|

A HUMMABEE WAR.

WE'RN

sittin' i'th' nook, th' owd stockin' mender an' me, an' starin' at

th' foire. We'd noather on us owt to say for awhile, an'

that's a sign o' thinkin'. It wur a cowd, woisty neet, no' fit

for gooin' eaut; that wur one reeason ut kept me awhoam, t'other wur

th' state o'th' exchequer. Th' funds wur low, an' th' wynt wur

hee. Aw're quite in a humour for thinkin', so wur th' owd

ticket; but as yet we held eaur thowts to eaursels. At last th'

owd rib broke eaut.

"Dost yer th' wynt, Ab?" hoo said, an' hoo hutched closer to

th' foire.

"Aw do," aw said. "Winter's soon on us, an' we'n had no

autumn. We'n nobbut had two seeasons this year—summer, an'

neaw winter. It'll be hard wi' folk ut areno prepared for it.

A blazin' wot summer, an' neaw ice an' snow, an' a wynt ut shakes th'

heause. Han th' coals come'n?"

"Aye, th' hencote's welly buried wi' 'em."

"An' th' fleaur?"

"Aye, th' cart's bin to-day."

"An' th' pottitoes?"

"They coome at th' same time as fleaur."

"God be praised!—we con face th' winter neaw!"

"But han we nob'dy to think abeaut nobbut eaursels?"

"Aw'd forgetter that. Ther's a duty one mon has to'ard

another, but seldom thowt abeaut by th' rich; not becose the'r

hearts are harder, but they so seldom seen poverty as we seen it, ut

it isno' aulus present to the'r minds. Some ud give if they

knew heaw. Beggars ut sing i'th' lone, they know, are

imposters, an' real poverty hoides itsel' i' nooks an' ut back o'

durs, as if it didno' want to be seen. But it's theere."

Th' owd lass put her studyin' cap on, an' lockin' her arms o'er her

appron strengs, began to put questions to me ut no mon i'th' wo'ld

could onswer.

"When we'rn bein' browt up, Ab," hoo began, "things wur very

bad. We could ackeaunt for that by everythin' bein' so skase.

But neaw everythin's plentiful, an' some folk are no betther off for

it. Heaw con it happen?"

"They con get no wark to do," aw said, but aw knew at th'

same time that wouldno' satisfy her.

"If they con get no wark to do, there's nowt wants dooin',"

hoo said. "So we owt to be able to sit reaund th' foire ov a

neet tellin' boggart tales an' axin' riddles. If there's no

wark to be done, it's as plain as owd Penky's nose ther's enoogh for

everybody. So what keeps it fro' 'em?"

"Some folk sayn it's becose brass is so chep."

"Then folk owt to be able to get moore on it."

"Aye, but then that's a woman's way o' reeasonin'.

Theau sees a suverin' isno' wo'th twenty shillin' neaw."

"It may no' be, but theau conno' get one for less, lest theau

picks somebody's pocket."

Th' owd lass wur droivin' me into a corner, an' if aw didno'

mind aw should be fast, so aw had to shift my premises.

"Theau sees we'n moore meauths to feed nur we con find stuff

to put in 'em," aw said.

"What, wi' plenty o' everythin'?"

"Aye, but some on't's locked up, an they conno' get at it

beaut a silver key."

"Why didt'no' say so at fust? If brass is chep, poor

folk owt to ha' moore on it; an' if they had moore on it they could

unlock that great wareheause dur ut keeps in ro' 'em."

"Aye, but if brass is chep, they conno' get howd on't beaut

worchin' for it."

"But what's th' use o' worchin' if ther's enoogh o' wark

done? Mun they sit ceauntin' cinders, or goo a-makkin' roads

ut are no' wanted?"

"But i' case o' makkin' roads, theau sees, what they getten

for the'r wark comes eaut o'th' rates, so everybody has to pay the'r

share."

"Well, if we han to pay 'em for wark ut isno' wanted, we met

as weel pay 'em for dooin' nowt. They'd ate less.

"An' for that matter, ther'd be less wear an' tare o' clooas.

But that doesno' onswer th' question. We're as far off as

ever."

"Summot tells me, Ab," th' owd rib said, "ut we are no'

lookin' th' reet road fort' remedy these things. There's bin

to mich swaggerin' abeaut heaw mony childer they han, an' heaw mony

they han had. An' they comfort the'rsels by sayin' ut God

never sent meauths beaut findin' summat to put in 'em. But

that's sayin' a thing for sayin's sake. If He does send mayte

for 'em it's sometimes very thin; an' what ud do for two or three

would ha' to be weel byetten eaut if it had to do for nine.

Look at Bogey's childer, what clemmed rottans they looken! aw yerd

one on 'em sayin' he wished they'd lessen him stop i' heaven, if he

coome fro' theere. But he'd no remembrance on it. But

he'd no deaut they'd better dooin's nur they had deawn here.

Oh, but he'd get to be a big lad, an' he'd ha' to work, that is, if

they could find him owt to do. Aye, if they could."

"Well, he'll ha' th' same chance as other lads, aw reckon."

"Aye, will he? But wouldno' he ha' stooden a betther

chance if ther' wurno' so mony after th' same job? Ther's four

on 'em i'th' fowt wi' a reaund two dozen, tak' 'em o together, lads

an' wenches. What is ther' for 'em to do when they getten up?

Wayvin's wo'th nowt; factories are full; at mechanics' shops they're

baggin' th' owd uns, an' conno' find places for th' young uns;

bookkeepers are walkin' abeaut wi' soft shoon; breeksetters had gan

o'er teein' ropes round the'r legs; an' joiners are gooin' abeaut

sellin' chips. What trade mun these two dozen be put to?"

"Aw con hardly tell!"

"An' heaw mun they be kept if they'n no trade to go to?"

"That's another puzzler. But theau wouldno' think times

wur bad to see th' creawds aw see ov a Setturday, creawdin'

everywheere, gooin' to footbo' matches, an' th' exhibitions; an'

donned up as if it wur Sunday. These mun be findin' summat to

do somewheere."

"But theau mun recollect, Ab, ut some o' thoose han had

feythers an' mothers ut han thowt ther summat betther to speckilate

in nur a heause full o' childer."

"Aye, that's happen it. Spekilatin' i' childer is as

bad as keepin' dogs an' pigeons! Foos o' feythers used to say

the'r childer 'ud look to 'em when they geet owd. Well, they

had used to do, but neaw if th' yung uns wanten owt the'rsel's they

fly'n to th' owd folks, so things are turn't abeaut. An' they

poon at th' owd pap till they'n drained th' last drop, an' th' owd

uns han to goo i' th' warkheause. Childer profitable?

Well, ther's some exceptions, to be sure. Aw know a family,

neaw, wheere th' yead o' th' consarn wur gettin' good money, so he

could afford to bring up his childer to do nowt. They shouldno'

be i' th' road o' other working folk. Th' labour market he

used to say, wur o'erstocked, an' he'd take care he wouldno' be one

to thrutch another in. But he made one grand mistake. He

didno' calkilate ut he should ever be too owd for his wark, or he

met dee, or his mesther goo to th' dogs. But his mesther

shunted him on acceaunt of his age, an' he hadno' browt ony of his

sons up to do his wark. Well, he'd saved nowt, so what wur th'

family to do? They lived on the'r friends as lung as they'd

have 'em; an' thoose ut wurno' partiklar abeaut bein' honest, took

to other meeans, an' th' family wur brokken up."

"But if they'd bin browt up to trades they'd happen ha'

thrutched someb'dy else o' one side, as some o'th' same sort are

dooin' neaw."

"Well then, it's no use argyin' ony furr. If ther's too

mony on us, ther's too mony on us. We're too thrung upo' th'

clod; an' it's time it wur thinned. Some folks sayn emigrate.

But that's no cure. They'n bin gooin' by thousands eaut o'th'

poorest county under th' sun; an' thoose ut are laft are no betther

off for it. Thoose ut emigrate dunno' stond idle when they

getten across. If they begin a-farmin' they'n no market for

the'r stuff, so they go'en i'th' factory, an' begin a manifacturin'

for the'rsels what we used to mak' for 'em, an' thoose ut went

before 'em, so what betther off are we?"

"Aw conno' tell. It's eaut o' my latitude, as owd Crop

used to say when he're so drunken he couldno' find th' road whoam.

But it's hard to see folk clemmin', when they're willin' to work,

an' wi' plenty reaund 'em."

"Neaw aw'll tell thi what we wanten, an' that ud set us

straight. It's never bin thowt abeaut afore, or if it has,

it's never bin whisper't, becose whoever broaches it is sure to get

into warmer wayter nur th' Owd Lad boils his eggs in.

Theau'll think no betther o' me for broachin' it; but it leaves o'th'

chance we han. Ther's nowt else 'll do, aw'm quite persuaded."

"What is it, as theau'rt so loth to mention it?"

"That ut'll mak' thi yure go white wi' a neet's frost; an'

it's getten autumn colours on it o ready. We wanten a gradely

roozin war!"

"A what, Ab?"

"A gradely roozin war—not wi' forriners, but among eaursels."

Aw thowt th' owd lass ud ha' flown o'er i'th' nook!

"A war, Ab! a war!" hoo skriked eaut.

"Aye, we'n bin at peeace i' this country till we're fast," aw

said, "an' th' sword 'll cut th' difficulty. Nowt else will."

"Art' gooin' crazy, Abram?"

"It wur th' way ut th' Jews did i' owden time. If they

geet to' thrung on, they geet a tip fro' some great peawer to mak'

war on some neighbour; an' they slowthert 'em by hunderts o'

theausands. Then someb'dy had a good reign, an' th' country

begun to prosper. Owd Joshy waked wi' his job, so ut he could

knock 'em o'er i'th neet as weel as th' day. But they made a

mistake i' no killin' th' women an' th' childer."

"Theau brute!"

"Oh, they did. Th' conquerors took so many o'th' women

for wives ut in a year or two th' country wur o'er-run wi' childer

like rabbits. Then when these wur browt up ther' had to be

another slowter. So they'rn nearly aulus feightin'."

"An' that ud be good for this country, would it?"

"Aye, if they'd put th' women i'th' front o'th' battle, an'

let 'em be shot th' fust of onybody, there'd be a deeal moore

quietness after that."

"Aye, an' a nice mess yo' men ud be in wi' no women to look

after yo'. Yo'd be as dirty as owd Moll Hollant! If that

ud be th' wo'st."

"War is as natural as peace. If we are no' feightin'

we're trailin' th' cooat reaund for someb'dy to put the'r foout on

it, an 'it ud be natteral i' this case. Look at eaur hummabees,

they'n a way o' regilatin' things ut we met profit by."

"Wheay, what done they do?"

"When they getten too thrung i'th' hive, an' honey fo's

short, they kill thoose ut dunno' work. Theau may see 'em

tumblin' eaut by scores, an' hunderts. An' that's by a law o'

nature. Men are th' only crayters ut worken beside bees, an'

why shouldno' th' same law govern 'em

"Bees han stings an' men hanno'."

"Nawe, but women han. Th' only difference ther' is,

women carry'n theer's i' the'r meauths. But we're gettin' off

th' subject. A good war ud knit th' country t'gether. It

ud clear th' foos eaut, an' ther' wants summat to do that.

Look at France, heaw prosperous that country's bin sin' they'rn

compelled to ate dogs an' cats' an' rottans. A war for me!"

Aw'd just getten th' words eaut when bang went a cannon ut

some childer had getten i'th' fowt, an' it had brasted, an'

splinters coome crashin' through th' window.

"Look at that, neaw!" aw sheauted. "Britons to arms!

Th' Rushians are here as sure as owt! Wheer's mi gun?

They're bombardin' th' fowt!"

Eaur Sal darted into th' buttery, an' hoo towd me to lock her

in. Aw met face th' army, but hoo wouldn't. Aw went an'

faced th' army, but it had retraced, an' laft its one gun brasted on

th' field. Aw couldno' ha' catcht that army if aw'd tried.

If aw'd collared a general aw should ha' bin satisfied, becose then

aw could ha' getten a war indemnity for mi brokken windows.

But aw believe still ut a bee-war would do us good.

――――♦――――

TH' OWD CHICKEN'S MAIN-BREW.

|

O, Willie brewed a peck o' maut,

And Rob and Allan came to pree;

Three blyther lads that lee lang night,

Ye wadna find in Christendie.—Burns. |

"WHAT'S

a peck o' drink among three on 'em?" said "Owd Chicken," when he and

his friends, "Charlie," and "Slivven," had finished the three-part

song. "Aw could ha' swallowed that misel' th' berm an' o."

"Aw should ha' thowt nowt at it if th' drink had bin

whiskey," said Charlie, taking a pull at a pint. "They must-no

be ale drinkers i' Scotland. It tak's up to' mich reawm after

they'n had a pokeful o' haggis."

"Aw conno' mak' eaut heaw a mon could tumble off his cheear

wi' four quart under his belt," said Slivven. "It met brast

him if he're a narrow wheelt un: but get him under th' table—nawe,

noather weight nor nowt else ud do it!"

The three were in the middle of a night's carouse. Owd

Chicken had brewed a peck apiece, and had toasted a dripper of

cheese and onions to "soak" with. They were getting mellow

under the influence of this concrete and the heat of a fire that

defied the storm that was howling outside the house, which stood on

the edge of a lonely moor. Owd Chicken's wife had retired to

rest, and, as the sons and daughters were married, the trio had the

house-place to themselves, save when a cricket put in its chirp to

give variety to the songs, which were not few, nor over musical.

If they did not give any name to their night's enjoyment, they meant

it to be rational, and such as might be expected where refined

pleasures were unknown. There would be no aching heads on the

morrow; no beating of wives, nor starving children; no street brawls

and their attendant brutality.

"Aw wonder what some folk'll do if Goverment shuts up drinkin'

shops?" Charlie remarked, consulting another pint which had been

fresh drawn.

"They'n have it o someheaw," said Slivven. "Aw never

knew a thing ut wur forbidden but what some folk ud ha' twice as

much on if they wanted it. Owd Eve ud never ha' yammered for

that apple if hoo hadno' bin towd hoo must-no touch it."

"It reminds me," said Chicken, "o'th' time aw're bringin' my

family up. They wanted some spring physic for t' clear the'r

blood, for they'd etten blackpuddin's till they'rn as measelt as a

curran' dumplin'. Well, aw thowt they should ha' some

brimstone an' traycle; but heaw to get 'em to tak' it aw didno'

know, for if we'd offered to give 'em kester-oil they'd ha' run out

o'th' heawse, an bin' seen no moore that day. Owd Jonty

happened to come in when i're mixin' th' stuff, an' aw axt him what

aw must do to get th' childer to tak' it.

"'Tell 'em they munno' have it,' he said, 'an' theau'll see

no moore on it! It's human natur.'

"That wur a wrinkle, aw thowt, an' one ut wur worth tryin.

So when aw'd done mixin' it, aw leet th' childer see me taste, an'

then aw purtended to hoide it, but took good care to let 'em see me

do it. Well, th' mornin' after, afore th' wife an' me geet up

aw could yer they summat unusual gooin' on; an' when aw went deawn

th' steers they'd o on 'em cleared eaut into th' fowt. Aw

looked for th' brimstone an' th' traycle dish. It wur as

cleean as if it had been weshed, an' carefully put back wheere aw'd

put it th' neet afore. Aw summoned th' skoo' up.

"'Which on yo' han done this?' aw said.

"One looked at another, but noane on 'em spoke, till eaur

Bill said—

"'It's happen rottans, feyther! Aw seed one this mornin'

pop deawn a hole, an' it wur painted green. Aw dar'say it 'ad

bin i'th' dish.'

"Aw didno' know whether t' laugh or grumble. But aw're

satisfied o' one thing, th' childer had etten it, an' that wur what

aw wanted."

More toasted cheese, eaten out of the dripper. To have

served it on plates would have robbed the feast of half its relish;

and as each man discarded the use of a fork, there was plenty of

elbow room at a table never intended for the accommodation of a

large supper party. The "shovelling" went on briskly; and was

for a time a good substitute for singing or conversation.

Having laid a solid foundation for whatever kind of structure it

might have to support, the party went on with their programme,

musical and otherwise, in rather an easy and indifferent manner.

"Aw wonder if th' quality ever getten ony o' this sort

stuff?" observed Slivven, going into corners with his knife, and

gleaning crisp bits of fugitive cheese, and delicious morsels of

onion.

"Dun they behanged as like!" said Charlie making a toothpick

of his pocket knife, and wiping it on a pair of corduroys.

"They getten a bit o' feesh ut's one hauve wayter, an' takken a

glass o' wine made o' alegar an' pepper, an' then they'n a shiver if

it's a cowd neet; after that they'n a taste o' thoose big red

ear-wigs, an' summat they co'en ice puddin' an' they getten so

starv't o'er th' meal, they wanten a bottle o' brandy for't warm

the'r insides. That's why so mony on 'em han red noses before

ripenin' time, an' chilblains on the'r feet, an' rheumatics i' the'r

marrow booans. If they knew th' vally ov a supper like this,

cheese ud rise i' th' market, an' onions be groon i'stid o' cabbitch."

"That 'ud be abeaut it," said owd Chicken. "But come,

lads, let's ha' another yeawl o' gradely owd fashunt singin'.

Charlie, theau uset to sing summat abeaut a so'dier dreeamin' he'd

gone whoam, an' seen his nanny-goats, an' thoose things they blown

like trumpets' same as Joe at top o' th' hill used to play—bugles;

an' reapers, an' chiller. Theau knows which aw meean.

That's a gradely owd sung, different to 'Come into the garden Maud,'

an' sich like balderdash as that."

"Theau meeans th' 'So'dier's Dreeam,' said Charlie, who was

stretching down his waistcoat as if preparing for a burst of

harmony.

"Aye, that's it, Charlie."

The singer did not hesitate, but throwing back his head, as

if contemplating the ceiling, sang—

|

Our bugles sang truce—for the night-cloud

had lower'd,

And the sentinel stars set their watch in the sky;

And thousands sank down on the ground overpower'd

The weary to sleep, and the wounded to die.

When reposing that night on my pallet of straw,

By the wolf-scaring faggot that guarded the slain;

At the dead of the night a sweet vision I saw,

And thrice e're the morning I dreamt it again.

Methought from the battlefield's dreadful array,

Far, far I had roamed on a desolate track;

'Twas Autumn—and sunshine arose on the way

To the home of my fathers, that welcomed me back.

I flew to the pleasant fields treasured so oft

In life's morning march, when my bosom was young

I heard my own mountain goats bleating aloft,

And knew the sweet strain that the corn-reapers sung

Then pledged me the wine-cup, and fondly I swore

From my home and my weeping friends never to part;

My little ones kiss'd me a thousand times o'er,

And my wife sobb'd aloud in her fulness of heart.

"Stay—stay with us!—rest!—thou art weary and worn!"

And fain was their war-broken soldier to stay;—

But sorrow returned with the dawning of morn,

And the voice in my dreaming ear melted away.

T. Campbell. |

"That's what aw co gradely singin'" said Slivven, when

Charlie had finished his song. "Ther's no sich singin' neaw-a-days—well,

not arming larn't folk. Ther'd be different dooin's if ther'

wur. Aw sometimes drop into a place when aw go to Manchester

wheere yeawlin's gooin'on o th' day o'er. An' sich sungs, an'

sich picthers upo' th' music papper yo' never seed. It looks

as if o th' crazy folk i' England had gone to Lunnon, an' fund a job

ut just suited 'em. That chap ut wrote 'Monte Carlo' 'll mak'

moore brass by that one sung nur ever Burns made in his life!"

"Aye, but theau mun recollect," said Charlie, "ut Burns hadno'

gone 'off it' when he wrote his sungs. We mun mak' some

alleawance for that. Happen if he' gone stark starin' mad he

met ha' written sungs ut even middle folk ud ha' sung, let alone th'

gentry. At present they sing'n nowt nobbut what foo's writen."

"It mak's my yead whizz reaund like a top," observed owd

Chicken, "when aw think o'er a sung one never yers sung eautside an

aleheause kitchen. If aw could yer sich sungs sung at skoos,

or concerts, aw'd never goo into a aleheause agen. Aw'd be

satisfied wi' a main brew."

"What sung art thinken on, Chicken?" asked Charlie.

"Aw've yerd thee sing it mony a time, Charlie, an' th' tears

han bin runnin' deawn us faces afore theau's finisht."

"Theau meeans 'Th' Braes o' Gleniffer,' said Charlie, who,

being pressed to favour the company with the song, began in a low

crooning voice.

|

Keen blaws the wind o'er the braes o'

Gleniffer,

The auld castle turrets are covered wi' snaw,

How changed frae the time when I met wi' my lover,

Amang the broom bushes by Stanley green shaw.

The wild flowers o' simmer were spread a' sae bonnie,

The mavis sang sweet frae the green birken tree;

But far to the camp they ha'e marched my dear Johnnie,

And now it is winter wi' nature and me.

Then ilk thing around us was blithesome and cheerie,

Then ilk thing around us was bonnie and braw;

Now naething is heard but the wind whistling drearie,

And naething is seen but the wide spreading snaw.

The trees are a' bare, and the birds mute and dowrie,

They shake the cauld draft frae their wings as they flea;

And chirp out their plaints, seeming waa for my Johnnie;

'Tis winter wi' them, and 'tis winter wi' me.

—Robert Tannahill. |

"Aw've yerd Tottie sing that i'th' 'Greyheaund' kitchen,"

said Chicken, "till every pipe's gone eaut, an' nob'dy seem't dry,

for they'dn forgetter t' sup. Talk abeaut eddication makkin'

folk betther! it may mak' 'em bigger hypocrites, an' sharper at

dooin' others! But that an' brass 'll knock o th' gradeliness

eaut on 'em."

"It's time we supped agen," said Slivven. "We hanno'

emptied one bottle eaut o' seven, an' it's gooin' on for twelve

o'clock. We'sn ha' to break into another week wi' it at this

speed."

"Well, whoa con drink, an' talk sensible talk?" said owd

Chicken. "Aw dunno' wonder ut Scotchmen havin' no time to do

it in. A hauve a peck ud ha' sarved us i'stead o' three peck.

If we'd bin talkin' abeaut dogs, or race hosses, an' some other

things o'th' same kither, we should ha' bin rowlin' upo' th' floor,

drunken bi neaw."

"If teetotallers ud reform us," remarked Charlie, "they

should tak' away th' desire for drunken company; an' th' cravin' for

maddenin' drink ud soon follow. Let 'em have a pint or two at

one another's heauses—whoam-brewed, no' strike-'em-blynt—an' we

shall ha' less occasion for policemen an' teetotal speauters.

Missions ud be brokken up, for they'd ha' nowt to taich us ut we

didno' know."

"It ud be th' greatest blow to carnal pleasure ut could be

struck," observed Slivven, "an' ud leead to betther things. We

need no' go through th' wo'ld wi' eaur een turned up, like a wench

when hoo's i' love, or a pa'son when he's turni' his sancity on for

a special buryin', but be merry, an' jolly, an' good-temper't, an

tolerant wi' one another; an' we should find that ut we'n bin

purtendin' t' seech ever sin society begun to wobble."

And they were merry and jolly until the clock struck one; an

owd Chicken said his wife must have been "tamperin' wi' th' owd

wag-by-th'-wo (clock), or it ud never ha' bin so late." They

had not heard the wind howling in the chimney, nor the occasional

rattling of hail against the window. It was summer time, and

gentle breezes with them. And as they had only emptied one bottle

out of seven, there was "Corn i' Agypt " for other times.

――――♦――――

TH' OWD BUTTERY DUR, OR AB'S AUDIT.

"THERE'S

a good deal o' bother i'th' country o' one sort or another," aw said

to eaur Sal one mornin' when th' newspapper had missed, an' aw felt

as if th' wo'ld had stopt.

"What about?" th' rib said, quite unconsarned. Hoo'd

just cleared th' table.

"About folk no bein' what they purtend to be," aw said.

"Is that summat new, or theau's nobbut just fund it eaut?"

an' hoo looked at me wi' sich a sly look ut aw suspected hoo'd an

idea o' what aw're droivin' at.

"Aw dunno' think it is new," aw said , "but they've getten a

new way o' findin' 'em eaut ut they hadno' used to have. Aw

con remember a time when th' peeace o' Hazlewo'th wur kept bi th'

hauve of a constable; an' he'd nowt to do! Neaw we'n six

policemen; an' it tak's 'em o the'r time to look after us."

"What dost meean bi a hauve ov a constable?" th' owd ticket

said, as if hoo're wonderin' heaw a mon could live if here cut i'

two.

"Well, he had to wayve to fill up his time," aw said.

"Sometimes he varied it by gooin' on th' fuddle for a week when ther

no signs o' ony law bein' wanted. That 'ud be after a pastime,

when th' brass wur done, an' they hadno' time to feight."

"What's made thee begin a-thinkin' abeaut that this mornin'?" hoo

wanted to know. "It isno' becose theau's seen owt i' th' papper."

"Nawe, but th' air seems full on it."

"Full o' what?"

"Well, aw conno' co it dishonesty; but they're fust cousins to one

another."

"Theau'rt talkin' strange talk, Ab."

"Ay, these are strange times when one doesno' know whoa to trust,

nor heaw soon they're gooin' to be takken in."

"Has theau bin takken in?"

"Well, aw're 'corner't' yesterday."

"What's bein' corner't?"

"Theau'd know it if theau wore breeches! Aw're passin' through th'

Market Place i' Manchester; an' when aw geet to th' 'Sponger's

corner' aw're tapped on th' shoother. 'Hello, old fellow,' a mon

said, 'are you in form this morning?' 'Well,' aw said, 'aw'm o reet,

if that's what yo' meean.' 'Can you do with your throat washing to

the

extent of twopennoth?' he said. 'Aw could struggle wi' it, if it

wouldno' go deawn beawt!' aw said. So we went into Fat Jack's i' th'

corner; an' he co'ed for two twopenno'ths wi' as mich swagger as if

here gooin' to get change for a suvverin. When th' glasses wur browt

in he begun o' fumblin' i' his pockets as if he didno' know they'd

nowt in; an' when he'd gone through 'em three or four times wi' th'

same result—balance nowt,—he said—I changed trousers this morning

and forgot to take my money out. Can you put down a shilling for me,

and I'll give you an I.O.U.?' 'Aw'll do that,' aw said; 'A've made

th' same mistake misel'. But aw'd moore nur one pair

at th' time. Never mind th' I.O.U. it'll nobbut be so mich lumber i'

mi pocket, for aw know it'll ne'er be redeemed.' 'Oh! things are

looking up,' he said, as he pocketed th' change. 'Ay,' aw thowt,

'they're lookin' up wi' thee; if theau con get on to another foo or

two; but they'n be lookin' deawn wi' me if aw meet wi' a lot moore

friends

ut wanten the'r throats weshin'! Aw know what theau'rt thinkin' neaw,

owd crayther!"

"Ut foos an the'r money are soon parted."

"That's just it. Aw didno' like th' looks o' th' mon. If the'r shirt

collar's frayed, an' the'r hat blackleeaded, they're signs ut ther

no assets. Aw've seen him i' th' same treausers till they're welly

ready for droppin' off, poor felly! Aw darsay he'd like to change 'em."

"But theau's a furr meeanin' i' what theau's just said," th' owd

stockin'-mender hinted. "What is it?"

"Well, neaw aw'll come to it," aw said. "For a start—we're livin'

to' fast. Folk mun be big, chus what else. We dunno' seem to care

neaw whoa's money it is we spend. It mun goo if we han it. Aw

believe some folk dunno' know th' difference. Look what a row ther'

is gooin' on i' Manchester; an' heaw they're co'in one another i'th'

newspappers. Not becose some han done owt wrong, but becose they'n

bin fund eaut. Thoose ut hanno' bin fund eaut are crowin' o'er

t'others like a cock wi' its Sunday clooas on. Happen these are nobbut waitin' the'r turns. Aw feel misel' sometimes as if aw'd done

summat dishonest; an' if onybody wur to meet me, an' stare at

me, as if they knew summat, an' say 'Ab, theau's made a bonny mess

on't'! aw should feel guilty. Aw sometimes think aw want a safeguard

t' prevent me gooin' into someb'dy's pockets. Aw think a pair o' boxin' glooves ud be as good as owt, if they didno' look clumsy."

"Theau's no' said o ut theau meeans yet." Th' owd gel has a deep

inseet i' human natur', speshly a mon's. Hoo con read thowts, aw

believe, as weel as a mountebank, an' could find a pin if it wur hid

i'th' hesshole.

"Well, hardly," aw said; "but aw'm comin' to it. Theau sees it

doesno' matter what position a mon's in, if he has to hondle brass,

he's sure to want some on't. His honesty's i' danger th' fuss

minute,—in as great danger as if he'd a lot o' moral leetenin' flyin'

abeaut his yead. He sees th' brass lyin' theere, an' begins a-gooin'

reaund it like a buzzert at a candle, till he's drawn into th'

blaze. Then it's wo-up wi' him! He thinks, as he's tasted blood, he

met as weel have a sheep as a lamb; so th' next thing we yer on him

he's missin'. It does seem strange ut betther eddicated they are an'

wur they are to find eaut. Aw should be nobbled afore aw'd

pocketed sixpence."

"Aye, it's a good job theau's no larnin', Ab," th' owd ticket said. "Ther's no tellin' what soart of a hobble theau'd ha' getten thisel'

into, ift' had larn't to cypher like owd Juddie. As it is neaw, aw

con trust thee, for theau'll never be owt nobbut a foo."

"Thank thee," aw said; "but aw'm noane feeshin' for compliments. Ther's to' mony con be had beaut—o'th' soart. But look at eaur club

clark at th' 'Owd Bell.' Aw've thowt it strange a good while ut he

could do as he does,—flyin' abeaut, an' drinkin'. No wayver con do

it. Well, he's bin fund eaut at last. We'n had a mon lookin'

through th' books; an' he's dropt on to him. He's bin dooin' a bit

i'th' undertaken' line,—quite of a new soart."

"What, buryin' folk i' second hond coffins, an' chargin' em' for new

uns, like that undertakker ut buried owd Schofilt up at th' Knowe?"

"No' quite; he's bin buryin' 'em afore they're deead!" aw said, "We didno' know but what Shoiney Jim wur nicely bedded i'th' gravel,

till one day he turned up at th' 'Owd Bell,' an' swore he wurno'

deead, an' ud prove it if onybody ud goo i'th' fowt wi' him. That wur th' cause o' these things bein' fund eaut."

"Well, but he hasno' bin put i' prison for it," th' owd un said, "heaws that, like?"

"It's th' queerness o'th' law," aw said. "They couldno' find him

guilty o' roguery. He're howdin' th' money i' trust till Shoiney Jim

wur deead. So he're nobbut guilty o' thingumy. If it could be proved ut he didno' know but what Jim were deead, it would ha' been

hanky-panky; an' his charikter would ha' been clear. As things are ther's

a blot on it; but that'll wesh eaut i' time."

"Eh, yo' men, yo' dun mak' some strange laws!"

"Well, if they're made plain an' straight-forrad, we should ha' no 'casion

for lawyers. They'd be thrown on th' parish; so we should should ha'

to keep 'em some road."

"If women had th' makkin' o'th' laws—" an' here th' owd rib looked

like owd Moses—"they'd mak' 'em so as folk wouldno' want tryin'. If

they'rn guilty they'd ha' to be punished. They'd ha' no holes to

creep eaut on. No hanky-panky, nor thingumy. But yo' men never dun

nowt gradely. But what's this bother abeaut i' Manchester?"

"Well there's a lot o' men bin fund eaut to be guilty o' summat. They conno' co it dishonesty; but whether it's thingumy or

hanky-panky, or legally takkin' things as the'r own, hasno' bin

proved yet. But aw dunno' think onybody'll get i' prison through

it."

"Then it seems they con do a great deeol o' wrung, uts reet i' law."

"But these chaps hanno' bin dooin' so very mich wrung o' the'rsel's. Its nobbut their stomachs ut han bin puttin' things eaut o' seet ut

they shouldno' ha' done; atin', an' drinkin', an' smookin', at th'

expense o'th' ratepayers. That's what they'n bin dooin'."

"What, an' getten two pound for every time meeten? Ailse o' Jackey's

says they'n sometimes as mony as forty meetin's in a week. Look at

that neaw! Conno' they afford 'lowance eaut o' that.

"They'n nowt o' th' sooart as two peaund a meetin'. They ha' not a

penny fro' year's end to year's end."

"Han they nowt nobbut what they con ate an' drink?"

"Nawe; an' some are so thin they could go up a stovepipe."

"Well, they shouldno' begrudge 'em o' that. What is two-penn'oth o'

bread an' cheese an' a pint o' ale? or for th' matter o' that, what

'ud a blow-eaut o' pottito-pie be? It wouldno' mak' th' rates mich

bigger."

"Theau'rt reet; it wouldno'—not above a farthin' i' th' peaund. But

when twenty-one dinners costs above fifty peaund, thoose ut conno'

be in at sich like feeding find faut becose they hanno' the'r

share."

"Twenty-one dinners costin' above fifty peaund? Wheay that 'ud be

above two peaunds a dinner!"

"Aye, if it wur weel reckon't up."

"An' what could they ate to cost that? Gowd?"

"It isno' th' atin' exactly; it's th' weshin' deawn."

"Well, an' whatever sooart o' tubs con they have for t' howd o that? If they had it i' sixpenny it 'ud fill a rain-tub. Ther's nob'dy

could get up a stove-pipe wi' o that under the'r senglets."

"Nawe, nor th' chimdy of a steeam ship."

"Well, neaw, let's see what it 'ud cost twenty-one o' sich like as

thee an' me for a dinner, an' theau's a good twist, Abram. Let it be

a good dinner. Th' best ut con be made. Or i'stid o' twenty-one

let's say thee an' me an' eaur lads—five, an' they con side a lot. Two peaund o' neck o' mutton at eightpence, that's sixteenpence.

Four peaund o' pottitoes, threehaupence, that's

seventeenpence-haupenny. Two peaund o' fleaur, say fourpence; tho'

it 'ud hardly come to that."

"Co it thrippence-haupenny, then."

"Well, we'n say thrippence-haupenny. That brings it up to one-an'-ninepence. That's th' whul cost of as good a dinner as need be set afore a

king."

"Theau hasno' reckoned th' foire."

"Nawe, becose we should ha' a foire if they no cookin'."

"Nor th'

wesh-deawn!"

"Well a quart o' thripenny 'ud just bring it up to two shillin'; an'

theau wouldno' want nowt betther nur that. O th' whul lot, theau

sees, doesno' ameaunt to fippence a yead."

This statement caused me to put mi studyin' cap on an' aw begun a

wonderin' heaw it wur ut wi' atin' stuff so chep as it wur never

known to be afore, th' same income wouldno' do. Everybody wur crying

eaut ut things wur never so bad. Heaw is it? Aw put th' question to

th' owd chancellor o' th' exchequer, an' geet this onswer.

"Folk wanten moore neaw-a-days nur they'n used to do. They'd ha' bin

content at one time wi' a walk thro' th' fields of a summer neet. Neaw they mun ha' a droive somewheere, an' co at a public-heause. Women con droive neaw, an' they're gooin' to droive us to——!"

"Aw know wheere theau meeans,—but aw thowt i' some things women

could do betther nur men."

"Not i' everythin'. Aw like a woman havin' her own place—lookin'

after her husband's brass, an' keepin' him straight, an' goodness

knows they wanten lookin' after."

"That may be; but theau hasno' onswert my question. Heaw is it ut wi'

mayte chepper, it costs us moore to live?"

"Aw're comin' to that, if theau hadno' stopt me. We'rn satisfied at

one time wi' ale. Neaw its gin, or whisky, or brandy, an' they

keepen it i' th' heause, too. Jack o' Flunter's wife an' me used to

ha' a gill o' fourpenny between us; an' that wur of a weshin' day. Neaw they goo to th' Owd Bell' of a Monday, an' theau'd think ut

ther'

wurno' a clock i' th' neighbourhood."

"Why?"

"Ther' so mony women come a-seein' what time it is!"

"An' what by that?"

"They didno' think it wur so late. They'd laft th' dinner part

cooked; an' they'd get turned eaut o'th dur if it wurno' ready at th'

time. But they'n time to have the'r three or four twopennoths, an'

getten as noisy as a skoo."

"But it doesno' o goo i' drink," aw said.

"Then it goes i' heause things, an' clooas. Wheere could theau ha'

yerd a payanno forty year sin'?"

"Nowheere."

"Neaw they're i' every heause. Wheere could theau ha' seen a lad wi'

a watch? Nowheere. Wheere could theau ha' seen a wench wi' a bonnet

on of a Sunday? Nowheere. Printed napkins on the'r yeads, an'

bedgeawns on the'r backs, an' abeaut hauve clemmed t' deeath wi'

thoose. Neaw theau couldno' tell 'em fro' ladies, unless

it wur by the'r tongues."

"But we'n noather wenches nur lads awhoam," aw said. "An' when we'rn bringin' a family up we could save summat. Neaw we'n moore

comin' in, an' con save nowt. Heaw is it?

"Dost' want to know?"

"Aye, an aw meean to know! Aw'll audit thee! If a Teawn Council con

do wrung, other folk con do wrung. It's nobbut a question of a

bigger family. They'n bin o'erhaul't i' Manchester, an' neaw aw'm

gooin' to o'er-haul thee. Aw want to know th' partikilars o' what

theau spends; an' if they are no' satisfactory eaut theau go's!"

"Will theau vote me eaut, Abram?"

"Nawe, but —"

"Aye, wilta? Theau's forgetten aw've bowt a new rowlin' pin! Sing smo' my lad, an' aw'll

show thee heaw th' money goes. Fotch th'

buttery dur."

"What mun aw fotch th' buttery dur for?"

"Everythin's chalked on theere, even to a pennorth o' sond. Fotch

it!"

Wi' that aw went an' lifted th' owd splicin' o' booards off th'

angles, an' fund it wur chalked o'er wi' a lot o' things aw could

mak' nowt on. Like shopkeepers used to do shop scores afore figures coome i'th' fashin. Aw reared it up agen th' table, an' started th'

AUDIT.

Aw're never betther puzzled i' mi life nur when aw looked o'er this

wooden shop-book, an' tried to mak' eaut th' meeanin' o'th' figures

ut wur on it. Aw knew ut a o meant a shillin', an' a hauve-moon

six-pence. Aw knew, too, ut a lung choak stood for a penny, an' a

short un for a haupenny; an' ut an x wur a farthin'. Aw could add up

th' whul lot, an' knew heaw mich it coome to. But what had th' brass

bin spent on? Theere wur th' rub! Aw should ha' to co' in mi client

to explain.

"What does this fust row o' figures meean?" aw axt eaur Sal as hoo

stood grinnin' at me.

"Theau mun find it eaut, Abram," hoo said.

"But heaw con aw find it eaut,?" aw said. "It met meean one thing,

an' it met meean another. Th' figures 'll stond as weel for atin' as

drinkin' stuff."

"Aye, it seems theau knows they're a bit mixed up," th' owd ticket

said. "Ther's booath sorts theere. But neaw aw see theau'rt fast,

aw'll just lo'sen thi. Thoose fust lot are for fleaur, an' sugar,

an' butther. But whether part on't is for sooap, or candles, aw'm

no' sure. It's th' one or t'other. Theau'll find ther's two an'

thrippence for

beef an' a bit o' suet, as theau goes on."

"An' what's this farthin' for?"

"A knot o' oosted (worsted) for t' mend thi stockin's wi'. Oh, an'

thers six-pence for tae theere. Aw couldno' mak' it eaut till neaw. An' ther's two three an' sixpences for whiskey ut thee an' Jack o'

Flunters an' Billy Softly had that neet ut Billy tumbled into th'

mop hole."

"Let's see,—when wur that?" aw said.

"Wheay, has theau forgetten, when its nobbut a week sin'? it shows

heaw theau wur! Billy's had a sore throat ever sin'."

Seven-an'-sixpence for a neet's fuddle! Aw felt in a good mind to gi'

th' job up. This made me sweeat when aw thowt abeaut it. We'd

drunken what would ha' bowt three-an'-a-hauve dozen o' fleaur i'

one neet! A gradely bakin',—sich a one as forty year sin' ud ha'

caused th' childer to ha' fits. A big mug full o' mowffins an'

loaves;

an' o gone deawn eaur throttles i' one sittin'-down!

"Aw'll ha' a pipe o' 'bacco, aw think, afore aw goo ony fury," aw

said, "aw'm gettin' rayther muddled i' mi totals."

"What, has that whiskey choked thi?" th' owd un said.

"Well, aw mun say aw'm a bit flummaxed," aw said. "Aw didno' think

we'd had so mich."

"Nawe, yo' conno' measur' yo'r throats when yo' ha' no' fort' keep

throwin' brass on'th table! If Billy Softly mun ha' paid for his own

he wouldno' ha' tumbled into th' mop-hole. His wife sticks to it at

some on yo' pushed him in. But aw know he went eaut bi hissel'. Seven-an'-sixpence! what 'ud ha' bowt me a new pair o' boots for th'

winter, gone deawn yo'r throats i' one spree! Aw'll leeave thee t'

think abeaut it a bit an' see if it'll taich thee ony sense." An' th'

owd Rib dashed into th' lum (loom) heawse wheere hoo made a cat jump

through th' window, while aw had mi pipe. Another eighteen-pence

gone, aw thowt; but aw durstno' say nowt.

When aw'd getten mi pipe fairly lit, an' one leg thrown o'er th'

other, aw begun o' philosophisin'. Th' buttery-dur, as seen through

th' reech ut curled abeaut it, took a shape aw hadno' calkilated on. Th' figures on it seemed to multiply to an extent 'at soon covered

th' dur o'er wi' shop scores; an' when they'd filled it, th'

dur begun o' multiplyin' like a pack o' cards, till they seemed as

if they'rn showin' me th' shop-scores of a lifetime; an' i' everyone

o these, seven-an'-sixpences kept bein' repeated till—aw went o'er

to sleep as if it had bin neet-time.

A very little sends me to sleep neaw. Aw con goo o'er onytime if th'

owd Rib's ticklin' mi ear wi' one ov her sarmons. A nod's very

convenient betimes. I' this short sleep aw reviewed th' wo'ld as it

is, or as it's made to be. Aw seed a grand procession passin' before

me; an' every one i' that procession carried a lot o' books ut had

to be audited; an' ther hunderts watchin' wi' faces white an' tinged

wi' blue. These wur feart o' bein' fund eaut, aw reckon. I'th' front

o' me wur a grand place abeaut twenty times bigger nur Manchester

Teawn Hall; an th' procession wur movin' to'ard it. I'th' fust rank

wur carried a nation's books; an' these had to be overhauled for

o' ages back. Kings, an' shadows o kings; statesmen an' shadows o'

statesmen, stood by, tremblin' wi' fear. They'd never bin audited

before; so never had bin fund eaut. Mixed amung these wur a lot o'

women; some on the'r knees, prayin' ut certain items wouldno' be

seen, or ut leeaves wheere they'rn entered met be torn eaut.

They'd bags o' gowd i' the'r honds, for a purpose ut 'll be seen

afore lung. These wur feart o' bein' fund eaut. After these coome

corporations wi' the'r books; an' they'rn fratchin', an' co'in one

another o th' time they'rn on th' road. They'd everyone bin angels

up to this day o' audit; an' they'rn feart they'd ha' to lose the'r

wings. They'd

noane on 'em ever had owt, but they kept sayin—"Theau's had moore

nur me!" So it wur a general case o' pon an' kettle.

Th' next ut coome past wur a smart lot. The'r books wur o'

gilt-edged, an' as straight, they wur, as if they'd never bin

touched. Nob'dy had ever audited these; an' th' idea ut sich a thing

ud ever enter onybod'y yead wur past belief. Everyone o' these wore

a white choker, an' looked far, far above suspicion. But a cleaud

crept o'er

th' sun while they'rn gooin' past, an' some o'th' by-stonders seemed

to think it ud goo hard wi' 'em. These wur followed by a noisier

gang 'at had no books. They'd no 'casion for ony. O th' brass they

collected went to one mon; an' he spent it as he liked! They'rn led

up by a band ut made as mich noise as fifty gradely players ud

ha' done, though they'rn nobbut five. But ther tamborines, an' 'cordions,

an' tin whistles to help. A lot beheend wur singin' "Wait till the

clouds roll by," an' just then th' owd sun showed hissel. But he

looked as if he're blushin' for summat. Ther a lung pause after

these had gone, ut made a big gap. But th' eautsiders did no' close

in, so ther' must be someb'dy else comin'. A sheaut coome ripplin'

up, ut geet into a roar at last: an' aw begun o' wonderin' what wur

comin' next. Aw didno' wonder lung, for, marchin' as if o th' road

belunged to her, wur eaur Sal, wi' th' buttery dur. Just then ther a

bang as leaud as if th' oon had tumbled on th' fender, an' aw

started wakken! Th' owd Rib had knocked th' buttery dur deawn, an'

hoo wanted to know if aw knew which end o'th' day it wur.

"It looks like mornin', but it feels like neet," aw said, hardly

knowin' what it wur, as aw felt a bit dazed.

"Art' for havin' thi dinner neaw, or theau'rt for finishin' th'

auditin' th' fust?" hoo wanted to know.

"Wheay, is it dinner-time?" aw said. An' aw felt at my waistco't.

"It doesno' feel above eleven o'clock wi' me yet." An' it didno',

noather.

"If it tak's thee hauve a day to go through a quarter of a dur

theau'll be clemmed to deeath afore theau's th' job finish't. So theau'd betther get thy dinner whether theau'rt hungry or not." Th'

owd crayther wur reet.

Well, aw picked up this wooden shopbook, an' reared it at th' yead

o'th' heause, wishin' at th' same time aw'd never tackled it, an'

sit deawn to mi dinner. Aw felt a little bit shawmed at what aw'd

done, an' could hardly look eaur Sal i'th' face. It wur a very quiet

dinner-time. Not a word wur spokken o' noather side; an' aw felt

fain

when it wur o'er, not becose aw wanted to get to mi job agen, but

someheaw aw couldno' help feelin' as if th' owd Rib wur auditin' me. Heaw would it be if aw gan it up? Aw'd see what th' owd lass said.

"Aw think aw'd betther be same as they are at eaur club, after th' 'lowance

o' whisky has bin drunken;" aw said.

"Heaw's that?"

"Write across th' bottom,—'audited, and found correct,' when they

ha' no' gone th' hauve way through."

"Nay, theau's started it, an' theau'll ha' to finish it, if it tak's

thee o day. So get agate."

Aw geet agate.

"What's this lot for?"

"Coal."

"They're a good deeal chepper nur they used to be if a looad nobbut

comes to that."

"That's noane a hoss looad, nor a donkey looad. Aw had to get 'em

when Jim Thuston's hoss wur ill. They're three bags aw had off owd

Neplin."

"Oh! Does this sixpence belung to it?"

"Nawe, that goes wi' th' next."

"What is th' next."

"Th' milk score."

"We'n nobbut had porritch twice this last fortnit. Heaw's that?"

"They conno' use milk for nowt nobbut porritch, aw reckon?"

"Yigh, feedin'-bottles. But theau's gan o'er usin' thoose. Well,

it's hardly wo'th botherin' abeaut. Aw dunno' think theau's thrown

it to th' pig. What's th' next for?"

"Traycle an' blackin'."

"Theau's oather had a good deeal o' one, or a good deeal o' t'other. Hast bin takkin' shoon in for polishin'?"

"Ther's nobbut a penny deawn for blackin'; t'other's for traycle."

"Aw've seen no traycle."

"Theau's seen towffy, an' tharcake; an' they conno' mak' thoose

beawt traycle."

"Reet, owd lass! we're gettin' on famously."

"Ther's moore things wanted abeaut a heause nur some o' yo' chaps

thinken ther' is. Neaw, theau conno' gex what th' next is for."

"Nawe, but aw con see ther's a farthin' to it."

"Nay, that farthin' doesno' belung to it."

"Well, aw'll gi'e it up. What's it for?"

"Castor oil for th' pig."

"Wheay, has t' bin givin' th' pig castor oil?"

"Aye, an' its done it a rare lot o' good, too. Look heaw it's come'n on this last week."

"But it'll taste th' bacon. Whoa ever knew a pig tak' castor oil

afore? Theau'll be givin' it pills next."

"Aw would if aw thowt they'd do it good. Theau conno' tell what th'

next is for."

"Happen it's for physic for th' hens."

"Nay, its for turpytine an' beeswax fort' polish thi wits up a bit. Aw've a good mind to gi'e thee a dose neaw. Theau'd look breeter for

it."

"Goo up one, as they say'n at th' skoo. We're gettin' very nee th'

fur end neaw. Will these next figures be one item; or are they

divided?"

"Mop-rags, an' a new nail; a penno'th o' sond; an' packet o' black-leed."

"Heaw mich wilt put deawn for th' cat gooin' through th' window? Eighteenpence?"

"Eighteen fiddlesticks! Moore like eightpence. Aw'll kill it if it

comes agen. It took a nice bit o' steak last week ut aw'd intended

for a puddin'; an' mony a thing it's ta'en afore. Neaw as theau's

finished thi auditin', put th' dur i' its place, an' then ――

"Then what?"

"Aw'll audit thee!"

Aw hung th' wooden ledger on its angles agen; an' prepared mi books

for examination.

"Neaw, wheere wur theau o' Monday neet?" th' owd ticket begun, as

soon as aw'd getten i' mi cheear.

"At th' 'Owd Bell,'" aw said.

"Aw reckon theau'd nobbut a pint o' fourpenny!"

"Yigh! two."

"An' theau sit wi' two pints fro' seven o'clock till eleven, didta?

Had t' no' three glasses o' whisky beside?"

"Whoa's towd thee?"

"Aw yerd thee co for 'em."

"Wheay, wur theau theere?"

"Nawe; but aw reckon they set thee agate o' dreeamin' when theau

coome whoam, an' theau said 'just another,' three times o'er. Th'

last theau'd ha' warm, theau said. Abram, if ever theau commits

murder theau'll tell i' thi sleep!"

"Well, theau sees, aw conno' chet thee."

"Aw dunno' know that. Theau'd moore nur three glasses."

"Heaw dost' know?"

"Well, theau'd eighteen-pence when theau went eaut; an' o' Tuesday

mornin' theau couldno' pay th' chip lad for a pennorth o' chips."

That wur auditin' wi' a vengeance, aw thowt!

"Theau went a bearin'-whoam o' Wednesday. Heaw mony places didt' co

at comin' back?" th' owd calkilater went on.

"Aw coome o'th' tram back," aw said.

"What, to th' fowt gate? aw didno' know ut th' rails wur laid to

eaur dur,"

"Aw'd just a warm pint at th' 'Owd Bell,' that wur o."

"An' that

cost thee a shillin', did it?"

"Well, that an' mi tram fare, an'—"

"Three two-penno'ths i'th' teawn afore theau started."

"Heaw dost' know?"

"Becose it just comes to a shillin'. That's a hauve a crown up to

Wednesday,—an sober too! What would it cost thee o' Setterday neet,

when theau're feelin' o'th' wrung side o' th' gate for th' latch?"

Aw couldno' say nowt to that; an' when hoo seed aw're fast, hoo

begun her lecture.

"Abram, thy drink costs thee as mich as ud keep th' heawse on. That's th' reason ut livin' costs moore neaw nur it did when we'd

eaur lads awhoam. A pint o' fourpenny ov a neet ud ha' satisfied

thee then, wi' a bit ov a break eaut at a wakes. An' theau'd used to

walk to th' teawn an' back. Neaw it's tram theere, an' tram back;

an' sittin' like a lord at th' 'Owd Bell,' wi' a cigar i' thi meauth,

if onybody's one to gi'e thee,—an' a glass o' whiskey under thi

nose. Eh, aw wish theau could see thi picture when theau's had

abeaut three, theau'd—." Th' next minute aw're i'th fowt! Aw couldno'

stond bein' audited no lunger.

――――♦――――

"THAT CRAB."

WE'RE

gettin' within smellin' distance o' Kesmas," Dan-o'-Meaudy's said to

me t'other neet, as we're drawin' a whiff or two o' "Cope's Mixture"

up two lung white chimdys. "Th' childer i' eaur lone han begun a-singin'

'Christians awake' o ready.

"Aye, thoose ut con afford one 'll ha' to be lookin' the'r goose or

the'r turkey eaut e'enneaw, if they meean buyin' a wick un," aw

said; "but aw think eaur folk 'll ha' to be satisfied wi' an owd hen

agen, if ther's to be ony change i'th' diet."

"Did aw ever tell thee, Ab," said Dan, laafin', "abeaut that crab

aw bowt last Kesmas?"

"Nawe," aw said, "theau'rt abeaut th' last mon aw know ut ud

spekilate i' sich grand feedin' as that. Theau'll be buyin' a turtle

this Kesmas, aw reckon. Heaw is it theau's never tow'd abeaut it? "

"Aw're feart on it gettin' into that Journal theau sends so mich o'

thi crazy bother to, or else aw'd ha' tow'd thee lung sin'; " an'

Dan looked as if he couldno' keep it to hissel' another minute.

"Well, heaw wur it, like? Theau'rt safe enoogh neaw," aw said. "It shanno' goo i'th' Journal."

"An theau'll no' tell Jerry Lichenmoss abeaut it?"

"Not a cheep."

"Nor thi wife?"

"Well, aw met as well give it th' bellman as tell her.

Aw think theau'rt middlin' safe i' my honds if theau'll goo on wi'

thi tale."

"Aw dar'say theau'll think aw'm lyin', but it's Gor'struth

for o that! It happened this road. Eaur Nan had slat it i' mi face

mony a time ut aw never browt her a bit of a nifle (delicacy) no

time when aw went to Manchester; so aw thowt for once aw'd sattle

her bother—aw'd bring her summat th' next time aw went. This happen't abeaut a week afore Kesmas Day."

"Aw'd gone to Manchester a-buntin'; an' aw'd like a dacent soart of

a draw—seventeen an' sixpence, aw think it wur, an' two shillin' t'

pay eaut for windin'; that ud mak' it fifteen an' sixpence. Wi' so

mich brass i' mi pocket aw thowt aw could do summat grand, an'

surprise everybody i' Frog-lone wi' th' smell ther'd be o Kesmas

Day. Aw couldno' purtend to waste mi e'eseet upo' nowt less nur a

turkey. So aw left mi wallet at Tom Wood's, on' strowled across th'

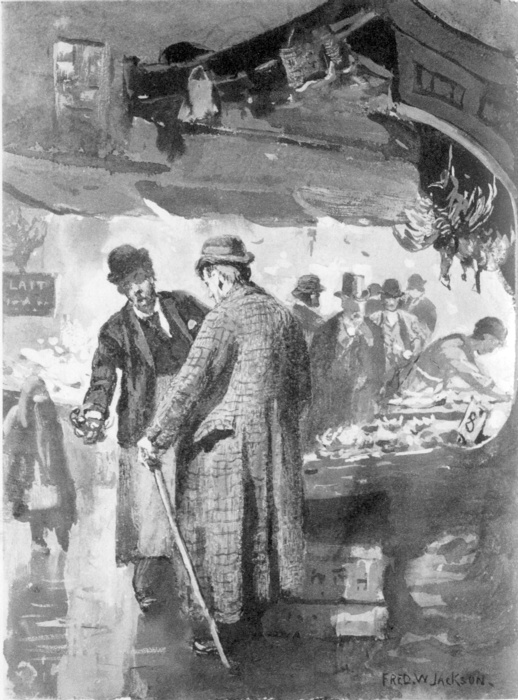

market for t' see if aw could leet o' owt ut ud fit mi pocket. While aw're starin' abeaut amung th' oranges an' th' apples, aw met

Siah-at-owd-Bob's wi' booath arms full o' stuff for th' childer.

"'What art dooin' here, Dan?' he said. 'Art' gooin' t' begin o'

shoppin', as theau'rt marketin'?'

"'Nawe; lookin' eaut for a turkey,' aw said.

"'Theau mun be a goose then, if theau'rt lookin' for a turkey among

orange boxes an' apple tubs,' Siah said an' set up a crack o' laafin'.

"'Well, aw thowt aw could get owt aw wanted here,' aw said. 'That

shows aw'm no' used to buyin' owt o' th' sooart.'

"'If theau wants a bit o' gradely stuff thee goo deawn to Muirhead's

i' Victoria Street," Siah said. "Dunno' thee buy common stuff! Aw

know theau'rt able t' pay for it. An' goo deawn soon afore th'

prices begin a-gooin' up."

"Aw took Siah's advice, an' darted off deawn Shudehill, just co'in'

at Sammy-o'-Moses's for a basin o' stew for t' keep th' cowd eaut;

then aw crossed th' Doytch, an' passed th' gates o' th' owd

slowter-heause, wheere aw're wed. Aw fund Muirhead's shop, but aw're

a good while afore aw du'st ventur' in. Beside, it wur so creawded

wi' carriage folk. Ther an owd grey-e'ed dog lookin' reaund abeaut

th' front; aw reckon for t' see ut nob'dy took nowt, nobbut what

they paid for. This dog eyed me o'er above a bit. Aw dar'say it

thowt aw wurno' a regilar customer, but one of a sooart ut 'ud want

watchin'. At last aw ventur't into th' shop an' th' dog followed me.

"'What can I serve you with?' a very nice sort of mon said, comin'

to'ard me, an' wipin' his honds on his blue appron.

"'Well, aw're thinkin' abeaut a turkey,' aw said.

"' Large or small?' th' mon said.

"'Look at me, an' judge for yo'rsel'!' aw said.

"He laafed; an' then he raiched summat wi' a neck as lung as mi arm,

an' a barrowful of a carcase at th' end on't.

"'This will be about your size,' he said; an' he flopped th' brid

deawn on a trest.

"'What weight abeaut will it be?' aw axt him.

"'About sixteen pounds,' he said.

"'That'll just be two dinners,' aw said. 'What's th' price?'

"'You can have it for a shilling now,' he said; 'but you couldn't

get it in the afternoon for less than eighteen-pence.'

"'An' chep enoogh, too!' aw said. Aw never thowt aw could ha' bowt a

turkey for a shillin'. This bein' co'ed a top shop, aw thowt it 'ud

ha' cost moore nur that.

"'Where shall I send it to?' th' mon said; an' he began a-preparin'

for lappin' it up.

"'Oh! aw con carry it misel'; aw'm noane a preaud chap,' aw said;

an' aw threw deawn a shillin' upo' th' trest.

"Th' mon stared at me; an' then a grin begun a-creepin' o'er his

face.

"'I'm afraid you're not in the habit of buying turkeys,' he said, as

soon as he could get his face straight.

"'Aw'm not,' aw said; 'but aw dunno' meean this to be th' last. Aw didno' think turkeys wur so chep!'

"'When I said a shilling, I meant a shilling a pound,' he said; an'

he fairly broke deawn.

"Aw seed a clear road eaut o'th' shop; an' as th' dog wur laafin' as

heartily as th' mon, aw spied mi opportunity, an' shot into th'

street, wi a pair o' ears ut would ha' bin dangerous at th' side o'

a peawder magazine.

"Buy a crab, sir?—Quite fresh, sir!"

"Aw didno' stop till aw geet past wheere th' last carriage

stood; then aw browt misel' up, an' looked to see if th' dog wur after me. Seein' ut aw're clear o'th' shop, aw muttered a blessin' for

Siah-at-owd-Bob's, an' then turned into a narrow street, wheere ther

oysters, an' o sorts o' feesh lyin' abeaut. Aw stopped facin' a tub

ut steeam wur comin' eaut on; an' ther' a lot o' queer things in it,

wi moore arms an' legs nur we han; an' aw're puzzlet to find eaut

wheere th' meauth wur, or whether they had one or not. Seein' me i'

mi deep studies o' nattural history, a mon said—

"'Buy a crab, sir?—Quite fresh, sir!' an' he oppent th' lid o' one

for t' show me th' inside.

As lots o' folk wur buyin' these crabs, eaut o' other tubs, aw thowt

they must be a Kesmas nifle, so aw'd spekilate, but ud tak' care not

to go to' far."

"'Heaw mich a peaund?" aw axt him.

"He gan me a queer look; then he said—'We don't sell them in pounds. We can't sell less than the whole fish. Take this for eight-pence.'

"'Eight-pence for th' whul lot?' aw said.

"'To be sure!' he said.

"'Th' box it's in too?' aw said,

"'You don't suppose I'd sell it without the shell,' he said an' he

looked as if he thowt aw're havin' him on th' stick.

"'O reet!' aw said. 'If eightpence is o ut aw ha' to pay aw'll buy

it. But aw thowt they sowd everythin' by weight abeaut here.'

"'Not shell fish,' he said; an' he pappered th' crab up an' honded

it to me. Aw gan him mi eightpence, an' fund he're satisfied; an' as

soon as he fingered th' brass, he sung eaut―

"'Sold again to a bloomin' swell! Here you are, ladies an' gent'men,

take 'em at your own price.'

"As it wur a cowd day, aw'd that lung top-cooat on ut wur mi

gronfeyther's, an' one o'th' pockets, aw fund, ud just howd th'

crab. So aw dropt him in, wheere he'd be safe to get whoam, as aw

shouldno' leeave it nowheere.

Then aw strode off to Tom Wood's for mi wallet, an' just a warm un

for t' face th' wynt with. Aw sit as nee th' foire as aw could get;

an' when th' top-cooat geet warm, ther some chaps stood at th' bar

ut begun a-sniftin' an' lookin' reaund, an' one on 'em says to me--

"'Aw think yo'n browt yo'r barrow inside, mesther! Heaw are yo'

sellin' 'em?'

"'Sellin' what?' aw axt him.

"'Wheay, yo'r cockles!' he said.

"'Aw'm sellin' no cockles, not I!' aw said.

"'Then yo'n bin wheere they are,' he said; 'an' they're no' sich

fresh uns, noather.'

"'Aw've seen no cockles this day,' aw said.

"'Well, what con it be?' he said; an' he snifted an' looked reaund

agen. Just then he seed a little dog huntin' abeaut, as if it wur

lookin' for its mesther. 'Oh, it's thee, is it?' th' mon said, an'

th' poor innocent bow-wow geet lifted into th' lobby wi' his foout.

"For fear aw met be sarved th' same, aw shoothered mi wallet an'

crept eaut. Aw'd intended ridin' whoam, but for fear ther' met be a

row on th' 'bus, if someb'dy smelt mi sae-turkey, an' aw met get

tumbl't off, aw set eaut a-walkin', thinkin' aw'd spend mi

threepence at three co'in shops on th' road. Aw geet as far as th'

Plattin' afore aw co'ed onywheere; then aw tumbl't into th' owd 'Catherina,' wheere aw thowt it ud be too soon for ony company, an'

aw could get away as soon as aw'd supt up. But aw fund five or six

chaps theere as merry as if it wur ten o'clock at neet, an' mi

wallet slipt off mi shoother quite nattural. Aw're very soon as

merry as they wur. Well, pints after pints kept comin' in, till aw

geet so ut aw'd forgetten owt abeaut th' crab, though one o'th' chaps

set some brown pepper o' foire, an' threw it i'th' middle o'th'

reaum. He thowt ther summat to do wi' a drain, an' Andrew Ker owt to

get Ceauncillor Ben for t' bring his nose reaund an' have a sniff. It ther' wurno' feyver i' that hole afore lung it ud cap him!

For o ut this wur gooin' on aw never so mich as gan one thowt at th' crab,

but kept sittin', soakin'.

"Aw geet soaked, too; for when aw geet whoam aw couldno' recollect

wheere aw'd co'ed after aw left th' Plattin'. Eaur Nan never said a

word to me. Hoo never does at neet, becose hoo knows aw shall tell

her nowt. But th' mornin' after hoo begun a-settin' th' pump to wark,

but to very little purpose. Th' day before wur a blank to me then. Aw didno' even remember pricin' o' th' turkey. So hoo geet nowt eaut

on me. Hoo did think aw met ha' browt her summat. Ab-o'th'-Yate

could bring lots o' things whoam for his wife. Aw towd her theau're

nowt to go by. Theau're gettin' int' years, an' wur like to do

summat for a bit o' quietness. If aw'd thowt abeaut th' crab, things

'ud ha' bin grand; but it never crossed mi memory. Aw didno' even

look for mi top-cooat when aw went deawn th' steears; becose eaur

Nan aulus hangs it at back o' th' kitchen dur, so ut roan o'th'

neighbours could see it; becose they'd want to borrow it for

buryin's.

"Days went on; an' Kesmas geet o'er. I' th' place of a goose, or

turkey, aw'd bowt eaur Nan three link o' black puddin's, a peaund o'

tripe, an' a keaw-heel; an' a rare Kesmas dinner hoo made eaut o' th'

lot! Hoo didno' believe ut oather a goose or a turkey wur hauve

as good; an' hoo didno' care if hoo never tasted. But one neet we sit at

th' foire, after hoo'd done cleeanin', an' aw thowt hoo looked a bit

consarned about summat.

"'What dost keep lookin' i' that corner for?' aw said, after hoo'd

carried on a while.

"'Aw do believe we'n rottans, Dan!' hoo said, 'tho' aw've seen nowt

o' th' sooart; but aw get such queer smells sometimes. Has theau

smelt nowt strange?'

"'Well aw mun say ut aw've smelt summat rayther owd a time or two,'

aw said. 'It's happen th' sink.'

"'Nay, it's no sink smell,' hoo said; 'it's too deeathly for that. Ther' met be someb'dy buried somewheere abeaut! Aw've smelt it mony

a day; an' it keeps gooin' wurr; aw've said mony a time aw'd leeave

this heause, for we'n never had no luck in it. We shall be havin' th'

childer deawn o' th' feyver, or summat.'

"'Well, aw'll see owd Jammie-at-Abraham's t' morn,—that's thi uncle,

Ab,—an' if he winno' ha' th' floor poo'd up, aw'll tell him aw'll

leeave th' heause, for we conno' live in it as it is.'

"'That's reet,' eaur Nan said; 'an' tell him it mun be done soon, or

aw shall be gone.'

"So th' mornin' after, aw went a-seein' owd Jammie, an' towd him

what aw wanted.

"'Yo'r aulus wantin' summat,' he said; an' he stamp't an'

storm't abeaut like a madman.

"'Well, it's for yo'r own good,' aw said. 'If aw leeave th' heause—an'

aw'm sure aw shall if yon smell keeps theere—yo'n never get another

tenant; so yo'd betther have it looked to at once.'

"That cool't him deawn; so he towd me he'd send little Sammy, an' ha' th'

floor ta'en up, an' th' soof looked at. It happen wanted cleeanin'

eaut. Aw're satisfied wi' that, an' went whoam. An' th' mornin'

after little Sammy coom wi' his tools, an' begun a-shappin' for wark

at once. He hunted abeaut th' fust for t' find wheere th' smell wur

strungest. He set a place at back o'th' kitchen dur, an' hung abeaut

it like a dog at a rot hole.

"'Heaw lung han yo' had this smell?' Sammy said, after he'd had a

snift or two.

"'Aw've smelt it above a week,' eaur Nan said; 'an' aw believe it

keeps gooin' wur.'

"Sammy hung his yead o'th' slopstone.

"'It doesno' come up here,' he said, as he turned away. 'It mun be

under th' floor. It'll be strange if we turn a corpse up!'

"'Eh, dunno' talk that road!' eaur Nan said; 'theau'll ha' me in a

fit, or summat.'

"'If ther's owt it's here,' he said; an' he begun a-prizin' at a

flag wi' a crowbar. 'Dan, tak' that pig-droiver's top-cooat away;

it's i' mi road. That doesno' smell so sweeat. Aw think it's bin amung th' pigs lately.'

"Aw took th' cooat off th' nail; an' dear o me, aw thowt aw must ha'

dropt! Th' smell ut coom fro' it very nee lifted mi yead off; an' th'

sacret wur fund eaut at once: aw remembered th' crab then!

"'Stop yo'r prizin',' aw said to Sammy, 'aw've fund th' stink eaut;

it's this cooat.'

"'Aw towd thee aw thowt it had bin amung th' pigs lately,' Sammy

said; 'so aw're no' far off reet.'

"'Nay, its a crab aw bowt for mi wife abeaut a fortni't sin', an' aw'd forgetter o abeaut it,' an' aw unholed his crabship; 'oh, beetin-bobbins, heaw it does stink!'

"'It's lucky aw hanno' poo'd th' floor up,' Sammy said, as he

gethert up his tools; 'theau'd ha' had to mak' it good; as it is

ther's nowt brokken. But aw shall want summat to cleean mi throttle

eaut.'

"'Theau'st have it,' aw said. So aw took him deawn to th' "Owd

Bell," an' we booath wesht us throttles eaut; but to my thinkin',

tho' it's twelve months sin', aw've th' stink i' mi nose yet."

――――♦――――

MY CIRCUS TIT.

WHEN aw're quite

a whelp aw're fond o' hosses. Ridin' in a cart, an' th' smell of a

stable wur to me a carriage an' pair an' a ramble through Arcadia. If aw'd bin axt to fotch "Owd Moses's" tit, "Razzorback," fro' th'

fielt, abeaut a mile off th' stable, aw'd ha' done it, if aw'd had a

good skelpin for it th' minute after aw'd crept i'th' heause. Aw're

preaud o' mi job, an' 'gee-wo'd' as aw walked by th' side o' mi

charge, till th' hoss begun a-takkin' no notice o' owt at wur said

to it. If aw nobbut could ha' meaunted on his back it ud ha' bin a

lift above th' cleauds. But a bare back is a difficult place to

scramble on, even for a groon-up yorney; so what must it ha' bin for

me i' mi fust suit o' Shudehill cord? Aw hit on a plan one neet, an'

managed to raich th' height o' mi ambition. When aw'd getten "Razzorback" eaut o'th' fielt, an' had hooked cheean on th' nail, aw

drew him up to th' gate, an' made a hossin-stock on't. Then into mi

saddle aw flung misel', an' away we went, Gilpin-like, deawn th'

road to'ard th' stable.

Aw very soon fund it eaut ut mi tit wurno' coed "Razzorback" for

nowt. Ther no danger on me slippin' off. Aw're held i' mi saddle as

if aw're screwed to it; an' that wur huppen a good job, for what bit

o'th' mane he had looked as if it had bin waxed on, so aw didno'

like trustin' to' mich to' it. Aw've ridden on a three-cornered

iron rail till aw could hardly walk, an' sweighed on th' branch of a

tree till th' bark has takken th' place o' mi cord; but th' ridge o'

this booany structure ut aw're peearcht on wur th' capper of o. It ud bin bad enoogh if aw'd had fair trottin, but when mi Bucephalus,

through one hinder leg bein' drawn up, went wi' a hop-an'-a-derry-deawn,

it meant extra blisters. It didno' matter heaw aw sheauted for folk

to stop him, he haumpled on, his motion lookin' like a cock-boat

when th' sae's a bit fresh. Heaw aw managed to drop off when we

geet to th' stable, or heaw aw stood o mi feet when aw dropt, is a

marvel to me. It wur a good job aw hadno' to bed him deawn, nor nowt

o' that soart. "Razzorback " wur his own chamber-maid. He'd turn to

his stall, kick th' dur to wi' his betther leg, ate a bit o' his

rack, if ther nowt in it, an' then tuck hissel into his bed-clooas.

Th' mornin' after this grand ride aw knelt deawn to mi bobbin-wheel,

as owd Juddie 'ud say "for obvious reasons." Aw yerd mi feyther say

to mi mother, after he'd seen me i' this new posture,—

"Eaur Ab has turned very religious, aw think!"

"What mak's thee think that?" mi mother said.

"He's sayin' his prayers at his wheel; an' he looks very yearnest

too."

He towd true; aw wur prayin' an' very yearnestly as he said.

Poor "Razzorback!" it wurno' lung after that before he walked to his

own funeral; an' he're th' only mourner ther' wur at it.

My fuss experience i'th' saddle cured me o' mi fondness for hosses. Aw went i'th' jackass line; but coome off little. betther. So aw gan

up mi stable notions, an' contented misel' wi' a ride on bawks o'

clog timber or a grooin' branch o' owler.

Whether mi whelpish trials had summat to do wi' mi nerves or no', aw

wouldno' like to say; but ever sin' that time, aw've never felt

misel' gradely safe if aw're at back of a tit's tail. Hunderts o'

times aw've bin i' that predickyment for o that. An' mony a time

aw've held th' reins—while thoose ut's bin droivin' had getten deawn

for summat. But aw've felt o th' toime as if aw'd bin sittin' among

a good crop o' Scotch roses, or made a neest i' an' owd thorn bush. After that, what would yo' think abeaut me droivin'? But aw have

driven; an' mi' limbs are whul; but it's a merikul ut they are. Aw conno' say as mich for th' trap. It's i'th' Infirmary neaw—aw meean

th' wheelwreet's shop. It happened i' this road:—

Jim Thuston wur gooin' to Ireland, an' takkin' a lot o' things wi'

him. He'd gear't up his dog-cart as he coes it, for t' droive deawn

to Manchester. But he couldno' tak' it o'er wayter wi' him an'

leeave it i' th' teawn he didno' like; so what mun he do? He bethowt

hissel' o' me, as he knew aw're aulus at a lose eend. As it

happened, aw're just gettin' ready for t' goo to Manchester misel'

when Jim walked into th' heause.

"Wheere art' for, Ab?" he said, seein' ut aw're teein' mi napkin on

tidier than usal.

"As far as Owdham-street," aw said.

"Theau met as weel go deawn wi' me, then," Jim said. "Aw'm gooin' to

th' Central Station, an' aw con drop thee on th' road."

"Art' takkin' th' milk cart?" aw axt him. "Becose aw'd as lief walk

as sit on that bedside theau has across."

"Nawe; aw'm takkin' th' dog cart," he said.

"Oh! that's betther," aw said. "Aw feel mi cushin days are comin'

on. Bare timber doesno' agree wi' me so weel. What time art' gooin'?"

"Aw'm ready ony time," Jim said.

"An' aw shall be ready as soon as aw've getten mi jacket on, an' put

a bit o' wut cake i' mi pocket," aw said.

"O reet!" an' off Jim went an' fotcht his trap, an' drew up to eaur

dur.

"Theau looks as if theau'rt gooin' a bit furr nur th' station wi'

that leather bag an' thoose tother things," aw said.

"Aye, aw'm takkin' a sample o' pottito seed to Dublin," he said, "Aw'd sich a good crop last back end ut aw con afford to sell a looad

or two. They wanten some new seed i' Ireland. But it'll ha' to be

sent to 'em. They never look after it the'rsel's. They'd keep plantin' th' owd soart till th' wyzles grew no thicker nur mint. Come on, an' meaunt thi peearch."

"Yo'n looken reet enoogh neaw," eaur Sal said, as we sprad th' rug

o'er eaur kneees. "But heaw will th' comin' back be?"

"Aw wondert that misel'; but as Jim said he could leeave th' tit an'

trap i' Manchester, aw're satisfied; so away we drove, Jim promisin'

th' owd rib he'd tak' care aw hadno' a yure turned.

It would meean nowt to this wonderful tale if aw towd yo' heaw we

went deawn; but true to his promise Jim dropped me i' Owdham Street,

an' said he'd wait for me.

"Heaw lung doss' think theau'll ha to wait?" aw ax't him, as he

seemed to know my business betther nur aw did.

Theau's nowt to do ut'll tak' thee an heaur, aw'm sure" Jim said;

"an' aw con afford to wait that lung. If it tak's thi ony

lunger theau desarves puncin' eaut o' th' shop."

Well, aw'd nowt to do nobbut buy eaur Sal a calico dress for th'

next ball, so it didno' tak' me lung. A quarter of an heaur sattlet

it; an' aw're ready for meauntin' my peearch agen.

"Hast finished thy business?" Jim said, wonderin' 'at me bein' back

so soon.

"Aye, an' ordered th' goods sent up," aw said. "Eaur Sal doesno'

know what mi arrand wur, so hoo'll be up in a sort ov a balloon when

aw get back."

"There's nob'dy like thee for lookin' after whoam," Jim said; but he

winked as he said it. "If every mon wur like thee, we should ha' one

hauve o'th' women spoilt, they'd do nowt for the'rsel's. Get on,

Charlie!" (that wur to th' tit) "theau's no 'casion to look into a

furnitur' shop window—theau'rt no' goin' to furnish yet. Goo on, owd

lad!"

We spun deawn Owdham Street like a steeam foire engine gooin' to a

bank foire, an' londed at th' Central afore aw could gradely tak' my

wynt. When we geet to th' station Jim hauled eaut his pottito seed

an' his shirt bag; an' when he'd seed 'em o reet, we meaunted agen,

for wheere, or what, aw couldno' gawm.

We kept droivin' fro' one place to another, wheere aw could see

hosses wur kept, an' wheere ther' a lot o' chaps wi' tight breeches

on, ut aw wondert heaw they could get 'em on an' off. But these

chaps kept shakin' the'r yeads, an aw begun a feelin' a bit

consarned. At last Jim said—

"It's no go, Ab! aw conno get lodgin's for this animal o' mine. Theau'll ha' to tak' him whoam."

"Me?" aw said; an' aw dar'say aw looked like someb'dy ut had just

had th' sentence o' deeath passed on him. "Heaw con aw droive him? Wheay, aw should ha' th' show brokken up into match wood, an' me an'

Charlie i'th' Infirmary afore we geet across Piccadilly. If aw didno'

get i'th' honds o'th' police between an' th' time."

"It doesno' matter," Jim said; "aw conno' leeave it i'th' street. Theau'll ha' to droive for once."

"An' what if we come to grief?" aw axt. "Let's be knowin' summat

abeaut that afore aw'm on this job."

"Aw'll not howd thee responsible for th' trap," Jim said; "an' aw

shanno' be responsible for thi neck. Say thi prayers afore theau

starts, an' do thi best!"

Aw fund aw're in for it, an' aw mun mak' th' best aw could o'th'

situation; so Jim put th' whip into th' socket an' honded th' reins

to me. Then deawn he went, gan Charlie a bit of a strokin, tickled

him just under th' ribs, till he made him doance a bit; an'

cautioned me as to what aw should do for t' keep things straight.

"Dunno' thee go near a box-organ nur a hurdy-gurdy!" he said. "Theau

knows his mother used to be a circus hoss, an' doanced to music. Theau may ha' some trouble wi' him if he begins a performin'."

That wur a piece o' very comfortin' advice, but i'stead o' feelin'

ony yezzier for it, aw felt ten times moore narvous!

"Let him have a bit of his own road, an' yo'll lend as safe as th'

mail. Yap! Yap!" he sheauted, an' off we flew like a trottin' match,

Jim clappin' his honds for us as if we'd bin pigeons just risin'

i'th' air.

Whether we should be th' mooest damaged, or St. Peter's Church ud

catch it th' wo'st, if we coome together, wur a matter o'

spekilation. But it looked sarious when th' cabmen on th' stand geet

howd o' the'r hosses' yeads, an' waited for th' hurricane on wheels