|

The following letter, written by Bezer—as Publisher of the Christian

Socialist—was inserted in the issue of 5 December 1851 in response to

an appeal for more readers, but the Christian Socialist was

discontinued from issue No. 61, 27 December, 1851.

________

CIRCULATION OF THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST.

THE CHARTIST REBEL TURNED SPY—

BUT NOT IN THE PAY OF THE GOVERNMENT.

A "free" letter, partly auto-biographical, but very much out of order.

Dear Sir,—When I read your "Appeal" in No. 53, of this Journal [1 November

1851], the first words I uttered were the chorus of one of the songs of

Mackay, I think—

"There

must be something wrong;"

and being convinced of the soundness of those first words with reference

to that "appeal," I went on a voyage of discovery, to find out what that

something was; or, in other words, I enrolled myself as a member of the

"Detectives" not so much to spy out the nakedness of the land as the cause

of it.

As I took notes on my way, more especially as I travelled

"Through Finsbury Fields, on ye road to Bethnal," will you permit the

insertion of them in your "Free Correspondence." What I said, and

what I heard—how, in going down to Jericho, I fell among thieves,—and

all about it.

The first thing I did was to have an interview with the

publisher—an intimate friend of mine, Sir, as you are aware, and who I

knew would tell me everything "without reserve," as the linen-drapers say

when they want to get rid of a slop article. "How is it, my dear

B.," said I, "that the circulation of the Christian Socialist is so

miserably low, though the recognised organ of a practical movement,

numbering its thousands of members, 'cute far-seeing souls, determined to

do what Sir Robert Peel told them to do, take their affairs into their own

hands?" "Why" says he, "there are several reasons, but two only I'll tell

you just now, and the rest another time. One is, that some of the

chaps are too 'cute, for while saving pounds annually

through joining the co-operative cause, they are afraid of spending

a penny to keep it up. And the second is, that some are not 'cute

enough, not having heard as yet even of the existence of the

periodical, as letters on my file will show." "Why, how is that?"

cried I, struck all of a heap. "Ah, that's it—it hasn't been

properly pushed;" and then, whispering in my ear, "it hasn't been

puffed." "Puffed!" I exclaimed with horror; "how can you mention

so detestable a word with reference to such an anti-puffing journal as

this?" Well, at that I did catch it, for what he chose to

call my short-sightedness, telling me—"that puffing according to truth,

was a very different thing to puffing according to lies. That if a

man sold coffee without mixing it with chicory, he had a right to say so.

That those who love truth ought—it was their holy duty—to compete

with those who love falsehood—by proclaiming it on the house-tops, and

zealously asking everybody they can get at,—Who is on the Lord's side?

That in this enlightened age; this middle of the 19th century, the

"glorious many," the "sovereign people," thought truth so valuable, that

you must just take it to them without any trouble on their parts, for the

deuce a bit would they come and fetch it, or even enquire after it, till

they had once tasted it. Then, ah then, eating will increase

their appetite, and they'll cry, give, give, as if in a galloping

consumption. That therefore, "as the supper was quite ready, one

must go into the highways and hedges, and compel them to come in," and so

he went on jabbering away, "How that he'd told a few gentlemen his views,

and they, being as sensible as himself, (as he is rather conceited), they

had cheerfully subscribed £14 for that purpose; how that he had spent £17

out of it, (he would make a good Chancellor of the Exchequer, I

must admit,—if that be a fact), in large showbills, and handsome

window-cards, and inserting advertisements in several newspapers, and

sending a "Perambulator" round the metropolis, announcing that a portrait

of "Parson Lot," (who is a very good lot, by the way), would be given with

No. 56. How that in consequence of the sale of No. 55, had nearly

doubled; that the back numbers were being sent for, wholesale, retail, and

for exportation, by parties who had never heard of it before, or who had

been told that it was dead; how that 500 extra copies had been printed of

No. 56, because he fully expected that people would, that week at any

rate, run for Christian Socialists, as in times of panics they run

for gold; how that,"—"Now, stop, stop," said I, "and do rest that tarnation tongue of your's. I had a long tongue once and got into

Newgate through it: mum, the proof of the pudding's in the eating.

Just give me a few quires of the portrait-number, and some bills and

cards, and I'll go round 'the trade' with 'em." And so I began my tour

eastward.

It has been said, Sir, that that lawyers (beg your pardon, Sir), and

printers, and newsvendors, are an unholy, inglorious trinity, having no

consciences, and willing to do anything to earn a crust. I am not versed

enough in the law to speak positively of the first class, and I shouldn't

like being indicted for a libel. Of the second class, I am afraid to

speak, inasmuch as the Co-operative Printers are all bigger men than

myself. But a number of the third class, I hesitate not to declare, have

been most maliciously belied—to wit:—In one shop I went into, the man

said, in reply to my request that he would put a bill up,—after looking

at it as if it were a Red Republican, with a pike in his hand,—"No Sir,

couldn't do it, conscience wouldn't allow me." "Conscience!" I ejaculated

in surprise, not having heard the word before in a newsvendor's shop. "Yes, Sir,

conscience—Socialist! Socialist! O dear no." "Well, but

Christian Socialist." "Ah, it's all one, all one—it's a revolutionary

thing, I know it is, and wants to upset the government. But I'm a

respectable man," puffing himself out like a bloater full roed, and

doubtless thinking at the moment of the 10th of April, and that dear,

dear, special constable's staff in the parlour. "I'm a respectable man,

and won't sell it—and that's flat."

Readers of Mister Lloyd's elevating, moralizing, instructive murder-tales,

go feast your eyes on the large blood-red pictures, those splendid

triumphs of art, portraying as they do, so accurately, how easily one man

can cut another man's throat, and then go inside, and ask for a penn'orth

of mental laudanum, and you'll not be disappointed;—but Christian

Socialists, go not near the shop, for the respectable proprietor thereof

has a conscience, and a remarkable one.

There were many as bad as he, and some still worse, for they would promise

to expose the bills, and then shove them into the waste place; (these were

the thieves I spoke of just now, while going down to Jericho)—so feeling

that hypocrites had no time redeeming quality, I went back for them;

Christian Socialist bills shall not be torn up at three half-pence per

pound, if I know it. However, I sold the lot I took out, and a goodly

number of shops have them exposed, a list of which I'll give next week. [List not published. Ed.] I mention this, because the publisher tells me,

that a great many readers of this journal go to him and buy, a very bad

arrangement. They should go anywhere but to him. If every reader will buy

at the nearest shop that agrees to put a bill up, it will be so many

standing advertisements gratis. Let every reader take this hint, and the

sale must steadily increase, without a farthing extra outlay.

Well, as I crossed Finsbury Square, I met the man with the perambulator,

and a rare crowd was round him, I tell you, asking each other what on

earth Christian Socialism meant? A very nice-looking gentleman, however,

in a blue coat, and pretty looking figures on it, blandly expostulated

with the breaker of the law, telling him as mildly as the breed can, "that

he'd take it to the green-yard, if he didn't move on." [The Green Yard was

on the east of Whitecross Street, where stray horses, cattle and carriages

were impounded. Ed.] But brother M. wasn't green enough to let him, for he

did move on, but so slow, that one would have thought it were a hearse at

a funeral, while the wondering spectators, like so many mourners, kept

following, and reading on.

Just as I was selling off the last remnant of my stock, in Brick Lane, a

large bill attracted my attention, the subject of which, though not

directly concerning this Journal, has certainly some reference to its

objects. It said, "Old Church, Bethnal Green.—Persons can get married,

banns, certificates, &c., included, for 5s." Halloa, thought I, Soloman,

who for a king was not a fool, said that a virtuous woman was worth a

crown to her husband; but I knew not till now you could buy her at the

price,—when lo! close by the former bill, was stuck up another to the

following effect—"Marriages solemnized at the New Church, Bethnal Green;

banns, and certificate included, only 2s. 6d." Hurrah! Here was

competition in the churches! Therefore, let the rallying cry of

Free-traders be—not a Free-trade and a cheap loaf, but—"Free-trade and

a cheap wife." The Chartist Rebel's advice to persons about to be married—Don't! or if you do, don't fool your money away, but go to the cheap

slop churches, the spiritual Moses [Note: the Editor of the Christian

Socialist inserted a comment at this point—"Wrong, friend Rebel—it

does not follow that a cheap church is a slop church, nor are low

marriage-fees the result of sweating and grinding."] and Sons, who, at

enormous sacrifice, are nearly giving away wives and husbands, to the

great joy of Cupid and the holy horror of the ghost of Malthus.

As I returned home, I ruminated, not so much on political as domestic

economy: here had I been married fourteen years, and the balance sheet ran

thus—Lost, 10s.; gained, 9 children. Oh! if I had but waited for the

good time at last to come! Well, if I ever do meet the parson of

Christchurch, Newgate Street, who charged me the immense sum of 12s. 6d.

for a little woman not five feet high, when I could have one nearly twice

her size for 2s. 6d., I'll just ask for my money back. And so, in high

dudgeon, I went back to Fleet Street, and thus ended my first day's tour. My second, third and fourth were much about the same, and the repeating

them would be tautology. Suffice it, that by the time this letter appears,

not a number of 56 will be in print, except in the Thirteenth Part, ready

last Saturday, and with which a portrait of Mr. Kingsley is given.

And so the publisher and I—and indeed several others—feel that the

journal has not as yet had fair play; and that if the same energy is kept

up for the next three months as has been shown the last fortnight, the

sale will increase to 5,000 weekly in that time, without reducing the size

or raising the price (pray don't do either, Mr. Editor, or you'll commit

suicide.) Of course, this wants money. The wall must come down without

battering-rams. It has therefore been proposed that a "Three Months'

Christian Socialist Advertising Fund" shall be opened, to which the

following have already subscribed:—

| |

|

£. s. d. |

| Thomas Hughes, Esq. |

................. |

1 0 0 |

| Rev. Charles Kingsley |

................. |

1 0

0 |

| Professor Maurice |

................. |

5 0

0 |

| A Lady Friend |

................. |

1 0

0 |

| W. Lees, Esq. |

................. |

1 0

0 |

| F.T.V. |

................. |

0 5

0 |

| Vansittart Neale, Esq. |

................. |

5 0

0 |

| A Chartist Rebel |

................. |

0 5

0 |

I am, Sir, yours very truly,

THE CHARTIST REBEL.

___________________________

|

|

THE LONDON ILLUSTRATED NEWS

Feb., 23, 1850.

STATE OF NEWGATE.

THE Rev. J. Davis, the Ordinary of Newgate, has just

presented to the City authorities the report of the State of the Prison

from Sept. 30, 1848, to Sept. 29, 1849. From this interesting document we

learn that, during the above period, there were in the Gaol—

|

Unconvicted Prisoners |

588 |

|

|

Convicted |

1111 |

|

|

Convicted of very grave offences |

938 |

|

|

Making a total of |

|

—2637 |

|

Of which

number there have been |

|

|

|

Previously in Newgate |

345 |

|

|

——in other Prisons |

385 |

|

|

|

|

—730 |

| The returns for the previous year, to Sept. 29,

1848, were:— |

|

|

|

Unconvicted Prisoners |

645 |

|

|

Convicted |

1418 |

|

|

Very grave offences |

1070 |

|

|

Decrease

under— |

|

|

|

Unconvicted |

57 |

|

|

Convicted |

307 |

|

|

Very grave offences |

132 |

|

|

|

|

—496 |

Making a

general diminution of nearly 500, or nearly one-sixth of the whole number

commited.

The reverend Ordinary observes:—"The gaol of Newgate, beyond

all doubt, has great defects compared with more modern erections; but

results from these more perfect prisons do not surpass the metropolitan

gaol in this respect, that seven out of eight do not return to us again."

Another gratifying point is the great decrease in the number

of boys committed, and great change in committers.

"It is greatly to be desired (continues the Report) that no

sentences (except for very short periods) should take place in Newgate.

The perpetual excitement, the over fluctuating character of the inmates,

the assemblage of criminals of the most flagrant nature, the constant

recurrence of the sessions, make Newgate a very undesirable prison for

purposes of lengthened confinement."

The great corruption of Newgate still appears to be most

fearful in the transport wards. The condition of the transports,

confined for months in perfect idleness, makes them spend their leisure

time in awfully corrupting one another. The language, acts, and

habits of these utterly depraved men; their filthiness, falsehood, and

pernicious animosities; are too bad to be described. The magistrates wish

these men removed to their proper place of confinement. The

Government are unable to comply with these reasonable desires, because

every place is full. The rev. Ordinary than suggests the fitting up

of wards as workshops, as in Millbank prison, and the keeping of the

offenders constantly at labour; and this matter is pressed the more

earnestly, because it has been the cause of all the calumnies that have

found their way into many public documents as to the corruption inside of

Newgate.

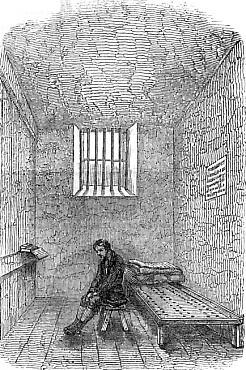

There is another part of the prison that demands

attention—the separate cells, which the Report states are so intensely

cold in inclement weather, that the pain which the prisoners suffer is

almost to the full extent of human endurance.

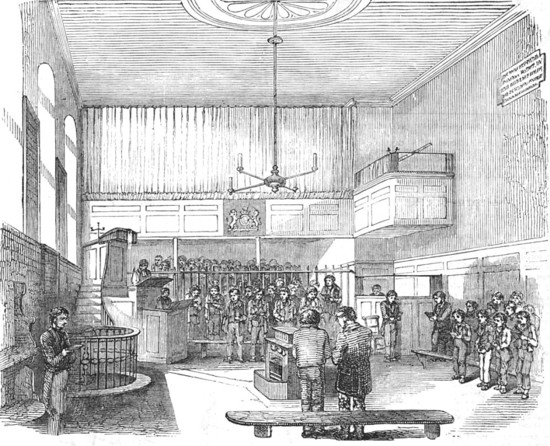

We annex a series of views [Ed.—see below] of the

interior of this metropolitan prison.

Up the narrow steps, into the turnkey's room, and along a

darkish passage, we come into a small open court, surrounded by high

walls, between which a scanty supply of air and light finds its way

downwards as into a well. Facing us stands a massive building, chary

of windows, and those strongly grated: it is the women's wing of the

prison. As soon as the ponderous locks are turned, and the heavy bar

removed, we enter the doorway, and ascend the stone staircase: suites of

chambers branch off on either side, and these are occupied by the

prisoners who are awaiting trial. An attempt is made to classify

them according to their degrees of godliness, but practically this is of

little use.

Pass we now through several rooms and corridors through the

quadrangle occupied by the males. As we traverse these passages we

note the iron character of the building. It is dark, close, confined; and

in despite of the scrupulous cleanliness preserved in every part, foul

smells are not unfrequently met in its lobbies. The great fault is

the want of room, the height of the walls, and the narrowness of the

courts, giving them the appearance of wells rather than open spaces.

Air and light are in consequence less plentiful than than they should be.

Formerly the wards of part of this prison were occupied by

debtors. This practice has been discontinued, and it has now very

few inmates, except such as are awaiting trial or punishment; the

exceptions being persons convicted of assaults or offences on the high

seas. Just after the termination of the session of the Central

Criminal Court it is nearly empty, but it gradually begins begins to fill

again as the next assize draws nigh; then its inmates usually number about

500. After trial the convicts are sent off to prisons or

penitentiaries to which they are committed—the short terms to the Houses

of Correction, the transports to Millbank. Those sentenced capitally

are taken to the condemned cells, not to leave them again until the last

moment, except for chapel. These cells are built in the old portion

of the building at the back. The narrow port-holes in the dark wall

looking into Newgate-street let light into the galleries into which they

open. There are five of them on each of the three floors. The

culprit in the furthest cell on the ground-floor is within a yard of the

passers-by. All the cells are vaulted, and about nine feet high,

nine deep, and six broad. High up in each is a small window,

double-grated. The doors are four inches thick. The strong

stone wall is lined; and, altogether, they present to the eye of the

culprit an overwhelming appearance of strength. In a small

ante-room, near the entrance of the prison, is a collection of casts,

taken from the heads of the principal malefactors who have been recently

executed in front of it—very interesting to the student of phrenological

science.

The quadrangle for the men is much like the women's, but

larger. It consists of two or three yards, and the building

surrounding them. No separation of the men is made other than as the

law requires—namely, into felons and misdemeanants.

Some little instruction is afforded by humane and

philanthropic visitors at the prison, especially of ladies. Dear

Elizabeth Fry used to make the female wards the scene of her pious

labours. She found helpers and successors in the work. Lady

Pirie is a constant visitor and teacher here now—so is Miss Sturgiss.

They read, converse, and pray with their poor sisters.

The chapel, as well befits such a place, is neat and plain.

There are galleries for male and female prisoners. Below and in the

centre of the floor, a chair is placed conspicuously, and marked for the

use of the condemned culprit. On this he is required to sit the day

before his execution in face of the congregation.

Leaving the chapel we repass the yards, one of which is

notable as the scene of a very curious escape—that of the "sweep."

The walls are of the same height as the lofty houses in Newgate-street,

and present a bar to escape which would daunt the most inveterate

prison-breaker. But the sweep surmounted them. Placing his

back in the angle of the wall, he worked himself up by his hands and feet,

pressing them against the rough masonry, until he reached the giddy

height. He then crept along the top or the walls to the houses, got

on to the roofs, entered at a balcony—almost. frightening a woman to

death—and made his way into the streets, where, as the Newgate prisoners

wear no regular costume, he passed unnoticed. He was, however,

captured soon after—as almost invariably happens with escaped criminals.

Now the wall is smoothed and spiked, there can be no escapes in that way.

We have selected these descriptive details from Mr. Dixon's

recently published work on the Great Prisons of London.

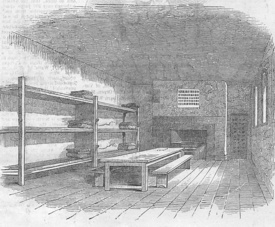

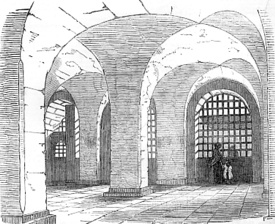

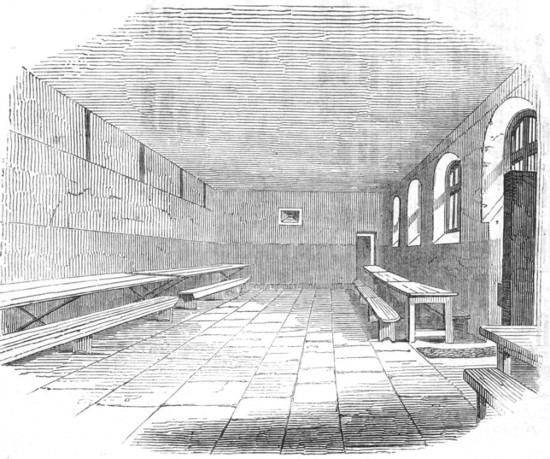

Of the accompanying Illustrations, the first shows one of the

corridors, in which prisoners are allowed to see their friends; next are

the Chapel-yard, and the Chapel; then a Punishment Cell, formerly the

condemned cell; next a Dining Ward; and, lastly, the present ward for

Condemned Male Prisoners.

|

Newgate Prison, 1850.

From the London Illustrated News. |

|

|

|

|

Ward for

condemned male prisoners. |

The

Chapel-yard. |

|

|

|

Punishment

cell. |

|

|

|

Corridor. |

A Dining Ward. |

|

|

Prison Chapel |

|