|

The English Woman's Journal

(October 1860)

VICTORIA PRESS

BY

EMILY FAITHFULL.

(This paper was presented to a meeting of the

National Association for the Promotion of Social Science [NAPSS]

in August, 1860.)

When we remember the impetus given to the question of female employment by

the discussion which took place at the meeting of this Association, at

Bradford, last year, it seems but natural to suppose that one of the

practical results of that discussion will be a matter of great interest to

the present audience, on which account I venture to bring before your

notice the origin and progress of the Victoria Press.

It has often been urged against this Association that it does 'nothing but

talk'; but those who fail to see the connection existing between the

promotion of

social science and the development of that science in spheres of practical

exertion, must acknowledge that if all discussions led to as much action

as

followed that which took place upon the employment of women, the

accusation would fall to the ground. A thorough ventilation of the

question of the

necessity for extending the field of woman's employment, was at that time

imperatively needed. The April number of the Edinburgh Review for 1859 had

contained a fuller account of the actual state of female industry in this

country than perhaps had ever been previously brought before the notice of

the

public. The question had begun to weigh upon thoughtful minds, and even to

force itself upon unwilling ones, and the notion that the destitution of

women

was a rare and exceptional phenomenon, was swept away, as The Times

observed, when Miss Parkes, addressing this Association at Bradford, did

not

hesitate to ask whether there was a single man in the company who had not,

at that moment, among his own connections, an instance of the distress to

which her paper referred. The discussion which followed operated in a most

beneficial manner; it forced the public to put prejudice aside, and to

test the

theory hitherto so jealously maintained, that women

were, as a general rule, supported in comfort and independence by their

male relatives. The press then took up the question, and, with but few

exceptions, dealt by it with a zeal and honesty which aided considerably

in the partial solution of a problem in which is bound up so much of the

welfare

and happiness of English homes during this and future generations.

One by one the arguments for and against female employment, apart from the

domestic sphere, were brought forward and examined; and where

objections arising from feeling could not be vanquished by argument, the

simple fact of women being constantly thrown upon the world to get their

daily

bread by their own exertions, left the stoutest maintainers of the

propriety of woman's entire pecuniary dependence upon man, without an

answer.

In the November following the Bradford meeting, the council of this

Association appointed a committee to consider and report on the best means

which

could be adopted for increasing the industrial employments of women; in

the course of the investigation set on foot by this committee, of which I

was a

member, we received information of several attempts made to introduce

women into the printing trade, and of the suitableness of the same as a

branch

of female industry. A small press, and type sufficient for an experiment,

were purchased by Miss Parkes, who was anxious to test, by personal

observation, the information thus received. This press was put up in

a private room placed at her disposal by the kindness of a member of this

Association. A printer consented to give her instruction, and she invited

me to share in the trial. A short time sufficed to convince us that if

women were

properly trained, their physical powers would be singularly adapted to fit

them for becoming compositors, though there were other parts of the

printing

trade—such as the lifting of the iron chases in which the pages are

imposed, the carrying of the cases of weighty type from the rack to the

frame, and the

whole of the presswork (that is the actual striking off of the sheets),

entailing, particularly in the latter department, an amount of continuous

bodily exertion

far beyond average female strength.

Having ascertained this, the next step was to open an office on a

sufficiently large scale to give the experiment a fair opportunity of

success. The

machinery and type, and all that is involved in a printer's plant, are so

expensive that the outlay would never be covered unless they were kept in

constant

use. The pressure of work, the sudden influx of which is often entirely

beyond the printer's control, requires the possession of extra type in

stock, these

and other economical reasons which will be easily understood

by all commercial men, necessitate the outlay of a considerable amount of

capital on the part of anyone who wishes to turn out first-class printing.

A

gentleman, well known for his public efforts in promoting the social and

industrial welfare of women, determined to embark with me in the

enterprise of

establishing a printing business in which female compositors should be

employed. A house was taken in Great Coram Street, Russell square, which,

by

judicious expenditure, was rendered fit for printing purposes; I name the

locality because we were anxious it should be in a light and airy

situation, and in a

quiet respectable neighbourhood. We ventured to call it the Victoria

Press, after the sovereign to whose influence English women owe so large a

debt of

gratitude, and in the hope also that the name would prove a happy augury

of victory. I have recently had the gratification of receiving an

assurance of Her

Majesty's interest in the office, and the kind expression of Her

approbation of all such really useful and practical steps for the opening

of new branches of

industry for women. The opening of the office was accomplished on the 25th

of last March. The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women

apprenticed five girls to me at premiums of £10 each; others were

apprenticed by relatives and friends, and we soon found ourselves in the

thick of the

struggle, for such I do not hesitate to call it; and when you remember

that there was not one skilled compositor in the office, you will readily

understand the

difficulties we encountered. Work came in immediately, from the earliest

day. In April we commenced our first book, and began practically to test

all the

difficulties of the trade. I had previously ascertained that in most

printing offices the compositors work in companies of four and five,

appointing one of the

number to click for the rest, that is, to make up and impose the matter,

and carry the forms to the press-room. The imposition requires more

experience

than strength, and no untrained compositor could attempt it, and I

therefore engaged intelligent, respectable workmen, who undertook to

perform this duty

for the female compositors at the Victoria Press.

I have at this time sixteen female compositors, and their gradual

reception into the office deserves some mention. In the month of April,

when work was

coming in freely, I was fortunate enough to secure a skilled hand from

Limerick. She had been trained as a printer by her father, and had worked

under

him for twelve years. At his death she had carried on the office, which

she was after some time obliged to relinquish, owing to domestic

circumstances.

Seeing in a country paper that an opening for female compositors had

occurred in London, she determined on taking the long

journey from Ireland to seek employment in a business for which she was

well competent. She came straight to my office, bringing with her a letter

from

the editor of a Limerick paper, who assured me that I should find her a

great assistance in my enterprise. I engaged her there and then; she came

to work

the very next day, and has proved herself most valuable.

I have now also three other hands who have received some measure of

training in their fathers' offices, having been taught by them in order to

afford help

in any time of pressure, or in case any opening should present itself in

the trade, of which a vague hope seemed present to their mind. From

letters which

I have received from various parts of the country, I find that the

introduction of women into the trade has been contemplated by many

printers. Intelligent

workmen do not view this movement with distrust, they feel very strongly

woman's cause is man's; and they anxiously look for some opening for the

employment of those otherwise solely dependent on them.

Four of the other compositors are very young, being under fifteen years of

age; of the remaining eight, some were apprenticed by the Society for

Promoting the Employment of Women, having heard of the Victoria Press

through the register kept at Langham Place; and others through private

channels. They are of all ages, and have devoted themselves to their new

occupation with great industry and perseverance, and have accomplished an

amount of work which I did not expect untrained hands could perform in the

time. I was also induced to try the experiment of training a little deaf

and dumb

girl, one of the youngest above mentioned; she was apprenticed to me by

the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, in the Old Kent Road, at the instance of

a

blind gentleman, Mr John Bird, who called on me soon after the office was

opened. This child will make a very good compositor in time, her attention

being naturally undistracted from her work, though the difficulty of

teaching her is very considerable, and the process of learning takes a

longer time.

Having given you a general description of my compositors, I will only add

that the hours of work are from nine till one and from two till six. Those

who live

near, go home to dinner between one and two; others have the use of a room

in the house, some bringing their own dinners ready cooked, and some

preparing it on the spot. When they work overtime, as is occasionally

unavoidable, for which of course they receive extra pay per hour, they

have tea at

half-past five, so as to break the time.

It has been urged that printing is an unhealthy occupation. The mortality

known to exist among printers had led people to this conclusion, but when

we

consider the principal causes producing this result, we find it arises in

a great measure from removable evils. For instance, the imperfect

ventilation, the impurity of the air being increased by the quantity and

bad quality of the gas consumed, and not least by the gin, rum, and brandy, so freely

imbibed by

printers. The chief offices being situated in the most unwholesome

localities, are dark and close, and thus become hotbeds for the

propagation of phthisis [ED—pulmonary tuberculosis].

In the annual reports for the last ten years of the Widows' Metropolitan

Typographical Fund, we find the average age of the death of printers was

forty-eight years. The number of deaths caused by phthisis and other

diseases of that class, among the members in the ten years ending December

31,

1859, was 101 out of a total number of 173, being fifty-eight

three-fourths [58¾] per cent of the whole.

It is too early yet to judge of the effect of this employment upon the

health of women, even under careful sanitary arrangements; but I may state

that one of

my compositors, whom I hesitated to receive on account of the extreme

delicacy of her health (inducing a fear of immediate consumption, for

which she

was receiving medical treatment) has, since she undertook her new

occupation become quite strong, and her visits to her doctor have entirely

ceased.

The inhalation of dust from the types, which are composed of antimony and

lead, is an evil less capable of remedy. The type when heated emits a

noxious fume, injurious to respiration, which in course of years

occasionally produces a partial palsy of the hands. The sight of the

compositor is

frequently very much injured, apparently by close application to minute

type, but probably, as Mr H. W. Porter remarks in his paper read before

the

Institute of Actuaries, from the quantity of snuff they take, which cannot

fail to be prejudicial. This habit, at all events, is one from which we

cannot

suppose that the compositors of the Victoria Press will suffer.

It has also been urged that the digestive functions may suffer from the

long-continued standing position which the compositor practises at case. This, I

believe, nothing but habit has necessitated. Each compositor at the

Victoria Press is provided with a high stool, seated on which she can work

as quickly

as when standing.

There is one branch of printing which, if pursued by the most cultivated

class of women, would suffice to give them an independence—namely,

reading

and correcting for the press. Men who undertake this department earn two

guineas a week; classical readers, capable of correcting the dead

languages,

and those conversant with German and Italian, receive more than this. But

before the office of reader can be properly undertaken, a regular

apprenticeship to printing must have been worked out; accuracy, quickness

of eye, and a thorough knowledge of punctuation and grammar, are not

sufficient qualifications for a reader in a printing office; she must have

practically learnt the technicalities of the trade. And I would urge a few

educated

women of a higher class to resolutely enter upon an apprenticeship for

this purpose.

But for compositorship it is most desirable that girls should be

apprenticed early in life, as they cannot earn enough to support

themselves under three or

four years, and should, therefore, commence learning the trade while

living under their father's roof. Boys are always apprenticed early in

life, at the age of

fourteen; and if women are to be introduced into the mechanical arts, it

must be under the same conditions. I can hardly lay enough stress upon

this point;

so convinced am I of its truth, that I now receive no new hands over

eighteen years of age.

Many applications have been made to me to receive girls from the country;

but the want of proper accommodation for lodging them under the necessary

influence has hitherto prevented me from accepting them, but I have now

formed a plan for this purpose, and when I am assured of six girls from a

distance, I shall be able to provide for their being safely lodged and

cared for.

In conclusion, I will only attract your attention to the proof of our

work; for, while I am unable to produce the numerous circulars,

prospectuses, and reports

of societies which have been accomplished and sent away during these six

months in which we have been at work, I can point to copies of The English

Woman's Journal, a monthly periodical now printed at the Victoria Press,

and also to a volume printed for this Association, both of which can be

obtained

in the reception room, and which will, I think, be allowed to be

sufficient proof of the fact that printing can be successfully undertaken

by women.

|

|

|

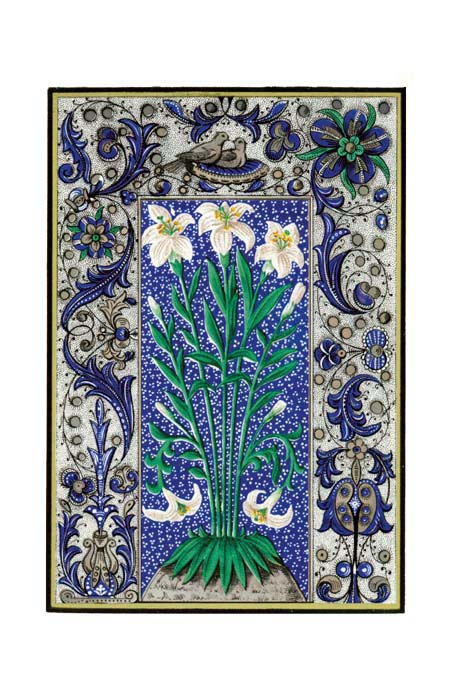

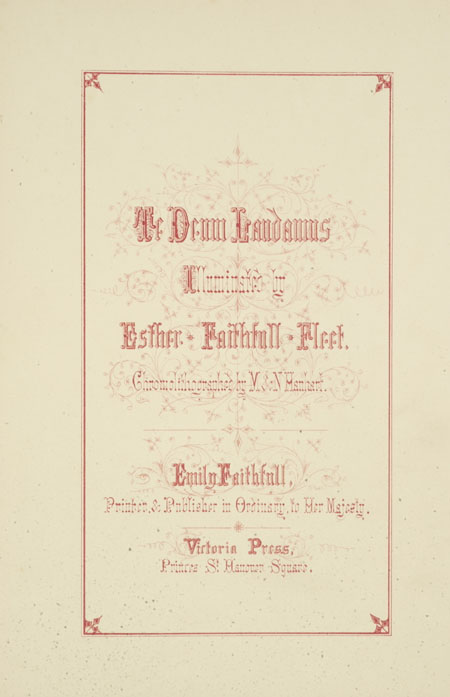

TE DEUM

LAUDAMUS.

Illuminated by Esther Faithfull Fleet;

chromolithographed by M. & N. Hanhart London: Emily Faithfull,

Printer & Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty; Victoria Press,

1868. |

|

|

|

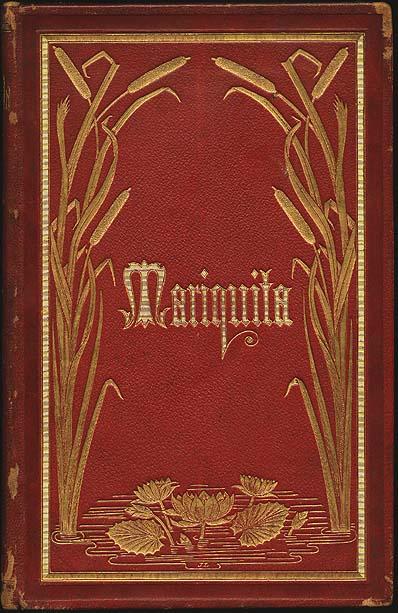

MARIQUITA,

by Henry Grant.

Red morocco with gilt title and water lily design by

John Leighton to front cover, gilt design repeated to rear cover, &

gilt title, ruling & design to spine. One of 123 deluxe morocco

copies printed for the Royal Family and subscribers. Emily Faithfull,

Printer & Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty, 1863. |

The English Woman's Journal

(September, 1861)

WOMEN COMPOSITORS

BY

EMILY FAITHFULL.

(This paper was presented to a meeting of the

National Association for the Promotion of Social Science [NAPSS]

in August, 1861.)

After the meeting in Glasgow, last September, a considerable controversy

arose respecting the facts contained in my Paper relative to the

establishment

of the Victoria Press for the employment of women compositors.

It was once again urged that printing by women was an impossibility: that

the business requires the application of a mechanical mind, and that the

female

mind is not mechanical; that it is a fatiguing, unhealthy trade, and that

women, being physically weaker than men, would sooner sink under this

fatigue and

labour; and to these objections an opinion was added, which it is the

principal object of this Paper to controvert, namely, that the result of

the introduction

of women into the printing trade will be the reduction of the present rate

of wages.

With reference to the observations respecting the arduous nature of

printing, I am quite willing to admit that it is a trade requiring a great

deal of physical

and mental labour. But with regard to the second objection, I can only

say, that either the female mind is mechanical or that printing does not

require a mechanical mind—for that women can print there is no doubt; and I think

everyone will accept as a sufficient proof of this the fact that the

Transactions of

this Association at Glasgow is among the volumes printed by the women

compositors at the Victoria Press. Let this fact speak for itself,

together with

another equally important—namely, that the Victoria Press is already

self-supporting, which is as much as can generally be said of any business

scarcely

eighteen months old, and far more than could have been expected of a

thoroughly new experiment, conducted by one who had only visited a

printing

office on two occasions before the opening of the Victoria Press,

and who had therefore to buy experience at every step; for although such

experience is the most available, it is not the least costly.

The argument that the

wages of men will be reduced by the introduction of women into the

business was also urged against the introduction of machinery, a far more

powerful

invader of man's labour than women's hands, but this has fallen before the

test of experience. It must be remembered, as is well argued by the author

of

the 'Industrial and Social Condition of Women', that the dreaded increase

of competition is of a kind essentially different from the increase of

competition

in the labour market arising from ordinary causes—such increase commonly

arising from an increased population, either by birth or immigration, or a

decrease in the capital available for the labouring population. But in the

case we are contemplating this will not occur, since women already form

part of

the population. Nor will the wages capital be drawn on for the maintenance

of a greater number of individuals than it now supports. The real and only

consequences will be an increase of the productive power of the country,

and a slight re-adjustment of wages; and while heads of families will be

relieved

of some of the burdens that now press on them so heavily, there is no

ground for the fear that the scale of remuneration earned by them will be

really

injured—the percentage withdrawn will be so small that the loss will be proportionably less than the burden from which they will be relieved, for

as the

percentage destined for the support of such dependents is necessarily

distributed to all men indiscriminately, whether their relations in life

require it or not,

it is inadequate to meet the real burden borne by such as have these said

dependents.

It has been asserted that the 'key note to the employment of women is

cheap labour!'—that while the professed cry is to open a new and

remunerative

field for the employment of women, the real object is to lessen the cost

of production.

It is not necessary to give this statement, so far as the printing is

concerned, any further denial than that which is found in the fact that

the wages paid to

the compositors at the Victoria Press are according to the men's

recognised scale. The women work together in companies, with 'a clicker'

to each

companionship, and they write their bills on the same principle and are

paid at the same rate as in men's offices.

At present the Victoria Press is labouring under the disadvantage of

having no women of the standing of journeymen; the compositors have to

serve an

apprenticeship of four years, during which they receive apprentices'

wages, which, though not large, are still good compared to the wages women

receive

in most industrial

employments. These wages differ according to the amount of work done. When

signing the indentures of one of my first apprentices, her father, who is

himself a journeyman printer, suggested to me that instead of fixing a

weekly salary the apprentices should be paid by the piece, two-thirds of

their

earnings, according to the Compositors' Scale (English prices), which is

indeed higher payment than that of boy apprentices, as they seldom receive

two-thirds until the sixth or seventh year of their apprenticeship,

whereas it is paid at the Victoria Press after the first six months,

during which time no

remuneration is given, but a premium of ten pounds required for the

instruction received. I think this system more effective than that of an

established

weekly wage; it is more likely to stimulate exertion, and to make each

apprentice feel that she earns more or less according to her attention and

industry.

It is not correct to suppose that printing simply requires a fair

education, sufficient knowledge of manuscript and punctuation, and that

all else is simple

manipulation.

The difference between a good printer and a bad one is rather in the

quality of mind and the care applied to the work than in the knowledge of

the work

itself. Take the case of two apprentices, employed from the same date,

working at the same frame, and with an equally good knowledge of the

business;

one will earn eighteen shillings a week and the other only ten shillings. The former applies mind to her work, the latter acts as a mere machine,

and

expends as much time in correcting proofs as the other takes in doing the

work well at once. But for every consideration it is necessary that the

work

should be commenced early; neither man nor woman will make much of an

accidental occupation, taken up to fill a few blank years, or resorted to

in the

full maturity of life, without previous use or training, on the pressure

of necessity alone. And those women who become printers, or enter upon any

of the

mechanical trades, must have the determination to make that sacrifice

which alone can ensure the faithful discharge of their work. It is

impossible to

afford help to those who only consent to maintain themselves when youth is

over, and who commence by considering it a matter of injustice and unfair

dealing that the work they cannot do is not offered at once to their

uninstructed hands. I cannot insist too strongly upon this—every day's

experience at the

Victoria Press enforces on my mind the absolute necessity of an early

training, and habits of precision and punctuality—from the want of it I

receive

useless applications from the daughters of officers, clergymen, and

solicitors, gentlewomen who have been tenderly nurtured in the belief that

they will

never have any occasion to work for daily bread, but who from the death of

their father, or some unforeseen calamity, are plunged into utter

destitution, at an age when it is difficult, I had almost said impossible, to acquire new

habits of life, and which leaves them no time to learn a business which

shall support them. Thus, life's heaviest burdens fall on the weakest

shoulders,

and, by man's short-sighted and mistaken kindness, bereavements are

rendered tenfold more disastrous than they would otherwise have been. The

proposal that fathers, who are unable to make some settled provision for

their daughters, should train them as they train their sons, to some

useful

employment, is still received as startling and novel—it runs counter to

a thousand prejudices, yet it bears the stamp of sound common sense, and

it is at

least in accordance with the spirit of Christianity. We have all at some

time or other pitied men who, brought up to no business, are suddenly

deprived of

their fortunes, and obliged to work for their living—we have speculated

on the result of their struggles, and if success has followed their

efforts, we have

pronounced the case exceptional. Is it then a marvel that the general want

of training among women meets us as one of the greatest difficulties in

each

branch of the new employments opening for them? The irreparable mischief

caused by it, and the conviction that it is only the exceptional case in

either

sex which masters the position, determined me on receiving no apprentice

to the printing business after eighteen years of age. Boys begin the

business

very young, and if women are to become compositors it must be under the

same conditions.

Still, in spite of all the difficulties we have encountered, I can report

a steady and most encouraging progress—the Victoria Press can now

execute at least

twice the amount of work it was able to accomplish at the time of the

Association's last Meeting. We have undertaken a weekly newspaper, the

Friend of

the People, and a quarterly, the Law Magazine; we have printed an appeal

case for the House of Lords, and have had a considerable amount of

Chancery

printing, together with sermons and pamphlets from all parts of the

kingdom—and I have recently secured the valuable co-operation of a

partner in Miss

Hays, who has long worked in the movement as one of the Editors of The

English Woman's Journal and as an active member of the Committee of

Management of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. We are

now engaged in bringing out a volume under Her Majesty's sanction as a

specimen of the perfection to which women's printing can be brought. The

initial letters are being designed by Miss Crowe, the Secretary to the

Society

before mentioned, and are being cut by one of the Society's pupils. The

volume will be edited by Miss Adelaide Procter, and will be one of

considerable

literary merit; the leading writers of the day, such as Tennyson,

Kingsley, Thackeray, Anthony and Tom Trollope, Mrs Norton, the Author of

Paul Ferrol, Miss Muloch, Barry

Cornwall, Dean Milman, Coventry Patmore, Mrs Gaskell, Miss Jewsbury,

Monckton Milnes, Owen Meredith, Gerald Massey, Mrs Grote, and, since my

arrival in Dublin, I am grateful to be able to add the name of Lord

Carlisle, and many others, have given us original contributions, and with

kind and cordial

expressions of interest have encouraged us with good wishes for our

permanent success in a work the importance of which it is scarcely

possible to

overestimate.

|

|

Miss EMILY

FAITHFULL contributed a paper "On some of the

Drawbacks connected with the present Employment of Women." She

contended against the prejudice, that women were unfit for industrial

employment, owing to their inaccuracy, and the intermittent nature of

their exertions, on the ground that these faults were not inherent in

women, and that if they passed through the same training as men, they

would show the same capacity for business. Their education was

singularly defective in thoroughness, and habits of accuracy were seldom

acquired. In the middle class this was especially the case.

The daughters of the aristocracy had the means of exercising their

intellects, by a more or less liberal education; the daughters of artisans

and labourers had to earn their bread; but the middle-class girl had no

aim set before her whatever, and learned various desultory things at

school, only to forget them. Her education no more fitted her for

domestic life than for business, and if she proved a good wife and mother,

it was in spite of her training rather than in consequence of it.

She said, a fear has been expressed that if women had anything else to do,

they would be unwilling to marry, and a decrease in the number of

marriages would ensue; but those who entertain such an apprehension must

surely look upon matrimony as a most unhappy state a refuge for the

destitute! If women can only be forced into matrimony as a means of

livelihood, how is it that men are willing to marry--are the advantages

all on their side? The experience of happy wives and mothers forbids

such a supposition. It is likely, on the contrary, that by making

women more capable, the number of marriages will be increased, for there

are many men who would be glad to marry, but who now are deterred from

doing so by prudential considerations. A woman, instead of being

less likely to adorn the married state, would be found more truly a

helpmate to her husband. She who can aid her husband in his business

by looking well to the ways of her household, is an element of wealth as

well as of happiness; and the better trained a woman is, the more

distinctly will she see her duties, and the better will she perform them;

and she will be none the less tender and loving because she has learned to

reflect and judge; and by improving her powers, and giving a practical

turn to her natural capabilities, you would render her far less dependent

upon contingencies, and better able in the hour of need to brave the

battle of life alone.

In conclusion, Miss Faithfull, while urging upon parents the

necessity of doing as much for their girls as for their boys, asked all

who were favourable to this movement to do their utmost to assist in

breaking down the false notions by which a woman is hampered, and to

testify against the principle that indolence is a permissible foible in

women, or that it is feminine and refined; and by so doing to help them to

exchange a condition of labour without profit, and leisure without ease,

for a life of wholesome activity, and the repose which comes with fruitful

toil.

New York Tribune

(4th April, 1873)

Woman's Needs.

Miss Emily Faithfull's Farewell Address in America—No Woman says

No when the Right Man Appears—"Mormonism" the Only Care for

Redundant Femininity.

Steinway Hall was filled yesterday afternoon with an audience

in which ladies largely predominated, gathered to hear the farewell

address of Miss Emily Faithfull. The platform was taken by members

of Sorosis, and by many friends of the movement for the advance of

woman. The Rev. Dr. Bellows opened the exercises by apologizing,

on

behalf of Miss Faithfull, for the omission of the short concert that

had been announced. He spoke briefly of Miss Faithfull's services,

and alluded to the presence on the platform of Lucretia J. Mott. She

thereupon rose, and expressed her unwillingness to take up time

which properly belonged to Miss Faithfull, whose persistent and

noble efforts in a good work deserved the tribute of the presence of

so large a number to express regard and respect. In every effort to

advance woman, and to open abundant avenues for her progress, she

had accomplished much. Mrs. Mott proceeded with reminiscences of the

earlier days of the movement for woman's rights.

Miss Faithfull, on rising, was greeted with an earnest

welcome, and for an hour thereafter claimed the strict attention of

her hearers, whose approval was shown by frequent ripples of

applause.

When she reached America, in October last, she had not

expected to find it so very hard to say farewell in the following

April. From the moment of landing she had been the recipient of the

kindliest hospitality, and now that the time had come to sever the

ties which, manifold and strong, bound her to America and Americans,

she felt too much regret to trust herself to give expression to her

emotions, and gladly recalled the object of meeting. The subject on

which she was to speak had received unmerited abuse, and its

agitators had been charged with trying to set women against men. The

movement truly arises from the deepest sympathy with men, with their

noblest efforts and best aspirations. It is a war of principles, and

in it men and women are deeply interested. There are three great

subjects at present exciting England: first, the Relations of Labor

to Capital; second, Pauperism: third, the Woman Question. The last,

taken in its broadest sense, was to be the theme of the speaker's

utterance on this occasion. She would not appeal to chivalry and

compassion, but to justice and good sense.

In England there are now nearly three million women dependent

on their own exertions. To tell such as these that woman's proper

sphere is home is mockery, for they are forced from their homes to

get bread. Though many a barrier to woman's livelihood had been

broken down, there are still terrible difficulties in finding

employment for women. Specially onerous is the effort in the case of

those of fallen fortunes, members of the genteel class. To relieve

such Miss Faithfull had founded a "Fund for Destitute Gentlewomen,"

to which she would devote the proceeds of the lecture. True it is

that young men now find it hard to get suitable work; they often

have to go west. But there is no analogy among them to the wholesale

yearly destruction of consciences, bodies and souls among

women—destruction too often brought about by destitution. How can

tender-hearted people fold their hands while so many of their

sisters are driven to the gates of hell by want of bread? Statements

are published that capable women, willing to work, can get

employment at good wages. Good, steady, skilled labor is wanted in

just those departments when women have gained position. The

unremitting, earnest application required to acquire skill in these

departments, is hard for women to go through. In them love of work

for its own sake is no more inherent than in men. Moreover, women

are always looking for the appearance of the possible emancipator. Men have nothing but their work to look to for dependence. The

greatest evil of all is the lack of the right early training, and

for this, the family, the parents, society in general, must be

impeached. Society casts a stigma on women who earn their own

livelihood, and parents pray that their daughters may never be

brought so low. As to education, a girl's training stops just where

the main part of a boy's begins. Men are allowed full opportunity to

devote themselves to their chosen work, and are not diverted by

social demands. Women are at the beck and call of everybody, as it

were, and have so many society duties, so many distracting little

trifles to attend to, that the wonder is not that there has not been

a female Shakespeare, Raphael, Newton, but that women have done so

much.

The problem, what we shall do with our redundant women in

England, is answered by some philosophers by proposing emigration

and marriage. But emigration has already been tried, and Scotch,

English, and Irish women have been sent to Australia and America in

large numbers without much diminishing the gravity of the problem;

while as for marriage there is yet to be found the woman to say

"No'' when the right man appears. As long as the number of women in

Great Britain exceeds that of the number of men by six per cent.,

marriage will not wholly do away with the difficulty unless

Mormonism is tried. True marriage is the crown and glory of a

woman's life; but it must be founded on love, and not on the desire

of a home or of support, while nothing can be more deplorable,

debasing, and corrupting than the loveless marriages brought about

in our upper society by a craving ambition and a longing for a good

settlement. Loveless marriages and a different standard of morality

for men and women are the curses of modern society. The dignity of

labor is not yet properly appreciated. We agree that work is

honorable in a man, but are not yet convinced that idleness is

dishonorable in a woman. A contempt for work is at the bottom of the

mind of a fashionable young lady. Frivolity is so general that it is

surprising that so much good survives in spite of neglect. So long as

we frown down and sneer at the efforts to enlarge woman's sphere, we

are encouraging frivolity and idleness in women. We hear the

interests and rights of women spoken of as if these could be

separated from those of man, as if men and women were creatures of a

different kind. A most common and mischievous error is that which

would make woman the mere shadow and attendant of her lord, as if a

shadow could be a true helpmeet. We have long heard the man's

sphere is the world; woman's is home. But women have a part in the

world too, while men are not ciphers in the home circle. The speaker

protested against setting up an ideal standard, and recognizing no

womanliness but such as conformed to that standard. The material

need of opening fresh avenues to woman is obvious; the moral

necessity is also of the utmost importance. Women must have such

occupations as will give them true and genuine sympathies with their

fathers and husbands, who are toiling day by day for their support,

while the women dependent on them are wearing out the hours trying

to kill time. In this way a wide gulf, constantly expanding, is

opened between men and women.

The speaker then inveighed against the undue extravagance of

dress which so demoralizes upper society, who supply the means for

this extravagance and admire the effect. In considering the

admission of women to suffrage, she thought that politics and

electioneering might be purified for their participation. She

recounted a conversation with Horace Greeley, "one," she stated,

"who must be held in respect and veneration by the whole country." In answer to his enquiry as to the reasons English women had for

wishing a part in politics, she said that they had reason to

complain of three great hardships: First, the great educational

endowments left by their ancestors for the use of both sexes are

confined to the benefit of boys. Thus Christ's Hospital in London

yearly educates 1200 boys, and only twenty-six girls. Second, the

property of women is under the husband's control. Third (and hardest

of all), landlords will not have women tenants, because they want

voters. Miss Faithfull proceeded to discuss the arguments for and

against woman suffrage at considerable length, and closed her

address by showing the imperative need of woman's aid in the reform

of prisoners, in the improvement of the criminal classes, in

lessening the evils of factories, where young children are

overworked, and finally and chiefly in the formation of such a

public sentiment as will welcome every effort for the good of man

and woman, and will oppose that worship of mammon which now holds

such universal sway.

The Times

(17 December, 1874)

CHRISTMAS APPEALS

INDUSTRIAL AND EDUCATIONAL BUREAU OF

LADIES.—Miss Emily Faithfull writes with reference to those for whom

this body has been instituted:—"I need not trespass upon your space

with details of the numerous instances personally known to those who

are working in connexion with the Industrial and Educational Bureau

of Ladies brought face to face with cruel privations; furniture

seized because they have not wherewithal to pay the rent of the

rooms they furnished from the wreck of the old home; sickness, and

no means to obtain what the doctor orders; some who are simply

starving for want of work, others who have subsisted on dry bread

for days, with no fire to cheer them, and but little hope of

obtaining employment, from circumstances for which they are far more

to be pitied than blamed, but for which the system under which they

have been reared is really at fault. It is on behalf of such

as these that I entreat the help of the just and charitable, for it

cannot be dispensed with until such sufferers are succeeded by women

who have been taught that all work which is honest is dignified and

noble, and that not only is work honourable in a man, but that

idleness is discreditable even in a woman." Subscriptions may

be sent to Miss Faithfull, 50, Norfolk-square, Hyde-park.

BROOKLYN EAGLE

(15th October, 1882)

MISS FAITHFULL'S VISIT

AND AMERICAN WOMEN.

Miss Emily Faithfull, of England, who has devoted her

energies for nearly a quarter of a century toward the extension of the

remunerative sphere of labor for women, is in this country again, after an

absence of ten years. She comes to reproach us, in common with the

people of England, for our extravagance, and to tell us its cause and give

us a remedy for its cure. Not only extravagance in the expenditure

of money, but in ideas will she rebuke, and the shame of our modern life

she intends to hold up to ridicule. Miss Faithfull will find a wide

field here in which to work, and her theories will be heard by women with

attention. It is likely that her most attentive hearers will be

woman, for the leaven of unrest is at work among them and the transition

state in which they are at present makes them interested listeners to any

voice speaking authoritatively. Miss Faithfull comes from a

government where women's effort to gain a permanent place among the

world's workers has been recognised in a heartier spirit than in this

country, and where the claims of women in regard to property rights have

been successfully made. She come at a favorable time for the sex,

because the outlook is brighter than ever before for the advocates of a

wider field of action for women, and when the latter can point with pride

to some advances of a practical kind made in the past ten years. She

will learn, on the one hand, that while women, for political reasons, have

been turned out of a department in Washington to make way for voters, this

action was met in the right spirit and that it has led to a step on the

part of the woman employees of the Government which could not have been

taken successfully ten years ago in this country. The organization

of the hundreds of workers there and the establishment of a permanent

labor union was the result of this act of injustice. It taught women

the needful lesson of self reliance and the necessity for organization.

Women workers have not united before before because they have not had

strength of numbers or variety of pursuits; but now that an industrial

league has been formed the common interests of women will increase.

Miss Faithfull will find five times the number of women earning a living

in this country now than in 1872, and she will see some happy results from

their efforts to change oppressive laws, to widen the industrial sphere of

the sex and to secure better educational advantages. She will hear

less about woman's rights meetings, note much less buncombe, and she will

see in all directions persistent, and for the most part, successful

workers in paths once deemed unfit for women to walk in. She will

note that the hitherto closed doors are gradually opening to the demand of

women who want work, and she will see that the best cure for modern

extravagance is to give wider opportunities to them. The earning of

money is an inspiring occupation, far more delightful than crochet work or

fashionable indolence, and a woman who once makes her way to a

remunerative employment may be relied upon to be a substantial member of

the community. It is the want of proper occupation that leads women

to be frivolous and extravagant, and it has been a mistaken endeavor on

the part of fathers to try to satisfy their daughters with empty baubles,

rather than to supply them with opportunities that will enable them to

employ their talents and occupy their lives with work that is improving

and elevating. Miss Faithfull may hear, if she will listen

attentively, the undertone of great sadness, and will understand the

weariness of those who are trying to escape from the dreariness of

enforced idleness and mental bondage. If she can give to this class

a cheering word and show them that they can succeed in attaining to places

of usefulness and pecuniary independence, she will have made her visit of

priceless value to American women. The respectability of pauperism

women have always leaned to repudiate, and they are daily proving by their

clamor for employment that, to be a beneficiary of some male relative's

bounty is not the highest ambition of women—the assertion of many false

friends to the contrary notwithstanding.

BROOKLYN EAGLE

(25th April, 1882)

MISS FAITHFULL'S LECTURE

The Outlook for Women in the Nineteenth Century.

Despite the inclement weather on Monday evening a good sized

audience assembled in Plymouth Church to hear Miss Emily Faithfull lecture

on "The Changed Position of Women in the Nineteeth Century." She was

introduced to her audience by the Hon. Stewart L. Woodford, who in a few

well chosen and fitting sentences reminded his listeners that all over the

world Englishmen were keeping St. George's night, and he concluded "We

keep St. George's Night here by welcoming an Englishwoman who with a pen

and not with a sword has rescued her countrywomen from the bondage of

poverty and helped them to useful and profitable employment."

Miss Faithfull's lecture cannot be outlined with justice.

It was a well digested and logical argument for the enfranchisement of

women from morbid sentimentalism, ignorance and fashion and a plea for her

better education, mental, practical and spiritual. She was sensible

and practical, throughout, and delivered her address with an earnestness

that commanded attention and carried conviction. She gave the best,

and perhaps the only detailed resumé

of the industrial and educational progress of the women of England yet

given from the platform in this country. It cheered and inspired her

listeners, and the outbursts of applause that frequently greeted her

showed that speaking from her own heart she had reached the hearts of

others, and appealing for justice and right, she was rewarded with

respectful and appreciative consideration. Perhaps no part of her

lecture interested her hearers more than the brief account she gave of her

own personal experiences with her sex as workers in England. Miss

Faithfull is the editor of the Victoria Magazine, in which office

women were first employed as compositors. The condition of the

helpless women of her country, made so by want of training and the right

views of life, which made them dependent upon relations, she pictured as

deplorable, and read an advertisement which she took from a New York paper

to show that this class of woman is as helpless in this country as in

hers, and is an incubus on society everywhere. Interspersed

throughout her lecture were many witticisms, and she quoted with great

effect some of Mrs. Poyser's and Mrs. Malaprop's logical remarks

concerning women. She contended earnestly for the educational and

political rights of women, and pointed out that the laws of England, the

United States and France were alike unjust to them, and that property

owners among women suffered grievously in consequence. She instanced

Mme. Nilsson's case as proof of the injustice of French law in this

regard. She was compelled to divide her large earnings between

herself and her husband's relative's simply because the law did not

protect her in the possession of her own property. The marriage

ceremony she pronounced a falsehood and a gross outrage in some respects,

in one particular—that relating to worldly goods, which men in sentiment

endow their brides with, but which, in fact, they retain and take all the

wife may have. The lecturer closed with the assertion that she did

not desire to see women go out of their rightful sphere. She wanted

them to fill it in a nobler and better way than they had yet done, and she

concluded by saying that when a woman becomes as great in her womanhood as

a good man is in his manhood, then those twain together would move the

world.

General Woodford, on behalf of the ladies who had been

instrumental in having Miss Faithfull come to Brooklyn to lecture, thanked

the audience for coming out in the storm, and the assemblage dispersed.

The auspices under which Miss Faithfull's lecture was delivered was the

Brooklyn Women's Club, an organization composed mainly of women devoted to

educational and literary pursuits, and numbering among its members many

highly intellectual women. A number of notable and well known people

were in the audience, which represented the best class of our citizens of

our citizens and included very many Plymouth Church members.

THE NORTH AMERICAN REVIEW.

VOL. CLIII.

NEW YORK: 1891.

DOMESTIC SERVICE IN ENGLAND.

BY

MISS EMILY

FAITHFULL.

THE relations existing between servants and their

employers have been much discussed of late: we have been told that an

antagonism is growing up which is “shaking the pillars of domestic peace”;

one writer inveighs against “the semi-feudal relations” and holds a

spirited brief for the maid; another declares that “good old-fashioned

mistresses” have died out, while in certain quarters the problem is

considered “as momentous as that of capital and labor, and as complicated

as that of individualism and socialism."

In one of George Eliot’s novels, the landlord whose customers

appeal to him to settle an argument which has arisen in the bar-parlor

about a village ghost-tale, states his intention of “holding with both

sides, as the truth lies between them.” I confess that his attitude

very much represents my own feeling when I hear of the faults and follies

of servants and the grinding tyranny of the nineteenth-century mistress.

There is an old proverb to the effect that “one story is very well till

the other is told“; and perhaps the whole grievance might be well summed

up in the assertion that imperfect masters and mistresses cannot get

perfect servants, and that servants are no more a failure than any other

class laboring under disadvantages to which I shall more particularly

allude before the end of my observations on this vexed question.

It may be true that domestic relations have not adjusted

themselves at present to the modern spirit of human life, but there is no

clear evidence that the servants of today are really inferior to those who

waited on our ancestors in olden times; and in spite of the oft-repeated

tale that there are “no servants to be had,” I have never yet met anyone

who ever sought one in vain. Although the class of people who never

dreamt of having servants a hundred years ago require them now, still the

supply is equal to the demand; and this, too, in spite of the system of

emigration which takes hundreds of young English and Irish women to the

colonies and America.

It is not within the purpose of this article to touch upon

the difficulties which surround domestic service in the United States; but

I may, perhaps, be allowed to remark that I was much struck, while

travelling there, with the independent bearing of “the help,” especially

in the far West, and also with the vast amount of work done in large

houses by one or two women—mostly Irish—with only the assistance of the

man who comes once a day to do “the chores.” Similar establishments

to these in England would demand from four to six servants; but it must be

admitted that social habits are more simple in America and labor-saving

machines are far more abundant: lifts connect the kitchen with the

dining-room in even ordinary houses, and the hot and cold-water pipes

which are connected with the washstands in the bedrooms considerably

diminish the housemaids’ duties, especially as there is an outlet for the

water used as well.

In America “the hired girl” is apt to leave at a moment’s

notice if anything displeases her, but an English servant seldom packs up

her boxes and places her mistress in this inconvenient position: she gives

a month’s notice if she finds her place does not suit her, and as she

looks to her mistress for a character, she is generally anxious to make a

good impression before leaving. On the other hand, a lady has no

right to discharge a servant without due warning; she is only justified in

dismissing a servant “at a moment’s notice” on the grounds of wilful

disobedience to lawful orders, drunkenness, theft, habitual negligence or

moral misconduct, abusive language, and incompetence or permanent

incapacity from illness. In Scotland a six-months’ engagement

generally prevails—a system which is far less satisfactory to both the

contracting parties if a mistake has been made by either of them.

No lady is legally bound to give a domestic servant a

character, but it is an unwritten law that a mistress should fairly state

all she knows in favor of the girl who is leaving her service: such

communications are regarded as “privileged,” but any evidence of malice

would render the person guilty of it liable to an action at the suit of

the servant, and “a false character” “knowingly given” can be punished by

a penalty of £20 if the servant in whose interest it has been made robs

the mistress who in consequence of such a misrepresentation takes her into

her employment.

The “I’m-as-good-as-you” sort of spirit is by no means the

characteristic of the well-trained English servant: her own self-respect

teaches her to accord the deference due to those she serves, and she takes

a pride in the dainty cap and spotless white apron which are regarded in

America as “badges of slavery,” for they distinguish her from the type of

servants employed in inferior houses where such adornments are unknown and

are regarded by mistresses as useless ‘‘luxuries.“

There is a wide gulf between the ordinary “slavey” and the

well-disciplined servant, both as regards personality and treatment.

The general servant may perhaps have a “good time” of it in the

tradesman’s household where she is literally treated as one of the family,

and fancies her equality established by the fact that she addresses all

the children by their Christian names, takes her place with the family at

meals, and spends her Sunday “in” at ease in the one sitting-room in the

establishment, in familiar intercourse with her employers. But the

lodging-house “slavey” has no rest for the sole of her foot from one

week’s end to the other. Her mistress, a woman of the same class

probably, often treats her with a want of consideration that no lady could

possibly show: it is true that the woman works very hard herself, cooking

the meals of the lodgers, who breakfast and dine at different hours, but

she is, of course, fortified by the gains she is making; the poor drudge,

however, is toiling from morning to night for a mere pittance of perhaps

£10 to £12 a year, learning nothing that will ever fit her for a better

situation, and with hard words, instead of thanks, for all her efforts to

please every one.

I shall never forget the impression made on my own mind by an

incident which occurred to me when I had rooms in a lodging-house in one

of the most fashionable parts of London, while the house I had bought was

being decorated for me. I went to my bedroom after being at the

first performance of a play at the Lyceum, at which Mr. Irving had been

required to make a speech, and, coming home very late and tired, hastily

retired to rest by the dim light of a melancholy candle. While

undressing I was startled by a sound which warned me that someone was in

my room: on looking round I saw what at first seemed to me a bundle of

clothes hanging over a chair; it turned out to be the poor “slavey,” who,

worn out with the day’s fatigues, while putting the finishing touches to

my bedroom had sat down and fallen sound asleep in the armchair.

She must have been there for at least two hours! Up at six o’clock

in the morning, seldom able to go to bed in her miserable attic till after

midnight, and only half-fed, this unfortunate girl may be regarded as a

type of a class of servants in England who are really much to be pitied.

A girl whose “first place” is in a lodging-house, or who, as

the hard-worked, underfed scrub in a small tradesman’s large family, in

which the care of the perpetual baby falls to her lot, as well as

housework of all kinds, has no sinecure; she seldom finds anyone who tries

to give her an idea of the intelligent, methodical way in which she should

set about her duties, and is consequently disgusted with the vocation,

anxious to abandon it for the freedom of the factory, and ready to advise

all her companions to do the same. The miserable little drudge has

been treated by the petty tyrants into whose hands she unfortunately fell

as one who was to be used as their abject slave, without the least regard

to her feelings or inclinations; she has been made to rise early and go to

bed late; her food has been the leavings of the master’s table; her work

dirty and disagreeable; often she has been watched as if her honesty was

suspected, and her liberty has been so curtailed that what should have

been her home has been converted into a prison. How can we wonder

that servant girls under these conditions are “slatternly, slothful, and

impudent,” or that such an experience should make them inclined to seek

some other means of livelihood?

Good general servants are much sought after by families

living in substantial houses and in a fairly comfortable fashion.

They command wages varying from £16 to £22 a year, and resemble “the crew

of the captain’s gig” in Mr. Gilbert’s famous “Bab Ballad,” inasmuch as

they have to be cook, parlor-maid, and house-maid all in one. Some

servants like these places, for, though they have more work to do, they

have far more freedom than it is possible to allow in large

establishments; “the general” has no kitchen warfare, at any rate, and

only her mistress to please; she has no upper servant to obey, and no

“tempers” or moments of jealousy to ruffle her serenity, and she often

ends in taking a genuine pride in the house and a keen interest in the

family, sharing their triumphs and sorrows after her own honest, hearty

fashion.

The servants employed by the wealthy middle families and “the

upper ten thousand” are not badly paid, and they are certainly not badly

treated. When domestic service in England is compared with the

position of needlewomen, compositors, and telegraph and telephone

operators, the showing is certainly in favor of the former in comfort; the

parlor-maid is better lodged, better fed, and, although she may receive

only £20 a year, it is really equivalent to £70: the money value of her

improved position would far more than treble her wages if it were paid in

coin. A competent “table-maid” now asks from £18 to £30 a year; a

well-trained housemaid, from £16 to £25; cooks, from £20 to £60; footmen

earn from £25 to £40, with suits of livery; butlers, from £50 to £80; in

some houses where the butler has great responsibility, and no

house-steward is kept, he receives more than £100 a year. The

skilled man chef, of course, earns his hundreds, while the modest kitchen

maid welcomes from £10 to £18. The wages of housekeepers vary from

£30 to £50 in private families; the head nurse and the lady’s maid receive

from £20 to £35; and in certain quarters still higher salaries are given.

Mrs. Crawshay’s scheme for “lady helps” has not been at all generally

adopted. I have always advocated the employment of a lady in the

nursery: the advantage to the children in health, manners, and morals

would be of immense gain to any household rich enough to afford it, and by

such means we might help to stamp out the foolish notion that there is any

social degradation in domestic service.

One of the trials of the English housekeeper who has a large

retinue under her command is the servant who is always on the defensive

respecting her individual rights and place. “I keep to my bargain;

let other people keep to theirs,” is her obstinate cry, and she refuses to

lend a hand outside her “own work,” no matter who may suffer. The

most obliging and civil servants I have ever met with are those employed

by royalty and in aristocratic houses. While the “little

middle-class snob“ treats her servants with curtness, the well-bred woman

of rank accepts their services with courtesy and grace; although she knows

she has a perfect right to command them, noblesse oblige, and she

has the self-respect which naturally accords the respect due to

dependents.

The late outcry against servants strikes me as somewhat

unfair and uncalled for. The prize given by Messrs. Cassell in

connection with The Quiver, about three years ago, proved that the

1,500 servants who competed for it had lived from ten to upwards of twenty

years in the same family. My own sister has a nurse who has been in

her household for forty years—ever since her eldest son was born; another

friend has had the same housemaid for more than twenty-five years and a

coachman for fifteen; and many others tell me of servants who have lived

with them for periods extending from twelve to twenty years. While

we sigh for the good old-fashioned servants who gave their employers “the

heart service alone worth having,” we are apt to forget the changes which

have taken place in social life, the results of which are stamped as

deeply on the servants as on ourselves. If restless ambition and

discontent prevail in the kitchen, we must not overlook the fact that they

first invaded the drawing-room. Nor can we be blind to the influence

exercised by the widespread love of change and dress, and our servants are

keen enough to see when employers live beyond their means and “make a

show,” for this generally brings about the petty screwings which press

hardest on the household. But it may well be asked, “Who are the

tyrants —the mistresses who desire to have reasonable rules carried out in

their own houses, or the servants who want their own way in everything,

and try to rule their mistresses in the bargain?“

The relation between mistress and maid would be undoubtedly

improved if the former had a more practical knowledge of household duties.

Many of “our daughters” marry young and in utter ignorance of the

management of a house: if middle-class girls knew something about domestic

economy, the pockets of struggling husbands would be spared and many a

domestic breeze avoided. I am now alluding to the mistresses who

“run their own households”: the aristocracy know but little of their

servants—save their personal attendants—and complain still less.

The monotony and restrictions which surround the life of the

ordinary servant have given rise to most of the objections which have been

raised against the occupation. “To clean herself” after a hard day’s

work and sit down to needlework, or to the more exciting recreation

afforded by The Family Herald, is scarcely exhilarating enough for

the modern servant, and the joy of the alternate “Sunday out” and the

occasional holiday is spoilt by the hour fixed for the enforced return.

The parlor-maid hears her young ladies talking at the dinner table of the

delightful play they have seen the night before, and she is naturally

inspired with a wish to see it herself; but this is impossible if the door

is to be barred at 10 o’clock, especially as she has to find her way home

in an omnibus, for which she probably had to wait half an hour when the

play is over. The truth is that mistresses, as a rule, have not yet

accepted a condition to which men in command of others have long since

bowed—that pleasure and personal liberty in moderation must be accorded

when the day’s work is done. Servants are mostly young women in the

prime of life, with all the instincts of youth full upon them, and it is

cruel to ignore their social needs. Their followers and visitors are

not welcome to those in authority, and therefore less objection should be

raised to their occasional efforts to obtain the companionship of their

own class outside the house when their work is done.

I fear we must own to another fault in dealing with our

servants: women scold and nag in a way which is unknown to men who are

really fit to rule. They listen to the gossip of other servants, and

almost lie in wait for the suspected delinquent. A wise master knows

the value of sometimes shutting his eyes, and will certainly let a good

employee have time to recover himself before he attempts any

expostulation. The ordinary mistress unfortunately summons the

servant before she has controlled her own temper, and the result is

disastrous to both. If once “a hostile attitude” describes the

relation between the drawing-room and the kitchen, a state of constant

friction must ensue.

I do not ignore the trials experienced by the mistresses of

untrained servants: too often a succession of wasteful, ignorant girls

pass, like phantasmagoria, across the threshold, leaving, however, a very

convincing proof of their reality in the wreck of kitchen utensils, china,

and other household treasures. Where large establishments are kept,

young servants are carefully taught their separate duties; but it is a

deplorable fact that girls who have passed the fifth board-school standard

are often incapable of lighting a fire, or of washing a wine-glass without

breaking it. They can read the “penny dreadful,” but they cannot

darn their stockings or mend their clothes. The want of technical

training is the disadvantage which has threatened to make servants a

failure; but our board schools are now waking up to their

responsibilities; they have begun to include needlework and cooking in

their list of subjects, and I hope they will shortly add laundry and house

work.

Mrs. Darwin appears to think that the mistress who demands a

formal character of the servant should be willing to furnish one

respecting herself. She writes in The Nineteenth Century—

“Every mistress should choose a referee, or two referees,

among her servants past or present, who have been with her not less than

two years; she should give the names and addresses of these two referees

to the servant whom she is inclined to engage before she writes for her

character from her last mistress. . . . I cannot imagine any reasonable

objection to this plan. If carried largely into practice, it could

become the test of any theory about domestic service. Mistresses

could then gather statistics and make generalizations as to the situations

which were most highly recommended and most sought after by the best and

most competent of servants. It might also put spirit into the custom

of character-giving, which is said by some to be so formal.

Personally, I have never found it so. It puts a vast amount of

irresponsible power into the hands of one fallible human being; and though

I think it may rarely be abused, it adds tremendously to the unnecessary

and injurious dependence of servants.”

This novel idea has partially been indorsed by the Hon. Maud Stanley,

whose work and experience certainly entitle her to speak with authority.

I confess I cannot think the plan likely to promote the cordial relations

we are all anxious to secure; nor do I follow Mrs. Darwin in her argument

that domestic service has necessarily a deteriorating effect on the

character. The very nature of it makes it depend upon the individual

character on both sides, and no arbitrary external rules will ever bring

about a satisfactory improvement.

On the whole, I do not believe that there ever was a time

when servants in England were better treated and better fed and allowed

more liberty than at present: they might, perhaps, be better lodged, for

English architects seem to have thought but little of the rooms servants

would have to work and sleep in, and the condition of some of our

handsomest city houses is not without reproach in this direction.

Perhaps some day this may be remedied, when women’s attention is turned to

the interior arrangements of our houses. Miss Charlotte Robinson

(home Art Decorator to Her Majesty) is already helping us to make our

homes beautiful, and the aid of feminine domestic mechanical engineers who

will help us to overcome the difficulties by which domestic machinery is

still surrounded, and the feminine architect who will not sacrifice

everything to the drawing-room and dining-room, will be most acceptable to

all who wish to secure the health and comfort of the entire household.

Some servants at present live below the ground and sleep under the slates,

or have to be content with a turn-up bedstead among the black beetles and

cockroaches which disport themselves in the pantry.

There is, however, but little wanton neglect of servants

nowadays, nor do I think servants are less industrious or more incompetent

than in the days of our “forebears.” The infirmities of humanity and

the spirit of the age are not likely to be confined to one section of

society: all classes have been more or less seized by this restless

craving for change and not unnatural wish to “better themselves.”

Good mistresses, as a rule, still manage to get good servants, who are not

in a hurry to leave them; the English servant may consider herself well

off compared to other wage-earning women, and, provided she does not

squander her wages on dress; she is able, while living in comfort, to save

sufficient money to provide either for marriage or old age.

EMILY FAITHFULL.

|