|

LITERARY RAMBLES IN FRANCE

――――♦――――

CHAPTER I

FLAUBERT'S LITERARY WORKSHOP

THE summer-house

or pavilion in which Madame Bovary was written may well be so

styled. With a celebrated predecessor Flaubert regarded

novel-writing as no less of a trade than the making of watches.

But from an artistic standpoint only. Money, popular applause,

contemporary fame were not dreamed of in his philosophy. What

he aimed at and what by dint of superhuman laboriousness he

achieved, was literary excellence, the high water mark of style.

Hence it comes about that Croisset will ever be an interesting

literary pilgrimage. We may not find Madame Bovary

delectable reading, to some of us the so-called roman nécessaire

will prove 'thin sown with aught of pleasure or delight.' The

author's figure compels homage, the artist enlists general sympathy.

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT

(1821-80).

Picture: Wikipedia.

Despite his ingrained pessimism, Flaubert's life is a noble

lesson. From first to last, struggling against fell disease

and a melancholious temperament, manfully he went his way, no

obstacle damping his ardour, no checks, however mortifying, for a

single moment detaching him from his purpose.

Croisset lies three miles from Rouen and may be pleasantly

reached by steamboat. Hurried travellers will prefer to drive

and, once off the cobble-stones of the distractingly-paved city,

bowl along the quays agreeably enough. We pass an immense

stretch of bustling wharfage and warehouses, the river bristling

with masts and alive with smaller craft, the new bridge a beautiful

object amid much that is unlovely. As we advance on both sides

we have more taking scenes. Over against us rise dimpled green

slopes, and soon we come within sight of one long wooded islet

immediately succeeded by another—châteaux, farm-houses, and chalets

peeping between the trees of both.

My guide informed me that in 1875 these islets, were

ice-bound, the river being frozen. Many Rouennois have a tiny

cottage orné, or what is called a pavilion, here, in which they

spend their summer holidays. How delightful thus to be

islanded, shut off from the dust, glare, and turmoil of what is now

one of the most bustling commercial centres in France! Little

steamers ply to and fro, apparently the favourite mode of

locomotion, for every one we saw was crowded. Leaving the

quays behind we pass rows of handsome country houses and villas, all

with long flower gardens reaching to the road. Above these is

a background of wood and poplar groves. Croisset, reached in

about three quarters of an hour, consists of a long line of

scattered houses facing the river. The opposite bank is low

and featureless, a mere rim of yellowish green, but immediately

before Flaubert's eyes lay a lovely little island, truly—

'A place of nestling green for poets made.'

But alas! put to unidyllic uses in the pages of Madame Bovary.

Nothing in nature indeed can be prettier, more soothing, than

such a combination, from amid clear, sky-reflecting waters rising a

fairy kingdom, glades, woods and velvety swards of brightest,

freshest green. The river here broadens and, matching such

beautiful proportions, the landscape on one side takes a bolder

outline. Above the site of Flaubert's dwelling we gaze upon

richly wooded hills, chestnut, alder, and poplar here attaining a

great height, the latter trees often having a crest-like branching

out at the summit. This mass of woodland and the verdant

declivities running down to the road complete the picture.

Where formerly stood Flaubert's house is now seen a

dilapidated factory advertised for sale. The garden-house

however in which were written Madame Bovary and Salammbô

remains intact. Here too he wrote those delightful letters (an

expurgation here and there would not render them less so) to Madame

Louise Colet, George Sand and others.

The original dwelling with its acre or two of garden must

have represented the handsomer kind of campagne or French

country house. The entire property was sold by Flaubert's

niece and heir, and on the site of the demolished dwelling a factory

was built, this also being destined shortly to disappear. But

a little knot of ardent admirers have succeeded in getting together

enough money to purchase the pavilion, which is to be turned into a

memorial museum. A bit of ground has also been obtained, so

that the little building will soon stand amid flowers and shrubs.

The long avenue of lime-trees, destined, as Flaubert wrote, for 'graves

et douces causeries,' has of course disappeared long ago.

The garden-house consists of a single room of commodious

proportions, overlooking highway, river, wooded islet, and low-lying

banks.

Doubtless, the road beneath his windows was much less

frequented sixty years ago than it is today, but noise and dust

there must have been. In every other respect no author could

desire a more seductive retreat.

Yet these walls remind us of the most painful literary

labours on record. Flaubert was a veritable Sisyphus, and

miraculous it seems that he ever accomplished his self-imposed

tasks, above all, that from such agonising throes should have

emerged living creations and a masterpiece! Toilsomely as

Jacob wooed his brides, Flaubert wooed the creations of his fancy,

in his case being no difference between Leah and Rachel, his

literary wooings never inspired by love or admiration.

A septennate was given to the composition of Madame Bovary,

another to L'Éducation sentimentale, only a year or two less

to Salammbô.

'I have just copied all that I have written since the New

Year,' he wrote to Louise Colet, 'thirteen pages in seven weeks,

neither more nor less. At last they are done and as perfect as

I could make them.'

In this charmingly situated workshop he would literally

entomb himself, only the sound of his own voice from time to time

breaking the silence. It was his habit, and an excellent one

without doubt, to read and re-read aloud every newly framed

sentence. Old folks at Croisset still remember those clear

strident utterances, on dark winter nights his lighted window

guiding fishermen and sailors as a beacon.

In search of the right word, with Boileau he could have said,

je cherche and je sue, and the seeking and sweating

went on with results more or less successful throughout his life.

We are told that the occurrence of two genitives in the phrase

une couronne de flears d'orangers disturbed him greatly; he

wondered how he could have committed such a crime. Paragraphs

were often re-written half a dozen times before being set aside as

perfect as literary carpentry could make them. The typical

phrase in Flaubert's writings, has said one critic, resembles a

symphony having an Allegro, an Andante, and a Presto rhythm,

sonority, completeness, all the qualities necessary in verse.

Flaubert wanted to 'give prose, leaving it prose, the systematic

construction of verse,' he wrote to Louise Colet, 'perhaps an absurd

undertaking, but it is a fine, an original experiment.' The

experiment occupied his days and nights.

Nor was he less careful in the matter of punctuation.

Like the great humorist of Samothrace he paid the utmost attention

to stops; commas, he called the vertebrae of a phrase, and in the

use of them was a pronounced master. Little wonder that under

these circumstances composition went on at a snail's pace. Nor

need we feel astonished at the utter joylessness with which the

self-imposed tasks were got through. 'You have no notion,' he

wrote to his friend, George Sand, 'what it is to sit throughout an

entire day with your head between your hands, beating your

unfortunate brains for a word. With yourself ideas flow

copiously, unceasingly as a river. In my own case they form a

narrow thread of water. I have herculean labours before me ere

obtaining a cascade. Ah! the mortal terrors of style, I shall

have known all about them by the time I have done.'

One inevitable result of such fastidiousness was compression.

Take, for instance, the oft-cited description of Rouen seen from the

heights of Boisguillaume in Madame Bovary. This

incomparable passage of ten lines originally filled a page.

Six revisions reduced it to a sentence, not a single idea having

been lost in the process!

Presentment made him no less of a galley-slave. The

horrible death-scene in his famous novel was the result of

application so close and conscientious that, having poisoned his

heroine, Flaubert himself felt all the symptoms of poisoning.

Have not folks been said to die of imaginary hydrophobia, even and

small-pox, before now?

If in realistic presentment Flaubert always succeeds, so much

cannot be said of his descriptions. These are not always

crystal clear.

In his history of French civilisation, M. Rambaud alludes to

the cap worn by Charles Bovary as a schoolboy, the head-gear of

youth worn in Louis Philippe's time. But on reading and

re-reading Flaubert's elaborate description I cannot for the life of

me conceive what poor Charbovari's cap was like. An

illustrator of the scene would probably be in similar case.

If, which is very likely, the description of Charles Bovary's cap

occupied Flaubert many hours, maybe days, we must remember that he

was no Issachar weighed down by a double burden. Throughout

his literary career he was able, in the noble words of Schiller,

having 'achieved a chef d'œuvre, to cast it without a second

thought on the waves of Time.'

If literary conscientiousness gave tormented days and

sleepless nights, from other cares he was free. Ample means

allowed him to do his best, to give as many days as he pleased to a

single page. His career was an instructive comment on Dr.

Johnson's dictum that no one but a fool would write except for

money. Flaubert's earnings must have been meagre, but the

imperishable harvest was rich indeed.

Volumes have been devoted to Flaubert's style and method.

It is not surprising that Montesquieu and La Bruyère were his

models, Fénelon and Lamartine his detestations. The superfine,

the chiselled phrase à la Goncourt he ever avoided; honeyed

sweetness, la phrase molle as exemplified in Télémaque

and Graziella, he positively loathed. What he strove

after and attained was the virility, precision, and strength of the

great seventeenth-century masters.

Of his half dozen works which will live? All were

written, as he said that authors must ever write, for eternity.

'But the people's voice, the voice and echo of all human fame?'

What will posterity say?

The rank of Madame Bovary in French literature seems

assured. Only twenty-five years after the author's death one

character out of that unlovely portrait gallery has become a

household word. In the chemist of Yonville, Flaubert has

created a type, added yet another figure to the list of literary

creations.

'You ask my opinion of Flaubert,' said a French critic to me

the other day. 'My reply is, he created Homais.'

'I reproach myself sometimes,' wrote Renan (Souvenirs de

Jeunesse), 'for having contributed to M. Homais' triumph over

the curé. What would you have? M. Homais is in the

right. Without M. Homais we should all be burnt alive.'

The vain, meddlesome, half-educated, would-be Voltairean and

encyclopædist, the great little man of the country town, may not at

first strike English readers. Familiarity with French

middle-class life is necessary for an appreciation of such a

portrait. Our neighbours now cite Homais as we speak of

Podsnap or Micawber.

Flaubert's contempt and dislike of the bourgeoisie,

whether sincere or affected, was a fashion, an epidemic in his day.

But surely it is strange that belonging as he did to the same class,

surrounded as he was by admirable types, he should have neglected

them for all that was mean, poor-spirited, and odious. With

the exception of Dr. Larivière, Madame Bovary gives us the

bourgeois bereft of every redeeming quality.

Foresight, thrift, family affection, the virtues that may be

said to have built up a nation, with one exception are absent from

the picture. In the hospital doctor, 'belonging to the great

school of Bichat,' Flaubert portrayed his father, 'who pursued his

way full of debonnaire dignity, imparted by the

self-consciousness of distinguished talent, fortune, and forty years

of a laborious and honourable career.'

Madame Bovary, strange as it may seem, was

the subject of a criminal trial on the score of its immoral

tendencies, Flaubert emerging victorious. The result could

hardly be otherwise, since from first to last the novel portrays the

disillusion of vice.

Tastes may differ concerning Salammbô, which George

Sand found unreadable, also concerning L'Éducation sentimentale.

With regard to Bouvard et Pécuchet there can be but one

opinion, that it is the dreariest farrago ever penned by genius.

And when all is said and done, many readers will doubtless prefer

Flaubert the letter-writer to Flaubert the novelist. No more

delightful letters exist in the French language. His

outpourings to the chère muse, the beautiful, eccentric, and

talented Madame Louise Colet for whom Maxime du Camp composed the

following elegy:—'Here lies Louise Colet, who compromised Victor

Cousin, ridiculed Alfred de Musset, illtreated Flaubert, and tried

to assassinate Alphonse Karr. Requiescat in pace.'—

adored by him so reluctantly, are the best preparation for this

literary pilgrimage. As we read, we realise the existence led

within these walls. Future visitors will find a fillip to the

imagination. Manuscripts, portraits, and other memorials are

being put together and will form a most interesting little temple of

fame.

Regretfully I tore myself away from the scene of Flaubert's

labours, and the picture on which his eyes daily rested, meandering

Seine, low-lying banks, narrow islets, with their wind-tossed trees

and steamer succeeding steamer, only the mast and funnel being

visible 'as in the background of a theatre.' Such experiences

bring home to us an author's personality as no mere study of his

works, however persistent, can do.

I was driven back to Rouen by another road, or rather by a

country lane. Here were hedges bright with purple loosestrife,

saponaria, agrimony and other late flowers; soon rows of suburban

villas, each standing in a garden, each unlike its neighbours,

announced the town.

On joining a French literary friend at Meudon I found that

she had seen Flaubert, and the glimpse given of him by this lady is

highly suggestive.

'Once, and once only I saw the author of Madame Bovary,'

she said; 'at that time in the prime of life and in the zenith of

his fame. Although physically afflicted throughout his entire

life, being, as you know, subject to epileptic seizures, Flaubert

possessed the figure of an athlete and was remarkably beautiful.

'With a few, a very few, highly-favoured admirers I was

invited to a reception given in his honour by Madame de A—. It

was late when a thrill ran through the assembled company.

Flaubert had arrived! Fastidiously attired in the most

approved style of evening dress he made his way to his hostess,

addressed to her a few courteous words, shook hands with this

acquaintance, bowed to that, then like a phantom, a meteor, vanished

quickly as he had come. Not one of us got so much as a word

from him, and in my case, the opportunity never occurred again.'

Tall, broad-shouldered, with a flowing beard of pale auburn,

eyes described by one who knew him as of the colour of the sea, all

the beauty of northern races, wrote another friend, was represented

in his person.

His behaviour at the evening party just named must be set

down to anything rather than vanity or the desire of posing.

He called himself a hermit, a literary monk, and conventional

society he ever avoided, reserving himself for his mother, his

niece, and his friends.

A gloomier childhood than his it is hard to conceive.

Son of a physician attached to the municipal hospital of Rouen, his

boyish years were spent within its gloomy precincts, daily

experiences familiarising him with pain, sickness, and death.

Little wonder that, subject as he was to a distressing infirmity, he

became a confirmed pessimist. His otherwise delightful letters

are a perpetual reiteration of the preacher's text: vanity, all is

vanity.

Flaubert's father died in 1846, and Madame Flaubert removed

to Croisset, henceforth the novelist's home for the rest of his

days. Brief sojourns in Paris, travels in Brittany, the

Pyrenees, Italy, the East, and Tunis, in his declining years a

flying visit with Tourgeneff to George Sand at Ushant, formed the

only breaks in a singularly uneventful life. The loss of an

only sister, later of a boon companion and friend, saddened him to

his dying day. Family affection and friendship, indeed,

satisfied his heart. Of passion he seems only to have known

the disenchantments.

Between his mother and himself existed the closest ties of

love and confidence. To her as to a comrade he poured out his

innermost thoughts; 'dear old thing,' he called her in the two or

three letters that remain of their correspondence. The pair

were indeed seldom separated, and, if the tenderest mother possible,

we gather that she was also one of the most exacting. If

Flaubert was indeed a typical French son, devoted, submissive,

yielding on every point, Madame Flaubert seems to have been a

typical French mother, regarding the grown-up, even middle-aged, son

as completely her own as when a baby in arms. 'She loved him,'

writes one of his biographers, 'with the devotion that not only

binds but crushes. [p.14]

It was on her account that he became a stay-at-home. In order

to please her he was very near throwing up his Eastern journey at

the last moment. His briefest absence filled her with anxiety.

Of his art she understood nothing; at first jealous of it, she

became reconciled to a pursuit that kept him at home. The last

years of his life were very sombre for both. She could think

and talk of nothing else but her own health, and Flaubert's

principal occupation was to make her take little turns in the

garden.' Her death in 1872 proved a tremendous blow. A

few days after the event he wrote to George Sand: 'I have discovered

within the last fortnight that that poor good woman, my mother, was

the being I loved best in the world. It is as if I had lost a

part of myself.'

Flaubert, who despised the bourgeoisie, essentially

belonged to it; in him the homelier national virtues were

conspicuous—strong family feeling, utter freedom from pretence, and

strict probity in all practical matters. We must live like

bourgeois and think like artists, he used to say, a maxim he carried

out.

Amiably nepotious, as are most French bachelors, Flaubert not

only made an idol of his niece, but also undertook her education,

his methods, as might be expected, being highly original. The

history lesson consisted of an impromptu narrative delivered by

himself which next day the pupil had to repeat, the repetition being

followed by questions and comments. 'In this fashion,' Madame

Commanville tells us, 'I acquired a knowledge of ancient history,

sometimes puzzling him with my questions; for instance, Were

Cambyses, Alcibiades, and Alexander good men? What is that to

you, he would reply; well, not perhaps exactly nice. I was

disappointed not to have more details, I expected him to know

everything.

'Geography I never learned from books either. Children

should learn from pictures, he said. Thus, in order to make me

understand what was meant by an island, a promontory, a bay, and so

forth, he would take a spade and give me object-lessons in the

garden. As I grew older these daily lessons became longer, and

they continued till my marriage at the age of seventeen.'

His little Caroline was indeed to him a daughter, and as we

shall see there was no sacrifice he was not prepared to make for her

happiness. Flaubert was also a devoted friend, the loss of

several boon companions afflicting him greatly. During his

short residence in Paris from 1840 to 1844 he was an habitue of

Pradier's studio, there meeting De Vigny, Jules Janin, Leconte de

Lisle, Victor Cousin, and other leading spirits. But it was

Dr. Cloquet, at that time a foremost anatomist and clinical

lecturer, whose acquaintance most influenced the future author of

Madame Bovary. The novel could only have been written by

one who had made medicine a special study, and we learn that Dr.

Cloquet introduced him to the most eminent of his medical brethren.

Flaubert was thus able to pursue his favourite subject,

unconsciously laying the foundation of his lifework and his fame.

His friends we learn to know in those charming letters, his

favourite books also. A finer literary taste no writer ever

possessed, yet his exceptions sometimes come with a little shock.

Fénelon and Lamartine were put on the index, George Sand he found

delightful as a friend but unreadable as a romancer, and De Musset

he set down as a great poet but no artist. Béranger, Thiers,

Augier were bourgeois writers, who wrote for bourgeois

readers; Sainte-Beuve fared at his hands as did George Sand: the man

pleased, the critic was insufferable. Sully Prudhomme he

damned with faint praise, Shakespeare he adored, but neither Dante

nor Goethe seems to have been a god of his idolatry. The Greek

dramatists and one or two Latin authors, Rabelais, Montesquieu,

Montaigne were daily pasture; to Spinoza at three different periods

of his life he returned with zest. Ronsard he 'discovered' in

1852. Herbert Spencer won his suffrages.

Sad was the close of a uniformly honourable career, sad and

very French! A Frenchman's family is ever part of himself; no

Frenchman owning kith and kin however remotely related can be

regarded as a unit, for good or for evil he is member of a clan.

Thus it came about that when the husband of his much-loved niece was

on the verge of ruin, Flaubert flew to the rescue. Without a

second's hesitation—at that time being elderly and in failing

health—he sacrificed his entire fortune in order to avert the

catastrophe. The sum-total of several hundred thousand—some

say a hundred thousand—francs was as nothing in French eyes by

comparison with the loss of family honour. If bankruptcy no

longer entails the pillory and the green cap with steps of the

Bourse, forfeiture of civil rights and banishment as under the first

Napoleon, it is still high treason, mortal sin as in the days of

César Birotteau. But the famous author of Madame Bovary

could not be left to starve. The librarianship of the

Bibliothèque Mazarine, bringing in just three thousand francs a

year, was awarded him. He survived the nomination a few months

only, dying in 1880, his end doubtless being hastened by anxieties,

unhygienic habits, and persistent self-neglect. For days, even

weeks at a time, he would shut himself up in his garden-house, not

even the avenue of favourite lime-trees tempting him abroad.

To his manuscript, like Lear, he was bound as to a wheel of fire.

Since these pages were written, that is to say, on the 17th

of June of the present year, 1906, the Pavilion Flaubert was

inaugurated with much ceremony and handed over to the city of Rouen.

Many interesting mementoes of the novelist have been laboriously got

together: an alley of lime-trees has been planted on the site of his

favourite walk, a tulip-tree, a rose bush and a root of honeysuckle,

occupy the exact spot of former favourites. The Pavilion

Flaubert therefore wears a very different aspect to that seen by me

nine months before. Two monuments memorialise Flaubert in his

native city, one adorning the museum of the Jardin Solférino, the

other, the walls of the École de Médecine, both having portraits in

bas-relief.

And this year has been published a volume which not only

reveals the character of the man in its entirety but is a revelation

of French national character. [p.19]

Not only Flaubert—all France—lives in its pages, the France, not of

fiction, but of real life, with all its homely lovingness,

amiability and self-devotion.

Few readers, I presume, will be at pains to peruse the three

hundred and ninety letters to his adored niece Caroline, some of

these the merest scraps, only a caress on paper, covering a period

of thirty-four (Ed.—sic) years. The first, dated from

Paris, April 25, 1856, compliments his dear Lilinne—as he goes on he

finds a score of pet names for his darling—on her improved spelling,

and speaks of a new doll which is impatiently awaiting the journey

to Croisset and new clothes. The last was written from his

Rouen home on May 2, 1880, just six days before his death, and is in

a characteristically pessimistic strain. His Loulou's pictures

have been badly hung in the Salon and he has suffered shabby

treatment at the hands of a publisher. 'This is how one is

always treated by these people,' he writes bitterly; 'the contrary

is quite exceptional.'

There is very little literature in these five hundred and odd

closely printed pages. From this point of view the letters to

his Caro, his Loulou, his Carola, his bibi, his bichon,

will not bear comparison with those previously published. The

interest of the volume lies elsewhere. For, in thus portraying

himself, Flaubert portrays the real Frenchman to whom family life

and family affection stand before every other earthly good.

In the melancholy days following Sedan, after an outburst of

despair concerning the national outlook he concludes with: 'But I am

ungrateful to Heaven, since I shall have my poor Caro.'

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II

THE STORY OF THE MARSEILLAISE

NEVER was the

irony of fate more conspicuously displayed than in the history of

Rouget de Lisle, never did splendid renown suffer completer eclipse.

When, stricken in years and broken in health, the pensioner of

Louis-Philippe died at Choisy-le-Rol, the announcement aroused no

interest. The poet-musician who had sounded the clarion note of

revolution, imbuing peasant lads with the spirit of Lacedaemon, was

utterly forgotten. Could he have lived, as do many, to be a

nonagenarian, how would he have electrified the Paris of Lamartine

and Victor Hugo, the France of '48! By comparison the apotheosis of

Voltaire would have faded into insignificance. Who can say? Had such

a span been accorded to Rouget de Lisle, the Second Empire and Sedan

might have been averted, France might still rejoice in her Rhine

provinces. It was not to be. He died in 1837, just a decade too

soon.

With its author, the most famous song in the world had been

condemned to oblivion. Like the genii of Arabian story, the

Marseillaise was long hermetically sealed, on its deliverance from

prison proving a greater miracle-worker than the guide to the

enchanted lakes. The trumpet-call of 1792 became the rallying

cry of democratic France, the watchword of the great western

republic.

From another point of view Rouget de Lisle's story is equally

strange. The efflorescence of this strange genius remained

single, unique, neither bud nor blossom keeping its one glorious

outburst company. Voluminous composer, novelist, song-writer,

vaudevilliste, with a solitary exception Rouget de Lisle's

works are as completely forgotten as if they had never been.

He lives in an impromptu durable as the language in which it was

hastily jotted down.

Claude-Joseph Rouget, afterwards self-styled de Lisle, was

born at Lons-le-Saulnier, Jura, on the 10th of May 1760.

Perhaps no part of France is less familiar to the English tourist

than Franche-Comté, the country of Victor Hugo, of how many other

great names in art, literature and science, and of how many historic

associations! It is, moreover, in these eastern highlands, to

quote Ruskin, that 'a sense of great power is beginning to be

manifested in the earth, and of a deep and majestic concord in the

long, low line of piny hills, the first utterance of those mighty

mountain symphonies soon to be heard more loudly lifted and wildly

broken along the battlements of the Alps.'

Ruskin wrote of Champagnole lying ten miles further eastward,

but the mighty mountain symphonies begin to be heard at

Lons-le-Saulnier. In clear weather Mont Blanc may be descried

from the wooded height of Montciel above the town, crowning feature

of a majestic panorama.

Lons, as the chef-lieu of the department is familiarly

called by residents, when I first knew it twenty-five years ago, was

a cheerful, artistic little town, nothing more. It has now

become a fashionable inland spa, its valuable mineral springs

attracting large numbers of valetudinarians: hotels, casino, and

concert-rooms forming quite a new quarter. More than one

pleasant autumn have I spent under a French roof here, on the

occasion of my latest visit finding many changes. In one

respect, however, I found no difference. Despite modernisation

and natural attractions, the English and American tourist had not

discovered Lons-le-Saulnier. The brilliance and sublimity of

Franc-Comtois scenery, its underground marvels, glittering cascades,

lovely little lakes, and frowning donjons, piny solitudes and

pastoral vales, remain unknown to my travelling compatriots.

The young military engineer who revolutionised France with a

song, was born in the house now numbered twenty-four of the ancient

Rue des Arcades, that picturesque street recalling the Spanish

régime of Franche-Comté. A delightful lounge alike during

winter and summer is this long stretch of covered galleries, and

many towns hereabouts are similarly embellished.

Rouget is a very usual patronymic in this part of France, and

the aristocratic de Lisle, belonging to some ancestor on the

paternal side, was adopted as a matter of necessity. The

Rouget family were bourgeois, Claude-Joseph's father being an

Avocat de Parlement. Unprovided with the particle, the

young man would not have been admitted into any military academy,

such schools being exclusively reserved for youths of the

noblesse.

Like most of the well-to-do professional classes in France,

formerly as nowadays, the Rouget family possessed their country

house and small landed property. Travel was out of the

question. Then, as to-day, the long vacation was mostly spent

by lawyers and notaries on their modest ancestral domain. Till

his dying day Rouget de Lisle's fondest memories clung to the

paternal home at Montaigu, a suburban village, a mile and a half

from Lons-le-Saulnier. One bright September afternoon I set

off for the spot with my host, a Protestant pastor, and his little

daughter, who carried a basket of grapes with which to refresh

ourselves on the way.

The neighbourhood of Lons-le-Saulnier abounds in delightful

walks, the half-hour's climb among the vineyards to Montaigu being

one of the prettiest. As we ascended we saw magnificent views:

to our right lay the vast plain of La Brasse, now dim and blue as a

hazy summer sea; to our left rose the Jura range, dark purple

shadows flecking the green slopes, standing out boldly on isolated

peaks the donjons of Le Pin and Montmorot, and the ruined chateaux

of L'Étoile and Bornay, whilst at our feet lay the pretty little

capital of the Jura. Although we were midway through

September, and the air was keen, a hot sun poured down upon the

vineyards.

In these days numbering seven hundred and odd souls, Montaigu

at one time possessed considerable importance. In the eleventh

century like a watchdog it kept guard over the valuable springs of

Lons-le-Saulnier, Étienne, Count of Burgundy, having turned the

place into a fortress. Nothing worth mentioning remains of

feudal Montaigu to-day, but its aspect is old-world, not to say

antiquated, and little changed since Rouget de Lisle was rocked in

his cradle, just upon a century and a half ago.

The village street is picturesque, if not on the whole

suggestive of comfort. To each deep red roof are attached

corner pieces for letting off the snow, which often falls in

terrible superabundance in the Jura. During the bitter winter

of 1870-71, indeed, wolves could be seen prowling by daylight around

these suburban villages!

At the time of my visit there was nothing to distinguish

Rouget de Lisle's birthplace from its neighbours but a handsome iron

gateway, or rather door. No tablet commemorated the 10th of

May 1760. Looking through that doorway and beyond a small

courtyard, we saw a modest but substantial bourgeois dwelling

with iron balcony, the whole suggesting respectability and easy

circumstances.

A marble inscription now arrests the attention of passing

travellers; a second ought to be added, that to a dog deserving a

niche among historic hounds.

But indeed for the country lawyer's good house-dog, the world

might never have heard of Rouget de Lisle and the Marseillaise.

When a child of three or four, Montaigu and its neighbourhood was

infested with foreign gipsies. The little fellow at this early

age seems to have showed the daringness characterising his entire

career; having strayed beyond the home premises he was popped under

the cloak of a crone. Already she had reached the extremity of

the village street when the barkings of the faithful dog alarmed the

household. One and all rushed out; the child was hastily set

down, his would-be kidnapper beating a hasty retreat. Another

fright he gave his family when six years old. One day a

company of strolling musicians gave a concert in the village, and so

fascinated was he by the music that he followed the band as they

marched away, playing as they went. On being brought back and

scolded, he excused himself thus: 'O Mamma, I do love you, but they

played so beautifully!'

The family was musical, and at this period the violin enjoyed

especial vogue. At an early age Claude-Joseph took lessons on

the instrument from a local master, his musical education, however,

never having passed the elementary stage. Of harmony he

learned little.

As we survey the beautiful environment of Montaigu, its

vine-clad slopes and majestic perspectives, we can understand Rouget

de Lisle's passion for his childhood's home. 'The first

utterance of those mighty mountain symphonies soon to be wildly

lifted along the battlements of the Alps,' of which Ruskin speaks,

awoke an echo in his turbulent nature.

As we shall see, neither wedded love nor the domestic

affections brightened his stormy career. Of friendship he

fully tasted the solace, but his tenderest recollections clung to

Montaigu, the corner of France no less endeared to him by childish

associations than by natural charm. 'Thine were my first

affections, thine my last regrets,' thus pathetically he

apostrophises the place in his latter years. To the 'séjour

charmant de mon enfance' he consecrated touching words and plaintive

melodies. And Montaigu, the dearly cherished home and paternal

estate, with everything else that he prized, was destined to slip

through his fingers, become a thing of the irrevocable past whilst

he yet lived and felt stirred by the ambitions of youth!

II.

On the 25th of April 1792, Rouget de Lisle was a guest at the

historic banquet given by Baron Friedrich Dietrich, first Mayor of

Strassburg.

The brilliant young military engineer had already attained a

certain notoriety as novelist, poet, musical composer, and

dramatist. One of his pieces had even been produced at the

Ópera Comique, and the celebrated musician Grétry had accepted his

collaboration in several works now forgotten. As was the

fashion among young gentlemen of the period, he had composed

innumerable society verses, besides throwing off sentimental

romances.

Rouget de Lisle's early ambitions would appear to have been

by no means those of a soldier. Had success crowned these

versatile efforts, his career would doubtless have been very

different. France might perhaps have wanted her Marseillaise,

but the poet and musician of Lons-le-Saulnier might have fared after

happier fashion.

A few words about this memorable dinner and the young

captain's hosts and fellow-guests.

The banquet, although unofficial, was eminently a patriotic

manifestation. A few days before, the Legislative Assembly had

declared war against Austria and Prussia, in other words, against

the coalition of émigrés and foreign powers formed for the

restoration of absolute monarchy. Threatened with the fate of

Poland, France answered the summons to submission by a general call

to arms.

In Strassburg excitement was at fever pitch. Alike the

king's oath to maintain the constitution and the declaration of war

had been enthusiastically acclaimed. A religious ceremony in

the Cathedral, a grand musical celebration in the open air, banquets

to the agèd poor and orphans, celebrated these events, the day

winding up with Dietrich's great dinner of farewell. The

unfortunate General Luckner had been named Commander of the Alsatian

forces; on the morrow officers and volunteers would be on the march,

many with little likelihood of meeting again.

The first Mayor of Strassburg, as he is known in history, is

an ingratiating figure. A cultivated gentleman and high-minded

citizen, the friend of Turgot and Condorcet, he had welcomed the

Revolution, but from a monarchical point of view. With Arthur

Young's friend, the amiable Due de Liancourt, and many others, he

believed in the possible establishment of constitutional monarchy.

To Dietrich's cost he believed the word of Louis XVI. Hence

his growing unpopularity among the more violent faction at

Strassburg, hence the swift waning of his once immense and deserved

popularity, and tragic end.

Just now the Dietrich salon (early in 1792) was the centre of

all that was most public-spirited and refined in the city.

Both husband and wife were accomplished musicians, and the former

possessed a magnificent tenor voice. Their two sons, Friedrich

and Albert, both volunteers in the army of defence, were present at

the dinner. Among the guests were the generals in command,

Desaix, the future hero of Marengo, other officers and a few leading

citizens. The hostess and two young nieces seem to have been

the only ladies present.

Little wonder that under the circumstances conversation took

an entirely martial turn. Marches, battles, the chances and

fruits of victory formed the sole topic of conversation. The

words 'Enfants de la patrie,' a name given to the younger Dietrich's

volunteers, 'Aux armes, citoyens!' 'Marchons,' and other phrases

were on every lip, emphasised many a sentence. Champagne

circulated freely, voices became more impassioned and vociferous,

and as it was then the fashion in France, as it is still, for ladies

to remain at the table to the last, Madame Dietrich and her nieces

interposed. Could not something else be discussed?—they had

heard enough of campaigns and wars.

Then patriotic songs were mentioned. Might not some

substitute be found for the jingling 'Ça ira, ça ira'? Could

not some one compose a hymn for the army of the Rhine, General

Luckner's brave followers? The host's first notion was of a

publicly advertised competition, of offering a prize for what should

be not only a war-song, but become a national hymn. Then,

another thought having struck him, he turned to the young military

engineer.

'But you, Monsieur de Lisle,' he said with charming

insinuation and persuasiveness, 'you who woo the Muses, why should

not you try to give us what we want? Compose, then, a

noble song for the French people, now a people of soldiers, and you

will have deserved well of your country.'

Rouget de Lisle tried to excuse himself, but alike host and

fellow-guests would not hear his deprecations. Again the

champagne passed round, and just as at last, amid tears, smiles, and

passionately patriotic farewells, the party broke up, a

fellow-officer, about to quit Strasburg next day, begged de Lisle

for a copy of his forthcoming song.

'I make the promise on behalf of your comrade,' Dietrich

replied with affectionate authoritativeness.

In a state of tremendous surexcitation Rouget de Lisle

reached his lodging close by, but not to sleep. His violin lay

on the table. Taking it up, he struck a few chords. Soon

a melody seemed to grow under his fingers, harmonising with the

words that had been reiterated throughout the evening, 'Aux armes,

aux armes, citoyens, marchons, formez vos bataillons!' No

sooner had he gripped his air, and put down the notes on paper, than

he dashed off the words. Thus having in a brief hour secured

for himself an undying name, he threw himself upon his bed and

slumbered heavily.

III.

In his declining years, Rouget de Lisle would ofttime narrate

the genesis of the Marseillaise to friends and acquaintances, memory

sometimes playing him false in immaterial particulars. Again

and again he told the story, among his listeners being the

celebrated painter David d'Angers.

The following version is now accepted as substantially

correct. On awakening next morning, his eye immediately rested

on the composition of a few hours before. After glancing at

verse and melody, early as was the morning, the clock had just

struck six, he hurried off to a fellow-officer and guest of the

night before, who in turn hurried him off to the Mayor's. The

young men found Dietrich strolling in his garden.

'Let us go indoors,' he said; 'I will try the air on the

clavecin, [p.33] and shall

be able to tell at once if it is very good or very bad.'

Dietrich, true musician as he was, unhesitatingly anticipated

the verdict of posterity. All the available guests of

yesterday were again invited to dinner; he had an important

communication in store for them, he said. During the banquet

his secret was carefully withheld. The party having adjourned

to the salon, one of the young ladies opened the clavecin,

and the Mayor's magnificent voice thundered forth:—

'Allons, enfants de la patrie,

Le jour de gloire est arrivé.' |

The audience was electrified. Forthwith copied and

distributed to local bands and musical societies, the song acted

like a charm. Hitherto enrolling themselves by twos and

threes, the youth of Alsace now donned the tricolour cockade by

hundreds and thousands.

As yet, however, the composition was only known by the name

of 'Le Chant de Guerre de l'Armée du Rhin,' and its fame remained

local. One interesting feature of this history is the part

played in it by a woman.

Although a prolific musical composer, Rouget de Lisle

possessed, as has been said, only an imperfect knowledge of harmony

and counterpoint. It was his host's wife, the accomplished and

public-spirited Madame Dietrich, who now set to work, not only

correcting technical errors and arranging the piece for part-singing

and orchestration, but making numerous copies. In a charming

letter to her brother at Basle she wrote in May: 'Rouget de Lisle, a

Captain in the Engineers and an agreeable poet and musician, at the

suggestion of my husband, has composed a song suited to present

events (un chant de circonstance), which we find very

spirited, and not without a certain originality. It is

something after the manner of Gluck, but livelier and more stirring.

I have put my knowledge of orchestration to use, arranging the song

for different instruments, and am therefore very busy.'

It was not till the following August that Rouget de Lisle's

composition reached Paris, henceforth to be known as the

Marseillaise.

In his famous novel, The Reds of the Midi, the

Provençal novelist dramatically describes a march historic as that

of the Ten Thousand. The volunteers of Marseilles set forth

early in July, harnessing themselves like beasts of burden to their

field-pieces, singing as they went, and bequeathing the new song to

every village passed through. It was not till the last day but

one of the month that they arrived, and on the 4th of August, for

the first time, the great war-song was heard in the capital.

A few days later the king and his family were prisoners, the

Legislative Assembly dissolved, and the newly-formed Convention

demanded adhesion from all officers and public functionaries, the

alternative being immediate dismissal.

Rouget de Lisle's reply was a decided No, the fateful

word changing the course of his career, a little later bringing his

head within an inch of the guillotine.

IV.

How are we to account for il gran refiuto, such a

withdrawal of the hand from the plough? Was the step due to

social influences, to conviction, or simply to waywardness and

instability of character? He carried his secret with him to

the grave.

Anterior events may in part account alike for his reactionary

mood and his incarceration later as a suspect. Strassburg had

been divided into two factions. On the one side were Dietrich

and his followers, who believed in the possibility of constitutional

reforms whilst retaining monarchical institutions; on the other the

ultra-Jacobin party, headed by that ferocious ex-priest Euloge

Schneider, the Carrier of the east, of whom Charles Nodier has left

us so striking a portrait.

Rouget de Lisle, like many another, unhappily for himself,

possessed one gift he could well have spared. Not only could

he dash off songs, operas, novels, and plays, and skilfully handle

the violinist's bow, but he wielded a mordant pen. In the art

of invective he equalled Rochefort himself. During his stay at

Strassburg he had in his editorial capacity violently lashed

Schneider and his associate Lapeaux, another and equally violent

ex-priest, in the organ of Dietrich's party. The attacks were

continued after his removal to Huningue, a small fortified place in

what until 1871 was the department of Haut Rhin. Small wonder,

therefore, that he soon found himself by these an object of

suspicion. For many months after his dismissal from the army

he led the life of a wanderer, effacing himself in the wilds of his

beloved Jura. So little, as yet, was he generally known as the

author of the Marseillaise, that six months after its composition a

friend wrote to him saying that the new war-song was performed in

all the Paris theatres, and adding: 'You have never told me the name

of the composer. Is it Edelmann?' This Edelmann, a

former close friend of Dietrich, and, with himself, an accomplished

musician, afterwards became his accuser and bitterest enemy.

In his invaluable Reminiscences of the Revolution, Charles

Nodier relates how he heard him with horrible sang-froid thus

arraign his old associate when on his trial at Besançon: 'As my

friend I am bound to weep for thee; as a traitor thou must die!'

During these wanderings, Rouget de Lisle one day engaged a

youth as guide through some mountain passes unknown to him: his ear

was greeted with the refrain:—

|

'Allons, enfants de la patrie,

Le jour de gloire est arrive.' |

'What is that you are singing, my lad?' he asked with some

surprise.

'You don't know, monsieur!' replied the boy still more

astonished. 'Why, that's the song of the Marseillais

volunteers that everybody knows by heart.'

His song had not only reached the capital, but his native

province.

The instability of Rouget de Lisle's character is evidenced

in the next phase of his chameleon-like career. Apparently

overtaken by remorse he demanded re-admission into the army, now

that of the First Republic, took the civic oath, and joined the

victorious forces of Valmy at Verdun. What followed remains a

mystery. Shortly afterwards he was again dismissed the

service, and once more effaced himself among his native solitudes.

Then he returned to Paris, seeking distraction in music and

literature, was soon arrested, set at liberty, rearrested, this time

being kept in prison till the great deliverance of Thermidor.

His immediate liberation was lastly due to the fact that he was the

composer of the Marseillaise, now proclaimed the national hymn of

the Republic.

It is not perhaps astonishing that despite these facts and

certain honours decreed by the Convention, his first mood was of

violent reaction. He could not indeed say with Charles Nodier

[p.38] that he had been the sole

guest of a famous banquet who had preserved his head. But the

amiable Dietrich, his noble guest Victor de Broglie had fallen

victims to personal vindictiveness; a second guest on that memorable

25th of April 1792, Achille de Chastellet, had poisoned himself in

prison; a third was in exile; others had died on the field of

battle; the rest were scattered.

In curious contradiction to the mercilessness of partisanship

at this period was the prison régime. During his incarceration

Dietrich found distraction in musical composition for the

clavecin. No less than twenty pieces called Allemande, a

kind of quick dance, were composed by him whilst a prisoner, the

manuscripts still remaining in his family. For the rest

Henrietta Maria Williams tells us how the prisoners of the Terror

fared, how conversation, cards, books, music and painting in company

relieved the tedium of confinement, how 'her teakettle was never

allowed to get cool,' and above all how one of her jailors, Benoit

by name, did his utmost to alleviate the condition of his charges by

little kindnesses and comforts, 'without deviating from duty ever

pursuing his steady course of humanity.' Schneider and

Edelmann, be it recalled, met with the fate they had so ruthlessly

meted out to others.

The mental see-saw characterising Rouget de Lisle's career

now manifested itself in adhesion to the party of

counter-revolution. Heart and soul he joined the Jeunesse

dorée, danced at the celebrated ball de victimes, and

frequented the salons of Madame Tallien and of General Beauharnais's

widow, the future Empress. A little later we find the author

of the Marseillaise, as he now styled himself, demanding

reintegration into the army under Hoche, a request unhesitatingly

accorded.

Disappointed at not receiving promotion after Quiberon, once

more he retired from the service, a little later once more asking

re-admission. This time he had to do with 'the organiser of

victory,' now the most powerful man in France. Carnot would

make no exception to the new law, for once and for all excluding

officers who had voluntarily thrown up their commissions. The

correspondence of the pair is curious reading. To the great 'Citoyen

directeur,' as afterwards to his still greater rival, the young

military engineer took the tone of a commander-in-chief addressing a

subaltern. With Carnot's fall and Napoleon's star in the

ascendant, Rouget de Lisle's hopes of a career revived.

Excluded from the army, he dreamed of diplomatic distinction.

His protectress Josephine, now Madame Bonaparte, twice procured him

employment, firstly a mission to the Spanish court of no political

importance, secondly a post in the commissariat. As envoy

complimentary he acquitted himself satisfactorily; as contractor for

the barracks he naturally proved a dismal failure. The

complicated story is too long for reproduction here, sufficient to

say that addressing the 'Citoyen Premier Consul' haughtily and

defiantly as he had addressed Carnot, he announced his intention of

crossing the Manche, assured, he said, of receiving honourable

hospitality in England. The intention was not carried out.

A year later again he dipped his pen in gall, his long tirade

containing such sentences as these: 'Bonaparte! you are hastening to

your own destruction, worse still to the destruction of France.

What have you done with our liberties? What in your hands has

become the fate of the Republic? . . . Bonaparte! It was not

with the intention of becoming your patrimony that France threw

herself into your arms,' and so on and so on, an admirable and

powerful arraignment, unfortunately coming from a negligible

quarter. So insignificant a personality indeed was now the

author of the Marseillaise that despite this harangue he kept his

head on his shoulders!

V.

Rouget de Lisle's career recalls a certain Norse fable.

One day a farmer set out for market on a valuable horse he wished to

turn into money. But being of a fantastic and capricious

disposition he thought he would try barter instead. After

many, as he deemed, excellent bargains, having exchanged his good

beast respectively for a cow, pigs, cocks and hens, and what not,

the final lot was sold for a small piece of money which he lost ere

reaching home. Maybe, the one success of Rouget de Lisle's

explains his many failures.

In another respect his story is even more exceptional.

During the long struggle with poverty, neglect, and enforced

inaction that followed, but for his friends he would have found

himself alone. Family affection, the usual adamantine bond of

sympathy and good-fellowship among our neighbours, was here wanting.

'Talk not to me of brothers!' he one day said, the words recalling

Tacitus's bitter epigram, 'They hated with the hatred of brothers.'

The Musée Carnavalet is now the depository of Rouget de

Lisle's correspondence with his brothers and sisters, a collection

revealing painful dissensions. One brother was now a general

in Napoleon's army, another was employed in the naval commissariat.

But the family had not prospered, bit by bit the patrimony of

Montaigu had been parted with; finally the ancestral home, Rouget de

Lisle's asylum for five years, was sold also.

In 1817, at the age of fifty-seven, he settled in Paris,

earning a scanty and uncertain livelihood by teaching and copying

music, making translations from the English for reviews, and

literary hackwork. The inventive faculty was still alert.

He composed new national hymns and accompaniments to Béranger's

songs, wrote librettos, and, it is said, suggested to St.-Simon the

agency of music in social regeneration.

Many old friends were now dead or scattered, but one or two

remained, among these his former companion in arms General Blein,

who survived him by some years, gave him shelter under his roof and

raised a monument to his memory, and new friends gathered round him

devoted as the old. Rouget de Lisle, like most of his

countrymen, possessed a veritable genius for friendship. His

warm heart, generous spirit, versatile, scintillating nature, and

talent for conversation, endeared him to all with whom he came in

close contact, atoning for exasperating foibles. Again and

again some faithful comrade proved 'the man whose name was Help,'

and who dragged him out of the Slough of Despond. When, in

1826, he was torn from his Paris garret and thrown into prison for a

trifling debt, it was Béranger who flew to the rescue, discharging

the claim and collecting a little money for future needs.

General Blein, who lived at Choisy-le-Roi with his mother and

sister, now offered him a home, and partly as guest, partly as

boarder he remained under their friendly roof for some years.

The Blein home was later broken up owing to the death of the two

ladies, and then other friends equally devoted made him one of their

family circle.

The Revolution of 1830 brought him belated honours and

independence. I have ever had a corner in my heart for the

homely citizen king who, like any honest bourgeois, used to preside

at the head of his dinner-table and carve for his large family, and

who would daily have a 'good-day' and a gossip with the guards.

Louis-Philippe never forgot that he owed his crown to revolution and

to the Marseillaise. Even before crowned as Roi des Français

he accorded a pension of 1500 francs to his comrade of 1792, the

pair having fought side by side in Dumouriez's army. Through

Béranger's agency two other pensions of a thousand francs each were

awarded Rouget de Lisle by the Ministers of the Interior and of

Commerce respectively. Finally on the 6th of December of the

same year came that honour which sends all Frenchmen happy to the

grave. The cross of the Legion of Honour now adorned his

breast!

It is pleasant to find this storm-tossed career ending in

days of deep halcyon repose, and indeed in something more.

Rouget de Lisle's last years were not only free from care, suffering

and mental depression, they were enlivened by intellectual

intercourse, irradiated by the quick, keen sympathies of artistic

fellowship. The central figure of a highly cultivated circle,

every evening he found himself surrounded by kindred spirits.

Music and conversation, above all, the reminiscences of the author

of the Marseillaise, made his hostess's reunions animated and

stimulating. The Voiart dwelling commanded a beautiful

prospect, before it stretching the verdant valley of the Seine, at

that time undisturbed by railways and unpoetised by the speculative

builder. In 1892, the centenary of the Marseillaise, old folks

living here could remember the old soldier as slowly strolling to

and fro he sunned himself and drank in the beauty of the scene.

And strange as it seems, in this year of grace nineteen

hundred and five, some hale nonagenarian might still be found who

could tell us of that pathetic figure,—the red rosette, atoning in

part for so many cruel disillusions, conspicuous on his shabby

military coat!

Surrounded by his friends, Rouget de Lisle died on the 27th

of June 1836, a vast crowd following his remains to the grave.

Even under the citizen king, the son of Philippe Égalité, the

Marseillaise had been silenced, but just as the funeral party

prepared to disperse, some workmen began with solemn measure:

|

'Allons, enfants de la patrie,

Le jour de gloire est arrivé.' |

The refrain, taken up by the crowd, swelled into a mighty volume of

sound, fitting requiem of one now numbered among the immortals!

VI.

The fate of the Marseillaise had been meteoric as that of its

composer, one day flashing forth with blinding brilliancy, now

buried in Serbonian obscurity, now the theme of Europe, now silent

as the voice of one gone down to the tomb.

It was hardly likely that Napoleon, having used the

Marseillaise for his own ends, would allow it to serve any other.

The song might prove a siren to his soldiers when in his early days

he led them on to victory. No sooner had the Corsican Cæsar

crushed the Republic and trampled French liberties under foot, than

the electrifying strains resounded no more. Nor was it at all

probable that the Restoration would tolerate consecration of

principles it had adhered to so gingerly. Louis-Philippe,

indeed, on first coming to the throne, allowed himself to be

occasionally serenaded with the hymn of liberty and revolution, but

in his ears also and in those of his advisers, its democratic note

soon seemed a portent and a warning. Eighteen years later the

Marseillaise was resuscitated, once more not only to awaken France

but Europe. Then followed the Napoleonic legend and its fatal

magic, and for eighteen years more, like the princess of fairy tale,

it was condemned to deathless slumber.

And not with the proclamation of the Third Republic was

Rouget de Lisle's song pronounced the national hymn of France.

During the reactionary MacMahon régime the Marseillaise was

studiously kept in the background. From August 1875 until the

same month of the following year I lived at Nantes, being the guest

of a French lady, widow of a former Préfet. Never once do I

remember hearing the strains now familiar even to children of our

own national schools. It was not indeed until the 14th of

February 1879 that the Chamber under Gambetta's presidency recalled

and ratified the decree of the 26 Messier, An II. (14 July 1795) and

the Marseillaise was proclaimed the national hymn of France.

As we review this strange history an inevitable reflection

occurs to the student of history. For strange it is, but true,

the Revolution was, pre-eminently a lyrical epoch. A period of

fiercest passions and superhuman endurance, of Titanic struggles for

national existence, found expression in song and melody. The

stormy years preceding the Restoration constitute indeed the most

musical period of French history. Song and vaudeville,

vaudeville and song, characterise crises appalling as any in

modern annals. Seeking relief from actualities, native genius

took a sportive turn. The authors of Jean qui pleure et

Jean qui rit, of Le Temps et l'Amour, of Il pleut,

bergère, il pleut, were severally contemporaries of Robespierre

and Napoleon.

These and many other graceful trifles have become classics,

numerous editions having been unearthed within recent years by the

Société de l'histoire de la Révolution. [p.48]

The Conservatoire, that great national school of music and

declamation, was founded by the Convention, similar schools being

opened at Marseilles, Nantes, and other large cities. In the

words of M. Rambaud, the history of French national music dates from

the Revolution, the crown being decreed to the young soldier, who as

a child followed the pipe of wandering minstrels in his beloved

Jura—whose verdict on himself was so singularly falsified.

'Your musical talent,' he wrote to Berlioz in 1830, 'is a volcano

always emitting flame. Mine is only a lighted wisp, blazing

for a moment, then smouldering away.'

――――♦――――

CHAPTER III.

ON THE TRACK OF BALZAC—LIMOGES

THERE are certain

French towns to which Balzac is the best possible, nay, the

indispensable guide. Saumur, the home of Eugénie Grandet, and

Guérande, the scene of Béatrix, have, indeed, become literary

pilgrimages, but other places of great interest in themselves

possess a double interest for the Balzac student, notably Limoges

and Angoulême.

HONORÉ DE BALZAC

(1799-1850).

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

The Danton of fiction, as Philarète Chasles has called him,

whilst bestowing world-wide fame upon a sleepy Breton bourg or a

remote Touraine hamlet had little general knowledge of his own

country. In Béatrix, for instance, he speaks of France

still retaining two walled-in towns, perfect specimens of feudal

architecture, namely Guérande and Avignon. As all travellers

know, such specimens are numerous—Carcassonne, Saumur, Provins,

Montreuil, by no means exhaust the list. Travelling was

expensive and laborious in Balzac's day, and we must be thankful

that he travelled much more than most people.

Limoges, the scene of Le Curé du Village, and

Angoulême, that of Les Deux Poètes, are both cities

commandingly placed and rich in archaeological and artistic

attractions. On lately revisiting the capitals of the Haute

Vienne and the Charente I found them more engaging than ever and

quite as neglected. Seldom, indeed, do you encounter a stray

compatriot in the surroundings so minutely interwoven with Balzac's

stories, stories as full of pathetic interest- as any of his vast

series. Crowning the lofty banks of the Vienne, Limoges is

seen from afar, the gloomy tower of its beautiful cathedral forming

a strange contrast to the bright landscape. September is the

month for the chestnut country, such is the Limousin par

excellence. What the apple-tree is to Normandy, the olive

to Provence, is the chestnut in these regions, and the veteran trees

are a glory to behold. Formerly chestnuts almost supplanted

bread with the country folks. Of late years, alas, wide areas

of chestnut wood have been levelled for the culture of cereals.

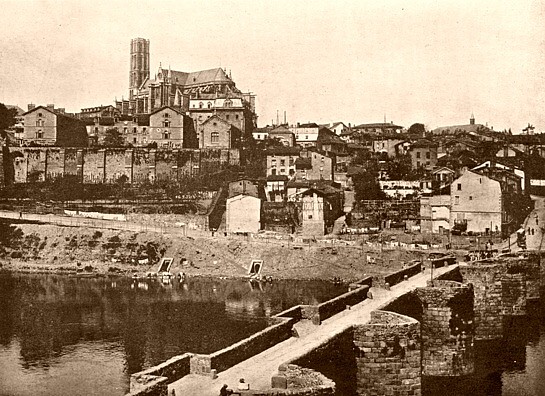

LIMOGES

Strolling through the lower town with Balzac's novel in hand

we feel that these tortuous streets and ancient dwellings must

remain very much as he saw them three quarters of a century back.

The tumble-down shop 'unchanged from the middle ages' in which the

ill-fated girl's miserly grandfather amassed riches—the bookseller's

window on which Paul et Virginie caught her eye, a turning

point in her history—the stately hotel of the rich banker with 'the

façade of a public building,' her home when exchanging an avaricious

father for an equally avaricious husband—the cottage on the opposite

bank whither she strolled on summer evenings to enjoy the view, her

mother's society—and stolen interviews—the lonely suburban dwelling

by the river with its garden, scene of her lover's crime, the double

murder saving her from shame and exposure—all these sites seem as

identifiable as any in guidebooks.

Here, indeed, is a page that might well have been transcribed

for traveller's use: 'The bishop's palace of Limoges crowns an

eminence bordering the Vienne, the gardens flanked with solid

masonry descending stairwise to the river. So considerable is

this elevation that the Faubourg St. Étienne on the opposite bank

seems level with the lowest terrace. From that point,

according to the direction pedestrians may take, the river winds

sinuously or flows with unbroken sweep through a rich panorama.

Westward from the bishopric gardens is seen a graceful curve, the

Vienne here bathing the Faubourg St. Martial, a little further on

rising the Poplar-covered islet fancifully designated by Wronique,

the Île de France. Eastward the perspective is one of hills

forming a natural amphitheatre. The witchery of its site and

the rich simplicity of its style make the évêché the most remarkable

edifice of Limoges. . . . The bishop was seated in an angle of the

lower terrace under a trellised vine taking his dessert and drinking

in the beauty of the evening. The poplars on the islet seemed

a part of the water, so clear their reflections gilded by the

setting sun. Thus mirrored, a variety of foliage made up a

whole tinged with melancholy. . . . Beyond, the spires and roofs of

the Faubourg St. Martial gleamed between clustering greenery.

The subdued murmur of a country town half-hidden in the bent arc of

the river, the softness of the air'—here follows a truly Balzacian

touch—'all contributed to impart to the prelate that quietude of

mind insisted upon by all authorities on digestion—his eyes wandered

to the right bank, soon becoming fixed upon the enclosed garden,

scene of the double assassination.'

The bishop's palace, so glowingly described by the great

novelist, had moved Arthur Young to enthusiasm half a century

before. 'The present bishop,' wrote the Suffolk farmer in

1787, 'has erected a large and handsome palace, and his garden is

the finest object to be seen at Limoges, for it commands a landscape

hardly to be equalled for beauty; it would be idle to give any other

description than just enough to induce travellers to visit it!

A river winds through a vale surrounded by hills that present the

gayest and most animated assemblage of villas, farms, vines, hanging

meadows, and chestnuts blended so fortunately as to compose a scene

truly smiling.'

Balzac's good bishop and the country priest fetched from the

murderer's village in order to confess him play an important part

throughout the story. Véronique, whose beauty at nine years of

age was the marvel of Limoges, whom a chance reading of Paul et

Virginie in girlhood made sentimental and visionary, is a

character after Balzac's own heart. She seeks refuge from a

loveless home in Byron, Walter Scott, Schiller, Goethe, and in

pietistic exercises. These failing to satisfy her aspirations

she accepts the love of a protégé, a young man of inferior position

whom, as she said in her dying confession, she 'intended to train

for heaven, but had conducted to the scaffold.' When this

supreme crisis in her life came, when her lover lay sentenced to

death in prison, the conduct of cette sublime femme, as

Balzac calls her, was what might have been expected. The

sentimentality that did duty for passion prompted no heroic

initiative. Instead of throwing good repute to the four winds,

consoling her lover in prison, confronting his judges, thereby

averting the death penalty, she held aloof. The unhappy youth,

showing a temper truly valiant, went to his doom with sealed lips,

and Véronique betook herself to works of abstinence and piety,

thereby expiating her fault and gaining saintly renown.

But all this time the dreadful secret had not been her own.

The bishop had divined it in the first instance, and the curé

was put in possession of it by means of the confessional.

When, worn out by fasting, the cilice, and other penances, she

wished to make public avowal, these two endeavoured to dissuade her.

'Die in peace,' urged the bishop, you have endured enough, God has

heard you.'

The dying penitent insisted, however, and before a numerous

assemblage—priests, civic authorities, and friends—she unburdened

herself, pleaded excuse for the reticence that had saved her own

reputation at the cost of another's life, for having been 'carried

away by the terrible logic of the world' ('entraînée par la

logique terrible du monde').

Le Curé du Village is far from being one

of Balzac's greatest stories, and Limoges is by no means one of the

greatest cathedral towns in France, but the romance embellishes the

town and a sight of the town vivifies the romance. Henceforth

we cannot think of them apart. Balzac's excessive minuteness

is far from being a fault in the eyes of the wayfarer on his track.

His long descriptions do not weary under such circumstances; on the

contrary, they become vitally interesting. We should re-read

Béatrix at Guérande, hardly changed, I dare say, since I saw

it many years ago—Eugénie Grandet at lovely little Saumur,

Le Curé de Tours at Tours, Ursule Mirouët at the pretty

town of Nemours, and so on, in each case the scenery being

elaborated with as much care as the figures with which they are

animated.

Heretical as it may appear, to my thinking the fine gothic

cathedral of Limoges is disfigured by its gloomy clock tower.

The entire town seems overshadowed, rendered gloomy, by this tall

lank steeple of funereal stone which we catch sight of from every

point.

After an interval of some years I lately revisited the

capital of the ancient Limousin and chef-lieu of the Haute Vienne.

The clock tower, I thought, looked grimmer, more spectral, than

ever. It is slightly, ever so slightly, inclined, a

peculiarity no little adding to its eeriness. As we gaze, we

cannot help contemplating a possible calamity, death and destruction

dealt by a sudden collapse of that tremendous pile.

How came these leaning and curved spires about? Was it

by chance, caprice, or from devotional motives that the clock tower

of Limoges, like Limoges beautiful spire of Dijon cathedral, was

thus constructed, made to bow before Heaven?

For many years I was in the habit of staying at the old

Burgundian capital, ever admiring that bending spire, as graceful a

thing in stone as fancy could picture. But the inclination

gradually became more marked, and it was feared that some day the

spire would fall; so, ten years since, it was taken down and a new

perfectly upright one erected in its stead.

Limoges cathedral itself is beautiful alike without and

within, perfect type of Northern French Gothic, a type we shall soon

exchange for another.

With delight I again lingered in the exquisitely proportioned

interior, ruminating on the grand old architects, stone-masons, its

creators, their names for the most part forgotten, their life's work

recorded in imperishable stone. These modest but truly great

artists have ever been to me a subject of admiring contemplation,

and at every stage of French travel the traveller is reminded of

them. It would seem that sacred legend did not suffice for the

prolific fancy of such builders, so often do we find mythological

subjects turned to account. Thus the richly ornate rood-loft

here represents the six labours of Hercules in bas-relief,

unfortunately much damaged. St. Michel-aux-Lions, on high

ground to the right of the cathedral, recalls our own beautiful

Grantham, so elegant and conspicuous is its spire.

The interest of Limoges is far from being exhausted when we

have revisited cathedrals and churches. Limoges is the cradle

of two exquisite arts, one, alas! now lost to the world for ever,

the other flourishing. The inimitable enamels of the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries are only to be admired in museums.

The dainty faïence, due to the discovery of a lady in 1760,

is to-day an important manufacture, one of the first, if not the

first, in France.

Genius has its harvests, its extraordinary efflorescence as

well as Nature's products: thus not one, but groups of enamellers

sprung up simultaneously, the delicate art ran in families, in

clans, the skill of one merged in the excellence of all, fathers and

sons, brothers and cousins earning collective fame, inheriting

collective renown! These sons of Limoges have glorified their

native city, lent it unique distinction. Their enamel remains

inimitable, unpurchasable, existing collections are not to be added

to, for all time they must remain stationary. These masterpieces of

an art which dealt in masterpieces only do not appeal to all, they

are appreciated by the eclectic, the connoisseur, not by ordinary

lovers of painting and the decorative arts. But the other speciality

of Limoges, its famous faïence, is more readily understood