|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER V.

PADIRAC

(Although I did not venture into the depths of

Padirac, I add a few

lines of description which may prove serviceable to others.)

ROCAMADOUR and

Padirac are two huge accidents, the one an upheaval, the other a

fissure in one of those vast table-lands or plateaux of Central

France called Causses; a word derived from the Provençal, in its

turn derived from the Latin calx or calcinum, lime.

It is only within the last twenty-five years that this

strange region has been explored by men of science and tourists.

Padirac with its stalactite caves, river, and lakelets was only

discovered in 1889, when a Paris lawyer, accompanied by a friend

equally intrepid, ventured into the awful abyss, finding marvels

that recalled Kubla Khan's vision and the stately pleasure house,

where—

|

'Alph the sacred river ran

Through caverns measureless to man,

Down to a sunless sea.' |

Aridity of soil, an arctic climate, solitude and desolation,

characterise the Causes, at their base lying fertile fields, verdant

valleys, meandering streams and silvery cascades. Above, not a

rill, not a beck refreshes the porous, stony soil, the showers of

summer and wintry snows filtering to a depth of thousands of feet

below. Another striking feature of the Caussien region is the

frequently occurring aven or yawning chasm, subject of

superstitious awe and terror among the country folk. These

mysterious openings are locally known as Trous d'enfer

(infernal holes). Alike fact and legend had increased the

popular dread of the aven. It was known that many an

unfortunate animal had fallen into some abyss never to be heard of

after. More than one seigneurial Bluebeard of these regions—so

ran local story—had thus widowed himself. And according to the

country folk of Padirac, the devil hurrying away with a captured

soul was here overtaken by St. Martin on horseback. A struggle

ensued, 'Accursed saint!' cried the evil one, 'thou wilt hardly leap

my ditch,' with a tap of his heel opening the rock before them,

splitting it in two. But St. Martin's steed leaped it at a

bound, the soul was rescued, and the prince of darkness, instead of

the saint, was sent below.

MOUTH OF THE CAVE OF PADIRAC

The descent and exploration of Padirac is the crowning

achievement of my friend, M. E. A. Martel, the Paris lawyer who has

won for himself the title of the Columbus of the nether world.

When in 1889 M. Martel, accompanied by a friend adventuresome

as himself, prepared for the expedition, the country folks were

aghast—'You will get down easily enough, gentlemen,' they said, 'but

you will never come up again.'

The curates of the neighbouring villages were equally

emphatic. Nor is the general stupefaction difficult to

understand, although to that day, the frightful maw, as M. Martel

aptly terms the crater, had never been fenced around or in any way

protected. So far, at least, familiarity had lessened

traditional horrors. From time immemorial the crater-like

opening, three hundred feet in circumference and a hundred feet

broad, had remained without a palisade, Brobdingnagian well

doubtless sucking in many a human and four-footed victim.

Accustomed to the sight of that gueule effroyable although

they were, not a single peasant could be prevailed upon to accompany

the explorers. Not to be dismayed, the pair went down one at a

time. When M. Martel had safely alighted on a half-way ledge

the swing was drawn up for his companion.

Exactly fourteen months to a day after the first descent, a

second was made, upwards of a thousand spectators looking on.

The explorers, now a party of five, had provided themselves with

thirty-five yards of rope ladder, three collapsible canoes, two

photographic apparatus, and electric lamp, with, of course,

provisions, and indeed everything of which they might stand in need.

Their experiences were breathlessly interesting. By eight

o'clock in the evening M. Martel and his companions found themselves

safe and sound at the bottom of the cavern. Several stages had

been first alighted at and visited, the final depth being 250 feet.

A gay and hearty supper was followed by an interval of rest,

and shortly after midnight the little illuminated flotilla set

forth, magnesian lights and electric lamps irradiating the colossal

walls of stalactite as they went. Winding in and out—now

obliged to land and carry their boats and baggage, now gently

gliding from lake to lake, the exhilaration of one moment making

them forget the fatigue of the rest—our explorers reached the limit

of the cavern, further progress being arrested by a solid mass of

rock, no outlet being visible.

It was now nearly seven o'clock in the morning, but three

hours elapsed before they reached the place of embarkation, three

and a half more before they could tear themselves away from their

photographic apparatus to luncheon. By four P.M.

the party had reached the surface, overcome with fatigue and

exposure but enraptured with their experiences. They had

navigated an underground river a mile and six furlongs in length,

its meanderings forming four little lakes separated by natural

weirs, all these set in a framework of glittering stalactites.

'Wonder,' writes M. Martel, 'seals our lips. One by one

the four lakelets are glided over, the rocky walls on either side

draped with stalactites glittering in the magnesian light like

sheets of diamonds, and all reflected in the smooth, transparent

water. Not a sound breaks the stillness of this hitherto

unknown world but the gentle plash of our oars and the trickling of

water from overhead, the hollow cavernous roof echoing the fall,

making soft, penetrating rhythm. Not a living soul had

preceded us on the weird voyage. We are wholly remote from the

living, sunlit, familiar world. We ask ourselves, "Do we not,

indeed, dream? Can the scenes around us be reality?"'

These marvels are now rendered accessible to all. After

nine years of unremitting labours aided by effective co-operation,

M. Martel's discovery, his region of 'antres vastes,' Tartarean

lakes, and marvellous coruscations have become common property.

With the aid of a few enthusiasts, a syndicate was lately formed

under the name of La Société anonyme du Puit de Padirac; the

subterranean region was acquired at a cost of fifty thousand francs,

the mouth of the chasm enclosed, and a safe and easy method of

descending arranged, of this an

illustration giving some idea.

A moderate fixed tariff, five francs, is charged, the

entrance fee including descent, guides, exploration of galleries and

cruise of lakelets and river, the entire excursion occupying a few

hours only. Return tickets combining both excursions, namely,

to Rocamadour and Padirac, may be obtained in Paris at the Agence

Officielle des Chemins de Fer, 1 Rue d'Échelle, opposite the

Tuileries Gardens. About the absolute safety of the

subterranean expedition as now arranged there seems little doubt.

Of course those subject to vertigo or afraid of sudden chills will

enjoy the undertaking vicariously. Rocamadour and Padirac can

be hurriedly visited from Limoges in a day.

'Ah, ladies,' cried a French fellow-traveller, as some days

after, myself and friend awaited the Angoulême train at Limoges,

'you little know what you have missed in not visiting Padirac.

It is grandiose, it is fairylike, it is unimaginable, indescribable.

And only four hundred and forty steps to descend and mount—a mere

trifle!'

Ladies do indeed patronise the four hundred and forty steps

and collapsible boats. A young Frenchwoman of my acquaintance,

who visited Padirac in the long vacation of last year, assured me

that the excursion was comparatively easy, and that fatigue was well

rewarded.

For a full account of M. Martel's subterranean explorations

in France, various parts of the Continent, Majorca, Ireland and

Yorkshire, I must refer readers to his works Les Cévennes,

1890; Les Abîmes, 1894; L'Irlande, 1896; also to his

periodical Spelunca, organ of the Société de Spéléologie.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VI.

BALZAC AT ANGOULEME

IT is a beautiful

bit of country between Limoges and Angoulême, not very productive,

but wooded, pastoral, and abounding in running water.

In Les Deux Poètes the background plays a much more

important part than in Le Curé du Village. Limoges was

peculiarly adapted to such a story, but it is the configuration of

Angoulême that seems to have suggested the tragic history of the

vain little provincial son of a poor chemist, devoured by the

ambition of figuring in aristocratic and literary circles; in other

words, of exchanging his native spot, the commercial quarters of the

river, for the upper town above. Every incident is derived

from this division of the city into upper and lower, and consequent

separation of classes.

In Balzac's description of the city we discern the genesis of

his novelette: 'Built on a sugar-loaf rock, Angoulême dominates the

meadowland watered by the Charente. The importance of this

city during the religious wars is attested by the ramparts, city

gates, and ruined fortresses. It was a position strategically

of equal value to both Catholics and Huguenots, but what constituted

a strength in the past is at the present day a source of weakness;

the city not being capable of extension on the banks of the river is

thus condemned to disastrous fixedness.'

About the time the incidents in this story occurred (1802-30)

'the Government was making an effort to add to the existing town

grouped around the public buildings. But commerce has already

taken the initiative. Long before the suburb I'Houmeau had

sprung up like a bed of mushrooms alongside the river, this faubourg

became an industrial town, a second Angoulême, a lower town

emulating the upper with its prefecture, its bishopric, and

aristocracy. Angoulême proper housed the noblesse and

influence; I'Houmeau commerce and money; two social zones existed at

perpetual variance.

'It is easy to divine how the sentiment of caste divided the

two towns. Business is rich, noblesse is generally poor.

The one revenges itself on the other by mutual contempt. An

inhabitant of l'Houmeau, then, introduced to Madame de Bargeton of

the upper town was a revolution on a small scale.'

Lucien Chardon, who arrogated to himself the title of M. de

Rubempré, was that uninteresting being, a small Apollo Belvedère,

that is to say, handsome, shapely, and possessed of a gift of rhyme

and inordinate vanity. Adored alike by his mother, the

chemist's widow, who earned a living by midwifery, by his sister and

her fiancé, an excellent printer, the young man is enabled to

carry out his views. Owing to the most painful privations on

their part he obtains the necessary outfit for presentation to

Madame de Bargeton, the bel esprit and leading spirit of

upper Angoulême.

Lucien's first evening in the charmed circle of the Ville

Haute is wonderfully described. The young fop's devoted sister

had bought for him with her earnings 'thin boots at the best

bootmaker's of the town and a new complete suit at the most

fashionable tailor's; his best shirt she had trimmed with a jabot or

laced front, which she washed and ironed herself. With what

joy she beheld him ready equipped for his visit! How proud she

felt of her brother!'

The habitués of Madame de Bargeton's salon form a

representative group. The provincial noblesse of the

Restoration is portrayed as Balzac alone could portray it. A

mortification in the midst of his triumph foreshadows Lucien's

future; but as Rousseau has truly declared, vanity is a quite

incurable foible. The unhappy young man, not content with

ruining his sister's husband, becomes a social wreck, his miserable

career ending self-murder. The conclusion of his story,

however, takes us away from Angoulême, and fills a volume and a half

of literary struggles under the title of Un Grand Homme de

Province à Paris.

Most curious and instructive are these pages, a picture of a

Parisian Grub Street, let us hope now non-existent.

The handsome capital of the department of the Charente is

greatly enlarged and beautified since Balzac described it, three

quarters of a century ago. On recently revisiting it, after an

interval of eighteen years, I found a great many new buildings and

improvements; but the essential features familiarised by a reading

of Les Deux Poètes remain intact, and whether we survey the

magnificent panorama that stretches before us on the heights of

Beaulieu or stroll down to the riverside below, we think less of

Coligny and the Duc d'Épernon, of another Balzac, the so-called

'restaurateur de la langue française,' of the Marguerite des

Marguerites, and other historic personages whose history is

interwoven with that of Angoulême, than of the poor vain poetaster,

Lucien Chardon, soi-disant de Rubempré, and his divinity, Louise de

Bargeton. So much more real seem the creations of genius than

the heroes and heroines of tradition!

In Eve et David, which is a pendant to Les Deux

Poètes, Balzac quits the topographical and social for the

industrial aspect of Angoulême. 'Balzac,' observes a French

writer, M. Rambaud, 'must have divined rather than observed men and

things when writing his great series. A comparatively short

lifetime and habits of seclusion did not admit of the close study

and accurate observation suggested by these marvellous

delineations.' The second story, the scene of which is laid in

Angoulême, affords a striking instance of Balzac's intuitive

faculty, or shall we say, deductive methods? The pathetic

history of the wretched Lucien's sister and brother-in-law reveals

an entire industrial phase. Not only do we realise the

struggles of a poor printer, but the conditions of the printing and

paper-making trade under the Restoration.

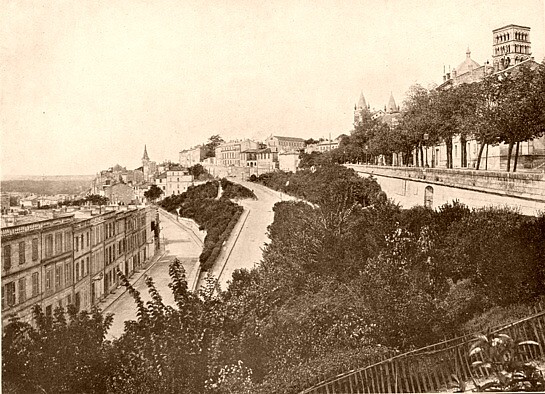

RAMPARTS OF ANGOULÊME

For generations Angoulême had been, as it is today, a seat of

paper-manufacture, and at the time of which Balzac wrote, the

fabrication of cheapened paper occupied many minds. After the

Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, newspapers, which had been all

but banished under the Empire, were multiplied, more books were

written and read. The excessive dearness of paper seriously

hampered commercial and literary initiative.

The subject naturally appealed to Balzac's commercial

instincts, and in reading Eve et David we might take it for a

bit of biography and suppose that the novelist had served his

apprenticeship in a printing office. Again, David's straitened

circumstances gave scope to true Balzacian visionariness.

Lucien had reduced his sister and her husband to beggary; only one

thing could save them, that one thing the traditional chimera, an

invention. Could the poor printer only find a substitute for

cotton in the manufacture of paper, his fortune was made. Now

from 1826 to 1836 a French inventor named Piette had first made

paper of bark, reeds, hay, and straw. At the time Balzac

wrote, experiment and discovery were in the air. It would be

interesting to know how far in David's history the novelist is

himself an inventor. Without possessing the psychological

interest of Les Deux Poètes, this story is well worth

reading, especially at Angoulême. As a study of the bourgeoise,

Eve is worthy to stand beside the noble Mme. Birotteau. David,

too, with his simple, sturdy heroism, is a fine character. The

population of this great city, like the bookworm, may be said to

fatten on paper. The local product is largely exported,

especially to America, whilst home consumption is enormous. An

age of universal education is naturally the zenith of paper-mills.

The bulk consumed in French schools a decade ago averaged two

hundred millions' pound weight, double that consumed in private

correspondence. Very likely the sum-total by this time has

doubled. The devastations of the phylloxera twenty and odd

years ago gave an immense impetus to this industry, turning their

attention to trade.

Angoulême is quite gloriously placed. It stands on a

veritable rock à pic—that is to say, the steep sides of the

rocky summit on which the ancient town and ramparts were built run

perpendicularly to the plain below. The city, with its noble

Romanesque cathedral, clustering spire, and gleaming roofs, rises

above hanging woods and gardens, a veritable coronal of greenery

smiling away all savageness. Lovely beyond description is the

vast plain below, the river Charente—'fairest river of my kingdom,'

said the Gascon king, Henri Quatre—winding its sinuous way amid

avenues of tall poplars and wide pastures, every object being

reflected in its clear waters. Countless green islets, mere

groves and gardens, are formed by the convolutions of the river,

whilst far off are seen white villages and distant church spires

dotting the vast landscape. Most beautiful is the play of

light and shadow on foliage and water when the sun breaks forth; the

yellow tints of autumn are not visible as yet on this September

visit, all the hues are of summer. A dozen subjects for an

artist meet the eye in a single stroll, whether made in the upper

town or the lower, two little worlds apart.

The great charm of the Charente is the unequalled clearness

and transparency of its waters; it is this feature that lends such

beauty and poetic aspect to the immediate surroundings of Angoulême

and the neighbouring country. The effect from a boat is said

to be magical. 'As you gently glide along,' writes one

familiar with the scene, 'amid water-lilies, and removed by a few

yards only from the river's bed, carpeted with dusty verdure, you

must fain believe yourself to be floating in mid-air. The

water disappears. You recognise its presence by the

undulations of the boat and the play of light and shadow round

about.' It is also said that the waters of the neighbouring

Touvre, in themselves bright and clear, look dull by comparison.

To realise the fine position and picturesqueness of Angoulême

the circuit must be made both above and below. The round of

the ramparts is easily accomplished on foot; that of the lower city

is best made in a carriage and continued for some distance on the

Bordeaux road, a drive of an hour or two. Alike from the

heights and the plains, the views are fine and varied.

Conspicuous on all sides, the noblest feature and crowning ornament

of the scene, rises the grand tower of the cathedral, compared by

some to the Tower of Pisa. The ancient fortifications have

been turned to admirable account as a recreation ground for the

people. In such matters French ingenuity and taste are always

equal to the occasion, and this city now affords its inhabitants

sunny, sheltered promenades in winter and delicious coolness in

summer. A fine view of the Charente valley is obtained from

the Promenade Beaulieu, a bit of Knowle Park in the heart of a

bustling, lively, prosperous city. You drive all at once into

a world of greenness and shadow, to emerge as suddenly on the rim of

a vast, open, sunny plain and meandering river; a dozen rivers there

seem to be in one, so numerous and capricious are its sinuosities.

Built in the Romanesque-Byzantine style, St. Pierre of

Angoulême recalls the cathedrals of Périgueux and Poitiers.

The original church dates from the beginning of the twelfth century,

but it was restored in the seventeenth and partially reconstructed

between 1866 and 1875. Thus, as is the case with St. Front at

Périgueux, this noble cathedral has a disconcertingly new

appearance.

Both without and within we are reminded of the St. Sophia of

Périgord, but the resemblance is superficial. Here we have

only one dome visible from the outside, that of magnificent

proportions, the three domes of the interior being roofed in; the

general arrangement, too, is different. At Angoulême we do not

for a moment imagine ourselves in Constantinople, Venice, or

Cordova, nor are we overwhelmed as by the immensity of St. Front of

Périgueux. The façade is of great elaborateness and beauty.

Angoulême possesses some noteworthy specimens of modern

French architecture. The Hotel de Ville (1886), the romanesque

churches of St. Ausone and St. Martial (1854 and 1864), all these

designed by M. Abadie, do great credit alike to municipal enterprise

and taste. It is astounding how money is always forthcoming in

France for the embellishment of towns!

The historic heroine of Angoulême is Marguerite de Valois,

that gracious figure so worthily commemorated here in marble.

As 'shines a good deed in a naughty world' so does her gracious

personality irradiate an epoch of dark superstition and intolerance.

Poet, story-teller, patroness of art and letters, stylish, we love

best to think of the woman who 'disdained no one,' to quote an old

historian's noble eulogium, to whom every man was a brother, every

woman a sister, and whose voice was ever raised on behalf of the

down-trodden and unhappy. Mother of the great queen, Jeanne

d'Albret, grandmother of the greatest king who ever sat on the

French throne, Marguerite d'Angoulême vindicates the theory of

spiritual heredity. In spite of bigoted protests to the

contrary, the protectress of Marot and Bonaventure des Périers,

there is no doubt that she died, as she had lived, a Protestant.

How came it about, one may well ask, that so sensitive and

refined a lady could pen stories in the freest vein of Boccaccio?

The answer is simple. Libertinage was in the air; she but

caught, or rather unconsciously imbibed, the tone of the day.

Politeness and moral latitude went hand in hand. As M. Henri

Martin has remarked, the court of François Premier developed a new

society, hitherto without precedent, witty, learned, graceful and

licentious. Every one versified, courtiers, courtesans, grave

magistrates, the king following suit. And some versified to

good purpose. Marot called Marguerite d'Angoulême sa sœur

de poésie, and she shone equally in verse and in sisterly

devotion. When, having lost all but honour on the field of

Pavia, the king was detained a prisoner in Spain, he fell

dangerously ill. Epistolary literature shows nothing more

touching than the letters she despatched before hastening to his

side. Grave, gay, patriotic, devotional, domestic, in turn she

tried every note that might inspirit and console the prisoner.

The attitude of Marguerite towards reform made her many

enemies, some of whom have not hesitated to bespatter with mud a

name singularly endearing. Born at Angoulême in 1472, she died

in 1549, having been twice married, first to Charles, duc d'Alençon

becoming a widow in 1525, she married Henri d'Albret, King of

Navarre. The Heptameron is a classic, and some of her

verses are poetry, not those, to quote Herbert Spencer, 'of a victim

of the verse-making disorder.'

Lovers of architecture will find much to interest them in the

Charente, the round arch predominating. In museums and art

collections, Angoulême is exceptionally poor, indeed, it may be

said, undowered. An unrivalled position, a magnificent

cathedral, and abundant walks and drives make up for such

deficiency.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VII.

THE GENESIS OF EUGÉNIE GRANDET

IT is now many

years since I visited the home of Eugenie Grandet—can we think of

Saumur without recalling Balzac's famous novel? And if I returned

thither I should most likely endorse my first impressions. We may be

very well sure that this most ingratiating little place, so sprightily perched on the Loire, has advanced with its neighbours'

material progress and civic enterprise; then gradually changing its

physiognomy.

Saumur, then, is an elegant, animated town with pretty, white,

slated villas, each standing in its own garden; magnolias,

oleanders, pomegranate-trees and other tropical plants here

flourishing as on the Riviera.

A couple of fine bridges span the Loire, and these, during the war

of 1870-1, the townsfolk intended to blow up at the first sight of

the Prussians. The enemy fortunately did not arrive, and the gay,

gracious little town was left intact.

Once as Protestant as Protestant could be; the principal commerce of

the place to-day is the manufacture of rosaries! Until the

revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Saumur numbered 25,000 souls, the

population is now just half that sum-total.

Life and bustle are afforded by the great Cavalry School, which is

perhaps answerable for the saying—'Fait-on toujours l'amour à

Saumur?' It looks essentially a love-making place, so smiling and

coquettish are its suburban-like streets, for the country has crept

in everywhere, and you can hardly lose yourself amid roofs and

walls, trees and gardens.

In the steep, narrow, ill-paved street leading to the chateau we

still find ourselves in Balzac's Saumur. Here little is changed

since the novelist penned that wonderful description, an

unforgettable picture in a few words. The cobble-stones only from

time to time resound with the clatter of footsteps. To-day, as three

quarters of a century ago, the inhabitants talk to each other of the

weather as they stand on their doorsteps, 'the barometer alternately

cheering, subduing, or rendering gloomy their countenances.' More

than one ancient dwelling recalls the home of Eugénie Grandet, but

the especial one associated with her name was pulled down some time

ago.

One feature of Saumur unconnected with romance the curious should

not miss. Until 1872 the sick and agèd poor of Saumur were housed in

caves and grottoes after the manner of Troglodytes. Saumurois

acquaintances kindly conducted me over these strange precincts,

surely the strangest ever consecrated to works of pious benevolence. How the old and infirm were ever hoisted up to the rocky eminence

turned into an hospital it is hard to conceive; of one thing we may

be certain: once up they never got down again. In the sides of the 'tuffeau'

or yellow chalky rock, doors and iron gates opened into

far-stretching cavernous passages and chambers only lighted and

ventilated by the door, these subterranean habitations forming the

wards of the hospital! On the terrace outside, a few flowers and

trees have been planted, and there the less feeble took the air on

sunny days, but in their beds the patients enjoyed less light and

air than prisoners of the bad old times. Under the Third Republic

the premises, if they can be so called, were shut up, and a large

airy hospital was erected. Most picturesque is the sight of this

ironically named 'Hospice de la Providence.' You look down on the

white, joyous-looking town with its flowers and greenery, and the

broad clear Loire flowing amid sunny banks and fertile reaches. And

beautiful is the drive of an hour and a half to Fontevrault. On one

side rise the green heights commanding Saumur, Dampierre, and Souzé,

crowned by their chateaux and encircled with villas, on the other

the river glides between verdant slopes and rushy, willowy banks.

The churches of Saumur are very interesting; the town possesses a

museum rich in Celtic and Gallo-Roman relics, a botanical garden,

theatre, and good public library, in fact the resources of a capital

in miniature.

Here was born and lived that skilled Hellenist, Madame Dacier. But

an unsophisticated heroine of romance has eclipsed the paragon of

learning. In our wanderings here we forget the translatress of Plato

and Sappho, we can only dwell upon poor little Eugénie Grandet, and

the good things she contrived to smuggle for faithless cousin

Charles.

I have called Eugénie Grandet the heroine of romance, but is not the

very name an anachronism? Have not all heroines of romance really

breathed, moved, laughed, cried like ourselves?

Recent research would seem to show that such at least was the case

with one of the most pathetic figures in fictional portraiture. And

almost as much time, pains, and ingenuity have been bestowed upon

unravelling her origin as upon excavating Pharaoh's tomb or the

palace of Minos.

It is, as we should expect, to French writers that we are indebted

for the genesis of this famous little novel. In his delightful

flâneries or literary zigzags through France, M. André Hallays has

recently given us the story. [p.102]

Whilst visiting the fifteenth-century château of Montreuil-Bellay,

lying about half-way between Angers and Poitiers, M. Hallays was

struck by the perpetual reiteration of a name:—'Monsieur Niveleau,'

a former owner, 'did this, Monsieur Niveleau did that,' said his

guide.

'And who was Monsieur Niveleau?' at last asked the tourist.

'You don't know?'

'Indeed no, I never heard his name before.'

'Not heard of Monsieur Niveleau! Why, he was the père Grandet and no

other. It is even averred that Balzac wanted to marry his daughter,

that he was sent away with a flea in his ear, and revenged himself

by writing the novel. But, ask further particulars when you get to

Saumur—every one knows the history of the père Niveleau.'

M. Hallays followed this advice, with the result that we have an

authentic history of Balzac's old miser and usurer.

The real père Grandet—in other words, Jean Niveleau, began life at

Saumur as a rag-merchant, afterwards becoming a money-lender;

finally, having amassed an enormous fortune, he purchased the

château of Montreuil-Bellay, himself in threadbare garments acting

as cicerone and complacently pocketing visitors' tips! He married an

apothecary's daughter, who bore him two daughters and a son, one of

the former, the accredited Eugénie of romance, being locally

celebrated for her beauty. Here, however, the thread connecting fact

and fiction breaks off. 'La belle Niverdière,' as Mlle. Niveleau was

called after one of her father's estates, in 1830 married the Baron

de Grandmaison, uncle of the actual owner of Montreuil-Bellay.

In a postscript to his chapter, M. Hallays throws further light on

this curious problem. Dismissing as apocryphal the story of Balzac's

proposal, affront, and revenge, our author gives the following

facts, which he believes to be exact:—It happened that Balzac was

visiting his friend, M. de Margonne, at Sache near Azay-le-Rideau in

Touraine, when one evening another guest, M. de V—, related the

history of the père Niveleau. Balzac was so much struck with what he

had heard that he straightway started for Saumur, and revisited the

place upon several occasions, picking up all the stray information

he could get about the usurer and his family. One favourite method

of obtaining materials was to jaunt hither and thither by diligence,

and enter into conversation with the passengers, most of whom would

naturally belong to the neighbourhood.

And if the père Grandet may be considered a real personage, may not

the same be believed of his daughter? Might not Balzac have unearthed

some love story anterior to the heiress's marriage with M. de Bonfons, an aspirant to the peerage—and the condition of

widowhood—in other words, that he might enjoy his wife's fortune?

Be this as it may, no more moving story was ever penned than the

history of Eugénie Grandet, and never was any immortal fabric

fashioned out of simpler materials. An artless girl, capable,

despite her simplicity, of ardent passion, is parsimoniously brought

up by the wealthy parvenu, her father. In childhood and early youth,

maternal devotion and the tenderness of an old woman servant suffice

to fill a heart hungering for affection. But on the threshold of

womanhood a quite different and deeper feeling is awakened. The

arrival of her cousin Charles, a finished Parisian fop, 'who

imitates the expression of Lord Byron in Chantrey's bust,' is the

first, the only real, event of Eugénie's monotonous existence. For a

time the tragic death of his father affects Charles's shallow

nature. Maybe for a time he believed in himself, and that the secret

vows exchanged under the walnut-tree would end in marriage. 'As on a

moss-grown bench of the little garden they rested till sunset,

exchanging little nothings, or silent as the house itself, Charles

comprehended the sanctity of love,' whilst Eugénie, surrendering

herself to new delicious impressions, 'seized upon happiness as a

swimmer catches hold of a willow-branch in order to alight and rest

on the river's bank.'

Her lover sets sail for the Indies, and after being awaited fifteen

years in vain, marries a Marquis's daughter; Eugénie, for reasons

made to appear plausible, contracting a nominal marriage with a man

she despises.

Not only is this acknowledged masterpiece a narrative of extremest

simplicity, but, with the rest of Balzac's stories, it has no

pretensions to style. 'Le style, c'est l'homme' does not indeed hold

good with Shakespearian novelists, for Balzac's great forerunner,

the glorious author of The Bride of Lammermoor, was equally careless

on this head. And the two chefs-d'œuvre have much in common: the

simplest, directest narration, nothing to be called plot, but

something, everything, that arrests, fascinates, and moves a reader,

touching the very roots of his nature.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VIII.

GUÉRANDE AND 'BÉATRIX'

LONG ago also I

visited the scene of Béatrix. At the time, I wrote that

already local Haussmanns had been at work, and that modernity had

invaded its antique solitudes. But the Guérande described by

Balzac was there. On entering the town from Bourg de Batz, I

was at once carried back to the year 1836, 'when the Du Guénic

family was composed of M. and Mme. du Guénic, and of Mlle. du Guénic,

eldest sister of the Baron, and of the only son of the former,

Gaudebert Louis Calyste.'

A novel experience was that excursion to Guérande by way of

St. Nazaire, Le Pouliguen, and Bourg de Batz.

GUÉRANDE

At six o'clock on a bright Sunday morning in September, I

started with friends from the little station of the Bourse, amid a

crowd of holidaymakers, reaching St. Nazaire at half-past eight.

No railway at that time reached Le Pouliguen, so we took a carriage,

breakfasting as we drove in an open vehicle drawn by a brisk little

Breton horse. Except for the calvaires or crucifixes

placed at frequent intervals by the roadside, we might have fancied

ourselves in Sussex, so home-like was the scenery. The autumn

air was keen and invigorating, but as we got farther on the clouds

grew lighter, and a brilliant sun accompanied us the greater part of

the way. Turning off at Le Pouliguen, we found ourselves in

scenery of wilder character, and, excepting for a solitary peasant

trudging to church here and there, all was deserted. Between

Le Pouliguen and Bourg de Batz lie the marais salants with

odd, indescribable effect. The neatly divided œillets,

or lakelets, of the vast salt marshes cut up the expanse into a

small Rob Roy pattern, each little square of salt water being fenced

in by a small path. On either side grow seaweeds, or

sea-plants, some in rich blossom as we passed by. No words can

give a just idea of this unique spectacle. To the right and to

the left were fields and fields of smooth, glistening, liquid salt

portioned out into myriads of tiny basins of equal size and

shallowness, all silvery white in the autumn sunshine. Far off

the imposing church-tower of Bourg de Batz rose high above the

plain, and behind it lay the sea—to-day calm and smooth as the mimic

seas around. As we slowly ascended the hill crowned by the

church a more curious spectacle still awaited us. The people

were returning from mass, and to behold them it was hard to believe

that we had left fashionable and cosmopolitan Nantes only a few

hours before. Imagination cannot picture a more fantastic or a

prettier sight than this stream of church-goers with prayer-books in

hand, who looked in their inimitable costume as if they had walked

straight out of the Middle Ages, instead of living in close

proximity to an ironed-out, uniform, nineteenth-century

civilisation. Picture to yourself, then, a crowd of village

folks thus dressed: the men in hats with brims as broad as a

banana-leaf gaily tasselled and braided, vests and under-vests

reaching to the hips, all gaily coloured and embroidered, and lastly

puffed breeches, knickerbocker trousers, pantaloons—call them what

you will; certainly, leg-coverings of more piquant pattern were

never invented than the balloon-like garments of creamy-white stuff,

tied under the knees with long white ribbons; white stockings and

white shoes completed the costume, every part of it being spick and

span, as of gentlemen masqueraders going to a ball. A

masquerade, indeed, this procession might have been but for the

prayer-books and staves. It is impossible to convey any idea

of the dignity of these tall, stalwart paludiers, returning

home from their devotions, all utterly ignoring the inquisitive

strangers who had made the journey from Nantes on purpose to stare

at them. The women were less imposing, less solemn, less

unreal. Their dress was nevertheless piquant and coquettish—a

transparent white lace cap or hood, worn over a black-and-white

under-cap, resembling nothing so much as a plume of guinea-fowl's

feathers on either side—a gay little shawl reaching to the waist,

large bright-coloured apron, kilted skirt, most often of black, and

having leg-of-mutton sleeves. The crowd was divided into

groups, who chatted cheerfully, but with a soberness befitting the

occasion. The look of manly independence in every face, the

neatness and elegance of their dress, their evident piety and

devotion, were touching to behold. The Brittany of Émile

Souvestre has all but disappeared, and I fear that twentieth-century

travellers will miss the dazzling spectacle I record.

Guérande is superbly situated, and is a most picturesque, ancient,

dead-alive town. It stands on high ground, commanding a wide view,

and is still fortified, having imposing gateways on either side and

walls all round. Outside the fortifications is a charming walk

bordered by trees, and the glimpses of the quaint old streets

through the gateways, the reflection of the foliage in the moat, the

open country beyond, the grey walls festooned with flowers and ivy,

make up a charming picture. It is so tiny a town that you can walk

round it in a quarter of an hour or thereabouts. According to

Balzac, the circular avenue of poplars is due to the municipal

authorities of 1820, who at the time were much taken to task for

such an innovation. Conservative of the conservative, alike in small

things and in great, has ever been Brittany. As good luck would have

it, the town council persisted in its tree-planting, thus deserving

the thanks of successive generations.

Balzac asserts that Guérande, Vitré, and Avignon are the only French

towns preserving their feudal appearance intact. He had apparently

never heard of Montreuil-sur-Mer, Saumur, Provins, and Carcassonne,

these by no means exhausting the list of completely walled-in towns. This, however, by the way. Balzac was not writing a treatise on

French geography, but painting the background of a picture, a

background almost as informed with vitality and suggestion as the

characters animating his canvas.

Victor Hugo lends sympathy and intelligence to winds, waves, rocks,

and trees—Balzac does not ostensibly go so far, but in his elaborate

delineations of dwellings, interiors, furniture, and decoration

makes us realise how surroundings seem part of an individual. Page

after page is devoted to the home of the old Breton family, 'who

were nothing to anybody throughout France, a subject of pleasantry

in Paris, but who represented all Brittany at Guérande. At Guérande,

the Baron du Guénic was a great baron of France; higher stood only

one man, the king himself.'

The minutest details are given about the various members of the

household, the baron, an old Vendean who, excepting his breviary,

had never read three books in his life, and who on the Restoration

had received the grade of Colonel and a pension of two thousand

francs yearly. Fanny, née O'Brien, the young Irish wife

married in exile, 'one of those adorable types that only exist in

England, Scotland, and Ireland.' Mlle. Zéphyrine, the baron's blind

agèd sister, who would not be operated upon for cataract, affecting

timidity, but in reality aghast at the notion of twenty-five louis

being spent upon the operation! A louis, be it remembered, at that

time represented twenty francs, so that the sum was considerable,

just twenty pounds of our own money, and Mlle. Zéphyrine seems to

have had nothing of her own.

Madame la baronne, it must be confessed, had little of the

Irishwoman about her except that she wore her hair in ringlets

hanging on either cheek à l'Anglaise.

Just as Dickens penned lamentable caricatures when drawing a French

lady's maid, so in a single sentence Balzac here paints the typical

French mother.

In contemplating her son's marriage, we are told that the very last

thing entering into Fanny's calculations was the question of love. Calyste's marriage was to be essentially a French marriage, in other

words a partnership based upon material consideration and the

general fitness of things. The young man, spoiled darling of the

household, remains a pale, uninteresting creature throughout the

volume. Not so it is with Gasselin, majordomo and man of all

work, and Mariott, cook and femme de chambre. Balzac is never

happier than in his delineations of such faithful dependants,

forming members of a family, living and dying under an employer's

roof.

We are next introduced to the little society daily meeting in 'this

small Faubourg St. Germain of the department.' Inimitable,

Shakespearian, are these portraits, one and all etched with the

strength and sureness of Rembrandt. First we have M. Grimont, the

curé of Guérande, a man of fifty, 'in whom as he paced the streets

the most sceptical would have recognised the sovereign of the

Catholic town, but a sovereign whose spiritual supremacy yielded to

the feudal sway of the Du Guénics; in their drawing-room he was as a

chaplain in the company of his seigneur.'

Next to arrive for the nightly game of mistigri, [p.113]

or mouche, her servant lad lighting her with a lantern, is Mlle. de

Pen-Hoël, an elderly lady belonging to the first Breton nobility. She was rich, but her penuriousness was the wonder and at the same

time the admiration of folks living ten leagues off. She kept a

maid-of-all-work, a thousand francs sufficing for her yearly

expenditure exclusive of taxes. She used the crook stick of court

ladies of Marie Antoinette's time, as she walked; her keys, money,

silver snuffbox, thimble, knitting-needles and other sonorous

objects rattling in her capacious underpockets.

The Chevalier du Halga, another old Vendean warrior and pensioner of

the Restoration, made up the quartette. A loud military knock always

announces the Chevalier, who had once been of lionlike valour, was

honoured with the esteem of the famous bailli de Suffren and with

the friendship of the Comte de Portenduère. Of poor health, always

wearing a black silk cap and a woollen spencer, or outer vest, to

protect him against the sudden winds, no one would have recognised

the intrepid Breton sailor of former days. Never smoking or giving

way to an oath, gentle and quiet as a girl, his chief preoccupation

was his pet dog Thisbe.

For upwards of fifteen years this little company had played

mistigri together, one and all taking their departure on the

stroke of nine.

Béatrix is no simple, direct narrative, no poignant little

drama after the manner of Eugénie Grandet. Under fictitious

names Balzac gives us portraits of George Sand, Liszt, and minor

personages of his day. But these portraits hardly accord with what

we have elsewhere learned of the involuntary sisters. Nor does the

history of Béatrix and Calyste hold our attention or retain a place

in our memories. It is for its opening pages, for its immortal

reproduction of bygone types and characteristics that we take up the

volume again and again. As Sainte-Beuve has written:—'Balzac lived

through three epochs, and his work taken as a whole up to a certain

point is a mirror of each. Who better than he has described the

veterans and beauties of the Empire? Who has more delightfully

sketched the duchesses and viscountesses of the Restoration? And who

has given with more truthfulness the triumphant bourgeoisie

of the July Monarchy?'

I note without surprise that in a small volume of Balzacian

selections, occur two scenes from Les deux Poètes, one from

Eugénie Grandet, and the opening pages of Béatrix.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER IX.

BRANTÔME, THE HOME OF THE 'CHRONIQUE SCANDALEUSE'

'THERE is nothing

to see in France,' wrote Shelley three quarters of a century ago,

and apparently most folks are of the same opinion to-day. Such

at least is the impression conveyed by newspaper columns headed,

'Pleasure trips and conducted tours.' France does not figure

among the countries now brought within reach of the most hurried

travellers and most moderate purses—that is to say, France outside

Normandy, Brittany, and Touraine. But this prevailing

indifference accounts for the paramount charm of unfrequented French

provinces. We find region after region absolutely free from

cosmopolitan invasions; many 'a sweet recess' no less exempt from a

foreign element than in pre-railway times.

Such a spot is the island-town of Brantôme, in the valley of

the Dronne—none more idyllic to be found throughout Perigord.

Here pastoral charm and historic associations are combined.

Where, indeed, is historic interest absent from a French site?

The hotels at Périgueux, chief town of the department of the

Dordogne, are not engaging. My travelling companion and myself

were enamoured of the old city, its picturesque quays, its sweet

limpid river, its Byzantine cathedral, its noble statues of that

contrasted pair, Montaigne and Fénelon, its tempting bookstalls and

pretty promenades. But we could not, like Falstaff, take our

ease at our inn, so we steamed by tramway to Brantôme.

Very slowly and jerkily we plodded through varied tracts, now

in what looked like the remnant of a primeval forest, now across

barren wastes, now finding ourselves quite suddenly amid Theocritean

nooks.

The sense of solitude and space was hardly interrupted.

Enormous must be the area of uncultivated land throughout France.

Thousands of hectares, as yet untouched by the plough, we must have

passed on our way hither from Limoges. And during this two

hours' slow journey we passed hundreds, even more. How often

we longed to alight! For, relieving the aridity of steppe-like

tracts and gloomy woods, we got glimpses of little sunlit dales,

velvety swards, and purling streams, not all abandoned to Oreads and

Dryads. Here and there amid patches of hemp, lucerne, and

Indian corn, stood a cottage, herds grazing near, children's voices

coming as a surprise in such solitudes. The variety of foliage

was a thing to remember, that most graceful and uncommon tree, dear

to Alfred de Musset, the weeping-willow, being here seen to

perfection.

The approach to Brantôme recalls oriental stories, the

ghoul-like and fairy element being here closely associated.

The limpid waters of the Dronne now reflect not only richest

greenery and verdant banks, but between these lie strange dwellings,

caverns hewn into habitable shape. No monsters, however, live

in them; instead, the quietest, most affable peasant folk imaginable

tenant these maisons troglodytes, fantastic suburb of a

fantastic little city.

Next, a perspective of Italian aspect bursts upon the eye.

To our right rises the wide façade of the ancient Benedictine'

abbey, above it towering a lofty and ornate clock-tower; to our left

a promenade, bordered by a balustrade and flanked by two picturesque

old gateways, overlooks the river, thrice-bridged silvery stream

winding between old-world streets and luxuriant gardens; whilst

before us lies the scattered toweling with its one family hotel,

framing-in the whole, wooded heights and purple hills, the glorious

September sky heightening every charm.

Brantôme may be examined as a picture or a map, so compact is

this island-town and its sweet environment, so closely and

symmetrically does one feature neighbour its fellow. A perfect

picture it is, restful to the eye in colour and outline, yet

provoking curiosity and striking the imagination with a sense of

absolute novelty. Externally, Brantôme may be indeed

pronounced unique. Unwillingly travellers will quit the

sunshine for the purpose of archaeological exploration, here

antiquities yielding in attractiveness to a general view, the

harmonious grouping of contrasted objects, nature and art together

forming a chef-d'œuvre. Like Souvigny in the Allier and

La Charité-sur-Loire in the Nièvre, the town has grown round an

abbatial foundation, the origin of its importance and wealth being

purely ecclesiastical. The monks of the olden time lived after

the manner of feudal lords within their own walls and city gates,

and well did they know how to choose a site. The island-town

of Brantôme gave them all they wanted, a fertile soil, sheltered

aspect, water in abundance, and seclusion from the world.

The grand old campanile said to date from Charlemagne's time,

the abbey church and wide façade of the ancient monastery, form the

principal objects in the scene before us, every other feature being

subsidiary. Herein, indeed, is the history of Brantôme

symbolised, in itself nothing, its ecclesiastical foundation all in

all.

High above church and abbey towers the lofty and ornate

clock-tower, Brantôme's crowning glory. It is separated from

the church by a deep cleft in the rock or precipice, whilst the

church itself appears to form part of the rock on to which it is

built.

Singularity ever allied with charm characterises every

feature of this strange little island-town. Thus the lofty

campanile may be described as an anomaly; like the enchanted prince

of the Black Isles, half stone, half man, this tower is half tower

and half rock, its highly decorated stages of a hundred feet resting

on a rocky base of the same height, the upper portion only being

visible.

'Consummate art,' writes M. Viollet-Leduc, 'is shown in the

proportions and construction of this tower.' In 1373 it was

admirably repaired by an architect before-mentioned, M. Abadie.

The fine eleventh-century abbey church adjoins the wide

handsome facade of the ancient Benedictine monastery now used as a

mairie and museum. Both have been restored, but without

destroying the original stamp, and with the campanile form a most

imposing group or centre-piece to Brantôme regarded as a picture.

In that light we cannot help regarding it.

Flanking all three and stretching beyond are lofty parapets

of rock, bristling with brushwood and tapestried with green; the

lower portions have been caverned and adorned with quaint bas-relief

and sculptures.

As I always object to making a toil of pleasure and am the

most incurious traveller alive, I left these grottoes and galleries

unvisited. Some future wayfarer in the Périgord will doubtless

repair the omission.

Half a century ago the cloisters of the abbey existed,

although fast crumbling to decay. In 1859 a French writer

described this portion of the abbey as 'sombre, mysterious as death

itself.' On passing within we are seized with involuntary

trembling, an emotion partaking neither of fear nor horror but of

secret misgiving. Alone here on a dusky evening we seem to be

in a cemetery; the hoarse cries of night-birds, the mournful

dripping of water from the roof add to the horror. The

darkness, shadows, and wind-sounds seem to announce something

supernatural. It seems as if any moment, from the depths

around, ghosts might arise from their graves. So awful indeed

was the gloom of those dark galleries that they are said to have

suggested the operatic scenery of Robert le Diable, a

Parisian stage manager having come hither in search of suggestions

for the first representation.

Following the promenade with the palatial stone balustrade,

we reach the twin gateways, worthy porticoes of this dainty little

realm. Most elegant are both, but the one is so massive and

sober in detail, the other so graceful, lightsome, and ornate as to

suggest a sex in architecture, an idea of janitor and janitrix in

the builder's mind. Just below these remains of the ancient

fortification, we reach an old stone bridge, which seems suddenly to

have changed its mind, out of sheer caprice darting off at a

tangent. This is the pont coudé, or elbowed bridge,

aptly so called, its configuration resembling that of a bent arm.

The elbowed bridge, restored in 1775, was built by the monks in

order to get at their vegetable gardens on a lower level; market

gardens covering the area are still called les jardins des Pères.

From this part we make the circuit of the little town which

at every point is suburban and at every point recalls its

insularity. Here the mellow leafage of vegetables, the soft

tints of blue sky and rippling stream make charming, Italian-like

pictures. Indeed, from every side Brantôme reminds us of

ancient little Italian towns. No trace is there here of

commonplaceness or vulgarity; and the ineffable sense of repose!—the

little steam tramway, running through the town twice a day, speaks

of the outer world and of the universal modernisation going on

elsewhere. For in these captivating nooks and corners of

provincial France we seldom anathematise the speculative builder.

At Brantôme several mediæval houses offer tempting subjects to the

artist, whilst their romantic position sets them off to the best

possible advantage. Perhaps, indeed, a little more enterprise

in the matter of bricks and mortar would be welcomed by the most

fervent æsthete. Here, for instance, the fine old parish

church has been turned into a market-hall; used for the purposes of

public worship until the restoration of the abbey church in 1875, it

was then desecrated. One church, therefore, suffices for a

population of two thousand five hundred souls, but it seems a

thousand pities that marketers could not have been accommodated

elsewhere, and that a building of real architectural value and

interest should not be put in the category of public monuments.

If here we may fleet it carelessly as in the golden age, so

here like Falstaff' we may take our ease at our inn. There is

only one hostelry in the place, the Grand Hotel, or Hôtel Chabrol of

provincial celebrity. As far as passing travellers could

judge, a most comfortable house is this big, airy, spick and span

inn, its doors thrown invitingly open, its landlady buxom, blithe,

and debonair, ever ready for a chat, its exquisitely clean bedrooms

and aldermanic table to be had for five francs a day. Natural

products of all kinds—fish, flesh, fowl, and fruit—are superabundant

in this little El Dorado. For two francs per head we fared

upon trout, partridge—the month was September—and had the offer of

too many dishes to remember, our hostess and her daughter seeing to

our comfort in every particular.

A hundred yards from this hotel is a lovely walk by the

Dronne. Under the splendid avenue of lime-trees one might

spend whole summer days, so soothing the gentle ripple, so exquisite

the reflection of the pellucid waves. It is wonderful how much

the beauty of French scenery depends upon these small rivers.

Varied in hue, each winding through a different landscape, each

embellishing a little world of its own, tutelar genius of some

pastoral region, these streams and their affluents lend no less

charm than the great historic waterways, the 'chemins qui

marchent,' as Michelet calls them. And sweet as any are

the Dronne and the Corrèze that so caressingly encircle Brantôme.

But the numerous rambles and excursions within easy reach

offer very varied interest. While some spots are ideally

pastoral, others are wild and even savage. Ten minutes' walk

from the starting-point of the tram brings you to a dolmen, one of

those strange pierres-levées so-called, or table of rock

resting upon columns, by no means confined to Brittany, 'the land of

the Druid.' In another direction you come upon a natural

parapet, lofty cliffs recalling the sublime scenery of Fontainebleau

forest. Yet again, and you find yourself under the shadow of

serried alder-trees, at your feet the river set with tiny wooded

islets, a sylvan scene of flawless peace and beauty.

That great authority Joanne, indeed, pronounces the valley of

the Dronne to be not only the prettiest in the department, but

perhaps in all western France.

Brantôme, like all French towns, has historic interest, and

like many is linked with the history of national literature. Returning to the promenade facing the abbey church, standing on its

western point we are on the site of the vanished château in which

the titular abbot of Brantôme, Pierre de Bourdeilles, penned his

famous memoirs.

Brantôme, or Branthôme as some authorities [p.124]

call him, was, as one might well suppose, a Gascon, endowed with all

the traditionary loquaciousness and proneness to talk of himself. What we know about his life and character inspires liking not

unmixed with respect. Prosper Mérimée has happily hit off his

portrait in a sentence: 'Brantôme was a gentleman (un homme comme

il faut), or what was understood by the term in his own age.

Owing to birth, position, and character,' he adds, 'he was thrown

among the most noteworthy personages of his time, and his wit, high

spirits, and loyalty made him a general favourite. Hence his

unrivalled opportunities, and hence his authority in the manners and

customs of the sixteenth century.' The term un homme comme il

faut of course could apply in those days to the Cyrano de

Bergerac, D'Artagnan, swash-buckler type as to men of a quieter

order. The author of the so-called Chroinque Scandaleuse

never got adventure enough; his career, until stricken down by

infirmity, was one perpetual running to and fro in search of blood

and battle.

The substitution of Brantôme for his patronymic illustrates the

feudal nature of the French Church at that period. Pierre de Bourdeilles was sixteen when, on the death of his brother at the

siege of Hesdin, Henri II. named him abbé commendataire, or

titular abbot, 3,000 livres [p.125]

being attached to the fief.

Henceforth we hear of him at various courts and serving under chief

after chief. Strange as it may seem, even in those days of civil and

European wars his entire career as a free lance proved a

disillusion. Ill luck dogged his footsteps. He was invariably a

little too soon or a little too late for some brilliant enterprise

or famous encounter. There is something more than serio-comic, there

is a touch of pathos in such a story; it recalls that immortal

home-coming which should have been performed on a chariot drawn in

mid-air by gryphons, but which was instead a jolting over rough and

familiar roads in an ox-wagon.

In 1559 the seigneur abbot of Brantôme, now a dashing soldier,

figured in the brilliant Neapolitan court and was a frequenter of a

no less brilliant salon than that of Marie d'Aragon, Marquise

del Vasto, celebrated in her time alike for her wit and her beauty. A year or two later we find him in the suite of Mary Queen of Scots;

he accompanied her on her ill-fated journey to Leith, and afterwards

travelled to London, where he was enchanted by the beauty and lofty

bearing of Elizabeth. He next attached himself to the Duke of Guise,

and being an orthodox, but by no means bigoted Catholic, joined the

League, distinguishing himself at the sieges of Bourges, Blois, and

Rouen, and at the battle of Dreux. After the assassination of his

patron he entered the service of Henri d'Orléans, later Henri III. As a gentilhomme du roi, or lord in waiting, of that

unworthiest of unworthy Valois kings, he received wages amounting to

600 livres yearly. In those days the pay alike of courtiers and

civil magnates were called gages, or wages, as distinct from

the solde, or pay, of soldiers. The highest as well as the

humblest functionary received wages.

Later, Brantôme was despatched to Madrid where the French wife of

Philip II. received him with effusion, overjoyed to chat with a

countryman. Always agog for war, the seigneur abbot during the next

few years eagerly caught at every opportunity of losing an arm, a

leg, or his life. So insatiable indeed was his passion for hazard

and excitement, that, finding himself in middle life sound of limb

and without any military position, as he thought, commensurate with

his deserts or any likelihood of being thus rewarded in the future,

he meditated a perilous leap, in other words, the sacrifice of

honour and nationality.

The word patriot had not as yet been invented; in its actual

acceptation being first used by Voltaire. [p.127] With the fortunes of war, soldiers frequently changed not only their

chiefs but their colours. To Brantôme as to many another of his

time, provided he sniffed powder and found himself in good company,

the matter of flag was quite secondary. So embittered was his proud

spirit by what he considered neglect and ingratitude, that he seems

to have decided upon no less a step than that of offering secret

services to the King of Spain. Fate intervened. The generous

harum-scarum was saved from dishonour and literature was enriched by

an accident. Whilst still in the prime of life, he had just seen his

fifty-fourth birthday, he mounted a piebald, that is to say, an

ill-omened horse—we are assured that even in these days the

superstition remains—and was overthrown. The animal fell heavily

upon him, breaking both thigh-bones. For four years he lay in bed,

and to the end of his days remained a cripple and a suffering

invalid, the tedium of inactivity being relieved by his pen and a

succession of lawsuits. In litigation he seems to have taken as keen

a delight as in battles and sieges. One feature of this long and

painful confinement to his island-town throws pleasant light on

family life. He is said to have been tenderly cared for by his

sister-in-law, a widow of that brother killed at Hesdin just upon

thirty years before. On the other hand, Prosper Mérimée

mischievously insinuates that if Madame de Bourdeilles watched over

her infirm relation, the seigneur abbot as keenly guarded her

affairs, preventing her from contracting a second marriage and

thereby keeping the property together. The two positions are not,

however, incompatible.

Brantôme lived to be eighty; long before his death having been

forgotten by his contemporaries and the world. The celebrated

memoirs were not published till almost half a century later, and

then in a fragmentary condition only. Full of originality, wit,

charm, also of coarseness, these chronicles faithfully mirror the

times in which the writer lived. Modern research, moreover, has

greatly enhanced the historic value of Brantôme's works. It has been

shown by research that he relied on authentic French, Spanish, and

Italian sources for his statements of facts lying outside personal

experience, and despite his unblushing gauloiseries no

student of French history can afford to pass him by.

Here are one or two extracts, rendered into English. He is

describing Marguerite de Valois as she appeared in full splendour at

Blois, and the peroration may almost be set beside Burke's immortal

sentence on Marie

Antoinette. The future Queen of Navarre had proceeded to church on

the occasion of Easter—

'At sight of this procession we forgot our devotions, delighting

more in the contemplation of this divine princess than of holy

things, and deeming that thereby we committed no sin, since the

adorer of heavenly beauty on earth cannot surely offend the

Celestial Power, its Creator.'

A high compliment is here paid to the royal ladies of his time—

'A point I have noticed, with many great personages, both men and

ladies of the Court, that generally speaking, the daughters of the

house of France have always excelled and still excel either in

goodness, wit, grace, or generosity, and have been in all things

very accomplished, and in confirmation of this, not instancing those

of ancient or former times, but of those we have known or heard of

from our parents or grandparents.'

In a sentence he gives the key to his own character and success as a

writer of memoirs—

'I was often with him [Montluc] for he loved me greatly, and was

much pleased when I put him in the humour to be questioned; I was

never so young but that I had the utmost anxiety to learn. He,

seeing me in that

disposition, responded willingly and in choice language, for he was

very eloquent' (il avait une fort belle éloquence).

Nor can I refrain from citing this eulogium of the great Chancellor,

Michel de l'Hôpital, that anticipator of moral ideas to come, whose

whole life was a struggle for religious liberty, and who, although a

Catholic living in a time of fiercest theological conflicts,

promulgated the first edict of tolerance known in the western world.

'De l'Hôpital,' writes Brantôme, 'has been the greatest, most

learned, most dignified, and most large-minded (universal)

Chancellor, France ever had. In his person lived another Cato the

Censor, one who knew well how to censure and correct a corrupt

society. With his long white beard, his pale visage, his austere

expression, he might have sat for a portrait of St. Jerome. Thus

indeed some folks called him at court. To sum up; on his death his

enemies could not dispute this praise, that he was the greatest man

ever holding, or who will ever hold, the same position; so I have

heard them say, always all the same maligning him as a Huguenot'—which indeed Catherine de Medicis' great Chancellor was not. But he

was the author of the edict of Romorantin, he countenanced the

Protestantism of his wife and daughter, and he had uttered the

memorable speech: 'Away with those diabolical names, watchwords of

partisanship and sedition, Huguenots, Lutherans, Papists; let us

only keep the name of Christians!' The massacre of Saint Bartholomew

broke his heart.

The island-town figured in the religious wars, and one episode in

its history redounds to the honour of Coligny and also of the seigneur abbot. Although a partisan of the Guises, Brantôme was on

friendly terms with the great Huguenot Admiral. At the approach of

Coligny's forces in 1569, the population trembled not only for their

possessions but for their lives. Cruel reprisals and unspeakable

privations on both sides had rendered the soldiers ferocious. It

seemed as if the hour of doom was at hand. But Coligny enforced a

truce upon his followers, who were received rather as friends than

foes. Alike abbey and town were respected, and the raggèd troops

passed out of the place, poor as they had come. Not a loaf of bread

had been taken by force. Henry of Navarre, then a lad of sixteen,

was on this occasion lodged in the château.

Pleasant was a vacation holiday in this delightful spot, summer

hours dreamed away amid 'places of nestling green for poets made,'

no sound breaking the stillness but the notes of birds and the

purling of quiet streams. Farther afield, wild, romantic sites await

the hardy pedestrian, umbrageous solitudes, rocky defiles, silvery

cascades. And everywhere is felt that hardly attained, enchanting

sense of aloofness from everyday things, an escape from daily

repetition and a world without surprises!

――――♦――――

CHAPTER X.

PÉRIGUEUX, THE SAINT SOPHIA OF CENTRAL FRANCE

AS Brantôme is

reached by way of Périgueux and as this city of itself is worth the

journey from Paris, I add these descriptive pages. The capital of Périgord and chef-lieu of the Dordogne lies within a few hours of

Limoges and Angoulême on the Orleans railway.

We rub our eyes as we get the first view of its grand cathedral,

cupolas, and minarets towering above the ancient town and verdant

environments. East and west suddenly brought into juxtaposition, a

Saint Sophia rising in central France!

When, having quitted the railway, we stand under the shadow of that

mighty dome, we almost expect to hear the Muezzin's call, 'Allah is

great, praise be to Allah!' We seem to be in a second

Constantinople.

How came it about that such a structure should have been raised

here. By what caprice were French builders moved to raise a mosque

for Catholic worshippers?

If however at first sight the St. Front recalls the church of the

Holy Wisdom, on closer examination we discern more resemblance to

St. Mark's of Venice. A nearer inspection shows that this

second similarity is much slighter than we at first supposed.

Some authorities indeed consider the Périgourdin cathedral to be the

older of the two.

The general arrangement of both suggests an unmistakable Byzantine

origin. It seems moreover that St. Front and St. Mark were

constructed on the plan of the church of the Holy Apostles erected

by Justinian at Constantinople, and afterwards replaced by a mosque. A full description is found in Procopius and, according to

authorities, the Byzantine historians, at Venice and Périgueux we

have edifices raised upon a similar plan.

A French writer has pointed out that whilst in design St. Front

recalls St. Mark, in construction great essential differences are

found. The masonry of the latter recalls Roman methods as seen in

the baths of Caracalla, walls and domes being built of rubble and

cement and the outer surface surmounted with marble, gold, and

mosaic. St. Front, on the contrary, is built of stone, blocks being

superimposed, one on the other, with great technical skill and the

undecorated surface remaining austerely simple. The two buildings

differ in other respects. Following Roman tradition St. Mark has

round arches and spherical cupolas; St. Front, on the contrary, has

ogive arches and ovoid domes. The exact dates are of little moment. The interesting point to note is that of Byzantine origin as

suggested by the arrangement of pendentives and cupolas. [p.135]

St. Front occupies the site of a Latin basilica of the sixth or

seventh century, parts of which remain. The lofty clock-tower or

minaret is said to be the only one of its kind, i.e. pure Byzantine,

in existence. Externally the cathedral looks as if quite recently

built, the whole having been re-surfaced for the sake of uniformity. Within, an almost total absence of decoration immensely heightens

the grandiose effect.

The influence of this cathedral in Périgord, the neighbouring

province of the Angouois, and indeed throughout France was

considerable; round arches and domes being followed by great church

builders.

Périgueux may be described as tripartite, even quadripartite. It

possesses three distinct aspects, the Roman, the mediaeval, and the

modern, with traces of the Gallic.

Following a suburban road that winds leftward from the cathedral we

exchange Oriental and Venetian for classic associations, thus taking

a backward leap of many ages.

PÉRIGEUX―SAINT-FROND

CATHEDRAL

Before us, from the flat landscape, suddenly rises a lofty stone

rotunda recalling the Tomb of Cecilia Metella. But the name of this

monument commemorates an epoch anterior to the Roman occupation of

Gaul. Vesuna was the ancient capital of a Gallic tribe, the

Petrocorii or Petrogorici, hence Périgord. And in Celtic times Vesuna was a busy commercial city much frequented by Phoenician

traders from Marseilles, thus forcibly and constantly are we

re-reminded of the immense antiquity, the palimpsest upon palimpsest

of French civilisation!

This tour de Véone stands on what was the centre of the

Gallo-Roman city. Several theories concerning it have been

propounded. According to some authorities the massive circular tower

was a tomb, according to others, the principal part or cella

of a temple.

This superb monument has been rudely shattered, doubtless during the

religious wars that devastated Périgueux in the sixteenth century. The walls, six feet thick, are a wonderful specimen of Roman

masonry. A little farther on we reach a small beautifully kept

public garden. Here amid flower-beds and shrubberies stands another

Gallo-Roman ruin, the imposing remains of an amphitheatre.

Further still, we come upon a ruined sixteenth-century chateau which

was built upon a Roman basement, the modern portions being

incorporated into Roman brickwork, the most singular travesty

imaginable.

The Petrocorii were a valiant patriotic people, and had every other

Gallic tribe displayed a similar spirit, Cæsar's campaign might have

ended very differently. When shut up in Alesia the noble chief

Vercingetorix made a final appeal to his countrymen, and the

Petrocorii despatched five thousand men to his succour.

'It was a great misfortune for France and also for humanity in

general,' writes a French historian, [p.138]

'that Gallic civilisation, naturally incomplete but so curious and

original, should have thus been destroyed. Caesar's conquest imposed

upon us Latin civilisation, our ancestors being prevented from

showing what they could have effected by native genius stimulated

from without.'