|

Ed. ― Ten chapters of Bezer's autobiography were

published as instalments in The Christian Socialist from 9

August 1851 until the demise of that journal brought his account to

a premature close. Nonetheless, this truncated ― and,

considering the circumstances, surprisingly well written ― record

forms both an interesting and an important portrayal, at first hand, of

working-class life in Dickensian London. Some other slightly later accounts,

taken from The Illustrated London News, appear under 'Deprivation'.

――――♦――――

The Autobiography of One of the

Chartist Rebels of 1848

"And every one that was in distress, and every one that was

in debt, and every one that was discontented, gathered themselves unto

him."

1

Samuel, xxii, v. 3.

|

THE PAST.

"Let those who have in Fortune's lap

Been softly nursed, repine

At days of childhood past and gone,—

Their sorrows are not mine.

Let those whose boyish days were free

From every ill and care,

Regret their flight, in pensive mood,—

Their grief I cannot share.

Let those whose youth in pleasant years,

Untroubled, swift, went by;

With aching heart sigh for the past,—

With them I cannot sigh.

Let those whom now, in manhood's prime,

No cares of peace bereave,

Lament the rapid pace of time,—

With them I cannot grieve.

The retrospect of childhood's years,

To me no pleasure brings;

Nor are my thoughts of boyish days

The thoughts of pleasant things.

My youth was crossed, nor on my prime

Does better fortune shine;

Then why should such a luckless wight

O'er the dull past repine?

No! speed thee time—speed on, speed on!

Thy haste I would not slack;

Still less, believe me, honest friend,

I wish to see thee back.

Speed on—speed on then, to thy goal,

And still with swifter wing!

From me thou can'st take nought away,

Whatever thou mayst bring." |

-1-

THE BIRTH

["A Chartist Rebel permitted to write in the Christian

Socialist! I'll not take in another num."—"Hold, 'Tory Bill,'

say nothing rashly." "What do poor people want? Isn't

there a prison for those who do grumble, and a workhouse for those

who don't, with a Bible and Prayer-book in both places; and a

Protestant (we'll have no Popery there)—a Protestant Chaplain to explain

the texts properly, in order that they may know their duty to their

superiors, and learn meekly to bow to all those placed in authority over

them. Can the rich do more?"—"Yes. They can 'do unto

others as they would be done unto.' They can 'sell (hard saying)

all they have and follow Christ.' They can glorify God, and 'let

his will be done on earth, as it is done in heaven.' They can

confess (out of church as well as in it) 'that they have done that which

they ought not to have done'—own that 'the earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof.' Shake hands with the poor, and

'Brothers be for a' that.'

"Is there anything remarkable then in your life?"

"No, not very; except, perhaps, the Newgate affair—it is the

life of millions in this 'happy land,' 'the admiration of the world, and

the envy of surrounding nations'—where glorious Commerce has

reached such perfection that everything, even the blood, and sweat, and

lives, of white slaves, is bought cheap and sold dear,—so dear that the

average lives of the poor in some towns amount to about seventeen years."

"Oh, I see it all now! You had nought to lose

in 1848, and so your motto was, 'Down with everything, and up with nothing

but anarchy, confusion, and civil war.' Thank God, however, and the

Special Constables, the 10th of April showed"

"Showed what?—that class had arisen against class, where

there ought to be no classes; that the lower orders had to wait a little

longer; that there was a great gulf fixed between the poor and the rich

which nothing but practical—mark! practical Christian Socialism can

remove."

"Pooh, pooh—there must be always poor—the Lord

ordained it—it is His will;—besides, the rich are very charitable—very;

good Dukes of Cambridges everywhere; and this is a fine country after

all—full of soup-kitchens and straw-yards for the deserving poor;

but they are never satisfied."—]

|

|

|

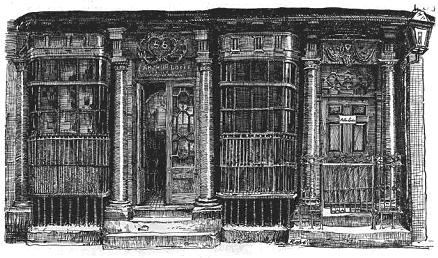

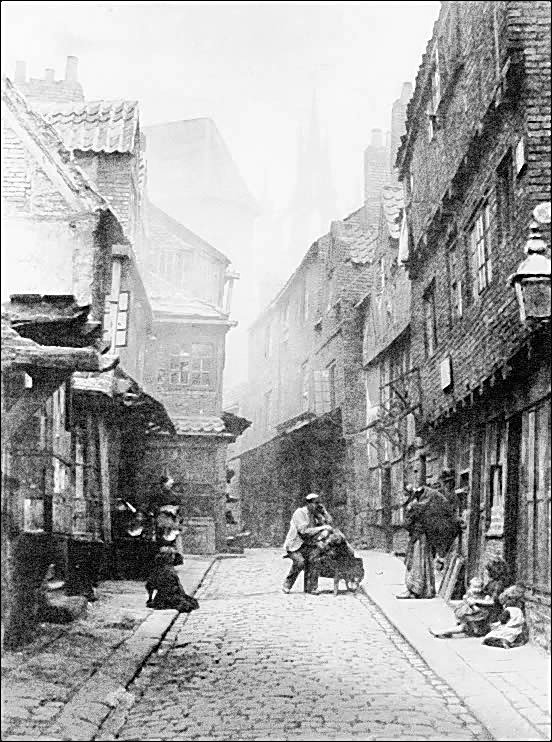

Shop fronts, Artillery Lane, Spitalfields |

Between the hours of eleven and twelve on the morning of

Saturday, 24th August, 1816, in Hope-street, Spitalfields, stood a little

barber's shop, serving for parlour, kitchen and bedroom as well.

"They tells me as how you shaves here for a penny," said a

patron of competition, who had been operated upon aforetime at the shop

over the way for three halfpence.

"Yes, sir, I does," was the bland reply.

|

|

|

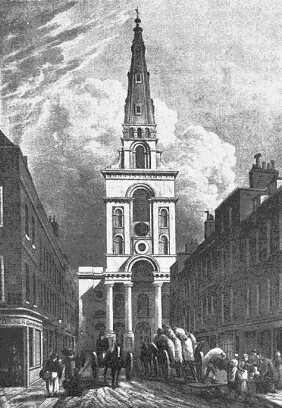

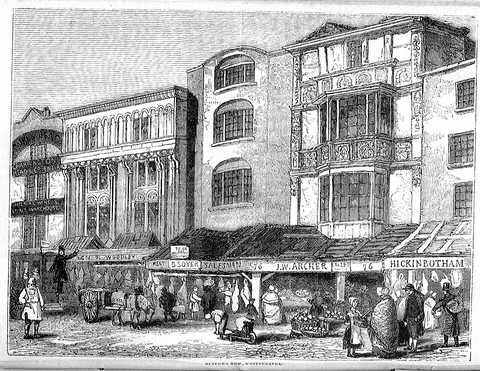

Christ Church, Spitalfields |

The man, after being barberously used,—paid, was thanked,

and the penny—the first that day—placed on the mantle-shelf by

the proprietor of the establishment with a sigh; in five minutes after,

the Chartist Rebel was born in that self-same shop, with that solitary

penny between the three of us, and the brokers in the place

for six weeks' rent at 4s. per week! Strange to tell, mother and

father were both confined on the same day—the former with a

surplus population of one, the reward of twenty years' matrimonial

love,—the latter with a drunken man in a dirty little watch-house, at the

corner of Spitalfields' Church, the reward of knocking down the broker's

man,—father considering in a moment of passion, that he was a surplus

population of one in such an eventful hour as that. "All's well

however that ends well." Father was up and out

again in a few hours, (as well as could be expected, as the ladies say),

five shillings were borrowed from a cousin in White's Row, and never paid,

I believe, (but I can plead the Statute of Limitations; besides I was a

minor then), and better still, the landlord forgave us the rent,

saying it was all through me. Thus was I worth to my parents, the

first day I made a noise in the world, the sum of £1. 4s, sterling.

So it proved "good tidings of comfort and joy" after all. My

ungrateful parents have often told me that I was worth more to them on

that day than I have been worth to them ever since. I can assure my readers that the fact of the goods and

chattels being seized upon made no effect on me,—nay, it would have made

none even if I had been seized upon

myself; so that mammy had been seized with me I should not have minded,

the little I wanted I had, and if I could have sung, I should have chanted

|

"I am content—I do not care,

Wag as it will the world for me." |

Six months after my birth, my left eye left me for ever,—the small pox,

the cause. For two months I was totally blind, and very bad, the "faculty"

giving me over for dead more

than once. The "faculty" were wrong; I recovered, minus an eye, and often

have I been nearly run over through having a "single eye" towards the

road; and often have I

knocked against a dead wall, and hugged it as if I really loved the dark

side of a question. Ah, I've had many a blow through giving half a look at

a thing! How many times

since I became a costermonger has a policeman hallooed in my ear, "Come!

move hon there, vill yer! now go hon, move yer hoff!" while I've

actually thought he was on duty in

some kitchen with the servant girl, taking care of the house as the master

and mistress were out. It was not however so; there he has stood in all

his beauty, a Sir Robert

Peel's monument—a real one, alive,—and sometimes have I seen him

kicking.

-2-

THE SUNDAY SCHOOL*

|

"Then he got eddication,

Just fit for his station,

For yer knows we all on us a summet must larn."

Mister Benjamin Block. |

Right, "Ben," but what? Shall it tend to good or ill? A most important

question, that not only infinitely concerns the neglected victims of a bad

or insufficient education, but

society at large; evil training, sir, is like the measles—catching! he

who commits a bad action has generally learned to do so, and then he

learns another, and so the disease

goes on.

My education was very meagre; I learnt more in Newgate than at my Sunday

school, but let me not anticipate.

Among the many days I shall probably for life remember, is the 21st of

December, 1821, when breeched for the first time, and twopence in my

bran-new pocket, I proudly

marched to Raven Row Sunday School and had my name entered. From that

hour, until the hour I finally left, which, with the exception of two intervenings of short duration,

lasted nearly fifteen years, I can truly say I loved my school,—no crying

when Sunday came round.

|

"I loved that blessed day

The best of all the seven." |

I yearned for it;—whether it was because my home was not as it ought to

have been, (a painful subject I shall feel bound to say something about in

due order,) or because

association has ever seemed dear to me, or because I desired to show

myself off as an apt scholar, or because I really wanted to learn, or all

these causes combined—most

certainly I was ever the first to get in to school, and the last to go

out.

|

|

|

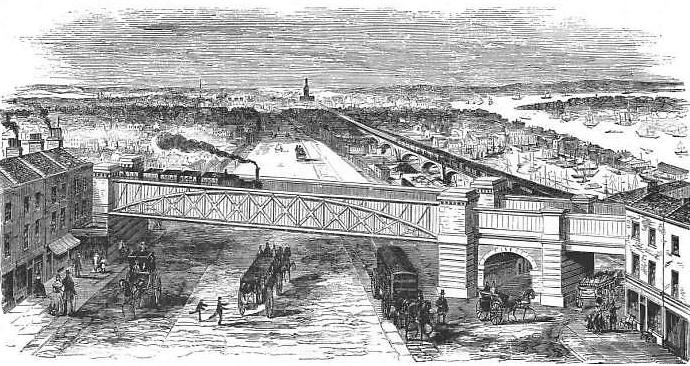

Spitalfields - London's East End, North of the

Thames |

I ought to have learned a great deal, say you, in fifteen years; well, in

the opinion of some, I did, for notwithstanding the disadvantages I

laboured under both at home and at

school, and there only being six hours a week for me, I rapidly rose from

class to class; at seven years old I was in the "testament class"—at

eight, in the highest—shortly

after, "head boy"—soon after that, "monitor"—at eleven, teacher—and

long before I left, head teacher;—and yet, what had I learned? to read

well, and that was all. Three years

ago I knew nothing of arithmetic, and could scarcely write my own name.

I have just spoken of the disadvantages at school—I shall doubtless

displease some of my readers in what I am going to say, but when I

commenced this history, I

determined that it should be a genuine one, and that I would put down my

thoughts without reserve. Now, that school did not even learn me to read;

six hours a week,

certainly not one hour of useful knowledge; plenty of cant, and what my

teachers used to call explaining difficult texts in the Bible, but little,

very little else.

I am not going to enter into any theological discussion, but I am going to

tell the discipline, routine, and teaching of an average London Dissenting

Sunday School of a quarter

of a century ago.

'Tis nine o'clock, Sabbath-day morning, the girls and the boys, old and

young, are promiscuously mingling together on the door steps; about a

quarter past, the teachers

begin to arrive, and the doors are opened—a rush up stairs, and a little

order restored by the superintendent going round with

the early attendance reward tickets, taking at least another quarter of an

hour,—then a hymn sung, very likely the following:

|

"Not more than others I deserve,

Yet God hath given me more." |

And worse

still—

|

"For I have food, while others starve,

And beg from door to door." |

Now, I would rather believe in no God at all, than in such a one as is

described in this verse. What! praise the Great Supreme Being, who is no

respecter of persons, for

giving me plenty to eat, and causing others at least as good as I, to

starve though surrounded with plenty; rank blasphemy! it is such teaching

as this, that keeps up our

monster social evils, from generation to generation, the young mind is

taught to attribute that to God, which only "Man's inhumanity to man" has

brought about. However, I

used to sing it most lustily, though sometimes hungry myself,—and so did

my fellow scholars, whether hungry or full deponent is not able to say. Well then, after the singing,

an extempore prayer by one of the teachers in turn—a prayer, the language

and meaning of which few children could, or desired to understand. At

last, about ten, the classes

are arranged only to be disarranged at half-past, that being chapel time. Afternoon at two, the same manner of "teaching the young idea how to

shoot," till near three,—the

classes are arranged again, and the teacher (probably not the one who

taught in the morning) commences to teach, and what does he teach? It is

an A B C class, say,

composed of twelve tiny little boys, number one says in a drawling dying

tone, "hay," number two, "be-e," and so on, till some one makes a blunder,

and then he's sent last,

his blunder sometimes sharpening the wits of the rest, but more frequently

causing jealousy and in some instances, (I have known them myself,)

lasting hatred. Even this

secular education, bad as it was, did not last above half an hour. The

teacher would tell us to shut up our books, and talk to us about

hell-fire, and eternal brimstone, and how

wicked we was, and if we didn't believe all he said to us, we should be

burnt for ever and ever, which of course made us feel very comfortable

till four,—then another hymn, and

an address delivered from the desk to all the children, the orator

dwelling on some theological dogma, giving his own peculiar views in an

exceedingly peculiar manner—a

prayer—a rush out, and all was ended for a week.

I ask, is such education as this worth having? is it suitable? is it that

sort of "milk for babes," calculated to nourish and strengthen, and

elevate the growing man, who will

grow for better or for worse. You inquire, perhaps, "Would I advocate a

purely secular education?" I cannot say I would. I would inculcate the

being of a God—a God of

justice—of love-of mercy; more—I would impress on the young mind, that

this world of ours was a

probationary state, that they that done evil were punished here and

hereafter, and they that done good, their reward was with them, and future

glory in another and better

world than this; but beyond this, I would no further go; all else I would

leave entirely with the parents, and their respective ministers, every

creed standing on its own

foundation, without help or hindrance from the state.

|

|

|

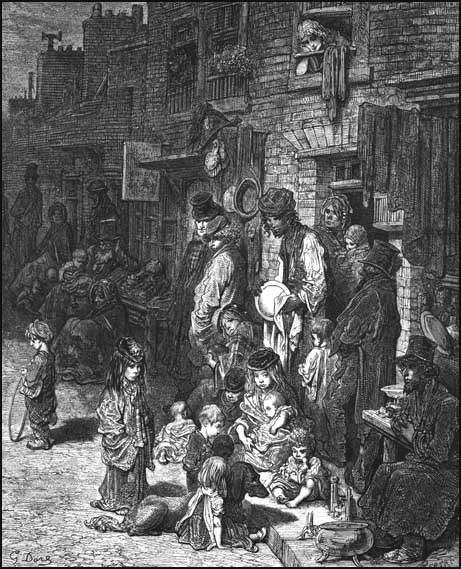

London poor. |

-3-

MY FATHER AND MY HOME

"A crust of bread, a bed of straw, and rags." HOOD.

Father kept a barber's shop, trade was brisk, and times much better than

they are now, so that when he really did attend to his business; he

cleared a good round sum

weekly. Mother also earned at cotton winding (before machinery, or rather

the monopoly of machinery altered it,) nine or ten shillings weekly; yet

there we were, miserably

poor, and the quotation at the head of this chapter was literally my

experience for years during my childhood, except a few short months that I

remained with my aunt, who,

though well off, treated me shamefully, and I ran home again, that being

the lesser evil.

Father was a drunkard, a great spendthrift, an awful reprobate. Home was

often like a hell; and "Quarter days"—the days father received a small

pension from Government for

losing an eye in the Naval Service—were the days mother and I always

dreaded most; instead of receiving little extra comforts, we received

extra big thumps, for the drink

maddened him. The spirit of the departed will pardon, and, I verily

believe, will rejoice at my speaking thus plainly, not only because it is

the truth, but in order to show, as I

shall show, the power of Christian principles as exemplified in the after

life of him who was as a "brand plucked from the burning."

Father had been an old "man-o'-wars man," and the many floggings he had

received while serving his country, had left their marks on his back

thirty years afterwards; they

had done more,—they had left their marks on his soul. They had unmanned

him; can you wonder at that? Brutally used, he became a brute—an almost

natural consequence;

and yet there are men to be found even to this day, advocates of the

lacerating the flesh and hardening the hearts of their fellow creatures

simultaneously.

The loss of a considerable sum of money by my father while at sea through

the chicanery of his sister, tended, I doubt not, to increase his love for

drink. Church or chapel

was never thought of by him from his youth till he was upwards of fifty

years of age; then—but I will give the facts without comment.

The late Mr. Isaacs, of Gloster Chapel, Hackney, used to lecture on

Tuesday evenings, at the time I am speaking of, at Staining Lane Chapel,

City. This gentleman was a favourite minister with my mother, and she was

constantly begging father to go and hear him, without avail; she would

always get ridiculed for her

pains, till Tuesday evening, November 15, 1823, I think,—on that night he

offered himself to go if mother would treat him to some gin. She did, and

we all three went; father

scoffing and swearing, and mother, I doubt not, inwardly praying on our

journey. The service had commenced; indeed, the text—the 40th Psalm, 1st

verse ("I waited patiently

for the Lord, and he inclined unto me and heard my cry")—was just being

read as we entered. Presently I noticed, child as I was, the altered looks

of father, and as the

minister seemed to increase in energy and zeal, father literally trembled

again, so much so that several of the congregation noticed it. At length

the service ended, and

directly we got out, father said, "Mary, my dear,"—the first kind words I

had heard him utter for years—"Mary, my dear, let us go home. God have

mercy upon me, a miserable

sinner." Not a word else, to my recollection, escaped him that night. We

all kept awake, for the scene appeared to my young mind terrible. The

agony of father was

indescribable for several days. At last, without any visitor coming to

him, but solely through reading the Bible, hope dawned upon him, and from

that time till he died, above

eight years, he was a changed man—no more drunkenness or immorality. At

the expense of being laughed at, and called a canter, as I know I shall be

by some who read

this, I cannot refrain from giving a few lines from a hymn he never seemed

tired of singing, because they exactly pourtray his altered character and

feelings:—

|

"These eyes that once abused their sight

Now lift to Thee their watery

light

And weep a silent flood."

* * *

"These ears that once could entertain

The midnight oath, the lustful

strain,

Around the

festal board,—

Now deaf to all the enchanting noise,

Avoid the throng, detest the joys,

And press to hear Thy word." |

The consequences, however, of this remarkable change in my father did not

better our pecuniary circumstances. This may appear strange, but it is

easily explained. My

father's conscientious convictions would not allow him to open his shop on

Sundays, and as it was a very poor neighbourhood,

Sunday was better than all the week beside to him. His customers rapidly

fell off because he was not such "a jolly good fellow" as he was wont to

be. All called him mad, the publicans especially condemning him as a matter of course; his

constitution, too, was so much injured by drink, that the sudden change to

strict sobriety seemed utterly to

prostrate him, and he was always ill. Mother's work also got slack and

worse paid. Still they persevered, and still things got worse, and though

"a dry morsel with quietness"

was a glorious improvement on the past, they could not at last meet the

expenses of the veriest necessities of life. The climax to all was, that

the Government pension was

stopped altogether, in consequence of father petitioning for an increase,

the authorities offering him the hospital. Our little home, which though

humble, had become precious

to us, was broken up, the persecuted saint went to Greenwich College, and

mother and I became out-door paupers to a parish in the City that father

claimed through his

apprenticeship. "All these things were against us," except that they made

a lasting impression on my youthful mind, and I stuck to my Sunday school

and to my faith with all

the fervour and enthusiasm God had given me.

|

|

|

Greenwich Hospital

and Royal Naval Asylum, south aspect, c. 1800. |

-4-

MY FIRST EMPLOYMENT

The parish allowed us four shillings weekly, and with that miserable

stipend, and about two shillings more for cotton winding, we managed to

pay rent and buy bread till the

near approach of Easter in the next year; then we bought buns—not for the

purpose of eating, (though we did eat them after all), but for the purpose

of selling again. Three

shillings and one little basket were borrowed for this important

occasion:—mother put two shillings' worth of buns in the basket, and one

shilling's worth in the tea-tray for me,

and off we trudged different ways. Mother had given me my round, but then

it was much nearer home and Sunday school than I cared about, and worse

still, it was a leading

thoroughfare. Did I want people to see me? No.—"if people couldn't buy

buns without seeing the seller, it was strange," so with aching heart, and

scalding tears, and scarlet

face, I walked up and down the most by-streets, and whispered so low that

nobody could hear me,

|

"Hot cross buns!

One a penny, two a penny, hot cross buns," |

till, all the gods of Homer will bear me witness, they were as

cold as the

corpse of a Laplander; still I called them hot from seven till twelve, and

took the magnificent sum of

Twopence! ... Philosophers talk of never giving up,—I think it was

Charles II. who said, after reading the following epitaph on a tombstone,

"This man never knew fear!" "Then he never snuffed a candle with his fingers,"—and I say to any

philosopher of nine years old,—cry hot cross buns for the first time, for

five hours, till you are as cold as

they are, and hungry enough to eat the "stock," and then if you don't talk

of giving up, you are a noble little fellow. I went home—folks had

laughed at me, had rejoiced when I

wept, but only two persons had bought,—I went home, I say, determined

most dutifully to present mother with the remains of my merchandise,

thinking, of course, she had

sold out, and would be ready to sell mine too, when lo! my venerable and

courageous parent had sold none at all; having met a person she had known

years before when she

was better off, her courage failed, and she came home again almost

directly, and had been looking for me all round the neighbourhood. To tell

you the real truth, reader, I was

right glad of this, spite of our desperate circumstances—it prevented her

finding fault with me; so after we had had our soiree of tea and buns,

mother moved, and I seconded,

a resolution, to the effect that we would never go out with buns any more,

hot or cold. But then what was to be done? "I'll get a place," said I.

"You, boy! so young and so

ailing?" "I will;" and so I did the very next Monday.—May God forgive my

tyrant master for the acute sufferings I then endured....

"If you please, Sir, do you want a boy? My name is —; mother winds cotton

for you, sir; father is in Greenwich College, and we are in great

distress—almost starving, sir; I'll

be very willing to do anything." "Why, you're so little! What's your age?" "Past nine, sir, and I'm

very strong!" "What wages do you want?" "Anything

you please, sir." (The healthy competition was all one side.) "Well, come to-morrow morning, six

o-clock, and if you suit I'll give you three shillings a-week; but bring

all your victuals with you—we

have no time for you to go home to your meals." Thus was I duly installed

at a Warehouseman's in Newgate Street.

Black slavery is black enough, I doubt not, and white slavery is a very

horrid thing in all its ramifications, for it has many—the factory

children, and so on;—there is pity,

however, manifested towards these unfortunates, and sometimes help, but

who ever thought of errand-boy slavery? "Willing to do anything." Yes, and

anything I did,—wait in

the cold and sleet for half-an-hour each morning at master's street

door—clean a box full of knives and forks, a host of boots and shoes in a

damp freezing cellar—gulp down

my breakfast, consisting of a hunk of bread, perhaps buttered, and a bason

of water bewitched, called tea, in the cold warehouse—run to

Whitechapel with a load they called a parcel—back again—"John, make

haste to Piccadilly with this"—back again—"John, your mistress wants you to rub up the

fire-irons and candlesticks, and clean the

house windows"—"John, look

sharp, and have your dinner, you're wanted to go over the water with a lot

of things," (dinner! God help me! a penny saveloy when it was not in the

dog days, and a "penn'orth

of baked plain" when it was, or bread alone at the latter end of the

week)—trail along with my bag full of "orders" along Blackfriars,

Walworth, London Road, City, and back to

Newgate Street—"John, look alive, of Islington Green, wants this parcel

directly"—back again—"Now, John, all the 'orders' are ready for the

West, so as soon as you've had

your tea (tea!), you can start; you needn't come back here

to-night,—bring the bag in the morning." Though master said my time was

from six to eight, yet it was always

half-past seven, sometimes later, ere I could start to the "West," which

meant haberdashers shops up Holborn, Soho, Oxford Street, Regent Street,

Piccadilly, over

Westminster Bridge to two shops near the "Broadway," and then, eleven

o'clock at the earliest, trudge home to Spitalfields, foot-sore and ready

to faint from low diet and

excessive toil, and this, too, for years without one day's intervention

save Sundays, for my master was religious of course. Every night would I

crawl home with my boots in

my hand, putting them on again before I got in, trying to laugh it off

while I sank on my hard bed saying, "never mind mother, I don't mind it,

you know I'm getting bigger every

day." Indeed 'tis hard

|

"To smile when one would wish to weep,

To speak when one would silent be,

To wake when one would wish to sleep,

And wake to agony." |

Certainly I could have left my place, for this is a free country. What

then, should I have got another? And if I had, that's not all—my master

was my mother's master; and if I

had discharged myself, he would have discharged her; he has told me so

often—which of course is free trade—so I toiled on, for father was as it

were dead to me, and mother

always ailing, and I saw no alternative but the workhouse, that worst of

all prisons so dreaded by the poor,—so I toiled on, I say, till I was

about eleven years of age; then

typhus fever laid me prostrate, and for weeks I was to all appearance

dying. I was glad to hear that the parish doctor gave me up, and the

farewell of my teachers and my

fellow Sunday scholars I loved so well, and my poor dear father who

crawled on crutches to see me, was, though affecting, happiness to me. I

felt an ardent desire for

death—but it was not to be. I at last recovered. Still was I thankful

even for my illness, inasmuch as it gave me a respite from

|

"Iscariot Ingots Esquire,

That highly respectable man." |

|

|

|

Spitalfields |

-5-

SIGNS OF REBELLION

My Master was continually inquiring after my health, though he gave not a

sixpence towards improving it; but when I had sufficiently recovered, sent

for me, and offered to

take me back at 4s. a week instead of 3s., and give my mother full work

besides, if I complied with his request. I did so, and the day after heard

that five boys had discharged

themselves during my three months' illness. I had to go through the same

routine—endure the same bullying—but mother did get more work, (though

at ld. a pound, the same

as she got 4d. four years before, and 2d. for just before my illness, but

then that was to make up, I dare say, for the extra 1s. he gave me). Well,

Father would come out of

the College; he rallied somewhat, and went "a barbering" round

Bethnal-green, a sort of itinerant shaver. The parish stopped the supplies

immediately; but Father cleared

about 6s. or 7s.—Mother about 3s. 6d., which, with my earnings, amounted

to 13s. or 14s. per week;' provisions were dearer then than they are at the present time, yet as we

were very economical, not only did we manage necessaries, but our home

became gradually more comfortable. As winter, however, came on,

Father's rheumatism—as bad an ism as a man can be plagued with,—I speak feelingly—laid him on his

beam ends; and

separation was again our fate. The "College" received him till he died. Mother, too, just at this time fell dangerously ill; and for many

nights—hard as I worked in the day—I had

no rest. God bless the poor! they saved her life when parish doctor, and

parish overseer had passed her by, and said that the workhouse would take

me, after they had buried

Mother;—the poor neighbours—not the rich ones—played the part, as they

always do, of good Samaritans, by rushing to the rescue, and nursing her

in turns night and day for

weeks, without fee, or thinking of fee. God bless the poor! Amen!

|

|

|

London Policeman ("Peeler")

ca 1850 |

Master's tyranny became more and more insupportable. I will give the

reader an instance. In the second week of Mother's illness, I was sent to

Mile-end Road with a parcel,

and as we then lived in High-street, Mile End New Town, close by, nature

predominated over my fear of offending, and I came home; it was thought

Mother would not live an

hour. I stayed that hour, and yet she breathed—and I ran back with quick

step but heavy heart. "What has made you so long, sir?" I told him the

truth, and he kicked me! I

never remember feeling so strong, either in mind or body, as I did at that

degrading moment; I threw the day-book at him with all my might, and

before he could recover his

presence of mind, sprang on the counter, and was at his throat. I received

some good hard knocks, which I returned,—if not with equal force,—with

equal willingness, crying,

"Oh, if my poor Father were here,"—"I'll tell Father"—"I'll go to the

Lord Mayor"—"I'll tell everybody." The tustle didn't last long, and the

result was that we gave each other

warning; and I, nothing daunted, threatened to stand outside the

street door, and create a crowd by telling every one as they passed all

about it; whilst he threatened, in his turn, to give me into custody for

tearing his waistcoat and

assaulting him, saying I should get into Newgate Closet before I died. The

spirit of prophecy must have manifested itself in a remarkable manner at

that moment to that great

man. For, lo! as he said, so it came to pass, though many years

afterwards. I will not however, give him all the praise. The "signs of

rebellion" were just then rather clear. I

was, to all intents and purposes, a "physical force rebel," and I doubt

not that "the coming event cast its shadow before" the mind's eye of the

immortal W. that is to say, if

the immortal W. had a mind.

The craven, on that day week, asked me to stay with him; I refused, except

for a week longer; that same night, though, I "got the sack." It was past

nine o'clock when I started for the West, and trailing up Holborn-hill

with my bag full of orders nearly dragging the ground behind me, a

policeman—a new

policeman we called them

then—stopped me: "You sir, what er ye got in there, a?" Now I was not in

the best of humours just then; indeed, "Crushers" were never very popular

with me;—so, (alluding to

the policeman who had stolen a leg of mutton a while before, and which was

all the talk), I answered promptly, looking at the gentleman as impudently

as an embryo Chartist

well could, "Legs o' mutton." "I'll leg o' mutton yer," says he; and off I

was taken to the Station. The Superintendent behaved very kindly to me,

sending the policeman back

with me to Master's, with the complimentary message, that "M. ought to

know better than send so young a boy at so late an hour, with such a load,

round the West-end,

and that the 'Force' had strict orders to stop any one with loads after

nine o'clock, so I had better go in the morning." Master at once gave me

my wages, and ordered me not

to come again, telling me at the same time that when Mother got better,

she need not apply to him for work. But what think you? the next day he

sent for me again, and I

staid with him two months longer, for 5s. a-week, which, with the parish

allowance, that had dropped to 3s. was all that we had.

|

|

Holborn Hill,

from the corner of Snow Hill, with Farringdon Street

on the left

and St. Andrew's Church in the background. ca. 1830. |

The Superintendent of my Sunday-school about this time offered me a place

at 1s. a week and my victuals, and didn't I close in with the offer

without hesitation! The word victuals decided me at once, for Mr. A. kept two Ham and Beef Shops, and

the bare idea of becoming a "beef-eater" was so agreeable a novelty, that

without a moment's

warning to my Newgate-street master, I went to my new situation. I trust my

vegetarian readers will pardon my backsliding; I had been compelled to

luxuriate so long on

vegetable marrow, that I confess it appeared no marrow to me, and I

desired a change; besides, you know, I was led into temptation;—Ham and

beef, after bread and

potatoes! Oh! 'Twas a consummation devoutly to be wished!

|

|

|

Holborn Hill from opposite St. Andrew's Church,

with the entrance to Shoe Lane on the left of the

Church, c. 1830. |

I did not keep this good place, however, but about four months, and it was

my own fault. The apprentice, who was also Master's nephew, was a

wild animal of seventeen years old, and Mr. A. told me from the first,

that I was to try and reclaim him. "John, talk to him, I know you can, and

though he is five years older

than you, your example will shame him into reformation." I did talk to him

like a parson, at first, and acted as I talked; but alas, evil

communications corrupt good manners.

At last he influenced me, not I him; and though I cannot recollect

committing any really immoral or dishonest act, I became very flighty and

careless, and incurred the

displeasure of my kind master, who at length discharged me, and served me

right, for the following very dirty spree:—one day we had cooked an extra

quantity of hams and

rounds of beef, and then got into the coppers to swim, as the apprentice

called it; he escaped without observation, but I staid enjoying myself,

and floundering about in this

novel bath for the people, till, who should come right into the cookery

but mistress herself; it was all over with me; I implored for mercy but in

vain. Master, with tears in his

eyes,—he was a glorious soul—said that he wished he could discharge his

nephew instead of me, but we must part; he gave me a most excellent

character to my next place,

a Chemist's, at the corner of Jewin-street, which I kept for near five

years. What happened there to me, my Christian experience during those

five years, the effects the

agitation for the "Reform Bill" had on my mind, &c., shall form the

subject of my next chapter. What I have already written, and what I shall

write for a little time, is not very

interesting to the readers of this journal, I dare say—it is merely one

of "the simple annals of the poor;" but as John Nicholls has it "It may

perhaps, appear ridiculous to fill so

much paper with babblings of one's self; but when a person who has never

known any one interest themselves in him, who has existed as a cipher in

society, is kindly asked

to tell his own story, how he will gossip!" Exactly so.

-6-

SACKCLOTH AND ASHES

I once clothed myself in sackcloth and ashes, literally so; and this is

how it was,—attend, reader, while I explain, for, believe me, it is

important. We had a library in our

Sunday school; ah, we just had such a library,—"Drelincourt upon Death"

with the lying ghost story attached, that Defoe forged, (little thinking,

good soul, that it would be

made a Sunday school Old Bogie of); then "Allen's" I think, or "Aleyn's"

"Alarm to the Unconverted," and many others too, nearly all of the same

stamp. But two bright stars in this black firmament we had—Nos. 85 and 86, I shall never

forget the numbers, how many times have I read them—Bunyan's "Pilgrim's

Progress," and Bunyan's

"Holy War."—My own dear Bunyan! if it hadn't been for you, I should have

gone mad, I think, before I was ten years old! Even as it was, the other

books and teachings I was

bored with, had such a terrible influence on me, that somehow or other, I

was always nourishing the idea that "Giant Despair" had got hold of me,

and that I should never get

out of his "Doubting Castle." Yet I read, ay, and fed with such delight as

I cannot now describe—though I think I could then. Glorious Bunyan, you

too were a "Rebel," and I

love you doubly for that. I read you in Newgate,—so I could, I

understand, if I had been taken care of in Bedford jail,—your books are

in the library of even your Bedford jail.

Hurrah for progress! How true it is, that

"Even the wrong is proved to be wrong!"

I am digressing though;—let's

see, we were talking of sackcloth and ashes. My teacher, at the time I was

speaking of, was an

earnest gloomy soul who, if he delighted in anything, delighted in

minutely describing the wrath to come; and he could do it well. How have I

cried while listening to him, and

how pleased he'd be at my tears, as if sorrow and religion were

inseparable. One Sunday afternoon he was particularly eloquent on the

anger and vengeance of God, and as

a climax, told us about the men of old who went in "sackcloth and ashes,"

and whose "tears were gathered up in the Lord's bottle" (D—— was always very

grand and figurative

at expounding). As I went home I felt dreadful, yet a beam of hope

shone—oh, if I could only get the opportunity, nobody seeing me, of doing

as the "ancients" did, I should be

saved! So, begging of father and mother (I was not nine years old at the

time) to let me stay in, while they went to chapel—I actually undressed

myself to the skin, got out of

the cupboard father's sawdust bag, wrapped myself in it, poured some ashes

over my head, and stretched myself on the ground, imploring for mercy,

with such mental agony

and such loud cries that the people in the house heard me, and told my

parents about it, though nobody even then knew the truth. Readers will

doubtless laugh at this

childish folly,—I marvel if some of them have not committed quite as

fantastic tricks, if they would only own it! One fellow-scholar I told

this to a few years ago, and who is now

an infidel through such teaching, admitted that he had done precisely the

same. Yes, through such teaching,—and I know several such cases,—children have been brought to

compare themselves to the Manasseh and the "Chief" of sinners, till the

rebound in after years has led them to suppose that they are no sinners at

all, and now they laugh at

everything sacred, because everything sacred was mauled about and

distorted to suit the views (views!) of anybody who unfortunately "had a

call." They were told to believe

in a God of vengeance, and worse still, partiality, and so now they

believe in no God; they have been told that there were "children in hell

not a span

long," and rather than believe that, they have banished every idea of a

future state altogether. It had nearly that effect on me. "High

Calvinists," prepare to meet your God!

your gloomy, blood-stained, fanatical, teachings, have been one of the

principal causes of the spread of atheism among us. Oh, my dear fellow

Sunday school teachers! we

have done that which we ought not to have done—we have bent the twig the

wrong way—it is we, not infidels, but we who have often "turned the truth

of God into a lie", and made a creature of Him Who is the Creator, we

have crippled the glorious image God had made, and then—horrible—then likened it to the imagemaker.

Of course I was "converted" as they call it—oh, to be sure!—and made

head-boy of, because I was a "miserable sinner," and didn't I get promoted

for it; and wasn't I monitor,

and teacher—ay, teacher long before I was twelve years old,—and didn't I

join the Church at sixteen, and was baptised, and called a "dear promising

youth," one who was to

be a "burning and a shining light," a minister in "God's own time," one of

those "few champions for the truth" who would prove to all the world that

nearly all the world was

damned, and that the "elect precious" meant only our own precious selves? But now "I am an apostate," say you; am I? Judge not that ye be not

judged. I am earnest in

propagating that which I think to be truth now, and so I was then, but I

did it ignorantly, and shall be forgiven.

One thing must not be omitted in these humble memoirs; and that is, to

give my testimony against those persons who are so fond of saying, that

religious people are so

because it is their interest, and that their zeal is in accordance with

their pay. I must admit that there are many white-washed walls, many

hypocrites; I could lay bare facts

relative to the conduct of both ministers and people, black enough, God

knoweth. What then? Such statements would only cause additional pain to

conscientious men of all

creeds, and serve no good purpose either. Besides, if we are to attack

persons for principles, there is an end to all argument,—yet is the

outward walk of professors, the first,

the primary thing the poor unlettered men look at—no logic is so powerful

with us as that,—and if the outward walk be wrong, most of us jump to

wrong conclusions. I deny,

however, most emphatically, and with long experience on my side, I deny,

that the motives of Christian people, as a rule, are impure. Those who

look after and get the

"loaves and fishes" form the exception, and this exception is principally

confined (will the Editor allow this sentence to be inserted?) to the

parsons—indeed, when they have

dined, there are nothing near twelve baskets' full of fragments remaining,

they'll take care of that. In the Christian world or in the outer, both

among the Dissenters and in the

Church, those get the most pay who do the least work. There were always

collections, monthly, quarterly, and annually, besides

tea-meetings and other dodges, for the "dear minister" at the chapel I was

a member of; and often have I gone hungry, and mother too, because we gave

our very bread into

the "plates" at the door, which the deacons on both sides thereof held so

close to each other that they seemed to say, "No thoroughfare to

Dissenters on the voluntary

principle." Yet the "dear minister" didn't work a tenth part so hard as I

did in the cause,—but then, mine was a "labour of love." Just as if

preaching couldn't be a labour of love

also; I see no reason why people couldn't make sermons and make tents too

(especially as there's a surplus population of them—I mean parsons, not

tents: just now) in 1851

as they did in 51. Perhaps, however, it's all through machinery.... At all

events, I feel that I am now meddling with things too high for me, and

that the bare suggestion is a

kind of spiritual rebellion. You must pardon my egotism though, if I

describe my Sabbath day's work:—'Tis a summer's Sunday morning. I rise at

six o'clock, and get to Spital

Square by seven, in order to commence the out-door services, which closed

after eight; school just after nine, hard at it, arranging the classes (I

was superintendent at this

time), till chapel service, which I had to commence, being clerk—giving

out the following hymn, perhaps,

|

"Well the Redeemer's gone

Before His Father's face,

To sprinkle o'er the

burning throne!

And turn the wrath to grace!!" |

(Reader, pause, and ask yourself solemnly the question, if this is a true,

a reasonable, a scriptural picture of the unchangeable God, in Whom there

is no variableness or

shadow of turning, and Who is the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever.) Well, chapel would not be over till one, and at halfpast, I'd be teaching

a select singing-class; at

two, school commenced again; at four, I would go out distributing tracts,

if it wasn't my turn to deliver the address to the children, then at

half-past four; this took me till

evening service (often have I had my tea at Spitalfields' pump). Evening

service closed, a prayer-meeting in a large room close by, at which I gave

an address one Sunday, a

fellow teacher composing the hymns suitable—he giving an address the next

Sunday, and I composing the hymns that night for him, which, by-the-bye,

as it was rather a

novel thing, every hymn sung for upwards of a twelve-month being original,

soon filled the place, and we could often boast of having a larger

congregation than the minister of

the chapel. I was never home till after ten at night. I did it without

pecuniary reward, or dreaming of it, and this toil, for toil it was,

though I did not think so then, lasted a

considerable period.

|

|

|

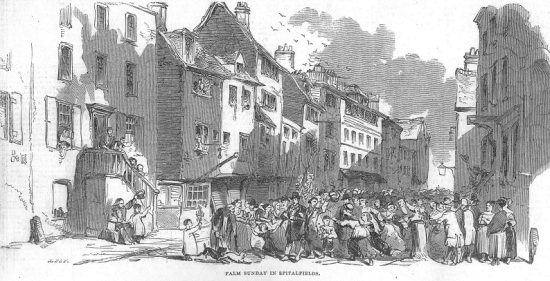

Palm Sunday, Spitalfields |

-7-

A SLAP AT THE CHURCH

I have been requested by more than one valued friend to insert a few hymns

and other compositions of my earlier years. There are several reasons for

respectfully objecting,

but two will very likely suffice. First, I can't, because but one is

preserved; and secondly, I won't, because that one is not worth

preserving. Indeed, if I am to go on jabbering

at this rate, there'll be nobody to read the Rebel's Autobiography save

the Rebel himself, and I want to get over that part relating to my

religious experience as quickly as can

well be, connecting it together at once, without referring again to the

subject.—I have been a Churchman as well as a Dissenter, and the being a

Churchman for a few months

made me a Dissenter for ever. Mother was a Churchwoman according to Act of

Parliament. The poor old body didn't perfectly comprehend the difference

between a church

that was established by law and a church that wasn't, and I have often

thought that if others had, been as dark in their understandings on the matter as she was, there

would have been much less malice, hatred, and all uncharitableness among

us. But no; we have

"perfectly comprehended" how to differ, forgetting—some of us, I fear,

wilfully—that it would be much easier to agree. A good old minister once

said: "There is Calvinist-street,

and Baptist-street, and Wesleyan-street, and Independent street, and

Church-street, and Dissent-street, all leading to the High Road, if we are

but sincere, and we needn't

jostle each other, though the streets are narrow." That's it,

sincerity—

"He can't be wrong whose life is in the right."

But then that's not orthodoxy.—Well, its my doxy, and I am writing

my

auto., if you please.—I protest against a great deal that is called

Protestantism and Dissent from a

great many Dissenters, yet must I have a "Slap at the Church."—This

phrase is borrowed. When I was errand-boy at the Doctor's, the agitation

for the Reform Bill, the whole

Bill, and—botheration to it—nothing but the Bill, was all the go. I well

remember the bellman going round Cripplegate, announcing the majority of

one, and the excitement

created round the neighbourhood. Among the many periodicals living on the

agitation, was one yclept "A Slap at the Church,"—my master's favourite

paper; for master was a

great radical—one who'd beat his wife and shout for reform with all the

enthusiasm of a glorious freeman; like many radicals in the present day,

who can prate against tyranny

wholesale and for exportation, and yet retail it out with all their hearts

and souls, whenever they have an opportunity. Well, this "Slap at the

Church"

I'd con over in my leisure moments. I don't recollect what it contained,

except that it was of a very meagre and abusive description; but I do

recollect that there was always on

the frontispiece a superior wood engraving of an exceedingly elevated

character, most likely a Bishop, who was sure to be represented as

enormously stout. I never had the

honour of seeing but one Bishop in my life, but I have been taught both by

oral and written traditions to believe, that to be a Bishop you must be a

fat man; and so rooted and

grounded was I in this faith, that when a Bishop who happened to be

remarkably thin passed through Newgate Prison, while I was examining for a

few months the place, I

wouldn't believe it was one. "He is indeed," said the Governor, "it is the

Lord Bishop of —." "Then, sir," said I, "the Whigs have been starving not

only the People but the

Priests, and there will be a raw, for they won't stand it."

In a former chapter it has been told you, that mother and I were paupers.—Now mother, directly she got on the "books," was expected to attend her

parish Church; I say expected, because that was the emphatic expression of the poor-law

guardian, and all paupers know that when his worship the guardian expects

a thing, he generally gets it.

Moreover, there were some free seats made on purpose for paupers, so

admirably constructed that most of the dearly-beloved rich

brethren—separated of course by pews, in

direct contradiction to the injunction of that uncouth Christian Socialist

James—could see how their poorer brethren behaved themselves. An

excellent arrangement,—else,

there would have been nothing to look at but the clergyman, and nothing to

hear but merely the gospel. If those seats hadn't been filled by a

respectable number of

non-respectable dependants on our free institutions, the awful spectacle

of Fraternity would have been exhibited in all its revolutionary deformity

in the very House of

God-shocking! So, to obviate such infidelity as that, Twopenny

Loaves—always of the same size—and Sixpence, were given away weekly to

all who could claim the parish,

and who couldn't claim a conscience. I was one of that number,—yes, for

more than six months every Sunday morning, one of that number. "B——, why

don't your son come with you? you know he's on our books." "I'll

tell him, sir." She knew how hard it was to get me away from

my dear Sunday school. At last the order came, ay, the order—do

you doubt my word ? do you tell me that this is England? I repeat, the order;—tyrants can play their game by more moves than one—the order,

in the shape of the following

protestant inquisitorial mandate, given by the Right Honourable the

Guardian, in the year of our Lord, 1828, in the city of London as

aforesaid. "Your boy belongs to us the

same as yourself, and we shall expect him next Sunday; if he don't come,

why, of course we can't keep two of you, that's all I got to say." So I

went—was ushered into the

presence of the Rector, and examined in the most pompous manner

imaginable, "Do you know your Catechism?" "Yes, Sir;" (I meant the

Assembly Catechism by Watts).

"What is your name?" "My name, sir?" "Yes." " ... " "Who gave you

that name?" I hesitated:—the question was repeated with an extra frown,

and I replied, "Uncle, sir; I think he wished me to be named aft—" "Tut,

tut; how have you brought up

this boy, Mrs. B.?" "If you please, sir," said mother in all proper

humility, and with a profoundly reverent curtsey, "he goes to a Dissenting

Sunday School." "Yes, sir," I

added, as bold as a quaker just seized on, "I'm a Dissenter." "Dear, dear,

a youth like him talk in this manner! You ought to know better, B——." "Can

you read, boy?" "Yes sir,"

(I could with truth have added—"a great deal better than you read the

prayers to-day"). "Do you know the Lord's prayer?" "Yes, sir." "The

Belief?" "I believe not, sir." "Well,

you must learn all these things." And so I did; and I don't know that I'm

any the worse for it; perhaps better; but I do think that the effects of

learning them would have been

different, had the wandering sheep been kindlier treated by the shepherd.

He didn't put me in his bosom, or even carry me on his shoulder to the

fold, but he dragged me

there, and that was one of the reasons at least, that I wandered again. I

was confirmed at Bow Church, (by the way, I have made a mistake—I have

seen two Bishops; but

upon my word, he who confirmed me, I don't know if he was fat or

lean),—it was all a task. After Confirmation, I sat on the same bench

with mother, till one practice, which

above all others, to my mind, young as it was, appeared even then

absolutely revolting, caused me to leave:—the vile paupers partook of the

Sacrament after the respectable

among the congregation! Yes; when they had supped off the sacred elements,

the lower orders had the leavings—Spiritual Lazaruses, waiting for the

crumbs falling from a

Saviour's table, the "Common-people's" Saviour. A long way off, in the

Southern States of America, black people take the Lord's Supper after the

white people, and "talented

lecturers," who can't bear black slavery (no more can I, or white slavery

either) expatiate on this matter with "thrilling" eloquence, and amid loud

cries of "shame, shame." Yet

is this same damning insult to God and man perpetrated in our own Temples,

and "talented lecturers" never think of crying "Woe, Woe." Never mind, my

black and white

brother slaves, The Eternal will set all to rights soon. The day is near,

that great day—the books shall be opened, and the first shall be last,

and the last first, Glory to God in

the highest! This sure and certain hope, though, shouldn't deter us from

speaking out on these matters. God hates wrong in all its forms, as much

as we ought to hate it, and

He will help them who help themselves. The "Board" took 6d. a-week off the

allowance three weeks after I refused to go any more to Church—I don't

know why, because they

wouldn't tell us, and I'm not going to insinuate any thing; but such was

the fact; and if it was because of that refusal, why I won't grumble; to

be fined only 6d. a-week for

conscience sake is very cheap as the market goes. Ask France.

You must not suppose that I have not been to a Church since—I have many

times—the first day, the service appeared very cold and dead-like, but

that perhaps was, because I

was so used to Dissenting forms of worship;

for afterwards I gradually warmed towards it, and there is nothing in the

Church service (which appears to me to be very Socialist), at all

justifying such a scandalous

separation of the Lord's people as I have just been describing. Indeed,

Dissenter as I am, (though for reasons Dissenters little think of,) I do

love the idea of a National

Church, but then it must be National; —a Church for the people—the poor

man's Church, till there are no poor. Don't let's whitewash the thing. "Well, what is to be done?"

Done! you have to do very little; your great work is to undo—fall back

upon primitive principles and primitive practices; let there be one

action, and there will soon be but one

Lord, one Faith, and one Baptism. Hunt after the foxes less and the people

more, and you will not have to hunt after them long; think of the "labour

aggression," and you

need not fear the "Papal aggression." Come to the help of the Lord against

the mighty, and the mighty shall fall, and the weak your real strength,

shall gather themselves

together and take shelter under your protecting wing; they have gone under

other wings and found them hollow; take advantage of this circumstance. Many Dissenters have

strayed farther from the good old way than you, and if they had the power

would be much greater despots than you, with all your faults, have ever

been. Take advantage of

this circumstance, I say, in your favour; and let the Spirit and the Bride

say "Come," and we will come. Fewer creeds and more deeds and we

will come.

This is my Slap at the Church, given, I appeal to God, in all humble

sincerity. There must be something done by somebody soon. Will you do it?

|

|

Bezer would have been familiar with such a street

scene. |

-8-

TRADE TRICKS AND SNOBBISM

My employer, the chemist, retired from business with, he admitted, a good

round sum (the profits on physic are rather considerable), so I had to

retire too, from that

business, with half-a-crown he gave me—no doubt a fair share of the

earnings we had accumulated during five years. Shortly after I got a place

at Camberwell. The fact of its

being so far from mother and school was unpleasant; but then, I had my

victuals again—an important consideration—a good bed to lie on, for the

first time in my life, and more

enjoyed the pure air, to me, an unadulterated cockney, not so valuable but

almost as yellow as a guinea, after seeing for so many years little else

than mud; having an

intimate acquaintance with tiles, but no knowledge of stiles; not

remembering anything of fields, except of Spitalfields and Moorfields,

which were no more fields than a

horse-chestnut is like a chestnut horse. The change was like emigrating to

another country—another world. I had lived previously for a long time in Whitecross Place, near

Barbican.

It is said, God made everything. I don't believe it; He never made Whitecross Place, the entrance to which was the narrow way that leadeth

unto

stinks. A gutter passed through the middle of the court—a pretty looking

gutter, from which the effluvia rose up, without ceasing, into our elegant

second floor front; a room, or

rather a cell (we paid 2s. 3d. rent weekly, for the blessed privilege of

breathing in the accumulated filth below); a hole in which the bugs held

a monster public meeting every

night, determined to show what a co-operative movement could do. I say,

God never made Whitecross Place. He is not the author of filthy lanes and

death-breeding alleys.

Landlords and profit-mongers make them, and then proclaim national fasts

to stay the progress of the cholera. "Be not deceived, God is not mocked;

whatsoever a man

soweth that shall he also reap." Camberwell looked more like God's work, a

great deal, and getting up as I did at daylight every morning, with my

master, to help him to dig in

his beautiful garden, made me so happy, and so healthy-looking during my

five months' stay there, that my brother and sister Cockneyites scarcely

knew me, when I

returned to Dirtshire. I made a great mistake in leaving that place; not

that the situation was over remunerative, or the master over kind. He kept

a grocer's shop—that is to

say he sold everything—a sort of co-operative store, of which he was the

sole manager, and I the only member; doing all the cheating according to

his order. I will not be too

hard upon him, though he did make the halfpenny bundles of wood smaller,

by taking out the middle pieces for his own fire-side; though he did sell

the same batter at three

different prices, and performed other numerous innocent trade devices, by

which he became a landlord, and builder of several houses, and was looked

upon as a respectable

man of some standing in society, too magnanimous to pick a pocket, and not

hungry enough to steal a penny loaf. I will not be too hard upon him, I

say, for he salved his

conscience every night by reading prayers, and every week by going to

chapel. Beside, he was not worse than his glorious descendants, the

chicory dealers in Fenchurch

Street, and certainly not worse than the system that engenders and

maintains so much hypocrisy and wrong, nor worse than my former employers

to wit. The first would cut

his ribbons and nearly everything else two yards shorter than their

warranted value, and then sell them at an "enormous sacrifice;" for ever

"selling off," yet never sold; a

bottomless pit of "bankrupt's stocks." Every article he sold he lost at

least fifty per cent by; yet did he live well by his losses, keeping his

servants, and his country house at

Norwood. How was it done? That question puzzled me for a long while,—how

anybody could live by their losses—till one day an Irishwoman selling murphies explained it

beautifully. Says she, "Sir, by my sowl I loses by every tatie I sells."

"How do ye manage to live, then, Biddy?" "Och, I sells so

many on 'em,

that's it." Ay that's it, and the many fifty per cents. W—— lost kept his head above water. He'd have

certainly sunk, had he lost one fifty per cent., but he took good care of

that. Well, even my ham and beef

man could oil his stale saveloys day after day, and ticket them as fresh

Germans; so with my friend, the chemist, whose antibilious pills (I have

made some thousands of

them, God forgive me), were the best

in all the world—proved so by hundreds of testimonials in the possession

of the philanthropic inventor, whose self-interest was the last thing he

dreamed of. The care of the

afflicted was this philosopher's sole aim, and the only reason of his

"twenty years' ceaseless study of that dire and excruciating pain, the

head-ache." I don't think he lost

much by his pills, or he'd have said so, for he was a man of strict truth,

and benevolence, withal; advice was given gratis, which advice invariably

ended in pills; gluttony in

pills was a cardinal virtue—the more you took the better—for him. So

with the Calvinist grocer, whose high, or rather low, antinomian

principles had taken such deep root, that

he thought no more of lying and cheating to save three farthings, than the

Whigs do to save their places. And so used had I been for many years to

help in these swindling

transactions, that no qualms of conscience caused me to leave Camberwell

but this:—On the 16th day of April, 1833, I was helping the servant to

shake a carpet, in the lane,

when her attention was directed to a woman who had fallen on the ground a

little way off. I ran with her to assist, and it was mother—poor mother! She had gone to Greenwich

College, that being her regular day to see her husband, and did see

him, but it was in the "dead house," and then walked from there to

Camberwell, to pour out her grief with the only soul she could, but the

sight of me had unnerved her, and she fainted away on the high-road.

It appears father had fallen suddenly ill, and though both our directions

were with the nurse, she had omitted to let us know, hence our friend,

without shaking hands with either of us, stepped into the river—the

river. His last words were,

according to his attendant and fellow wardsmen,

|

"Sweet fields beyond the swelling flood,

Stand dressed in living green." |

and so he swam over to the other side, without a murmur or a doubt. "Ah,"

says some very clever reasoner, "his brain was turned;" yes, thank God, it

was—the right way.

"May I die the death of the righteous, and my last end be like his."

|

"A happy man, though on life's shoals,

His bark was roughly driven;

Yet still he braved the surge because

His anchorage was in heaven." |

We shall meet again. I would not lose that blessed faith for all the

"reasoners"

in the world. He was buried in the College ground, keeping death-company

with those who

had fought for their king, their country, and their grog. The warriors

rest there in peace; when shall the hated name be altogether forgotten? Oh! for the hour when

|

"War shall die, and man's progressive mind

Soar as unfettered as our God

designed?" |

Oppression must cease first, though; let the Peace Society

remember that.

Mother, who was never of a very strong mind, was this time nearly broken

hearted, and she so earnestly begged of me to leave my place, and get one

nearer her, that I did

so, certainly against my own inclination, for the little surplus of money

I had over and above my urgent necessities helped to comfort her. But I

did leave it; and then began again a bitter struggle for bread. Week after week did I crave leave to

toil; but, no; the curse which to me would have been a blessing, was

denied, and destitution—the very

poor know what I mean by that terrible word—was really felt by us. At

last a cousin says to me:—"Why don't you learn the snobbing [Ed.—unskilled

shoe-making], Jack; I'll

teach you for nothing, and the

first money that you earn you shall have." "Agreed." (I dare say some of

my readers think that my father might have learned me to shave; I think

so, too; but, for some

reasons or other, he ever had a repugnance to it, and that's all I can say

in explanation.) The first week of my "snobbing" we lived upon mother's

pauper allowance, and the last two old chairs we sold for 1s. 9d. The second week I earned by

"sewing" 1s. 10½d., and I lived on that with bread at 8d. a quartern

loaf; a pound of which, and a "ha'porth"

of treacle, was my day's allowance, with a halfpenny baked potato, and a

suck at the pump, for my supper. Can any Vegetarian beat that? I had

4½d. left on Sunday, which

I expended on threepen'orth of bread, a pen'orth of pea-soup, and my

treacle. The next week I rose to 2s. 6d., and rose my extravagance in the

same ratio, not saving a cent.

The next week, 3s. 9d., a shilling of which I gave mother. She thought

that I had had my victuals given me the last three weeks, but I deceived

her, as she had often deceived

me aforetime, by saying she had had a meal when she hadn't, in order that

I might have it; so it was only tit for tat. Well, after that "George"

gave me 5s. a-week, for a

month, and then I worked again for myself, and earned about 6s. weekly,

not increasing for a long time, because each new part of the mystery shown

me necessarily

backened me for a while. At last, in less than a year, I became a snob,

but not a shoemaker; not a tradesman. No; it would be harder for me to

learn to make a good shoe,

than perhaps, if I had never learned how to make a bad one. Cousin was

what is called a "Chambermaster,"—making up on his own account, "Bazil

work;" and after buying

leather, and all the etcetras, how much do you think he had for them? 1s. 4d., which was soon reduced to 1s. Mind, ladies, "spring heels,"

labour, materials, and all. Of

course, the leather was of the worst description; the insoles only paper

and oilcloth cuttings, from the dust yards, and the stitches—I can't

exactly state their length, because

we were never particular for an inch or so, but they were well

black-balled over, to look tidy to the eye, and ticketed as ladies' shoes,

of superior quality, only 1s. 9d.—the

warehouseman and shopkeeper getting 9d. a pair between them, and the maker

not above 3½d. Well may a friend of mine cry, "Cheap, cheap, cheap, means

cheat, cheat,

cheat."

Cousin managed, by the help of his wife cutting out and binding, and one

of his children sewing, to earn a pound, or perhaps a little more, weekly,

but I never could rise above

10s., and this by dint of hard and close work, so much so, that in two

years I was nearly blind, and the doctor ordered me to abandon it at once,

on pain of losing my sight

altogether.

-9-

LOVE, MARRIAGE, AND BEGGARY

While I was a "Snob" I fell, (they may well call it falling), in love, and

I proved myself quite as much a snob in that, as in trying to make shoes. There were some marvellously

pretty girls, teachers in Artillery-street Sunday School,—most of whom

got mated while there, as a reward, I suppose they thought, for their

labours; but I loved the ugliest of

the lot, as my wife will testify, who was not the ugliest of the lot, as

she also is willing to testify. Mary B—, at the time I was 18, was 25

years of age; very short, much pitted

with the small pox, bandy, and remarkably bad tempered. Yet, how I loved

her, no "Lyrics of Love" can tell; and the many poems I wrote, and took

them myself to her in order

to save postage, and get one smile, which was hard enough to get,—I can

tell you, by reason of her plurality of frowns, are too sublime for this

periodical.

I could, I think, write a whole chapter on love-all about "divine images"

and "angelic forms,"—and how the sun shone when she smiled, and how all

the stars looked dim when

she didn't—for lovers can tell the weather by signs better than anybody

else—but age, and reason, and the one object in writing this "auto," call

on me to stay; nor should I

have mentioned this circumstance at all, had not the fact of her jilting

me three separate times (the false Bloomer!) been one of the principal

causes of my leaving my first

love—my Sunday School—and having led me thence by degrees to the very

confines of atheism.

There were two young men in our school, called severally "David" and

"Jonathan," from the fact of their being always together; and their hearts

seemingly knitted together by

long affection. We (for I was David) had joined the school together, got

promoted together, distributed tracts together, joined the same church

together, been baptised

together, and—oh, tell it not in Gath!—kept company with the same woman

together; but that, "David" didn't know, till one Sunday night, having

missed her for a while, who

should come into the Chapel but her own delicious self and—yes, and

"Jonathan!" I was just going to give out a hymn, for which I immediately

substituted another,

commencing with

|

"How vain are all things here below,

How false, and yet how fair." |

And I did sing it too, as spitefully as a disappointed one of five feet

high well could. "Jonathan" carried off the prize. How she could have

induced him—for it was she I'm

sure—bothered me, but I attribute it to her tongue, which was of

considerable length—most ladies' tongues are.

Well, nothing seemed to go right after Mary refused to be such a fool as

to cast in her lot with a boy earning ten shillings a-week.—The Chapel

looked gloomy and desolate,

and I quarrelled with everything. Even the parson I rebelled

against—serve him right, though, for he was very proud and overbearing to

us teachers, refusing even to let the

scholars meet to sing; so I and one of the deacons headed a little band of

malcontents, and opened an opposition shop to preach the gospel of

brotherhood in; that deacon is

now the minister of a flourishing congregation in the Tower Hamlets. After

a time I left him too, and became Clerk at a little Chapel, the minister

of which used nearly every

Sunday to say that nobody but himself preached the truth; and so must his

small congregation have thought, for when he died, they all split up into

individuals, refusing to

listen to any other man.—What hard thoughts of God!

About this time I unfortunately got married, and I did very wrong. Without

any clinging to the unnatural Malthusian doctrines, I own we did very

wrong—both of us. Thank God I

did not deceive her; she knew precisely my circumstances, and bitterly,

very bitterly, have we suffered for our folly. When I married, I was

porter at twelve shillings a-week, at

a place where they bound books for the Bible Society;—every man, woman,

and child working there, were terribly beat down in their wages. Good

Christian people distribute

Bibles to the poor at a very cheap rate, with the words "British and

Foreign Bible Society" outside;—and inside it is written "Cursed is he

that grindeth the faces of the poor."

Outside and inside—the comparison is indeed odious,—oh the cursings I

have heard in that place! not a soul throughout the establishment, that I

knew of, even professed

religious principles, except myself, and I got discharged for doing so.—I

was singing a hymn quite in a low tone while working; one of the

mistresses happened to hear me

and imperiously ordered me to desist, though songs were often sung among

the binders up-stairs. I replied, that I thought it strange I couldn't

praise God while working

among Bibles, and so was immediately sent about my business. This was but

three months after my marriage, and get another place I couldn't. God knoweth I tried, as a

drowning man would try to get to land, for our little home we had somehow

scraped together—and which was much more comfortable than we have ever

been able to get up

since—was every week going—going—going, and our little child every week

coming—coming—coming; and at last it came. That was a horrible day—the

birth-day of my first boy!

Wife, it was thought, would die; and I knew why die—from sheer staring

want. No joy was in our nearly empty room, but all was desolate, and the

very blackness of despair.

"Why not apply to the parish?" Because ever since the day the guardian had

told mother that he wouldn't "keep two of us," it ran in my head, and

mother's too, that if I applied, her money would be stopped. It was a

foolish idea, but we had nourished it

for so many years that it became as it were a creed, and so rather than

rob mother, as I thought, why, let us all die! The next morning, that we

might not die, I went to aunt's

at Old Ford—my rich aunt's, she that had gotten her brother's money,—and

she shut the door in my face. From thence I went to Brixton. "What

for?"—To sing, to beg, to

cadge: I was thinking of omitting this portion of my life; but no, the