancienne régime. You

will not even stop at towns such as these; for you will have no

youthful memories calling on you to "halte-là!"

To you, Bourges, Chartres, Rheims, will simply mean "Buffet, dix

minutes d'arret." Oh! child of the nineteenth century, I

pity you from the depths of my heart!

Now, for the moment, we have to do with Bourges—how to get there? It

cost me some trouble to find out, so excuse me if I explain. You go

to Orleans—that is simple enough; Orleans is on the high road to

everywhere; meaning the Loire, Tours, Nantes; or the Spanish

frontier, by Poitiers, Angoulême, and Bordeaux. But to come here

you go to none of these places. You get out at Orleans, and into a

slow little train, which creeps over an interminable marshy heath,

reminding one of Chat Moss, that triumph of English engineers. Presently you come to Vierzon, and here again you diverge on to

another and still less important line, which in an hour's time

deposits you at Bourges.

"Bourges, then," observes the untravelled, "is an unimportant place

after all. What do you go there for?" Pardon; Bourges is the ancient

capital of Berri; and you know, or ought to know, that the father of

the legitimate king of France derived his title hence. The father of

the exiled Henry V., commonly called Comte de Chambord, was Duc de Berri.

He was assassinated in 1821, and his widow was that heroic Madame of

whom such exciting stories are yet told in Brittany. She only

died in 1864, a brave woman, who would have saved France, so far as

she knew, from endless troubles and a doubtful future―toujours

à recommencer.

Secondly, Berri is the native country of perhaps the second greatest

French author of this century. I give the first place to Honoré de

Balzac, the second to Georges Sand. She loves it, and has given the

most charming descriptions of its familiar landscape. She has an

estate therein, where she lives like a Lady Bountiful, one of the

many phases of her many-sided nature.

Thirdly, Bourges possesses one of the four great cathedrals of

France; Amiens, Rheims, Chartres, are the other three.

Fourthly, Bourges has a particular association for the British

public. They do not know much of French history, it is true; the

grand, the picturesque, the romantic scroll, which descends from Pepin and Charlemagne to the feet of the last lone and childless son

of the Fleur de Lys, is almost an unknown writing to the Englishman,

who yet can boast of Alfred, of the Black Prince, and great Queen

Bess; but there is one French king, immortalized by Sir Walter Scott

in his Quentin Durward, and familiarized by Charles Kean, at the

Princess's Theatre, with whom we are all acquainted. His crafty

intellect, his superstitious devotion, his peculiar cap with the

metal images of saints, his abominable hypocrisy, his love of the

Scotch Mercenaries, and the clever way in which he began to assert

the predominance of the monarchical power above that of the feudal

seigneurs; all these things are pretty well known to the reading and

the play-going public. Well, Louis XI. was born at Bourges; his

father, Charles VII., the king whose kingdom was saved by Jeanne D'Arc, was driven here by the English, and so beset that at one time

he was more rightly to be called king of Bourges only than king of

that France which was really in the hands of his natural enemies,

our honourable selves. Such are the titles of Bourges to a

respectful interest. They would look well in a gazetteer; they

occupy a couple of pages in Murray's Handbook of France; but what

geography, what handbook, can ever give the least idea of the living

beauty and interest of these old French cities? To define their

charms is as difficult as to say why peaches ripen. It is not only

beauty, though they are rich in that; I saw to-day the cathedral of

Bourges rise flat and grey across a patch of water bordered by tall

poplars, and marvelled at its adaptation to all accessories; to a

foreground of gardens, and equally to its architectural approaches

by gable-ended streets. But it is not beauty only. It is tradition,

romance, the regretful sense of that which is fast disappearing. It

is reverence for our fathers, anxiety for generations to come; it is

the idea and the charm of the past, the present, and the undeveloped

future, all wrapt in one vision of other days.

First and foremost, of the Cathedral of Bourges. How shall one

translate it into words? A few zigzags from the inspired pencil of Pugin would better suffice. Yes, even better than a photograph, for Pugin gave in his sketches not merely the beauty of the thing

represented, but his own vivid appreciation of it; so that in

looking at his marvellous sketches of foreign architecture one seems

to see it with Pugin's eyes.

All day, from morning to evening, I have been in and out of this

cathedral, examining its details by the help of a very good guide,

written by one of its own clergy—written, consequently, as a man

writes of his native land. Well, then, the present edifice is the

fourth of its name and race, the first having been built A.D. 250,

in the days of Roman Gaul. The legend says that St. Ursin, the

apostle of Berry, and first archbishop of Bourges, was allowed to

build it on the ground of the Roman Palace, or Governor's House. It

was rebuilt in A.D. 380 by another saint, and again in the ninth

century. Some fragments of this last erection yet remain, but the

glorious church now called St. Etienne de Bourges was built early in

the thirteenth century, in what we call the "Early English" style. Perhaps it is our familiarity with its long sombre lines which makes

it so inexpressibly beautiful to English eyes.

The construction is singular, the external situation eminently

picturesque high above the ramparts at the extreme south-east of the

town, and having a large garden crossed by avenues of limes between

it and the wall. It is a long building, without transepts, and with

a double aisle on each side of the nave; the mid walk thus formed

having been intended for processions. The perspective flies away

like that of Westminster Abbey, and is lost in a glimmer of painted

glass. The pillars are immensely high, and their plain simplicity

increases the effect; some architects have even objected to the

extraordinary height; but their defence is that they "lift up the

hearts" of the beholder. Sursum corda is their everlasting response.

Then the number of these columns—they form a forest of stone. Taking

them altogether, large and little, and counting those composite ones

of which Sir Walter Scott says that at Melrose they were--

"Like bundles of lances which garlands had bound,"

there are nearly three thousand, and nearly every capital is

carefully and beautifully designed and sculptured. Therefore the

effect, when one walks across the west end, from wall to wall, may

be imagined. "The groves," says Bryant―

"The groves were God's first temples, ere

man learned

To hew the shaft, or lay the architrave,

And spread the roof above them—ere he framed

The lofty vault to gather and roll back

The sound of anthems; in the darkling wood,

Amidst the cool and silence, he knelt down,

And offered to the Highest solemn thanks

And supplication." |

But here is a temple which well-nigh realizes the effect of those

primitive groves, and it is perhaps due to its imposing height and

the vast scale and simple breadth even of its detail, that it is

much less molested by false ornament of a temporary kind than most

foreign cathedrals. Here are no bad pictures, no gilded

constructions of the taste of Louis le Grand. All belongs to the

earlier and purer epochs of French art. The altars are small, and

such of them as are modern have been restored after ancient models.

The images of saints in the chapels which surround the exterior

aisle are small, and of a refined character; and the wrought-iron

work which separates the choir from the nave is extremely delicate. Thus there is nothing to distract the eye from the great

architectural conceptions here so wonderfully carried out. And

through this vast building the population ebbs and flows all the

Sunday like the waves of the sea.

I spent nearly the whole day in

the cathedral, examining the chapels between the services, and was

much struck by the way in which it was really used by the people.

Cold as was the weather, it had a warm look. In the afternoon the

mighty nave was paved with a dense mass of human beings to hear a

preacher from Paris. The men had the advantage, being grouped in the

neighbourhood of the pulpit. Outside them, on every side, were the

white caps of the Berrichon women, intermingled with the bonnets of

the fashionable ladies. About five o'clock the great congregation

broke up, streaming through the several doors to the thunder of the

organ, as twilight began to darken the aisles, which are always dim,

even at noon, so rich is the painted glass. It was spared in "'93,"

because it would have been so expensive to reglaze even with white

glass. But eighteen windows were sacrificed, I believe, in the

middle of the last century, because the worshippers could not see to

read their prayer-books—a remote consequence of the invention of

printing! The painted windows which remain are covered with Bible

stories. They are among the most beautiful in the world.

There is a subterranean church, which hardly deserves to be called a

crypt, so fair and lightsome is it. It contains some monuments,

finely sculptured, which were deposed from the upper church in

"'93." I need not say that from the tower one sees far and wide over

Bourges and the flat plains of Berri, where the vine is largely

cultivated.

Then I went over the roofs of each aisle, there being a considerable

space (as in the dome of St. Paul's) between that which is seen from

below and the exterior. Oh! the enormous masonry; oh! the forest of

beams. All strong, and straight, and smooth, and six hundred years

old. A real forest must have been sacrificed to build St. Etienne.

This walk was agreeably diversified by crawling up a stone staircase

with wide iron rails outside one of the flying buttresses. It was

not till we had moved considerably to one side that I had any

conception where we had been; passing through the mid air on a

narrow, sloping bridge of stone which looked a mere nothing. "Everybody asks to go up that staircase," said the good Suisse,

triumphantly. Query, whether they wish to do so twice. I am glad to

say we came down from the roof quite another way, or I think I

should have stayed up there unto this hour.

On the Monday morning I threaded the narrow winding streets, in

which a stranger inevitably loses his way, until I found the second

antiquarian treasure of this old city—the magnificent mansion of

Jacques Cœur, the Gresham of France. It is such a famous place,

this "House that Jacques built," that every child in Bourges will

point you the way.

If I were a rich merchant, with galleys upon every sea and trucks

upon every railroad (since one should suit one's illustrations to

the times in which one lives), I can imagine nothing more delightful

than the building for myself a palace such as this commercial prince

of the middle ages built for himself and his people; a home which

from top to toe, from balustraded roof to deep cellar, was

symbolical of his name, his trade, his tastes, his very humours. His

dwelling must have fitted Jacques Cœur as its skin fits an animal. All its quaint architectural corners seem, as it were, wrinkles and

creases, whereby it adapted itself to the nature and genius of the

man. We, in our day, know nothing of such a style of building. If we

want a large house we send for an architect, who submits his plans

to our enlightened judgment; allotting ample stairs, a sufficiency

of best bedrooms, kitchen, butler's pantry, &c. If rather less, then

rather cheaper; and as to making the slightest difference in style

on account of our late pursuits; as whether, for instance, we were a

retired candlestick-maker, or a lord chancellor, or a physician, the

very idea would savour of lunacy. Egalité, fraternité— stature,

are not we all alike in our in our physical wants, in our deep

content with bricks and mortar? Let us build and plaster our houses

with our own tails, like the beavers, only with somewhat less

finesse and ingenuity. We know already what the result will be we

run no unknown risk. It will be Baker-street on a small scale,

Victoria-street on a large one.

Not so Jacques Cœur. This man wished in dying to leave a beautiful

shell behind him, so that the passers-by might say "Here lived a

great merchant; he had a wife, sons, and a daughter, and numerous

domestics. He liked his money, but loved art more; he kept a negro;

he was pious, also loyal. He didn't mind fighting if needs must be;

but preferred commerce and politics. He loved Bourges, and Bourges

loved him; for he paid his workmen well." All this, and more,

Jacques Coeur contrived to write in legible characters on the walls

of his house, some of it on the outside, some of it on the inside.

To this day it testifies what manner of man he was; own brother to

Whittington and to Gresham; akin to the princes of Venice and of

Holland; a man of manifold energies, who abided by his family motto,

"à Cœurs riens impossible."

The pedestrian traveller, while pursuing the narrow street which

bears his wholly plebeian name (James Heart, neither more nor less),

turns suddenly through the ornamental gateway, whose door is adorned

with an elaborate knocker, the hammer of which strikes upon a heart,

stands transfixed in that elaborate court, and asks, "But who was

he, this man of ample wealth and ampler brain?" It is easy to

answer. He was a contemporary of Jeanne d'Arc, and did for his king

by his gold what she did by faith and the sword. Jacques Cœur and

the Maid of Orleans may be represented as upholding the crown of

France in those days. Charles VII. was not worth either of their

devotions, and Providence probably considered his abominable

ingratitude in bestowing upon him Louis XI. for a son. Jacques Cœur

was born at Bourges, his father being largely engaged in trade. Jacques wedded, while quite a young man, the daughter of the

provost; her name was Macée de Leopard. When he built his house

he paid due honour to his wife, whose portrait and family arms

appear in several places. He extended his father's trade immensely;

was concerned in the coinage both of Bourges and Paris—, sort of

master of the mint; and his thoughts were engrossed by large schemes

of commerce, full of their own poetry; for in 1452 he went to the

East to make personal acquaintance with men and places, and on his

return to France he fixed his commercial head-quarters at

Montpelier, covered the Mediterranean with his ships, and had agents

and commercial travellers in all directions, many of whom afterwards

became eminent, testifying to the sagacity of his choice. Does this

little description convey the idea of a real man? Not a mere

historical figure, buried in dry words, but a genuine creature,

rising from honour to honour; lending only too much money to his

king, sent on delicate foreign missions, even to the pope; getting

so alarmingly rich that jealous people naturally desired his fall

and pickings.

In person he was slight and nervously framed. His face was very

peculiar, and he had an astonishing forehead. Except that there was

a strong development of the imaginative element about the temples,

this countenance suggests to the modern beholder somewhat of a

likeness to Lord Brougham. It does not add to the unity of his

portrait that he caused himself to be drawn in the guise of an

angel, with tall wings and a quantity of yellow hair flying behind. That was

une petite fantaisie du moyen âge; the unmistakable

visage is there all the same.

This ugly genius being, as aforesaid, enormously rich, bought in the

year 1445 about four hundred and twenty-one years ago, a piece of

land situated on the ramparts of the town, and set to work to build. Tradition says it cost him

a hundred thousand golden crowns, which is,

I believe, somewhere about £240,000. On the outside, that which

backed upon the rampart and moat, it took the shape and aspect of a

fortress; on the town side it literally broke out, into blossom. The accompanying woodcut is necessarily on too small scale to give

other than an idea of the general effect of the court. It is

covered with symbolic sculpture, or with domestic portraiture. For

instance, the panels of the pointed tower upon the left are each

occupied by two servants, women sweeping with brooms (new, let us

hope); small retainers; a female, the housekeeper perhaps, giving

alms to a beggar; and half way up are himself and his wife. He holds

a hammer, the symbol of industry, called by a French proverb le clef

des arts. Over the kitchen door (right in the corner, with little

steps leading up to it) is a sculptured panel of cooks and

scullions, busy over their fire. One would need long ladders and

good eyes to enter into the spirit of these strange bas-reliefs,

which are of the funniest, the most familiar description. Of course

his handsomest room looked into this court, an the recess over the

entrance he set up a figure of himself riding upon his mule. The

chapel is within this gateway; it was very high before it was

barbarously divided into two storeys. You see the window shooting up

to the roof. Here it was that Jacques caused Italian artists to

paint himself, his wife, his children, and various relations, all in

the guise of adoring angels.

It is not to be supposed that Jacques Cœur could spend much time in

his handsome reception rooms. When at home he appropriated to

himself certain little round rooms in that strong tower at the back. The view is taken from what was the moat, now the Place de Berry. Observe that there are no windows near bottom. Some way up is his

study, his little domestic office, where he wrote his letters and

did up his accounts. Above that, fenced from the staircase by a

strong iron door and wonderful lock, which still works unwearied

after four hundred years of duty, was his vaulted strong-room. It is

said he had a hole made in the floor, through which he could pitch

his money and himself down into his study, supposing that robbers

were attacking his strong-room. The corbels in this room are

extraordinary. One is said to reveal the secrets of his future

disgrace; an interview, political perhaps, with Agnes Sorel, the

king's mistress, to which the king was a concealed party, perched up

in a tree. Jacques is represented as becoming suddenly aware of the

king's presence by seeing his face reflected in a fountain. It is

impossible to say if this is the true interpretation of this quaint

bit of sculpture. There is something peculiarly whimsical in the

idea of Jacques causing it to be portrayed in his secret

strong-room, as if to remind him of possible dangers in the future.

Above this room runs an external gallery, of which the balustrade is

ornamented with alternate hearts and cockle-shells, indicative of

pilgrimage. Here be came into near neighbourhood of the chimneys,

and consequently he trimmed their tops with the most delicate stone

frills. And along the roof line he laid a neat cover or hem of lead,

which he gilded with hearts and cockle-shells, and here and there a

little statue, such as that of monk, knight, or pilgrim. Under the

eaves of the observatory chamber is a portrait of his negro, hugging

his coffer; and a little further on an angel affably holding his

coat of arms. A shield in another place bears the arms of another

rich commercial family allied to his own—fleurs-de-lys interspersed

with bales of silk or wool. In a similar spirit, the roof of a fine

gallery is neither more nor less in construction than the reversed

keel of a ship; and the massive chimney-piece represents a fortress,

and has two little dormer windows atop, with folks looking out of

them.

Now does not the home represent the man? Is it not full of him even

to the present hour? Fancy him showing all these queer or poetical

devices to his admiring friends. Fancy Madame Cœur and her maidens

going busy about the household work amidst their own portraits, and

their own coats of arms, and their own mottoes, smiling at them from

every door-post and window-sill. Jacques Cœur

was great in the way of mottoes. Besides his chief one, which he

sculptured on a balcony overlooking the street,

"A vaillants cœurs

rien impossible,"

he had two others, deeply characteristic of the man he must have

been. This,―

"A close bouche,

Il n'entre mouche;" |

and this,—

"Entendre, taire,

Dire, et faire,

Est ma joie." |

And now for a sad ending to so great a man; sad in that he was

uprooted from his native place, and died an exile, though he found a

glorious death. He fell into disgrace with his king, probably

because he had lent him too much money. He was arrested, and his

property fell temporarily into the hands of the monarch, but was

afterwards partially disgorged, and one of his sons got possession

of this splendid dwelling. He himself, accused of several crimes,

such as coining bad money, selling arms to the infidels (that was

how they treated a matter of steam rams in those days), pressing men

to man his ships, selling a Christian slave who had taken refuge

with one of his captains, etc., etc., was condemned to banishment

and confiscation. Being, however, unlawfully detained in prison, he

contrived to escape, got to Rome, and found great favour with the

pope, Nicholas V., at whose death he was named by the successor in

St. Peter's chair captain of an expedition against the heathens. He

is supposed to have been wounded in some combat, for he is known to

have died in the island of Chios, and was buried in the church of

the Cordeliers, a not unfit ending, according to the ideas of those

days, for a merchant prince of France.

The Hôtel Jacques Cœur, now converted into the Hôtel de Ville

of Bourges, is by no means the only relic of the domestic

architecture of the renaissance existing in the city. The Hôtel de

Lallemand also owes its origin to a family of financiers. In 1487

Bourges was almost levelled to the ground by an awful fire;

two-thirds of the city suffered, the trade of the place was almost

burnt out, and never quite recovered. One Jean Lallemand, with his

two sons, having thus lost the house in which they dwelt, and which

must have been, like so many others, of sculptured wood, resolved to

rebuild it in fair and fine stone. It was done, and that which they

wrought is yet to be seen. In 1825, having hitherto been a private

house, it was bought by the municipality, and the Sœurs de la Sainte

Famine were installed therein. These-sisters teach eight hundred

little girls gratuitously. They show the hotel to strangers for a

trifling sum, which they devote to charity. The ceiling of the

ancient oratory is worked in panels, each one differing in subject. The court is ornamented with medallions, several of which were

spoilt in that fatal year, '93." To it are uniformly referred all

the vandalism of Bourges, just as in England we lay it all to that

unhappy Oliver Cromwell. The Hôtel Cujas is so called from having

been inhabited by a famous lawyer of that name, but it was not built

by him. It dates from 1515, somewhere about the date of the earliest

part of Hampton Court. It is of brick, with stone ornaments, very

graceful and beautiful. The great professor of law, Cujas, was an

elder contemporary of our Shakspeare; he died in 1590. In his

earlier life he accompanied the Duchesse de Berri to Turin. Possibly

Portia may have profited by his lessons. See the historic charm and

the romantic associations of these old houses!

Scattered through the steep and winding streets of Bourges are many

other fine old dwellings, which yet have no special name. There is

one in the Rue des Toiles, another in the Rue St. Sulpice, and were

it possible to penetrate the secret of many another, what

staircases, what vast apartments, what quaint sculpture, what

elegant columns might we not discover! The town is a treasury of

architectural art. Last year some gentlemen, supposed to be English,

came and bargained greedily for the ceiling of the oratory of the

Hotel Lallemand. They offered a mint of money for it; perhaps they

wanted to put it up in the Crystal Palace but, Dieu merci, they were

refused. The oratory was built three hundred years ago, for the

honour of God and the delight of men, not for a show, nor for

reference in an architectural dictionary. It is Berrickon, in

Bourges let it remain. We, who have Salisbury, Wells, Maplestead,

and many another glory of mediæval art, need not go begging and

stealing our neighbours' goods. If you wish to see the glorious

treasures of Bourges, church and city, come and look for them.

BESSIE R. PARKES.

―――♦―――

GARIBALDI.

WHEN the

convalescent hero of Aspramonte visited our shores two years ago,

and drove through our streets in a light-grey suit and a round hat,

reminding one forcibly of a second-rate swell at the sea-side, those

who, like the writer, had seen him often on the battlefield, in his

coarse red shirt and with no hat on at all, may have thought he was

hardly doing himself justice.

|

|

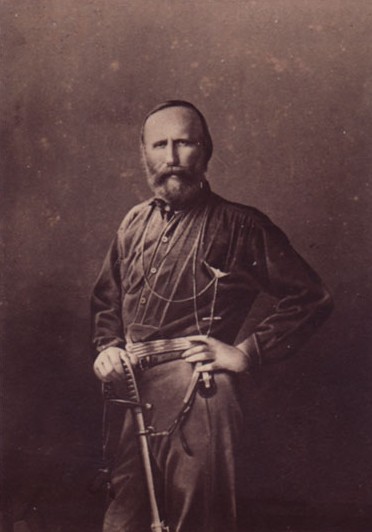

|

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 – 1882),

Italian patriot, military leader and national hero.

From a carte-de-visite. |

Very unconsciously, however, that great and simple gentleman went

about amongst us, wearing such a hat, perchance, because it was

cheap—such a coat because it was cool, and wondering, not without

gratitude and love, at the un-Italian "Hoorays" which cheered him by

day and woke him up in the night. Probably most of us who shouted

and stared gave him full credit for the prodigious results of the

last Italian campaign; but how many remembered that this was only

one of a long series, and, in many respects, the least arduous of

them all? The greatness of this man will be understood when his

whole life is better known; it will then be seen that there has

been an absolute unity of purpose throughout the whole of it, and

that every succeeding year has only served to fill in the details of

one and the same vast and romantic design. As some men are born with

an irresistible instinct for the chase, or a life at sea, so was

Garibaldi born with an instinct for conquest; and it is his great

glory never to have used it for purposes of self-aggrandisement, or

otherwise than as a means of elevating and relieving oppressed and

suffering humanity. The following pages are a very brief tribute to

the past life of Joseph Garibaldi.

1807-1836.

Garibaldi was Duke of Bavaria, A.D. 584, his ancestors having

curiously enough discarded the name of King. Leader of the people,

not their king, was as much a Garibaldi title one thousand three

hundred years ago as it has become since the well-earned distinction

of Joseph Garibaldi, born at Nice, July 22, 1807. His father was a

merchant; and it was no doubt whilst cruising about in the

Mediterranean that Joseph early acquired that love for the sea and

that mastery over ships which, combined with his later knowledge of

men and land service, has made him a perfectly amphibious commander.

The first sight of Rome kindled in his boyish heart a confused sense

of his country's greatness and of her degradation. As Luther brooded

over a reformed faith, as Columbus dreamed of a new world, so the

obscure Italian boy mused over the redemption of beautiful but

fallen Italy. "I everywhere sought for whatever might enlighten me,"

he writes; "for books, for persons whose breasts responded to my

own." One such, at least, he found in the eloquent St. Simonian

Emile Barrault, whose deep piety and burning patriotism left their

indelible impress upon his young disciple's heart. "Our country!"

exclaims Garibaldi. "I first heard him talk of Italy as 'Our

country!'"

He learned from him what was then the real condition of Italy, and

what were the hopes and the plans of that little band of patriots,

hardly one of whom has survived to see the triumph of liberal

opinions. His worst fears were confirmed. From Palermo to Venice,

from Venice to Savoy, from Rome to Naples, all was tyranny or

misrule. The insecurity of life and property throughout Sicily

betrayed a slovenly government. The brutal ignorance and indolence

of the low-browed and filthy Neapolitan told of long poverty and a

spirit hardly free enough to feel its own fetters. The swarms of

priests who muttered their venal masses in the Roman temples, or

walked about in their shabby cassocks, with eyes askance, and the

peculiar look of men at once sensual and ashamed; or the great,

gilt, dingy-red coaches, with the shrivelled, dingy-red cardinals

inside them, always going to and from the Holy Father's palace,

seemed to say plainly enough that the wolf had got into the

shepherd's coat, and exchanged his pastoral staff for a sceptre. Whilst, as the eye travelled northwards from Venice, west and south

all over the fair Lombard plain, the white-coated Austrians were

seen settling down everywhere, like a swarm of wasps in an orchard

when the fruit is ripe.

|

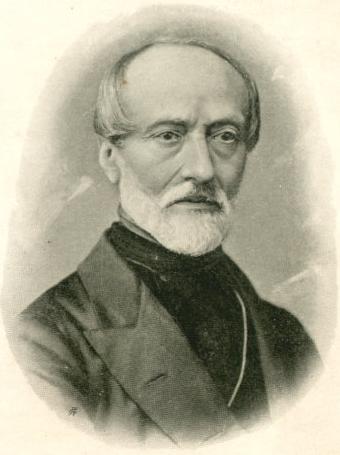

|

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805

– 1872),

Italian patriot, philosopher and politician.

From a postcard. |

Whilst Garibaldi was brooding in silence over these mournful facts,

he fell in with the young apostle of La Giovanna Italia—Mazzini. Mazzini, ablest of agitators, worst of leaders, first supplied him

with a definite creed, as he had already formulated the vague hopes

and aspirations of thousands all over Italy. A revolutionary paper

was started, and immediate action commenced. The enthusiasts who had

been favoured by Charles Albert, as Prince of Carignan, were frowned

down by Charles Albert, King of Sardinia, and the movement

consequently assumed that unconstitutional aspect which it has until

quite lately maintained. A descent upon Savoy, a few arrests, the

banishment of Mazzini to England, and the narrow escape of Garibaldi

in disguise, brought the first act of the Italian revolution to a

close. Italy was not sufficiently roused, the old powers were not

sufficiently shaken; the Sardinian cabinet seemed growing more

bigoted every day. The time was not yet.

SOUTH AMERICA. 1836-1847.

The scene now changes to the wide pampas plains, tropical forests,

and broad lake-like rivers of South America. The voices of

patriotism were silenced for a time in Italy, but other kindred

voices seemed to call the world-wide patriot across the Atlantic.

The Republic of Rio Grande was struggling with the Brazilian

government for its freedom. In 1836 Garibaldi

sailed into its smooth and commodious harbour. He found the

Republican President, Ben Gonzales, and his brave secretary, Livio

Zambeccari, in prison.

He immediately placed himself at their disposal; and receiving

orders to confiscate Brazilian property by sea and land, took

command of the entire Republican fleet, consisting of one small

smack with a gallant crew of sixteen men. Sailing proudly out of the

harbour mouth, he landed on a rocky island hard by. "I stretched out

my arms," writes the chief, "with proud and happy emotions, and my

lips burst forth into an eagle cry from his highest eyrie. The

boundless ocean was my empire, and then I took possession of it." Presently

came sailing out of the harbour an unsuspicious vessel,

with the Brazilian flag; the little crew were down upon it in a

moment. Under the very batteries of Rio the prize was seized without

bloodshed. The crew were politely landed some way down the coast;

the Garibaldians scuttled and sank their own poor little ship and

sailed off with a fine cargo of coffee. But before the cargo could

be sold at Monte Video, suspicions were aroused; an order for the

arrest of the ship and crew was out. The cargo had indeed been sold

to a merchant, but had not been yet paid for; they must either fly

instantly with loss, or surrender at discretion. There was an hour

to spare. Garibaldi, with a loaded brace of pistols in his belt, and

disguised in a long cloak, strode through the streets of Monte

Video, appeared before the astonished merchant as he was quietly

smoking his pipe after dinner; walking close up to him, he applied a

pistol to his breast, with, "My money!" Every farthing was paid,

and the ship slid out of the harbour with the sunset wind.

The second act of such a drama of suffering and valour as the world

has perhaps never witnessed was now fairly begun. Whilst running

between two Brazilian ships, who accompanied him for half an hour,

sweeping his decks with their murderous broadsides, his crew was

decimated and he was shot through the neck. Slowly recovering from

this wound, he was seized on landing by the notorious Rosas,

dictator of Buenos Ayres, and by the directions of his subordinate,

the brutal Millau, hung up for two hours by his thumbs, and nearly

beaten to death; he was then thrown into a loathsome prison and

tortured for many months. Nothing, however, could extract from him

the names or the plans of his colleagues. But freedom and health

never long forsook their darling, and he was soon again cruizing

about the lagunes of Los Patos, making small prizes and resisting

fearful odds. Nor was he less active by land: not unfrequently,

after firing shot and chain cable away, his amphibious crew had to

leap into the water and gain the woods. This was the signal for the

well-organized bands of Brazilian guerillas to turn out against him; here it was, in numberless encounters, that Garibaldi established

his solitary supremacy in this style of war. Garibaldi is a very

sure and a very cool shot, as well as a consummate swordsman. On

one occasion he was surprised in his wooden barracks by a colonel

and one hundred and fifty horse. Alone with his cook and sixty

loaded muskets, he shot down all their officers, and kept the band

at bay till his own handful of men came rushing back through the

enemy's rear, and completed the rout.

|

|

|

Ana Maria de Jesus

Ribeiro da Silva (Anita

Garibaldi),

(1821 - 1849) |

But the loss of many brave companions began to weigh upon the

spirits of the chief: the blood of these noble hearts was being

poured out like water, and yet hardly could the Republic be called

safe for an hour. To complete his trouble, two of his ships were

wrecked; in his own were six of his most devoted companions; not one

of them escaped, and for a brief season at least he seems to have

been prostrated with the deepest grief. Such seasons, it would seem,

are not unfavourable to the development of the domestic affections. A young Brazilian lady, Anita by name, consoled the hero for the

loss of his companions. Dark, like the tropical Creoles, possessed

of singular grace, perfect physique, and endowed with a high and

dauntless soul, the very counterpart of her lover's, a more perfect

marriage could not be conceived, and the cannon in the harbour of

Laguna were the bells which rang their wedding chimes. The Brazilian

commander, who had resolved to crush out the rebellion, had

blockaded the town. The Republican fleet sailed out and offered

battle. For five hours the cannonade was incessant. Garibaldi's own

ship was almost down to its gunwales in the water, but he never

ceased firing; his other ships were riddled with shot, but not one

gave in. At last the Imperialist squadron, fairly exhausted with the

repulse, drew off at the very moment when their enemies were

sinking, decimated but victorious.

Thus commenced Anita's honeymoon. She pointed the first gun, and

constantly took the place of the dead and wounded. When knocked down

by the wind of a round shot, and entreated to go down below, "I

will go," she said, "but only to drive out the cowards that have

sought concealment there." She soon dragged up three hapless

wretches, who from that hour fought like lions.

At the battle of Coritibani she was taken prisoner whilst caring for

the wounded. She escaped, leaped on a fiery horse, and galloped to

the nearest forest. There lay between her and her husband sixty

miles, a wilderness of giant reeds and towering pines alive with

venomous reptiles and beasts of prey. Night and day she urged on her

brave steed. At length emerging upon the banks of the river Canoas,

she swam the swollen torrent and reached her husband in a state of

complete exhaustion, not having tasted food for four days! In a

moveable camp, with no physician near, and hourly expecting an

assault from the great guerilla, Colonel Moringue, she bore her

first son, Menotti (1840). "Anita," writes her husband, "a few days

after her confinement had been compelled to get on horseback with

her poor babe laid across the saddle, and then to take refuge in the

woods in a pitiless storm!" These frequent wanderings in the woods

were full of extreme suffering for all the fugitives. The rain often

poured in torrents for days, the thick matted undergrowth of reeds

and pampas-grass afforded shelter for swarms of poisonous snakes,

and often proved an almost impassable barrier. The best guides lost

their way. The provisions were soon gone; many died of fever,

others perished with cold, hunger, and exhaustion. Meanwhile it was

going ill with the Republic of Rio; the chiefs were at variance

with each other; the great question of independence was degenerating

into a party squabble. For six years Garibaldi had served them

faithfully, until at length disappointed and tired out, he collected

a drove of cattle, and abandoning for ever a cause which had ceased

to be worthy of him, set his face towards the south, and arrived at

Monte Video in 1841. He seems to have supported himself here by

teaching mathematics in the schools, and carrying round, as he

himself tells us, "samples of every kind, from Italian paste to

Roman silks;" but the Monte Videans, who were at war with the

dictator Rosas, induced him to join their cause, and the formation

of the famous "Italian Legion" was the immediate result. This little

band repeated at Monte Video the famous exploits of the Republicans

at Rio. Time would fail me to tell of the gallant defence of the

town and harbour of Monte Video; how the Garibaldian ships sailed

forth to offer battle to the whole Brazilian fleet, whilst the

inhabitants thronged the quays and roofs of the houses until the

whole bay resembled a vast amphitheatre crowded with spectators; and

how the Brazilian fleet thereupon declined the combat. Nor can we

pause over the numerous encounters with the terrible Ouribes, who

gradually got so great a distrust of himself that he was wont to give way or ever they could get at him with the bayonet.

On February 8, 1846, a day for ever memorable, Garibaldi fought his

last and greatest American battle, with one hundred and ninety of "The Legion" against one thousand two hundred horse and three

hundred infantry, on the plains of San Antonio. "My sons," he said,

as the foe was seen charging up from the distance, "the enemy are

many, we are few; more glorious will be the victory. Be steady,

reserve your fire until they are close on you—then fire, and at them

with the bayonet." But the enemy reserved their fire, and at sixty

yards poured in a deadly volley. Many of the legion fell, the rest

stood motionless, without reply. In an instant, as the enemy came on

with a rush, Garibaldi had galloped to the front, and "Fire!" then

"Charge!" and the little band passed clean through the enemy's

ranks, and attacked the cavalry flanking them. The engagement ended

with a "fighting retreat," and when the sheltering forest was

gained, and the night came down, thirty of the legion were left dead

upon the field, and fifty-three were badly wounded. The report of

this battle spread like wildfire through North and South America,

and reaching Europe, seemed in the eyes of all Italian patriots to

surround the already beloved name with a prophetic glory.

ITALY. 1847-1848.

On March 27, 1847, with about one hundred of the legionaries,

Garibaldi sailed for Europe. The times were growing ripe. The whole

of Italy, like the soil around Vesuvius, was volcanic with the

suppressed fires of revolution; sudden jets were seen flaming up

from time to time. Suppressed in the north, the fire would burst out

in Rome, and then for a season explosions would take place in

Sicily, and spending themselves, pass over to Naples and the

mainland. Venice, Milan, Rome, Palermo, Naples, these were the great

national stations between which the electric shocks of Italian

freedom were to vibrate. But the war commenced with a fatal blunder;

the services of Garibaldi and his legion were rejected by Charles

Albert, then at the head of a popular movement to drive the

Austrians out of Italy. Indeed it was more than suspected that the

king would have been glad to see that section of liberalism

represented by our hero extinguished. The government feared the

spirit of revolution—the king, a formidable and popular rival. Garibaldi, believing both himself and the cause betrayed, issued his

famous proclamation of the 12th August, 1847, declaring war against

both the traitor-king, Charles Albert, and the Austrians. Doubtless

there were mistakes on both sides. The king had been wrong, but his

great subject had also erred in violently severing interests which

were in fact identical. Of course the quarrel between them could

never be patched up, and it is hardly to be regretted when we

remember how wisely in his treatment of Garibaldi, Victor Emmanuel

has profited by his predecessor's mistake.

After an armistice had been agreed upon between Charles Albert and

the Austrians, Garibaldi, with about five thousand men, attempted to

continue the war; but it was the old story of a kingdom divided

against itself. No permanent territorial results were effected for

Italy; the Quadrilaterals still frowned, Venetia still mourned her

independence; but those few hand-to-hand encounters with the

Austrians, that apparently fruitless and desultory warfare on the

lakes, established for ever Garibaldi's prestige, and inspired Italy

with that blind confidence in her champion which she has never since

lost.

Towards the close of the campaign Garibaldi was attacked with the

marsh fever, which soon turned to typhus. There seemed little chance

of his recovery. He lay prostrate and almost insensible at Lerino.

One cry only had power to rouse him, "The Austrians!" In the

confusion and panic caused by the chief's illness, a body of twelve

hundred Austrians rushed into the little town, and the slaughter had

already commenced in the streets. The fever was forgotten, the dying

man sprang from his couch; in another moment he was at the head of

his legion, and the Austrians were flying before him. Without

resting, the troops pushed on to Varese, here they discovered that

the Austrians had retired to cut off their retreat to Switzerland—a

barrier consisting of the finest army in the world must be crossed. There was not a moment to lose, and at Mazzarene, Garibaldi, with

five hundred of the "legion," forced a bloody passage through an

army of ten thousand Austrians, and passed safely into Switzerland. Thus ended the campaign in North Italy, but only to make way for the

more important events in the south, which were themselves but a

brief and fiery prelude to the great and apparently irremediable

catastrophe.

THE SIEGE OF ROME. 1848-1849.

In the fall of the year 1848, the Pope, hearing that the "Great

Bandit" was collecting his forces at Ravenna, ordered a couple of

Swiss regiments to go and "throw Garibaldi and his followers into

the sea." A few days afterwards, the Pope himself was obliged to fly

to Gaeta—the standard of the Roman Republic was raised—the

Triumvirate proclaimed, and Garibaldi himself within the walls of

Rome. No blood had as yet been shed; but the great struggle was

close at hand. The Pope was the head of the Catholic world. France

might be well disposed towards the Republic, but the rights of the

Holy Father must be protected. Thirty-five thousand troops, under

Cavaignac, advanced upon the city; behind them loomed the Austrians

in the distance even Spain sent a few regiments, and the Neapolitan

army approached from the south. Thus hemmed in by four enemies, with

a scanty horde of brave, but many undisciplined troops—insufficient

arms and ammunition, Garibaldi prepared for the defence of Rome. On

the morning of April 30, 1849, Garibaldi attacked the French army

outside the gates. He led charge after charge in person, and after

fighting for seven hours the French were compelled to retreat along

the road to Civita Vecchia, leaving three hundred prisoners in the

hands of the Romans, and fifteen hundred killed and wounded. This is

not the only occasion in which Garibaldi has defeated some of the

finest troops in the world in the open field. The Austrians fared no

better at Varese and Como; and when we hear that the Guerillero

would soon be annihilated if he attempted to oppose either France or

Austria openly, it is worth while to remember that he has more than

once fairly repulsed them both. Upon this occasion the French were

so crippled that they prayed for an armistice, and Garibaldi,

finding himself at liberty, immediately set off to meet the

Neapolitans, who were advancing upon Rome. On these expeditions he

took very few with him—a small band of picked officers and veterans,

most of them belonging to the Italian legion. The chiefs were

mounted on horses; each was armed with heavy pistols, and carried a

long whip; they wore the red shirt and the Roman felt hat. The men

never knew where they were going to; their movements were often as

intricate as they were rapid; Garibaldi alone held the threads of

the tangled skein. Like a magician—he shook his wand, there was no

army; he beckoned, and men came up from the woods and down from the

hills, charged the enemy who the moment before thought themselves in

a desert, charged back again, and disappeared, leaving the

bewildered foe nothing to charge in return, and very little left to

charge with. The poor Neapolitans, who were great cowards, and very

superstitious, appear to have advanced the first time with tolerable

pluck, and to have been repulsed with some loss, but the second time

they met the enemy they fled so fast that Garibaldi was unable to

overtake them, and gave it up.

The figure of the mounted chief, in the red shirt, filled them with

supernatural terrors; the rumour had got abroad that the Devil

himself was commanding in person. Sabres blessed by the Pope were

shivered to bits against him; and even holy silver bullets would

not hit him. Leaving his Southern foes with these satisfactory

convictions, Garibaldi hurried back to Rome, just as hostilities

were recommencing.

During the truce the French had received overpowering

reinforcements, and proceeded further to improve their position by a

signal act of treachery. Twelve hours before the conclusion of the

armistice, as the clocks of the city were striking midnight, on the

3rd of June, a French column glided through the darkness towards the

Villa Pamphili.

"Who goes there?" cried the sentinel.

"Viva l'Italia," said the French. In another moment the sentinel was poinarded, and the Villa Pamphili was in the enemy's hands.

"I was roused," says Garibaldi, "at three o'clock, by the sound of

cannon.

I found everything on fire. When I arrived at the St. Pancrazio

Gate, the Villas Pamphili, Corsini, and Valentina, were all taken." These were the keys of Rome's defence; and placing himself at the

head of a column, Garibaldi led a furious charge. "For a moment the

Villa Corsini was ours," he writes; "that moment was short, but it

was sublime; the French brought up all their reserve, and fell upon

us all together. I have seen very terrible fights. I saw the fight

of Rio Grande; I saw the Bayada; I saw the Salto San Antonio; but

I never saw anything comparable to the butchery of the Villa Corsini!" The Corsini was not retaken, and thus from the first day the fate of

Rome was decided.

"From the moment," says Garibaldi, "that an army of forty thousand

men, with thirty-six pieces of siege cannon, can perform their works

of approach, the taking of a city is nothing but a question of time. The only hope it has left is to fall gloriously."

We cannot follow the history of this romantic siege. The people were

fighting not for victory, which they felt was lost, but for a

principle—to show the whole of Italy that they were in earnest―that

they would have Rome sooner or later. Every day now beheld deeds of

unparalleled heroism. Here might be seen the young Colonel Manara,

who led the flower of the Lombard chivalry, riding up to the

battery's mouth and sabring the gunners in person. The tried Colonel

Medici was ubiquitous, and second only to Garibaldi in the order and

completeness of his tactics. In the pauses of the combat Cicero Vacchio, with blood-stained shirt and sword still reeking with the

slaughter, poured forth a torrent of eloquence and rekindled in the

fainting troops the expiring flames of patriotism; whilst Ugo Bassi,

in his monk's dress, held the crucifix before the eyes of the dying,

and careless of the bullets which showered around him, pointed to

the freedom of the skies. He was captured on the barricades whilst

supporting the head of a dying soldier, but restored by the French

general to Garibaldi. His devotion gained the admiration of both

friends and foes; he was often in the thickest of the fight, but

carried nothing but the cross.

Garibaldi's daring station was in a tower of the Casino Savorelli,

overlooking the trenches and within half carbine shot of the French

tiralleurs. "It was curious," he says, "to see the storm of balls

which rained around me. The balls caused the whole strong house to

shake as if from an earthquake; several times I had my meals served

in the steeple in order to give the French marksmen the amusement of

trying to hit me."

On the 13th of May the French opened a general bombardment, breaches

were made in several places, the earth was also mined, and the enemy

came up under ground into the city. A tremendous fight now ensued,

so tremendous, that a momentary truce followed, both armies were

completely exhausted. The streets were choked with mutilated bodies,

all the Roman gunners had been killed at their guns, the batteries

had kept on firing till every gun was dismounted. A deep silence

succeeded to the clash of arms and rattle of musketry, the living

seemed stunned and paralysed, a heavy sulphurous cloud hung over the

city; but on the 29th the demons of war rose, as it were, with a

yell from the heaps of the dead, and again besiegers and besieged met in the shock of a deadly hand-to-hand encounter. Night brought no

cessation of hostilities. A violent storm had been gathering

unheeded, and burst towards sunset in all its fury over the city. "Ah, it was a terrible night!" writes Garibaldi. "The artillery and

fury of the skies mingled with that of earth, the thunder answered

responding to the cannon, the lightning ran its livid lines across

the path of the bombs." The last struggle was at hand. Two hundred

paces behind the walls of Rome is the ancient inclosure of Aurelian; into this Garibaldi threw a large body of troops, with orders to

defend it to the last. Their numbers were soon diminished to about

half, their guns silenced, but no word was spoken of

surrendering—they continued to advance, to fire, to drop. Then was

seen a thing unheard of in the annals of war—a reserve of the

wounded volunteered to take their turn in the trenches, and men were

seen with the blood still trickling from their breasts, with

bandaged heads and broken limbs, fiercely spending themselves in a

last convulsive effort. On the 29th, at midnight, Garibaldi went

into the Aurelian trench to lead the last charge. "On that terrible

night," writes Checchi, an eye-witness, "Garibaldi was great

indeed, greater than anybody had ever known; his heavy sword flew

like lightning, every one he smote fell dead before him, the blood

of one washed from his steel the blood of another,—we trembled for

him, but he was unwounded—he stood firm as destiny."

At two o'clock Garibaldi was recalled by the deliberative assembly

under Mazzini, then sitting in the capitol. "When I appeared at the

door of the chamber," he writes, "all the deputies rose and

applauded. I looked about me and upon myself to see what it was that

awakened their enthusiasm. I was covered with blood, my clothes were

pierced with balls and bayonet thrusts, my sword was jagged and bent

and stood half out of the scabbard, but I had not a scratch about me!"

VENICE. 1849-1850.

On the 2nd of July the Triumvirate resigned their power, and the

authorities undertook to treat with General Oudinot. On the same day

Garibaldi assembled the Roman troops in the great square in front of

St. Peter's, and addressed them as follows:―

"Soldiers, all I have to offer you is hunger, thirst, the ground for

a bed, the burning sun, as the sole solace for your fatigues; no

pay, no barracks, no rations; but continual alarms, forced marches,

and charges with the bayonet. Let those who love glory and do not

despair of Italy, follow me."

About four thousand infantry and eight hundred horse, with baggage

waggons and artillery, followed him in that memorable retreat of the

2nd of July, 1849, which would alone be sufficient to establish the

general's title to military fame. At the very time the French were

watching the gates the whole of Garibaldi's army passed out of the

walls unobserved, and were fifteen miles off by daybreak. To give an

idea of the skill and precision with which the General's movements

were executed, we need only say that within an hour after the last

column left Orvieto the French in pursuit occupied that town.

We hasten to draw a veil over the sad scenes of wandering,

suffering, and disappointment which now followed. Many of his ablest

generals were killed, the troops were daily thinned with privation

and discouragements of every kind, and desertion was frequent in the

ranks. With diminished forces, ill supplied and worn out with

fatigue, the dauntless defender of Rome turned his eyes towards

Venice. He had still but one programme—as long as a man would follow

him he was ready to fight for Italy. At San Marino he was hemmed in

by overpowering numbers, and to avoid surrendering disbanded his

army, and then with sixty of his dearest officers and men cut his

way through the Austrians and reached the coast. He was going with

that devoted band to capture Venice!

In the grey of an August morning, with a fair wind blowing, they set

sail in thirteen fishing-boats. At sunset they came in sight of

Venice; two gunboats steamed out of the lagunes towards them. Garibaldi gave the order to tack for the shore. Could they have

reached the coast in time, escape, if not victory, would have been

possible; but the cowardly sailors lost their heads—in a moment the

flotilla was in confusion, and the gunboats had opened a point-blank

fire. Only four boats ever reached the shore; in the last was

Garibaldi, Anita, Ugo Bassi, Cicero Vacchio, and a few more devoted

followers. Even this small band dared not remain together on the

enemy's soil. Ugo Bassi and Cicero Vacchio were soon captured and

shot by the Austrians, and Garibaldi fled with but one officer, and

his wife Anita, then far advanced in pregnancy. This devoted woman

had accompanied her husband all through the Lombard campaign, and

had followed him to Rome. Now, in almost a fainting state, weakened

by every kind of suffering and privation, she was hurried in a

rickety carriage over rough roads, obliged at times to hide in rocks

and forests, for the Austrians were in pursuit, and a price was set

upon the heads of all the Garibaldians. Arriving on the ground of

the friendly Marquis Guiccioli, Garibaldi carried his wife into the

nearest cottage, where, as soon as she had drank a little water, she

expired in his arms. She was hastily buried in a neighbouring field; and here, parting at once with his wife and the last of his staff

officers, the Dictator of Rome, who a few months before had been a

victorious general at the head of eighteen thousand patriots, found

himself a proscribed and lonely wanderer in a hostile land.

In one of the back streets of New York city, in the year 1850, there

was a little shop devoted to the sale of soap, but especially

candles. At the back of that shop might be seen any day, and all

day, a man with a bronzed complexion, tall forehead, and reddish

beard, deeply engaged in dipping wicks into a large bowl of melted

tallow. This was Joseph Garibaldi, the hero of Monte Video and the

hope of Italy.

H. R. HAWEIS.

(To be continued.)

―――♦―――

A STROKE OF GOOD FORTUNE:

BY THE AUTHOR OF "SHIRLEY HALL," ETC.

IT was late in the autumn of 18— when I left my lodgings in Ramsgate

where I had been residing during the season, to return to London. As

I was not pressed for time, I proposed to journey by the steamboat

instead of by rail. Rightly or wrongly, I considered the sea air and

iodine obtained by the voyage a most efficacious alterative, and one

especially well adapted to the constitution of a sedentary literary

man.

There were few passengers on board the boat, as by far the greater

portion of the visitors had already left Ramsgate; besides the day

was squally and threatened rain. We left the harbour, and went on to