|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XIX

IN THE MORVAN

I.

THE HISTORIAN OF VÉZELAY

THERE is no more

delightful little journey in France than a zigzag through the Morvan,

that is to say from Auxerre to Avallon, from Avallon to Autun,

thence making the excursion to Château Chinon. Here indeed is still

to be found the romance of travel, whilst every spot is historically

interesting.

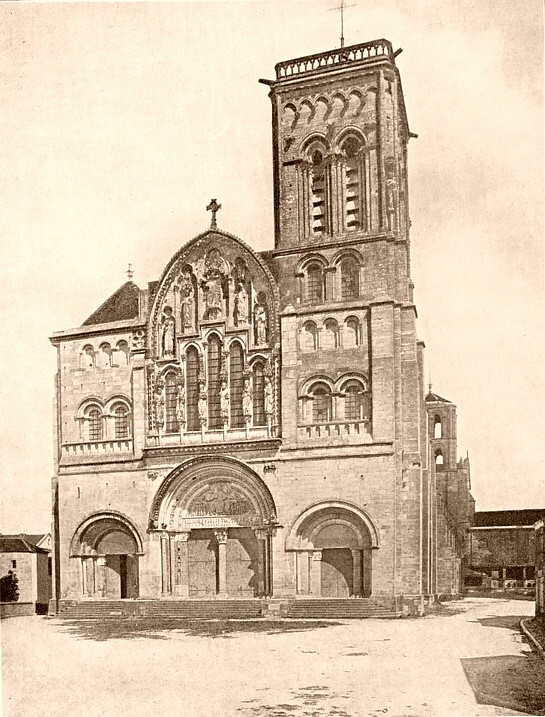

Striking is the abbey church of Vézelay, from its mountain-top so

majestically overlooking the two departments of the Yonne and the

Nièvre. I say mountain-top, for so indeed the pyramidally formed

vine-clad hill appears by contrast with the vast panorama spread at

its feet: the sombre Morvan, all wood and river and valley, the

Yonne, country of vines and tillage. Far and wide we see Vézelay,

and whether we approach it from the Nièvre by Clamecy, or from the

Yonne by Avallon, alike the distant and the nearer aspects are

equally grandiose. Almost fairy-like in the distance is the aspect

of the two tall towers and long roof rising conspicuously above the

ancient fortifications, and towering above the neighbouring hills

and crags. Most beautiful is this aspect of Vézelay, the old-world

town with its mellow walls, green shuttered cottages, and festooned

vines giving it an Italian look; the crowning glory of the place,

its abbey church, stretching as it seems from one end of the broad

platform to the other. The hill seems made indeed for the church, as

a pedestal for a statue, not the church for the hill. But for its

red tiles this look of Vézelay would remind us of St. Albans, the

enormous length of the nave at first appearing almost unsymmetrical. But here we have no sober greys, no cloudy heavens of our own

Midlands; the rich red of the tiles, the glittering whiteness of the

stone towers, the soft blue sky, the waxen green foliage of the

vines beneath and around, the warm sunshine tingling through all,

remind us that we are in France and not in England. Rich as is Vézelay in outward effect, for its façade, in spite of mutilations,

retains much of its former splendour, it is chiefly the interior

which archaeologists come to see and to admire. The general

impression is one of coldness, arising from the absence of colour or

any kind of relief in the way of decoration, and the extraordinary

length of the building. The church is only exceeded in length by two

or three cathedrals of France; but here we have not a pane of

coloured glass, not a column of Coloured marble, absolutely nothing

to break the monotony. The delicate grey of the stone, alternated

with the white, and the exquisite proportions of the whole, in part

atone for this monotony. Nevertheless, the eye cannot rest long at a

time on the interior without fatigue.

The prominent feature of Vézelay is its famous narthex, on which all

the imaginative wealth of the builders was lavished. It is shut off

from the nave, and the doors are only thrown wide open on occasions

of solemn processions; but the sacristan admits strangers both

within and to the lofty tribune above. On the occasion of my visit

all was confusion, owing to casts being made of the rich sculpture

adorning the narthex for the museum of the Trocadéro, Paris; but

enough was visible to give an idea of its magnificence. I was led up

the narrow stone staircase into the open gallery, whence is surveyed

the whole interior—a vast and wonderful perspective, arch upon arch,

column upon column, as if indeed it were one cathedral opening into

another as vast as itself. The amazing extent of Vézelay is here

realised, and under a most beautiful aspect, the dazzling whiteness

adding greatly to its beauty. There is, however, no balustrade, and

from the giddy height it is pleasant to turn and wander round the

little museum, so called, at the back. A great number of beautiful

things, all more or less fragmentary, are collected here, many of

which, as well as the sculptures of the portico and the narthex, may

now be seen in plaster at the Trocadéro. The entire building has

undergone restoration under the supervision of the late Viollet-Le-Duc. Poverty, if not neglect, has fallen upon the once

puissant abbey of Vézelay. It does not even possess an organ, the

poor little tones of a harmonium alone being heard throughout its

vast aisles. On the other hand, a superabundance of wealth has not

been the means of spoiling the interior by means of meretricious

decorations. A few bouquets of natural flowers and a statuette or

two make up all the offerings of the pious here.

ABBEY-CHURCH OF VÉZELAY

At the foot of the hill on which Vézelay stands, rising from a

narrow, squalid village street, and evidently placed on low ground

in order that its details might be seen to advantage, is another

famous church, that of St. Père-sous-Vézelay. This is of the

thirteenth century, while Vézelay belongs to an earlier period. In

the abbey church we have the rounded arch, here the pointed, while

in the interior of St. Père-sous-Vézelay we have studied simplicity

and absence of detail, the exterior is of a richness, sumptuousness,

and grace, all the more striking perhaps because so close to our

eyes. The church stands indeed by the wayside, and we come suddenly

upon its tower, one story springing magically from the other, as in

Antwerp Cathedral, the blue sky shining through its delicate

apertures, an extraordinary lightness being obtained in combination

with great splendour and solidity. The architect seems to have begun

his work without any precise notion of the ending, and the result is

a gorgeous and fanciful whole, of which it is difficult to give any

idea. The façade, unhappily much defaced, is marvellously rich in

sculpture and design, while above it, in much better condition,

rises, wing-like, a kind of aerial porch as sumptuous in

ornamentation. High above this the pinnacles of the tower show

figures, statuettes, and ornamentation in great lavishness, all in

deep sober grey, not white and cold as is the exterior of Vézelay.

Enormous flying buttresses gird the church, giving it a look of

wonderful strength, although not perhaps improving the general

effect. The surprise that this church is to us, as we come upon it

so suddenly, and the contrast it presents to the poverty of its

surroundings, will not easily be forgotten. Fine as Vézelay is

itself, planted fortress-like on its airy height, St.

Père-sous-Vézelay is hardly less impressive—an architectural pearl

flung upon a dung-heap. The one strikes us by force of its glorious

position, the other by inadequateness of site. Yet doubtless in both

cases the position had significance, and the architects of the later

church lavished so much wealth upon it designedly. Vézelay, rising

proudly above the ancient Nivernais, signified that the church was

for the puissant and the rich. The exquisite church at its feet

might well symbolise that the poorest had contributed to such

splendour, many a peasant hardly emerged from serfdom contributing

to such erections.

From an especial point of view the history of Vézelay is very

instructive. In the twelfth century this village, for town it was

not, enjoyed the prestige and prosperity of a miniature Lourdes,

certain relics of Mary Magdalen attracting enormous crowds at the

annual festival of the saint. Vézelay had grown to be as important

as a city, and the inhabitants, although serfs of the abbey, had

contrived to amass wealth and shake off some shackles of servitude. Whilst still compelled to grind their corn and bake their bread at

the abbey mills and ovens, they enjoyed the privilege of bequeathing

their prosperity to their children—a privilege indeed in those days! The church and relics had been placed by their possessor, Gerard de Roussillon, three centuries earlier, under the jurisdiction of Rome,

both thereby constituting an appendage of the holy see, and being

quite independent of feudal suzerainty. As was only to be expected,

such accumulated wealth of spiritual lords aroused the jealousy of

their temporal rivals, the counts of Nevers, and at the same time

the people, with increased well-being, aspired to an extension of

their personal liberties. Hence arose a triple struggle, sacerdotal

tyranny represented by the seigneur-abbé named Pons, seigneurial

cupidity by Count Guillaume of Nevers, and popular ambition by

Hugues de St. Pierre, a skilled mechanician or worker in iron, and

possessed of considerable wealth.

The contest was waged with excessive bitterness on all sides, the

leading part being played by the great artisan, for great he was

indeed, one of those industrial heroes whose names deserve to live

in history. Hugues de St. Pierre was moved to generous as well as

individual ambition by his contrasted means and position, his state

with that of his fellows being one of servitude. Mingled with

commiseration for others was a desire for personal aggrandisement. He dreamed not only of civic rights for all, but of a commune of

which he himself should be chief magistrate, a noble dream, and one

which at one time seemed on the point of being realised.

Partly, it must be believed, from generous motives also, Count

Guillaume fostered this popular movement, and after a fruitless

endeavour at compromise with his adversary the Abbé Pons, he thus

harangued its leaders and participants:—

'Courageous, dignified, and prudent men, who have laboriously

accumulated goods and money whilst in reality being possessors of

nothing, deprived of the natural liberties of man . . . my dear

friends, form a league of deliverance among yourselves, and I

promise to aid you to the utmost.'

At a popular assembly summoned somewhat later, all allegiance to the

seigneur-abbé was repudiated, a veritable commune was formed, the

elected magistrates being called consuls, [p.242]

and in a day the serfs of Vézelay had declared themselves free men

and citizens endowed with full municipal rights. As might be

expected somewhat exaggerated confidence was raised by this bold

initiative, a revolution in miniature.

No sooner had the commune of Vézelay been proclaimed than the

principal citizens set about building fortified dwellings after the

manner of those in Provençal and Italian towns. In 1226 Avignon

possessed no fewer than three hundred houses having walls and a

tower.

The first to erect this symbol of defiance was one Simon, a rich

money-changer, and next in importance to Hugues St. Pierre among the

burghers. But, alas! this gleam of better days, this realisation of

manly hopes proved transitory. The stout-hearted citizens of Vézelay

were powerless against a tyrannic church and armed, autocratic

power. The king interfered. Dastardly reprisals followed the

breaking up of the commune and the suppression of civic rights. St.

Pierre's house, mills, and other buildings were pillaged and pulled

down, and an armed troop was despatched by the seigneur-abbé Pons to

demolish Simon's tower, 'finding the money-changer stolid as an

ancient Roman seated by his fireside with wife and children.' It was

not until the 4th of August 1789 that Vézelay was freed from feudal

servitude, its three years of municipal liberty fought for six

centuries previously forming a memorable epoch in provincial

history. Augustin Thierry, the historian of the Norman Conquest,

gives the story in his interesting Lettres sear l'Histoire de

France, an excellent travelling companion in these regions.

It is to Prosper Mérimée that France and the world owes the

preservation of Vézelay.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XX.

IN THE MORVAN

II.

THE POET OF THE BEEVES AND MR. HAMERTON

ON MONT BEUVRAY

CHÂTEAU

CHINON may be

reached by various post roads, but that from Autun is the most

picturesque, a five hours' ascent through the very heart of the

Morvan. From the coupé of the cumbersome old diligence we get

an excellent view of the country, at every turn coming upon wider

and more magnificent prospects; on either side brilliant green

pastures watered by little rivers clear as crystal, lofty alders

fringing their banks, and the beautiful white cattle of these

regions pasturing peacefully here and there; beyond these gracious

scenes rise wooded hills or masses of rock—the Morvan is called 'le

pays de granit' (country of granite)—while, higher up, are gained

tremendous panoramas of the same scenery with a background of violet

hills. These hills are by local usage designated as mountains, and

are nearly of equal height with the Cumberland range; the highest

peak in the Morvan being about that of Skiddaw. Far away the effect

is of a mountainous country; and the famous Mont Beuvray, the

Bibracte of Cæsar's Commentaries, which lies about half-way

between Autun and Château Chinon, is a grand outline, to-day dark

and frowning under a cold, grey sky. There are wild crags to climb

in plenty about the Morvan, and romantic sites approaching to

sublimity, but its chief beauty lies in a quiet, caressing grace of

smiling pastoralness. Nothing in a quiet way can be more delightful

than these rivers and rivulets, each bordered by the graceful alder;

such alders I have never before seen in France, nor anywhere more

beautiful pastures or winding lanes. The dominating characteristic

of the scenery is, however, forest; the department of La Nièvre

being one of the most wooded in France, and so abundant in firewood

that the poor never need buy any. They can pick up enough and to

spare.

The country is wonderfully solitary; excepting little children

keeping geese and goats here and there we hardly meet a creature. Farther away on this September day are women getting in potatoes,

but little else of farming work is going on. The greater part of the

country is given up to pasturage, and its wealth consists in

cattle-rearing. We pass one or two straggling villages of old-world

appearance, but there is one sign of progress and animation. We know

without asking what mean the new or half-finished buildings here and

there. Throughout every nook and corner of France schools were being

built as fast as masons and bricklayers could carry on the work, and

ere long there will not be a single commune throughout the length

and breadth of France without its new school. Meantime driver and

passengers alight while our steady horses climb one tremendous

ascent after another; as we wind about them we catch sight of

villages perched on airy crests, reminding us of that African

Switzerland with its castellated hamlets, Kabylia; and after a five

hours' climb, all accomplished by the same pair of horses, we at

last come within sight of the ancient capital of the little Celtic

Morvan. Once an important stronghold, it is now the quietest,

obscurest of country towns, with nothing attractive to the stranger

but its position. The whole Morvan lies at our feet; and although

the weather is dull we have atmosphere enough to make out the chief

features of the country as if we had it delineated before us on a

map. Alternating with pasture and cornland, glen and dale, mountain

stream, tossing river, and glistening the sterner and grander

features of Morvan landscape, dark forests stretching over vast

spaces, bare granite peaks, wild sweeps of moorland. Little villages

and townlings are seen scattered about, while curling around the

mountain-sides are splendid roads, mere threads in the distance. The

whole scene is strangely primitive and pastoral. No railways, no

chimneys of manufactories, no hideous steam-engines mar the

naturalness and freshness of the Morvan. All is quiet, rustic, and

unspoiled as yet by civilisation.

Château Chinon has a history. Built on the site of a Gallo-Roman

camp, it was strongly fortified in the Middle Ages, and has seen

several sieges. The warlike little capital, towering so royally over

the country, now does a peaceful trade in hides and wine, and,

excepting commercial travellers, seldom any one ever finds his way

thither. An English tourist has an outlandish look in the eye of the

inhabitants, who wonder what in the world can have brought him so

far. These good Morvandais have a character of their own, and are

said to be of pure Celtic type: you may still see a peasant with the

short cloak or Gallic sagum thrown over his blue blouse; and their

patois is unintelligible to strangers. Life is exceedingly laborious

here, and little is produced by the soil except buckwheat and

potatoes, the latter being grown for the fattening of pigs.

I think it must have been in the Morvan that Pierre Dupont wrote his

famous song, 'Mes Bœufs.' Beautiful as are French oxen generally, in

the Burgundian Highlands they are especially endearing. Sleek,

creamy white, and gentle-eyed, they people sylvan scenes, or, one

might fancy, with a sense of pride and fellowship, are seen crossing

and re-crossing the fallow.

As in my rendering of the equally famous 'Carcassonne' I have only

endeavoured to give the spirit and meaning of its rival in

popularity.

|

MY BEEVES

I.

Two oxen have I in my shed,

Milk-white with spots of ruddy hue.

'Tis by their toil the plough is sped,

Thro' winter's slough and summer's dew.

'Tis thanks to them, with golden store

My barns are piled from year to year,

In one week's time they gain me more

Than what they first cost at the fair.

Dear is my good wife Jeanne, her death I should deplore,

But dearer are my beeves, their loss would grieve me

more.

II.

When grown up is our Coralie,

And likely suitors come to woo,

No niggard will I prove, pardie!

Gold shall she have and farmstock too.

Should any ask my beeves beside,

Straightforward would the answer be,

My daughter quits me as a bride,

The oxen will remain with me.

Dear is my good wife Jeanne, her death I should deplore,

But dearer are my beeves, their loss would grieve me

more.

III.

Aye! eye them well, a goodly sight,

As snorting loud they stand abreast,

Upon their horns the birds alight,

Where'er they stop to drink or rest.

Each year when Mardi Gras falls due,

The Paris butchers come to buy;

But see my beeves decked out for view,

Then sold for slaughter?—no, not I!

Dear is my good wife Jeanne, her death I should deplore,

But dearer are my beeves, their loss would grieve me

more. |

Good pedestrians should climb the magnificent foreland of Mont

Beuvray, taking with them Mr. Hamerton's inspiring little book,

The Mount. 'On the western side of the valley or basin of

Autun,' wrote this exact yet enthusiastic devotee of Mont Beuvray,

'rises a massive hill 1,800 feet above the plain and 2,700 above the

sea-level. It plays a great part in all effects of sunset, being

remote enough to take fine blue or purple colour in certain

conditions of the atmosphere.' And he adds: 'Mont Beuvray has not

the grandeur of my old friend Ben Cruachan, and as for height its

whole elevation is but the difference between Mont Blanc and

the Aiguille Verte, yet the impression that Ben Cruachan leaves is

evidently what you will receive after climbing several other

Highland mountains, and the exploration of glaciers on Mont Blanc

has just the same kind of interest as the exploration of glaciers in

other regions of the Alps. Every one who knows the Beuvray remembers

it as one remembers some very original human beings, for there are

not two Beuvrays either in France or elsewhere.'

This charming little book contains amongst other good things the

account of a most curious psychological experience. I give it

in the author's own words—

'The Antiquary' [the French host of his bivouac on the Mount] 'had

heard me speak of Rossetti's poems, a copy of which I happened to

have with me, and he begged me one evening to translate one of them. Now in ordinary circumstances I could not extemporise a French

translation of an English poem that would be worth hearing, but

something told me that night that a power of this kind was

temporarily in my possession, so I opened the book and began. The

effect on myself and everybody present was remarkable. I felt

transported into the highest realm of poetry and became for that

single hour a French poet endowed with Rossetti's genius, which

passed through me as electricity passes through a conductor. In this

way I translated—if such spontaneous utterance is to be called

translation—'The Blessed Damozel,' 'Sister Helen,' 'Stratton Water,'

and both I and every one present were in a state of intense emotion

the whole time—indeed, as for the audience, I never saw an audience

so moved by poetry in my life, and the next day, when prosaic reason

returned to us, we were all very much astonished at the enchanted

evening we had spent together. When I look over these poems to-day,

they seem to me utterly untranslatable, and I cannot conceive

through what medium of equivalents the power of them reached my

hearers; yet it did reach them.'

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXI.

MILLEVOYE AND ABBEVILLE

THRICE happy that

poet who has written one poem, no matter how short, that the world

will not willingly let die!

Such was the lot of Abbeville's poet. Few readers of these pages

have probably heard his name—a little lyric in itself—fewer still

have read the score and odd lines without which no French anthology

is complete.

Millevoye's elegies, narrative pieces, Dizains et Huitains,

ballads, romances, epigrams, translations, and imitations from Greek

writers, are, clean forgotten; La Chute des Feuilles remains

a classic. The grace, tenderness, and harmony of that little poem

have assured its author's fame.

Sainte-Beuve, whose lynx-eyed vision discerned a grain of gold no

matter how deeply embedded in ore, tells a curious story about Millevoye's one masterpiece. In 1837 he wrote (see his Portraits

Littéraires, vol. i.): 'I was lately informed that the Chute

des Feuilles translated into Russian had been re-translated from

that version into English by Sir John Bowring, and that the second

rendering had been quoted in France and held up as a specimen of the

dreamy, sombre northern muse. The poor poem had travelled far and

wide, Millevoye's name being lost on the way!'

And the critic of critics adds: 'No matter how far his verses may

travel, the name of Millevoye can never in reality be separated from

them. Their author unexpectedly and immediately attained the good

fortune which lately made a less happy aspirant exclaim to me, "Oh,

could I only write a little story, a little poem, a work of art no

matter how trifling, that should be for ever remembered! Could I

only add the tiniest gold piece marked with my name, to the

accumulated treasure of ages." Then cried the ambitious poet—"Only a

second Gray's Elegy, a Jeune Captive, a Chute des Feuilles."'

Millevoye was born at Abbeville on the eve of the French Revolution,

and seems to have led an easy, uneventful life, dividing his time

between Paris and his native town and by turns exchanging

dissipation and the world for literary seclusion à la Balzac. In

1813 he married, and three years later lost his life through one of

those freaks to which he had ever been addicted. Entertaining some

friends to dinner in his country house at Épagnette near Abbeville,

a discussion arose as to a certain steeple just visible in the

distance. Some of the party affirmed that the spire belonged to the

village of Pont-Remy, others that it was that of its neighbour

called Long. Unable to resist a sudden impulse, he ordered his horse

to be saddled, and quitting the company set out for the disputed

steeple. He could not rest without settling the matter in dispute. But hardly was he on the high road than his animal, which he had not

used for some time, reared and overthrew him, breaking a thigh-bone. He died in Paris in August 1816, being just thirty-four. 'His

memory,' writes Sainte-Beuve, 'remains dear and interesting; the

brilliant train following in his wake has not effaced Millevoye's

name.'

Yet, or rather as might be looked for, making all French hearts kin

is of the simplest, the touch of nature. I give Sir John Bowring's

translation.

MILONOV

(Specimens of Russian Poets, vol. ii. pp.

223-226, 1823).

|

THE FALL OF THE LEAF

Th' autumnal winds had stripp'd the field

Of all its foliage, all its green;

The winter's harbinger had still'd

That soul of song which cheer'd the scene.

With visage pale, and tottering gait,

As one who hears his parting knell,

I saw a youth disconsolate;

He came to breathe his last farewell.

'Thou grove! how dark thy gloom to me,

Thy glories riven by autumn's breath;

In every falling leaf I see

A threatening messenger of death.

'O Æsculapius! on my ear,

Thy melancholy warnings chime:

Fond youth! bethink thee, thou art here

A wanderer—for the last—last time.

'Thy spring will winter's gloom o'ershade

Ere yet the fields are white with snow

Ere yet the latest flowerets fade,

Thou in thy grave wilt sleep below.

'I hear a hollow murmuring,

The cold wind rolling o'er the plain—

Alas! the brightest days of spring

How swift, how sorrowful, how vain.

'O wave, ye dancing boughs, O wave!

Perchance to-morrow's dawn may see

My mother weeping on my grave—

Then consecrate my memory.

'I see, with loose, dishevell'd hair,

Covering her snowy bosom, come

The angel of my childhood there,

To dew with tears my early tomb.

'Then in the autumn's silent eve,

With fluttering wing, and gentlest tread,

My spirit its calm bed shall leave,

And hover o'er the mourner's head.'

Then he was silent—faint and slow

His steps retreated;—he came no more:

The last leaf trembled on the bough—

And his last pang of grief was o'er.

Beneath the agèd oaks he sleeps;—

The angel of his childhood there

No watch around his tombstone keeps;

But when the evening stars appear,

The woodman, to his cottage bound,

Close to that grave is wont to tread,

But his rude footsteps, echo'd round,

Break not the silence of the dead. |

Abbeville has named a street after its poet, but, strange to say,

has raised no monument to his memory. A simple statue or

commemorative fountain might well replace the unsightly rococo

monument defacing what would otherwise be a majestic scene. Over

against the grand cathedral, thus designated, although Abbeville is

no bishopric, rises a mass of white marble, the florid sculptures

being surmounted by the figure of Admiral Courtet. Nothing could

present a greater and more disconcerting contrast than this pile of

tasteless, glaring white, and the grandiose edifice of sombre grey

rising so stately above. Seldom in France does taste receive such a

shock. How delightfully unprogressive are some regions of provincial

France! Could Arthur Young revisit Abbeville after the interval of a

hundred and twenty years, he would find the principal hotel hardly

changed. On asking for tea he would be served with what tastes like

nothing so much as a decoction of hay, and accompanied by boiling

milk and tablespoons. Rough, unkempt men now as then would make his

bed and sweep his room, and the rest is of a piece, modernity slowly

filtering in by drops.

Scores of times had I myself passed through this delightful little

town, without halting even for a night, and that Anglo-Saxons seldom

make it their headquarters banking-houses as well as inns betoken.

In Italy and Switzerland and also in many French towns, cheques on

London banks are readily changed or received as payment. Let no

tourist flatter himself that even if furnished with a passport he

will be able to pass his cheques at Abbeville, and on changing our

Bank of England notes at a moneychanger's we were mulcted at the

rate of a franc upon every five pounds.

These are however the merest bagatelles. French of the French,

Abbeville is wholly delightful, a town rich in artistic resources

and possessing a lovely environment. Far and wide falls on our ears

the majestic boom of its cathedral bell, by comparison that of

Amiens is but a tinkle; here the deep, rich, resounding note

striking the hours reminded me of the famous bourdon I had

heard years before at Reims announcing President Faure's interment.

And as I think of the tremendous notes and the exquisite pleasure of

drinking them in, I recall Wordsworth's picture of the gentle dalesman—

|

'From whom in early childhood was

withdrawn

The precious gift of hearing. He grew up

From year to year in loneliness of soul;

And this deep mountain valley was to him

Soundless with all its streams.

The bird of dawn

Did never rouse this cottager from sleep

With startling summons; not for his delight

The vernal cuckoo shouted, not for him

Murmured the labouring bee. When stormy winds

Were working the broad bosom of the lake

Into a thousand thousand sparkling waves,

Rocking the trees, or driving cloud on cloud

Along the sharp edge of yon lofty crags,

The agitated scene before his eyes

Was silent as a picture.' |

To have missed the boom of French cathedral bells is a deprivation

indeed. After visiting and revisiting that magnificent grey pile

without a blemish, the traveller has his choice of two museums, that

of the municipality and that called after its too generous donor,

Boucher de Perthes. I say 'its too generous donor,' because like

many another collector this enricher of his native town forgot the

admirable adage that the half is better than the whole. Here, palatially housed in charmingly laid-out grounds, are collections as

multifarious and bewildering as those almost crazing the Paris

municipality some years since and now placed in the Petit Palais. Just as the district museum has too much of everything, so the late

collector of Abbeville spent a long life and an ample fortune in

laying his hands upon everything not bought and sold for daily

needs.

Of the acres upon acres of crowded space I only remember one

speciality, namely a most rare and curious set of paintings on

Cordovan leather, the only thing of the kind I have ever seen. The

subjects represented are hunting scenes, alike drawing and colouring

being crude but animated and highly pictorial. Porcelain, pottery,

enamels, pictures, engravings and historic portraits, old furniture,

inlaid cabinets, engraved gems, medieval bindings, prehistoric

implements. All these could only be hastily and, I fear,

unprofitably glanced at. The town museum is still more magnificently

housed, and contains amongst other treasures a good portrait of the

lovely Madame Tallien and many beautiful engravings. Both museums

are under feminine control and a pleasing memory did I bring away

from the last-named.

Having broken my fast at seven o'clock, by eleven I felt in need of

refreshment. On asking our cicerone, a bright little maiden, for a

slice of bread, she smilingly brought me a plateful of delicious

bread and butter and a little glass jar of strawberry jam. Both

tasted better for the donor and for the fact of being degustated in

the beautiful garden.

The environs of Abbeville are very pretty, and in a drive of an hour

or two we obtain highly characteristic views of French scenery,

richly shaded walks by canal and river, here and there bits of

old-world architecture peeping through the trees or vistas of varied

crops, brilliantly contrasted crimsons, purples, and greens, amid

these being rustic groups at work, figures recalling Millet. The

sudden sight of shipping comes as a surprise. One is apt to forget

that, as M. Lenthéric tells us, Abbeville was once a port of

considerable importance, indeed at a remote period almost to be

called a seaboard town. The extensive quays show little animation at

the present time, but fifty years ago they presented a bustling

aspect, and double rows of vessels might be seen there at anchor.

Abbeville must nevertheless be a very prosperous and thrifty place. Not a sign of vagrancy, not a down-at-heel, out-at-elbow man, woman,

or child do you meet in its clean, quiet streets and well-built suburbs. The manufacture of carpets and other industries evidently more than

compensate for maritime importance.

And if the whimsical unprogressiveness I have alluded to hath

charms, nowadays when in every little general shop throughout

Brittany you see the New York Herald, when at out-of-the-way

stations German house-porters meet you in smart uniform, when from

June till October not only Brittany but Normandy and Touraine are

crowded with English and American trippers, how refreshing to find a

corner of France as exclusively French as in the days of our youth!

Little discomforts are soon got over. The old-world hotel, the

courtyard set round with oleanders and pomegranates in tubs, the

geraniums adorning the balcony, the buxom landlady with napkin swung

across her shoulder, serving her guests, one and all evidently old

acquaintances—all these things take us back to the France we first

knew and charm a stay at Millevoye's birthplace.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XXII.

PROSPER MÉRIMÉE AND COMPIÈGNE

THERE are many

reasons why the author of Colomba should interest English readers

perhaps more than any other nineteenth-century French man of

letters.

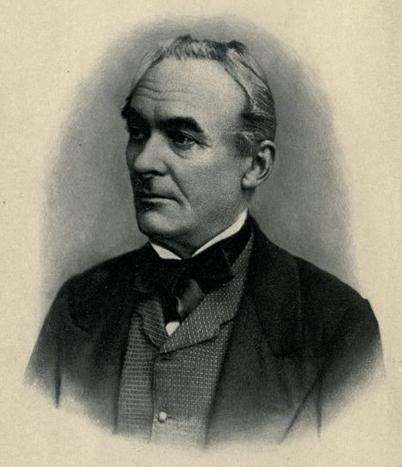

PROSPER MÉRIMÉE

(1803-70).

Picture: Internet Text Archive.

In the first place Prosper Mérimée loved England, and indeed adopted

it as a second home. Again he is one of the few French writers who

have introduced English types into fiction without travesty or

caricature, one of the fewer still whose masterpiece has become a

text-book for our boys and girls preparing for local examinations.

In the zenith of his fame he frequently sojourned among us, honoured

guest of foremost statesmen, and the devotion of English friends

cheered his old age and declining health, and—surely English

influences are discernible therein?—by a special codicil of his

will, a Protestant pastor it was who officiated at his grave.

Prosper Mérimée'e, the only child of artistic and highly honourable

parents, was born in Paris in 1803. Among the many fairy-gifts

heaped upon him as he lay in his cradle, one had been withheld. Personal beauty, even the ordinary measure of comeliness, were

lacking. A survivor of the brilliant circle in which he shone has

described him to me as a witty, ingratiating Silenus. We have only

to glance at his portrait to convince ourselves that the comparison

was not exaggerated. But what mattered personal appearance to a

Prosper Mérimée? Doubtless in no single instance did such plainness

affect either his happiness, worldly prospects, or peace of mind. From beginning to end he enjoyed good fortune.

His friends were legion, he travelled, lived at ease, loved, without

'loving unwisely or too well': if like many another genius he

ofttimes plied the muckrake instead of accepting the golden crown,

in other words, wilfully mistook his literary vocation, he

nevertheless added two masterpieces to native literature. Colomba

and the incomparable Lettres à une Inconnue are classics. Among the

numerous volumes which occupied his so-called Tacitean pen

throughout half a century, here and there one or two may be

occasionally taken down from the student's bookshelf. But the two

chefs-d'œuvre written in early life alone constitute his

title-deeds to fame.

Just as twenty years separate Comus and Paradise Lost, so to compare

the lesser with the greater, two decades divide the author of

Colomba from his latest stories. But whilst after such an interval

our 'mighty orb of song' burst out with renewed and blinding

splendour, when Mérimée the historian again reverted to romance he

found that his wand was broken. Vainly did he try to recall the old

charm; Colomba remains alone.

It would be tedious and unprofitable to follow this most versatile

writer through the various stages of his literary career. Critic,

dramatist, historian, archæologist inter alia, had he never

written that perfect little story, nor ever penned those delightful

letters to 'an unknown one,' we might almost be disposed to apply

Johnson's famous eulogium on Goldsmith. But great as were his

historic gifts, they were generally thrown away on unattractive

subjects, and the very volume of his miscellaneous writings acts as

a deterrent. I will therefore say something of his life and his

connection with Compiègne.

It was in 1833 that he met the Comtesse de Montijo, mother of the

future Empress, and of whom he wrote to his friend Stendhal—'In her

I have found an excellent friend, but there has never been any

question of any other feeling but friendship between us.' Her

daughter Eugénie, present ex-Empress, was at that time a child of

four, and it was on Mérimée's knees that she learned her letters. When seventeen years later he learned that his beautiful pupil, for

so she had continued to be during the interval, was to become his

sovereign, his initiative was highly characteristic.

Straightway he offered her his life-long homage, promising that he

would never under any circumstances ask her good offices on behalf

of outsiders or seek to influence her opinion. And he kept his word.

Henceforth Mérimée's existence was changed, and in a certain sense

to the end of his days [p.265-1] he remained

a courtier. If we regret that the romancer now forsook fiction for

archæology and the semi-intellectual amusement of the most

frivolous court in Europe, we must on one account regard the change

as fortunate. But for the Lettres à une Inconnue we should perhaps

have no imperishable picture of society under the Third Empire. [p.265-2] Other records exist in plenty, but no

habitué of Compiègne wielded

Mérimée's pen.

The manners were of a piece with the morals of that period. The

paternally affectionate knight-errant, the senator, the fastidious

man of letters, was not disposed to exaggerate matters. I subjoin in

a footnote a passage from the famous letters. [p.265-3]

If Prosper Mérimée wasted some of his best years in supplying and

superintending court comediettas and charades, as archæologist in

the pay of the State, he accomplished measures of lasting and

immense value. To his efforts is due the preservation of the abbey

church of Vézelay, this instance being one of many in point. One of

the last acts of Mérimée's life did more credit to his heart than

his head.

When 'deep in ruin and in guilt' the Third Empire fell, an agèd,

suffering, worn-out man, with indeed the hand of death upon him, he

dragged himself to Paris for the sake of seeing M. Thiers, trying to

induce that old man eloquent to throw patriotism to the winds and

risk civil war on behalf of the beautiful but misguided woman who

had been mainly instrumental in bringing about Sedan and its

consequences. But Thiers was immovable, and the ex-Empress's

advocate returned to Cannes to die. His death, occurring amid such a

cataclysmal upheaval, created no noise, and, as has been already

stated, to the astoundment, not to say scandal, of his Catholic

friends, a minister of the Reformed faith performed the last

religious rites.

Mérimée, his biographer tells us, was fond of all animals, but

passionately so of cats. The sensitiveness, elegance, and disdain of

cats attracted him. He could not see a cat without wanting to make

it happy, and upon one occasion, for several days running, he

trudged several miles in order to feed a poor puss inhumanly left

behind after its owners' removal. For the matter of that, a love of

cats is especially a French trait. I well remember when inspecting a

historic old church near Dijon, with M. Paul Sabatier, how he

immediately took up and caressed the sacristan's pet who had come

purring after us.

Compiègne is a delightful little place to halt at when the

thermometer does not mark ninety-nine Fahrenheit in the shade. This

was my experience on a recent visit, but of course, is wholly

exceptional.

The magnificent forest, so unlike those of Rambouillet, the fine old

gardens, the château—an object-lesson in upholstery and decoration

of the First Empire—the quiet beauty of the Oise, the rustic

pictures to be gained farther afield, render this aristocratic townling a most agreeable

villégiature. For Compiègne is essentially

aristocratic. The population is divided into three classes, each

holding as completely aloof from each other as French and Germans in

Alsace and Lorraine. Noblesse, here chiefly Imperialist, bourgeois,

and the work-a-day world hold no kind of intercourse. Apart they

remain, as do their châteaux, villas, and modest cottages. For it

must never be forgotten that in democratic France there is much less

fusion of classes than in aristocratic Albion.

But the general impression of Compiègne is one of urbanity, not too

ostentatious wealth, whether inherited or parvenu, and universal

well-being. Cheerfullest of the cheerful, of Compiègne it may also

be said that there we can take our ease at our inn.

It is not Jeanne d'Arc or the Corsican Cæsar and his pinchbeck

imitator that the English flâneur will have uppermost in his mind

here. Instead he will think of the brilliant Frenchman whose heart

in early life went out to England, who remained a half-Englishman to

the end, who, moreover, unique among French writers, has given in

his flawless little romance true and dignified portraiture of

English character, and who, when his long, prosperous, and

honourable career was drawing to a close, found support and solace

in English friendship and devotion.

THE END |