|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER VII.

PHILANTROPISTS.

_______

ONE conviction forms the basis of all correct

admiration for the heroism and intrepidity of scientific discoverers, the

marvellous inventions of mechanicians; the sublime enthusiasm of poets,

artists, and musicians; the laborious devotion of scholars; and even of

the intelligent industry of the accumulators of wealth: it is that all

their efforts and achievements tend, by the law of our nature, to the

amelioration of man's condition. In every mind swayed by reflection,

and not by impulse or prejudice, the world's admiration for warriors is

regarded as mistaken, because the deeds of the soldier are the infliction

of suffering and destruction, spring from the most evil passions, and

serve but to keep up the real hindrances of civilization and human

happiness. Statues and columns erected in honour of conquerors,

excellent as they may be for the display of art, serve, therefore, in

every correct mind, for subjects of regretful rather than encouraging and

satisfactory contemplation. The self-sacrificing enterprises of the

philanthropist, on the contrary, create in every properly regulated mind,

still purer admiration, still more profound and enduring esteem, than even

the noblest and grandest efforts of the children of Mind and Imagination.

The DIVINE EXEMPLAR himself is

at the head of their class; and they seem, of all the sons of men, most

transcendently to reflect his image, because their deeds are direct acts

of mercy and goodness, and misery and suffering flee at their approach.

Harbingers of the benign reign of Human Brotherhood which the popular

spirit of our age devoutly regards as the eventual destiny of the world,

they will be venerated, and their memories cherished and loved, when

laurelled conquerors are mentioned no more with praise, or are forgotten.

Emulation is sometimes termed a motive of questionable morality; but to

emulate the high and holy enterprises of self-sacrificing beneficence can

never be an unworthy passion; for half the value of a good man's life

would be lost, if his example did not serve to fill others with such a

plenitude of love for his goodness, as to impel them to imitate him.

It is the example of the philanthropist, then, that we commend, above all

other examples, to the imitation of all who are beginning life. We

would say, scorn indolence, ignorance, and reckless imprudence that makes

you dependent on others' effort instead of your own; but, more than all,

scorn selfishness and a life useless to man, your brother, cleave to

knowledge, industry, and refinement; but, beyond all, cleave to goodness.

In a world where so much is wrong—where, for ages, the

cupidity of some, and the ignorance and improvidence of a greater

number—has increased the power of wrong, it need not be said how

dauntless must be the soul of perseverance needed to overcome this wrong

by the sole and only effectual efforts of gentleness and goodness.

That wisdom—deeply calculating wisdom—not impulsive and indiscriminate

"charity," as it is falsely named—should also lend its calm but energetic

guidance to him who aims to assist in removing the miseries of the world,

must be equally evident. To understand to what morally resplendent

deeds this dauntless spirit can conduct, when thus guided by wisdom, and

armed with the sole power of gentleness, we need to fix our observance but

on one name—the most worshipful soldier of humanity our honoured land has

ever produced: the true champion of persevering goodness.

JOHN HOWARD

|

|

|

John Howard, FRS

(1726-90) |

Inheriting a

handsome competence from his father, whom he lost while young, went abroad

early, and in Italy acquired a taste for art. He made purchases of

such specimens of the great masters as his means would allow, and

embellished therewith his paternal seat of Cardington, in Bedfordshire.

His first wife, who had attended him with the utmost kindness during a

severe illness, and whom, though much older than himself, he had married

from a principle of gratitude, died within three years of their union; and

to relieve his mind from the melancholy occasioned by her death, he

resolved on leaving England for another tour. The then recent

earthquake which had laid Lisbon in ruins, rendered Portugal a clime of

interest with him, and he set sail for that country. The packet,

however, was captured by a French privateer; and he and other prisoners

were carried into Brest, and placed in the castle. They had been

kept forty hours without food or water before entering the filthy dungeon

into which they were cast, and it was still a considerable time before a

joint of mutton was thrown into the midst of them, which, for want of the

accommodation even of a solitary knife, they were obliged to tear to

pieces and gnaw like dogs. For nearly a week Howard and his

companions were compelled to lie on the floor of this dungeon, with

nothing but straw to shelter them from its noxious and unwholesome damps.

He was then removed to another town where British prisoners were kept; and

though permitted to reside in the town on his "parole," or word of honour,

he had evidence, he says, that many hundreds of his countrymen perished in

their imprisonment, and that, at one place, thirty six were buried in a

hole in one day. He was at length permitted to return home, but it

was upon his promise to go back to France, if his own government should

refuse to exchange him for a French naval officer. As he was only a

private individual, it was doubtful whether government would consent to

this; and he desired his friends to forbear the congratulations with which

they welcomed his return, assuring them he should perform his promise, if

government expressed a refusal. Happily the negotiation terminated

favourably, and Howard felt himself, once more, at complete freedom in his

native land.

It is to this event, comprising much personal suffering for

himself, and the grievous spectacle of so much distress endured by his

sick and dying fellow-countrymen in bonds, that the first great emotion in

the mind of this exalted philanthropist must be dated. Yet, like

many deep thoughts which have resulted in noble actions, Howard's grand

life-thought lay a long time in the germ within the recesses of his

reflective faculty. He first returned to his Cardington estate, and,

together with his delight in the treasures of art, occupied his mind with

meteorological observations, which he followed up with such assiduity as

to draw upon himself some notice from men of science, and to be chosen a

Fellow of the Royal Society.

After his second marriage, he continued to reside upon his

estate, and to improve and beautify it. The grounds were, indeed,

laid out with a degree of taste only equalled on the estates of the

nobility. But it was impossible for such a nature as Howard's to be

occupied solely with a consideration of his pleasures and comforts.

His tenantry were the constant objects of his care, and in the improvement

of their habitations and modes of life he found delightful employment for

by far the greater portion of his time. In his beneficent plans for

the amelioration of the condition of the poor he was nobly assisted by the

second Mrs. Howard, who was a woman of exemplary and self-sacrificing

benevolence. One act alone affords delightful proof of this.

She sold her jewels soon after her marriage, and put the money into a

purse called, by herself and her husband, "the charity-purse," from the

consecration of its contents to the relief of the poor and destitute.

The death of this excellent woman plunged him again into

sorrow, from which he, at first, sought relief in watching over the

nurture of the infant son she had left him, having breathed her last soon

after giving birth to the child. When his son was old enough to be

transferred entirely to the care of a tutor, Howard renewed his visits to

the Continent. His journal contains proof that his mind was deeply

engaged in reflection on all he saw; but neither yet does the

master-thought of his life appear to have strengthened to such a degree as

to make itself very evident in the workings of his heart and

understanding. His election to the office of high sheriff of the

county of Bedford, on his return, seems to have been the leading

occurrence in his life, judging by the influence it threw on the tone of

his thinkings and the character of his acts, to the end of his mortal

career. He was forty-six years of age at the time of his election to

this office, intellectual culture had refined his character, and much

personal trial and affliction had deepened his experience: the devotion of

such a man as John Howard to his great errand of philanthropy was not,

therefore, any vulgar and merely impulsive enthusiasm. We have seen

that the germ of his design had lain for years in his mind, scarcely

fructifying or unfolding itself, except in the kindly form of homely

charity. The power was now about to be breathed upon it which should

quicken it into the mightiest energy of human goodness.

He thus records the grievances he now began to grow ardent

for removing: "The distress of prisoners, of which there are few who have

not some imperfect idea, came more immediately under my notice when I was

sheriff of the county of Bedford; and the circumstance which excited me to

activity in their behalf was, the seeing some, who by the verdict of

juries were declared not guilty—some, on whom the grand jury did

not find such an appearance of guilt as subjected them to trial—and some

whose prosecutors did not appear against them—after having been confined

for months, dragged back to gaol, and locked up again till they could pay

sundry fees to the gaoler, the clerk of assize, &c. In order

to redress this hardship, I applied to the justices of the county for a

salary to the gaoler in lieu of his fees. The bench were properly

affected with the grievance, and willing to grant the relief desired; but

they wanted a precedent for charging the county with the expense. I

therefore rode into several neighbouring counties in search of a

precedent; but I soon learned that the same injustice was practised in

them; and looking into the prisons, I beheld scenes of calamity which I

grew daily more and more anxious to alleviate." How free from

violence of emotion and exaggerated expression is his statement; how

calmly, rationally, and thoughtfully he commenced his glorious enterprise!

He commences, soon after this, a series of journeys for the

inspection of English prisons; and visits, successively, the gaols of

Cambridge, Huntingdon, Northampton, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby,

Stafford, Warwick, Worcester, Gloucester, Oxford, and Buckingham. In

many of the gaols he found neither court-yard, water, beds, nor even

straw, for the use of the prisoners: no sewers, most miserable provisions,

and those extremely scanty, and the whole of the rooms gloomy, filthy, and

loathsome. The greatest oppressions and cruelties were practised on

the wretched inmates: they were heavily ironed for trivial offences, and

frequently confined in dungeons under ground. The Leicester gaol presented

more inhuman features than any other; the free ward for debtors who could

not afford to pay for better accommodation, was a long dungeon called a

cellar, down seven steps—damp, and having but two windows in it, the

largest about a foot square; the rooms in which the felons were confined

night and day were also dungeons from five to seven steps under ground.

In the course of another tour he visited the gaols of

Hertford, Berkshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, Hampshire, and Sussex; set

out again to revisit the prisons of the Midlands; spent a fortnight in

viewing the gaols of London and Surrey; and then went once more on the

same great errand of mercy into the west of England. Shortly after

his return he was examined before a Committee of the whole House of

Commons, gave full and satisfactory answers to the questions proposed to

him, and was then called before the bar of the House to receive from the

Speaker the assurance, "that the House were very sensible of the humanity

and zeal which had led him to visit the several gaols of this kingdom, and

to communicate to the House the interesting observations he had made upon

that subject."

The intention of the Legislature to proceed to the correction

of prison abuses, which the noble philanthropist might infer from this

expression of thanks, did not cause him to relax in the pursuit of the

high mission he was now so earnestly entered upon. After examining

thoroughly the shameless abuses of the Marshalsea, in London, he proceeded

to Durham, from thence through Northumberland, Cumberland, Westmoreland,

and Lancashire, and inspected not only the prisons in those counties, but

a third time went through the degraded gaols of the Midlands. A

week's rest at Cardington, and away he departs to visit the prisons in

Kent, and to examine all he had not yet entered in London. North and

South Wales and the gaols of Chester, and again Worcester and Oxford, he

next surveys, and discovers another series of subjects for the exertion of

his benevolence.

"Seeing," says he, in his uniform and characteristic vein of

modesty, "in two or three of the county gaols some poor creatures whose

aspect was singularly deplorable, and asking the cause of it, I was

answered they were lately brought from the Bridewells. This

started a fresh subject of inquiry. I resolved to inspect the

Bridewells; and for that purpose I travelled again into the counties where

I had been, and, indeed, into all the rest, examining houses of correction

and city and town gaols. I beheld in many of them, as well as in

county gaols, a complication of distress; but my attention was

particularly fixed by the gaol-fever and small-pox which I saw prevailing

to the destruction of multitudes, not only of felons in their dungeons,

but of debtors also." His holy mission now comprehended for the

philanthropist the enterprise of lessening the disease as well as unjust

and inhuman treatment of prisoners.

The most striking scene of wrong detailed in any of his

narratives is in the account of the "Clink" prison of Plymouth, a part of

the town gaol. This place was seventeen feet by eight, and five feet

and a half high. It was utterly dark, and had no air except what

could be derived through an extremely small wicket in the door. To

this wicket, the dimensions of which were about seven inches by five,

three prisoners under sentence of transportation came by turns to breathe,

being confined in that wretched hole for nearly two months. When

Howard visited this place the door had not been opened for five weeks.

With considerable difficulty he entered, and with deeply wounded feelings

beheld an emaciated human being, the victim of barbarity, who had been

confined there ten weeks. This unfortunate creature, who was under

sentence of transportation, declared to the humane visitor who thus risked

his health, and was happy to forego ease and comfort, to relieve the

oppressed sufferer, that he would rather have been hanged than thrust into

that loathsome dungeon.

The electors of Bedford, two years after Howard had held the

shrievalty of their county, urged him to become a candidate for the

representation of their borough in Parliament. He gave a reluctant

consent, but through unfair dealing was unsuccessful. We may, for a

moment, regret that the great philanthropist was not permitted to

introduce into the Legislature of England measures for the relief of the

oppressed suggested by his own large sympathies and experience; but it was

far better that he was freed from the shackles of attendance on debates,

and spared for ministration not only to the sufferings of the injured in

England but in Europe.

He had long purposed to give to the world in a printed form

the result of his laborious investigations into the state of prisons in

this country; but "conjecturing," he says, "that something useful to his

purpose might be collected abroad, he laid aside his papers and travelled

into France, Flanders, Holland, and Germany." We have omitted to

state that he had already visited many of the prisons in Scotland and

Ireland. At Paris he gained admission to some of the prisons with

extreme difficulty; but to get access to the state prisons the jealousy of

the governments rendered it almost impossible, and under any circumstances

dangerous. The intrepid heart of Howard, however, was girt up to

adventure, and he even dared to attempt an entrance into the infamous

Bastile itself! "I knocked hard," he says, "at the outer gate, and

immediately went forward through the guard to the drawbridge before the

entrance of the castle; but while I was contemplating this gloomy mansion,

an officer came out of the castle much surprised, and I was forced to

retreat through the mute guard, and thus regained that freedom, which, for

one locked up within those walls, it would be next to impossible to

obtain." In the space of four centuries, from the foundation to the

destruction of the Bastile, it has been observed that Howard was the only

person ever compelled to quit it with reluctance.

By taking advantage of same regulations of the Paris

Parliament, he succeeded in gaining admission to other prisons, and found

even greater atrocities committed there than in the very worst gaols in

England. Flanders presented a striking contrast. "However

rigorous they may be," says he, speaking of the regulations for the

prisons of Brussels, "yet their great care and attention to their prisons

is worthy of commendation: all fresh and clean, no gaol distemper, no

prisoners ironed. The bread allowance far exceeds that of any of our

gaols; every prisoner here has two pounds of bread per day, soup once

every day, and on Sunday one pound of meat." He notes afterwards

that he "carefully visited some Prussian, Austrian, and Hessian gaols,"

and "with the utmost difficulty" gained access to "many dismal abodes" of

prisoners.

Returning to England, he travelled through every county

repursuing his mission, and after devoting three months to a renewed

inspection of the London prisons, again set out for the Continent.

Our space will not allow of a record of the numerous evils he chronicles

in these renewed visits. The prisoners of Switzerland, but more than

all, of Holland, afforded him a relief to the vision of horrors he

witnessed elsewhere. We must find room for some judicious

observations he makes on his return from this tour. "When I formerly

made the tour of Europe," are his words, "I seldom had occasion to envy

foreigners anything I saw with respect to their situation, their

religion, manners, or government. In my late

journeys to view their prisons I was sometimes put to the blush for my

native country. The reader will scarcely feel, from my narration,

the same emotions of shame and regret as the comparison excited in me on

beholding the difference with my own eyes; but from the account I have

given him of foreign prisons, he may judge whether a design for reforming

their own be merely visionary—whether idleness, debauchery, disease,

and famine, be the necessary attendants of a prison, or only

connected with it in our ideas for want of a more perfect knowledge and

more enlarged views. I hope, too, that he will do me the justice to

think that neither an indiscriminate admiration of everything foreign, nor

a fondness for censuring everything at home, has influenced me to adopt

the language of a panegyrist in this part of my work, or that of a

complainant in the rest. Where I have commended I have mentioned my

reasons for so doing; and I have dwelt, perhaps, more minutely upon the

management of foreign prisons because it was more agreeable to praise than

to condemn. Another motive induced me to be very particular in my

accounts of foreign houses of correction, especially those of the

freest states. It was to counteract a notion prevailing among us,

that compelling prisoners to work, especially in public, was inconsistent

with the principles of English liberty; at the same time, that taking away

the lives of such numbers, either by executions or the diseases of our

prisons, seems to make little impression upon us; of such force are custom

and prejudice in silencing the voice of good sense and humanity. I

have only to add that, fully sensible of the imperfections which must

attend the cursory survey of a traveller; it was my study to remedy that

defect by a constant attention to the one object of my pursuit alone

during the whole of my two last journeys abroad."

He did not allow himself a single day's rest on returning to

England, but immediately recommenced his work here. He notes some

pleasing improvements, particularly in the Nottingham gaol, since his last

preceding visit; but narrates other discoveries of a most revolting

description. The gaol at Knaresborough was in the ruined castle, and

had but two rooms, without a window. The keeper lived at a distance,

there being no accommodation for him in the prison. The debtors'

gaol was horrible; it consisted of only one room, difficult of access, had

an earthen floor, no fireplace, and there was a common sewer from the town

running through it uncovered! In this miserable and disgusting hole

Howard learned that an officer had been confined some years before, who

took with him his dog to defend him from vermin: his face was, however,

much disfigured by their attacks, and the dog was actually destroyed by

them.

At length he prepared to print his "State of the Prisons of

England and Wales, with Preliminary Observations, and an Account of some

Foreign Prisons." In this laborious and valuable work, he was

largely assisted by the excellent Dr. Aikin, a highly congenial mind; and

it was completed in a form which, even in a literary point of view, makes

it valuable. The following very brief extract from it, is full of

golden reflection: "Most gentlemen who, when they are told of the misery

which our prisoners suffer, content themselves with saying, 'Let them

take care to keep out,' prefaced, perhaps, with an angry prayer, seem

not duly sensible of the favour of Providence, which distinguishes them

from the sufferers: they do not remember that we are required to imitate

our gracious Heavenly Parent, who is 'kind to the unthankful and the

evil!' They also forget the vicissitudes of human affairs: the

unexpected changes, to which all men are liable; and that those whose

circumstances are affluent, may, in time, be reduced to indigence, and

become debtors and prisoners."

As soon as his book was published, he presented copies of it

to most of the principal persons in the kingdom,—thus devoting his

wealth, in another form, to the cause of humanity. When it is

recounted that he had not only spent large sums in almost incessant

travelling, during four years, but had paid the prison fees of numbers who

could not otherwise have been liberated; although their periods of

sentence had transpired, some idea may be formed of the heart that was

within this great devotee of mercy and goodness—the purest of all

worships.

The spirits of all reflecting men were roused by this book:

the Parliament passed an Act for the better regulation of the "bulk"

prisons; and on Howard's visiting the hulks and detecting the evasions

practised by the superintendents, the government proceeded to rectify the

abuses. Learning that government projected further prison reforms,

he again set out for the Continent, to gain additional information in

order to lay it before the British Parliament. An accident at the

Hague confined him to his room for six weeks, by throwing him into an

inflammatory fever; but he was no sooner recovered than he proceeded to

enter on his work anew, by visiting the prison at Rotterdam,—departing

thence through Osnaburgh and Hanover, into Germany, Prussia, Bohemia,

Austria, Italy, Switzerland, and back through France, again reaching

England. Not to enumerate any of his statements respecting his

prison visits, let us point the young reader to the answer he gave to

Prince Henry of Prussia, who, in the course of his first conversation with

the earnest philanthropist, asked him whether he ever went to any public

place in the evening, after the labours of the day were over.

"Never," he replied, "as I derive more pleasure from doing my duty than

from any amusement whatever." What a thorough putting-on of the

great martyr spirit there was in the life of this pure-souled man!

Listen, too, to the evidence of his careful employment of the

faculty of reason, while thus enthusiastically devoted to the tenderest

offices of humanity: "I have frequently been asked what precautions I used

to preserve myself from infection in the prisons and hospitals which I

visit. I here answer once for all, that next to the free goodness

and mercy of the Author of my being, temperance and cleanliness are my

preservatives. Trusting in Divine Providence, and being myself in

the way of my duty, I visit the most noxious cells, and while thus

employed 'I fear no evil!' I never enter an hospital or prison

before breakfast, and in an offensive room I seldom draw my breath

deeply."

Mark his intrepid championship of Truth, too, as well as of

Mercy. He was dining at Vienna with the English ambassador to the

Austrian court, and one of the ambassador's party, a German, had been

uttering some praises of the Emperor's abolition of torture. Howard

declared it was only to establish a worse torture, and instanced an

Austrian prison which, he said, was "as bad as the blackhole at Calcutta,"

and that prisoners were only taken from it when they confessed what was

laid to their charge. "Hush!" said the English ambassador (Sir

Robert Murray Keith), "your words will be reported to his Majesty!"

"What!" exclaimed Howard, "shall my tongue be tied from speaking truth by

any king or emperor in the world? I repeat what I asserted, and

maintain its veracity." Profound silence ensued, and "every one

present," says Dr. Brown, "admired the intrepid boldness of the man of

humanity."

Another return to England, another survey of prisons here,

and he sets out on his fourth continental tour of humanity, travelling

through Denmark, Sweden, Russia, Poland, and then, again, Holland and

Germany. Another general and complete revisitation of prisons in

England followed, and then a fifth continental pilgrimage of goodness

through Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands, and Holland.

During his absence from England this time, his friends proposed to erect a

monument to him; but he was gloriously great in humility as in truth,

benevolence, and intrepidity. "Oh, why could not my friends," says

he, writing to them, "who know how much I detest such parade, have stopped

such a hasty measure? . . . . . It deranges and confounds all my schemes.

My exaltation is my fall—my misfortune."

He summed up the number of miles he had travelled for the

reform of prisons, on his return to England after his journey, and another

re-examination of the prisons at home, and found that the total was

42,033. Glorious perseverance! But he is away again!

having found a new object for the yearnings of his ever expanding heart.

He conceived, from inquiries of his medical friends, that that most

dreadful scourge of man's race—the plague—could be arrested in its

destructive course. He visits Holland, France, Italy, Malta, Zante,

the Levant, Turkey, Venice, Austria, Germany, and returns also by Holland

to England. The narrative glows with interest in this tour; but the

young reader—and how can he resist it if he have a heart to love what is

most deserving of love—must turn to one of the larger biographies of

Howard for the circumstances. Alas! a stroke was prepared for him on

his return. His son, his darling son, had become disobedient,

progressed fearfully in vice, and his father found him a raving maniac!

Howard's only refuge from this poignant affliction was in the

renewal of the great mission of his life. He again visited the

prisons of Ireland and Scotland, and left England to renew his humane

course abroad, but never to return. From Amsterdam this tour

extended to Cherson, in Russian Tartary. Attending one afflicted

with the plague there, he fell ill, and in a few days breathed his last.

He wished to be buried where he died, and without pomp or monument: "Lay

me quietly in the earth," said he; "place a sun-dial over my grave, and

let me be forgotten!" Who would not desire at death that he had

foregone every evanescent pleasure a life of selfishness could bring, to

live and die like John Howard?

WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON.

|

|

|

William Lloyd Garrison

(1805-79) |

The

institutions and social conditions of the United States are peculiarly

favourable to the rising to eminence of men of great natural abilities and

decision of character, although born in poverty and with obscure

surroundings. In this volume several. eminent examples are given,

and indeed a volume of interesting biographies might be compiled, showing

how many hundreds of Americans have achieved by their own talents and

indomitable energy to the highest positions in politics, literature, and

science. Few of them have shown less personal ambition and more

devotion to a great and for many years a most unpopular cause than William

Lloyd Garrison, the ardent and fearless advocate of the abolition of

slavery throughout the Union.

Garrison's parents were poor people in the town of

Newburyport, Massachusetts. His father, a man of some literary

ability, was of loose and improvident habits, and deserted his wife, who

earned a scanty subsistence for herself and young family by nursing.

William was born on the 10th of December, 1805, and when only nine years

old began to learn shoemaking, but he was a weakly boy and the work was

too hard for him. His mother then made an arrangement by which he

was received in a school, paying by work in the house for his board and

education. He remained at school until he was thirteen years old,

when he was put to the trade of cabinet-making, at which, however, he

remained only a few months, and then turned to the more congenial business

of a compositor, being apprenticed to the printer of the Newburyport

Herald, the local newspaper. Very soon he became animated by a

desire to be a writer as well as a compositor, and sent in an article

anonymously. It was printed, and he had the gratification of putting

his own contribution into type, his associates in the printing office

little thinking that the new writer was among them. This article was

soon followed by others, and it became known that the gentle-mannered,

studious, and enthusiastic apprentice was the author. He then

contributed to the Salem Gazette a series of articles signed "Aristides,"

in which he endeavoured to arouse his countrymen to a sense of the worst

degradation and wickedness of slavery. These articles directed

attention to his abilities; and when only nineteen years old he succeeded

to the editorship of the paper on which he had been employed. He

entered on his duties with characteristic ardour; and two years afterwards

extended his sphere of work by becoming proprietor and editor of the

Free Press. Not unfrequently he himself set up his leaders

in type without previously writing them out—composing in his mind and

composing with the types at the same time. About this time he

appears to have been greatly interested in the Greek struggle for freedom,

and even to have contemplated volunteering for military service in the

cause.

As a journalist he was commercially unsuccessful, and, in

1827, he went to Boston, where he worked for some months as a journeyman

printer, and engaged in the advocacy of peace, temperance, and

anti-slavery. He soon again reached the editor's desk, and for the

next two years was busily employed on the National Philanthropist,

the Journal of the Times, and the Genius of Universal

Emancipation, the last named being published at Baltimore, where he

suffered an imprisonment of seven weeks for a libel into which he was led

by his enthusiastic denunciation of slavery, being unable to pay the fine

imposed. A New York merchant, Mr. Tapping, supplied the money

required, and Garrison was liberated. He was now recognized as a

prominent public character, and obtained the friendship of Mr. Clay and

Mr. Webster, the eminent politicians, who sympathized with his views.

Having delivered emancipation lectures at New York and other

places, he returned to Boston, and in 1881 started the Liberator,

which soon became the leading organ of the anti-slavery party, and which

he carried on until 1860, when the great work for which he had so long

laboured was achieved, and slavery in the United States was abolished.

Of all the labourers in the cause, Garrison was the most outspoken an and

courageous. Nothing daunted him. Almost every post brought him

letters threatening assassination; the State legislature of Georgia

offered a large reward to any person who should bring him into Georgia,

where he might be convicted according to the laws of that State.

Mobs in Boston (the cradle of American national liberty, but strangely

oblivions of the rights of men with black skins) attacked him, broke up

the meetings at which he spoke, and he was once dragged by a rope through

the streets, and would have been sacrificed to the popular fury, if the

Mayor had not rescued him and imprisoned him to save his life. He

supported himself for some time by working in the day as a journeyman

printer, and giving hours at night to the editing and setting up his own

paper.

His labours soon bore fruit. Before the Liberator

had been established two years, the New England Anti-Slavery Society was

formed, and Garrison visited England as the agent for the purpose of

enlisting the sympathy of English Abolitionists. Clarkson and

Brougham eagerly welcomed him; and on his return other Anti-Slavery

societies were established. He became President of the American

Anti-Slavery Society, and of the New England Non-Resistance Society; and

notwithstanding the opposition he excited, and the positive danger he

encountered, he carried on the work: to which he had devoted his life,

with undiminished courage and energy.

Other visits to England were made in 1846 and 1848, and he

was received with the greatest respect as the leader of the American

emancipation party. When slavery was abolished in 1865 his friends

presented him with 30,000 dollars (£6,000), as an acknowledgment of his

services; and he was honoured by an invitation from President Lincoln and

the Federal Government to join them in an official visit to Fort Sumter,

on the conclusion of peace between the Northern and Southern States.

In 1866 he was again in England, and was entertained at a

public breakfast in St. James's Hall, Mr. Bright occupying the chair, and

the Duke of Argyll and Earl Russell being among the speakers.

His great work was accomplished, and he passed the remainder

of his life in honoured and well-earned leisure. He possessed a

taste for literature, evidenced by a volume of poems published in 1847;

and the selection from his writings and speeches, issued in 1852, show the

persevering energy and eloquence he displayed in the advocacy of the cause

to which he was devoted.

He died at New York, on the 24th of May, 1879; and the words

of a London newspaper fairly represent the general appreciation of his

character: "One of the most striking, we might say one of the most heroic

careers of modern times, closed with Mr. Garrison's life. It

probably requires evils as gigantic as slavery to produce men of such

striking devotion to a self-forgetting mission, and it is satisfactory to

believe that when such wrongs are to be assailed, human nature is still

equal to the production of the enthusiasm, or even fanaticism, which the

struggle against them needs."

THE TRIUMPHS OF ENTERPRISE.

═════════════════════

INTRODUCTION.

_______

WITHOUT Enterprise there would have been no

civilization, and there would now be no progress. To try, to

attempt, to pass beyond an obstacle, marks the civilized man as

distinguished from the savage. The advantage of passing beyond a

difficulty by a single act of trial has offered itself, in innumerable

instances, to the savage, but in vain; it has passed him by unobserved,

unheeded. Nay, more: when led by the civilized man to partake of the

advantages of higher life, the savage has repeatedly returned to his

degradation. Thus it has often been with the native Australian.

A governor of the colony, about sixty years ago, by an innocent stratagem

took one of the native warriors into his possession, and strove to

reconcile him to the habits of civilized life. Good clothes and the

best food were given him; he was treated with the utmost kindness, and,

when brought to England, the attention of people of distinction was

lavished upon him. The Australian, however, was at length re-landed

in his own country, when he threw away his clothes as burdensome

restraints upon his limbs, displayed his ancient appetite for raw meat,

and in all respects became as rude as if he had never left his native

wilderness. Another trial was made by a humane person, who procured

two infants—a boy and a girl—believing that such an early beginning

promised sure success. These young Australians were most carefully

trained, fed, and clothed, after the modes of civilized Europe, and inured

to the customs of our most improved society. At twelve years old

they were allowed to choose their future life, when they rejected without

hesitation the enjoyments of education, and fled to their people in the

background to share their famine, nakedness, and cold.

A savage would perish in despair where the civilized man

would readily discover the mode of extricating himself from difficulty;

and yet, in point of physical strength, it might be that the savage was

superior. Enterprise is thus clearly placed before the young reader

as a quality of mind. He may display it without being gifted with

strong corporeal power; it depends on thought, reflection, calculation of

advantage. Whoever displays it is sure to be in some degree regarded

with attention by his fellow-men; it wins a man the way to public notice,

and often to high reward, almost unfailingly. But the purpose of the

ensuing pages is not to place false motives before the mind; to display

any excellence with a view expressly to notice and reward, and not from

the wish to do good or to perform a duty, is unworthy of the truly correct

man. The promptings of duty and beneficence are evermore to be kept

before the mind as the only true guides to action.

In the instances of Enterprise presented in this little

volume, the young reader will not discover beneficence to have been the

invariable stimulant to action. Where the actor displays a

deficiency in the high quality of mercy, the reader is recommended to

think and judge for himself. The instances have been selected for

their striking character, and the reader must class them justly. Let

him call courage by its right name; and when it is not united with

tenderness, let the act be weighed and named at its true value.

CHAPTER I.

BESIDES the inevitable contests with wild animals

primeval men would have had to encounter peril, and to overcome difficulty

in the fulfilment of the natural desire possessed by some of them to visit

new regions of the earth. Even if the theory be true which is

supported by hundreds of learned volumes, that man's first habitation was

in the most agreeable and fertile portion of Asia, by the banks of the

Tigris and Euphrates, the native characteristic of enterprise would impel

some among the first men to go in quest of new homes or on journeys of

exploration and adventure; and, as the human family increased, removal for

the youthful branches would be absolutely necessary.

To these primal travellers the perils of unknown adventure

and the pressure of want would most probably have proved excitements too

absorbing to have permitted a chronicle of their experience, even had the

art of writing then existed. But details of adventure as wild and

strange, perhaps, as any encountered by those earliest travellers exist in

the volumes of recent discoverers; and while glancing at these we may

imagine to ourselves similar enterprises of our race in the thousands of

years which are past and gone. Let it be observed, in passing, that

the young reader will find no books more rich and varied in interest than

those of intelligent travellers; and if our slight mention of a few of

their names as partakers in the "Triumphs of Enterprise" should induce him

to form a larger acquaintance with their narratives, it can scarcely fail

to induce thoughts and resolves that will tend to his advantage.

|

|

|

Hugh Clapperton (1788—1827),

Scottish traveller and explorer

of

West and Central Africa. |

The perils to be undergone in desert regions are not more forcibly

described by any travellers than by Major Denham, Dr. Oudney, and Captain

Clapperton the celebrated African discoverers. "The sandstorm we had

the misfortune to encounter in crossing the desert," says the former,

"gave us a pretty correct idea of the dreaded effects of these hurricanes.

The wind raised the fine sand with which the extensive desert was covered

so as to fill the atmosphere and render the immense space before us

impenetrable to the eye beyond a few yards. The sun and clouds were

entirely obscured, and a suffocating and oppressive weight accompanied the

flakes and masses of sand which, I had almost said, we had to penetrate at

every step. At times we completely lost sight of the camels, though

only a few yards before us. The horses hung their tongues out of

their mouths, and refused to face the torrents of sand. A sheep that

accompanied the kafila (the travelling train), the last of our stock, lay

down on the road, and we were obliged to kill him and throw the carcase on

a camel. A parching thirst oppressed us, which nothing alleviated.

We had made but little way by three o'clock in the afternoon, when the

wind got round to the eastward and refreshed us a little; with this change

we moved on until about five, when we halted, protected in a measure by

some hills. As we had but little wood our fare was confined to tea,

and we hoped to find relief from our fatigues by a sound sleep.

That, however, was denied us; the tent had been imprudently pitched, and

was exposed to the east wind, which blew a hurricane during the night; the

tent was blown down, and the whole detachment were employed a full hour in

getting it up again. Our bedding and every thing within the tent was

during that time completely buried by the constant driving of the sand.

I was obliged three times during the night to get up for the purpose of

strengthening the pegs; and when in the morning I awoke two hillocks of

sand were formed on each side of my head some inches high."

Dr. Oudney, the partner of Denham and Clapperton, in their

adventurous enterprise, affords details more frightful in character.

"Strict orders had been given during a certain day of the journey," he

informs us, "for the camels to keep close up, and for the Arabs not to

straggle—the Tibboo Arabs having been seen on the look-out. During

the last two days," he continues, "we had passed on the average from sixty

to eighty or ninety skeletons each day; but the numbers that lay about the

wells of El-Hammar were countless; those of two women, whose perfect and

regular teeth bespoke them young, were particularly shocking-their arms

still remained clasped round each other as they had expired, although the

flesh had long since perished by being exposed to the burning rays of the

sun; and the blackened bones only were left; the nails of the fingers and

some of the sinews of the hand also remained, and part of the tongue of

one of them still appeared through the teeth. We had now passed six

days of desert without the slightest appearance of vegetation, and a

little branch was brought me here as a comfort and curiosity. A few

roots of dry grass, blown by the winds towards the travellers, were

eagerly seized on by the Arabs, with cries of joy, for their hungry

camels. Soon after the sun had retired behind the hills to the west,

we descended into a wadey, where about a dozen stunted bushes, not trees,

of palm marked the spot where water was to be found. The wells were

so choked up with sand, that several cart-loads of it were removed

previous to finding sufficient water; and even then the animals could not

drink till nearly ten at night."

Nor was it merely the horrors of the climate which these intrepid

travellers had to encounter. Their visitation of various savage tribes

drew them into the circle of barbarous quarrels. The peril incurred by

Major Denham, while accompanying the Bornou warriors in their expedition

against the Felatahs, is unsurpassed for interest in any book of travels. "My horse was badly wounded in the neck, just above the shoulder, and in

the near hind leg," says the Major, describing what had befallen himself

and steed in the encounter;

"an arrow had struck me in the face as it

passed, merely drawing the blood. If either of my horse's wounds had been

from poisoned arrows I felt that nothing could save me. [The tribe he

accompanied had been worsted.] However, there was not much

time for reflection; we instantly became a flying mass, and plunged in

the greatest disorder, into that wood we had but a few hours before moved

through with order, and very different feelings. The spur had the effect

of incapacitating my beast altogether, as the arrow, I found afterwards,

had reached the shoulder-bone, and in passing over some rough ground he

stumbled and fell. Almost before I was on my legs the Felatahs were upon

me; I had, however, kept hold of the bridle, and, seizing a pistol from

the holsters, I presented it at two of these ferocious savages, who were

pressing me with their spears: they instantly went off; but another, who

came on me more boldly, just as I was endeavouring to mount, received the

contents somewhere in his left shoulder, and again I was enabled to place

my foot in the stirrup. Re-mounted, I again pushed my retreat; I had not,

however, proceeded many hundred yards when my horse came down again, with

such violence as to throw me against a tree at a considerable distance;

and, alarmed at the horses behind, he quickly got up and escaped, leaving

me on foot and unarmed. A chief and his four followers were here butchered

and stripped; their cries were dreadful, and even now the feelings of that

moment are fresh in my memory; my hopes of life were too faint to deserve

the name. I was almost instantly surrounded, and incapable of making the

least resistance, as I was unarmed. I was as speedily stripped; and,

whilst

attempting first to save my shirt and then my trousers, I was thrown on

the ground. My pursuers made several thrusts at me with their spears, that

badly wounded my hands in two places, and slightly

my body, just under my ribs, on the right side; indeed I saw nothing

before me but the same cruel death I had seen unmercifully inflicted on

the few who had fallen into the power of those who now had possession of

me. My shirt was now absolutely torn off my back, and I was left perfectly

naked.

"When my plunderers began to quarrel for the spoil, the idea of escape

came like lightning across my mind, and, without a moment's hesitation or

reflection, I crept under the belly of the horse nearest me, and started

as fast as my legs could carry me for the thickest part of the wood. Two

of the Felatahs followed, and I ran on to the eastward, knowing that our

stragglers would be in that direction, but still almost as much afraid of

friends as of foes. My pursuers gained on me, for the prickly underwood

not only obstructed my passage but tore my flesh miserably; and the

delight with which I saw a mountain-stream gliding along at the bottom of

a deep ravine cannot be imagined. My strength had almost left me,

and I seized the young branches issuing from the stump of a large tree

which overhung the ravine, for the purpose of letting myself down into the

water, as the sides were precipitous, when, under my hand, as the branch

yielded to the weight of my body, a large liffa, the worst kind of serpent this country

produces, rose from its coil, as if in the act of striking. I was

horror-stricken, and deprived for a moment of all re-collection; the

branch slipped from my hand, and I tumbled headlong into the water

beneath; this shock, however, revived me, and with three strokes of my

arms I reached the opposite bank, which with difficulty I crawled up, and

then, for the first time, felt myself safe from my pursuers.

"Scarcely had I audibly congratulated myself on my escape, when the

forlorn and wretched situation in which I was, without even a rag to cover

me, flashed with all its force upon my imagination. I was perfectly

collected, though fully alive to all the danger to which my state exposed

me, and had already began to plan my night's rest in the top of one of the

tamarind trees, in order to escape the panthers, which, as I had seen,

abounded in these woods, when the idea of the liffas, almost as numerous,

and equally to be dreaded, excited a shudder of despair.

"I now saw horsemen through the trees, still farther to the east, and

determined on reaching them if possible, whether friends or enemies. They

were friends. I hailed them with all my might; but the noise and confusion

which prevailed, from the cries of those who were falling under the Felatah spears, the cheers of the Arabs rallying and their enemies

pursuing, would have drowned all attempts to make myself heard, had not

the sheikh's negro seen and known me at a distance. To this man I was

indebted for my second escape: riding up to me, he assisted me to mount

behind him, while the arrows whistled over our heads, and we then galloped

off to the rear as fast as his wounded horse could carry us. After we had

gone a mile or two, and the pursuit had cooled, I was covered with a bornouse; this was a most welcome relief, for the burning sun had already

begun to blister my neck and back, and gave me the greatest pain; and had

we not soon arrived at water I do not think it possible that I could have

supported the thirst by which I was being consumed."

|

|

|

Mungo Park (1771 – 1806)

Scottish explorer of the

African continent. |

The exciting narrative of travel in the central regions of Africa the

young reader may pursue in various volumes, from those describing the

adventures of Leo Africanus, in 1513, to the later narrations of the

exploration of the regions through which the Niger, or Quorra, flows, by

Mungo Park, Captain Clapperton, the brothers Lander, and others. More

recently we have had related the grand discoveries by

Livingstone, who with indomitable resolution made the way northward from

the Cape to the equator, and then crossed the Continent from the west to

the east coast, revealing the wonders of the Zambesi river, with the

mighty cataracts, and the rich lands and strange people of a hitherto

unknown part of Africa. Then there are the discoveries of the great lakes,

Tanganyika, Victoria, and Albert Nyanza, by Grant, Speke, Burton, and

others; and the visit of Livingstone to that marvellous region, where he

was lost in the trackless savage regions till Stanley found him; and

afterwards the traversing of the Continent, from east to west, by

Lieutenant Cameron, who made "a walk across Africa"; and the brilliant

exploit of Stanley, who literally fought his way for two thousand miles

through unknown regions, and made known to us that magnificent river, the

Congo or Zaire, previously only known in its lower course.

We need not trace the steps of all the explorers we have named. The story

of Livingstone, the factory boy, missionary, and traveller, has been often

told; but we may relate, in a brief manner, as typical of the unfailing

perseverance and courage of African travellers, the story of the search

for him by Stanley, and the discovery of the enfeebled but brave old man

at Ujiji, on the shores of Tanganyika.

|

|

|

David Livingstone (1813 –1873)

Medical missionary and explorer

in central Africa |

In 1865 Livingstone undertook his last African exploration, at the

solicitation of Sir Roderick Murchison, and under the auspices of the

Royal Geographical Society. His object was to determine the watershed of

Central Africa (the elevated region in which the great rivers took rise,

flowing in various directions), by an examination, in the first place, of

the regions lying between Lake Nyassa (which he had discovered on a

previous journey), and Lake Tanganyika, lying farther north. In other

words, his object was to explore a tract of country previously unknown to

geographers, on the eastern part of Africa, south of the equator, and

extending over nearly twelve degrees of latitude, or about eight hundred

miles. Livingstone started from Zanzibar, taking with him twelve

well-armed sepoys from Bombay, nine "Johanna men," or natives of the

Comoro Isles, nine native Africans, and some camels, buffalos, mules, and

donkeys. Beads and coloured calico, likely to suit the native taste, was

also taken for purposes of barter and conciliation. Great hardships were

encountered; for many miles a road had literally to be cut through the

bush, and the difficulties disgusted the sepoys, who mutinied, and were

sent back to the coast. Ujiji, a native town near the eastern shore of

Lake Tanganyika, was at length reached; and after resting a short time,

Livingstone crossed the lake, and explored the western and northern

coasts, discovering a large river, the Lualaba.

Supplies sent from Zanzibar to Livingstone were stolen by Arabs who were

entrusted with the duty of following on his track; and the privations and

dangers endured by this illustrious traveller were great; and for more

than three years no communication was received from him. Vague rumours of

his death reached Zanzibar, but were not believed, and various plans were

suggested by which his fate might be ascertained.

While this painful uncertainty prevailed, Mr. James

Gordon Bennett, the proprietor of the New York Herald, suggested to one of his travelling

correspondents, Mr. Stanley, a man of remarkable energy and great

experience, who had led an extraordinary life of adventure, that he should

undertake a search for the lost traveller. The task was immediately

accepted; and in March, 1871, Stanley set out for Zanzibar, on his

important and adventurous mission.

Before proceeding further with the story, we will give a brief

biographical sketch of the indomitable and successful explorer.

|

|

|

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904)

Welsh-born journalist and explorer |

Stanley is a surname adopted for a reason which will be noticed. The

traveller's real name is John Rowlands, and he was born, in 1840, in great

poverty near Denbigh, Wales. From the age of 3 to 13 he was brought up in

the poorhouse of St. Asaph, where he received a fair education, which

enabled him, after leaving the poorhouse, to act for

a year as a teacher at Mold. He then went as a cabin-boy to New Orleans,

where he attracted the attention of a merchant named Stanley, who adopted

him, but as he died intestate, the youth received nothing from him but his

name, which he assumed. He served in the Confederate army, but being taken

prisoner, volunteered into the United States navy, and became a petty

officer of the ironclad Ticonderoga. After the close of the war, he

travelled in Turkey and Asia Minor, and on his way back, went to St. Asaph

for the purpose of giving a dinner to the children in the poorhouse where

he had once been a pauper child. On reaching America he became connected

with the newspaper press, and, as correspondent of the New York Herald,

accompanied the British expedition to Abyssinia.

Having prepared himself at Zanzibar by a diligent study of books on the

geography of Africa, and the collection of clothes of various qualities,

brass wire, beads, and other articles adapted for traffic, and carpenter's

tools, and ammunition, he started for the interior. Two white men, Farquhar and Shaw, both sailors, accompanied him, and about one hundred

and ninety native soldiers and baggage-carriers completed the expedition. Boats, divided into sections and easily fitted together, were taken for

the purpose of navigating lakes and rivers.

The two white men soon succumbed to the fatal effects of the climate; and

Stanley was left, almost unsupported, to conduct the expedition. He was

several times attacked by fever, several of his men died; wars were raging

among the native tribes; but, conquering almost incredible difficulties,

he struggled on, and on November, seven months after quitting Zanzibar,

reached Ujiji.

He had been told by natives and Arab traders that a white man, no doubt

Livingstone, had been seen at various places; but the statements were

vague and contradictory. At Ujiji, Stanley hoped to be rewarded by finding

the object of his search, and he was not disappointed. He approached the

little Arab town with all the dignity he could assume, determined to make

a favourable impression; his men discharged their muskets, shouted, and

blew shrill notes on Stanley's bugle. The people of the town flocked out,

eagerly welcoming the stranger; but no voice was so surprising to him as

that of a black man, who ran up and shouted, "How do you do, Sir?" "Who

are you?" replied the traveller,

in amazement at hearing the English words. "I'm the servant of Dr.

Livingstone," was the reply; and then the man ran eagerly back to the

town.

Stanley felt that he had achieved the mission he had undertaken, and with

a rejoicing heart he marched into the town at the head of his followers,

with the American flag flying. A group of grave-looking elderly men awaited

him, and among them was an old man, withered and grey, with the pale

face of a European. Stanley stepped hastily forward, but checked himself,

and with a bow of courtesy said, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume." The reply

was simply "Yes;" and then the veteran explorer led his new-made friend

to the house he occupied; and Stanley told the news from home, and how he

had been sent on the apparently almost hopeless quest. That day was the

10th of November, 1,871, nine months since the young traveller had left

Zanzibar, and more than two years since he had received instructions at

the Grand Hotel, Paris.

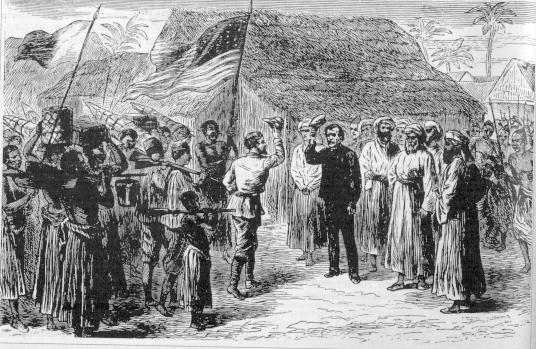

|

|

|

Henry Morton Stanley of the New York Herald

meets David Livingstone at Ujiji, 1871. |

Stanley afterwards accompanied Livingstone on explorations around the

northern portion of the lake, and returned in 1872. He arrived in England,

and related his adventures at the meeting of the British Association at

Brighton; the Queen presented him with a gold snuff-box set with

diamonds, and he received the gold medal of the Royal Geographical

Society.

In 1874 he was commissioned by the proprietors of the New York Herald and

the London Daily Telegraph to continue the work of Livingstone and explore

the lake country of equatorial Africa. He left the east coast in November,

at the head of 300 men, and the difficulties he had to encounter may be

estimated by the fact that in three months he had lost 192 men by death or

desertion. He succeeded in making most important discoveries respecting

Lake Victoria Nyanza and the adjacent

country, and was then unheard of for nearly two years. About the end of

August, 1877, he appeared on the west coast, at the mouth of the Congo, or

Zaire, having succeeded, after terrible sufferings and almost continued

fighting with the natives, in tracing that great river from its hitherto

unknown head waters near Lake Tanganyika, to its mouth, and so solving the

second great geographical problem respecting the rivers of Africa.

Surely there was never a greater example of perseverance than was

exhibited in these two journeys of exploration by the correspondent of an

American newspaper. "Go forward," was his unvarying motto; and splendid,

indeed, was the result of his courage and fidelity to duty.

It might have been supposed that, after such great exertions, even a man

so energetic as Stanley would have desired repose. That, however, was not

the case. He remained in England only long enough to pass through the

press an admirably written narrative of his explorations, and in 1879

again started for the east coast of Africa, resolved to undertake another

journey of exploration in the interior on a more extensive scale.

CAPTAIN COCHCRANE.

|

|

|

John Dundas Cochrane

(1780—1825) |

Of all

travellers in the northern regions, though not the most intellectual, the

hardiest and most adventurous is Captain Cochrane. He had originally

intended to devote himself to African discovery, conceiving himself

competent for that arduous undertaking, by experience of the fatigues he

had borne in laborious pedestrian journeys through France, Spain, and

Portugal, and in Canada. "The plan I proposed to follow," says he,

"was nearly that adopted by Mungo Park, in his first journey—intending to

proceed alone, and requiring only to be furnished with the countenance of

some constituent part of the government. With this protection, and

such recommendation as it would procure me, I would have accompanied the

caravans in some servile capacity, nor hesitated even to sell myself as a

slave, if that miserable alternative were necessary, to accomplish the

object I had in view. In going alone, I relied upon my own

individual exertions and knowledge of man, unfettered by the frailties and

misconduct of others. I was then, as now, convinced that many people

travelling together for the purpose of exploring a barbarous country, have

the less chance of succeeding; more especially when they go armed, and

take with them presents of value. The appearance of numbers must

naturally excite the natives to resistance, from motives of jealousy or

fear; and the danger would be greatly increased by the hope of plunder."

The answer he received from the Admiralty being unfavourable,

and thinking that a young commander was not likely to be employed in

active service, he planned for himself a journey on foot round the globe,

as nearly as it could be accomplished by land, intending to cross from

northern Asia to America at Behring's Straits. Captain Cochrane did

not realize his first intent, but he tracked the breadth of the entire

continent of Asia to Kamtschatka. Hazards and dangers befel him

frequently in this enterprise; but he pursued it undauntedly. His

perils commenced when he had left St. Petersburg but a few days, and had

not reached Novogorod. "From Tosna my route

was towards Linbane," says our adventurer,

"at about the ninth milestone from which

I sat down, to smoke a cigar or pipe, as fancy might dictate. I was

suddenly seized from behind by two ruffians, whose visages were as much

concealed as the oddness of their dress would permit. One of them,

who held an iron bar in his hand, dragged me by the collar towards the

forest, while the other, with a bayonetted musket, pushed me on in such a

manner as to make me move with more than ordinary celerity; a boy,

auxiliary to these vagabonds, was stationed on the roadside to keep a

look-out. We had got some sixty or eighty paces into the thickest

part of the forest, forest when I was desired to undress, and having

stripped off my trousers and jacket, then my shirt, and finally my shoes

and stockings, they proceeded to tie me to a tree. From this

ceremony, and from the manner of it, I fully concluded that they intended

to try the effect of a musket upon me, by firing at me as they would at a

mark. I was, however, reserved for fresh scenes; the villains, with

much sangfroid, seated themselves at my feet, and rifled my knapsack and

pockets, even cutting out the linings of the clothes in search of bank

bills or some other valuable articles. They then compelled me to

take at least a pound of black bread, and a glass of rum, poured from a

small flask which had been suspended from my neck. Having

appropriated my trousers, shirts, stockings, and shoes, as also my

spectacles, watch, compass, thermometer, and small pocket sextant, with

one hundred and sixty roubles (about seven pounds), they at length

released me from the tree, and, at the point of a stiletto, made me swear

that I would not inform against them—such, at least, I conjectured to be

their meaning, though of their language I understood not a word.

Having received my promise, I was again treated by them to bread and rum,

and once more fastened to the tree, in which condition they finally

abandoned me. Not long after, a boy who was passing heard my cries,

and set me at liberty. With the remnant of my apparel, I rigged

myself in Scotch Highland fashion, and resumed my route. I had still

left me a blue jacket, a flannel waistcoat, and a spare one, which I tied

round my waist in such a manner that it reached down to the knees; my

empty knapsack was restored to its old place, and I trotted on with even a

merry heart."

He comes up with a file of soldiers in the course of a few

miles and is relieved with some food, but declines the offer of clothes.

A carriage is also offered to convey him to the next military station.

"But I soon discovered," he continues, "that riding was too cold, and

therefore preferred walking, barefooted as I was; and on the following

morning I reached Tschduvo, one hundred miles from St. Petersburg." At

Novogorod he is further relieved by the governor, and accepts from him a

shirt and trousers.

He reaches Moscow without a renewal of danger, and thence

Vladimir and Pogost. In the latter town he cheerfully makes his bed

in a style that shows he possessed the spirit of an adventurer in

perfection. "Being too jaded to proceed farther," are his words, "I

thought myself fortunate in being able to pass the night in a cask.

Nor did I think this mode of passing the night a novel one. Often,

very often, have I, in the fastnesses of Spain and Portugal, reposed in

similar style." He even selects exposure to the open air for sleep

when it is in his power to accept indulgence. "Arrived at Nishney

Novogorod, the Baron Bode," says he, "received me kindly, placing me for

board in his own house; while for lodging I preferred the open air of his

garden; there, with my knapsack for a pillow, I passed the might more

pleasantly than I should have done or a bed of down, which the baron

pressed me most sincerely to accept." A man who thus hardened

himself against indulgence could scarcely dread any of the hardships so

inevitable in the hazardous course he had marked out for himself.

Accordingly, we find him exciting the wonder of the natives

by his hardihood in the very heart of Siberia. "At Irkutsk," is his

own relation, "in the month of January, with forty degrees of Reaumur, I

have gone about, late and early, either for exercise or amusement, to

balls or dinners, yet did I never use any other kind of clothing than I do

now in the streets of London. Thus my readers must not suppose my

situation to have been so desperate. It is true the natives felt

surprised, and pitied my apparently forlorn and hopeless situation, not

seeming to consider that, when the mind and body are in constant motion,

the elements can have little effect upon the person. I feel

confident that most of the miseries of human life are brought about by

want of a solid education—of firm reliance on a bountiful and ever

attendant Providence—of a spirit of perseverance—of patience under fatigue

and privations, and a resolute determination to hold to the point of duty,

never to shrink while life retains a spark, or while 'a shot is in the

locker,' as sailors say. Often, indeed, have I felt myself in

difficult and trying circumstances, from cold, or hunger, or fatigue; but

I may affirm with gratitude, that I have never felt happier than even in

the encountering of these difficulties." He remarks, soon

afterwards, that he has never seen his constitution equalled; but the

young reader will remember that the undaunted adventurer has strikingly

shown us how this excellent constitution was preserved from injury by

shunning effeminacy.

Yet our traveller's superlative constitution is severely

tested when he reaches the country of the Yahuti, a tribe of Siberian

Tartars. He crosses a mountain range, and halts, with the attendants

he has now found the means to engage, for the night, at the foot of an

elevation, somewhat sheltered from the cold north wind. "The first

thing on my arrival," he relates, "was to unload the horses, loosen their

saddles or pads, take the bridles out of their mouths, and tie them to a

tree in such a manner that they could not eat. The Yakuti then with

their axes proceeded to fell timber, while I and the Cossack, with our

lopatkas or wooden spades, cleared away the snow, which was generally a

couple of feet deep. We then spread branches of the pine tree to

fortify us from the damp or cold earth beneath us; a good fire was now

soon made, and each bringing a leathern bag from the baggage furnished

himself with a seat. We then put the kettle on the fire, and soon

forgot the sufferings of the day. At times the weather was so cold

that we were obliged to creep almost into the fire; and as I was much

worse off than the rest of the party for warm clothing, I had recourse to

every stratagem I could devise to keep my blood in circulation. It

was barely possible to keep one side of the body from freezing, while the

other might be said to be roasting. Upon the whole, I passed the

night tolerably well, although I was obliged to get up five or six times

to take a walk or run, for the benefit of my feet. The following

day, at thirty miles, we again halted in the snow, when I made a

horse-shoe fire, which I found had the effect of keeping every part of me

alike warm, and I actually slept well without any other covering than my

clothes thrown over me; whereas, before, I had only the consolation of

knowing that if I was in a freezing state with one half of my body, the

other was meanwhile roasting to make amends."

Captain Cochrane's constitution had so much of the power of

adaptation to circumstances, that he was enabled to make a meal even with

the savagest tribes. A deer had been shot, and the Yakuti began to

eat it uncooked! "Of course," says he, "I had the most luxurious

part presented to me, being the marrow of the fore-legs. I did not

find it disagreeable, though eaten raw and warm from life; in a frozen

state I should consider it a great delicacy. The animal was the size

of a good calf, weighing about two hundred pounds. Such a quantity

of meat may serve four or five good Yakuti for a single meal, with whom it

is ever famine or feast, gluttony or starvation."

The captain's account of the feeding powers of the Yakuti

surpasses, indeed, anything to be found in the narratives of travellers,

which are proverbial for wonder. "At Tabalak I had a pretty good

specimen," he continues, "of the appetite of a child, whose age could not

exceed five years. I had observed it crawling on the floor, and

scraping up with its thumb the tallow-grease which fell from a lighted

candle, and I inquired in surprise whether it proceeded from hunger or

liking of the fat. I was told from neither, but simply from the

habit in both Yakuti and Tungousi of eating wherever there is food, and

never permitting anything that can be eaten to be lost. I gave the

child a candle made of the most impure tallow, a second, and a third—and

all were devoured with avidity. The steersman then gave him several

pounds of sour frozen butter; this also he immediately consumed.

Lastly, a large piece of yellow soap—all went the same road; but as I was

convinced that the child would continue to gorge as long as it could

receive anything, I begged my companion to desist as I had done. As

to the statement of what a man can or will eat, either as to quality or

quantity, I am afraid it would be quite incredible. In fact, there

is nothing in the way of fish or meat, from whatever animal, however

putrid or unwholesome, but they will devour with impunity; and the

quantity only varies from what they have to what they can get. I

have repeatedly seen a Yakut or a Tungouse devour forty pounds of meat in

a day. The effects are very observable upon them, for, from thin and

meagre-looking men, they will become perfectly pot-bellied. I have

seen three of these gluttons consume a reindeer at one meal."

These doings of the Siberian Tartars, our young readers will

have rightly judged, however, are not among the most praiseworthy or

dignified of the "Triumphs of Enterprise;" and we turn, with a sense of

relief, to other scenes of adventure.

The grand mountain range of the Andes, or Cordilleras, with

its rugged and barren peaks and volcanoes, and destitution of human

habitants, sometimes for scores of miles in the traveller's route, has

afforded a striking theme for many writers of their own adventures in

South America. Mr. Temple [ED.—Edmund Temple], a traveller in

1825, affords us some exciting views of the perils of his journey from